Ende (ISO639-3 code: kit) is a Pahoturi River language spoken by at least 600 (Eberhard, Simons & Fennig Reference Eberhard, Simons and Fennig2019) and as many as 1000 (Dareda Reference Dareda2016) people in Western Province, Papua New Guinea, primarily in the villages of Limol, Malam, and Kinkin, as shown in Figure 1. The Pahoturi River family, which also includes the Agob, Em, Idi, Kawam, and Taeme language varieties, has not yet been demonstrated to be related to any other language family and is thus classified as Papuan due to its geographical location. As with many languages in the region, the name of the language, Ende /ende/ [ʔende], is the Ende word meaning ‘what’.

Figure 1 South Fly villages with predominant Pahoturi River speaker populations.

Multilingualism is common among Ende speakers, arising from a sister-exchange marriage tradition, which results in many women and men marrying into the community from other linguistic backgrounds. In addition to one or more neighboring local languages, especially Taeme and Kawam, many Ende speakers also speak English, which is the regional lingua franca used in education and religion. Tok Pisin is a lesser-known contact language and is primarily spoken by people who have spent time outside of southern Western Province. In Limol, Ende is the primary language in most domains of interaction except for schooling, which is conducted in both English and Ende at the elementary level and solely in English afterward.

The data for this illustration were collected in Limol village between 2015 and 2018. To illustrate the diverse range of Ende speech, I analyzed the speech of 16 Ende speakersFootnote 1 (for demographic information, see Lindsey Reference Lindsey2019: 146). This sample is balanced in terms of gender (eight men and eight women) and age (four speakers each under 30, 30–45, 46–61, and 62 and older). The phonetic analysis of the consonants and vowels, as described below, was based primarily on these recordings, in supplementation with 11 months of community observation and ongoing analysis of the Ende Language Corpus (Lindsey Reference Lindsey2015).

All of the examples of the Ende language in this illustration are represented in writing in three ways: an orthographicFootnote 2 representation (in italics), a phonemic transcription (in /slashes/), and a narrow phonetic transcription of the accompanying audio recording (in [brackets]).

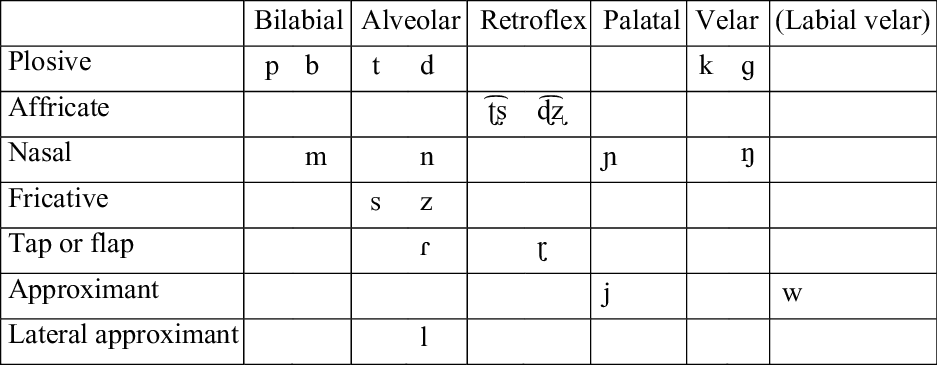

Consonants

There are 19 phonemic consonants in Ende. In the table above, a symbol from the International Phonetic Alphabet was chosen to symbolize each phonemic category. Each category represents a wide range of inter- and intra-speaker phonetic variation, which will be described in this article. For example, the voiceless retroflex affricate symbol /ʈ͡ʂ/ represents the phonemic category that is expressed by a range of phonetic realizations including [ʈ͡ʂ], but also a postalveolar [t̠͡ʃ], a postalveolar [t͡ɹ̠̊], or even a non-affricated [ʈ].

The tables below present each consonant in word-initial, word-medial, and word-final positions in near-minimal pairs. To the greatest extent possible, each consonant is preceded or followed by the low, central vowel /ɐ/ (transcribed throughout this paper with the symbol for the low-front vowel /a/ for readability).

Consonants in word-initial position

Consonants in word-medial position

Consonants in word-final position

Plosives

Voiced and voiceless plosives contrast at the bilabial, alveolar, and velar places of articulation. (Note that retroflex/postalveolar plosives occur in the data and are analyzed as allophones of the retroflex affricates, see below.) The voiceless plosive /t/ is consistently articulated with the tongue behind the teeth but appears to vary between a dental (apical) or alveolar (laminal) articulation.

The voiceless plosives and affricates have short voice onset times (VOTs) in word-initial position, indicating very minimal aspiration for /p/ and /t/ and light aspiration for /k/. On the other hand, the voiced plosives and affricates feature considerable prevoicing in word-initial position. This two-way laryngeal contrast classifies Ende as a ‘true voice’ language, like Russian, French, Dutch, or Hungarian (Ringen & Kulikov Reference Ringen and Kulikov2012: 270).

Prevoicing durations for voiced plosives vary greatly across tokens. An analysis of voice onset times across 18 words as spoken by four speakers three times each (N = 216) revealed that VOTs of voiceless plosives (measured from the burst release to the onset of voicing of the vowel) exhibit less variation than VOTs of voiced plosives (measured from the onset of voicing to the burst release), see standard deviation values in Table 1.

Table 1 Mean voice onset times for plosives.

However, although the duration of prevoicing varies greatly before voiced plosives, this variation is also observed within tokens of the same word (e.g. for bawa ‘rainy season’, max = –187 ms and min = –73 ms, see Figures 2 and 3). Thus, although the phonetic variation is stark, there is no evidence for a phonemic contrast in VOT length. Also notable in the VOT of Figure 3, is a complex waveform and formant structure – characteristics of prenasalization or ‘nasal venting’ (Kharlamov Reference Kharlamov2018: 216).

Figure 2 Voice onset time of /b/ in bawa ‘rainy season’, –174 ms (D. Kurupel Reference Kurupel2018: 41).

Figure 3 Voice onset time of /b/ in bawa ‘rainy season’, –72.5 ms (Frank Reference Frank2018: 41).

All six plosive phonemes occur in word-initial, word-medial, and word-final positions though the voiceless phonemes are more frequent, especially word-finally. In intervocalic positions, voiced plosives are variably lenited. Compare gaguma /ɡaɡuma/ ‘yamhouse’ in Figure 4 (stopped: [ɡaɡuma]) and Figure 5 (lenited: [ɡaɰuma]).

Figure 4 Stopped variant of intervocalic /g/ (P. Kurupel Reference Kurupel2018).

Figure 5 Lenited variant of intervocalic /g/ (Kaoga (Dobola) Reference Kaoga (Dobola)2018a).

In final position, consonants are often released with an anaptyctic vowel of central quality (e.g. käp /kʌp/ [kʌpʌ] ‘fruit’ and gwem /ɡwem/ [ɡwɛmʌ] ‘river part’).

Notable absences from the plosive inventory include the labial-velar plosives present in other Pahoturi River languages, such as Idi (/k͡w ~ k͡pʷ ɡ͡bʷ/), and Yam languages such as Nmbo and Nen (/k͡pw ɡ͡bw/; Evans & Miller Reference Evans and Miller2016, Ellison et al. Reference Ellison, Evans, Kashima, Lindsey, Quinn, Schokkin and Siegel2017). Ende cognates with Idi words that begin with /k͡w ~ k͡pʷ ɡ͡bʷ/ are realized as /k ɡ/ and are often (but not always) followed by a rounded vowel.

There are a limited number of words in the Ende lexicon that include onsets with /kw/ or /ɡw/, such as kwi ‘island’ and gwem ‘river part’. This sequence is never followed by a rounded vowel. One could analyze these /kw/ and /ɡw/ sequences as monosegmental phonemes (/kʷ/ and /ɡʷ/) or as sequences of phonemes, as I have done. Support for the complex onset hypothesis comes from the fact that Ende allows other complex onsets with plosives and glides. The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/ can also precede /w/ in initial position. Moreover, plosives form complex onsets with the other phonemic glide /j/. Examples are shown in the table below.

Plosive-glide sequences in word-initial and word-medial positions

For now, I will analyze /kw/, /ɡw/, /pw/, /bw/, /kj/, and /bj/ as complex onsets, although they may have a monosegmental origin.

Ende’s plosive inventory also differs from related Idi and nearby Yam languages, such as Nmbo, Nen (Evans & Miller Reference Evans and Miller2016), Nama, and Ngkolmpu (Carroll Reference Carroll2016), in that while linguists report voiced prenasalized plosives (/ᵐb ⁿd ᵑɡ ᵑɡ͡bʷ/) for Idi, Nmbo, Nen, and Nama, and voiceless prenasalized obstruents (/mp nt ᵑk ns/) for Ngkolmpu, I do not report any prenasalized phonemes in Ende’s inventory. I hesitate to distinguish Ende in this way because the candidates for prenasalized phonemes in Ende (/mp mb nt nd Ŋk Ŋɡ nʈ͡ʂ nɖ͡ʐ ns nz/) appear to be both phonetically and phonotactically similar to the ‘prenasalized consonants’ reported in Idi, Nmbo, and Nen. However, the distribution and behavior of these candidates do not provide adequate evidence for rejecting the hypothesis that they are sequences of phonemes, as has been done for languages with substantiated phonemic prenasalization, such as nearby Komnzo (Döhler Reference Döhler2018), Ngkolmpu (Carroll Reference Carroll2016), and Coastal Marind (Olsson Reference Olsson2017).

The following tables illustrate these nasal–obstruent sequences in word-medial and word-final position with a preceding or following low, central /ɐ/. These sequences do not appear contrastively in word-initial position, although several experts have noted that the significant prevoicing of some voiced obstruents sounds in word-initial positions contains complex waveforms and formant structure: evidence of prenasalization.

Nasal–obstruent sequences in word-medial position

Nasal–obstruent sequences in word-final position

Affricates and fricatives

There are two retroflex affricates, /ʈ͡ʂ/ and /ɖ͡ʐ/, and two alveolar fricatives, /s/ and /z/. The voiced affricates and fricatives are fully voiced in all positions, often with significant prevoicing, as detailed earlier for the voiced plosives.

Retroflex obstruents are atypical of Papuan languages in general (Foley Reference Foley2000) and bring more to mind languages further south in Australia (Evans Reference Evans, Evans and Klamer2012). Regionally, retroflex obstruents are more common. They can be found in all Pahoturi River languages, except perhaps Kawam, in which they have been replaced by palatal fricatives (Badu Reference Badu2018). Retroflex plosives can also be reconstructed for the Yam family (Evans, Carroll & Döhler Reference Evans, Carroll and Döhler2017). These retroflex affricates can be found in all positions of the syllable and the word. The degree of retroflexion apparent in acoustic analyses is weak. Further articulatory evidence is necessary for saying anything more specific about the shape of the tongue for these sounds. The retroflexes are notably distinguished from /t͡ʃ/ (found in loanwords, such as change, church, teacher, and chip ‘chief’) and [d͡ʒ] (an allophonic variant of /z/, and found in loanwords such as pidgin ‘Tok Pisin’).

The retroflex affricates undergo considerable allophonic variation, both in manner and place. With regards to manner, the corpus includes numerous examples of the affricates being realized as plosives or as fronted fricatives (e.g. listen to the fronted [ʒ] or [z̠] in ddone /ɖ͡ʐone/ [ʒone] ‘no’ and kumuddäga /kumuɖ͡ʐʌɡa/ [kumʒʌɡa] ‘three’ as spoken by Wendy Frank, Ende woman, age 28). A variationist analysis of retroflex affricate tokens within recordings of natural speech demonstrates that these retroflex consonants are more likely to be realized as plosives when produced by speakers who perform kawa, a prestigious style of oration within the Ende community (Strong, Lindsey & Drager Reference Strong, Lindsey and Drager2020). Strong and colleagues go on to show that among the orators, older speakers and women are more likely to produce these consonants as plosives compared with younger speakers and men.

With regards to place, these affricates vary from a retroflex articulation with expected low third formant (F3) values transitioning into the plosive (see Figure 6 and listen to ttam /ʈ͡ʂam/ ‘leaf’, ddapall /ɖ͡ʐapaɽ/ ‘sky’, wanttawantta /wanʈ͡ʂawanʈ͡ʂa/ ‘game type’, and ddonddo /ɖ͡ʐonɖ͡ʐo/ ‘to boast’), and a postalveolar without any F3 dips (e.g. [t̠͡ʃ], see Figure 7), sometimes even with hints of a postalveolar rhotic (like in the English tree [t͡ɹ̥͟i]). Informal observations indicate that younger women are producing more fronted variants than their older or male counterparts, suggesting this may be a change in progress.

Figure 6 Spectrogram of ttam ‘leaf’ with characteristic low F3 dip (2153 Hz) during the transition from the plosive (Kaoga (Dobola) Reference Kaoga (Dobola)2018a).

Figure 7 Spectrogram of ttam ‘leaf’ with stable F3 (2399 Hz) in the transition from the plosive (Kaoga (Dobola) Reference Kaoga (Dobola)2018a).

There are two fricatives /s/ and /z/. Both are comparatively rare phonemes within the corpus. The phoneme represented as /z/ exhibits considerable phonetic variation, which has been observed for this phoneme across the southern New Guinea region. In Ende, /z/ is variably realized as an alveolar fricative [z], an alveolar affricate [d͡z], a retracted alveolar affricate [d͡z̠], a retracted alveolar fricative [z̠], or a postalveolar affricate [d͡ʒ]. Thus, the word /pazi/ ‘year’ can be pronounced in at least five different ways. More articulatory data is needed.

Variable pronunciations of /pazi/

Nasals

Nasals contrast at four places of articulation: bilabial, alveolar, palatal, and velar. The palatal and velar nasals are atypical for non-Austronesian languages in New Guinea (Foley Reference Foley2000) but common in Austronesian (Blust Reference Blust2013). This set of nasals can be found in all Pahoturi River languages. Nasal consonants can be found in all positions of the word and syllable. Velar nasals undergo optional deletion in word-initial position.

Liquids

The Ende inventory includes three liquids: an alveolar tap /ɾ/, a retroflex flap /ɽ/, and an alveolar lateral approximant /l/. Ende lacks the palatal lateral approximant /ʎ/ found in Idi and Taeme, which is realized as /ɽ/ or /l/ in cognates (Evans, Lindsey & Schokkin Reference Evans, Lindsey and Schokkin2019).

Unlike the other consonant categories, the liquid consonants are not evenly distributed across phonological contexts. Among the liquids, /ɽ/ is most common word-initially, inter-vocalically, and word-finally, although /ɾ/ approaches the count of /ɽ/ inter-vocalically. The distribution of liquids is more similar in complex onsets and codas, although they are far more common in onsets than in codas. The counts in Table 2 are based on the 2017 Ende dictionary, which included approximately 5000 words.

Table 2 Distribution of liquids across phonological contexts.

As with the retroflex affricates, the retroflex flap also often has weak retroflexion in its articulation. The following figures provide a near-minimal triplet contrasting intervocalic /ɽ/ with clear retroflexion (Figure 8), less-clear retroflexion (Figure 9), and the alveolar tap (Figure 10).

Figure 8 Spectrogram of malla ‘not’ with a clear F3 dip before the retroflex flap (Warama (Kurupel) Reference Warama (Kurupel)2018).

Figure 9 Spectrogram of malla ‘not’ with stable F3 contour before the retroflex flap (P. Kurupel Reference Kurupel2018).

Figure 10 Spectrogram of para ‘yam-counting ceremony’ with no apparent F3 dip before the alveolar tap (Frank Reference Frank2018).

Glides

There are two glides or semi-vowels in the Ende consonant inventory: /w/ and /j/. These glides occur in word-initial and syllable-initial positions, as illustrated with contrastive minimal pairs in the tables below. In word-final position, speakers prefer to write these sequences of vowel and glide as diphthongs (e.g. ao /aw/ [a̰ʊ̰] ‘yes’ and mae /maj/ [maɘ] ‘sago type’). However, they behave like word-final consonants in cliticization contexts.

Glides in word-initial position with minimal pairs

Glides in inter-vocalic position with minimal pairs

Glides in word-final position with minimal pairs

These glides are also used epenthetically. Their epenthetic function is to provide onsets to words beginning in non-low vowels and to break up vowel sequences. Typically, the front glide precedes word-initial front vowels /i/ and /e/, while the back glide precedes word-initial back vowels /o/ and /u/.

Vowels

Vowels in word-medial position

Ende has seven phonemic vowel qualities, including five peripheral vowels /i e a o u/ and two central vowels /ɘ ʌ/. The placement of the vowels in the vowel diagram above is approximated from the plot in Figure 11, in which the normalized F1/F2 measurements of 2402 vowel tokens spoken by 17 speakers (aforementioned 16 speakers with supplemental recordings from Musato Giwo (Giwo Reference Giwo and Lindsey2016)) are plotted. The plot below was made using the phonR package (McCloy Reference McCloy2016).

Figure 11 (Colour online) Plot of normalized F1 versus F2 values of 2402 vowel tokens of 17 speakers (small vowel symbols). Ellipses indicate a 95% confidence interval variance from the mean (large vowel symbol).

Ende’s vowel inventory stands out in the Pahoturi River family because it has only one low open vowel /a/, while all other Pahoturi River varieties have two /œ/ and /a/.

The central vowels /ɘ/ and especially /ʌ/ have quite broad distributions throughout the center of the vowel space. The vowel represented by /ɘ/ is higher (closer) than both /e/ and /o/ and participates as a high vowel in height-based vowel harmony (Lindsey Reference Lindsey2019: 190). For this reason, I chose the symbol for the near-close, non-rounded vowel, /ɘ/. An alternative symbol would be /ɪ/.

The vowel represented by the symbol /ʌ/ is distributed somewhat lower (more open) than /e/ and /o/ but participates as a mid vowel in height-based vowel harmony. The vowel’s distribution is central, not back, and also serves as a catch-all epenthetic, central vowel. For this reason, I chose the /ʌ/ symbol, although /ə/ may also be an appropriate choice.

Moreover, this analysis reveals a resemblance between the central vowels of Ende and the central vowels of nearby Nen (Evans & Miller Reference Evans and Miller2016). In both languages, /ɘ/ and /ʌ/ can neither begin nor end words (except as anaptyctic vowels) but do contrast minimally with one another and with the peripheral vowels.

The central vowels also differ from the peripheral vowels in terms of length. As shown in Figure 12, the central vowels /ʌ/ and /ɘ/ are the shortest on average, followed by the high vowels /i/ and /u/, the mid vowels /e/ and /o/ and the low vowel /a/. In this plot, the notches display a confidence interval around the median values, the boxes represent the mid 50% of the data, the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum values, while the dots outside the whiskers represent statistical outlier values.

Figure 12 (Colour online) Plot of duration values of 2402 vowel tokens of 17 speakers.

Note that vowels in word-initial and word-final positions are often preceded or followed by an audible glottal stop. Compare the two tokens of the word aya /aja/ in Figure 13, in which the first token features a smooth vowel onset, while the second token has an abrupt onset (glottal stop); both also end in a glottal stop.

Figure 13 Two tokens of aya /aja/ without and with an initial glottal stop (Dareda Reference Dareda2018).

One vowel process of note is vowel harmony. Ende vowel harmony is progressive, can be triggered by prefixes, and following vowels alternate to harmonize in height (high or mid) with the preceding vowel (Lindsey Reference Lindsey2019: 190). In this way, we observe alternations between /i ~ e/, /u ~ o/, and /ɘ ~ ʌ/. The low vowel /a/ blocks progressive vowel harmony.

Prosody

Ende does not have lexical stress or tone. There are no words in the current lexicon that minimally contrast by something like stress, and tonelessness is a typological feature of the region (Evans et al. Reference Evans, Arka, Carroll, Choi, Döhler, Gast, Kashima, Mittag, Olsson, Quinn, Schokkin, Tama, van Tongeren, Siegel and Palmer2018: 738).

Intonational frames are poorly understood in the language. Questions do not systematically end in a rising tune and are often falling, even though word order does not always indicate whether or not the utterance is a question or a statement. One interesting use of intonation is the Call-at-Distance form. This form is similar to the Nungon Call-at-Distance form observed by Sarvasy (Reference Sarvasy2017a: 106–109; Reference Sarvasy2017b) and is used whenever the speaker is at a considerable distance or out of view from the intended recipient. The Call-at-Distance form is located at the end of an utterance and entails final vowel lengthening, the addition of /-oː/ or /-aj/, and a considerable rise in pitch and loudness, especially for questions (Jerry Reference Jerry2016a, Reference Jerryb, Reference Jerryc, Reference Jerryd, Reference Jerrye; W. Geser Reference Geser2017). For example, the Call-at-Distance form for mer ag /meɾ aɡ/ ‘good morning’ is pronounced [meɾ aɡoː] at distance and bongo ine ma we yaralle? /boŊo ine ma we jaɾaɽe/ ‘did you go to the well?’ is pronounced [boŊo ine ma we jaɾaɽe aj] ‘did you go to the well?’ at distance.

Transcription of the recorded passage

The story of the North Wind and the Sun was translated into Ende by Andrew Kaoga (Dobola) (Kaoga (Dobola) Reference Kaoga (Dobola)2018b). The text features some cultural adjustments; for instance, the North Wind is translated as kämag /kʌmaɡ/ ‘the West Wind’, and the warm cloak is substituted with a labalaba /labalaba/ ‘laplap, a piece of cloth tied around the waist’. The resulting story contains all phonemes except /ɘ/ and /z/. That is to say that this story represents 89.4% of the phoneme inventory. The text is also missing initial /i n ɲ s r/, medial /ɖ͡ʐ ɲ/, and final /b t k ɖ͡ʐ s r w/. In summary, the text captures 43 of 57 or 75.4% of expected phoneme positions. The text is presented below in a broad phonemic translation and an interlinear text with orthographic representation, word-level glosses, and phrase-level free translations into English.

Kämag a wa Yäbäd a (The West Wind and the Sun)

Andrew K. Dobola

Broad phonemic transcription

ɡudaj ɡudaj tʌrʌp me kʌmaɡ a jʌbʌd a dejaɡernejo ʈ͡ʂoŊo jebdo me ubi oba mʌŊaɽ de ɡonɖ͡ʐonejo kʌmaɡ Ŋʌmo mʌŊaɽ a uɽe dan jʌbʌd eka mu dʌɡaɡʌn ɖ͡ʐone Ŋʌmo ade mʌŊaɽ a uɽe dan ʈ͡ʂoŊo tʌrʌp me ibiaɡ a daɽnʌn boɡo labalaba aɽe ɡokʌnewʌn kʌsre ada ɡoɡejo da ajja labalaba de bʌŊkʌnʌn obo pʌʈ͡ʂ aʈ͡ʂ ede obo mʌŊaɽ a uɽe dan kʌmaɡ aŊde obo wel de Ŋaʈ͡ʂoŊ dajrʌŊʌn diba ɽa pate dapʌdojʌn duduweduduwemaŊ ada oba obo labalaba de bʌŊkʌnʌn be ɖ͡ʐone dʌŊkʌnʌn dʌbe ɽa da obo labalaba de ɽokʈ͡ʂaŊaj damɽamʌn kʌmaɡ ɽʌʈ͡ʂ ɡoɡʌn ada maɽa Ŋʌna muɽdaj dan kʌsre jʌbʌd ɡoberɡabʌn ʈ͡ʂʌnʈ͡ʂʌm pejaŊ jʌbʌd aŊde ʈ͡ʂʌnʈ͡ʂʌmaŊ abal ɡoɡon dʌbe ɽa da obo labalaba de dʌŊkʌnʌn ʈ͡ʂʌnʈ͡ʂʌm aʈ͡ʂa a memram a dʌɡaɡʌn. kʌmaɡ kilimiɲ ɡoɡon adawaʈ͡ʂa jʌbʌd bo mʌŊaɽ a uɽe daja kʌmaɡ ada ɡoɡon bʌne mʌŊaɽ a uɽe dan be Ŋʌmo kʌlsre dan

Interlinearized text

The abbreviations in this passage are as follows: > = acting upon; 3 = third person; abl = ablative; acc = accusative; all = allative; anim = animate; aux = auxiliary; cop = copula; du = dual; dur = durative; fut = future; inst = instrumental; loc = locative; nom =nominative; poss = possessive; prs = present; pst = past; rem = remote past; S = subject; sg = singular.

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, I acknowledge the Ende tribe of Limol and Malam villages for sharing their language with me. This research would not be possible without the generosity of the following speakers, who contributed audio recordings to the Ende Language Corpus: Jerry Dareda, Kaoga Dobola, Wendy Frank, Kwale Geser, Wagiba Geser, Musato Giwo, Namaya Karea, Andrew Kaoga (Dobola), Donae Kurupel, Paine Kurupel, Sarbi Kurupel, Warama Kurupel (Suwede), Karea Mado, Maryanne Sowati (Kurupel), Gloria Warama (Kurupel), Tonny (Tonzah) Warama, and Winson Warama. I am also very grateful for the insights and data shared with me by fellow Pahoturi River-ists Dineke Schokkin and Catherine Scanlon. Finally, I would like to thank Amalia Arvaniti, Marc Garellek, Eri Kashima, André Radtke, Marija Tabain, and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions, which have greatly improved the quality of this paper. The fieldwork that made this data collection possible was sponsored by the Firebird Foundation for Anthropological Research, the American Philosophical Society, and the linguistics departments at Stanford University and Australian National University.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article (including audio files to accompany the language examples), please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100320000389.