INTRODUCTION

Within the field of neuropsychology, there is a growing recognition of the importance of subjective cognitive complaints and an emergence of several related avenues of clinical research. Self-reported cognitive difficulties are an important assessment focus for multiple reasons. They often represent a compromise in persons’ quality of life and can signify changes that are a source of disruption in interpersonal relationships, general level of activity and participation in daily life activities, and occupational functioning (van Rijsbergen, Mark, Kop, de Kort, & Sitskoorn, Reference van Rijsbergen, Mark, Kop, de Kort and Sitskoorn2019). Social ties and connections can suffer the ill effects of diminished communication that can result from impaired attention, concentration, and failed retention of new information. Complaints of problems such as distractibility and forgetfulness in the workplace are often associated with a reduction in occupational responsibilities, decline in work status, job loss, or forced retirement. Individuals’ cognitive complaints reflect recognized limitations that might also have special relevance in rehabilitation settings where, for example, an accurate awareness of deficits provides an impetus for commitment to therapeutic work (Spreij, Sluiter, Gosselt, Visser-Meily, & Nijboer, Reference Spreij, Sluiter, Gosselt, Visser-Meily and Nijboer2019). The absence of self-reported cognitive difficulties in persons who are cognitively impaired often reflects anosognosia, which has major implications for safety, treatment, and caregiver burden (Spitznagel & Tremont, Reference Spitznagel and Tremont2005). Cognitive complaints are frequently associated with emotional distress and may be symptomatic of disorders of mood and thinking. Numerous studies support the conclusion that cognitive complaints are more strongly related to emotional distress, especially depression, than to objective neuropsychological test performance (Bowler et al., Reference Bowler, Adams, Schwarzer, Gocheva, Roels, Kim and Lobdell2017; Burmester, Leathem & Merrick, Reference Burmester, Leathem and Merrick2016; Crumley, Stetler, & Horhota, Reference Crumley, Stetler and Horhota2014; Derouesné et al., Reference Derouesné, Dealberto, Boyer, Lubin, Sauron, Piette and Alpérovitch1993; Hill, Aschwanden, Payne, & Allemand, Reference Hill, Aschwanden, Payne and Allemand2020). Complaints are also associated with a variety of problems in everyday living (Chaytor, Temkin, Machamer, & Dikmen, Reference Chaytor, Temkin, Machamer and Dikmen2007; Spreij et al., Reference Spreij, Sluiter, Gosselt, Visser-Meily and Nijboer2019).

A growing body of research is focused on self-reported cognitive decline as a possible precursor to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and the subsequent development of Alzheimer’s disease (Bessi et al., Reference Bessi, Mazzeo, Padiglioni, Piccini, Nacmias, Sorbi and Bracco2018; Dufouil, Fuhrer, & Alpérovitch, Reference Dufouil, Fuhrer and Alpérovitch2005; Lin, Shan, Jiang, Sheng, & Ma, Reference Lin, Shan, Jiang, Sheng and Ma2019; Mark & Sitskoorn, Reference Mark and Sitskoorn2013; Mazzeo et al., Reference Mazzeo, Padiglioni, Bagnoli, Carraro, Piaceri, Bracco and Bessi2020). Despite existing evidence to the contrary (e.g., Edmonds, Delano-Wood, Galasko, Salmon, & Bondi, Reference Edmonds, Delano-Wood, Galasko, Salmon and Bondi2014; Jessen et al., Reference Jessen, Amariglio, Buckley, van der Flier, Han, Milinuevo and Wagner2020; Slot et al., Reference Slot, Sikkes, Berkhof, Brodaty, Buckley, Cavedo and van der Flier2018), subjective cognitive decline (SCD) in cognitively normal non-depressed persons is suspected by some investigators to precede non-normative cognitive loss and eventual progression to dementia (Rabin et al., Reference Rabin, Smart, Crane, Amariglio, Berman and Boada2015). These individuals report having cognitive decline yet perform within normal limits on standardized cognitive tests (Mitchell, Beaumont, Ferguson, Yadegarfar, & Stubbs, Reference Mitchell, Beaumont, Ferguson, Yadegarfar and Stubbs2014; Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Gomà-i-Freixanet, Valero, Rodríguez-Gómez, Sanabria and Pérez- Cordón2020; Rabin, Smart, & Amariglio, Reference Rabin, Smart and Amariglio2017). Although the relevant research findings are mixed, in some studies, the complaints appear to precede measurable decline as long as 15 years before manifesting cognitive impairment (Reisberg & Gauthier, Reference Reisberg and Gauthier2008). In addition, some studies have linked subjective memory decline with biomarkers and radiologic correlates of Alzheimer’s disease such as increased amyloid burden (Amariglio et al., Reference Amariglio, Becker, Carmasin, Wadsworth, Lorius, Sullivan and Rentz2012; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Byun, Yi, Lee, Ko, Jung and Lee2019), white matter signal abnormalities, cerebral hypometabolism, and gray matter volume loss (Cedres et al., Reference Cedres, Machado, Molina, Diaz-Galvan, Hernandez-Cabrera, Barroso and Ferreira2019).

Despite the inconsistent findings and lack of a consensus, the proliferation of research involving self-perceived cognitive problems points to an increasing need for clarifying the psychometric characteristics of self-report inventories that systematically address these issues. One such measure, the Cognitive Difficulties Scale (CDS; McNair & Kahn, Reference McNair, Kahn, Crook, Ferris and Bartus1983), is a 39-item 5-point Likert-type scale on which examinees rate their perceived frequency (ranging from “Never” to “Very Often”) of commonplace difficulties with memory and other cognitive functions within the past month. The CDS is a brief, easy-to-understand instrument that assesses cognitive difficulties that occur in a context of daily life activities. Originally designed to assess the cognitive impact of medications, the CDS has been widely used within the field of neuropsychology to assess cognitive complaints. Complaints on the CDS were predictive of cognitive decline in older persons after a 4- to 5-year follow-up (Dardenne et al., Reference Dardenne, Delrieu, Sourdet, Cantet, Andrieu, Mathiex-Fortunet and Vellas2017; Dufouil, Fuhrer, & Alpérovitch, Reference Dufouil, Fuhrer and Alpérovitch2005).

Derouesné et al. (Reference Derouesné, Dealberto, Boyer, Lubin, Sauron, Piette and Alpérovitch1993) used the CDS to investigate perceived cognitive difficulties in 1648 normal volunteers, aged 48–75 years, who were devoid of severe medical or psychiatric disorder. Other CDS studies have focused on specific diagnostic groups, including patients with cardiovascular disease (Haley et al., Reference Haley, Hoth, Gunstad, Paul, Jefferson, Tate and Cohen2009, Reference Haley, Eagan, Gonzales, Biney and Cooper2011), traumatic brain injury (Gass & Apple, Reference Gass and Apple1997), post-traumatic headache (Branca, Giordani, Lutz, & Saper, Reference Branca, Giordani, Lutz and Saper1996), epilepsy (Galioto, Blum, & Tremont, Reference Galioto, Blum and Tremont2015), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Brunette et al., Reference Brunette, Holm, Wamboldt, Kozora, Moser, Make and Hoth2018), dementia (Okonkwo, Spitznagel, & Tremont, Reference Okonkwo, Spitznagel and Tremont2010; Spitznagel & Tremont, Reference Spitznagel and Tremont2005), MCI (Buelow, Tremont, Frakey, Grace, & Ott, Reference Buelow, Tremont, Frakey, Grace and Ott2014; Coley et al., Reference Coley, Ousset, Andrieu, Mathiex-Forunet and Vellas2008), and exposure to manganese (Bowler et al., Reference Bowler, Adams, Schwarzer, Gocheva, Roels, Kim and Lobdell2017). The present study examined psychometric properties of the CDS as applied to neuropsychological referrals to a memory disorders clinic. In specific, we evaluated its factorial structure, internal consistency (reliability), item endorsement frequencies, relation to demographic variables, correlation with performance on widely used memory tests, and association with measures of depression and anxiety.

METHOD

Participants

This study was conducted in conformity with the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects outlined in Declaration of Helsinki and in compliance with the Institutional Review Board of this healthcare institution. Participants were 512 consecutive referrals for neuropsychological testing at an outpatient memory disorders clinic in northern Florida. The clinic is housed within a neurology clinic in a large metropolitan healthcare center. These community dwellers were referred by Neurology (81%), Primary Care (14%), and Mental Health (3%). The participants were 62% women and 38% men with a mean age of 62.6 (± 14.3) years. Ethnically, 85% were White non-Hispanic, 12% Black non-Hispanic, and 2% White Hispanic. Level of education was 14.7 (±2.8) years. Educationally, 47% were college graduates (16+ years), 44% had at least a high school diploma (12–15 years), and 9% had less than 12 years of formal education. Their average estimated intelligence level based on the Test of Premorbid Function (TOPF, Wechsler, Reference Wechsler2009) was within the average range (MN = 101.3 ± 12.0). Most participants were fully independent and 47% were employed in full-time positions. The percentage retired was 25.3%, unemployed 22.3%, and disabled 4.2% of the participants.

Nearly all referrals were of a diagnostic nature, initiated to assist in evaluating for possible cerebral dysfunction. The referrals were prompted by the person’s expressed problems with memory, concentration, and/or word finding. In a minority of cases, the referral was made due to informant complaints of cognitive or speech problems such as by a spouse or other family member. Only 14% of the sample had a diagnostic history involving brain disorder or brain insult. These cases consisted of traumatic brain injury (7%), cerebrovascular accident (5.8%), and seizure disorder (1.2%). Emotional disorders were formally diagnosed in 53.5% of the sample. These included depression (17%), generalized anxiety (11.5%), both depression and anxiety (17.2%), bipolar disorder (3.6%), and post-traumatic stress disorder (4.2%). Mental health diagnoses were most commonly made by a board-certified staff psychiatrist.

Instruments

The CDS (McNair & Kahn, Reference McNair, Kahn, Crook, Ferris and Bartus1983), previously described, is relatively simple to read, with a Flesch–Kincaid reading level of 5.4. Psychometric support for the CDS derives from analyses of its test–retest reliability (.77, McNair & Kahn, Reference McNair, Kahn, Crook, Ferris and Bartus1983), factorial stability, and convergent validity with measures of depression and cognitive test performance (Bowler et al., Reference Bowler, Adams, Schwarzer, Gocheva, Roels, Kim and Lobdell2017; Derouesné et al., Reference Derouesné, Dealberto, Boyer, Lubin, Sauron, Piette and Alpérovitch1993; Gass & Apple, Reference Gass and Apple1997). The CDS was reported to be predictive of cognitive decline (Dardenne et al., Reference Dardenne, Delrieu, Sourdet, Cantet, Andrieu, Mathiex-Fortunet and Vellas2017). A slightly revised version of the CDS was used in the present study. Item 1 (“I forget frequently used phone numbers.”) was eliminated due to frequent examinee reminders of the item’s obsolescence and the widespread popularity of speed dialing. A replacement for item 1 was based on a commonly heard complaint: “I forget where I parked my car.” Finally, item 40 was added to the CDS based on a common clinical concern typically expressed as an interview question by staff neurologists: “I forget that the oven or stove is turned on.”

The relation of cognitive complaints to actual memory test performance was investigated using the Logical Memory (LM) and Visual Reproduction (VR) subtests of the Wechsler Memory Score IV (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler2008), the Digit Span subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Fourth edition (WAIS-IV; Wechsler, Reference Wechsler2008), and the TOPF (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler2009). The latter test was used to provide an estimate of participants’ longstanding level of intellectual functioning.

To measure psychological variables, we used scales 1 (Hs, hypochondriasis), 2 (D, depression), 7 (Pt, psychasthenia), and 8 (Sc, schizophrenia) of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2; Butcher, Dahlstrom, Graham, Tellegen, & Kaemmer, Reference Butcher, Dahlstrom, Graham, Tellegen and Kaemmer1989). These scales, which assess health preoccupations, symptoms of depression, anxiety, and unusual ideation, have an extensive research base and are widely used within the field of neuropsychology (Gass, Reference Gass, Butcher and Hooley2018; LaDuke, Barr, Brodale, & Rabin, Reference LaDuke, Barr, Brodale and Rabin2018).

Procedure

Participants were initially interviewed and then administered the CDS prior to a comprehensive battery of neuropsychological tests that included the LM and VR subtests, Digit Span, and the TOPF. As part of the assessment, participants read aloud the CDS instructions. In almost all cases, they were able to read and complete the CDS without special assistance from the examiner. In a small number of cases, patients were excluded from participation because they were unable to read the CDS or follow the instructions.

Statistical Analyses

In order to examine the underlying dimensions measured by the CDS, responses to the 40 CDS items were subjected to a principal components analysis (PCA) followed by a varimax rotation of all factors that satisfied Kaiser’s criterion (eigenvalue > 1). Factors were composed of items that satisfied the criterion of having factor loadings of at least .40 with no equivalent or higher loadings on other factors (Nunnally, Reference Nunnally1978). Factor labels were devised based on the semantic theme reflected in the factorial item content, with greater semantic weight given proportionately based on the size of the item loadings. Factor scores were derived by adding unweighted raw scores across the items that constituted the respective factor. The reliability of the CDS factors as dimensional measures was examined using Cronbach’s alpha to measure each subscales’ internal consistency.

Pearson correlations were used to assess the relationship of CDS scores to scores on WAIS-IV Digit Span, Wechsler Memory Scale-IV LM, and VR. The WAIS-IV scale score of Digit Span was used. Linear regression as described in the Halstead-Russell Neuropsychological Evaluation System-Revised (HRNES-R) manual (Russell & Starkey, Reference Russell and Starkey2001) published by Western Psychological Services and in Russell (Reference Russell1987) was used to assist in the derivation of HRNES scale scores for LM and VR. For the purpose of statistical analysis and data reduction, age-adjusted raw scores were added together on LM-1 and LM-2, and on VR-1 and VR-2. The summary raw scores for LM and VR were then converted into modified z scores with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 10. The HRNES-R scale scores are classified as follows: normal (above 96–112), borderline (90–95), mild (80–89), moderate (70–79), and severe (below 70). Participants’ mean scores (with standard deviation and range) on these tests are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Scoring characteristics (means, standard deviations, and ranges) of the sample

Note. Hs = hypochondriasis; D = depression; Pt = psychasthenia; Sc = schizophrenia.

In addition to evaluating the CDS correlations with the memory tests, correlations were computed to evaluate the relationship between CDS scores and MMPI-2 measures of somatic preoccupation (Hs), depression (D), anxiety (Pt), and disturbed thinking (Sc). To minimize the likelihood of a Type 1 error based on chance findings in conducting multiple analyses, the Holm–Bonferroni sequential correction method was applied (Holm, Reference Holm1979).

RESULTS

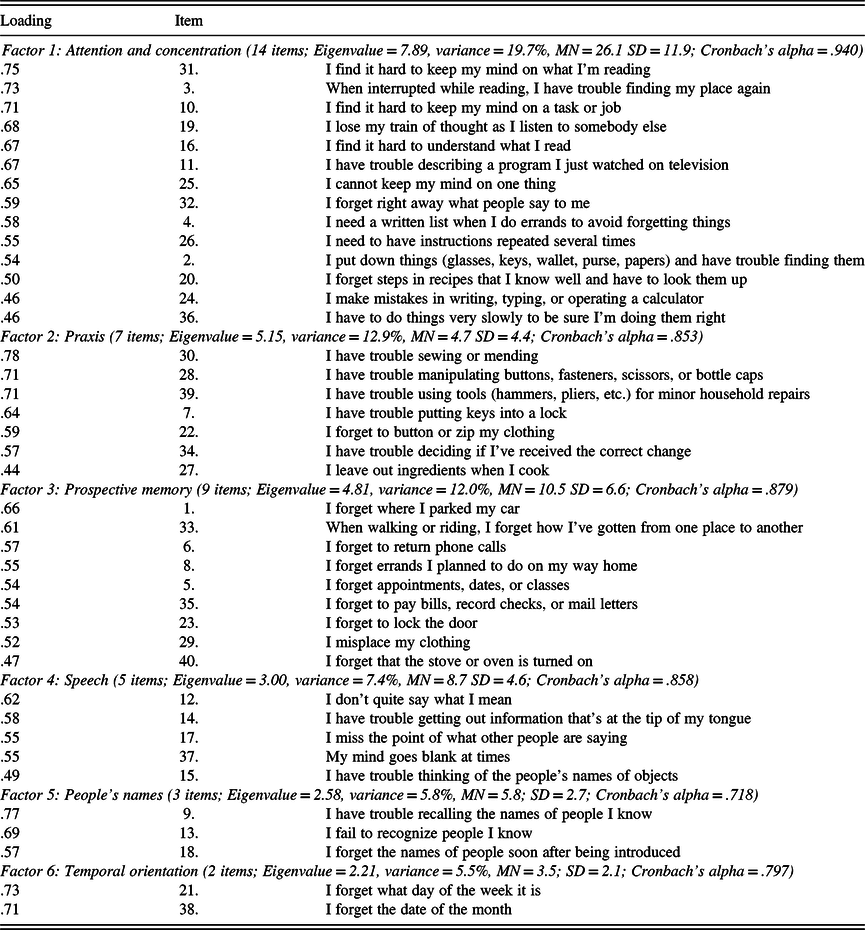

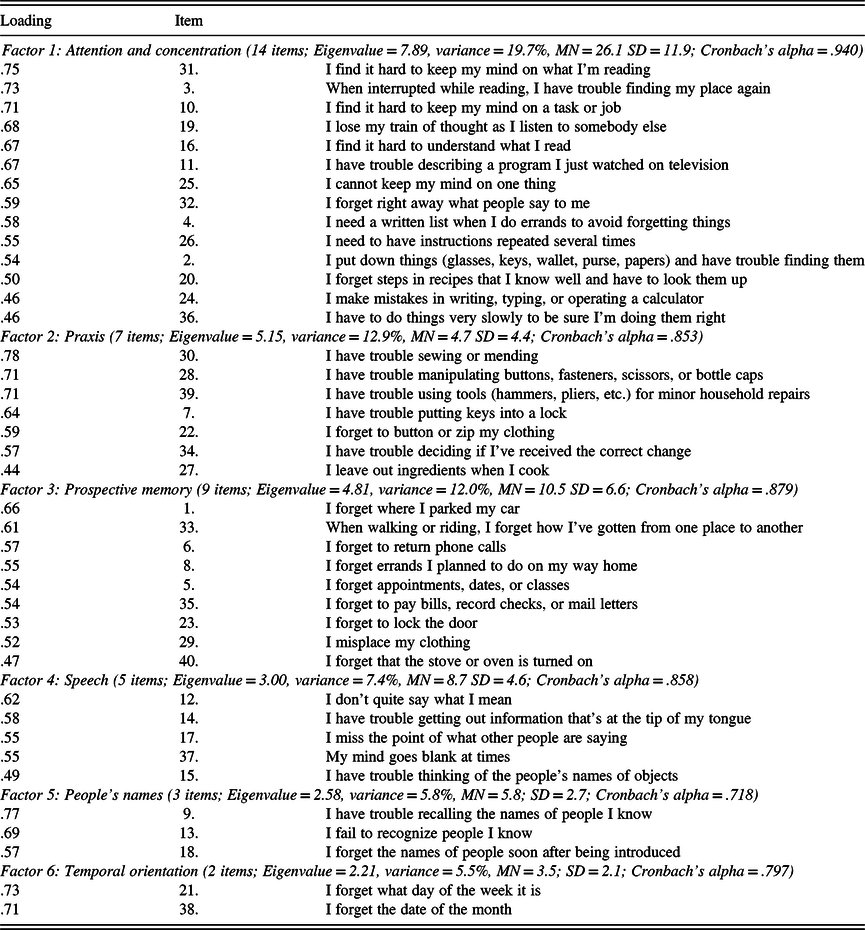

The CDS protocols of 512 participants were subjected to a PCA followed by varimax rotation. The PCA produced six components accounting for 64% of the total variance. An exploratory factor analysis was conducted using varimax rotation. The results are shown in Table 2 with assigned loadings in boldface.

Table 2. Factor loadings for exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation of Cognitive Difficulties Scale items

Note. Decimal point omitted. Factor loadings > .40 are in boldface.

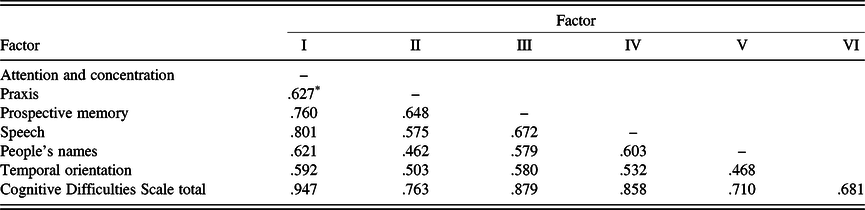

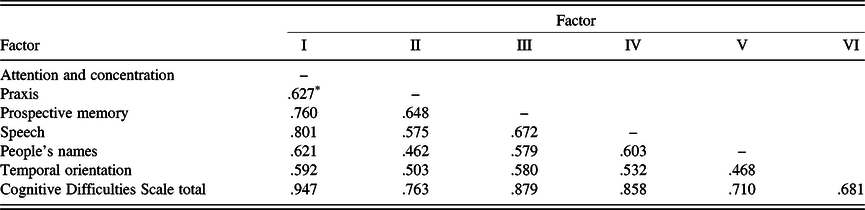

The resulting six-factor solution is similar to the results of previous CDS studies using various samples (Branca et al., Reference Branca, Giordani, Lutz and Saper1996; Gass & Apple, Reference Gass and Apple1997). Intercorrelations of the six factors are shown in Table 3. Table 4 displays the item composition of the six factors (CDS subscales), with their item loadings, mean scores, standard deviations, and internal consistency coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha).

Table 3. Factor score intercorrelations

Note. Factor I = attention and concentration; Factor II = fine motor skill; Factor III = prospective memory; Factor IV = speech; Factor V = people’s names; Factor VI = temporal orientation.

* All ps < .001.

Table 4. Items and loading on the six factors of the Cognitive Difficulties Scale

Note. CDS total (40 items; MN = 59.4 SD = 27.9; 40 items; Cronbach’s alpha = .968).

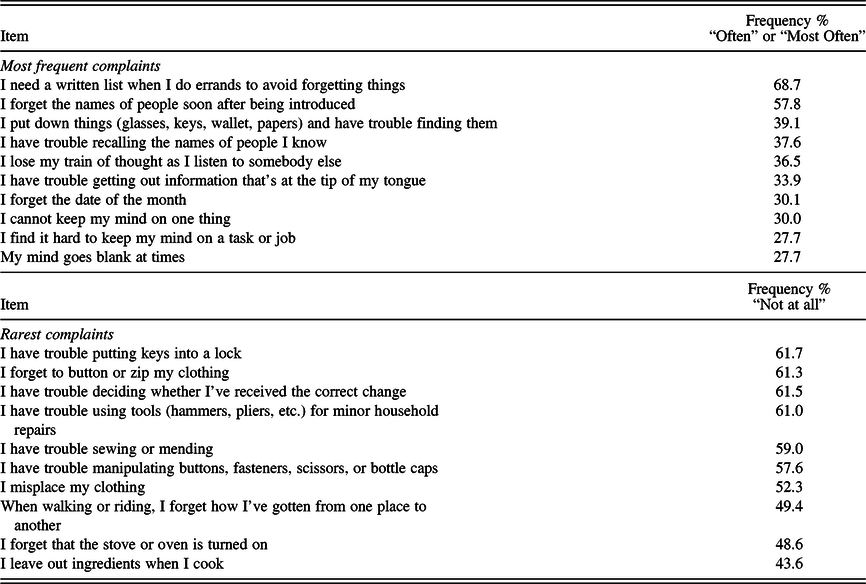

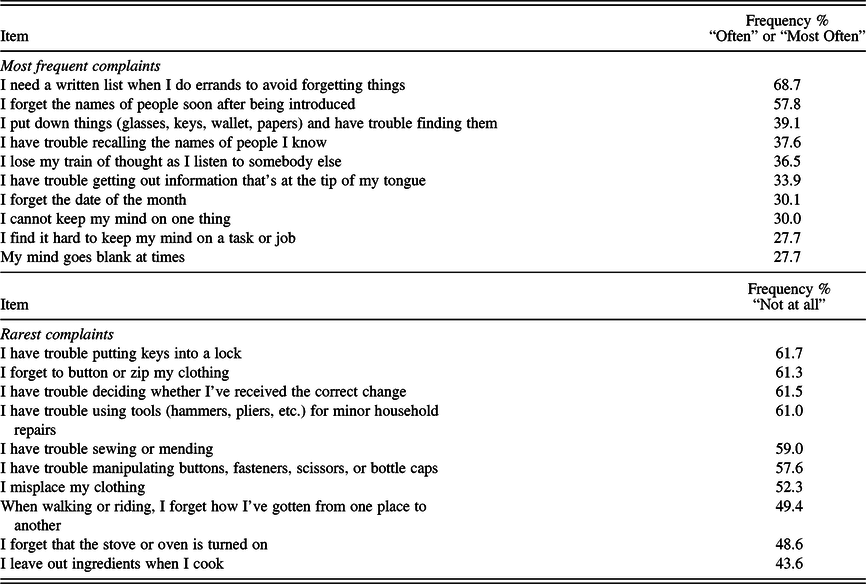

Total CDS Score

Thirty-two participants (6.3%) chose to skip one or more of the 40 items on the CDS. Examinees reported that these items were not addressed because they referred to issues such as sewing or cooking that were not applicable to them. As a result, total scores on the CDS were obtained for only 480 participants. The 40-item revised CDS was statistically examined and found to have six underlying dimensions (Table 4). The CDS has excellent reliability, with an internal consistency of .97 (Cronbach’s alpha). Table 5 displays the 10 most common and least common difficulties reported by this sample. The most common complaint involved needing a list to avoid forgetting when running errands (40% “very often” and 28% “often”). The second most common complaint was immediately forgetting the names of people upon introduction (28% “very often” and 29% “often”). The least common difficulties involved forgetting to use buttons or zippers, and trouble with placing keys in locks, with 90% and 80%, respectively, reporting a frequency of “rarely” or “not at all.”

Table 5. Most and least frequently reported complaints on the Cognitive Difficulties Scale

In describing the role of demographic variables, gender, age, and education were examined in relation to scores on seven measures, including the total CDS and the six factorial dimensions or subscales (Table 6). The Holm–Bonferroni sequential method was used to reduce the risk of a Type 1 error in making multiple (seven) comparisons involving each demographic variable. In performing seven analyses, the sequential alpha level cutoffs are .007, .008, and .01. CDS scores were significantly related to age, r(480) = −.31, p < .001, with younger participants expressing greater difficulties than older subjects. Education was related to CDS total scores, r(477) = −.187, p < .001. Gender approached significance, p = .016.

Table 6. Pearson correlations between cognitive complaint (CDS) measures and demographic variables (N = 480)

Note. CDS = Cognitive Difficulties Scale. **p < .001 and *p < .01, significant using Holm–Bonferroni sequential alpha.

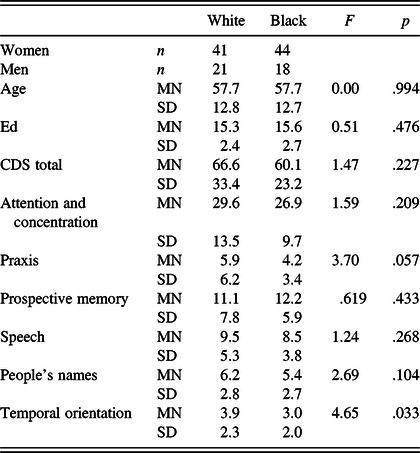

The two racial/ethnic groups comprising the 97% of the study sample were White and Black non-Hispanics. We investigated the possibility of differences between these two groups in cognitive complaints on the CDS. Due to significant intergroup age and educational differences, we matched participants on these two demographic variables, with 62 subjects in each group (see Table 7). The multivariate analysis of mean scores across the seven CDS scores revealed a statistically significant overall effect for race, Wilks’ lambda = .853, F(6,109) = 3.14, p = .007. Although no differences were found for the CDS total score and five of the subscales, one univariate comparison showed a significant difference: Black non-Hispanics had fewer complaints than White non-Hispanics regarding time orientation, F(1,122) = 4.65, p = .033.

Table 7. Interracial differences in self-reported cognitive difficulties using 124 participants matched on age and education

Wilks’ lambda = .853, F(6,109) = 3.14, p = .007.

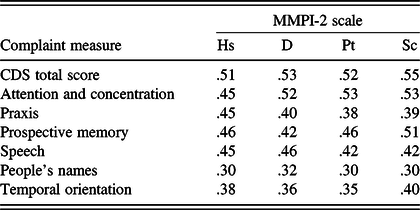

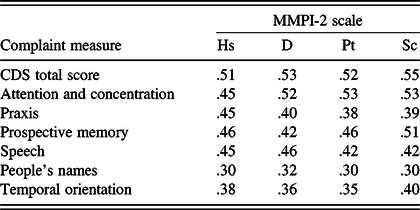

The average CDS item response rating of perceived level of difficulty was 1.5 ± 0.6, where 1 = “Rarely” and 2 = “Sometimes.” The modal response was “Sometimes,” occurring on 40% of the items. The frequency of high scorers with an average CDS response in the range of “Very Often” (>3.5) was 0.4%, and “Often” (>2.5) 7.5%. CDS scores were not related to cognitive performance on Digit Span, LM, or VR (Table 8). However, as shown in Table 9, they were significantly related to level of psychological problems on the MMPI-2 (rs between .30 and .55, ps < .001).

Table 8. Pearson correlations between cognitive complaint (CDS) measures and memory test scores (N = 167)

Note. CDS = Cognitive Difficulties Scale. All ps nonsignificant.

Table 9. Pearson correlations between cognitive complaint (CDS) measures and MMPI-2 scores (N = 167)

Note. CDS = Cognitive Difficulties Scale. All ps < .001.

Factor 1: Attention and Concentration

As Table 3 shows, Factor 1 consisted of 14 items that address attention and concentration, accounting for 19.7% of the total variance. The strongest predictor of scores on this measure was the item, “I find it difficult to keep my mind on what I’m reading.” Women reported more difficulties than men on attention and concentration (Factor 1), r(499) = .145, p < .001. Age was significantly related, r(499) = −.353, p < .001, with younger participants expressing greater difficulties. Education was inversely related to scores on this factor, r(499) = −.182, p < .001. On attention and concentration, the average item response rating of perceived level of difficulty was 1.9 ± 0.4, where 1 = “Rarely” and 2 = “Sometimes.” The modal response was “Sometimes,” occurring on 71% of the items. The frequency of high scores with an average Factor 1 response in the range of “Very Often” was 3.2% and “Often” or more in 21.8%. Factor 1 appears to have measurement potential with a high level of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .94). Scores on attention and concentration were unrelated to test performance on Digit Span, LM, and VR. However, they were significantly related to MMPI-2 measures of depression and anxiety (rs between .45 and .53, ps < .001).

Factor 2: Praxis

This consisted of seven items that primarily address praxis, accounting for 12.9% of the total variance. The strongest predictor of scores on this measure was the item, “I have trouble sewing or mending,” with other items involving the manipulation of buttons, zippers, use of needle and thread, and the manual use of tools. Gender and age had no significant relationship to scores on this factor. Education approached statistical significance (p = .011). On praxis, the average item response rating of perceived level of difficulty was 0.7 ± .1, where 0 = “Not at all” and 1 = “Rarely.” The modal response was “Not at all,” occurring on 71% of the items. The frequency of scores with an average Factor 2 response in the range of “Very Often” was 0.4% and “Often” or more in 1.8%. Factor 2 is a potentially reliable measure with a satisfactory level of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .85). Complaints regarding praxis were less common compared to those involving other dimensions measured by the CDS. Scores on praxis were unrelated to test performance on Digit Span, LM, and VR. However, they were significantly related to measures of depression and anxiety (rs between .38 and .45, ps < .001).

Factor 3: Prospective Memory

This was composed of nine items that address prospective memory, accounting for 12% of the total variance. The strongest predictor of scores on this measure was the newly added item, “I forget where I parked my car.” Gender and education were not related to scores on this factor (rs = .10 and −.12, respectively). However, age was negatively associated with memory complaints (r = −.35, p < .001), with younger participants having more complaints. On prospective memory, the average item response rating of perceived level of difficulty was 1.2 ± 0.4, where 1 = “Rarely.” The modal response was “Not at all,” occurring on 56% of the items. The frequency of high scores with an average Factor 3 response in the range of “Very Often” was 0.8% and “Often” or more in 5.1%. Factor 3 has good reliability, with a satisfactory level of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .88). Scores on prospective memory were unrelated to test performance on Digit Span, LM, and VR. However, they were significantly related to measures of depression and anxiety (rs between .42 and .51, ps < .001).

Factor 4: Speech

Speech consisted of five items that address a variety of problems related to speech, accounting for 7.4% of the total variance. Items on this factor refer to improper speech content, grammatical errors, dysfluency, dysnomia and word finding difficulty, and difficulties with speech comprehension. The strongest predictor of scores on this measure was the item, “I don’t quite say what I mean.” Gender was not a significant factor in reported speech difficulties. Age was related to the severity of reported speech difficulties, r(503) = −.28, p < .001, with the younger participants expressing more complaints. Education was also related to scores on this factor (r = −.19). On speech, the average item response rating of perceived level of difficulty was 1.7 ± 0.3, where 1 = “Rarely” and 2 = “Sometimes.” This difficulty was reported to be “Often” or more in 19.1% of the sample and “Very Often” in 3.6% of the sample. The modal response was “Sometimes,” occurring on 80% of the items. Factor 4 demonstrated acceptable reliability, with a moderately high level of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .86). Scores on speech were unrelated to test performance on Digit Span, LM, and VR. However, they were significantly related to MMPI-2 measures of depression and anxiety (rs between .42 and .46, ps < .001).

Factor 5: People’s Names

Factor 5 was composed of three items, and these refer to recall of people’s names, accounting for 6.5% of the total variance. The strongest predictor of scores on this measure was the item, “I have trouble recalling the names of people I know.” This variable was not related to age, education, or gender. On people’s names, the average item response rating of perceived level of difficulty was 1.9 ± 0.9, where 1 = “rarely” and 2 = “Sometimes.” This difficulty was reported to be “Often” or more in 28.2% of the sample and “Very Often” in 4.7% of the sample. People’s names demonstrated a relatively low and marginally acceptable level of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .72). This factor includes an item, “I fail to recognize people I know,” which taps an infrequent experience, though another factor item, “I forget the names of people soon after being introduced,” was reported to be a very common occurrence. Scores on this factor were unrelated to test performance on Digit Span, LM, and VR. However, they were significantly related to MMPI-2 measures of depression and anxiety (rs between .30 and .32, ps < .001).

Factor 6: Temporal Orientation

Factor 6 consisted of two items that accounted for 5.5% of the total variance. These items address temporal orientation, specifically day of the week and date of the month. The strongest predictor of scores on this measure was the item, “I forget what day of the week it is.” Education was statistically significant in predicting the severity of reported temporal orientation difficulties, r(508) = −.198, p < .001, with the less educated participants expressing more complaints. Gender and age were not related to this CDS dimension. On temporal orientation, the average item response rating of perceived level of difficulty was 1.7 ± 0.9, where 1 = “Rarely” and 2 = “Sometimes.” This difficulty was reported to be “Often” or more in 28.6% of the sample and “Very Often” in 9.2% of the sample. This factor demonstrated acceptable reliability, with a moderate level of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .80). Scores on temporal orientation were unrelated to test performance on Digit Span, LM, and VR. However, they were significantly related to MMPI-2 measures of depression and anxiety (rs between .35 and .40, ps < .001).

Individuals showed significant diversity in reporting the degree of their cognitive difficulties and in their pattern across domains. Many individuals reported having very few problems, and many largely restricted their complaints to a single domain. To assist the clinician in evaluating individuals’ CDS scores relative to other clinical referrals, we include a frequency table with raw, T-score, and percentile conversions (Table 10). Table 10 values are not normative scores based on “healthy normals,” nor are they necessarily representative of patient populations that significantly differ on demographic variables. However, they do provide a basis for making comparisons with other individuals who were referred to an outpatient clinic for memory assessment.

Table 10. Raw scores, T-scores, and percentiles for the Cognitive Difficulties Scale

DISCUSSION

The major purpose of this study was to describe fundamental measurement characteristics of the CDS that would be informative for clinicians who use or consider using this instrument. The CDS requires limited reading skill (fifth grade level) and is relatively quick to administer. The item content mostly reflects common life experiences and is face valid for assessing cognitive difficulties. The CDS is not a homogenous measure but rather a multidimensional scale that appears to tap six domains. In this memory disorders clinic referral sample, the scale’s underlying factorial structure is consistent with that found in a referral sample of veterans with closed-head injury (Gass & Apple, Reference Gass and Apple1997) and in healthy volunteers (Derouesné et al., Reference Derouesné, Dealberto, Boyer, Lubin, Sauron, Piette and Alpérovitch1993). The items of the CDS place varying emphasis across the content domains with the majority of items addressing attention and concentration (35% of items) and memory (prospective and peoples’ names, 30% of items). This content emphasis is characteristic of other cognitive self-report inventories (Rabin et al., Reference Rabin, Smart, Crane, Amariglio, Berman and Boada2015). Less represented are praxis (18%), speech difficulties (13%), and temporal orientation (5%). Regarding the small number of items that can assess subjective complaints involving speech (three items) and/or temporal orientation (two items), further consideration might be given to possible revision and augmentation.

The CDS showed excellent internal consistency. Its underlying factors also exhibited adequate internal consistency, though the temporal stability (test–retest reliability), particularly of the shorter measures, was unexplored. Whether the content validity of the two- and three-item factors reflects an adequate sampling of their respective domains is a question for further consideration. The predictive validity of the CDS has traditionally been assessed using standardized cognitive tests as criteria. To the extent that this criteria selection is appropriate, the overwhelming evidence to date casts doubt on the scale’s validity, because, with few exceptions, the CDS and other subjective self-report measures are generally poor predictors of objective cognitive test performance (Bowler et al., Reference Bowler, Adams, Schwarzer, Gocheva, Roels, Kim and Lobdell2017; Burdick, Endick, & Goldberg, Reference Burdick, Endick and Goldberg2005). However, one might question the appropriateness of judging the validity of a subjective cognitive difficulty rating based solely on its correlation with cognitive test results. As several investigators have emphasized, these tests might be inadequate as external criteria. In specific, standardized cognitive tests and the context in which they are administered are well-suited for measuring cognitive capacity, but as reflections of daily cognitive efficiency they have limited ecological validity (Chaytor et al., Reference Chaytor, Temkin, Machamer and Dikmen2007). Cognitive complaints arise from life experiences in a world that substantially differs from the artificial, structured, distraction-free, time-limited, and highly controlled testing environment. Neuropsychological tests measure what a person can do; self-report measures, in most cases, might be a better representation of what they actually do.

Self-report cognitive complaint measures are important for assessing people’s insight and awareness of their deficits. Cognitively impaired individuals are commonly unaware of their deficits (anosognosia) or display indifference toward them (anosodiaphoria). Under-reporting of cognitive difficulties on the CDS or similar scales by persons with impaired attention and/or memory sometimes reflects failed memory or a loss of other cognitive abilities involved in self-insight (Edmonds, Delano-Wood, Galasko, Salmon, & Bondi, Reference Edmonds, Delano-Wood, Galasko, Salmon and Bondi2014). In these cases, the formal measurement of impaired insight is clinically important and has direct relevance for treatment and safety. Significant others who know and routinely observe the examinee’s behavior might provide more accurate ratings of cognitive difficulties than the examinees themselves. Anosognosia can be assessed using the informant–patient discrepancy on the CDS (Derouesné et al., Reference Derouesné, Thibault, Lagha-Pierlucci, Baudouin-Madec, Ancri and Lacomblez1999; Spitznagel & Tremont, Reference Spitznagel and Tremont2005). A collateral version of the CDS filled out by informants based on observations of the patient had higher correlations with objective cognitive measures than did the self-report versions (Buelow et al., Reference Buelow, Tremont, Frakey, Grace and Ott2014; Okonkwo et al., Reference Okonkwo, Spitznagel and Tremont2010). For this reason, Buelow et al. recommended obtaining caregiver reports with individuals who have mild or worse cognitive impairment.

CDS scores were partially influenced by demographic variables in this sample. Women reported more difficulties than men only on Attention and Concentration. This replicates an earlier finding by Bowler et al. (Reference Bowler, Adams, Schwarzer, Gocheva, Roels, Kim and Lobdell2017). Less educated participants reported greater problems with Temporal Orientation. Younger participants and less educated participants tended to report more difficulties on three measures: total CDS, Attention and Concentration, and Speech. This finding is related to the fact that both groups – the younger and less educated – also had higher levels of psychological disturbance than their older and more educated counterparts, with correlations ranging from −.19 to −.33 across the four MMPI-2 variables (all ps < .001). Our results are similar to those of Bowler et al. (Reference Bowler, Adams, Schwarzer, Gocheva, Roels, Kim and Lobdell2017) and Derouesné et al. (Reference Derouesné, Dealberto, Boyer, Lubin, Sauron, Piette and Alpérovitch1993), who reported higher CDS scores as a function of lower education and psychological disturbance. However, Derouesné et al. reported an increase in cognitive complaints with advancing age. In contrast, in the present setting, age was negatively related to cognitive complaints. We noted that psychological disturbance and associated complaints were more prominent in the younger participants. We have observed that younger referrals to this memory disorders clinic are more likely to be referred due to memory complaints seemingly arising out of psychological issues, whereas older patients were more commonly referred due to a suspicion of possible MCI or dementia even in an absence of self-reported memory difficulties.

In the present study, CDS scores correlated with MMPI-2 measures of psychological disturbance with coefficients ranging from .30 to .53, all ps < .001. As previously noted, the consensus among investigators is that self-reports of cognitive functioning are, at best, weak predictors of cognitive test results. Cognitive inefficiency in daily living is a well-known characteristic of mood disorders (Porter, Robinson, Mahhi, & Gallagher, Reference Porter, Robinson, Mahhi and Gallagher2015), so it might not be surprising that scores on cognitive complaint inventories are significantly associated with levels of depression and/or anxiety (Bowler et al., Reference Bowler, Adams, Schwarzer, Gocheva, Roels, Kim and Lobdell2017; Branca et al., Reference Branca, Giordani, Lutz and Saper1996; Buelow et al., Reference Buelow, Tremont, Frakey, Grace and Ott2014; Burdick et al., Reference Burdick, Endick and Goldberg2005; Burmester, Leathem & Merrick, Reference Burmester, Leathem and Merrick2016; Chaytor et al., Reference Chaytor, Temkin, Machamer and Dikmen2007; Crumley, Stetler, & Horhota, Reference Crumley, Stetler and Horhota2014; Derouesné et al., Reference Derouesné, Dealberto, Boyer, Lubin, Sauron, Piette and Alpérovitch1993; Edmonds et al., Reference Edmonds, Delano-Wood, Galasko, Salmon and Bondi2014; Gass & Apple, Reference Gass and Apple1997; Hill et al., Reference Hill, Aschwanden, Payne and Allemand2020; Okonkwo et al., Reference Okonkwo, Spitznagel and Tremont2010; Stillman, Madigan, Torres, Swan, & Alexander, Reference Stillman, Madigan, Torres, Swan and Alexander2020; Yates, Clare, Woods, & MRC CFAS, 2015).

The importance of a systematic approach to assessing self-reported cognitive difficulties can be seen in longitudinal studies designed to evaluate the relevance of subjective cognitive complaints for actual mental decline. Some investigators have maintained that subjective complaints predict cognitive decline at an earlier stage than objective tests that fail to detect the deficits (Dardenne et al., Reference Dardenne, Delrieu, Sourdet, Cantet, Andrieu, Mathiex-Fortunet and Vellas2017; Dufouil, Fuhrer, & Alpérovitch, Reference Dufouil, Fuhrer and Alpérovitch2005; Rabin et al., Reference Rabin, Smart, Crane, Amariglio, Berman and Boada2015; Reisberg & Gauthier, Reference Reisberg and Gauthier2008). However, it is questionable whether the objective tests cited in these studies are highly sensitive and sufficient to detect early cognitive changes (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Bangen, Weigand, Edmonds, Wong, Cooper and Bondi2020). The claim that cognitive complaints have such predictive validity has been seriously challenged by the findings of numerous research studies that suggest that a large majority of individuals with SCD in both memory clinic and community-based cohorts do not progress to any type of dementia but rather remain cognitively normal (e.g., Edmonds et al., Reference Edmonds, Delano-Wood, Galasko, Salmon and Bondi2014; Jessen et al., Reference Jessen, Amariglio, Buckley, van der Flier, Han, Milinuevo and Wagner2020; Slot et al., Reference Slot, Sikkes, Berkhof, Brodaty, Buckley, Cavedo and van der Flier2018). Nevertheless, some investigators are attempting to develop an office tool using selected cognitive complaints that might identify individuals who are at risk of progression to dementia (Buelow et al., Reference Buelow, Tremont, Frakey, Grace and Ott2014). If achievable, predictive success is most likely to emerge out of a multifactorial approach that also includes familial/genetic considerations, biomarkers, and other objective data. The value of cognitive complaints as predictors is probably closely intertwined with emotional status. For example, a substantial body of evidence suggests that Major Depressive Disorder is a risk factor for dementia and may predispose people to cognitive decline in both early and late onset variants (Brzezińska et al., Reference Brzezin´ska, Bourke, Rivera-Hernández, Tsolaki, Woz´niak and Kaz´mierski2020; Ezzati, Katz, Derby, Zimmerman, & Lipton, 2020). Diniz, Butters, Albert, Dew, and Reynolds (Reference Diniz, Butters, Albert, Dew and Reynolds2013) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis including longitudinal studies with 49,612 subjects. Their results supported the association between depressive disorders and dementia, finding evidence of a 2.53-fold increased risk for vascular dementia and 1.85-fold increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

The present study has significant limitations that will hopefully be addressed in future investigations. Measurement characteristics of the CDS found herein might not generalize to other types of assessment settings or with different samples. The present sample consisted of individuals who were predominantly White, over 60% women, and relatively well-educated (MN = 14.7 years). The study’s participants lack some of the important demographic characteristics that are present in many clinical settings. Therefore, the norms provided herein should be cautiously applied. Nearly, all cases were referred to evaluate for possible MCI or early dementia and did not include persons with moderate or more severe dementia. All participants were able to read the CDS and complete the Likert-type scale. Few had a known history of brain disorder. For these reasons, the present findings might not generalize to other neuropsychological samples.

Further investigation could significantly improve on the current study through follow-up research that examines the test–retest reliability of the CDS and its subscales across a broader sample with greater racial and ethnic diversity. An additional focus would be determining if subscales of the CDS provide predictive information about cognitive ability in healthy individuals and in persons with cognitive dysfunction. Research should also address the psychometric characteristics of a collateral version of the CDS. Informant reports that incorporate the CDS should prove helpful to clinicians in acquiring a more complete picture of patients’ cognitive efficiency in performing routine daily tasks.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have nothing to disclose.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research described here was not funded or financially supported.