I INTRODUCTION

The Arch of Janus is one of the best preserved monuments from the Forum Boarium, but at the same time one of the least known. Despite being one of the most emblematic Roman buildings from the fourth century a.d., its typology, chronology and historical significance have not been fully discussed.Footnote 1 In order to address the paucity of investigations carried out on the building, a new research project was initiated with the aim of analysing different aspects related to the architecture and chronology of the monument.Footnote 2 The background to this project dates to 1993, when the Spanish School of History and Archaeology in Rome proposed carrying out an analysis of the structure within the wider panorama of monumental arches in the Western Roman Empire. Unfortunately, the car bombing in July 1993 of the nearby church of San Giorgio al Velabro led to a delay in the start of the project. The aim of this article is to present the most significant results of this project, which we believe provides a substantial amount of new information about the Arch of Janus.

With the aim of clarifying some of these complicated issues, we have made new graphic documentation of the arch and published the first complete photogrammetric elevation of the monument.Footnote 3

Another aspect dealt with in this article is the definition of its architectural features. This process was helped significantly by new archaeological excavationsFootnote 4 both on the inside and outside of the arch, which have revealed important architectural elements, such as its foundations. It was also possible to verify the presence of a two-lane road that ran underneath the building in all four directions.

Developing the new planimetric view has been fundamental in making a stratigraphic reading of the vertical faces of the monument, allowing us to define the different historical transformations that were made and to analyse the source of the materials that were re-used in its construction. With regard to this re-use of materials, we provide new data on the internal organization of the work and the supervision of such a complex construction project.

However, the most significant new data regarding the chronology of the monument come from a new inscription from the period of Constantine that was found re-used in the structure of the north-east pillar of the arch, which makes it possible to definitively date the arch from the time of Constantius II. Based on this dating, we propose the reconstruction of the highly fragmented dedicatory inscription, which has been kept in the church of San Giorgio al Velabro since the eighth century.

II CONSTRUCTION, TRANSFORMATION AND RE-USE IN THE ARCH OF JANUS

The identification of the Arch of Janus as the Arcus Divi Constantini referred to in the Cataloghi Regionari in Regio XI is accepted by the majority of academics.Footnote 5 However, there are still numerous questions that leave open a variety of hypotheses about the history of the Arch of Janus. The main doubts relate to the function of the monument, its precise chronology, the topographical distribution of the buildings in the Forum Boarium in the fourth century a.d., and the rôle of the monument in the characterization of the urban landscape at that time.

The most plausible explanation of its function is that it was a triumphal archFootnote 6 associated with processions that were diverted from the Vicus Iugarius towards the Vicus Tuscus before reaching the Forum;Footnote 7 this seems more likely than a structure that was only built as a covered space for traders and business transactions in the Forum Boarium.Footnote 8 The hypotheses surrounding the date of its construction suggest that it was built during the period of ConstantineFootnote 9 or afterwards,Footnote 10 although without any general agreement as to the urban layout of this part of Rome at this time. The chronology generally seems to be confirmed by the building technique used and the stylistic elements associated with the sculptures on the keystones of the external arches of the tetrapylon.Footnote 11

The Arch of Janus stands on the former boundary between the Velabrum and the Forum Boarium, close to the Arcus Argentariorum from the time of Septimius Severus, and the church of San Giorgio al Velabro. We know little about when it came to form part of the urban layout of the time due to a lack of available data. It has been suggested that there was a square nearby, probably from the third century a.d.,Footnote 12 as different findings of paving stones have been made close to the monument.Footnote 13 The building stands at a crossroads, with the first road heading from north to south and the second from east to west, connecting the Forum Boarium and the Palatine Hill. Finally, following archaeological excavations carried out in the area, it has been possible to identify a long section of this road (Fig. 1) connected to the arch. This road, which is quite well preserved, seems to have been in use for several centuries and to have undergone changes at different periods. This discovery has made it possible to include a paved road in this part of the Forum Boarium, an element that needs to be evaluated if we consider the hypothesis that there was an enclosed square alongside the Arch of Janus. The results of these excavations include the possibility that the street was in use until the high medieval period, specifically until the construction of the church of San Giorgio al Velabro in the late Middle Ages.Footnote 14

FIG. 1. General view of the Arch of Janus and a section of the road between the Forum Boarium and the Palatine Hill.

The arch has an internal core made of opus caementicium, with an external covering of large marble blocks that were re-used and re-carved from one or more buildings on a colossal architectural scale.

The foundations of the monument were built as a wide platform beneath the four pillars of the arch; due to subsequent destruction and the limited scope of the excavations it has not been possible to document the actual size of the foundations as they are so wide. Large blocks of Travertine limestone were used, fitted closely together in a grid structure, alternated with a red mortar with an unusual consistency (Fig. 2 a and b). As a result of the restoration work carried out after the car bombing in 1993, an inscription was found on the outside edge of one of the blocks in the north-east pillar of the arch with letters 13 cm high: ‘ARCI’.Footnote 15 This was a very important discovery in terms of defining some of the dynamics associated with the spolia process and the transportation of construction elements to create the new building, made with re-used materials all the way from its foundations.

FIG. 2. Archaeological excavations in the foundations of the north-west pillar and detail of the construction technique, showing mortar in the joints between the blocks.

It is also interesting in terms of understanding how the arch was built, as the re-use of materials was a systematic operation with precise rules for the process of dismantling, transporting and re-assembling them for the new structure. As discussed later on, we also documented the same inscriptionFootnote 16 on another re-used architectural element inside the span where steps lead up to the top of the building.

The pillars, which are more or less square, are divided up into a large plinth with a moulded base surrounded by a protruding ledge; a first section with three niches on each outer side and another protruding ledge where the arches on the façade start; and a second section, which like the first has three niches on each side, reaching to the highest part of the extrados of the arches. The niches on the west and east façades and the central niches on the north and south façades, because of their depth and regular construction, may have contained a series of statues which we are no longer able to identify. However, the side openings on the north and south sides are false, shallow niches, which could never have contained statues; it is likely that these spaces were decorated with bas-reliefs or paintings. The top parts of the niches have a scalloped effect. In the north-west pillar there is a door with a staircase that leads to the attic of the arch, via a series of steep ramps.

The façades of the monument once had protruding architectural features which have now been lost, both surrounding the niches and an entablature which continued above the arches.Footnote 17 The four main arches and their external coverings with archivolts started at the upper part of the protruding ledges that separated the first and second sections of the façades. These are moulded archivolts with keystones in the shape of a bracket that contain the only indications of the figurative designs used on the arch: on the western and eastern façades, Rome and Juno, and on the northern and southern façades, in a badly damaged condition, Minerva and Ceres.Footnote 18 Unlike the external surfaces of the monument, the four semi-circular arches have a series of regularly carved blocks that form four virtually independent, functional structures that support a ribbed vault made of opus caementicium edged in brick. On the inside of the vault, ceramic insets are used to reduce its weight.Footnote 19

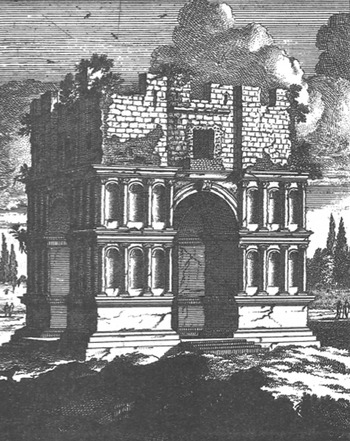

The appearance of the monument has changed significantly over the years, due to the loss of many of the architectural decorations and sculptures from its façades and niches, and also as a result of the demolition, in 1830, of the remains of the attic on top of the building. The absence of these remains, which are documented in paintings and illustrations of the arch, has made it possible to suggest a wide range of hypotheses for the reconstruction of the structure that once crowned the monument. In images from before the demolition in 1830, a structure made of brick can be seen, which may have been covered with marble slabs. More detailed illustrations also reveal restoration work carried out on the attic with a structure made of small regularly cut blocks superimposed over the brick structure (Fig. 3). The shape of the attic must have coincided with the lower part of the building, in line with the protruding elements of the four large square pillars, and another section aligned with the extrados of the arches.

FIG. 3. Detail of an illustration by P. Schenck with remnants of the upper part of the Arch of Janus. (From G. Malizia, Gli archi di Roma (2005))

In our opinion, this evidence rules out the possibility of reconstructing the attic with a pyramid, something that seems to have found favour in certain historiographical references to the building.Footnote 20 As a result of the restoration project that took place after the car bombing in 1993, archaeological excavation work was carried out on the upper part of the monument, revealing a series of structures whose layout suggests the presence of a square ambulatory that ran around the perimeter, together with a rectangular room at the same level.Footnote 21 These data would point towards a simpler reconstruction of the attic, in line with the archaeological evidenceFootnote 22 (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4. Reconstruction proposed by Carandini (Reference Carandini2012: Tav. 178).

III STRATIGRAPHIC ANALYSIS

As a part of this project, a systematic stratigraphic analysis was carried out on the Arch of Janus with two main objectives. The first was to define the different interventions carried out on the monument after its construction, and the second was to associate the original phase with an initial proposal for a map of the different types of archaeological elements re-used in its construction.

The stratigraphic analysis of the monument offers a summary of the results that have been achieved, shown in Fig. 5. In this case it was essential to create a new, uniform graphic documentation of the archFootnote 23 making it possible to create a series of diagrams showing the different transformations the monument has undergone throughout history. Unfortunately, at the current stage of this project it is impossible to assign a specific chronology to the different transformations we have documented. These are all interventions that are highly evident on the exposed surfaces of the arch, but which nevertheless are difficult to attribute to a specific date. On the elevations that are presented it is possible to see a series of actions that have been carried out on the surface of the monument which to some extent are repeated systematically on all of its internal and external surfaces.

FIG. 5. Photogrammetric surveys of the monument with stratigraphic analyses of the elevations.

The construction stage when the large blocks and architectural elements were added, shown in white, is associated with a process of transformation of the construction elements, most of which were re-used, transforming the original element into a new piece of the Arch of Janus. It has been possible to identify a large number of blocks in the monument whose re-working has left clear signs of this stage associated with work on building the arch. The elements shown in green have details on their surface from some kind of previous use, despite the fact that it is only possible to identify their original function in a few cases. The presence of these details has resulted in a number of comments regarding the management of the ‘cantiere’. In our analysis we have found that these elements were fitted in place in two different ways: firstly, by re-shaping material on the building site itself, before it was added to the structure, and a second way that involved adapting them to the other pieces that had already been fitted in place, affecting their external surfaces and points of contact. In many cases, due to the position of the pieces, it is difficult to identify at what stage the work was carried out, and so we have marked all of the elements that have obvious signs of these stages. These are generally elements of different shapes and sizes ranging from pieces of friezes, architraves, cornices to bases or monumental blocks, whose original decorative elements or mouldings have been removed. Amongst the elements we can see that were clearly eliminated after they were added to the arch we have the winged Victory and cornucopia on the outer north elevation, the frieze decorations on the internal west elevation (Fig. 6 a, b and c),Footnote 24 the fragments of cornices distributed in the sections separating the pillars, at the height of the impost of the arches, and finally, the holes for staples that were used to hold the large blocks in place on the inside of the arch when they were first installed.

FIG. 6. Decorative elements from sections that were re-used in the construction of the arch. (a) Detail of the winged image of Victory eliminated as the architectural element was fitted in place; (b) architectural element with Bügelkymation eliminated for re-use as a block in the north-west pillar; (c) detail of the Bügelkymation in the cornice of the Hadrianic Basilica Neptuni.

One of the activities that has considerably affected the present-day appearance of the monument has been the systematic theft of the metallic staples that held the marble blocks in place, on nearly all of the joints, which in some cases have very large holes. This situation, which is common in many buildings in Rome and throughout the rest of the Roman world, has very important consequences in terms of the degradation of the building, due to water filtering into the core of the structure and causing stability problems. The traces of this activity, marked in red, traditionally dated to Late Antiquity, are distributed uniformly over all of the structure of the Arch of Janus from the bottom to the top. This means that a specialized workforce must have been involved in removing metals from ancient buildings with systems that probably involved scaffolding or other moveable structures to reach inaccessible areas.

Little evidence remains of the use of the arch in medieval times; it is only seen in the internal elevations as a series of square orifices, all of which are at the same height in the central part of the pillars. The size and type of the holes are clearly associated with the use of load-bearing wooden beams for defining horizontal levels. These holes may have been used for an internal division of the arch, to create an intermediate floor the purpose of which is unknown.

We also believe that it was in this period that an opening was made in the external west elevation of the monument, transversally piercing the width of the pillar as far as the impost of the façade arch. The presence of another rectangular opening beneath the highest point of this mark suggests that a structure was connected to it with a roof that sloped towards the interior of the arch. As we lack any other information associated with this structure, we are unable to define its type or purpose.

We have been able to identify a series of restoration projects carried out on the monument in different historic periods. After analysing the existing graphic documentation on the Arch of Janus, we can attribute the first interventions to restore the monument to the early nineteenth century, marked in dark blue, when work was carried out at the bottom of the pillars on the external east elevation, and in the southern corner of one of the niches in the second level.

In the 1960s, the current roof of the building was built, shown in orange, consisting of a thick layer of concrete protecting the structure, with protrusions over the façades of the arch, visible on all four sides. It is possible that this same restoration project was responsible for the concrete patches, marked in yellow, covering the orifices in the internal south elevation and on the pillar of the internal east elevation.

Finally, the last restoration work carried out after the car bombing in 1993 is marked in light blue; this was mainly to repair a series of holes that were causing leaks, mostly on the outer surfaces of the four sides of the arch, from the bases, pillars, niches, and connecting points between the arches on the façade and the niches.

IV RE-USE OF MATERIALS

In this new architectural analysis of the Arch of Janus, we have proposed identifying the materials that were re-used in its construction, as in many cases it is possible to identify the original architectural element from which they were taken, due to the partial remodelling of their surfaces when they were included in the monument.Footnote 25

In this case it is necessary to explore some of the details of the architectural elements included in the arch, as some of them underwent such a specific ex profeso remodelling process that it is difficult to identify the original element. This is the case of the upper, middle and lower cornices of the pillars, or the elements on the four arches on the façade that are carved with specific elements for the Arch of Janus, without any functional re-use of similar blocks (Fig. 7). The remodelling process would have been carried out by workers who were specialists in the architectural decoration of their time, and who were responsible for creating the main elements that defined the appearance of the monument.

FIG. 7. Detail of the new cornices created for the Arch of Janus.

In the process of re-using the material to build the arch, there are elements that raise questions about the management of the ‘cantiere’, such as the workers who built the structure. According to P. Pensabene and C. Panella,Footnote 26 the only architectural elements that would allow us to recognize the artisans who worked on the arch are the elements that are contemporary to the arch ‘those with a plain astragal between the bands, similar to those seen in the archivolts of the arches, and those with plain bands that can be considered as semi-completed’.Footnote 27 Based on this observation, which is obvious in a systematic analysis of the kind carried out for the publication in question, it is clear that two groups of artisans were involved in organizing and assembling the pieces taken from other architectural structures. These would have been a large initial group specializing in the technique of assembling re-used materials and adapting them to new structural and decorative functions, and a second group dedicated to creating new architectural elements, focusing on specific commissions for the most recognizable parts of the monument, such as the arches in the façade and the cornices over the pillars. It is likely that these two groups worked together at the same time in the different stages of building the monument.

The most interesting piece of data resulting from this analysis is that there was a very well organized process behind re-using these materials that involved a series of complex operations, typical of a production cycle, ranging from the recovery of the material through to its transportation and re-assembly in a completely new architectural style. These processes can be completely reconstructed in the Arch of Janus. The presence of two similar inscriptions of the word ‘ARCI’ suggests that sections other than marble slabs were marked in the location from where they were removed. In this specific case, the carvings were not removed during the remodelling process, as they are on a block that is concealed in the foundations of the monument, and on a section in the inner core of the stairwell leading to the attic.

Because of their quality and finish, we have been able to identify the original architectural elements of a number of fragments included in the monument. These fragments (Fig. 8) are mainly located on the outside of the arch. The majority are fragments of cornices on the inside and outside of the north, south, east and west façades; two pieces of column shafts on the west façade; seven fragments of friezes on the north, south, east and west sides; an angular base moulding in the north face of the arch; and finally, on the east side, a pedestal from a statue that forms the upper and side section of the central niche on the first level. This last element has been found to bear an unknown inscription which has helped to clarify the chronology of the Arch of Janus, and which forms a part of the epigraphic elements we have been able to document in the structure.

FIG. 8. Photogrammetric surveys indicating the original architectural elements before their re-use in the arch.

As a conclusion to this analysis, we can state that most of the Proconnesian marble blocks that were documented do indeed come from the Temple of Venus and Roma, as previously suggested by Pensabene and Panella. This can be inferred from the stylistic study of the remains of a cornice in the north-west pillar (Fig. 6 b–c), in which the shadow area of the Bügelkymation (in the shape of two parallel triangles) is reminiscent of the style from the time of Hadrian, as well as the dimensions of the large slabs from the interior of the pillars, whose scale is similar to the cornices from the same temple.

Obviously, fragments were re-used in the arch from other monuments that were not from the time of Hadrian, such as the scroll frieze on the south-west façade from the end of the second century a.d., a number of Carrara marble blocks, and a number of elements that were created long after the temple was built, dated by Pensabene and PanellaFootnote 28 to the end of the third or early fourth century a.d. (Fig. 17, top). Unlike other monuments, such as the Arch of Constantine, where the blocks of spolia are obvious and were included as a sign of prestige and for ideological reasons, in our case the re-used material was not made visible and was completely re-shaped in order to conceal its origin, thereby making the sculptural programme of the niches in the arch all the more relevant. The sections that still contain remnants of their original decoration are concealed by the adjacent architectural elements.

V THE EPIGRAPHIC DOCUMENTATION

The Arch of Janus and the stone blocks of which it is made — mainly spoliaFootnote 29 — have been used throughout history as a complex support for numerous inscriptions of different kinds, created for different reasons and purposes, using different writing techniques, with different contents and from different periods. In this article we examine all inscriptions dating from the Roman period which can help us to understand the process behind the construction of the arch, the date of its inauguration, its purpose and the source of the spolia used in its construction. We also analyse some of the late Roman inscriptions that provide information about the process behind the plundering of the architectural ornamentation and its chronology. There are eight tituli in total, most of which are unpublished; we have grouped these into three different categories in the catalogue:

-

Group A: These are epigraphs that were already on the blocks used to build the monument, prior to their being used as spolia. As a result they provide a terminus post quem for when the building was inaugurated.

-

Group B: These are texts from the time the arch was being constructed, including masons’ marks or construction signs, and what may be the dedicatory inscription that was originally in the attic and is now in the church of San Giorgio al Velabro.

-

Group C: Graffiti carved on the surfaces of the arch during the first few centuries of its existence.

Catalogue of Inscriptions

A-1. South-east pillar, south face: row of blocks on the entablature (missing) of the first level of niches (Fig. 9 a; Fig. 8 d). Block of Proconnesian marble with the shortest edge facing outwards, with the inscription on the visible side but running vertically. If we change the direction of the block to match the text, it would measure 72 cm high by 100 cm wide, with an unknown depth. The space containing the inscription was chipped away using a chisel — quite unsuccessfully — in order to remove the traces of the letters. In all likelihood this would have consisted of a first line of text and possibly a second line below it that was shorter and centred, whose letters did not reach the block in question. This is an inscription with holes used to hold gilded bronze letters (litterae aureae), around 29 cm (1 pes) high. The re-carving of the inscribed face to re-use the block in the structure of the arch has led to the disappearance of all of the mortises except those that contained the last two letters (Fig. 9 b). For the previous letters there are only remnants of eight holes, deeper than the mortises and approximately rectangular in shape, used to anchor the bronze letters to the marble using prongs or bolts held in place with lead. In this case, these holes seem to be in line with the shape of the letters,Footnote 30 and so they can be read. The first five are clearly from an M and the next three from an A, so we can read:

[---]MAXI[---] / [---?]

FIG. 9. (a) Remnants of inscription A-1 on a row of blocks over the entablature of the first section of niches on the south face of the south-east pillar. (b) Detail of the lettering of inscription A-1.

This inscription was previously observed by Pensabene and Panella,Footnote 31 who could only read the X. If we consider the ostentatious epigraphic technique used and the size of the letters, similar to those in the dedicatory inscription of the Arch of Septimius Severus in the Roman Forum,Footnote 32 then this would have been an imperial inscription that was originally on a public building which was subsequently plundered to build the Arch of Janus. The word that still remains could have been an imperial title from the second century, due to the use of Proconnesian marble, referring to the pontifex maximus or to the cognomen devictarum gentium of an emperor from after the time of Commodus. In Rome, inscriptions with litterae aureae are relatively abundant from the time of Augustus to Caracalla, while they were used significantly less from the time of Caracalla to Constantine.Footnote 33 On the last two blocks in the same row, to the right of the one described above, there are scattered remains of irregular holes filled with lead, which may have formed part of the same monumental inscription. However, the surfaces were carved much more deeply by the masons who worked on the arch, so this cannot be verified, as none of the anchoring holes remain or the outline of any of the mortises.

A-2. North-east pillar, east face, first (lower) row of niches, in the central niche. Block of Proconnesian marble with the carved shell-vault of the niche. The inscription is on the outer edge, although it is turned to the left (Fig. 10 a). The block measures 157 by 93 by (60) cm. The work carried out by the masons to highlight the mouldings of the small arch removed all of the letters, except those that are on the most prominent surface, just above the external archivolt of these mouldings (Fig. 10 b). Here, using capital letters 10 cm high, in the narrow style typical of the third to fourth centuries a.d., are three superimposed lines with a wide line spacing of around 13 cm. They read:

------

[---]M[---]

[---] + [---]

[---]SE[---]

------?

FIG. 10. (a) Remnants of inscription A-2 in the central niche of the first section, on the east face of the north-east pillar. (b) Detail of inscription A-2 on the upper part of the archivolt of the niche.

Judging by the dimensions of the block and the size of the letters, it would seem that it was once the central section of a pedestal. Line 3 may possibly be the imperial formula: ‘Se[mper Aug(usto]’.

A-3. North-east pillar, east face, first (lower) row of niches, in the central niche. Just below the previous inscription, on the block that forms the right pilaster of this niche (Fig. 10 a). It is the central section of a statue pedestal in Proconnesian marble. The inscribed side is not visible, and has been embedded in the stonework of the niche (Fig. 11; Fig. 8 a). Cracks in the adjacent block on the left-hand side made it possible to identify the inscription. The visible part on the surface of the arch is the base of the pedestal, on which the mouldings of the pilaster of the niche were carved. The block is 94 cm high by 66 cm wide by 66 cm deep. The carved side has embossed characters surrounded by a moulding with listels and beading, 6 cm wide, whose upper left-hand corner is visible. Only the start of the first three lines of text remains, with letters 5 cm high and an ordinatio starting in the central axis, which means that the indent progressively increases on each line. The letters have a strongly printed appearance, especially the F and L, which has a curved, extended foot that stretches below the following letter A (Fig. 12). The words are separated by commas. The text reads:

Domino·N[ostro]

Flavio·Va[lerio]

Constant[---]

------

FIG. 11. Location of the new unpublished inscription A-3 re-used in the construction of the north-east pillar of the arch, east face.

FIG. 12. Detail of inscription A-3.

This is clearly an imperial dedication, judging by the royal dative used in line 1. The pedestal would have supported a statue of Constantius I or his son Constantine, as both emperors shared the names Flavius Valerius.Footnote 34 The letters VA in the second name can only be seen with some difficulty, but they can be felt to the touch. It is essential to clarify to which emperor this refers in order to define the terminus post quem of the construction of the Arch of Janus. In fact, Constantius I was named Caesar of the first Tetrarchy on 1 March a.d. 293, promoted to Augustus in the second Tetrarchy on 1 May a.d. 305, and died on 25 July a.d. 306. His son Constantine was proclaimed emperor on the same date, dying on 22 May a.d. 337. If we consider that the legislation de maiestate protected the quasi-sacred imperial statues,Footnote 35 the re-use of this pedestal and its statue allows us to safely date the construction of the arch to after a.d. 307 (after the death of Constantius) or otherwise after a.d. 337 (after the death of Constantine). We believe that three factors make it much more likely that the pedestal belonged to Constantine:

-

a. Only one pedestal of a statue dedicated to Constantius I is known in Rome, compared to nine dedicated to his son Constantine.Footnote 36

-

b. In the rest of the Empire, only two inscriptions dedicated to Constantius I included the expression Domino Nostro in full and unabbreviated form,Footnote 37 compared to ten inscriptions dedicated to Constantine.Footnote 38

-

c. And above all, none of the inscriptions dedicated to Constantius have the same formula as used in this example (with Domino Nostro and Flavio Valerio in full), compared to eight examples dedicated to his son.Footnote 39

The fact that the following epithets are missing, concealed from view, means that we cannot offer a more precise date for the pedestal during Constantine's lengthy reign.Footnote 40

From this analysis, we can reach a number of basic conclusions:

-

1. Work on building the Arch of Janus was completed after 22 May a.d. 337, when Constantine died close to Nicomedia. Compared to the Constantinian chronology of the monument defended by P. Pensabene,Footnote 41 we believe the project must have been commissioned by Constans, Augustus of the West between a.d. 337 and 350; or even more likely, a project dedicated to Constantius II between a.d. 350 and 361, as suggested by M. Torelli and F. CoarelliFootnote 42 and accepted by the latest bibliography.Footnote 43 The position of the arch on the triumphal percorso Footnote 44 supports the idea that it was associated with the triumphal celebrations held in Rome by Constantius II during his only stayFootnote 45 in the Urbs, between 28 April and 29 May a.d. 357, when he also commemorated a unique imperial anniversary.Footnote 46 Based on the account of this visit given by Ammianus Marcellinus we can ascertain that the emperor decided to contribute to the beauty of the city, although this author only refers in this case to the erection of an obelisk in the Circus Maximus. However, in another passage, he refers to the emperor's taste for triumphal arches.Footnote 47

-

2. In the process of building the Arch of Janus, old pedestals (Cat. A-3 and probably Cat. A-2 too) that were dedicated to the emperor Constantine, the father of Constantius II, were re-used as spolia. We believe that the statues that stood on these pedestals were probably used to decorate the niches in the arch.Footnote 48 This is especially likely if we consider the very large number of statues dedicated to Constantine that must have stood in RomeFootnote 49 and that on his death, Constantine was consecrated as Divus, giving his images a somewhat sacred quality.Footnote 50

-

3. Decorating an arch dedicated to Constantius II with these statues of Constantine would serve to reinforce the dynastic nature of the monument, and can be understood within the context of the re-use of sculptures and translatio statuarum Footnote 51 that was in fashion in the fourth century a.d. This ornamentation can be further justified if we accept that the building could also have been dedicated to the Divus Constantinus and his son, as was the case with other arches from the Severan dynasty. This would also explain the reference to the monument in the Notitia Urbis as the Arcum divi Constantini. Footnote 52

B-4. At the base of the travertine foundation slabs of the north-east pillar, on the east face, one of the blocks has the word ARCI carved into the outer vertical edge in rough letters 13 cm high.Footnote 53 This would seem to be a reference using the genitiveFootnote 54 to the destination of the blocks plundered from another building, similar to the one found on the base of one of the statues of Dacians re-used in the Arch of Constantine next to the Amphitheatrum Flavium, with the text: ‘ad arcu(m)’. Based on this evidence, Pensabene shrewdly deduces the existence of ‘state’ warehouses that would have contained building materials from structures damaged by catastrophes or which had been refurbished for different reasons, with the aim of re-using them in subsequent projects.Footnote 55

B-5. Interior of the north-west pillar, in the staircase leading to the attic, at the start of the second ramp, on a roof slab. Sheet or block of Proconnesian marble with roughly carved 15 cm high letters, very similar to B-4 (Fig. 13): ARC(I). Once again the inscription is in a position that is inaccessible to the general public, reinforcing the interpretation that it marks the destination for a block from the warehouse containing the spolia, and not a fortuitous piece of graffiti. This means that this warehouse would have contained blocks of both travertine and marble.

FIG. 13. New inscription B-5 documented in our architectural analysis inside the arch, north-west pillar.

B-6. During the renovation of the church of San Giorgio al Velabro at the start of the last century, the architect Antonio Muñoz found a number of pieces from the same marble panel, decorated with high-medieval bas-reliefs on one side, which had been intentionally cut at a later date in order to re-use the sections as steps for a staircase on the left side of the altar (‘gradibus scalarum a cornu Evangelii’). The back of these sections contained a monumental Roman inscription, already included in CIL VI as numbers 30364, 5–7 and 4, but which could only be properly assembled after re-composing the decoration on the reverse (Fig. 14 a and b).Footnote 56 In the 1990s, two of the fragments were found embedded in the back wall of the left-hand nave of the church with their inscribed side hidden from view, while the rest were stored in a small lapidary next to the church, where they were examined by Pensabene and Panella.Footnote 57 We have not been able to access these sections or examine them, and so our analysis is based on the description provided by these researchers and ex imaginibus. The reason for including this titulus in the catalogue is because, in 1980, F. Coarelli suggested that it could correspond to the original dedication from the nearby arch, and date from the period of Constantius II. Pensabene and Panella shared this view, although they tended towards a slightly earlier chronology, dating it to the time of Constantine (around a.d. 324).

FIG. 14. Monumental Roman inscription B-6 conserved in the church of San Giorgio al Velabro. (Photo library of the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum)

The panel that has been reconstructed from the five fragments is 122 cm high by 100 cm wide, with a thickness of between 16 and 17 cm. The inscription originally had at least one extra line on the top, which would have contained the name of Augustus, mentioned in the first line that is still preserved. The letters are 15 cm high in line 1, 14 cm high in lines 2–4, and 12 cm high in lines 5–7. The text reads:

- - - - - -

[---] AVG • MAXI[---]

[---]RRAE LIBER[---]

[---]TIS SVPERB[---]

[---]ORIQVE ET L[---]

[---]VM MAG[---]

[---]CEREN+ CO[---]

[---]SISSE HABENIS[---]

- - - - - -

Reading notes:

-

Line 1: without a point in Pensabene and Panella 1994–95, p. 29.

-

Line 2: BRAE LIBER in CIL VI, 30364, 5–6. The likely reconstruction would be: [--- totius orbis te]rrae liber[atori ---].

-

Line 3: without any interpunctuation on the stone, which is preserved.

-

Line 4: CRI QUE ET L in CIL VI, 30364, 6–7. More likely: [--- extinct?]orique et l[---].

-

Line 5: without any interpunctuation on the stone, which is preserved.

-

Line 6: CERENICO in CIL VI, 30364, 4 and in Pensabene and Panella 1994–95. In the photo we can read: [---]CERENT CO[---], the third person plural of a past imperfect subjunctive.

-

Line 7: without any interpunctuation on the stone; possibly the perfect infinitive [---]sisse habenis[---]; or otherwise the reflexive expression: [---effu?]sis se habenis[---] in scriptura continua.

The majority of researchers agree that because of the monumental, undoubtedly imperial nature of the inscription, and the fact that it was re-used in the neighbouring church of San Giorgio al Velabro from at least the ninth century, it must have formed part of one of the dedicationsFootnote 58 from the Arch of Janus that were originally located in the attic. An analysis of the formal structure of the titulus, as well as specific aspects of its text, now makes it possible for us to restore it. The text would have begun with the onomastics of the emperor, in larger sized letters, in a now-vanished first line; a nomenclature that ended with the abbreviation Aug. from line 1. Between this and line 4 are the royal epithets of the emperor in the dative, joined by numerous copulative conjunctions (---orique et l--- in line 4). After this line the text size decreases and a new subject appears in the plural form, in the narration of an event or gesture (---cerent Co--- / ---sisse habenis---), which would have continued in detail over several lower lines that have now vanished. The commissioning body — very probably the Senate and People of Rome — would have appeared at the start or end of the inscription.

We can therefore start out from the heuristic premise that the text must refer to Constantius II, due to the chronology of the arch,Footnote 59 and that it is possible to propose a reconstruction, taking into consideration the onomastics of this emperor.Footnote 60 In the epigraphic documentation he appears with a number of variations, which include: Domino Nostro Flavio Iulio Constantio P(io) F(elici) with thirty-five characters, or otherwise Imp(eratori) Domino Nostro Fl(avio) Iul(io) Constantio P(io) F(elici) with thirty-two; or with the same number of letters, but changing the abbreviations: Imp(eratori) Caes(ari) D(omino) N(ostro) Flavio Iulio Constantio P(io) F(elici). Taking into account this number of characters per line, the restoration we would propose — with the necessary caution — would be (Fig. 15):

[Senatus Populusque Romanus?]

[D(omino) N(ostro) Flavio Iulio Constantio Pio Felici]

[victori semper] Aug(usto) maxi[mo triumfatori]

[totius orbis te]rrae liber[atori urbis ac]

[fundatori quie]tis superb[i tyranni fact]

[ionis extinct]orique et l[ibertatis P(opuli) R(omani) vin]

[dici in hostes qui c]um mag[na crudelitate?]

[saevos? interfi]cerent Co[nstantem Aug(usti)]

[fratrem et effu?]sis se habenis [- - -]

- - - - - -

To Our Lord Flavius Julius Constantius the merciful, joyous, victorious and ever majestic, greatest victor of the whole sphere of the earth, liberator of the city and restorer of peace, as well as the disposer of the faction of the tyrant sovereign and avenger of the liberty of the Roman people against the enemies who savagely murdered with great cruelty the brother of the August [i.e. Constantius], Constans, and giving themselves free rein …

FIG. 15. Proposed reconstruction of the dedicatory inscription of the arch (B-6). (Illustration by L. Fernández under the supervision of A. Ventura)

Comments on the reconstruction:

We need to start by noting that we have not found any parallel epigraphic texts for this exact reconstruction of the imperial epithets, which were not used in this way for any emperor in the fourth century a.d. However, the epithets do appear separately applied solely to Constantius and in a particular historical setting: the period between the death of the usurper Magnentius in a.d. 353 and Constantius’ adventus to Rome for the triumphal celebrations in a.d. 357. This is a unique text of great value in propaganda terms, created for an exceptional monument.Footnote 61 Constantius is acclaimed as maximus triumphator in two statue pedestals erected in Rome by the praefectus Urbi Flavius Leontius,Footnote 62 in a.d. 355–356, and on a milestone in Hispania Citerior.Footnote 63 Apart from him, this eulogy was only used for Constantine I at the end of his reign, Constantine II and Julian,Footnote 64 the emperors who came immediately before or after him. The expression totius orbis terrae is more significant; thanks to Ammianus Marcellinus,Footnote 65 we know this was something that greatly pleased Constantius and it appears, in different versions, on the inscription of the Lateran ObeliskFootnote 66 erected at his initiative in the Circus Maximus in a.d. 357–359 under the supervision of the praefectus Urbi II Memmius Vitrasius Orfitus, and on the three pedestals erected by the same prefect in the ComitiumFootnote 67 to commemorate the triumphant adventus of Constantius in a.d. 357. The following epithets, which have been reconstructed based on the available space and the letters conserved in lines 2 and 3, liberator Urbis and fundator quietis, are also significant, as they are only known applied to Constantius’ father, Constantine the Great, in similar circumstances to the one in question: after the defeat of the ‘usurper’ Maxentius. No other emperor was referred to in this way. On the triumphal arch of Constantine next to the Amphitheatrum Flavium, these epithets do not form part of the imperial title, but instead are written on the pillars in the central span.Footnote 68 Here we detect a topos of the imperial propaganda of Constantius, which was aimed at showing him emulating and even exceeding his father's achievements.Footnote 69 We can find a similar ideological undercurrent in the expression superbi tyranni factionis extinctor, for which we once again find a precedent in Constantinian eulogies, which can then be compared to dedications to his sonFootnote 70 in the years a.d. 353–358, as we can once again see in the Lateran Obelisk or on the pedestals built by the praefectus Urbi Neratius Cerealis on the Via Sacra.

However, the key element that allows us to definitively attribute the inscription in question to Constantius II and associate it with the Arch of Janus and its ‘triumphant’ nature can be found in lines 4–7, which we believe refer to the revenge of the emperor against the murderers of his brother Constans, led by Magnentius.Footnote 71 Once again we do not have any exact parallels for this proposed reconstruction, as unique as the inscription itself. And yet this fits in with the ideological and propagandistic context we have described, and has similarities with other literary documents relating to the same emperor.Footnote 72 Also, our hypothetical reconstruction of the inscription includes in these final lines the main rhetorical adjectives that were normally used by Roman historiographers for describing an archetypal tyrant: superbia, crudelitas, saevitia, vis and libido. Footnote 73

In conclusion, we believe that the inscription is a eulogy to Constantius II which probably refers to his victoryFootnote 74 over the usurper Magnentius, and which therefore could only have been created in the years between the latter's death in a.d. 353 and the celebration of the imperial anniversaryFootnote 75 of Constantius in the spring of a.d. 357. The Arch of Janus, in accordance with the tradition of previously existing triumphal arches in Rome, would have been inaugurated during the only visit this emperor made to the Urbs between 28 April and 29 May in the year a.d. 357. The attribution of the titulus to the quadrifrons arch, apart from being very likely due to its topographic proximity, is further reinforced if we consider the size of the complete marble plaque that would have been necessary to contain a text as lengthy as the one that we have reconstructed, albeit partially. This would have occupied a space of approximately 2.5 by 4.5 metres, with letters between 15 and 12 cm tall, which, duly rubricated, would have been perfectly visible from the ground, at a height of more than 20 metres on the attic of the arch (Fig. 16).Footnote 76

FIG. 16. Proposed location on the arch of the dedicatory inscription B-6. (Illustration by L. Fernández under the supervision of A. Ventura)

The only remaining question is who commissioned the monument, and who ultimately supervised the inscription and its text. Based on its similarity with other urban triumphal arches, it must have been dedicated by the Senate and the People of Rome. But during the fourth century, it was the urban prefects acting on their behalf who were solely and finally responsible for public buildings in Rome.Footnote 77 Therefore we propose that the commissioner of the Arch of Janus was the praefectus Urbi, Memmius Vitrasius Orfitus.Footnote 78 This pagan, high-ranking aristocrat,Footnote 79 a trusted member of the court married to Constanza, a distant relative of the emperor, held the post of urban prefect on two nearly consecutive occasions in a quite exceptional manner:Footnote 80 the first between December a.d. 353 and the summer of a.d. 356, and the second between January a.d. 357 and the spring of a.d. 359. During his first prefecture, after Magnentius had committed suicide, he would have started work on the Arch of Janus in preparation for the expected triumphal adventus of the emperor. During his second prefecture he would have had the opportunity to inaugurate the monument in the presence of the emperor himself in the spring of a.d. 357, at the same time as he erected in his honour the three statues in the Comitium. Then, a few months after Constantius left and on his orders, he would have supervised the work to build the Lateran Obelisk in the Circus Maximus.Footnote 81

C-7. North-west pillar, west side, niche on the second level to the far left (forming the corner). On the block of Proconnesian marble that forms the shell semi-vault of the niche, over the archivolt on the right-hand side, with letters around 5 cm high. This is a graffito in Latin, not Greek, as it contains a letter R. This cannot be an inscription that existed prior to the construction of the arch (in a.d. 357) because of its palaeography, as it consists of uncial letters typical of the sixth to eighth centuries (Fig. 17). This is especially clear in the letters A, M, and above all in the E; the N is an evolved uncial.Footnote 82 The inscription reads:

TER MANSI (with nexus SI)

FIG. 17. Inscription C-7 at the end of the niches of the second level on the north-west-pillar, west face.

Ter is an adverb that means ‘three times’, but also ‘many times’ in a figurative sense, requiring a verb after it. Mansi is the first person perfect of the verb maneo, which means ‘to be, to remain’. So the translation would be ‘Many times have I been (up here)’. It is interesting to note the position of the graffito, as it is in the second row of niches, 13 m from the ground, where there are no footholds for its intrepid author. Also, the position of the inscription over the vault of the niche and on the surface that was covered by the original entablature of the arch, means that the entablature had already been dismantled before the inscription was made, or that it was being stripped at the time, and its author was able to reach this position using the scaffolding that had been erected for this purpose. For all of these reasons, we suggest that the inscription was made between the seventh and eighth centuries by one of the workmen who were stripping the sculptural decoration and marble elements from the sections superimposed over the arch, possibly for re-use in the construction or reconstruction of the nearby church of San Giorgio al Velabro.Footnote 83

C-8. North-east pillar, south face, central section of the podium, block on far right corner, 1.8 m from the ground (Fig. 18 a). Panel 25 cm high by 75 cm wide. Graffito in Greek, containing a long line with a cursus that rises slightly to the right with letters 2–3 cm high which are difficult to read at the end due to erosion, beneath which is a larger, centred letter π (6 cm high) (Fig. 18 b). Our approximate interpretation would be:

κωNςταNτιNως +εδεκ[---]

π

FIG. 18. (a) Inscription C-8 in Greek on the bottom of the north-east pillar, south face. (b) Detail of inscription C-8.

For R. Lanciani, this graffito, for which he does not provide any kind of identification, graphic documentation or details of its precise position, was a record of the visit by the Byzantine emperor Constantine II Pogonatus (a.d. 630–668) to Rome in 667 (sic), during his campaigns against the Lombards, the last ceremony to mark an imperial adventus in the Urbs, organized by Pope Vitalianus. He associated this inscription with another similar one on the Colonna Traiana, considering that both texts would have been made by members of the imperial entourage during the monarch's ‘tourist visit’ of the main monuments in the old Western capital.Footnote 84 During this visit, the emperor also ransacked a number of buildings to obtain metals, the most significant of which was the Pantheon, where he removed its roof of gilded bronze tiles.Footnote 85 In fact, the emperor's stay, which only lasted twelve days, took place between 5 and 17 July a.d. 663. Baptised with the name Herakleios/Heraclius, he is referred to on coins as Konstantinos/Constantinus with the nickname of Pogonatos due to his beard. Constans (κώνστας β') is a common diminutive used to refer to the same emperor, which has now been passed down into historiography.Footnote 86

In order to offer an initial interpretation of this complicated graffito, documented here for the first time, we believe it is necessary to compare it with the one on Trajan's Column, with which it is associated historiographically. This was published by J. M. Sansterre,Footnote 87 based on a scheda provided by Professor Testini. It is located at the top of the column, inside its inner marble cylinder, in front of the door that opens out onto the external balustrade. It consists of a prayer in Greek using a Byzantine formula, dedicated to an emperor named Constantine:

+ COCON (sic) K(υρι)E TON BACIΛEA

IMON (sic) KONCTANTINONFootnote 88

This immediately casts doubt on the similarity between the two texts, both in terms of their palaeography and their content, beyond the fact that they include the name Constantinos. In the case of the Arch of Janus, where the lower case omega letter is used, the imperial epithet basileus does not appear anywhere, even in its abbreviated form. Neither can it be insinuated from the more deteriorated final part, where the few letters that are legible do not correspond with other epithets or aliases of the Byzantine emperor Constans II Pogonatus.Footnote 89 The specific chronology, content and intention of this inscription therefore remain an open question. This is especially so if we consider that most of the Greek-speaking population of Rome settled in the area around the arch from the eighth century onwards, regrouped in an association known as the schola graecorum, where monks of Greek origin carried out beneficial and charity work co-ordinated by the diaconia of Santa Maria in Cosmedin, San Giorgio al Velabro and Santa Maria Antiqua, which surround the Arch.Footnote 90 If the graffito actually corresponded to the imperial visit in a.d. 663, then perhaps this was the moment when the statues that presumably decorated the niches and attic of the monument were plundered.Footnote 91

VI CONCLUSIONS

The architectural analysis of the Arch of Janus clearly reveals the complexity of its construction and a number of unique aspects that help in understanding the development of building techniques in the late imperial period. This complexity can be seen in the use of technical resources that are typical of monumental architecture, such as the use of opus caementicium in the foundations of the arch and its inner structure, associated with the first use of a technique that would become the most popular choice at this time: the re-use of construction materials. This characterizes the unique appearance of the Arch of Janus and opens up a series of questions about the operational praxis of this technique, the result of a well-known economic and political crisis that reduced imperial commitments to public architecture to a minimum. Characterized by an absence of funding for public works in the forums and monumental areas of the city of Rome, this situation resulted in the development of the spolia technique, with its own craftsmen and professional figures dedicated to the plundering and re-use of prestige materials in new structures.Footnote 92

As a result of our analysis, we have been able to define for the first time the stages of use and transformation of a building that indicate a series of historical events that are very evident on the external surfaces of the monument. As regards the spolia technique, we have been able to further our knowledge about specific aspects which we have indicated on the plans of the elevations, with references to the architectural elements that were re-used.

As regards the chronology of the building, substantial new elements are provided for consideration, together with a proposal for a more solidly argued dating from the period of Constantius II, based on the epigraphic analysis. The Arch of Janus or Arcus Divi Constantini was built as a homage by the Senate and People of Rome to the emperor, with its former name from the Cataloghi Regionari probably a result of sharing its dedication with his father, Divo Constantino, and the presence of numerous statues of the latter decorating its niches. The monument, clearly triumphal in nature because of its location, would have been commissioned after the death of the usurper Magnentius at the end of a.d. 353 or early 354, and was inaugurated to commemorate the adventus of Constantius II to Rome in the spring of a.d. 357 and the celebration of his imperial anniversary. The person who was ultimately in charge of the construction work and dedication would have been the praefectus Urbi Memmius Vitrasius Orfitus, during his two prefectures in a.d. 353–356 and a.d. 357–359, assisted by the curator statuarum Publilius Caeionius Iulianus who was responsible for the iconographic decorations. The monument served as propaganda to associate the emperor Constantius II with his father Constantinus, both of whom had triumphed over tyrannical usurpers and were sole rulers of a unified empire.