In memoriam A.C.

I THE AUGUSTAN PALATINE

It was probably in December 43 b.c. that the twenty-year-old Triumvir ‘Octavius Caesar’ acquired his house on the Palatine, a comparatively modest one by the standards of the time.Footnote 1 When adjacent properties were then bought up by agents acting on his behalf, it was not to provide more private space but to create the site for a great public building project, announced in 36 b.c. and completed in 28: a magnificent new temple of Apollo in solid marble, and grand porticos around it.Footnote 2 With temple and house in close proximity, and evidently a new piazza as well,Footnote 3 Rome now had a specifically Augustan urban focus.

It is a historical site of great importance, but thanks to the devastating fire of a.d. 64 and the vast ruins of the post-Neronian palace complex that came to dominate the hill, practically nothing of the Augustan Palatine is visible today. All that remains of the Apollo temple is most of the concrete core of the podium it stood on, and the house on display to the public as the ‘Casa di Augusto’ was never in fact completed, but incorporated into the foundations of the artificial platform on which the temple and porticos were built. Archaeologists have made confident attempts to reconstruct the Augustan complex, but the arguments they are based on are inadequate.Footnote 4

One reason for that is the assumption that the Apollo temple faced south-west, accepted as an unexamined axiom ever since Pietro Rosa excavated the site in 1865. The only evidence for it is a row of four holes in the concrete, two square and two rectangular, towards the south-west end of the podium, which are interpreted as the footings of six columns, a hexastyle south-west-facing pronaos.Footnote 5 In 2014, Amanda Claridge challenged that inference: having established from surviving fragments the colossal size of the temple's Corinthian order, she pointed out that the hypothesis of six such frontal columns is incompatible with Vitruvius’ description of the temple as ‘diastyle’.Footnote 6 She presented instead a forceful argument in favour of the opposite orientation of the temple, facing north-east.Footnote 7 That was accepted in my own historical analysis of the topography of the Palatine, but so far archaeological opinion remains unconvinced.Footnote 8

One part of Claridge's argument concerns the so-called ‘house of Livia’, excavated by Rosa in 1869 and famous for its wall-paintings.Footnote 9 We know from a contemporary text that the frontal columns of the Apollo temple stood ‘high on lofty steps’;Footnote 10 and we know from the surviving remains that if the temple did face north-east, that long flight of steps would come improbably close to the southern corner of the ‘house of Livia’. According to Claridge, however, the house was not there when the temple was built.

Her argument, which has hardly been noticed in the subsequent literature, deserves to be taken seriously:Footnote 11

[T]here is no evidence that the two buildings ever co-existed in space or time. Carettoni's excavations in and around the house in 1949-53 not only dated its original construction to 100–80 b.c. but also indicated that its drains went out of operation in the 40s or 30s b.c.,Footnote 12 that is, as the temple was being built. The floor level of the house lies over 6 metres lower in the ground (41 masl) and none of its walls is standing higher than about 46.50 masl, i.e., a metre below the temple level. The walling confusingly visible above ground today is all modern, for the safety of pedestrians, or supporting the roofing that protects the paintings in the rooms at the NW end. The excellent state of preservation of the latter is best explained by their interment very soon after they were made.Footnote 13 The subterranean passage leading from the direction of the Flavian palace to the SE end of the house only connected with the foot of a stair up to the Augustan level, not with the house as such. We should mentally eliminate the ‘House of Livia’ from the picture.

In The House of Augustus (2019), I took this as proof that the ‘house of Livia’ was demolished down to ground level in 36 b.c. (when the Apollo temple project was begun), and its basement paved over to create space for a piazza north of the temple.Footnote 14 However, that reconstruction has not found favour in recent major publications on the Augustan Palatine.Footnote 15

The aim of this article is to test the plausibility of the Claridge–Wiseman model by examining the evidence for the ‘subterranean passage’ and its two branches to north and south (respectively ‘passages 1, 2 and 3’ in what follows).Footnote 16 Can the surviving remains provide any useful information on their date and purpose?

II THE PASSAGES

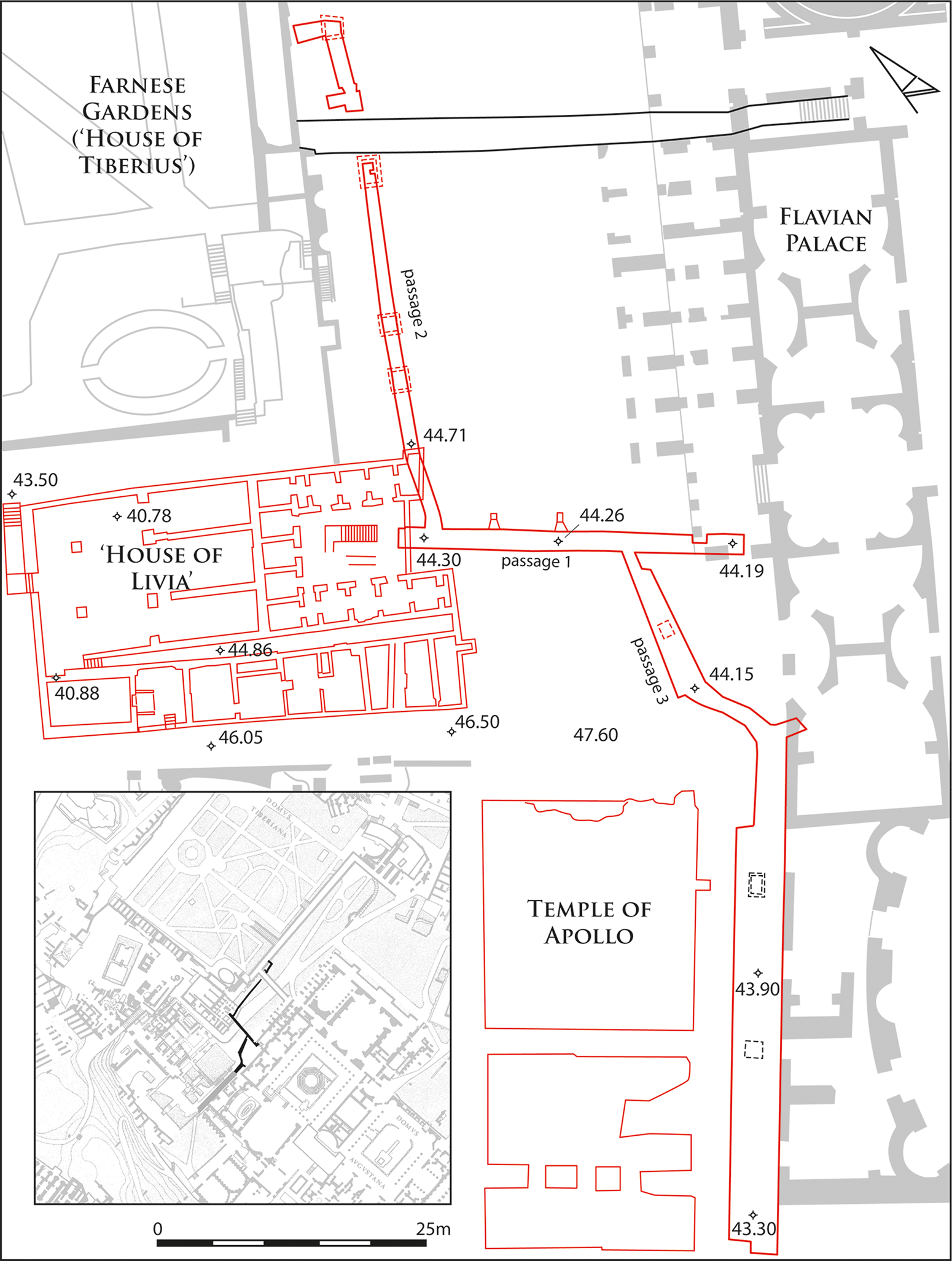

The essential data are presented in Fig. 1.Footnote 17

FIG. 1. Plan of the underground passages. Spot heights are in metres above sea level; pre-Neronian structures are in red. (Drawing: Seán Goddard)

Passage 1 was a regular vaulted structure about two metres wide, running directly south-eastwards from the basement area of the ‘house of Livia’ to a point just inside the Flavian palace; its floor level was about 44.20 masl.Footnote 18 At two points oblique shafts admitted light from above, where the ‘Augustan’ paving of the Palatine summit was at about 47.60 masl.Footnote 19 At the south-eastern end it was blocked by the foundations of the palace,Footnote 20 and immediately beyond that point the passage in its present form ends in a roofless space,Footnote 21 perhaps the site of the original staircase up to ground level. (At right angles to the left a later corridor, wider and of a different architectural form,Footnote 22 leads off north-eastward through the basement of the Flavian palace entrance porch.)

Passage 2 branched off northwards immediately after the entrance to passage 1 from the ‘house of Livia’. It is narrower than passage 1,Footnote 23 less direct in its course, and with light sources directly above; its direction suggests that it provided access to and from the ‘house of Tiberius’ complex.

Passage 3 began from the extensive underground space, 4.30 m wide and over 40 m long, that flanked the Apollo temple on the south-east side;Footnote 24 the end wall of this structure was evidently pierced to provide an entrance to the passage. Just a few metres in, the passage divided: the right-hand branch is lost (destroyed by the foundations of the Flavian palace),Footnote 25 but the left-hand branch survives as an irregular passage leading north. After about 8 m it enters what looks like another pre-existing feature (floor level 44.15 masl), a near-rectangular space roughly 12 m metres long by 2 to 3 m wide, with a central ceiling aperture as a light source. From the north end of it a short link leads into passage 1.Footnote 26

These details suggest that the three passages were not designed as a single homogeneous project. The simplest explanation is that passage 1 was constructed first and that at some later date (or dates) the other passages extended it to north and south. For passage 2 there is a fixed terminus ante quem: it was cut through and blocked by the spacious underground corridor that linked the two ‘wings’ of the huge palace complex laid out by Nero's architects after the great fire of a.d. 64.Footnote 27

Our passage 1 may be analogous to the later corridor, though on a smaller scale. In this area of the Palatine, space for a major planning project had previously been achieved in 36 b.c., when ‘Imperator Caesar’ demolished the houses that his agents had been buying up for him and thus made room for the Apollo temple and its lavish porticos.Footnote 28 To judge by its regular layout, passage 1 could date from that very year, part of the infrastructure created in the initial stages of the project. Passage 3, on the other hand, gives the impression of a later improvisation, exploiting with ad hoc linking tunnels whatever pre-existing underground space happened to be available beneath an Augustan complex that was already in place.

The south-eastern terminus of passage 1 was within the layout of the Flavian palace, and the Flavian palace was called domus August(i)ana.Footnote 29 It is an obvious possibility that that was the site of Augustus’ house.Footnote 30 For the last sixty years, however, orthodox opinion has identified Augustus’ house as the one excavated by Gianfilippo Carettoni immediately north-west of the Apollo temple at a level 9 m below it.Footnote 31 That orthodoxy has survived the demonstration in 2006 that the house Carettoni excavated was abandoned before completion and incorporated into the foundations of the platform for the Apollo temple and its porticos; the ‘Carettoni house’ is now reconceptualised as ‘the house of Octavian’ or ‘the interrupted house’, with the true ‘house of Augustus’ a conjectural later construction at a higher level as part of the temple project itself.Footnote 32

Fortunately the north-west end of passage 1 survives, and thanks to Patrizio Pensabene's detailed up-to-date analysis of the ‘house of Livia’,Footnote 33 the complex archaeological data are now much easier to understand.

III THE ‘HOUSE OF LIVIA’

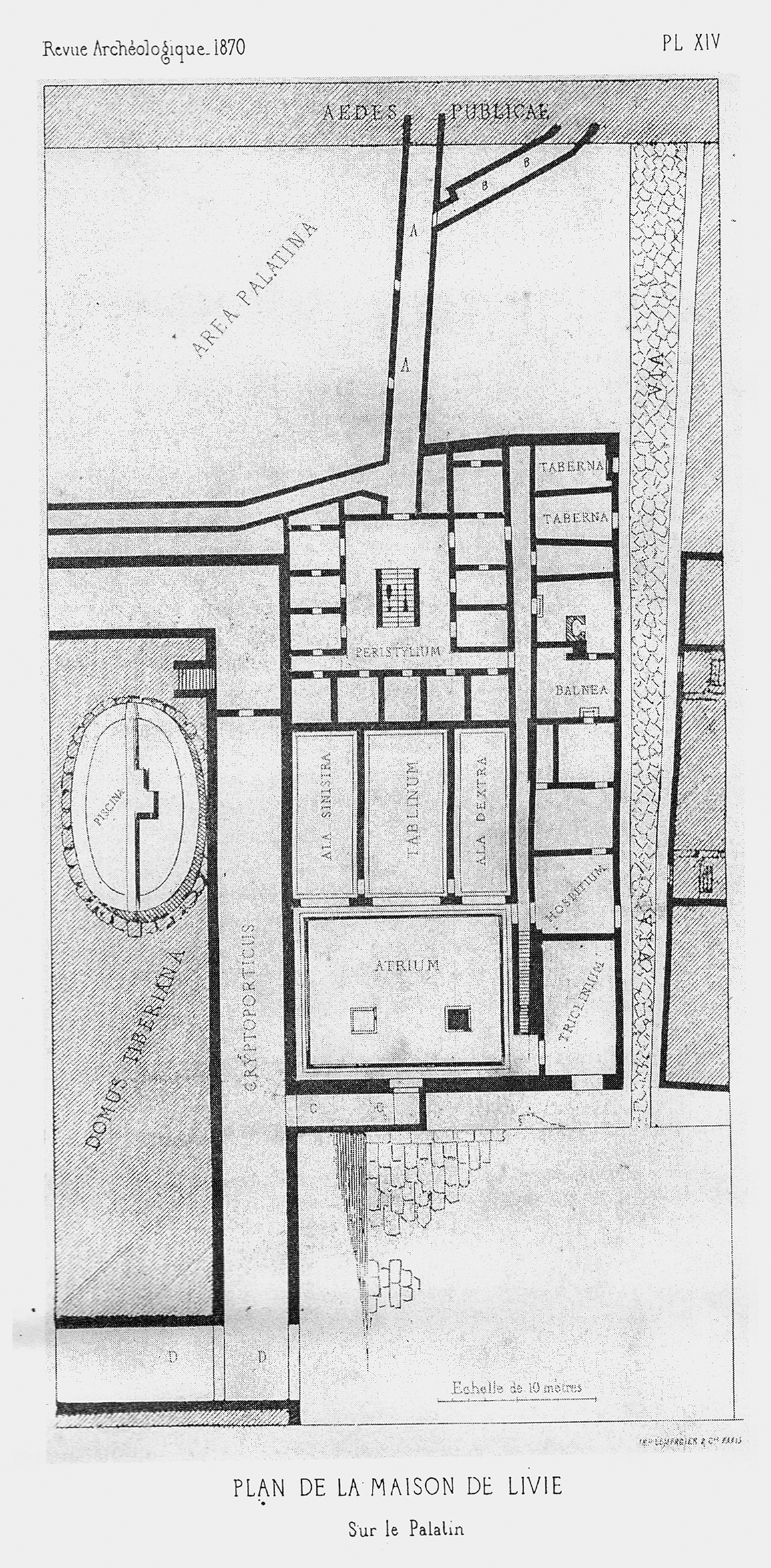

The house was excavated by Rosa in the early months of 1869. He was working for the French emperor Napoléon III,Footnote 34 and reporting regularly to Léon Renier, head of epigraphy and Roman antiquities at the Collège de France.Footnote 35 It may have been with his report of 10 April that year that he sent the first schematic plan of the house, which was printed in Paris and published by Renier in the Revue archéologique (Fig. 2).Footnote 36 The engraver got one important detail wrong: the two-flight staircase in the middle of the ‘Peristylium’ was aligned not with the surrounding rooms but with the underground passage that entered the courtyard on the south-east side (‘A–A’, our passage 1).Footnote 37 Nevertheless, this plan is the earliest record of what Rosa found, and the names he chose for the rooms have influenced discussion ever since.

FIG. 2. Rosa's original plan of the ‘house of Livia’. North is to the bottom left. (Renier Reference Renier1870: pl. XIV)

The plan represents the basement or semi-basement rooms of a house now known to have been built about 100 b.c.Footnote 38 The common floor level of the ‘Atrium’, ‘Tablinum’, ‘Ala sinistra’ and ‘Ala dextra’ is just under 41 masl,Footnote 39 5 m below the level of the street outside;Footnote 40 the ‘Atrium’ and ‘Triclinium’ were presumably lit by windows high in the north-west wall. To the south-east, the construction of the ‘Peristylium’ began at a similar level (just below 40 masl), but it took the form of two storeys of vaulted ‘rooms’ around a courtyard, the lower of which may not have been accessible.Footnote 41 The upper rooms had a floor level of just under 44 masl,Footnote 42 with access at the western corner to a long corridor that led back to a staircase down to the level of the ‘Triclinium’.Footnote 43 The row of rooms on the other side of the corridor was also at about 44 masl, 1 to 2 m below the level of the street outside.Footnote 44

Access to these low levels was by a sloping corridor at the north corner of the house leading directly into the ‘Atrium’.Footnote 45 Did Rosa think that was the main entrance to the house? Certainly the large rooms at this level were appropriately grand and beautifully decorated; but the main access to the reception areas is much more likely to have been at or above street level. Three different reconstructions have been offered of the lost upper storey of the house.

The first assumes that it duplicated what lay below: Rosa's ‘Atrium’ supported an atrium, Rosa's ‘Peristylium’ supported a peristyle with a pool in the centre, and the main entrance porch was on the north-west side above the sloping corridor.Footnote 46 That hypothesis has the virtue of simplicity, offering something like the conventional ‘atrium-peristyle’ layout best attested on the Severan marble plan.Footnote 47

The second reconstruction also assumes an entrance at a higher level on the north-west side,Footnote 48 but takes more account of the architecture of Rosa's ‘Peristylium’. That area was structured round a series of twelve substantial travertine pillars embedded into the dividing walls of the rooms,Footnote 49 an armature that seems designed to support something heavier than a mere peristyle portico. Gilles Sauron and Valentina Torrisi have recently proposed that the upper storey at this point consisted of an elaborate oecus Corinthius in the form of a private theatre.Footnote 50 Other such conjectures are possible in the absence of any surviving upper-level remains.

According to the third reconstruction, what Rosa's ‘Peristylium’ supported was the atrium itself with its impluuium; the surviving rooms below it were for storage or slave quarters. The main entrance to the house is assumed to have been at the south-east end, and Rosa's ‘Atrium’, ‘Tablinum’ and ‘Alae’ are reinterpreted as a cortile or ‘sunken dining-court’.Footnote 51

In assessing these rival hypotheses, it is important to remember that the level of the lost upper storey of the ‘house of Livia’ was about 47 masl,Footnote 52 and that the north-west end of the house was only 10 m distant from the old temple of Victoria, which was constructed at a level of about 40 masl.Footnote 53 That downward slope of the terrain makes it hard to visualise an entrance to the upper level of the house on that side, as assumed in the first and second reconstructions; the only measured section-drawing that has been offered has to postulate a ramp and a steep staircase to reach the entrance porch from street level.Footnote 54 The third reconstruction avoids that objection, since a main entrance at the south-east end would be at much the same height as the summit level of the hill.

The point at issue in this still unresolved debate is the design of the house as it was originally built about 100 b.c. What happened to it after 36 b.c. is a separate question, equally unresolved.

IV THE HOUSE OF AUGUSTUS?

As noted in Section II above, the house discovered below the north-west side of the Apollo temple was identified by Carettoni as that of Augustus himself,Footnote 55 and then reinterpreted as ‘the house of Octavian’ or ‘the interrupted house’ when it became clear that it had been destroyed to create the platform for the temple and its porticos.Footnote 56 As a corollary of that hypothesis, it is widely believed that the actual house of Augustus was at a higher level on the same site, extending northwards to incorporate the ‘house of Livia’.Footnote 57

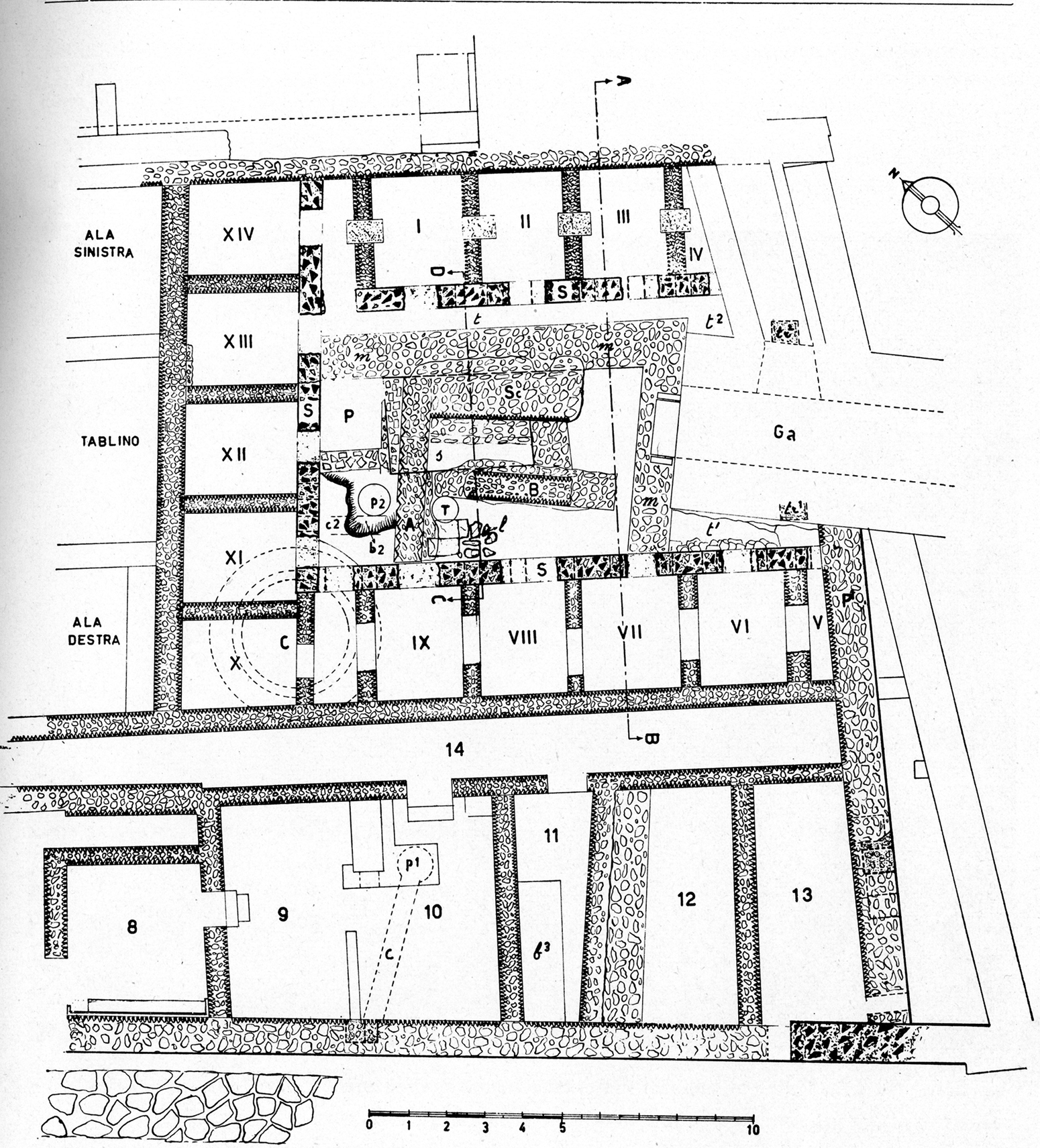

Those who disagree point to the absence of positive evidence, whether textual or archaeological.Footnote 58 As Claridge insists, nothing of the ‘house of Livia’ survives above c. 46.50 masl, which is a metre below the Augustan ground level.Footnote 59 Everything depends on the interpretation of the basement area at the south-east end (Rosa's ‘Peristylium’), and in particular the point where our passage 1 begins. The essential information is provided by Carettoni's plan from 1957 (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3. The south-eastern area of the ‘house of Livia’. (Carettoni Reference Carettoni1957: 73, fig. 1)

The tunnel was at the same level as the basement of the house (about 44 masl),Footnote 60 but joining the two was not just a matter of breaking through a wall. It is clear that the creation of the entrance to passage 1 involved a major reconstruction (Fig. 4). At basement level, three of the rooms around the ‘courtyard’ were destroyed; necessarily, the floor above must have been rebuilt, possibly including the main entrance to the house.Footnote 61

FIG. 4. The entrance to passage 1, and to passage 2 on the left, from the ‘Peristylium’ area of the ‘house of Livia’. (Photo: Patrizio Pensabene 2021a: 260, fig. IV,25a)

The passage (Fig. 3 ‘Ga’) was aligned with a new stairwell (Fig. 3 ‘S’, ‘B’, ‘A’), the concrete core of which is a conspicuous surviving feature in the centre of the ‘courtyard’ (Fig. 3 ‘S’; Fig. 5). What sort of space did the stairs lead up to? It is hard to imagine an upper-level oecus Corinthius or atrium (the second and third reconstructions listed above) that featured a staircase in the middle of the floor. On the other hand, according to Claridge's hypothesis that the upper levels of the house no longer existed when the passage was created, it was simply ‘a stair up to the Augustan level’, with no further explanation.Footnote 62

FIG. 5. View from passage 1 into the basement area of the ‘house of Livia’; the concrete core of the staircase (Fig. 3 ‘S’) is visible in the middle of the ‘Peristylium’. (Photo: Patrizio Pensabene 2021a: 260, fig. IV,24)

The entrance to the passage was set into a concrete wall (Fig. 3 ‘m’; Fig. 4), with a wide block of travertine as the threshold.Footnote 63 Immediately to the left of the entrance the wall turned at an acute angle to run parallel to the north-east range of basement rooms; it seems to have continued into the grand suite of rooms at the north-west end of the house, in the form of a brick wall abutting one side of the ‘Tablinum’ and extending right across the full width of the ‘Atrium’.Footnote 64 Rosa regarded it as a late and ‘barbaric’ intrusion, and spent three weeks demolishing it.Footnote 65

Ever since 2002, when Clemens Krause first made the conjecture, it has been widely believed that this wall formed the north-east corner of the foundations of a large near-rectangular building erected on the combined sites of the ‘house of Livia’ and the house excavated by Carettoni.Footnote 66 Krause identifies the supposed building with the mysterious ‘temple of the Caesars’ attested in a.d. 68;Footnote 67 but if the wall and the passage are contemporary, as the remains seem to suggest, a hypothesis that identifies the former as the foundation-wall of a necessarily post-Augustan building does not seem very satisfactory.Footnote 68

Krause's argument is exploited differently by those who believe that the ‘house of Augustus’ extended on to this site.Footnote 69 According to Irene Iacopi, the supposed foundations were of the house of Augustus itself.Footnote 70 That suggestion was immediately taken up by Andrea Carandini and Daniela Bruno as one of the corner-stones of their ambitious reconstruction of Augustus’ supposed ‘palace-sanctuary’,Footnote 71 and throughout the subsequent evolution of that hypothetical complex the acute-angled wall next to the entrance to the underground passage has continued to define the shape of their ‘domus privata di Augusto’.Footnote 72

Their first model envisaged the effective destruction of the ‘house of Livia’, and the imposition on to the site of a new house with a totally different internal plan.Footnote 73 That was very soon revised,Footnote 74 and since 2010 successive plans have presented the supposed ‘domus privata’ as partly consisting of the ‘house of Livia’ itself, imagined with its entrance at the north-west end.Footnote 75 Since 2018 the same interior layout has even been adopted, in reverse, for a supposed ‘domus publica’ on the opposite side of the Apollo temple.Footnote 76 If ancient evidence really existed, as is claimed, for separate ‘private’ and ‘public’ houses of Augustus, passage 1 would be immediately comprehensible as a private communication between them; but there is no such evidence.Footnote 77

It is hardly possible to reconcile these rival developments of Krause's idea,Footnote 78 and perhaps the idea itself should be queried. In the absence of any evidence at ground level, why must it be assumed that the wall (Fig. 3 ‘m’; Fig. 4) was the foundation of some grand building which has subsequently disappeared? It may have had a quite different purpose, as part of the infrastructure required by the extension of the ‘Augustan’ paving (at 47.60 masl) over ground that was sloping down to a much lower level.Footnote 79 Robust walls would be needed at the earliest stages of the project to contain the huge amounts of earth infill required and to stabilise the site before work could begin on building the Apollo temple and the portico that surrounded it.Footnote 80

V AN ALTERNATIVE SOLUTION

For the last thirty years the leading authorities on the archaeology of the Palatine have been Patrizio Pensabene and Andrea Carandini. Both scholars have recently published books that encapsulate their ideas about the Augustan Palatine project,Footnote 81 works very different from each other but taking the same fundamental beliefs for granted: first, that the Apollo temple faced south-west; second, that Augustus’ house was where Carettoni said it was; and third, that that house formed part of a palace. The first two of those axioms are disputed by Claridge, and I would dispute all three of them.Footnote 82

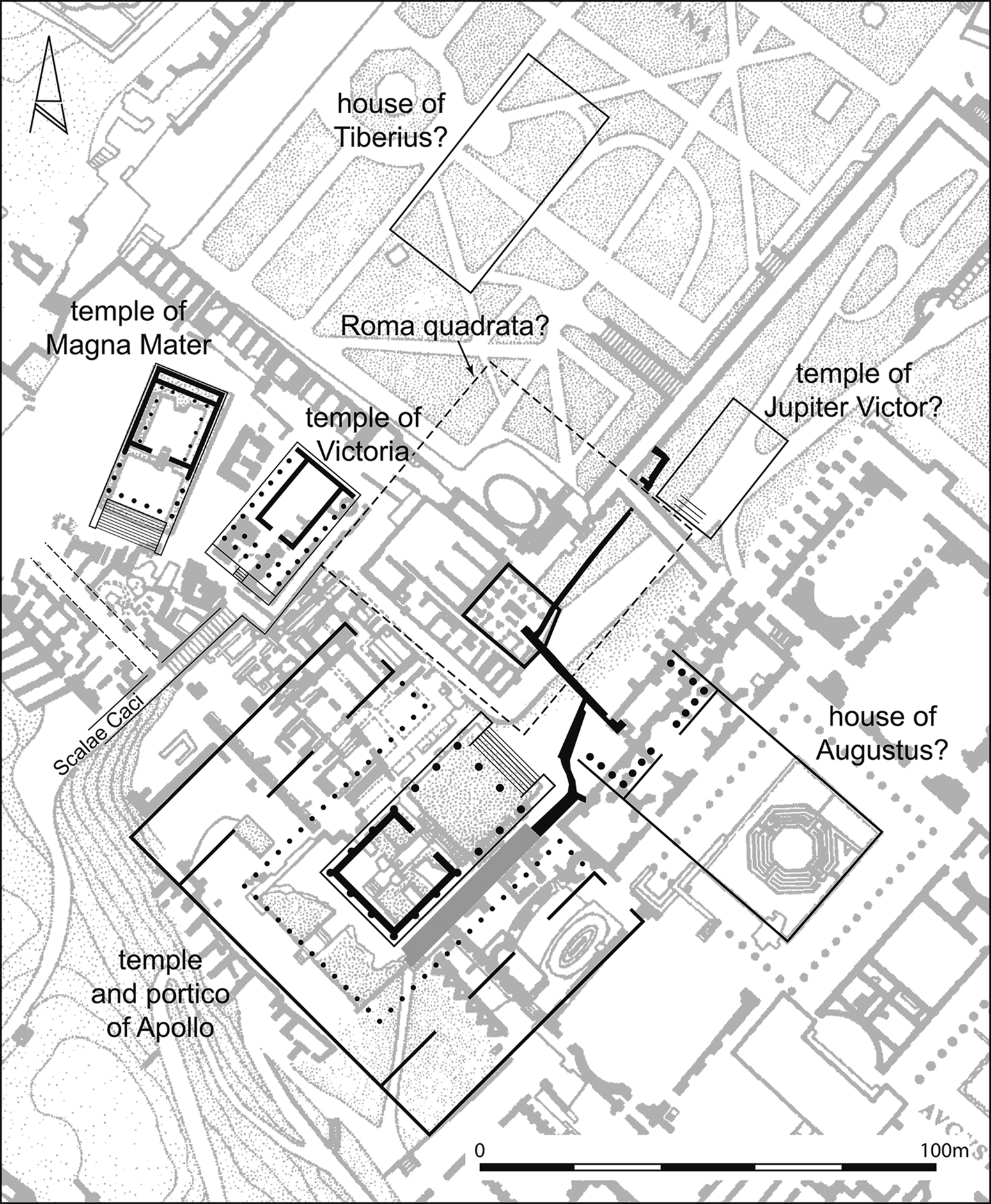

What would the Augustan Palatine have looked like if (a) the Apollo temple faced north-east, (b) the house of Augustus was on the site of the domus August(i)ana, and (c) the ‘house of Livia’ was demolished, with only the basement levels surviving? Fig. 6 is based on my own suggested reconstruction, highly speculative but I hope ‘good to think with’, which locates Augustus’ house on the assumption that the position of its forecourt and entrance corresponded to the forecourt and entrance of the Flavian palace.Footnote 83 Since passage 1 terminates below the porch of the Flavian palace, with one necessary adjustment this model accommodates the evidence surprisingly well.Footnote 84

FIG. 6. The plan of the passages superimposed on to a conjectural plan of the Augustan Palatine; the position of the Jupiter Victor temple and the configuration of the portico of the Apollo temple and the forecourt of Augustus’ house are purely exempli gratia. (Drawing: Seán Goddard, adapted from Wiseman Reference Wiseman2019: 142, fig. 67)

The elements of this area of the Augustan Palatine are listed in the Notitia, a fourth-century register of the fourteen regiones of the city, the nucleus of which evidently dates back to when the system of city-regions was first instituted in 8 or 7 b.c.Footnote 85 The list for the Palatine (regio X) includes the sequence ‘Houses of Augustus and Tiberius – augur's station – Palatine piazza – temple of Jupiter Victor’,Footnote 86 which suggests some significant myth-historical juxtapositions.Footnote 87

The Palatine piazza (area Palatina) was ‘where Rome was first founded’;Footnote 88 Rome was first founded ‘around the hut of Faustulus’, foster-father of Romulus and Remus;Footnote 89 the hut of Faustulus was ‘in the precinct of Jupiter’, presumably Jupiter Victor;Footnote 90 the augur's station (auguratorium) from which Romulus sought divine approval for the new foundation was a hut ‘in a clear space’ on the summit of the Palatine;Footnote 91 and Romulus’ ‘august augury’ was the reason why Imperator Caesar was given the name ‘Augustus’.Footnote 92

The position of the Jupiter Victor temple is unknown;Footnote 93 destroyed in the fire of a.d. 64, it may have been rebuilt on another site.Footnote 94 But the ‘houses of Augustus and Tiberius’, identified by the post-Neronian palaces that were named after them,Footnote 95 are enough to place all these interconnected toponyms in the area covered by Fig. 6. When the Notitia list was first drawn up in 8 or 7 b.c., Tiberius was not only Augustus’ son-in-law but also his acknowledged deputy, with independent proconsular imperium.Footnote 96 Both houses would now be significant features of the Palatine landscape.

The derivation of Augustus’ name is profoundly significant.Footnote 97 From the very start of his extraordinary career, he had modelled himself on Romulus the augur, one who followed the will of the gods. On 19 August 43 b.c., taking the auspices after his election as consul at the age of nineteen, the young Caesar was granted the same divine sign (twelve vultures) that Romulus had received.Footnote 98 Seven years later, victorious in two devastating civil wars, Imperator Caesar (as he now was) set about creating a grand new temple complex for the god whom the poets would call ‘augur Apollo’.Footnote 99

He was ‘Commander Caesar’, and a Roman imperator led his forces not only by command (imperio) but also by augury (auspicio).Footnote 100 In every Roman military camp or fortress, the broad assembly area next to the commander's quarters featured altars for sacrifice, an auguratorium for the commander to consult the will of the gods and a tribunal for the commander to address his men.Footnote 101 The same was true of the piazza created by Imperator Caesar in 36 b.c. on the site of the demolished houses of the defeated oligarchs.Footnote 102

On the Claridge–Wiseman hypothesis, the ‘house of Livia’ was one of those demolished properties. The surviving remains make it very likely that part of its basement area was exploited in order to create, via the underground passage 1 and the staircase to which it led,Footnote 103 a direct link between the house of the victorious imperator and a site in the new piazza in front of the Apollo temple. It is a reasonable guess that that site was the tribunal and/or auguratorium.

As Triumvir, Imperator Caesar had twelve lictors waiting outside his door to escort him when he appeared in public, but on occasions when the piazza was very crowded, direct access to the tribunal would avoid the invidious necessity of having the lictors force a way through.Footnote 104 Compare Appius Claudius, praetor in 57 b.c., who came up on to his tribunal through a trapdoor, like a stage character emerging from Hades;Footnote 105 how he got there is not clear from Cicero's satirical account (‘the Appian way’), but the very fact that he chose to do so may be significant.

Since Imperator Caesar was also an augur,Footnote 106 private access would be equally useful for the auguratorium. The augur's station was usually called a tabernaculum, and the normal procedure was for the augur to choose his vantage point (tabernaculum capere) and stay there overnight, rising at dawn to make his observations.Footnote 107 The underground passage 1 would enable this particular augur to sleep at home and still carry out his duty.

It is not clear from the extant remains (Fig. 3) whether the passage gave access only to the stair or to some of the basement rooms as well, which could have been used for storage. That may be relevant to a notoriously controversial passage in Festus:Footnote 108

‘Square Rome’ is the name of [a place] on the Palatine in front of the temple of Apollo. It is where those things have been stored which are customarily used for the sake of a good omen in founding a city. [It is so called] because it was originally defined[?] in stone in a square shape. Ennius refers to this place when he says ‘And […] to rule over square Rome’.

I suggested in 2019 that Roma quadrata was a marked-out space 240 feet square, representing the first plot (heredium or quadratus ager) of Romulus’ equally divided settlement.Footnote 109 Beginning at an unidentified ‘grove in the area Apollinis’, it ended at ‘the top of the scalae Caci, where the hut of Faustulus was’.Footnote 110 Since its conjectured position (Fig. 6) includes the basement of the ‘house of Livia’, it seems possible that ‘the things used for the sake of a good omen in founding a city’ could have been stored there in the surviving rooms. In 36 b.c. Imperator Caesar was much concerned with the founding of cities, as colonial settlements for the veterans of the civil wars.Footnote 111

Putting all these scraps of evidence together, the simplest explanation is that the new piazza featured a raised platform, roughly 18 m by 14 m in size and based on the walls and travertine pillars of Rosa's ‘Peristylium’ (Figs 2 and 3), with a newly built staircase down to the private passage to Commander Caesar's house. Obviously usable as a tribunal, such a platform would be large enough to accommodate the historic ‘hut of Faustulus’ that had stood in the precinct of Jupiter Victor, and high enough to provide the clear view to the east required of an auguratorium.Footnote 112

VI AFTER AUGUSTUS

Passage 2, the northern branch, was evidently a later development, added to provide the same privileged access from Tiberius’ house as well. The context of its construction may have been a.d. 4, when Tiberius was adopted as Augustus’ son and successor, or a.d. 14, when he became princeps himself. It is possible that passage 3 was made at the same time, extending his access also to the Senate chamber in the portico of the Apollo temple,Footnote 113 though that can only be speculation.

Augustus named Tiberius and Livia as his heirs, specifying that they should use his name.Footnote 114 Livia's new identity as Iulia Augusta, the result of a ‘testamentary adoption’ by her late husband,Footnote 115 happens to be attested at the very place where that name was most significant: on a lead water-pipe in the passage that linked the domus August(i)ana with the site (on this hypothesis) of the augustum augurium itself.Footnote 116

As the priestess in charge of the deified Augustus’ cult, Livia set up a shrine to him on the Palatine and instituted annual games in his honour.Footnote 117 It was at those games in January a.d. 41 that Gaius ‘Caligula’ was killed, and Josephus’ narrative of the event provides some important details. It begins as follows:Footnote 118

[The conspirators] decided that the best time to make the attempt was while the Palatine games were on. These shows are held in honour of the Caesar who first transferred power from the Republic to himself. There is a wooden hut just in front of the imperial residence, and the audience, besides the emperor, consists of the Roman nobility with their wives and children.

How the hut was relevant to the audience becomes clear later, in the only other passage where the hut is mentioned. As Josephus narrates it, Gaius began the proceedings with a sacrifice to Divus Augustus. Then,Footnote 119

after the sacrifice, Gaius turned to the show and took his seat, with the most prominent of his friends around him. The theatre was a wooden structure, put up each year in the following way. It had two doors, one leading into the open, one into a stoa for going in and out without disturbing those segregated inside, and within from the hut itself, which separated off another one by partitions as a retreat for competitors and performers of all kinds.

The meaning here is not obvious, and Josephus may not have fully understood what he read in his source text.Footnote 120 Nevertheless, it is clear that the hut was somehow part of the temporary theatre.

What did Josephus mean by στοά? The obvious translation is ‘portico’, and it could refer to the Ionic colonnade of the forecourt of Augustus’ house as portrayed on the ‘Sorrento base’.Footnote 121 But since the word could also be used in the sense of ‘gallery, communication trench, whether above ground or excavated’ (LSJ), it is possible that the contemporary author used by Josephus was referring to the underground passage 1. Although the normal Latin word for such a passage was crypta, in the late first century a.d. cryptoporticus was sometimes used as an equivalent,Footnote 122 and that could have influenced Josephus’ choice of a Greek translation.

Despite the unavoidable uncertainties, Josephus’ narrative fits very well with the idea of a raised platform (tribunal doubling as stage), and on it the ‘hut of Faustulus’ connected to passage 1 by a stair and used by performers for exits and entrances. That idea presupposes Claridge's hypothesis that the ‘house of Livia’ was demolished before the temple of Apollo was built, and that the temple faced north-east. It would be invalidated by the current archaeological consensus, that the temple faced south-west and the ‘house of Livia’ remained standing, redeveloped either as Augustus’ own house or as the aedes Caesarum (Section IV above).

VII CONCLUSION

A valid hypothesis is one that makes sense of all the available evidence. By that criterion Claridge's hypothesis, that ‘we should mentally eliminate the “House of Livia” from the picture’,Footnote 123 is indeed valid, and preferable to that of the current orthodoxy. Once we accept it, and focus on how the basement area of the house was exploited and reconstructed, the scattered and enigmatic evidence for the Augustan Palatine can fall into place at last.

My own tentative reconstruction depends on Claridge's hypothesis but is not a necessary consequence of it, and so must be assessed separately.Footnote 124 But it, too, is compatible with the evidence of the passages, as Fig. 6 shows, and it also helps to explain something that has caused much confusion in recent years, Ovid's extraordinary claim that Augustus shared his house with Vesta and Apollo.Footnote 125

When his calendar poem reached 28 April, the day when in 12 b.c. a shrine of Vesta was set up ‘in the house of Imperator Caesar Augustus, pontifex maximus’,Footnote 126 Ovid provided the necessary celebration:Footnote 127

Take the day, Vesta! Vesta has been received at her kinsman's threshold, as the just Fathers have decreed. Phoebus has one part, a second has gone to Vesta, he himself as the third occupies what is left from them. Stand, you Palatine laurels! May the house stand, wreathed with oak! One [house] holds three eternal gods.

‘At his threshold’ must mean ‘in his forecourt’,Footnote 128 as illustrated on the ‘Sorrento base’, where Augustus’ house-door and a round temple of Vesta are linked by an Ionic colonnade.Footnote 129 The scene on the relief shows that Vesta's shrine was at the south-west end of the forecourt, close to the Apollo temple in the reconstruction presented in Fig. 6. So if that reconstruction is anything like the reality, the Romans in the piazza could see three separate elements of the newly built environment — Apollo's temple, Vesta's shrine and Augustus’ door with the laurels and the oak-leaf crown — so close together that it was natural to think of them as a unit.

Looking that way, to the southern corner of the piazza, they saw Augustus’ house and the divinities who favoured him. Turning to look the other way (if our inference from the passages is justified), they saw his tribunal, and on it the ancient hut where Romulus and Remus had grown up and where the founder had sought the gods’ approval for his city by the ‘august augury’ that was now personified in Augustus himself.