Under the “free movement” rules of the European Union, EU workers have the right to freely work in any EU member state, as well as the right to full and equal access to that country’s welfare state. This has led to a situation where European Community rules and regulations have partly dissolved national state borders in social policy, and where EU enlargements expand the potential numbers of social policy claimants (Kvist Reference Kvist2004). Even though social policy de jure is a national prerogative, de facto it is not since EU states no longer can choose whom to give social rights to: the domain of potential welfare beneficiaries is decided by the uncontrollable influx of intra-EU immigrants.

Our study examines whether the combination of unrestricted intra-EU migration and equal access to national welfare states for EU workers is associated with welfare chauvinism – the idea that native citizens are unwilling to grant social rights to foreigners (Andersen and Bjørklund Reference Andersen and Bjørklund1990). Despite a growing literature on welfare chauvinism (e.g. Crepaz and Damron Reference Crepaz and Damron2008; Mewes and Mau Reference Mewes and Mau2012; Reeskens and Van Oorschot Reference Reeskens and Van Oorschot2012; Van der Waal et al. Reference Van Der Waal, De Koster and Van Oorschot2013) it is still not obvious what can best explain cross-national heterogeneity in welfare chauvinistic attitudes. Moreover, the effect of actual levels of immigration on welfare chauvinism has scarcely been examined, especially in terms of intra-EU migration, which is surprising given the mounting controversies spurred by this particular immigration.

Our study fits within the growing literature that examines how immigration affects social preferences (e.g. Luttmer Reference Luttmer2001; Alesina and Glaeser Reference Alesina and Glaeser2004; Eger Reference Eger2009; Mau and Burkhardt Reference Mau and Burkhardt2009). We contribute to and expand on the literature by focussing primarily on intra-EU immigration rather than on general immigration, and by concentrating on welfare chauvinistic attitudes.Footnote 1

Ensuring the right to social security when the right of freedom of movement is exercised has been a major concern for the EU. To achieve this, EU social security regulation protects EU citizens working and residing in any Member State from losing their social security rights (Regulations 883/2004 and 987/2009). EU labour immigrants are entitled to welfare benefits on equal terms with the natives.

Coupled with the free movement of workers in the EU, this right to equal benefits creates a tension: on the one hand we have the liberal ideal of free movement of people, and on the other hand we have the ideal of the national welfare state. In the words of Freeman (Reference Freeman1986), the welfare state is “inward looking”, seeking to take care of its own, and its ability to do so is premised on the assumption that “outsiders” can be kept at distance. But this is no longer possible in a world erased of borders and with supranational regulations requiring the outsiders to be granted full access to the welfare state (Cappelen Reference Cappelen2016). This tension stimulates outbursts of reactionary political activity, giving the political right material with which to appeal to voters and to challenge the left. According to Johns (Reference Johns2014), media sources have often portrayed the postenlargement migrants (often immigrants from Eastern Europe) in a negative light. They have thereby played a role in building ethnic tension, accusing them of lowering wages as well as being a burden on the welfare system. Mainstream politicians and government agencies have often reinforced these stereotypes (Johns Reference Johns2014, 10).

Still, it is not straightforward how intra-EU immigration affects welfare chauvinistic attitudes. According to intergroup contact theory (Allport Reference Allport1954), a larger share of immigrants decreases perceived group threat and thereby leads to less immigrant derogation (Schlueter and Wagner Reference Schlueter and Wagner2008), which would soften exclusionary preferences. On the other hand, a large relative number of immigrants can be expected to cause a snowballing in-group/out-group emotion of the majority population (e.g. Scheepers et al. Reference Scheepers, Gijsberts and Coenders2002), which again can increase intergroup tension and subsequently surge welfare chauvinism.

Intra-EU immigration and welfare chauvinism

There is a growing literature on how general immigration and ethnic heterogeneity affect social preferences. It has been suggested that in the United States (US), ethnically heterogeneous societies display lower levels of support for redistributive welfare programs (e.g. Gilens Reference Gilens1995; Luttmer Reference Luttmer2001; Alesina & Glaeser Reference Alesina and Glaeser2004). In Canada, however, the experience seems different, with no clear empirical evidence of a negative relationship between immigration/ethnic heterogeneity and redistribution preferences (Soroka et al. Reference Soroka, Johnston and Banting2007; Johnston et al. Reference Johnston, Banting, Kymlicka and Soroka2010; Banting, et al. Reference Banting, Soroka and Koning2013). Canadians (compared to Americans) are more likely to believe that immigrants are good for the economy; and in Canada ethnic diversity does not generally seem to significantly erode social solidarity (Banting Reference Banting2010). In Europe, evidence is more mixed and ambiguous than in the US and Canada. Some European studies find only a weak or no association between immigration and preferences for social spending (Crepaz and Damron Reference Crepaz and Damron2008; Finseraas Reference Finseraas2008; Mau and Burkhardt Reference Mau and Burkhardt2009; Senik et al. Reference Senik, Stichnoth and Van der Straeten2009; Stichnoth Reference Stichnoth2012), whereas others report negative effects (e.g. Ford Reference Ford2006; Eger Reference Eger2009; Larsen Reference Larsen2011). A recent study by Cappelen and Peters (Reference Cappelen and PetersForthcoming) finds in particular intra-EU immigration to be negatively associated with preferences for welfare state spending; other types of immigration, i.e. general (or non-EU immigration), only weakly relates to such preferences.

People have questioned whether the results from the US case are really applicable to European countries, given the peculiar racial history of the US (Freeman Reference Freeman2009). First, Western European countries have been (notably) diversified by immigration only in the second half of the 20th century, by which time they already had solid welfare institutions in place. Second, since the typical European welfare state is more generous and universal than the US welfare state, more people benefit from it, which assumingly gives it a broader base of legitimacy. Third, throughout much of Europe welfare state institutions enjoy much greater acceptability than can be explained by economic self-interest alone (Koning Reference Koning2011).

These differences can help explain why the evidence for a negative association between immigration and preferences for wholesale retrenchment is much weaker in Europe than in the US. However, the implication is not necessarily that immigration does not affect social preferences in Europe. Unease about immigration might provoke so-called welfare chauvinism rather than preferences for wholesale retrenchment (Koning Reference Koning2011). Welfare chauvinism is the notion that welfare benefits should be restricted to certain groups, usually to natives (Andersen and Bjørklund Reference Andersen and Bjørklund1990; Freeman Reference Freeman2009). As such, a welfare chauvinist is not in favour of across-the-board retrenchment; rather, welfare chauvinism represents nativist resentment against welcoming immigrants into the welfare system (Crepaz and Damron Reference Crepaz and Damron2008). This can occur in various degrees. People may want to exclude immigrants from the welfare system entirely, or they may rather want to restrict their access.

People in most European countries feel access should at least be restricted somewhat (e.g. Gorodzeisky and Semyonov Reference Gorodzeisky and Semyonov2009; Van Der Waal et al. Reference Van der Waal, Achterberg, Houtman, De Koster and Manevska2010, Reference Van Der Waal, De Koster and Van Oorschot2013; Koning Reference Koning2011; Mewes and Mau Reference Mewes and Mau2012). However, it is not yet fully clear which factors affect cross-national variation in welfare chauvinism, partly because of the scarcity of cross-national studies. In what follows, we outline two contradictory arguments related to this issue; the in-group/out-group theory and the intergroup contact theory.

The in-group/out-group theory

It has been claimed that people have a natural tendency to develop group identities and to differentiate between “us” and “them” (Allport Reference Allport1954). People are inclined to develop positive feelings towards people who share similar traits – e.g., ethnicity, religion, language (the in-group) – and negative feelings towards people who do not (the out-group) (e.g. Sniderman et al. Reference Sniderman, Hagendoorn and Prior2004). Consequently, the native-born population – the “in-group” – can be less inclined to include the “out-group” in their social benefit schemes. In other words, people exhibit so-called in-group bias, favouring their own kind. Out-group derogation is a related phenomenon, in which an out-group is perceived as being threatening to the members of an in-group, which often accompanies in-group favouritism (Hewstone et al. Reference Hewstone, Rubin and Willis2002).Footnote 2

As argued by Shayo (Reference Shayo2009), the relative size of the out-group can matter for social preferences. Preferences for redistribution in a country can decrease with the size of the out-groups; the reason being that increased distance to other agents (e.g. migrants) in the original group of identity (e.g. low-income class of natives) makes identification with a less redistributive group (e.g. high-income class/the nation as a whole) more attractive. Furthermore, some studies have found that the size of the migrant population – the “out-group” – directly affects discriminatory attitudes and feeling of perceived threat (e.g. Gijsberts et al. Reference Gijsberts, Scheepers and Coenders2004; Kunovich Reference Kunovich2004; Semyonov et al. Reference Semyonov, Raijman and Gorodzeisky2006). Related to this finding, it has been argued that in-group members believe that the welfare system disproportionately benefits ethnic minorities (Gilens Reference Gilens1995; Alesina and Glaeser Reference Alesina and Glaeser2004), which again can trigger welfare chauvinistic preferences. In fact, Mau and Burkhardt (Reference Mau and Burkhardt2009) find support for a negative relationship between the share of non-western immigrants and the willingness to grant equal social rights to foreigners.

Previous research on the relationship between how immigration affects social preferences has mostly focussed on general immigration. However, it is not unlikely that intra-EU immigrants are perceived differently by the native population than non-western (non-EU) immigrants. Some features of the former can make them less threatening to natives than the latter. Most importantly, traditional asylum and family reunification immigrants represent more of an out-group than intra-EU immigrants, the latter creating (comparatively) less heterogeneity. Furthermore, labour immigrants are in the host country to work; this is their raison d'être as immigrants. Studies show that they contribute (much) more to the financing of the welfare state than they take out (e.g. Dustmann and Frattini Reference Dustmann and Frattini2014). Refugee and asylum immigrants, on the other hand, do not migrate primarily for economic reasons. They have often fled armed conflict or persecution and are recognised as needing of international protection because it is too dangerous for them to return home. Because of this, natives can come to believe that labour immigrants contribute more to the welfare system and that they exploit it less, and therefore that they represent less of a threat.

However, other factors can make natives view non-western immigrants as less of an out-group than intra-EU immigrants. It has been argued that citizenship constitutes the basis of eligibility for welfare (Marshall Reference Marshall1950). The state’s welfare programmes are for its members. And it can be argued for a majority of the natives, asylum/refugee immigrants are seen as being more “members” of the host society than intra-EU labour immigrants, primarily because they aspire to become citizens – the primary purpose of their migration is precisely to acquire citizenship (in order to escape persecution/danger). However, this is not the case for intra-EU labour immigrants; they are primarily in the host country to maximise income for a period of time before returning to their home country. Thus, in terms of citizenship, asylum/refugee immigrants are more of an “in-group” than intra-EU immigrants.

Intergroup contact theory

Contrary to the in-group/out-group theory, intergroup contact theory holds that immigration can help to weaken welfare chauvinistic attitudes. According to intergroup contact theory, first proposed by Allport (Reference Allport1954), increasing contact between members of different groups can work to reduce prejudice and intergroup conflict. Related to our research question, this would mean that welfare chauvinism decreases with the amount of immigration (Mewes and Mau Reference Mewes and Mau2013) – under the assumption that more immigration also implies more (positive) contact, which is likely. Indeed, one of the two prevailing measures of intergroup contact is precisely the size of a minority group, the other one being personal contact between members of the majority and minority groups (Stein et al. Reference Stein, Post and Rinden2000, 285). Stein et al. (Reference Stein, Post and Rinden2000) find that the two measures are positively correlated: a higher proportion of immigrants increases the probability of intergroup contact, i.e. that people are more likely to have contact with immigrants when there are relative more of them. This finding is supported by Wagner et al. (Reference Wagner, Christ, Pettigrew, Stellmacher and Wolf2006).

Allport (Reference Allport1954) suggested that positive effects of intergroup contact occur in contact situations characterised by four key conditions: (1) Equal status: While difficult to define precisely (Pettigrew Reference Pettigrew1998), it implies that both groups must engage equally in the relationship – members of the group should have similar backgrounds, qualities and characteristics (Riordan Reference Riordan1978); (2) Intergroup cooperation: Groups need to work together in the pursuit of common goals (Aronson and Patnoe Reference Aronson and Patnoe1997); (3) Support of authorities, law or customs: Both groups must acknowledge some authority that supports the contact and interactions between the groups (Pettigrew Reference Pettigrew1998); and (4) Common goals: Both groups must work on a problem/task and share this as a common goal – exemplified by interracial sport teams (Pettigrew Reference Pettigrew1998). These key conditions seem overall applicable to intra-EU migrants, as they immediately take part in regular life within the new country since they integrate in the labour force.

However, empirical studies have established that contact can reduce prejudice even when these four conditions are not present, i.e. contact between in-group and out-group members reduces prejudice and intergroup conflict even in situations that are not characterised by equal status, common goals, etc. (see Pettigrew Reference Pettigrew1998 for a review of this literature).

At the cross-national level, some empirical studies explicitly support the argument that (a) intergroup contact indeed increases with the amount of immigration, and (b) this, in turn, softens anti-immigrant stances and leads to less prejudice (Wagner et al. Reference Wagner, Christ, Pettigrew, Stellmacher and Wolf2006; Schlueter and Wagner Reference Schlueter and Wagner2008). Another study by Mewes and Mau (Reference Mewes and Mau2013) explicitly examines how intergroup contact directly affects welfare chauvinism, but find little evidence. However, their study operationalises intergroup contact rather differently than ours. Most importantly, they measured intergroup contact through the ‘Konjunkturforschungsstelle’ (KOF) Personal Contacts index, which contains components such as the country’s percentage of international telephone traffic, international tourism, etc.Footnote 3 The KOF index was developed to measure an extent of globalisation, and it taps into how connected a country is to other countries. Furthermore, the KOF index cannot separate the possible effects of specific types of immigration (e.g. intra-EU immigration), something that we are particularly interested in. The share of immigrant population is a different operationalisation of intergroup contact than the KOF index, and one that fits our research aim better.

We want to emphasise that intra-EU immigrants embody a diverse group of immigrants, e.g., they represent 28 different countries. It is therefore plausible that the effect of intra-EU immigration on welfare chauvinistic sentiments depends on from which geographical area in the EU that the immigrants come from. More concretely, it has been argued that in particular Eastern European immigration has been politicised; it is specifically this group of intra-EU immigrants that has been the target of media attacks (Johns Reference Johns2014). In particular, Eastern European immigrants have been accused of putting downward pressure on wages and of abusing the welfare system, receiving benefits they are not entitled to. Right-wing parties, but also mainstream politicians and government agencies, have often reinforced these stereotypes (Johns Reference Johns2014). Furthermore, the Eastern European immigration has been abrupt and escalated dramatically since the enlargement in 2004.Footnote 4 Both these features of the Eastern European immigration, the sudden escalation and its politicisation, are the two conditions put forth by Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2010) for an out-group (such as immigrants) to be seen as threatening, and to become the target of political hostility (Reference Hopkins2010, 40). This can have theoretical implications. With respect to the in-group/out-group theory, one can expect Eastern European immigrants to be seen as more threatening than western immigrants, i.e. as more of an out-group. Regarding the intergroup contact theory, one can expect the softening impact of contact (on welfare chauvinism) to be less pronounced when the contact is between natives and Eastern European immigrants, than when it is between natives and western European immigrants. Recall that the positive effect of intergroup contact is particularly pronounced in situations where the natives and the immigrants (out-group) have equal status, and the negative stereotyping of Eastern European immigrants can cause the natives to perceive of them as being of lower status.

The United Kingdom’s (UK) withdrawal from the European Union (known as “Brexit”) is one illustration of the perceived tension between natives and in particular Eastern European immigrants. In the (UK) public perception, the rapid growth in immigration to the UK has been typically associated with the two rounds of EU eastern enlargement that took place in 2004 and 2007; and this immigration is one of the major explanations for why the UK chose to leave the EU (Alfano et al. Reference Alfano, Dustmann and Frattini2016).

Expectations

According to the in-group/out-group theory, welfare chauvinistic attitudes should increase with immigration, and thus,

H1: Higher levels of immigration are likely to lead to attitudes that are more welfare chauvinistic.

It can, however, be expected that this negative association is particularly pronounced for nationals of East European countries compared to other EU migrants. As emphasised, politically charged debates related to welfare chauvinistic issues have often focussed on labour immigrants, especially from Eastern Europe.

According to the intergroup contact theory, however, it is expected that welfare chauvinism is decreasing with the amount of immigration, because intergroup contact reduces prejudice and softens anti-immigrant stances; and thus,

H2: Higher levels of immigration are likely to lead to attitudes that are less welfare chauvinistic.

We expect that this negative association might be less pronounced when the focus is strictly on Eastern European immigrants, simply because Eastern European immigrants are profiled as more threatening (due to, as argued above, its sudden escalation and degree of politicisation), and therefore that the positive effect of contact is less evident for this immigrant group.

Furthermore, we expect that in welfare states where benefits tend to be proportional to previous income and social security contribution, welfare chauvinism will be lower than in welfare systems providing flat-rate benefits and financed through general taxation (for ease of terminology, we refer to the former system as Bismarckian and the latter as Beveridgean).Footnote 5 The argument for this expectation is as follows: we know from previous literature that people differ in their support for various groups of “needy” people (e.g. Van Oorschot Reference Van Oorschot2006). However, we also know that people’s attitudes towards group support seem to be strongly affected by the extent to which the different groups are seen as deserving or underserving, and one of the most important deservingness criteria is reciprocity, i.e. building up a personal entitlement to benefits through working/paying contribution (Van Oorschot Reference Van Oorschot2000, Reference Van Oorschot2006). Therefore, in Bismarckian welfare states it is likely that immigrants will be seen as more “worthy” recipients than in Beveridgean welfare states. We thus control the extent to which a country is Bismarckian, measured by how much of the total amount of social spending is financed by social insurance rather than general taxation (see the Method section for details).

This expectation has implications for our hypotheses. Our first hypothesis – that EU-migration strengthens welfare chauvinistic attitudes – should be particularly pronounced under Beveridgean systems, and less so under Bismarckian systems. We thus include a second, conditional expectation to Hypothesis 1:

H1b: The effect of intra-EU immigration on welfare chauvinistic attitudes becomes stronger with the increase in the proportion of welfare financing coming from general taxation.

Furthermore, the expectation that intra-EU immigration leads to less welfare chauvinistic attitudes, as formulated under our Hypothesis 2, would be specifically pronounced in systems that more resemble the Bismarckian system. Hypothesis 2 can thus be specified to include:

H2b: The effect of intra-EU immigration on welfare chauvinistic attitudes becomes stronger with the increase in the proportion of welfare financing coming from social security contributions.

Empirical strategy

In order to investigate the relationship between intra-EU immigration and welfare chauvinism, we adopt a multilevel approach. Welfare chauvinism is measured at the individual-level with a survey question, and immigration is measured at the country-level as the percentage of immigrants living in a country. Below we further discuss the operationalisation and methodology we use, and discuss how we address some of the challenges that come with those.

The individual-level part of the analysis is based on the fourth wave (2008) of the European Social Survey (ESS wave 4). This wave is particularly relevant for the study of welfare chauvinism because of its rotating module on welfare attitudes.Footnote 6 Indeed, the reason for using this specific survey is because it includes a question that indicates welfare chauvinism – to our knowledge, there are no other surveys that tap the concept of welfare chauvinism and cover such a broad range of EU countries. Furthermore, other waves of the ESS do not include this relevant question. The 2008 ESS thus offers us a unique possibility to study the multilevel nature of the relationship between welfare chauvinism and intra-EU immigration.

In addition, we supplemented these data with various data on immigration, as well as a number of other relevant country characteristics. The data from the ESS in combination with the availability of the supplemented country-level data allow us to include 21 relevant European countries: Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK.

Welfare chauvinism

Welfare chauvinism is tapped in the ESS 2008 with the following question: “Thinking of people coming to live in [country] from other countries, when do you think they should obtain the same rights to social benefits and services as citizens already living here? Please choose the option on this card that comes closest to your view”. People can then choose one of the following answers: (1) Immediately on arrival; (2) After living in [country] for a year; (3) Only after they have worked and paid taxes for at least a year; (4) Once they have become a [country] citizen; and (5) They should never get the same rights.

Main independent variables

Our main independent variable is intra-EU immigration. Eurostat provides data on the number of people living in an EU country who originate from another EU country. This number is then translated into a measure reflecting the percentage of the population. As a further robustness check, we include a second measure of intra-EU immigration. Here, we calculated the percentage of respondents from the ESS 2008 that reported having been born in another EU country, or in Norway or Switzerland. The two indicators of intra-EU immigration are with 0.945 very highly correlated.

Furthermore, the analyses include some other indicators for immigration. The reason for this is twofold. First, when looking at the effects of intra-EU migration, it is important to control for non-EU migration. This allows us to check whether it is intra-EU migration that drives the results, and not a possible correlation between different forms of immigration, i.e. that some countries simply attract more immigrants in general. This is particularly important since the indicator for welfare chauvinism does not specify a specific type of immigration. Second, it is pertinent to examine whether general or non-intra-EU migration has differential effects on welfare chauvinism.

We thus include a variable that indicates the number of all immigrants relative to the population (% migrants), as well as one that indicates the number of immigrants who do not originate from the EU (% non-EU migrants). The World Development Indicators of the World Bank provide data on these measures. Furthermore, as with the measurement of intra-EU migration, we use the ESS 2008 as a basis for a second measure of general and non-EU immigration as a robustness check. The correlation between the two indicators for general immigration is 0.807, and that of the indicators for non-EU immigration 0.587. The Appendix further details the measurement of immigration.

Conditioning variable

We want to test whether the relationship we find holds for all countries equally, or whether the relationship is conditional on specific country characteristics. Following our expectations, we focus on the extent to which a country has a welfare system where benefits are proportional to previous income/contribution. There exist no readymade index for this; however, the percentage of social protection that is financed through social insurance contributions (as opposed to general taxation) is argued to be a good proxy (Bonoli Reference Bonoli1997). The higher this percentage, the more Bismarckian is the welfare system (and, thus, the more likely the system is to offer earnings-related benefits). Conversely, the lower the percentage, the more Beveridgean the system is (and the more likely the system is to offer flat-rate benefits financed through general taxation). Data are provided by Eurostat (see CESifo 2008).

Control variables

Besides the level of intra-EU migration, other factors are likely to affect welfare chauvinism. Therefore, we included a number of alternative variables in order to control for their effects – the inclusion of these variables also helps to isolate the effect of interest here, that of intra-EU migration. However, they do not constitute the main interest in this study. For this reason, we only shortly discuss the control variables here, and include information about their measurement in the Appendix. We will not report or discuss the results regarding these explanations. The results are fully reported in the Online Supplement, in Tables S1 and S2.

The control variables include both individual- and country-level indicators. We emphasise different types of individual-level variables that previous research identified as affecting welfare chauvinistic attitudes (see, e.g. Coenders and Scheepers Reference Coenders and Scheepers2003; Reeskens and Van Oorschot Reference Reeskens and Van Oorschot2012; Mewes and Mau Reference Mewes and Mau2013): political orientation (on a left-right scale); individual characteristics (gender, age, education, income, employment status and whether a person thinks s/he is likely to need some form of welfare assistance); interpersonal trust (as well as how socially active a person is); and lastly, attitudes towards the EU, and whether the government should be in charge of providing welfare benefits.

In addition to these individual-level controls, we include different country-level controls.Footnote 7 Most notably, we include an indicator for the size of the welfare state in terms of the percentage of the gross domestic product (GDP) that is spent on social benefits. It has been argued that generous and expansive welfare states seem to foster tolerance towards immigrants and also produce less welfare chauvinism (e.g. Crepaz and Damron Reference Crepaz and Damron2008; Reeskens and Van Oorschot Reference Reeskens and Van Oorschot2012). This is our main and key control variable. Data for this measure are again provided by Eurostat.

There are other variables that may affect welfare chauvinism. However, with just 21 countries, not all of these can be included simultaneously. For each model we include a maximum of three country-level variables, meaning that we need to substitute some controls for others in order to assess their impact. We therefore reanalyse the main model, also including economic inequality, wealth and unemployment rate. Furthermore, it has been observed that unemployment rates are linked to welfare chauvinism (e.g. Mewes and Mau Reference Mewes and Mau2012), and so we control for unemployment. The Appendix details the measurement of these indicators, and the Online Supplement provides the results of the models that include these alternative controls (Table S3).

Estimation process

In order to test our expectations, we use a multilevel ordered logit regression model. The dependent variable that we use is a variable with categories that can be ordered. The distances between the categories, however, are not necessarily of equal distance, and the values attached to the categories do not mean anything except for the order in which they are placed. An ordered logit model does not assume that the distances are meaningful as such, and therefore offers a better option to analyse the data than an ordinary least squares regression, for example.

Moreover, because we are interested in testing a model that includes both country and individual-level indicators, we use a multilevel approach to analyse our data. We explicitly model the multilevel structure of the data in order to avoid too small standard errors, but also as to allow for variation in the level of welfare chauvinism at the country-level. We therefore use a random-intercept model. All models of interest are compared to a simple null-model where no independent variables are included. Both the country-level variance of the null-model and the models of interest are reported, as to allow for a comparison in terms of how well a model performs in terms of explaining this country-level variance.

We thus employ random-effects ordered logit regression in order to analyse the data. This procedure estimates an underlying score as a linear function of the independent variables as well as a number of cut-points. The latent linear equation to be estimated is as follows:

where x iu β are the fixed effect for i individuals and j countries based on the independent variable, z iu u u are the random effects based on the variance in the dependent variable on the country-level, and ɛ iu are the errors which are distributed as logistic. The outcome of the estimated model described in (1) returns values that can be interpreted as changes in the odds ratios, i.e. for a unit change in x, the odds from going to a higher outcome change with β. While the βs can be interpreted in terms of their sign and significance, and the size of the value can be compared within models, the value cannot be interpreted meaningfully without the cut-points. Since we are mainly interested in whether intra-EU migration has a positive or negative significant effect, and whether the effect is different from that of general or non-EU migration, we focus on the interpretation of this latent linear equation.

In addition, we discuss the predicted probability for the different categories of welfare chauvinism to further assess the substantive meaning of the results. On the basis of Equation 1, and using the cut-points that are estimated by the model, the predicted probabilities can be calculated as follows:

where v v is the vth cut-point. In our case, we have five outcomes for the dependent variable, implying that just four cut-points are estimated. In addition, it is assumed that v 0=–∞ and v 5=+∞. The predicted probabilities are illustrated for some of the models. The models do not estimate a constant since the cut-points already absorb the constant.

As an additional check for the robustness of the models that we discuss here, we included a replication of all models using a different statistical technique. While a multilevel ordered logit model is the most appropriate for the data that we use, it is also possible to estimate the models with a linear multilevel model, with random intercepts. The results of the replications with this different technique are reported in Table S4 in the Online Supplement, and further support the findings discussed below. Furthermore, we checked whether the results are driven by a particular country by rerunning the analyses excluding one case each time. The results remain largely the same, suggesting that not one case is an outlier with too high leverage.

Results

Before discussing the results of the multivariate analysis, we present the data for the main concepts in our study, by country. Table 1 includes the values for our dependent variable, welfare chauvinism, and for the main explanatory and conditioning variable, general migration, intra-EU migration (both total and only East European) and the social security system. The table is divided in three sections: section one includes the countries with the lowest level of welfare chauvinism, the second includes those with a medium level and the third has the highest level. Each section ends with an overall average of that section for each variable. First of all, it shows that Sweden is the country with the lowest average level of welfare chauvinism, whereas Hungary has the highest level. Many of the Scandinavian countries fall within the first category, of which the average level of chauvinism is 2.94, whereas there are many of the East European countries in the third category with an average level of 3.55.

Table 1 Empirical description of the main concepts

It is striking that welfare chauvinism is higher when the average percentage of immigrants, both general and intra-EU, is lower. While Table 1 simply reports averages, it preliminarily suggests support for the contact theory hypothesis. This does not seem to be the case for East European intra-EU immigration: There does not appear to be a particular pattern. When looking at the share of East European migration of general intra-EU migration we observe an opposite trend: countries that tend to have a higher share, tend to have a higher level of welfare chauvinism. However, it needs to be noted that there is substantial variation within each of the sections, especially when it comes to general immigration. Switzerland, e.g., has very high numbers of both general and intra-EU migration, making the average level of immigration in first section much higher. Furthermore, Table 1 illustrates that the countries with a lower level of welfare chauvinism have a slightly more Beveridgean type of welfare system than the countries with a higher level of chauvinism.

Welfare chauvinism and immigration: multivariate analysis

Table 2 shows the results of the multilevel multivariate ordered logit analyses – the full sets of results including the individual-level variables can be found in the Online Supplement, in Table S1. As discussed, the results in Table 2 reflect estimations for the underlying score as linear function, and can be interpreted as changes in the odds ratios. Table 2 shows that immigration has a negative effect: with each percentage increase, the odds of moving up one category, i.e. more welfare chauvinistic, decrease. Models 1 and 2 illustrate that this is the case for general immigration, while controlling for unemployment, social benefits and various individual-level variables. The effects are statistically significant and imply that an increase in general immigration leads to a decrease in welfare chauvinism. Unemployment and the level of social benefits – a broad indicator of how generous a welfare state is – have negative but nonsignificant effects on our dependent variable.

Table 2 The impact of intra-EU migration on welfare chauvinism

Note: Models reflect the results of multilevel ordered logit analyses and standard errors are reported between brackets. The full results including the individual-level variables are reported in the Online Supplement.

ESS=European Social Survey.

*p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01.

Models 3 and 4 further suggest that it is specifically intra-EU migration that leads to lower levels of chauvinism. Both models 3 and 4 show that the effect for intra-EU migration is negative and statistically significant, implying that chauvinism is lower when intra-EU migration is higher. It appears that the more natives are exposed to immigrants, the more they are willing to include them in the welfare system of their country. This is contrary to the expectation associated with the in-group/out-group theory, where it is assumed that perceived threat increases with more immigration, in turn increasing welfare chauvinism. These findings thus also underline the tentative relations presented in Table 1. Table 2 also shows that the effect of non-EU migration is negative but insignificant, emphasising that the effect of general migration on chauvinism is largely due to intra-EU migration.

Contact theory cannot explain the differential findings of intra-EU immigration and non-EU immigration. Although part of our finding supports the idea that people are less chauvinistic with more interaction with immigrants, it does not provide the full explanation. The driving forces behind contact theory (e.g. reduced xenophobia) can partly be offset by mechanisms related, e.g., to in-group/out-group dynamics (e.g. in-group favouritism), which can reduce the effect of contact. Both softening (e.g. contact) and hardening (e.g. ethnic heterogeneity) forces can affect welfare chauvinism simultaneously. Intra-EU immigration contributes little to ethnic, cultural and religious diversity when compared to non-EU immigration (Cappelen and Midtbø Reference Cappelen and Midtbø2016). Thus, even though contact between natives and intra-EU immigrants, and between natives and non-EU immigrants, has the same softening impact on chauvinism all else being equal, the softening impact on the latter can still be weaker because it is mitigated by non-EU immigrants being viewed as more of an out-group. The dynamics of the relationship between immigration and welfare chauvinism is more complex than often assumed, and our findings suggest that different explanations interact to produce a complex outcome.

Figure 1 illustrates the effects of intra-EU migration. For clarity purposes, we illustrate the findings based on a model that uses a dichotomized dependent variable, where people are categorised as either welfare chauvinistic (1) or not (0).Footnote 8 It shows the probabilities of someone being chauvinistic or not according to levels of intra-EU migration. The left panel of the Figure indicates that the probability of being not or moderately welfare chauvinistic is higher when there are relatively more EU immigrants. With zero immigration, there is a chance of just over 50% that someone is not chauvinistic, and this chance increases to just over 80% when there is about 12% of intra-EU immigrants (Switzerland). Conversely, people are less likely to be welfare chauvinistic when there are more intra-EU immigrants (right panel).

Figure 1 Welfare chauvinism and intra-EU migration in probabilities. Note: The full model on which this Figure is based is reported in the Online Supplement.

East European immigration and welfare chauvinism

Following the expectation that welfare chauvinism may be affected differently by nationals of Eastern Europe countries, we tested whether our finding is valid despite the inclusion of East European migrants. Put differently, considering the relatively recent inclusion of many East European countries in the EU and the general negative portrayal of immigrants from these countries, the relationship we found might be different for this subset of immigrants.

Table 3 reflects the results for the analyses where EU migration is divided into East European immigration and other EU immigration. Models 5 and 6 show that East EU immigration has no effect on welfare chauvinism, as is the case for non-EU immigration. The effect of intra-EU immigration seems to be due to western European immigrants. This finding highlights again that the explanation of the relationship between welfare chauvinism and immigration does not simply follow one theory. While more contact with East Europeans might soften welfare chauvinistic attitudes, they might be hardened because of the explicit negative (media) portrayal of these immigrants, resulting in stronger in-group/out-group dynamics.

Table 3 The impact of East European migration on welfare chauvinism

Note: Models reflect the results of multilevel ordered logit analyses and standard errors are reported between brackets. The full results including the individual-level variables are reported in the Online Supplement.

ESS=European Social Survey.

*p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01.

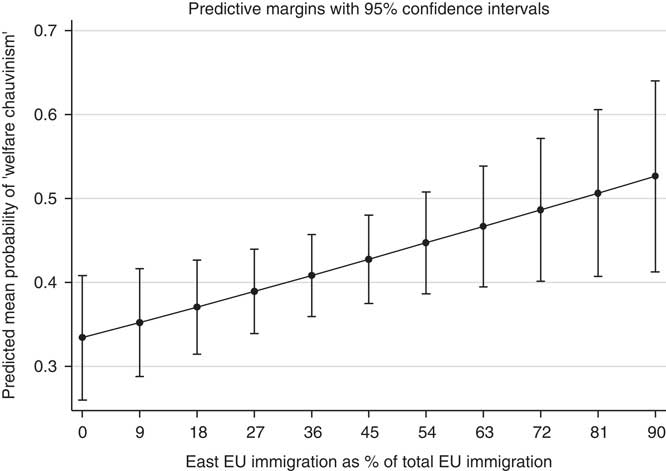

Moreover, while looking at East European immigration as a percentage of the total amount of intra-EU immigration, the results are different. Model 7 in Table 3 shows that when this group increases in size, levels of welfare chauvinism tend to be higher. This aligns with our theoretical expectations, that the softening (positive) impact of contact on chauvinism is less pronounced or even absent when the focus is strictly on Eastern European immigrants.

Figure 2 illustrates the effects of East European immigration as a percentage of intra-EU migration. The Figure is again based on a model that uses the dichotomised variable of welfare chauvinism. As the coefficient of the immigration variable indicates, the plots in Figure 2 follow the exact opposite patterns as those in Figure 1, which illustrates the effect of intra-EU immigration on welfare chauvinism: probabilities of having a nonchauvinistic attitude decline with the share of Eastern EU migrants, whereas the probabilities of having a welfare chauvinistic attitudes increase with that share. This aligns with both Hypotheses 1b and 2b: an increasing share of Eastern immigration strengthens the negative expectation that immigration leads to welfare chauvinism (in-group/out-group theory), while it weakens the expectation that immigration softens chauvinistic sentiments (intergroup contact theory).

Figure 2 Welfare chauvinism and East intra-EU migration in probabilities. Note: The full model on which this Figure is based is reported in the Online Supplement.

Welfare chauvinism, intra-EU migration and the conditioning effect of the social security system

Lastly, we examine whether our findings hold across all European countries equally, or whether it applies specifically to some countries. We test whether the source of welfare financing (social security/general taxation) conditions the relationship between intra-EU immigration and welfare chauvinism. Therefore, we included an interaction effect between this variable (i.e. the percentage of social protection financed through social insurance contributions, as opposed to general taxation) and intra-EU migration. Table 4 shows the results of this analysis.

Table 4 Conditioning the relation between welfare chauvinism and intra-EU migration

Note: The model reflects the results of multilevel ordered logit analysis and standard errors are reported between brackets.

*p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01.

Model 8 indicates that the relationship between migration and welfare chauvinism is unaffected by welfare financing. More precisely, the interaction term between migration and the share of social contribution coming from employers is negative, but it fails to be significant.

The positive coefficient of EU migration in model 8 would suggest that in hypothetical “pure” Beveridgean welfare states,Footnote 9 welfare chauvinism increases with intra-EU immigration, which aligns with Hypothesis 1b. However, the coefficient is not significant. Note that among the cases that we include, the amount of social insurance contributions ranges between 28.8% (Denmark) and 80.7% (Czech Republic).

The relationship between intra-EU migration and welfare chauvinism changes insignificantly according to the share of welfare financing that come from employers. The initial effect of 0.137 (for a hypothetical “pure” Beveridgean system) between immigration and chauvinism is reduced by almost 0.004 for each unit change in the social insurance financing (in percentages; 0–100). This implies that the relationship between EU immigration and welfare chauvinism becomes negative the more a country finances welfare through employer contributions. In a situation where a country would be half financed through social insurance contributions, the effect of intra-EU migration is about –0.456.Footnote 10 As a further illustration, in the extreme and hypothetical case that all welfare is financed through social contributions (a hypothetical “pure” Bismarckian system), the effect of intra-EU immigration would be−0.228,Footnote 11 significant at the 0.05 level. In essence, the estimation presented in model 8 indicates that the probability of having a nonwelfare chauvinistic attitude increases with the relative number of EU migrants in countries that resemble a Bismarckian system more, but not in more Beveridgean countries. However, as the interaction term in Table 4 is not significant, we cannot conclude that the effects are significantly different according to the amount of social insurance contributions to welfare.

Conclusion

One of the greatest challenges European welfare states face is the issue of how to include newcomers (Mewes and Mau Reference Mewes and Mau2013, 12). In this study, we were interested in how the mounting intra-EU immigration affects people’s willingness to grant equal social rights to foreigners. We argued that that the amount of intra-EU immigration can help explain cross-country variation concerning such willingness, and we posed two contradictory hypotheses. The in-group/out-group theory suggests that welfare chauvinism increases with the amount of immigration, whereas from the intergroup contact theory it follows that welfare chauvinism decreases with the amount of immigration.

We find support for the latter hypothesis; people tend to be less welfare chauvinistic in countries where there are relatively more immigrants.Footnote 12 We also found that it is indeed specifically intra-EU immigration that is associated with welfare chauvinism. In other words, welfare state solidarity with immigrants partly depends on whether immigration is driven by EU movement or not. We do not find that the relationship is different for more Beveridgean or more Bismarckian welfare systems: while it appears that the relationship is somewhat more pronounced in countries where welfare is financed more through social insurance contributions, this effect is not significantly different from that in systems where welfare is financed through general taxation.

Finally, we find that the relative size of Eastern European immigration can be vital with respect to how immigration affects attitudes towards welfare chauvinism. More specifically, the larger the size East European immigration relative to immigration from other EU countries, the higher the level of welfare chauvinism. This finding, we argued, can partly be explained by the in-group/out-group theory. When East European immigration dominates, it becomes easier for natives to view them as an “out-group” and to differentiate between “us” and “them”, which can result in welfare chauvinism.

Building on our study, future research should further explore the effects of intra-EU immigration. With an ever increasing mobility of labour within the European Union, as well as the increasing number of asylum seekers, questions about how people react to immigration – and different types of immigration – are important. Over the last decade, Europe has seen the rise of populist, extreme right-wing, as well as Eurosceptic parties. It is thus crucial that this issue is examined further.

One important element here may also be the way in which countries deal with immigration. Different countries have different ways of proposing how (different types of) immigrants need to integrate. It may be fruitful to examine these different regimes and policies, and see whether one is more successful than the other. Furthermore, the speed of immigration can play an important role in how people’s attitudes develop (see also Hopkins Reference Hopkins2010). There may be a difference between a steady increase in immigration of several years versus the sudden income of a large amount of immigrants at one moment in time. These, and more, issues need to be investigated further, as to shed more light on this important topic.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Stein Kuhnle and the three anonymous reviewers and editor for their valuable comments on the manuscript. The usual disclaimers apply. This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway [grant number 227048].

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X17000150

Appendix

Table A1 Operationalization