Over the course of his career, Martin Luther (1483–1546) repeatedly addressed the question of whether political resistance might be directed lawfully against superior secular authorities if they were to act tyrannically. Throughout the 1520s, Luther sided with the German princes who were supporting his reform movement as they put down riots at Wittenberg in 1522 and slaughtered the rebellious peasants of southern Germany during the Peasants’ Revolt of 1525. Despite his controversial positions here, Luther insisted that he was following the Apostle Paul, who in Romans 13 had advised the Christians at Rome to honor all higher secular authority as divinely ordained.Footnote 1 In the following decade, however, Luther was pressured by the Lutheran princes to supply a theological justification for them to defend their territories against the growing threat of an imperial invasion to restore Catholicism. If Luther failed to support the Protestant German princes, his reform movement might be doomed, yet if he sanctioned violence against a secular overlord, he risked violating God's Word and divinely ordained secular authority.

The debate during the past half century over this evolution of Luther's thought, beginning with the infamous Torgau conference in 1530 and reaching its fullest expression in the spring of 1539 with his Circular Disputation on the Right of Resistance against the Emperor (Matthew 19:21), when he sanctioned popular resistance to a papal Antichrist, has focused not so much upon whether or not Luther shifted positions on this critical issue of sanctioning imperial resistance as upon when and whether he did so willingly, or reluctantly, due to the new circumstances with which he was faced and pressure exerted by the German Lutheran princes.Footnote 2 Such interpretations of Luther supporting imperial resistance merit closer examination, however, for Luther wrote on this topic throughout his lifetime, and even the Circular Disputation on the Right of Resistance against the Emperor was by no means his final word on the subject.

During the 1530s, Luther declined to challenge legal arguments legitimizing imperial resistance put forth by Hessian and Saxon jurists on the grounds that, as a theologian, he was not competent to render a judgment in the field of law. Luther only gradually accepted legal arguments put forth by these jurists acknowledging the sovereignty of the imperial electors as equal or even superior to the authority of the elected Holy Roman emperor or, alternatively, delegitimizing the emperor's authority because he was guilty of notorious injustice, which would have exempted any Lutheran resistance from the admonition to honor superior secular authority in Romans 13. Meanwhile, though the threat remained high, the princes appealed to a future church council, which should have freed them from imperial aggression during the interim while providing a justification for defense in case of an unprovoked attack by Catholic imperial forces.

In the end, Luther remained true to his ideals and, by his own admission, underwent no transformation at Torgau in 1530; neither did his famous signed statement of the Wittenberg theologians in 1536, it turns out, reflect more than acceptance of the jurists’ legal competency. The solution to Luther's dilemma came with a revelation in early 1539 that took his understanding of the Antichrist to new levels by linking the emperor directly to the papacy. This solution reflected a highly original theological, rather than legal, argument—thus one within his area of expertise and competency—yet even here he built upon fundamental principles and articles of faith that had marked his ministry and theology since his early days, namely, the need for order and obedience to legitimate authority and the call for Christians to repent and renew their faith in God, coupled with the necessity to defeat the demonic forces of the Antichrist, which had never been legitimate in any sense or under the command of Romans 13, and the conviction that Christ would ultimately emerge as the victor in the final struggle to come. Here Luther's long-standing characterization of the pope as Antichrist found a new political application as he sharpened the definition of “legitimate” authority and his understanding of the two kingdoms and three estates to exclude the papal Antichrist and his demonic agents, now also including the emperor, even as he continued to uphold the duty of obedience to “legitimate” superior authority mandated in Romans 13.

Despite viewing the imperial and papal struggle in such apocalyptic terms, the reformer consistently defended obedience to “legitimate” political authorities, even if tyrannical, with the exception of when sovereign rulers commanded their subjects to violate godly law. In such cases, Luther advocated civil disobedience and other forms of nonviolent resistance—prayer, penning treatises and hymns, preaching God's Word, and providing counsel to his sovereigns—that would violate neither conscience nor divine sanctions. At the same time, magistrates and subjects owed no allegiance to sovereign rulers who were their equals or who had been deposed or otherwise had lost legitimacy. Luther's carefully constructed arguments evolved as he strove to walk a fine line amidst the political circumstances and stresses under which he was operating. This allowed him to remain true to his conscience and his understanding of the Word of God, yet the emerging Lutheran resistance theory would exert a long-term impact upon later Lutheran and Calvinist resistance theorists, especially during the siege of Magdeburg (1550–1551) and during the French Wars of Religion, the Dutch Revolt, and the English Revolutions.

Luther's Early Political Thought

Early on, in A Sincere Admonition by Martin Luther to All Christians to Guard against Insurrection and Rebellion (1522), written in response to the riots at Wittenberg, the reformer rejected insurrection. His sympathies would always “be on the side of those against whom insurrection is directed, no matter how unjust their cause.” Likewise, he would always oppose “those who rise in insurrection, no matter how just their cause.”Footnote 3 In Temporal Authority: To What Extent It Should Be Obeyed (1523), Luther defined secular authority as a divinely sanctioned institution designed to protect the righteous and punish the wicked, which must always be obeyed except when temporal rulers order their subjects to violate godly law, in which cases subjects are dutifully bound to refuse, yet nevertheless prohibited from resisting their legitimate ruler with violence.Footnote 4 He continued to hold this position (while also admonishing the princes to reform their ways) in his writings against the peasants of southern Germany who rebelled against their lords in 1525.Footnote 5 The following year, Luther took up the plights of soldiers in Whether Soldiers, Too, Can Be Saved (1526). Here he made it clear that rulers have the right to conscript their citizens for military service, and yet, should the soldier's ruler command him to fight an unjust war, the soldier should refuse to obey the command and leave the lord's service. A rebellion by force against a legitimate prince would violate the divine order and all godly authority. And just as subjects owe obedience to their prince as their overlord, so too the prince owes obedience to his emperor. Not only does God sanction all secular earthly authority, but He also chooses whom he wills to occupy these offices. Conversely, if God chooses and appoints secular rulers, He can remove them from their positions of power.Footnote 6 In these treatises, Luther also expounded upon his complex understanding of the two kingdoms, contrasting the regnum spirituale, governed by the Word and focused upon the first table (the first three commandments in Exodus 20, dealing with believers’ vertical relation to God), with the regnum corporale under the second table (commandments four through ten, addressing horizontal human relations with each other), though the distinction and separation between the spiritual and earthly kingdoms was never complete in Luther's thought.Footnote 7

Privately, a prince remained an individual Christian (persona privata), though publicly he served as a political ruler (persona publica). In addition, Luther called upon the German princes to summon a council to reform the church in his address, To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation [. . .] (1520), but instead, the few German princes still at Worms several days after the final session of the diet had confirmed and antedated the Edict of Worms (1521), which condemned Luther and his followers along with his books and forbid anyone from aiding him or printing his writings without approval of the bishops. Not surprisingly, by 1523 Luther had developed his thought further in Temporal Authority: To What Extent It Should Be Obeyed; his two kingdoms doctrine no longer recognized the right of political sovereigns to intervene in the first table. For the next few years, he advocated complete separation of the two kingdoms, but after 1530, as the need for protection and more effective organization of the territorial church emerged, Luther charged the prince with limited oversight of the state's religion (cura religionis), including insuring religious conformity in public worship and protection of the first as well as the second table. Never was this to be accomplished in an overbearing, tyrannical fashion that would usurp the spiritual and preaching authority of the ministers or dictate religious belief, but rather, in a manner that would ensure the peace and security of the church. The divinely ordained nature of temporal rule raised the related issue of the appropriate role for secular princes in defending doctrine and the church. In the “confessionalization” process that emerged, the Lutheran Church developed a close bond with the German princes—reinforcing and legitimizing the rule of these sovereigns, who in turn were bound to defend and enforce the Augsburg Confession (1530) as the “true religion.” Yet this left unsettled the answer to the question of obedience to a Catholic imperial overlord who demanded that they violate or even abandon the Lutheran faith.Footnote 8

The Constitutional Argument of the Hessian Jurists

In the wake of the defeat of the French by imperial forces at Pavia (1525), Charles V and Francis I signed the Peace of Cambrai in August 1529. The invasion of Austria and the siege of Vienna by the Ottoman Turks in September and October of that year ultimately failed, forcing the Turks to withdraw their forces to Hungary and allowing Charles V to turn his attention back to the Lutherans. Coupled with the revocation of concessions granted to the Lutheran princes at the First Diet of Speyer (1526), this increased the likelihood that not merely the forces of German Catholic princes, but also those of imperial Spain might compel the German Lutheran territories to return to Catholicism. The six Lutheran princes and fourteen imperial free cities famously “protested” against the reinstatement and immediate implementation of the Edict of Worms at the Second Diet of Speyer in 1529. In response to their Confession at the Diet of Augsburg (1530), the emperor issued the Confutatio Pontificia, drafted by theologians under Johann Eck, which set forth a clear statement of Catholic doctrine with which the Lutherans were expected to concur. The Augsburg Recess (1530) demanded that Lutherans reenter the Catholic Church by April 15, 1531, or face a military confrontation and the judgment of those arrested by the Imperial Supreme Court, despite the fact that an appeal to a future “free, general, Christian council” was still pending.Footnote 9

The threat appeared deadly serious: an imperial emissary confided to Elector Johann of (Ernestine) Saxony a diplomatic message sent by Charles V stating that, should the elector refuse to submit to his authority and return to the Catholic faith, the emperor would evict him by force and replace him on his throne with Duke Georg of (Albertine) Saxony.Footnote 10 A defensive response by the Lutheran princes to an attack by the Catholic forces of princes of equal rank would pose no moral difficulty, but in this case, the German Catholic princes would be acting on the authority of the emperor and thus theoretically would be superior in authority to the Protestants. To complicate matters further, by October 1529, Landgrave Philip of Hesse and the militant Swiss reformer Ulrich Zwingli were no longer focusing upon a defensive response; instead, they were contemplating a preemptive strike with French aid against imperial forces to the south that would divide the eastern and western Austrian lands.Footnote 11 When Elector Johann queried in regard to joining the Protestant alliance, Luther informed the elector that the Wittenberg theologians could not in good conscience sanction the formation of a Protestant league. Instead, Luther advised the elector to devote himself to prayer and trust in God for deliverance from the present danger.Footnote 12

Luther to date had argued for what Eike Wolgast has labeled a “command-obedience relationship,” in which the German princes, though sovereign over their own territories and subjects, nevertheless were mere subjects in the emperor's presence because “each prince had received his office from the emperor.”Footnote 13 In late 1529, however, Landgrave Philip and the Hessian jurists began arguing that the Holy Roman Empire was a constitutional federation ordained by God with a conditional relationship and mutual obligations existing between the emperor and the seven imperial prince-electors who, unlike the emperor, ruled absolutely in their respective territories with divinely sanctioned authority derived directly from God. At least since 1400, when the four Rhenish electors had voted to depose Wenceslaus IV as King of the Romans, the consensus had been that, under imperial law, the electors possessed not only the power to elect, but also to depose, a tyrannical emperor (or emperor-elect) who failed to honor the limits of authority imposed upon him by the imperial constitution and his coronation oath.Footnote 14 In letters to Margrave Georg von Brandenburg–Ansbach and to Elector Johann of Saxony, Philip expanded the Apostle Paul's argument in Romans 13 to assert that, unlike imperial Roman governors (schlechte landtpfleger) of Paul's day who owed the emperor complete obedience and could be replaced by him at will, the German territorial princes (now expanded beyond the electors) were divinely sanctioned sovereigns equal to the German emperor, who ruled as a primus inter pares by virtue of his electoral capitulation and coronation so long as he upheld imperial law. In the case of an invasion, the German Lutheran princes would be obligated to safeguard the physical well-being and salvation of their subjects against the Catholic forces of the emperor.Footnote 15

Asked for his response, Luther reminded Elector Johann that the princes were dutifully bound to obey the emperor so long as they recognized him as such and did not depose him, that at most they could refuse to obey his commands if they violated godly law. Protestants were not yet banned, nor had imperial forces invaded Germany, so military action would be premature, “even if the emperor were a sovereign of equal standing.” Instead, the elector should seek peace. If the emperor should violate his oath and duty, his subjects were still bound to recognize his authority. Otherwise, they ran the risk of anarchy, although if the electors deposed Charles, he would cease to be emperor. In the meantime, if he were to attack his own subjects unjustly and imprison them, kill them, or exile them, then the princes should refuse to obey him or to participate in his wrongful actions. Echoing the words of Peter and the other apostles, Luther wrote, “If the emperor will persecute our subjects, who are also his, let him do it on his own conscience; we cannot prevent him, but we will not help him or consent to it, for ‘we must obey God rather than men.’” Beyond this, he assured the princes, “In so far as we act in this way and commend our cause to God and pray to Him with complete confidence and put ourselves in such peril for His sake, He is faithful and will not desert us and will find the means to help us and maintain His Word, as He has done since the beginning of the Church, and especially in the days of Christ and the apostles.”Footnote 16

Fundamentally, Luther's position had not changed. For the first time, however, following the argument now being put forth by Philip and the Hessian jurists, Luther conceded that resistance might be possible, albeit only if the emperor first were lawfully deposed by the electors in accordance with imperial law. Here the landgrave harked back to the double oath, which the electors swore not only to the emperor, but also to the empire.Footnote 17 Still, this possibility seemed remote since the seven electors included the archbishops of Trier, Mainz, and Cologne plus the Catholic elector of Brandenburg. Moreover, although chapter 2.4 of the Golden Bull (1356) granted the majority of four of the seven imperial electors the power to elect the Roman king and prospective emperor, it said nothing of their power to depose him. Chapter 5.2 awarded jurisdiction over the Roman king to the Count Palatine, but this could only be exercised at the imperial diet in the presence of the king.Footnote 18 Thus any proposal for deposing Charles V would have been unlawful unless the deposition were conducted at the imperial diet with Charles V present.

Three of Luther's commentaries on the Psalms from this same period bear particular relevance on the subject of obedience to superior rulers. The first two date from 1530, the third from five years later. In his Commentary on Psalm 118, which would resonate later with the pastors and political theorists at Magdeburg, Luther criticized those “haughty bigwigs” and “smart alecks” who dared to think that they, rather than God, control everything here on earth. True, the reward for those who honor God's Word is suffering and mockery from their opponents, so that at times the world appears to be upside down, with the ungodly receiving visible, albeit temporal, blessings from God, and the faithful suffering here on earth, though assured of the eternal reward of everlasting life. One should never doubt who is in control, for “what can an emperor, a pope, a king, a prince, or the entire world do against God?” They would receive their just reward. King David had taught that one should never trust even a pious priest, and yet the priest's office had been ordained by God. So, too, the faithful should never rely upon or trust their secular princes, but neither should they resist or rebel against their authority. Believers “finally conquer, no longer by the sword but by the Word of God; for Christendom does not fight with a physical sword.” If believers pray that God allow his name to be “hallowed and honored” rather than “blasphemed,” do they not believe that their prayer will be heard, and that “this prayer will discharge the gun” through the Turk or some other plague? Above all, to ensure that one honors God's name properly, the believer should listen to his or her conscience, which “cannot deceive God.” Luther reminded his readers that “holy heathen” resort to “siege and persecution,” words reminiscent of the siege of Vienna in 1529 by the Ottoman forces of Suleiman the Magnificent that would ring true again for those under siege at Magdeburg in 1550 by the Catholic forces of Elector Moritz of Saxony, yet they would never accomplish their goal, for “who can succeed against the Lord?” Let them do what they will, for “God's Word endures forever.” Clearly, Luther had not strayed from his position in 1523. Christians must endure and suffer, but not violently resist evil superiors, trusting in God to set things right in accordance with their prayers and his divine will.Footnote 19

It is precisely at this point that one can discern a shift in Luther's thinking, in dialogue with Melanchthon, on the role territorial princes should play in supporting and protecting the Lutheran Church. In his Commentary on Psalm 82, composed in early 1530 and completed on the eve of his departure for Augsburg, Luther again declared that “the offices of government, from the least to the highest, are God's ordinance.” Subjects should obey their rulers as they do God and subject themselves to their authority, for whoever opposes the rulers whom God has appointed despises, disobeys, and resists the “true Supreme God,” and breaks his oath of loyalty to his ruler. The sovereign oversees the “congregation [Gemeine] of God.” Luther used this term interchangeably to refer to the local church and the town or even some combination of both in the sense that these communities overlap, so that at times it could refer to any of the three estates, ecclesia (church), politia (state), or oeconomia (household). When all goes as intended, the fear of God and humility govern jointly as subjects willingly obey their rulers even as rulers govern their subjects justly and thereby keep the peace. The heart of the psalmist's message lies in verses 2–4, which, Luther advises, “every prince should have painted on the wall of his chamber, on his bed, over his table, and on his garments.” Herein are found the three virtues of temporal government: providing justice for Christians while repressing the godless; helping the poor and disadvantaged such as widows and orphans; and keeping the peace. Verse 2, Luther noted, “demands the first virtue: that the gods, that is, the princes and lords, shall honor God's Word above all things and shall further the teaching of it.” Together, these three virtues begged the question: should the secular ruler act to suppress religious heresy or blasphemy and sedition? The secular monarch, Luther insisted, should punish blasphemy accompanied by sedition because, though arising out of religion, they threaten the civil peace and existence of the divinely sanctioned secular state. Righteous rulers, however, should punish no one “without first seeing, hearing, learning, and becoming certain that he is a blasphemer.” Here Luther acknowledged the secular ruler's entry to the first table, relations with God otherwise associated with the spiritual kingdom overseen on earth by pastors and theologians. But how should one regard a tyrannical ruler who viewed the “true gospel” as heresy and judged his subjects to be blasphemers? Persecution by tyrannical rulers should not be surprising, for even “the kings of Israel killed the true prophets.” Since God often judges and overthrows impious kings and lords, Luther prayed for a regime to come that would honor God's name and keep His Word, namely “the kingdom of Christ.”Footnote 20

In his Commentary on Psalm 101 (1534–1535), Luther reaffirmed his understanding of the two kingdoms as separate and distinct, yet cooperative realms fulfilling God's will here on earth. Extraordinary leaders [Wundermänner] such as King David and Duke Frederick the Wise serve and cooperate with God to enhance his honor, promoting God's Word “in a proper Christian way,” by maintaining “pure doctrine and divine ordinance with true sincerity and spirit.” Thus David emerges as the king with just the right balance who, rather than acting as lord of the Word, posits himself as God's “humble subordinate and a faithful servant” reigning over the two kingdoms and all persons, baked “like one cake, every one of them helping the other to be obedient.” Whether king, prince, or lord, the extraordinary leader melds the first and second tables, directed vertically toward God and horizontally toward fellow human beings, the first by pointing out “how to serve God,” and the second by keeping “the people within the law” while “seeing to it that body, property, honor, wife, child, house, home and all manner of goods remain in peace and security and are blessed on earth.” Paradoxically, however, rather than forging a theocracy, Luther believed that the two kingdoms should remain separate despite the fact that Satan “never stops cooking and brewing these two kingdoms into each other.” Power-hungry secular rulers seek to emend the Word of God or dictate what should be preached. Conversely, spiritual leaders endeavor to rewrite the civil law, even though they have no authority from God or from the people to do so. Tyrants, meanwhile, should take heed, for throughout history God “has smashed many tyrants who did not want to believe it until they experienced it.” Submission to authority and a refusal to obey illicit commands, accompanied by fervent prayer and faith that God will not allow this oppression to continue in the long term, were appropriate responses to tyranny, not armed resistance.Footnote 21

The Torgau Conference of October 1530 and Luther's Warning to His Dear German People (1530–1531)

In October 1530, as tensions continued to escalate, Elector Johann's chancellor, Gregor Brück, and the other jurists at the Saxon court devised yet another line of argument to justify imperial resistance, this derived from private Roman and canon law. Brück pointed to four instances in which one might legitimately resist a judge who was proceeding unlawfully: first, if the judge rendered judgment during an ongoing appeal when all judgments should be suspended; second, if he proceeded by oppressing the defendant extra-juridically, rendering “irreparable” damage; third, if the judge proceeded in accordance with his jurisdiction, albeit unjustly, also an “irreparable” grievance; and fourth, when the judge's sentence was “notoriously unjust.” Should the emperor attempt to impose his judgment in matters of religious faith, he would be exceeding his jurisdiction and thus would be no judge at all, for “in matters of faith the emperor has absolutely no jurisdiction whatsoever, . . . but is a private citizen as far as judicial inquiry and examination and judgment [are concerned].” Given that the Lutheran princes’ appeal to a future church council to resolve Germany's religious question was still pending, Brück argued, “the injustice of the emperor is thus notorious and indeed far worse than notorious.”Footnote 22 Hence the German princes might lawfully take up arms against the emperor who, in excess of his legitimate authority, was attempting to intrude into the spiritual realm and coerce the Lutherans to return to the Roman obedience.

Upon the emperor's insistence, the chief topic of discussion at the Diet of Augsburg in 1530, aside from the ongoing threat posed by the Ottoman Turks, had been “the division in our Christian religion” and how the diet might achieve unity in the faith.Footnote 23 Afterward, Elector Johann of Saxony convened the Wittenberg theologians together with the Hessian and Electoral Saxon councilors at Torgau in October 1530 to offer him their collective advice. Here Luther and his colleagues received the memorandum previously drafted by the legal advisers of Elector Johann on the question: “In what cases may one resist the governing authority?” The Wittenberg theologians to date had been (and still were) unwilling to accept a juridical argument based upon natural law on the grounds of self-defense (vim vi repellere licet). Luther and his associates had already been presented with Landgrave Philip's and the Hessian jurists’ constitutional theory of resistance, but now they learned that a notoria injuria inflicted upon the estates by the emperor might licitly allow the electors under private Roman and canon law to resist the emperor or anyone acting unjustly in his name. In accord with Luther's doctrine of the two kingdoms, the theologians acknowledged the jurists’ competency over their own in matters of law and conceded that one should obey temporal laws “so long as [weil] the gospel does not teach anything contrary to them.”Footnote 24 Even “with this concession to the legal and political realities,” Eike Wolgast observed, “Luther still proceeded from the premise that secular law could not violate the rules of human coexistence contained in the gospel.” Whereas an individual citizen had no alternative but to follow the example of Christ, refuse to obey a command of his superior if it violated godly law, and suffer the consequences as a persona privata, decisions about whether imperial, Roman, or canon law would sanction imperial resistance by the prince, viewed as a persona publica obligated to defend his subjects, would be left to the jurists to decide. Wolgast has labeled Luther's “reluctant” shift here the Torgauer Wende (“Torgau Turning Point”). In a supplemental memorandum as well as in his personal correspondence with Landgrave Philip, however, Luther and his circle of theologians were careful to insist that peaceful methods should first be pursued through direct negotiations with the emperor.Footnote 25 At this point, since he was not a lawyer, Luther was compelled to concede—though he could do so without violating his conscience or earlier writings—that the princes might resist the emperor if the legal conditions, upon which he was not competent to pass judgment, were fulfilled in the eyes of imperial law. Yet in a written exchange that followed, Luther reassured Nürnberg City Secretary Lazarus Spengler that, despite the fierce debate that had taken place at Torgau, he had not changed his position.Footnote 26

Hoping to obtain a more forceful statement following the Torgau conference, Philip of Hesse asked Luther to write more extensively on the subject. The result was Luther's Warning to His Dear German People (begun in October 1530, but not published until April 1531), which later was reprinted during the Schmalkaldic War. Here Luther steadfastly maintained that the Lutherans could not be held accountable for the coming war, for they had neither fomented war nor advocated insurrection. On the contrary, the evangelicals had “constantly and ceaselessly pleaded and called for peace.” Luther did not advise anyone to wage war or offer resistance other than those who were enjoined and authorized to do so in Romans 13, but if the “murderous and bloodthirsty papists” who had “no law, either divine or human,” on their side, should wage an unjust war against the German princes and people, he would refuse to pass judgment on the princes, “accept their action and let it pass for self-defense” as the obligation of princes to defend their subjects in accord with their oaths and natural law. Ultimately, the determination as to guilt and accountability should be left “to the law and the jurists.” Yet as the “prophet of the Germans,” Luther added a stern warning to those German Catholic princes who might obey Charles V's command to attack the Protestants. If the emperor should issue such a command, no Catholic should obey him, for in giving such a command the emperor would be disobeying God and contravening divine as well as imperial law and violating his coronation oath; henceforth, no subject would owe him allegiance. Those who sided with emperor and pope would be compelled to burn German New Testaments, Lutheran catechisms, hymnals, prayer books, and psalters and also condemn and abandon the women whom the Lutheran pastors had married along with their children. In sum, any individual entering the fray on the side of the combined papal and imperial forces would subscribe to the guilt of all the abominations that had been and still would be committed by the Antichrist and his forces and, as a result, would “lose both body and soul eternally in the war.”Footnote 27

The tone and underlying message of Luther's treatise were not lost upon Duke Georg of Saxony, who issued an anonymous rebuttal, entitled Against Luther's Warning to the German People: Another Warning through an Obedient Nonpartisan (1531). Duke Georg argued that the Lutherans, not the Catholics, were arming and promoting rebellion and insurrection, leaving the emperor little choice but to put down the rebellion by force. Though far from innocent, Catholics were not guilty of promoting war. The emperor sought peace, but if things continued as they were headed, both sides would be destroyed.Footnote 28 Luther responded with one of his most venomous treatises, Against the [Character] Assassin at Dresden (April/May 1531). Here the reformer countered that the papists, rather than the Lutherans, were at fault in arming and preparing for war. If the emperor moved forward with an attack on the Protestants, it could only be because he was being duped by the papists. Luther's implication here was clear: in the event of an attack on the Lutherans, neither the emperor nor Duke Georg, acting on the emperor's and pope's behalves, would be considered a legitimate superior authority. German Catholics should disobey the emperor and refuse to serve in his army if conscripted for such an unjust attack upon the Lutherans and against God. Presenting historical and scriptural evidence, Luther argued that the world was full of Cains and Abels, those who sought to murder and those who strove to live in peace. The Cains of this world were always fearful that the Abels might rise up against them. Thus, although the Lutheran princes sought peace at the Diet of Augsburg, the Catholics had issued sufficient threats for the Lutherans to expect the worst. Henceforth Luther would end his prayers by heaping curses and rebukes upon the papists and their supporters. In closing, however, Luther insisted that he held a “good, friendly, peaceful, and Christian heart toward everyone.” It comes as no surprise that few Catholic leaders believed him, or that the Magdeburg theorists would later rely upon this treatise in building their defense.Footnote 29

Luther's Political Thought during the 1530s: The Continuing Problem of Notorious Injury

Throughout late 1531–1532, attempts were made to achieve a lasting religious peace throughout the Holy Roman Empire. This afforded some hope to the Lutherans since Charles V was seeking the electors’ consent to have his brother, Austrian Archduke Ferdinand I, crowned king of the Romans, thus as Charles's heir apparent and successor as emperor in a move that would secure the imperial crown for the Habsburg dynasty. Ferdinand was elected at Cologne in December 1531, albeit without the support of Elector Johann of Saxony. With Philip of Hesse leading them, some of the Lutheran rulers continued to protest Ferdinand's election until it was finally recognized by the princes in 1534. Meanwhile, pending a general council to resolve the religious dispute, Charles offered the Lutheran territories toleration as a quid pro quo in return for the German princes’ promises to maintain peace and to support the military campaign in defense of the Habsburg kingdom of Hungary against the Ottoman Turks.Footnote 30 In 1531 and again in 1532, Charles suspended suits to reinstate Catholic ceremonies and to restore Catholic clerical incomes and properties in Lutheran territories. Additionally, though at first implemented as a temporary measure to extend religious toleration, the Nürnberg Anstand (Nürnberg “Standstill” or Truce) of 1532 would be renewed in 1534 as the Münster Anabaptist insurrection demanded a bi-confessional response, and again as the Truce of Frankfurt in 1539, this time recognizing Germany as one empire with two religions and paving the way for the religious settlements of the Peace of Augsburg (1555) and the Treaty of Westphalia (1648). Yet this outcome was far from certain during the turbulent 1530s, while convening a future church council hung in the balance. Catholic resistance would harden and war would come before a resolution to the problem of multiple faiths within the empire was achieved. Nevertheless, hopes for peace remained in play until the very end.Footnote 31

The regents and councilors of the Margraviate of Brandenburg–Ansbach and the city councilmen of Nürnberg drafted an ecclesiastical ordinance that they sent to Luther for assessment in July 1532. Although the Wittenberg theologians approved the ordinance, they advised omitting a passage on governmental authority that denied legitimacy to a tyrannical lord. Here Luther and his colleagues cautioned, “Even though Holy Scripture and secular law teach how to deal with an unjust ruler, nevertheless an evil governmental authority still remains governmental authority, as every understanding person knows. For if in God's eyes an evil governmental authority should be no governmental authority, then the subjects would be free of all obligations.”Footnote 32 Luther again refused to sanction violent resistance against a tyrannical ruler, especially when the possibility of peace remained.

At the request of Elector Johann Friedrich and in response to a new threat following Pope Paul III's summons to a church council that many feared might rule against the Protestants’ appeal, Philipp Melanchthon drafted a formal opinion on behalf of the Wittenberg theologians in December 1536 that was signed by Luther, Johannes Bugenhagen, Caspar Cruciger, Justus Jonas, Nikolaus von Amsdorf, and Melanchthon. Cargill Thompson argued that this draft signaled “a radical break not only with their earlier views but also with the position they had taken up at Torgau.”Footnote 33 The tract addressed, first, the proper response to the proposed church council, and second, whether or not the princes had the right to resist the emperor with force.Footnote 34 Elector Johann Friedrich had proposed convening a rival council, but this risked exposing the princes to charges of schism. The problem was that the emperor was now the commissioner of the council, which empowered him to enforce the council's decrees. With regard to the question of imperial resistance, Melanchthon insisted, “Each prince is responsible, above all, for protecting and administrating his Christian subjects and their public worship services against all unjust violence, just as also in worldly affairs a prince is responsible for safeguarding a devout subject against unjust violence.”Footnote 35 Basing their argument upon observing the second commandment, against blasphemy, which now took precedence over Romans 13, Melanchthon and the Wittenberg theologians returned to the argument of the Saxon jurists. Should the emperor exercise his power unjustly by punishing or attacking the Protestants while their appeal was pending before the council, he would be guilty of notoriam injuriam. The princes would be justified in resisting him as a private individual, rather than as the lawful emperor, in defending themselves and their Christian subjects. Such a response would also be justified in the event that the forthcoming church council returned a judgment against their appeal, giving the emperor a mandate to attack and thereby inflict notorious injury upon the princes and their subjects. And should the pope attempt to impose “public idolatry” (violating the second commandment through the worship of crucifixes and statues of Mary) and other “public injuries” upon them, the princes could resist him and defend their subjects just as they would do if the Turks tried to establish Islam throughout the Lutheran territories, even as Judas Maccabaeus had once done in setting himself against Antiochus.Footnote 36

Although Melanchthon had composed the document, Luther appeared to leave no mistake about his own sentiments. He was the first to sign it and did so with flare: “I, Martin Luther, will also help with prayers and also (should it become necessary) with the fist.” Still, most of the 1536 opinion addressed legal issues upon which the theologians had already determined that they were not competent to rule. Their contribution here was in honoring the second commandment before Romans 13. In his closing argument, however, Melanchthon spoke against the council's potential ban on clerical marriage, arguing that the outlawing and separation of priestly wives from their husbands constituted “a notorious injury, in which natural reason as God's order is itself the judge.” As Wolgast observed, in signing the document “with the fist” Luther was almost certainly responding to these final sentences of Melanchthon's opinion opposing a ban on clerical marriage and the dissolution of existing clerical marriages rather than reacting to the entire report.Footnote 37

Luther's Evolving Theology in 1538–1539: The Two Kingdoms versus the Three Estates

In 1538–1539, both the Schmalkaldic League and the Catholic League mobilized their armies in preparation for war. As the Schmalkaldic League's leadership was meeting at Frankfurt in February 1539, the hawkish Philip of Hesse advocated a preemptive strike; in contrast, Strasbourg magistrate Jacob Sturm argued for maintaining the peace. Though a preventive war might seem to human reason to be an effective means of eliminating the threat, Sturm argued, one should put his trust in God first, and in armaments only in the necessity of self-defense. He feared that a preemptive strike by the Schmalkaldic League might prompt the emperor to “exert all his might” and the combined forces of the papacy, Portugal, France, and the German Catholic states against the Lutheran princes. Sturm's argument carried the day. Tensions remained high, though these were mitigated by a series of colloquies convened between 1539 and 1541 at the instigation of the neutrals and the Catholic peace party (including the electors of Mainz, Brandenburg, and the Palatinate). Despite opposition from Catholic hawks (Duke Henry of Braunschweig-Lüneburg and Bavarian Dukes William IV and Louis X), the colloquies extended the Truce of Frankfurt.Footnote 38

In the wake of the October 1538 imperial ban upon the city of Minden, a Schmalkaldic League member, Luther signed yet another formal opinion drafted by Melanchthon. However, rather than providing the elector with theological justification supporting the right to resist the emperor, or even a rationale based upon constitutional or private law, it offered only a legal interpretation taken from the natural law of self-defense. The responsibility of princes to protect their subjects was akin to the natural right of fathers to defend their families against a private murderer or even a tyrannical emperor who “imposed, outside of his office, unjust force and especially public or notorious unjust force” by murdering them outright or by compelling them to worship idols and to adopt the Mass. “For public violence annuls all obligations between subjects and their ruler according to natural law.” If an enemy were to announce a declaration of war publicly, an offensive defense might be possible, but the princes, rather than the theologians, would have to make this decision. Before the situation reached the boiling point, however, earnest prayers for peace should be offered to God.Footnote 39

In his writings of 1539, Luther elaborated further upon a concept that he had developed as early as 1519, the three estates through which God governs the world, which intersect in complex ways with the two kingdoms. Though initially based upon the medieval complementary orders of clergy (oratores), nobility (bellatores), and peasantry (agricultores), or their social counterparts, the ecclesiastical estate (ecclesia), political estate (politia), and the economic estate of the household (oeconomia), Luther's thought continued to evolve. First, he leveled the playing field of the priestly and monastic clergy through the priesthood of the believer and then stressed the ministers of the Word over the priesthood. He expanded the politia, made necessary by the Fall and the need to protect the righteous and punish the wicked, from the nobility to include every subject of the state. And he broke oeconomia down into the household and marriage along with the family, protected under the fourth commandment. All three estates were equal in dignity and derived from scripture; each provided guidance for essential social relationships, namely, church membership or clergy, citizenship, and kinship. The ecclesia, however, mirrored the two kingdoms in the sense that Luther, following Augustine in the City of God, envisioned both spiritual and temporal churches. Christ alone ruled over the former, and the preaching of the Word and administration of the sacraments linked it with the visible church on earth. So while the earthly church was related to the spiritual kingdom, the two were by no means synonymous. Luther also rejected theocracy, though the earthly, external church often intersected with the other two estates, household (oeconomia) and state (politia). Finally, since God's presence could be found in all three estates, no clear distinction existed between secular and sacred. Rather, humans participate in a variety of social contexts sanctioned by God. Nevertheless, tensions in his thought remained.Footnote 40

Luther expounded further upon the complex relationship between the two kingdoms and the three estates in On the Councils and the Church (completed mid-March 1539). In Augustinian fashion, Luther defined the church not as a building or as governed by a hierarchy of Roman pontiffs and church councils, but rather, as the community of “holy Christian people” who believe in Christ. From this group were excluded popes, bishops, priests, and monks who neither “believe in Christ, nor . . . lead a holy life, but are rather the wicked and shameful people of the devil.” The church provides sanctification to believers in ways that reflect the two kingdoms. Through the Holy Spirit, believers are sanctified inwardly “according to the first table of Moses,” while through “outward signs that identify the Christian church . . . the Holy Spirit sanctifies us according to the second table of Moses.” The church stands in grievous need of reform, a return to its roots as an apostolic church focused upon Christ and his Word, yet the papacy and church councils have proved incapable of accomplishing this. Why, then, should the “blasphemous” papacy be given the task of overseeing the three estates? “[T]here are only two temporal governments on earth, that of the city and that of the home . . . . The first government is that of the home, from which the people come; the second is that of the city, meaning the country, the people, princes and lords, which we call the secular government. These embrace everything . . . . Then follows the third, God's own home and city, that is, the church, which must obtain people from the home and protection and defense from the city. These are the three hierarchies ordained by God, and we need no more; indeed, we have enough and more than enough to do in living aright and resisting the devil in these three.”Footnote 41 Thus by early 1539 Luther had rejected the Roman papacy and its government as lying outside of God's two kingdoms and three estates, as having no place either in God's creation or in the true church. Rather, the papacy lay within the devil's realm, awaiting the apocalyptic doom that was certain to be its fate.

The Circular Disputation on the Right of Resistance against the Emperor (Matthew 19:21) (February–May 1539)

Luther soon took his apocryphal understanding of the Roman pontiff as the Antichrist in new directions. On February 8, 1539, Luther sent Johann Ludicke, a preacher of the city of Kottbus who likely had written Luther on behalf of Elector Joachim II of Brandenburg, a formal statement of his position on whether the Protestant German princes might resist the emperor lawfully. Lamenting in his letter to Ludicke that the princes had decided to move forward even without his support, notwithstanding the fact that he was praying that God might yet intervene to convince the emperor to stay his hand, Luther confessed that he had the “gravest concerns.” In place of his earlier understanding of the emperor as autonomous, he now recognized that resistance against Charles could be justified lawfully by the German princes since, no longer ruling as emperor in his own right, Charles was serving as a soldier, even as a mercenary, of a pope (militem et latronem papae) who was falsely and unlawfully claiming to be acting on behalf of Christ even as he persecuted Christians. Further, the deception of the pontiff, cardinals, and bishops, joined now by the emperor, made these “slaves of Satan” (mancipia Satanae) even more evil than the Turks. While Romans 13 commanded that one must suffer under pagan tyrants, Luther's response to a diabolical, pseudo-Christian tyrant who had usurped the name of Christ in order to overturn the divine order was to execute God's judgment and let the offenders bear the “penalty of Cain” and the full punishment found in Hebrew law for blasphemy and idolatry committed in violation of the second commandment. Taken together, Luther's and Philip of Hesse's arguments denied Charles V's legitimacy and supported resistance against his forces on theological as well as constitutional grounds. In An Admonition to All Pastors (ca. March 1539) and in a sermon and his table talk from this same period, Luther repeated these arguments, but expressed his hope that God would enable both sides to avert war before they destroyed each other and achieve peace through repentance and prayer. Still, he questioned the wisdom, even if justifiable, of resisting imperial authority.Footnote 42

During this critical period, Luther arguably offered his most radical support for resistance against the combined imperial, papal, and German Catholic forces threatening the Lutheran states. As he was preparing a set of theses in April 1539 for the upcoming Circular Disputation on the Right of Resistance against the Emperor (Matthew 19:21), a debate to be held at the University of Wittenberg, the threat of war between Catholics and Lutherans in Germany loomed on the horizon, oddly, even as peace negotiations at the colloquies continued. On March 15, Luther received word of “papists, who conscripted soldiers to attack the evangelicals in Bohemia and who have assembled military forces under alien leadership in Braunschweig.”Footnote 43 The Frankfurter Anstand that the emperor and princes would sign on April 19, 1539, reaffirming the Nürnberg Anstand of 1532, still lay in the future and even then would merely temporarily and only partially defuse the existing friction and the very real possibility of a Catholic attack.Footnote 44 In response to the heightened tensions and the growing likelihood of an invasion by imperial Catholic forces, in early 1539 Luther prepared his theses, once again without violating either his conscience or his understanding of Romans 13.Footnote 45 Theses 1–50 restate Luther's earlier theological position that an individual Christian is forbidden to resist a divinely ordained secular authority, even if the ruler persecutes his subjects for the sake of Christ. The sovereign, who alone is authorized to make statutes or command private troops, seeks peace among his subjects. Thus the Christian subject must obey a pagan or even an impious Christian magistrate, for they “are not against us, but with us and for us in accord with the second table,” which addresses how the faithful should live in relation to one another in the earthly life (theses 36–40). Even if a magistrate persecutes his subjects for the sake of the faith in violation of the first table, his subjects must not resist or overthrow that magistrate and the political institutions ordained by God through their own imprudence (theses 45–50). Here Luther maintains the hierarchical relationship between divinely ordained superior secular authority and the Christian subject found in Romans 13.Footnote 46

In the last twenty theses of his draft (theses 51–70), Luther introduced and built upon the new elements of his argument in his letter to Pastor Ludicke and his treatise On the Councils and the Church.Footnote 47 With thesis 51, Luther shifted his attention to the pontiff, who is not a magistrate, neither ecclesiastical nor civil nor familial, thus not one to whom obedience is commanded in Romans 13; neither does he belong to the three hierarchies, or estates, ordained by God against the devil, namely, the household, the civil state, and the church (oeconomia, politia, et ecclesia). He has denied the church's existence, “damned the gospel, and trampled it underfoot through his blasphemies in canon law.” He has undercut the secular state by subverting the civil laws even as he has done with the gospel. He has undermined the family by prohibiting marriages “not only to priests, but to whomever he pleases” (theses 51–55). Citing the apostle Paul and the book of Daniel, Luther describes the pope in apocalyptic terms as the “adversary of God, a man of sin, the son of perdition”—a Beerwolff (werewolf) possessed by a demon that must be hunted down and destroyed by the people of the entire countryside, “every town and village, each and every man,” no matter how futile the struggle appears, because the Beerwolff consumes everything in his path (theses 56–60). “Thus if the pope should wage war,” Luther wrote, “he must be resisted as if he were a furious and possessed monster, or truly a Beerwolff, for he is neither a bishop nor a heretic nor a prince nor a tyrant, but a beast who ravages everything [vastatrix omnium belua], as Daniel declares” (theses 66–67). Neither should one be concerned if the beast has as soldiers, princes, kings, or even emperors themselves who have been bewitched [incantatos] by a church title. Nevertheless, “whoever serves as a soldier under his mercenary [sub latronem] . . . should expect the perils of his military service along with eternal damnation” (theses 68–69). “Nor would claiming to be defenders of the church save kings, princes, or emperors since they ought to know what the church is” (thesis 70).Footnote 48

During the disputation itself, Luther again characterized the pope as a monster (monstrum/ungehewer Thier) rather than as a magistrate, the devil incarnate (incarnatus diabolus/Teufel) who must be resisted at all costs because he wants Christians to subject themselves to his blasphemies and thereby cast their souls into hell. If the emperor and princes fail to take action against this blasphemous pope, then everyone (singuli et omnes) should oppose and strike down the monstrous pontiff and those defending him and avenge his blasphemies by an actio popularis and sedition. The jurists argued that the electors were the equals of the emperor, with obligations to the Holy Roman Empire as well as to Charles V, and that as such they were lawfully empowered to resist him as a legal body. At the same time, since the emperor (as a papisticus) desired “to defend those horrendous blasphemies of the pope,” the princes and even the people themselves were obligated to “defend the Word against that newest monster.” Subjects should be ready to suffer and even to give up their physical lives to a pagan emperor because of their faith as Christian martyrs had done under Diocletian, but no emperor had a legitimate claim to their souls. Above all, Christian princes should resist a tyrant seeking to eradicate their doctrine, for they were “obligated to leave a pure gospel to their descendants in accordance with the first table,” which should always take precedence over the second table. If, in the end, war should break out, the Lutheran princes would be fighting as equals against the robbers, Charles and Ferdinand, who were seeking their possessions “under the pretext of the pope.”Footnote 49 As Martin Brecht observes,

During the disputation Luther several times emphasized anew that the conflict with the pope was of an exceptional sort and therefore required corresponding action. . . . The Christian right of resistance, as Luther now taught it, applied only in an extreme emergency in which salvation was at stake because of totalitarian claims. . . . Luther, however, was not thinking about resisting the emperor, whose injustices he would tolerate if necessary; instead, he was denying the power of the pope because the pope could not be an authority at all and certainly not a tyrant. His explanation of the right to resistance owes its force to this more pointed argumentation, and in it Luther set aside his own constantly recurring reservations.Footnote 50

The physical danger was palpable, yet so, too, was Luther's determination in Petrine fashion to “obey God rather than men” (Acts 5:29). True, Luther had gone farther than ever before by extending to the masses a call, if attacked, to resist the pope as the Beerwolff or the vastatrix omnium belua in the book of Daniel. By viewing the approaching conflict in apocalyptic terms and acknowledging that the German princes could lawfully resist the emperor and defend their subjects against bloodshed and the theft of their lands and possessions if their territories were attacked by imperial forces under false pretenses or if the gospel were threatened with eclipse in their lands by imperial forces acting on behalf of the pope, Luther had moved from a position arguing against any resistance to the emperor beyond nonviolent disobedience to one that sanctioned defensive military action against imperial forces, albeit only under very specific circumstances. If the emperor was an elected official who shared power with his electors or was proceeding as a private person inflicting notorious injury, or if he was serving as an agent of the pope or even acting on his own to proscribe the Lutheran faith, the princes could resist him without violating canon, civil, natural, imperial, or divine law. If they failed to do so, since Charles was a mercenary of the Antichrist Beerwolff, the people themselves should rise up because their eternal souls and the survival of the true gospel would be at stake. In this context, neither pope nor emperor could be considered “legitimate” superior authorities.Footnote 51

In the end, Luther failed to approve the preemptive strike by the Schmalkaldic League that Elector Johann Friedrich and Landgrave Philip would have preferred. The Frankfurter Anstand was renewed in April 1539 and multiple times subsequently until after Luther's death. Also that same year, Luther published his Lectures on the Song of Solomon (1539), originally delivered between March 1530 and June 1531, but now accompanied by a timely new preface that put forth Luther's bold, original interpretation. Solomon's “encomium of the political order,” his defense of secular political government in the “Song of Songs,” “honors God with his praises; he gives Him thanks for his divinely established and confirmed kingdom and government; he prays for the preservation and extension of this his kingdom, and at the same time he encourages the inhabitants and citizens of his realm to be of good cheer in their trials and adversities and to trust in God, who is always ready to defend and rescue those who call upon Him.” King Solomon, Luther observed, praises the peace and tranquility achieved by divinely sanctioned governments that rule justly and whose subjects willingly obey their commands. Rather than trusting in riches, human wisdom, and man-made defenses, godly governments place their faith in God and turn to him as a refuge in times of danger, believing that he will never desert his people in their hour of need. “And so from this Song of Songs, which Solomon sang about only his own state, there springs as it were a common song for all states which are ‘the people of God,’ that is, which possess the Word of God and worship reverently, which acknowledge and truly believe that the power of governments is established and ordained by God and that through this power God preserves peace, justice, and discipline.” Thus Solomon's Song of Songs “does not treat a story of an individual,” but rather, that of “an entire permanent kingdom, or people, in which God untiringly performs a host of staggering miracles and displays His power by preserving and defending it against all the assaults of the devil and the world.”Footnote 52 Seeing God stay the hand of their opponents, Luther thus had returned to a call for prayer, patience, and, if necessary, nonviolent disobedience.

Luther's Late Thought on Resisting the Emperor, 1540–1546

Luther continued to address whether one might lawfully resist superior authorities until his very last sermon, preached just days before his death in 1546. In a separate treatise, entitled Appeal for Prayer against the Turks (1541), Luther succinctly summed up his strategy for dealing with an errant temporal lord, namely, to pray and to trust in the Lord for deliverance: “Our confidence lies in this, that God the Father of all mercies is our righteous judge and a wrathful avenger against all the devils, the Turks, Muhammad, [and] the pope . . . . As Christ says in Luke 18[:7–8], ‘And will not God vindicate his elect who cry to him day and night? . . . I tell you he will vindicate them speedily.’” Rather than trusting in man-made defenses, weaponry, or shrewd planning, Christians should turn to God and pray for deliverance against the demonic forces of the Turks.Footnote 53

That same year (1541) Luther replied to an inflammatory essay written by Duke Henry the Younger of Braunschweig, who in 1538 had joined the militant Catholic League of Nürnberg, which included the forces of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, Austrian Archduke and Bohemian King Ferdinand I, the Elector of Mainz, the archbishop of Salzburg, the Duke of Braunschweig-Lüneburg and Prince of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel (Henry the Younger), and Dukes William IV and Louis X, co-regents of Bavaria. Hated by the Protestant princes and accused of arson, adultery, murder, and tyranny, Duke Henry wrote a Rejoinder against the Elector of Saxony (1540) in which he referred to Elector Johann Friedrich as “Hanswurst,” a comical literary character of that day often portrayed in clown costume with a Wurst wrapped around his neck. In his response, Against Hanswurst (1541), Luther turned the tables by applying the image to Duke Henry himself. Here, Luther insisted, “[N]obody can deny that with the ancient church we hold and teach that one should honor and not curse the temporal powers and should not compel them to kiss the pope's feet. . . . For we have always most faithfully taught obedience to our temporal authority, be it emperor or princes. We ourselves have lived accordingly and prayed for them with all our heart.” Thus, even in 1541 Luther still denied that his position toward honoring superior secular authority had ever changed. Errant dukes such as “Harry” remained accountable to God, even if they enjoyed the support of the emperor and pope. The latter were obligated by godly law to rule with justice, so if they violated divine sanctions and persecuted the gospel, their subjects were not compelled to obey them. Further, the emperor was not to infringe upon the first table by imposing Catholicism, for his jurisdiction lay within the second table.Footnote 54 Here Luther might have been accused of imposing one standard for the emperor and another for the German princes upon whom he had called to defend the evangelical faith, yet Luther always charged the pious Christian ruler with promoting the faith through servanthood and prayer rather than by persecution and bloodshed.

The problem posed by Duke Henry's actions and his support of the papacy grew more complex. Duke Henry had assumed command of the Catholic forces in northern Germany, but he was driven into exile in July 1542 by the Protestant forces of Hesse and Electoral Saxony. Eike Wolgast observes, “Luther . . . accepted the electoral justification for the [1542] attack as fulfillment of a duty of assistance. . . . However, he did not face up to the fundamental questions of the Braunschweig War, the violent extension of the Reformation to another territory and the expulsion of a legitimate authority by a body not authorized to do so under imperial law.”Footnote 55 Wolgast's point is well taken, for even though by now Luther had accepted that imperial law rendered the sovereign princes the equals of the emperor and had found a “legitimate” justification to resist an “illegitimate” emperor trying to reimpose Catholicism in Lutheran territories, here his actions suggest that he was taking advantage of the political and military situation to expand the Lutheran faith even though at the time he no doubt also believed he was eliminating a serious Catholic foe.

In the fall of 1545, Henry retook his former territory and briefly reimposed Catholicism until the landgrave and elector outmaneuvered his forces, capturing the duke with his eldest son. The question now was what to do with him. At the elector's request, Luther penned yet another powerful response, To the Saxon Princes: To the Elector of Saxony and the Landgrave of Hesse on the Captive Duke of Braunschweig (1545). Writing late in life amidst a resurgence of Catholic political power, Luther argued strongly against Duke Henry's release, for if he were set free, he would only return to his throne and pressure the Lutheran territories from the north. Luther reminded the princes that they needed to focus their attention not so much upon the fate of the Duke of Braunschweig as upon the “whole of the Behemoth and body of the papacy, which has attached itself to him . . . . It is this alliance with the pope—for which God has seized Braunschweig and taken him prisoner as his enemy and as the servant of the pope—which will not allow any possibility of his being set free so lightly.” The unresolved question, as in 1542, was in regard to princely claims of Henry to the Duchy of Braunschweig versus the persecution he stood accused of perpetrating upon his subjects, who had no right to overthrow their temporal ruler. Tyranny aside, would the Lutheran princes allow Duke Henry and the members of the League of Nürnberg to reinstate “idolatry, blasphemy, and error” in Braunschweig's Lutheran churches and homes? Luther's response focused upon Divine Providence, which had enabled the Protestant forces to capture and imprison Duke Henry. The Protestants should not “boast of this victory, but give the honor to God and thank and praise him who alone is the true warrior,” for the “victory is his gift, and not a result of our might or cleverness.” Luther supported a military solution to the princes’ dilemma only if instituted by God Himself as divine punishment for the duke's tyrannical rule. “Whoever relies and presumes on his arms, cleverness, and strength, . . . scorns God,” he wrote. In the revised edition of 1546, Luther appended Psalm 64, the psalmist's plea for preservation against an enemy plotting evil and seeking to ambush him, at whom God will shoot deadly arrows. He also cited Psalm 76 and called for thanks to God for protecting the Lutherans “from the papists’ evil purpose” and for having “put them to confusion.” Here Luther foresaw imminent danger, for even as the Roman Catholic clergy had been drawn by Satan into politics, so too the papacy was now drawing some German princes, among them Duke Moritz of Albertine Saxony, into the religious domain that properly belonged to the clergy.Footnote 56

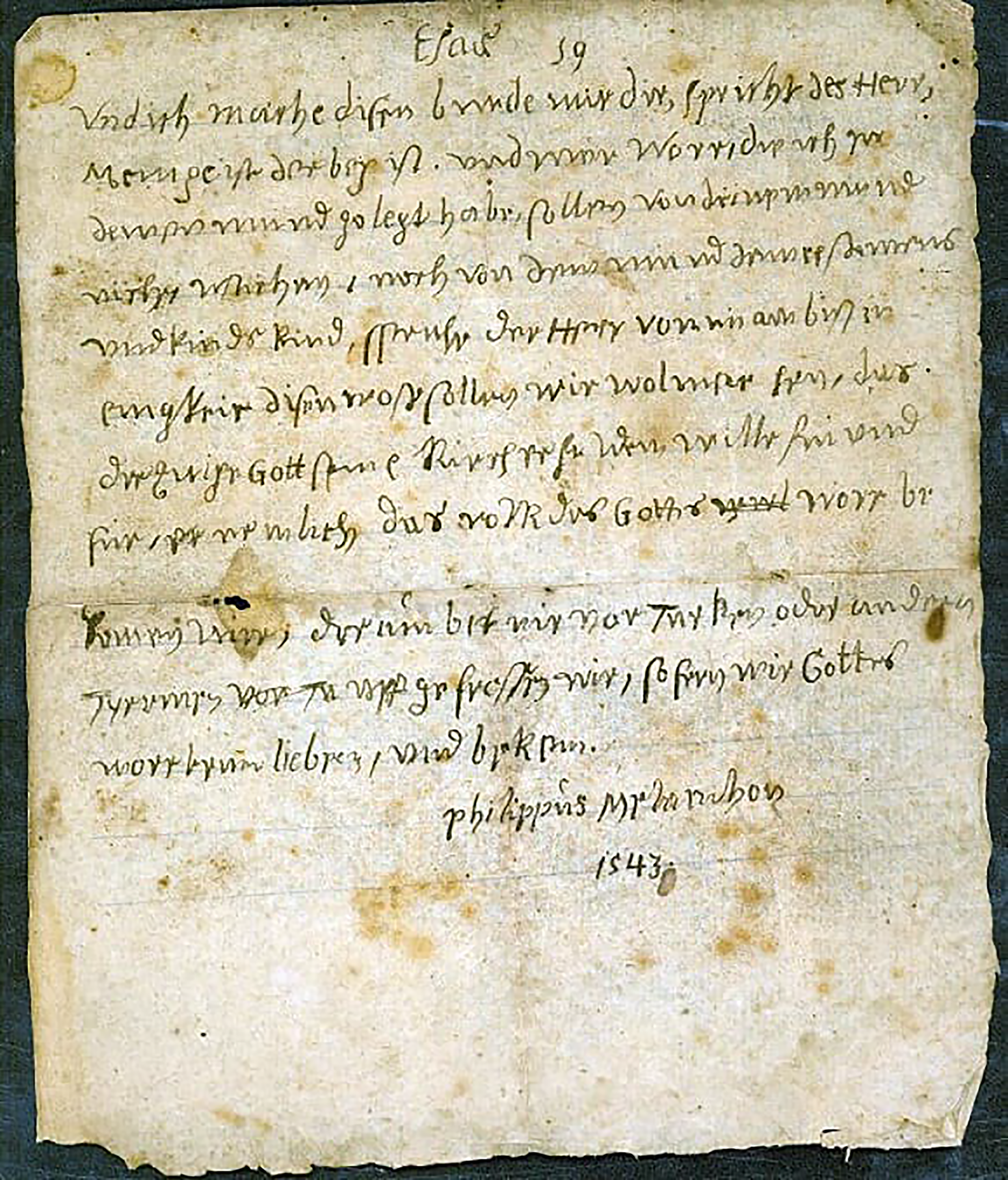

Time and again, in the final years of his life, Luther stressed prayer and trust in God over war against imperial forces. One might reason here that, with the repeated renewal of the Frankfurter Anstand, the crisis was less pressing and so Luther could afford a more cautious approach, but the Turkish threat erupted once more in the early 1540s. An autograph of a brief commentary on Isaiah 59:21, in Melanchthon's hand and dated “1543” (figure 1), strove to reassure German Lutherans: “We should hold dear this comfort that the eternal God desires to preserve his church forever and ever, namely, the people who will profess God's Word; for this reason, it [i.e., the church] will never be devoured by the Turks or other tyrants, as long as we learn, love, and profess the Word of God.” Although the pressing danger from the Turks must have lessened the likelihood of an invasion by imperial forces, Melanchthon nevertheless alluded to the danger of the extermination of the church by “other tyrants” such as Duke Henry and the emperor.Footnote 57 That same year Luther and Johannes Bugenhagen published an Admonition to the Pastors in the Superintendancy of the Church at Wittenberg (1543), urging pastors to call upon their congregations to repent and pray for deliverance from the Turks. Two years earlier Luther had published the Appeal for Prayer against the Turks in which, assuming the role of the prophet, he had chastised the Germans for their sins, called upon them to repent, and prophesied the coming apocalyptic war with the Turk, the beast of Revelation, followed by the Final Judgment.Footnote 58

Figure 1 Exposition on Isaiah 59:21 by Philipp Melanchthon, 1543, R. D. Livingston Autograph Collection, B. H. Carroll Center for Baptist Heritage and Mission, Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, Fort Worth, Texas. Reproduced by permission.

Luther, meanwhile, never relented with regard to his position toward the papacy. With the Recess of the Diet of Speyer in June 1544, Charles V, seeking peace and an end to the religious divisions that plagued his lands, in theory agreed for a free general council to be convened in Germany to resolve their religious differences. Pope Paul III had summoned a council first to Mantua and then to Vicenza in 1537–1538 before postponing it indefinitely in 1539. Since it was not clear when this council might actually meet—the council would not convene at Trent until December 1545—another meeting of the diet to seek a religious compromise overseen by the emperor was planned for the fall or winter of 1544–1545. Charles also renewed the Frankfurter Anstand yet again even as he put off prosecutions of Protestants at the Imperial Cameral Tribunal. Upon learning of this, an outraged Pope Paul III sent a letter to Charles in which the pontiff took the emperor to task and demanded that he retract the assurances that he had given to the German Lutherans. The emperor should not attempt either to judge or negotiate their religious differences during the interim, for only the pope and officials of the Roman Curia were authorized to do this. The council would indeed take place, the pontiff insisted privately, but the “heretics” would have no voice in its proceedings. But Luther had his allies and spies, so somehow the papal letter plus a more vehement earlier draft soon came into his hands. In an angry response, Luther penned perhaps his most venomous treatise, Against the Roman Papacy, an Institution of the Devil, which was published in late March 1545, along with eight caricatures of the papacy by Lucas Cranach.Footnote 59

In this treatise, Luther utilized historical examples, logic, and scripture to demonstrate that the pontiff was neither the head of Christendom nor a world monarch. Nor was he above judgment or being removed from his office. The Council of Constance (1414–1418), seeking to end the Great Schism of the Western Church (1378–1417), had deposed two of the three reigning popes, John XXIII and Benedict XIII (though he refused to accept the council's action), and had accepted the resignation of the third, Gregory XII, demonstrating that the council was indeed above the pope, even if papal monarchs from Martin V forward had worked to reverse this teaching. Luther argued that the papacy had never been ordained with either secular or spiritual authority, and since these two realms, the secular and the spiritual, were the only ones sanctioned by God on earth, the papacy must have originated with the devil. Hence the pontiff could not possibly be Christ's vicar. Luther concluded in language reminiscent of his theses of 1539: “[T]he pope . . . is the head of the accursed church of all the worst scoundrels on earth, a vicar of the devil, an enemy of God, an adversary of Christ, a destroyer of Christ's churches . . . an Antichrist, a man of sin and child of perdition; a true werewolf.” Here was a diabolical monster, condemned by God, with no place in either the two kingdoms or the three estates. Thus, sovereigns were freed from their oaths to the pope and were “duty-bound” to oppose him.Footnote 60

One last text, this from Luther's final sermon preached at Eisleben on February 15, 1546, just a few days before his death, confirms that his position toward legitimate superior authority had never changed. Here he addressed the problem of obedience owed to a pope who “puffs himself up” and says that he cannot err, as well as to “jackanape” and “wiseacre” temporal rulers, who think themselves wise but who are, in fact, fools “because they want to make themselves masters of his divine Word and with their own wisdom rule in the high, great matters of faith and our salvation.” Christ will not tolerate them in his church, no matter how lofty their titles, because they place their own judgments above the Word in matters of faith. Their subjects should obey them in temporal affairs, but in matters of religious faith, they should refuse to conform whenever their sovereign's commands violate divine law or if they attempt to coerce their subjects’ religion. Never should they undertake what not even an angel in heaven dared, namely, to “take over sovereignty” and presume to “rule in God's government.” Instead, they should be prepared to suffer their ruler's wrath, excommunication, and even being burned or beheaded. As Luther explained (quoting Mathew 11:28), “[I]t is as though he [Christ] were saying: ‘Just stick to me, hold on to my Word and let everything else go. . . . Only come to me; and if you are facing oppression, death, or torture, because the pope, the Turk, and emperor are attacking you, do not be afraid . . . . For when you suffer for my sake, it is my yoke and my burden.’”Footnote 61 No matter their misfortune, if only they would keep the faith and wait upon the Lord, they would win eternal life and achieve victory over Satan and the world. As in 1523, at the time of his death in 1546 Luther held that subjects were duty bound to follow their conscience if their legitimate superior attempted to mandate adherence to a particular faith, but in no way were they to resist him by force. Rather, subjects of all ranks were bound to obey their temporal superiors, honor their oaths to them, and trust that God would set things aright should their superior persecute them for their religious faith.

The Reception and Development of Lutheran Resistance Theory by the Magdeburg Theorists, 1547–1551

The political developments and military escalation that took place in Germany shortly after Luther's death need only be summarized briefly here. Emperor Charles V and Pope Paul III signed a joint agreement in the summer of 1546 according to which Charles pledged to “prepare himself for war, and equip himself with soldiers and everything pertaining to warfare against those who objected to the Council [of Trent], against the Smalcaldic League, and against all who were addicted to the false belief and error in Germany, and that he do so with all his power and might, in order to bring them back to the old faith and to the obedience of the Holy See.”Footnote 62 Duke Moritz of Albertine Saxony reversed allegiance, siding with Charles in return for the promise of being awarded Electoral Saxony once Johann Friedrich was defeated. With Philip of Hesse and Johann Friedrich under imperial ban for having deposed Duke Henry of Braunschweig, tensions simmered until April 24, 1547, when the superior numbers of Charles V's army, benefitting from the element of surprise, defeated the Schmalkaldic League's forces at Mühlberg and captured Johann Friedrich in the process. Philip of Hesse surrendered shortly afterward.Footnote 63

In 1546–1547, the Schmalkaldic League argued that Charles V exceeded his constitutional authority in attempting to reimpose papal obedience and Catholic doctrine in the Lutheran territories. Following the Protestant defeat at Mühlberg, however, the League's members could ill afford to oppose the emperor. Nevertheless, the city of Magdeburg sought to walk a fine line as its councilmen and pastors hastened to reaffirm their loyalty to the emperor in secular matters even as they also confessed that they could never sanction the reinstatement of Catholicism within their city. Echoing the words of Peter and the apostles in Acts 5, they insisted that they must obey God rather than men. This was hardly a coincidence. Not only had Martin Luther quoted Peter's words here on multiple occasions, but just a short time prior, in his Confession of Our Religion, Teaching, and Faith (ca. 1540–1542), addressed to Landgrave Philip and the Hessian theologians, the Hutterite Anabaptist missionary Peter Riedemann (1506–1556) had quoted these same words in justifying the presence of Hutterites in Hesse (in stark contrast to the notoriously radical Münster Anabaptists in Westphalia) as a peaceful and law-abiding, yet separate religious community, labeled as “conforming nonconformists” or “obedient heretics” by recent historians. Moreover, in 1545 the Hutterites sent Riedemann's Confession to the Diet of Moravia (ruled by the Crown of Bohemia) to help its members understand the beliefs of the Hutterites they were being asked to protect from the forces of Austrian Archduke Ferdinand I. Riedemann's argument paralleled that of the History and Tale of the Recent Occurrences in the Worthy Kingdom of Bohemia (1546), which clarified why the Protestant Bohemian Crown Lands, including Moravia, had refused to go to war against Electoral Saxony, again insisting, “We should obey God rather than men.” Both of these texts and narratives thus would have been well known to the leaders at Magdeburg.Footnote 64

In April 1548, Charles imposed the Augsburg Interim, an imperial decree ordering the Lutherans to restore the seven sacraments, reinstate the Catholic Mass and transubstantiation, recognize the pope as head of the universal church, and subject themselves to the authority of their Catholic bishops. As concessions, clerical marriages were to be recognized and the eucharist distributed to the laity in both kinds (bread and wine). After Melanchthon and the “Adiaphorist” theologians at Wittenberg accepted the Interim, the Flacians or Gnesio–Lutherans, strict adherents to Lutheran doctrine, fled to the city of Magdeburg, which, though under imperial ban, became the final refuge and point of opposition to the demands of Charles V, the papists, and the Adiaphorists. Bishop Nicolaus von Amsdorff of Naumburg (appointed Superintendent of Magdeburg), Nicolaus Gallus [Hahn] of Regensburg (now pastor of St. Ulrich's Church), Matthias Flacius “Illyricus” of Wittenberg, and the pastors and councilmen at Magdeburg refused to accept Archbishop-Elect Johann Albrecht and swore an oath to resist the imperial mandate and restoration of “idolatry.”Footnote 65