Introduction

‘The subject of “nasal douches and sprays” possesses only a mild interest for the experienced rhinologist, because he has long ago settled in his mind the relative value of these measures, and has dismissed them from the realm of things to be considered. This, however, does not mean that rhinologists are united in sentiment in regard to them, but it is because their individual experience with them has been so large that arguments have little influence’.Reference Wright1

This statement, written in 1893 by the American rhinologist Jonathan Wright, is mostly still true today. However, there are many ways to perform nasal lavage, and their relative efficacies are not so well established that which method to choose should indeed be outside the realm of things to be considered. Finding the best method of delivering fluid into the nasal cavity is still a matter of constant discussion, despite this treatment being a conceptually simple but indispensable tool used effectively by patients for centuries.

Nasal lavage uses the shear force generated by a liquid being flushed through a nozzle to wash mucus and detach crusts from the nasal mucosa. Additionally, it enhances mucociliary clearance and reduces the concentration of inflammatory mediators.Reference Bastier, Lechot, Bordenave, Durand and de Gabory2

Despite its widespread use, there is no current consensus regarding which irrigation method is preferable and which device delivers the best clinical results.Reference Bastier, Lechot, Bordenave, Durand and de Gabory2 For instance, syringe administration has fundamental shortcomings, such as low output pressure and low volume, yet it remains a very popular method. On the other hand, squeeze bottles are currently the method of rinsing recommended most commonly by otolaryngologists, but the limitation of a relatively small volume persists, with additional concerns such as bottle contamination caused by reversed flow.Reference Nguyen, Camilon and Schlosser3–Reference Foreman and Wormald5

From simple pots used in Ayurvedic medicine to modern electrically powered models, we will re-examine various types of devices, evaluating the advantages and disadvantages of each. By doing so, we hope a broader view can be achieved on what is currently possible with nasal lavage and how advances may be made in the future.

Ancient account of nasal rinsing

Ayurveda

The Neti pot, described in the Ayurveda, was the first nasal rinsing device. This ceramic pot has been used in Hatha Yoga for thousands of years for Jala Neti (purification with water).Reference Rama, Ballentine and Hymes6,Reference Jefferson7 However, the practice of nasal lavage was encouraged for spiritual and hygienic reasons, rather than for the treatment of sinonasal conditions. It was not until 2007, when the American celebrity physician Dr Mehmet Oz appeared on The Oprah Winfrey Show and demonstrated the device, that the Neti pot started to be widely used in Western societies for nasal conditions.Reference Ho, Cady and Robles8

However, currently, there is no evidence that shows a clear clinical benefit of the Neti pot over other lavage systems. For many patients, it is seen as a good option because it is simple to use and inexpensive. Gravity provides the flow, so the sheer force on the mucosa is limited. For some patients, the gentleness of the Neti pot is advantageous as the Eustachian tube orifice closing pressure is not exceeded.

Greek and Roman lavage techniques

Greek and Roman medical literature described the use of syringes for rectal, vaginal, uterine, bladder, ear and sinus douches. A procedure named nasal clyster (nasal enema) is detailed by various Greek and Roman physicians.

Scribonius Largus called the apparatus he used a ‘horn’, to which a fluid-filled bag was attached. Aretaeus wrote about an aulos or tube for a nasal injection of euphorbium and other components, to evacuate phlegm in cases of chronic headache (‘kephalaia’). He describes how an injection is made through a nasal tube consisting of two pipes united by one outlet, so that both nostrils can be injected at one time. He argued that this mechanism prevented the discomfort derived from distention caused by the liquid if each nostril was injected separately. His description does not say whether the liquid was delivered via a bag or a syringe.Reference Bliquez9,Reference Milne10

Galen mentions a nasal syringe in his writings, but does not describe the device he used. Although Hippocrates gave instructions on how to treat nasal polyps, he did not recommend nasal lavage as a treatment for nasal conditions.Reference Leopold11

Dark and Middle Ages to Renaissance and Enlightenment

The progress made by Greek and Roman physicians was largely lost during the Dark and Middle Ages. During these times, bizarre functions were attributed to the sinuses, such as holding lubricant for the motion of the eyeballs, or permitting the brain to drain its malevolent spirits to the external world. The sinuses were termed ‘la cloaca del cerebro’ (the sewer of the nose) by a sixteenth century anatomist.Reference Cingi and Muluk12

The nose was believed to be the entry point for a number of diseases, including the plague. This idea was based on the miasmatic theory, where pestilence originated from invisible fumes that emanated from rotting corpses and contaminated soil or water.

It is, nonetheless, possible that nasal rinsing continued through this period, but it certainly was not considered an important part of the treatment for nasal conditions. However, in the sixteenth century, Petras Forestus claimed to have cured ozaena by ‘copious nasal douching with perfumed white wine in which cypress, roses, and myrrh were dissolved’. He also used silver nitrate and alum rubber mixed with honey, applied with a probe.Reference Cingi and Muluk12

Ivory and bone were used for syringes for aural and nasal use, mainly in the eighteenth century and early nineteenth century. The plunger was made of wood, with either linen or tow binding to provide a seal.Reference Bennion13

Nineteenth century

The eminent anatomist Emil Zuckerkandl (1849–1910) provided the first detailed and accurate description of the anatomical and developmental features of the nose and sinuses, opening this region to surgical and medical experimentation.Reference Cingi and Muluk12

In the light of his writings, nasal rinsing became an important therapeutic option for sinonasal disease. Johann Ludwig Wilhelm Thudichum (1829–1901) (Figure 1), a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of England and inventor of the famous nasal speculum, wrote a paper entitled ‘On a new mode of treating diseases of the cavity of the nose’, in 1864.Reference Thudichum14 This may be the first scientific publication to describe a specific technique for nasal rinsing using a device created for the purpose of treating conditions of the sinonasal cavity.

Fig. 1. Johann Ludwig Wilhelm Thudichum (1829–1901): inventor of the modern concept of nasal rinsing. Image courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.

Thudichum based his experiments and subsequent treatments both on the anatomical observations made by Zuckerkandl and on the experiments performed by German physician E H Weber, renowned for his studies of human physiology. Weber described how the soft palate closes against the choanae when breathing through the mouth, thus permitting the retention of fluid in the nasal cavity. He noted that the fluid which entered from one nostril was expelled through the contralateral nostril, as long as the individual kept breathing through the mouth.Reference Weber15

This observation provided the guidance for Thudichum to invent, with the help of the English medical instrument company Weiss & Son, two nasal lavage devices based on the principle of liquid propulsion by gravity. In the same year that Thudichum proposed his novel technique, the eminent French Professor Armand Trousseau published a paper in The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, where he explained that as part of the treatment for the chronic nasal condition ozaena, nasal rinsing should be performed with syringes.

After the concept of therapeutic nasal lavage was established, the race for creating nasal rinsing devices developed momentum. Numerous prototypes and designs were introduced to the market, with this process being accelerated by the burst of creativity associated with the industrial revolution. For the sake of clarity, we will classify the nasal rinsing devices according to their method for fluid propulsion (Table 1).

Table 1. Classification of nasal lavage systems

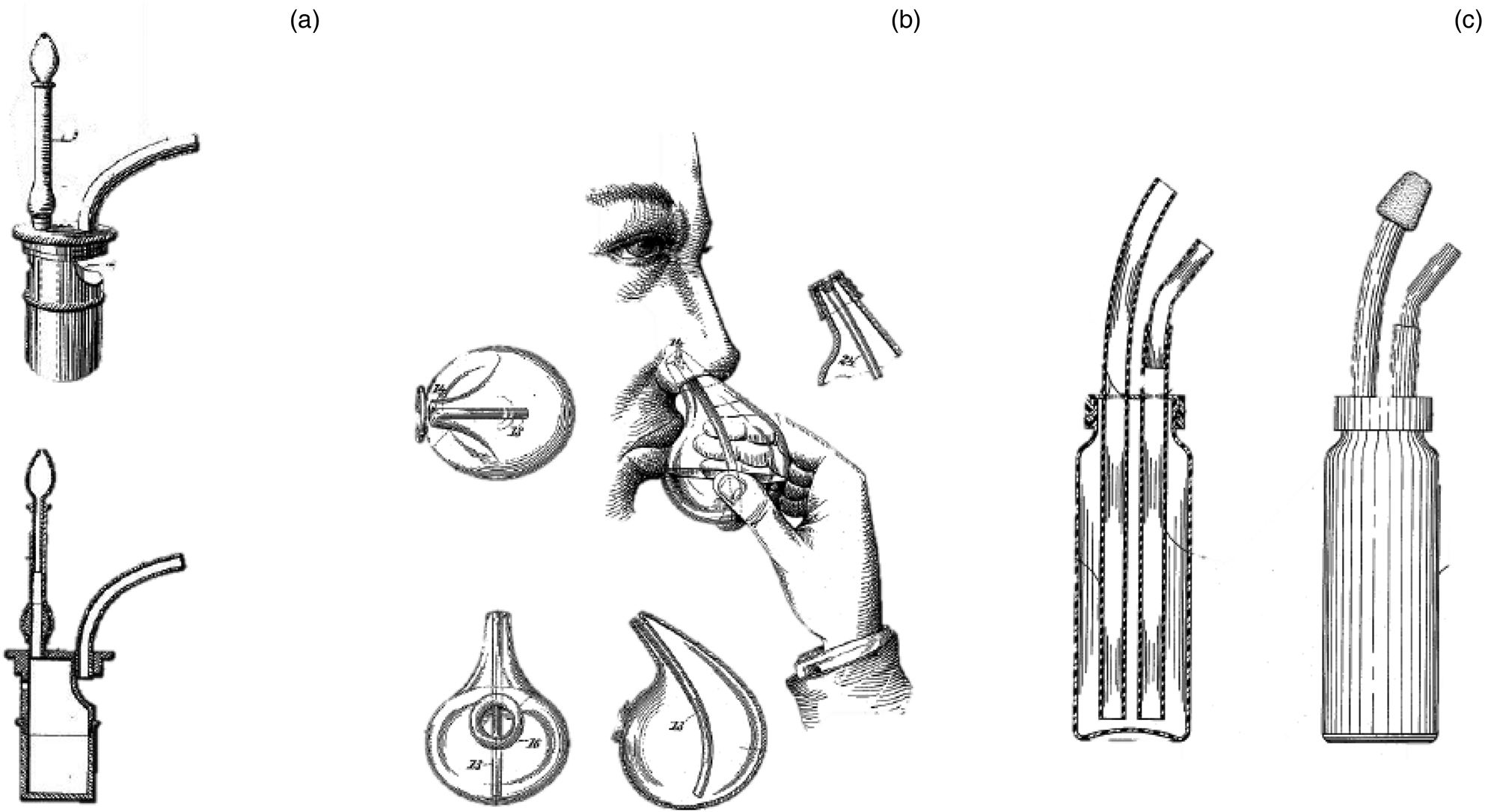

Syringes

Despite the emerging belief in the nineteenth century that larger volumes of fluid were desirable to achieve better clinical results, the utilisation of syringes continued and is still used by many today. This is mostly because of their valuable characteristics: ease of use, low costs and transportability. Models developed in the nineteenth century were usually made either from metal, hard rubber or glass, and some had interchangeable nozzles to achieve anterior or posterior lavage. Most syringes used a plunger mechanism (Figure 2a–d),16 but other models had an insufflator for propelling fluid (Figure 2e).17 A design from 1931 had a double nozzle, with one nozzle introducing liquid into the nasal cavity and the other draining it (Figure 2f).Reference Inaki18

Fig. 2. (a) Metal syringe with plunger and nozzle adapted for anterior nasal rinsing.17 (b) Glass nasal syringe.16 (c & d) Metal and black rubber syringes with nozzle for posterior nasal rinsing.17 (e) Syringe with insufflator for posterior nasal rinsing.17 (f) Bilateral nasal syringe.Reference Inaki18

Bottles

Flow by gravity

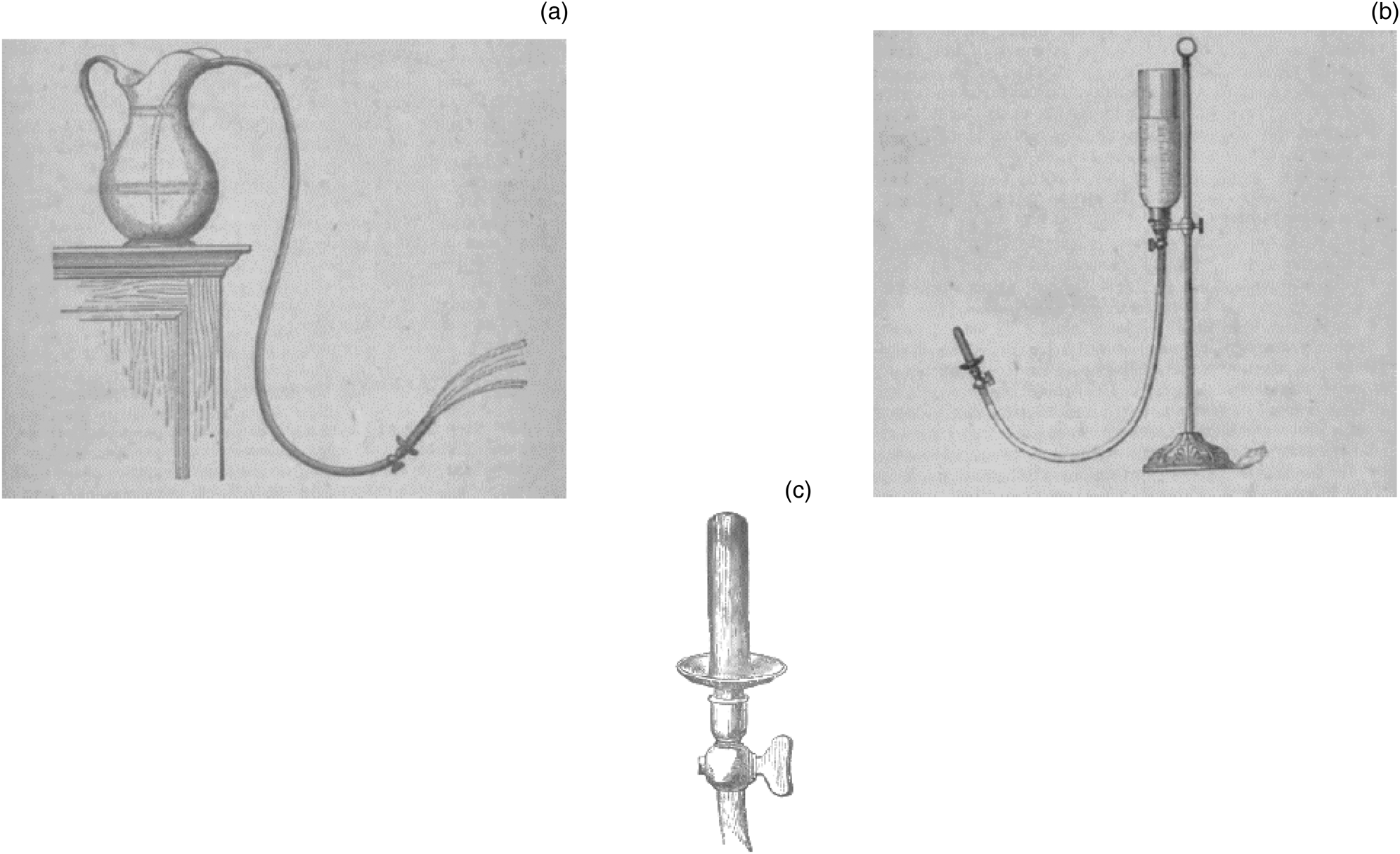

In order to achieve the principle of high volume and continuous flow, Thudichum described two prototypes in his book entitled ‘On Polypus in the Nose and Other Affections of the Nasal Cavity’.Reference Thudichum19 One prototype consisted of a ceramic jug in which a rubber tube was introduced, with a metallic plate in its distal end (Figure 3a). The liquid was initially drawn from the jug by mouth suction through the metallic nozzle, creating a syphon effect. His second model replaced the ceramic jug with an inverted glass bottle opened at the top (Figure 3b),Reference Thudichum19 to allow for greater flow.

Fig. 3. (a) First design by Thudichum with a ceramic jug, rubber tube and metallic nozzle. (b) Upgraded design by Thudichum, with inverted glass bottle opened and superiorly attached to a rubber tube and metallic nozzle. (c) Metallic nozzle with two-way valve to control flow rate.Reference Thudichum19

From this point on, many similar models were developed by other inventors, with containers made either from glass or metal (usually brass). The bottle could be held with one hand (Figure 4a)Reference Beard20 or positioned on a shelf higher than the head of the individual (Figure 4b).Reference Pierce21

Fig. 4. (a) Bottle held with one hand.Reference Beard20 (b) Bottle placed on a shelf higher than the patient's head, connected to a tube without a nozzle.Reference Pierce21 (c) Assisted nasal rinsing device with collapsible reservoir.Reference Davis and Douglass22 (d) Moyle's catarrhal douche.Reference Moyle23 (e) Birmingham nasal douche, made of glass. (f) Evans’ nasal douche.17

In order to achieve control of the flow rate, early models had either a Thudichum's nozzle with a two-way valve (Figure 3c), or no nozzle wherein control of flow rate was achieved by compressing the rubber tube between the finger and thumb (Figure 4b). This last technique was proposed by Dr R V Pierce in 1895, a fervent supporter of nasal rinsing, who wrote; ‘Let no one entertain any feeling of timidity on commencing the use of this instrument, as its operation is perfectly simple and harmless, and, with the fluids which we recommend, is never attended with any strangling, choking, pain or other disagreeable sensations’.Reference Pierce21

An alternative technique was an assisted nasal douche designed by the American otolaryngologists Edward Davis and Beaman Douglas (Figure 4c).Reference Davis and Douglass22 With time, smaller and more portable devices (initially made from glass),17,Reference Moyle23 appeared on the market (Figure 4d–f).

Some inventors proposed the simultaneous rinsing of both nasal cavities with a bilateral nozzle and pressure provided by gravity (Figure 5a and b).Reference Lamport24,Reference Liu25 The scarcity of prototypes makes it difficult to find accounts of their possible benefits over other types of rinsing systems. However, these models had a clear risk of coughing and aspiration when the individual tried to breathe through the mouth.

Fig. 5. (a & b) Bilateral nasal douches with flow achieved by gravity.Reference Lamport24,Reference Liu25

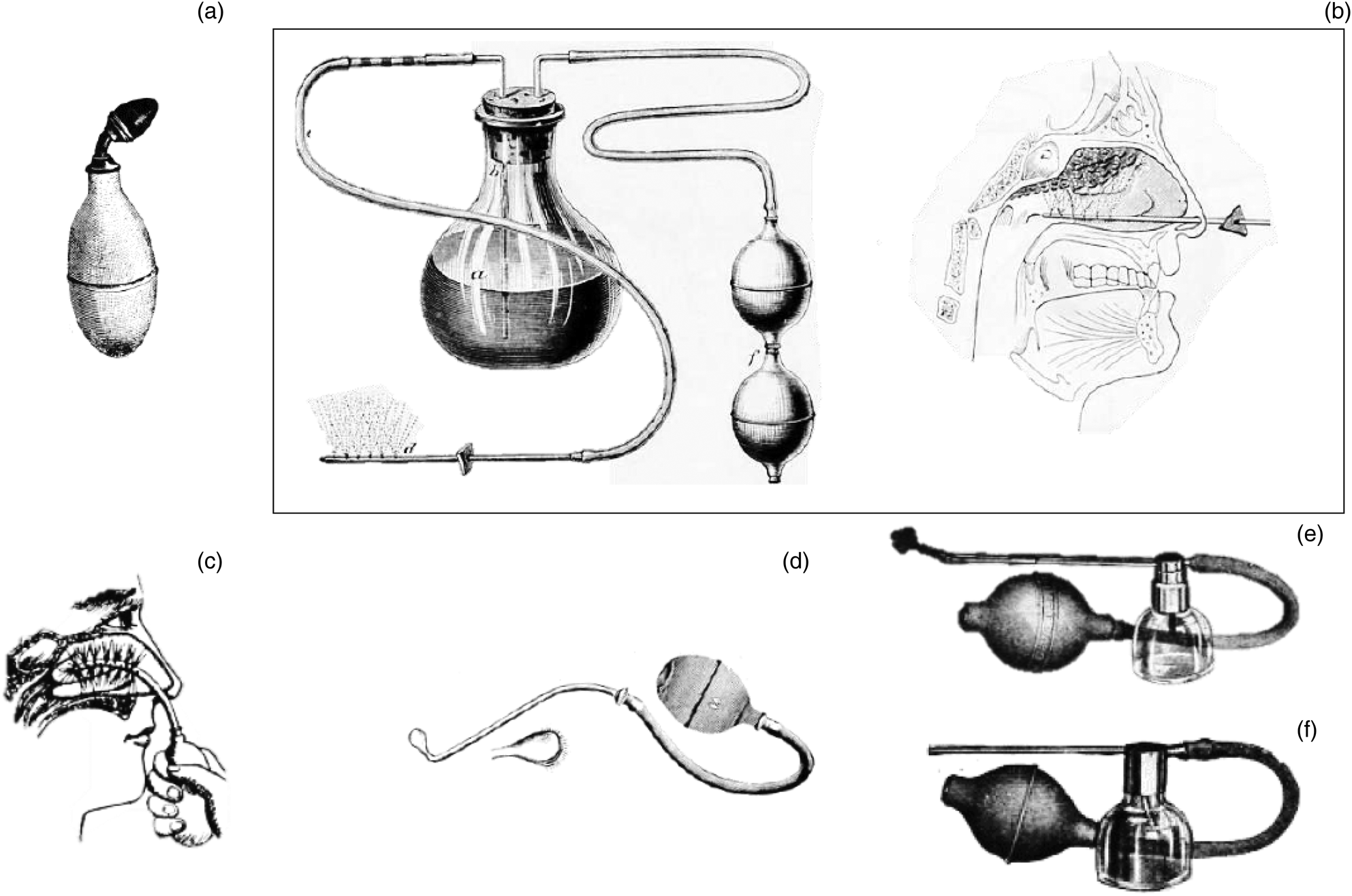

Squeezing mechanisms (insufflators)

Squeeze bottles were first proposed around the same time as gravity-operated devices. Squeeze bottles are simple to operate and inexpensive, but are limited by their variable flow pressure and low volumes. Despite these shortcomings, they remain one of the mainstays of nasal rinsing today. Before the appearance of plastic bottles in the mid-twentieth century, a rubber bulb or insufflator was used as the propelling mechanism, and models were made for either anterior (Figure 6a and c) or posterior (Figure 6d) nasal rinsing.

Fig. 6. (a) Pocket bulb with nozzle.17 (b) Rumbold's nasal spray.Reference Robinson26 (c) Bulb with a soft, rubber, perforated nasal tube. (d) Holme's post-nasal device. (e) DeVilbiss No. 36 posterior insufflator. (f) DeVilbiss No. 32 anterior insufflator.17

In this category, atomisers or spraying devices are included, which have maintained their popularity, regardless of their low shearing force. Models have been developed for anterior (Figure 6f)17 and posterior (Figure 6e) application. Rumbold's apparatus was intended to rinse the superior nasal cavity (Figure 6b). It appears to have come into disuse because of a painful sensation when actioned.Reference Robinson26

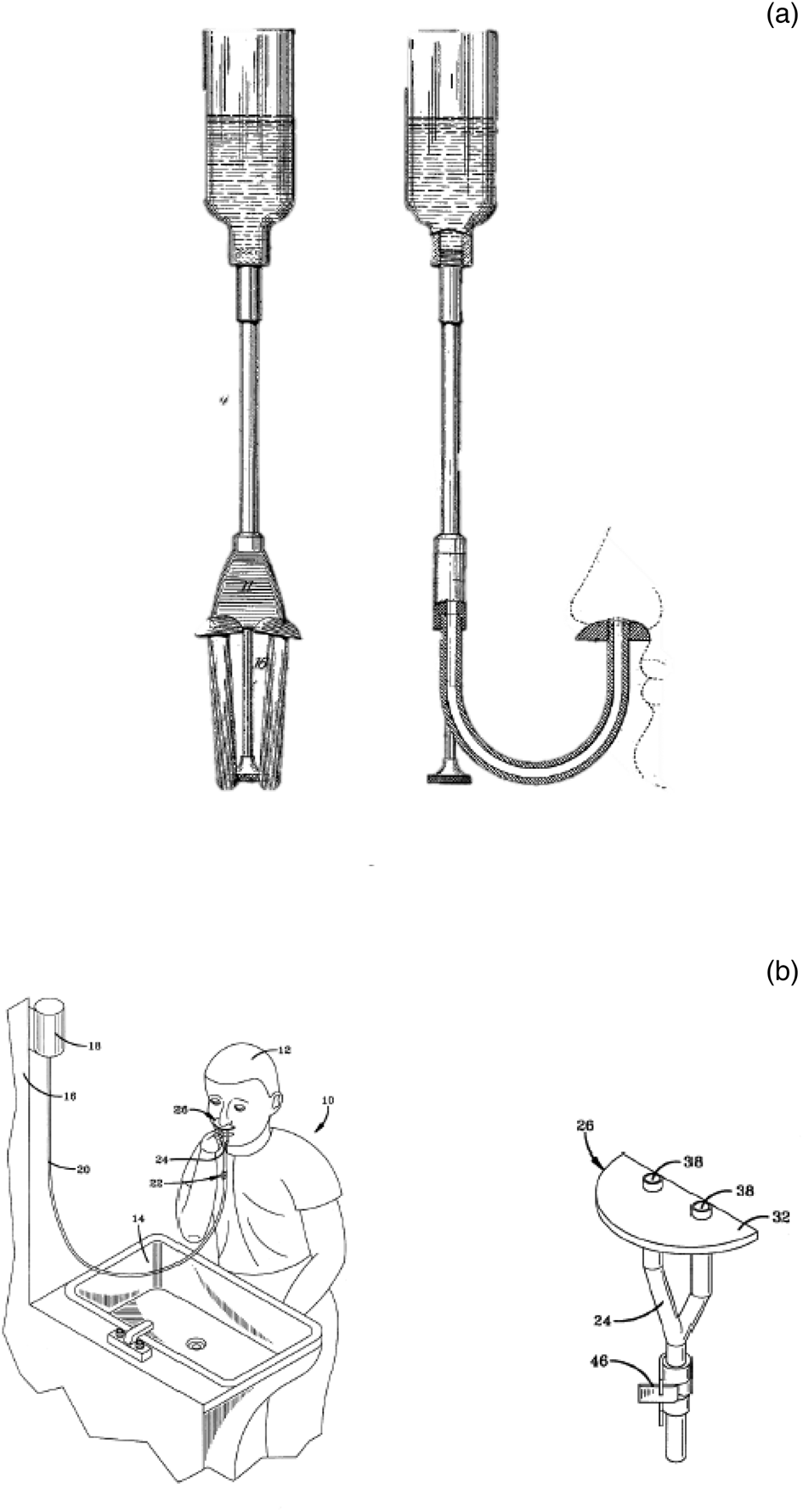

Mouth-actioned devices

These devices use the expiratory pressure to propel the contents of the bottle into the nose. Initial models were made from hard rubber with metallic components (Figure 7a).27As with other types of rinsing devices, glass later became a preferred material for production. A good example is Fowler's nasal douche, which was a one-piece glass container that had an inner tube to increase outflow pressure (Figure 7b).Reference Fowler28 Glass was then progressively substituted with hard plastic (Figure 7c).Reference Griffin29 A significant advantage of this type of device is that the output pressure can be easily controlled by the user.Reference Griffin29

Fig. 7. (a) Munyon's medicament vessel.Reference Munyon27 (b) Fowler's glass nasal douche.Reference Fowler28 (c) Griffin's nasal irrigator.Reference Griffin29

Cups and dishes

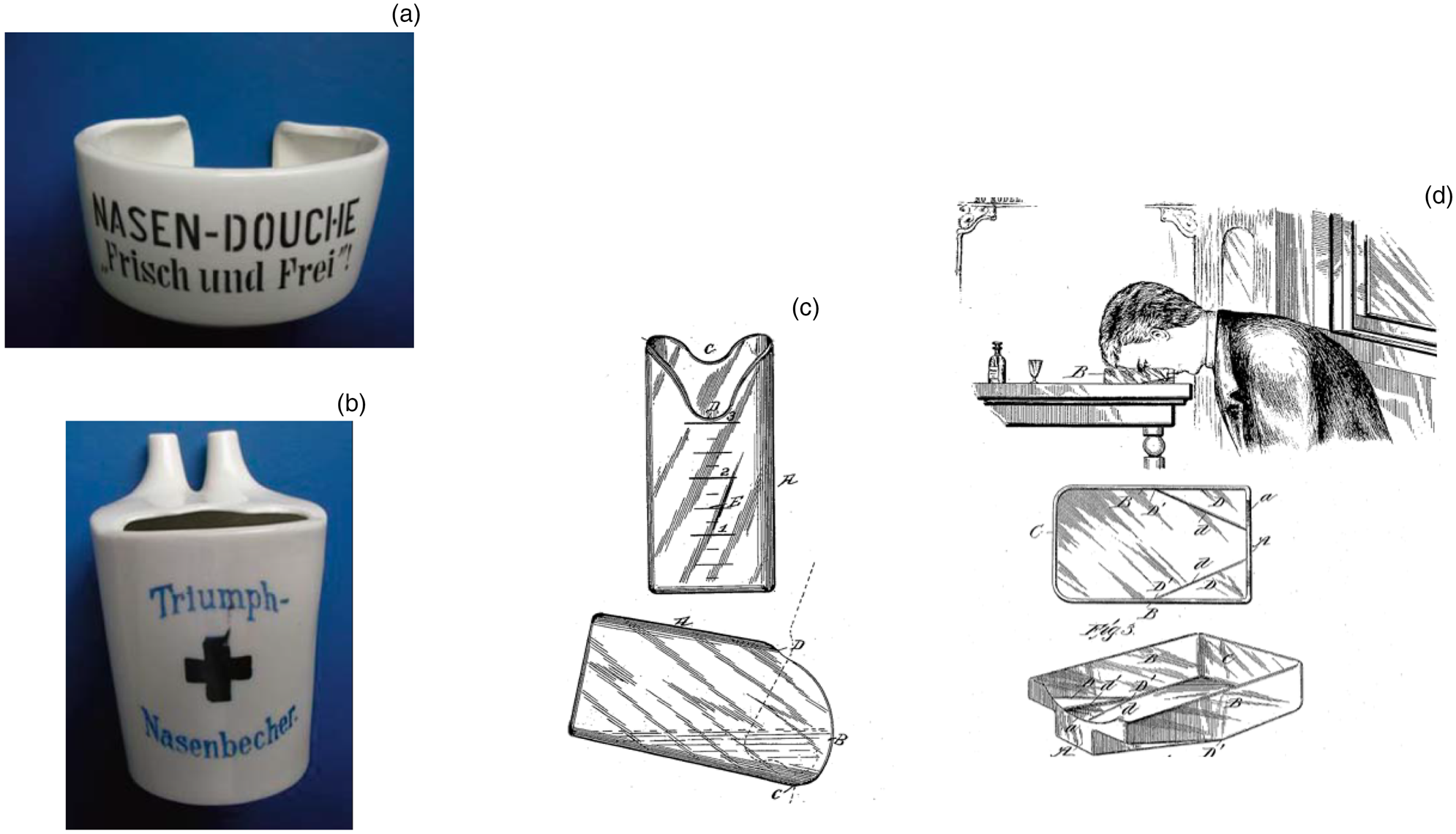

These devices were very popular in the first half of the twentieth century, when many otolaryngologists were concerned that the pressure associated with nasal rinsing had injurious effects on nasal mucosa and the middle ear.Reference Shaw30,Reference Gradle31 The most common materials used for making these cups and dishes were porcelain (Figure 8a and b)Reference Lübbers32 or glass (Figure 8c).Reference Evans33 One interesting object is Harris's nasal dish, patented in 1903, where the objective was to apply the wash through the nose in a rather uncomfortable head position, to prevent the passage of liquid into the throat (Figure 8d).Reference Harris34

Fig. 8. (a & b) Porcelain nasal cups from the beginning of the twentieth century.Reference Lübbers32 (c) Evans’s glass nasal cup.Reference Evans33 (d) Harris's glass nasal dish.Reference Harris34

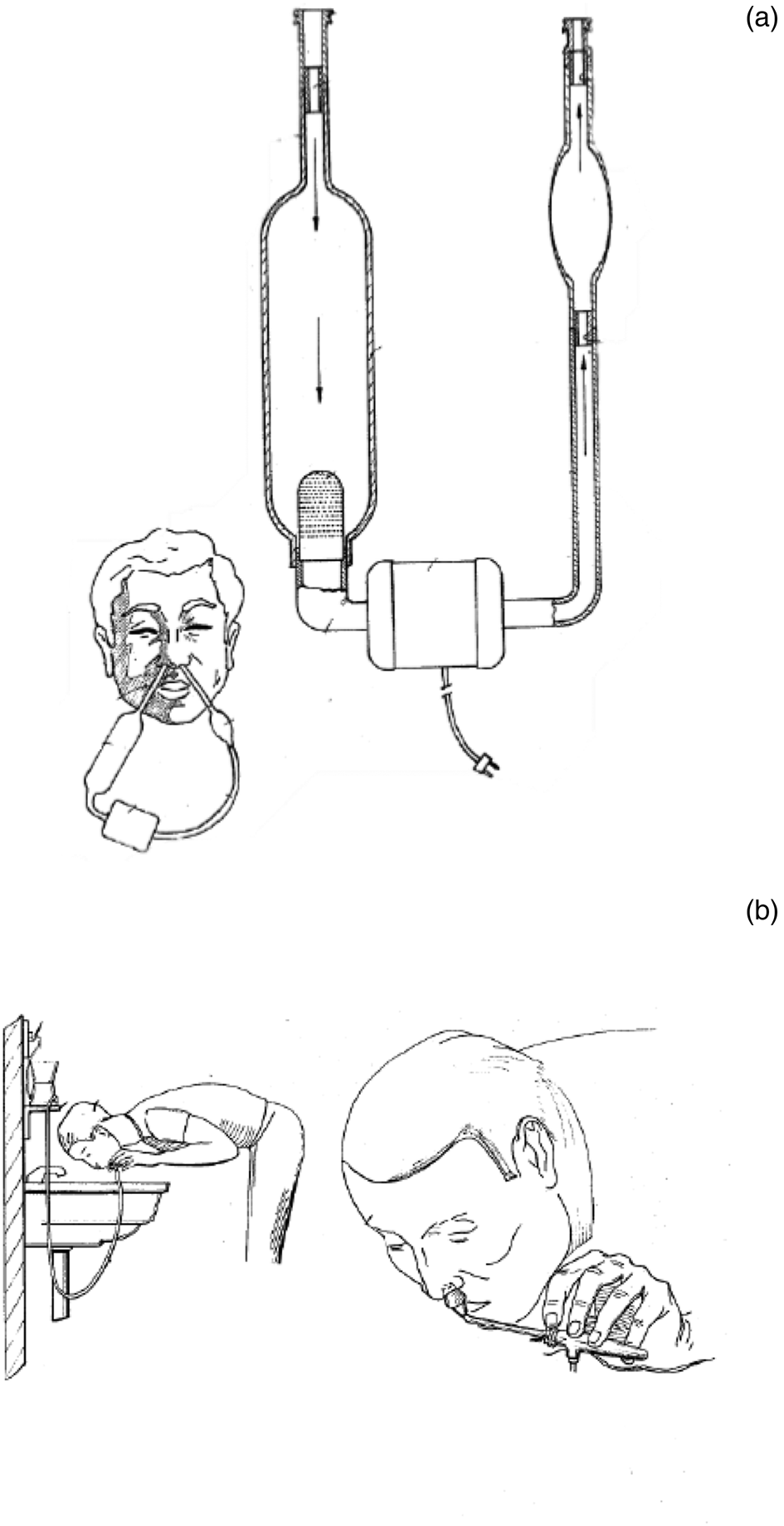

Electric models

Some very interesting electric models have been designed, such as the ‘device for circulating treating fluid through the nasal fossae’, which had an integrated electric pump, but never went into production (Figure 9a).Reference Baya35 Nonetheless, other inventions became very popular, such as Grossan's nasal irrigation system, which became the prototype for some modern designs (Figure 9b).Reference Grossan36 The most appealing feature of these devices is their ability to control flow, with most of them having a pulsating setting. Whether they are indeed superior to their simpler, non-electric counterparts is still a matter of debate.

Fig. 9. (a) Baya Pena's recirculating nasal rinsing electric device.Reference Baya35 (b) Grossan's electric nasal rinsing system with pressure control in the handpiece.Reference Grossan36

Discussion

Although simple in concept, sinus lavage has proven to be a key modality for the treatment of sinonasal conditions since antiquity. Currently, the squeeze plastic bottle has become the most recommended and popular method, having the advantages of transportability, relative low cost and ease of use. However, it has a number of significant limitations, most importantly variations in flow rate and even flow direction.

The ideal device is one that delivers higher volumes at a constant pressure and with continuous flow. Lavage systems currently on the market that use electrical pumps have some of these desired properties; however, their complex operation and dependence on electricity to function, along with their higher price, prevent many patients from using this technology. We feel there is considerable scope for improving the design and function of nasal lavage devices.

Conclusion

Nasal lavage plays a major role in the treatment of sinonasal conditions. The history of the devices created for this purpose is rich. By no means have we covered the whole spectrum of devices created, but we hope that by reviving some of these historical designs, we can inspire otolaryngologists and engineers to perfect current nasal rinsing devices.

Competing interests

None declared