Introduction

Age-related hearing loss is a decrease in hearing ability that happens with age and is a common sensory abnormality of the elderly. According to the World Health Organisation, 466 million adults globally live with disabling hearing loss, including nearly one in three people aged over 65 years.1 Hearing impairment not only affects interpersonal communication but also health, independence, wellbeing, quality of life and daily function and can lead to social isolation, depression and early mortality.Reference Davis, McMahon, Pichora-Fuller, Russ, Lin and Olusanya2–Reference Dimitriadis, Vlastarakos and Nikolopoulos5 In recent years, there has been a growing speculation about the association between cognitive decline and age-related hearing loss.Reference Lin and Albert6 Uhlmann et al. (1989) were amongst the first to find that hearing loss was a strong, independent risk factor for cognitive decline.Reference Uhlmann, Larson, Rees, Koepsell and Duckert7 However, other studies have contested this association.Reference Hong, Mitchell, Burlutsky, Liew and Wang8,Reference Gennis, Garry, Haaland, Yeo and Goodwin9

A recent commission document by the Lancet postulated that hearing loss in mid- and later life is associated with increased risk of dementia.Reference Livingston, Sommerlad, Orgeta, Costafreda, Huntley and Ames10 Dementia is the loss of cognitive functioning and behavioural abilities to such an extent that it interferes with a person's daily life and activities. The aim of the present study was to identify any relationship between hearing loss and a prodromal state of dementia or mild cognitive impairment. Establishing such an association would strengthen the case for a relationship between hearing impairment and dementia and focus intervention development to an earlier stage. Mild cognitive impairment is an intermediate state between normal cognitive functioning and development of dementia.Reference DeCarli11,Reference Petersen, Smith, Waring, Ivnik, Tangalos and Kokmen12 Individuals with mild cognitive impairment have slight impairment in cognitive function with otherwise normal function in the performance of activities of daily living.Reference Levey, Lah, Goldstein, Steenland and Bliwise13 They are at a significantly elevated risk of developing dementia during their lifetime, which is estimated to be around 80 per cent.Reference Petersen, Stevens, Ganguli, Tangalos, Cummings and DeKosky14

Hearing impairment can be either peripheral or central.Reference Gates and Mills3 The peripheral hearing system consists of the peripheral components of hearing (including the cochlea), whereas the central hearing system encompasses the central auditory pathways and influences the way incoming auditory stimuli are perceived and understood (central auditory processing). The key symptom of central hearing loss is an inability of the individual to understand speech in a noisy environment,Reference Gates15 particularly if peripheral hearing (the ability to hear in quiet) remains relatively normal. In the present review article, we include studies that have assessed the link between both types of hearing loss with early dementia.

Materials and methods

The systematic review was undertaken in accordance with the general principles recommended in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.16 A systematic computer-based literature search was performed on the biomedical bibliographical databases Medline and Cochrane library. The search was done on the 24 June 2020 and run from database inception. A copy of the search strategy is presented in Appendix 1. The protocol for this systematic review has been deposited in the Prospero international prospective register of systematic reviews (identification number: CRD42017076183) and can be accessed at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?RecordID=76183.

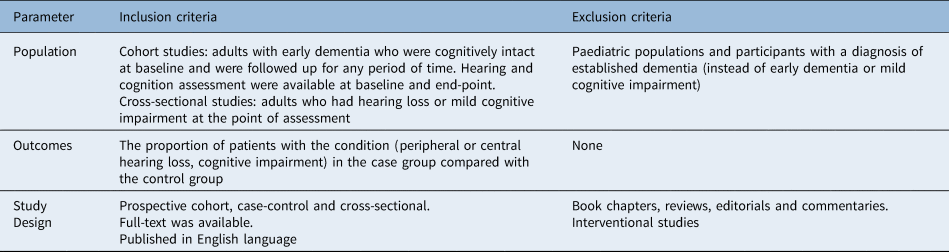

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the population of interest, outcomes and study design are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the population of interest, outcomes and study design

Data analysis

Three authors (KL, PAD and CM) independently selected studies, extracted data and assessed the quality of included studies. Data were extracted from each study and included information on the article identification, year of publication, population (continent), matching for covariates between groups, evaluation period (for longitudinal studies), number of patients per group, hearing and cognition assessment methods, number of male patients, and mean age of patients. Where data were missing, the corresponding authors of the articles were approached by email.

The quality assessment of the cohort studies included in the meta-analysis was done using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.Reference Wells, Shea, O'Connell, Peterson, Welsch and Losos17

Statistical analyses

The meta-analysis was undertaken using Cochrane RevMan review software (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014, Copenhagen, version 5.3). Outcomes reported as dichotomous were estimated as risk ratios with associated 95 per cent confidence interval (CI). Where studies did not report participant numbers but gave an effect size with 95 per cent CI, these were pooled in RevMan using the generic inverse variance method. Random-effects models were applied. Effect estimates (estimated in RevMan as Z-scores) were considered significant at p < 0.05. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I-squared statistic. Where data were not suitable for pooling in a meta-analysis, a narrative synthesis using tables and text was reported.

Results

The electronic searches identified 521 unique citations. One additional citation was provided by a clinical expert. Of these, 465 were excluded based on their title and abstract. Of 56 citations obtained as full-text, 22 were excluded.Reference Villeneuve, Hommet, Aussedat, Lescanne, Reffet and Bakhos18–Reference Maharani, Dawes, Nazroo, Tampubolon and Pendleton39 Details of the studies excluded at full-text are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Articles excluded at full-text

Thirty-four studies, reporting on 48 017 participants, fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review. Eighteen of these studies were eligible for and were included in the meta-analysis. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart of the study selection process is shown in Figure 1. The characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 3.

Fig. 1. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart of the study selection process. MCI = mild cognitive impairment; HL = hearing loss

Table 3. Characteristics of included studies

*Matching: 1 = age; 2 = gender; 3 = education; 4 = hypertension. CAP = selective auditory attention test, dichotic digits test, auditory fusion test, pitch pattern sequences test and auditory memory battery of Goldman–Fristoe–Woodcock; NA = not available

These studies were published between 1986 and 2019 and conducted in America, Asia, Australia, Africa and Europe. Ten of the studies were cohort,Reference Schubert, Cruickshanks, Fischer, Pinto, Chen and Huang40–Reference Gates, Cobb, Linn, Rees, Wolf and D'Agostino49 23 were cross-sectional,Reference Uhlmann, Larson, Rees, Koepsell and Duckert7,Reference Han, Tang and Ma50–Reference DeVore71 and 1 study was both a cross-sectional and cohort study.Reference Heywood, Gao, Nyunt, Feng, Chong and Lim72 Recruited participant numbers ranged from 20Reference Strouse, Hall and Burger70 to 13 731.Reference Yang and Gu46 The results of the quality assessment are presented in Table 4. All of the cohort studies scored more than six stars (out of a total of nine stars).

Table 4. Quality assessment of the included cohort studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

One star is attributed per item if achieved, except for ‘comparability’ which can achieve up to two stars. All of the cohort studies scored more than six stars (out of a maximum of nine).

Hearing assessment

Most of the studies used pure tone audiometry as the main auditory assessment method, and this measures hearing sensitivity. Self-reported or assessor-reported hearing loss was used by 10 studies,Reference Yu and Woo41–Reference Gallagher, Kiss, Lanctot and Herrmann44,Reference Yang and Gu46,Reference Gurgel, Ward, Schwartz, Norton, Foster and Tschanz48,Reference Heward, Stone, Paddick, Mkenda, Gray and Dotchin51,Reference Benito-León, Mitchell, Vega and Bermejo-Pareja64,Reference DeVore71,Reference Heywood, Gao, Nyunt, Feng, Chong and Lim72 and in 1 paper the assessment method was not reported.Reference Han, Tang and Ma50 Some studies used central auditory function tests, such as dichotic digits test, speech audiometry, synthetic sentence identification with ipsilateral competing message and so on.Reference Uhlmann, Larson, Rees, Koepsell and Duckert7,Reference Gates, Cobb, Linn, Rees, Wolf and D'Agostino49,Reference Lister, Harrison Bush, Andel, Matthews, Morgan and Edwards56,Reference Quaranta, Coppola, Casulli, Barulli, Lanza and Tortelli59,Reference Rahman, Mohamed, Albanouby and Bekhet61–Reference Gates, Gibbons, McCurry, Crane, Feeney and Larson63,Reference Gates, Anderson, Feeney, McCurry and Larson65,Reference Frisina and Frisina68,Reference Strouse, Hall and Burger70 The definition of hearing loss from the World Health Organization73 was used by most studies, but the frequencies tested ranged from: 500 to 4000 Hz,Reference Deal, Betz, Yaffe, Harris, Purchase-Helzner and Satterfield45,Reference Fischer, Cruickshanks, Schubert, Pinto, Carlsson and Klein47,Reference Bruckmann and Pinheiro54,Reference Bucks, Dunlop, Taljaard, Brennan-Jones, Hunter and Wesnes55,Reference Deal, Sharrett, Albert, Coresh, Mosley and Knopman57,Reference Lin, Ferrucci, Metter, An, Zonderman and Resnick60,Reference Tay, Kifley, Lindley, Landau, Ingham and Mitchell66 1000 to 4000 Hz,Reference Van Boxtel, Beijsterveldt van, Houx, Anteunis, Metsemakers and Jolles67 250 to 2000 HzReference Zhang, Yang, Liu, Huang, Chen and Zhang58 and 500 to 3000 Hz.Reference Uhlmann, Larson, Rees, Koepsell and Duckert7 One study used the hearing threshold at 4 kHz only to separate the different groups of hearing loss.Reference Frisina and Frisina68

Cognitive assessment

The cognitive assessment tool that was used by most researchers was the Mini Mental State ExaminationReference Uhlmann, Larson, Rees, Koepsell and Duckert7,Reference Schubert, Cruickshanks, Fischer, Pinto, Chen and Huang40,Reference Vaccaro, Zaccaria, Colombo, Abbondanza and Guaita42,Reference Yang and Gu46,Reference Fischer, Cruickshanks, Schubert, Pinto, Carlsson and Klein47,Reference Gates, Cobb, Linn, Rees, Wolf and D'Agostino49,Reference Han, Tang and Ma50,Reference Iliadou, Bamiou, Sidiras, Moschopoulos, Tsolaki and Nimatoudis53,Reference Bruckmann and Pinheiro54,Reference Zhang, Yang, Liu, Huang, Chen and Zhang58,Reference Quaranta, Coppola, Casulli, Barulli, Lanza and Tortelli59,Reference Lin, Ferrucci, Metter, An, Zonderman and Resnick60,Reference Idrizbegovic, Hederstierna, Dahlquist, Kämpfe Nordström, Jelic and Rosenhall62,Reference Benito-León, Mitchell, Vega and Bermejo-Pareja64,Reference Tay, Kifley, Lindley, Landau, Ingham and Mitchell66,Reference DeVore71,Reference Heywood, Gao, Nyunt, Feng, Chong and Lim72 or its modified version, the Modified Mini Mental State tool.Reference Deal, Betz, Yaffe, Harris, Purchase-Helzner and Satterfield45,Reference Gurgel, Ward, Schwartz, Norton, Foster and Tschanz48,Reference Strouse, Hall and Burger70 A score below 24 on the Mini Mental State ExaminationReference Folstein, Folstein and McHugh74 was considered abnormal by most studies.Reference Uhlmann, Larson, Rees, Koepsell and Duckert7,Reference Schubert, Cruickshanks, Fischer, Pinto, Chen and Huang40,Reference Yang and Gu46,Reference Fischer, Cruickshanks, Schubert, Pinto, Carlsson and Klein47,Reference Iliadou, Bamiou, Sidiras, Moschopoulos, Tsolaki and Nimatoudis53,Reference Zhang, Yang, Liu, Huang, Chen and Zhang58,Reference Tay, Kifley, Lindley, Landau, Ingham and Mitchell66 The cut-off score was 27 in two studies.Reference DeVore71,Reference Heywood, Gao, Nyunt, Feng, Chong and Lim72 In another study, Mini Mental State examination score thresholds were adjusted for education level.Reference Han, Tang and Ma50 Other cognitive assessment tests used included the Montreal Cognitive Assessment,Reference Iliadou, Bamiou, Sidiras, Moschopoulos, Tsolaki and Nimatoudis53,Reference Lister, Harrison Bush, Andel, Matthews, Morgan and Edwards56 Cognitive Drug Research Computerised Assessment System,Reference Bucks, Dunlop, Taljaard, Brennan-Jones, Hunter and Wesnes55 verbal fluency,Reference Vaccaro, Zaccaria, Colombo, Abbondanza and Guaita42,Reference Bucks, Dunlop, Taljaard, Brennan-Jones, Hunter and Wesnes55,Reference Deal, Sharrett, Albert, Coresh, Mosley and Knopman57,Reference Benito-León, Mitchell, Vega and Bermejo-Pareja64 National Adult Reading Test,Reference Bucks, Dunlop, Taljaard, Brennan-Jones, Hunter and Wesnes55 Delayed Word Recall Test,Reference Deal, Sharrett, Albert, Coresh, Mosley and Knopman57 Digit Symbol Substitution Test,Reference Deal, Sharrett, Albert, Coresh, Mosley and Knopman57 Wechsler Adult Intelligence Test,Reference Zhang, Yang, Liu, Huang, Chen and Zhang58 Clinical Dementia Rating Scale,Reference Gallagher, Kiss, Lanctot and Herrmann44,Reference Quaranta, Coppola, Casulli, Barulli, Lanza and Tortelli59,Reference Heywood, Gao, Nyunt, Feng, Chong and Lim72 Frontal Assessment Battery,Reference Quaranta, Coppola, Casulli, Barulli, Lanza and Tortelli59 Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test,Reference Lin, Ferrucci, Metter, An, Zonderman and Resnick60 Trail Making Test (parts A and B),Reference Schubert, Cruickshanks, Fischer, Pinto, Chen and Huang40,Reference Vaccaro, Zaccaria, Colombo, Abbondanza and Guaita42,Reference Lin, Ferrucci, Metter, An, Zonderman and Resnick60,Reference Gates, Gibbons, McCurry, Crane, Feeney and Larson63,Reference Benito-León, Mitchell, Vega and Bermejo-Pareja64 Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Recall Test,Reference Vaccaro, Zaccaria, Colombo, Abbondanza and Guaita42 Stroop Letter and Category Fluency,Reference Lin, Ferrucci, Metter, An, Zonderman and Resnick60,Reference Gates, Gibbons, McCurry, Crane, Feeney and Larson63 the American version of the Nelson Adult Reading Test,Reference Lin, Ferrucci, Metter, An, Zonderman and Resnick60 Abbreviated Memory Inventory for the Chinese,Reference Yu and Woo41 Cambridge Cognitive Examination,Reference Rahman, Mohamed, Albanouby and Bekhet61 Clock Drawing Test,Reference Vaccaro, Zaccaria, Colombo, Abbondanza and Guaita42,Reference Gates, Gibbons, McCurry, Crane, Feeney and Larson63 Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument,Reference Gates, Gibbons, McCurry, Crane, Feeney and Larson63,Reference Gates, Anderson, Feeney, McCurry and Larson65 Letter-Digit Symbol Test,Reference Van Boxtel, Beijsterveldt van, Houx, Anteunis, Metsemakers and Jolles67 Auditory Verbal Learning Test,Reference Van Boxtel, Beijsterveldt van, Houx, Anteunis, Metsemakers and Jolles67 Clinical Dementia Rating ScaleReference Gates, Karzon, Garcia, Peterein, Storandt and Morris69 and Storandt Battery.Reference Strouse, Hall and Burger70

Results of quantitative analysis

Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment

Across four cross-sectional studies comparing mild cognitive impairment between people with peripheral hearing loss (n = 1292) and without peripheral hearing loss (n = 1041), the risk ratio was 1.39 (random-effects, 95 per cent CI = 1.18 to 1.64; p = 0.0001; I2 = 0 per cent); significantly more people with peripheral hearing loss had mild cognitive impairment compared with those without peripheral hearing loss.

The risk ratio for one study comparing mild cognitive impairment between people with central hearing loss (n = 113) and without central hearing loss (n = 86) was 1.54 (random-effects, 95 per cent CI = 1.24 to 1.90; p < 0.0001; I2 not applicable); significantly more people with central hearing loss had mild cognitive impairment compared with those without central hearing loss.

The pooled risk ratio across all studies was 1.44 (random-effects, 95 per cent CI = 1.27 to 1.64; p < 0.00001; I2 = 0 per cent) (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment amongst hearing impaired patients. M-H = Mantel-Haenszel; CI = confidence interval

Prevalence of hearing impairment

Across three cross-sectional studies comparing peripheral hearing loss between people with mild cognitive impairment (n = 82) and without mild cognitive impairment (n = 108), the risk ratio (risk ratio) was 1.40 (random-effects, 95 per cent CI = 1.10 to 1.77; p = 0.005; I2 = 0 per cent); significantly more people with mild cognitive impairment had peripheral hearing loss compared with those without (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Prevalence of hearing impairment amongst patients with mild cognitive impairment (risk ratio). M-H = Mantel-Haenszel; CI = confidence interval

Across two cross-sectional studies reporting the between-group difference as an odds ratio (i.e., no raw data were available) comparing peripheral hearing loss between people with mild cognitive impairment and without mild cognitive impairment, the odds ratio was 1.41 (random-effects, 95 per cent CI = 1.02 to 1.96; p = 0.04; I2 = 59 per cent); statistical heterogeneity was evident and the between-group difference was not statistically significant (Figure 4).

Fig. 4. Prevalence of hearing impairment amongst patients with mild cognitive impairment (odds ratio). SE = standard error; IV = Instrumental variable; CI = confidence interval

Hearing loss in people with mild cognitive impairment

Peripheral hearing loss

Across six cohort studies comparing mild cognitive impairment between people with peripheral hearing loss (n = 8235) and without peripheral hearing loss (n = 17 891), the risk ratio was 2.06 (random-effects, 95 per cent CI = 1.35 to 3.15; p = 0.0008; I2 = 97 per cent); significantly more people with peripheral hearing loss had mild cognitive impairment compared with those without, although a high level of statistical heterogeneity was evident (Figure 5).

Fig. 5. Incidence of mild cognitive impairment with and without peripheral hearing loss (risk ratio). M-H = Mantel-Haenszel; CI = confidence interval

Across two cohort studies reporting the between-group difference as a hazard ratio (i.e. no raw data were available) comparing mild cognitive impairment between people with and without peripheral hearing loss, the hazard ratio was 1.40 (random-effects, 95 per cent CI = 1.64 to 1.95; p < 0.00001; I2 = 0 per cent); significantly more people with peripheral hearing loss had mild cognitive impairment compared with those without peripheral hearing loss (Figure 6).

Fig. 6. Incidence of mild cognitive impairment with and without peripheral hearing loss (hazard ratio). SE = standard error; IV = Instrumental variable; CI = confidence interval

The between-group difference for one cohort study reporting the outcome as an odds ratio (i.e. no raw data were available) comparing mild cognitive impairment between people with and without peripheral hearing loss was 1.70 (random-effects, 95 per cent CI = 1.30 to 2.22; p = 0.0001); significantly more people with peripheral hearing loss had mild cognitive impairment compared with those without peripheral hearing loss (Figure 7).

Fig. 7. Odds ratio outcomes in between-group difference (with and without peripheral hearing loss). SE = standard error; IV = Instrumental variable; CI = confidence interval

The between-group differences for one cohort study reporting the outcome as risk ratio (i.e. no raw data were available) comparing mild cognitive impairment between people with and without mild, moderate or severe peripheral hearing loss were: mild 1.26 (random-effects, 95 per cent CI = 1.15 to 1.38; p < 0.0001), moderate 1.29 (random-effects, 95 per cent CI = 1.13 to 1.47; p = 0.0002) and severe 1.37 (random-effects, 95 per cent CI = 1.06 to 1.7; p = 0.02); significantly more people with peripheral hearing loss had mild cognitive impairment compared with those without peripheral hearing loss in all categories (Figure 8).

Fig. 8. Risk ratio outcomes in between-group difference (with and without peripheral hearing loss). SE = standard error; IV = Instrumental variable; CI = confidence interval

Results of narrative synthesis

Prevalence of early dementia

The outcomes from the studies on early dementia amongst hearing impaired patients are presented in Table 5. Out of nine studies included in this category, fourReference Bruckmann and Pinheiro54,Reference Bucks, Dunlop, Taljaard, Brennan-Jones, Hunter and Wesnes55,Reference Zhang, Yang, Liu, Huang, Chen and Zhang58,Reference Tay, Kifley, Lindley, Landau, Ingham and Mitchell66 did not identify a significant association between hearing loss and early dementia. The demographic data of the participants (age, gender, race, comorbidities) and the outcome measures used differed between the studies, and a direct comparison of the results was not possible. The number of participants ranged from 21Reference Zhang, Yang, Liu, Huang, Chen and Zhang58 to 1969.Reference Bucks, Dunlop, Taljaard, Brennan-Jones, Hunter and Wesnes55 Bucks et al. (2016) assessed the participants’ premorbid intelligence quotient using the National Adult Reading Test as an index of cognitive reserve.Reference Bucks, Dunlop, Taljaard, Brennan-Jones, Hunter and Wesnes55 They concluded that hearing loss is not an important factor of contemporaneous attention, memory or executive function in middle-aged adults once several covariates, including cognitive reserve, education, age, sex and depression are accounted for.

Table 5. Outcomes from the studies of prevalence of early dementia amongst hearing-impaired patients

During the 23-year follow up and after adjusting for demographic data and disease covariates, Deal et al. (2015) found that patients with moderate or severe hearing loss had a 0.29 standard deviation (SD; 95 per cent CI = 0.05 to 0.54) decline for the global composite score (sum of the three neuropsychological tests administered: Word Fluency Test, Delayed Word Recall Test and Digit Symbol Substitution Test).Reference Deal, Sharrett, Albert, Coresh, Mosley and Knopman57 A hearing assessment was completed at baseline only. There was no strong association observed on the global composite score between patients with mild hearing loss and those with normal hearing at baseline (p = 0.570). Interestingly, it was observed that hearing aid users had a slower rate of cognitive decline compared with non-users. Lin et al. (2011) commented ‘the magnitude of the reduction in cognitive performance associated with hearing loss is clinically significant with the reduction associated with a 25 dB hearing loss being equivalent to an age difference of 6.8 years on tests of executive function’.Reference Lin, Ferrucci, Metter, An, Zonderman and Resnick60

Hearing impairment and early dementia

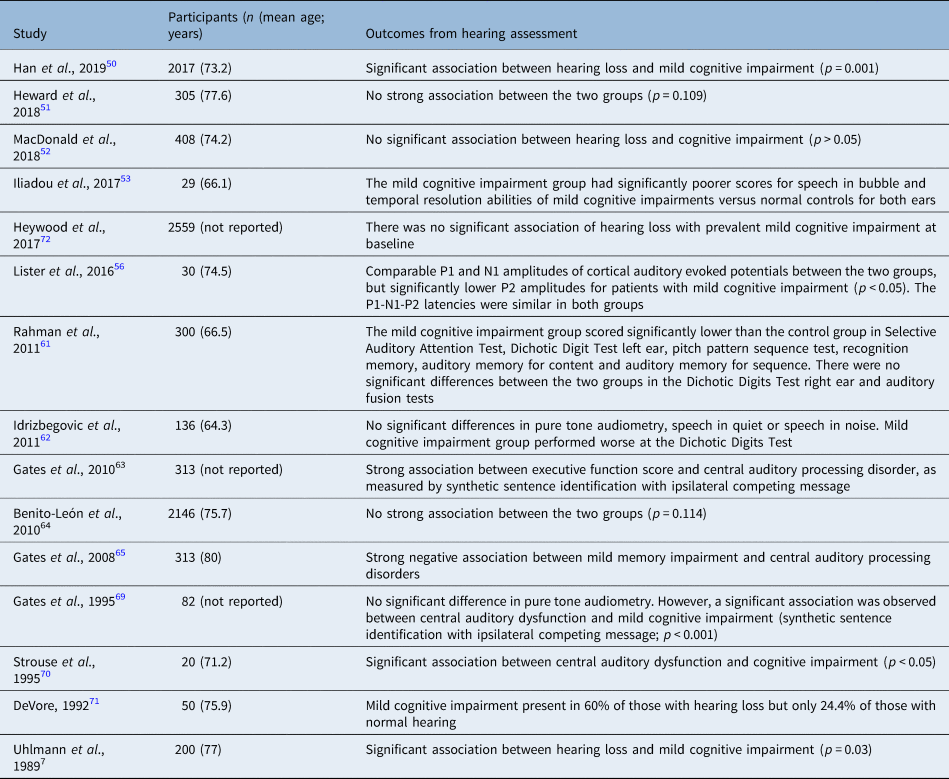

The outcomes of the studies on hearing impairment and mild cognitive impairment are presented in Table 6.

Table 6. Outcomes from the studies of prevalence of hearing loss amongst patients with mild cognitive impairment

Similar to the studies described above, the results in this category vary considerably. Four studies out of 15 failed to find any strong association between mild cognitive impairment and hearing loss.Reference Heward, Stone, Paddick, Mkenda, Gray and Dotchin51,Reference MacDonald, Keller, Brewster and Dixon52,Reference Benito-León, Mitchell, Vega and Bermejo-Pareja64,Reference Heywood, Gao, Nyunt, Feng, Chong and Lim72 Some studies found a strong association between mild cognitive impairment and central hearing loss.Reference Han, Tang and Ma50,Reference Lister, Harrison Bush, Andel, Matthews, Morgan and Edwards56,Reference Rahman, Mohamed, Albanouby and Bekhet61–Reference Gates, Gibbons, McCurry, Crane, Feeney and Larson63,Reference Gates, Anderson, Feeney, McCurry and Larson65,Reference Gates, Karzon, Garcia, Peterein, Storandt and Morris69,Reference Strouse, Hall and Burger70

Peripheral hearing loss was found to be significantly associated with mild cognitive impairment in two studies,Reference Uhlmann, Larson and Koepsell32,Reference DeVore71 but no such association was observed in two other studies.Reference Idrizbegovic, Hederstierna, Dahlquist, Kämpfe Nordström, Jelic and Rosenhall62,Reference Gates, Karzon, Garcia, Peterein, Storandt and Morris69 There was considerable variance in the number of recruited participants per study from 20Reference Strouse, Hall and Burger70 to 2146.Reference Benito-León, Mitchell, Vega and Bermejo-Pareja64 There was no consistency in the outcome measures used (e.g. in DeVore's study (1992), the participants did not undergo any formal audiometryReference DeVore71 whereas in the study by Gates et al. (1995) they underwent several tests including pure tone audiometry, speech audiometry, synthetic sentence identification with ipsilateral competing message, distortion product otoacoustic emissions, and auditory brainstem response.Reference Gates, Karzon, Garcia, Peterein, Storandt and Morris69 Lister et al. (2016) sought to identify an association between cortical auditory evoked potentials and mild cognitive impairment by means of changes to the P1-N1-P2 complex.Reference Lister, Harrison Bush, Andel, Matthews, Morgan and Edwards56 Their findings might be consistent with further changes of inhibition, in the presence of mild cognitive impairment, with fewer overall resources being available to devote to the task. The cognitively normal older adults had significantly larger P2 amplitudes than those with probable mild cognitive impairment (3.7 (SD, 1.9) vs 1.8 (SD, 1.0)), but P1-N1-P2 latencies were similar in both groups. Gates et al. (2010) recruited 313 patients from the longitudinal Adult Changes in Thought study and grouped them according to their cognitive function as normal (n = 232), memory-impaired (n = 60) or demented (n = 21).Reference Gates, Gibbons, McCurry, Crane, Feeney and Larson63 One SD poorer executive function was associated with a −9.2 per cent point difference in synthetic sentence identification with ipsilateral competing message, −15 per cent point difference in Dichotic Sentence Identification Test and −8.4 per cent point difference in Dichotic Digits Test. Finally, Uhlmann et al. (1989) postulated that the risk of dementia was increased for mild and moderate hearing loss and reached statistical significance for hearing loss of more than 40 dB (p < 0.05).Reference Uhlmann, Larson, Rees, Koepsell and Duckert7

Early dementia or cognitive decline and hearing impairment

The outcomes of studies of early dementia or cognitive decline amongst patients with hearing impairment are presented in Table 7. A significant correlation between hearing loss and incidence of early dementia or cognitive decline was reported in 7 out of 11 studies included in this category.Reference Yu and Woo41–Reference Fischer, Cruickshanks, Schubert, Pinto, Carlsson and Klein47 The number of recruited participants ranged from 1662Reference Gates, Cobb, Linn, Rees, Wolf and D'Agostino49 to 13 731.Reference Yang and Gu46 The means of assessing hearing varied between the studies (pure tone audiometryReference Schubert, Cruickshanks, Fischer, Pinto, Chen and Huang40,Reference Deal, Betz, Yaffe, Harris, Purchase-Helzner and Satterfield45 versus self-reported.Reference Yu and Woo41–Reference Gallagher, Kiss, Lanctot and Herrmann44,Reference Yang and Gu46 The majority of studies used the Mini Mental State Examination or Modified Mini Mental State to assess cognition, but in a few studies the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale,Reference Gallagher, Kiss, Lanctot and Herrmann44 abbreviated Memory Inventory for the ChineseReference Yu and Woo41 and subjective cognitive decline testsReference Curhan, Willett, Grodstein and Curhan43 were used.

Table 7. Studies of incidence of early dementia or cognitive decline amongst patients with hearing impairment

CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio

In a study by Gurgel et al. (2014), all-cause dementia was observed in 16.3 per cent of patients with hearing loss (at baseline) but only in 12.1 per cent of those without hearing loss (p < 0.001).Reference Gurgel, Ward, Schwartz, Norton, Foster and Tschanz48 Following multivariate analysis, hearing loss was found to be an independent factor for dementia. When evaluating the subgroup of patients who were cognitively intact at baseline and taking into account all covariates, hearing loss was not found to be a strong independent risk factor for developing dementia (p = 0.09). Gates et al. (1996) postulated that central hearing dysfunction precedes the emergence of cognitive decline and dementia and recommended that both peripheral and central hearing tests be obtained as part of the general health evaluation of the elderly.Reference Gates, Cobb, Linn, Rees, Wolf and D'Agostino49

Discussion

We present a quantitative and qualitative analysis of cross-sectional and longitudinal, observational studies looking at the relationship between hearing impairment and mild cognitive impairment. Most of the included studies, except 11 studiesReference Schubert, Cruickshanks, Fischer, Pinto, Chen and Huang40,Reference Yang and Gu46,Reference Heward, Stone, Paddick, Mkenda, Gray and Dotchin51,Reference MacDonald, Keller, Brewster and Dixon52,Reference Bruckmann and Pinheiro54,Reference Bucks, Dunlop, Taljaard, Brennan-Jones, Hunter and Wesnes55,Reference Zhang, Yang, Liu, Huang, Chen and Zhang58,Reference Benito-León, Mitchell, Vega and Bermejo-Pareja64,Reference Tay, Kifley, Lindley, Landau, Ingham and Mitchell66,Reference DeVore71,Reference Heywood, Gao, Nyunt, Feng, Chong and Lim72 , observed a significant association between hearing loss and early dementia or cognitive decline.

The pooled risk ratio across all studies of prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in people with hearing lossReference Bruckmann and Pinheiro54,Reference Deal, Sharrett, Albert, Coresh, Mosley and Knopman57,Reference Quaranta, Coppola, Casulli, Barulli, Lanza and Tortelli59 was 1.44 (random-effects, 95 per cent CI = 1.27 to 1.64; p < 0.00001; I2 = 0 per cent). When analysed separately, significantly more people with either peripheral or central hearing loss had mild cognitive impairment compared with those without. When analysing the prevalence of hearing loss amongst patients with mild cognitive impairment, the risk ratio was 1.40 (random-effects, 95 per cent CI = 1.10 to 1.77; p = 0.005; I2 = 0 per cent), showing significantly more people with mild cognitive impairment had peripheral hearing loss compared with those without. However, on analysis of the papers that presented their data as an odds ratio, statistical heterogeneity was evident, and the between-group difference was not statistically significant.

The meta-analysis of incidence of hearing loss in patients with mild cognitive impairment showed that there was a correlation between hearing loss and incidence of early dementia or cognitive decline. Across 6 cohort studies where data was provided, the risk ratio was 2.06 (random-effects, 95 per cent CI = 1.35 to 3.15; p = 0.0008; I2 = 97 per cent); across 2 cohort studies, the hazard ratio was 1.40 (random-effects, 95 per cent CI = 1.64 to 1.95; p < 0.00001; I2 = 0 per cent). Even in two separate cohort studies where the raw data was not available, the report outcomes that were reported as odds ratio and risk ratio did show that significantly more people with peripheral hearing loss had mild cognitive impairment compared with those without.

The included studies varied significantly in terms of the outcome measures used, the number of participants, the length of follow up and the use of covariates when analysing their results. Therefore, a direct comparison of the studies was not always possible. Most studies present cross-sectional data rather than data on longitudinal trajectories of cognitive function and hearing loss over time. Therefore, our estimates of the expected change in cognitive scores associated with hearing loss and age may be subject to bias by cohort effects or obscured by inter-individual heterogeneity in participant characteristics.

• This study looks at all cross-sectional and cohort studies evaluating the relationship between age-related hearing loss and mild cognitive impairment

• Most studies included in this review observed a significant association between hearing loss and incident mild cognitive impairment

• Further well-designed, large scale, prospective studies are needed to verify this association

Most studies included homogeneous populations (e.g. white people, well-educated, heath-awareReference Lin, Ferrucci, Metter, An, Zonderman and Resnick60). Therefore, we should be cautious when generalising the outcomes of these studies. One key limitation across multiple studies is the variability in how hearing loss was measured and how audiometric data were analysed (e.g. choice of pure tone thresholds used to define hearing loss). The effect of biased or imprecise assessments of hearing thresholds would likely decrease sensitivity to detect associations because of increased variance. Some studies relied on subjective reporting of hearing loss.Reference Yu and Woo41–Reference Curhan, Willett, Grodstein and Curhan43,Reference Yang and Gu46,Reference Gurgel, Ward, Schwartz, Norton, Foster and Tschanz48,Reference Heward, Stone, Paddick, Mkenda, Gray and Dotchin51,Reference Benito-León, Mitchell, Vega and Bermejo-Pareja64 This represents a crude method for identifying hard of hearing individuals, but studies have shown that subjective hearing assessments have been valid and reliable when compared against standard audiometry.Reference Nondahl, Cruickshanks, Wiley, Tweed, Klein and Klein75,Reference Sindhusake, Mitchell, Smith, Golding, Newall and Hartley76 Similarly, the cognitive assessment tools used varied between the studies; therefore, making a direct comparison of the outcomes difficult. Finally, the use of covariates during regression analysis varied between the studies included in this meta-analysis, from noneReference DeVore71 to many.Reference Benito-León, Mitchell, Vega and Bermejo-Pareja64 Using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, all of the cohort studies scored seven or more stars out of nine, indicating generally good quality of the individual studies.

Strengths and limitations

This study was undertaken according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; two electronic sources were searched and there was contact with experts. Study selection and data extraction were undertaken independently, and a quality assessment was undertaken and data were pooled in a meta-analysis. The limitations were that grey literature and conference abstracts were not searched. We also acknowledge the limitations of pooling data from observational studies in a meta-analysis and the potential for spurious results. Finally, a formal assessment of publication bias was not undertaken.

A recent commissioning document postulated that hearing loss is an independent risk factor for developing dementia.Reference Livingston, Sommerlad, Orgeta, Costafreda, Huntley and Ames10 This is consistent with our findings that there might be a link between hearing loss and mild cognitive impairment, a prodromal stage of dementia. Finally, hearing loss may be causally related to mild cognitive impairment and dementia, possibly through exhaustion of cognitive reserve, social isolation, environmental deafferentation or a combination of these pathways.Reference Lin, Ferrucci, Metter, An, Zonderman and Resnick60 Studies have shown that in cases where auditory perception is difficult (i.e. hearing loss), greater cognitive resources are dedicated to auditory processing mechanisms rather than other cognitive processes, such as memory.Reference Tun, McCoy and Wingfield77,Reference Pichora-Fuller, Schneider and Daneman78 In a continually increasing aging population, this has obvious implications for health policy and social care services, aiming towards prevention, early diagnosis and treatment.

Brief cognitive assessments (such as Montreal Cognitive Assessment and Mini Mental State Examination) can successfully detect mild cognitive impairment in primary care, although their sensitivity is not as high as for established dementia.Reference Langa and Levine79 There might be a role for routine cognitive assessment for people who present with hearing loss in an audiology clinic. Similarly, a referral for hearing assessment might be in the patient's best interest when they are diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment in primary care. Early intervention to address both issues might prove crucial in improving quality of life and reducing morbidity associated with hearing loss and dementia. Prospective cohort studies need to investigate whether early diagnosis of cognitive impairment improves important patient or caregiver outcomes.Reference Langa and Levine79 Moreover, it is not yet known whether prompt hearing rehabilitation prevents cognitive decline. Future research should focus on identifying the underlying mechanisms linking hearing loss with dementia and developing rehabilitation strategies to delay or prevent its occurrence.

Conclusion

Most of the studies included in this systematic review observed a significant association between hearing loss and incident mild cognitive impairment. It is important for clinicians to be aware of this association and allow for early detection and intervention to try and delay onset of dementia. Further research investigating the mechanisms of this observed association and whether prompt hearing rehabilitation alters the natural course of this relationship should be the focus of future research.

Competing interests

None declared

Appendix 1. Search Strategy, performed on 24 June 2020

Search Terms:

(Deafness OR Hearing Or Presbycusis) AND (Mild Cognitive Impairment OR MCI)

Filters:

Text Availability: Full Text

Species: Humans

Languages: English