1. Introduction

Starting from the seminal work of Nikuradse (Reference Nikuradse1931), turbulent flows over rough surfaces have been commonly studied in the presence of statistically homogeneous roughness. The drag penalty induced by the imperfections of the surface is reflected in a vertical shift of the universal logarithmic velocity profile, which can be readily calculated from the equivalent sand-grain roughness (see, for instance, the review by Chung et al. Reference Chung, Hutchins, Schultz and Flack2021). The equivalent roughness is in turn a hydraulic quantity whose a priori calculation from the roughness topology is the subject of ongoing research (e.g. Flack & Schultz Reference Flack and Schultz2010; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Stroh, Lee, Bagheri, Frohnapfel and Forooghi2023).

However, naturally occurring rough surfaces (such as that generated by the deposition of dirt, ice or organic matter over the surface of a vehicle) can rarely be regarded as homogeneous, so that the effect they have on the flow is more complex than a vertical shift of the velocity profile. For example, Mejia-Alvarez et al. (Reference Mejia-Alvarez, Barros, Christensen, Vendetti, Best, Church and Hardy2013) have inspected the roughness generated on a turbine blade by deposition of foreign materials, finding that it contained randomly distributed elements of different scales. The flow over such a multi-scale roughness has been experimentally investigated in a boundary layer wind tunnel (Mejia-Alvarez & Christensen Reference Mejia-Alvarez and Christensen2013; Barros & Christensen Reference Barros and Christensen2014). It has been found that the ensemble-averaged velocity field is highly heterogeneous as it contains coherent regions of low and high momentum (low and high momentum pathways); these occur in the absence of obvious geometric features (e.g. ridges). As a note of caution, it is worth highlighting that the rough surface used in the mentioned studies was manufactured by aligning several identical rough plates; this creates a large-scale regularity in the surface that might favour the formation and sustainment of the observed momentum pathways. The pathways have an

![]() $h$

-scaled extent in the streamwise and wall-normal direction, where

$h$

-scaled extent in the streamwise and wall-normal direction, where

![]() $h$

is the outer length scale (the boundary layer thickness for the studies mentioned here). Nikora et al. (Reference Nikora, Stoesser, Cameron, Stewart, Papadopoulos, Ouro, McSherry, Zampiron, Marusic and Falconer2019) observed similar coherent motions over multi-scale roughness in open channel flows, finding that the pathways provide a contribution to skin friction that adds up to the direct effect of roughness. Comparable low- and high-momentum pathways were found both experimentally (Womack et al. Reference Womack, Volino, Meneveau and Schultz2022) and numerically (Kaminaris et al. Reference Kaminaris, Balaras, Schultz and Volino2023) by studying the turbulent flow over a random distribution of truncated conical roughness elements resembling the barnacles that accumulate on ship hulls. These pathways extend for at least

$h$

is the outer length scale (the boundary layer thickness for the studies mentioned here). Nikora et al. (Reference Nikora, Stoesser, Cameron, Stewart, Papadopoulos, Ouro, McSherry, Zampiron, Marusic and Falconer2019) observed similar coherent motions over multi-scale roughness in open channel flows, finding that the pathways provide a contribution to skin friction that adds up to the direct effect of roughness. Comparable low- and high-momentum pathways were found both experimentally (Womack et al. Reference Womack, Volino, Meneveau and Schultz2022) and numerically (Kaminaris et al. Reference Kaminaris, Balaras, Schultz and Volino2023) by studying the turbulent flow over a random distribution of truncated conical roughness elements resembling the barnacles that accumulate on ship hulls. These pathways extend for at least

![]() $18h$

(Womack et al. Reference Womack, Volino, Meneveau and Schultz2022) in the streamwise direction; the position at which they occur is reproducible across different repetitions of the same experiment. Also, high- and low- momentum pathways of an

$18h$

(Womack et al. Reference Womack, Volino, Meneveau and Schultz2022) in the streamwise direction; the position at which they occur is reproducible across different repetitions of the same experiment. Also, high- and low- momentum pathways of an

![]() $h$

-scaled spanwise period were observed by Reynolds et al. (Reference Reynolds, Hayden, Castro and Robins2007) in a boundary layer evolving over an array of staggered cubic roughness elements. In this last case, however, the spanwise period of the momentum pattern increased with streamwise fetch in an almost quantised manner.

$h$

-scaled spanwise period were observed by Reynolds et al. (Reference Reynolds, Hayden, Castro and Robins2007) in a boundary layer evolving over an array of staggered cubic roughness elements. In this last case, however, the spanwise period of the momentum pattern increased with streamwise fetch in an almost quantised manner.

There is no consensus over what triggers the formation of these momentum pathways. Kaminaris et al. (Reference Kaminaris, Balaras, Schultz and Volino2023) found that the spanwise topology of the pathways correlates well with that of the leading edge of the roughness (that is, the first row of roughness elements stretching over the spanwise direction). They went on to show that the pathways are effectively triggered by the leading edge, and persist for a finite distance downstream of it regardless of whether they evolve over a smooth or a rough surface. Conversely, Barros & Christensen (Reference Barros and Christensen2014) found a local correlation between the roughness topology and the pathways, suggesting that the pathways originate from heterogeneity in the roughness properties in a similar way to secondary motions over spanwise heterogeneous roughness. It is unclear which of these two mechanisms is dominant; it cannot be excluded that both contribute to the formation of the pathways. Nevertheless, there is a close resemblance between the pathways and secondary motions observed over spanwise heterogeneous roughness (as we will discuss below), to the point that the pathways themselves are also referred to as secondary motions. Both the pathways and the secondary motions, in turn, have often been linked to the naturally occurring very-large-scale motions (VLSMs; see, for instance, Kim & Adrian Reference Kim and Adrian1999; Hutchins & Marusic Reference Hutchins and Marusic2007a ; Lee & Moser Reference Lee and Moser2018) seen in turbulent wall-bounded flows.

Spanwise heterogeneous roughness is usually studied in terms of spanwise-alternating streamwise-elongated strips with different roughness properties (Hinze Reference Hinze1967; Nugroho et al. Reference Nugroho, Hutchins and Monty2013; Turk et al. Reference Türk, Daschiel, Stroh, Hasegawa and Frohnapfel2014; Willingham et al. Reference Willingham, Anderson, Christensen and Barros2014; Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Barros, Christensen and Awasthi2015; Stroh et al. Reference Stroh, Hasegawa, Kriegseis and Frohnapfel2016; Vanderwel et al. Reference Vanderwel, Stroh, Kriegseis, Frohnapfel and Ganapathisubramani2019; Stroh et al. Reference Stroh, Schäfer, Frohnapfel and Forooghi2020; Frohnapfel et al. Reference Frohnapfel, Von Deyn, Yang, Neuhauser, Stroh, Örlü and Gatti2024). The strip width is typically indicated by

![]() $s$

; notice that this is half the period

$s$

; notice that this is half the period

![]() $\Lambda _s$

of the spanwise roughness pattern. The roughness pattern induces secondary motions; as long as the strips are narrow (

$\Lambda _s$

of the spanwise roughness pattern. The roughness pattern induces secondary motions; as long as the strips are narrow (

![]() $s \leqslant h$

), the secondary motions consist in high- and low- momentum pathways flanked by cross-sectional circulatory motions (for instance, Chung et al. Reference Chung, Monty and Hutchins2018). The same topology has been observed for the pathways occurring over multi-scale roughness (Barros & Christensen Reference Barros and Christensen2014; Nikora et al. Reference Nikora, Stoesser, Cameron, Stewart, Papadopoulos, Ouro, McSherry, Zampiron, Marusic and Falconer2019). Conditional views of VLSMs (Hutchins & Marusic Reference Hutchins and Marusic2007b

; Hwang et al. Reference Hwang, Lee, Sung and Zaki2016) also share the same geometry, the main difference being that VLSMs occur at random spanwise positions whereas the position of secondary motions is based on the roughness topology. It has been proposed that momentum pathways and secondary motions originate as the geometric or roughness features at the wall provide a preferential spawning position for VLSMs (Mejia-Alvarez & Christensen Reference Mejia-Alvarez and Christensen2013; Chung et al. Reference Chung, Monty and Hutchins2018; Wangsawijaya & Hutchins Reference Wangsawijaya and Hutchins2022). This view is corroborated by the observation that randomly occurring VLSMs do not coexist with fixed-position secondary motions of comparable size (

$s \leqslant h$

), the secondary motions consist in high- and low- momentum pathways flanked by cross-sectional circulatory motions (for instance, Chung et al. Reference Chung, Monty and Hutchins2018). The same topology has been observed for the pathways occurring over multi-scale roughness (Barros & Christensen Reference Barros and Christensen2014; Nikora et al. Reference Nikora, Stoesser, Cameron, Stewart, Papadopoulos, Ouro, McSherry, Zampiron, Marusic and Falconer2019). Conditional views of VLSMs (Hutchins & Marusic Reference Hutchins and Marusic2007b

; Hwang et al. Reference Hwang, Lee, Sung and Zaki2016) also share the same geometry, the main difference being that VLSMs occur at random spanwise positions whereas the position of secondary motions is based on the roughness topology. It has been proposed that momentum pathways and secondary motions originate as the geometric or roughness features at the wall provide a preferential spawning position for VLSMs (Mejia-Alvarez & Christensen Reference Mejia-Alvarez and Christensen2013; Chung et al. Reference Chung, Monty and Hutchins2018; Wangsawijaya & Hutchins Reference Wangsawijaya and Hutchins2022). This view is corroborated by the observation that randomly occurring VLSMs do not coexist with fixed-position secondary motions of comparable size (

![]() $s/h \approx 1$

, Barros & Christensen Reference Barros and Christensen2019; Zampiron et al. Reference Zampiron, Cameron and Nikora2020; Schäfer Reference Schäfer2023). Moreover, both VLSMs and secondary motions have been found to meander about their spawning position, although the associated streamwise periods are slightly different (Hutchins & Marusic Reference Hutchins and Marusic2007a

; Kevin et al. Reference Kevin, Monty, Bai, Pathikonda, Nugroho, Barros, Christensen and Hutchins2017, Reference Kevin, Monty and Hutchins2019; Vanderwel et al. Reference Vanderwel, Stroh, Kriegseis, Frohnapfel and Ganapathisubramani2019; Wangsawijaya & Hutchins Reference Wangsawijaya and Hutchins2022). Another difference is given by the fact that VLSMs are typically observed in the log-layer, whereas secondary motions of comparable size extend to the wake region (Wangsawijaya et al. Reference Wangsawijaya, Baidya, Chung, Marusic and Hutchins2020).

$s/h \approx 1$

, Barros & Christensen Reference Barros and Christensen2019; Zampiron et al. Reference Zampiron, Cameron and Nikora2020; Schäfer Reference Schäfer2023). Moreover, both VLSMs and secondary motions have been found to meander about their spawning position, although the associated streamwise periods are slightly different (Hutchins & Marusic Reference Hutchins and Marusic2007a

; Kevin et al. Reference Kevin, Monty, Bai, Pathikonda, Nugroho, Barros, Christensen and Hutchins2017, Reference Kevin, Monty and Hutchins2019; Vanderwel et al. Reference Vanderwel, Stroh, Kriegseis, Frohnapfel and Ganapathisubramani2019; Wangsawijaya & Hutchins Reference Wangsawijaya and Hutchins2022). Another difference is given by the fact that VLSMs are typically observed in the log-layer, whereas secondary motions of comparable size extend to the wake region (Wangsawijaya et al. Reference Wangsawijaya, Baidya, Chung, Marusic and Hutchins2020).

One additional common property of naturally occurring VLSMs and the pathways or secondary motions is that they are often observed to have a characteristic spanwise length scale of the order of

![]() $1h$

. The typical spanwise scale of VLSMs occurring over smooth walls is indeed

$1h$

. The typical spanwise scale of VLSMs occurring over smooth walls is indeed

![]() $1-4\,h$

(Lee & Moser Reference Lee and Moser2018), although their size is flow dependent. The momentum pathways found over multi-scale and randomly distributed roughness are also

$1-4\,h$

(Lee & Moser Reference Lee and Moser2018), although their size is flow dependent. The momentum pathways found over multi-scale and randomly distributed roughness are also

![]() $h$

-spaced in the spanwise direction (as can be seen from the data of Reynolds et al. Reference Reynolds, Hayden, Castro and Robins2007; Barros & Christensen Reference Barros and Christensen2014; Womack et al. Reference Womack, Volino, Meneveau and Schultz2022). Secondary motions induced by a spanwise roughness pattern are most energetic when the strip spacing

$h$

-spaced in the spanwise direction (as can be seen from the data of Reynolds et al. Reference Reynolds, Hayden, Castro and Robins2007; Barros & Christensen Reference Barros and Christensen2014; Womack et al. Reference Womack, Volino, Meneveau and Schultz2022). Secondary motions induced by a spanwise roughness pattern are most energetic when the strip spacing

![]() $s$

is of the order of

$s$

is of the order of

![]() $h$

(Vanderwel & Ganapathisubramani Reference Vanderwel and Ganapathisubramani2015; Medjnoun et al. Reference Medjnoun, Vanderwel and Ganapathisubramani2018; Wangsawijaya et al. Reference Medjnoun, Vanderwel and Ganapathisubramani2020); as the strip spacing is increased to larger values (

$h$

(Vanderwel & Ganapathisubramani Reference Vanderwel and Ganapathisubramani2015; Medjnoun et al. Reference Medjnoun, Vanderwel and Ganapathisubramani2018; Wangsawijaya et al. Reference Medjnoun, Vanderwel and Ganapathisubramani2020); as the strip spacing is increased to larger values (

![]() $s \gg h$

), the secondary motions stop growing in size and rather remain confined to an

$s \gg h$

), the secondary motions stop growing in size and rather remain confined to an

![]() $h$

-wide region around roughness transitions.

$h$

-wide region around roughness transitions.

There are at least two possible explanations for the frequent observation of dominant

![]() $h$

-scaled features in turbulent flows; they are not necessarily mutually exclusive. The study of the linearised Navier–Stokes equations in wall-bounded flows has revealed that the perturbations they amplify the most are either inner- or

$h$

-scaled features in turbulent flows; they are not necessarily mutually exclusive. The study of the linearised Navier–Stokes equations in wall-bounded flows has revealed that the perturbations they amplify the most are either inner- or

![]() $h$

-scaled in the spanwise direction (Del Álamo & Jiménez Reference Del Álamo and Jiménez2006; Cossu et al. Reference Cossu, Pujals and Depardon2009; Alizard et al. Reference Alizard, Pirozzoli, Bernardini and Grasso2015). Large-scaled perturbations evolve into structures reminiscent of the conditional views of VLSMs, of secondary motions and of the momentum pathways flanked by rolling motions, although linear analysis tends to overestimate the spanwise wavelength of these features (Alizard et al. Reference Alizard, Pirozzoli, Bernardini and Grasso2015). Similar results have been found by searching the volume forcing mode that is most amplified by the linearised Navier–Stokes equations (Hwang & Cossu Reference Hwang and Cossu2010; Illingworth Reference Illingworth2020). In light of these linear amplification mechanisms, then, the phenomenology described above can be explained as follows. A broadband disturbance (as a velocity perturbation or a volume force) is provided either by nonlinear interactions between small scales or by the roughness topology; the flow then acts to selectively amplify disturbances of a particular

$h$

-scaled in the spanwise direction (Del Álamo & Jiménez Reference Del Álamo and Jiménez2006; Cossu et al. Reference Cossu, Pujals and Depardon2009; Alizard et al. Reference Alizard, Pirozzoli, Bernardini and Grasso2015). Large-scaled perturbations evolve into structures reminiscent of the conditional views of VLSMs, of secondary motions and of the momentum pathways flanked by rolling motions, although linear analysis tends to overestimate the spanwise wavelength of these features (Alizard et al. Reference Alizard, Pirozzoli, Bernardini and Grasso2015). Similar results have been found by searching the volume forcing mode that is most amplified by the linearised Navier–Stokes equations (Hwang & Cossu Reference Hwang and Cossu2010; Illingworth Reference Illingworth2020). In light of these linear amplification mechanisms, then, the phenomenology described above can be explained as follows. A broadband disturbance (as a velocity perturbation or a volume force) is provided either by nonlinear interactions between small scales or by the roughness topology; the flow then acts to selectively amplify disturbances of a particular

![]() $h$

-scaled set of wavelengths to yield the observed VLSMs or momentum pathways. The plausibility of this hypothesis is corroborated by evidence that channel flows are particularly sensitive to spanwise disturbances at the wall (Jovanović & Bamieh Reference Jovanović and Bamieh2005). An alternative, yet similar, explanation is provided by Townsend (Reference Townsend1976, chap. 7.19) in an attempt to explain the persistence of some

$h$

-scaled set of wavelengths to yield the observed VLSMs or momentum pathways. The plausibility of this hypothesis is corroborated by evidence that channel flows are particularly sensitive to spanwise disturbances at the wall (Jovanović & Bamieh Reference Jovanović and Bamieh2005). An alternative, yet similar, explanation is provided by Townsend (Reference Townsend1976, chap. 7.19) in an attempt to explain the persistence of some

![]() $h$

-scaled perturbations often seen in wind tunnels. Using suited approximations, Townsend estimated that spanwise variations of the wall-shear stress whose characteristic wavelength falls in a limited (

$h$

-scaled perturbations often seen in wind tunnels. Using suited approximations, Townsend estimated that spanwise variations of the wall-shear stress whose characteristic wavelength falls in a limited (

![]() $\leqslant 4 h$

)

$\leqslant 4 h$

)

![]() $h$

-scaled range should be able to self-sustain and thus dominate the remaining flow features. It is then conceivable (as pointed out by Wangsawijaya et al. Reference Wangsawijaya, Baidya, Chung, Marusic and Hutchins2020) that a broadband perturbation could trigger a set of motions of different scales, of which some

$h$

-scaled range should be able to self-sustain and thus dominate the remaining flow features. It is then conceivable (as pointed out by Wangsawijaya et al. Reference Wangsawijaya, Baidya, Chung, Marusic and Hutchins2020) that a broadband perturbation could trigger a set of motions of different scales, of which some

![]() $h$

-scaled ones would outlive the others to yield VLSMs or the

$h$

-scaled ones would outlive the others to yield VLSMs or the

![]() $h$

-scaled momentum pathways.

$h$

-scaled momentum pathways.

The aim of this article is to measure the persistence in time of secondary motions of different sizes once the external factors that trigger their appearance and allow for their sustainment are removed. In particular, we consider secondary motions induced by spanwise roughness patterns of different periods. This is done both in an attempt to assess the plausibility of Townsend’s estimates and to investigate the streamwise-extended secondary motions observed over a smooth wall in the wake of roughness features (Kaminaris et al. Reference Kaminaris, Balaras, Schultz and Volino2023). In § 2, we explain our numerical procedure: secondary motions extracted from a steady-state flow over heterogeneous roughness are allowed to evolve in time in a channel flow with smooth walls until they decay. The theoretical framework underlying the analyses presented in this paper is then presented in § 3. An overview of the fully developed steady-state secondary motions is given in § 4; their time evolution is then tracked (§ 5) through an ensemble-average of multiple realisations of the same simulation. For completeness, we also briefly show the time evolution of near-wall streamwise fluctuations in § 6. A concluding discussion is given in § 7.

2. Problem statement and numerical method

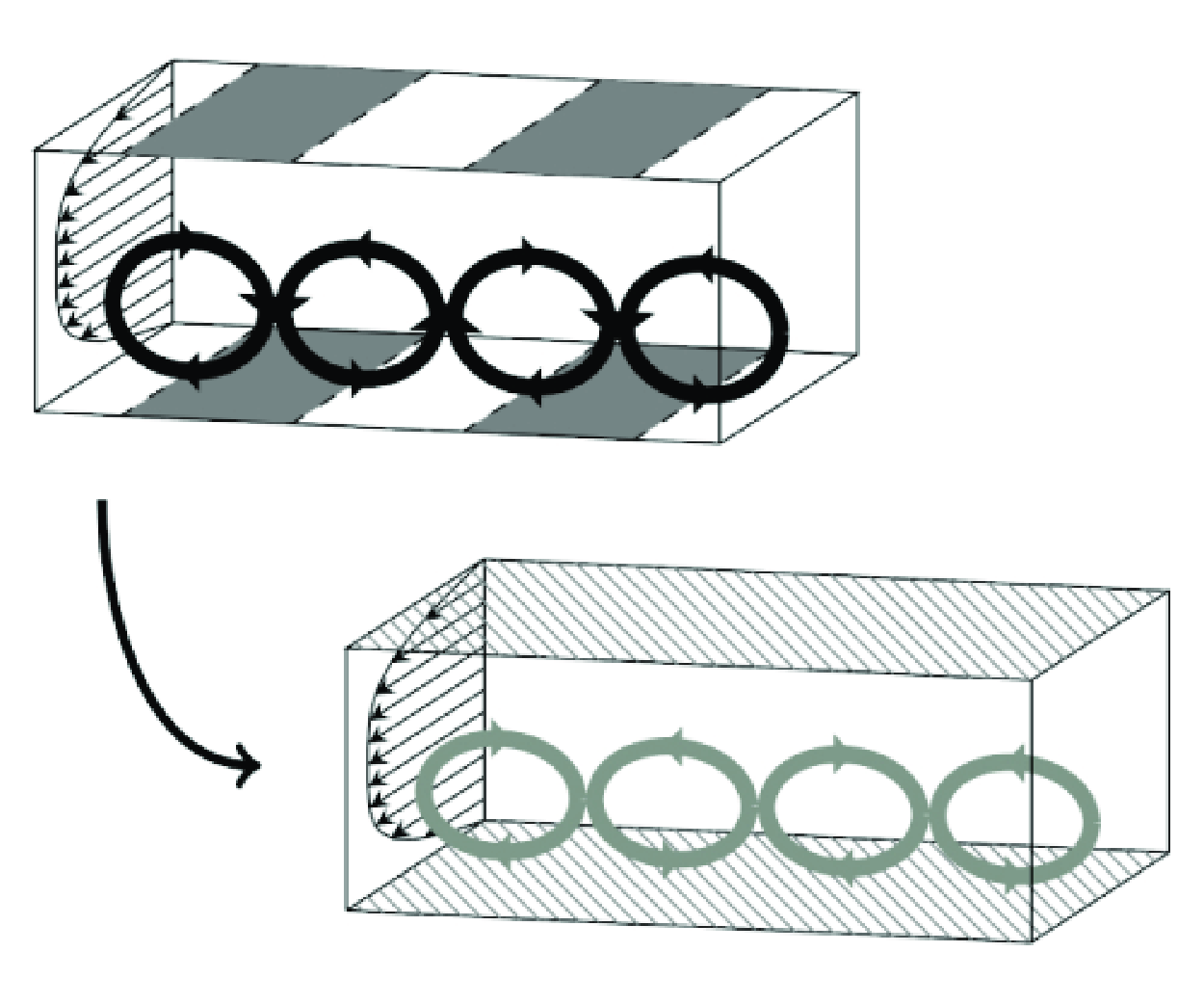

Figure 1. Schematic problem description with a graphical representation of secondary motions. The initial condition (

![]() $t=0$

) of our numerical set-up is shown in panel (a): steady-state secondary motions are observed over strip-type roughness. A generic point

$t=0$

) of our numerical set-up is shown in panel (a): steady-state secondary motions are observed over strip-type roughness. A generic point

![]() $t$

in time (with

$t$

in time (with

![]() $t\gt 0$

) is depicted in panel (b): the secondary motions decay as they evolve over a smooth wall. Box size not to scale. Adapted from Neuhauser et al. (Reference Neuhauser, Schäfer, Gatti and Frohnapfel2022).

$t\gt 0$

) is depicted in panel (b): the secondary motions decay as they evolve over a smooth wall. Box size not to scale. Adapted from Neuhauser et al. (Reference Neuhauser, Schäfer, Gatti and Frohnapfel2022).

We perform direct numerical simulation (DNS) of incompressible channel flows at constant pressure gradient (CPG). The peculiarity of this dataset is that the simulations capture the decay of secondary motions of different sizes; this process is clearly not at a statistically steady state. Rather, our simulations describe the transition from a statistically steady state (flow with secondary motions) to a second steady state (flow in a smooth channel). To still be able to compute averages, each simulation is then run several times, each time starting from a different realisation of a given statistically steady state. Ensemble averages are then calculated.

The channel geometry is shown in figure 1. Let

![]() $x$

,

$x$

,

![]() $y$

,

$y$

,

![]() $z$

be the streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise directions;

$z$

be the streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise directions;

![]() $u$

,

$u$

,

![]() $v$

,

$v$

,

![]() $w$

are the corresponding components of the velocity vector

$w$

are the corresponding components of the velocity vector

![]() $\boldsymbol {u}$

. The flow is periodic in the streamwise and spanwise directions (periodic boundary conditions); the corresponding periods are indicated as

$\boldsymbol {u}$

. The flow is periodic in the streamwise and spanwise directions (periodic boundary conditions); the corresponding periods are indicated as

![]() $L_x$

and

$L_x$

and

![]() $L_z$

, respectively. The flow is statistically homogeneous in the streamwise direction, but not in the spanwise one: indeed, as will be discussed below, a spanwise-heterogeneous (but streamwise-homogeneous) roughness pattern at the wall induces spanwise-heterogeneities of the average flow velocity.

$L_z$

, respectively. The flow is statistically homogeneous in the streamwise direction, but not in the spanwise one: indeed, as will be discussed below, a spanwise-heterogeneous (but streamwise-homogeneous) roughness pattern at the wall induces spanwise-heterogeneities of the average flow velocity.

Time is indicated by

![]() $t$

. At

$t$

. At

![]() $t=0$

, the flow is at a statistically steady state in the presence of secondary motions. These are sustained by a spanwise roughness pattern consisting in alternating streamwise-elongated strips of smooth and rough wall. We will refer to this set-up as strip-type roughness. The spanwise width of each strip is

$t=0$

, the flow is at a statistically steady state in the presence of secondary motions. These are sustained by a spanwise roughness pattern consisting in alternating streamwise-elongated strips of smooth and rough wall. We will refer to this set-up as strip-type roughness. The spanwise width of each strip is

![]() $s$

; the spanwise period of the pattern is

$s$

; the spanwise period of the pattern is

![]() $\Lambda _s = 2s$

. For

$\Lambda _s = 2s$

. For

![]() $t\gt 0$

, the spanwise roughness pattern is suddenly replaced by a smooth wall, so that the decay of the secondary motions is observed. The pressure gradient is kept constant in the process.

$t\gt 0$

, the spanwise roughness pattern is suddenly replaced by a smooth wall, so that the decay of the secondary motions is observed. The pressure gradient is kept constant in the process.

Notice, once again, that the flow is streamwise-homogeneous. As the strip-type roughness is removed from the walls, the flow departs from its steady state, but retains its streamwise homogeneity. In other words, the flow develops temporally, but not in the streamwise direction. Our present approach is thus similar to that of Toh & Itano (Reference Toh and Itano2005), in the sense that we investigate the time evolution of streamwise-invariant flow structures. Notice, moreover, that an increase of the bulk velocity is observed as a result of the removal of the strip-type roughness: as the pressure gradient is kept constant, the reduction in skin friction at the wall leads to an increase of the flow rate. Mass is conserved throughout the process: owing to the present geometry, conservation of mass only requires the average flow velocity to be streamwise-invariant, so that time variations of the flow rate are admissible.

Owing to the instationarity and spanwise heterogeneity of the problem, care must be exerted when defining averaging operators and viscous units. The operator

![]() $ \langle {\cdot } \rangle$

indicates the expected value and is computed as an average over multiple repetitions of the same simulation, over the streamwise direction and over multiple spanwise periods of the selected geometry (phase average, see Reynolds & Hussain Reference Reynolds and Hussain1972); known symmetries in the wall-normal and spanwise directions are used to improve convergence wherever possible. The resulting statistics depend on the conditioned spanwise variable

$ \langle {\cdot } \rangle$

indicates the expected value and is computed as an average over multiple repetitions of the same simulation, over the streamwise direction and over multiple spanwise periods of the selected geometry (phase average, see Reynolds & Hussain Reference Reynolds and Hussain1972); known symmetries in the wall-normal and spanwise directions are used to improve convergence wherever possible. The resulting statistics depend on the conditioned spanwise variable

![]() $\zeta$

and time, as well as on the wall-normal coordinate

$\zeta$

and time, as well as on the wall-normal coordinate

![]() $y$

. If an additional spanwise average is performed, the symbol

$y$

. If an additional spanwise average is performed, the symbol

![]() $ \langle {\cdot } \rangle _z$

is used. As for inner units, the expected value

$ \langle {\cdot } \rangle _z$

is used. As for inner units, the expected value

![]() $\tau _w(t,\zeta )$

of the wall shear stress is a function of time and of the spanwise coordinate. So are the friction velocity

$\tau _w(t,\zeta )$

of the wall shear stress is a function of time and of the spanwise coordinate. So are the friction velocity

![]() $u_\tau (t,\zeta ) = \sqrt {\tau _w/\rho }$

and the viscous length scale

$u_\tau (t,\zeta ) = \sqrt {\tau _w/\rho }$

and the viscous length scale

![]() $\delta _{v}(t,\zeta ) = \nu /u_\tau$

, where

$\delta _{v}(t,\zeta ) = \nu /u_\tau$

, where

![]() $\rho$

is the density and

$\rho$

is the density and

![]() $\nu$

the kinematic viscosity. For the calculation of the worst-case inner-scaled grid spacing, the maximum value

$\nu$

the kinematic viscosity. For the calculation of the worst-case inner-scaled grid spacing, the maximum value

![]() $u_{\tau ,m}$

of the friction velocity can be used:

$u_{\tau ,m}$

of the friction velocity can be used:

Leveraging the fact that the pressure gradient

![]() $-G,\,G\gt 0$

is forcedly kept constant during our simulations, a global friction velocity

$-G,\,G\gt 0$

is forcedly kept constant during our simulations, a global friction velocity

![]() $u_p$

and length scale

$u_p$

and length scale

![]() $\delta _{p}$

can also be defined:

$\delta _{p}$

can also be defined:

\begin{equation} u_p = \sqrt {\frac {hG}{\rho }};\,\,\,\,\,\,\delta _{p} = \frac {\nu }{u_p}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} u_p = \sqrt {\frac {hG}{\rho }};\,\,\,\,\,\,\delta _{p} = \frac {\nu }{u_p}. \end{equation}

Quantities scaled with these global viscous units will be indicated with a

![]() $(\cdot )^+$

superscript. They are also used for the definition of the friction Reynolds number

$(\cdot )^+$

superscript. They are also used for the definition of the friction Reynolds number

![]() $Re_\tau =hu_p/\nu$

. The relation between global and local viscous units can be found by integrating the streamwise momentum balance of the Navier–Stokes equations. By defining the bulk velocity as the volume-average of the expected streamwise component,

$Re_\tau =hu_p/\nu$

. The relation between global and local viscous units can be found by integrating the streamwise momentum balance of the Navier–Stokes equations. By defining the bulk velocity as the volume-average of the expected streamwise component,

the following relation is obtained:

Under steady conditions (

![]() $t=0$

and

$t=0$

and

![]() $t\to \infty$

for the problem considered here), the global

$t\to \infty$

for the problem considered here), the global

![]() $u_p$

is the friction velocity built by using the spanwise average

$u_p$

is the friction velocity built by using the spanwise average

![]() $ \langle {\tau _w} \rangle _z$

instead of

$ \langle {\tau _w} \rangle _z$

instead of

![]() $\tau _w$

in its definition:

$\tau _w$

in its definition:

\begin{align} u_p = \sqrt {\frac {\left \langle {\tau _w} \right \rangle _z}{\rho }}\,\,\,\,\,\,\text {only at a steady state.} \end{align}

\begin{align} u_p = \sqrt {\frac {\left \langle {\tau _w} \right \rangle _z}{\rho }}\,\,\,\,\,\,\text {only at a steady state.} \end{align}

2.1. Numerical method and details

We perform DNS using the open-source solver Xcompact3d (Laizet & Lamballais Reference Laizet and Lamballais2009; Laizet & Li Reference Laizet and Li2011; Bartholomew et al. Reference Bartholomew, Deskos, Frantz, Schuch, Lamballais and Laizet2020), using sixth-order compact finite differences in space combined with an explicit third-order Runge–Kutta scheme in time. We test different configurations for varying

![]() $\Lambda _s$

at two different friction Reynolds numbers (

$\Lambda _s$

at two different friction Reynolds numbers (

![]() $Re_\tau =180$

and

$Re_\tau =180$

and

![]() $Re_\tau =500$

). While the streamwise extent

$Re_\tau =500$

). While the streamwise extent

![]() $L_x$

of the simulation domain is set to values that are greater or equal to those used by Neuhauser et al. (Reference Neuhauser, Schäfer, Gatti and Frohnapfel2022) for analogous simulations, the spanwise box size

$L_x$

of the simulation domain is set to values that are greater or equal to those used by Neuhauser et al. (Reference Neuhauser, Schäfer, Gatti and Frohnapfel2022) for analogous simulations, the spanwise box size

![]() $L_z$

is set alternatively to

$L_z$

is set alternatively to

![]() $12h$

,

$12h$

,

![]() $8h$

or

$8h$

or

![]() $6h$

to accomodate an integer, even number of strips for each of the tested values of

$6h$

to accomodate an integer, even number of strips for each of the tested values of

![]() $\Lambda _s$

. The

$\Lambda _s$

. The

![]() $L_z=6h$

box size is preferred at high-

$L_z=6h$

box size is preferred at high-

![]() $Re$

wherever possible to minimise the computational load of a single simulation.

$Re$

wherever possible to minimise the computational load of a single simulation.

Our data production pipeline consists of two stages. First, initial conditions are produced by simulating a channel flow with a spanwise roughness pattern of period

![]() $\Lambda _s$

(see figure 1

a). Rough wall sections are modelled by imposing a slip length

$\Lambda _s$

(see figure 1

a). Rough wall sections are modelled by imposing a slip length

![]() $\ell$

for the spanwise velocity component at the wall as done by Neuhauser et al. (Reference Neuhauser, Schäfer, Gatti and Frohnapfel2022). This results in the following Robin boundary condition:

$\ell$

for the spanwise velocity component at the wall as done by Neuhauser et al. (Reference Neuhauser, Schäfer, Gatti and Frohnapfel2022). This results in the following Robin boundary condition:

where the

![]() $(\cdot )_w$

subscript indicates a quantity evaluated at the wall,

$(\cdot )_w$

subscript indicates a quantity evaluated at the wall,

![]() $\hat {n}_{w}$

a unit vector that is orthogonal to the wall and pointing into the fluid. The value of the slip length is set to

$\hat {n}_{w}$

a unit vector that is orthogonal to the wall and pointing into the fluid. The value of the slip length is set to

![]() $\ell ^+ = 9$

following Neuhauser et al. (Reference Neuhauser, Schäfer, Gatti and Frohnapfel2022). After the simulation reaches a steady state, a set of

$\ell ^+ = 9$

following Neuhauser et al. (Reference Neuhauser, Schäfer, Gatti and Frohnapfel2022). After the simulation reaches a steady state, a set of

![]() $N_s$

snapshots is stored; the sample time is set to

$N_s$

snapshots is stored; the sample time is set to

![]() $1 h/u_p$

to ensure that snapshots are reasonably uncorrelated. As previously explained,

$1 h/u_p$

to ensure that snapshots are reasonably uncorrelated. As previously explained,

![]() $u_p$

is analogous to

$u_p$

is analogous to

![]() $u_\tau$

; then, if

$u_\tau$

; then, if

![]() $h$

is the maximum height of an attached eddy, its lifetime can be expected to be of the order of the eddy turnover time

$h$

is the maximum height of an attached eddy, its lifetime can be expected to be of the order of the eddy turnover time

![]() $1 h/u_p$

(see, e.g., Lozano-Durán & Jiménez Reference Lozano-Durán and Jiménez2014). One can then expect that the turbulent features observed in a given snapshot differ from those of the successive snapshot saved after

$1 h/u_p$

(see, e.g., Lozano-Durán & Jiménez Reference Lozano-Durán and Jiménez2014). One can then expect that the turbulent features observed in a given snapshot differ from those of the successive snapshot saved after

![]() $1 h/u_p$

.

$1 h/u_p$

.

Each of the

![]() $N_s$

saved snapshots of the secondary motions is used as the initial condition for a second simulation between smooth walls (see figure 1

b). The duration of the simulation

$N_s$

saved snapshots of the secondary motions is used as the initial condition for a second simulation between smooth walls (see figure 1

b). The duration of the simulation

![]() $T_f$

is chosen to satisfactorily capture the decay of the secondary motions. Streamwise-averaged flow fields are stored every

$T_f$

is chosen to satisfactorily capture the decay of the secondary motions. Streamwise-averaged flow fields are stored every

![]() $0.01 h/u_p$

, even though a laxer time resolution could have been used in retrospect. Streamwise-averaged velocity fields are preferred to three-dimensional snapshots as the present procedure is particularly data intensive. Exploiting the several repetitions of the simulation, a total of

$0.01 h/u_p$

, even though a laxer time resolution could have been used in retrospect. Streamwise-averaged velocity fields are preferred to three-dimensional snapshots as the present procedure is particularly data intensive. Exploiting the several repetitions of the simulation, a total of

![]() $N_s$

fields at the same time

$N_s$

fields at the same time

![]() $t$

from the initial conditions are averaged together to produce an ensemble-average of the decaying secondary motions. The whole procedure is repeated for different values of

$t$

from the initial conditions are averaged together to produce an ensemble-average of the decaying secondary motions. The whole procedure is repeated for different values of

![]() $\Lambda _s$

and

$\Lambda _s$

and

![]() $Re_\tau$

.

$Re_\tau$

.

Table 1. Numerical details for all tested combinations of

![]() $\Lambda _s/h$

(the spanwise period of the roughness pattern) and

$\Lambda _s/h$

(the spanwise period of the roughness pattern) and

![]() $Re_\tau$

for our smooth (steady) and time-evolving simulations. The number of fields used to calculate statistics is indicated by

$Re_\tau$

for our smooth (steady) and time-evolving simulations. The number of fields used to calculate statistics is indicated by

![]() $N_0=N_s$

(where

$N_0=N_s$

(where

![]() $N_0$

refers to steady-state simulations,

$N_0$

refers to steady-state simulations,

![]() $N_s$

to time-evolving ones).

$N_s$

to time-evolving ones).

![]() $T_f$

indicates the time duration of the decaying simulation,

$T_f$

indicates the time duration of the decaying simulation,

![]() $L_x$

and

$L_x$

and

![]() $L_z$

refer to the simulation box size in the streamwise and spanwise directions; the grid spacing is uniform in these two directions and is indicated by

$L_z$

refer to the simulation box size in the streamwise and spanwise directions; the grid spacing is uniform in these two directions and is indicated by

![]() $\Delta x$

,

$\Delta x$

,

![]() $\Delta z$

respectively. The wall-normal grid spacings at the wall and centreline are instead indicated by

$\Delta z$

respectively. The wall-normal grid spacings at the wall and centreline are instead indicated by

![]() $\Delta y_w$

and

$\Delta y_w$

and

![]() $\Delta y_c$

. The maximum in time, over each grid point and over the three spatial directions (or velocity components) of the Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy (

$\Delta y_c$

. The maximum in time, over each grid point and over the three spatial directions (or velocity components) of the Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy (

![]() $\text {CFL} = V\Delta t/q$

, where

$\text {CFL} = V\Delta t/q$

, where

![]() $\Delta t$

is the simulation time step,

$\Delta t$

is the simulation time step,

![]() $q$

is the grid spacing at some generic point in a given direction and

$q$

is the grid spacing at some generic point in a given direction and

![]() $V$

is the velocity component at that point in the same direction) and Fourier (

$V$

is the velocity component at that point in the same direction) and Fourier (

![]() $F\!o = \nu \Delta t / q^2$

) numbers are also reported. The dot to the left of each row indicates the colour used in the following figures to indicate a given value of

$F\!o = \nu \Delta t / q^2$

) numbers are also reported. The dot to the left of each row indicates the colour used in the following figures to indicate a given value of

![]() $\Lambda _s/h$

.

$\Lambda _s/h$

.

Numerical details for the complete dataset used for this study are reported in table 1. The grid spacing is normalised with the worst-case value

![]() $\delta _{v,m}$

of the viscous length scale; such a value is usually observed at the initial conditions. Additionally to the decaying simulations, two reference simulations between smooth walls (

$\delta _{v,m}$

of the viscous length scale; such a value is usually observed at the initial conditions. Additionally to the decaying simulations, two reference simulations between smooth walls (

![]() $Re_\tau =180$

,

$Re_\tau =180$

,

![]() $Re_\tau =500$

) have been produced using the same grid used for rough simulations. In this case,

$Re_\tau =500$

) have been produced using the same grid used for rough simulations. In this case,

![]() $N_{0}$

indicates the number of samples used for the calculation of steady-state statistics. Notice that we adjust the number of fields (

$N_{0}$

indicates the number of samples used for the calculation of steady-state statistics. Notice that we adjust the number of fields (

![]() $N_s$

,

$N_s$

,

![]() $N_0$

) used for the computation of statistics as we change

$N_0$

) used for the computation of statistics as we change

![]() $Re_\tau$

and

$Re_\tau$

and

![]() $\Lambda _s$

; as for the quantification of the degree of statistical convergence, see § 3.5. Generally,

$\Lambda _s$

; as for the quantification of the degree of statistical convergence, see § 3.5. Generally,

![]() $Re_\tau$

has a favourable effect on the convergence of statistics: as near-wall turbulent structures become smaller with larger

$Re_\tau$

has a favourable effect on the convergence of statistics: as near-wall turbulent structures become smaller with larger

![]() $Re_\tau$

, a larger number of these features are contained in a single flow snapshot. This yields a quicker falloff of the small-scale noise. It is thus expected that a lower number of snapshots (

$Re_\tau$

, a larger number of these features are contained in a single flow snapshot. This yields a quicker falloff of the small-scale noise. It is thus expected that a lower number of snapshots (

![]() $N_s$

,

$N_s$

,

![]() $N_0$

) is required for statistics to converge at high-

$N_0$

) is required for statistics to converge at high-

![]() $Re_\tau$

. The effect of the period

$Re_\tau$

. The effect of the period

![]() $\Lambda _s$

depends instead on the size

$\Lambda _s$

depends instead on the size

![]() $L_z$

of the simulation box. As previously explained, data from the several spanwise periods contained in a single snapshot are averaged together (phase-averaging); the larger the number of periods

$L_z$

of the simulation box. As previously explained, data from the several spanwise periods contained in a single snapshot are averaged together (phase-averaging); the larger the number of periods

![]() $L_z/\Lambda _s$

in a single snapshot, the lower we expect the required

$L_z/\Lambda _s$

in a single snapshot, the lower we expect the required

![]() $N_s$

(or

$N_s$

(or

![]() $N_0$

) to be.

$N_0$

) to be.

3. Theoretical framework

3.1. Triple decomposition; momentum pathways and circulatory motions

Unlike homogeneous flows, which are best described using a Reynolds decomposition, flows featuring secondary motions are commonly described in terms of a triple decomposition. As would be done in a Reynolds decomposition, velocity fluctuations

![]() $\boldsymbol {u}^{\prime }$

are separated from the expected value

$\boldsymbol {u}^{\prime }$

are separated from the expected value

![]() $ \langle {\boldsymbol {u}} \rangle$

. Additionally, the expected value

$ \langle {\boldsymbol {u}} \rangle$

. Additionally, the expected value

![]() $ \langle {\boldsymbol {u}} \rangle$

is further split into its spanwise average

$ \langle {\boldsymbol {u}} \rangle$

is further split into its spanwise average

![]() $\boldsymbol {U} = \langle {\boldsymbol {u}} \rangle _z$

and a dispersive field

$\boldsymbol {U} = \langle {\boldsymbol {u}} \rangle _z$

and a dispersive field

![]() $\boldsymbol {u}_d = (\tilde {u},\tilde {v},\tilde {w})$

to yield the triple decomposition. This is done as the expected value

$\boldsymbol {u}_d = (\tilde {u},\tilde {v},\tilde {w})$

to yield the triple decomposition. This is done as the expected value

![]() $ \langle {\boldsymbol {u}} \rangle$

of the velocity depends on the conditioned spanwise variable

$ \langle {\boldsymbol {u}} \rangle$

of the velocity depends on the conditioned spanwise variable

![]() $\zeta$

(see § 2); using the triple decomposition, the spanwise-uniform field

$\zeta$

(see § 2); using the triple decomposition, the spanwise-uniform field

![]() $\boldsymbol {U}$

is separated from the spanwise-heterogeneous dispersive field

$\boldsymbol {U}$

is separated from the spanwise-heterogeneous dispersive field

![]() $\boldsymbol {u}_d$

,

$\boldsymbol {u}_d$

,

Since only the streamwise component has a non-zero spanwise average for the present geometry,

where

![]() $\hat {x}$

is a unit vector pointing in the streamwise direction and

$\hat {x}$

is a unit vector pointing in the streamwise direction and

![]() $U$

will be referred to as the mean velocity profile. The full velocity field then reads

$U$

will be referred to as the mean velocity profile. The full velocity field then reads

Note that the averaged fields

![]() $U$

,

$U$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol {u}_d$

are streamwise-invariant owing to the channel geometry. This allows to further split the dispersive field

$\boldsymbol {u}_d$

are streamwise-invariant owing to the channel geometry. This allows to further split the dispersive field

![]() $\boldsymbol {u}_d$

into two separate parts. Indeed, the continuity equation for

$\boldsymbol {u}_d$

into two separate parts. Indeed, the continuity equation for

![]() $\boldsymbol {u}_d$

reads

$\boldsymbol {u}_d$

reads

The above equation indicates that the two-dimensional vector field given by

![]() $\tilde {v}$

and

$\tilde {v}$

and

![]() $\tilde {w}$

is divergence-less. The distribution of

$\tilde {w}$

is divergence-less. The distribution of

![]() $\tilde {v}$

can be thus determined if

$\tilde {v}$

can be thus determined if

![]() $\tilde {w}$

is known (or vice versa), and the two form a single circulatory pattern. Such a cross-sectional circulatory motion is typical of secondary motions (see e.g. Neuhauser et al. Reference Neuhauser, Schäfer, Gatti and Frohnapfel2022) and will be treated separately from the remaining velocity component

$\tilde {w}$

is known (or vice versa), and the two form a single circulatory pattern. Such a cross-sectional circulatory motion is typical of secondary motions (see e.g. Neuhauser et al. Reference Neuhauser, Schäfer, Gatti and Frohnapfel2022) and will be treated separately from the remaining velocity component

![]() $\tilde {u}$

, which contains the information regarding the momentum pathways (e.g. Womack et al. Reference Womack, Volino, Meneveau and Schultz2022).

$\tilde {u}$

, which contains the information regarding the momentum pathways (e.g. Womack et al. Reference Womack, Volino, Meneveau and Schultz2022).

3.2. Velocity spectra of the dispersive field

In § 4, the dispersive field of the simulated flows will be inspected in real space to reveal the presence of secondary motions and their features. An additional analysis will be performed in spectral space by scrutinising the velocity spectra

![]() $\Phi _{\tilde {u}\tilde {u}}$

,

$\Phi _{\tilde {u}\tilde {u}}$

,

![]() $\Phi _{\tilde {v}\tilde {v}}$

,

$\Phi _{\tilde {v}\tilde {v}}$

,

![]() $\Phi _{\tilde {w}\tilde {w}}$

of the dispersive field. Velocity spectra are typically defined as the Fourier transform of the velocity correlation function (see, e.g., Davidson Reference Davidson2015). Such a definition cannot be used in the present case owing to the periodicity of the dispersive field: a Fourier series is used instead. As an example, the spectrum

$\Phi _{\tilde {w}\tilde {w}}$

of the dispersive field. Velocity spectra are typically defined as the Fourier transform of the velocity correlation function (see, e.g., Davidson Reference Davidson2015). Such a definition cannot be used in the present case owing to the periodicity of the dispersive field: a Fourier series is used instead. As an example, the spectrum

![]() $\Phi _{\tilde {u}\tilde {u}}$

of

$\Phi _{\tilde {u}\tilde {u}}$

of

![]() $\tilde {u}$

is defined as

$\tilde {u}$

is defined as

where

![]() $(\cdot )^\dagger$

indicates the conjugate of a complex number,

$(\cdot )^\dagger$

indicates the conjugate of a complex number,

![]() $\Delta \kappa _z$

is the Fourier resolution in the spanwise direction and

$\Delta \kappa _z$

is the Fourier resolution in the spanwise direction and

![]() $\mathcal {F}_z\{\tilde {u}\}$

indicates the coefficients of the Fourier series of

$\mathcal {F}_z\{\tilde {u}\}$

indicates the coefficients of the Fourier series of

![]() $\tilde {u}$

. These are defined as

$\tilde {u}$

. These are defined as

where

![]() $i$

is the imaginary unit and

$i$

is the imaginary unit and

![]() $\kappa _z$

the spanwise wavenumber. Owing to Parseval’s theorem, the spectrum of

$\kappa _z$

the spanwise wavenumber. Owing to Parseval’s theorem, the spectrum of

![]() $\tilde {u}$

can be related to the spanwise average of its energy:

$\tilde {u}$

can be related to the spanwise average of its energy:

\begin{equation} \sum _{\kappa _z=-\infty }^{+\infty } \Delta \kappa _z \Phi _{\tilde {u}\tilde {u}}(t,y,\kappa _z) = \frac {1}{\Lambda _s} \int _{0}^{\Lambda _s} \tilde {u}^2(t,y,\zeta )\,\text {d}\zeta = \big \langle {\tilde {u}^2} \big \rangle _z \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \sum _{\kappa _z=-\infty }^{+\infty } \Delta \kappa _z \Phi _{\tilde {u}\tilde {u}}(t,y,\kappa _z) = \frac {1}{\Lambda _s} \int _{0}^{\Lambda _s} \tilde {u}^2(t,y,\zeta )\,\text {d}\zeta = \big \langle {\tilde {u}^2} \big \rangle _z \end{equation}

The above equation justifies the common interpretation of the spectrum as the contribution of motions of wavelength

![]() $\lambda _z = 2\pi /\kappa _z$

to the energy of the flow.

$\lambda _z = 2\pi /\kappa _z$

to the energy of the flow.

3.3. Triple-decomposed momentum and velocity budgets

Additionally to the spectra, the energy budget of the streamwise dispersive velocity component

![]() $\tilde {u}$

will be analysed at a steady state in § 4. For completeness, and to shed light on the way energy is redistributed between the mean, dispersive and fluctuation fields, each of the corresponding budget equations will be presented in the following discussion (including equations that will not be further discussed in the paper). These budget equations can be easily obtained starting from the Reynolds-averaged momentum budget and from the budget equation of the Reynolds stress tensor (see, e.g., Davidson Reference Davidson2015):

$\tilde {u}$

will be analysed at a steady state in § 4. For completeness, and to shed light on the way energy is redistributed between the mean, dispersive and fluctuation fields, each of the corresponding budget equations will be presented in the following discussion (including equations that will not be further discussed in the paper). These budget equations can be easily obtained starting from the Reynolds-averaged momentum budget and from the budget equation of the Reynolds stress tensor (see, e.g., Davidson Reference Davidson2015):

\begin{align} \frac {\partial \big \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_j} \big \rangle }{\partial t} + \left \langle {u_k} \right \rangle \frac {\partial }{\partial x_k} \big \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_j} \big \rangle \,=\, & - \,\left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle \frac {\partial \langle {u_j} \rangle }{\partial x_k} - \big \langle {u^{\prime}_ju^{\prime}_k} \big \rangle \frac {\partial \left \langle {u_i} \right \rangle }{\partial x_k} \nonumber\\ & - \,\frac {\partial }{\partial x_k} \left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_j u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle - \frac {\partial }{\partial x_i} \left \langle {u^{\prime}_j\frac {P^{\prime}}{\rho }} \right \rangle - \frac {\partial }{\partial x_j} \left \langle {u^{\prime}_i \frac {P^{\prime}}{\rho }} \right \rangle \nonumber\\ & + \,\left \langle {\frac {P^{\prime}}{\rho }\left (\frac {\partial u^{\prime}_i }{\partial x_j} + \frac {\partial u^{\prime}_j}{\partial x_i}\right )} \right \rangle \nonumber \\ & + \,\nu \nabla ^2 \big \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_j} \big \rangle - 2\nu \left \langle {\frac {\partial u^{\prime}_i }{\partial x_k}\frac {\partial u^{\prime}_j}{\partial x_k}} \right \rangle .\end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\partial \big \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_j} \big \rangle }{\partial t} + \left \langle {u_k} \right \rangle \frac {\partial }{\partial x_k} \big \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_j} \big \rangle \,=\, & - \,\left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle \frac {\partial \langle {u_j} \rangle }{\partial x_k} - \big \langle {u^{\prime}_ju^{\prime}_k} \big \rangle \frac {\partial \left \langle {u_i} \right \rangle }{\partial x_k} \nonumber\\ & - \,\frac {\partial }{\partial x_k} \left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_j u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle - \frac {\partial }{\partial x_i} \left \langle {u^{\prime}_j\frac {P^{\prime}}{\rho }} \right \rangle - \frac {\partial }{\partial x_j} \left \langle {u^{\prime}_i \frac {P^{\prime}}{\rho }} \right \rangle \nonumber\\ & + \,\left \langle {\frac {P^{\prime}}{\rho }\left (\frac {\partial u^{\prime}_i }{\partial x_j} + \frac {\partial u^{\prime}_j}{\partial x_i}\right )} \right \rangle \nonumber \\ & + \,\nu \nabla ^2 \big \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_j} \big \rangle - 2\nu \left \langle {\frac {\partial u^{\prime}_i }{\partial x_k}\frac {\partial u^{\prime}_j}{\partial x_k}} \right \rangle .\end{align}

The above equations are usually derived by time-averaging, whereas the present work resorts to averaging in the streamwise direction, over multiple repetitions of a simulation and over multiple phases of a periodic domain. Nevertheless, it is trivially shown that the above equations are valid regardless of how averaging is performed as long as the averaging operator fulfils the following properties (as it does in this case):

where

![]() $f$

indicates a generic random function. Equation (3.9) is only valid for the expected velocity field

$f$

indicates a generic random function. Equation (3.9) is only valid for the expected velocity field

![]() $ \langle {\boldsymbol {u}} \rangle$

; leveraging the fact that the triple decomposition is a particular case of the Reynolds one, a budget equation for the

$ \langle {\boldsymbol {u}} \rangle$

; leveraging the fact that the triple decomposition is a particular case of the Reynolds one, a budget equation for the

![]() $i$

th component

$i$

th component

![]() $U_i$

of the mean field can be obtained by substituting (3.1) in (3.9) and taking a spanwise average:

$U_i$

of the mean field can be obtained by substituting (3.1) in (3.9) and taking a spanwise average:

The above equation resembles the Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes momentum equation (3.9), except that an additional term appears. Not only does the mean field feel the presence of turbulence through the Reynolds stress

![]() $ \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \rangle _z$

, but it is also influenced by the dispersive field through the dispersive stress

$ \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \rangle _z$

, but it is also influenced by the dispersive field through the dispersive stress

![]() $ \langle {\tilde {u}_i\tilde {u}_k} \rangle _z$

. Notice, moreover, that (2.4), which describes the time-evolution of the bulk velocity, can be obtained by integrating (3.12) over the flow domain. By once again substituting (3.1) in (3.9) and by subtracting (3.12), one obtains a balance equation for the dispersive momentum:

$ \langle {\tilde {u}_i\tilde {u}_k} \rangle _z$

. Notice, moreover, that (2.4), which describes the time-evolution of the bulk velocity, can be obtained by integrating (3.12) over the flow domain. By once again substituting (3.1) in (3.9) and by subtracting (3.12), one obtains a balance equation for the dispersive momentum:

\begin{align} \frac {\partial \tilde {u}_i}{\partial t} + \left (U_k + \tilde {u}_k\right )\frac {\partial \tilde {u}_i}{\partial x_k} + \frac {1}{\rho }\frac {\partial \tilde {p}}{\partial x_i} = \nu \nabla ^2\tilde {u}_i &\underbrace {- \tilde {u}_k\frac {\partial U_i}{\partial x_k}}_{\text {V4}} + \frac {\partial }{\partial x_k} \left \langle {\tilde {u}_i \tilde {u}_k} \right \rangle _z \\ &- \frac {\partial }{\partial x_k} \left ( \left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle - \left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle _z \right ) \notag, \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\partial \tilde {u}_i}{\partial t} + \left (U_k + \tilde {u}_k\right )\frac {\partial \tilde {u}_i}{\partial x_k} + \frac {1}{\rho }\frac {\partial \tilde {p}}{\partial x_i} = \nu \nabla ^2\tilde {u}_i &\underbrace {- \tilde {u}_k\frac {\partial U_i}{\partial x_k}}_{\text {V4}} + \frac {\partial }{\partial x_k} \left \langle {\tilde {u}_i \tilde {u}_k} \right \rangle _z \\ &- \frac {\partial }{\partial x_k} \left ( \left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle - \left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle _z \right ) \notag, \end{align}

where

![]() $\tilde {u}_i$

indicates the

$\tilde {u}_i$

indicates the

![]() $i$

th component of

$i$

th component of

![]() $\boldsymbol {u}_d$

. Notice that (3.12) and (3.13) are of general validity (symmetries and simplifications due to the geometry have not been considered yet). Starting from the momentum budgets (3.12) and (3.13), energy budgets are trivially obtained by multiplication with

$\boldsymbol {u}_d$

. Notice that (3.12) and (3.13) are of general validity (symmetries and simplifications due to the geometry have not been considered yet). Starting from the momentum budgets (3.12) and (3.13), energy budgets are trivially obtained by multiplication with

![]() $U_i$

and

$U_i$

and

![]() $\tilde {u}_i$

, respectively, and by performing a subsequent spanwise average. Additionally, an energy budget for the fluctuation field can be obtained by substituting (3.1) in (3.10) and by spanwise-averaging. After rearranging some terms, one obtains

$\tilde {u}_i$

, respectively, and by performing a subsequent spanwise average. Additionally, an energy budget for the fluctuation field can be obtained by substituting (3.1) in (3.10) and by spanwise-averaging. After rearranging some terms, one obtains

\begin{align} \frac {\partial }{\partial t}\frac {U_i^2}{2} \,+\, U_k \frac {\partial }{\partial x_k}\frac {U_i^2}{2} \,=\,\, &\nu \nabla ^2\frac {U_i^2}{2} \,-\, \nu \left (\frac {\partial U_i}{\partial x_k}\frac {\partial U_i}{\partial x_k}\right ) \,-\, \frac {U_i}{\rho }\frac {\partial \left \langle {P} \right \rangle _z}{\partial x_i} \\ \notag & + \underbrace {\left \langle {\tilde {u}_i\tilde {u}_k} \right \rangle _z\frac {\partial U_i}{\partial x_k}}_{\text {M5}} \,+\, \left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle _z\frac {\partial U_i}{\partial x_k} \\ \notag &- \frac {\partial }{\partial x_k}\left [ U_i \left ( \left \langle {\tilde {u}_i\tilde {u}_k} \right \rangle _z + \left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle _z \right ) \right ], \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\partial }{\partial t}\frac {U_i^2}{2} \,+\, U_k \frac {\partial }{\partial x_k}\frac {U_i^2}{2} \,=\,\, &\nu \nabla ^2\frac {U_i^2}{2} \,-\, \nu \left (\frac {\partial U_i}{\partial x_k}\frac {\partial U_i}{\partial x_k}\right ) \,-\, \frac {U_i}{\rho }\frac {\partial \left \langle {P} \right \rangle _z}{\partial x_i} \\ \notag & + \underbrace {\left \langle {\tilde {u}_i\tilde {u}_k} \right \rangle _z\frac {\partial U_i}{\partial x_k}}_{\text {M5}} \,+\, \left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle _z\frac {\partial U_i}{\partial x_k} \\ \notag &- \frac {\partial }{\partial x_k}\left [ U_i \left ( \left \langle {\tilde {u}_i\tilde {u}_k} \right \rangle _z + \left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle _z \right ) \right ], \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\partial }{\partial t}\frac {\left \langle {\tilde {u}_i^2} \right \rangle _z}{2} \,+\, \underbrace {\frac {\partial }{\partial x_k}\left \langle { (U_k + \tilde {u}_k) \frac {\tilde {u}_i^2}{2} } \right \rangle _z}_{\text {D1}} \,=\,\, &\underbrace {\phantom {\Big |\!}\nu \nabla ^2\frac {\left \langle {\tilde {u}_i^2} \right \rangle _z}{2}}_{\text {D2}} \,\underbrace {-\, \nu \left \langle {\frac {\partial \tilde {u}_i}{\partial x_k}\frac {\partial \tilde {u}_i}{\partial x_k}} \right \rangle _z}_{\text {D3}} \,\underbrace {-\, \left \langle {\frac {\tilde {u}_i}{\rho }\frac {\partial \tilde {P}}{\partial x_i}} \right \rangle _z}_{\text {D4}} \\ \notag & \underbrace {- \left \langle {\tilde {u}_i \tilde {u}_k} \right \rangle _z \frac {\partial U_i}{\partial x_k}}_{\text {D5}} \,+\, \underbrace {\left \langle {\left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle \frac {\partial \tilde {u}_i}{\partial x_k}} \right \rangle _z}_{\text {D6}}\\ \notag & \underbrace {- \frac {\partial }{\partial x_k} \left \langle {\tilde {u}_i\left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle } \right \rangle _z}_{\text {D7}}, \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\partial }{\partial t}\frac {\left \langle {\tilde {u}_i^2} \right \rangle _z}{2} \,+\, \underbrace {\frac {\partial }{\partial x_k}\left \langle { (U_k + \tilde {u}_k) \frac {\tilde {u}_i^2}{2} } \right \rangle _z}_{\text {D1}} \,=\,\, &\underbrace {\phantom {\Big |\!}\nu \nabla ^2\frac {\left \langle {\tilde {u}_i^2} \right \rangle _z}{2}}_{\text {D2}} \,\underbrace {-\, \nu \left \langle {\frac {\partial \tilde {u}_i}{\partial x_k}\frac {\partial \tilde {u}_i}{\partial x_k}} \right \rangle _z}_{\text {D3}} \,\underbrace {-\, \left \langle {\frac {\tilde {u}_i}{\rho }\frac {\partial \tilde {P}}{\partial x_i}} \right \rangle _z}_{\text {D4}} \\ \notag & \underbrace {- \left \langle {\tilde {u}_i \tilde {u}_k} \right \rangle _z \frac {\partial U_i}{\partial x_k}}_{\text {D5}} \,+\, \underbrace {\left \langle {\left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle \frac {\partial \tilde {u}_i}{\partial x_k}} \right \rangle _z}_{\text {D6}}\\ \notag & \underbrace {- \frac {\partial }{\partial x_k} \left \langle {\tilde {u}_i\left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle } \right \rangle _z}_{\text {D7}}, \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\partial }{\partial t} \frac {\left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_i } \right \rangle _z}{2} + \frac {\partial }{\partial x_k}\!\left \langle {\!\left (U_k + \tilde {u}_k\right )\! \frac {\left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_i } \right \rangle }{2}\!} \right \rangle _z\! =\,\, & + \,\nu \nabla ^2 \frac {\left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_i } \right \rangle _z}{2} \,-\, \nu \left \langle {\frac {\partial u^{\prime}_i }{\partial x_k}\frac {\partial u^{\prime}_i }{\partial x_k}} \right \rangle _z \notag\\ & - \left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle _z\frac {\partial U_i}{\partial x_k} \,\underbrace {-\, \left \langle {\left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle \frac {\partial \tilde {u}_i}{\partial x_k}} \right \rangle _z}_{\text {F6}} \notag\\ & -\frac {1}{2}\frac {\partial }{\partial x_k} \left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle _z \,-\, \frac {\partial }{\partial x_i} \left \langle {\frac {u^{\prime}_i }{\rho }P^{\prime}} \right \rangle _z. \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\partial }{\partial t} \frac {\left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_i } \right \rangle _z}{2} + \frac {\partial }{\partial x_k}\!\left \langle {\!\left (U_k + \tilde {u}_k\right )\! \frac {\left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_i } \right \rangle }{2}\!} \right \rangle _z\! =\,\, & + \,\nu \nabla ^2 \frac {\left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_i } \right \rangle _z}{2} \,-\, \nu \left \langle {\frac {\partial u^{\prime}_i }{\partial x_k}\frac {\partial u^{\prime}_i }{\partial x_k}} \right \rangle _z \notag\\ & - \left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle _z\frac {\partial U_i}{\partial x_k} \,\underbrace {-\, \left \langle {\left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle \frac {\partial \tilde {u}_i}{\partial x_k}} \right \rangle _z}_{\text {F6}} \notag\\ & -\frac {1}{2}\frac {\partial }{\partial x_k} \left \langle {u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_i u^{\prime}_k} \right \rangle _z \,-\, \frac {\partial }{\partial x_i} \left \langle {\frac {u^{\prime}_i }{\rho }P^{\prime}} \right \rangle _z. \end{align}

The above equations were also found by Reynolds & Hussain (Reference Reynolds and Hussain1972) using a slightly different averaging technique. Consider the equation for the dispersive kinetic energy (3.15). The dispersive kinetic energy gets transported by both the mean and the dispersive fields (term D1); a pressure term appears in the equation (D4), as well as the usual viscous diffusion (D2) and dissipation (D3) terms. The former indicates that viscosity tends to smear the dispersive energy out over time, whereas the latter represents the power lost to viscous forces. The two remaining equations ((3.14) and (3.16)) all share analogous transport, pressure and viscous terms; the only difference is that the mean kinetic energy

![]() $U_i^2$

is only transported by the mean field

$U_i^2$

is only transported by the mean field

![]() $U_i$

, and not by the dispersive one

$U_i$

, and not by the dispersive one

![]() $\tilde {u}_i$

.

$\tilde {u}_i$

.

Most importantly, the above equations shed a light on how the mean, dispersive and fluctuation fields exchange energy. For instance, the dispersive stress term D5 appears both in the balance of dispersive energy (3.15) and in the balance of mean energy (3.14) (term M5) with opposite sign: it thus represents an exchange of power between the mean and the dispersive fields. Similarly, term D6 represents an exchange of power between the dispersive and fluctuation fields, as it appears both in the dispersive balance and in the fluctuation one (3.16) (term F6) with opposite sign. To sum up, the dispersive stresses enable the exchange of energy between the mean and the dispersive fields, whereas the Reynolds stresses allow the exchange of energy between the dispersive and the fluctuation field (and additionally between the mean and the fluctuation field, as is usual; see (3.14) and (3.16)).

In § 4, only the energy budget of the streamwise dispersive energy

![]() $\tilde {u}^2$

will be analysed; indeed, the quantities involved in the budgets of the two remaining components

$\tilde {u}^2$

will be analysed; indeed, the quantities involved in the budgets of the two remaining components

![]() $\tilde {v}^2$

and

$\tilde {v}^2$

and

![]() $\tilde {w}^2$

are too small compared with the fluctuations to be captured with a satisfactory signal-to-noise ratio. Such a

$\tilde {w}^2$

are too small compared with the fluctuations to be captured with a satisfactory signal-to-noise ratio. Such a

![]() $\tilde {u}^2$

-budget can be obtained in a similar way to (3.15), but without averaging in the spanwise direction; after considering all the simplifications and symmetries due to the present geometry, the budget reads

$\tilde {u}^2$

-budget can be obtained in a similar way to (3.15), but without averaging in the spanwise direction; after considering all the simplifications and symmetries due to the present geometry, the budget reads

\begin{align} \frac {\partial }{\partial t} \frac {\tilde {u}^2}{2} + \underbrace {\left ( \tilde {v}\frac {\partial }{\partial y} + \tilde {w}\frac {\partial }{\partial \zeta } \right ) \frac {\tilde {u}^2}{2}}_{\mathcal {T}_a} \,=\, &\underbrace {\nu \nabla ^2\frac {\tilde {u}^2}{2} -\nu \left (\frac {\partial \tilde {u}}{\partial y}\frac {\partial \tilde {u}}{\partial y} + \frac {\partial \tilde {u}}{\partial \zeta }\frac {\partial \tilde {u}}{\partial \zeta } \right )}_{\mathcal {V}} + \underbrace {\tilde {u}\frac {\partial }{\partial y}\left \langle {\tilde {u}\tilde {v}} \right \rangle _z}_{\mathcal {T}_c} \nonumber\\ &\underbrace {-\,\tilde {u}\tilde {v}\frac {\partial U}{\partial y}}_{\mathcal {P}} \underbrace {-\, \tilde {u}\frac {\partial }{\partial y}\left (\left \langle {u^{\prime}v^{\prime}} \right \rangle - \left \langle {u^{\prime}v^{\prime}} \right \rangle _z \right )}_{\mathcal {T}_{uv}} \underbrace {- \tilde {u}\frac {\partial }{\partial \zeta }\left \langle {u^{\prime}w^{\prime}} \right \rangle }_{\mathcal {T}_{uw}}. \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\partial }{\partial t} \frac {\tilde {u}^2}{2} + \underbrace {\left ( \tilde {v}\frac {\partial }{\partial y} + \tilde {w}\frac {\partial }{\partial \zeta } \right ) \frac {\tilde {u}^2}{2}}_{\mathcal {T}_a} \,=\, &\underbrace {\nu \nabla ^2\frac {\tilde {u}^2}{2} -\nu \left (\frac {\partial \tilde {u}}{\partial y}\frac {\partial \tilde {u}}{\partial y} + \frac {\partial \tilde {u}}{\partial \zeta }\frac {\partial \tilde {u}}{\partial \zeta } \right )}_{\mathcal {V}} + \underbrace {\tilde {u}\frac {\partial }{\partial y}\left \langle {\tilde {u}\tilde {v}} \right \rangle _z}_{\mathcal {T}_c} \nonumber\\ &\underbrace {-\,\tilde {u}\tilde {v}\frac {\partial U}{\partial y}}_{\mathcal {P}} \underbrace {-\, \tilde {u}\frac {\partial }{\partial y}\left (\left \langle {u^{\prime}v^{\prime}} \right \rangle - \left \langle {u^{\prime}v^{\prime}} \right \rangle _z \right )}_{\mathcal {T}_{uv}} \underbrace {- \tilde {u}\frac {\partial }{\partial \zeta }\left \langle {u^{\prime}w^{\prime}} \right \rangle }_{\mathcal {T}_{uw}}. \end{align}

An additional term appears here with respect to (3.15) – that is,

![]() $\mathcal {T}_c$

. This term integrates to zero when spanwise-averaged, both explaining its absence from (3.15) and indicating that the term only spatially redistributes

$\mathcal {T}_c$

. This term integrates to zero when spanwise-averaged, both explaining its absence from (3.15) and indicating that the term only spatially redistributes

![]() $\tilde {u}$

-energy. The remaining terms all have a correspondent in (3.15). Notice that here, both the viscous diffusion (D2 in (3.15)) and the viscous dissipation (D3) are grouped in a single term

$\tilde {u}$

-energy. The remaining terms all have a correspondent in (3.15). Notice that here, both the viscous diffusion (D2 in (3.15)) and the viscous dissipation (D3) are grouped in a single term

![]() $\mathcal {V}$

. The terms

$\mathcal {V}$

. The terms

![]() $\mathcal {T}_{uv}$

and

$\mathcal {T}_{uv}$

and

![]() $\mathcal {T}_{uw}$

quantify the work done by the Reynolds stresses on the dispersive velocity

$\mathcal {T}_{uw}$

quantify the work done by the Reynolds stresses on the dispersive velocity

![]() $\tilde {u}$

. Such work was rewritten in (3.15) as two separate terms (D6 and D7), of which one (D6) corresponds to a power exchange with the fluctuation field, and the other (D7) can be easily shown to turn zero for the

$\tilde {u}$

. Such work was rewritten in (3.15) as two separate terms (D6 and D7), of which one (D6) corresponds to a power exchange with the fluctuation field, and the other (D7) can be easily shown to turn zero for the

![]() $\tilde {u}$

component when integrated over the flow domain (notice that the same does not hold for the

$\tilde {u}$

component when integrated over the flow domain (notice that the same does not hold for the

![]() $w$

component owing to the slip length boundary condition). That is, term D7 only yields a spatial redistribution of

$w$

component owing to the slip length boundary condition). That is, term D7 only yields a spatial redistribution of

![]() $\tilde {u}$

-energy.

$\tilde {u}$

-energy.

Finally, the

![]() $\mathcal {P}$

term of (3.17) is of particular interest for the results of this paper. We refer to such a term as dispersive production owing to its similarity to the canonical turbulence production term in a channel flow (Davidson Reference Davidson2015). Such a term corresponds to the D5 term in (3.15), and it thus represents an energy exchange with the mean field. The term accounts for the work done by the momentum flux V4 in (3.13) on the velocity

$\mathcal {P}$

term of (3.17) is of particular interest for the results of this paper. We refer to such a term as dispersive production owing to its similarity to the canonical turbulence production term in a channel flow (Davidson Reference Davidson2015). Such a term corresponds to the D5 term in (3.15), and it thus represents an energy exchange with the mean field. The term accounts for the work done by the momentum flux V4 in (3.13) on the velocity

![]() $\tilde {u}$

. The momentum flux is better discussed by considering the balance of streamwise momentum and by applying all simplifications due to the geometry:

$\tilde {u}$

. The momentum flux is better discussed by considering the balance of streamwise momentum and by applying all simplifications due to the geometry:

It is clear from (3.18) that the discussed momentum flux originates from

![]() $\tilde {v}$

transporting the mean field

$\tilde {v}$

transporting the mean field

![]() $U$

. In other words, the circulatory dispersive

$U$

. In other words, the circulatory dispersive

![]() $\tilde {v}$

-

$\tilde {v}$

-

![]() $\tilde {w}$

motions do not directly provide energy to the streamwise component

$\tilde {w}$

motions do not directly provide energy to the streamwise component

![]() $\tilde {u}$

, but still passively enable the transfer of energy from the mean flow to

$\tilde {u}$

, but still passively enable the transfer of energy from the mean flow to

![]() $\tilde {u}$

by transporting

$\tilde {u}$

by transporting

![]() $U$

-momentum. A more intuitive explanation of how the

$U$

-momentum. A more intuitive explanation of how the

![]() $\tilde {u}$

field is indirectly produced by the circulatory motions (under certain circumstances) will be provided in § 4 using flow visualisations as an example.

$\tilde {u}$

field is indirectly produced by the circulatory motions (under certain circumstances) will be provided in § 4 using flow visualisations as an example.

3.4. Time scale for the decay of secondary motions; volume and plane averages

In § 5, the time needed by secondary motions to decay will be measured as per the objective of this study. Before doing so, such a time scale needs to be defined. Defining a time scale for the decay of turbulent eddies is a largely subjective process. For instance, Flores & Jiménez (Reference Flores and Jiménez2010) found that the log-layer of turbulent flows in a restricted simulation box bursts quasiperiodically, and linked the estimated period to the life span of log-layer eddies. LeHew et al. (Reference LeHew, Guala and McKeon2013) and Lozano-Durán & Jiménez (Reference Lozano-Durán and Jiménez2014), instead, resorted to identifying turbulent coherent structures and tracking them in time; their lifespan is given by the distance in time between their first and last identification. In our case, no sophisticated strategy is needed to track the secondary motions, as their spatial position is fixed and their features are satisfactorily captured by the dispersive velocity field

![]() $\boldsymbol {u}_d$

(as will be discussed in § 4). We thus define some energy measure

$\boldsymbol {u}_d$

(as will be discussed in § 4). We thus define some energy measure

![]() $e(t)\geqslant 0$

using the dispersive velocity and track it in time; the energy will start from a value

$e(t)\geqslant 0$