The human gut microbiota

The human microbiome

The human microbiome has emerged as an area of utmost interest, and since the last two decades, numerous studies have highlighted its impact on the physiology leading to impact on health and diseases. The microbiota considered to outnumber by 10 the number of eukaryotic cells has been recently reevaluated at 3.8 1013, showing that the number of bacteria is actually of the same order of human cells with a ratio close to 1/1.Reference Sender, Fuchs and Milo 1 Nevertheless, it does not decreased the major importance of the microbiome. The most heavily inhabited organ with micro-organisms is the gastrointestinal tract, harboring a huge diversity with more than 500 bacterial species that represent about 25 times more genes than the human genome.Reference Qin, Li and Raes 2 , Reference Dietert and Dietert 3 Of particular interest is the gut microbiome, now regarded as an organ. Indeed, this microbiota displays various vital functions.Reference Jones, Ganopolsky, Martoni, Labbe and Prakash 4 Protection against colonization by pathogens is a well-known function mediated by several mechanisms involving direct mechanisms such as production of bacteriocins or bacterial metabolites, or competition for nutrients, or indirect mechanisms such as stimulation of the host innate immunity via the recognition of microbe-associated molecular patterns by cell receptors such as Toll-like receptors. The gut microbiota has also important metabolic functions through fermentation of indigestible carbohydrates responsible for energy harvest and storage, and trophic effect on the intestinal mucosa as well as systemic effects via short-chain fatty-acid (SCFA) production. Finally, gut microbiota is involved in a cross-talk with the immune cells providing major immune roles with modulation of the innate immunity and maturation and development of cell-mediates immunity.

Hence, the gut microbiota interacts extensively with the host, and there are accumulating data linking many human diseases – such as inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, diabetes, asthma and allergies – with dysbiosis, that is, alteration in its composition.Reference Fujimura, Slusher, Cabana and Lynch 5 , Reference Neish 6 However, it remains challenging to identify the precise changes in the microbiota that are responsible for mediating diseases development and when they occur. However, there is currently growing evidence of the importance of the early gut microbiota.

Early life programming

It is becoming an established concept stating that there is a critical window for later health early in life. This concept called the developmental origin of health and disease (DOHaD) is increasingly supported by the scientific community.Reference Charles, Delpierre and Breant 7 It highlights the importance of the period from the conception to the 2 years of life, the so-called ‘first thousand days’ recognized to be a crucial period in the infant development. These 1000 days, according to the motto of the World Health Organization, constitute a unique window of sensitivity in which the environment in all its forms (nutritional, ecological, socio-economical, lifestyles) creates marks on the genome, programming health and the future risk of illness of an individual for life. Hence, understanding how our gut microbial community is shaped and what their determinants are is of great interest.

The gut microbiota establishment in neonates

The bacterial establishment process

It is a complex phenomenon, which in terms of kinetics of acquisition of the microbiota is currently relatively well known. The formation of the gut microbiota starts rapidly from the rupture of membranes. At birth, neonates are suddenly immersed in a rich and varied bacterial environment, and they will be rapidly colonized by an initially simple microbiota mainly originating from mother’s microbiota, in particular from vagina and feces.Reference Gritz and Bhandari 8 , Reference Palmer, Bik, Digiulio, Relman and Brown 9 In case of breastfeeding, breast milk can also participate in the neonatal bacterial establishment.Reference Jost, Lacroix, Braegger, Rochat and Chassard 10 , Reference Fitzstevens, Smith and Hagadorn 11 Infants are then continually exposed to new bacteria from the environment, food and adult skin bacteria via feeding, physical contact or kisses. This leads to a high interindividual variability in both composition and patterns of bacterial colonization during the first weeks of life. During the infant stage of life, numerous bacteria are encountered in the environment and gut microbiota develops with increased diversity toward the adult pattern by age 3 years.Reference Yatsunenko, Rey and Manary 12

Perinatal determinants

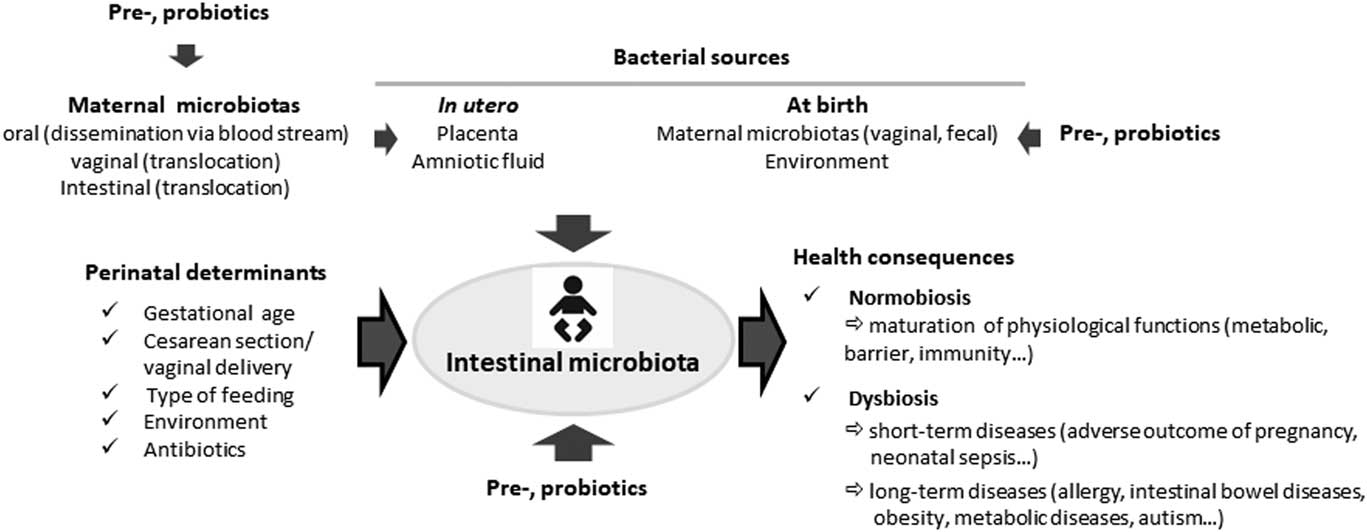

Various perinatal determinants can affect the pattern of bacterial colonization, that is, gestational age, mode of delivery, mode of infant feeding, maternal, intrapartum and neonatal antibiotic courses, as well as familial environment, geographical and cultural traditions (Figs 1 and 2).

Fig. 1 Influence of perinatal determinants on the neonatal gut microbiota.

Fig. 2 Bacterial establishment in neonates and health consequences.

The mode of birth affects the initial bacterial establishment since bacteria encountered by the infant vaginally delivered are very different from those experienced through cesarean deliveries. Indeed, infants born by cesarean section are mainly faced with bacteria from their environment: air and medical staff, and a delayed colonization by maternal bacteria is observed in numerous studies.Reference Biasucci, Rubini and Riboni 13 – Reference Martin, Makino and Cetinyurek Yavuz 16 Interestingly, although throughout the first year of life bacterial profiles become more similar whatever the mode of birth, differences in bacterial profiles can persist throughout the first year of life.Reference Rutayisire, Huang, Liu and Tao 15 , Reference Azad, Konya and Maughan 17 , Reference Backhed, Roswall and Peng 18 Differences linked to cesarean birth has been reported later in life in an American cohort of adults; however, whether it was acquired during birth is unknown.Reference Goedert, Hua, Yu and Shi 19 In a recent study, Chu et al. did not observed any effect of the mode of delivery on the neonatal and infant microbiota at 6 weeks.Reference Chu, Ma and Prince 20 However, at birth they analyzed the meconium which reflects rather the in utero environment than colonization at birth. Nevertheless, their findings on the meconium microbiota, which appears specific compared with other neonates’ body sites and not affected by the mode of birth, suggest a maternal origin that seeds the neonate earlier than previously thought.

Type of feeding has a great influence on the bacterial establishment. Breastfed infants have a microbiota profile with a specific high amount of Bifidobacterium, a genus known for its potential health benefits, whereas formula fed infants have a more diverse profile.Reference Azad, Konya and Maughan 17 , Reference Guaraldi and Salvatori 21 This influence is linked to the unique composition of human breast milk, rich in complex non-digestible oligosaccharides with more than 200 different molecules.Reference Jost, Lacroix, Braegger and Chassard 22 These aspects make breast milk a special feature in the world of living organisms with a very specific level and composition, in particular compared with cow milk, which is the basis of infant formulas. Due to their structure (β-glycosidic bonds), these oligosaccharides are not hydrolyzable by human digestive enzymes and therefore not assimilated in the small intestine. Hence, they will be substrates for micro-organisms in the large intestine, promoting the growth of specific bacteria. Nowadays, most infant formulas are supplemented with oligosaccharides, in particular fructo- and galacto-oligosaccharides with the aim to improve the intestinal microbiota in early life.Reference Oozeer, van and Ludwig 23 In addition, recent studies based on culture and molecular techniques have shown that breast milk could contain commensal bacteria with beneficial potentialities such as lactobacilli and bifidobacteria at levels ranging between 101 and 105 colony forming units/ml.Reference Fitzstevens, Smith and Hagadorn 11 Their origin remains unclear, either from the mother’s skin suggesting a contamination or from bacterial translocation from the maternal digestive tract to the mammary gland after internalization into leukocytes.Reference Jost, Lacroix, Braegger, Rochat and Chassard 10 Nevertheless, this microbiota could participate in the bacterial establishment in newborns as shown by studies that demonstrated similarities between breast milk bacteria and neonatal fecal microbiota.Reference Jost, Lacroix, Braegger and Chassard 22

The impact of antibiotics has first been examined in terms of selection of resistant micro-organisms. By contrast, the influence of antibiotic treatment on the bacterial establishment has been poorly investigated. Nevertheless, some studies showed the alteration of the bacterial profile in antibiotic-treated infants even for a short period. The main feature was a decrease in the biodiversity.Reference Tanaka, Kobayashi and Songjinda 24 , Reference Fouhy, Guinane and Hussey 25 An increase in potentially pathogenic and antibiotic-resistant bacteria associated to a decrease in potentially beneficial bacteria such as bifidobacteria and lactobacilli has also been reported.Reference Gibson, Crofts and Dantas 26 Intrapartum antibiotics may also impact the bacterial establishment.Reference Arboleya, Sanchez and Milani 27 , Reference Jaureguy, Carton and Panel 28 Interestingly, these early dysbiosis are still visible after a few weeks,Reference Tanaka, Kobayashi and Songjinda 24 , Reference Fouhy, Guinane and Hussey 25 , Reference Arboleya, Sanchez and Milani 27 suggesting the potential long-term consequences of dysbiosis linked to early antibiotic courses.

Gestational age is a major factor in the bacterial establishment, particularly in very and extremely preterm infants who can have an aberrant microbiota profile compared with fullterm infants.Reference La Rosa, Warner and Zhou 29 – Reference Groer, Luciano and Dishaw 31 Despite the great intervariability observed, the main feature of the bacterial establishment in the very preterm infants is a great imbalance in the bacterial profile. In fact, a delay in bacteria originating from the mother such as enterobacteria, or anaerobes belonging to the genera Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium is observed whereas bacteria from the environment such as staphylococci are at high levels with a high frequency. Colonization by Clostridium which is a spore-forming bacteria that can be in the environment may be dominant and related to the postnatal age.Reference La Rosa, Warner and Zhou 29 , Reference Ferraris, Butel and Campeotto 32 This bacterial establishment can be explained by the fact that these infants are more frequently born by cesarean section, very rapidly separated from their mother, placed into a highly sanitized intensive care environment, and frequently treated by broad-spectrum antibiotics. This particular bacterial pattern represent a risk factor for short-term diseases such as sepsis or necrotizing enterocolitis, the most dreaded disease in neonatal intensive care units.Reference Roze, Ancel and Lepage 33 , Reference Cassir, Benamar and Khalil 34

The environment can also condition the development of the microbiota, which may explain the delayed development of the maternal microbiota observed since a decade in industrialized countries, related to higher perinatal hygiene conditions in our countries compared with developing countries. The importance of the environment was also shown in studies that reported differences in gut microbiota depending on the geographical location.Reference Fallani, Young and Scott 35 – Reference Kemppainen, Ardissone and Davis-Richardson 37

Long-term health consequences of early dysbiosis in bacterial establishment

Exposure to all perinatal determinants described above may result in dysbiosis, that is, either a decrease in bacterial diversity or a delayed colonization by potential health beneficial bacteria, or both. This early dysbiosis can persist over several months and can have therefore long-lasting functional effects with an impact on disease risk later in lifeReference Gritz and Bhandari 8 , Reference Neu 38 (Fig. 1). Several epidemiologic studies have shown that factors known to alter the early bacterial gut pattern – such as cesarean section delivery, prematurity, and early exposure to antibiotics – have been found as risk factors for various diseases, as for example, allergic diseases or overweight/obesity as described later in the text. Dysbiosis has also been involved in the gut–brain axis, and a recent study reported an increased risk of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in preterm infants born at less than 27 weeks of gestational age and known to have a major dysbiosis.Reference Kuzniewicz, Wi and Qian 39

Early dysbiosis and allergic diseases

The prevalence of allergic diseases has increased globally over the last 50 years with discrepancies among their different clinical expressions, that is, atopic dermatitis, or intestinal and respiratory symptoms. It clearly appears nowadays that this increase is linked to sequential changes in lifestyle such as hygiene, indoor entertainment, changes in diet, and there is mounting evidence that the microbiota is a key environmental factor that plays a role. Indeed, allergic diseases are immunological pathologies, hallmarked by the differentiation of naive T cells into interleukin 4 secreting T cells (T helper type 2 cells or Th2). Neonates are biased toward Th2 cell responses with reference to adults.Reference Adkins, Leclerc and Marshall-Clarke 40 This immature Th2-dominant neonatal response undergoes environment-driven maturation via microbial contact during the early postnatal period, leading to the development of intestinal barrier functions and of regulatory T cell and a Th balance.Reference Quigley 41 , Reference Ohnmacht 42 Moreover, the immune system appears to be regulated by microbiota in a time restricted period during early life and to be influenced by the maternal microbiota.Reference Okada, Kuhn, Feillet and Bach 43 , Reference Gensollen, Iyer, Kasper and Blumberg 44 Alterations in the sequential establishment of gut microbiota observed in western countries could therefore be responsible for a Th balance deviation toward a Th2 profile, a major factor in the rise of allergic diseases. Indeed, epidemiological studies have linked factors influencing microbiota establishment and risk of allergy. Several studies showed that treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics in infancy, leading to dysbiosis, is associated with increased susceptibility to allergy such as asthma,Reference Foliaki, Pearce and Bjorksten 45 , Reference Pitter, Ludvigsson and Romor 46 eczemaReference Tsakok, McKeever, Yeo and Flohr 47 and allergic rhinitis.Reference Alm, Goksor and Pettersson 48 Cesarean section was also involved as a risk factor of food allergy/food atopy, allergic rhinitis, asthma, but meta-analyses highlighted conflicting results.Reference Huang, Chen and Zhao 49 , Reference Bager, Wohlfahrt and Westergaard 50 Cesarean section was positively associated with multiple sensitizations in the French cohort PARIS,Reference Gabet, Just, Couderc, Seta and Momas 51 whereas there was no evidence of such association neither in the first 5 years of life of the Asian cohort GUSTOReference Loo, Sim and Loy 52 nor in the Danish study.Reference Brix, Stokholm, Jonsdottir, Kristensen and Secher 53 The association could be influenced by the underlying indication for cesarean delivery. Indeed, emergency cesarean delivery, in contrast with elective one, often occurs after the onset of the labor and membranes rupture. It is then associated with both maternal and fetal stress and exposition to vaginal microbiota, favoring a colonization more similar to vaginal delivery. If Huang et al.Reference Huang, Chen and Zhao 49 found a 20% increase in the subsequent risk of asthma in children delivered by both elective or emergency cesarean section, Rusconi et al.Reference Rusconi, Zugna and Annesi-Maesano 54 who worked on individual data from nine European birth cohorts concluded that the increased risk of asthma is more associated to elective cesarean delivery, especially among children born at term. Prematurity and breastfeeding are both perinatal determinants that impact the bacterial establishment and they are studied for their role toward allergy risk. However, epidemiological studies yielded conflicting results, mainly due to differences in the study designs and study population, including definition of breastfed infants (partial, exclusive).

Besides, the role of the gut microbiota in the development of oral tolerance, as well as specific microbial signatures identification in allergy were confirmed using mice models.Reference Noval Rivas, Burton and Wise 55 In humans, several studies highlighted differences in the composition of bacterial communities in the feces of subject with or without allergic diseases; however, available epidemiological studies remain controversial. Numerous studies support that a dysbiosis in infancy is more importantReference Thompson-Chagoyan, Vieites, Maldonado, Edwards and Gil 56 than the prevalence of specific bacterial taxa.Reference Melli, do Carmo-Rodrigues, Araujo-Filho, Sole and de Morais 57

Prospective studies have shown changes in the fecal microbiota before the onset of any atopic symptoms. Colonization by Clostridium and especially Clostridium difficile has been several times, but not always, associated with development of atopic dermatitis, wheezing and sensitization before 2 years, while a high level of Escherichia coli has been associated only with the risk of developing eczema. Colonization by Clostridium cluster XIVa at 3 weeks of life could be an early indicator of the future development of asthmaReference Vael, Vanheirstraeten, Desager and Goossens 58 and food allergy.Reference Blazquez and Berin 59

Moreover, longitudinal studies highlighted different microbiota alterations associated with allergy only during the first weeks of life, defining then a critical window in early life. A decrease in diversity at 1 week and 1 month but not at 12 months was associated with asthma at 7 years of age.Reference Abrahamsson, Jakobsson and Andersson 60 Recently, Arrieta et al.Reference Arrieta, Stiemsma and Dimitriu 61 showed at 3 months of age, but not at 1 year, a transient decrease in the relative abundance of the bacterial genera Lachnospira, Veillonella, Faecalibacterium and Rothia during the first 100 days of life. Other bacterial groups were associated with an increased risk of asthma at 4 years of life, showing the complexity to point up the link between microbiota and pathologies.Reference Stiemsma, Arrieta and Dimitriu 62

Early dysbiosis and obesity

As for allergy, the prevalence of obesity increased tremendously over the last decades. If genetic transmission of risk of overweight and obesity is well established, others factors such as the early dysbiosis has received several lines of evidence. A first epidemiologic study on a cohort of 1255 infants showed that infants delivered by cesarean section had two-fold higher odds of childhood obesity, even after adjusting for maternal body mass index, birth weight and other confounding variables.Reference Huh, Rifas-Shiman and Zera 63 Likewise, exposure of infants to antibiotics was found to increase risk of childhood overweight in normal weight mother but not in overweight or obese mother.Reference Ajslev, Andersen, Gamborg, Sorensen and Jess 64 Moreover, the risk of childhood overweight is increase in child born from women with a high gestational body mass index, women who have a gut microbiota enriched in Bacteroides, Clostridium and Staphylococcus.Reference Ajslev, Andersen, Gamborg, Sorensen and Jess 64 , Reference Collado, Laitinen, Salminen and Isolauri 65 This is in accordance with a transmission of obesogenic microbiota through vaginal delivery but was not confirmed in other studies.Reference Azad, Bridgman, Becker and Kozyrskyj 66 However, experimental mice model confirmed that low dose of penicillin amplifies diet-induced obesity and that perturbation during a critical window in early life leads to long-term increased adiposity.Reference Cox, Yamanishi and Sohn 67 Among perinatal factors that influence gut microbiota establishment, cesarean delivery, despite some controversial study, was also associated with an increased risk of obesity.Reference Wen and Duffy 68 Breastfeeding is also reported to affect the risk of obesity. This influence can be due to the differences of the gut microbiota between breastfed and formula fed infants. Furthermore, human breast milk microbiota was reported to be different in its composition between mothers who underwent either cesarean section or vaginal delivery. Moreover, breast milk of obese mothers is characterized by a reduced microbiota diversity, and a distinct microbiota composition as compared with that from lean mothers.Reference Wen and Duffy 68

Early dysbiosis and brain disorders

The concept of the gut–brain axis, that is, a bidirectional channel of communication between the central nervous system and the enteric nervous system has long been appreciated. This complex communication ensures maintenance and coordination of gastrointestinal functions as well as a feedback from the gut to the brain.Reference Foster, Rinaman and Cryan 69 Since a decade, gut microbiota has emerged to be a new participant of these connexions leading to the concept of the microbiota–gut–brain axis. Numerous transmission routes can explain this complex network of communication, and recent findings point to the vague nerve, neuroendocrine systems and growth factors.Reference Rieder, Wisniewski, Alderman and Campbell 70 Today, accumulating evidence supports the influence of the gut microbiota on stress-related behaviors including anxiety and depression, as well as neuropsychiatric disorders.Reference Petra, Panagiotidou and Hatziagelaki 71 ASD is a severe neurodevelopmental disorder that impairs the child ability of social communications, and which exact mechanism is not clearly elucidated. ASD is often associated to gastrointestinal problems, and increasing evidence revealed a gut dysbiosis in ASD suffering children.Reference Vuong and Hsiao 72 , Reference Yang, Tian and Yang 73 Up to now, there is little consensus on specific bacteria involved. Several studies have reported a higher abundance of bacteria belonging to the genus Clostridium. Besides, a decrease in Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio and an increase in Lactobacillus and Desulfovibrio has been correlated with the severity of the pathology. Alterations in the gut functions have also been described, with, for instance, changes in bacterial metabolites that may contribute to the ASD pathogenesis. The potential harmful role of the gut microbiota has also been suggested by improvement in ASD clinical symptoms by antibiotic courses. Immune dysregulation frequently observed in ASD patients could be linked to an abnormal early bacterial pattern. Moreover, animal models demonstrated that the gut microbiota participate in the development of brain circuits involved in the control of stress, motor activity and anxiety behavior and cognitive functions.Reference Diaz Heijtz 74 It therefore raises the possibility that early dysbiosis may impact the neurodevelopment and the brain functions. Interestingly, prematurity was associated with an increased ASD risk, with a higher frequency in infants born at a lower gestational age, known to be colonized by a more aberrant microbiota.Reference Kuzniewicz, Wi and Qian 39 Elucidate the mechanisms mediating the interactions between the gut microbiota and the developing brain deserve further studies.

Could microbial programming of health and disease begin before birth?

For several decades the human fetus and placenta were considered sterile but discovery of a colonization in the meconium suggested a colonization in utero.Reference Jimenez, Marin and Martin 75 Today, there is mounting evidence of this microbial colonization despite fetal intact membranes and out of any infectious context. Indeed, placenta has been reported to harbor a specific microbiota through mainly molecular biology approaches.Reference Aagaard, Ma and Antony 76 – Reference Stout, Conlon and Landeau 78 Moreover, culture allowed identifying viable bacteria in the placenta.Reference Collado, Rautava, Aakko, Isolauri and Salminen 77 This microbiota appears to be quantitatively low but with some diversity and exhibits spatially variable profiles according to the different compartments of placenta (basal plate, placental villous and fetal membrane). Despite few concordant results, the entire literature on the placental microbiota does not allow a clear knowledge of neither its composition nor its origin. Some studies found a placental microbiome closely related to the oral microbiome rather than to the vaginal one,Reference Aagaard, Ma and Antony 76 whereas others found a potential connection with the bacterial species found in the vagina.Reference Han, Shen, Chung, Buhimschi and Buhimschi 79 , Reference Doyle, Harris and Kamiza 80 Even if the origin of the placental microbiota is still unknown it is recognized that it comes from the maternal microbiotas, from either oral cavity by dissemination, or vaginal microbiota or intestinal microbiota by translocation. Mounting importance is given to these first colonizing bacteria that are supposed to impact the future subsequent health of the mother and her infant. First, these bacteria and/or their DNA and/or other bacterial structures could trigger immune responses in the fetus and would therefore program the infant’s immune development during fetal life, earlier than previously considered. Second, several recent studies demonstrated a link between the composition of placental microbiota and some pathological conditions of the pregnancy.Reference Aagaard, Ma and Antony 76 , Reference Stout, Conlon and Landeau 78 , Reference Doyle, Harris and Kamiza 80 – Reference Zheng, Xiao and Zhang 86 In particular, it was shown in different studies a placental dysbiosis in preterm birth. However, discrepancies between studies suggested that biological and clinical implications of this microbiome are likely dependent on the microbiota profile that could or not favor a fetal–placental inflammation and early preterm birth.Reference Stout, Conlon and Landeau 78 Nowadays, there are more questions than answers about the origin of this microbiota and its eventual transfer to the infant before or during the delivery. However, it is difficult to conclude on the exact composition of this placental microbiota because all these recent studies reported different results about the bacterial species found in placenta. The variability in these results could be the consequence of a lack of precautions to prevent contamination of samples and/or a lack of appropriate controls. Besides, because of the paucity of the placental microbiota, it has been rightly pointed out by some scientists that the bacteria found in the placenta could be contaminants.Reference Perez-Munoz, Arrieta, Ramer-Tait and Walter 87 Thus, to date, data from the literature strongly suggest the existence of a placental microbiota that remains to be rigorously explored and characterized.

Several studies except oneReference Digiulio, Callahan and McMurdie 88 show significant alterations in the gut microbiota during pregnancy, with a reduced individual richness and an increased between-subject diversity.Reference Nuriel-Ohayon, Neuman and Koren 89 , Reference Koren, Goodrich and Cullender 90 Alterations in abundance of several species have been observed, as for example, an increased abundance of members of Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria and a reduced abundance of Faecalibacterium and other SCFA producers.Reference Koren, Goodrich and Cullender 90 Mechanisms of these modifications remain to be clarified, but changes in the host immunology as well as hormonal pattern may be important. These changes, that is, dysbiosis, inflammation and weight gain, are features of metabolic syndrome, which may be highly beneficial for pregnant women as they promote energy storage and provide the growth of the fetus. Besides, consequences of the maternal composition during pregnancy on the neonate in terms of health remain to be determined. Indeed, the maternal microbiota was shown to impact the immune gene expression and the number of innate cells in the neonate.Reference Gomez de Aguero, Ganal-Vonarburg and Fuhrer 91 Furthermore, maternal probiotic supplementation was shown to be able to modify the infant microbiota and to alter Toll-like receptor genes expression in the placenta and it was suggested that microbial exposure during pregnancy may be important for preventing allergic disease in the offspring.Reference Abrahamsson, Wu and Jenmalm 92 By contrast, aberrancies observed in the gut microbiota of pregnant women associated with both overweight and weight gain can be one factor contributing to obesity.Reference Collado, Isolauri, Laitinen and Salminen 93

Prebiotic and probiotics supplementation

The mounting evidence of relationships between the neonatal bacterial establishment and future health outcomes leads to the interest of a possible early modulation of the gut microbiota by the use of pre- and/or probiotics. Prebiotics are defined as substrate that is selectively utilized by host micro-organisms conferring a health benefit.Reference Gibson, Hutkins and Sanders 94 Probiotics are live micro-organisms that when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host.Reference Hill, Guarner and Reid 95 However, although their use has been increasing since the last two decades, it remains under debate, and it warrants further research before large recommendations of their use despite a clear appealing interest and encouraging results in some fields. This currently limits the recommendations made by expert committees. First, determining what constitutes the normal baseline microbiota colonization and defining dysbiosis and its potential deleterious health consequences remains questionable and warrant further research. Second, many questions remain to be answered in terms of which supplementation for which patients, which bacterial strains, effective dose, duration. Moreover, proven long-term health benefits of these supplementation are often lacking. For the period from conception to early development, that is, the first 1000 days, little research has been done and the mechanisms by which strains actually confer health still remain elemental. The optimal time to administer probiotics, the strain, dose and duration as well, to improve later health of the neonate, such as cognitive function, reduce atopy or infections and inflammatory events, or to favor a good outcome of pregnancy, by for instance reducing the risk of premature birth, requires more study (for review see Reid et al.Reference Reid, Kumar and Khan 96 ). However, some recommendations have recently been published. Based on meta-analyses, early supplementation by probiotics of preterm infants has been recognized to decrease both incidence and severity of necrotizing enterocolitis.Reference Alfaleh and Anabrees 97 Encouraging but discordant results has been reported for the supplementation with the aim to prevent from pediatric allergic diseases. This led to the World Allergy Organization (WAO) to write down specific recommendations concerning this supplementation limiting it to the population at a higher risk of developing allergy.Reference Fiocchi, Pawankar and Cuello-Garcia 98 Concerning prebiotic, the WAO suggests to use prebiotic supplementation in infants who are not exclusively breastfed and not using prebiotic supplementation in exclusively breastfed infants.Reference Cuello-Garcia, Fiocchi and Pawankar 99 Both of these recommendations are conditional and based on very low certainty of evidence. In addition, WAO has chosen not to provide a recommendation on prebiotic supplementation during pregnancy or while breastfeeding. Indeed, to date, there are no experimental or observational studies of prebiotic supplementation in pregnant women or breastfeeding mothers.

Hence, there is a potential for pre- and/or probiotics to prevent or repair any early dysbiosis. Their use appears to be a safe and feasible method to alter maternal and neonatal microbiota aiming at improving pregnancy and neonatal outcomes.Reference Sohn and Underwood 100 It warrants researches to edict recommendations based on scientific proofs of their beneficial effects on health.

Concluding remarks

The context of the DOHaD highlights the importance of the first 1000 days which are a critical window with implications for long-term health. Among several factors, the first gut colonizers and the subsequent gut microbiota establishment appears to be major determinants for gut maturation, metabolic and immunologic programming and consequently for short- and long-term health status. Hence, mounting importance is given to improve this critical period by promoting a ‘healthy’ gut ecosystem using pre- or probiotics supplementation, but also by taking into account the perinatal determinants impacting the bacterial establishment, for instance, by limiting the use of maternal and neonatal antibiotics or cesarean section.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

Part of this update has been presented in an invited lecture at the 3rd Congress of the French-speaking Society of the Developmental Origins of Health and Diseases (SF-DOHaD), Paris, 1-2 December 2016.