Introduction

Skeletal muscle plays a central role in metabolic health. It accounts for about 40% of body mass, 20% of energy expenditure and is an important contributor to postprandial glucose disposal.Reference Gardner and Rhodes 1 – Reference DeFronzo and Tripathy 4 Therefore, any defects in the development and growth of this tissue can potentially lead to permanent metabolic disruptions lasting into adult life. It is well documented that skeletal muscle fibre number, a determinant of muscle mass, is irreversibly reduced in offspring exposed to undernutrition in utero.Reference Maltin, Delday, Sinclair, Steven and Sneddon 5 , Reference Rehfeldt, Fiedler, Dietl and Ender 6 These offspring are also prone to developing insulin resistance and obesity in adult life.Reference Phipps, Barker and Hales 7 The effects of maternal obesity and/or excessive gestational weight gain on skeletal muscle development, growth and function into adult life are much less well characterised but appear to be just as detrimental. This review brings evidence in support of targeting maternal nutrition to optimise skeletal muscle development and growth in order to maximise offspring metabolic health into adult life. Evidence that exercise in early life may prove beneficial is also presented.

Obesity prevalence and cost

Current figures from the World Health Organization indicate that obesity rates have nearly doubled since 1980. 8 In 2008, 35% of adults were classed as overweight or obese worldwide. 9 Children are also affected with over 40 million under the age of five classed as overweight in 2011. 8 Overweight and obesity are causing major health concerns because of their strong association with a range of non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular disorders, type 2 diabetes and some cancers. Consequently, obesity and overweight are the fifth leading cause of death with 2.8 million adult deaths attributed to being overweight or obese each year. 8 Besides causing major health and welfare concerns, obesity and overweight constitute a substantial economic burden through healthcare cost, reduced productivity at work and sick leave. The annual economic cost has been estimated at $215 billion in the United States in 2010,Reference Hammond and Levine 10 over €10 billion in some European countriesReference Muller-Riemenschneider, Reinhold, Berghofer and Willich 11 and $58.2 billion in Australia in 2008.Reference Colagiuri, Lee and Colagiuri 12

Obesity and changes in dietary habits since the 1980s

Obesity develops as a result of chronic energy imbalance whereby energy intake exceeds energy expenditure. There is an ongoing debate over which side of the equation has the greatest bearing on the obesity epidemic.Reference Millward 13 It has been suggested that sedentary lifestyle rather than increased energy intake was to blame.Reference Prentice and Jebb 14 , Reference Church, Thomas and Tudor-Locke 15 However, studies using the doubly labelled water technique indicate that energy expenditure has not decreased since the 1980s, thereby implying that increased energy intake rather than sedentary behaviour has fuelled the doubling of obesity rates.Reference Westerterp and Speakman 16 The latter findings are in line with a report that energy supply per capita has increased along with obesity prevalence in Western countries between the early 1980s and the mid 1990s.Reference Silventoinen, Sans and Tolonen 17 Furthermore, dietary habits have dramatically shifted in western nations over the same period. For instance, consumption of ‘away from home’ foods has increased in the United States and these foods contain more calories and fat but fewer fibres and minerals compared with foods prepared at home.Reference Guthrie, Lin and Frazao 18 Moreover, the consumption of snacks, soft drinks and pizza has increased at the expense of homemade meals, water and milk.Reference Nielsen, Siega-Riz and Popkin 19 , Reference Nielsen and Popkin 20 It is well characterised that fat and sugar are potent boosters of food palatability, particularly when added together, and drive overconsumption through addiction-like mechanisms.Reference Levine, Kotz and Gosnell 21 , Reference Johnson and Kenny 22 Taste is the first factor influencing consumers’ food choice followed by cost and convenience, which implies that palatability is a primary driver of overeating-induced obesity.Reference Glanz, Basil, Maibach, Goldberg and Snyder 23 Alarmingly, similar shifts in dietary habits are occurring on a global scale and are causing obesity and non-communicable diseases in both high- and low-income countries.Reference Popkin 24 As a result, 60% of the world’s population currently live in countries where overweight and obesity kill more people than undernutrition. 8 Cordain et al.Reference Cordain, Eaton and Sebastian 25 have proposed that such dramatic and sudden changes in eating habits have triggered a discordance between the ancient human genome and the contemporary diet and that this discordance is fuelling obesity and associated non-communicable diseases. These authors have also identified profound alterations in seven key components of the ancestral hominin diet including glycaemic index, micronutrient density, acid–base balance, sodium–potassium ratio and fatty acid, macronutrient and fibre content. They suggest that complex interactions between all of these nutritional characteristics are causing non-communicable diseases as opposed to individual macro- or micronutrients acting in isolation.Reference Cordain, Eaton and Sebastian 25 It is therefore important to take these nutritional characteristics into account when developing animal models of human obesity.

Intrauterine and neonatal origins of obesity

The aetiology of chronic energy imbalance that ultimately leads to overweight and obesity is complex. Genetic, environmental and socio-economic factors have been implicated together with interactions between these factors.Reference Atkinson 26

In addition to these factors, growing evidence suggests that the intrauterine milieu and neonatal nutrition play important roles in initiating obesity and related disorders in the offspring, as reviewed by others.Reference Oken 27 – Reference Fall 29 For example, maternal pre-pregnancy obesity is associated with macrosomia, childhood obesity and the metabolic syndrome, while excessive gestational weight gain is linked with offspring overweight and adiposity, irrespective of pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI).Reference Guelinckx, Devlieger, Beckers and Vansant 30 – Reference Wrotniak, Shults, Butts and Stettler 34 More importantly perhaps, the maternal obesogenic effects on the offspring have been shown to persist into adolescence and adult life.Reference Oken, Rifas-Shiman, Field, Frazier and Gillman 35 , Reference Hochner, Friedlander and Calderon-Margalit 36 In addition to the intrauterine environment, lactation also appears to be an important period for the priming of obesity.Reference Crume, Ogden and Mayer-Davis 37 Breastfeeding has been shown to offer some protection against childhood obesity over formula feeding.Reference Arenz, Ruckerl, Koletzko and von Kries 38 However, the evidence is sometimes conflicted due to numerous confounding factors.Reference Tounian 39 Direct analysis of milk quality and correlation with infant body composition may provide more robust evidence. For instance, high maternal BMI is associated with changes in breast milk quality and increased fat mass in children.Reference Fields and Demerath 40 , Reference Makela, Linderborg, Niinikoski, Yang and Lagstrom 41 Furthermore, human and animal studies have shown that milk from diabetic mothers affects the development of hypothalamic appetite regulation, promotes overweight and impairs glucose tolerance in progeny.Reference Fahrenkrog, Harder and Stolaczyk 42 , Reference Plagemann, Harder, Franke and Kohlhoff 43 Animal studies have begun to elucidate the underlying mechanisms linking maternal obesity and offspring ill health. Rat studies carried out by our group have helped to establish that maternal overnutrition in pregnancy and lactation promotes the early onset of obesity in the offspring through exacerbating preference for energy dense foods rich in fat, sugar and salt.Reference Bayol, Farrington and Stickland 44 This is likely mediated through alternations in the development of hedonic appetite regulation in the central nervous system.Reference Ong and Muhlhausler 45 Such changes in feeding behaviour reflect those currently occurring on a global scale in the human populationReference Popkin 24 and are causing non-communicable diseases in both humans and clinically relevant animal models.Reference Bayol, Farrington and Stickland 44 , Reference Bayol, Simbi, Bertrand and Stickland 46 – Reference Howie, Sloboda, Reynolds and Vickers 49

The prevalence of overweight and obesity in women of childbearing age has been increasing in parallel with global obesity rates. In Australia, around 35% of these women are classed as overweight or obese.Reference Cameron, Welborn and Zimmet 50 , Reference Laws and Hilder 51 Moreover, the prevalence of excessive gestational weight gain is high in women with both normal and high pre-pregnancy BMIs.Reference de Jersey, Nicholson, Callaway and Daniels 52 These alarming figures warrant the development of interventions aimed not only at preventing maternal obesity and/or excessive gestational weight gain but also at reversing any developmental defects associated with being born to an obese/overnourished mother. Understanding the underlying biological mechanisms involved is crucial for the development of targeted interventions.

Importance of skeletal muscle fitness for general health

Although the detrimental effects of maternal obesity and/or excessive gestational weight gain on the offspring are beginning to be well documented, most studies to date have been predominantly focussed on appetite regulation, adiposity and cardiovascular dysfunction.Reference Oken 27 – Reference Fall 29 , Reference Armitage, Poston and Taylor 53 Very few studies have considered the impact on skeletal muscle development and health into adult life. In fact, the role of skeletal muscle in general health and obesity prevention has long been overlooked, albeit it is gradually gaining recognition.Reference Wolfe 54 , Reference McCarthy 55

Numerous studies have shown strong associations between poor skeletal muscle health and non-communicable diseases. For example, cardiac failure, cancer and type 2 diabetes are all associated with loss of muscle mass and/or strength.Reference Benson, Torode and Singh 56 – Reference Leenders, Verdijk and van der Hoeven 58 Conversely, muscle mass is a key determinant of recovery in patients with cardiac failure and cancer.Reference Dodson, Baracos and Jatoi 57 , Reference Kadar, Albertsson, Areberg, Landberg and Mattsson 59

In middle-aged adults, muscular strength, a non-invasive measure of skeletal muscle fitness, is inversely associated with premature death as well as obesity, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, cardiovascular disease and the metabolic syndrome.Reference Artero, Lee and Lavie 60 Furthermore, muscle mass index, namely, muscle mass measured by bioelectrical impedance divided by height squared, predicts longevity.Reference Srikanthan and Karlamangla 61 In the elderly, sarcopenia, which is defined by the age-related loss of muscle mass, is associated with loss of muscle strength, physical disability, falls, insulin resistance and death.Reference Narici and Maffulli 62 In sarcopenia, the loss of muscle mass is accompanied by myosteatosis, the accumulation of lipids and connective tissue within muscle tissue. Myosteatosis reduces the net contractile muscle area, which partly explains muscle weakness.Reference Narici and Maffulli 62 Furthermore, intramuscular lipid infiltrations are believed to promote skeletal muscle insulin resistance and contribute to the development of type 2 diabetes.Reference Narici and Maffulli 62 , Reference Hegarty, Furler, Ye, Cooney and Kraegen 63 Muscle weakness and insulin resistance are further exacerbated in ‘sarcopenic obesity’ whereby the loss of muscle mass is accompanied by increased adiposity, although the condition remains to be thoroughly defined.Reference Choi 64 – Reference Zamboni, Mazzali, Fantin, Rossi and Di Francesco 66 Evidence of a direct cause and effect relationship between obesity and sarcopenia has been shown experimentally in an animal model whereby ageing rats rendered obese with a high fat diet exhibit exacerbated sarcopenia and myosteatosis compared with age-matched rats fed a lean diet.Reference Bollheimer, Buettner and Pongratz 67

The association between skeletal muscle fitness and general health is not solely reported in the elderly, the middle-aged or in those suffering from chronic diseases. Several studies have shown similar associations in children and adolescents, as summarised in Table 1. In 9–15-year-olds, skeletal muscle fitness assessed by measurements of explosive, isometric and endurance strength is inversely associated with metabolic health.Reference Steene-Johannessen, Anderssen, Kolle and Andersen 68 The metabolic parameters measured include blood pressure, triglyceride, cholesterol, insulin resistance and weight circumference. The inverse association is further exacerbated in overweight children with low muscle fitness scores.Reference Steene-Johannessen, Anderssen, Kolle and Andersen 68 In line with these findings, a study of the HELENA cohort comprising 709 adolescents aged 12.5–17.5 years shows an inverse association between muscular fitness (handgrip strength and long jumps) and metabolic health parametersReference Artero, Ruiz and Ortega 69 (Table 1). There again, metabolic health is improved in overweight children with greater muscle fitness scores.Reference Artero, Ruiz and Ortega 69 Similarly, muscle strength in 10–15-year-old children and adolescents is inversely associated with insulin resistance and central adiposity.Reference Benson, Torode and Singh 56

Table 1 Correlation between skeletal muscle fitness and metabolic health in children and adolescents

A study of the AVENA cohort reports that muscle fitness rather than physical activity levels is associated with a better cardiovascular and metabolic profile in adolescent girls aged 13–18.5 years.Reference Garcia-Artero, Ortega and Ruiz 70 The authors propose that ‘innate physical constitution’ rather than lifestyle is a key determinant of metabolic health.Reference Garcia-Artero, Ortega and Ruiz 70 However, physical activity in childhood has been shown to improve cardiovascular and metabolic health in adolescence and to reduce intramuscular fat; therefore, some plasticity exists.Reference Janz, Dawson and Mahoney 71 , Reference Farr, Van Loan, Lohman and Going 72 Indeed, Fernandes and ZanescoReference Fernandes and Zanesco 73 have reported that physical activity in early life is associated with improved metabolic health parameters in adulthood.

Skeletal muscle, obesity and insulin resistance

Skeletal muscle accounts for about 20% of energy expenditure.Reference Ravussin, Lillioja, Anderson, Christin and Bogardus 74 , Reference Zurlo, Larson, Bogardus and Ravussin 75 However, this contribution varies considerably depending on skeletal muscle mass and metabolic requirements.Reference Gardner and Rhodes 1 , Reference Wolfe 54 As reviewed by Wolfe, resting energy expenditure is the largest component of total energy expenditure and is dependent upon muscle mass and protein turnover rates.Reference Wolfe 54 Muscle mass varies among individuals and can range from 35 to 50 kg in a young man to <13 kg in an elderly woman. On that account, the energy required to support muscle protein synthesis is around 485 kcal/day in a muscular young man but only 120 kcal/day in an elderly woman. If activity and diet were equal between these two individuals, the difference in energy expenditure due to muscle mass would lead to a net gain or loss of 1.4 kg of fat per month, although it is unclear whether the energy required to convert excess energy into fat was taken into account in these calculations. A more modest and realistic 10 kg difference in lean mass leads to a difference in energy expenditure of about 100 kcal/day, which translates into ∼4.7 kg of body fat mass accumulated over 1 year, if activity and diet remain constant. Therefore, maintenance of adequate muscle mass and protein turnover contributes to body weight maintenance and the prevention of obesity.Reference Wolfe 54

Nonetheless, muscle mass and protein turnover are affected in obesity, as reviewed by Guillet et al.Reference Guillet, Masgrau, Walrand and Boirie 76 Human obesity is generally associated with increased lean mass along with fat mass, except in sarcopenic obesity.Reference Forbes and Welle 77 – Reference Auyeung, Lee, Leung, Kwok and Woo 79 However, lean mass measurements do not reflect muscle quality and the non-contractile muscle compartment, which is indicative of myosteatosis, is not usually assessed or taken into account in these measurements.Reference Narici and Maffulli 62 In fact, muscle strength relative to fat-free mass or body weight is reduced in obese individuals.Reference Lafortuna, Maffiuletti, Agosti and Sartorio 78 , Reference Hulens, Vansant and Lysens 80 Furthermore, intermuscular adipose tissue (adipose tissue located between muscle fibres), is associated with obesity, insulin resistance and reduced contractile function but not with muscle mass in humans.Reference Goodpaster, Thaete and Kelley 81 – Reference Lee, Kim, White, Kuk and Arslanian 83 In animal models, where muscle mass measurements are perhaps more direct and accurate, obesity is usually associated with either reduced or unchanged muscle mass depending on whether obesity is genetic (leptin or leptin receptor mutants) or diet-induced, respectively.Reference Stickland, Batt, Crook and Sutton 84 – Reference Suga, Kinugawa and Takada 88 The effects of obesity on skeletal muscle mass may depend on how long an individual has been affected by obesity. In rats, if obesity is maintained over an extended period (16 weeks), it leads to skeletal muscle fibre atrophy.Reference Sishi, Loos and Ellis 89 Furthermore, Masgrau et al.Reference Masgrau, Mishellany-Dutour and Murakami 90 have studied the chronological effects of diet-induced obesity on skeletal muscle mass and protein synthesis in adult rats. They have shown that as obesity develops, namely during the ‘dynamic phase’ (1–16 weeks), muscle mass and protein synthesis are initially increased. This is probably an anabolic adaptation to mechanical overload as a result of increased body mass. However, once obesity is established or ‘static phase’ (16–24 weeks), weight gain stabilises, adipose tissue ceases to expand and muscle mass and protein synthesis decrease. The static phase is also characterised by reduced mitochondrial protein synthesis and increased intramuscular lipid infiltrations. These defects are muscle specific and occur in the fast glycolytic tibialis anterior muscle but not in the slow oxidative soleus.Reference Masgrau, Mishellany-Dutour and Murakami 90 This implies that the greater capacity for lipid oxidation in the soleus muscle may offer some protection against the deleterious effects of obesity on skeletal muscle health. Nonetheless, several studies have shown that the maintenance of oxidative metabolism is compromised in skeletal muscles of obese individuals and the condition is associated with a fibre type shift characterised by an increased proportion of type 2B (glycolytic) and/or a reduction in type 1 (oxidative) muscle fibres.Reference Tanner, Barakat and Dohm 91 – Reference Wade, Marbut and Round 95

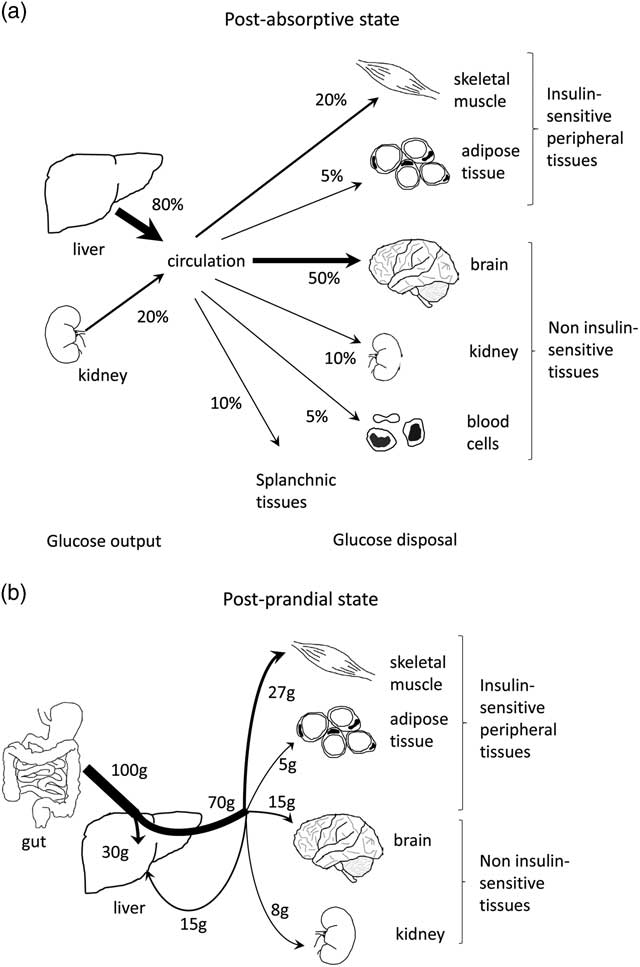

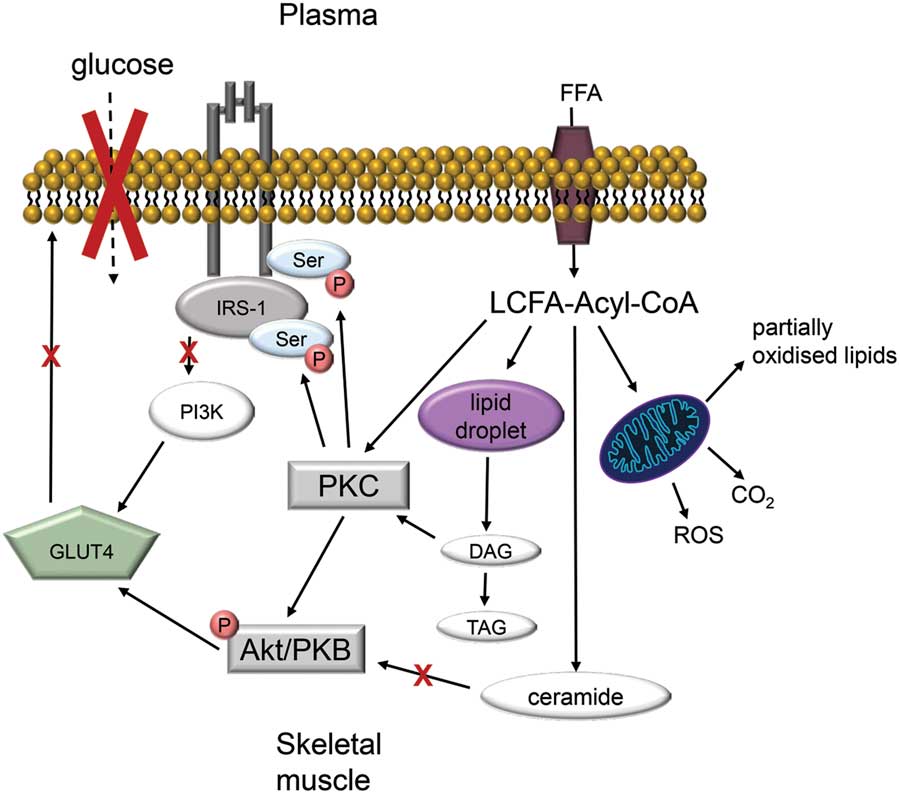

As well as being an important site of energy expenditure, skeletal muscle plays a significant role in regulating whole-body glucose metabolism. In the post-absorptive state, around 20% of whole-body glucose disposal occurs in skeletal muscle, with non-insulin-responsive tissues such as the brain accounting for the majority of glucose uptakeReference Cherrington 96 , Reference Shrayyef and Gerich 97 (Fig. 1a). In the postprandial state, about a third of ingested glucose is taken up and disposed of by skeletal muscleReference Cherrington 96 , Reference Shrayyef and Gerich 97 (Fig. 1b). Of the glucose taken up by muscle, 15% is released as glycolytic intermediates such as lactate and alanine, 50% is oxidised and 35% is stored as glycogen.Reference Kelley, Mitrakou and Marsh 98 In patients with type 2 diabetes, the rate of glucose disposal following a meal is reduced,Reference Basu, Dalla Man and Basu 99 which may be related to defects in skeletal muscle glucose handling due to the presence of insulin resistance. Indeed, post-prandial skeletal muscle glucose clearance is reduced in type 2 diabetic individualsReference Gerich, Mitrakou and Kelley 100 and is associated with impaired storage of glucose as glycogen.Reference Carey, Halliday, Snaar, Morris and Taylor 101 In fact, it has been proposed that impaired glycogen synthesis in skeletal muscle is the primary defect that precedes pancreatic β-cell failure and leads to type 2 diabetes.Reference DeFronzo and Tripathy 4 Although the mechanisms leading to impaired glucose metabolism are not entirely clear, there is an association between insulin resistance and defective lipid handling in skeletal muscle.Reference Shaw, Clark and Wagenmakers 102 – Reference Coen and Goodpaster 104 Actually, there is strong evidence linking the accumulation of intramyocellular lipids such as triacylglycerol, diacylglycerol, long-chain fatty acyl-CoAs and ceramides with defects in muscle insulin action.Reference Wolfe 54 , Reference Consitt, Bell and Houmard 103 It is thought these lipid intermediates cause activation of inflammatory and/or stress signalling pathways, which ultimately impinge on the ability of insulin to stimulate muscle glucose metabolism (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1 Contribution of skeletal muscle in glucose disposal in the post-absorptive (fasted) and post-prandial (fed) states. (a) Post-absorptive glucose metabolism. The liver and kidneys contribute ∼80% and 20% of glucose output, respectively. Most glucose is then removed from the circulation by non-insulin-sensitive tissues such as the brain (50%), renal medulla (10%), blood cells (10%) and the splanchnic bed (10%). The remaining 20–25% are taken up by skeletal muscles and adipose tissue. (b) Post-prandial glucose metabolism. Following an oral glucose load of 100 g, ∼30 g are taken up by the liver and 70 g are released into the circulation. Of these 70 g, 27 g (40%) are taken up by skeletal muscle, 5 g (7%) by adipose tissue, 15 g (20%) return to the liver and the remaining 23 g (33%) are taken up by the kidneys, skin and blood cells. Figure adapted from Shrayyef and Gerich.Reference Shrayyef and Gerich 97

Fig. 2 Model of skeletal muscle insulin-resistance in obesity. Excess plasma free fatty acid (FFA) leads to the intramuscular accumulation of long-chain fatty acid (LCFA)-Acyl CoAs. Because of low energy demand, LCFA-Acyl CoAs are incompletely oxidised by mitochondria thus form large lipid droplets. Lipolysis of these droplets generates lipotoxic precursors such as diacyglycerol (DAG) and ceramide. Both LCFA-Acyl-CoA and DAG activate protein kinase C (PKC), which stimulates serine phosphorylation. This decreases the association between insulin receptor substrate 1 and phosphatidylinosytol (PI3K). Ceramide impair insulin signalling via decreased Akt/protein kinase B (PKB) phosphorylation. The resulting downregulation of insulin signalling prevents the translocation of glucose transporter (GLUT) 4 to the plasma membrane and glucose uptake into skeletal muscle (adapted from Shaw et al.,Reference Shaw, Clark and Wagenmakers 102 Consitt et al. Reference Consitt, Bell and Houmard 103 and Coen and GoodpasterReference Coen and Goodpaster 104 ).

Given the importance of skeletal muscle fitness for metabolic health, various strategies are being developed in adults to maintain or increase skeletal muscle mass, protein synthesis and lipid oxidation, with the aim of increasing energy expenditure to treat obesity and insulin resistance. These strategies include hormonal therapy, exercise and nutritional interventions as reviewed by Wolfe.Reference Wolfe 54 However, muscle mass and metabolism are influenced by maternal nutrition during pregnancy and lactation (see later). Consequently, efforts should also be targeted at optimising maternal nutrition to maximise skeletal muscle development and health in the developing offspring.

Skeletal muscle development and postnatal growth

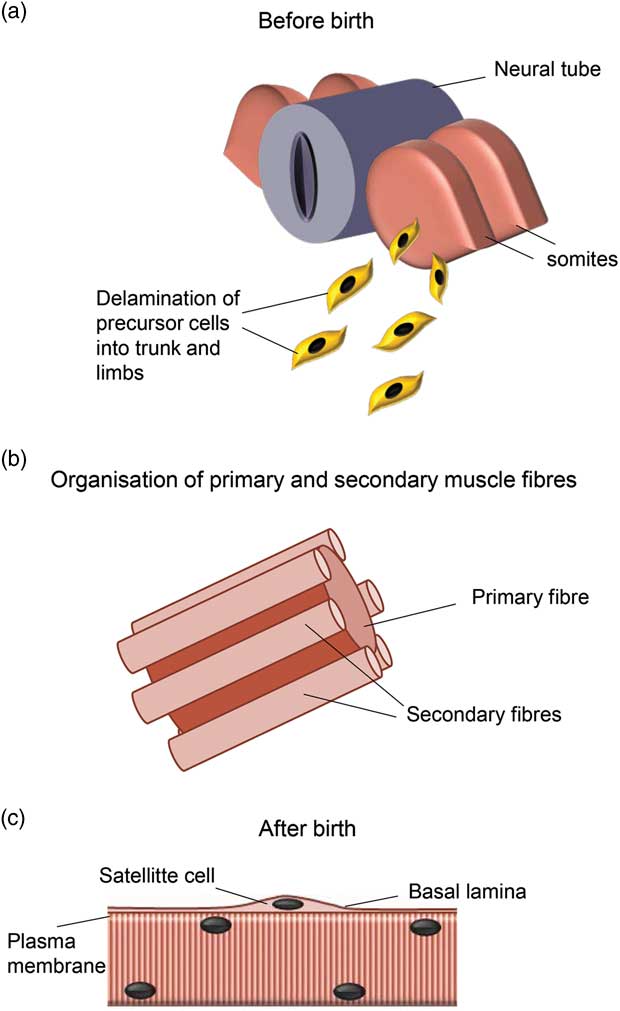

To understand how maternal obesity may affect skeletal muscle development, growth and function into adult life, it is important to get an insight into how this tissue develops (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Skeletal muscle development. During early embryogenesis, skeletal muscle precursor cells delaminate from the somites located on either side of the neural tube and migrate into the limb buds and trunk (a). Muscle fibre formation occurs in waves and ends before birth or shortly thereafter depending on species. Primary myofibres form first and act as scaffolding for secondary myofibres (b). After birth, myofibres continue to grow by hypertrophy, which initially involves the activation of satellite cells located under the basal lamina (c). Figure adapted from PartridgeReference Partridge 121 and Maltin et al.Reference Maltin, Delday, Sinclair, Steven and Sneddon 5

Early myogenesis

During embryonic development, mammalian skeletal muscles originate from the condensation of paraxial mesoderm into epithelial structures called somites (reviewed by Bismuth et al. Reference Bismuth and Relaix 105 and Buckingham et al. Reference Buckingham, Bajard and Chang 106 ). The sclerotome (ventral part of the somite) gives rise to cartilage and bone of the vertebral column and ribs, while the dermomyotome (dorsal part of the somite) forms skeletal muscle progenitor cells and the dermis.Reference Buckingham, Bajard and Chang 106 , Reference Olsen, Reginato and Wang 107 The borders of the dermomyotome undergo a transition from an epithelial to a mesenchymal structure and forms a third compartment called the myotome.Reference Bismuth and Relaix 105 The dorsal-medial (epaxial) parts of the myotome and demomyotome generate the back muscles, whereas the ventro-lateral parts (hypaxial) give rise to muscles of the limbs and the rest of the trunk.Reference Bismuth and Relaix 105 Somitic cells are therefore pluripotent and their specification to a particular lineage is a competitive process that is modulated by a number of signalling pathways including sonic hedgehog (skeletal muscle specification), Notch (smooth muscle), Nkx3.2 (cartilage), TGFβ and Bmp2 acting through Smad3 and Smad1/5 (bone) and Prdm16 (brown adipocytes); for a review see Buckingham et al. Reference Buckingham and Vincent 108 For example, TGFβ and Bmp2 signalling promotes osteogenesis and inhibits myogenesis,Reference Aziz, Miyake, Engleka, Epstein and McDermott 109 whereas Prdm16 favours differentiation of common Myf5 expressing precursors down the brown adipose lineage at the expense of skeletal muscle.Reference Seale, Bjork and Yang 110 It is unknown whether maternal obesity affects stem cell commitment shift during the early stages of development.

During limb myogenesis, muscle precursor cells delaminate and migrate from the hypaxial part of the dermomyotome into the limb buds; this is under the control of c-met, whose transcription is regulated by the paired box gene product Pax3, and its ligand hepatocyte growth factor.Reference Buckingham, Bajard and Chang 106 During migration, muscle precursors proliferate until they reach their final destination in the limb.Reference Bismuth and Relaix 105 They then begin to express the myogenic regulatory factor Myf5 followed by MyoD, myogenin and MRF4, which regulate myoblasts fusion and differentiation into multinucleated muscle fibres that ultimately express functional contractile proteins such as myosin heavy chains.Reference Bismuth and Relaix 105

Muscle fibre formation

The formation of skeletal muscle fibres (hyperplasia) occurs in two waves in most mammalian species but a third wave has been reported in larger mammals such as humans and pigs.Reference Berard, Kalbe, Losel, Tuchscherer and Rehfeldt 111 , Reference Standring, Borley and Collins 112 The first wave of myoblast fusion gives rise to primary (embryonic) muscle fibres, which define the future muscle by extending from tendon to tendon. This occurs in the early stages of development, namely, around embryonic days 14–17 in rats and mice and between gestational weeks 8–10 in humans.Reference Standring, Borley and Collins 112 – Reference Ontell, Bourke and Hughes 116 Primary fibres then act as scaffolding for secondary (foetal) fibres as shown in Fig. 3. Secondaries initially form beneath the basal lamina of the primaries then grow longitudinally to reach the tendons and acquire their own basement membranes.Reference Duxson, Usson and Harris 117 Secondary fibres form between embryonic day 17 and the early neonatal period in rats and miceReference Wigmore and Dunglison 113 , Reference Ross, Duxson and Harris 115 , Reference White, Bierinx, Gnocchi and Zammit 118 and between gestational weeks 10 and 18 in humans.Reference Barbet, Thornell and Butler-Browne 114 In humans, tertiary fibres begin to form around embryonic weeks 16–17 and become independent by week 23.Reference Standring, Borley and Collins 112

Myogenesis ends with the cessation of de novo fibre formation (hyperplasia), such that the majority of muscle fibres that constitute a given muscle is usually set by birth or shortly thereafter; this will determine adult muscle fibre number and influence adult muscle mass.Reference Maltin, Delday, Sinclair, Steven and Sneddon 5 , Reference Rehfeldt, Fiedler, Dietl and Ender 6 , Reference Wigmore and Dunglison 113 , Reference Ross, Duxson and Harris 115 , Reference Stickland 119 From the neonatal period, skeletal muscles continue to grow predominately by hypertrophy, namely, through an increase in skeletal muscle fibre size rather than an increase in their number.Reference Ross, Duxson and Harris 115 , Reference White, Bierinx, Gnocchi and Zammit 118

Postnatal muscle growth

Muscle fibre hypertrophy during postnatal muscle growth involves the addition of new myonuclei together with protein accretion.Reference Schiaffino, Dyar, Ciciliot, Blaauw and Sandri 120 , Reference Partridge 121 New myonuclei come from satellite cells, which are a subset of myoblasts that form during the later stages of embryogenesis.Reference Standring, Borley and Collins 112 These myoblasts do not initially fuse with muscle fibres. Instead, they remain in a quiescent state underneath the basal lamina of adjacent fibres and act as a pool of ‘stem’ cells that are recruited during growth and regeneration.Reference Standring, Borley and Collins 112 , Reference Brack and Rando 122 During postnatal growth, some satellite cells are activated and proliferate. Some daughter cells return to quiescence to replenish the pool of satellite cells while others fuse to adjacent muscle fibres.Reference Schiaffino, Dyar, Ciciliot, Blaauw and Sandri 120 Fused satellite cells thereby donate their nuclei to the myofibres and contribute to protein synthesis and hypertrophy.Reference Schiaffino, Dyar, Ciciliot, Blaauw and Sandri 120 Although satellite cells are not essential for muscle hypertrophy,Reference McCarthy, Mula and Miyazaki 123 under normal physiological conditions, the rate of satellite activation and fusion is high during the first 3 weeks postpartum in mice.Reference White, Bierinx, Gnocchi and Zammit 118 Beyond this point until adulthood, muscle fibre volume increases without further addition of myonuclei.Reference White, Bierinx, Gnocchi and Zammit 118 In humans, the contribution of satellite cells to postnatal muscle growth is a bit more complicated to study than in mice but appears to continue until 15–18 years.Reference Partridge 124

Along with satellite cell activation, muscle fibre hypertrophy involves a net increase in protein synthesis over protein degradation. This is mostly regulated by two antagonist pathways, namely, the insulin-like growth factor 1-phosphoinositide-3-kinase-Akt/protein kinase B-mammalian target of rapamysin (IGF1-PI3K-Akt/PKB-mTOR), which promotes growth, and the myostatin-Smad3 pathway, which acts as an inhibitor of growthReference Schiaffino, Dyar, Ciciliot, Blaauw and Sandri 120 (Fig. 4). The role of the IGF-1 pathway in muscle hypertrophy is particularly evident in mutant mice that lack IGF-1 receptors in skeletal muscle. These mice exhibit growth restriction together with a reduction in both skeletal muscle fibre number and size, with a preferential loss of type 1 fibres.Reference Mavalli, DiGirolamo and Fan 125 This is accompanied with severely impaired contractile performance.Reference Mavalli, DiGirolamo and Fan 125 Conversely, evidence that the myostatin pathway is a strong inhibitor of muscle growth is illustrated in myostatin null mice that exhibit an accelerated myogenic programme with increased fibre number and size into adult life.Reference Matsakas, Otto, Elashry, Brown and Patel 126

Fig. 4 Mechanisms of postnatal skeletal muscle growth. (a) Satellite cells are quiescent muscle precursors located under the basal lamina. Upon activation, they proliferate. Some daughter cells return to quiescence to replenish the satellite cell pool, whereas others fuse with the adjacent muscle fibre and donate their nuclei to contribute to protein synthesis and thereby skeletal muscle fibre growth. Each stage of satellite cell differentiation is regulated by factors involved in myogenesis. RBP-J and miR-489 are required to maintain satellite cells in a quiescent state while Spry1 and Notch-3 regulate their return to quiescence from a proliferating state. Myf5 is involved in satellite cell proliferation while MyoD and myogenin regulate their differentiation and expression of functional contractile proteins such as MyHCs. (b) Various signalling pathways are believed to converge around Akt/mTOR to regulate skeletal muscle hypertrophy through transcriptional regulation (arrow linking mTOR to a myonucleus). The two major regulatory pathways are IGF-1 acting through PI3K and follistatin acting through myostatin inhibition (heavy dotted lines). Additional pathways include SRF, PA and nNOS. miR-489, mouse micro RNA-489; Myf5, myogenic factor 5; myHC, myosin heavy chain; MyoD, myogenic differentiation; Notch-3, neurogenic locus notch homologue protein 3; Pax7, paired box protein 7; RBP-J, recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin kappa J region; Spry1, protein sprouty homologue 1. Figure adapted from Brack and Rando.Reference Brack and Rando 122 ; ACVRI/II, activin receptor I/II; akt, serine/threonine protein kinase; Fzd7, frizzled family receptor 7; IGF1, insulin-like growth factor-1; IGF1R, insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor; IL, interleukin; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin (serine/threonine kinase); new mn, newly fused myonucleus; nNOS, neuronal nitric oxide synthase; NO, nitric oxide; PA, phosphatidic acid; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase; SC, satellite cell; SRF, serum response factor; SSC, satellite stem cell; TRPV1, transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1; wnt7a, wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 7A. Figure adapted from Schiaffino et al. Reference Schiaffino, Dyar, Ciciliot, Blaauw and Sandri 120

It is important to note that differentiated skeletal muscle tissue is heterogeneous and not only consists of skeletal muscle fibres but also of vascular and connective tissues, including intramuscular adipocytes. Differentiated muscle tissue also contains a heterogeneous population of resident progenitors capable of adopting diverging cell fates.Reference Judson, Zhang and Rossi 127 Some of these resident progenitors contribute to excessive ectopic adipogenesis in a number of muscle pathologies including muscular dystrophies, obesity, type 2 diabetes and sarcopenia.Reference Uezumi, Ikemoto-Uezumi and Tsuchida 128 Evidence suggests that early life nutrition may affect specification and differentiation of these resident progenitors (see later).

Effects of maternal diet-induced obesity on skeletal muscle development and growth

Maternal obesity, skeletal muscle development and function

The negative effects of maternal undernutrition on skeletal muscle development, growth and function into adult life are quite well documented and have been reviewed by others.Reference Maltin, Delday, Sinclair, Steven and Sneddon 5 , Reference Sayer, Syddall and Martin 129 , Reference Brown 130

For example, several studies have shown that severe maternal undernutrition during pregnancy permanently reduces skeletal muscle fibre number and size in both small and large mammals, including humans.Reference Bedi, Birzgalis, Mahon, Smart and Wareham 131 – Reference Montgomery 135 This is of significance because reduced skeletal muscle fibre number is associated with low birth weight, slower postnatal growth rate and lower muscle mass into adult life.Reference Maltin, Delday, Sinclair, Steven and Sneddon 5 , Reference Rehfeldt, Fiedler, Dietl and Ender 6 , Reference Dwyer, Fletcher and Stickland 136 – Reference Paredes, Kalbe and Jansman 138 When undernutrition occurs after weaning in rats, no such permanent deficit in muscle fibre number is observed, implying that there is a window of development during which muscle tissue is particularly vulnerable.Reference Bedi, Birzgalis, Mahon, Smart and Wareham 131 Maternal undernutrition during pregnancy does not appear to affect the number of primary fibres that form in a given muscle but secondary fibre number is reduced.Reference Wigmore and Dunglison 113 , Reference Bedi, Birzgalis, Mahon, Smart and Wareham 131 , Reference Wilson, Ross and Harris 132 In addition to alterations in muscle fibre number, maternal undernutrition and/or protein restriction during pregnancy have been shown to affect skeletal muscle fibre metabolic profile,Reference Mallinson, Sculley and Craigon 139 – Reference Huber, Miles and Norman 141 while intrauterine growth restriction through placental surgery affects insulin signalling in offspring skeletal muscle.Reference Muhlhausler, Duffield and Ozanne 142

The effects of maternal obesity and gestational overnutrition on skeletal muscle development in the offspring are much less well characterised but appear to be just as detrimental. Using a clinically relevant animal model that reflects the current global changes in dietary habits in humans, our group has shown that weanling rats born to mothers fed a palatable obesogenic diet during pregnancy and lactation exhibit reduced skeletal muscle cross-sectional area with a deficit in skeletal muscle fibre number along with increased intramuscular fat content.Reference Bayol, Farrington and Stickland 44 These structural defects observed at weaning progress towards impaired muscle contractile function, characterised by reduced twitch and tetanic tensions at the end of adolescence.Reference Bayol, Macharia, Farrington, Simbi and Stickland 143 Taken together the data show that the healthy contractile muscle compartment is compromised at the expense of ectopic adipogenesis in offspring born to overnourished dams. In these offspring, limb skeletal muscle mass was not significantly affected, however, other rodent studies, whereby maternal overeating was induced before conception using diets either rich in both fat and sugar or in sucrose alone, have reported a reduction is skeletal muscle mass relative to body weight.Reference Samuelsson, Matthews and Argenton 48 , Reference Samuelsson, Matthews, Jansen, Taylor and Poston 144

Underlying mechanisms

Du and colleagues have begun to study some of the underlying mechanisms that mediate the effects of maternal obesity on skeletal muscle development in the offspring. Using a sheep model, they have shown that maternal obesity induced by increasing food ration ad libitum in pregnant ewes led to increased foetal skeletal muscle mass, however, muscle quality was impaired.Reference Tong, Yan and Zhu 145 More specifically, at 75 days of gestation, foetuses from obese ewes had smaller primary fibre diameters, which is usually associated with fewer secondary fibre number, although these were not yet identifiable this early in development.Reference Tong, Yan and Zhu 145 Along with primary fibre atrophy, these foetuses exhibited increased intramuscular space that progressed towards fibrosis and ectopic adipogenesis by 22 months of age.Reference Tong, Yan and Zhu 145 , Reference Yan, Huang and Zhao 146

Reduced myogenesis in 75-day sheep foetuses from obese ewes appears to be partly mediated through downregulation of myogenic factor expression (MyoD and myogenin) and alterations in Wnt/β-catenin signalling.Reference Tong, Yan and Zhu 145 The concomitantly increased fibrosis is characterised by intramuscular collagen accretion and cross-linking and appears to be mediated through low-grade inflammation and increased TGF-β signalling.Reference Huang, Zhao and Yan 147 Fibrosis, which is also a feature of muscle aging, is linked to impaired skeletal muscle contractile function, however, muscle force measurements have not been reported in this model.Reference Purslow 148 – Reference Goldspink, Fernandes, Williams and Wells 153

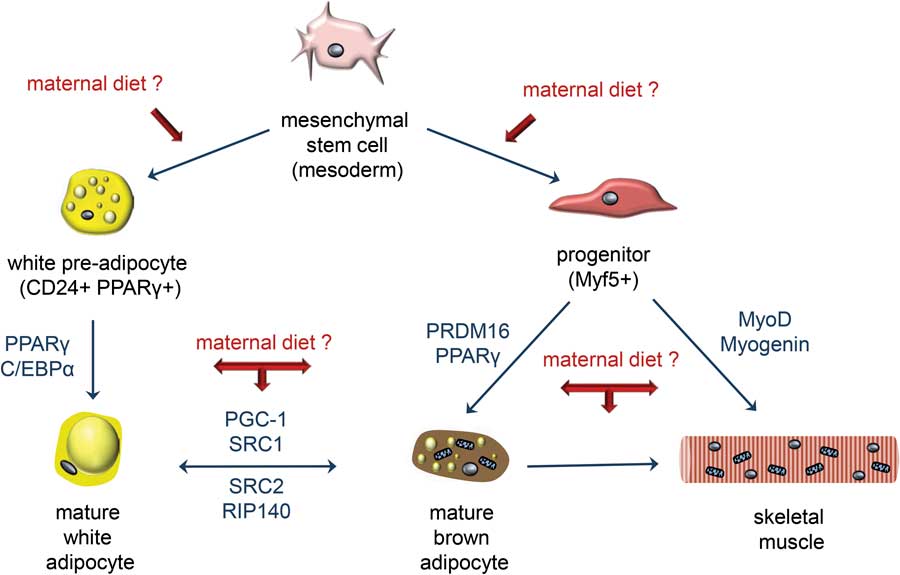

Along with fibrosis, sheep offspring born to overnourished mothers exhibit increased intramuscular fat accumulation together with raised expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), a nuclear receptor that regulates adipocyte differentiation;Reference Yan, Huang and Zhao 146 our group has reported similar findings in rats.Reference Bayol, Farrington and Stickland 44 Both studies therefore indicate that maternal obesity may impair myogenesis via stem cell commitment shift away from myogenesis in favour of ectopic adipogenesis.Reference Du, Yan, Tong, Zhao and Zhu 154 , Reference Bayol, Simbi and Stickland 155 It is well characterised that ectopic adipogenesis is associated with myofibre destruction and is present in several muscular pathologies such as type 2 diabetes and sarcopenia.Reference Uezumi, Ikemoto-Uezumi and Tsuchida 128 Mesenchymal platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRα) positive progenitor cells, distinct from satellite cells, have been identified as major contributors to ectopic fat accumulation in skeletal muscle.Reference Uezumi, Fukada, Yamamoto, Takeda and Tsuchida 156 Their differentiation into adipocytes is inhibited by factors released by satellite cells in vivo, which further highlights the competition between myogenesis v. adipogenesis.Reference Uezumi, Fukada, Yamamoto, Takeda and Tsuchida 156 High insulin conditions promote the adipogeneic differentiation of these cells in vitro. Reference Uezumi, Ikemoto-Uezumi and Tsuchida 128 Furthermore, high glucose conditions drive uncommitted muscle-derived precursors to form adipose depots and this appears to be mediated via increased levels of reactive oxygen species and downstream effectors such as protein kinase C-β.Reference Aguiari, Leo and Zavan 157 It is unclear whether these progenitor cells also express PDGFRα. In addition to high glucose and insulin conditions, fatty acid overload also impedes myogenesis. Overexpression of lipoprotein lipase, a regulator of fatty acid transport, in the murine C2C12 myoblast cell line induces intramyocellular accumulation of free fatty acids.Reference Tamilarasan, Temmel and Das 158 This leads to an almost complete loss of myogenic potential characterised by impaired fusion and reduced expression of Pax7, a paired box transcription factor involved in myogenic specification, and of the myogenic factors MyoD and myogenin.Reference Tamilarasan, Temmel and Das 158 When lipoprotein lipase is overexpressed in skeletal muscle tissue in vivo, it leads to reduced skeletal muscle mass, impaired physical endurance, increased protein degradation and apoptosis. Moreover, skeletal muscle regenerative capacity is diminished in these mice, which further illustrates the lipotoxic effects on satellite cell activation.Reference Tamilarasan, Temmel and Das 158 The negative effects of other lipid species such as ceramides on myogenesis have been demonstrated in a number of in vitro studies and increased mitochondrial lipid oxidation appears to protect against such lipotoxicity.Reference Mebarek, Komati and Naro 159 – Reference Henique, Mansouri and Fumey 161 Some of these lipotoxic effects on myoblasts have been reviewed by Akhmedov and Berdeaux.Reference Akhmedov and Berdeaux 162

Evidence that obesity impairs the myogenic programme in vivo is further supported by muscle regeneration studies in animal models of obesity.Reference Akhmedov and Berdeaux 162 Following injury, muscle stem cells and satellite cells are activated to form new muscle fibres and replace damaged ones.Reference Brack and Rando 122 , Reference Charge and Rudnicki 163 Upon activation, these stem cells recapitulate some aspects of the embryonic myogenic differentiation programmeReference Brack and Rando 122 , Reference Charge and Rudnicki 163 and several studies have shown that these processes are impaired in obese rodents.Reference Akhmedov and Berdeaux 162 For example, mice fed a high fat diet over 8 months exhibit reduced muscle weight and smaller regenerated fibres following cardiotoxin injury.Reference Hu, Wang and Lee 164 Intramuscular fibrosis is concomitantly increased.Reference Hu, Wang and Lee 164 Similarly, early life high fat feeding leads to a reduction in skeletal muscle precursor cells frequency and, following freeze injury, there are fewer regenerating fibres with centrally located nuclei.Reference Woo, Isganaitis and Cerletti 165 In this model, impaired regeneration is further exacerbated if the high fat-fed mice are exposed to undernutrition in utero.Reference Woo, Isganaitis and Cerletti 165

In light of the above, we propose that overnutrition in utero and during early postnatal life, namely, at a time of extensive myoblast proliferation, fusion and differentiation, may increase glucose, insulin and fatty acid levels in developing skeletal muscle tissues, thereby impeding the myogenic programme in favour of adipogenesis, as shown in Fig. 5.Reference Park, Halperin and Tontonoz 166 This may lead to excessive ectopic fat accumulation, compromised skeletal muscle compartment, impaired contractile function and increased insulin resistance. Indeed, several studies using sheep and rodents have shown that offspring born to overnourished mothers develop insulin resistance.Reference Samuelsson, Matthews and Argenton 48 , Reference Samuelsson, Matthews, Jansen, Taylor and Poston 144 , Reference Yan, Huang and Zhao 146 A number of molecular pathways appear to be involved including those that regulate insulin signalling, mitochondrial function, oxidative metabolism and inflammation in skeletal muscle.Reference Latouche, Heywood and Henry 167 The detrimental effects of maternal obesity on skeletal muscle glucose and lipid metabolism are further exacerbated if offspring continue to be fed an obesogenic diet post-weaning.Reference Simar, Chen, Lambert, Mercier and Morris 168

Fig. 5 Maternal obesity may affect stem cell specification in the developing offspring. Skeletal muscle and adipose tissues (white and brown) derive from a common mesenchymal precursor. Specification to each lineage is a competitive process regulated by a number of regulatory factors shown in blue (adapted from Park et al.).Reference Park, Halperin and Tontonoz 166 Growing evidence suggests that maternal diet-induced obesity may promote a mesenchymal cell differentiation-shift down the adipogenic lineage at the expense of myogenesis in the developing offspring. As a result, the skeletal muscle compartment is compromised and contractile and metabolic functions are altered. CD24, cluster of differentiation 24; C/EBPα, CCAAT-enhancer-binding proteins α; MyoD, myogenic differentiation; PGC-1, peroxisome proliferative-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ; PRDM16, PR domain containing 16; RIP140, receptor-interacting protein 140; SRC1/2, Proto-oncogene non-receptor tyrosine kinase.

Early life exercise and other preventive measures

Gatford et al.Reference Gatford, Kaur and Falcao-Tebas 169 have reviewed the benefits of exercise interventions to improve metabolic health in individuals affected by intrauterine growth restriction, however, very few exercise interventions have been carried out in offspring born to obese dams. Early and late onset exercise appear effective at improving metabolic health in these offspring through amelioration of body weight, adiposity, plasma leptin, insulin, triglycerides and glucose intolerance.Reference Caruso, Bahari and Morris 170 , Reference Bahari, Caruso and Morris 171 Other types of interventions have been reviewed by Nathanielsz et al.Reference Nathanielsz, Ford and Long 172 Nevertheless, it is unclear whether and to what extent early life exercise restores skeletal muscle structure and function in individuals born to obese mothers. Therefore, further research is required. Interventions on obese mothers during pregnancy may also prove beneficial. Indeed, Tong et al. Reference Tong, Yan and Zhao 173 have shown that maternal metformin administration during pregnancy prevented the downregulation of β catenin and myogenic markers and the upregulation of adipogenic marker PPARγ in skeletal muscle of neonatal mice born to obese mice. Meftformin is an antidiabetic drug that acts through AMPK signalling, which implies that the negative effects of maternal obesity on skeletal muscle development may be mediated via maternal insulin resistance and/or gestational diabetes.Reference Tong, Yan and Zhao 173

Evidence in humans

Most of the evidence to date that maternal obesity and/or excessive gestational weight gain affects skeletal muscle development and health into adult life comes from animal studies. There is a general lack of human data partly because the contribution of skeletal muscle to general health has been largely overlooked by the scientific community but also because measuring skeletal muscle mass is difficult to achieve outside of the laboratory.Reference Wolfe 54 , Reference McCarthy 55 Furthermore, methods to directly and accurately assess skeletal muscle quality are invasive. These techniques often require whole muscle dissection thus are not applicable to humans for obvious ethical reasons. Several methods are currently being used to assess ‘fat free’ or ‘lean’ mass in neonates and children; these include dual energy X-ray absorbency (DEXA), bioelectrical impendence, magnetic resonance imaging and air-displacement plethysmography.Reference McCarthy, Samani-Radia, Jebb and Prentice 174 – Reference Hull, Dinger, Knehans, Thompson and Fields 176 Based on these methods, the evidence as to whether maternal obesity and/or excessive gestational weight gain impairs lean mass in children is conflicted. For example, Hull et al. Reference Hull, Dinger, Knehans, Thompson and Fields 176 have reported that infants born to obese mothers exhibit increased absolute fat mass but decreased absolute fat-free mass, which is in line with data presented by Ruager-Martin et al. Reference Ruager-Martin, Thomas, Uthaya, Bell and Modi 177 at the Neonatal Society Meeting in the United Kingdom. However, other studies report that absolute lean mass is unchanged in neonates and children born to overweight and obese mothersReference Gale, Javaid and Robinson 175 , Reference Sewell, Huston-Presley, Super and Catalano 178 , Reference Ode, Gray, Ramel, Georgieff and Demerath 179 or in those exposed to excessive gestational weight gain.Reference Crozier, Inskip and Godfrey 32

These discrepancies may be due to measurement errors across the various techniques currently used to assess body composition in humans.Reference van den Ham, Kooman and Christiaans 180 DEXA scanning has been shown to overestimate fat-free mass and underestimate fat mass compared with more direct dissection methods.Reference Provyn, Clarys, Wallace, Scafoglieri and Reilly 181 Discrepancies also exist between the DEXA and bioelectrical impedance methods.Reference Rutten, Spruit and Wouters 182 Nevertheless, McCarthy et al., have recognised the importance of assessing skeletal muscle fitness in childhood and have developed new skeletal muscle mass reference centile curves based on bioelectrical impedance measurements to be used in epidemiological studies.Reference McCarthy 55 , Reference McCarthy, Samani-Radia, Jebb and Prentice 174 These curves, in conjunction with other measures of muscular fitness such as grip strength (Table 1), should help to increase our understanding of the effects of maternal obesity and/or excessive gestational weight gain on skeletal muscle health in humans.

Conclusion

Many lifestyle interventions that aim to reduce obesity rates have limited success. This may be because such interventions are instigated too late in adult life when metabolic organs such as skeletal muscle are fully developed and thus have diminished plasticity and capacity for adaptation. Furthermore, growing evidence suggests that maternal obesity impedes the development of skeletal muscle with negative functional consequences lasting into adult life. Consequently, lifestyle interventions targeted at pregnant women and young children may prove more successful at preventing and/or decreasing obesity rates. Further characterisation of the mechanisms by which maternal nutrition and early life exercise influence skeletal muscle development and function in the offspring is crucial for the development of such evidence-based interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Professor Aaron Russell for his valuable feedback on the manuscript. This work was conducted with C-PAN funding.