Introduction

Sexuality and sexual behaviours among university students differ from the general population of young adults. University students are more free in respect of sexuality due to factors such as freedom, living separate from their family and university social groups (Gençtanırım, Reference Gençtanırım2014). Turkey is a traditional Muslim country, and according to societal norms there is disapproval of university students having sexual partners and premarital sexual activity is perceived as incompatible with social norms and Islamic values. In addition, university students hide their sexual lives because of the social perception of honour in Turkey. In 2011, the World Health Organization reported that unsafe sex was the second highest risk factor in the global burden of all disease (Kebede et al., Reference Kebede, Molla and Gerensea2018). As sexual lives and experiences are hidden in Turkey and other Islamic countries, there are limited data on sexual risk behaviours and unsafe sex in these countries (Golbasi & Kelleci, Reference Golbasi and Kelleci2011; Alsubaie, Reference Alsubaie2019).

In developed countries, honour is defined as honesty, righteousness and morality for men and women, while it is defined differently for men and women in Islamic and traditional societies. Honour for men is to be credible, to protect the family’s reputation and to be moral, while for women it has the meaning of sexual purity. Being a virgin, not flirting, dressing conservatively, not being chirpy, not talking too much and not laughing in social environments are perceived as the behaviours of honourable women in traditional societies (Ruggi, Reference Ruggi1998). Turkish society provides all kinds of comfort to men and expects women to behave in accordance with the manners and customs of society and a life under the control of men. This discrimination manifests itself most clearly at the point of control of the woman’s body (Bora & Üstün, Reference Bora and Üstün2005). Single women in Turkey avoid vaginal sex to protect their virginity, and so have secret sex lives, whereas excessive sexual experiences represent masculinity for men in Turkey. A previous study reported that 80.3% of American adolescents had accessed pornography, 64.7% had experienced vaginal oral sex (66.7%) and a third (33.1%) had experienced anal sex (Astle et al., Reference Astle, Leonhardt and Willoughby2019). Furthermore, according to national US data, there are minimal gender differences in lifetime rates of performing oral sex (Lefkowitz et al., Reference Lefkowitz, Vasilenko, Wesche and Maggs2019). In another study, 93.5% of female German university students had one sex partner and 89.3% of male students had one sex partner (Martynuik et al., Reference Martyniuk, Okolski and Dekker2019).

In traditional societies, especially women and even men do not want to talk about sexual health problems or see a doctor in case of illness and tend to hide their sexual relations. This suggests that sexual health problems may be at a larger scale than predicted. Due to sexual myths shaped by the society, sexual health problems are the invisible face of the iceberg (Ajmal et al., Reference Ajmal, Agha, Zareen and Karim2011; Golbasi & Kelleci, Reference Golbasi and Kelleci2011; Reis et al., Reference Reis, Ramiro, Matos and Diniz2013). While the increasing prevalence of unprotected and early sexual intercourse in developed countries causes sexual health problems, in developing countries the prevalence of hidden sex lives is unknown and risky sexual behaviours are associated with many sexual health problems.

This study was conducted to determine the sexual experiences and gender differences in sexual behaviour in Turkish university students.

Methods

Participants

The research population of this cross-sectional, descriptive study, conducted between 1st February and 12th November 2017, consisted of students at a state university located in the Mediterranean region of Turkey. The study university has ten faculties and five high schools with 43,000 registered students (18,700 males and 24,300 females). The sample size was determined as 491 students to represent the population with an acceptable error value of ±5% and a confidence interval of 95%. Students were selected with a systematic sampling method. A total of 32 students were selected from each faculty and high school. Data collection forms were distributed in sealed envelopes and collected back in the same way. The response rate was 84.3%. After exclusion of 77 students due to incomplete data, evaluation was made of the responses of 414 university students.

Data collection tools

Two data collection forms were developed by the researchers. A ‘Socio-demographic form’ was used to collect data for the independent variables age, gender, marital status, place of residence, family structure, number of siblings, parental education status, income and religion. A ‘Sexuality and sexual behaviour form’ included twelve questions about partner status in the past and currently, sexual intercourse experiences, oral sex experiences, anal sex experiences and sexual life and sexual behaviour variables.

Data analysis

Data were analysed statistically using SPSS version 22.0 software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 22.0). The socio-demographic data and sexual experiences were compared by gender to determine differences in sexual behavioural according to gender. Data were evaluated using the Chi-squared test (significance taken at p < 0.05). The relationships between gender, sexual experiences and sexual health behaviours were evaluated using multinomial regression analysis.

Results

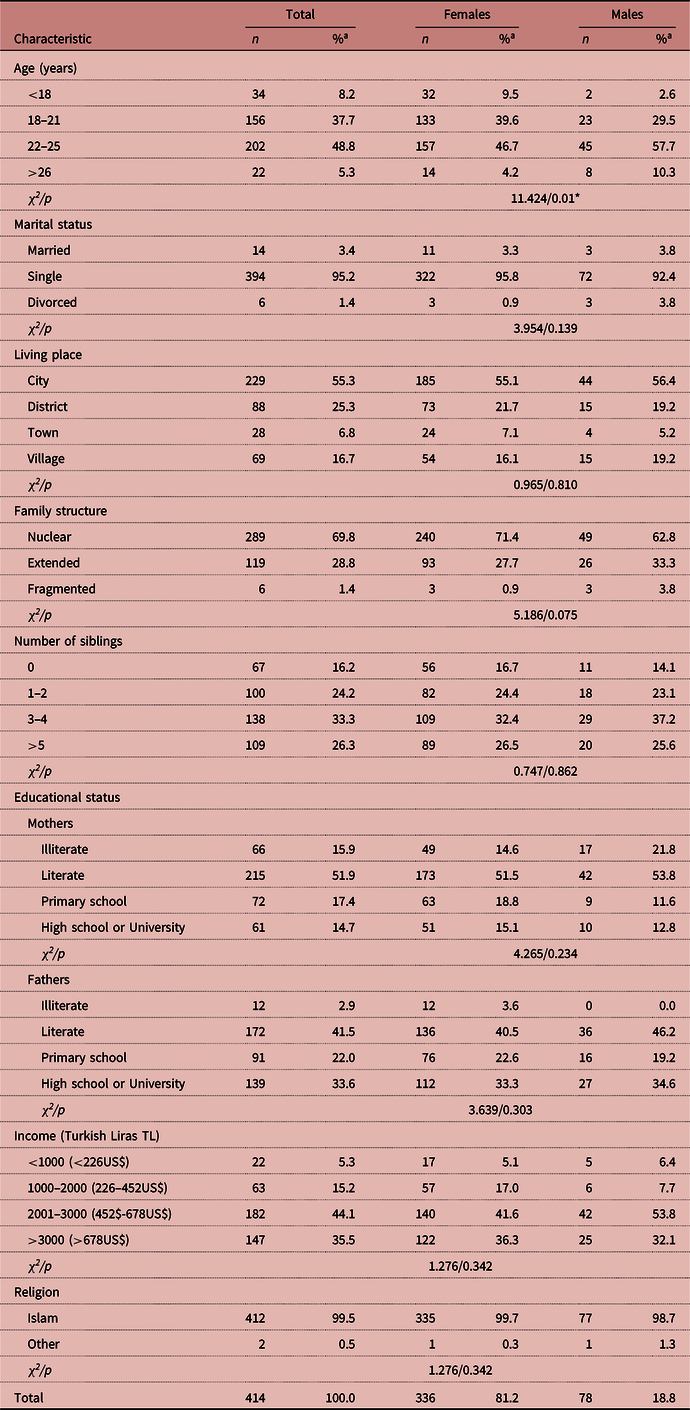

The socio-demographic characteristics of the students in the study are shown in Table 1. The study sample comprised 81.2% females and 18.8% males with a mean age of 20.79 ± 1.9 years. Of the total sample, 95.2% were single, 55.3% were living in the city centre, 69.8% had nuclear families and their mean number of siblings was 3.75 ± 2.2. Parental level of education was of primary school level for 51.9% of mothers and 41.5% of fathers. Income level was reported as moderate by 44.1% of the students; 99.5% were Muslim with only two students stating having another religion. Females constituted 77.7% of the students in the 22–25 year age group, 81.7% of the married students and 80.8% of those living in the city centre.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants by gender

a Column percentages.

* p < 0.05.

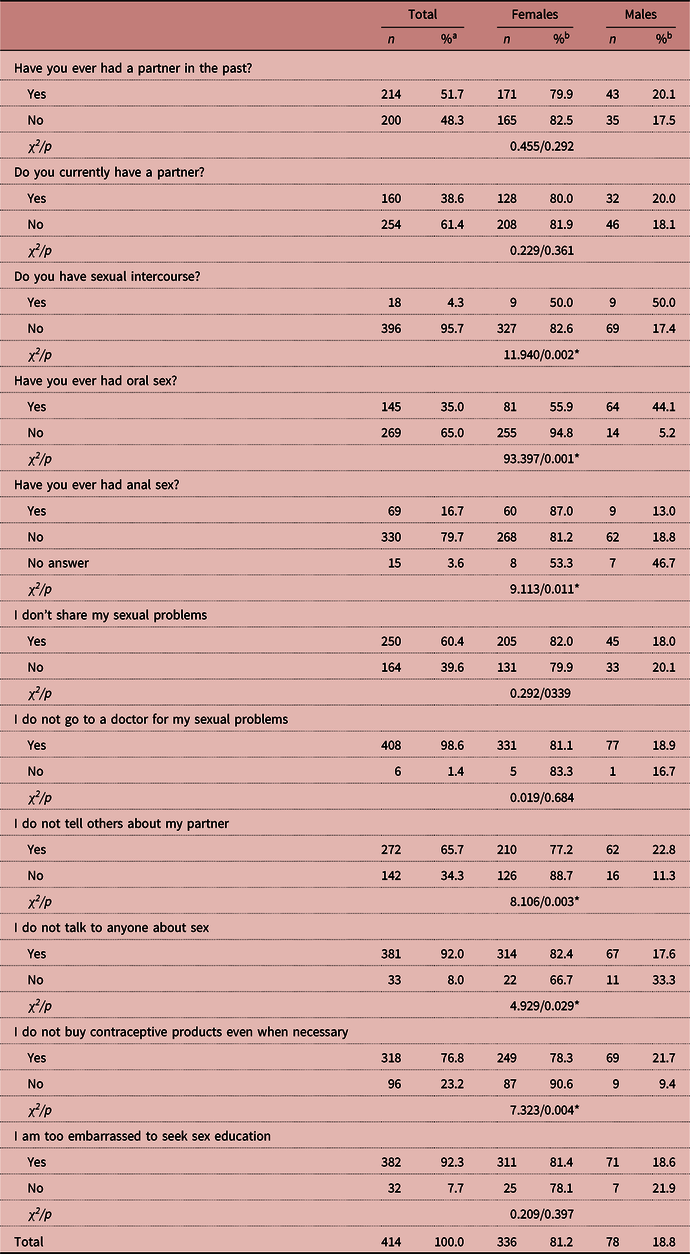

A comparison of participants’ sexuality and sexual behaviour variables by gender is shown in Table 2. A previous sexual partner was reported by 51.7% of the students; 38.6% currently had a partner, 4.3% had had sexual intercourse, 60.4% did not share their sexual problems, 98.6% did not see a doctor because of sexual problems, 65.7% did not talk to anybody about their sexual partners, 92% did not talk to anybody about sexuality, 76.8% said they would not buy contraceptive products even when necessary and 92.3% were too embarrassed to seek sex education. Females comprised 79.9% of the students who had a partner in the past, and 50.0% of the students who had had sexual intercourse, and 44.1% of the students with oral sex experience were male. Most of the female students (82%) did not share their sexual problems and did not talk to anybody about their partners (77.2%); 81.1% did not consult a doctor because of sexual problems, 82.4% did not talk about sex, 78.3% would not buy contraceptive products even when necessary and 81.4% were too embarrassed to seek sex education.

Table 2. Sexual life and sexual health variables of students by gender

aColumn percentages; brow percentages.

* p < 0.05.

A multiple logistic regression model was established with these variables (Table 3). This revealed a statistically significant relationship between gender and the variables for having sexual intercourse, oral sex, anal sex, talking about their partner and sex education. Female students were 13.98 times more likely to have experienced oral sex, 3.71 times more likely to have experienced anal sex, 4.73 times more likely to have had sexual intercourse, 1.3 times more likely to be too embarrassed to seek sex education, and 2.12 times more likely not to talk to others about her partner than male students.

Table 3. Multiple regression analysis showing the association between gender and sexual behaviours (N = 414) (reference category: Female)

SE: Standard Error; df: degree of freedom; OR: odds ratio; Cl: confidence interval.

Discussion

University students have more freedom to have a sex life than other young adults in the general population, and are therefore at greater risk sexually. Sexual attitudes and behaviours are generally affected by the socio-cultural environment and interactions with friends at universities. In most traditional and Muslim societies, sexuality is defined by the virginity of a woman, and a man is defined as a guard who protects honour. This traditional point of view continues despite the increased levels of development of countries (Cok et al., Reference Cok, Gray and Ersever2001; Aras et al., Reference Aras, Orcin, Özhan and Semıh2007). The conception of honour not only entails social constraints and responsibilities, but also has a negative effect on sexual health and life.

In traditional societies, it is expected that men and women will have sexual behaviour differences due to the social limitations about sexuality. Women are expected to uphold ‘the family’s religious and cultural integrity’ (Dwyer, Reference Dwyer2000). Women’s behaviour, in particular, has a significant impact on a family’s honour (Ayyub, Reference Ayyub2000; Shankar et al., Reference Shankar, Das and Atwal2013; Gill & Brah, Reference Gill and Brah2014; Cowburn et al., Reference Cowburn, Gill and Harrison2015). In a study in Turkey about traditional attitudes, 66.9% of the study students said that ‘sexual intercourse before marriage is wrong’, 63.6% said ‘extramarital relations are destroying our moral and cultural values’ and 52.1% said ‘self-induced abortion is morally wrong’ (Tokuç et al., Reference Tokuç, Berberoğlu, Saraçoğlu and Çelikkalp2011). In other study, it was noticeable that the factors affecting sexual attitudes and behaviours differed for the two sexes, and in addition to one’s own desire and values, socio-cultural variables were seen to be of considerable importance for both males and females (Aras et al., Reference Aras, Orcin, Özhan and Semıh2007). However, the majority of those affected by sexual problems among university students in Turkey are female (Aras et al., Reference Aras, Orcin, Özhan and Semıh2007; Tokuç et al., Reference Tokuç, Berberoğlu, Saraçoğlu and Çelikkalp2011). In another study conducted in Iran, of the students who reported having sexual partners, meeting in an empty house was the most common type of relationship among girls (30.4%) compared with their male counterparts where the rate was 13.9% (Ghorashi, Reference Ghorashi2019). In the current study, it was seen that female students want to hide their sexuality but it was determined that they have had more sexual experiences (such as oral and anal sex).

In this study, only eighteen students reported that they had had sexual intercourse, while 35% (n = 145) reported that they had experienced oral sex, more than half of whom were female. Of the 69 students who had experienced anal sex, 60 were female. Sexuality is focused on female virginity in traditional societies, so any sexual intercourse that does not affect virginity is more common. The expectation for female students to be virgins represents how traditional gender norms play a role in Turkey. This power dynamic may also result in female students having less knowledge about sexual health and to engage in risky sexual behaviours. It is not surprising that those living in a traditional society do not share sexual problems, do not go to the doctor with sexual problems, do not tell anyone about their partners, do not buy any contraceptive products even when necessary and do not talk about sex. However, hiding sexual problems in these societies has a negative effect on sexual health (Akın, Reference Akın2006). In a previous study conducted on students, it was reported that a large majority of students did not talk about sexuality, and unwanted pregnancies and consequently sexually transmitted diseases increased due to misunderstood sexual myths among young people (Süt et al., Reference Süt, Aşcı and Gökdemir2015).

The rate of modern contraceptive use among young unmarried people is low due to fear and social norms (Hoang et al., Reference Hoang, Nguyen and Duong2018). However, countries driven by gender inequalities that constrain individual behaviour in sexual interactions often have high rates of unwanted pregnancy and sexual transmitted diseases (Nalukwago et al., Reference Nalukwago, Crutzen, van den Borne, Bukuluki, Bufumbo, Burke and Alaii2019). In traditional societies, there are two major risks for women. The first is hiding sexual life due to social limitations, and the second risk is that her partners have more relationships and unprotected sex (Leslie, Reference Leslie2019). In another study in female university students, it was reported that 47% had had unprotected sexual intercourse (Polo et al., Reference Polo, Cassas, Senior and Hamdan2019). In addition, the rate of termination of pregnancy in Turkey has been reported to be 29% among university female students (Aras et al., Reference Aras, Orcin, Özhan and Semıh2007).

In the current study, 76.8% of students stated ‘I do not buy contraceptive products even when necessary’. While there is an understanding that partners should be hidden from others in Turkey, premarital sexual intercourse is common in most parts of the world. Contraceptive products allow many women to complete their education and pursue a career, thus shrinking the wage gap between the sexes in developing countries (Van Zyl et al., Reference Van Zyl, Brisley, Halberg, Matthysen, Toerien and Joubert2019), but women do not use contraceptive products and do not buy them in premarital relationships.

It has been reported that 68% of young people under 20 in the US and 72% in France have had sexual intercourse (Evcili & Golbasi, Reference Evcili and Golbasi2017). Süt et al. (Reference Süt, Aşcı and Gökdemir2015) reported that 21.3% of nursing department students and Evcili et al. (Reference Evcili, Cesur, Altun, Güçtaş and Sümer2013) reported that 5.6% of Turkish university students had had a sexual experience. In the current study, similarly, only 4.3% of the students reported having had sexual intercourse, but 35% had experienced oral sex and 16.7% had experienced anal sex. The reason for the higher rates of oral sex and anal sex is the ‘protection of virginity’. A university student in Turkey was forced to hide her pregnancy, killed her baby immediately after the birth and was found guilty of breaching honour values. Today, there are still high rates of ‘honour’ crimes where many women are murdered by their mother, father or brother, have to conceal their sex life and have sexual health problems because they cannot receive medical help (Doğan, Reference Doğan2018). Sociological studies have demonstrated that sexual behaviours of young people are limited by the norms established within a social context and that shame and guilt are more commonly reported when sexual activity contradicts individual, family and social normative expectations (Shoveller et al., Reference Shoveller, Johnson, Langille and Mitchell2004; Moreau et al., Reference Moreau, Költő, Young, Maillochon and Godeau2019). According to the American College Health Association, in 2013 approximately half of college students had engaged in oral sex, 42–68% in vaginal sex and 5% in anal sex in the past month. In the USA, men were more likely to receive oral sex and use condoms than were women. Young adults often perceive oral sex as a positive part of their sexuality, playing an important role in physical pleasure and relationship intimacy (Lefkowitz et al., Reference Lefkowitz, Vasilenko, Wesche and Maggs2019). In sub-Saharan Africa, the prevalence of reporting oral sex among university students ranged from 3.0 to 47.2%, and the prevalence of reported anal sex ranged from 0.3 to 46.5% among university students (Morhason-Bello et al., Reference Morhason-Bello, Kabakama, Baisley, Francis and Watson-Jones2019).

In traditional societies, where sexuality is associated with marriage, sexuality within the notion of honour is met with denial, prohibition or silence, and the need for reproductive health services for single young women is overlooked (Tokuç et al., Reference Tokuç, Berberoğlu, Saraçoğlu and Çelikkalp2011). Pushing sexuality and sexual health into the background can lead to unplanned and unwanted pregnancies, high-risk sexual behaviours, sexually transmitted diseases, sexual intercourse at a young age and an unhealthy sexual life with multiple partners (Özcan et al., Reference Özcan, Güleç, Demir, Tamam and Soydan2017).

This study had some limitations that warrant caution and suggest future directions. First, the sample was limited to students at one state university in a traditional city in Turkey. The contexts and opportunities underlying sexual relationships, and thus the rates of sexual behaviours, most likely differ for students in more urban areas. Second, the cross-sectional method used in this study does not explain causation, and although respondents were asked about specific behaviours, the survey included an explicit definition of sexual behaviours and some participants did not fully complete the questionnaire (77 students were excluded from the study due to incomplete data).

In conclusion, in line with these results, there is a need for equity studies on gender and sexuality and community activists should be mobilized in traditional countries. It can be recommended that there should be provision of sexual health services in the medical units of universities to meet the sexual health education needs of students and the placement of sexuality and sexual health courses in the university curriculum.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial entity or not-for-profit organization.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Approval

Approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Kahramanmaras Sutcu Imam University (Ref. No.2016/20-04).