It is impossible to study the history of humanitarian organisations and, especially, of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) without thinking about the Second World War and particularly the ICRC's work intended to help people affected by the Third Reich's policy of genocide. The ICRC tends to be presented as a founding institution of modern humanitarianism and as a model that showcases the ideal values put into practice by humanitarian organisations (neutrality, impartiality, etc.). But did it fail in its universal mission? That question lies at the heart of a major, often passionate debate. It has become an important milestone in the historical background to modern-day humanitarian endeavour. Three events are of special significance and the source of much of the criticism directed at the ICRC's attitude to the genocide: the ICRC's decision, in October 1942, not to launch a public appeal,Footnote 1 the visit in late June 1944 by ICRC delegate Maurice Rossel to Theresienstadt, and his meeting at Auschwitz with, by his account, the camp commander in September 1944.Footnote 2

These three events have played a decisive part in shaping the debate on the ICRC's past. Thus, while the ICRC ‘principle of silent neutrality’ has been denounced in many quarters,Footnote 3 Bernard Kouchner, co-founder of Médecins sans Frontières, has repeatedly referred to the role that past played in his own work:

We didn't know what was happening in the concentration camps, so we did nothing. The International Red Cross, which was aware of the existence and purpose of the Nazi camps, chose to remain silent. Its explanations for that concealment are unprecedented in their shamefulness. Those who shared that extremely grave secret made no attempt to act.Footnote 4

Faulted for not issuing a public condemnation, the ICRC is also said to have played into the hands of Nazi propagandists, who used Rossel's visit to Theresienstadt and his subsequent report to present a distorted image of reality in the camps.

Public discourse on the ICRC's failure to help people affected by Nazi racial policy has been part of a broader movement marked by the emergence of a public memory of genocide.Footnote 5 In that context, the negative judgement of the ICRC was commensurate with first criticisms that began being levelled at it as soon as the war ended.Footnote 6 In discussing the ICRC's past, certain humanitarian practitioners and thinkers, in particular those affiliated with the ‘without borders’ movement, often cited that past to justify new forms of humanitarian action. In response to the ICRC's wartime silence, they called for media scrutiny of humanitarian work so as to forge new ties between humanitarian organisations and civil society.Footnote 7 Their stance heralded the advent, in the late 1960s, more than 100 years after Solferino, of a ‘new humanitarian century’, to use Philippe Ryfman's words, of a mode of action in which the victims’ rights took priority and which was predicated on individual commitment by humanitarian workers in the field.Footnote 8 In this movement, the ‘right of intervention’ proclaimed first by the philosopher Jean-François Revel and later by Kouchner appears as the final step in a process of reaction to the ICRC's failure at AuschwitzFootnote 9 and was used to weave a founding tale whose justification lay in its break with an approach seen as outmoded, and embodied by the ICRC.Footnote 10

The ICRC was deeply shaken by this debate. The criticism of its approach to the victims of Nazi racial violence led it to embark, in the 1980s, on a process of analysis and repentance and to open its archives to a well-known historian.Footnote 11 In 1988, Jean-Claude Favez produced a major study of the ICRC's activities to help racial and political deportees. The study gives an extremely detailed and nuanced picture of the ICRC's work, but that study was not carried out in a vacuum that excluded the lively ethics debate underway. Its conclusions repeat the ethics-based arguments put forth and reserve a special place for the issue of the ICRC's refusal to publicly condemn Nazi violence. Favez concluded that the ICRC ‘really should have spoken out’.Footnote 12

Favez's contribution and the high degree to which discussion of the ICRC's silence was carried over into the media and society as a whole helped renew the principles of humanitarian action. It did not, however, facilitate the exploration by historians of new avenues of research on the ICRC's wartime activities.Footnote 13 This discussion centred on the importance for humanitarian organisations to speak out and more generally on the ethical and moral position of humanitarian workers in the face of mass violence. To an extent, however, it pushed out certain essential questions regarding the ICRC's activities during this period. In short, the impact on society's views and popular memory of the ICRC's ‘moral failure’ somewhat prevented historians from making their voices heard and exploring new avenues of research.

How can we (re)think the ICRC's history vis-à-vis the victims of Nazi genocide? To our way of thinking, the solution is to float the ICRC off the reef on which it has been stuck and on which its past is written up essentially by the humanitarian agents themselves and modelled in response to a debate being conducted by humanitarian organisations. Undertaking new research projects means turning away from remembrance and means repositioning the history of humanitarian organisations against the broader backdrop of States and entire societies mobilized for war. This implies opening the history of humanitarian action to include the social history of the period, comprising in particular the study of field operations. It implies leaving behind what are often sterile questions regarding the applicability of humanitarian law or the obligation to bear witness and getting down to the nitty-gritty of field work, logistics (visas, transportation, import of goods, control of distributions), the actual activity that constitutes humanitarian response. It means moving beyond simply the question of involvement by humanitarian organisations to include an analysis of their activities to help those affected, in particular by assessing the effectiveness of their endeavours. This is a crucial aspect of assessing the past, yet it is often overlooked in studies on the history of humanitarian work, in which the scope and effectiveness of field operations are relegated to the background.

Such an undertaking far exceeds the scope of a journal article, but it should be stated that it would help direct the spotlight onto new aspects and would serve to rekindle discussion of the question. It would poses a number of complex methodological problems and require precise reconstruction and work on the sources. But would offer a useful lens through which to study the ICRC's work to help political and racial detainees in Nazi concentration camps during the final phase of the war in Europe. The purpose of this article is therefore not to consider the ethical obligations of humanitarian organisations by retelling this key episode or to take part in the discussion about the ICRC's silence on the genocide. Rather, the purpose is to take a different approach in order to provide useful fuel for that debate.

As the title suggests, our aim is to analyse the various initiatives taken by the ICRC to help concentration-camp detainees. This article therefore covers only part of the Nazi policy to exterminate Jews and includes other categories of deportees (political, homosexual, etc.). Before going any further, it is important to point out that the ICRC conducted no activities on the Eastern Front in response to the acts of mass violence committed against Jewish populations in the wake of the German offensive against the Soviet Union. In addition, as we shall see, the ICRC had no specific policy regarding the Jews locked up in concentration camps or regarding the death camps, even though it was prompted by information it was receiving on deportation and by the initiatives of Jewish groups to make the first representations regarding concentration-camp detainees. The concentration-camp system was a complex and multi-faceted reality. Regardless of the grounds for their detention, the ICRC's work in the camps concerned the Schutzhäftlinge, ‘administrative detainees’, a category invented by the detaining power in order to set those detainees apart from the other categories (civilian internees and prisoners of war).Footnote 14

Washington, Geneva, Berlin

Before we turn to the ICRC's activities for concentration-camp detainees, it is important to briefly recall the orientation of the ICRC's activities during this period. The organisation had a complex identity. It was at once a private association governed by a body of exclusively Swiss members and an organisation with an international identity at the head of the Red Cross Movement. At the beginning of the war, it had numerous ties with the Swiss government. The fact that the ICRC was firmly anchored in Switzerland caused it to be perceived in Bern as an instrument of Swiss foreign policy, a view at complete odds with the Committee's own concern to affirm its central position on the international humanitarian scene.Footnote 15

During the war, the ICRC faced a twofold challenge. It underwent sweeping structural transformation as its activities expanded. A small office before the war, the organisation grew in size starting in the summer of 1940 to become – by the end of 1944, and as it had during the First World War – a large-scale humanitarian enterprise. As the Second War drew to a close, it had a staff of some 3,400 professionals and volunteers.Footnote 16 This rapid change did not occur without growing pains. The ICRC's identity – that of a product of the philanthropic spirit of Geneva's upper classes – was ruffled by the need for specialists and new techniques to cope with problems of mass transportation, communications, record-keeping, etc. That its leaders were somewhat out of sync with the new reality comes for exemple through in a book published in 1943 by Max Huber. A religiously inspired essay, Le Bon Samaritain. Considérations sur l'Evangile et le travail de Croix-Rouge,Footnote 17 discusses the bible parable in light of the organisation's Christian roots and of Dunant's own commitment, without ever referring to the ICRC's activities or the challenges posed by the brutality of the Second World War. It was strangely uncoupled from the catastrophe that was at that very moment befalling entire populations and from the scope of the task confronting the ICRC.

Far from withdrawing into itself, however, the International Committee continued to grow during the war and adapted to the demands and needs of the belligerents and the National Red Cross Societies. While it did not follow a specific road map or a prepared procedure, the ICRC made use of its status as a neutral intermediary, thus providing much appreciated support for the National Societies, which devoted most of their efforts to relief work for prisoners of war. The American Red Cross, for example, transported over 200,000 tonnes of goods worth an estimated 168 million US dollars during the war for Allied prisoners of war.Footnote 18

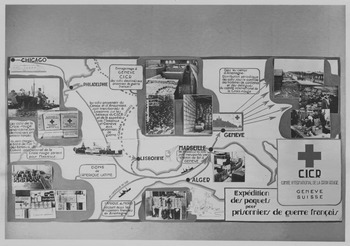

During the war, one of the ICRC's main tasks was to have the Central Agency centralize and exchange information on prisoners of war.Footnote 19 It therefore found itself distributing to prisoners of war food parcels funded by the National Societies. In a way, the ICRC served as an international ‘postman’ for prisoners of war. Its services allowed information to be exchanged on places of detention and helped transport letters and parcels. Given that most of the soldiers detained were in German hands, the ICRC focused a large part of its activities on Allied prisoners. Although it wanted to assert its independence and its leadership in the humanitarian field, the organisation was nevertheless but one link, albeit an essential one, in a complex operational chain that generally started with the production of food parcels on American Red Cross premises in Philadelphia. The Red Cross parcels were then loaded onto ships financed by Washington or London but flying the ICRC flag.Footnote 20 The parcels were unloaded in Lisbon and transported to warehouses in Switzerland before being stacked in sealed rail cars headed for the Third Reich's prisoner-of-war camps. The ICRC's involvement in this complex trans-Atlantic transportation and distribution system, funded for the most part by the Allies, is a key to understanding the organisation's dealings and the types of activity it carried out for the concentration-camp detainees.

The system set up for sending prisoner-of-war parcels. © ICRC photo library (DR)/Bouverat, V.

Before continuing, it is useful to recall that, contrary to common belief, the ICRC's activities were not strictly limited by international humanitarian law. Thanks to its statutory right of initiative,Footnote 21 the ICRC participated right from the start of the war in operations to help civilians, in particular in the framework of the Joint Relief Commission it set up with the League of Red Cross Societies.Footnote 22 In 1940, President Huber said the following to representatives of the German press gathered in Geneva:

This lack of rights is perhaps the secret of our organisation's strength. For the Red Cross sees its work as being wherever people are in distress, wherever it can relieve suffering. The Committee is not bound by any pre-established mandate. If it can base itself on any principles set out in international law or in treaties between the belligerents that might be of use. Nor does it confine itself to the actual law in force. Rather, it endeavours to act in accordance with the idea that originally inspired the Red Cross – to take ever more effective action to ease the suffering of people affected by war.Footnote 23

First representations in behalf of concentration camp detainees

Discussion of concentration-camp detainees started to gather pace at the ICRC as the year 1942 progressed. This was mostly prompted by information received from the ICRC delegation in Berlin on the deportation of Jews from the German capital eastwards and the first deportations from French territory.Footnote 24 The Committee delivered a note on the subject to the German government on 24 September in which it suggested that, on a reciprocal basis, foreign detainees should be treated the same as civilian internees in terms of correspondence and reception of food parcels.Footnote 25 Though the note proved fruitless, the ICRC nevertheless managed to gradually develop a very modest relief programme after it received German authorization, in January 1943, for foreign Schutzhäftlinge whose names and place of detention were known to it to receive parcels.Footnote 26 That very limited concession, given how difficult it was for the ICRC to obtain such information, was in fact the result of Himmler's decision of late October 1942 to allow next-of-kin to send food parcels to foreign and German detainees not subject to the strictest regime. This opening enabled the Swedish Red Cross, for example, to send the first parcels to Scandinavian detainees.Footnote 27 The concession can be explained, we believe, by the complexity of the concentration-camp system. In that context, the parcels became a useful means of establishing a hierarchy of privileges between the various categories of detainees. With the cooperation of the Scandinavian solidarity networks, the ICRC launched a very modest operation, sending a few hundred parcels intended mostly for detainees of Norwegian nationality.

This operation, which was based on practices developed for prisoners of war, probably allowed a compromise within the Committee between those members in favour of action for deportees and those who opposed initiatives that might threaten both relations with Germany and the work for prisoners of war, which had priority. However, in 1944, two things happened that explain the gradual development of an operation to help concentration-camp detainees. In January of that year, President Roosevelt set up the War Refugee Board, whose purpose was to develop a programme to save Jews and other minorities being persecuted by the Nazis.Footnote 28 The War Refugee Board embodied the new attention that was being paid in Washington to this issue and held the promise of fresh financial and diplomatic means for the ICRC. In early February, the War Refugee Board and the State Department entrusted an important operation to the ICRC and allocated USD 100,000 to it from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, thereby placing at the ICRC's disposal a sum of 429,000 Swiss francs. On the strength of those funds, the Committee drew up a distribution scheme for Jewish populations deported to Transnistria and Bessarabia (100,000 francs sent to Romania), dispatched aid to Theresienstadt (119,000 francs worth of standard Hungarian parcels) and Krakow (Lactissa vitamin-enriched milk worth 100,000 francs), and earmarked 70,000 francs for the pharmacy. It also obtained agreement to use part of the amount to send parcels on a trial basis so as to open new channels for relief.Footnote 29 The remaining 40,000 Swiss francs were set aside for the shipment of parcels to concentration camps in the Netherlands and Upper Silesia, i.e. enough to ship about 2,700 standard parcels.Footnote 30

This development explains why the ICRC wanted to obtain Germany's permission to visit the camps and ghettos: the relief supplies came for the most part from the United States and Canada, and their importation into Germany was subject to authorization by the blockade authorities, which controlled all transports to central Europe. The Allies did not want the food supplies to end up in German hands, which is why, since the start of the war, the dispatch of Red Cross parcels for prisoners of war had been linked to a system of guarantees overseen by the ICRC. The receipts that the prisoners of war signed for the parcels and the delegates’ visits themselves provided a degree of verification. As in the case of prisoners of war, the blockade authorities tied permission for importation of parcels destined for deportees to the guarantees provided by the ICRC delegates’ visits to concentration camps.Footnote 31

Rossel's visit to Theresienstadt in June 1944 must therefore be seen as part of a broader operation for sending parcels to concentration-camp detainees.Footnote 32 During this period, the ICRC held talks with the British and American governments about the blockade.Footnote 33 Did the ICRC deliberately play along with Nazi propaganda so as to obtain authorization for its delegates to visit other camps? In the summer of 1944, Roland Marti, ICRC delegate, again visited Buchenwald and Dachau as the operation gradually picked up, and the sending of parcels progressively increased.Footnote 34 The operation was made possible thanks to the American government's decision to authorize the ICRC to use goods salvaged from the sunken cargo ship SS Cristina, which had been loaded with standard American Red Cross parcels for prisoners of war. Questions as to the quality of the salvaged food explain why the parcels were not sent directly to the prisoners of war.Footnote 35 The food was nevertheless used in late August 1944 to assemble 25,600 food parcels for concentration-camp detainees, a reminder that the operation for deportees continued to take second place to the one for prisoners of war. The status of this potentially tainted cargo may also have made it easier to obtain a concession from the blockade authorities.

The ICRC was probably allowing itself to be duped in its visits to the camps, since they were usually limited to a meeting with the camp officers and did not entail a genuine assessment of the conditions of detention and relief distributions. The ICRC was unable to exercise any control over the distributions of parcels. Despite those difficulties, its initiatives for the detainees were supported by Washington and soon by the new French government. The ICRC's involvement in the relief system for deportees was an additional reason for the blockade authorities to grant further permission for goods to be shipped to deportees.

For the French authorities, relief for deportees became a priority after D-Day because numerous Resistance members and other important individuals were being held in the camps.Footnote 36 It was this new policy that prompted a delegation from the Belgian and French Red Cross Societies to visit Geneva in September.Footnote 37 During a meeting with ICRC representatives, the French Red Cross representative stressed that the deportees should be given priority. This determination to act was bolstered by rumours of reprisals against military and civilian prisoners in Germany for acts of violence against collaborators in France. Jean-Etienne Schwarzenberg, head of the ICRC's Special Assistance Division, which was responsible for aid to concentration-camp detainees, referred in September 1944 to the situation of deportees and ‘Jews’ in Germany as being ‘more precarious than ever’, as they were now ‘especially dangerous’ witnesses.Footnote 38 Schwarzenberg therefore asked the ICRC to ‘adapt’ its approach and ‘review its policy’Footnote 39 on the delegates’ activities in view of the ‘present circumstances’.Footnote 40 In the autumn, the ICRC apparently was sometimes able to send three shipments per month, chiefly for Norwegian, Dutch, French, Belgian and Polish deportees.Footnote 41 Lastly, a few visits were made by ICRC delegates to Dachau, Buchenwald, Natzweiler, Ravensbrück and Sachsenhausen camps, where the parcels were said to be received by ‘representatives’ (‘hommes de confiance’)Footnote 42 of the various nationalities of detainees.Footnote 43 During this period, it is significant that the War Refugee Board representative in Switzerland, Roswell McClelland, regularly asked the ICRC for news of its visits to the camps.Footnote 44

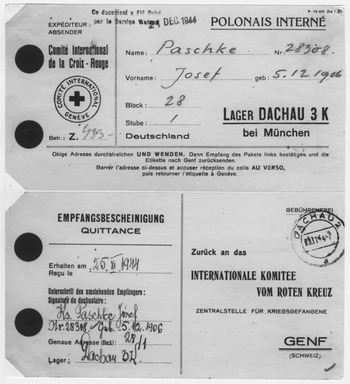

World War II. Label and receipt for a parcel sent to Dachau concentration camp. © ICRC.

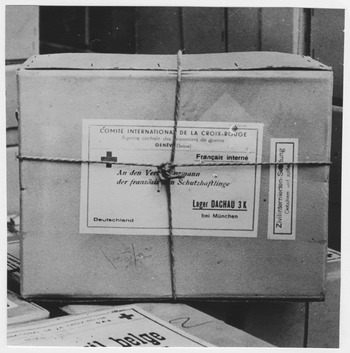

World War II. ICRC parcel for French deportees at Dachau. © ICRC photo library (DR).

Parcels, trucks, delegates

Huber's letter of 2 October 1944 asking the German authorities to expand the rights of ‘administrative’ detainees was evidence that the ICRC was stepping up its activities for concentration-camp detainees in response to American and French pressure. In late January 1945, several days after allowing ICRC delegates to visit camps for German internees, Henri Frenay, the French Minister of Prisoners, Deportees and Refugees, proposed that German civilians be exchanged for French deportees in Germany, with priority being given to women and children.Footnote 45 In addition, he asked the ICRC to take prisoners of war and deportees under its protection.Footnote 46 Those French initiatives were followed by an appeal by the National Red Cross Societies of the governments in exile for ‘a high-level representation to the German authorities to release the civilian, political and racial detainees’.Footnote 47 Several days before this appeal, A. R. Rigg, deputy director of the ICRC Relief Division, stated that ‘this is an opportunity for the Swiss Confederation to carry out an operation that could have favourable political repercussions, and it would be regrettable to miss it’.Footnote 48

As we know, the collapse of the Third Reich unleashed a disaster that caused grave humanitarian concern. As the Allied troops advanced, the camps were evacuated in forced marches from one camp to another.Footnote 49 Hitler wanted to eliminate all trace of the camps. On the other hand, some Nazi officials, Himmler among them, hinted that certain detainees might be exchanged for political or economic gain.Footnote 50 It was in this context that rescue operations were undertaken, notably by former Swiss president Jean-Marie Musy,Footnote 51 who negotiated the evacuation from Theresienstadt of a first contingent of 1,200 Jewish detainees. They arrived in Switzerland in early February 1945. Several weeks later, the vice-president of the Swedish Red Cross, Count Folke Bernadotte, met with Himmler and received permission to transport 4,700 Scandinavian detainees to Neuengamme, where they would await repatriation. At the end of April he used ICRC trucks, among other vehicles (Swedish trucks), to evacuate 2,900 women detainees from Ravensbrück (Operation White Buses).Footnote 52

The ICRC found itself in an unusual position. Its contacts with the camp commanders since the summer of 1944 and its status as a neutral institution gave it greater operational potential. For the first time since the start of the war, the ICRC was receiving large quantities of relief supplies intended specifically for concentration-camp detainees. By the end of 1944, 300,000 parcels financed by the War Refugee Board were stored in the port of Göteborg.Footnote 53 In addition, with the German rail system in ruins, the Allies made available to the ICRC a large fleet of trucks in early March 1945. This gave it a means of taking action in the camps. The Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force had made available 468 trucks to ship parcels to prisoners of war, but the ICRC was allowed to use the trucks on their return journeys to transport former concentration-camp detainees to Switzerland.Footnote 54 Lastly, the camp commanders no longer opposed the shipment of parcels for detainees from Western Allied countries. The German Minister for Foreign Affairs, Joachim von Ribbentrop, replied positively on 1 February 1945 to Huber's request of 2 October 1944, giving French and Belgian deportees the right to exchange correspondence and receive parcels. That concession is a practical illustration of the gradual opening of the camps to Red Cross parcels.Footnote 55

In March 1945, for the first time since the start of the war, the ICRC was in a position to conduct a genuine relief operation for concentration-camp detainees. The final weeks of the war are therefore a decisive and significant time when it comes to defining the ICRC's attitude towards the victims of deportations. How much did it do to the rescue concentration-camp deportees during that period? What was the operation's result in humanitarian terms? The operation had three, often complementary, components: the shipment of relief parcels, the evacuation of detainees and the presence in the camps of delegates who acted as intermediaries during the camps’ surrender.

The ICRC's principal contribution was the development of the parcel operation in early 1945. During that period, the ICRC shipped to the camps a significant portion of the 751,000 parcels it sent to deportees during the war.Footnote 56 The organisation's fresh resources gave it a new scope for action, even if the quantity seems small in comparison with the needs of an underfed population estimated in early 1945 at 700,000.Footnote 57 Moreover, those parcels did not represent a great deal compared with the aid being shipped to prisoners of war. It is difficult to compare the two relief operations, which were carried out in far different contexts and circumstances, but it is worth noting that the soldiers from Western Allied countries received, through the ICRC, over 24 million parcels during the war.Footnote 58

Several ICRC delegates were busy distributing parcels to detainees in the final days of the war, a period during which the Germans emptied a number of camps by force and moved the detainees in harrowing conditions.Footnote 59 A delegate carried out the first distribution, of two truckloads of food parcels on 2 April in Theresienstadt.Footnote 60 From 22 April, delegates were present in the field, for the first time, as part of an emergency operation in which they came into direct contact with the victims of the concentration-camp system. Thus, parcels were distributed by ICRC delegate Willy Pfister along the road taken by detainees on a forced march from the evacuated Sachsenhausen camp north of Berlin, as well in the Below Forest, near Wittstock, where thousands of exhausted detainees had spent several days without food. That it was possible to launch this operation, which the ICRC had not planned, was thanks to the 5,000 War Refugee Board parcels and 3,000 standard American Red Cross parcels stocked in the ICRC warehouse in Wagenitz, about 70 km west of Berlin,Footnote 61 and also to two trucks available at Nauen that were used to make initial distributions on the afternoon of 21 April to detainees on the forced march.Footnote 62 It is very likely that, on 27 April, a convoy of 15 ICRC trucks from Lübeck managed to distribute a large shipment of parcels to evacuees.Footnote 63 According to the report from the ICRC Transport Service, the convoy made two distributions of food in Below Forest (on 27 and 30 April) of 56,000 kg each.Footnote 64 Those distributions were made pursuant to a request from SS-Obersturmbannführer Rudolf Höss.Footnote 65 This suggests that the Germans were using the relief supplies to facilitate the detainees’ evacuation but probably also to make sure food was available for the officers and guards.

World War II. Death march from Oranienburg-Sachsenhausen to the Wittstock concentration camps. A crate of Red Cross parcels is opened by German guards. © ICRC/Pfister, Willy.

During the operation for the Sachsenhausen deportees, another delegate witnessed a forced march by detainees from Dachau. The ICRC was unprepared to cope with the chaos spreading across the country. As it had in northern Germany, it improvised a humanitarian operation in the Munich area. The difficulties encountered by one delegate, Jean Briquet, in conducting a relief operation in Dachau testify to the ICRC's isolation and the limited means available to deal with the emergency unfolding in the concentration camps. From 18 April to 8 May, Briquet made repeated journeys from Dachau, north of Munich, to Uffing (lying to south-west of the city, where the ICRC sub-delegation was located for the western zone in Germany), and to Moosburg, to the north-east of Munich, where the main food depot for prisoners of war and the collection point for the ICRC's trucks was located. During the first eight days of his mission, Briquet attempted several times – in vain – to obtain authorization to establish an ICRC presence at Dachau and faced numerous problems because it was so difficult to communicate with the delegation and owing to the shortage of available trucks.

On 27 April, Briquet was informed that a column of French deportees evacuated by force from Buchenwald had spent the night at the prisoner-of-war camp in Moosburg. He sent trucks to the camp and distributed a small number of parcels (807), later providing additional relief supplies to 182 sick people from the column. Returning to Dachau at the end of the afternoon, he was informed by the commander's adjutant that the Germans intended to surrender the camp to the Allies by means of ICRC mediation. According to the plan presented to Briquet, around 16,000 ‘Allied’ detainees would stay in the camp under his supervision, while the German, Russian, Italian, Austrian and Balkan internees would be evacuated by the Germans. This plan was reminiscent of the policy applied at Ravensbrück, where the detainees from Allied countries were not subject to the same treatment and conditions as the others. When he was informed of the plan, Briquet decided to go to Uffing. Along the way he met a column of women, most of them Jewish, who had been evacuated from Dachau and were being marched to Mittelwald. Several kilometres later, outside Pasing, he encountered another column, about 10 kilometres long, of prisoners being marched in the rain. He observed piles of bodies ‘a metre high’ on the sides of the road and heard numerous gunshots. After stopping at the delegation, he left with trucks of supplies for people in the column. He found himself blocked by retreating columns of Germans and returned to Uffing on the evening of 28 April having found no trace of the detainees. The next day, in Bernried, Briquet managed to provide supplies to a trainload of Jewish deportees (2,621 parcels). The operation was paralysed during the following days, however, following the arrival of the American armed forces. One week later, on 5 May, Briquet carried out another distribution for 220 sick Jewish deportees from Dachau, and later to 2,000 deportees housed in a former SS school in Feldafing.Footnote 66 The next day he took 210 French political detainees from Moosburg to the Swiss border.Footnote 67

As we have seen, the ICRC was able to distribute parcels because the Allies had provided it with a fleet of trucks. Using the trucks, the ICRC was able to evacuate several groups of deportees to Switzerland. It is hard to say exactly how many deportees were evacuated by the ICRC. According to the figures given in an internal ICRC report from June 1945, it transported 6,098 people, including 2,685 French and 1,193 DutchFootnote 68 (the figures are fairly close to those we found in the Archives). By way of comparison, the Swedish Red Cross evacuated approximately 17,000 people from Germany at the end of the war, according to Sune Persson.Footnote 69

The ICRC carried out two main evacuation operations. The first was subsequent to the meeting of 12 March 1945 between Carl Burckhardt and SS-Obergruppenführer Ernst Kaltenbrunner – the head of the Reich Security Main Office (‘Reichssicherheitshauptamt’) and the man in charge of all the concentration camps – in a country inn near the German-Swiss border on the road from Feldkirch to Bludenz.Footnote 70 The following days saw a series of negotiations between Adolf Windecker and Fritz Berber, Joachim von Ribbentrop's representative to the ICRC. The main subject of discussion was in all likelihood the exchange of French internees in Germany for German internees held in France. Other subjects discussed were visits by delegates to the camps, the grouping of detainees by nationality and shipments of relief supplies.Footnote 71 The discussions soon came to a standstill, which prompted the ICRC to dispatch a special representative to Berlin, Hans E. Meyer. He had been assistant to Karl Gebhardt, the SS chief surgeon from 1943 to August 1944 who had become vice-president of the German Red Cross in the meantime. His good contacts in BerlinFootnote 72 enabled him to meet with Himmler and make the operation possible.Footnote 73 His intervention was no doubt decisive in finally allowing the transportation from Ravensbrück to Switzerland of 299 French and one PolishFootnote 74 female detainees in exchange for the release in France of 454 German civilians.Footnote 75

World War II. Kreuzlingen. 300 women released from Ravensbrück concentration camp arrive in Switzerland on board ICRC trucks. © ICRC photo library (DR).

After the roads between northern and southern Germany were closed, making it impossible to organise another convoy for Ravensbrück, the core of the ICRC operation shifted to the south of the country. It organised three deportee convoys from Mauthausen (columns 35, 36 and 37),Footnote 76 which transported a total of 780 French, Belgian and Dutch deportees on 23 and 24 April. Several days later, two other convoys evacuated successively 183 and 349 deportees from Mauthausen and 200 Swiss from Landsberg.Footnote 77 Besides the above-mentioned transports (1,512 people), the ICRC took part in the repatriation of 2,250 French civilians from northern Italy in late AprilFootnote 78 and in the transfer aboard two ICRC-chartered boats of 806 former detainees from the port of Lübeck to Sweden in early May.Footnote 79 Once the fighting had ended, the ICRC facilitated the transport of 2,600 people released from the camps between 24 May and 12 June.

One of the most noteworthy ICRC activities was its delegates’ presence inside the camps during the Reich's final days, when they tried to act as mediators between the German guards and the Allied forces. It is hard to track down the precise origin of this operation, but it would seem that, at his meeting with Burckhardt, Kaltenbrunner authorized the delegates to enter the camps on condition that they remained there until the arrival of the Allied troops.Footnote 80 Despite this oral pledge, however, the delegates’ attempts to enter the camps remained in vain until the final days of the war. It was only after a meeting in Innsbruck on 24 April between Kaltenbrunner and Burckhardt's secretary, Hans Bachmann, that the first delegates were apparently able to enter the camps.Footnote 81

In Theresienstadt, where he arrived on 2 May, Paul Dunant oversaw the transition between the departing German guards and the arriving Czech Red Cross representatives on 10 May.Footnote 82 Maintaining order in the camp was of considerable importance for health and security reasons. For one thing, steps had to be taken to ensure that the detainees were not eliminated before liberation and to prevent reprisals against the guards after liberation.

In the other camps, the delegates arrived after the camp had been evacuated and liberated (e.g. Landsberg,Footnote 83 Bergen-Belsen and Buchenwald), or the ICRC faced the commandant's refusal to hand over the camp until it had been evacuated (Sachsenhausen, Ravensbrück). Victor Maurer, who arrived in Dachau on 28 April, after Briquet, was allowed to distribute parcels inside the camp and to spend the night in the barracks of the SS guards. During the night, he watched as most of the guards slipped out of the camp. The following morning, he apparently approached SS-Obersturmbannführer Wickert, who had been sent during the night to take charge of the camp and, so it seemed, to hand it over to the American forces. As part of his mission to avoid reprisals and to prevent the spread of epidemics in the areas around the concentration camps, Maurer persuaded Wickert that the guards should remain in the watchtowers and ensure the detainees did not leave the camp. Towards the end of the afternoon, accompanied by the German officer, he received a group of jeeps from the American 42nd Infantry Division at the gates to the camp.Footnote 84 By acting as an intermediary, Maurer may have prevented fighting from breaking out inside the camp, but his report makes no reference either to the armed uprising by escaped detainees put down by the SS the night before in the town of DachauFootnote 85 or to the fighting that broke out that afternoon between the 45th American Infantry Division and the SS regiment in the barracks adjacent to the camp, which culminated in the summary execution of German prisoners.Footnote 86

World War II. Dachau, concentration camp. An American officer, ICRC delegate Maurer, SS-Oberleutnant Wickert and a German officer in front of a convoy loaded with the corpses of deportees. © ICRC/Algoet, Raphaël.

The episode that is most emblematic of this operation was the mission by another delegate, Louis Haefliger, to Mauthausen.Footnote 87 Haefliger is considered a hero in some quarters for having persuaded camp commander Franz Ziereis not to obey his orders to blow up the airplane factory next to Gusen I and II camps with the detainees inside. It is hard to know for certain the scope of Haefliger's initiatives. For his part, SS-Obersturmbannführer Kurt Becher, who was close to Himmler, said after the war that he intervened to prevent the camp's destruction.Footnote 88 Haefliger nevertheless took part in the camp surrender plan and placed himself at the service of the Allied troops, negotiating the replacement of the SS guards by US soldiers. As he wrote in his report, the liberation was a chaotic process, with the camp stores being looted and the former detainees carrying out acts of vengeance in the following days. In the midst of this extremely vague picture, it is difficult to define the exact role played by Haefliger, who resigned after the war in controversial circumstances.Footnote 89

Assessment, problems, issues

In the early 1970s, a journalist wrote a hagiographic account of the decisive role played by certain delegates in the operations organised by the ICRC.Footnote 90 In response to criticism of the ICRC's attitude to the genocide, the journalist highlighted the delegates’ courage and commitment, and portrayed them as incarnating the ICRC's universal values. Previously, the ICRC had omitted from its official account the individual role of its delegates in Germany during the final phase of the war. By contrast, the account written by Dr Marcel Junod after the war became a reference work for the organisation.Footnote 91 This text, which heralded the emergence of the delegate as a figure in his own right, contains only a few lines on the ICRC's initiatives to help concentration-camp prisoners.Footnote 92 That omission reflects the depth of the organisation's crisis of memory. Beyond the individual merit and courage of certain delegates in the field, what assessment can be made of the ICRC's operations for concentration-camp detainees? Its activities during the war appear to have been determined essentially by the demands of the Allied powers, in that they were closely tied to the requests made by the Allied governments, which financed its operations and provided most of the relief supplies at its disposal. In the last phase of war, the rescue of deported populations emerged as a diplomatic and political issue for Swiss foreign policy, the aim of which was to maintain Swiss neutrality as an institution in the new post-war international order, to deflect criticism of its relations with Nazi Germany during the war and to preserve the ICRC's reputation at a time when the humanitarian playing field was being reconfigured by the establishment of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration.

As the ICRC adapted to the new situation, it shifted away from its main role as an agency that collected information on and supervised the distribution of parcels and correspondence to prisoners of war, and began launching operations to help concentration-camp detainees. Its involvement nevertheless reflected the difficulties its main leaders were encountering in redirecting the ICRC's work in this new context. Huber's temporary departure at the end of December 1944 and the appointment of his successor, Burckhardt, as Switzerland's chief representative in France in February 1945Footnote 93 may explain some of the difficulties the ICRC had in defining its policy and moving into new areas of action. Its work appears to have been guided mostly by caution and concern to do nothing that might conflict with the interests of the Swiss authorities and the main warring parties. The way in which the ICRC negotiated with SS leaders during the final weeks of the war is a perfect example of its cautious approach. Burckhardt's restraint is reflected in his refusal to travel personally to Berlin, unlike Count Bernadotte, or to send a high-level ICRC representative. The ICRC president took care to avoid involving the organisation in any secret negotiations. At the same time, the Swiss authorities, who feared they would be overwhelmed if masses of refugees and former prisoners arrived at the country's borders, were greatly circumspect regarding the rescue operations.Footnote 94 In fact, Burckhardt's meeting with Kaltenbrunner appears on the whole to be a relatively insignificant episode amid the various negotiations concerning concentration-camp detainees. The ICRC operation to evacuate deportees pales in comparison with that carried out by Bernadotte, even though Operation White Buses concerned mainly Scandinavians, who benefited from more favourable treatment and conditions.

The ICRC rescue operation for deportees is noteworthy, in our view, for its improvised nature and because the means mobilized were so inadequate given the enormous needs of the concentration-camp detainees. The ICRC was overwhelmed by the scope of the task at hand and, as we have seen, had recourse to practices and means originating essentially in its work for prisoners of war. Its belated involvement explains why the delegates most involved in the concentration-camp operation were recruited mere days before their departure for Germany. With the means of transport guaranteed, the ICRC conducted a rapid campaign to recruit delegates at the end of March, which resulted in little more than a dozen being hired. Burckhardt was looking for men who were relatively mature (over 27), spoke fluent German and were familiar with perhaps one more language, and had a ‘firm and upright character’. In his view, Swiss army officers with ‘a true spirit of sacrifice’ were the best prepared for the operation's demands. The ICRC provided eight days of training and a monthly salary (1,000 Swiss francs) that was twice that of an ordinary delegate.Footnote 95

In the midst of a country that lay in ruins and was crisscrossed by columns of refugees, Allied troops, and Wehrmacht soldiers in retreat, the ICRC's delegates were isolated and unable to communicate with Geneva. Often forced to improvise, their room for manoeuvre – already slim – was further narrowed by their limited contact with Allied troops. The difficulties encountered by the convoy of trucks headed by one delegate, Jean-Louis Barth, illustrate the predicaments the ICRC faced during the final days of the war. The convoy left Konstanz, on the Swiss border, on 13 April at 8.45 a.m. and took three whole days to cover the 450 km to its destination, the Flossenbürg camp, where it arrived on 15 April at around 6 p.m.Footnote 96 En route the convoy was repeatedly delayed by flat tires, the numerous detours it had to make around the trees lying in the middle of the road and the damage caused by bombing. It was also stopped at roadblocks and by air–raid alerts.

The next day, on 16 April, the convoy set off for the camp itself but was stopped by a battle during which a train carrying deportees was machine-gunned by SS guards, resulting in around 30 deaths. At that point Barth ordered the trucks back to the town of Floss. Uneasy, he nevertheless decided to try once more to reach the gates of the camp. This time, the convoy was met by drunken guards. According to the delegate's account, there reigned a ‘horrid atmosphere’, which prompted the trucks to return yet again to Floss. After this second failure, Barth finally persuaded the town's SS officers to allow him to provide supplies to a column of 400 Russian prisoners of war he had encountered on the road. In exchange for a few bars of chocolate for the German guards, Barth was allowed to open some 30 parcels and give some of their contents to the prisoners. On 18 April, he finally decided to unload the remaining 1,200 parcels at Stalag XIII (a prisoner of war camp) and then to flee for fear that the Allies would arrive and requisition the trucks. During the return trip, somewhere in the vicinity of Munich, the convoy came across numerous refugees on the road. Barth continued on his way, remarking, ‘The world seems gripped by madness In the panic and chaos … people are half-crazy, clinging to the trucks’.Footnote 97 Finally, after an eight-day journey, the convoy arrived back in Konstanz on 21 April without having been able to enter Flossenbürg camp.

This episode reflects the minor part assigned the ICRC in the Allied relief and reconstruction programme, under which, after an initial period of work under the responsibility of the occupation forces, the task in the occupied territories was to be handed over to the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. From that point on, private agencies played no more than a secondary role under the Administration's supervision. In addition, the ICRC was not recognized by the Soviet Union. This placed it in an awkward position on the front and resulted, among other things, in the four remaining staff members at the Berlin delegation (Otto Lehner, Albert de Cocatrix, the secretary Ursula Rauch, and the driver André Frütschy) being interned for four months in a Soviet camp in Krasnogorsk.Footnote 98

Isolated, underprepared or totally unprepared, the delegates seemed insignificant in number given the major human catastrophe that accompanied the collapse of the Third Reich. From the ICRC's viewpoint, however, this was, as pointed out above, the main field operation conducted for concentration-camp detainees. For the first time, delegates had at their disposal a large quantity of relief supplies intended for deportees and financed by the War Refugee Board among others. And they had the transport to carry out unprecedented missions. However, the means at their disposal often turned out to be inadequate compared with the detainees’ needs. Despite the commitment of certain delegates, these activities revealed the limits of and problems faced by an operation mounted in haste as a ‘side show’ to the massive work in aid of prisoners of war. It was in fact impossible to supervise the distribution of parcels in the camps, and as a result the parcels were repeatedly diverted and stolen by camp officials. In early May 1945, ICRC representatives visiting the camp at La Plaine, in the canton of Geneva, were told by former detainees from Mauthausen interned there that the only parcels they had seen in Mauthausen had arrived on 28 April. The content had been consumed by the guards, who allegedly forced the detainees to sign receipts but did not give them the parcels.Footnote 99 In addition, former detainees from Sachsenhausen, moved at the end of the war to Mauthausen, stated that 25 per cent of the parcels arriving at Sachsenhausen ended up in the hands of the guards or the representatives’ of detainees (‘hommes de confiance’).Footnote 100 These statements suggest that there existed in the camps a kind of sinister black market fed by the arrival of relief parcels. Before reaching the detainees, the parcels were passed from the camp staff to the kapos and the block leaders,Footnote 101 each in turn removing the most coveted items or using the contents as a means of exacting concessions and obedience.Footnote 102 According to Eugen Kogon, the shipments of parcels constituted a highly profitable system for the camp guards. For example, the SS officer in charge of the Buchenwald customs office reportedly diverted 5,000 to 6,000 Red Cross parcels in August 1944, and in March 1945 seven rail cars (loaded with 21,000 to 23,000 Red Cross parcels) apparently disappeared.Footnote 103

It must also be emphasized that the contents of the parcels, intended to provide additional nourishment for prisoners of war, were not suitable for the starving inmates of the camps.Footnote 104 Rich in proteins, sugar and vitamins, the food was hard to digest to the point that it killed some of the weakest detainees. More generally, the ICRC does not seem to have given real thought to the detainees’ actual health needs. The organisation took one improvised initiative after another, often in a clumsy manner and without giving special consideration to the specific needs of the people involved. The operations to repatriate detainees from Ravensbrück and Mauthausen were an example of this, revealing as they did what little attention the Swiss authorities paid to the extraordinary circumstances of the deportees struggling to survive the concentration camps. In the report he filed on his return from Mauthausen, ICRC delegate Rubli complained bitterly of the conditions in which the evacuees were received in Switzerland, which he considered ‘scandalous’.Footnote 105

World War II. Kreuzlingen. Detainees from Ravensbrück concentration camp are housed in a gym after their evacuation by the ICRC. © ICRC photo library (DR).

Rubli was in charge of convoy 36, which was held up at the border (23 Avril) by the Swiss authorities from 5 p.m. to 10 a.m. the following morning. The former detainees were forced to spend the night on the road, without blankets, hot drinks or food. Rubli also spoke of the lack of sanitary facilities and shelter and the transfer of the evacuees into third-class rail cars.Footnote 106 More generally and except for the work of a delegate by the name of Hort, who took it upon himself to provide first aid for 500 detainees in Landsberg,Footnote 107 the ICRC made only a modest contribution to the various medical missions undertaken to save released detainees. For example, Jean Rodhain, chaplain general for prisoners of war and deportees in France, organised three medical missions to Bergen-Belsen, Dachau, Mauthausen and Buchenwald.Footnote 108 The British Red Cross mobilized five teams in Bergen-Belsen, backed by British Quakers.Footnote 109 The ICRC, for its part, dispatched a team made up of six doctors and twelve nurses, which arrived in Bergen-Belsen on 2 May to assist the British teams.Footnote 110 Several months later, the ICRC's lack of medical expertise prompted it to launch a monthly internal bulletin entitled Documentation médicale à l'usage des délégués, whose purpose was explained in the first issue: to provide the information needed by delegates, who ‘for many years had been kept unaware of the medical progress made by the Allies’.Footnote 111

Our aim in this brief summary of the problems raised by the ICRC's work for concentration camp detainees has been to shift the focus away from the usual questions of principle and broaden the scope by recounting some actual history of humanitarian operations. We have sought to show that, during the final phase of the war, the ICRC seized the opportunity afforded by the first German concessions regarding concentration camp internees to conduct operations made possible thanks to support from the American and French governments. Rather than reflecting an existing commitment to help the racial and political victims of the Third Reich, the ICRC's work appears to have resulted from three factors: its participation in the Allied humanitarian effort to help prisoners of war; the Swiss government's concern to ensure Swiss neutrality in the emerging new order; and the ICRC's own determination to maintain its leadership in the humanitarian field. While it is true that the delegates working in Germany during the final days of the European war courageously took risks, the ICRC did not manage to carry out a genuine humanitarian operation. The organisation had been designed to gather information about and deliver aid to prisoners of war, and its response, hastily thrown together, is indicative of the difficulty it had redefining itself during the final phase of the war and of the minor role it played in the occupation programmes imposed by the Allied forces.Footnote 112

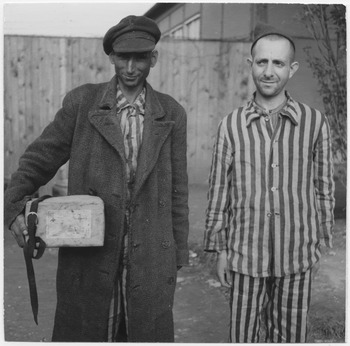

World War II. Detainees with a Red Cross parcel at Dachau concentration camp shortly after its liberation. © ICRC photo library (DR).