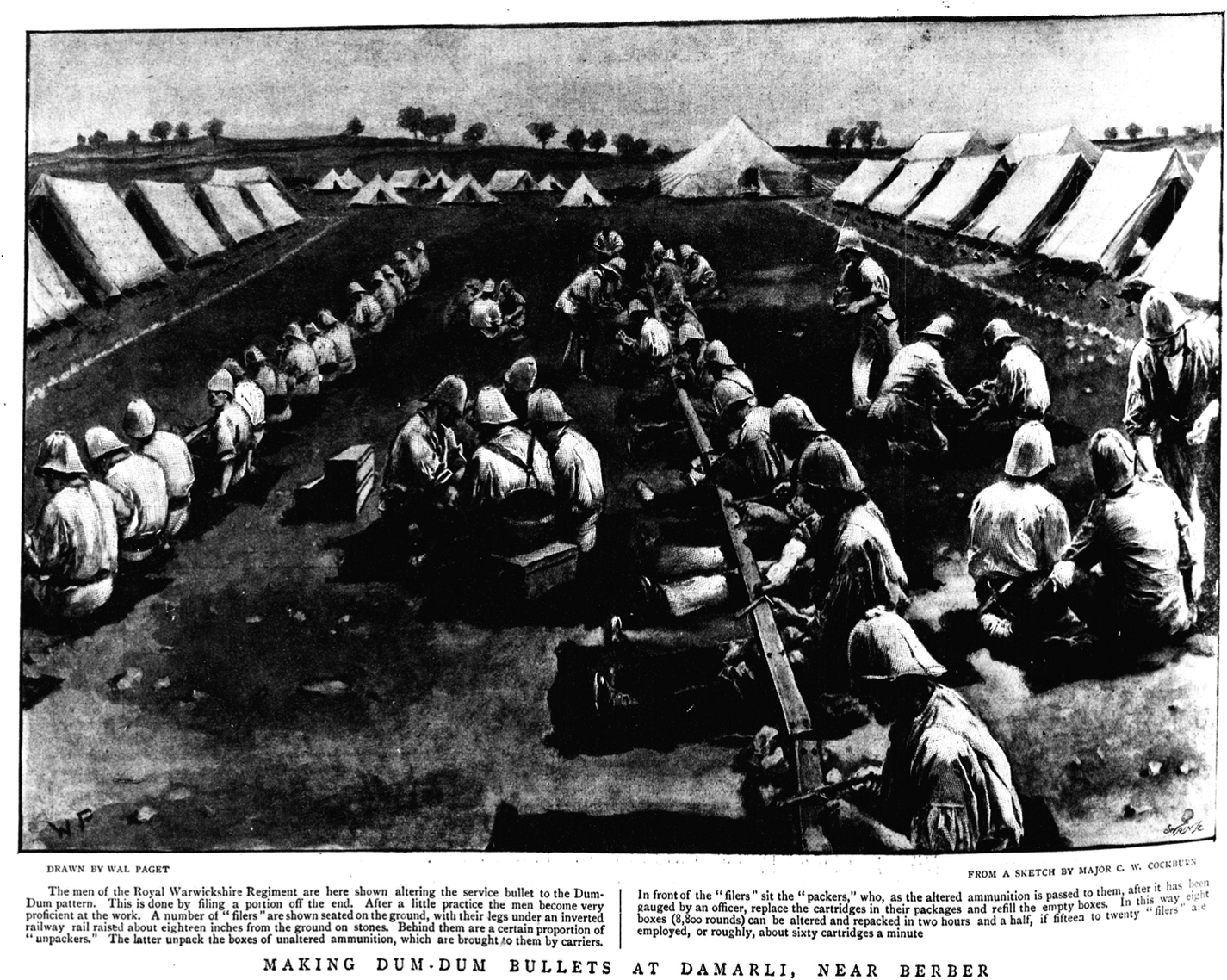

In 1899, the delegates gathered at the Hague Peace Conference adopted a peculiarly specific declaration. Its signatories agreed to “abstain from the use of bullets which expand or flatten easily in the human body, such as bullets with a hard envelope which does not entirely cover the core or is pierced with incisions”.Footnote 1 The British military manufactured these modified Mark II bullets at its Dum Dum Arsenal, situated on the outskirts of Calcutta (Kolkata), starting in 1895, and utilized them on India's Northwest Frontier as well as in the Sudan in 1898. At the massacre at Omdurman that year, British soldiers shooting filed-down Mark II bullets (see Figure 1) wreaked havoc on their Mahdist enemies.Footnote 2 As their battle reports noted, these “dum-dum bullets” inflicted the most horrendous wounds, the “terrible severity” of which caused tens of thousands of casualties. Even two days after the event, severely wounded men were left to die untended at the scene of battle.Footnote 3 It was not the neglect of the wounded at Omdurman that caused controversy in the Anglo-European media in 1898, however, but rather the graphic nature (see Figure 2) of the dum-dum bullets’ wounding power.Footnote 4 British medical officers related how these wounds were “large, jagged and torn”, with “great damage done to the surrounding parts”, while “long bones were found to be extensively shattered, and joints completely disorganised”. As Britain's surgeon general explained it at the time, “there is no doubt about the stopping power of this bullet”.Footnote 5 In expanding and fragmenting on impact, the modified Mark II served to kill.

Figure 1. In the weeks leading up to the Battle of Omdurman in 1898, British soldiers filed down hundreds of thousands of Mark II bullets, turning them into expanding dum-dums. Source: Walter Paget, “Making Dum-Dum Bullets at Damarli, Near Berber”, Graphic (London), 23 April 1898, p. 500.

Figure 2. An artistic rendering of a leg wound caused by an expanding bullet (dumdumgeschoss). Source: M. Kirschner and W. Carl, “Über Dum-Dum-Verletzungen”, Ergebnisse der Chirurgie und Orthopadie, Vol. 12, 1920, p. 653.

This article offers a history of the controversy that developed around the use of expanding ammunitions in the 1890s, leading to their prohibition in 1899. At one level, the article reinforces the existing historiography which shows that the Hague Declaration was a product of a media spectacle that revolved around Britain's deployment of dum-dum bullets. As such, the diplomats at The Hague needed a disarmament “success” story to feed to the global media, and banning dum-dum bullets seemed an easy fit.Footnote 6 Yet, at another level, the article shows that Britain's employment of expanding bullets in the 1890s was not a particularly new or innovative military development. Rather, their adoption signalled a return to earlier rifle patterns – particularly the expanding and hollow-nosed rifle bullets of the 1860s and 1870s. This brought with it a return to the controversies and debates that existed around the use of such ammunition since the signing of the St Petersburg Declaration of 1868. In this sense, the prohibition on expanding bullets in 1899 is anomalous: why regulate this technology now and not earlier? The answer lies, we argue, in the fact that the invention of smokeless gunpowder (in the late 1880s) allowed for the development of full-metal-jacket ammunition like the Mark II, a bullet which did not expand on contact with human skin. These smaller, sleeker, non-expansive bullets were thought to create “cleaner”, less deadly and, thus, more “humanitarian” wounds. Since an alternative to soft-lead ammunition now existed, it opened up the possibility of regulating expansive bullets and their wounds in the laws of war. It also reignited debates about the degrees of violence a soldier could legitimately unleash from their small arms.

Importantly, in all these discussions, the perceived needs of imperial warfare and colonial policing repeatedly reared their ugly heads, for if a “humanitarian” bullet did not kill a “fanatic” or “savage” enemy easily, then for many Anglo-European commentators at the time, expanding bullets and their ghastly wounds were a military necessity. Across the nineteenth century, a key part of the disputes around the use of small arms ammunition focused on distinguishing among potential enemies. Who should be protected from excessive harm? Who falls outside the terms of the laws of war and might be legitimately targeted by such violence?Footnote 7 In this way, the dum-dum controversy of the 1890s reveals as much about the racial and imperial prerogatives embedded in the laws of war as it does about the limits of military and State violence which Anglo-Europeans were willing to accept as legitimate in different scenarios.Footnote 8 Above all, the dum-dum spectacle exposes the complex moral interplay at work in the Anglo-European public sphere at the turn of the twentieth century, in which contemporaries questioned the “just” limits of a military force's “right to kill” and its humanitarian obligation to regulate its violence in proscribed ways.

At The Hague in 1899, the proponents of prohibiting expanding bullets emphatically argued that such projectiles were superfluous to military need, as they did more than merely “stop” an enemy from attacking.Footnote 9 Recent improvements in bullet propulsion and design, including the introduction of smokeless gunpowder (cordite) and steel-encased projectiles, enabled the adoption of what they considered to be less deadly rifle ammunitions which, they argued, did the work of “stopping” an enemy just as well. From this perspective, the point of war was to wound an enemy soldier sufficiently to place them hors de combat (outside of combat) but not so much as to cause their death. The general ambition was that with excellent medical care, a wounded soldier might make a full recovery and live a full life. According to this interpretation, dum-dum bullets created excessive wounds that either ended a victim's life or guaranteed their long-term suffering. Those who advocated for banning expanding bullets mobilized evidence from medical reports alongside experiments undertaken on animals and human cadavers to argue that the terms of the St Petersburg Declaration of 1868 should apply.Footnote 10 That treaty ruled that armaments which “uselessly aggravate the sufferings of disabled men or render their death inevitable” should be excised from war.Footnote 11

The British delegation at The Hague challenged these claims head-on and argued that the dum-dum bullet was an essential weapon in colonial contexts, and that the bullet's wounds were not wantonly cruel. Sir John Ardagh explained that the Mark II bullet, a steel-clad cordite-propelled projectile which did not expand on impact, was introduced in 1892 but subsequently proved incapable of “stopping” a “rush of fanatics” or a cavalry charge in actual battle.Footnote 12 In other words, the Mark II did not wound horses or determined foes enough. Therefore, the dum-dum adaptation was a necessary military innovation to suppress anti-imperial resistance. At any rate, as Ardagh also made clear, the wounds caused by dum-dum bullets were no worse than those created by the expanding ammunition of older military rifles like the Snider-Enfield (adopted in 1866) or Martini-Henry (adopted in 1871), both of which remained in use in many parts of the world. Ardagh further underlined that soldiers must have confidence in their weapons and that, in imperial settings especially, British troops did not trust that the Mark II disabled their enemies effectively. He also implied that the call to proscribe dum-dums was little more than an opportunistic witch hunt orchestrated by Britain's rivals. After all, the injunction only targeted this particular British military invention, and not those of any other country.Footnote 13 No other government was contemplating the adoption of expanding ammunition for the new cordite-powered military rifles.Footnote 14

In the end, only the US and Portuguese delegations accepted the legitimacy of Ardagh's arguments: the former refused to ratify the declaration, while the latter abstained from voting on it.Footnote 15 Even though the Hague Declaration of 1899 was not binding on Britain, the political implications of the dum-dum prohibition weighed so heavily on the British government that it recalled all expanding bullets from South Africa on the eve of the second Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902) and, subsequently, refused to employ them in China during the Boxer Rebellion (1900) as well. In light of this British compliance, some commentators reflected that the dum-dum declaration was The Hague's crowning achievement. From this perspective, as Major W. D. Thomson of the 1st Bengal Lancers explained in 1901, the prohibition was a “good example of the progressive spirit of humanity”.Footnote 16

The long-term consequences of the 1899 Hague Declaration were certainly significant. Even today, expanding ammunitions are invoked as harbingers of excessive military harm.Footnote 17 We tend to describe all types of expanding ammunition, regardless of their technical differences, as “dum-dums”, and inflect our language around their use with moralistic and derisory overtones. As Joanna Bourke so evocatively contends, “[t]he onomatopoeic nature of the word dum-dum still evokes energy, military prowess and prestige (for its proponents), and racism, cowardice, and cruelty (for opponents)”.Footnote 18 Just as importantly, the 1899 dum-dum declaration is considered foundational to international humanitarian law, affirming the principle that the weapons used in lawful wars must avert unnecessary suffering and prevent superfluous injury.Footnote 19 In so many ways, dum-dum bullets continue to infuse how we evaluate the “just” limits of military violence in modern international life.

Yet many histories of The Hague's dum-dum prohibition, much like those of the St Petersburg Declaration of 1868, are mired in inaccuracy, and particularly so when they skirt around the development, production and specificities of the technology in question.Footnote 20 Standard accounts of the 1899 Hague Declaration tend to describe the expanding effect of dum-dum bullets as an innovation of the moment, invented by Captain Neville Bertie-Clay and the British Ordnance Department in India in response to the noted deficiencies in the Mark II bullet's ability to wound Britain's imperial enemies sufficiently.Footnote 21 In reality, the British Ordnance Department experimented with a range of expanding ammunitions from 1895 on. It adopted not only Bertie-Clay's bullet in India in 1895 but also a new cup-nosed expanding bullet, the Mark IV (see Figure 3), as its standard-issue service ammunition in 1897. Similarly, many histories of the St Petersburg Declaration either suggest that exploding bullets were a Russian discovery made in 1863 or that they were an untried military experiment whose potential frightened the authorities.Footnote 22 In reality, all European armies experimented with exploding and fulminating projectiles in the 1860s.Footnote 23 One historian even goes so far as to claim that before dum-dums were invented, European armies only ever used bullets with “sufficient stopping power to disable or render their victim hors de combat”, which is absurd given the noted “man-stopping” powers of soft-lead ammunition.Footnote 24 All of these assertions oversimplify the contexts in which rifle bullets were developed, employed and debated from the 1850s.

Figure 3. Scientific American's rendering of Britain's Mark IV .303-inch calibre service bullet, which the journal misidentified as a dum-dum in 1899. The hollow point (or cup nose) of the Mark IV ensured that it mushroomed on impact, causing significant wounds. The accompanying article explained that while this kind of ammunition might be “doomed for modern warfare”, these bullets were nevertheless essential for dealing with “savage tribes” who required more wounding than “civilized” European soldiers. Source: “The English Mark IV Cordite Ammunition”, Scientific American, Vol. 81, No. 8, 1899, p. 122.

In contrast, this article demonstrates that there was nothing all that new or particularly innovative about expanding ammunition, or the discourses that evolved around its use. Before the invention of cordite in the 1880s, in fact, most rifle bullets were made of soft lead, which expanded, fragmented or deformed on impact, causing terrible wounds and often leading to death. Anyone who hunted with rifles understood these principles of wounding very well, as did most soldiers. The article also demonstrates that at least at the outset, the return to expanding ammunition by the British aimed at making essential improvements to what they considered a faulty military technology (the Mark II .303-inch calibre bullet).Footnote 25 The new expanding versions of the .303 ammunition were also intended for use against all enemies, and not only colonial or non-European ones. The Mark IV and Mark V .303-inch rifle bullets that were introduced in 1897 and 1899 respectively had hollow points, which expanded and wounded much like the dum-dum did.Footnote 26 Both ammunitions were manufactured at the Woolwich Ordnance Factory and in associated factories across the British Empire.Footnote 27 The Ordnance Department did not, in fact, stop manufacturing or issuing these expanding bullets to troops until the invention of a new bullet – the Mark VI – in 1906.Footnote 28 Even Bertie-Clay's dum-dum cartridges continued to be produced and used in India after 1899.Footnote 29 In other words, for the British military authorities in the 1890s, the killing power of expanding bullets was a military necessity in all settings and against all enemies. It took the 1899 Hague prohibition for the British to alter these practices, and even then they did so reluctantly and haphazardly.

This article charts the industrial development of rifle ammunition from the 1850s through to the early 1900s. It focuses on the British Empire particularly and shows how each technological evolution inspired a wide-ranging engagement on its costs and benefits in the Anglo-European media, and especially among lawyers, doctors, military personnel, hunters and politicians. Given that the rifle was an essential military tool but also a vital tool for civilian use, be it for hunting, sport or self-defence, and had been for decades, very few of the ideas presented in the arguments for and against the adoption of dum-dum bullets in the late 1890s were, in fact, all that new. In that sense, this article asserts that while the 1899 dum-dum prohibition may have been a product of a media spectacle, it was also the outcome of decades of public fascination with technological change, rifles and their bullets, and the “just” limits of State and non-State violence.

The industrial development of rifle ammunition

Before the rifle came the musket. Most muskets required the user to ram gunpowder and a projectile into the bore of the gun before igniting the powder that set the bullet in motion – a time-intensive task for which a soldier had to be standing fully upright, exposed to an enemy's shot.Footnote 30 A musket's range was a few hundred yards at best. Rifled muskets, however, became effective military weapons after the invention of paper- or cloth-encased cartridges filled with gunpowder and a conoidal projectile that expanded on propulsion. As it expanded, the bullet gripped the rifled grooves in the gun's barrel and was propelled forward with greater speed, range and accuracy than the smooth-bored musket could offer.Footnote 31

From the 1850s on, breech-loading rifles loaded with cartridges from the side of the gun began to replace smooth-bore muskets. The adoption of industrially manufactured metallic cartridges (as opposed to weather-affected paper or cloth ones) enabled users to reload their breech-loaders while lying down. Alongside massively increasing their rate of fire from sheltered positions, soldiers wielding these guns could strike targets hundreds or, when they were well trained, thousands of metres away.Footnote 32 The rifle and its metal cartridges thus presented a revolution in military tactics and ensured that by the 1870s, infantry soldiers had become “more than ever the arm of service upon which all the hard fighting devolves, which inflicts and receives the greatest damage, and to which all other parts of the army are merely subsidiary”.Footnote 33 By the early 1890s, military surgeons noted that 80% of battlefield wounds were caused by small arms ammunition.Footnote 34 The rifle and its bullets were formidable products of the age of industrialization.

The first effective rifle bullets – such as the Minié projectile – were made from soft lead. What expanded on propulsion to grip the rifled barrel also expanded at the point of termination on hitting a target.Footnote 35 In other words, most rifle bullets were expanding ones until the invention of steel-cased bullets in the late 1880s. As a medical treatise published in 1916 explained, these soft-lead bullets “caused enormous destruction of tissue and as the arms from which they were propelled became more and more perfect, the severity of the wounds increased markedly”.Footnote 36 It is no wonder that some experts still describe the Minié bullet as the “angel of death”.Footnote 37 Many of these soft-lead bullets were made even more expansive when hollowed out – Captain Edward Mounier Boxer's standard-issue ammunition for the British Snider-Enfield rifle (see Figure 4) had a hollow nose, for example. This hollowing aided projection and accuracy in flight, tightening the bullet's centrifugal force and expanding its striking range.Footnote 38 The hollow-point also caused awful wounds: as Vivian Dering Majendie and Charles Orde Browne's 1870 treatise on breech-loaders explained, the Boxer cartridge was a “man-stopper that smashed bone and cartilage and left wicked wounds”.Footnote 39

Figure 4. An 1872 rendering of the Boxer cartridge for the British Snider-Enfield rifle, with its hollow-tip nose that was known to cause massive expansion and fragmentation when it hit a target. Source: “Weapons of War V: Breech-Loading Small Arms”, in Cassell's Technical Educator: An Encyclopaedia of Technical Education, Vol. 1, Cassell, London, 1884, p. 272.

Military doctors in the 1850s and 1860s certainly noted the wounding power of soft-lead ammunition.Footnote 40 Henry Dunant's celebrated account of the battle of Solferino in 1859, for example, discussed cylindrical bullets that “shatter bones into a thousand pieces”, causing wounds that “are always very serious. Shell splinters and conical bullets also cause agonizingly painful fractures, and often frightful internal injuries.”Footnote 41 Yet few of these commentators sought to curtail the use of these conoidal bullets; this was because there was no ready alternative to the rifle as an effective infantry weapon,Footnote 42 and for the rifle to work best – at least until the cordite innovations of the 1880s – it required a soft-lead bullet that could grip the gun's barrel grooves.

The St Petersburg Declaration of 1868

The St Petersburg Declaration of 1868 is particularly important because it constrained the wounding impact of rifle bullets by prohibiting the insertion of explosive or incendiary powders into the projectile's cavity. By the late 1860s, an array of exploding bullets existed, most of which were developed by enthusiastic inventors, hunters and weapons manufacturers.Footnote 43 As early as the 1820s, Captain John Norton invented an exploding bullet that was set off by an external fuse, which he enthusiastically showed off alongside an array of other inventions at public fairs held across England.Footnote 44 In the late 1850s, the British officer John Jacobs (of Jacobabad fame) outfitted his South Asian mercenaries with exploding rifle shells, which were privately manufactured for him in Britain by George Daw.Footnote 45 During the US Civil War (1862–65), both armies experimented with exploding ammunition as well, including what were known as Gardner shells.Footnote 46 British ordnance factories manufactured exploding bullets for their Metford guns in 1863, while their Russian counterparts designed their own version of the ammunition that same year.Footnote 47 The celebrated French hunter Eugène Pertuiset collaborated with the industrialist Leopold Bernard Devisme to produce a range of exploding bullets in the 1860s as well.Footnote 48 Meanwhile, Major Fosbery trialled his own version of an exploding bullet in India to help British troops set artillery ranges in the mountains.Footnote 49 By 1868, then, most European armies had some form of exploding ammunition in production for their military-issue rifles.Footnote 50

These military elites were also planning on the long-term strategic use of these exploding bullets. Evidence provided by experts at the British Special Committee on Breech-Loading Rifles, which met in 1868, certainly understood their tactical effectiveness. In response to the question, “Is it your opinion that the [exploding rifle] shell has no disadvantage whatever?”, Sir Henry St John Halford, a colonel in the Leicester Volunteers and renowned rifleman, answered:

[I]t has none whatsoever. I have a very strong feeling about the shell. I am almost certain that the French will have these shells at once, and I believe that no troops can stand against them: the moral effect produced is, I am told, fearful.Footnote 51

The Dutch military, for its part, both adopted the Daw-design bullets in 1867 and trialled Pertuiset's bullets in 1866.Footnote 52 Media attention and sensationalism followed these bullets’ use, in part because other forms of explosive weaponry also made headline news, including the Orsini bomb, a home-made exploding device invented to assassinate Emperor Napoleon III in 1858 that killed several innocent bystanders instead.Footnote 53

When the governments at St Petersburg agreed to suspend the military use of “explosive projectiles under 400 grammes in weight” in 1868, they did so mobilizing very strong legal language, namely:

That the progress of civilization should have the effect of alleviating as much as possible the calamities of war;

That the only legitimate object which States should endeavour to accomplish during war is to weaken the military forces of the enemy;

That for this purpose it is sufficient to disable the greatest number of men;

That this object would be exceeded by the employment of arms which uselessly aggravate the sufferings of disabled men or render their death inevitable; That the employment of such arms would, therefore, be contrary to the laws of humanity.Footnote 54

While the language was assertive in its humanitarian intent, the reasons for the adoption of the St Petersburg prohibition were layered with military pragmatism.Footnote 55 It is certainly true that a new set of longer-range, faster and more accurate rifle bullets (all expanding, some hollow-nosed) had recently been invented, including the Boxer cartridge.Footnote 56 This ammunition was easier to use than the exploding projectile, even if the latter had its uses for blowing up ammunition dumps or setting artillery gauges. Still, the St Petersburg Declaration was also adopted out of fear that the nature of warfare would change too much if governments allowed their citizen-soldiers to be exploded by the rifle fire of their enemies.Footnote 57 As a result, it was the “needlessness” of the exploding bullets in causing disproportional wounds that caught the media's attention.

Much of the English-language newspaper commentary on the St Petersburg Declaration in 1868 engaged at some level with the idea that “nothing but the strongest necessity” can justify a highly violent act.Footnote 58 As an example, in response to the St Petersburg negotiations of 1868, the The Times reported on the employment of Major Fosbery's exploding bullets during the Umbeyla (Ambela) campaign of 1863. The report explained that while the bullets certainly helped to set effective artillery ranges, they could also hit humans. The resulting wounds were so dreadful that the Pathan sent an emissary across the front line to request that the British troops halt their use. A letter to the editor published in The Times described these wounds as follows:

In one instance the bullet had entered at the back of the neck and then exploding had entirely blown away the face; and in another, where the ball had struck just over the heart the effect was even more terrible to witness. In such cases an ordinary bullet would have caused death equally well, … but where a limb or other part of the body, where an ordinary wound would not prove vital, was struck it was, of course, worse for the victim as he could hardly survive the shock to the system, and the advantage to us was nil, as in 99 cases out of 100, a simple bullet would have placed him hors de combat just as well. It therefore appears that, as a means of destruction, explosive bullets only cause unnecessary mutilation and suffering.Footnote 59

For the author of this letter at least, these wounds were severe enough to prohibit the ammunition's use in any military setting, colonial or otherwise.

Other commentators were less concerned about the wounding power of the exploding projectiles. They argued that the stronger the weapon, the less likely an enemy would be to engage in war, and that given that all war is horror, restricting the use of a particular weapon on the grounds of the horror it caused was nonsensical. The Pall Mall Gazette published a lengthy editorial in June 1868 along these lines. It argued that since a hollow-nosed bullet was as destructive as any exploding bullet, if they were going to ban one on the basis of cruelty, they should also ban the other. At any rate, so the editorial continued, setting a sustainable standard for humanizing warfare was nigh impossible because “war is in itself such great cruelty”.Footnote 60 A popular British sports and hunting magazine, the Field, concurred, although it also acknowledged that “needless cruelty” should be removed from warfare as in hunting.Footnote 61

Given that most contemporaries understood that warfare already involved rules and restraints, the St Petersburg Declaration was not all that innovative – to condemn exploding bullets was no different from condemning the killing of civilians or the employment of poisonous weapons in time of war.Footnote 62 As the Earl of Malmesbury explained in the House of Lords, the explosive bullet was a “diabolical invention” whose use was comparable to these other uncivilized practices.Footnote 63 The Sheffield Daily Telegraph also observed that “to insist on [missiles] which mangle and shatter after they have disabled their victim is simply a superfluity of barbarity worthy only of wild Indians”.Footnote 64 Excessive injury and suffering in time of war was entirely avoidable and, thus, implementing effective bans like this one differentiated “civilized” warriors and nations from “uncivilized” ones.

The racist precepts of these British discourses on acceptable wartime violence are vitally important, not least because the adoption of the St Petersburg Declaration was made binding only on its signatories. If they wished to, the signatory powers could use exploding bullets whenever their enemy was not European “like them”, had not signed up to the decree, or had employed the technology first.Footnote 65 Any army could use the ammunition with impunity against colonial enemies or in a police action against a non-State actor. As the Illustrated London News exalted in December 1868, these “explosive missiles” are “still available for the conversion of Arabs, Maoris [sic], and red Indians. Rose water for our civilised enemies, oil of vitriol for the others.”Footnote 66 In this sense, “humanitarian” rules like the St Petersburg Declaration only underlined that in international law, some bodies were considered more woundable than others.Footnote 67 Still in keeping with the spirit of the The Times' editorial regarding the 1863 Ambela campaign, any use of illegal technology also invited public questioning and debate. The racial and imperial frameworks in which international law operated during the nineteenth century were contested, including among the imperialists themselves.

Civilian uses of the rifle and its ammunition

Of course, the rifle was more than a tool of war. It also served many civilian functions, including as a tool for hunting, sport, farming, self-defence, crime and policing. By the 1870s, rifles and their varied ammunitions were highly sought-after commodities traded in enormous quantities (both openly and clandestinely). Exploding and expanding ammunitions were prodigiously marketed to consumers by the many private companies that manufactured them. Promoted with evocative names like the “Savage”, “Express” or “Tweedie” bullet, advertisements, sports catalogues and newspaper editorials lauded the excellence of these “man-stopping” projectiles for downing any soft-skinned animal, be it a deer, tiger, bear, whale or, for that matter, human being.Footnote 68

When hunting, of course, it ideally takes one shot to kill – and the bigger the wound, the faster the result. Most Anglo-European hunters agreed that an animal ought not to suffer needlessly;Footnote 69 hunting bullets, therefore, ought to cause maximum damage and kill their targets quickly. In a military engagement between “civilized” opponents, however, the opposite was said to be true.Footnote 70 Thus, the very bullets that some commentators wished to extricate from military settings for their ability to wound and kill were consumed in vast quantities on the civilian market. In fact, Pertuiset's exploding bullets gained notoriety in the 1860s in part because of the inventor's lion-hunting prowess and his well-advertised hunting trips that allowed the wealthy to try out his explosive invention on large game in exotic environments.Footnote 71 The painter Édouard Manet immortalized Pertuiset in 1881 in an iconic painting, his double-barrelled hunting gun at the ready, kneeling in front of a downed lion.Footnote 72

Medical conceptualizations of legitimate rifle wounds

A significant amount of nineteenth-century commentary on rifle bullets and their wounds was also written by medical professionals, who augmented their medical notes from battlefield surgeries with photographs of wounds and experiments on cadavers, as well as accounts of their own hunting experiences and rifle-shooting competition results.Footnote 73 In so doing, they passed judgement not only on the nature of wartime wounds and how best to treat them, but also on what levels of violence ought to be allowed within the laws of war. Their medical assessments were steeped in imperial and racial prejudices. Thus, while these doctors uniformly asserted that their primary duty was to extend the lives of soldiers and to minimize suffering,Footnote 74 they also differentiated European soldiers, whom they considered uniformly worthy of such care, from non-European troops, whom many (though by no means all) of them considered less worthy of it.Footnote 75

After 1868, the terms of the St Petersburg Declaration also informed much of these individuals’ medical commentary. During the Franco-Prussian War, for example, after both belligerents accused their enemy of the “uncivilized” practice of employing exploding bullets, these medical experts readily weighed in.Footnote 76 They analyzed battlefield wounds and recovered spent ammunition. They found little evidence to prove that either France or Germany actually used weapons that fit the St Petersburg definition of an exploding bullet (that is, ammunition “of a weight less than 400 grammes which is either explosive or charged with fulminating or inflammable substances”).Footnote 77 What they did uncover was that many of the wounds created by standard rifle bullets were as destructive as any exploding bullet; subsequent experiments conducted on animals bore out these claims.Footnote 78 These findings resulted in various calls to proscribe expansive soft-lead bullets as well as other kinds of excessively destructive weapons, including torpedoes, in the lead-up to the Brussels Convention of 1874.Footnote 79 After all, these weapons also caused superfluous wounds and unnecessary suffering. In these ways, medical expertise and scientific experimentation matched with legal norms to affirm the limits of the laws of war.Footnote 80

That this commentary also considered the use of exploding bullets in imperial and racial terms is most obvious from an 1870 Manchester Guardian editorial that compared the French conscription of Algerian troops to the use of exploding ammunition thusly: “between a Turco and an explosive bullet there appears to us to be small room for choice; and of the two the last is probably the least barbarous”.Footnote 81 Still, by the time of the first Anglo-Boer War (1876–77), claims that the Transvaal had stocks of explosive bullets on hand led the British secretary of State for the colonies to demand that “recourse will not be had to so barbarous a method of prosecuting the war”; the use of explosive bullets was “a practice so atrocious in itself, … condemned by all civilized nations, and is likely even to lead to horrible retaliation by the natives”.Footnote 82 Media reports on the Russo-Turkish War of 1877 focused on similar narratives differentiating the employment of “barbarous” rifle ammunition from “civilized” wounding practices.Footnote 83 All these reports highlight that well before dum-dum bullets became controversial in the 1890s, Anglo-Europeans debated, questioned, moralized and racialized the wounding power of small arms ammunition.

Humanitarian bullets and the dum-dum regression

The most important change affecting rifle technology between the 1870s and the 1890s was the introduction of cordite, a smokeless gunpowder that enabled the adoption of smaller-calibre, sleeker bullets encased in hardened non-expanding metals. This new ammunition increased the speed, range and accuracy of rifles; it was also lighter, so it could be carried by soldiers in greater amounts and loaded more easily into repeating weapons like the Maxim and Gatling machine guns. The British version of this new ammunition was the Mark II .303-inch cartridge, which the British forces introduced for their Lee-Metford rifles in 1892. Other versions included Germany's Mauser and the Austrian Männlicher bullet.

From the outset, military surgeons were keen to assess how these smaller bullets would alter wartime medical practices. Using experiments on animals and cadavers, examples from battlefield surgeries and a degree of conjecture, they argued that at long ranges, the wounds from this new ammunition were more easily treatable than those caused by the larger-calibre bullets used in the older rifles.Footnote 84 The solid bullets made cleaner, less ragged wounds than the older expanding ones. Thus, as long as a wounded soldier could reach a surgeon quickly, their lives could more easily be saved. While they were cautiously optimistic about the potential of the new “humanitarian” bullets to save lives,Footnote 85 some of the surgeons also remarked that military hospitals would need to be moved further away from the battlefront in order to stay out of the bullets’ range. They further urged that all soldiers be given first-aid training so that any wounded could reach the hospital before their “clean” wounds bled out.Footnote 86 The most thoughtful surgical analysts, however, urged another note of caution, namely that at short ranges, there was very little that distinguished the wounding power of this cordite ammunition from any previous rifle cartridge.Footnote 87 This last point was generally lost on the reading public, however, who were more interested in the “humanitarian” claims associated with these bullets.

The British military authorities certainly regretted the adoption of these “clean” bullets in 1892. Their experiences with Mark IIs at Chitral and Malakand were highly discouraging, in large part because the bullets did not kill enough of the enemy. As one British newspaper reported it, the bullets “cause very little pain to those who are struck by them”,Footnote 88 and that was a problem when facing a “rush of fanatics” who would not hesitate to kill a European soldier by the most brutal means if given half a chance.Footnote 89 Sensational stories of a man in Chitral who was struck five times by Mark II bullets but then walked home to heal made headline news around the Empire, and continued to be a recurring trope in justifying British soldiers’ use of the dum-dum.Footnote 90 Medical officers further noted that indigenous healing techniques handled the Mark II wounds so well that the injured recovered within weeks.Footnote 91 One doctor even exclaimed that

there can be little doubt that from a humanitarian point of view the Lee Metford rifle is a perfect weapon. The bullet obviously inflicts very little damage on soft tissues and on bones its action is apparently not very severe …. I infer that the Lee-Metford rifle is an excellent weapon in every respect but one, that is, will it stop a rush? Footnote 92

Similarly, during the Jameson raid conducted by the British against white Afrikaners in the Transvaal in 1895, troops used both the Martini-Henry rifle with its soft-lead bullets and the Lee-Metford gun shooting Mark IIs. The medical officers in attendance subsequently reported that the Mark II ammunition created wounds that were “much cleaner and healed more quickly than those produced by other methods”. In contrast, the Martini-Henry wounds were “larger, jagged, slow-healing”. They concluded that “the general consensus of opinion among those who saw the effects of the fighting in South Africa, is that the Lee Metford rifle or carbine is inferior to the Martini as a ‘man-slaying’ weapon”.Footnote 93 If “man-slaying” was needed, the Mark II would not deliver.

In so many ways, then, the dum-dum represented a return to earlier (more expansive) formats of rifle bullets – those which were more likely to guarantee a deadly result. And for some medical experts, at least, the shift back was essential. The US surgeon major-general John B. Hamilton, for example, felt compelled to defend the dum-dum bullet in a revealing commentary published in the British Medical Journal in 1898. Hamilton's lengthy article argued that the dum-dum bullet was less destructive than the Snider-Enfield cartridge (first used in the 1860s), whose “‘smashing’ powers were so great that it was adopted for sporting purposes”. He went on to explain that on “soft-bodied animals, such as tigers and panthers, its effects were wonderful, the biggest tiger often dropping dead to a single shot when well placed”. Hamilton further noted that while explosive bullets were made illegal in military settings in 1868, he nevertheless enjoyed their “most deadly” effects on game: “I shot a great deal of heavy game with it in India, and never lost an animal I knew I had struck.” Accordingly, since “savages” were “like the tiger” and less “susceptible to injury” than “civilised” men, and since they “will go on fighting even when desperately wounded”, Hamilton had no problems with Europeans using “man-stopping” bullets in warfare conducted against those whom he considered less-than-human enemies.Footnote 94 A kill placed any man hors de combat too.

For the British Ordnance Department, the limitations of the Mark II, which wounded but failed to easily kill the enemy, needed rectification. Ordnance staff conducted experiments with .303-inch ammunition both in Britain at Hythe, Woolwich and Dungeness and at the Dum Dum Arsenal in India, where Bertie-Clay was given the honour of producing the moulds for what was identified as Mark II* ammunition.Footnote 95 As some commentators complained with vitriol, there was very little new about Bertie-Clay's dum-dum design. They had certainly been hunting with such bullets for years!Footnote 96

The Mark II* dum-dum bullet and the newly designed Mark IV and Mark V expanding bullets were highly effective at “stopping” their victims, so much so that when Pathan troops captured stocks of dum-dums at the Battle of Tirah, they used them with equally deadly effect on British troops.Footnote 97 It is highly significant, then, that the Ordnance Department adopted the Mark IV ammunition for all service rifles late in 1897.Footnote 98 The British aimed to employ these bullets against all their enemies, be they colonial or European.

But when the media furore around dum-dum bullets broke soon after, this universally destructive ambition left the British government facing a political quagmire. Editorials across the Anglo-European world lambasted the “regressive” British for their uncivilized adoption of this military technology. Even a highly conservative military commentator in the Netherlands considered dum-dum wounds “horrifying” (gruwelijk) and used the most lurid description to make a case for their prohibition: “skin, soft tissues and bones were rent asunder across an extensive area, shredded and splintered, while whole pieces were lacerated off, so that limbs were often only connected together by strips of skin or singular tendons”. The author hoped that the Hague Conference would resolve that this “most inhumane bullet” should never be used in European warfare. “Civilized” men, in his opinion, deserved to be kept alive and not suffering from needlessly cruel wounds.Footnote 99

Before the Hague Conference, Britain's official response to these critiques was to stress that its expanding ammunitions were not exploding bullets (and so the terms of the St Petersburg Declaration did not apply) and, furthermore, that they were no more destructive than existing rifle rounds. English commentators tended to find these rationales more convincing than foreign ones.Footnote 100 By and large, outside Britain, the only rationale deemed appropriate for employing expanding bullets was a racist one. Scientific American certainly minced few words on the matter in August 1899: “When dealing with a fanatic like the Soudanese, a war of extermination must be carried on, and the Dum-dum bullet seems to be the most effective [weapon].”Footnote 101 The Wichita Daily Eagle promoted a similar message a year earlier:

Dum-dum bullets are especially designed for the use against savages. … In civilized warfare all that is desired is to put a man out of the game by disabling him, which one ordinary bullet will accomplish, but the superior endurance of the savage has necessitated the use of a projectile that will kill him. In other words, he has to be dum-dummed.Footnote 102

It is important to stress that after the signing of the Hague Conventions in August 1899, dum-dums and other expanding bullets were more roundly (although by no means universally) criticized, including in Britain and the United States. While there were commentators who continued to argue for the necessity of employing expanding bullets in imperial settings, in general, the Hague law ensured that most contemporaries publicly acknowledged “dum-dumming” as an abhorrent act regardless of who was being targeted or who was doing the shooting. Even the previously pro-dum-dum Daily Mail turned into a critic of the ammunition after 1899.Footnote 103

The fact that the British military authorities continued not only to use but also to produce expanding bullets after 1899 is, therefore, telling. They did not much care for this Hague regulation. At any rate, since Britain did not sign up to the Hague Declaration until 1907, its military leadership did not feel compelled to adhere to the Declaration's terms. Yet they also acknowledged that the political fallout around the use of expanding bullets required careful stage-managing in the public sphere. Hence, the British government recalled all Mark IVs from South Africa, and demanded that British troops only employ the defective Mark II bullets.Footnote 104 Britain's ordnance factories reverted to manufacturing Mark IIs for the duration of the Anglo-Boer War.

In the meantime, the Army Board, Admiralty and Ordnance Department debated with the Cabinet about what ammunition to stock in future. The military preferred the newly designed hollow-nosed Mark V. The Cabinet implemented a compromise: for the foreseeable future, the military would employ both Mark V and Mark II bullets.Footnote 105 The Mark II would be “used wherever there is no risk of attack from savages”, although in an emergency any available ammunition (expanding or not) would do.Footnote 106 India could keep manufacturing and employing dum-dum bullets,Footnote 107 for as a War Office memorandum on the subject acknowledged in December 1899, in the wake of The Hague, “it is better to have Mark II for civilised and some form of expanding bullet for savage warfare than to make Mark V the universal pattern”.Footnote 108 To further hide its use of expanding bullets, in all settings, the government employed euphemistic terms like “ordinary” or “standard-issue” ammunition in its public documents,Footnote 109 as these politicians certainly wished to avoid another public relations crisis.Footnote 110

Conclusion

The prohibition of expanding bullets at The Hague in 1899 was easily achieved. It also offered an expedient “success” story for conference organizers to promote, which was particularly important given that most of the other arms control negotiations at The Hague firstly stalled and then failed.Footnote 111 At any rate, as many of the delegates thought, given that expanding bullets were only employed by the British, the British would bear the brunt of their prohibition. In this they were proven quite wrong, for much like the St Petersburg Declaration of 1868, The Hague's dum-dum prohibition solidified the expectation that certain forms of military harm should be proscribed, particularly when less deadly or destructive alternatives were available. That norm infiltrated the global media sphere in the aftermath of the 1899 Hague Conference and continues to have enormous relevance in international humanitarian law and how we perceive the limits of warfare and State violence today.

There is no doubt that The Hague's dum-dum prohibition forced the British State to carefully manage the propaganda around its use of expanding rifle ammunition after 1899 in imperial and non-imperial settings. In managing these public relations campaigns, it was not alone. Most of the wars of the early twentieth century, including the First World War, were beset with dubious claims and counter-claims of illegal dum-dum use. Still, it is also true that some of the worst instances of State violence committed during the twentieth century, much like those of the nineteenth, involved expanding ammunitions. It is important to recognize that these acts were not only committed by the British.Footnote 112 Expanding bullets remain in use today, including in police actions; you can buy blue-nosed expanding bullets in any hunting shop. It is also true that turning a full-metal-jacket bullet into an expanding one is rather simple: all that is needed is to file away its tip or insert cross-cuts.Footnote 113

Whenever they are used, however, expanding bullets occasion controversy, in part because of the existence of the Hague law but also because they do enormous harm – they are “man-slayers”, after all. And perhaps that is the dum-dum's most enduring legacy: the trope of the “barbarous dum-dum” is more evocative than effective in restraining the hounds of war and State violence.