The Qajar state was a familial state. Qajar princes held most of the provincial governorships, while many of the offices that comprised the Qajar administration (dīvān) were occupied by individuals who were descended from administrative families, were related to other administrative families, and were related to the ruling Qajar house.Footnote 1 The fact that Qajar Iran's politics and administration were largely a family affair is not news, nor does it make Qajar Iran exceptional. Historians of 19th-century Iran, especially those writing in Persian, have long drawn attention to the familial nature of Qajar-era politics.Footnote 2 And historians of other regions, from Western Europe to Japan, have written extensively on elite families and the politics of the aristocracy.Footnote 3 Nevertheless, numerous questions about the historical role of political families in Qajar Iran remain underexplored. Chief among them is how a focus on those families—and especially those families who served in the dīvān—might change our understanding of the early Qajar period and the formation of the Qajar state.

The production of Qajar power and the emergence of a Qajar state are among the least understood, though most deserving, topics in 18th- and 19th-century Middle Eastern history. The story of the formation of Qajar Iran can be summarized as follows: in 1722, the Safavid Empire collapsed. Political turmoil and instability marked much of the remainder of the 18th century. Nadir Shah Afshar (r. 1736–47) and Karim Khan Zand (r. 1750–79) ruled for some time, but neither managed to establish states that outlasted their own lives. Meanwhile, the Qajars were one among several tribal groups vying for power. Agha Muhammad Khan Qajar (r. 1785–97) defeated his Zand rivals and crowned himself shah in 1796. Only one year later, however, he was assassinated. His nephew, and designated successor, Fath-ʿAli Shah (r. 1797–1834), took the throne at a time when several competitors, including some of his own relatives, refused to recognize his rule. Given this situation, it is not surprising that the prevailing wisdom among historians is that 18th-century Iran witnessed “tribal resurgence” and a general political and economic downturn.Footnote 4 And yet, during the period stretching from 1785 to 1834—what can be called the early Qajar period—the Qajars successfully consolidated political power to rule over what they called the “guarded domains of Iran” (mamālik-i maḥrūsih-yi Īrān).Footnote 5 Fath-ʿAli Shah himself ruled for thirty-seven years, and the Qajars remained in power until 1925. For bringing to a close a politically turbulent period, the rise of the Qajars is a watershed moment in Iranian history.Footnote 6

Historians have written about the early Qajar period in one of three ways. Some scholars, influenced by Weberian theories of state formation, have focused on the creation of offices by Qajar rulers, especially Fath-ʿAli Shah, and the bureaucratic capacity of the Qajar state.Footnote 7 Those efforts have often been framed as a precursor to later 19th-century attempts to create a more centralized, bureaucratic, and by extension “modern” state.Footnote 8 Another group of historians has placed the rise of the Qajar state in the context of 18th- and 19th-century religious developments. According to this body of scholarship, during the 18th century the social and political influence of the Shiʿi ʿulamaʾ grew, and by the early 19th century Qajar rulers had to contend with the ʿulamaʾ’s ascendant power.Footnote 9 Finally, a third body of scholarship has depicted the rise of the Qajars as a “tribal” story. The Qajar state emerged, we are told, as a result of the Qajars defeating their rivals, conquering territory, and consolidating power through tribal modes of rule.Footnote 10

A socially oriented approach to Qajar politics, institutions, and the state offers an alternative pathway to understanding the history of the early Qajar period.Footnote 11 An obvious place to undertake such an approach would be with the administrative offices that comprised the Qajar dīvān. The ministers, secretaries, scribes, and historians who served in the dīvān were the cornerstone of the Qajar government. They were responsible for the government's central tasks: diplomacy, political counsel, tax collection, and the writing, copying, and transmission of decrees (firmān) and correspondence. Doing a socially oriented study of the dīvān would entail identifying the main office holders, tracing their family, social, and geographic backgrounds, highlighting the marital ties between office holders, and uncovering their sources of economic and social prestige. It would mean taking seriously the familial nature of the Qajar state—not just as a description of the Qajar polity, but as a clue to how power was produced and reproduced in the formative years of the Qajar period.

Socially oriented approaches to political history have made headway in much of the scholarship on imperial and state formation. Scholars have increasingly questioned the traditional binary between state and society, and have argued that mundane processes, informal practices, and relationships in society involving individuals, networks, and institutions all contribute to upholding political order.Footnote 12 Some have advanced the notion of familial states in other contexts.Footnote 13 Others have gone so far as to question the very category of the “state,” preferring to explore the practice of governance.Footnote 14 The case of Qajar Iran suggests, like much of this scholarship, that social and economic ties have historically been central to consolidating political power, and that schematic conceptions of state institutions and offices erase the many intricate and complex ways in which power is formed.

An analysis of the familial nature of early Qajar political history also elaborates on scholarship within Middle Eastern history. Two of the more recent and productive considerations of the relationship between families and political power have been in the scholarly literature on provincial households in the Ottoman Empire and in Qajar Iran, and in the debates over whether merchants and merchant families were “autonomous” from political power.Footnote 15 The scholarship on provincial households largely grew out of an interest in the “politics of notables” (a ʿyān)—those individuals in the Ottoman Empire who, in the words of Albert Hourani, acted “as intermediaries between government and people, and … as leaders of the urban population.”Footnote 16 At its best, the “politics of notables” scholarship has forced scholars to reevaluate assumed dichotomies between imperial and local, state and civil society, and in the case of the Ottoman Empire, Ottomans and Arabs.Footnote 17 But by concentrating on specific provinces or regions and, typically, on the later periods of Ottoman and Qajar history, these studies have also tended to emphasize processes of decentralization—the devolution of power from the imperial center to provincial and local levels.Footnote 18 The scholarship on merchants, meanwhile, has explained what merchants did historically, rather than what normative definitions of merchants would lead us to believe they did. By doing so, scholars have usefully drawn attention to the nexus between merchant families and institutional power, and to the social, economic, and political activities in which merchant families engaged.Footnote 19

Ultimately, a socially oriented approach to Qajar political history and to the three dīvān offices that are the subject of this article—the Grand Vizier (ṣadr-i a ʿẓam), the Imperial Accountant (mustawfī al-mamālik), and the Imperial Secretary (munshī al-mamālik)—revises the prevailing interpretations of the early Qajar period.Footnote 20 Several different but related points emerge through a reading of the relevant sources—including biographical poetry anthologies (taẕkirih),Footnote 21 family histories,Footnote 22 histories of political offices,Footnote 23 and chronicles.Footnote 24 At the most basic level, the socially oriented approach adopted here pushes back against reified understandings of the Qajar state. The early Qajar state had elements of both patrimonial and bureaucratic rule, with both genealogical modes of governance occurring alongside the differentiation of offices without any necessary contradiction.Footnote 25 A second point, and one that is closely tied to the first, is that there was both continuity and change in the social composition of the Qajar state. Qajar rulers recruited men into their dīvān who themselves had served earlier governments, or were descended from families with long administrative experience, but they also recruited men with little or no administrative background. Ministers who served in the dīvān then entrenched their interests by marrying into the Qajar house. And finally, a third point that emerges from the sources: ministers who served in the dīvān sought to bolster their power and prestige by carrying out duties that went beyond normative descriptions of their offices, through cultural and economic pursuits, and by competing with one another, sometimes violently. Taken together, the three points illustrate the contingent process by which the Qajar state emerged, formed, and was made—a helpful reminder that the early Qajar state was very much a “state in the making.”Footnote 26

Beyond a Weberian State

During the early Qajar period, the differentiation of offices and genealogical modes of governance occurred simultaneously. Among Agha Muhammad Khan's first acts, after escaping captivity in Shiraz following Karim Khan Zand's death in 1779, was to recruit a treasurer (mustawfī). From there the number of offices in the dīvān grew, and by the end of Fath-ʿAli Shah's reign the dīvān was the largest it had been since the Safavid period.Footnote 27 Sources from the early Qajar period attest to the fact that the prime minister, imperial treasurer, and imperial secretary were among the principal positions in the nascent Qajar state. At the same time, early Qajar sources often and repeatedly mention the family lineages of political men, reminding us that family backgrounds and relationships were a vital factor in who was recruited to fill dīvān positions.

Analyzing the order in which offices were filled is one way to detect the significance of each office relative to others. It is telling that Agha Muhammad Khan took as his first minister a treasurer, Mirza Ismaʿil, whom he recruited shortly after returning to Mazandaran in 1779. Soon thereafter, he took another treasurer, Mirza Asadullah Nuri, as his revenue secretary to the army (lashkarnivīs).Footnote 28 Meanwhile, the first imperial secretary under the Qajar ruler seems to have been Mirza Riza Quli Navaʾi, who was appointed in 1791 or 1792.Footnote 29 The position of prime minister was only filled a couple years later, in 1794, when Agha Muhammad Khan appointed Muhammad Ibrahim, the former city mayor (kalāntar) of Shiraz during the Zand period, to the post.Footnote 30 Together, these individuals comprised Agha Muhammad Khan's dīvān.

During the first few decades of the 19th century, Fath-ʿAli Shah expanded the administration, and the shah established greater division of labor between the offices. In 1806 or 1807, Fath-ʿAli Shah officially divided the central dīvān into four offices: the chief minister, the imperial treasurer, the imperial secretary, and minister of war. The shah's court chronicler, Mirza Fazlullah “Khavari” Shirazi, provided a description of the responsibilities of each office:

First is the ṣadr-i a‘ẓam, who is responsible for providing counsel [muhimmāt-i shūr-i mamlikat] and for appointing and dismissing governors [vilāt va bayglarbaygān], the heads, deputies, rulers, and chiefs of the court and every province, and is also responsible for military and government affairs. Second is the vazīr-i istīfā-yi mamlikat [i.e., the mustawfī al-mamālik] who oversees all financial matters, and who collects and disburses revenue, gifts [pīshkish], and taxes [māliyāt] of regions near and far. Third is the vazīr-i dār al-inshā who by custom is known as munshī al-mamālik and keeps the records of diplomatic correspondence and imperial decrees. Fourth is the vazīr-i ‘askar who heads military affairs, and is in charge of dispensing salaries and stipends to the royal troops, for presenting troops to the shah, and recruiting new soldiers.Footnote 31

Each minister's responsibilities were, in theory, well defined with a clear division among the advisory, financial, secretarial, and military officials. The nucleus of the central Qajar administration, which would continue to grow and expand during the 19th century, was thus created within the first ten years of Fath-ʿAli Shah's reign.

Fath-ʿAli Shah's development of the dīvān was an effort to recreate the structure of Safavid administration, but also part of a broader strategy to resurrect the Safavid imperial system.Footnote 32 Shirazi's descriptions of the early Qajar dīvān offices echo the descriptions that Safavid-era administrative manuals, like the Tazkirat al-Muluk (Memorial for Kings), provided for similar political offices.Footnote 33 In formal terms, the early Qajar dīvān continued in the tradition of the Safavid dīvān—in fact, as an institution, the dīvān probably had roots dating to the Sasanian Empire (224–551 CE).Footnote 34 At the same time, however, Agha Muhammad Khan and Fath-ʿAli Shah expanded their territorial reach to former Safavid domains. In 1785, Qajar control was limited to the Alburz region, along the southern littoral of the Caspian Sea, and beyond that, to some areas in northern and northwestern Iran.Footnote 35 By the middle of the first decade of the 19th century, the Qajars had effectively extended their authority from the Caucasus in the north to the Persian Gulf in the south, and from Kermanshah in the west to Khurasan in the east—the approximate frontiers of the Safavid Empire in the late 17th century.Footnote 36 In that sense, the growth in the number and organization of offices should also be seen as reflecting the rising demands of a growing empire.

Expanding Qajar territorial control also meant that there was a need for ministers and secretaries to be based in cities and towns across the empire. Provincial cities across Qajar Iran, including Tabriz, Shiraz, Mashhad, Isfahan, Kermanshah, Qazvin, Yazd, and Kerman, all had Qajar prince-governors with their respective ministers, secretaries, and scribes. Some of these provincial dīvān officials were promoted up the chain to Tehran, with Tabriz and Shiraz being especially noteworthy “feeder” cities.Footnote 37 But an underappreciated point is that the provincial administrative system was not limited to well-known provincial capital cities. The city of Nakhchivan, which until 1828 was part of the Qajar province of Azerbaijan and under the aegis of ʿAbbas Mirza, is a good example. Hundreds of early 19th-century decrees (firmān), petitions, and other forms of correspondence survive from the local Nakhchivan dīvān. Because the correspondence includes political orders and requests exchanged between Tehran, Tabriz, Nakhchivan, and other locales, two noteworthy points emerge: first, the provincial town of Nakhchivan was linked to other Qajar provincial cities, as well as to larger capital cities; second, there were secretaries and scribes active in the local Nakhchivan dīvān who wrote and recorded the political correspondence that now survives.Footnote 38 It is not unreasonable to imagine similar situations in smaller cities and towns across Qajar domains.

A growing administration at the capital, provincial, and local levels also contributed to the relative political stability under early Qajar rulers, especially when compared to the 18th century.Footnote 39 While other factors besides the dīvān—including legal institutions, provincial households, and mercantile activity—undoubtedly contributed to the political and economic recovery of the Qajar period, an expansion in the number of ministers, secretaries, and scribes meant that the business of governing could be done. The evidence for economic recuperation under the early Qajars is fragmentary, but a statement of revenue from 1811, for example, captures the Qajar state's ability to raise and collect taxes. The statement is a record of the 1.7 million tūmān in cash and kind raised from various provinces, districts, and tribes (īlāt) across Qajar territories.Footnote 40 Taxes collected at the local level were sent to the district level, then up to the provincial level, until finally reaching the capital, Tehran.Footnote 41 While much of Iran's financial situation during the 18th century remains obscure, and thus difficult to compare to the situation of the early 19th century, the evidence suggests that the government improved its ability to raise revenue under Qajar rule.Footnote 42 It would be no exaggeration to say that the ministers of the dīvān, who maintained financial records and ledgers across Qajar territories, made much of this economic recuperation possible.

On the other hand, too great an emphasis on the growing institutions of the Qajar state obscures the personal and patrimonial ties that ran through the Qajar government. There is perhaps no greater evidence for how important family genealogies were in the early Qajar period than in the abundance of details about those genealogies scattered across different sources.Footnote 43 The names and background of ministers and secretaries are often found, for instance, in early Qajar-era biographical anthologies (taẕkirih), among the names of poets, historians, and other lettered men (and sometimes women).Footnote 44 If the individuals were descendants of the prophet Muhammad's family, this would deserve special mention.Footnote 45 In other cases, entries declare the family's long background in politics, as in the case of the Qaʾim-Maqam Farahani family: “the majority of his [Mirza Abu al-Hasan ʿIsa] ancestors, ancestor after ancestor, grandee after grandee, served in the ministries of illustrious sultans.”Footnote 46 Chronicles and other histories often provide similar kinds of statements.Footnote 47

As the following section will illustrate, although family lineage was by no means the only consideration for choosing dīvān ministers it was undoubtedly among the main factors in who was selected. By the time Fath-ʿAli Shah died in 1834, at least sixteen different individuals had held the positions of prime minister, imperial secretary, and imperial treasurer (see Table 1), and four of them were descended from men who held a high-ranking post in earlier polities. Others may have been descended from local officials who held less noteworthy positions. It is true that under Fath-ʿAli Shah the Qajar administrative structure grew and differentiated into discrete political offices. But patrimonial and informal networks of power persisted well into the Qajar period.

TABLE 1. Dīvān Ministers

Continuity and Change

The Qajar state was simultanesouly a continuation of older polities and a break with those polities. This is different than saying that Qajar political culture drew on a rich tradition of Persian, Islamic, and Turco-Mongolian rituals and concepts while adapting them to the circumstances of the 19th century, or that the administrative offices created by rulers like Fath-ʿAli Shah had roots in earlier polities—both of which earlier scholars have demonstrated.Footnote 48 Instead, the point here is that the social composition of the state was both old and new. Qajar rulers recruited men into their dīvān who themselves had served earlier governments, or were descended from families with long administrative experience, but they also recruited men with little or no administrative background. These men then married into the Qajar house, and their descendants became princes, princesses, and statesmen themselves. Well into the 20th century, descendants of Qajar-era marriages were among Iran's political and cultural elite.

Continuities between Afsharid, Zand, and Qajar rule ran deep and cut across all of the major positions in the Qajar administration. The first prime minister under the Qajars, Muhammad Ibrahim Iʿtimad al-Dawlih, is particularly noteworthy because of the circumstances under which he came into Qajar service. His family was originally from Qazvin, until Nadir Shah made Muhammad Ibrahim's father, Muhammad Hashim, the alderman (kadkhudā) of the Haydari quarter of Shiraz. Muhammad Ibrahim's own political career began later, under the Zands, when he worked under the mentorship of the mayor (kalāntar) of Shiraz, Mirza Muhammad, before being promoted to mayor of the city himself in 1785.Footnote 49 During the Qajar siege of Shiraz in 1790–91, Muhammad Ibrahim sensed the imminent downfall of the Zands, defected against his Zand overlords, and pledged allegiance to the Qajars.Footnote 50 A few years later, Agha Muhammad Khan made him prime minister, marking the beginning of his political career with the Qajars (Fig 1).Footnote 51

FIGURE 1. Iʿtimad al-Dawlih (standing) with Agha Muhammad Khan. © The British Library Board. Inside back cover of Add. 24903, The British Library.

Several other individuals with similar backgrounds were recruited in the early years of Qajar rule. Mirza Shafiʿ, the second prime minister of the Qajar period, was the son of Haji Mirza Ahmad, who had served Nadir Shah.Footnote 52 The Amin al-Dawlih's father and grandfather served as “stewards” (mubāshir) of Isfahan during the Zand period.Footnote 53 And Mirza Muhammad Riza “Bandih,” who under the orders of Fath-ʿAli Shah helped compile the general chronicle Zīnat al-Tavārīkh (The Ornament of Histories), was the son of Mirza Muhammad Shafiʿ Tabrizi, a financial officer for both Nadir Shah and Agha Muhammad Khan.Footnote 54

The case of the Farahani family, meanwhile, is especially noteworthy because they served Safavid, Zand, and Qajar rulers and therefore represented a chain of continuity through the vagaries of 18th-century politics.Footnote 55 Ancestors of Mirza Abu al-Qasim Farahani had served numerous shahs through the centuries, and by the late Safavid period, Mir Abu al-Fath Farahani was the keeper of the seal (mīr-i muhrdār) in the Safavid court.Footnote 56 Mir Abu al-Fath's son, and the later Qaʾim-Maqam's paternal great-uncle, Mirza Muhammad Husayn Farahani “Vafa,” served the Zands as a chief minister (vazīr-i sarkār-i umarā ʾ) and imperial accountant.Footnote 57 Mirza Abu al-Qasim's father, the first Qaʾim-Maqam Mirza Abu al-Hasan ʿIsa, had entered Qajar service during the reign of Agha Muhammad Shah. After Fath-ʿAli Shah acceded to the throne in 1797, he first appointed Mirza Abu al-Hasan as minister to his son Hasan-ʿAli Mirza in Tehran, before moving him to the court of ʿAbbas Mirza, where he took the title Qaʾim-Maqam and served until he died of plague in 1821 or 1822.Footnote 58 He was replaced by his son, Mirza Abu al-Qasim who became the new Qaʾim-Maqam upon his father's death. In addition to these two ministers, ʿAbbas Mirza appointed Haji Haydar Ali Khan as his vizier (ṣadr) for a couple years. Further underlining the continuities between Zand and Qajar rule, Haydar Ali was related to Iʿtimad al-Dawlih, the first Qajar ṣadr who had also served the Zands.Footnote 59

The background of the Farahanis points to another feature of the early Qajar administration: the apprenticeship and education that ministers received was an additional conduit of continuity through different political rulers. Sources therefore also provide information about ministers’ training and the supervision under which ministers began their careers. To give a few examples: Iʿtimad al-Dawlih, aside from being the mayor of Shiraz under the Zands, also served as an apprentice under Mirza Muhammad Husayn Vafa, the head of the Farahani family, in effect linking him back to the late Safavid bureaucratic elite as well.Footnote 60 Meanwhile, Mirza Mirza Isa Qaʾim-Maqam was in turn trained by Iʿtimad al-Dawlih.Footnote 61

Continuities such as these were not limited to the central administration in Tehran, but were also evident at the provincial and local levels. Qajar rulers preferred to leave secretaries and fiscal officers in place, rather than appoint new officials, after conquering new territory. Mirza ʿAli Bayg, a secretary (munshī) in Nakhchivan's dīvān, provides an illustrative example. ʿAli Bayg was born before the Qajar conquest of Nakhchivan, in the late 18th century, to a family that had served as secretaries in the region for years.Footnote 62 He seems to have been responsible for collecting, copying, and compiling dozens of petitions, decrees (firmān), and other correspondence from the Nakhchivan archives that stretched from the early 18th to the early 19th century—material to which he would have had easy access given his family background. The access to documents his family origins gave him also made him well positioned to write a brief history of some of the notable political figures of Nakhchivan, including Kalb-ʿAli Khan.Footnote 63 ʿAli Bayg's short biography of Kalb-ʿAli Khan, combined with the archival documents he copied and compiled, provide a portrait of Kalb-ʿAli Khan that is missing from most Qajar chronicles and narrative sources, which only mention him and his tribe, the Kangarlu, in passing.Footnote 64 ʿAli Bayg, by contrast, provides a granular account of Kalb-ʿAli Khan's role in Nakhchivan and in the early 19th-century Russo-Persian wars. The account is unique, and goes some way towards explaining why the Qajars would allow local officials, who had deep familiarity with and knowledge of their region, to continue serving under their rule.

There were pragmatic reasons for why Qajar rulers favorably viewed continuities along family, educational, and experiential lines. To be a minister, a secretary, or a historian serving an administrative role required knowledge and expertise in penmanship and diplomatics, in record-keeping techniques like siyāq, and in other subjects, like Arabic grammar and the Islamic sciences, that were central to the ministerial ethos of the “men of the pen.”Footnote 65 Recruiting men who had been raised in administrative families, had been trained by ministers, or simply had experience were among the surest ways to ensure capable individuals were staffing the government.

Nevertheless, there were ministers who lacked such links in their background, a reality that stands out even more when juxtaposed with the continuities between Safavid, Afsharid, Zand, and Qajar rule. Take, for instance, Qajar tribal khans. Most Qajar khans became provincial governors or military leaders—that is to say, not dīvān officials—but among the earliest examples of a Qajar being selected for a ministerial position was Allah Yar Khan, son of Mirza Muhammad Khan, of the Devellu clan of Qajars.Footnote 66 Allah Yar Khan began his career as a steward (khwānsālār) to Fath-ʿAli Shah, before eventually being given the title Asaf al-Dawlih, and becoming, in effect, the prime minister.Footnote 67 As the 19th century progressed, and in part as a result of the numerous examples of marriages between the Qajar royal family and scions of ministerial families, an increasing number of individuals from the Qajar house were appointed to ministerial and secretarial positions.

But “outsiders” in the dīvān during the early years of Fath-ʿAli Shah's reign were not exclusive to Qajar tribal khans. Muhammad Husayn Khan, the governor (bayglarbayg) of Isfahan, provides an example of someone who rose from humble origins to become the prime minister and to the pinnacle of power. Although his father and grandfather had been local stewards (mubāshir), they lacked a true dīvān background. Originally a green grocer from Isfahan, Muhammad Husayn Khan's first promotion was to become the alderman (kadkhudā) of his neighborhood in the city. From there, he worked to build alliances with local shopkeepers, merchants, and farmers, gradually making his way up to becoming the mayor (kalāntar) of the city.Footnote 68 Muhammad Husayn Khan came to the attention of Fath-ʿAli Shah when the new shah passed through Isfahan on his way to Tehran to take the throne, following Agha Muhammad Khan's death. In 1806, Fath-ʿAli Shah brought him to Tehran, appointed him to serve as imperial treasurer, and gave him the title Amin al-Dawlih.Footnote 69

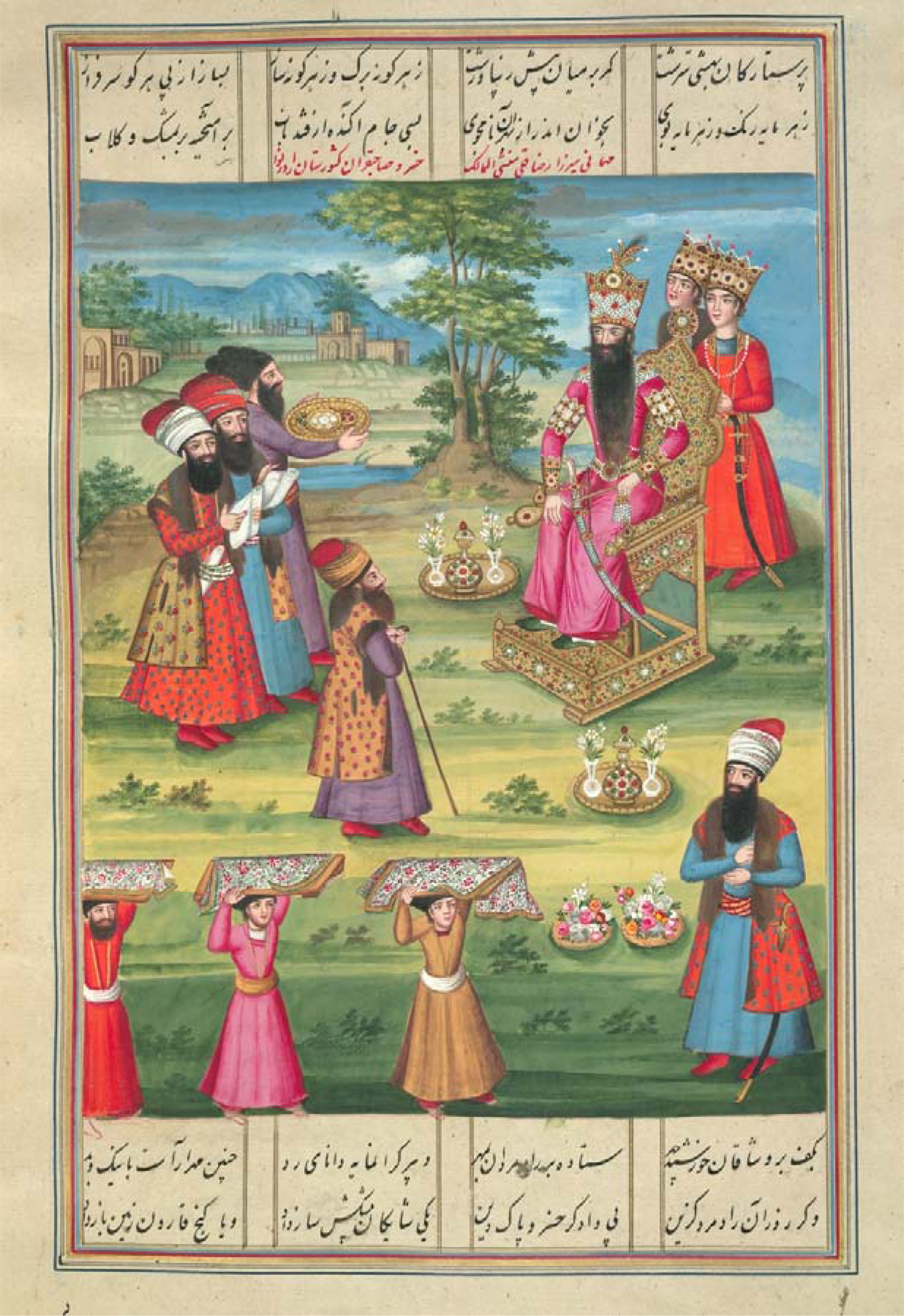

The fact that Muhammad Husayn Khan was promoted up to a prestigious position is an indication that Qajar rulers took other factors besides family lineage into consideration. Loyalty was one such consideration, and the giving of gifts helped express loyalty to Qajar rulers.Footnote 70 A timely and luxurious gift that Muhammad Husayn Khan gave to Fath-ʿAli Shah in 1801–2, while he was still the governor of Isfahan and on the occasion of the shah's marriage to Tavus Khanum, surely helped his career prospects: a gem-studded “Sun Throne,” later renamed the “Peacock Throne” (takht-i ṭāvūs) in honor of the shah's wife.Footnote 71 Part of the explanation for the gift may lie in the fact that Muhammad Husayn Khan was close to the family of Tavus Khanum, both of whom were from Isfahan, but the gift, coming as it did early in Fath-ʿAli Shah's reign, may also have been made with an eye toward solidifying Muhammad Husayn Khan's political prospects.Footnote 72 Gifts from ministers to the shah were not uncommon. A manuscript of the Shahanshahnama, an epic poem about Fath-ʿAli Shah's reign modeled on Ferdowsi's Shahnama, includes a painting of Mirza Riza Quli Navaʾi, the imperial secretary, presenting gifts, including cash and textiles, to the shah (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2. Mirza Riza Quli, the munshī al-mamālik, presenting gifts to Fath-ʿAli Shah Qajar © The British Library Board. IO Islamic 3442, f 64v, The British Library.

Almost as soon as the Qajar dīvān began to take shape, the families that held offices attempted to bolster their positions by marrying into the Qajar house. Marriages between the Qajars and ministerial families fit a broader pattern of marital ties between Qajar rulers and urban notables, provincial khans, and other social groups during the early 19th century. Ministerial families married other ministerial families, of course, but marriages with the Qajar household inextricably linked them to the royal family, and as the 19th century progressed, the descendants of these unions, who numbered well into the thousands, formed a significant portion of the political elite.

The numerous marriages between the children of the shah and ministers make it clear that the division between the royal court (dargāh) and the administration (dīvān), which may have existed at a theoretical level, was in reality blurred.Footnote 73 Fath-ʿAli Shah had at least 160 wives and over 260 children, including sixty sons and fifty-five daughters who survived him.Footnote 74 The majority of these children did not marry into ministerial families, but there were many who did. The daughters of Iʿtimad al-Dawlih, Mirza Shafiʿ, and Muhammad Husayn Amin al-Dawlih all married Qajar princes.Footnote 75 Mirza Ismaʿil Khan Halal-Khur, the son of the mustawfī and munshī Mirza Faridun Khanlar, was married to the shah's sixteenth daughter Dirakhshandih Gawhar Khanum.Footnote 76 The shah's twenty-eighth daughter, Khurshid Kulah Khanum, was married to Mirza ʿAli Muhammad Khan, the son of ʿAbd Allah Khan Amin al-Dawlih.Footnote 77 Similar examples can be found among the children of other ministers as well. In other cases, office holders themselves married into the Qajar house, as in the case of Mirza Abu al-Qasim Qaʾim-Maqam II, who married Gawhar Malak Khanum, the full sister of the early Qajar crown prince ʿAbbas Mirza and the shah's ninth daughter.Footnote 78

The marriages also point to the male-dominated political culture of Qajar Iran. The names of women are generally omitted from the sources, and fathers are given preference when tracing family lineages. We know relatively little about the mothers and sisters of dīvān ministers, with the notable excetption of those who were Qajars. Secretaries and historians eulogized the Qajar house by writing biographical sketches of Qajar shahs and princes, but also their wives and princesses.Footnote 79 In some cases, Qajar women also received education and training from ministers, a point that historians also took care to note. Muʿtamid al-Dawlih, for instance, taught the shah's favorite wife, Tavus Khanum, how to read and write.Footnote 80

Many of the children and grandchildren of the marriages between Qajar rulers and ministerial families continued to be politically influential well into the 19th century and beyond. The descendants of these unions may have numbered in the thousands by the late 19th century.Footnote 81 The example of Iʿtimad al-Dawlih illustrates the varied political activities of these individuals. One of Iʿtimad al-Dawlih's sons served as governor (bayglarbayg) of Shiraz, while another was governor of Kashan, during the early 19th century. Meanwhile, among his grandchildren and great-grandchildren, several of them became notable politicians during the latter half of the 19th century, including Mirza Fath-ʿAli Khan, who was the head of the dīvān (sāḥib-i dīvān) in the late-Fath-ʿAli Shah period and remained prominent into the reign of Nasir al-Din Shah (r. 1848–96), Mirza Muhammad Riza Qavam al-Mulk III, who was the governor of Shiraz, and Mirza Husayn Khan Muʿtaman al-Mulk, who served the Qajar state in Khurasan.Footnote 82 Iʿtimad al-Dawlih's brothers, and their children—Iʿtimad al-Dawlih's nephews—also held important political positions, both during the reigns of Agha Muhammad Khan and Fath-ʿAli Shah, and later in the 19th century.Footnote 83

In fact, as Fath-ʿAli Shah's reign progressed, and the years of Qajar rule went on, certain families became closely associated with specific ministerial positions. For instance, the Ashtiyani family came to dominate the position of imperial treasurer: Mirza Muhammad ʿAli served first as mustawfī, but then his brother Mirza Hasan continued the family line. Hasan's son Yusuf succeeded his father as mustawfī in the Muhammad Shah (r. 1834–48) period.Footnote 84 The Nuris were also a prominent administrative family: Mirza Asadullah Nuri was recruited by Agha Muhammad Khan in 1795–96 to serve as his minister of the army, before switching over to become the imperial treasurer under Fath-ʿAli Shah.Footnote 85 His son, Mirza Agha Khan Nuri, later also served as army minister for the shah.Footnote 86

Loyalty and marriage tied ministerial families to the Qajar house, and ensured some level of security for dīvān officials. But because during the early 19th century the size of the administration grew, and the number of ministers increased, there was also greater competition among the ministers. From the perspective of the ministers, the dīvān was a space where competition over power, prestige, and influence played out.

Qajar Courtly Encounters

Early Qajar dīvān office holders had origins in various cities and regions across Qajar domains. The dīvān can be viewed, in fact, as a point of contact between Qajar rulers based in capital cities like Tehran, and men with social and economic roots in the provinces. Seen this way, the dīvān was an arena where networks of provincial power encountered one another; politically ambitious men competed with each other; political, economic, and social benefits became entrenched; and rivalries, feuds, and even violence erupted between dīvān ministers. The dīvān, in other words, offered an opportunity for ministers to prove their worth and consolidate their personal power and prestige, but also presented the risk of losing that same power. Qajar Iran's early history again demonstrates that, as in the case of many other imperial courts, incidents of encounter, exchange, and violence were constitutive elements to court culture and state formation.Footnote 87

The dīvān’s function as a site of contact for Qajar Iran's regional and political elites becomes easier to appreciate when one is reminded that the sixteen individuals who held the positions of prime minister, imperial secretary, and imperial treasurer during the first three decades of Qajar rule came from six different regions and eight different cities. Some of the cities, like Shiraz and Isfahan, were home to numerous influential families because of their historic roles as political capitals. Other cities and towns, like Nur and Bandpay, in Mazandaran, were not urban centers of particular importance, but were closer to the Qajars’ ancestral homeland in Astarabad. Agha Muhammad Khan and Fath-ʿAli Shah's decision to draw some of their ministers from these localities was part of a broader shift in the center of political gravity away from the south and towards the north at the turn of the 19th century.Footnote 88 But the geographic diversity of the towns and cities represented, from Shiraz to Tabriz, and from Navaʾi to Astarabad, also reflected a willingness by the shahs to draw on expertise from across their domains (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3. Geographic origins of ministers. The size of the dots reflects the number of ministers from that town or city. Map by Assef Ashraf.

The ministers who were recruited into the dīvān from these various locales then began carrying out basic political and economic tasks of the government that sometimes went above and beyond the traditional definitions of their offices. Even a cursory survey of the variety and nature of the tasks Qajar rulers entrusted to dīvān officals makes this point abundantly clear: without them, there would be no Qajar government that one could speak of beyond the palace walls. The officials served as emissaries and representatives of Qajar rulers, kept political and financial records, and produced literary, historical, and cultural texts that presented a particular vision of the Qajar state. The sheer variety of these activities had the effect of adding to their prestige and their self-fashioning as men worthy of being dīvān ministers, in conjunction with—or regardless of, as the case may be—what their family lineage was.

The skills of ministers were especially put to the test when they were delegated to serve as representatives of Qajar rulers, and dispatched to carry out diplomatic and political missions. In 1803–4, for instance, Fath-ʿAli Shah sent Mirza Shafiʿ on a mission to Azerbaijan to ease local tensions in the face of Russian military activities in the region. In May-June 1804 he reached Yerevan, where he met with Muhammad Khan Qajar, the governor (bayglarbayg) of the city. Fath-ʿAli Shah had received information that Muhammad Khan was collaborating with the Russians. In the course of negotiations with the governor, Mirza Shafiʿ assured the governor that if he recommitted his loyalty to the Qajars, he would face no retribution. Soon after, the governor of Yerevan sent a gift (pīshkish) and a letter of loyalty (farmān-i barādarī) to ʿAbbas Mirza, the Qajar prince-governor of Azerbaijan.Footnote 89

Instances when nothing less than Qajar authority was at stake offered particularly good occasions for ministers to prove their abilities. In May 1796, Agha Muhammad Khan was preparing for his final assault on Shusha and Azerbaijan, the only regions among former Safavid territories that he had not yet conquered. According to Iʿtimad al-Saltanih, “apparently he [Agha Muhammad Khan] felt in his heart that this journey would be his last journey,” and therefore made appropriate preparations.Footnote 90 He took most of his commanders and advisors with him, including Iʿtimad al-Dawlih, his prime minister, but ordered Mirza Shafiʿ and Muhammad Khan Qajar Devellu, the governor of Tehran, to stay behind in Tehran. Agha Muhammad Khan instructed Mirza Shafiʿ that should anything befall him, under no circumstances was Mirza Shafiʿ to permit any of the “princes, ministers, or military commanders” (shāhzādigān va vuzarāʾ va umarāʾ) into the city, until the heir-apparent—i.e., Baba Khan, the future Fath-ʿAli Shah—arrived from his post as governor of Fars to take the throne. As it turned out, Agha Muhammad Khan conquered Shusha, but was then assassinated by three men in his retinue as Qajar forces marched on Georgia.Footnote 91 Agha Muhammad Khan's senior advisors, including his prime minister, Iʿtimad al-Dawlih, and his brother, Husayn Quli Khan, rushed back to Tehran to inform others of the shah's death. Mirza Shafiʿ, however, true to his orders, refused to allow even the prime minister and the late shah's brother back into the capital. He immediately sent a messenger to Shiraz to summon their heir, Baba Khan, to Tehran. Only when he had arrived, were others also allowed back into the capital.Footnote 92

Diplomatic and political missions, such as those above, were obvious tasks for dīvān ministers, but these ministers also attempted to bolster their prestige through social, cultural, and economic pursuits. To take the example of ʿAbd Allah Khan Amin al-Dawlih: he expended a great deal of effort and resources to revitalize Isfahan, by building schools, parks, and other structures. During his tenure in Fath-ʿAli Shah's dīvān, the population of Isfahan reportedly grew to 300,000—a sharp rebound following the decline of the 18th century, and close to the population during the Safavid era.Footnote 93 Meanwhile, men like Abu al-Qasim Farahani Qaʾim-Maqam wrote poetry and prose that were widely praised during his own time. His literary output included panegyrics (qaṣīda) and popular poetry in his Jalāyirnāma (The Book of Jalayir), as well as a collection of official correspondence, letters of friendship (ikhwāniyāt), essays, and introductions to other works.Footnote 94 Another prime minister, Muʿtamid al-Dawlih, wrote under the pen name Nashat, and was among Fath-ʿAli Shah's favorite poets.Footnote 95 Some of this work was intended to legitimize Qajar rule or promote the Qajars as defenders of the faith, while in other cases it was more aesthetic.Footnote 96 Finally, ministers accumulated wealth through real estate and land purchases. The Qaʾim-Maqam, Nuri, and Ashtiyani families, among others, became wealthy landowners during the early 19th century, a fact that became even more apparent when they lost parts of their wealth as a result of competition with other ministerial families.Footnote 97 Taken together, and when considered alongside the marriage alliances between Qajar rulers and ministerial families, these activities remind us of the many different ways in which political elites reinforce their elite position within society.

Nevertheless, ministers could fall precipitously and violently from power. In fact, rivalry, factionalism, and violence were critical elements in the early Qajar dīvān. A well-known example of a minister's demise is Muhammad Ibrahim Iʿtimad al-Dawlih, who, despite having a long and distinguished career serving both Zand and Qajar rulers, and being related to the Qajars through marriage, was ultimately executed in 1801 after being accused of conspiracy and betrayal.Footnote 98 The circumstances surrounding Amin al-Dawlih's demise provide another example. In early 1824, a certain Hashim Khan led a rebellion of the Lur population of Lunban, in Isfahan. The governor of Isfahan at the time was ʿAli Muhammad Khan, who was the son of Amin al-Dawlih, and also son-in-law of Fath-ʿAli Shah.Footnote 99 He was, at the same time, a nephew of the rebellion's leader, Hashim Khan, which led to the suspicion that he was not taking proper steps to stop the rebellion. Fath-ʿAli Shah marched on Isfahan after the Nowruz celebrations, and after quelling the uprising, blinded Hashim Khan, removed ʿAli Muhammad Khan as the governor, and replaced him with his son Sultan Muhammad Mirza as the governor. In what was possibly further retribution, Amin al-Dawlih—the erstwhile governor's father—was removed as prime minister and in his place the shah appointed Allah Yar Khan Asaf al-Dawlih, a Qajar from the Devellu clan.Footnote 100

Violent episodes such as these were not unusual in Qajar and Iranian history—or for that matter in the history of other empires and states. Examples of ministerial downfall in the Iranian context suggest a weakness in administrative power, but they also lay bare the ministerial competition among men vying for their own interests. In the case of Iʿtimad al-Dawlih, Mirza Shafiʿ, a secretary to Iʿtimad al-Dawlih, was also his fierce rival, and may have played a part in engineering his superior's downfall in order to secure his own place as prime minister.Footnote 101

Conclusion

In trying to understand how and why the Qajar state formed, close attention to the social makeup of the state—who served in the administration, what their social and economic background was, and how they were related to one another and to the Qajars—is as significant as which ideology shaped the government or which political offices comprised the administration. A socially oriented political history moves us beyond descriptions of the institutional and formal characteristics of the Qajar state. Ultimately, the methodology outlined here has the potential to bring Qajar political history into closer conversation with debates on state and imperial formation animating historians who work on different times and places. From a modern perspective, to say that a state was both bureaucratic and patrimonial, had both old and new social elements, and had a central administration that functioned as an arena for competition among its ministers sounds like a case for its many shortcomings. But in the context of the late 18th century, and in the wake of the political turmoil following the Safavid Empire's collapse, the attributes of early Qajar Iran's politics also serve as a reminder that the making of states is a process defined by both continuity and change (Table 1).