1. Introduction

Ultramafic and mafic complexes are seen in shear zones throughout the East African Orogen (Kazmin, Reference Kazmin1976; Berhe, Reference Berhe1990; Stern, Reference Stern1994, Reference Stern2005; Abdelsalam & Stern, Reference Abdelsalam and Stern1996; Helmy & Mogessie, Reference Helmy and Mogessie2001; Helmy & El Mahallawi, Reference Helmy and El Mahallawi2003; Stern et al. Reference Stern, Johnson, Kröner and Yibas2004; Farahat & Helmy, Reference Farahat and Helmy2006; El-Rahman et al. Reference El-Rahman, Helmy, Shibata, Yoshikawa, Arai and Tamura2012; Helmy et al. Reference Helmy, El-Rahman, Yoshikawa, Shibata, Arai, Tamura and Kagami2014, Reference Helmy, Yoshikawa, Shibata, Arai and Kagami2015; Abdel-Karim et al. Reference Abdel-Karim, Ali, Helmy and El-Shafei2016). These shear zones provide a record of the amalgamation of central Gondwana. The Western Ethiopian Shield (WES) lies in an important position within the East African Orogen, between the predominately gneissic Mozambique Belt in the south, and the greenschist-facies volcanic-arc complexes of the Arabian–Nubian Shield in the north and east. Within the WES, the Kemashi Domain is characterized by a sequence of metasedimentary rocks, interlayered with abundant mafic to ultramafic material. The ultramafic/mafic plutonic rocks within the Kemashi Domain were initially interpreted to represent an ophiolite sequence (Berhe, Reference Berhe1990; Tadesse & Allen, Reference Tadesse and Allen2004, Reference Tadesse and Allen2005); however, others have suggested that there is a lack of geochemical evidence to support the presence of ophiolites in the WES (Mogessie, Belete & Hoinkes, Reference Mogessie, Belete and Hoinkes2000; Braathen et al. Reference Braathen, Grenne, Selassie and Worku2001; Grenne et al. Reference Grenne, Pedersen, Bjerkgård, Braathen, Selassie and Worku2003).

The composition of spinel is both useful as a petrogenetic recorder of mafic magma evolution, and as a discriminator of the geotectonic source of mafic to ultramafic rocks (Irvine, Reference Irvine1965, Reference Irvine1967; Dick & Bullen, Reference Dick and Bullen1984). Spinel crystallizes over a wide range of conditions from mafic and ultramafic magmas, and Cr-rich spinel is the liquidus phase of a broad range of mafic magmas over wide pressure ranges. Spinel is relatively refractory and resistant to alteration, particularly when compared to other high-temperature igneous silicates such as olivine, making it particularly useful as a source indicator in altered rocks. A large database of spinel compositions from a wide range of mafic and ultramafic rock types is available from the published literature (Barnes & Roeder, Reference Barnes and Roeder2001), providing a sound comparative discrimination tool to establish the tectonic setting of mafic and ultramafic rocks (Kamenetsky, Crawford & Meffre, Reference Kamenetsky, Crawford and Meffre2001).

Microprobe data from chrome spinels, as well as from rare relict fresh olivine, are used here to test the two main theories for the formation of the WES ultramafic complexes: either that the complexes are oceanic ophiolites, remnants of the Mozambique Ocean, or that they form in a supra-subduction environment as Alaskan-type ultramafic to mafic intrusions. These data help to further constrain and understand the enigmatic Kemashi Domain as well as further develop the tectonic model for the Neoproterozoic evolution of the WES.

2. The ultramafic quandary

A significant aspect of the Arabian–Nubian Shield is the recognition of the N–S-oriented regional shear zones. The Baruda–Tulu Dimtu zone stretches through Ethiopia and connects with the Barka zone in Eritrea (Stern, Reference Stern1994; Braathen et al. Reference Braathen, Grenne, Selassie and Worku2001; Tadesse & Allen, Reference Tadesse and Allen2004, Reference Tadesse and Allen2005). These regional shear zones have often been interpreted as ophiolite-decorated sutures, representing the major boundaries that separate arc terranes that accreted during amalgamation of eastern and western Gondwana (Stern, Reference Stern1994; Tadesse & Allen, Reference Tadesse and Allen2004, Reference Tadesse and Allen2005). Braathen et al. (Reference Braathen, Grenne, Selassie and Worku2001) questioned this interpretation, and pointed out that the components essential to the identification of ophiolites, such as tectonized mantle harzburgite, sheeted dyke complexes or basaltic pillow lavas with associated pelagic sediments, had not been recognized in Ethiopia (de Wit & Aguma, Reference de Wit and Aguma1977; Braathen et al. Reference Braathen, Grenne, Selassie and Worku2001; Alemu & Abebe, unpub. report, Geological Survey of Ethiopia, 2002; Allen & Tadesse, Reference Allen and Tadesse2003; Grenne et al. Reference Grenne, Pedersen, Bjerkgård, Braathen, Selassie and Worku2003; Woldemichael & Kimura, Reference Woldemichael and Kimura2008; Woldemichael et al. Reference Woldemichael, Kimura, Dunkley, Tani and Ohira2010). Alternatively, Braathen et al. (Reference Braathen, Grenne, Selassie and Worku2001) proposed that the zoned mafic and ultramafic as well as isolated bodies along the shear zone were originally intruded as magma chambers preserving mafic and ultramafic cumulate layering equivalent to so-called ‘Alaskan-type intrusions’ (Mogessie, Belete & Hoinkes, Reference Mogessie, Belete and Hoinkes2000). These intrusions were interpreted to be a result of limited dilation of back-arc basins without the development of extended oceanic crust (Braathen et al, Reference Braathen, Grenne, Selassie and Worku2001; Grenne et al. Reference Grenne, Pedersen, Bjerkgård, Braathen, Selassie and Worku2003). This paper outlines the application of chrome spinel compositions to test the two main theories for the formation of the WES ultramafic complexes: either that the complexes are structurally emplaced ophiolite sheets, remnants of the Mozambique Ocean, or that they formed as Alaskan-type mafic intrusions above subduction zones.

2.a. Alaskan-type intrusions

Alaskan-type zoned mafic–ultramafic complexes are characterized by a concentric arrangement of rock types including dunite, pyroxenite, hornblendite and gabbro. Examples of these complexes have been described from Alaska, the Urals of Russia, eastern Australia, British Columbia and Colombia, as well as the Eastern Desert of Egypt (Dick & Bullen, Reference Dick and Bullen1984; Himmelberg & Loney, Reference Himmelberg and Loney1995; Barnes & Roeder, Reference Barnes and Roeder2001; Helmy & Mogessie, Reference Helmy and Mogessie2001; Helmy & El Mahallawi, Reference Helmy and El Mahallawi2003; Farahat & Helmy, Reference Farahat and Helmy2006). Alaskan-type intrusions are small (ranging from a few metres up to ~ 10 km) in size, elliptical or rounded in shape and located along crustal lineaments. Alaskan-type intrusions are distinguished by (1) the gradation from dunite to gabbros, (2) Fe3+–Ti-rich spinels, (3) depletion of CaO in olivine, and (5) evidence of crystal accumulation such as scarce graded layers (Dick & Bullen, Reference Dick and Bullen1984; Himmelberg & Loney, Reference Himmelberg and Loney1995; Helmy & Mogessie, Reference Helmy and Mogessie2001; Helmy & El Mahallawi, Reference Helmy and El Mahallawi2003; Farahat & Helmy, Reference Farahat and Helmy2006). The chemical composition of chromium spinel, in particular its elevated Fe2O3 content, is another typical feature of Alaskan-type intrusions (Irvine, Reference Irvine1967; Findlay, Reference Findlay1969; Taylor Jr & Noble, Reference Taylor and Noble1969; Himmelberg, Loney & Craig, Reference Himmelberg, Loney and Craig1986; Himmelberg & Loney, Reference Himmelberg and Loney1995; Chashchukhin et al. Reference Chashchukhin, Votyakov, Pushkarev, Anikina, Mironov and Uimin2002; Krause, Brügmann & Pushkarev, Reference Krause, Brügmann and Pushkarev2007). This has been ascribed to high total iron contents in the parental melt (Taylor Jr & Noble, Reference Taylor and Noble1969), fractionation of olivine and clinopyroxene (Findlay, Reference Findlay1969; Krause, Brügmann & Pushkarev, Reference Krause, Brügmann and Pushkarev2007) or an elevated oxygen fugacity (Himmelberg & Loney, Reference Himmelberg and Loney1995; Chashchukhin et al. Reference Chashchukhin, Votyakov, Pushkarev, Anikina, Mironov and Uimin2002). Alaskan-type intrusions are confined to subduction-related magmatic arcs (deBari & Coleman, Reference deBari and Coleman1989; Himmelberg & Loney, Reference Himmelberg and Loney1995; Krause, Brügmann & Pushkarev, Reference Krause, Brügmann and Pushkarev2007; Helmy et al. Reference Helmy, El-Rahman, Yoshikawa, Shibata, Arai, Tamura and Kagami2014)

2.b. Ophiolites

Although the basic definition has evolved somewhat in recent years (Dilek & Furnes, Reference Dilek and Furnes2014), the classic definition of an ophiolite is that of a stratified complex of mafic and ultramafic rocks emplaced by over-thrusting (obduction) onto the passive margin of an ocean in the process of closure, as a result of subduction. The ensemble of mafic and ultramafic igneous rocks is formed by magmatic processes at a mid-ocean ridge and/or beneath an oceanic volcanic arc. Although the latter supra-subduction type is probably most common, the numerous examples of ophiolite complexes that adorn the closed Tethyan suture illustrate that many have combined supra-subduction and mid-ocean ridge characteristics (Dilek & Furnes, Reference Dilek and Furnes2011; Whattam & Stern, Reference Whattam and Stern2011).

Many studies have shown that peridotites in mid-oceanic ridge ophiolite complexes have chromite with Cr# values of < 0.70 (Dick & Sinton, Reference Dick and Sinton1979; Dick & Bullen, Reference Dick and Bullen1984; Stern et al. Reference Stern, Johnson, Kröner and Yibas2004), whereas supra-subduction peridotites have Cr# values of > 75 (Pearce, Lippard & Roberts, Reference Pearce, Lippard, Roberts, Kokelaar and Howells1984; Augé, Reference Augé1987; Ahmed & Arai, Reference Ahmed and Arai2002; Arai et al. Reference Arai, Takada, Michibayashi and Kida2004; Stern et al. Reference Stern, Johnson, Kröner and Yibas2004; Abdel-Karim et al. Reference Abdel-Karim, Ali, Helmy and El-Shafei2016).

The Semail ophiolite in Oman is an example of a complex with both mid-ocean ridge and supra-subduction components. Dunites from the northern mantle section of this complex have spinels with Cr# < 0.6 (Le Mée, Girardeau & Monnier, Reference Le Mée, Girardeau and Monnier2004), similar to those of a fast-spreading ridge (Niu & Hekinian, Reference Niu and Hekinian1997; Arai et al. Reference Arai, Okamura, Kadoshima, Tanaka, Suzuki and Ishimaru2011). By contrast, from peridotite in the more southern part of the same ophiolite, Tamura & Arai (Reference Tamura and Arai2006) reported spinels with supra-subduction affinity with Cr# > 0.6 and from discordant dunites spinels with Cr# ranging from 0.4–0.8 and TiO2 < 0.3 wt % (Arai et al. Reference Arai, Shimizu, Ismail and Ahmed2006). Ophiolitic peridotites that have spinel Cr# that exceed 0.55 and low TiO2 values (< 0.3) suggest derivation from highly depleted mantle peridotite. They imply mantle source depletion due to partial melting and melt extraction beyond the exhaustion of clinopyroxene, leaving a harzburgite residue. This extensive melting is attributed to the role of hydrous subduction-derived fluids (Dick & Bullen, Reference Dick and Bullen1984). Many Tethyan ophiolite complexes, including the Semail ophiolite in Oman, have complex histories whereby initially oceanic upper mantle ophiolites have a supra-subduction history imposed prior to obduction onto the adjacent continental passive margin. As in the Semail ophiolite (Shervais, Reference Shervais2001), this may lead to a complex spinel geochemical record (Leblanc & Nicolas, Reference Leblanc and Nicolas1992; Zhou & Bai, Reference Zhou and Bai1992; Zhou, Robinson & Bai, Reference Zhou, Robinson and Bai1994; Zhou & Robinson, Reference Zhou and Robinson1997; Proenza et al. Reference Proenza, Gervilla, Melgarejo and Bodinier1999; Rollinson, Reference Rollinson2008; Uysal et al. Reference Uysal, Tarkian, Sadiklar, Zaccarini, Meisel, Garuti and Heidrich2009; Escayola et al. Reference Escayola, Garuti, Zaccarini, Proenza, Bédard and Van Staal2011).

3. Geological setting/background

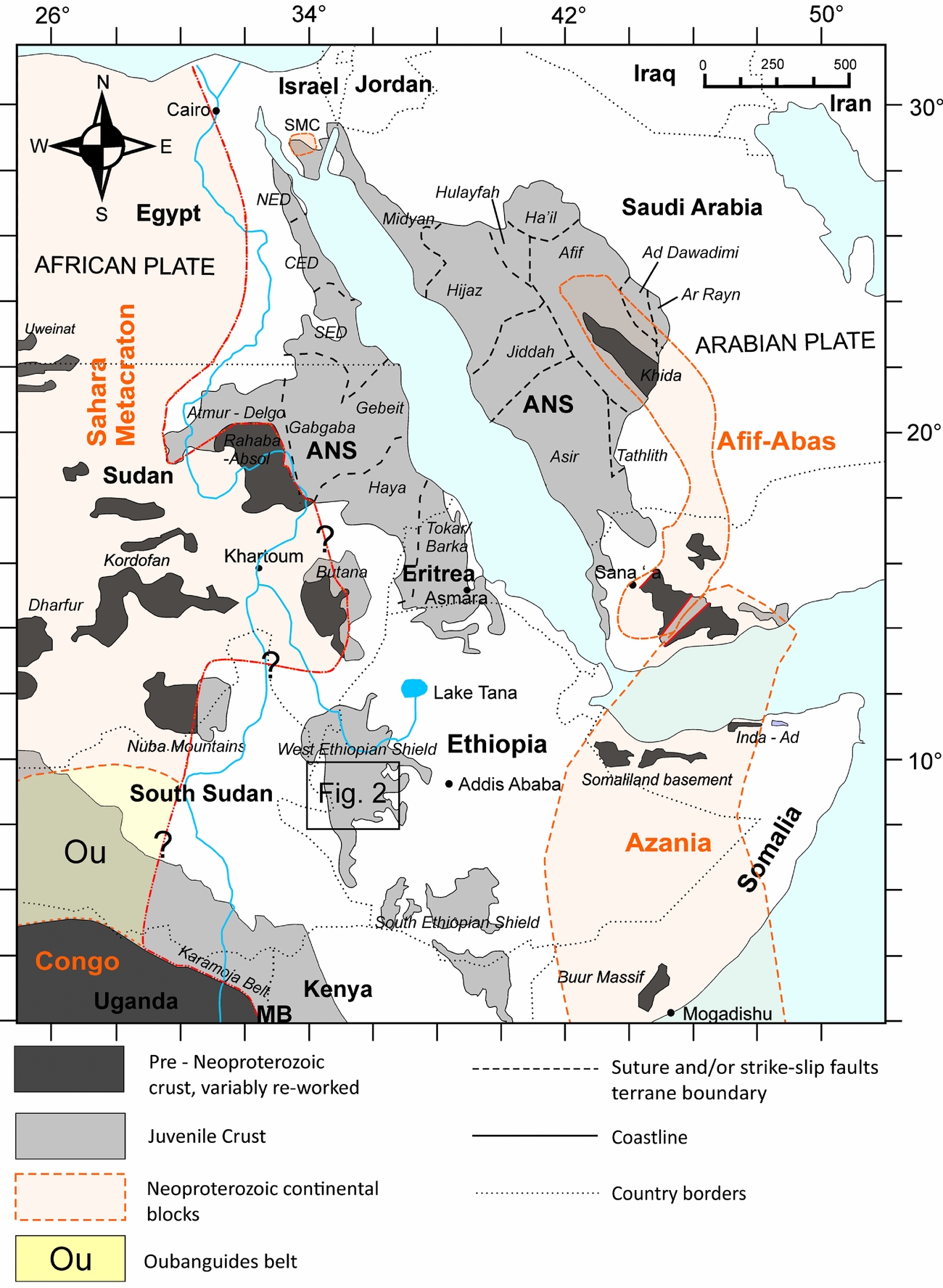

The East African Orogen is the world's largest Neoproterozoic to Cambrian orogenic belt. It preserves a complex history of intra-oceanic and continental margin, magmatic and tectonothermal events. Traditionally, the East African Orogen is divided into the Arabian–Nubian Shield in the north, composed of largely juvenile Neoproterozoic crust, and the Mozambique Belt in the south comprising mostly pre-Neoproterozoic crust with a Neoproterozoic – early Cambrian overprint. Many of the rocks found in the orogen formed in volcanic arcs during the Neoproterozoic subduction of the Mozambique Ocean (Meert, Reference Meert2003; Collins & Pisarevsky, Reference Collins and Pisarevsky2005; Meert & Lieberman, Reference Meert and Lieberman2008; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Andresen, Collins, Fowler, Fritz, Ghebreab, Kusky and Stern2011; Fritz et al. Reference Fritz, Abdelsalam, Ali, Bingen, Collins, Fowler, Ghebreab, Hauzenberger, Johnson, Kusky, Macey, Muhongo, Stern and Viola2013), which separated Neoproterozoic India from the Neoproterozoic continents that formed Gondwanan Africa (Meert, Reference Meert2003; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Ayalew, Mogessie, Kruger and Poujol2004; Collins & Pisarevsky, Reference Collins and Pisarevsky2005; Meert & Lieberman, Reference Meert and Lieberman2008; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Andresen, Collins, Fowler, Fritz, Ghebreab, Kusky and Stern2011; Fritz et al. Reference Fritz, Abdelsalam, Ali, Bingen, Collins, Fowler, Ghebreab, Hauzenberger, Johnson, Kusky, Macey, Muhongo, Stern and Viola2013; Merdith et al. Reference Merdith, Collins, Williams, Pisarevsky, Foden, Archibald, Blades, Alessio, Armistead, Plavsa and Clark2017). The WES (Fig. 1) is situated in a key transitional location between the Arabian–Nubian Shield and Mozambique Belt, adjacent to, and east of, the ‘Eastern Saharan Metacraton’ (Abdelsalam & Stern, Reference Abdelsalam and Stern1996).

Figure 1. Location map and distribution of crustal domains in the East African Orogen. SMC – Sahara Metacraton; ANS – Arabian–Nubian Shield; MB – Mozambique Belt. The black box represents the map area in Figure 2. Adapted from Johnson et al. (Reference Johnson, Andresen, Collins, Fowler, Fritz, Ghebreab, Kusky and Stern2011) and Blades et al. (Reference Blades, Collins, Foden, Payne, Xu, Alemu, Woldetinsae, Clark and Taylor2015).

The WES comprises high-grade gneisses, low-grade metavolcanic and metasedimentary rocks with associated mafic–ultramafic intrusions and syn- to post-tectonic gabbroic to granitic intrusions. In this paper we use the lithotectonic division outlined by Allen & Tadesse (Reference Allen and Tadesse2003), based on domains of shared lithological assemblages and geological histories (see Allen & Tadesse, Reference Allen and Tadesse2003 for a summary). The area is divided into five domains, interpreted to have formed during the final closure of the Mozambique Ocean (Allen & Tadesse, Reference Allen and Tadesse2003); these include the Didesa, Kemashi, Dengi, Sirkole and Daka domains (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Simplified geological maps of the study regions. (a) Simplified geological map of the area of study in western Ethiopia. Adapted from the geological map of western Ethiopia (2nd edition), scale 1:2 000 000, published by the Geological Survey (Woldie & Nigussie, Reference Woldie and Nigussie1996) and Blades et al. (Reference Blades, Collins, Foden, Payne, Xu, Alemu, Woldetinsae, Clark and Taylor2015). (b–d) Simplified geological maps of (b) Yubdo, (c) Daleti and (d) Tulu Dimtu, respectively. Adapted from geological maps from an unpublished thesis (M. Jackson, unpub. Ph.D. thesis, Cardiff Univ., 2006) and Alemu & Abebe (Reference Alemu and Abebe2000).

The Kemashi Domain forms a narrow ~ N–S strip that is 10–15 km wide (Fig. 2) and lies towards the west of the Didesa Domain (illustrated in Alemu & Abebe, Reference Alemu and Abebe2000). Within this domain, there is a prominent expression of the regional Baruda–Tulu Dimtu shear/suture zone (Abdelsalam & Stern, Reference Abdelsalam and Stern1996), sometimes referred to as the Sekerr–Yubdo–Barka suture/shear zone (Berhe, Reference Berhe1990). This domain is characterized by a sequence of metasedimentary rocks, informally referred to as the Mora metasediments, whose protoliths are interpreted to have a marine origin, including pelagic sediments, cherts and quartzites, interlayered with abundant mafic to ultramafic volcanic material, all metamorphosed to upper-greenschist/epidote–amphibolite facies (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Ayalew, Mogessie, Kruger and Poujol2004). Identical lithologies exist to the west of the shear belt, although they are generally more deformed and intercalated with tectonic slivers of metavolcanic rocks (Tefera, Reference Tefera1991; Braathen et al. Reference Braathen, Grenne, Selassie and Worku2001). Published geochronology data suggest three phases of magmatism at c. 850–810 Ma, 780–700 Ma and 620–550 Ma (Ayalew et al. Reference Ayalew, Bell, Moore and Parrish1990; Ayalew & Peccerillo, Reference Ayalew and Peccerillo1998; Kebede, Koeberl & Koller, Reference Kebede, Koeberl and Koller1999, Reference Kebede, Kloetzli and Koeberl2001; Kebede, Kloetzli & Koeberl, Reference Kebede, Kloetzli and Koeberl2001). These have been interpreted to represent pre-, syn- and post-tectonic environments, respectively (Woldemichael & Kimura, Reference Woldemichael and Kimura2008; Woldemichael et al. Reference Woldemichael, Kimura, Dunkley, Tani and Ohira2010). Recent studies have suggested that these are complicated by metamorphism/deformation occurring both at c. 790–780 Ma and at c. 660–655 Ma. Hafnium isotopic analysis indicates that the magmas were generated from juvenile Neoproterozoic mantle sources with little involvement of the pre-Neoproterozoic continental crust (Blades et al. Reference Blades, Collins, Foden, Payne, Xu, Alemu, Woldetinsae, Clark and Taylor2015). Post-tectonic magmatism is recorded in the Ganjii granite (206Pb–238U age of 584 ± 10 Ma), constraining pervasive deformation in the WES (Blades et al. Reference Blades, Collins, Foden, Payne, Xu, Alemu, Woldetinsae, Clark and Taylor2015).

Ultramafic/mafic plutonic rocks within the WES, where little metamorphism and deformation have occurred, allow for the identification of primary structures (Braathen et al. Reference Braathen, Grenne, Selassie and Worku2001). These structures do not contradict an oceanic crust origin. However, others have suggested that there is a lack of geochemical evidence to support the presence of ophiolites in the WES, and although the ultramafic complexes are concentrated along the Baruda–Tulu Dimtu shear belt, their existence outside this zone has been considered problematic to an ophiolite suture model (Braathen et al. Reference Braathen, Grenne, Selassie and Worku2001). The alternate theory proposed by Braathen et al. (Reference Braathen, Grenne, Selassie and Worku2001) suggested that these represent solitary intrusions, which have been tectonically modified and partly aligned along the shear belt in response to penetrative D1 deformation. It has been suggested that they represent Alaskan-type, concentrically zoned intrusions, which were emplaced into an extensional arc or back-arc environment (Mogessie, Belete & Hoinkes, Reference Mogessie, Belete and Hoinkes2000; Braathen et al. Reference Braathen, Grenne, Selassie and Worku2001; Grenne et al. Reference Grenne, Pedersen, Bjerkgård, Braathen, Selassie and Worku2003). These small elliptical bodies are common in the northern parts of the Arabian–Nubian Shield in the Eastern Desert of Egypt: Gabbro Akarem (Helmy & El Mahallawi, Reference Helmy and El Mahallawi2003; El-Rahman et al. Reference El-Rahman, Helmy, Shibata, Yoshikawa, Arai and Tamura2012), Genina Gharbia (Helmy et al. Reference Helmy, El-Rahman, Yoshikawa, Shibata, Arai, Tamura and Kagami2014), Abu Hamamid (Helmy et al. Reference Helmy, Yoshikawa, Shibata, Arai and Kagami2015) and Dahanib (Khedr & Arai, Reference Khedr and Arai2016).

4. Analytical methods

4.a. Microprobe mineral chemistry

The chemical compositions of the chrome spinels and olivines were determined using a Cameca SX51 Electron Microprobe at Adelaide Microscopy, the University of Adelaide. Spot analyses were conducted using a beam current of 20 nA and an accelerating voltage of 15 kV, with a defocused beam of 5 microns. Representative spinel and olivine are given in Table 1. All analyses and calculations are in online Supplementary Material Tables S1–4 available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo. Calibration was made based on natural and synthetic mineral standards.

Table 1. Representative chrome spinel and co-existing olivine microprobe analyses from ultramafic rocks of the Western Ethiopian Shield

5. Results

5.a. Petrography of the ultramafic samples

The petrography of the ultramafic rocks from the WES was investigated using an optical microscope, with emphasis on the occurrence, relationships and textures of spinel (Fig. 3). The geology of Gimbi and accompanying geological map compiled by Alemu & Abebe (Reference Alemu and Abebe2000) was used to understand the geology of the area. Map features of each of the complexes are shown in Figure 2 and were taken and adapted from an unpublished Ph.D. thesis (M. Jackson, unpub. Ph.D. thesis, Cardiff Univ., 2006).

Figure 3. Thin-sections of the ultramafic samples collected from the Western Ethiopian Shield (WES). (a, b) Sections from Daleti Quarry (E13-11); (a) is plane polar and (b) is in cross-polar. The primary mineralogy consists of olivine and Cr spinel. Extensive alteration: serpentine forms a mesh texture, resembling a fisherman's net, where the rim of the net is serpentine and the empty space in the mesh centre is occupied by fresh (relict) olivine. (c, d) Representative section of Abshala Melange and Tulu Dimtu Hill (E13-19, 20, 22 and 26); (c) is plane polar and (d) is in cross-polar. These samples have been more extensively altered with no relict/fresh olivines seen within this sample. The dunite contains chrome spinels with euhedral to subhedral shapes. All silicate minerals within the sample have been altered by serpentine. (e, f) Sample was taken from Yubdo (E13-10); (e) is plane polar and (f) is in cross-polar. The spinels are subhedral spinels and occur in serpentine-filled cracks. The olivines are fresh with little evidence for serpentinization other than in the cracks between these minerals.

5.a.1. Daleti Quarry E13-11 (09° 09′ 56.4″ N, 35° 37′ 30.0″ E)

Daleti covers an area of c. 5 km2 and primarily consists of dunite, with no discernible concentric outcrop patterns (Fig. 2). Sample E13-11 was collected from the Daleti Quarry, where the exposure is dominated by serpentinized dunite, with minor intercalations of talc schist and talc carbonate schist. The chrome spinel and magnetite are seen disseminated throughout the outcrop, with pervasive serpentinite veins cross-cutting the main lithology.

The Daleti dunite (Fig. 3a, b) shows extensive alteration to mesh-textured serpentine, with isolated fresh remnants of the original olivine grains. The primary mineralogy consists of olivine and Cr spinel. The chrome spinels occur as large 1–2 mm euhedral to subhedral grains (Fig. 3a, b).

5.a.2. Abshala Melange E14-19 (09° 23′ 16 .0″ N, 035° 43′ 15.9″ E)

The Abshala Mélange is internally complex, containing rocks of disparate histories (Alemu & Abebe, Reference Alemu and Abebe2000). It comprises tectonically mixed rock types: metabasalt/amphibolite, peridotite and quartzite/chert. This is interpreted to represent an accretionary melange at a convergent plate boundary/subduction zone.

Sample E14-19 was taken from a serpentinized peridotite clast. This serpentinized sample contains euhedral and anhedral chrome spinel grains (~ 1 mm) and no preserved relict olivine (Fig. 3c, d).

5.a.3. Doro Dimtu E13-20, 22 and 26 (9° 27′ 60.9″ N, 35° 44′ 19.8″ E)

There are three main intrusions in the Tulu Dimtu area: the main intrusion, sheared ultramafic rocks and lensoid ultramafic rocks. The lithologies of the main intrusion include dunite, olivine-clinopyroxenite and clinopyroxenite. The sheared ultramafic rocks are highly deformed and are found at the edge of the main intrusion. The map features show that there are multiple shear zones and these are associated with talc and chlorite with one of the shear zones enveloping quartzite bodies.

The samples were collected from a previously mapped dunite body (M. Jackson, unpub. Ph.D. thesis, Cardiff Univ., 2006). However, in thin-section they are extensively altered with no relict/fresh olivine. They contain chrome spinels (0.2–2 mm) with euhedral to subhedral shapes. All silicate minerals within the sample have been replaced by serpentine. In some cases the chrome spinel grains have been affected by alteration shown by ferrichromite rims (Fig. 4). Also, in some cases spinel crystals preserve a pull-apart texture.

Figure 4. Elemental maps for a representative chrome spinel grain at Tulu Dimtu Hill. (a) The chromium concentration across the given grain shows lower concentrations at the rim. (b) Fe concentrations showing magnetite (high Fe) rims surrounding a chromite core (low Fe). (c) Al concentration showing moderately high homogeneous concentrations across the grain. (d) Mg concentrations across the grain; relatively low concentrations. Rims show very low concentrations.

5.a.4. Yubdo E14-10 (8° 57′ 37.4″ N, 35° 27′ 18.2″ E)

The Yubdo body (Fig. 2) is zoned with dunite at its core, surrounded by pyroxenite and hornblende-clinopyroxenite. This elliptical outcrop, 30 km2 in area, preserves fresh rock under the alteration crust. These features are characteristic features of Alaskan-type intrusions, where orthopyroxene and plagioclase are extremely rare; in Yubdo they are not seen. Yubdo shows a ‘birbirite’ alteration cap over the dunites, which consists essentially of secondary silicates and limonite, and is derived from the dunites through alteration and concentration (Molly, Reference Molly1959).

In thin-section subhedral spinels (1–2 mm) occur in serpentine-filled cracks between fresh olivine and pyroxene. Although, they do not form nests or schlieran of chromite, such as are found in Alaskan-type intrusions in the Urals (Molly, Reference Molly1959). In comparison to other ultramafic outcrops in the WES, Yubdo has not experienced the same alteration; the olivines are fresh with little evidence for serpentinization other than in the cracks between these minerals (Fig. 3e, f).

5.b. Chrome spinel and olivine composition

Chromite and olivine are the only minerals from the original ultramafic rock that routinely retain their original igneous composition. Electron microprobe analyses have been undertaken on chrome spinels from ultramafic rocks at Daleti, the Abshala Melange, Yubdo and Doro Dimtu (Fig. 1). Representative analyses of chrome spinel and olivine are listed in Table 1 (full dataset in online Supplementary Material Tables S1 and S2 available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo). The Barnes & Roeder (Reference Barnes and Roeder2001) database, comprising more than 26 000 analyses of spinels from igneous and meta-igneous rocks, is used here to define and differentiate compositional fields for spinels for various tectonic settings and magma compositions. Data collected previously in the area, in an unpublished Ph.D. thesis, have also been used (M. Jackson, unpub. Ph.D. thesis, Cardiff Univ., 2006).

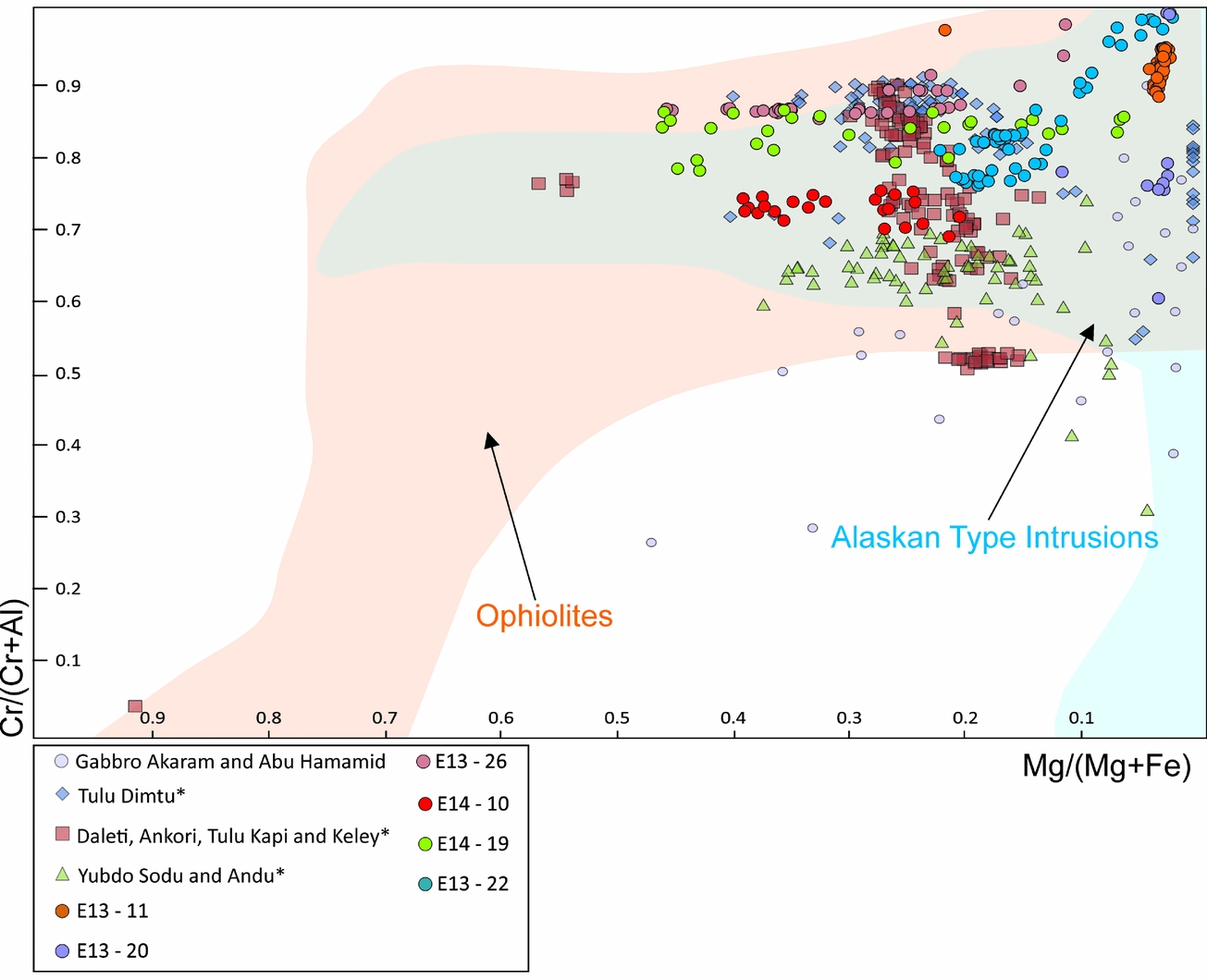

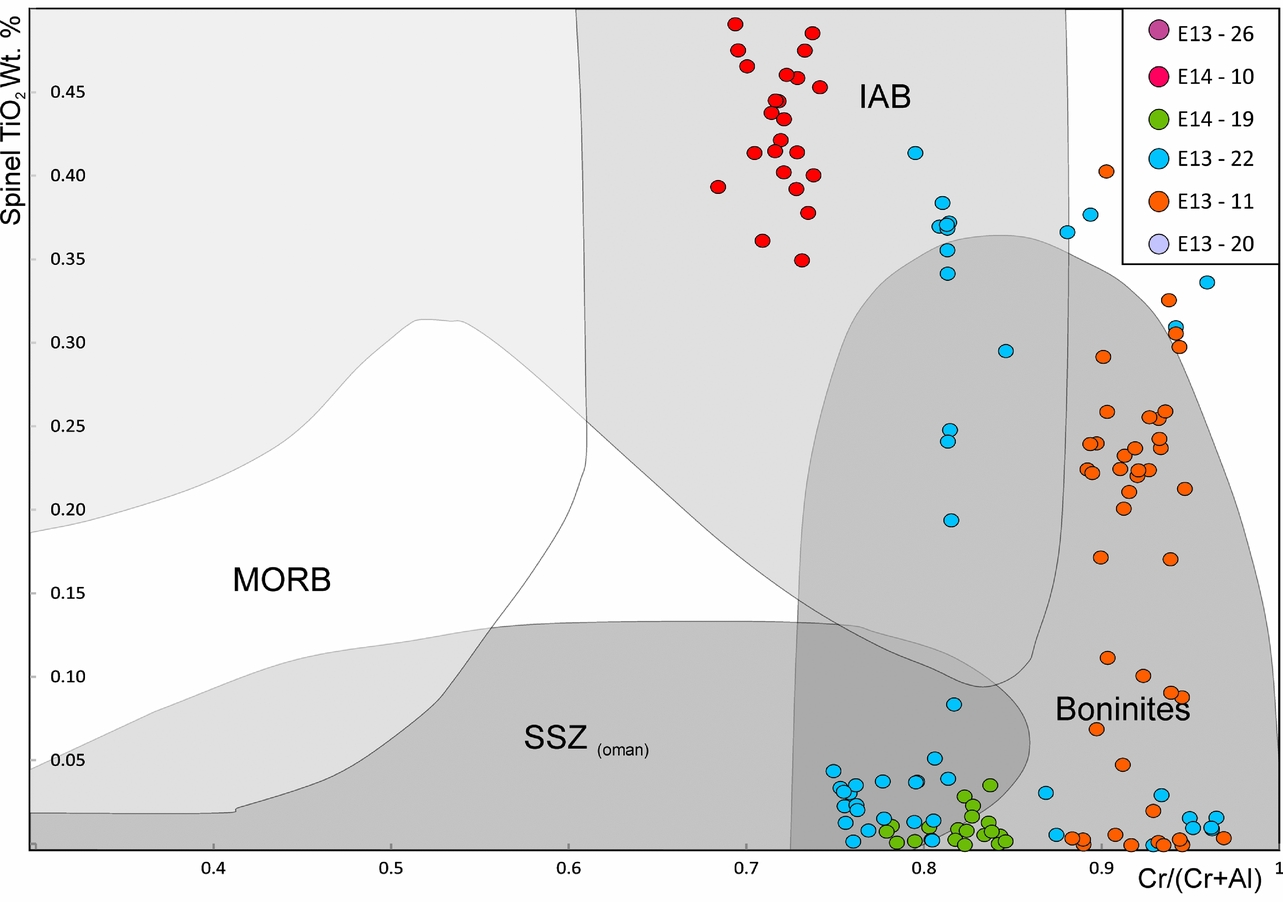

The chrome spinels are characterized by generally high Cr2O3, but with a large range (30.04–68.76 wt %), low TiO2 content (0.01–0.51) and Cr# (molar Cr3+/Cr3+ + Al3+) in the range of 0.607 to 0.99. The average Cr# is 0.86 (Fig. 5 and online Supplementary Material Table S1 available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo) and they have Mg# (Mg# = Mg2+/Mg2+ + Fe2+) ranging from 0.22 to 0.46 (Fig. 5). These data overlap both the Alaskan-type intrusions and oceanic ophiolite fields (Barnes & Roeder, Reference Barnes and Roeder2001). In many samples the Cr-rich chromite is rimmed by Fe-rich spinel (Fig. 4). These Fe-rich rims are probably a result of Fe replacement during serpentinization of olivine (Barnes, Reference Barnes2000). On the Cr–Al–Fe3+ ternary diagram, the chrome spinels are clustered at relatively low-Fe3+, high-Cr contents, sitting on the Cr–Fe join indicating chromite–magnetite solid solution (Fig. 6) with low spinel (ss) substitution. Chromite is less susceptible to trapped liquid reaction effects when the proportion of chromite to liquid in the rock is high (Barnes & Roeder, Reference Barnes and Roeder2001). As already observed, the presence of these populations of high-Cr# lower-Al2O3, low-TiO2 spinels (Figs 5–7) are indicative of precipitation from primitive subduction-related arc magmas including boninites (Barnes & Roeder, Reference Barnes and Roeder2001).

Figure 5. Cr# (Cr/Cr + Al) v. Mg# (Mg/Mg + Fe2+) from chrome spinels analysed within the WES (Dick & Bullen, Reference Dick and Bullen1984). Other data from the ultramafic rocks in the WES (*) were taken from an unpublished Ph.D. thesis (M. Jackson, unpub. Ph.D. thesis, Cardiff Univ., 2006). Gabbro Akarem and Abu Hamamid Alaskan-type intrusions, Egypt used as a comparison for other Alaskan-type intrusions in the Arabian–Nubian Shield (Farahat & Helmy, Reference Farahat and Helmy2006). Data predominately plots in a similar field to Alaskan-type intrusions. Alteration is evident with a decrease in Cr# seen in E13-11 and E13-20.

Figure 6. Trivalent cation ratios of chrome spinel in ultramafic and related rocks from previously published ophiolites and Alaskan-type intrusions (Barnes & Roeder, Reference Barnes and Roeder2001). Samples E13-11 and E13-20 taken from Daleti and Tulu Dimtu display an Fe3+ enrichment most likely due to alteration of the chrome spinels, showing a similar pattern to layered intrusions and Alaskan-type intrusions.

Figure 7. TiO2 content versus Cr# in spinel from ultramafic rocks of the Western Ethiopian Shield. Spinel compositions of MORB, island-arc basalts (IAB) and boninites are from Arai (Reference Arai1992), Kelemen et al. (Reference Kelemen, Whitehead, Aharonov and Jordahl1995) and Dick & Natland (Reference Dick, Natland, Mével, Gillis, Allan and Meyer1996). Supra-subduction zone (SSZ) peridotites from Oman were taken from Arai et al. (Reference Arai, Shimizu, Ismail and Ahmed2006). Chrome spinels are seen in a number of fields but predominately in boninite, SSZ (Oman) and IAB.

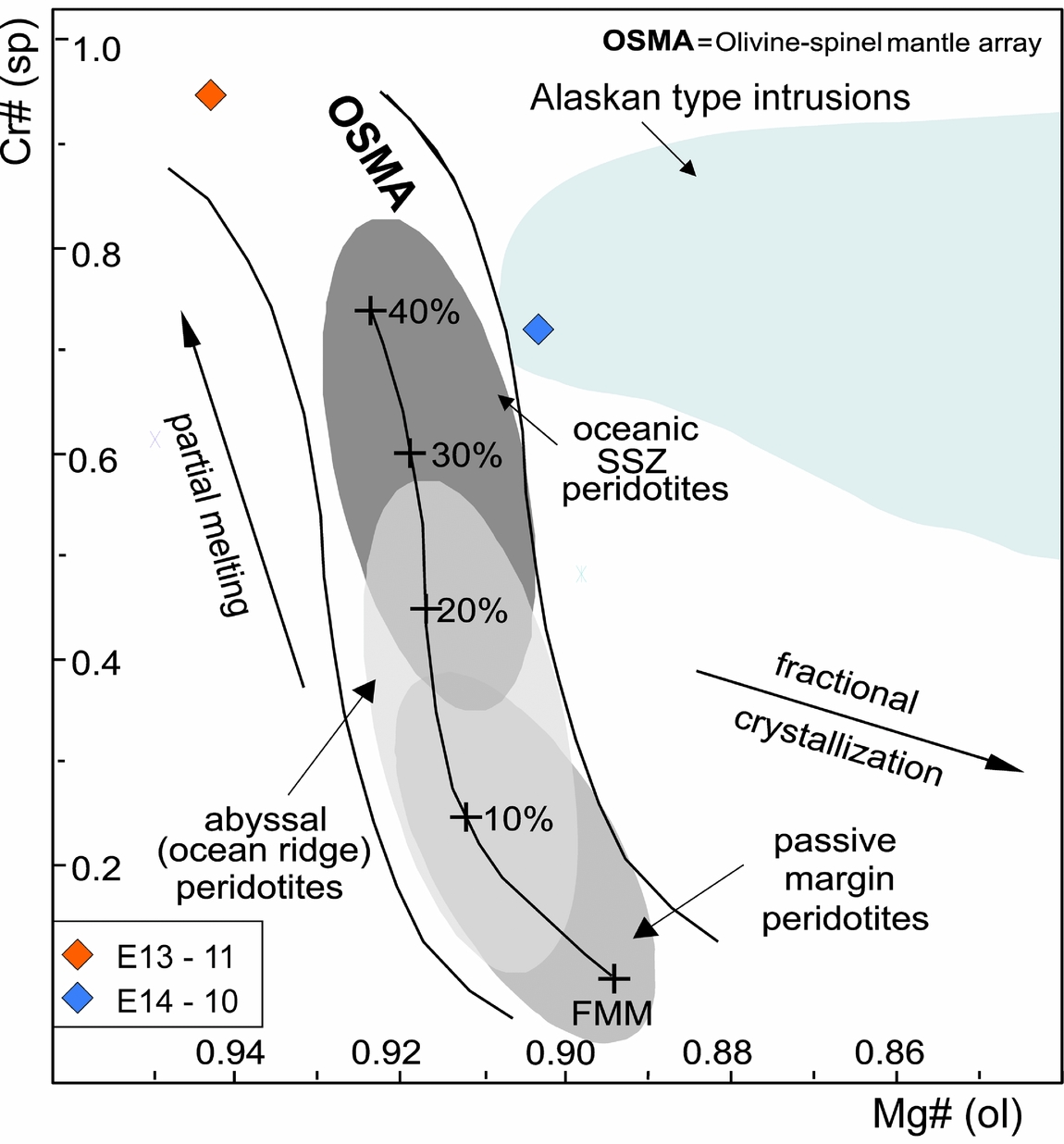

Olivine is the most common primary mineral in ultramafic terranes and can be used in association with chrome spinel as a petrogenetic indicator (Dick & Bullen, Reference Dick and Bullen1984). Fresh olivine is only observed from the bodies at Yubdo (E14-10) and Daleti (E13-11). Olivine from the Yubdo body is of uniform composition (Fo90, online Supplementary Material Table S2 available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo) with CaO (wt %) and MnO (wt %) values between 0.23 and 0.12, and 0.18 and 0.07, respectively. These CaO and MnO values are like those from olivines of the Alaskan-type complexes (Irvine, Reference Irvine1974; Snoke, Quick & Bowman, Reference Snoke, Quick and Bowman1981). Also, like Alaskan intrusions, where cumulate olivine is formed during early-stage fractionation of primitive mafic magmas, these olivines have an average of 0.11 wt % NiO (895 ppm), significantly lower than refractory mantle peridotite olivine. By contrast the olivine from the Daleti complex is much more magnesian, with a mean composition of Fo93.5. Also compared with the Yubdo olivines, these are MnO- and particularly CaO-poor (CaO average = 0.007 wt %) and have very high (mantle-like) Ni concentrations (2990 ppm average) (Bodinier & Godard, Reference Bodinier, Godard and Carlson2003).

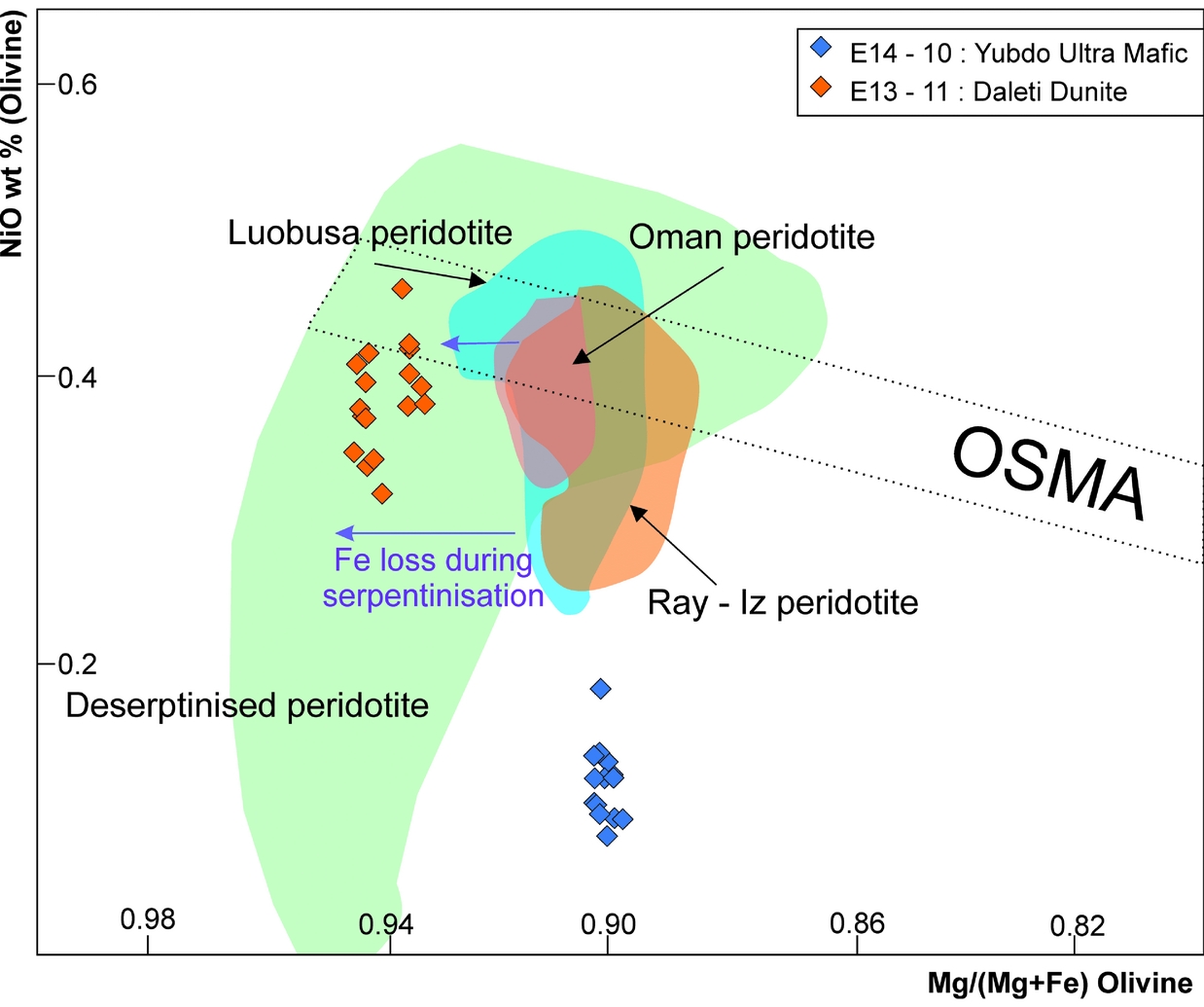

The olivine–spinel mantle array (OSMA) was proposed by Arai & Takahashi (Reference Arai and Takahashi1987) and Arai (Reference Arai1992) as a residual mantle peridotite trend, defined by the forsterite content of olivine and the Cr# of spinel. The sample from Daleti plots above the OSMA (Fig. 8), with high Cr# and Fo. Sub-solidus formation of another aluminous phase could be responsible for this shift in the spinel chemistry (Arai, Reference Arai1994), or is possibly the result of metasomatic or metamorphic alteration. Samples from Yubdo (Fig. 8) plot on the edge of, or to the right of, the OSMA (Arai, Reference Arai1994). Arai (Reference Arai1994) argued that the OSMA is a residual peridotite array and that cumulates on this plot trend to the right. If this is the case, Yubdo can be inferred to be of cumulate origin, plotting towards the most primitive end of the Alaskan cumulate field (Fig. 8). The relatively low NiO content differentiates these from other mid-ocean ridge basalt (MORB)-related peridotites (Fig. 9). The high Cr# and Fo values (Figs 8, 9) of these peridotites are consistent with a supra-subduction zone origin (Dick & Bullen, Reference Dick and Bullen1984; Bonatti & Michael, Reference Bonatti and Michael1989). Where the Ethiopian data fall in the fields for boninites (Fig. 7), this suggests the rocks have been formed from a hydrous melt characteristic of subduction environments (Beccaluva & Serri, Reference Beccaluva and Serri1988).

Figure 8. Average Mg# of olivine and Cr# of spinel in ultramafic rocks of the WES. The olivine–spinel mantle array (OSMA) is shown by the two black lines, with a supra-subduction field (top grey ellipse), abyssal peridotites (middle grey ellipse) and passive margin peridotites (bottom light grey) (Dick & Bullen, Reference Dick and Bullen1984; Dick, Reference Dick1989; Arai, Reference Arai1994; Pearce et al. Reference Pearce, Barker, Edwards, Parkinson and Leat2000) and boninites (Metcalf & Shervais, Reference Metcalf, Shervais, Wright and Shervais2008). Pressure curves give approximate values on the depth of melting of the peridotites. 5 and 10 kbar curves are from Sobolev & Batanova (Reference Sobolev and Batanova1995) and 15 kbar from Jaques & Green (Reference Jaques and Green1980). E14-10 plots to the right of the OSMA suggesting that it has a cumulate origin (Arai, Reference Arai1994). FMM – fertile MORB mantle.

Figure 9. NiO v. Fo relationship of olivine in chrome spinels between Yubdo and Daleti. Olivine mantle array is the field for olivines in residual mantle peridotites (Takahashi & Ito, Reference Takahashi, Ito, Manghnani and Syono1987). Fields were taken from Arai & Miura (Reference Arai and Miura2016). Olivines from peridotites are mostly high in Fo but low in NiO. The relatively low NiO content differentiates these from other MORB-related peridotites.

5.c. Oxygen fugacity of the Yubdo and Daleti peridotites

The oxygen fugacity of mafic and ultramafic rocks is generally calculated using the olivine–spinel equilibria calibrated by Ballhaus, Berry & Green (Reference Ballhaus, Berry and Green1991) and Ballhaus, Berry & Green (Reference Ballhaus, Berry and Green1994), who also standardized the olivine–spinel FeMg-1 exchange thermometer. Based on these calibrations, peridotite from abyssal- and depleted MORB mantle (DMM) (MORB-source) mantle has been shown to have Δlog fO2 (FMQ) values in the range 0 to −2.5, whereas supra-subduction zone lithospheric mantle peridotite has values in the range +0.5 to +2 (Parkinson & Arculus, Reference Parkinson and Arculus1999). Basalts from different mantle sources also reflect these oxidation differences. Evans, Elburg & Kamenetsky (Reference Evans, Elburg and Kamenetsky2012) also quoted that MORB tends to have Δlog fO2 (FMQ) values close to 0 (Aldanmaz et al. Reference Aldanmaz, Schmidt, Gourgaud and Meisel2009), while subduction magmas range from +0.5 to +3.5.

The results of Fe–Mg exchange thermometry between olivine and chromite using the corrected equation from Ballhaus, Berry & Green (Reference Ballhaus, Berry and Green1991) and Ballhaus, Berry & Green (Reference Ballhaus, Berry and Green1994) gives an average temperature of 1154 °C and 678 °C for Yubdo (E14-10) and Daleti (E13-11), respectively (online Supplementary Material Table S3 available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo). Arai et al. (Reference Arai, Kida, Abe and Yurimoto2001) have recorded the average temperatures for spinels in ophiolite or abyssal peridotites as 681 ± 44 °C, whereas, by comparison, Yubdo exhibits higher temperatures than expected for arc-related peridotites, and those from Daleti sit within error of previously published ophiolite data. The Fo contents of olivine co-existing with chromite varies from 0.90 (Yubdo, E14-10) to 0.94 (Daleti, E13-11) and increases with decreasing temperature, indicating that the more magnesian olivines may have lost iron as they re-equilibrated during cooling and probably do not represent primary compositions (Rollinson & Adetunji, Reference Rollinson and Adetunji2015b). These high equilibrium temperatures, especially in equilibration with Fo90 olivines, further confirm that the chrome spinel compositions for Yubdo are relics of the original igneous cooling stage, and have not been reset during subsequent metamorphism or alteration. However, the relatively low temperatures of spinels in the case of equilibration with Fo94 olivines, which is apparently below the expected liquidus temperature of mantle peridotites, indicates sub-solidus re-equilibration (Mg–Fe exchange) between chrome spinel and olivine (Roeder & Campbell, Reference Roeder and Campbell1985; Scowen, Roeder & Helz, Reference Scowen, Roeder and Helz1991; Farahat, Reference Farahat2008). The Δlog fO2 (FMQ) values (Table 1 and online Supplementary Material Table S4 available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo) for the Yubdo (E14-10) samples average fO2 (FMQ) +3.03 (Fig. 10a). These are significantly more oxidized than abyssal peridotite values and much more like typical arc-related peridotites (Parkinson & Arculus, Reference Parkinson and Arculus1999; Arai & Ishimaru, Reference Arai and Ishimaru2008). The Yubdo spinels are oxidized relative to oceanic ophiolites and have similar values to other Alaskan-type intrusions (Fig. 10) (Himmelberg & Loney, Reference Himmelberg and Loney1995; Parkinson & Arculus, Reference Parkinson and Arculus1999; Garuti et al. Reference Garuti, Pushkarev, Zaccarini, Cabella and Anikina2003; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Suzuki, Tian, Jahn and Ireland2009). The spinels from Daleti (E13-11) have a Δlog fO2 (FMQ) average value of +4.8 (Table 1 and online Supplementary Table S4 available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo); this is unusually high, further supporting that these may have been effected by possible metasomatic (Mellini, Rumori & Viti, Reference Mellini, Rumori and Viti2005; Frost & Beard, Reference Frost and Beard2007; Iyer et al. Reference Iyer, Austrheim, John and Jamtveit2008) overprint by subsequent serpentinization.

Figure 10. The plots show that interaction trends involve increases in both oxygen fugacity and Cr# of spinel. The oxygen fugacity was calculated using the method outlined in Ballhaus, Berry & Green (Reference Ballhaus, Berry and Green1991, Reference Ballhaus, Berry and Green1994). Fe–Mg exchange thermometry and a nominal 1 GPa was used as the best representation of pressure and temperature (Ballhaus, Berry & Green, Reference Ballhaus, Berry and Green1991). (a) Plot of Δ fO2 (FMQ) v. temperature. Δ fO2 (FMQ) refers to the deviation from the FMQ buffer in log units. The sample collected from Yubdo lies in the range of FMQ +3.03. Sample E13-11 from Daleti has a Δlog fO2 (FMQ) average value of +4.8. Examples of both arc peridotites and Alaskan-type intrusions have been plotted showing that Yubdo is oxidized relative to ophiolites, and seems to be similar to the Alaskan-type intrusions (Parkinson & Arculus, Reference Parkinson and Arculus1999; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Suzuki, Tian, Jahn and Ireland2009). (b) Δ fO2 (FMQ) values are plotted against spinel Cr# (molar Cr/(Cr + Al)) (Parkinson & Arculus, Reference Parkinson and Arculus1999; Garuti, Pushkarev & Zaccarini, Reference Garuti, Pushkarev and Zaccarini2002; Garuti et al. Reference Garuti, Pushkarev, Zaccarini, Cabella and Anikina2003; Rollinson, Reference Rollinson2008; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Suzuki, Tian, Jahn and Ireland2009; Khedr & Arai, Reference Khedr and Arai2013; Rollinson & Adetunji, Reference Rollinson and Adetunji2015a,Reference Rollinson and Adetunjib). Yubdo and Daleti have high Cr# and a highly oxidized nature, typical of supra-subduction zone settings. Yubdo (E14-10) plots close to the field of Alaskan-type intrusions.

Samples in which fresh olivine and spinel coexist and thus permit the calculation of the ΔfO2 (FMQ) are very rare. In the dataset there are single samples from each of the interpreted Alaskan (Yubdo) and ophiolite-type (Daleti) peridotites and both yield highly oxidized values (ΔfO2 (FMQ) > 3), significantly more oxidized than DMM MORB-source mantle. The high Cr# and highly oxidized nature of both these samples are more characteristic of supra-subduction zone settings, and Yubdo, in particular, tends to have values closer to those of known Alaskan-type intrusions (Fig. 10a, b).

5.d. How do the spinels compare to those elsewhere in the East African Orogen?

The Neoproterozoic ophiolites and associated ultramafic–mafic intrusions in the Eastern Desert of Egypt have been suggested to be 890–690 Ma (Stern et al. Reference Stern, Johnson, Kröner and Yibas2004; Azer & Stern, Reference Azer and Stern2007; Abdel-Karim et al. Reference Abdel-Karim, Ali, Helmy and El-Shafei2016). The northern Arabian–Nubian Shield is made up of both ophiolitic mafic–ultramafic rocks (Stern et al. Reference Stern, Johnson, Kröner and Yibas2004; Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2013; Khedr & Arai, Reference Khedr and Arai2016) and Alaskan-type ultramafic–mafic rocks (Helmy & Mogessie, Reference Helmy and Mogessie2001; Helmy & El Mahallawi, Reference Helmy and El Mahallawi2003; Farahat & Helmy, Reference Farahat and Helmy2006; El-Rahman et al. Reference El-Rahman, Helmy, Shibata, Yoshikawa, Arai and Tamura2012; Khedr & Arai, Reference Khedr and Arai2016).

Ophiolitic complexes are usually aligned along the NW-trending Najd shear zones in the northern Arabian–Nubian Shield or along N–S-trending shear zones, though these interpretations are complicated by variably dismembered and deformed outcrops. It has generally been recognized that these are generated in supra-subduction zones (Bakor, Gass & Neary, Reference Bakor, Gass and Neary1976; Pallister et al. Reference Pallister, Stacey, Fischer and Premo1988; Stern et al. Reference Stern, Johnson, Kröner and Yibas2004). Within northern parts of the Arabian–Nubian Shield (Egyptian Desert) most authors have inferred a back-arc setting for the Egyptian ophiolites (El Bahariya & Abd El-Wahed, Reference El Bahariya and Abd El-Wahed2003; Farahat et al. Reference Farahat, El Mahalawi, Hoinkes and Abdel Aal2004; Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2013); sea floor spreading and production of ophiolites can also occur in a fore-arc, during early stages of subduction initiation, though this idea is relatively new (Stern et al. Reference Stern, Johnson, Kröner and Yibas2004; Azer & Stern, Reference Azer and Stern2007). Stern et al. (Reference Stern, Johnson, Kröner and Yibas2004) suggested that the majority of the ophiolitic ultramafic rocks are harzburgitic, containing magnesian-rich olivines and spinels with Cr# > 0.6 (Azer & Stern, Reference Azer and Stern2007). Similar spinel chemistry is also seen in the ophiolites in NW Sudan (Cr# 0.69–0.84), though these have been thought to not be a part of the Arabian–Nubian Shield (Rahman et al. Reference Rahman, Harms, Schandelmeier, Franz, Darbyshire, Horn and Muller–Sohnius1990). The Onib ophiolite shows bimodal chromite populations both Cr-rich (Cr# 0.62–0.65) and Al-rich (~ 64 %); the chemistry of these is very different to those seen in the WES. Alaskan-type intrusions in the Eastern Desert typically have Cr# ranges between 0.31 and 0.90 and Fe3+# between 75 and 55. The spinels are characteristically Al–Mg poor, similar to those seen in Yubdo (Helmy & Mogessie, Reference Helmy and Mogessie2001; Helmy & El Mahallawi, Reference Helmy and El Mahallawi2003; Farahat & Helmy, Reference Farahat and Helmy2006; El-Rahman et al. Reference El-Rahman, Helmy, Shibata, Yoshikawa, Arai and Tamura2012; Khedr & Arai, Reference Khedr and Arai2016).

The olivines in the WES (Fo90–94) have higher average Fo contents than the olivines in the Abu Hamamid (Fo74–81), Gabbro Akarem (Fo69–87) and Genina Gharbia (Fo80–86) Alaskan-type complexes, but are comparable to those of the Dahanib Complex (Fo83–92) (Helmy & Mogessie, Reference Helmy and Mogessie2001; Farahat & Helmy, Reference Farahat and Helmy2006; Helmy et al. Reference Helmy, El-Rahman, Yoshikawa, Shibata, Arai, Tamura and Kagami2014; Abdel-Karim et al. Reference Abdel-Karim, Ali, Helmy and El-Shafei2016). Forsterite contents from olivines in rocks from interpreted ophiolites (Abu Daher area: Khudeir, Reference Khudeir1995; Um Khariga: Khalil & Azer, Reference Khalil and Azer2007) have a wide variation and range from Fo(91.3–93.0). These higher Fo values, like the ones seen in Daleti, are much more like peridotites found at Cape Vogel in Papua New Guinea (Kamenetsky et al. Reference Kamenetsky, Sobolev, Eggins, Crawford and Arculus2002). Similar compositions also occur among the dunites and harzburgites from the Izu–Bonin–Mariana fore-arc (Ishii, Reference Ishii1992; Yamamoto et al. Reference Yamamoto, Masutani, Nakamura and Ishii1992; Parkinson & Pearce, Reference Parkinson and Pearce1998). The olivines from the Onib Complex, Sudan have lower olivine forsterite contents of Fo(88) and do not seem to overlap with olivine compositions from the WES (Hussein, Kröner & Reischmann, Reference Hussein, Kröner and Reischmann2004).

5.e. Petrogenesis of the ultramafic rocks of the WES

The ultramafic rocks in the WES are generally comprised of dunite, olivine-clinopyroxenite and clinopyroxenites in association with metasediments, whose protoliths are interpreted to have a marine origin, including pelagic sediments, cherts and quartzites that have all been metamorphosed to upper-greenschist/epidote–amphibolite facies (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Ayalew, Mogessie, Kruger and Poujol2004). Most of these ultramafic bodies show disparate histories and have been serpentinized and therefore the identification of primary structures and features make it difficult to determine their origin (Daleti, Abashala Melange and Tulu Dimtu). The ultramafic complexes are concentrated generally along the Baruda–Tulu Dimtu shear belt (suture zone); however, their occurrence outside this zone has been suggested to be problematic for the ophiolite-decorated suture model (Braathen et al. Reference Braathen, Grenne, Selassie and Worku2001). In some instances, the ultramafic rocks are enclosed in the Mora metasediments and this could suggest that they represent solitary intrusions that have been modified and aligned along the shear belt in response to deformation, rather than being fragments of oceanic crust caught up in a suture zone (Braathen et al. Reference Braathen, Grenne, Selassie and Worku2001). However, the Yubdo ultramafic body does not seem to show the same disparate history or alteration (Fig. 3) and has been shown to have concentric zoning typical of Alaskan-type intrusions (Fig. 2), with dunites at the core, surrounded by pyroxenite and hornblende-clinopyroxenite, similar to the Neoproterozoic Alaskan-type complexes in Egypt (Helmy & Mogessie, Reference Helmy and Mogessie2001; Helmy & El Mahallawi, Reference Helmy and El Mahallawi2003; Farahat & Helmy, Reference Farahat and Helmy2006; El-Rahman et al. Reference El-Rahman, Helmy, Shibata, Yoshikawa, Arai and Tamura2012; Khedr & Arai, Reference Khedr and Arai2016).

The chrome spinels from the WES are characterized by generally high but varied Cr2O3 (30.04–68.76 wt %), low TiO2 (0.01–0.51), Cr# in the range of 0.607 to 0.99, and Mg# ranging from 0.22 to 0.46 (Fig. 5). These data fall in overlapping fields of known Alaskan-type intrusions and ophiolites (Barnes & Roeder, Reference Barnes and Roeder2001); however, they clearly differentiate Daleti (E13-11). In general these spinels have high Cr# lower Al2O3 and low TiO2 (Figs 5–7), and these plots show that these are characteristic of supra-subduction peridotites formed from melting of hydrated crust (Barnes & Roeder, Reference Barnes and Roeder2001). The samples (Daleti and Tulu Dimtu) demonstrate clear alteration trends (Figs 6, 7), sitting along the Cr3+ and Fe3+ join. The spinel chemistry reported here supports the subduction-related (island-arc) environment, from sources that are enriched in the slab component in the presence of a hydrous melt. The spinels have a boninitic affinity (Fig. 7), defining a field of high-Cr# and low-TiO2 lavas, formed in a supra-subduction zone (Barnes & Roeder, Reference Barnes and Roeder2001) as a result of the modification of mantle compositions from the percolating of melts or fluids within a subduction setting (Barnes & Roeder, Reference Barnes and Roeder2001; Arai et al. Reference Arai, Shimizu, Ismail and Ahmed2006).

Fresh olivine chemistry could only be obtained from Yubdo (E14-10) and Daleti (E13-11), with forsterite contents ranging between Fo90 and Fo93.5. There is a clear differentiation in olivine chemistry: the Daleti olivine is much more magnesian, MnO- and particularly CaO-poor and has very high Ni concentrations. Arai (Reference Arai1994) defines the ‘OSMA’ array as a reflection of the composition of residual, refractory peridotite, while spinels that trend to the right of the array are typically cumulate. If this is the case, the Yubdo samples analysed here can be inferred to be of cumulate origin. The position of Yubdo in the mantle array shows that the ultramafic rocks of the WES carry a supra-subduction zone signature and sit within the known field of Alaskan-type intrusions (Fig. 8). The oxygen fugacity of the magma producing the peridotites (FMQ +3.03) is significantly higher than previously reported MORB values; however, it falls within the arc range. These values are comparable to oxygen fugacity values for peridotites from the Dahanib Complex with Δlog ƒO2 varying from 2.4 to 3.3 (Khedr & Arai, Reference Khedr and Arai2016). Figure 10a shows that fO2 (FMQ) of ophiolites and arc-related peridotites, even from supra-subduction zone environments, are more reduced that the values obtained from the Yubdo peridotite (Parkinson & Arculus, Reference Parkinson and Arculus1999). However, it should be noted that metasomatic (Mellini, Rumori & Viti, Reference Mellini, Rumori and Viti2005; Frost & Beard, Reference Frost and Beard2007; Iyer et al. Reference Iyer, Austrheim, John and Jamtveit2008) or metamorphic overprinting (Springer, Reference Springer1974; Frost, Reference Frost1975; Pinsent & Hirst, Reference Pinsent and Hirst1977; Kimball, Reference Kimball1990) may cause an enrichment of iron in spinel and may also increase the Fe3+/ΔFe ratio leading to the calculation of elevated oxygen fugacity and can be used to explain the anomalously high values for Daleti (Δlog ƒO2 +4). Metamorphosed chromite is substantially more iron rich than igneous precursors, as a result of the Mg–Fe exchange with silicates and carbonates. The relative proportions of the trivalent cations Cr3+, Al3+ and Fe3+ are not greatly modified, although Fe3+ depletion occurs during the talc carbonate alteration at low temperatures. Metamorphism can have a substantial effect on the Mg# tending to lower values (Daleti, Fig. 5), as a consequence of the exchange between Mg2+ and Fe2+ between chromite and co-existing silicates. The equilibrium constant for the reaction between Mg(spinel) and Fe2+(olivine) is dependent on temperature, changing in a way that the olivine becomes more Mg rich and the spinel more Fe rich with falling temperature (Daleti, Fig. 4, 5). This can explain the uncharacteristic values for Daleti and why it plots to the left of the OSMA (Fig. 8), with elevated oxygen fugacity (Fig. 10a, b).

Previously published geochemical data from Yubdo show relatively high values of Pt, Pd and Rh, characteristic of Alaskan-type intrusions (Belete et al. Reference Belete, Mogessie, Hoinkes and Ettinger2000; Mogessie, Belete & Hoinkes, Reference Mogessie, Belete and Hoinkes2000). Together with the concentric nature of this body and chemistry of the spinels (Figs 5–7), it is interpreted that Yubdo does represent a solitary intrusion, comparable to other intrusions in the Arabian–Nubian Shield. However, samples from Tulu Dimtu, Daleti and Yubdo have chrome spinel chemistry with considerably lower TiO2 than typical Alaskan-type intrusions and therefore alternate theories still exist for the origin of the Daleti and Tulu Dimtu bodies (online Supplementary Material Table S1 available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo) (Dick & Bullen, Reference Dick and Bullen1984; Himmelberg & Loney, Reference Himmelberg and Loney1995; Barnes & Roeder, Reference Barnes and Roeder2001; Helmy & Mogessie, Reference Helmy and Mogessie2001; Kamenetsky, Crawford & Meffre, Reference Kamenetsky, Crawford and Meffre2001; Helmy & El Mahallawi, Reference Helmy and El Mahallawi2003; Farahat & Helmy, Reference Farahat and Helmy2006; Proenza et al. Reference Proenza, Zaccarini, Lewis, Longo and Garuti2007). The chemical differences between the Yubdo and Daleti bodies have therefore been interpreted to suggest that the WES has examples of both solitary intrusions (Yubdo) and supra-subduction ophiolitic remnants (Daleti, Tulu Dimtu and Abshala).

5.f. Tectonic evolution of the WES

The ultramafic rocks of the WES have previously been interpreted to have represented a slice of oceanic crust, though there have been dissenting opinions (Kazmin, Reference Kazmin1976; de Wit & Aguma, Reference de Wit and Aguma1977; Abraham, Reference Abraham1989; Stern, Reference Stern1994; Alemu & Abebe, Reference Alemu and Abebe2000; Belete et al. Reference Belete, Mogessie, Hoinkes and Ettinger2000; Mogessie, Belete & Hoinkes, Reference Mogessie, Belete and Hoinkes2000; Braathen et al. Reference Braathen, Grenne, Selassie and Worku2001; Alemu & Abebe, unpub. report, Geological Survey of Ethiopia, 2002; Alemu, Reference Alemu and Asrat2004; Tadesse & Allen, Reference Tadesse and Allen2004, Reference Tadesse and Allen2005; Alemu & Abebe, Reference Alemu and Abebe2007). The parental melts to the ultramafic rocks of the WES are not typical MORB; they are more oxidized and have equilibrated at higher fO2. The range in the composition of the spinels is wide though; they have a boninitic parentage (of arc origin) and are hydrous, supporting their interaction with a subduction zone. Using all the available evidence clearly suggests that regardless of being obducted or intruded, these spinels were formed on a convergent margin, above a subduction zone. The chemistry of the spinels in Yubdo and the presence of these bodies outside of these interpreted suture zones, though no analyses have been done on these samples, suggest that these bodies are intrusions (Fig. 11) formed in a similar supra-subduction zone to those seen elsewhere in the Arabian–Nubian Shield (Helmy & Mogessie, Reference Helmy and Mogessie2001; Helmy & El Mahallawi, Reference Helmy and El Mahallawi2003; Farahat & Helmy, Reference Farahat and Helmy2006; El-Rahman et al. Reference El-Rahman, Helmy, Shibata, Yoshikawa, Arai and Tamura2012; Khedr & Arai, Reference Khedr and Arai2016), rather than far-travelled obducted remnants of the Mozambique Oceanic crust (Stern et al. Reference Stern, Johnson, Kröner and Yibas2004; Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2013; Khedr & Arai, Reference Khedr and Arai2016). However, the ultramafic rocks at Daleti and Tulu Dimtu have a refractory nature, chemically different to that of Yubdo, and have been interpreted to be oceanic crust obducted in a fore- or back-arc setting, though the geochemical differences between these settings are subtle. Fore-arc assemblages are more likely to become entrapped in orogens, in contrast to back-arc basin lithosphere, which is reconsumed by subduction following collision of the retreating fore-arc (Dilek & Flower, Reference Dilek, Flower, Dilek and Robinson2003) and therefore fore-arc settings are favoured in this model (Fig. 11) for Daleti, Tulu Dimtu and Abshala. The oldest rocks known in the area date back to ~ 850 Ma, with magmatism, metamorphism and deformation occurring until ~ 630 Ma (Blades et al. Reference Blades, Collins, Foden, Payne, Xu, Alemu, Woldetinsae, Clark and Taylor2015). These granites have been previously interpreted to have formed in an intra-oceanic setting, above a subduction zone. Post-tectonic granites are seen in the WES at ~ 574 Ma (Blades et al. Reference Blades, Collins, Foden, Payne, Xu, Alemu, Woldetinsae, Clark and Taylor2015), therefore suggesting that these ultramafic bodies were emplaced sometime before post-tectonic magmatism began. Yubdo, being a subduction-related intrusion, would have an age broadly synonymous with the oldest phase of magmatism in the area (~ 854 Ma). Neoproterozoic ophiolites and associated ultramafic–mafic intrusions in the Eastern Desert and Sudan have been suggested to be 890–690 Ma (Stern et al. Reference Stern, Johnson, Kröner and Yibas2004; Azer & Stern, Reference Azer and Stern2007; Abdel-Karim et al. Reference Abdel-Karim, Ali, Helmy and El-Shafei2016). These ages are coeval with the formation of the WES and therefore we interpret the Daleti, Tulu Dimtu and Abshala peridotites to be of a similar age. What this paper unequivocally shows is that these ultramafic bodies were emplaced in a supra-subduction zone (island-arc) environment, from sources that are enriched in the slab component in the presence of a hydrous melt, further supporting the formation of the WES in a supra-subduction environment (Berhe, Reference Berhe1990; Stern, Reference Stern1994; Braathen et al. Reference Braathen, Grenne, Selassie and Worku2001; Kebede, Koeberl & Koller, Reference Kebede, Koeberl and Koller2001; Allen & Tadesse, Reference Allen and Tadesse2003; Grenne et al. Reference Grenne, Pedersen, Bjerkgård, Braathen, Selassie and Worku2003; Stern et al. Reference Stern, Johnson, Kröner and Yibas2004; Tadesse & Allen, Reference Tadesse and Allen2004, Reference Tadesse and Allen2005; Woldemichael et al. Reference Woldemichael, Kimura, Dunkley, Tani and Ohira2010; Blades et al. Reference Blades, Collins, Foden, Payne, Xu, Alemu, Woldetinsae, Clark and Taylor2015).

Figure 11. Schematic illustration of the development of Daleti, Tulu Dimtu, Abshala and Yubdo in the Western Ethiopian Shield. Subduction and intra-oceanic arc magmatism is initiated at 854 Ma followed by deformation and further magmatism between 750 and 660 Ma. Closure of the Mozambique Ocean and amalgamation of terranes in the northern East African Orogen is completed by 520 Ma.

6. Conclusions

New chrome spinel and olivine data from the WES combined with previous data demonstrate that ultramafic rocks of Tulu Dimtu, Daleti and Yubdo are derived from a subduction-related (island-arc) environment, from sources that are enriched in the slab component in the presence of a hydrous melt.

A common feature of the WES spinels is their high Cr# (from 33 to 99), lower Mg# (0.117–0.464) and a trend towards Fe3+-rich compositions, which is a typical arc trend. The high-Cr (> 0.6) and low-Ti character of the primary spinels in peridotite and chromite suggest a supra-subduction zone environment that agrees with discrimination diagrams that show data plotting within an intrusion-related field. What the spinel chemistry highlights is that there is a difference in chemistry between the Yubdo body and the Daleti, Tulu Dimtu and Abshala Melange. This differentiation is also seen in the olivine chemistry (Yubdo Fo90 and Daleti Fo93.5) demonstrating that the Daleti olivine is much more magnesian, MnO- and particularly CaO-poor and has very high Ni concentrations. The oxygen fugacities of the peridotites from Yubdo are highly oxidized (FMQ +2.71 to +3.6) from the FMQ buffer, suggesting that these higher values are related to the parental magma composition and emplacement within an oxidized environment. These values are within the arc range and significantly greater than MORB, plotting closer to other known Alaskan-type intrusions. Together with the concentric nature of this body and chemistry of the spinels (Figs 5–7), it is interpreted that Yubdo does represent a solitary intrusion, comparable to other intrusions in the Arabian–Nubian Shield (particularly the Dahanib Alaskan-type intrusion).

The oldest rocks known in the area date back to c. 850 Ma. There are three broad pre-/syntectonic deformation and magmatic phases recorded in the WES, a period that defines major tectonic reorganization throughout the East African Orogen (Merdith et al. Reference Merdith, Collins, Williams, Pisarevsky, Foden, Archibald, Blades, Alessio, Armistead, Plavsa and Clark2017). We suggest that the ultramafic bodies of Daleti, Tulu Dimtu, Abshala Melange and Yubdo were formed close to the initiation of supra-subduction and the beginning of known magmatism in the WES. Therefore, we conclude that these ultramafic complexes are indeed remnants of the Mozambique Ocean. They originated as new ocean crust and intrusions formed during the break-up of Rodinia and onset of subduction, and were fortuitously preserved by emplacement in shear zones in the East African Orogen during the final assembly of Gondwana.

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship Award to ASC (FT120100340). It forms TRaX Record #xxx and is a contribution to IGCP Projects #628 and #648. MB is funded by a University of Adelaide Ph.D. scholarship. Please note that TA does not agree with the chosen lithological divisions outlined in this manuscript. We would like to acknowledge the Research and Development Directorate of the Ethiopian Ministry of Mines, Petroleum and Natural Gas and the Geological Survey of Ethiopia for providing transport service, coordinating and facilitating the field activities. We would like to thank both reviewers Professor Peter Johnson and Professor Hassan Helmy for their insightful comments on this manuscript.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756817000802.