1. Introduction

Amber fossils provide a unique window into the geological past of the Earth’s biosphere. The exceptional preservation of fossils in amber frequently provides access to the finest morphological details and occasionally even the shapes of organic material such as soft bodies or feathers (e.g. Poinar & Hess, Reference Poinar and Hess1985; Henwood, Reference Henwood1992; Grimaldi et al. Reference Grimaldi, Bonwich, Delannoy and Doberstein1994; Xing et al. Reference Xing, McKellar, O’Connor, Bai, Tsend and Chiappe2019, Reference Xing, O’Connor, Niu, Cockx, Mai and McKellar2020; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Matzke-Karasz, Horne, Zhao, Cao, Zhang and Wang2020).

Burmese amber in northern Myanmar has provided among the most abundant fossils from amber deposits. Descriptions of amber inclusions dating back to the early 20th century (Cockerell, Reference Cockerell1916) indicate that the region has been mined for over 100 years. Since the turn of the century, scientists have become increasingly aware of the outstanding potential of Burmese amber to advance palaeontological research. Burmese amber has provided a rare insight into mid-Cretaceous terrestrial forest environments that were creeping, crawling and slithering with insects, arachnids, myriapods, crustaceans, nematodes, annelids, snails, amphibians and reptiles (Ross, Reference Ross2019). Particularly over the last decade, the excavation of exceptional fossils has attracted researchers worldwide and sparked a major wave of species discoveries (Ross, Reference Ross2019). Approximately 1200 species of animal and plants have been described and many more are awaiting description (Ross, Reference Ross2019; Sokol, Reference Sokol2019). In addition, a number of marine animals have been recorded trapped in the treacherous resin (Smith & Ross, Reference Smith and Ross2018; Xing et al. Reference Xing, Sames, McKellar, Xi, Bai and Wan2018 a; Yu et al. Reference Yu, Kelly, Mu, Ross, Kennedy, Broly, Xia, Zhang, Wang and Dilcher2019).

Here, we present a novel finding of two freshwater snails of the family Lymnaeidae preserved in Burmese amber. We describe a new species and discuss the implications of this record for palaeoecology and biogeography of the Lymnaeidae. We propose five hypotheses to explain the disjunct occurrence on an island in the mid-Cretaceous Tethys Sea.

2. Materials and methods

The material derives from a former amber mine near Noije Bum in Tanaing Township in northernmost Myanmar. We are aware of the toxic situation associated with the mining of Burmese amber, involving armed conflict and civilian casualties since November 2017. While we clearly condemn the actions violating international human rights and humanitarian law, we argue in line with Haug et al. (Reference Haug, Azar, Ross, Szwedo, Wang, Arillo, Baranov, Bechteler, Beutel, Blagoderov, Delclòs, Dunlop, Feldberg, Feldmann, Foth, Fraaije, Gehler, Harms, Hedenäs, Hyžný, Jagt, Jagt-Yazykova, Jarzembowski, Kerp, Khine, Kirejtshuk, Klug, Kopylov, Kotthoff, Kriwet, McKellar, Nel, Neumann, Nützel, Peñalver, Perrichot, Pint, Ragazzi, Regalado, Reich, Rikkinen, Sadowski, Schmidt, Schneider, Schram, Schweigert, Selden, Seyfullah, Solórzano-Kraemer, Stilwell, van Bakel, Vega, Wang, Xing and Haug2020) that our specimens were mined legally before November 2017 and do not qualify as “blood amber”.

Dating of zircons embedded in the volcanoclastic matrix containing the amber yielded a maximum age of c. 99 Ma (Shi et al. Reference Shi, Grimaldi, Harlow, Wang, Wang, Yang, Lei, Li and Li2012). This agrees with biostratigraphic data based on ammonites found in the amber-bearing beds and within the amber, indicating a late Albian – early Cenomanian age (Cruickshank & Ko, Reference Cruickshank and Ko2003; Yu et al. Reference Yu, Kelly, Mu, Ross, Kennedy, Broly, Xia, Zhang, Wang and Dilcher2019).

The amber pieces containing the two shells are translucent yellow. The specimens were photographed using a Zeiss AXIO Zoom V16 microscope system with the stacking function at the State Key Laboratory of Palaeobiology and Stratigraphy, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (NIGPAS). The final images are composites of approximately 50 individual focal planes that were combined with the software Helicon Focus 6.

Additionally, the holotype and paratype individuals were scanned with a ZEISS Xradia 520 versa 3D X-ray microscope at the micro-CT lab of NIGPAS. A charge-coupled device detector and a 0.4× objective, providing isotropic voxel sizes from 0.5 mm with the help of geometric magnification, were used to obtain high resolution. The running voltage for the X-ray source was set at 50 kV (for NIGP1) and 60 kV (for NIGP2), and a thin filter (LE2) was applied to avoid beam-hardening artefacts. A total of 2001 projections over 360° were collected and the exposure time for each projection was set at 2 s (for NIGP1) and 2.5 s (for NIGP2) to obtain a high signal-to-noise ratio. Volume data were processed with the program VGSTUDIO MAX 3.0 (Volume Graphics, Heidelberg, Germany). Images were edited and arranged using the CorelDraw Graphics Suite X8.

Shell measurements include shell height (H), greatest width of shell perpendicular to height (D), aperture height parallel to shell height (h) and aperture width perpendicular to aperture height (d). All specimens are stored at the collection of NIGPAS. The publication and the nomenclatural act contained here are registered under http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:6A5BFAA2-D508-4D63-861A-6DDDB071B689.

3. Systematic palaeontology

Class GASTROPODA Cuvier, Reference Cuvier1795

Subclass HETEROBRANCHIA Burmeister, Reference Burmeister1837

Superorder HYGROPHILA Férussac, Reference Férussac1822

Superfamily LYMNAEOIDEA Rafinesque, Reference Rafinesque1815

Family LYMNAEIDAE Rafinesque, Reference Rafinesque1815

Genus Galba Schrank, Reference Schrank1803

Type species. Galba truncatula O. F. Müller, Reference Müller1774; type by subsequent designation; Recent, Europe.

Galba prima sp. nov.

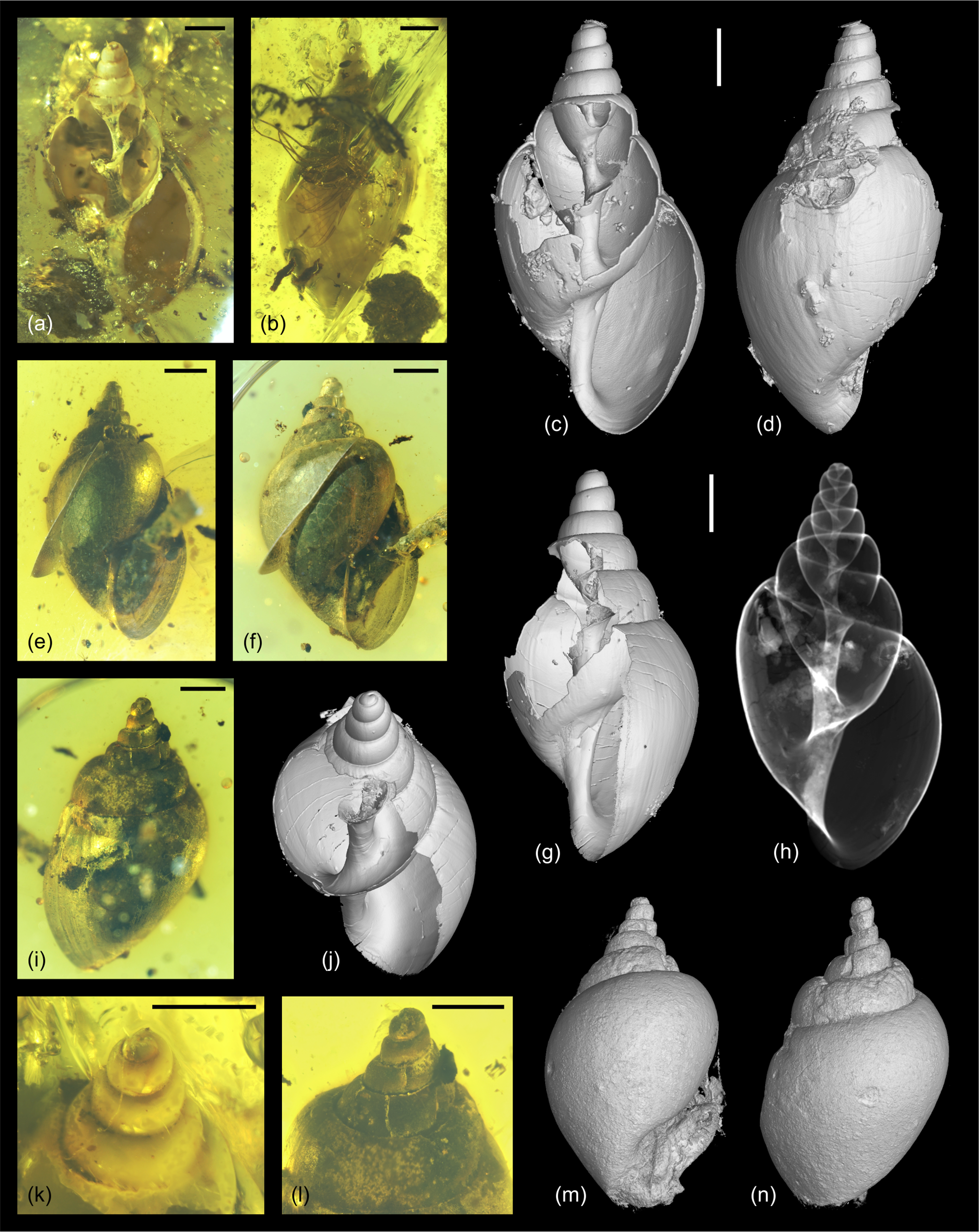

(Fig. 1)

Fig. 1. Galba prima sp. nov. (a–d, g, h, j, k) holotype (NIGP173920). (e, f, i, l–n) paratype (NIGP173921); note the spire is slightly deformed. (c, d, g, j, m, n) are microtomographic reconstructions; (h) shows surface rendering with transparency. All scale bars represent 1 mm.

ZooBank LSID: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:095524C3-D5A1-4DC5-A26B-5142A2D39B5A

Derivation of name. The species epithet refers to it being the first freshwater gastropod species found in amber.

Holotype. NIGP173920.

Paratype. NIGP173921.

Type locality and horizon. Former amber mine near Noije Bum Village, Tanaing Township, Myitkyina District, Kachin State, northern Myanmar (26° 15ʼ N, 96° 33ʼ E); unnamed horizon, mid-Cretaceous, lower Cenomanian, c. 99 Ma.

Diagnosis. Small shell with slightly coeloconoid spire, weakly stepped whorls separated by deep suture, large and inflated body whorl, slender ovate aperture, nearly straight columella without fold, and small, circular umbilicus.

Description. Shell small, consisting of about 6–6.5 whorls. Height:width ratio is 1.66 (paratype) and 1.84 (holotype). Protoconch blunt, low domical; no surface details visible. Spire slightly coeloconoid, spire angle 60–65°. Whorls stepped, with straight-sided or weakly convex lower part and strongly convex upper part; whorls separated by deep suture; spire whorls increase gradually in height, with the last whorl being broad, slightly inflated and 71–78% of total shell height. Columella not twisted, forming almost straight pillar from apex to umbilicus. Peristome thin and sharp all around aperture; columellar lip slightly reflected towards umbilicus. Umbilicus small, circular, c. 0.25 mm in diameter. Aperture slender ovoid, adapically angulated, not expanded; height of aperture attains 57–63% of total height. Surface smooth except for faint, weakly prosocline growth lines.

Measurements. Holotype: H = 7.89 mm, D = 4.28 mm, h = 4.34 mm, d = 2.38 mm; paratype: H = 6.19 mm, D = 3.74 mm, h = 3.69 mm, d = 1.61 mm.

Remarks. Modern genus classification of extant Lymnaeidae is largely based on anatomical characteristics and molecular data (e.g. Correa et al. Reference Correa, Escobar, Durand, Renaud, David, Jarne, Pointier and Hurtrez-Boussès2010; Vinarski Reference Vinarski2013), while fossil shells can only be distinguished based on general morphology, sculpture and protoconch characteristics. We attribute the species to the genus Galba due to the small shell with stepped whorls, the inflated and expanded body whorl, the comparatively small, non-expanded aperture, the thin peristome without columellar fold (Fig. 1c, g, h) and the presence of an umbilicus (Fig. 1f).

Species of Aenigmomphiscola Kruglov & Starobogatov, Reference Kruglov and Starobogatov1981, Hinkleyia Baker, Reference Baker1928, Ladislavella Dybowski, Reference Dybowski1913, Omphiscola Rafinesque, Reference Rafinesque1819, Stagnicola Jeffreys, Reference Jeffreys1830 and Walterigalba Kruglov & Starobogatov, Reference Kruglov and Starobogatov1985 have more elongated shells, often with cyrtoconoid spires, and columella folds, while Ampullaceana Servain, Reference Servain1882, Peregriana Servain, Reference Servain1882 and Radix Montfort, Reference Montfort1810 species are typically more globular with broader apertures (Vinarski & Grebennikov, Reference Vinarski and Grebennikov2012; Vinarski et al. Reference Vinarski, Bolotov, Schniebs, Nekhaev and Hundsdoerfer2017, Reference Vinarski, Aksenova and Bolotov2020 a; Glöer, Reference Glöer2019). Even the more slender representatives of Radix, such as Radix labiata (Rossmässler, Reference Rossmässler1835), can be well distinguished from Galba prima sp. nov. by their expanded apertures. Lymnaea s.s. species are much larger and have a twisted axis (Vinarski, Reference Vinarski2015; Anistratenko et al. Reference Anistratenko, Vinarski, Anistratenko, Furyk and Degtyarenko2018; Glöer, Reference Glöer2019). Similarly, shells of Bulimnea Haldeman, Reference Haldeman1841 have a twisted columella and lack an umbilicus (Baker, Reference Baker1911). The Australian Austropeplea Cotton, Reference Cotton1942 also bears a more expanded aperture and no umbilicus (Dell, Reference Dell1956; Ponder et al. Reference Ponder, Hallan, Shea, Clark, Richards, Klunzinger and Kessner2020).

Some species of Orientogalba Kruglov & Starobogatov, Reference Kruglov and Starobogatov1985, a genus native to Asia, have a similar shell habitus with inflated body whorl and short spire, such as O. viridis (Quoy & Gaimard, 1833–Reference Quoy and Gaimard1835) and O. ollula (Gould, Reference Gould1859), but they lack the umbilicus (Vinarski et al. Reference Vinarski, Aksenova and Bolotov2020 a). Also, O. viridis has an expanded aperture (Vinarski et al. Reference Vinarski, Aksenova and Bolotov2020 a). Orientogalba lenaensis (Kruglov & Starobogatov, Reference Kruglov and Starobogatov1985), in turn, is much more slender and has a high spire (Sitnikova et al. Reference Sitnikova, Sysoev and Prozorova2014).

The fossil Mesozoic genus Proauricula Huckriede, Reference Huckriede1967, which was tentatively considered a basal basommatophoran and predecessor of modern Lymnaeidae by Bandel (Reference Bandel1991), has a more slender shell with columellar plicae and distinct spiral striation on the teleoconch (Huckriede, Reference Huckriede1967; Bandel, Reference Bandel1991; Pan & Zhu, Reference Pan and Zhu2007). In fact, the overall shape and especially the distinct columellar plicae make a relationship to Lymnaeidae very unlikely. The shape and apertural characteristics are more similar to Ellobiidae, where the genus was originally placed by Huckriede (Reference Huckriede1967) and which was also adopted by Pan & Zhu (Reference Pan and Zhu2007). Here, we accept this original classification and place Proauricula tentatively in the Ellobiidae. That family was well represented during the Mesozoic Era by several genera and species (Yen, Reference Yen1951, Reference Yen1952 a, b, Reference Yen1954; Bandel, Reference Bandel1991; Bandel & Riedel, Reference Bandel and Riedel1994; Pan & Zhu, Reference Pan and Zhu2007; Isaji, Reference Isaji2010).

Of the 13 mid-Cretaceous lymnaeids, only two species are currently classified in Galba, that is, G. yongkangensis Yü in Yü & Pan, Reference Yü and Pan1980 and G. meikiensis Yü in Yü & Pan, Reference Yü and Pan1980 from the Albian Guantou Formation in China. The former is more elongate and has a cyrtoconoid spire, while the latter can be distinguished from Galba prima sp. nov. by its higher last and penultimate whorl (Yü & Pan, Reference Yü and Pan1980). Similarly, Radix undensis Martinson, Reference Martinson1956 from Aptian–Albian strata of Siberia has a higher, globular last whorl and a very short spire. The four Cenomanian species from France, introduced in the genus “Limnaea” by Repelin (Reference Repelin1902), are more slender and have higher spires; only some specimens of L. munieri Repelin, Reference Repelin1902 have a similar morphology, but the species clearly differs from G. prima sp. nov. in having convex, non-stepped whorls. The American “Lymnaea” nitidula (Meek, Reference Meek1860), “Lymnaea” ativuncula White, Reference White1886 and “Lymnaea” tengchieni Kadolsky, Reference Kadolsky1995 (= L. cretacea Yen, Reference Yen1951, non Thomä, Reference Thomä1845) are distinctly more slender, while “Lymnaea” sagensis Yen, Reference Yen1946 has a globular shell and more reminiscent of a viviparid than a lymnaeid. An unidentified ?Austropeplea sp. from Albian–Cenomanian strata of New Zealand is only incompletely preserved, but the species appears to be broader and bears spiral microsculpture.

4. Discussion

Unsurprisingly, amber mostly preserves terrestrial biota, but a number of freshwater organisms are also known from amber deposits, including arthropods, nematodes and amoebae (Gray, Reference Gray1988; Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Schönborn and Schäfer2004; Yu et al. Reference Yu, Kelly, Mu, Ross, Kennedy, Broly, Xia, Zhang, Wang and Dilcher2019). The species described herein is the first freshwater snail ever recorded in amber. This mode of preservation is likely due to the species’ lifestyle and aquatic niche: several extant members of the Lymnaeidae, including species of Galba, are amphibious (Dillon, Reference Dillon2000). For example, Galba truncatula (Müller, Reference Müller1774) is commonly found outside the water and can withstand droughts for an extensive period of time; some individuals have been found surviving for over a year in aestivation (Kendall, Reference Kendall1949). However, extensive droughts were rather unlikely in the Cenomanian tropical forests of the Burma Terrane (Poinar et al. Reference Poinar, Lambert and Wu2007; Xing et al. Reference Xing, Stanley, Bai and Blackburn2018 b; Yu et al. Reference Yu, Kelly, Mu, Ross, Kennedy, Broly, Xia, Zhang, Wang and Dilcher2019). Rather, the snail might have been captured in resin flowing down or dropping from trees close to a water body. Since extant Galba is typically found in stagnant and often temporary water bodies, such as lakes, ponds, ditches, mires and puddles (Kendall, Reference Kendall1949; Økland, Reference Økland1990), we assume a similar aquatic biome close to the place of deposition.

The present finding also has implications for the biogeography of the family Lymnaeidae. Galba prima sp. nov. is among the few fossil Lymnaeidae known from early Late Cretaceous time. The only other relatives of similar age have been reported from Cenomanian strata of France (Repelin, Reference Repelin1902) and the Albian–Cenomanian deposits of New Zealand (Beu et al. Reference Beu, Marshall and Reay2014; see also Section 3 above on Systematic Palaeontology). Slightly older records have been documented from Aptian–Albian strata of North America (White, Reference White1886; Yen, Reference Yen1946, Reference Yen1951, Reference Yen1954), Russia (Martinson, Reference Martinson1956) and China (Yü & Pan, Reference Yü and Pan1980; Pan & Zhu, Reference Pan and Zhu2007).

However, Galba prima sp. nov. is not the earliest member of the genus; alleged records of Galba date back to the Middle Jurassic Epoch of China (Pan, Reference Pan1977; Yü & Pan, Reference Yü and Pan1980). Their attribution to the genus (and in some cases even to the family Lymnaeidae) has not yet been confirmed with certainty and requires a detailed reassessment of the respective species.

The disjunct distribution of the family and particularly the isolated occurrence of Galba prima sp. nov. on the Burma Terrane are striking – how did a freshwater snail reach an island at least 1500 km from the nearest mainland (Fig. 2)? In the following, we propose five hypotheses that could explain the disjunct occurrence. Some of these hypotheses may also serve as an explanatory model for the existence of terrestrial and other freshwater biota on the Burma Terrane. All hypotheses rely on the recently published tectonic model for the Burma Terrane as an island in the Cenomanian Tethys Ocean (Westerweel et al. Reference Westerweel, Roperch, Licht, Dupont-Nivet, Win, Poblete, Ruffet, Swe, Thi and Aung2019; Fig. 2).

-

(1) Modern Lymnaeidae, as well as many other freshwater snails, are commonly distributed via waterbirds (Green & Figuerola, Reference Green and Figuerola2005; Kappes & Haase, Reference Kappes and Haase2012; van Leeuwen & van der Velde, Reference van Leeuwen and van der Velde2012; van Leeuwen et al. Reference van Leeuwen, van der Velde, van Lith and Klaassen2012, Reference van Leeuwen, Huig, van der Velde, van Alen, Wagemaker, Sherman, Klaassen and Figuerola2013; Vinarski et al. Reference Vinarski, Bolotov, Aksenova, Babushkin, Bespalaya, Makhrov, Nekhaev and Vikhrev2020 b). Although some species may occasionally be transported by song birds (e.g. Zenzal et al. Reference Zenzal, Lain and Sellers2017), this seems to be the exception rather than the rule. Passive transport of snails via travelling and migrating birds provides a unique opportunity for long-distance dispersal across watersheds. Snails travel attached to feathers or feet and can survive ingestion and defecation. Dispersal via waterfowl has been hypothesized to explain many a disjunct fossil occurrence in Cenozoic strata (Harzhauser et al. Reference Harzhauser, Mandic, Neubauer, Georgopoulou and Hassler2016; Aksenova et al. Reference Aksenova, Bolotov, Gofarov, Kondakov, Vinarski, Bespalaya, Kolosova, Palatov, Sokolova, Spitsyn, Tomilova, Travina and Vikhrev2018; Esu & Girotti, Reference Esu and Girotti2018) and likely contributed markedly to the already large distribution of the family in Mesozoic strata. However, waterfowl (Anseriformes) did not evolve before latest Cretaceous time, and even the oldest neognathe bird is younger than the new Cenomanian Lymnaeidae (c. 85 Ma according to Claramunt & Cracraft, Reference Claramunt and Cracraft2015). Little is known about the flight capabilities of Mesozoic birds. Early Cretaceous ornithurines already possessed anatomical features similar to those of modern migratory birds, such as a keeled sternum (Falk, Reference Falk2011). Based on the appearance of the same types of bird routes across great distances, Falk (Reference Falk2011) suggested that ornithurine birds might have evolved long-distance migration in or before the Early Cretaceous Epoch, but clear evidence is lacking. Enantiornithines, a group widely represented in the global Cretaceous fossil record, have been recorded several times in Burmese amber (Xing et al. Reference Xing, McKellar, Xu, Li, Bai, Persons, Miyashita, Benton, Zhang, Wolfe, Yi, Tseng, Ran and Currie2016, Reference Xing, O’Connor, McKellar, Chiappe, Tseng, Li and Bai2017, Reference Xing, McKellar, O’Connor, Bai, Tsend and Chiappe2019, Reference Xing, O’Connor, Niu, Cockx, Mai and McKellar2020). Their plumage would likely have been suitable for transporting the tiny snail, but current knowledge indicates that this group was only capable of flap-gliding and bounding flight (e.g. Liu et al. Reference Liu, Chiappe, Serrano, Habib, Zhang and Meng2017; Serrano et al. Reference Serrano, Chiappe, Palmqvist, Figueirido, Marugán-Lobón and Sanz2018). Probably, enantiornithines were already present on the Burma Terrane before it detached from Gondwana during the Jurassic Period (Matthews et al. Reference Matthews, Maloney, Zahirovic, Williams, Seton and Müller2016).

-

(2) An alternative winged animal group existing during the Cenomanian Age were pterosaurs (Order Pterosauria). So far, they have not been considered potential dispersal agents for invertebrates, but previous studies suggest that Cretaceous pterosaurs may have dispersed angiosperm seeds (Fleming & Lips, Reference Fleming and Lips1991). In addition to the aforementioned ornithurine birds, pterosaurs were likely capable of long-distance travels (Witton & Habib, Reference Witton and Habib2010). Some species probably fed on molluscs (Bestwick et al. Reference Bestwick, Unwin, Butler, Henderson and Purnell2018). Pterosaurs may therefore have dispersed freshwater snails via ingestion or by attachment to the feet or scales on the legs or tail, comparable to similar occurrences in modern birds. However, no pterosaur fossil has so far been retrieved from Burmese amber deposits that could potentially support this hypothesis. Other animal groups, such as amphibians or larger insects, which have occasionally been found carrying freshwater molluscs (e.g. Walther et al. Reference Walther, Benard, Boris, Enstice, Tindauer-Thompson and Wan2008; Kolenda et al. Reference Kolenda, Najbar, Kusmierek and Maltz2017), are unlikely to play a significant role in long-distance dispersal.

-

(3) Driftwood is known to be a potential transoceanic vector for terrestrial and amphibious animals (e.g. Trewick, Reference Trewick2001; Measey et al. Reference Measey, Vences, Drewes, Chiari, Melo and Bourles2007) as well as brackish-water gastropods, such as Littorinidae (Reid, Reference Reid1986) or estuarine Neritidae (Kano et al. Reference Kano, Fukumori, Brenzinger and Warén2013). While these brackish-water snails have a marine larval phase facilitating wider dispersal, Lymnaeidae are restricted to freshwater environments. We cannot exclude that Galba prima sp. nov. boarded driftwood in a river or estuary and survived the long journey (perhaps during aestivation), but we believe it is fairly unlikely given the great distance and ecological constraints. However, driftwood (or any kind of drifting islands) may have facilitated dispersal of Cenomanian land snails (compare Dörge et al. Reference Dörge, Walther, Beinlich and Plachter1999), which may have had a higher chance of long-term survival due to their ability to close the shell with an operculum or epiphragm (Ożgo et al. Reference Ożgo, Örstan, Kirschenstein and Cameron2016).

-

(4) Several studies have indicated the possibility of dispersal via wind, particularly strong storms. Numerous examples of “raining fishes” exist from the recent past as well as historical documents worldwide, where storms carried both marine and freshwater fishes over large distances (Rees, Reference Rees1965). A case of freshwater Anodonta, a genus of unionid bivalves, raining down over Germany after a storm was reported in the 19th century (Rees, Reference Rees1965). Ożgo et al. (Reference Ożgo, Örstan, Kirschenstein and Cameron2016) demonstrated land snail dispersal by strong storms in northern Europe. They concluded that wind currents associated with storm cells may also facilitate long-distance dispersal. A similar hypothesis was proposed by Vagvolgyi (Reference Vagvolgyi1975) explaining how land snails could colonize remote Pacific islands. The terrestrial ecosystems in the area that comprises Southeast Asia today were also likely perturbed by tropical storms as long ago as during the Cenomanian Age. Considering the overall high temperature in the Cretaceous greenhouse (Mills et al. Reference Mills, Krause, Scotese, Hill, Shields and Lenton2019), storm frequency and intensity were probably higher than today (Ghosh et al. Reference Ghosh, Prasanna, Banerjee, Williams, Gagan, Chaudhuri and Suwas2018). The prevailing wind stress reconstructed for the mid-Cretaceous period by Poulsen et al. (Reference Poulsen, Seidov, Barron and Peterson1998) points from mainland Asia towards the Tethys Ocean, matching the required dispersal direction. Since the Burma Terrane was south of the equator during the Cenomanian Age according to the latest palaeogeographic model (Westerweel et al. Reference Westerweel, Roperch, Licht, Dupont-Nivet, Win, Poblete, Ruffet, Swe, Thi and Aung2019), the only storms that could potentially transport the snails towards the Burma Terrane would have originated in the southern Woyla Arc or the southern Sundaland Block and moved westwards along the Southern Hemisphere trade winds (Fig. 2). However, no fossil record is available to support this hypothesis.

-

(5) Finally, Lymnaeidae may have reached the Burma Terrane when it was still attached to Gondwana prior to the opening of the Neotethys Ocean during latest Jurassic time (Matthews et al. Reference Matthews, Maloney, Zahirovic, Williams, Seton and Müller2016) and they survived there until the Cenomanian Age (without fossil record). However, this still leaves open how the family got there in the Jurassic Period, when their fossil record was limited to the Northern Hemisphere. Despite the patchiness of the fossil record, especially for freshwater habitats during the Mesozoic Era, the lack of any evidence makes this, in our opinion, the least plausible hypothesis.

Fig. 2. Reconstruction of the Burma Terrane during the Cenomanian Age (95 Ma). Modified from Westerweel et al. (Reference Westerweel, Roperch, Licht, Dupont-Nivet, Win, Poblete, Ruffet, Swe, Thi and Aung2019).

Given the uncertainties involved in many of these hypotheses, we do not support a particular explanation model. However, considering the great distance and ecological constraints, we believe airborne dispersal – whether via ornithurine birds, pterosaurs or storms – is the most plausible means.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Gerald Mayr for discussing long-distance dispersal capabilities of Mesozoic birds and pterosaurs. David Bullis and an anonymous reviewer provided helpful comments that improved an earlier version of the paper. This research was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (TY, XDA19050101, XDB26000000), the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research (TY, 2019QZKK0706) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (TY, 41688103).

Conflict of interest

None.