1. Introduction

With biomineralized exoskeletons of more than 20000 species discovered (only inferior to ostracods; Zhang, Reference Zhang and Zhang2013), the trilobites (= Trilobita) are one of the most diverse extinct groups of Euarthropoda (e.g. Budd & Telford, Reference Budd and Telford2009) that inhabited Palaeozoic seas from the Cambrian explosion (Hollingsworth, Reference Hollingsworth, Rábano, Gozalo and García-Bellido2008) to the end-Permian mass extinction (Owens, Reference Owens2003). However, in contrast to the megadiversity of exoskeletons, the soft-bodied anatomy of trilobites is poorly known, with only ~ 30 species primarily from Konservat-Lagerstätten showing soft-part preservation, especially appendages (Table 1; also see Hughes, Reference Hughes2003).

Table 1. Updated summary of trilobites reported with preserved appendages, supplemented and modified from Hughes (Reference Hughes2003)

Orders and families are mainly based on Harrington et al. (Reference Harrington, Henningsmoen, Howell, Jaanusson, Lochman-Balk, Moore, Poulsen, Rasetti, Richter, Richter, Schmidt, Sdzuy, Struve, Størmer, Stubblefield, Tripp, Weller and Whittington1959) and Whittington et al. (Reference Whittington, Chatterton, Speyer, Fortey, Owens, Chang, Dean, Geyer, Jell, Laurie, Palmer, Repina, Rushton, Shergold, Clarkson, Wilmot and Kelly1997). Note that the former Elrathina cordillerae from the Burgess Shale is revised as an unnamed new species of Elrathina (Geyer & Peel, Reference Geyer and Peel2017). Preservation of complete, incomplete and absent anatomical structures are indicated by ‘++’, ‘+’ and ‘o’, respectively. Abbreviations: an – antenna; ds – digestive system; en – endopodite; ex – exopodite.

To date, all the reported appendages of polymerid trilobites consist of a pair of uniramous deutocerebral antennae and a series of homonomous biramous post-antennal limbs corresponding to each body segment (see Hughes, Reference Hughes2003; Scholtz & Edgecombe, Reference Scholtz and Edgecombe2005, Reference Scholtz and Edgecombe2006). It should be emphasized that the morphology of the post-antennal limbs of Agnostus pisiformis is distinct from that of polymerid trilobites (Müller & Walossek, Reference Müller and Walossek1987), which makes the supposed trilobite affinity of Agnostida problematic (Walossek & Müller, Reference Walossek and Müller1990; Fortey, Reference Fortey2001; Hughes, Reference Hughes2003). Although antennae of exactly similar uniramous multi-segmented architecture are preserved in ~ 20 of these polymerid trilobite species, complete post-antennal limbs have only been reconstructed in six species from five of the nine polymerid orders of Trilobita, including Eoredlichia intermedia, Olenoides serratus, Triarthrus eatoni, Cryptolithus bellulus, Ceraurus pleurexanthemus and Chotecops ferdinandi (see Table 1 for details; Fortey, Reference Fortey2001; Hughes, Reference Hughes2003, Reference Hughes2007). The known post-antennal limbs of these different polymerid trilobite species share a biramous architecture, with two rami (endopodite and exopodite) connected to a protopodite (e.g. Hughes, Reference Hughes2003). The protopodite consists of a single segment (e.g. Ramsköld & Edgecombe, Reference Ramsköld and Edgecombe1996) and the endopodite is made up of seven segments (e.g. Hughes, Reference Hughes2003; Boxshall, Reference Boxshall2004). Nevertheless, the exopodites show considerable morphological variations in different trilobite species (Müller & Walossek, Reference Müller and Walossek1987, fig. 27; Shu et al. Reference Shu, Geyer, Chen and Zhang1995, fig. 21; also see Bruton & Haas, Reference Bruton and Haas1999, fig. 22 and Hou et al. Reference Hou, Clarkson, Yang, Zhang, Wu and Yuan2008, fig. 14 for revised reconstructions for C. ferdinandi and E. intermedia, respectively). Other exceptional appendages of polymerid trilobites include a pair of antennae-like cerci that has only been found in the pygidium of O. serratus (e.g. Whittington, Reference Whittington1975, Reference Whittington1980).

The limited knowledge of the soft anatomy of trilobites and other stem-group euarthropods, especially appendages, has long constrained our understanding of the internal and external phylogenetic relationships of trilobites (see Scholtz & Edgecombe, Reference Scholtz and Edgecombe2005, Reference Scholtz and Edgecombe2006 and references therein). It was not until recently that phylogenetic analyses resolved the trilobites within the Artiopoda Hou & Bergström, Reference Hou and Bergström1997, as close relatives to several groups of soft-bodied ‘trilobitomorph’ euarthropods from Cambrian Lagerstätten (e.g. Edgecombe & Ramsköld, Reference Edgecombe and Ramsköld1999; Ortega-Hernández, Legg & Braddy, Reference Ortega-Hernández, Legg and Braddy2013; Stein et al. Reference Stein, Budd, Peel and Harper2013; Legg, Sutton & Edgecombe, Reference Legg, Sutton and Edgecombe2013). These ‘trilobitomorphs’, including concilitergans (e.g. Kuamaia and Saperion), nektaspids (e.g. Naraoia, Liwia and Emucaris), xandarellids (e.g. Xandarella and Cindarella) and other problematic taxa, share the common appendage architecture composed of a pair of uniramous antennae and homonomous post-antennal biramous limbs, as well as other synapomorphies, with polymerid trilobites (e.g. Hou & Bergström, Reference Hou and Bergström1997; Edgecombe & Ramsköld, Reference Edgecombe and Ramsköld1999; Zhang, Shu & Erwin, Reference Zhang, Shu and Erwin2007; Ortega-Hernández, Legg & Braddy, Reference Ortega-Hernández, Legg and Braddy2013). Nevertheless, phylogenetic analyses have not reached a consensus on the sister group of trilobites and cannot determine whether the entire Artiopoda is closer to the Mandibulata or Chelicerata at present (e.g. Budd & Telford, Reference Budd and Telford2009; Ortega-Hernández, Legg & Braddy, Reference Ortega-Hernández, Legg and Braddy2013; Stein et al. Reference Stein, Budd, Peel and Harper2013; Legg, Reference Legg2014). Therefore, further studies on trilobite soft anatomy are essential to deliver arguments for answers to these questions.

Here we describe exceptionally preserved appendages of the polymerid trilobite Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis Zhang & Lin in Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Lu, Zhu, Qian, Lin, Zhou, Zhang and Yuan1980 (Redlichiida, Metadoxididae) from the Xiazhuang fossil assemblage in the Hongjingshao Formation (Cambrian Series 2, Stage 3) near Kunming, Yunnan, SW China. The new material confirms the basic architecture of trilobite/artiopodan appendages, but also exhibits a morphological disparity in trilobite/artiopodan exopodites, providing new information for comparative anatomy and elucidating the affinities of trilobites and other related artiopods.

2. Geological setting

All specimens of Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis were recovered from a single yellowish structureless claystone layer intercalated within sandstone layers from the lower part of the Hongjingshao Formation, the lower fossil horizon yielding the Xiazhuang fossil assemblage at Xiazhuang, Chenggong, Kunming, eastern Yunnan, SW China (see Zeng et al. Reference Zeng, Zhao, Yin, Li and Zhu2014 for detailed information on geography and stratigraphy). The soft-part preservation and various angles of burial of the fossils indicate that the fossiliferous layer was deposited rapidly, probably by a storm event (e.g. Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Li, Zhang, Steiner, Qian and Jiang2001; Hu et al. Reference Hu, Zhu, Steiner, Luo, Zhao and Liu2010, Reference Hu, Zhu, Luo, Steiner, Zhao, Li, Liu and Zhang2013). Other euarthropods recovered from the same layer only include a large bivalve euarthropod Jugatacaris?, whose biramous limbs comprise more than 20 endopodite podomeres and are readily distinguishable from the trilobite limbs (Zeng et al. Reference Zeng, Zhao, Yin, Li and Zhu2014). Although other trilobite species including Yunnanocephalus yunnanensis, Malongocephalus yunnanensis and Kuanyangia (Sapushania) granulosa were also found in the upper fossil horizon (Zeng et al. Reference Zeng, Zhao, Yin, Li and Zhu2014), none of these species were discovered from the Hongshiyanaspis bed. The age of the Xiazhuang fossil assemblage is approximately identical to that of the lower part of the Xiaoshiba Lagerstätte (e.g. Hou et al. Reference Hou, Hughes, Yang, Lan, Zhang and Dominguez2017) because both fossil assemblages are from the same stratigraphic interval in the lower part of the Hongjingshao Formation and from the same Eoredlichia–Wutingaspis Assemblage Zone of the regional Qiongzhusian Stage (Cambrian Stage 3). This fossil zone also yields the renowned Chengjiang biota from the underlying Yu'anshan Formation (Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Li, Zhang, Steiner, Qian and Jiang2001). The similar age and faunal compositions suggests that these two fossil assemblages from the Hongjingshao Formation can be regarded as continuing the Chengjiang biota (Zeng et al. Reference Zeng, Zhao, Yin, Li and Zhu2014). However, the upper part of the Xiaoshiba Lagerstätte extends into the regional Canglangpuan (Cambrian Stage 3) Yiliangella Assemblage Zone represented by Zhangshania typica (Hou et al. Reference Hou, Hughes, Yang, Lan, Zhang and Dominguez2017), an interval which is absent in the section that contains the Xiazhuang fossil assemblage (Zeng et al. Reference Zeng, Zhao, Yin, Li and Zhu2014).

3. Materials and methods

A total of 106 early to fully grown holaspid specimens of the trilobite Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis were studied (Field IDs prefixed by HBHY; see online Supplementary Material available at http://journals.cambridge.org/geo). The majority of these specimens are dorsoventrally embedded, with only 11.3% laterally compressed. Nearly half of them (45.3%) exhibit preserved soft parts, including antennae, biramous limbs and parts of the digestive system. Owing to the different angles of burial, the shapes of original three-dimensional structures can vary, especially for the biramous limbs, but structures in various positions or on different levels can also reveal additional details of the morphology. Similar to soft parts of the Chengjiang fossils, the appendages of H. yiliangensis are preserved mainly as Fe-rich aluminosilicate films with limited organic ingredients (Zhu, Babcock & Steiner, Reference Zhu, Babcock and Steiner2005).

All figured specimens are housed at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (prefixed by NIGPAS). Appendages were prepared manually using blades. Photographs showing overall morphology were taken using a Nikon D300s digital camera with a Nikon AF-S VR105mm f/2.8G macro lens. Detailed anatomy was captured using a Carl Zeiss SteREO Discovery V12 microscope linked to an AxioCam HR3 digital microscope CCD camera. Illumination from various directions and angles was employed in order to show the three-dimensional structures. Line drawings were prepared on the basis of high-resolution pictures. Measurements were conducted on photographs within Adobe Photoshop™ CS6 and statistically analysed in Microsoft Office Excel™ 2013.

We follow most of the standard terminology for trilobites in Whittington et al. (Reference Whittington, Chatterton, Speyer, Fortey, Owens, Chang, Dean, Geyer, Jell, Laurie, Palmer, Repina, Rushton, Shergold, Clarkson, Wilmot and Kelly1997), including the terms ‘antenna(e)’, ‘endopodite(s)’ and ‘exopodite(s)’, which are also the most commonly used terms in recent literature on fossil and extant euarthropods. However, the neutral term ‘protopodite’ is used rather than the term ‘basis’ or ‘basipodite’ (e.g. Boxshall, Reference Boxshall2004), which is equal to the term ‘coxa’ or ‘coxopodite’ in earlier studies (e.g. Whittington et al. Reference Whittington, Chatterton, Speyer, Fortey, Owens, Chang, Dean, Geyer, Jell, Laurie, Palmer, Repina, Rushton, Shergold, Clarkson, Wilmot and Kelly1997). For the protopodite in post-antennal biramous limbs of trilobites and other artiopods, the term ‘basis’ was first introduced by Ramsköld & Edgecombe (Reference Ramsköld and Edgecombe1996). However, this term implies the evolutionary hypothesis that an undivided protopodite is homologous to the basis/basipodite in a multi-segmented protopodite with other more proximal podomeres such as the coxa or precoxa (see Boxshall, Reference Boxshall2004 for discussion). The corresponding evolutionary scenario would be that the origin of other non-basal podomeres occurred by addition of proximal podomeres (e.g. Walossek & Müller, Reference Walossek, Müller, Fortey and Thomas1998; Haug et al. Reference Haug, Maas, Haug, Waloszek, Watling and Thiel2013), which rejects an alternative by the subdivision of an originally undivided protopodite podomere (see Boxshall, Reference Boxshall2004 for discussion).

4. Description of appendages

4.a. General arrangement of appendages

The appendages of a Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis holaspid consist of a single pair of uniramous antennae (an) followed by a series of homonomous post-antennal biramous limbs (Figs 1–3). The preservation of incomplete cephalic biramous limbs (Figs 4c–e, 5c, d, 6a) and three paired digestive glands (gd) on the second and third glabellar lobes and the occipital lobe (Figs 1a, 2a, 4a, b, 5a, b) suggest the presence of three corresponding pairs of post-antennal limbs underneath the cephalon (ce). Each of the 14 thoracic segments (th1–th14) bears a single pair of biramous limbs (Figs 1b–d, 2b, 3, 4e, f, 6–8), as supported by limb fragments connected to the 14th thoracic segment (unfigured fragmentary specimen HBHY008). Fragments of limbs are connected to the first and only axial ring of the pygidium (pg) (unfigured fragmentary specimen HBHY008). It is unknown whether there are limbs corresponding to the terminal axial piece of the pygidium, including the cerci. Variations in shape, if there are any, are insignificant between the post-antennal biramous limbs.

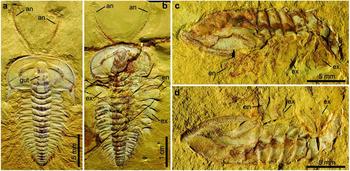

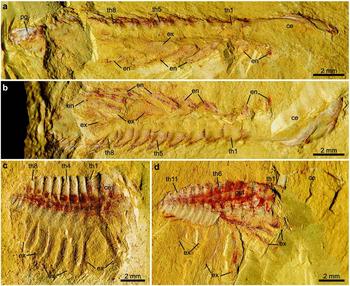

Figure 1. Complete specimens of Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis Zhang & Lin in Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Lu, Zhu, Qian, Lin, Zhou, Zhang and Yuan1980 preserved with appendages, from the Xiazhuang fossil assemblage, Kunming, Yunnan, SW China. (a) Dorsoventrally compressed normal-sized holaspid with complete antennae, part, NIGPAS 164504A. (b) Dorsoventrally compressed fully grown holaspid with complete antennae and a series of post-antennal biramous limbs, part only, NIGPAS 164503. (c, d) Laterally compressed normal-sized holaspid with a series of post-antennal biramous limbs, NIGPAS 164505. (c) Part, NIGPAS 164505A. (d) Counterpart, NIGPAS 164505B. Abbreviations: an – antenna; en – endopodite; ex – exopodite; gut – gut of digestive tract.

Figure 2. Line drawings of complete specimen of Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis Zhang & Lin in Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Lu, Zhu, Qian, Lin, Zhou, Zhang and Yuan1980 preserved with appendages, from the Xiazhuang fossil assemblage, Kunming, Yunnan, SW China. (a) Part, NIGPAS 164504A, as in Figure 1a. (b) Part, NIGPAS 164503, as in Figure 1b. Additional abbreviations: ex1–ex3 – lobes of exopodites 1–3; hyp – hypostome; gd – digestive gland; lm – lamellae; pg – pygidium; pr – protopodite; sp – spines on antennae; th1–th14 – thoracic segments 1–14; xs – setae on exopodites. Grey areas indicate digestive system.

Figure 3. Line drawings of complete specimen of Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis Zhang & Lin in Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Lu, Zhu, Qian, Lin, Zhou, Zhang and Yuan1980 preserved with appendages, from the Xiazhuang fossil assemblage, Kunming, Yunnan, SW China, NIGPAS 164505. (a) Part, NIGPAS 164505A, as in Figure 1c. (b) Counterpart, NIGPAS 164505B, as in Figure 1d. Additional abbreviations: ce – cephalon; cw – distal claws on the seventh podomere of the endopodite; ed – spinous endite; 1–7 – podomeres of the endopodite 1–7.

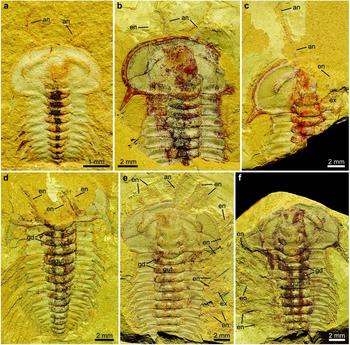

Figure 4. Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis Zhang & Lin in Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Lu, Zhu, Qian, Lin, Zhou, Zhang and Yuan1980 preserved with appendages, from the Xiazhuang fossil assemblage, Kunming, Yunnan, SW China. (a) Dorsoventrally compressed early holaspid with antennae, counterpart only, NIGPAS 164514. (b) A dorsally compressed normal-sized holaspid with antennae and post-antennal biramous limbs, counterpart only, NIGPAS 164512. (c) Dorsoventrally compressed normal-sized holaspid with antennae and post-antennal biramous limbs, part, NIGPAS 164510. (d) Dorsoventrally compressed normal-sized holaspid with antennae and post-antennal biramous limbs, part, NIGPAS 164513. (e, f) Dorsoventrally compressed normal-sized holaspid with antennae and post-antennal biramous limbs, NIGPAS 164506. (e) Counterpart, NIGPAS 164506b. (f) Part, NIGPAS 164506a. Abbreviations as in Figures 1–3.

4.b. Antennae

The paired uniramous antennae are slender and flexible (Figs 1a, b, 2a, b). Each is attached to the corresponding side of the hypostome (hyp) (Figs 1a, b, 2, 4c, e, 5d, 6a) and emerge at the anterior rim of the cephalon ventrally as in the possible life position (Figs 1a, b, 2, 4a–c, e, 5a, b, d, 6a). The lengths of complete antennae exceed ~ 50% of the cephalon's length (Figs 1a, b, 2), and the relative proportion between the antennae and the complete body length decreases from 36% (Figs 1a, 2a) to 29% (Figs 1b, 2b) from the normal-sized to fully grown holaspid periods. Individual antennae may be curved by up to 90° at their middle (Figs 4a, 5a) or terminal sections (Figs 1a, 2a). Both antennae may be stretched apart laterally with an intersection angle of up to 105° (Figs 4a, 5a).

Figure 5. Line drawings of Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis Zhang & Lin in Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Lu, Zhu, Qian, Lin, Zhou, Zhang and Yuan1980 preserved with appendages, from the Xiazhuang fossil assemblage, Kunming, Yunnan, SW China. (a) Counterpart only, NIGPAS 164514, as in Figure 4a. (b) Counterpart only, NIGPAS 164512, as in Figure 4b. (c) Part, NIGPAS 164513, as in Figure 4d. (d) Part, NIGPAS 164510, as in Figure 4c. Abbreviations as in Figures 1–3.

The antennae are composed of up to 27 rectangular podomeres in fully grown holaspids (Figs 1b, 2b), while an approximately similar number of podomeres is also found in normal-sized holaspids (Figs 1a, 2a). Although antennae are also preserved in early holaspids (Figs 4a, 5a), their maximum numbers of podomeres cannot be determined owing to the difficulties in preparation. The most proximal podomeres are evidently stouter than the distal ones (Figs 1a, b, 2, 4a–c, e, 5a, b, d, 6a, 9a). Each podomere bears at least one sharp spine (sp) close to its distal arthrodial membrane (Figs 1b, 2b, 4e, 6b, 9b). The length of the spine may reach one-third of the podomere length (Fig. 9b).

Figure 6. Line drawings of Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis Zhang & Lin in Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Lu, Zhu, Qian, Lin, Zhou, Zhang and Yuan1980 preserved with appendages, from the Xiazhuang fossil assemblage, Kunming, Yunnan, SW China. (a) Counterpart, NIGPAS 164506b, as in Figure 4e. (b) Part, NIGPAS 164506a, as in Figure 4f. Grey areas indicate digestive system. Abbreviations as in Figures 1–3.

4.c. Post-antennal limbs

Each post-antennal limb is biramous and consists of a protopodite (pt) comprising a single segment, an endopodite (en) consisting of seven segments and a tripartite exopodite (ex) (Figs 1b–d, 2b, 3, 7a, b, 8a, b, 10, 11a, g, h, 12a–d, 13). The shapes of these limbs are homonomous, but their sizes decrease correspondingly to the sizes of the thoracic segments (Figs 1b–d, 2b, 3, 4e, f, 6–8, 10). The thoracic limbs are longer and wider than the thoracic exoskeleton so that they stretch out from below the exoskeleton and are arranged in an imbricate series (Figs 1b–d, 2b, 3, 4e, f, 6–8, 10).

4.c.1. Protopodite and body–limb junction

The protopodite is robust and has a subrectangular outline, carrying the endopodite and the exopodite, respectively, at its dorsal and ventral distal margins (Figs 1b–d, 2b, 3, 10, 11a, g, h, 12a–d, 13). It is connected to the body by an arthrodial membrane (am) as the body–limb junction (Figs 7c, 8c, 11a, b, i, 12a–g, 13). The body–limb arthrodial membrane can be preserved as a section about half the width of the protopodite (Figs 11i, 12a–g, 13), or indicated by subparallel annulations (Figs 10, 11a, b). The attachment site of the protopodite to the body is the lateral side of the subrectangular to hourglass-shaped sternite (sn) (Figs 7c, 8c, 11i). Putative muscle bundles (ms) are preserved as reddish Fe-rich films along the boundary between the protopodite and the arthrodial membrane (Figs 12e, g, 13b). The protopodite extends significantly in a ventral direction, forming a stout endite (Fig. 12a–g). At least three clusters of robust spines (Figs 12a, b, e, f, 13), together with rows of non-clustered fine spines (Figs 12c, d, g, 13), develop along the ventral margin of the protopodite's endite and form a gnathobase (gs). Numerous fine setae (st) of a few hundred micrometres in length develop on the surface of the protopodite (Figs 12e, f, 13). A shallow transverse furrow is also present on the protopodite (Figs 10, 11a, b). It is most likely to be a real anatomical structure rather than a taphonomic imprint because no corresponding structures are seen on the exoskeleton.

Figure 7. Laterally compressed normal-sized holaspids of Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis Zhang & Lin in Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Lu, Zhu, Qian, Lin, Zhou, Zhang and Yuan1980 preserved with post-antennal biramous limbs, from the Xiazhuang fossil assemblage, Kunming, Yunnan, SW China. (a) Part, NIGPAS 164507a. (b) Counterpart, NIGPAS 164507b. (c) Part only, NIGPAS 164509. (d) Counterpart, NIGPAS 164511b. Abbreviations as in Figures 1–3.

Figure 8. Line drawings of laterally compressed normal-sized holaspids of Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis Zhang & Lin in Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Lu, Zhu, Qian, Lin, Zhou, Zhang and Yuan1980 preserved with post-antennal biramous limbs, from the Xiazhuang fossil assemblage, Kunming, Yunnan, SW China. (a) Part, NIGPAS 164507a, as in Figure 7a. (b) Counterpart, NIGPAS 164507b, as in Figure 7b. (c) Part only, NIGPAS 164509, as in Figure 7c. (d) Counterpart, NIGPAS 164511b, as in Figure 7d. Grey areas indicate duct-type soft tissues. Additional abbreviations: ar – anterior section of marginal rim of exopodite; dt – duct-type soft tissues; sn1–sn14 – sternite 1–14.

Figure 9. Details of antennae of Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis Zhang & Lin in Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Lu, Zhu, Qian, Lin, Zhou, Zhang and Yuan1980, from the Xiazhuang fossil assemblage, Kunming, Yunnan, SW China, part only, NIGPAS 164503, as in Figures 1b, 2b. (a) Proximal podomeres of the left antenna. (b) Middle podomeres bearing spines of the right antenna. Yellow arrows indicate arthrodial membranes between podomeres. Abbreviations as in Figures 2, 3.

Figure 10. Right thoracic post-antennal biramous limbs of Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis Zhang & Lin in Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Lu, Zhu, Qian, Lin, Zhou, Zhang and Yuan1980, from the Xiazhuang fossil assemblage, Kunming, Yunnan, SW China, part only, NIGPAS 164503, as in Figures 1b, 2b. (a) Photo. (b) Illustrative line drawing. Black and white arrows indicate the transverse and oblique joints separating the exopodite lobes. Additional abbreviations: dr – distal section of marginal rim of exopodite; pr – posterior section of marginal rim of exopodite.

Figure 11. Details of post-antennal biramous limbs of Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis Zhang & Lin in Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Lu, Zhu, Qian, Lin, Zhou, Zhang and Yuan1980, from the Xiazhuang fossil assemblage, Kunming, Yunnan, SW China. (a–d) Partial view, NIGPAS 164503. (a, b) Nearly complete fourth dextral thoracic limb, as in Figure 10a. (a) Image showing the protopodite, endopodite and exopodite. (b) Close-up of the protopodite in (a) showing an arthrodial membrane as the body–limb junction and a transverse furrow (red arrows). (c, d) Close-ups of exopodites. (c) Distal parts of exopodites of the fifth, sixth and eighth dextral thoracic limbs showing the setae along margins and the transverse joints. (d) Exopodite of the second sinistral thoracic limb, showing reddish imprints of lamellae on the exoskeleton. (e, f) Counterpart, NIGPAS 164506, close-ups of the seventh claw-bearing podomere of the endopodite, showing the arthrodial membrane between the sixth and seventh podomeres of the endopodites (yellow arrows) and the three distal claws, as in the first and second thoracic limbs of Figures 4e, 6a. (g, h) NIGPAS 164505, nearly complete thoracic limbs. (g) Part, NIGPAS 164505a, the third sinistral thoracic limb, as in Figures 1a, 3a. (h) Counterpart, NIGPAS 164505b, the sixth sinistral thoracic limb, as in Figures 1b, 3b. (i) Part only, NIGPAS 164509, close-up of the body–limb junctions, as in Figures 7c, 8c. (j) Counterpart, NIGPAS 164511b, close-up of the exopodites and duct-type soft tissues, as in Figures 7d, 8d. Black and white arrows indicate the transverse and oblique joints separating the exopodite lobes. Red arrows indicate the transverse furrow on the protopodite. Yellow arrows indicate the arthrodial membrane between the sixth and seventh podomeres of the endopodites. Abbreviations as in Figures 1–3, 8.

Figure 12. Two disarticulated post-antennal biramous limbs of Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis Zhang & Lin in Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Lu, Zhu, Qian, Lin, Zhou, Zhang and Yuan1980, from the Xiazhuang fossil assemblage, Kunming, Yunnan, SW China, NIGPAS 164508. (a, b) Limb A as part and counterpart, respectively. (c, d) Limb B as part and counterpart, respectively. (e, f) Close-ups of the protopodite of Limb A, as in (a) and (b), respectively. (g) Close-up of the protopodite of Limb B, as in (c). (h) Close-up of the distal podomeres of Limb B, as in (d). Blue and yellow arrows indicate the proximal and distal boundaries of the arthrodial membrane. Black and white arrows indicate the transverse and oblique joints separating the exopodite lobes. Abbreviations as in Figures 1–3, 8.

Figure 13. Interpretative line drawings of two disarticulated post-antennal biramous limbs of Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis Zhang & Lin in Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Lu, Zhu, Qian, Lin, Zhou, Zhang and Yuan1980, from the Xiazhuang fossil assemblage, Kunming, Yunnan, SW China, NIGPAS 164508. (a) Counterpart, NIGPAS 164508a, as in Figures 12b, d. (b) Part, NIGPAS 164508b, as in Figures 12a, c, but horizontally flipped. Abbreviations as in Figures 1–3, 8.

Figure 14. Marginal areas in the exopodites of post-antennal biramous limbs of Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis Zhang & Lin in Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Lu, Zhu, Qian, Lin, Zhou, Zhang and Yuan1980, from the Xiazhuang fossil assemblage, Kunming, Yunnan, SW China. (a, b, e–g) NIGPAS 164503. (a, b) Anterior margins of the exopodites in the third and fourth thoracic limbs, respectively. (e–g) Distal and posterior margins of the exopodites in the eighth, sixth and fifth thoracic limbs, respectively. (c, d) NIGAPS 164511b, anterior margins of the exopodites in the fifth and sixth thoracic limbs. Black arrows indicate the transverse joints separating the exopodite lobes. Abbreviations as in Figures 1–3, 8, 10.

4.c.2. Endopodite

The endopodite composed of seven podomeres is attached to the distal margin of the protopodite by an arthrodial membrane (Figs 1b–d, 2b, 3, 4e, f, 6, 7a, b, 8a, b, 10, 11a, b, g, 12a–g, 13), which is also indicated by putative oblique muscle bundles (Figs 12c, g, 13b). The total length of the endopodite accounts for ~ 80% of that of the post-antennal limb (Figs 1b–d, 2b, 3, 10, 11a, g, h, 12d, 13a). The first six podomeres are subrectangular in outline, and their sizes decrease from proximal to distal (Figs 1b–d, 2b, 3, 4c–f, 5c, d, 6, 7a, b, 8a, b, 10, 11a, g, h). Each of these six podomeres bears an endite (ed) with thin spines (Figs 1c, 3a, 12a–d, g, h, 13). Tiny reddish Fe-rich dots interpreted as the bases of setae are present on these podomeres (Figs 12b–d, g, 13). The terminal, seventh podomere is extremely short but connected to the sixth podomere by an arthrodial membrane (Figs 1c, d, 3, 4e, f, 6a, b, 7a, 8a, 11e–h, 12d, h, 13a). Three highly sclerotized sharp claws (cw), one prominent in the middle and two subordinate lateral ones, are attached to the seventh podomere (Figs 11e, f, 12d, h, 13a).

4.c.3. Exopodite

The exopodite is oblong to subrectangular in outline and composed of a tripartite flattened flap (ex1–ex3) with setae (xs) and lamellae (lm) (Figs 1b–d, 2b, 3, 7, 8, 10, 11a–d, g, h, j, 12a–d, 13). The total length of the exopodite, flap and setae included, is subequal to that of the endopodite (Figs 1b–d, 2b, 3, 10a, b, 11a, g, h, 12a, 13b). The flap is in addition ~ 50% wider than the sagittal length of the thoracic segment and almost double the maximum width of the endopodite. The exopodite flap is attached to the dorsal margin of the protopodite by an arthrodial membrane (Figs 7c, 8c, 10, 11a, b). Two joints, one transverse and the other oblique, divide the flattened flap into three parts (Figs 1b–d, 2b, 3, 4e, 6a, 7a, b, d, 8a, b, d, 10, 11a, g, h, j, 12a, c, d, 13). The transverse joint runs through about the distal third of the flap, separating the flap into a bell-shaped distal part (the third lobe, ex3) and a trapezoidal proximal part (Figs 1b–d, 2b, 3, 4e, 6a, 7a, b, d, 8a, b, d, 10, 11a, c, d, g, h, j, 12a, c, d, 13, 14). The oblique joint, which starts at the posterior end of the transverse joint and terminates at the distal end of the protopodite–exopodite junction, separates the proximal part of the flap into two subtriangular lobes (the first and second lobes, ex1 and ex2) (Figs 1b–d, 2b, 3, 4e, 6a, 7a, b, d, 8a, b, d, 10, 11a, c, d, g, h, j, 12a, c, d, 13). Up to 40 long, non-overlapping setae (xs) develop along the distal and posterior margins of the third lobe (Figs 1b–d, 2b, 3, 7a, b, 8a, b, 10, 11a, c, d, g, h, 12a, 13b, 14e–g). The maximum lengths of the setae are approximately equal to the width of the flap. Flattened imbricate lamellae (lm) develop along the posterior margin of the second lobe (Figs 1b, 2b, 10, 11c, d). They are preserved fragmentarily (Figs 1b, 2b, 10, 11c) or as imprints on the exoskeleton's surface (Figs 1b, 2b, 11d). A marginal rim runs along the margin of the flap (Figs 10, 12a–d, 13, 14). The anterior section of the marginal rim (ar) (Figs 10, 12a–d, 13, 14a–d) is generally wider than its posterior and distal sections (pr and dr) (Figs 10, 12a–d, 13, 14e–g). The anterior sections of the marginal rims of different limbs are in addition inserted by duct-type soft tissues (dt) preserved as reddish mineral films that merge into a main stem connected to the body (Figs 7d, 8d, 11j).

5. Ontogeny of antennae in Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis

The variations in the trilobite exoskeletons during ontogeny have been studied for a long time and in many taxa. However, little is known about the ontogenetic pattern of trilobite appendages (see Hughes, Reference Hughes2003, Reference Hughes2007 and references therein). The growth of antennae during the ontogeny of trilobites can be performed via two theoretical models: (1) by addition of podomeres; or (2) by stretching of individual podomeres. In order to test these growth models, the number of podomeres, total lengths of the antennae and the average lengths of the podomeres were measured and analysed statistically from our new Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis material, as well as the lengths of the cephalon as quantification of ontogenetic stage (Table 2). A significantly positive correlation (R2 = 0.9369) is found between the average length of the podomeres and the length of the cephalon (Fig. 15). Combined with the similar number of podomeres in nearly complete antennae in normal-sized and fully grown holaspids (Table 2; Figs 1a, b, 2a, b), the growth of antennae is interpreted to occur predominantly by the lengthening of individual podomeres. This may suggest that the number of podomeres increases during the meraspid stages but remains constant during the holaspid period, which is similar to the growth of thoracic segments.

Table 2. Measurements of antennae and cranidia of holaspid specimens Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis Zhang & Lin in Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Lu, Zhu, Qian, Lin, Zhou, Zhang and Yuan1980

Figure 15. Scatter plot showing significant positive correlation between the length of the cephalon and the average length of the podomeres of the antenna in Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis Zhang & Lin in Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Lu, Zhu, Qian, Lin, Zhou, Zhang and Yuan1980 holaspids from the Xiazhuang fossil assemblage, Kunming, Yunnan, SW China.

6. Comparative anatomy of trilobites and artiopods

Before discussing the evolution of euarthropod limbs and trilobite affinities, it is necessary to make comprehensive anatomical comparisons between Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis and other members of Redlichiida, Trilobita and Artiopoda. Detailed discussions organized by structure are given in the subsections below. The results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Comparative anatomy between Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis and other redlichiids, trilobites and artiopods

Note: the specific names of species are omitted for concision. Situations labelled as ‘same’ are compared with the adjacent column on the left side. The Redlichiida is represented by Eoredlichia intermedia (Hou et al. Reference Hou, Clarkson, Yang, Zhang, Wu and Yuan2008; Shu et al. Reference Shu, Geyer, Chen and Zhang1995). The Trilobita represent polymerid trilobites, excluding agnostids. See text for detailed discussions and references.

6.a. General arrangement of appendages

The appendages of Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis conform to the basic architecture of polymerid trilobite appendages, which are developed as a pair of uniramous antennae followed by a series of homonomous biramous limbs, one pair at each segment (e.g. Hughes, Reference Hughes2003; Scholtz & Edgecombe, Reference Scholtz and Edgecombe2005, Reference Scholtz and Edgecombe2006). The attachment sites of the antennae are close to the lateral margins of the hypostome in H. yiliangensis, as shown in other trilobite species (Stürmer & Bergström, Reference Stürmer and Bergström1973; Whittington, Reference Whittington1975, Reference Whittington1993; Whittington & Almond, Reference Whittington and Almond1987; Hou et al. Reference Hou, Clarkson, Yang, Zhang, Wu and Yuan2008). The number of pairs of cephalic biramous limbs posterior to the antennae in H. yiliangensis is interpreted to be three, which is consistent with the situations in other well-documented trilobite species (e.g. Hughes, Reference Hughes2003), including Eoredlichia intermedia (Hou et al. Reference Hou, Clarkson, Yang, Zhang, Wu and Yuan2008), Olenoides serratus (Whittington, Reference Whittington1975), Triarthrus eatoni (Cisne, Reference Cisne1975, Reference Cisne1981; Whittington & Almond, Reference Whittington and Almond1987), Rhenops cf. anserinus (Bartels, Briggs & Brassel, Reference Bartels, Briggs and Brassel1998) and Chotecops ferdinandi (Bruton & Haas, Reference Bruton and Haas1999). The claim of four pairs in Ceraurus pleurexanthemus (Størmer, Reference Størmer1939) or a fourth pair overlapping the cephalic/thoracic boundary in Placoparia cambriensis (Edgecombe & Ramsköld, Reference Edgecombe and Ramsköld1999) requires further research (Hughes, Reference Hughes2003; Scholtz & Edgecombe, Reference Scholtz and Edgecombe2005).

The thoracic limbs of H. yiliangensis show no significant variation in shape, similar to other trilobites (see Hughes, Reference Hughes2003, pp. 189–90 for discussions) and artiopods (e.g. Hou & Bergström, Reference Hou and Bergström1997; Ortega-Hernández, Legg & Braddy, Reference Ortega-Hernández, Legg and Braddy2013). Numerous biramous limbs with decreasing sizes are known from subisopygous and isopygous taxa as well as the micropygous T. eatoni (see Hughes, Reference Hughes2003, pp. 191–2 for discussion), the number of which considerably exceeds the number of pygidial tergites (Whittington & Almond, Reference Whittington and Almond1987). Although H. yiliangensis shows a pair of limbs belonging to the only developed axial ring in the pygidium, and two small exopodite flaps are observed extending beyond the posterior margin of pygidium in E. intermedia (Hou et al. Reference Hou, Clarkson, Yang, Zhang, Wu and Yuan2008, figs 2D, 5), the number and arrangement of pygidial limbs in the micropygous redlichiids are still uncertain.

6.b. Antennae

Like the antennae known from other trilobites, the antennae of Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis comprise numerous podomeres with spines with putative sensory function (Whittington, Reference Whittington1975, Reference Whittington1993; Bruton & Haas, Reference Bruton and Haas1999; Hou et al. Reference Hou, Clarkson, Yang, Zhang, Wu and Yuan2008). The proximal podomeres in H. yiliangensis are stouter than the distal podomeres, as seen in other trilobites (Raymond, Reference Raymond1920; Stürmer & Bergström, Reference Stürmer and Bergström1973; Whittington, Reference Whittington1975; Bergström & Brassel, Reference Bergström and Brassel1984; Whittington & Almond, Reference Whittington and Almond1987; Shu et al. Reference Shu, Geyer, Chen and Zhang1995), probably providing a stronger mechanical force in the proximal section of the antenna to create effective swinging for the distal section. The maximum number of podomeres in H. yiliangensis antennae is 27, whereas more than 40 are found in Chotecops ferdinandi (Bruton & Haas, Reference Bruton and Haas1999), 45 in Eoredlichia intermedia (Hou et al. Reference Hou, Clarkson, Yang, Zhang, Wu and Yuan2008), ~ 50 in Olenoides serratus (Whittington, Reference Whittington1975, fig. 3), > 30 in Triarthrus eatoni (Whittington & Almond, Reference Whittington and Almond1987) and ~ 30 in Palaeolenus lantenoisi (Hu et al. Reference Hu, Zhu, Luo, Steiner, Zhao, Li, Liu and Zhang2013). Thus, the numbers of podomeres in antennae are likely to vary among different trilobite species.

6.c. Post-antennal biramous limbs

The post-antennal biramous limbs of Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis are consistent with the basic architecture shown in other polymerid trilobites and artiopods, in having a protopodite composed of a single segment and an endopodite with seven segments composed of six endite-bearing podomeres and a claw-bearing terminal podomere (Fig. 16; Bergström, Reference Bergström1972; Whittington, Reference Whittington1975; Bergström & Brassel, Reference Bergström and Brassel1984; Whittington & Almond, Reference Whittington and Almond1987; Bruton & Haas, Reference Bruton and Haas1999; Hou et al. Reference Hou, Clarkson, Yang, Zhang, Wu and Yuan2008), but the exopodite is unique with its tripartite flap composition.

Figure 16. Reconstruction of paired post-antennal biramous limbs connected to sternites. Note that the structures are not in actual life positions, including the orientations of the protopodite–exopodite and body–limb junctions, but are flattened to exhibit the most detailed limb anatomy and their connections, as in the mainstream reconstructions of artiopodan limbs. The proximal lamellae are hypothetical and drawn as dashed lines, and the duct-type soft tissues are in grey. Abbreviations as in Figures 1–3, 8, 10.

6.c.1. Protopodite and body–limb junction

The coexistence of both clustered and non-clustered spines on the gnathobase of the protopodite of Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis (Fig. 16) suggests that reconstructions of gnathobases in various polymerid trilobites are possibly incomplete when they only show either clustered or non-clustered spines (e.g. Müller & Walossek, Reference Müller and Walossek1987, fig. 27). Putative muscle bundles around the arthrodial membranes of the protopodite in trilobites have not been reported in former studies and provide new information on the musculature of trilobite limbs. Fine setae that are nicely preserved on the protopodite and probably also on the endopodite are most likely to have a sensory function, as suggested in other euarthropods (e.g. Strausfeld, Reference Strausfeld2016).

The body–limb junction formed by an arthrodial membrane between the protopodite and each thoracic sternite shown in the Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis material supplements the poor record of the body–limb junction in polymerid trilobites. Although the body–limb arthrodial membrane has been shown in several Orsten stem-euarthropods (see Haug et al. Reference Haug, Maas, Haug, Waloszek, Watling and Thiel2013 and references therein), the most similar junction to the arthrodial membrane and sternite as in H. yiliangensis is best documented in the nektaspid Misszhouia longicaudata (Ramsköld et al. Reference Ramsköld, Chen, Edgecombe and Zhou1996, fig. 2; Chen, Edgecombe & Ramsköld, Reference Chen, Edgecombe and Ramsköld1997, figs 8a, 9a), where curved annulations of arthrodial membrane and hourglass-shaped sternites are also visible. No indication for either a second proximal podomere or a proximal endite is present on the protopodite of H. yiliangensis.

6.c.2. Endopodite

As in other biramous trilobite limbs, the six proximal podomeres of the endopodite have differentiated shapes, especially in their spinous endites, and show a tendency to taper from the proximal towards the distal end (Fig. 16; Bergström, Reference Bergström1972; Whittington, Reference Whittington1975; Bergström & Brassel, Reference Bergström and Brassel1984; Whittington & Almond, Reference Whittington and Almond1987; Bruton & Haas, Reference Bruton and Haas1999; Hou et al. Reference Hou, Clarkson, Yang, Zhang, Wu and Yuan2008). Rather than simply consisting of claws as indicated in other trilobite species, the seventh and terminal podomere has a short rigid base and is connected to the sixth podomere by an arthrodial membrane. Three distal claws are present, and their morphology and arrangements vary owing to the different angles of burial similar to the Hunsrück Shale species Chotecops ferdinandi (Bruton & Haas, Reference Bruton and Haas1999, text-fig. 19), whereas the three claws clearly do not merge together into a common base in H. yiliangensis. Taking into account the pyritized preservation, the common base of the claws shown in C. ferdinandi (Bruton & Haas, Reference Bruton and Haas1999, text-fig. 19) may be a taphonomic artefact.

6.c.3. Exopodite

Exopodites have been previously reported from several polymerid trilobites (Størmer, Reference Størmer1939, Reference Størmer1951; Bergström, Reference Bergström1972; Whittington, Reference Whittington1975; Whittington & Almond, Reference Whittington and Almond1987; Bruton & Haas, Reference Bruton and Haas1999; Hou et al. Reference Hou, Clarkson, Yang, Zhang, Wu and Yuan2008). The morphology of the exopodite in Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis is unique in possessing a tripartite flattened flap (Fig. 16). Although tripartite exopodite flaps are also found in several other artiopods, such as Kuamaia lata (Hou & Bergström, Reference Hou and Bergström1997), Sidneyia inexpectans (Stein, Reference Stein2013), Emeraldella brocki (Stein & Selden, Reference Stein and Selden2012) and Arthroaspis bergstroemi (Stein et al. Reference Stein, Budd, Peel and Harper2013), the flap in H. yiliangensis differs in having a transverse and an oblique joint, no sharp discontinuity of the margin at the endpoints of the joints, and lobes with subequal widths. The exopodite flap in H. yiliangensis is almost double the maximum width of the endopodite, which is distinct from those described from almost all other lobate exopodites of trilobites (Whittington, Reference Whittington1975; Bruton & Haas, Reference Bruton and Haas1999; Hou et al. Reference Hou, Clarkson, Yang, Zhang, Wu and Yuan2008) but comparable to those in K. lata (Hou & Bergström, Reference Hou and Bergström1997), Squamacula clypeata (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Han, Zhang, Liu and Shu2004), Kwanyinaspis maotianshanensis (Zhang & Shu, Reference Zhang and Shu2005) and Naraoia spinosa (Zhang, Shu & Erwin, Reference Zhang, Shu and Erwin2007) (also see Ortega-Hernández, Legg & Braddy, Reference Ortega-Hernández, Legg and Braddy2013, fig. 4 for reconstructions). These wide exopodite flaps in H. yiliangensis may be an adaptation to powerful swimming and/or a more effective respiration, with the joints possibly directing water currents. Non-overlapping setae and imbricate lamellae develop along the margins of the distal (= third) and proximal (= first) lobes of the exopodite flap in H. yiliangensis, respectively. This situation is present not only in other polymerid trilobites such as the Cambrian Stage 3 Eoredlichia intermedia (Hou et al. Reference Hou, Clarkson, Yang, Zhang, Wu and Yuan2008) and the Cambrian Stage 5 Olenoides serratus (Whittington, Reference Whittington1975), but also in a number of non-trilobite artiopods (see Zhang, Shu & Erwin, Reference Zhang, Shu and Erwin2007; Ortega-Hernández, Legg & Braddy, Reference Ortega-Hernández, Legg and Braddy2013; Stein et al. Reference Stein, Budd, Peel and Harper2013 and references therein). Despite the limited knowledge, the overall similarity between the exopodites of O. serratus (Order Corynexochida; Whittington, Reference Whittington1975) and E. intermedia (Order Redlichiida; Hou et al. Reference Hou, Clarkson, Yang, Zhang, Wu and Yuan2008) as well as the differences between the almost contemporaneous E. intermedia and H. yiliangensis (Order Redlichiida) suggests that these anatomical variations are more likely the results of divergence owing to different ecological adaptations of the species rather than the different evolutionary tendencies of trilobite orders.

The exopodite flaps in Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis exhibit duct-type soft tissues (Fig. 16). These tissues of the different limbs further merge into a main stem in the ventral soft parts of the body. The morphology and positions of these duct-type structures are comparable to those ‘invasive caeca’ or ‘triangular strips’ in a range of stem-group euarthropods from the Burgess Shale (see Aria & Caron, Reference Aria and Caron2015, figs 2, 3, 5, 9). A digestive nature was suggested for those from the Burgess Shale because they are connected to the main alimentary canal (Aria & Caron, Reference Aria and Caron2015). However, the duct-type structures here may be different tissues, since no connection to the gut is observable. Because exopodites have long been interpreted as respiratory organs like gills (e.g. Hou & Bergström, Reference Hou and Bergström1997), a putative circulatory nature for these duct-type structures is proposed here. Still, further investigations are required to clarify these alternative possibilities.

6.d. Basic appendage morphology of trilobites and artiopods

By discussing comparative anatomy under the light of the new Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis appendages above, we can conclude in general that all trilobites and other artiopods share the same basic architecture of appendages comprising a pair of deutocerebral/hypostomal uniramous antennae and a series of paired homonomous biramous limbs (e.g. Hughes, Reference Hughes2003; Scholtz & Edgecombe, Reference Scholtz and Edgecombe2005, Reference Scholtz and Edgecombe2006). However, within ascending systematic hierarchies from Redlichiida, Trilobita to Artiopoda, their biramous limbs show a conserved morphology by consisting of seven podomeres in the endopodites and one single segment in the protopodite, but also considerable morphological disparity in the composition of the exopodites.

7. Affinities of trilobites: mandibulate or chelicerate?

Three alternative affinities for trilobites and other artiopods have been hypothesized: as stem-chelicerates, stem-mandibulates or a stem lineage of both Chelicerata and Mandibulata (Budd & Telford, Reference Budd and Telford2009). Comparisons between major upper stem-group euarthropods and the stem and crown groups of Mandibulata and Chelicerata can reveal general evolutionary trends of euarthropod appendages in two aspects, i.e. the arrangement of appendages along the anterior–posterior main body axis, and the composition of limb rami. These trends can be essential for interpreting the affinities of trilobites and artiopods, which are discussed below and summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. General comparisons of appendage arrangements and compositions of biramous limbs between upper stem groups of euarthropods, mandibulates (represented by crustaceans) and chelicerates

Note: in crown-group euarthropods, it is difficult to distinguish the protopodite and endopodite in post-antennal uniramous limbs, and that secondary resegmentation may generate more than seven podomeres in endopodites (Boxshall, Reference Boxshall2004, Reference Boxshall, Minelli, Boxshall and Fusco2013). See Briggs et al. (Reference Briggs, Siveter, Siveter, Sutton, Garwood and Legg2012) for anatomy of Dibasterium and revisions on Offacolus. Also note that whether chelicerate gills are epipodites or exopodites is open to question. See text for detailed discussions and references.

7.a. Arrangement of appendages

Considering the anteriormost (deutocerebral and tritocerebral) appendages, within upper stem-group euarthropods, trilobites and other artiopods are unique in lacking any specialized cephalic feeding appendages (Table 4), such as the tritocerebral specialized post-antennal appendages (SPAs) in large ‘bivalved’ stem-euarthropods (e.g. Legg et al. Reference Legg, Sutton, Edgecombe and Caron2012) and fuxianhuiids (e.g. Yang et al. Reference Yang, Ortega-Hernández, Butterfield and Zhang2013), and the deutocerebral short great appendages (SGAs) in megacheirans (e.g. Tanaka et al. Reference Tanaka, Hou, Ma, Edgecombe and Strausfeld2013). Nevertheless, they share the multi-segmented deutocerebral ‘secondary antennae’ with large ‘bivalved’ stem-euarthropods (e.g. Legg et al. Reference Legg, Sutton, Edgecombe and Caron2012), fuxianhuiids (e.g. Yang et al. Reference Yang, Ortega-Hernández, Butterfield and Zhang2013) and mandibulates (Scholtz & Edgecombe, Reference Scholtz and Edgecombe2005, Reference Scholtz and Edgecombe2006). In megacheirans and chelicerates, however, neither the SGAs nor the chelicerae are antenniform but raptorial, and consist of a limited number of podomeres (Chen, Waloszek & Maas, Reference Chen, Waloszek and Maas2004). Therefore, the ‘secondary antennae’ have been regarded as strong evidence supporting the mandibulate affinities of trilobites and other artiopods (Scholtz & Edgecombe, Reference Scholtz and Edgecombe2005, Reference Scholtz and Edgecombe2006).

On other hand, all post-tritocerebral limbs are homonomous on both the cephalon and trunk of all the upper stem-group euarthropods mentioned above (e.g. Legg et al. Reference Legg, Sutton, Edgecombe and Caron2012; Ortega-Hernández, Legg & Braddy, Reference Ortega-Hernández, Legg and Braddy2013; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Ortega-Hernández, Butterfield and Zhang2013; Aria, Caron & Gaines, Reference Aria, Caron and Gaines2015). In Mandibulata, although several anterior post-tritocerebral limbs are specialized for feeding and the rest can show various degrees of differentiation or tagmatization, continuous series of undifferentiated homonomous limbs are typically present on the trunk of myriapods and some crustaceans such as Anostraca and Remipedia. By contrast, in Chelicerata (except for pycnogonids), post-tritocerebral limbs on the anterior and posterior body tagma (prosoma and opisthosoma) are always differentiated. In Xiphosura, the post-tritocerebral limbs of the anterior and posterior tagma are differentiated into uniramous legs (except for the last leg with flabellum) and gills, respectively, whereas the posterior limbs have been reduced in other chelicerate crown groups. Therefore, the homonomous pattern of limbs shown in trilobites, artiopods and other upper stem-group euarthropods has been retained in Mandibulata, but was lost by the basic anterior and posterior tagmatization in Chelicerata, providing further evidence supporting the mandibulate concept.

7.b. Biramous limbs

Trilobites and other artiopods are also distinguished by the composition of their post-antennal biramous limbs. Despite that all of these limbs in the upper stem groups of Euarthropoda mentioned above are homonomous, the basic compositions of their endopodites and exopodites are different (Table 4). In fuxianhuiids (e.g. Yang et al. Reference Yang, Ortega-Hernández, Butterfield and Zhang2013) and large ‘bivalved’ stem-euarthropods (e.g. Legg et al. Reference Legg, Sutton, Edgecombe and Caron2012), the podomeres of the endopodites show no differentiation in shape and their number exceeds ten, and their exopodites are undivided flaps. In megacheirans (e.g. Aria, Caron & Gaines, Reference Aria, Caron and Gaines2015), endopodite podomeres are also undifferentiated and are at least eight in number (including the distal claw), whereas their exopodites are flaps comprising two lobes. It is worth noting that the morphology of the exopodites is consistent in each of these groups, whereas the number of their endopodite podomeres varies. This indicates that the exopodites are more morphologically conserved than the endopodites in these upper stem-euarthropod groups. In trilobites and other artiopods, however, endopodites and exopodites exhibit different patterns of morphological disparity. For the endopodites, the number of podomeres is consistently seven (including distal claws) and the morphological differences of the podomeres are geometric rather than qualitative in trilobites and other artiopods with a few questionable exceptions. By contrast, the exopodites vary in composition between any two trilobite and artiopodan species. Their exopodites can be a flap comprising one to three lobes, or a shaft, showing a high morphological disparity. Within the two modern euarthropod lineages Mandibulata and Chelicerata, this similar disparity of the exopodites is only exhibited in stem-group and crown-group crustaceans, whereas the exopodites have been reduced or lost in Chelicerata.

Developmental biology has shown that endopodites and exopodites are rami originating from the same main proximal–distal axis of the biramous limb bud (Wolff & Scholtz, Reference Wolff and Scholtz2008). However, the striking distinction in patterns of disparity between the endopodites and exopodites seen in stem-euarthropods suggests that their developmental regulatory machineries diverged early in the evolution of euarthropod biramous limbs (Davidson & Erwin, Reference Davidson and Erwin2006). In trilobites, other artiopods and crustaceans, the developmental genetic regulatory programmes were relatively conserved in the endopodites, whereas they were much more flexible in the exopodites. Nevertheless, the situations are reversed in large ‘bivalved’ stem-euarthropods, fuxianhuiids and megacheirans, with higher conservativeness in the exopodites than in the endopodites. The chelicerate concept would thus require abandoning the highly evolved developmental machinery of the exopodites, which is an unlikely case.

Therefore, from a developmental perspective, the pattern of morphological disparity shown by the two rami also supports the mandibulate affinities of trilobites and other artiopods.

7.c. Evolutionary trends of euarthropod appendages

Most recent morphological and molecular phylogenetic frameworks of Euarthopoda have, respectively, revealed a successive appearance of euarthropod characters in upper stem groups from ‘bivalved’ stem-euarthropods, fuxianhuiids, megacheirans to artiopods, and the relationships of crown groups such as Chelicerata + Mandibulata (Myriapoda + Tetraconata/Pancrustacea) (e.g. Edgecombe & Legg, Reference Edgecombe and Legg2014). Within the upper stem groups, the early evolution of euarthropod appendages has undergone the origination of deutocerebral (antennae, SGAs) and tritocerebral (SPAs) specialized appendages (Edgecombe & Legg, Reference Edgecombe and Legg2014), reduction in the number of endopodite podomeres from more than ten to the ground plan of seven, and differentiation of endopodite podomeres (Boxshall, Reference Boxshall2004, Reference Boxshall, Minelli, Boxshall and Fusco2013). However, the subdivision of the protopodite, and the differentiation or specialization of post-tritocerebral or trunk appendages should occur during the early evolution of Mandibulata and Chelicerata (Boxshall, Reference Boxshall2004, Reference Boxshall, Minelli, Boxshall and Fusco2013).

7.d. Affinities of trilobites and artiopods

The chelicerate affinity hypothesis for trilobites and artiopods had been the mainstream for a long time until new evidence for mandibulate affinities and conflicts with the chelicerate concept were put forward by Scholtz & Edgecombe (Reference Scholtz and Edgecombe2005, Reference Scholtz and Edgecombe2006). However, controversies have still been going on since then, as both the mandibulate and chelicerate concepts gained support from different recent phylogenetic analyses (e.g. Ortega-Hernández, Legg & Braddy, Reference Ortega-Hernández, Legg and Braddy2013; Legg, Sutton & Edgecombe, Reference Legg, Sutton and Edgecombe2013). The evidence given by Scholtz & Edgecombe (Reference Scholtz and Edgecombe2005, Reference Scholtz and Edgecombe2006), including the ‘second antennae’ and head segmentation, together with our new arguments based on the homonomous pattern and composition of the biramous limbs, supports the mandibulate concept of trilobites and at least some artiopods. Meanwhile, this evidence proposes the critical character transformations that are required to fit the chelicerate concept, including the loss of antennae, disappearance of delimited cephalon–trunk tagmatization, change of limb patterning along the main body axis and reorganization of developmental machineries in the limb rami. However, we cannot negate the possibility that with new data, some members of the current Artiopoda definition may be closer to the chelicerate lineage. If this is true, subdivision of artiopods would be essential.

8. Conclusion

The appendages of Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis reinforce the idea that polymerid trilobites share a homonomous arrangement of biramous limbs as well as conserved anatomy in the protopodites and endopodites, but have significant inter-taxa differences in the exopodites. This appendage architecture of trilobites is highly comparable to that of other artiopods. Ontogeny of trilobite antennae is studied for the first time and shows a growth model of lengthening each podomere. By reinvestigating and comparing appendages in upper stem groups and crown groups of Euarthropoda, we show similarities in the arrangement of homonomous limbs and patterns of morphological disparity in the endopodites and exopodites between artiopods (including trilobites) and mandibulates. Together with the shared ‘secondary antennae’ and head tagmosis, these new lines of evidence further support the mandibulate affinities of trilobites and at least some artiopods. However, more data on the appendages of trilobites and other stem-group euarthropods are still essential to resolve controversies surrounding the problem of trilobite affinities.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to G. Geyer, a referee abbreviated as GREE and an anonymous referee for their constructive comments and suggestions, N.C. Hughes and L.E. Babcock for helpful discussion on soft anatomy, J.-L. Yuan for discussions on the exoskeleton and biostratigraphy and Mr. Chen Qingtao for field assistance. This work was supported by the National Basic Research Programme of China (2013CB835006); the Strategic Priority Research Program (B) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB18030304); the National Natural Science Foundation of China; and the China Scholarship Council.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756817000279