On April 25, 2015, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake struck Nepal at 11:56 am local time. Its epicenter was in the Lamjung district, 77 km west of Kathmandu. Another 7.3 magnitude earthquake struck Nepal again on May 12, 2015, at 12:50 am local time.1 These massive earthquakes killed nearly 9000 and injured 22,500 people.2 Various international agencies have played key roles in assisting the survivors. The procedures associated with international medical assistance have been dramatically changing since 2013. The World Health Organization (WHO) Foreign Medical Team Working Group under the Global Health Cluster has published a blue book Classification and Minimum Standards for Foreign Medical Teams in Sudden Onset Disaster through the WHO in 2013. This book describes the classification and minimum standards that the medical teams, especially those coming from foreign countries have to follow. The same working group also launched an on-site medical team coordination mechanism. This coordination mechanism was tested during the Philippines cyclone disaster and the Ebola virus outbreak in Africa. The Nepal earthquakes of 2015 were the first time that this coordination mechanism was applied on a large-scale.

The purpose of this research is to evaluate this approach for the coordination among the emergency medical teams (EMTs) that responded to the Nepal earthquake in April 2015. In this report, the term EMT refers to all types and organizations of the medical team, including private sector, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), Red Cross, and military medical teams, as well as local medical team.

METHODS

This was a retrospective, descriptive study.

Participant Observation Method

We participated in the EMT coordination process as observers while responding to the Nepal earthquake as members of the Japan Disaster Relief Medical Team, using our experience with deployment.

Secondary Data Review

Primary and secondary data were collected by the Emergency Medical Team Coordination Cell (EMTCC)/Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) of Nepal. They were compiled into a single database on the EMTs that responded to the Nepal earthquake 2015.

Online Feedback Survey

The EMTCC/MoHP conducted an online feedback survey twice. The initial feedback survey was conducted from early June to September 2015 using Google forms®. The initial target was government medical teams. The second survey used Survey Monkey® and was conducted from September to December 2015 for all registered EMTs without duplication of organizations. Questionnaires were distributed to all the registered EMTs through email. The 2 surveys consisted of 38 and 44 questions, respectively. The second survey had 6 additional questions added to the front sheet. The questionnaires focused on EMT coordination, particularly the timeline of the process. The included questions were on (1) before leaving own country and registration, (2) coordination and tasking, (3) deployment and logistics, (4) communication with EMTCC/District Health Office (DHO), (5) reporting system and communication, and (6) demobilization. The secondary mapping product was reviewed, and Geographic Information System (GIS) maps were created from the EMT database.

This survey was not directly supported by the WHO.

Ethical Review

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the MoHP of Nepal.

RESULTS

Participant Observation

The process started with a preregistration phase. The EMTs were managed more systematically than in the past, such as with the Haiti earthquake in 2010, when no public announcements were made regarding requirements for EMTs. This time, the WHO announced on their information platform website, Virtual On-Site Operations Coordination Center (VO) that “WHO and the Ministry of Health and Population of Nepal are working together to assess the need for foreign medical teams (FMTs). Offers from Types 1, 2, and 3 fully self-sufficient teams are welcome, but the final acceptance will be the decision of the Government of Nepal. The FMTs considering participating should fill the registration form attached, and send to the WHO points of contact. Initial coordination of FMTs, if required and accepted, will use the Reception and Departure Centre (RDC) and the On-Site Operations Coordination Centre (OSOCC) methodology on arrival, until formal health coordination is established under the Ministry mechanisms or the cluster when this is decided.” This announcement was posted on April 27, 2015, 2 days after the earthquake. The virtual OSOCC (https://vosocc.unocha.org/) is a closed website for professional responders who recognized by United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). The term FMT was changed to EMT in 2016.

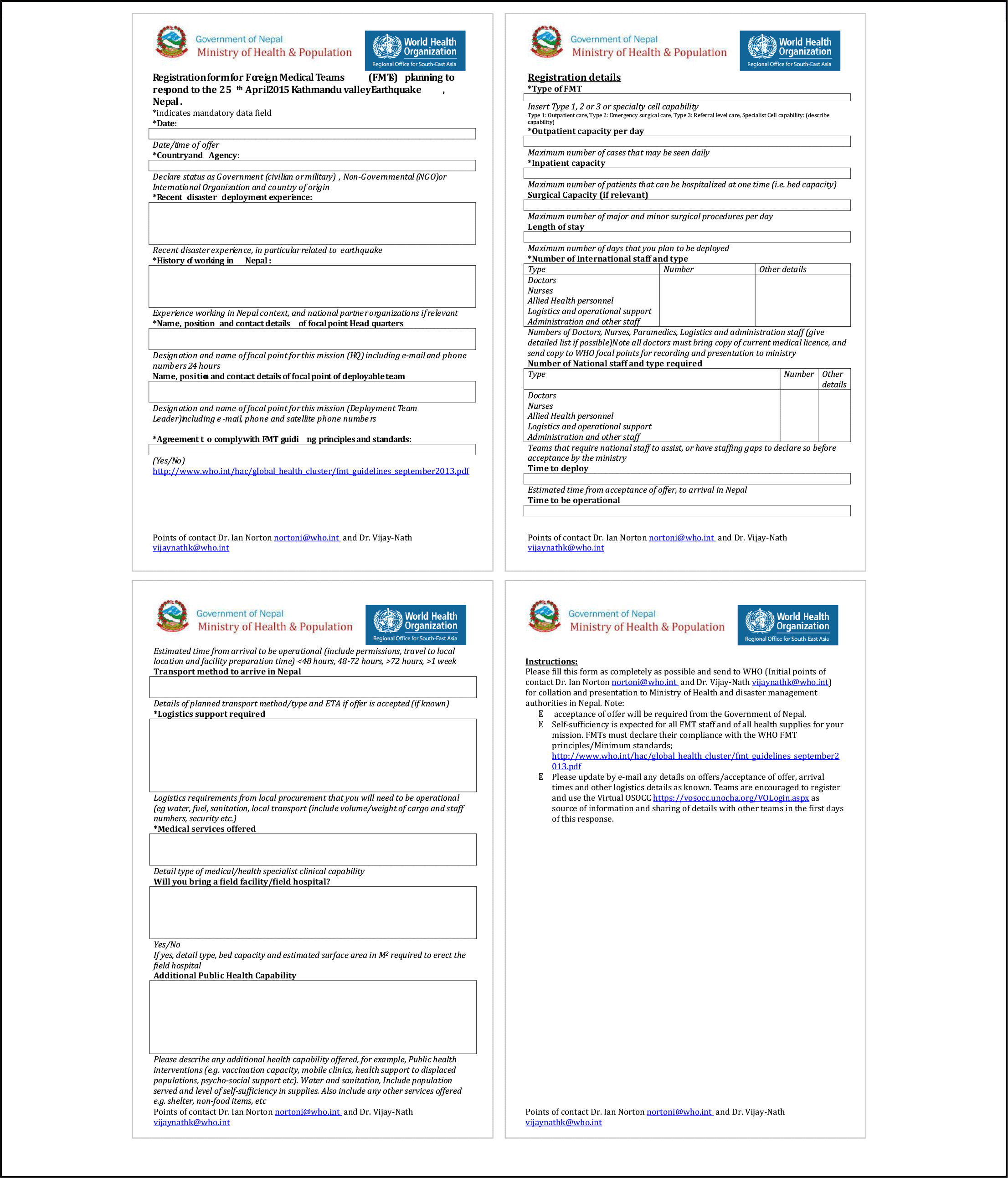

Because there were no standardized registration forms available, the MoHP drafted an EMT registration form in collaboration with the WHO (Figure 1). The registration form was more detailed than the ones used for previous events, such as the tropical cyclone in the Philippines in 2013 (Figure 2). At the same time, WHO prepared an online registration system on their website, which has since been moved or deleted. Additionally, there were several on-site registration points in Nepal. The first point was the RDC, which was run by the United Nations Disaster Assessment and Coordination (UNDAC) team and the OCHA.

FIGURE 1 FMT Registration Form Nepal 2015.

FIGURE 2 FMT Sheet Philippines 2013.

Strictly speaking, the role of the RDC was to just “record” all the incoming disaster relief teams, including the medical teams, and refer them to the EMTCC/MoHP registration.3 They did not use a consolidated registration form, but instead used various team information forms as shown in Figure 1, and put the data into their personal computer directly. The medical license screening and registration were taken care of by the MoHP. Both the second and third on-site registration points were on the property of the MoHP. The Health Emergency Operation Center was located on the MoHP premises, and the EMTCC was located in the building next to the MoHP. The military medical teams were registered at the Multi-National Military Coordination Centre (MNMCC). There were various channels for keeping track of the EMTs, although there were no standard licensing and accreditation procedures for the FMTs.

The selected government EMTs were informed through a previous official communication from the MoHP by email and were approved to provide medical services when they arrived in Nepal. On the other hand, the private medical teams, such as NGOs, were required to submit a copy of the passports of the team members, together with a copy of their professional medical license, a covering letter to the Ministry expressing their interest in providing services, and the completed registration form. After obtaining permission, they were approved to work as health professionals for 30 days.

The Nepal government immediately provided medical services by means of its military resources including foreign military units. Therefore, the initial EMT coordination was done by the MNMCC/Ministry of Defence.3 When the civilian medical teams arrived, the EMT coordination and tasking mechanism integrated into a single unit at the EMTCC/MoHP. Three officers from the WHO, the MoHP, and the Ministry of Defense sat at the same table and worked together at the EMT coordination meeting. These meetings were held every day in the beginning and then twice a week on Mondays and Thursdays at the MoHP. The fifth day after the earthquake, when there were enough EMTs, the MoHP announced a stand-down message and stopped accepting new applications.

Following the registration was the monitoring phase. Both the EMTCC/MoHP requested the EMTs to report daily and weekly using a provided format. This announcement was released through the EMT coordination meeting, VO and EMT mailing list. The EMTCC monitored the medical needs through the reported data.

Next was the demobilization phase wherein the MoHP provided an exit form. This form was used for the second time in Nepal, the first being after the tropical cyclone Pam in Vanuatu in 2015.

The EMTCC was assisted by the MoHP staff, members of the UNDAC team from OCHA, International Humanitarian Partnership (IHP), and volunteers from the Japan Disaster Relief Medical team (Japan), Germany, and India Red Cross.

Database Analysis

A total of 150 EMTs were recorded with the EMTCC, and 137 of them were given tasks. Of these 150 recorded EMTs, 100 were Type 1, which included 29 Type 1-Mobile and 71 Type 1-Fixed. Of the Type 1 EMTs, 80% were NGOs. Type 2 was made up of 22 EMTs, and 4 of the 7 NGOs involved came from the Red Cross. The only Type 3 team was from Israel. At that time, the Israel defense force team was the first team to qualify as Type 3 based on the WHO criteria. Twenty-seven teams were categorized as specialist cells (Table 1). The 137 teams that were given tasks included 25 government EMTs, 16 military EMTs, and 96 NGO/private sectoral EMTs.

TABLE 1 Type of Organizations and the Registered EMTs

Over half of all the EMTs were registered at the MoHP. Most of the military EMTs were registered at the MNMCC. There was some duplication of registration (Tables 2 and 3).

TABLE 2 Registration Points and Number of Registered Organizations

TABLE 3 Breakdown of EMT Types and Registration Points

Online Feedback Survey

The EMTCC created an integrated contact list for the feedback survey that included 172 individual email addresses identifying 34 organizations based on the domain address analysis. Eighteen of the 172 contacts were rejected due to a DNS (domain name system) error or an earlier response to the initial survey. Finally, the EMTCC had 154 available contacts, which was approximately the same as the number of registered EMTs in the EMTCC. The EMTCC received 30 responses, including those following the initial survey (return rate of 19.5%), despite a reminder mail that was sent. A response rate of < 20% significantly weakened the findings.

A GIS Map of EMT Distribution

While the MoHP distributed EMTs based on the number of victims and the WHO EMT classification (Figures 3 and 4)6 , 7, it allocated the EMTs based on the “hub-and-spoke” model. The strategic location for each hub was chosen based on previously existing health facilities or areas with trauma load. The Type 3 EMTs providing tertiary level medical services were allocated to a central location in the affected area/country. Type 2 EMTs were allocated around Type 3 EMTs. The smaller Type 1-Fixed or Type 1-Mobile EMTs were dispatched to more remote areas to treat trauma cases or to refer cases to a higher level of care.

FIGURE 3 Reported Deaths in Nepal Earthquake 2015.

FIGURE 4 Nepal Earthquake Emergency Medical Team Locations.

DISCUSSION

Coordination Process

The MoHP initiated prior registration of EMTs by means of e-mail and then reviewed the offers to ensure that they met the humanitarian needs, before granting access. Although this was an outdated method with a complicated data handling system, it was effective under the given conditions and helped in speeding up the planning of the initial EMT allocations. Acceptance of international assistance, especially medical teams, has political implications. As donors, the international EMTs should respect the affected country’s sovereignty, and follow their registration methods.

Most important was the selection process to choose international EMTs. Although the government of the affected country can send away nonapproved EMTs, the multiple registration points (MNMCC, MoHP, and WHO) helped in avoiding large numbers of nonregistered EMTs. However, from the standpoint of the EMTs, the affected country authority/WHO should consider a more straightforward and user-friendly registration mechanism, such as a “one-stop-shop.” In the case of Nepal, the EMT coordination meetings were run by the MoHP and WHO. The Nepal Army attended the EMT coordination meetings several times and shared relevant EMT information with other civil EMTs. There was no information gap between the civil and military EMTs in Nepal. The only problem was due to the poor communication network in the mountainous area. Collecting the daily reports from EMTs in rural areas with limited infrastructure was a substantial challenge. Through the Nepal experience, it has become clear that information management plays a crucial role in providing good coordination and support for the victims. To do that, the WHO should provide adequate training in information management at the EMTCC.

Deployment of International EMTs

The EMTCC recorded 150 EMTs, including military teams from various areas. This number is almost the same as what seen during the Philippines cyclone experience in 2013 (Table 4).Reference Peiris, Buenaventura and Zagaria4 These data suggest that any affected government is likely to receive over 100 offers of medical assistance. For this reason, the government should have a prior national strategy for receiving medical assistance.

TABLE 4 Comparison of the Number of International EMTs in Philippines and Nepal

The EMT global registration system with minimum standards has started since 2016, and over 40 government requested peer review and verification of the quality of their teams.3 The WHO verified 22 EMTs as of February 2019.5 One of the aims of a global EMT registry is to speed up the deployment process of international medical assistance to address trauma load in the affected country. However, it is possible that the number of acceptable EMTs will decrease because affected governments have an option to refuse non-WHO classified EMTs. In contrast, over 75 EMTs that demonstrated an interest in the global registry are currently undergoing the verification process. The situation of international EMT deployment is in transition.

Limitations of the Study

This study has several limitations. First, is the lack of national EMT data. This survey focused on international EMTs because the EMTCC is supporting the MoHP for the coordination of international EMTs. Furthermore, the national EMTs did not coordinate at the same place as the international EMTs. That is one of the reasons for lacking the national EMT data. Second, is participant observation. It is challenging to participate alone at all coordination opportunities from airport to meeting room and on-site. Therefore, a result of the participant observation may include a missing fact. The third was data sharing between the WHO and MoHP. The survey team was not able to get EMTs data from WHO. Therefore, the number of EMTs and a breakdown of the EMT types were different from what the WHO reported previously.

CONCLUSIONS

Nepal was hit by a massive earthquake in 2015. The EMTCC was established under the MoHP with support from the WHO. The EMT classification established by the WHO contributed to the planning and allocation of EMTs. However, the method of onsite registration at multiple locations needs improvement. Good information management is critical for effective EMT coordination. Training in information management at the EMTCC to establish a sustainable mechanism for information collected during the operation phase is an absolute requirement.

Acknowledgments

Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Funding

This study was funded with a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI. The grant number is JP15H05793.