The early environment, starting in utero, can represent major risk factors for a lifetime of physical, psychiatric, and neurological problems for the individual (Braun et al., Reference Braun, Bock, Wainstock, Matas, Gaisler-Salomon, Fegert and Segal2017; Gluckman, Hanson, Cooper, & Thornburg Reference Gluckman, Hanson, Cooper and Thornburg2008; Hanson & Gluckman, Reference Hanson and Gluckman2011; Howard, Molyneaux, et al., Reference Howard, Molyneaux, Dennis, Rochat, Stein and Milgrom2014; Seckl, Reference Seckl, De Kloet, Oitzl and Vermetten2007; Van den Bergh, Reference Van den Bergh2011; Van den Bergh et al., Reference Van den Bergh, van den Heuvel, Lahti, Braeken, de Rooij, Entringer and Schwab2017). While according to DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), neurodevelopmental disorders are a group of disorders whose onset and clinical expression occur in childhood (Thapar, Cooper, & Rutter, Reference Thapar, Cooper and Rutter2017), other psychiatric disorders are now being considered within the context of a neurodevelopmental disorder, even if their onset occurs in adolescence or adulthood (Deoni et al., Reference Deoni, Zinkstok, Daly, Ecker, Williams and Murphy2014; Meredith, Reference Meredith2015; Thomason et al., Reference Thomason, Grove, Lozon, Vila, Ye, Nye and Romero2015).

Since its inception, the field of developmental psychopathology has emphasized the dynamic and complex interactions between an individual and its developmental environment in shaping almost all forms of psychopathology (Cicchetti & Rogosch, Reference Cicchetti and Rogosch1996; Hyde, Reference Hyde2015; Sroufe & Rutter, Reference Sroufe and Rutter1984). For instance, an important tenet of the developmental psychopathology perspective is that early life adversity may provide serious challenges to the species-typical organism–environment “coactions” that play important roles in the emergences and timing of normal developmental change (Cicchetti, Handley, & Rogosch, Reference Cicchetti, Handley and Rogosch2015, p. 553). The developmental origins of health and disease research field also adopts the developmental plasticity idea and extends it up into the prenatal life period. Initially a lowered birth weight was taken as a proxy measure of prenatal environmental exposure in most studies. A lowered birth weight was shown to be a risk factor for the development of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases such as arterial hypertension, coronary heart disease, obesity, and type 2 diabetes (Barker, Reference Barker1990) as well as mental health problems such as depression (Thompson, Syddall, Rodin, Omond, & Barker, Reference Thompson, Syddall, Rodin, Omond and Barker2001) and schizophrenia (Rifkin, Lewis, Jones, Toone, & Murray, Reference Rifkin, Lewis, Jones, Toone and Murray1994) Although much less examined, accumulating evidence mostly gathered during the last decade is now revealing prenatal environmental exposure effects on early brain and behavior development in humans. The developmental origins of behavior, health, and disease has recently been proposed (Van den Bergh, Reference Van den Bergh2011), and examples of its empirical testing have been described (Van den Bergh, Reference Van den Bergh, Reissland and Kisilevsky2016). It is generally accepted that behavioral problems, neurodevelopmental issues, and psychiatric disorders are driven by atypical brain functions, which in turn reflect alterations in underlying brain structure and circuitry (van Essen & Barch, Reference van Essen and Barch2015). It is now also being accepted that these alterations may have their origin in the earliest periods of brain development. It is an important aim of our paper to reveal important new insights gained from this growing field of research; we particularly focus on new findings from research in humans.

Many authors point explicitly to the role of maternal stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms (Bowers & Yehuda, Reference Bowers and Yehuda2016; Kofink, Boks, Timmers, & Kas, Reference Kofink, Boks, Timmers and Kas2013; Lewis, Galbally, Gannon, & Symeonides, Reference Lewis, Galbally, Gannon and Symeonides2014; O'Connor, Monk, & Fitelson, Reference O'Connor, Monk and Fitelson2014; Van den Bergh et al., Reference Van den Bergh, Mennes, Oosterlaan, Stevens, Stiers, Marcoen and Lagae2005) and maternal mental illness during pregnancy (Howard, Molyneaux, et al., Reference Howard, Molyneaux, Dennis, Rochat, Stein and Milgrom2014; Jones, Chandra, Dazzan, & Howard, Reference Jones, Chandra, Dazzan and Howard2014; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Pearson, Goodman, Rapa, Rahman, McCallum and Pariante2014) as risk factors that may lead to functional and structural brain changes in the offspring (Charil, Laplante, Vaillancourt, & King, Reference Charil, Laplante, Vaillancourt and King2010; Franke et al., Reference Franke, Van den Bergh, de Rooij, Nathanielsz, Witte, Roseboom and Schwab2017; Scheinost, Sinha, et al., Reference Scheinost, Sinha, Cross, Kwon, Sze, Constable and Ment2016; Van den Bergh et al., Reference Van den Bergh, van den Heuvel, Lahti, Braeken, de Rooij, Entringer and Schwab2017). In these review papers, offspring brain alterations are seen as mediating the link between prenatal exposure to maternal distress, and offspring behavioral, cognitive, and emotional development and susceptibility to neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders. Functional and structural brain measures of their regional connectivity may be seen as putative footprints or biomarkers of prenatal stress, altering risk or resilience for neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders. Maternal psychological distress in the studies reviewed refers to (a) general or pregnancy-specific anxiety, and depressive symptoms; (b) major life events experienced by the mother (such as illnesses or deaths in the close family, financial and relationship problems, house moves, car accident, etc.); (c) a psychiatric diagnosis of a current or past anxiety or depression disorder; and (d) exposure to a disaster (maternal hardship due to a natural disaster) and the subjective distress and cognitive appraisal related to it. Maternal distress is measured with one of the following methods: (a) self-report distress and/or life events questionnaire, (b) a physician's diagnosis based on medical chart information or on a diagnostic psychiatric instrument, and/or (c) a physiological variable (such as cortisol).

Before reviewing studies on potential brain biomarkers of prenatal stress, we provide a short overview of brain imaging techniques and analysis methods. In the next section, we describe new insights into functional genomics and into a typical developmental trajectory of the human brain. We focus on recent neuroimaging studies and on studies starting from computational stimulation models that enable researchers to quantify the critical physical phenomena that are necessary to induce folding and predict gyral wavelength and gyrification indices. Next, we present human prenatal stress studies that have explicitly examined alteration in offspring brain development and share knowledge about the putative prenatal origins of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders. Finally, we present ways in which future research may contribute to further mechanistic understanding of how prenatal stress exposure may lead to aberrant brain circuitry and describe clinical and societal responsibilities associated with prenatal stress.

The Developing Brain: Imaging Techniques and Analysis Methods

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allows a variety of protocols with different contrasts to investigate structural (sMRI), functional (fMRI), and diffusion (dMRI) specific in vivo properties of the brain by means of volume-, surface-, deformation-, or regions-wise analysis (Ashburner & Friston, Reference Ashburner and Friston2000; Fischl, Reference Fischl2012; Gaser, Nenadic, Buchsbaum, Hazlett, & Buchsbaum, Reference Gaser, Nenadic, Buchsbaum, Hazlett and Buchsbaum2001). Given its noninvasive nature, MRI allows characterizing the human brain across the life span (see also the developing human connectome project at http://www.developingconnectome.org) ranging from in utero (e.g.,Thomason et al., Reference Thomason, Grove, Lozon, Vila, Ye, Nye and Romero2015) and longitudinal imaging, (e.g., Li, Nie, et al., Reference Li, Nie, Wang, Shi, Lyall, Lin and Shen2014; Mills & Tamnes, Reference Mills and Tamnes2014) to postmortem acquisitions (e.g., Kostović et al., Reference Kostović, Jovanov-Milošević, Radoš, Sedmak, Benjak, Kostović-Srzentić and Judaš2014; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Stagg, Douaud, Jbabdi, Smith, Behrens and McNab2011). Accordingly, MRI-based investigations have provided great contributions to our understanding of both typical and atypical brain structure and function.

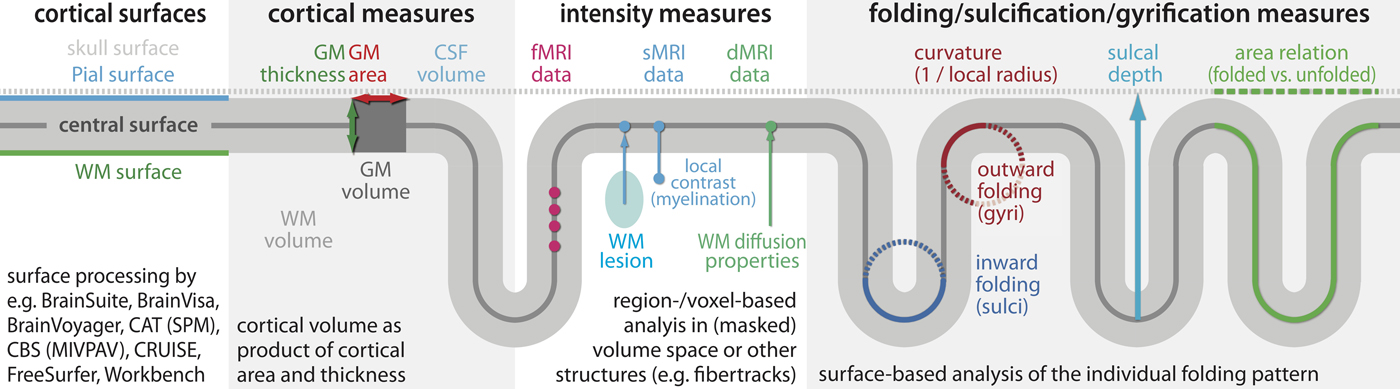

In general, sMRI analyses focus on morphometric brain features such as thickness (e.g., Dahnke, Yotter, & Gaser, Reference Dahnke, Yotter and Gaser2013; Fischl, Reference Fischl2012; Winkler et al., Reference Winkler, Kochunov, Blangero, Almasy, Zilles, Fox and Glahn2010), area (e.g., Fischl, Reference Fischl2012; Winkler et al., Reference Winkler, Kochunov, Blangero, Almasy, Zilles, Fox and Glahn2010), volume (e.g., Winkler et al., Reference Winkler, Kochunov, Blangero, Almasy, Zilles, Fox and Glahn2010), and gyrification (e.g., Li, Wang, et al., Reference Li, Wang, Shi, Lyall, Lin, Gilmore and Shen2014; Schaer et al., Reference Schaer, Cuadra, Tamarit, Lazeyras, Eliez and Thiran2008) of the brain's gray matter (GM), white matter (WM), and cerebrospinal fluid by means of voxel-based (e.g., Ashburner & Friston, Reference Ashburner and Friston2000), surface-based (e.g., Fischl, Reference Fischl2012), deformation-based (e.g., Gaser et al., Reference Gaser, Nenadic, Buchsbaum, Hazlett and Buchsbaum2001), or region-based morphometry analyses (e.g., Fischl, Reference Fischl2012; Klein & Tourville, Reference Klein and Tourville2012) as illustrated in Figure 1. A reasonable resolution (about 1 mm or better), good tissue contrast, and artifact-free images (e.g., motion; Reuter et al., Reference Reuter, Tisdall, Qureshi, Buckner, van der Kouwe and Fischl2015) are required for accurate tissue classification (e.g., Ashburner & Friston, Reference Ashburner and Friston2000), surface reconstruction (e.g., Dahnke et al., Reference Dahnke, Yotter and Gaser2013; Fischl, Reference Fischl2012; Li, Wang, et al., Reference Li, Wang, Shi, Lyall, Lin, Gilmore and Shen2014), and to normalize the individual anatomy to a common reference template or atlas (spatial registration; e.g., Ashburner & Friston, Reference Ashburner and Friston2011; Avants et al., Reference Avants, Tustison, Song, Cook, Klein and Gee2011; Klein & Tourville, Reference Klein and Tourville2012; Tardif et al., Reference Tardif, Schäfer, Waehnert, Dinse, Turner and Bazin2015). Besides tissue classification, quantitative imaging (e.g., Weiskopf et al., Reference Weiskopf, Suckling, Williams, Correia, Inkster, Tait and Lutti2013) or specific contrast changes in the WM (e.g., the water myelin fraction; Billiet et al., Reference Billiet, Vandenbulcke, Mädler, Peeters, Dhollander, Zhang and Emsell2015) or GM (e.g., Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Jbabdi, Glasser, Andersson, Burgess, Harms and Jenkinson2014) allows analysis of microstructural changes.

Figure 1. (Color online) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-based measures. There are MRI-based measures to characterize structural and function changes of specific brain regions. Structural analysis uses the image contrast to classify the major tissue (GM, gray matter; WM, white matter; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid), map the individual brain to a common template (spatial normalization), and analyze volume, thickness, area, folding, or intensity changes. Surface-based analysis allows (a) separating cortical GM into area and thickness especially in case of thickness reduction and simultaneous area enlargement (Winkler et al., Reference Winkler, Kochunov, Blangero, Almasy, Zilles, Fox and Glahn2010), (b) the estimation of the myelination degree (Billiet et al., Reference Billiet, Vandenbulcke, Mädler, Peeters, Dhollander, Zhang and Emsell2015; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Jbabdi, Glasser, Andersson, Burgess, Harms and Jenkinson2014), and (c) the cortical folding that is expected to describe the properties of its early development in utero (Budday et al., Reference Budday, Steinmann and Kuhl2015; Tallinen et al., Reference Tallinen, Chung, Rousseau, Girard, Lefèvre and Mahadevan2016). Surface-based processing further allows improved normalization and smoothing that is typically required for statistical analysis (Ashburner & Friston, Reference Ashburner and Friston2000). To measure WM changes diffusion MRI (dMRI) allows identifying of fiber properties. In addition, dMRI but also functional MRI (fMRI) can further be used to reconstruct structural dMRI and functional fMRI networks (connectroms) to understand the connectivity of different brain areas.

In general, dMRI aims to characterize WM fiber tracts by measuring diffusion patterns of water inside brain tissue. It allows to describe local fiber properties such as fractional anisotropy (FA; i.e., direction of diffusion), axial diffusivity (AD), neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI) (e.g., Billiet et al., Reference Billiet, Vandenbulcke, Mädler, Peeters, Dhollander, Zhang and Emsell2015; Jelescu et al., Reference Jelescu, Veraart, Adisetiyo, Milla, Novikov and Fieremans2015; Kunz et al., Reference Kunz, Zhang, Vasung, O'Brien, Assaf, Lazeyras and Hüppi2014; Winston et al., Reference Winston, Micallef, Symms, Alexander, Duncan and Zhang2014; Zhan et al., Reference Zhan, Dinov, Li, Zhang, Hobel, Shi and Liu2013), or fiber tracing (e.g., Billiet et al., Reference Billiet, Vandenbulcke, Mädler, Peeters, Dhollander, Zhang and Emsell2015; Mori et al., Reference Mori, Kaufmann, Davatzikos, Stieltjes, Amodei, Fredericksen and van Zijl2002; Roalf et al., Reference Roalf, Quarmley, Elliott, Satterthwaite, Vandekar, Ruparel and Gur2016; Yu et al., Reference Yu, Ouyang, Chalak, Jeon, Chia, Mishra and Huang2015).

In general, fMRI data are time series of volumes (4D data) that index changes in the oxygenation of the blood that allow analyzing brain activity patterns while the participant is performing specific tasks (e.g., visual perception; Kanwisher, McDermott, & Chun, Reference Kanwisher, McDermott and Chun1997) or during a resting state (rs; e.g., Smith et al., Reference Smith, Fox, Miller, Glahn, Fox, Mackay and Beckmann2009). Functional data can also be measured by other noninvasive methods such as electroencephalography (EEG; e.g., Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Mendoza, D'Anna, Zerbe, McCarthy, Hoffman and Ross2012; Mulkey et al., Reference Mulkey, Yap, Bai, Ramakrishnaiah, Glasier, Bornemeier and Bhutta2015; Otte, Donkers, Braeken, & Van den Bergh, Reference Otte, Donkers, Braeken and Van den Bergh2015; Stam & van Straaten, Reference Stam and van Straaten2012; Tóth et al., Reference Tóth, Urbán, Háden, Márk, Török, Stam and Winkler2017), magnetoencephalography (e.g., Stam et al., Reference Stam, Tewarie, van Dellen, van Straaten, Hillebrand and van Mieghem2014; Stam & van Straaten, Reference Stam and van Straaten2012). Frontal alpha EEG asymmetry has been used as a rs-EEG measure (e.g., Müller, Kühn-Popp, Meinhardt, Sodian, & Paulus, Reference Müller, Kühn-Popp, Meinhardt, Sodian and Paulus2015) while event-related potential studies (ERP), involving averaging the EEG activity time-locked to the presentation of a stimulus of some sort (visual, somatosensory, or auditory) are task-related EEG-measures (e.g., Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Mendoza, D'Anna, Zerbe, McCarthy, Hoffman and Ross2012; Otte et al., Reference Otte, Donkers, Braeken and Van den Bergh2015). EEGs record the electrical brain activity with superior temporal but lower spatial resolution compared to fMRI.

The functional units of the brain are networks of specialized, neural structures shown to communicate with each other (Poldrack, Reference Poldrack2012). Conventional task-based analytical approaches use univariate models that calculate average responses of the brain to manipulations, either for a region of interest or at the whole-brain level (voxel-wise); these models enable localizing cognitive functions based on the blood oxygen level dependent response (Ogawa et al., Reference Ogawa, Tank, Menon, Ellermann, Kim, Merkle and Ugurbil1992). However, a model that takes the connections between neural structures into account is likely to give a more valid description of neural responses than a model that assumes functional independence (Sporns, Chialvo, Kaiser, & Hilgetag, Reference Sporns, Chialvo, Kaiser and Hilgetag2004). Accordingly, moving beyond characterizing individual regions, the brain is increasingly viewed as a connected organ, a connectome (Hagmann, Reference Hagmann2005; Sporns, Tononi, & Kötter, Reference Sporns, Tononi and Kötter2005) where regions interact in larger networks in order to optimize behavior. This research field is often referred to as “connectomics” (Behrens & Sporns, Reference Behrens and Sporns2012), a popular term to capture research aimed at describing structural and/or functional connections between nodes (i.e., specified regions) within the connected brain (Rubinov & Sporns, Reference Rubinov and Sporns2010; Watts & Strogatz, Reference Watts and Strogatz1998). For a description of analytic connectivity methods, we refer to papers that describe important categories of analytic methods including seed-based correlations, independent component analysis, clustering, pattern classification, and local method such as regional homogeneity and low-frequency fluctuations (e.g., Cole, Smith, & Beckmann, Reference Cole, Smith and Beckmann2010; Margulies et al., Reference Margulies, Böttger, Long, Lv, Kelly, Schäfer and Villringer2010).

In neurodevelopmental studies (e.g., attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD]; Castellanos & Proal, Reference Castellanos and Proal2012) two functional connectivity (FC) approaches are often used. Seed-based correlations examine correlations of time series between a region of interest (a “seed”) and remaining GM voxels. Yet, constraining seed selection remains a challenge as even minor variations matter. Independent component analysis is a second, popular alternative; four-dimensional imaging data are decomposed into three-dimensional spatial maps, each with associated time courses (Castellanos & Aoki, Reference Castellanos and Aoki2016). These maps of coherent spontaneous blood oxygen level dependent signals correspond to functional networks that are revealed by task-based fMRI (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Fox, Miller, Glahn, Fox, Mackay and Beckmann2009), including the default mode network (DMN), which has been historically most often studied and includes the medial parietal (precuneus and posterior cingulate), bilateral inferior–lateral–parietal, and ventromedial frontal cortex (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Fox, Miller, Glahn, Fox, Mackay and Beckmann2009). Other large-scale networks include the executive control, sensorimotor, and left and right attention networks. In human prenatal stress research this method is only beginning to be used.

In the context of connectivity analyses, graph theory is often used as one mathematical framework to quantitatively describe the topological organization of connectivity. Several complex network measures of brain connectivity identifying centrality, functional integration, and segregation have been described in Rubinov and Sporns (Reference Rubinov and Sporns2010). Next to information about overall network infrastructure, specific features are also conveyed, such as which “nodes” (locations) within a system are central “hubs” of connectivity, linking numerous other units to one another. For example, graph analysis applied to fMRI data sets revealed that the human brain is organized with “small-world” topology (van den Heuvel, Mandl, & Hulshoff Pol, Reference van den Heuvel, Mandl and Hulshoff Pol2008); this is a network “in which constituent nodes exhibit a large degree of clustering as well as relatively short distances between any two nodes of the system and is thought to reflect a balance between local processing and global integration of information” (Menon, Reference Menon2013, p. 629). Another important finding is that the posterior cingulate and insular cortices are connectivity hubs (Fransson & Marrelec, Reference Fransson and Marrelec2008; Hagmann et al., Reference Hagmann, Cammoun, Gigandet, Meuli, Honey, Wedeen and Sporns2008; Margulies et al., Reference Margulies, Vincent, Kelly, Lohmann, Uddin, Biswal and Petrides2009; Menon, Reference Menon2013). These topological brain connectivity measures have been used to characterize human brain development, starting in utero; their use in human prenatal stress research is being explored (see e.g., van den Heuvel & Thomason, Reference van den Heuvel and Thomason2016)

Development of the Human Brain: Insights From Physical Modeling and Computational Simulation Studies and Advanced Neuroimaging Techniques

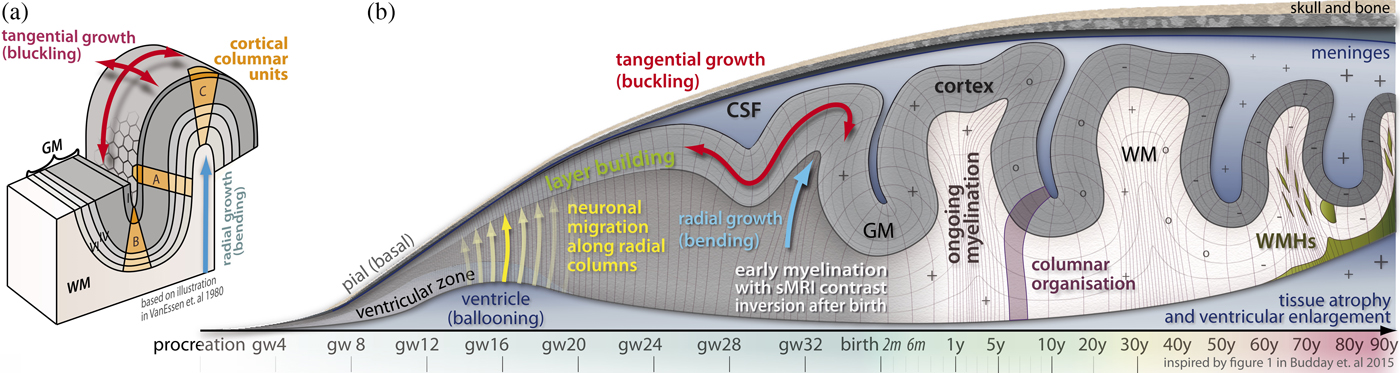

We highlight the importance of functional genomics for the brain developmental trajectory and then focus this section on new insights about brain development that are mainly gained by physical modeling and computational simulation studies and brain imaging studies. Brain development follows biomechanical rules and undergoes different major stages: ballooning and gyrification in utero (Bayly, Taber, & Kroenke, Reference Bayly, Taber and Kroenke2014; Budday, Steinmann, & Kuhl, Reference Budday, Steinmann and Kuhl2015; Lewitus, Kelava, & Huttner, Reference Lewitus, Kelava and Huttner2013; Striedter, Srinivasan, & Monuki, Reference Striedter, Srinivasan and Monuki2015; Tallinen & Biggins, Reference Tallinen and Biggins2015; Tallinen et al., Reference Tallinen, Chung, Rousseau, Girard, Lefèvre and Mahadevan2016) and a subsequent scaling in childhood and adolescence (Franke, Luders, May, Wilke, & Gaser, Reference Franke, Luders, May, Wilke and Gaser2012; Jiang & Nardelli, Reference Jiang and Nardelli2016), whereas further healthy changes are recognized as plasticity (short time; e.g., Gaser & Schlaug, Reference Gaser and Schlaug2003; Maguire et al., Reference Maguire, Gadian, Johnsrude, Good, Ashburner, Frackowiak and Frith2000; Reid, Sale, Cunnington, Mattingley, & Rose, Reference Reid, Sale, Cunnington, Mattingley and Rose2017) and aging (long time; e.g., Franke, Ziegler, Klöppel, & Gaser, Reference Franke, Ziegler, Klöppel and Gaser2010; Ziegler, Ridgway, Dahnke, Gaser, & Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, Reference Ziegler, Ridgway, Dahnke and Gaser2014). These processes are illustrated in Figure 2. For a detailed overview of in utero development, we would like to refer to Budday et al. (Reference Budday, Steinmann and Kuhl2015) and give here just a short overview.

Figure 2. (Color online) Brain development and aging. (a) Cortical folding. (b) Illustration of brain development and aging process over lifetime, with focus on the prenatal life period. One of the essential times in development is the apial creation of neurons and their migration to the pial regions where they build the cortical gray matter layer. This immense tangential and radial growth causes folding of larger gyri and sulci between gestation weeks 24 and 34 (Budday et al., Reference Budday, Steinmann and Kuhl2015). The myelination begins significantly after birth and ends after decades. The local folding (bending and buckling) compresses and stretches the cortical layers by keeping the volumes of each layer of the imaginary cortical columnar units A, B, and C (see part [a]) relatively similar (van Essen & Maunsell, Reference van Essen and Maunsell1980).

Functional genomics of human brain development

The building of the brain starts form a patch of cells; during embryonic and fetal life, complex developmental processes construct its initial architecture, which is dynamically changed during the whole life span (Collin & van den Heuvel, Reference Collin and van den Heuvel2013; Silbereis, Pochareddy, Zhu, Li, & Sestan, Reference Silbereis, Pochareddy, Zhu, Li and Sestan2016). Although it is generally known that from the first phase in development, that is, the zygote, the species-specific genome functions to guide development, recent large-scale analyses of the proteome/transcriptome and regulome have revealed that brain development entails very complex and sophisticated interactions between genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors (for reviews, see Jiang & Nardelli, Reference Jiang and Nardelli2016; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Kawasawa, Cheng, Zhu, Xu, Li and Sestan2011; Pletikos et al., Reference Pletikos, Sousa, Sedmak, Meyer, Zhu, Cheng and Šestan2014; Silbereis et al., Reference Silbereis, Pochareddy, Zhu, Li and Sestan2016; Ziats, Grosvenor, & Rennert, Reference Ziats, Grosvenor and Rennert2015). A most important insight is that gene expression dynamics underlying early human brain development are spatially and temporally specific and involve complex regulatory processes at several levels, for example, coordinate progressive cell fate specification and tissue morphogenesis (Bernadskaya & Christiaen, Reference Bernadskaya and Christiaen2016). The regulatory processes involve (a) transcription factors that operate in the context of complex gene regulatory networks, for example, transregulatory elements, which are genes that modify the expression of distant genes through intermolecular interaction and cis-regulatory modules, a stretch of DNA sequences where transcription factors bind and regulate expression of nearby genes; (b) epigenetic gene regulatory mechanisms (such as DNA methylation and histone modification, long noncoding RNAs, and short noncoding RNAs, including microRNAs; Geschwind & Flint, Reference Geschwind and Flint2015). This means that major aspects of development such as proliferation, migration, and differentiation are not fully programmed genetically. According to Ben-Ari and Spitzer (Reference Ben-Ari and Spitzer2010, p .486), they rely on “phenotypic checkpoints, i.e., times and places during development at which functional validation appropriate to the stage of the cells enables the process to go forward normally, take an alternative route, or become arrested.” According to Huang, Hu, Kauffman, Zhang, and Shmulevich (Reference Huang, Hu, Kauffman, Zhang and Shmulevich2009, p. 1), theoretical considerations as well as experimental evidence support the view “that cell fates (or commitment) are ‘high dimensional attractor states’ of the underlying molecular network.” There is emerging evidence from preclinical and from human postmortem, modeling and neuroimaging studies that, next to genetic risks (i.e., polygenetic risks; common, rare, and de novo mutations), diverse extrinsic factors occurring in the prenatal and early postnatal life period presumed to enable changes in these complex regulatory processes, alter the spatiotemporal expression of gene patterns. The latter leads to alterations in patterning and regionalization of the GM, as well as in intracortical myelin and WM; all of these changes influence the developing structural and functional brain connectome in spatiotemporal specific ways (e.g., Bernadskaya & Christiaen, Reference Bernadskaya and Christiaen2016). Negative environmental factors include maternal nutritional, medical and distress factors, and hypoxia/ischemia. Emerging evidence shows that such prenatally and early postnatally acquired “neuroanatomy” changes (Donovan & Basson, Reference Donovan and Basson2017) partially underlie behavioral and cognitive changes, including those observed in common neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders (Deoni et al., Reference Deoni, Zinkstok, Daly, Ecker, Williams and Murphy2014; Ghiani & Faundez, Reference Ghiani and Faundez2017; Haroutunian et al., Reference Haroutunian, Katsel, Roussos, Davis, Altshuler and Bartzokis2014; Ziats et al., Reference Ziats, Grosvenor and Rennert2015). Positive environmental factors, such as getting breastfed for a period of at least 3 months, is shown to have a developmental advantage (i.e., a positive effect on WM microstructure in late maturing frontal and association brain regions; Deoni et al., Reference Deoni, Dean, Piryatinsky, O'Muircheartaigh, Waskiewicz, Lehman and Dirks2013). We refer to review papers (e.g., Bernadskaya & Christiaen, Reference Bernadskaya and Christiaen2016; Geschwind & Flint, Reference Geschwind and Flint2015; Parikshak, Gandal, & Geschwind, Reference Parikshak, Gandal and Geschwind2015) that specify how system biology and network approaches (e.g., by using graph theory) are applied to human genetics.

Prenatal brain development phases: Ballooning and gyrification

The ballooning phase, from gestation week (gw) 3 to 15, is described by an intensive radial enlargement of the ventricle that compensates the simultaneous tangential growth of the intermediate zone and increases the brain surface without significant folding, where only the longitudinal and Sylvian fissures become prominent by radial grow (bending, i.e., forces below the developing cortex; see Figure 2). In gw 5 to 20, neurons are generated in the ventricular zone and migrate to the skull, where they create the cortical layer structure. At this time, the cortex shows a radial dMRI pattern, indicating low connectivity within the cortex (Budday et al., Reference Budday, Steinmann and Kuhl2015; Jiang & Nardelli, Reference Jiang and Nardelli2016; Striedter et al., Reference Striedter, Srinivasan and Monuki2015), whereas the first large fiber tracts are becoming visible in the WM (e.g., in the corpus callosum; Wegiel et al., Reference Wegiel, Kuchna, Nowicki, Imaki, Wegiel, Marchi and Wisniewski2010).

After ballooning, the neurons start forming layer depending connections when neuronal migration is finished and the radial dMRI pattern gets lost (Budday et al., Reference Budday, Steinmann and Kuhl2015, p. 6; Wegiel et al., Reference Wegiel, Kuchna, Nowicki, Imaki, Wegiel, Marchi and Wisniewski2010). This stage also involves the growth of neuronal dendrites and axons; the production and expansion of astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglial cell; as well as the formation of synapses and the development of the vasculature system (Budday et al., Reference Budday, Steinmann and Kuhl2015, p. 14). By these phenomena, the tangential growth of the outer cortex becomes prominent and causes tangential grow (buckling, i.e., forces within the developing cortex) and forms major structures such as the central sulcus around gw 24 (Budday et al., Reference Budday, Steinmann and Kuhl2015; Tallinen et al., Reference Tallinen, Chung, Rousseau, Girard, Lefèvre and Mahadevan2016). External forces due to limitations of the skull and meninges were found to have minor effects, and it is presumed that gyrification depends on tangential growth of the GM; this is referred to as the buckling theory (e.g., Bayly et al., Reference Bayly, Taber and Kroenke2014; Budday et al., Reference Budday, Steinmann and Kuhl2015; Striedter et al., Reference Striedter, Srinivasan and Monuki2015; Tallinen et al., Reference Tallinen, Chung, Rousseau, Girard, Lefèvre and Mahadevan2016). Recent experimental and computational growth models (Bayly et al., Reference Bayly, Taber and Kroenke2014; Budday et al., Reference Budday, Steinmann and Kuhl2015; Tallinen et al., Reference Tallinen, Chung, Rousseau, Girard, Lefèvre and Mahadevan2016; Toro, Reference Toro2012) have shown promising results to explain the natural folding as an energy-minimizing process of radial and tangential surface expansion that relies on the stiffness of the inner core (the WM), the cortical growing rate, and local cortical thickness. The bending of cortex is locally compensated by thickness changes of the cortical layer that finally guarantee an equal number of neurons independent of the local amount of folding (van Essen & Maunsell, Reference van Essen and Maunsell1980). Tallinen and Biggins (Reference Tallinen and Biggins2015) demonstrate that soft and thinner structures and high growing rates lead to increases in “Z” folds (that are more typical for early development), whereas stiffer cores led to more complex “Y” folds (that are more typical for later development). Modification of these morphological properties may occur with alterations either in the gene network (e.g., by de novo mutations, in transcription factors) or in the epigenetic gene regulatory networks (e.g., DNA methylation, long noncoding RNAs, which may be caused by environmental factors); these changes may result in varying folding pattern that can be measured even in the adult brain (Bayly et al., Reference Bayly, Taber and Kroenke2014; Budday et al., Reference Budday, Steinmann and Kuhl2015; Tallinen & Biggins, Reference Tallinen and Biggins2015; Tallinen et al., Reference Tallinen, Chung, Rousseau, Girard, Lefèvre and Mahadevan2016). The gyrification occurs in synchrony with neuronal connectivity; that is, it starts after all neurons have reached their final position in the developing cortex between gw 17 and gw 47 (i.e., seventh week after birth in term-born babies; Budday et al., Reference Budday, Steinmann and Kuhl2015). However, it is also the case that early neuronal migration “sets the stage” for the folding process as disturbed migration processes lead to disrupted neuronal connectivity and, hence, delayed growth and altered cortical formation of malformation (Budday et al., Reference Budday, Steinmann and Kuhl2015, p. 14). The folding is nearly completed around birth in humans, and both tangential and radial growth is balanced again (Evans & Group, Reference Evans2006; Li, Wang, et al., Reference Li, Wang, Shi, Lyall, Lin, Gilmore and Shen2014; Tallinen & Biggins, Reference Tallinen and Biggins2015).

The developing connectome: In utero and during infancy

With the use of rs-MRI, it has become recently possible to map FC of the human fetus in utero. Earlier studies in full-term (Fransson et al., Reference Fransson, Skiold, Horsch, Nordell, Blennow, Lagercrantz and Aden2007) and preterm infants (Doria et al., Reference Doria, Beckmann, Arichi, Merchant, Groppo, Turkheimer and Edwards2010; Smyser et al., Reference Smyser, Inder, Shimony, Hill, Degnan, Snyder and Neil2010) had suggested the existence of a “proto” or partial baseline DMN similar to the DMN observed in children and adults. Fetal rs-fMRI has confirmed the presence of primitive forms of functional networks by middle gestation, including the DMN. The connectivity of the posterior cingulate cortex may be seen as a precursor of the adult DMN (van den Heuvel & Thomason, Reference van den Heuvel and Thomason2016). Thomason et al. (Reference Thomason, Brown, Dassanayake, Shastri, Marusak, Hernandez-Andrade and Romero2014) applied a graph theoretical approach to resting state FC of healthy fetuses, 19 to 39 gw. It was found that the fetal brain has a modular organization and that the modules overlap with functional systems observed postnatally. Compared to younger fetuses (<31 gw), in older fetuses (>31 gw) modularity decreases, and connectivity of the posterior cingulate to other brain networks becomes more negative. Modularity refers to the degree to which a network can be divided into nonoverlapping subsets of regions (i.e., “modules”) that are internally interactive, while sparsely connected with outside areas (Thomason et al., Reference Thomason, Brown, Dassanayake, Shastri, Marusak, Hernandez-Andrade and Romero2014, p. 2). The higher modularity in the younger fetuses is indicative of more segregated functional subnetworks. Fetal FC may develop according to a medial to lateral (Schöpf, Kasprian, Brugger, & Prayer, Reference Schöpf, Kasprian, Brugger and Prayer2012; Thomason et al., Reference Thomason, Dassanayake, Shen, Katkuri, Alexis, Anderson and Romero2013) and a posterior to anterior pattern (Jakab et al., Reference Jakab, Schwartz, Kasprian, Gruber, Prayer, Schöpf and Langs2014).

We refer to recent review papers for a detailed overview of the development of the brain connectome. Of the review papers that focus specifically on early life (i.e., prenatal and/or infancy and/or early childhood), some papers either focus on FC (e.g., Kipping, Tuan, Foiiter, & Qiu, Reference Kipping, Tuan, Foiiter and Qiu2016; Menon, Reference Menon2013; Power, Fair, Schlaggar, & Petersen, Reference Power, Fair, Schlaggar and Petersen2010; van den Heuvel & Thomason, Reference van den Heuvel and Thomason2016) or on structural connectivity (SC; e.g., Batalle et al., Reference Batalle, Hughes, Zhang, Tournier, Tusor, Aljabar and Counsell2017). Other authors describe both structural and functional networks combined with the description of at least one of the following topics: (a) the development of the structure–function coupling (Hagmann, Grant, & Fair, Reference Hagmann, Grant and Fair2012); (b) underlying neurobiological processes (Collin & van den Heuvel, Reference Collin and van den Heuvel2013; Dubois et al., Reference Dubois, Dehaene-Lambertz, Kulikova, Poupon, Hüppi and Hertz-Pannier2014; Vértes & Bullmore, Reference Vértes and Bullmore2015); (c) atypical connectome development in at-risk populations (Ball et al., Reference Ball, Aljabar, Zebari, Tusor, Arichi, Merchant and Counsell2014; Dennis & Thompson, Reference Dennis and Thompson2013; Di Martino et al., Reference Di Martino, Fair, Kelly, Satterthwaite, Castellanos, Thomason and Milham2014; Gupta, Gupta, & Shirasaka, Reference Gupta, Gupta and Shirasaka2016; Han, Chapman, & Krawczyk, Reference Han, Chapman and Krawczyk2016; Koyama et al., Reference Koyama, Di Martino, Castellanos, Ho, Marcelle, Leventhal and Milham2016); or (d) the environmental and genetic factors that influence the connectome (Atasoy, Donnelly, & Pearson, Reference Atasoy, Donnelly and Pearson2016; Richmond, Johnson, Seal, Allen, & Whittle, Reference Richmond, Johnson, Seal, Allen and Whittle2016). Studies that focus on the whole life span mostly compare brain development in infancy, childhood, adulthood and/or old age (e.g., Billiet et al., Reference Billiet, Vandenbulcke, Mädler, Peeters, Dhollander, Zhang and Emsell2015; Lebel et al., Reference Lebel, Gee, Camicioli, Wieler, Martin and Beaulieu2012).

Brain development across the life span: Short overview

Over an individual's lifetime, cortical thickness peaks between ages 3 and 9 (Walhovd, Fjell, Giedd, Dale, & Brown, Reference Walhovd, Fjell, Giedd, Dale and Brown2016) and then shrinks slowly every year, whereas the WM continues to develop until the fourth to fifth decade (Billiet et al., Reference Billiet, Vandenbulcke, Mädler, Peeters, Dhollander, Zhang and Emsell2015; Chang et al., Reference Chang, Owen, Pojman, Thieu, Bukshpun, Wakahiro and Mukherjee2015; Walhovd et al., Reference Walhovd, Fjell, Giedd, Dale and Brown2016). The maturing and regressive biophysical changes in both GM and WM occur heterochronically in different brain regions (Haroutunian et al., Reference Haroutunian, Katsel, Roussos, Davis, Altshuler and Bartzokis2014). Besides the global trend of tissue atrophy with aging, brain plasticity allows an increase in local tissue volume by learning (Gaser & Schlaug, Reference Gaser and Schlaug2003; Maguire et al., Reference Maguire, Gadian, Johnsrude, Good, Ashburner, Frackowiak and Frith2000; Reid et al., Reference Reid, Sale, Cunnington, Mattingley and Rose2017).

The WM can further degenerate as evidenced by MRI as WM hyperintensities with GM-like intensities in aging (Evans & Brain Development Cooperative Group, Reference Evans2006; Habes et al., Reference Habes, Erus, Toledo, Zhang, Bryan, Launer and Davatzikos2016), as well as in diseases such as multiple sclerosis (Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Gaser, Arsic, Buck, Förschler, Berthele and Mühlau2012) and Alzheimer disease (Ziegler et al., Reference Ziegler, Ridgway, Dahnke and Gaser2014). In neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer disease, accelerated tissue atrophy was reported (Franke et al., Reference Franke, Ziegler, Klöppel and Gaser2010; Ziegler et al., Reference Ziegler, Ridgway, Dahnke and Gaser2014).

Prenatal Stress Alters the Developmental Trajectory of the Brain: Brain Imaging Studies From Birth Until Adulthood

There is an increasing number of prospective studies examining associations between prenatal exposure to maternal distress during pregnancy and offspring outcome measures such as motor development, cognition, neurocognitive functioning, learning problems, temperament, and mental health (Bock, Wainstock, Braun, & Segal, Reference Bock, Wainstock, Braun and Segal2015; Bowers & Yehuda, Reference Bowers and Yehuda2016; Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Galbally, Gannon and Symeonides2014; Van den Bergh et al., Reference Van den Bergh, van den Heuvel, Lahti, Braeken, de Rooij, Entringer and Schwab2017). However, only a small number of the studies reviewed included brain measures. Studies explicitly examining offspring brain functional, structural, and brain connectome measures are promising in contributing crucial knowledge, (e.g., about alteration in specific brain regions or networks that may underlie the observed effects in the offspring). Moreover, especially the prospective longitudinal follow-up studies extending over a considerable postnatal time period may reveal changes in brain developmental trajectories. When available, information on mediating factors (such as genetic and epigenetic factors) and moderating factors (such as gender, postnatal maternal distress) will also be described.

Results in newborns, infants, and preschoolers (Ages: 0–5 year)

Structural brain changes: sMRI and dMRI studies

In the prospective longitudinal Growing up in Singapore Towards Healthy Outcomes (GUSTO), pregnant mothers were recruited at 13 weeks of pregnancy. Maternal depression and anxiety were measured at 26–28 weeks of pregnancy and when the child was 3 months and 1, 2, 3, and 4.5 years old. Effect of prenatal exposure to maternal distress was examined in infants (N = between 24 and 203) at 4–17 days after birth, at 6 months of age, and at 4.5 years with sMRI and/or dMRI of specific brain regions (Qiu, Anh, et al., Reference Qiu, Anh, Li, Chen, Rifkin-Graboi, Broekman and Meaney2015; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Rifkin-Graboi, Chen, Chong, Kwek, Gluckman and Meaney2013; Rifkin-Graboi et al., Reference Rifkin-Graboi, Bai, Chen, Hameed, Sim, Tint and Qiu2013; Wen et al., Reference Wen, Poh, Ni, Chong, Chen, Kwek and Qiu2017) or the whole brain (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Pan, Tuan, Teh, MacIsaac, Mah and Holbrook2015; Qiu, Tuan, et al., Reference Qiu, Tuan, Ong, Li, Chen, Rifkin-Graboi and Gluckman2015; Rifkin-Graboi et al., Reference Rifkin-Graboi, Meaney, Chen, Bai, Hameed, Tint and Qiu2015).

Rifkin-Graboi et al. (Reference Rifkin-Graboi, Bai, Chen, Hameed, Sim, Tint and Qiu2013) observed a significant association between maternal depression in pregnancy and microstructure of the amygdala, a region associated with stress reactivity and fear regulation (i.e., compared to neonates of mothers with low-normal depression scores in pregnancy, FA in the left and right amygdala, and AD in right amygdala were lower in neonates of mothers with high depressive symptoms in pregnancy). However, no associations were found between maternal depression and volume of either the left or right amygdala. In contrast, the whole-brain analysis dMRI study of Rifkin-Graboi et al. (Reference Rifkin-Graboi, Meaney, Chen, Bai, Hameed, Tint and Qiu2015) revealed no effects of maternal anxiety during pregnancy on amygdala microstructure. However, maternal anxiety did predict alterations, that is, lower FA in WM fiber tracts in several regions: (a) dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and right insular cortex (regions important to cognitive–emotional responses to stress); (b) right middle occipital (important for sensory processing); (c) right angular gyrus, uncinate fasciculus, posterior cingulate, and parahippocampus (important for social cognition, social–emotional functioning); and (d) right cerebellum (important for sensorimotor learning and higher cognitive function). Moreover, high maternal anxiety was associated with lower AD in the left lateral orbitofrontal cortex and left inferior cerebellar peduncle and with higher AD in the genu of the corpus callosum. As the latter study did not reveal significant effects of depression on FA or AD values after corrections for multiple testing, the authors concluded that the effects found may be anxiety specific (Rifkin-Graboi et al., Reference Rifkin-Graboi, Meaney, Chen, Bai, Hameed, Tint and Qiu2015). Tentative support was found for associations of five lateralized clusters (right insular, inferior frontal, middle occipital, middle temporal, and parahippocampal) with offspring internalizing problems (but not externalizing behavior) at 1 year of age (Rifkin-Graboi et al., Reference Rifkin-Graboi, Meaney, Chen, Bai, Hameed, Tint and Qiu2015).

Qiu, Tuan, et al. (Reference Qiu, Tuan, Ong, Li, Chen, Rifkin-Graboi and Gluckman2015) observed an effect of maternal anxiety during pregnancy on neonatal cortical morphology that was moderated in several ways by functional variants of the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene, which regulates catecholamine signaling in the prefrontal cortex and is implicated in anxiety, pain, and stress responsivity. The A-val-G (AGG) haplotype moderated the positive link between maternal anxiety and thickness of the right ventrolateral prefrontal, right parietal cortex, and precuneus. The G-met-A (GAA) haplotype modulated the negative link between maternal anxiety and thickness of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and bilateral precentral gyrus.

In the study by Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Pan, Tuan, Teh, MacIsaac, Mah and Holbrook2015), for each mother and each infant in the GUSTO cohort they identified the particpant's polymorphism of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) Val66 gene, that is, Met/Met, Met/Val, or Val/Val. BDNF is a neurotrophin known to underlie synaptic plasticity in the central nervous system (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Pan, Tuan, Teh, MacIsaac, Mah and Holbrook2015). They also conducted a genome-wide DNA analysis on umbilical cord samples, using Human Methylation450 Bead Chip Array, which allows quantification of methylation status with single-base resolution across 482,421 cytosine–phosphate–guanine sites (CpGs) and 3,091 non-CpGs (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Pan, Tuan, Teh, MacIsaac, Mah and Holbrook2015 p. 140). A first result showed that 148,890 CpGs had an absolute methylation difference of 15% between the three genotypic groups of the BDNF Val66Met gene. Second, the strength of the associations between maternal anxiety and neonatal DNA methylation was found to be different for different polymorphisms of the infant (not maternal) Val66Met gene; that is, in the Met/Met polymorphism group, there was a greater impact of antenatal maternal anxiety on the DNA methylation than in both other groups. Third, it was found that 9 of the 18 brain-volume measures used had significantly different numbers of variable CpGs (i.e., right amygdala, left hippocampus, left thalamus, left caudate, right midbrain, right cerebellum, left total WM, left GM, and right GM). For instance, there were significantly more CpGs where methylation levels covaried with right amygdala volume among Met/Met compared with both Met/Val and Val/Val carriers; in contrast, more CpGs covaried with left hippocampus volume in Val/Val infants compared with infants of the Met/Val or Met/Met genotype.

While Qiu et al. (Reference Qiu, Rifkin-Graboi, Chen, Chong, Kwek, Gluckman and Meaney2013) found no effect of prenatal exposure to maternal anxiety on hippocampal volume at birth or at 6 months of age, maternal anxiety was negatively correlated with hippocampal growth between 0 and 6 months. Furthermore, a positive association was observed between postnatal maternal anxiety and offspring right hippocampal growth and a negative one between postnatal maternal anxiety and left hippocampal growth at 6 months of age (Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Rifkin-Graboi, Chen, Chong, Kwek, Gluckman and Meaney2013).

Finally, Wen et al. (Reference Wen, Poh, Ni, Chong, Chen, Kwek and Qiu2017) showed sex-specific effects of exposure to maternal depression in the 4.5-year-olds of the GUSTO cohort. A positive association was found between maternal depressive symptoms during pregnancy and larger right amygdala volume in girls, but not in boys. Furthermore, a positive association was found between postnatal maternal depressive symptoms and higher right amygdala FA in the whole sample and in girls, but not in boys.

In a second cohort, recruited at Columbia University Medical Center in the city of New York, maternal depression as measured between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy with a self-reported questionnaire was used to define a depression group versus a not depressed group. Infants of both groups were examined at age of 5.8 weeks (Posner et al., Reference Posner, Cha, Roy, Peterson, Bansal, Gustafsson and Monk2016). Results of dMRI tractography demonstrated decreased structural connectivity between the right amygdala and the right ventral prefrontal cortex in the infants prenatally exposed to maternal depression (n = 18) compared to nonexposed infants (n = 39; Posner et al., Reference Posner, Cha, Roy, Peterson, Bansal, Gustafsson and Monk2016).

A third cohort was followed up until 2.6 to 5.1 years of age, as part of the Alberta Pregnancy Outcome and Nutrition Study (Lebel et al., Reference Lebel, Walton, Letourneau, Giesbrecht, Kaplan and Dewey2016). It was found that women's depression at 17 weeks of pregnancy was associated with preschoolers’ cortical thinning in the right inferior frontal and middle temporal region, and with radial diffusivity and mean diffusivity in WM emanating from the inferior frontal area. However, the latter association was no longer significant after correction for postpartum depression. Postpartum depression was related with cortical thinning in preschoolers’ right superior frontal cortical thickness and with diffusivity in WM originating from that region; the effect remained significant after correction for prenatal maternal depression. Maternal depression at 11 or 32 weeks of pregnancy was not significantly related with altered GM or WM structure (Lebel et al., Reference Lebel, Walton, Letourneau, Giesbrecht, Kaplan and Dewey2016).

In a fourth cohort, the Generation R study, brain imaging data of N = 654 6- to 10-year-old children prenatally exposed to maternal depressive symptoms (El Marroun et al., Reference El Marroun, Tiemeier, Muetzel, Thijssen, van der Knaap, Jaddoe and White2016) were analyzed. Maternal and paternal depressive symptoms was measured at 20.6 weeks of gestation and when the children were 3 years old. It was found that prenatal exposure to maternal depressive symptoms was associated (a) with a thinner cortex in the frontal area of the left hemisphere, (b) with larger cortical surface in a caudal middle frontal area in proximity to the area showing decreased cortical thickness, and (c) with gyrification measures (however, after correction for several covariates, this association did not remain significant). No association was found between prenatal exposure to maternal depressive symptoms and volumetric measures in core structures of the limbic system. Furthermore, no association was found with brain morphology measures and either prenatal paternal depressive symptoms or maternal depressive symptoms at age 3 years.

Functional brain development: fMRI and EEG studies

Scheinost, Kwon, et al. (Reference Scheinost, Kwon, Lacadie, Sze, Sinha, Constable and Ment2016) used rs-fMRI and whole-brain seed connectivity to compare FC in extremely premature born infants (born <28 gw) who, furthermore, were exposed to maternal anxiety or stress during pregnancy, with FC in a control group of very premature neonates (born <gw 32) and a term control group. Prenatal stress exposure was coded as a binary variable, that is, whether or not a diagnosis of depression and/or anxiety was retrieved in the maternal medical card. Compared to term controls, preterm born infants without exposure to maternal distress show decreased FC from the left amygdala to other subcortical regions (thalamus, hypothalamus, brainstem, and insula). Compared to the latter group, preterm infants prenatally exposed to maternal distress showed lower FC of the left amygdala to the thalamus, hypothalamus, and peristrate cortex. In the study by Posner et al. (Reference Posner, Cha, Roy, Peterson, Bansal, Gustafsson and Monk2016), rs-fMRI measures demonstrated that at the mean age of 5.8 weeks, infants prenatally exposed to maternal depression demonstrated increased inverse FC between the amygdala and the dorsal prefrontal cortex, bilaterally. Further analyses showed that changes in amygdala–prefrontal cortex connectivity were associated with an increase in fetal heart rate reactivity to a mild maternal stressor that had been measured at 34–37 weeks of gestation (Posner et al., Reference Posner, Cha, Roy, Peterson, Bansal, Gustafsson and Monk2016). Qiu, Anh, et al. (Reference Qiu, Anh, Li, Chen, Rifkin-Graboi, Broekman and Meaney2015) showed that 6-month-old infants of the GUSTO cohort, born to mothers with higher depressive symptoms during pregnancy, had greater FC of the amygdala with several other brain regions: the left temporal cortex, insula, bilateral anterior cingulate, medial orbitofrontal and ventromedial prefrontal cortices. These networks are known to underlie depression in children and adults, and the authors suggest that their rs-fRMI data may foreshadow future neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorder (Qiu, Anh, et al., Reference Qiu, Anh, Li, Chen, Rifkin-Graboi, Broekman and Meaney2015).

Other studies examined asymmetry of left and right frontal alpha EEG and stability of EEG patterns in infants. There is a large literature on the effects of early adversity, including effects of prenatal and/or postnatal depression on offspring frontal EEG asymmetry, but results are inconsistent (see, for reviews, e.g., Field & Diego, Reference Field and Diego2008; Field, Hernandez-Reif, & Diego, Reference Field, Hernandez-Reif and Diego2006; Peltola et al., Reference Peltola, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Alink, Huffmeijer, Biro and van IJzendoorn2014). For instance, while greater relative right frontal EEG activation has been associated with maternal depression in pregnancy in some studies (e.g., Lusby, Goodman, Bell, & Newport, Reference Lusby, Goodman, Bell and Newport2014), other studies concluded that the number of postpartum months of depression was a stronger predictor of infant frontal EEG asymmetry at 14 months of age than prepartum months of maternal depression (e.g., Dawson, Frey, Panagiotides, Osterling, & Hessl, Reference Dawson, Frey, Panagiotides, Osterling and Hessl1997). Field et al. (Reference Field, Diego, Hernandez-Reif, Figueiredo, Deeds, Ascencio and Kuhn2010), studied the effect of comorbid depression and anxiety during pregnancy (measured at 20 gw), and it was found that neonates of the comorbid and depressed groups had greater relative right frontal EEG measures than neonates of the anxiety and nondepressed groups. In the study of Lusby et al. (Reference Lusby, Goodman, Bell and Newport2014), participants all met DSM-IV criteria for depression or another mood disorder and were enrolled before 16 gw. Offspring EEG was recorded during baseline, feeding, and play at age 3 and 6 months. They observed an interaction effect of maternal prenatal and postnatal depressive symptoms on asymmetry in EEG patterns in 3- and 6-month-old infants, showing that prenatal depressive symptoms and infant EEG asymmetry scores were significantly associated among women with high postpartum depressive symptoms but not in those with low postnatal depressive symptoms. They concluded that asymmetry scores were mostly consistent across contexts (but not from baseline to feeding and play at 6 months) and stable across ages (but not during feeding). In another study of the same cohort, the moderating effect of prenatal maternal anxiety on associations between infants' frontal EEG asymmetry and temperamental negative affectivity across infants' first year of life was studied. The findings showed that behavioral and psychophysiological outcomes co-occur over the course of infancy and are different for infants of high versus low levels of maternal anxiety. For instance, infant negative affectivity and frontal EEG asymmetry were negatively associated at 3 months of age and positively associated by 12 months of age in the high depression mothers, while there was no association between infant negative affectivity and EEG at any age in the low depressive groups (Lusby, Goodman, Yeung, Bell, & Stowe, Reference Lusby, Goodman, Yeung, Bell and Stowe2016). In a GUSTO cohort study, Soe et al. (Reference Soe, Wen, Poh, Li, Broekman, Chen and Qiu2016) studied the effects of prenatal and postnatal depression, using EEG measures. They concluded that neither prenatal nor postnatal maternal depressive symptoms independently predicted neither frontal EEG activity nor FC in 6- and 18-month-old infants. However, higher levels of depressive symptoms postnatally, compared to the prenatal levels, were associated with greater right frontal activity and relative right frontal asymmetry at 6 months and with lower right frontal FC in 18-month-olds. Lower bilateral frontal FC at 18 months predicted higher externalizing problems, while lower right frontal FC predicted higher internalizing problems.

Some studies focused on the effects of maternal anxiety during pregnancy on infant auditory attention and measured offspring ERPs in reaction to auditory stimuli (Harvison, Molfese, Woodruff-Borden, & Weigel, Reference Harvison, Molfese, Woodruff-Borden and Weigel2009; Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Mendoza, D'Anna, Zerbe, McCarthy, Hoffman and Ross2012; Otte et al., Reference Otte, Donkers, Braeken and Van den Bergh2015; van den Heuvel, Donkers, Winkler, Otte, & Van den Bergh, Reference van den Heuvel, Donkers, Winkler, Otte and Van den Bergh2015). Auditory attention is a key aspect of early neurocognitive functioning and is vital for later acquisition of speech and language competences (Benasich et al., Reference Benasich, Choudhury, Friedman, Realpe-Bonilla, Chojnowska and Gou2006; Kushnerenko, Van den Bergh, & Winkler, Reference Kushnerenko, Van den Bergh and Winkler2013; Molfese, Reference Molfese2000). In the study of Harvison et al. (Reference Harvison, Molfese, Woodruff-Borden and Weigel2009) subject recruitment occurred in the maternity ward, and they completed a self-report anxiety questionnaire. Voice recordings of the neonate's mother and of a stranger were used as auditory stimuli. Results indicated alterations in auditory attention, with more attention allocated to a stranger's voice compared to the mother's voice in infants born to mothers with high anxiety and the opposite pattern in infants of mothers who were low anxious during pregnancy. Hunter et al. (Reference Hunter, Mendoza, D'Anna, Zerbe, McCarthy, Hoffman and Ross2012) reported diminished P50 response to auditory clicking in 3-month-old infants born to mothers diagnosed with anxiety disorder in pregnancy; this diminished response may reflect lower response inhibition during sensory gating.

In a cohort born in the Netherlands between 2010 and 2013 (van den Heuvel et al., Reference van den Heuvel, Donkers, Winkler, Otte and Van den Bergh2015), pregnant women completed self-report questionnaires in each pregnancy trimester (i.e., <15 gw, at 16–22 gw, and at 31–37 gw). It was shown that 9-month-old infants exposed to mothers with high versus low levels of maternal anxiety at 15–22 gw allocated more attentional resources (i.e., higher N250) to a frequently occurring standard sounds in an oddball paradigm; this may indicate a lack of habituation to these sounds or a state of enhanced vigilance in infants born to highly anxious mothers. The opposite pattern (i.e., lower N250) was found for prenatal exposure to maternal mindfulness. Otte et al. (Reference Otte, Donkers, Braeken and Van den Bergh2015) studied the same 9-month-old infants; infants were presented with emotional facial expressions (happy/fearful) followed by either a congruent or an incongruent vocalization (happy/fearful). Results indicated that infants prenatally exposed to higher levels of maternal anxiety (i.e., < gw 15) displayed larger P350 amplitudes in response to fearful vocalizations, regardless of the type of visual prime. This response may indicate increased attention (or enhanced vigilance) to fearful vocalizations. When the children of this cohort were 4 years old, they were again examined; ERPs were recorded when they passively watched neutral, pleasant, and unpleasant pictures (van den Heuvel, Henrichs, Donkers, & Van den Bergh, in press). It was found that compared to children exposed to lower levels of maternal anxiety during pregnancy, children exposed to higher level of maternal anxiety devoted more attentional resources to neutral pictures. Responding to neutral stimuli as if they are threatening may indicate a negativity bias and/or may indicate that these children show enhanced vigilance. A state of enhanced vigilance in a safe environment may be a predictive marker for later onset of an anxiety disorder (Thayer, Åhs, Fredrikson, Sollers, & Wager, Reference Thayer, Åhs, Fredrikson, Sollers and Wager2012).

Results in school-age children (Ages: 6–10 years)

In this age group only studies measuring an effect on structural brain changes were performed. Pregnant women completed self-report questionnaires at 19, 25, and 31 gw. The offspring, born between 1998 and 2002 in Southern California, were followed up until 6 to 9 years after birth. Significant associations between maternal anxiety, cortisol or depression during pregnancy and offspring structural brain changes were reported in three publications. Buss, Davis, Muftuler, Head, and Sandman (Reference Buss, Davis, Muftuler, Head and Sandman2010) reported an association between pregnancy-specific anxiety at 19 gw and decreased GM volume in areas extending from the cortical to the occipital regions (i.e., prefrontal cortex, premotor cortex, medial temporal lobe, lateral temporal cortex, postcentral gyrus, cerebellum extending, middle occipital gyrus, and fusiform gyrus). Maternal cortisol at 15 gw was associated with increased right amygdala volume in girls only; amygdala volume even mediated the association between maternal cortisol and girls’ emotional problems (Buss et al., Reference Buss, Davis, Shahbaba, Pruessner, Head and Sandman2012). However, maternal cortisol in pregnancy was not associated with child hippocampus volume (Buss et al., Reference Buss, Davis, Shahbaba, Pruessner, Head and Sandman2012). Anxiety measured at 25 or 31 gw or cortisol measured at 19, 21, 31, and 37 gw were not associated with structural brain changes (Buss et al., Reference Buss, Davis, Muftuler, Head and Sandman2010, Reference Buss, Davis, Shahbaba, Pruessner, Head and Sandman2012). Sandman, Buss, Head, and Davis (Reference Sandman, Buss, Head and Davis2015) observed that maternal reports of depressive symptoms were associated with cortical thinning, in prefrontal, medial postcentral, lateral ventral precentral, and postcentral regions of the right hemisphere; the association of depressive symptoms at 25 gw were the strongest. Moreover, cortical thinning in prefrontal areas of the right hemisphere mediated the association between maternal depression and child externalizing behavior. The observed pattern of cortical thinning seemed to be similar to patterns in children, adolescents, and depressed patients (Sandman et al., Reference Sandman, Buss, Head and Davis2015). According to the authors, the observed cortical thinning in children born to mothers with higher depressive symptoms during pregnancy may reflect accelerated brain maturation (Sandman et al., Reference Sandman, Buss, Head and Davis2015, p. 331).

Sarkar et al. (Reference Sarkar, Craig, Dell'Acqua, O'Connor, Catani, Deeley and Murphy2014) performed dMRI in preschoolers of women who underwent amniocentesis in a London clinic. Retrospectively assessed self-report of stress during pregnancy (measured at 17 months after birth) was associated with increased FA in the right uncinate fasciculus and decreased radial diffusivity in the right uncinate fasciculus, in 6- to 9-year-old children. These changes in WM microstructure were suggested to reflect hypermyelination in the uncinate fasciculus, which links the limbic region with the prefrontal cortex. Self-reported stress was not associated with control tract properties.

In the study by Davis, Sandman, Buss, Wing, and Head (Reference Davis, Sandman, Buss, Wing and Head2013), the effect of prenatal exposure to betamethasone (a synthetic glucocorticoid for fetal lung maturation, prescribed to women at risk for preterm delivery) administered between 24 and 34 gw (two doses of 12 mg, intramusculatory, 24 h apart) was examined. Only children born >37 gw were included. Fetal glucocorticoid exposure was associated with bilateral cortical thinning in several regions (left insula, left supramarginal gyrus, left transverse temporal cortex such as the cingulate cortex, frontal regions, and the superior parietal cortex) as well as with unilateral thinning in several regions. The rostral anterior cingulate cortex, which is important for regulation of stress and emotions, showed the largest group differences; that is, it was 30% thinner in the exposed group. Furthermore, in the control group children with more affective problems had a thinner left rostral anterior cingulate cortex. The authors conclude that prenatal GC exposure alters the trajectory of fetal brain development, which may be a risk factor for the development of mental health problems

Results in adolescents and adults (Ages: 15–40 years)

In a Belgium study that recruited pregnant women in 1986 and 1987 in a university hospital, and in which self-report questionnaires were completed at 12–22 gw, 23–31 gw, and 32-40 gw, male offspring was examined at 17 and 20 years of age. It was found that maternal anxiety at 12–22 gw was positively associated with less efficient endogenous decision making, as reflected in EEG measures, at age 17 (Mennes, Van den Bergh, Lagae, & Stiers, Reference Mennes, Van den Bergh, Lagae and Stiers2009). As fMRI may have an important role in understanding pathophysiologic processes by analyzing the brain areas activated while performing specific tasks, a task-related fMRI study was conducted in the 20-year-olds. Results indicated that in contrast to offspring exposed to low or medium levels of maternal anxiety during pregnancy, in the offspring exposed to high maternal anxiety in pregnancy, a number of right lateralized clusters, including the inferior frontal junction, were not modulated during endogenous cognitive control tasks.. Moreover, in this cohort, prenatal exposure to maternal anxiety at 12–22 gw also was found to be associated with increased perception of dyspnea (i.e., shortness of breath or breathlessness) at age 28 (von Leupoldt et al., Reference von Leupoldt, Mangelschots, Niederstrasser, Braeken, Billiet and Van den Bergh2017), which may indicate increased sensitivity of the autonomous nervous system.

Favaro, Tenconi, Degortes, Manara, and Santonastaso (Reference Favaro, Tenconi, Degortes, Manara and Santonastaso2015) examined effects of maternal life events stress during pregnancy in healthy volunteers, all woman, between the age of 15 and 44. Stress experienced during pregnancy was retrospectively measured with a semistructured interview administered to the mothers of the participants. Greater maternal life event stress was associated with decreased GM volume in left medial temporal lobe (MTL) and both amygdalae, but not total volume of amygdala nor with GM or total volume of the hippocampus. Furthermore, life event stress during pregnancy was positively correlated with FC of the left medial temporal lobe and with the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex, which is connected to the default mode network (Qin et al., Reference Qin, Duan, Supekar, Chen, Chen and Menon2016; Teipel et al., Reference Teipel, Bokde, Meindl, Amaro, Soldner, Reiser and Hampel2010). FC between the left MTL and part of the left medial orbitofrontal cortex partially explained variance in offspring depressive symptoms. All results remained the same when only data from subjects over the age of 18 were analyzed.

Conclusion: Prenatal Stress Alters Brain Developmental Trajectories

We reviewed prospective longitudinal studies examining whether prenatal exposure to maternal distress is associated with offspring brain development as measured with different brain imaging techniques, from birth until adulthood. Most studies used self-report distress questionnaires as predictors, while other studies used a physician's diagnosis based on medical chart information (Scheinost, Kwon, et al., Reference Scheinost, Kwon, Lacadie, Sze, Sinha, Constable and Ment2016), a diagnostic psychiatric instrument (Field et al., Reference Field, Diego, Hernandez-Reif, Figueiredo, Deeds, Ascencio and Kuhn2010; Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Mendoza, D'Anna, Zerbe, McCarthy, Hoffman and Ross2012; Lusby et al., Reference Lusby, Goodman, Bell and Newport2014, Reference Lusby, Goodman, Yeung, Bell and Stowe2016), or a physiological variable (Buss et al., Reference Buss, Davis, Shahbaba, Pruessner, Head and Sandman2012; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Sandman, Buss, Wing and Head2013) as predictor. Among different MRI-based techniques, sMRI such as voxel-based morphometry was used to quantify GM and WM volumes, while dMRI detects alterations in WM structure and indirectly in the architecture of fiber pathways. Finally, fMRI investigates brain activations in specific brain regions during cognitive and sensory tasks, and in FC when at rest, while task-related ERPs and rs-EEG records the electrical brain activity with superior temporal but lower spatial resolution compared to fMRI.

Structural brain alterations in the aftermath of prenatal stress are observed in the neonate and until adulthood. In the neonate, maternal distress is associated with changes in the WM microstructure in the amygdala, volume changes in amygdalae and hippocampus, which were influenced by variations in offspring BDNF gene and its methylation patterns (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Pan, Tuan, Teh, MacIsaac, Mah and Holbrook2015; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Rifkin-Graboi, Chen, Chong, Kwek, Gluckman and Meaney2013; Rifkin-Graboi et al., Reference Rifkin-Graboi, Bai, Chen, Hameed, Sim, Tint and Qiu2013), in WM microstructural changes and cortical thickness changes in prefrontal and parietal regions and corticolimbic structures of which some were influenced by variations in offspring COMT and offspring epigenome (Qiu, Tuan, et al., Reference Qiu, Tuan, Ong, Li, Chen, Rifkin-Graboi and Gluckman2015; Rifkin-Graboi et al., Reference Rifkin-Graboi, Meaney, Chen, Bai, Hameed, Tint and Qiu2015). Next to inducing atypical amygdala–prefrontal connectivity (Posner et al., Reference Posner, Cha, Roy, Peterson, Bansal, Gustafsson and Monk2016), reduced hippocampal growth effects in infants (Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Rifkin-Graboi, Chen, Chong, Kwek, Gluckman and Meaney2013), and larger right amygdalar volume in female preschoolers (Wen et al., Reference Wen, Poh, Ni, Chong, Chen, Kwek and Qiu2017), maternal distress was also related to microstructural WM changes, that is, lower diffusity in frontal and temporal regions in preschoolers (Lebel et al., Reference Lebel, Walton, Letourneau, Giesbrecht, Kaplan and Dewey2016), and in the limbic–prefrontal region in childhood (Sarkar et al., Reference Sarkar, Craig, Dell'Acqua, O'Connor, Catani, Deeley and Murphy2014). GM volume reduction was seen in several cortical areas and in the cerebellum in childhood (Buss et al., Reference Buss, Davis, Muftuler, Head and Sandman2010; El Marroun et al., Reference El Marroun, Tiemeier, Muetzel, Thijssen, van der Knaap, Jaddoe and White2016; Sandman et al., Reference Sandman, Buss, Head and Davis2015), and in the left MTL and both amygdalae in adulthood (Favaro et al., Reference Favaro, Tenconi, Degortes, Manara and Santonastaso2015). Larger cortical surface area in a frontal region and gyrification changes (becoming insignificant after corrections for covariates) were also observed (El Marroun et al., Reference El Marroun, Tiemeier, Muetzel, Thijssen, van der Knaap, Jaddoe and White2016). Furthermore, maternal cortisol in pregnancy was associated with larger amygdala volume in children (Buss et al., Reference Buss, Davis, Shahbaba, Pruessner, Head and Sandman2012) while betamethasone intake was related to bilateral cortical thinning (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Sandman, Buss, Wing and Head2013).

With regard to the functional measures, rs-EEG studies point to association of maternal distress in pregnancy to greater relative right frontal EEG activation, which, however, is in some studies only seen in infants of mothers with high postnatal depressive symptoms or with greater postnatal than prenatal symptoms (Field et al., Reference Field, Diego, Hernandez-Reif, Figueiredo, Deeds, Ascencio and Kuhn2010; Lusby et al., Reference Lusby, Goodman, Bell and Newport2014, p. 584; Lusby et al., Reference Lusby, Goodman, Yeung, Bell and Stowe2016; Soe et al., Reference Soe, Wen, Poh, Li, Broekman, Chen and Qiu2016). Rs-fMRI studies show that prenatal exposure to maternal distress amplifies the decreased amygdalar–thalamic FC seen in preterm born neonates (Scheinost, Kwon, et al., Reference Scheinost, Kwon, Lacadie, Sze, Sinha, Constable and Ment2016) and increased FC of amygdala with several cortical and subcortical regions (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Pan, Tuan, Teh, MacIsaac, Mah and Holbrook2015) in 6-month-olds, while rs-fMRI studies conducted in adulthood reveal changes in FC in large-scale intrinsic networks such as DMN (Favaro et al., Reference Favaro, Tenconi, Degortes, Manara and Santonastaso2015). Task-related EEG (ERPs) in infants show that prenatal exposure to maternal distress has an effect on specific ERP components indicating altered auditory attention and processing (Harvison et al., Reference Harvison, Molfese, Woodruff-Borden and Weigel2009) diminished inhibition during sensory gating (Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Mendoza, D'Anna, Zerbe, McCarthy, Hoffman and Ross2012), enhanced vigilance to fearful vocalization (Otte et al., Reference Otte, Donkers, Braeken and Van den Bergh2015), to standard sounds (van den Heuvel et al., Reference van den Heuvel, Donkers, Winkler, Otte and Van den Bergh2015), and to neutral pictures (van den Heuvel et al., in press); they reveal specific deficits, such as in endogenous cognitive control in male adolescents (Mennes et al., Reference Mennes, Van den Bergh, Lagae and Stiers2009) an effect that moreover is confirmed by task-related fMRI measures (Mennes, Van den Bergh, Sunaert, Lagae, & Stiers, Reference Mennes, Van den Bergh, Sunaert, Lagae and Stiers2016) in early adulthood.