Between 1927 and 1929, a period spanning the tenth anniversary of the end of the Great War and Czechoslovak independence, six novels and theatrical plays appeared in Czech with the ‘Green Cadres’ as their subject.Footnote 1 Though almost entirely forgotten today, the Green Cadres – or Green Guards – would have been familiar to many readers in interwar Czechoslovakia. Formed of army deserters overwhelmingly from rural areas, these organised and armed bands menaced the Habsburg authorities in the final year of the war from their strongholds in the forests and mountains of the hinterland.Footnote 2 They were most formidable in the monarchy’s southern ‘crown lands’ or provinces, particularly in Croatia-Slavonia where they numbered in the tens of thousands.Footnote 3 In the mostly Czech crown lands of Bohemia and Moravia they were far fewer, though still likely in the many thousands, and less threatening. Everywhere they were the subject of fantastic rumours during the apocalyptic end phase of Austria-Hungary and villagers looked to them with hope and anticipation as potential liberators. Yet the Green Cadres stood in the shadows of the 1918 ‘national revolution’ that inscribed an unprecedented state on to the map of Central Europe and swept Professor Tomáš G. Masaryk to power as its first president cum philosopher king. They had no meaningful contact with Masaryk’s émigré movement or with the domestic wartime conspiracy (subsequently much exaggerated) that supported it. Nor were they connected to the Czechoslovak legions, the volunteer divisions of Czech and Slovak POWs and front deserters who chose to fight on the Entente side knowing full well the terrible punishment meted out to traitors in the Habsburg Army. Moreover, while the legionaries were valorised as the heroes of Czechoslovak independence – the central protagonists in the myth of anti-Austrian resistance and unity – the Green Cadres appeared to disintegrate soon after the war’s end and largely receded from view. Why did they appear a decade later on the bookshelves and stages of the young republic? What did their reappearance mean?

This article contends that the Green Cadres were an important factor in the contested memory of the First World War in interwar Czechoslovakia.Footnote 4 Above all, they were emblematic of a distinctly rural set of issues and concerns, transcending the borders of the new state, to which historians have paid scant attention. The tenth anniversary of state independence prompted a mixture of triumphalism and soul searching that brought into focus the country’s achievements as well as its blind spots and social tensions. The Green Cadres were cast as the rural protagonists of both tendencies. While some authors endeavoured to reconcile the Green Cadres to the grand narrative of Czech emancipation – whether as ethnic Czech villagers, pan-Slavic sympathisers or Moravian regional patriots – others underscored the rift that separated them from the urban nationalist bourgeoisie, casting the forest based deserters as an alternative site of liberation. Either way, the importance of the Czech nation was uncontested, but what sort of activism or politics would best serve it was an unsettled matter. The interpretive battles over the Green Cadres formed part of a wider search for an integrative, usable wartime past during Czechoslovakia’s formative years. The task proved Sisyphean due not only to German, Slovak and Magyar resentment but also because of the fissile nature of the Czech national project itself. This was a prominent theme in much communist-era historiography, which emphasised the working-class and peasant challenge to the ‘bourgeois republic’.Footnote 5 Yet the Green Cadres have received little more than passing notice.Footnote 6 The challenge they embodied has not been explored in the burgeoning scholarship on how the First Czechoslovak Republic was less a functioning democracy than a mini-empire.Footnote 7

More broadly, this article contends that recovering rural modes of war experience and war memory is crucial to understanding the political, social and cultural legacies of the First World War. It is, in fact, difficult to separate experiences of war from the memory of them. Historians of twentieth-century war and memory now recognise that ‘exiting wars’ has been a complex process that defies neat distinctions of ‘before’ and ‘after’, and furthermore that ‘the demobilisation of body and mind depends on the social situation, the circumstances of the conflict, the extent of the preceding mobilisation and the degree of the totalisation of war’.Footnote 8 Yet the rural social situation has hardly entered into such cultural historical considerations. In contrast, an older social historical literature showed that peasant conscripts formed the bedrock of the armies mobilised between 1914 and 1917 and that they often expected, as reward for their service, radical social change, in particular an equitable redistribution of land.Footnote 9 Such expectations led to disparate and consequential political outcomes, such as the emergence of agrarian communism in Polish southeast Galicia, the triumph of fascism in the Po Valley of Italy or the hegemony of agrarian populism in Croatia. Disgruntled peasant soldiers could even forcibly end a belligerent power’s war effort, as in the case of the Russian army’s spectacular disintegration in 1917 or the 1918 Radomir Rebellion in Bulgaria.Footnote 10 While useful studies exist on the Agrarian movements that flourished in some places in the 1920s,Footnote 11 few have highlighted peasants’ own interpretations of the war and how these shaped politics and culture.Footnote 12 Such an approach can illuminate much about the brittle new order constructed between the wars, even in countries like Czechoslovakia that were relatively urban and industrial.Footnote 13 Methodologically, it requires unearthing what Guy Beiner in his study of social memory and folk history in the rural west of Ireland calls ‘alternative vernacular histories’, which may persist alongside mainstream and professional histories.Footnote 14 The difference between these genres is often manifest in the divide between print and oral culture, with the latter capable of preserving ‘traditions of social conflict’ in songs, ballads and tales for centuries.Footnote 15 But in the more literate twentieth century, vernacular versions of events begin to find their way into print, sometimes with the effect (intended or not) of unsettling dominant historical narratives.

The Green Cadres present a revealing case with which to explore these themes. The ambiguity of their aims and deeds – in contrast to the full-throated triumphalism surrounding the Czechoslovak legionaries, about whom there is a voluminous literatureFootnote 16 – along with their rural spheres of action, raised difficult questions about their, and by extension the peasantry’s, commitment to the Republic. To chart the contested memory of the Great War and the cultural-ideological work that the shadowy deserters became burdened with in the years after their ostensible disappearance, this article sets the memory of the recent past alongside the empirical record. Largely forgotten novelists, dramatists and memoirists placed the Green Cadres in contrasting narratives about the Czechoslovak state, the Czech nation, the Slavic peoples and the emancipatory potential of all these things. Such narratives varied in their faithfulness to what actually happened during the chaotic and in places violent end phase of Austria-Hungary. Of course, to an extent, the empirical record was itself culturally constructed and freighted with ideological baggage, a process that is particularly evident in the profusion of village chronicles in the 1920s. While the foregoing discussion recovers as accurately as possible what the Green Cadres did, it is especially concerned with the memory of them and what it meant. This approach arguably has special significance for Central and Eastern Europe, where the process of exiting the war was particularly fraught.

More so than in the established nation states of Western Europe, the new states of East Central Europe that arose from the rubble of shattered dynastic empires were still fighting the First World War well into the interwar period. This was true in a literal sense, especially on the fringes of the former Russian Empire.Footnote 17 But in a cultural sense, states that ostensibly stopped fighting in 1919–20 when the Paris peace treaties settled their borders were still locked in battles of legitimacy.Footnote 18 While the Western powers and their societies wanted to know how and why the war had started (what could have justified slaughter on such a scale?), countries in Central and Eastern Europe were particularly concerned with how and why it ended. Who was most responsible for liberation, or, in the case of the ‘vanquished’, who was to blame for defeat? Culture wars followed the fighting on the fronts, remobilising whole populations. In a relatively democratic, highly literate society like Czechoslovakia (especially the western provinces of Bohemia and Moravia), even peasants were called up again in service of contrasting aims. Their chequered involvement in the Green Cadres movement and the radical threat they posed could only be assimilated to the narrative of unified national resistance with the greatest difficulty.

Part I: Consensus

On 28 October 1918 the Czechoslovak Republic was declared in Prague by an alliance of leading Czech politicians acting in loose concert with the Geneva based Czech National Council under Masaryk and Edvard Beneš’s leadership. News of this epochal event quickly reached cities and towns across Bohemia and Moravia but trickled into villages more slowly. In rural southeast Moravia, in the historic regions of Slovácko and Valašsko, it was generally not until the following day that people learned of the ‘state revolution’ (státní převrat). These regions witnessed the highest rates of the hinterland desertion in the final year of the war and the formation of the largest groups of Czech Green Cadres. By the last months of the war, astonishing numbers of Austro-Hungarian soldiers had deserted in uniform from the army. In autumn 1918 one high-ranking Habsburg official estimated that the number of deserters at large in the hinterland had reached a quarter of a million.Footnote 19 Scores of thousands of them became Green Cadres. Those who did were often overstaying periods of leave (Urlaubsüberschreiter) and took refuge in the forests for protection against the gendarmes and military units sent to apprehend them. A significant number of them were recent returnees from internment in Russia. From late 1917 the Bolsheviks could no longer administer the vast network of POW camps they inherited and hundreds of thousands of Austro-Hungarian soldiers started out westward by any means possible. The frosty welcome they received upon their return as potential carriers of the ‘bacillus of revolution’ as Lenin put it, the miserable provisioning and clothing they endured in an increasingly rickety military organisation and the prospect of a return to the front were all compelling reasons to desert.Footnote 20 They awaited the end of the war with a mixture of grim resignation and utopian anticipation for what the future would bring.

News of what happened in Prague brought the Czech Green Cadres out of hiding. The euphoric celebrations that greeted the news on 29 October generally followed the same pattern across southeast Moravia. Czech citizens gathered on village greens and small town squares to sing patriotic songs such as ‘Where is My Home?’ (Kde domov můj – the current Czech national anthem), ‘Hey Slavs’ (Hej, Slované – a pan-Slavic staple) and, perhaps due to the region’s geographic and cultural proximity to Slovakia, ‘Lightning over the Tatras’ (Nad Tatrou se blýska – the current Slovak national anthem).Footnote 21 Local notables organised lantern processions that culminated in the ceremonious removal of the Habsburg double-eagle insignia from post offices and other public buildings and the hoisting of ‘national’ red-white flags. In the Slovácko districts of Kyjov and Hodonín, where the Green Cadres were especially numerous, the deserters emerged from the forests and jubilantly returned to their home villages. In Kyjov itself, reported the local chronicler, the ‘Green Guard’ was responsible for ‘lots of merriment and humour and even appeared with its own flag’. After speeches were delivered from the church steps on the main square, ‘a procession proceeded through town bearing comical effigies of the Austrian regime; the eagles, badges of our centuries-long servitude were carried at the head of the parade and then thrown into the creek’.Footnote 22

These events were captured in village chronicles, an important medium through which the recent wartime past, and the role played therein by the Green Cadres, was naturalised and consigned to history. While some towns and villages had long kept such records, a January 1920 law (zákon č. 80/1920) made record keeping obligatory for all parishes in the republic. The statute required each village to assemble a commission that would appoint a chronicler (§2), ensuring that the man charged with recording local events was properly vetted. The responsibility usually fell to a local schoolmaster or district school inspector; a figure who, since Habsburg days, was often a reliable middle-class nationalist.Footnote 23 Chroniclers apparently felt compelled to narrate local wartime events with reference to the dominant myth of Czechoslovak democracy, unity and anti-Austrian resistance emanating from Masaryk and Beneš’s ‘Castle’.Footnote 24 The myth was thus not merely broadcast from the Castle’s press bureau but also appears to have been built consensually from the ground up. Whenever possible annalists remarked on the pre-war national consciousness of the village’s inhabitants, the heroism of local legionaries and the general enthusiasm that greeted the news of independence. In many places this narrative needed to be adapted to local conditions, particularly in southeast Moravia, where Green Cadres often outnumbered the local legionaries. In Moravská Nová Ves, which boasted twenty-three legionaries but at least thirty Green Cadres, the head teacher Vilém Rosendorfský wrote, ‘the Czech spirit had fully awakened. Soldiers on leave were reluctant to return to the battlefield and many disappeared – they hid in attics, hayracks, cellars and forests. People sometimes brought them food to a specific place, or out of caution they came for it themselves. People called them the “Green Cadres”.’Footnote 25

These bearers of the ‘Czech spirit’ had, according to many accounts, contributed to the national cause by undermining the Austro-Hungarian army. That they ‘helped to accelerate the end of the war and the collapse of Austria-Hungary’ was a common enough refrain in village chronicles.Footnote 26 In this, some testimonies alleged, they were steered benevolently, if indirectly, from above by independence-minded Czech army officers and gendarmerie commanders. In fact, the gendarmerie was often cast as a bastion of pro-Austrian sentiment (rakušáctví) and the merciless bane of the deserters. Rare incidents in which gendarmes used lethal force against deserters resonated far and wide and echoed into the interwar period. The news at harvest time in 1918 that Josef Procházka, a deserter from Nenkovice near Kyjov, was shot dead by a gendarme steps from his home ‘caused a sensation in the village and also in neighbouring parishes’.Footnote 27 But there were some gendarmes who turned a blind eye to soldiers overstaying periods of leave, or even warned them about hostile patrols. Marcel Bimka, a villager from the Kyjov area who later joined the fearsome Green Cadre group in the Buchlov Forest, was able to spend much of 1917 at home in Šardice thanks to the wilful neglect of the local gendarme captain.Footnote 28 Václav Šlesinger, a gendarme officer during the war, became the protector of the Green Cadres in the Brno area by secretly instructing likeminded commanders to warn the deserters about impending military raids on their hideouts.Footnote 29 Similarly, commander Barek near the northern Bohemian town of Železný Brod was the ‘guardian angel’ of the local Green Cadres and thereby earned himself the affectionate nickname ‘green daddy’ (zelený táta).Footnote 30

If the gendarmerie operated on a local level, army officers committed to Czech independence harboured grander designs for the Green Cadres in Moravia. In his 1933 memoir Richard Sicha recalled that he and a handful of other Moravian Czech officers deemed the support of the deserter movement necessary to stage an eventual armed insurrection in the major towns of the Bohemian Lands.Footnote 31 To that end they issued furloughs indiscriminately and coordinated the December 1917 escape of enlisted men with two ground machine guns from a moving train southeast of Brno. Direct communication with the Green Cadres in Slovácko was out of the question, claimed Sicha, since ‘one garrulous Švejk’ could spoil the whole operation.Footnote 32 While it is possible that Sicha’s intense interest in the Green Cadres was a retrospective invention, it bespeaks the perceived need to address their memory; indeed, Sicha devoted the entire second chapter of his book to the deserter movement. The Prague-based Major Jaroslav Rošický, in his account published the same year as Sicha’s, also viewed the Moravian Green Cadres as an integral part of any armed power seizure in 1918, but events outpaced his planned trip to Slovácko at the time, and he never came into contact with them.Footnote 33 Regardless of how accurate these recollections are, the Green Cadres’ commitment to the Czech cause was apparent in November 1918, when many of them enlisted in the Slovácko Brigade. This volunteer division formed in Hodonín under the leadership of Moravian Czech nationalist officers, including Šlesinger, was premised on the notion that regional loyalties ought to be the basis of the new Czechoslovak army.Footnote 34 By late January 1919 it counted 274 officers and 5,262 men. While the regionalist vision proved illusory (the Slovácko Brigade was reorganised into a smaller Slovácko Regiment in June 1919, which was then dissolved completely in 1920), the Brigade, made up overwhelmingly of former deserters from the Habsburg army, distinguished itself by securing the southern borders of the new state and maintaining order in mixed nationality districts. Influenced and commanded by reliable Czech officers and nationalist activists, the Green Cadres would play an important – if supporting – role in the making of Czechoslovakia.

In this spirit, the dramatist Josef Liška Doudlebský’s play The Green Guard, intended for Czechoslovakia’s tenth anniversary celebrations, underscored the cooperation of Czechs from all backgrounds in undermining Austrian rule. In the forward to his paean to Czech unity he explained:

Much has already been written and said about our ‘foreign resistance’, but relatively little about the internal one, so to speak; and yet how many conscious Czechs there were (and thank God there were so many!) … This play is dedicated to all of those tiny grubs gnawing slowly but inexorably through the foundations of the Habsburg throne and rotten Austria, all those who through open or secret hostility fought for Our Republic.Footnote 35

Doudlebský’s chief protagonist is the gentlemanly landowner and Czech patriot Emil, who becomes the protector of the local peasant lads of the Green Guard in the hills of northeast Bohemia. The deserters thus act in concert with the leaders of the Czech resistance (Emil is connected to the Prague based Maffie organation), an alliance which, according to the decent Czech clerk Klein, has also been forged in Moravia.Footnote 36 In the final scene, the local Green Guards pay homage to their patron and, at Emil’s encouragement, swear an oath of loyalty to the republic.Footnote 37

Jan Václav Rosůlek’s tragic novel, Noha, Colonel of the ‘Green Cadre’, eschewed the ebullient tone of Doudlebský’s play. Yet the eponymous main character, a recent returnee from Russian internment in 1918, is also convinced that the domestic resistance should complement the heroics of the legionaries. ‘The nation must also show its dissatisfaction at home – not just abroad’, he muses.Footnote 38 The plot, which is based more on the mutiny of the mostly Czech regiment in Rumburg/Rumburk in May 1918 (a rifleman named Noha was one of its leaders) than on the Green Cadres, involves Noha’s desertion and assembling of a small fighting force that embarks on an ill-starred expedition to liberate Prague from Austrian rule.Footnote 39 He and the men that remain loyal to him are caught and killed. Meanwhile, many of the deserters abandon the cause early on to plunder the countryside. This ‘Green Cadre’ is ultimately less of a fighting force on the ground than Noha’s dutifully patriotic ideal. It denotes an inchoate, less glamorous and do-it-yourself form of anti-Austrian and anti-war resistance. Nonetheless, it is a resolutely Czech ideal, which Rosůlek contrasts with Russian Bolshevism and the brutal militarism of the multi-ethnic Habsburg army, perhaps best embodied by the ‘Romanian gypsy’ NCO who oversees Noha’s execution at the Terezín prison.Footnote 40

There was no denying that the Green Cadres belonged to a different sort of national resistance, one that was elemental, undisciplined and plebeian. The officer Sicha considered this to be only natural since the Green Cadres manifested the resistance of the ‘simple Czech soldier’.Footnote 41 An engineer from the Železný Brod district remarked that there were two forms of domestic resistance in his area during the war: ‘one, tied to our circle, which was committed, patriotic and religious; and the other, which arose from shirking [ulejváctví] and for a lark [ze srandy] but also from patriotic feelings. The ‘Green Cadres’ worked at home on the fields and in trades, while we worked with our intellect’.Footnote 42 Indeed, there was something distinctly unserious about the deserters to many observers. For one thing they sometimes materialised from their sylvan refuges to attend village dance parties.Footnote 43 This was a common enough occurrence to feature in some mainstream Czech interwar fiction, including a 1939 book by the hugely popular Karel Poláček.Footnote 44 As peasants tied to the land, they often took a break from the resistance to help their families in the fields.Footnote 45 Above all, according to Jan Bělník, the chronicler of the village Malá Vrbka – exceptionally, a farmer himself – they were ‘our lads’ who did not want to fight any longer and liked a bit of fun.Footnote 46

Because the Green Cadres often seemed distant from, or oblivious to, the manoeuvrings of Czech independence movement leaders, some authors took a different tack than Doudlebský and Rosůlek, finding virtue in their primitive and recalcitrant nature. Josef Pavel’s 1927 adventure novel The Green Cadre placed the deserters in a timeworn tradition of social banditry in Slavic East Central Europe. The story he tells is not a Czech one but a Slavic one, featuring a Ukrainian deserter named Mychajlo Bunčuk. According to one approving reviewer, Pavel’s novel faithfully describes ‘the wartime sufferings and miserable life of the Slavic population in thrall to Austria’.Footnote 47 Besides becoming an effective commander of the Green Cadre in the Carpathian forests, Bunčuk steals from the rich to give to the poor, just like – as Pavel dutifully points out – his putative eighteenth-century antecedents, the Slovak Juraj Jánošík and the Ruthenian/Ukrainian Oleksa Dovbuš.Footnote 48 The novel trades heavily in anti-German and anti-Magyar sentiment, as well as in anti-Semitic stereotypes. Bunčuk’s Cadres are the obverse of such prejudices: a picture of Slavic solidarity, with Poles and Czechs fighting alongside the humble Ukrainian peasants against Habsburg oppression and militarism. But the pan-Slavic idyll is shattered after the war’s end. The Ukrainian Green Cadres form the core of the army that battles both General Józef Haller’s Polish army and the Russian Bolsheviks in an attempt to establish a Ukrainian state. While valorising the Green Cadres, Pavel to an extent also exoticisises them, locating them far from the Bohemian Lands in the misty Carpathian forests where romantic bandit heroes still roam. This was, after all, the territory of the renowned highwayman Nikola Šuhaj, who at the end of the First World War became widely feared and admired in the easternmost province of interwar Czechoslovakia, Subcarpathian Ruthenia. In Ivan Olbracht’s famous 1933 novel The Bandit Nikola Šuhaj, the protagonist early on briefly considers joining the Green Cadres.Footnote 49

Green Cadres that were both virtuously primitive and Czech featured in Vojtěch Rozner’s 1928 debut novel, Revolt of the Cottages (Vzpoura chalup). Unlike the authors discussed above, Rozner doubtless had some first-hand experience with the deserter movement. In 1918 he was a fourteen year old boy in the village of Hýsly in the Kyjov district, where his father Benedikt was schoolmaster and, in the 1920s, village chronicler.Footnote 50 The teenage Vojtěch composed patriotic-sentimental poetry for the 1922 unveiling of a monument to the eighteen war dead of Hýsly. Perhaps dissatisfied with his father’s cursory treatment of the Green Cadres in the official history of the village (all of one sentence), he decided to write a novel describing how they energised the rural common folk of southeast Moravia. This was, in social terms, a mass peasant uprising:

The cottages rose up. It was only too clear and understandable. They straightened their unkempt hair, lifted up their heads, defiant like bandits. They did not recoil any more from the fact that they are such puny, deformed and dilapidated runts, for they recognised that there is strength in numbers. They recognised that the power and size of those mighty palaces that command half the world is very problematic; indeed it is questionable, hanging on a weak thread. … Those small warped cottages recognised that they are in fact that half of the world that does not need to let itself be ordered around by the ones they feed.Footnote 51

The heroic ‘commander of the Green Cadre’ Karel Zach is also a patriot who decorates his uniform with Slavic red and white colours and sports a green linden leaf (symbolising Slavs, but also the Green Cadre apparently) in his buttonhole. The ‘army of deserters’ he commands is reminiscent of the Blaník knights, a legendary army of Czech warriors sleeping under a Bohemian mountain until it is called to deliver the nation in its hour of greatest need.Footnote 52 The Green Cadres, according to this account, are ultimately at least as important as the émigré Czechs and legions in bringing about the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian army, ‘for not everyone had the opportunity to be captured [by the enemy]. Some had to carry out the revolution at home. It was often even more courageous and dangerous’.Footnote 53 The verisimilitude of Rozner’s portrayal lies in his clear familiarity with the Cadres’ modus vivendi in the final war year: their warning system against gendarme patrols, their secret candlelit village meetings, their control of an extensive polyp-shaped territory centred on the Buchlov forest. It is all the more plausible, therefore, that the humble Moravian villagers did, as Rozner suggests, see their estate empowered and ennobled by the Green Cadres movement and viewed its national significance refracted through the prism of regional identity. (As the hero Zach says, marvelling to his tearful mother as they look at a map together, ‘Slovakia … it is all Slovakia … and it is ours’.)Footnote 54 Such heterodoxy notwithstanding, national unity triumphs in the end as Zach and his men enlist in the Slovácko Brigade and the village priest converts from Catholicism to the Czechoslovak national church.

Part II: Dissent

Yet the ‘revolt of the cottages’ often assumed forms that were hardly congenial to nationalist elites and the urban bourgeoisie. The small agricultural town of Hluk south of Uherské Hradiště was the scene of clashing understandings of national revolution in 1918–9.Footnote 55 A large and militant group of Green Cadres had emerged here in the final year of the war, supported by the local population. At the end of May 1918 they had attacked the town’s gendarmerie station.Footnote 56 Shortly after 28 October ‘regrettable incidents’ occurred alongside music, dancing and other celebrations.Footnote 57 On the night of 30 October a hand grenade was hurled into the living room of the gendarme commander Jančík, who had persecuted the deserters in wartime, prompting him and his family to flee the district. The Hluk chronicler, Josef Dufka, downplayed the attack explaining that, ‘the war had ended and there was freedom which needed to be celebrated, and the evil and hatred need to be vented somehow’. Two weeks later on the night of 10 November Hluk citizens looted two Jewish shops. Investigators suspected that workers returning from militarised factories in Hungary and Lower Austria were to blame, since they brought news of similar violence to their home village, riling people who had previously not been ill disposed toward the local Jews.Footnote 58

The deserters were also culpable, having forced the closure of the gendarme station with attacks on the commander Jančík’s home, his wife and his replacement, Metoděj Král. At a meeting shortly after the revolution the village priest Karel Namyslov had allegedly emboldened them, shouting ‘glory to the deserters’ (‘sláva desertérům’) – a slogan in Rozner’s novel too.Footnote 59 ‘According to the judgment of more moderate elements’, an official report stated, Namyslov’s interjection ‘strengthened the dissatisfied and unreliable portion of the population. This exclamation was certainly clumsy and unjust, because any sort of ideal Czech-national [českonárodní] stance was foreign to the deserters in question.’ Over the following months their distance from acceptable Czech nationalism seemed to only increase. In late April 1919 the fearful gendarme commander in Hluk reported that over 300 deserters were in the area and refused to enlist in the Czechoslovak army or pay any heed to him and his men. ‘Among the deserters’, he continued, ‘are those who, after the state revolution, perpetrated violence and theft on the wife of ranking commander František Janšík [sic] and a number of Jews’.Footnote 60 Their ranks swollen by radicalised workers formerly employed in Lower Austria, the deserters constituted a ‘Bolshevik movement’ that was preparing to plunder on May Day those who had prospered during the war. The district gendarmerie commander in Uherské Hradiště assured the authorities in Brno that steps were being taken to avoid social unrest. Nonetheless, in early May, the Brno military command charged the Slovácko Brigade – itself composed largely of former Green Cadres – with investigating the situation more closely but insisted that no troops were to be garrisoned in Hluk.Footnote 61

The recalcitrance of the hlučané toward the new state appeared in the more prosaic realm of agricultural production as well. In Hluk, as elsewhere, wartime requisitions had alienated the by and large loyal and politically conservative peasant population. Requisitions began in 1915 and became more frequent, targeting an ever wider range of agricultural products, until it seemed that the Habsburg state was intent on carting off villagers’ homes and public landmarks: doorknobs, copper boilers and ultimately – and painfully – village church bells. Rural people resisted by concealing food and other supplies in innovative hiding places – in chimneys, holes in the garden and the interiors of walls.Footnote 62 The Green Cadres, explained the Hluk chronicler, carried out their own requisitions on wealthy farmers, though there was some speculation that the latter were complicit since the produce prepared for the state always seemed to disappear first. Little wonder then that requisitions carried out by the Czechoslovak state were greeted with anger and disillusionment. In March 1919 the soldiers sent to oversee requisitions in Hluk were, in the disapproving words of the chronicler, ‘armed to the teeth, like some kind of robbers’. At one of the first houses they stopped at a local farmer assaulted the commanding officer. A furious crowd quickly assembled and forcibly disarmed the soldiers, throwing their rifles into the stream. Pitchfork-wielding locals chased the officers out of Hluk.

Requisitions exacerbated the real shortages felt by the Czech agricultural population during and immediately after the war. Over the course of the war Bohemia and Moravia went from having some of the highest grain yields among Austrian crown lands to being among the least productive.Footnote 63 By 1918 the yields of most major food crops (wheat, rye, barley, oats, peas, potatoes, sugar beets and flax) had dropped by 50 to 70 per cent from pre-war levels. This catastrophic collapse in production resulted from shortages of draft animals and farm labour – both mobilised for front service – as well as from a dearth of artificial fertilisers and high quality seeds, much of which had been imported before the war. While hunger affected the urban population far more, the peasantry felt increasingly squeezed between poor agricultural production and the exigencies of the wartime economy. This was the social-economic context in which the hlučané attacked representatives of both regimes in autumn 1918 and spring 1919.

In some respects the disturbances in Hluk (the name itself means ‘noise’ or ‘tumult’) in 1918–9 and the involvement of the Green Cadres were not exceptional. Retribution against gendarmes who had hunted, and occasionally killed or wounded, deserters in wartime occurred in a number of Moravian districts. In some cases, as in Kyjov, where the German-speaking gendarme commander had derisively referred to the town as ‘little Serbia’ (klein Serbien), Czech citizens felt they were evicting an unwanted outsider when the local National Council ordered him to leave.Footnote 64 Elsewhere, Czech gendarmes who had followed wartime orders became the object of special scorn as traitors. An anonymous August 1918 letter sent by deserters to the gendarmes stationed in Moravská Nová Ves near Hodonín read: ‘you lackeys of militarism! Payback time is coming for your destructive and foolish behaviour. That’s right, soon we will be doing the accounting and woe to you! … And you are Czechs? Traitors, hyenas and bloodsuckers of our nation!’Footnote 65 In the southwest Moravian town of Třebíč around fifty deserters and former soldiers stormed the district captaincy office on 4 November, demanding the handover of three gendarme commanders, two of whom were Czech.Footnote 66 Green Cadres were numerous in the area and had participated in a mass demonstration on 14 October that had spilled over into rioting and the attempted liberation of their comrades imprisoned in the town hall.Footnote 67 In places where citizens did not resort to such vigilantism they sometimes petitioned the authorities in the first post-war weeks and months in order to remove unpopular gendarmes.Footnote 68

More unsettling than the deserters’ post-war retribution against ‘Austrian’ officials was the prerogative they evidently felt to ‘requisition’ and ‘tax’ the property of the wealthy and the state. While the Hluk chronicler and others who called them ‘our lads’ were relatively sympathetic, many viewed the actions of the Green Cadres with deep ambivalence or hostility. The chronicler of Hrušky concluded that, ‘the Green Cadres did not benefit the area. Theft on the fields and in the area was rampant; when not in the fields, the soldiers committed armed robberies on trains in the station in Hrušky and nobody dared to stand against them. These armed gangs became the terror of the vicinity’.Footnote 69 The phrase ‘terror of the vicinity’ (postrachem okolí) was widely used in such records, as were references to ‘robber gangs’.Footnote 70 The chief problem was the deserters’ refusal to submit to the new state or return to civilian life immediately after 28 October 1918. The teacher from neighbouring Moravská Nová Ves who regarded the Green Cadres as a manifestation of the ‘Czech spirit’ showed little sympathy for the gangs of ‘deserters’ – likely the same men – that plundered freight trains in the vicinity following the revolution.Footnote 71 Indeed, in 1927 the state prosecutor in Uherské Hradiště brought charges against former members of the Green Cadre in Hrušky for their involvement in train robberies before and after the revolution.Footnote 72 It was ultimately of little consequence that these men had redistributed the looted goods to needy villagers who sometimes arrived with empty wagons to prearranged meeting places.Footnote 73 With the war’s end, socially minded redistribution shaded into blatant larceny and some former Green Cadres, such as the Vylášek brothers in Vřesovice (today Březovice) near Kyjov, became hardened criminals.Footnote 74 Alongside the laudatory publications of the 1920s, press dispatches appeared with titles like ‘The Green Cadre still menaces’, ‘Courtroom Report: The Třebíč Green Cadre’, and ‘100 Months in Prison for Members of the “Green Cadre”’.Footnote 75

Above all, the events in Hluk and elsewhere revealed the rural social tensions that accompanied the end of the world war and the establishment of the new republic. The war opened acrimonious new social divides between those with reliable access to food and those without.Footnote 76 People who had profited during wartime – whether by hoarding goods and selling them at black market prices (the so-called keťasi), or by holding lucrative positions in wartime supply chains and industries – were universally reviled. Tensions mounted between town and country.Footnote 77 Townsfolk accused peasants of hoarding and profiteering while villagers feared and begrudged the ‘predatory’ cities, many of whose inhabitants scavenged the countryside for food late in the war or demanded food from peasants under the threat of violence. Social resentment merged with ethnic-national difference in the case of German-speaking Jews, who were unfairly accused of having both shirked military service and exploited ordinary Czechs. In November 1918 returning soldiers and disgruntled civilians looted Jewish shops in towns across Moravia, including Hluk, Uherské Hradiště, Uherský Brod and – with lethal effects – Holešov.Footnote 78 In Uherský Brod crowds of ‘peasants’ invaded the town on 14 and 21 November armed with primitive weapons and proceeded to plunder Jewish shops and vandalise Jewish homes.Footnote 79 This was the countryside settling scores with the town.

Yet social rifts widened within Czech village society as well. The chronicler of Hrušky lamented that cottagers and landless labourers now socialised separately from the middling and prosperous farmers, themselves divided by political allegiance. Each political camp had its own pub with its own entertainment, whereas before the war, ‘the whole lot had a dance party once a month together, whether rich or poor’.Footnote 80 Organised social protest, unheard of in southeast Moravia before the war, erupted on a large scale. In 1919–20 fifteen strike waves paralysed dozens of estates in the district of Břeclav. In September 1920 land hungry peasants in four Břeclav parishes seized estates and redistributed them among themselves.Footnote 81 Such actions turned southeast Moravia into a hotbed of rural radicalism in 1920.Footnote 82 ‘The rebellious people’, stated one report from the Uherské Hradiště district, ‘are even parcelling out land among themselves. Supposedly they will follow the Russian example. Speakers at [leftist Social Democratic] gatherings declare that they will not work any longer on large estates under the current circumstances’.Footnote 83 Such revolutionary actions threatened to undermine the entire liberal bourgeois order built in part on the sanctity of private property.

But it was in the army where the legacy of the Green Cadres caused the most immediate problems. Many simply refused to join the new Czechoslovak army, despite enlistment orders. ‘In the vicinity of Třebíč’, read one report from mid-November 1918, ‘there are Green Cadres who do not want to enlist and unsettle the population’.Footnote 84 As the case of Hluk illustrates, such situations could persist for half a year after independence. On the other hand, those that did enlist often threatened to corrode the army’s core values of discipline and hierarchy. Although it earned some plaudits, the Slovácko Brigade was a consistent source of frustration to the army authorities in Brno.Footnote 85 Its commander, Cyril Hluchý, was hard pressed from the beginning to instil discipline among the new recruits. In early November he dissolved the officers’ mess and their right to have servants as a palliative against ‘Bolshevism’ among the enlisted men.Footnote 86 Such steps were framed as a ‘democratisation’ of the army under pressure from below and corresponded to a broader campaign for the army to reflect the democratic ethos of the new state.Footnote 87 But conditions in the Brigade continued to worsen over the first months of the republic. In January 1919 a lieutenant colonel serving with the Brigade in Břeclav warned Brno of deteriorating discipline and the renewed possibility that the men ‘might form Green Cadres’, which, in his cryptic summary, would pose ‘a danger to the whole empire [říše]’.Footnote 88 His revealing characterisation of the new state as an ‘empire’ – perhaps the result of habit and nothing more – might serve to illustrate the persistence of ‘Austrian’ mentalities under the new democratic system. The widespread perception that such mentalities endured in certain elite circles fanned social unrest.

Czechoslovakia attempted to neutralise the menace of rural radicalism through far-reaching land reform. This was the favoured approach across East Central Europe, where peasantries destabilised by the First World War and the shock waves of revolution in Russia expected a rapid improvement in their condition. If regimes succeeded to varying degrees in expropriating and breaking up large estates, particularly those owned by ‘foreign’ magnates (by 1930 estates over 50 hectares comprised only 10 per cent of land in Yugoslavia, 20 per cent in Czechoslovakia and Poland, 32 per cent in Romania and 56 per cent in Hungary), they were far less effective in addressing chronic rural overpopulation, low agricultural productivity, underinvestment and low prices for agricultural produce.Footnote 89 These secular economic problems were less pronounced in Czechoslovakia and certainly in the mostly Czech regions of Bohemia and Moravia. But the protracted and uneven process of reform bred discontent here too. Between 1919 and 1935 the Prague government confiscated estates greater than 250 contiguous hectares (or 150 hectares of arable land) – particularly from German and Magyar aristocratsFootnote 90 – and parcelled them out to small and medium cultivators on the basis of a lottery scheme. Legal complexities sometimes delayed the parcelling process to the chagrin of impatient peasants. This was the case in Hluk, where the local large estate owner was a member of the Liechtenstein family and head of a state that Czechoslovakia refused to officially recognise for fear of undermining the land reform.Footnote 91 Rival political parties, notably the Agrarians and the Catholic oriented People’s Party, competed for rural votes, posing as the best overseers of the reform process.

On balance, by the late 1920s and early 1930s – when most of the remembrances and representations of the Green Cadres appeared – Czechoslovakia was a stable, relatively democratic society in which Czech villagers were slowly but surely reaping the benefits of land reform and could choose between several parties that championed their interests. The rural social radicalism of the immediate post-1918 years had dissipated. Yet the Green Cadres remained an important site of memory, for they also recalled a sense of foreshortened radical possibility that was among the potent cultural legacies of the imperial collapse in Central and Eastern Europe. The end of the First World War was experienced not just as a moment of national liberation and deliverance from wartime privation but also as a moment of revolutionary openness, when it appeared that state and society could be remade from the ground up. In 1918 the Green Cadres embodied such utopian hopes in the countryside which were still vividly, if wistfully, remembered a decade later.

Utopianism and disappointment are central themes of the anarchist writer Michal Mareš’s The Green Guard from 1927. This was arguably the most important representation of the Green Cadres because there is clear evidence that the author joined the deserter movement and incorporated many of his experiences into the short novel. Born in 1893 to a working-class social democratic family in Teplice, north Bohemia, Mareš had a mostly German education, was bilingual in Czech and German and gravitated toward internationalist anarchism before the First World War.Footnote 92 As a known anti-militarist, he was kept in the hinterland in low-level bookkeeping jobs in the wartime industry, one of which was at a cannery in southwest Moravia. Here, in 1918, he came into contact with and joined the Green Cadres. This experience was a source of considerable pride after the war. In 1924, while touring Italy, he by chance met General Luigi Cadorna – the disgraced commander of the Isonzo Army that lost the battle of Caporetto/Kobarid – in a seaside restaurant. Cadorna asked him if he had ever fired on Italian troops, to which Mareš boasted that he had never spilt ‘enemy’ blood and had only exchanged fire with gendarmes as a member of the Green Cadres. The general replied coldly, ‘in my view, it was your duty not to mutiny but to follow orders and go into battle!’Footnote 93

While the exact circumstances under which Mareš joined the deserters near Dačice on the Bohemian-Moravian border remain unclear, it is likely that he – like the chief protagonist in the novel – was impressed by their humble origins and their David-like defiance of the militarised Austrian Goliath in the name of both national and social liberation. The poor villages of Sumrakov and Bolíkov, which today lie on the verge of natural reserve called ‘Czech Canada’, supply a disproportionate number of Green Guard fighters in his book:

Amid the great sea of military discipline and bloody violence those groups were tiny islands, unsettling the authorities and armed power in the hinterland, tireless and nameless heroes of the national revolution and vanguard of the coming social revolution, the landless poor and cottagers of Bolíkov and Sumrakov: the Green Guard!Footnote 94

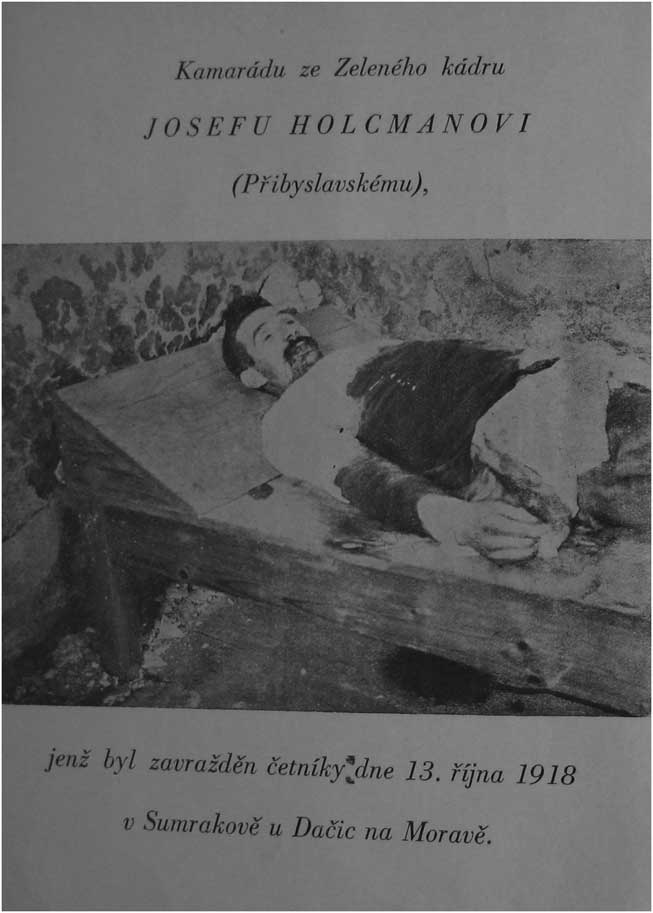

Mareš’s account is only lightly fictionalised. The Dušek brothers who appear in its pages were indeed inhabitants of Bolíkov as the names on the village’s war memorial testify [FIGURE 1]. The frontispiece features a grisly photograph of the martyred Green Guard fighter to whom the book is dedicated – Josef Holcman Přibyslavský, ‘murdered by gendarmes on 13 October 1918 in Sumrakov by Dačice in Moravia’ [FIGURE 2].Footnote 95 This fact is born out by the Sumrakov village chronicle, which bemoans the brutal murder of an ‘unarmed Czech’ and ‘hero’.Footnote 96 Přibyslavský is a transplant to the area from the Buchlov forest where he claims the Green Cadres number at least 4,000. He also is ‘a bit of a Bolshevik and man of letters’ who introduces a radical ditty to the couple dozen rebels in the Dačice area:

This Green Cadre of ours

Like stags they hunt us

But when we come from the wood into the fray

The red banner will wave.Footnote 97

Figure 1 The Bolíkov War Memorial

Source: Author’s photograph.

Figure 2 Murdered Greed Guard Fighter Josef Holcman Přibyslavský

Source: Author’s photograph.

It is especially difficult to disentangle fact from fiction in the final chapter, ‘From the diary of a guardist’. The ‘diary’ describes the violent death throes of the Austrian leviathan, the surging hopes of Green Cadres across the monarchy and a national revolution that is ultimately stillborn. While two of the Green Guard meet bloody ends in the September and October – Přibyslavský shot and Josef Holý beaten to death upon arrest – uplifting news reach the squad from far-flung locales: two regiments of Magyar soldiers sent against the Buchlov Green Cadres ended up joining them, the Slovak Green Cadres repulsed a major operation on their position in the hills near Bratislava, the Green Cadres solidified their position near Třebíč and, most importantly, the Bulgarian and Albanian fronts collapsed.Footnote 98 On 14 October, when Czech Social Democrats across Bohemia and Moravia demonstrated (unsuccessfully) for a socialist republic, the villages near Dačice hoisted national flags, but prematurely. The gendarmes escaped retribution by fleeing the town of Studené on the 27th, just as the Green Guard stormed it. The exhausted, frustrated deserters returned to their homes, but they reassembled several weeks later to defend the republic when ethnic Germans in the Znojmo/Znaim district of south Moravia attempted to secede and join their territory to German Austria. Although the operation was a success militarily, it exposed deep divides among the Czechoslovak volunteers, between the egalitarian and socialist-inclined Greens and their supercilious commanding officer – a Czech first lieutenant who was not a communist but ‘a democrat – a dog in a reformed coat with re-sewn buttons and a national rosette instead of his former imperial badge’.Footnote 99 In the final scene, the main character Jan Luka dies in the cold November forest, alone and drunk, revelling in the beauty and munificence of the woods:

O what grace! You forests, you didn’t betray the persecuted! By the time you thickets grow up, it will be different, there will be the new society for which we suffered and fought when we laid the foundations. With you it will be as with us. But before we get there we will perish, as will you; we give the old society lives, new ones: fertiliser and foundations, and you too. Battlefields, dungeons – [but also] barricades. Telegraph poles, railroad ties – lumber. The colour green – the colour of hope.Footnote 100

Mareš’s tale ends bitterly with social hierarchies resurrected under the new regime in Prague. Yet it also sounds a note of prophetic optimism – the forests harbouring the pioneers of, and resources for, a more just system in the future. For at least a decade after the end of the First World War communism seemed to the author and other Green Cadres the better alternative to ‘incomplete’ democracyFootnote 101, though what they got after the Second World War was often not to their liking. Mareš, accidentally arrested in May 1945 by Soviet agents, fulminated in the press against the ruthless expulsion of ethnic Germans from the Sudetenland and after the February 1948 communist takeover landed in prison for seven years. His portrayal of the Green Guards resonated widely enough to be the basis of a 1928 stage adaptation by the socialist dramatist Felix Bartoš. It is not clear whether Bartoš knew Mareš, or whether he too was involved in the southwest Moravian Green Cadres, but his play The Lads of the Green Cadre contains many similar characters (the names are often only slightly changed), analogous scenes and some identical dialogue, as well as featuring the same radical song.Footnote 102

The possibility of peasant deserters shaping the 1918 Czech national revolution did not seem as remote as it may today. Nor was the village based rural population as supine and conservative as in the stereotype perpetuated by urban radicals and moderate reformers alike. Certainly, as this article has shown, the southern Moravian countryside, animated by the Green Cadres in the final year of the Great War, heaved with unrest in the years following the establishment of Czechoslovakia. Authors, memoirists and chroniclers who would banish this instability roiling the bucolic, monolingual and ‘genuinely’ Czech homeland had to either overlook the radical dimension of the Green Cadres or reinterpret it as a natural, elemental response to privation that was fated to disappear in the liberal consensus of the 1920s. This was only partially successful. There was to be no easy synthesis of national consensus and social dissent in the Moravian countryside.

Silence around the Green Cadres seemed to be the preferred strategy in official commemorations of the Great War. While Czechoslovak commemoration in theory aimed at national integration, a clear hierarchy emerged in which the sacrifice of legionaries was esteemed above those who died on the front as soldiers of Austria-Hungary or in the hinterland.Footnote 103 In some places war monuments elided all differences between wartime victims – arguably a more democratic approach, though potentially another way of silencing those who did not conform to the nationalist ideal. Thus, whether a soldier died at Zborov in the Ukraine as a legionary, on the Piave River as an Austrian infantryman, by the bullets of a garrison firing squad as a traitor or fighting gendarmes as a member of the Green Cadres, he was commemorated with the rest of the war dead on such monuments. ‘They perished for our freedom’ reads the epitaph on the war memorial in Bolíkov featuring the name of the Green Cadre Karel Dušek [FIGURE 1]. Yet in spite of this silence the Green Cadres remained an uncomfortable reminder of the social disharmony and divides between town and country that accompanied the nation’s wartime tribulations and its putatively triumphant rebirth as an independent state.

Their memory was cultivated in the countryside as part of the alternative vernacular history of the Great War. Like other vernacular histories of war, rural revolt and social conflict, the story of the Green Cadres had a hopeful core – even if, in some versions, it ended in tragedy – that stemmed from the heady days of the national revolution. In some respects this matched an old pattern of peasant unrest and its legacies: the unrealised dreams of suppressed risings by the sixteenth-century Bundschuh movement in Germany, Matija Gubec in Croatia and Slovenia (1573) or Pugachev in Russia (1773–4) sustained subsequent generations. Early modern peasant identities often coalesced around these militant memories and traditions.Footnote 104 The innovation of the twentieth century was not just literacy, but also the blending of age-old yearnings for justice with new ideological prerogatives; alongside vernacular history, we might speak of vernacular ideology, as the inchoate politics of Mareš’s book suggests. The transformation was evident, for instance, among Greek peasants who resisted German occupation in 1941–4 and whose songs, though derived from the nineteenth-century klepht bandit tradition, were suffused with new communist ideals as well as a stubborn agrarian populism oriented toward private property.Footnote 105 The Czech deserters of 1918 unleashed energies and represented ideas that did not fit the liberal urban-centred nationalist mould forged by Masaryk and Beneš. Their protean utopia was not simply a world free of compulsion, or one in which the benevolent sovereign knew of all the injustices transpiring in his realm. It was also a world of egalitarian nations made up of smallholding country folk. They embodied a peculiarly rural variant of the utopian hopes that accompanied the end of empire in East Central Europe; a hopefulness that is all too easily forgotten with knowledge of the century that followed.