Introduction

Lepidoptera is one of the most diverse insect groups with currently about 160,000 described species (Kristensen et al., Reference Kristensen, Scoble and Karsholt2007; van Nieukerken et al., Reference van Nieukerken, Kaila, Kitching, Kristensen, Lees, Minet, Mitter, Mutanen, Regier, Simonsen, Wahlberg, Yen, Zahiri, Adamski, Baixeras, Bartsch, Bengtsson, Brown, Bucheli, Davis, De Prins, De Prins, Epstein, Gentili-Poole, Gielis, Hättenschwiler, Hausmann, Holloway, Kallies, Karsholt, Kawahara, Koster, Kozlov, Lafontaine, Lamas, Landry, Lee, Nuss, Park, Penz, Rota, Schintlmeister, Schmidt, Sohn, Solis, Tarmann, Warren, Weller, Yakovlev, Zolotuhin, Zwick and Zhang2011), although the total number of extant species is estimated to be around half a million (Kristensen et al., Reference Kristensen, Scoble and Karsholt2007). Within this vast group of insects and until the late 1980s, only two basic partner-finding strategies pertaining to ‘butterflies’ and ‘moths’ were known. In short, male butterflies used their vision to detect conspecific females at some distance and to pursue them. Female butterflies, in turn, had no sex pheromone glands in their ovipositors and therefore did not release any long-range pheromone to attract males. In contrast, male moths used their olfaction system to detect females at some distance because the latter release long-range pheromonesFootnote 1 from their pheromone glands. Once together and in close courtship interactions, males (butterflies and moths), and in some cases also females, released close range pheromones or ‘scents’ that facilitated or prevented the last courtship steps leading to copulation. The butterflies, all diurnal except the moth-like hedylids, simply used vision to find mates in their sunlit environment with no need to produce long-range sex pheromones. The mostly nocturnal moths, in turn, kept the so-called ‘female calling plus male seduction’ strategy, which implied the production of long-range sex pheromones. Table 1 summarises the partner-finding strategies of nocturnal and diurnal lepidopteran groups.

Table 1. Generalized comparison of partner-finding strategies, pheromone uses and other related traits in nocturnal and diurnal lepidopteran groups.

1 Some species within a ‘nocturnal’ or ‘diurnal’ family have adapted to fly in the twilight or prefer to fly in shaded environments.

2 Some species within a typical ‘nocturnal’ family have adapted to fly in day time.

3 Except Z. nocturna and some related species.

4 Exceptionally some groups have ovipositor-like pheromone glands in other parts of the abdomen or thorax.

It must be mentioned, however, that three other partner-finding strategies have been described in night-flying moths (Hallberg & Poppy, Reference Hallberg, Poppy and Kristensen2003), although their occurrence is rare: (1) mutual calling in the noctuid Trichoplusia ni (Hübner) where both sexes ‘call’ (Landolt & Heath, Reference Landolt and Heath1989); (2) reverse calling in the Pyralid rice moth Corcyra cephalonica (Stainton), where the male emits a pheromone at a distance, and the female responds by releasing a pheromone at close-range and induces the male to copulate (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Cork, Lester, Nesbitt and Zagatti1987; Zagatti et al., Reference Zagatti, Kunesch, Ramiandrasoa, Malosse, Hall, Lester and Nesbitt1987); and (3) ‘lekking’, where several males gather together in a group (the lek) to which females are attracted by the male-produced pheromones, and mating takes place within the lek. Lekking behaviour has been reported in Hepialidae, Pyralidae and Arctiidae (Hallberg & Poppy, Reference Hallberg, Poppy and Kristensen2003). A good understanding of the above-mentioned strategies is important in natural resource management, not only for Lepidoptera of economic importance but also for endangered species and for those living in threatened habitats. The case of the Gondwanan family Castniidae, also called ‘butterfly-moths’ or ‘sun-moths’, is particularly exemplary in this respect. In the Neotropics, many of them live in threatened habitats since their boring larvae depend on tree-dwelling forest plants; however, a few species have adapted to boring into crop plants introduced by man, such as sugarcane, banana and African oil palm, subsequently becoming important pests of such crops (Sarto i Monteys & Aguilar, Reference Sarto i Monteys and Aguilar2005). One of them, Paysandisia archon (Burmeister) was introduced into Europe (Spain) in the mid-1990s to spread eastwards to Bulgaria, Greece and Cyprus and become a serious pest of many palm species (Sarto i Monteys & Aguilar, Reference Sarto i Monteys and Aguilar2005). In Australia, less than 50 castniid species occur, and all are included in the genus Synemon Doubleday (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Gentili, Horak, Kristensen, Nielsen and Kristensen1998). Synemon larvae feed underground on the roots and rhizomes of grasses and sedges, and suffer a drastic reduction in their populations because of the clearing or modification of vast areas of native grasslands, woodlands and heathlands across Australia, therefore requiring urgent protection measures (Douglas, Reference Douglas2004). In this respect, knowing in detail how a species communicates sexually may give resource managers significant clues to either control or protect any specific endangered population. This review deals with the sexual communication in day-flying Lepidoptera, either butterflies or moths with diurnal habits paying particular attention to castniids and to their recently suggested butterfly-like partner-finding strategy. We have also included Zygaenidae moths (genus Zygaena Fabricius) because they display a dual partner-finding strategy between the castniids/butterflies and the other day-flying moths.

The butterflies (Superfamily Papilionoidea) and their reproductive behaviour

Butterflies comprise 11.9% (ca.18,800 species) of all described Lepidoptera. They are currently grouped within the taxonomic superfamily Papilionoidea, with seven families, namely Papilionidae, Pieridae, Riodinidae, Lycaenidae, Nymphalidae, Hesperiidae (skippers) and Hedylidae (van Nieukerken et al., Reference van Nieukerken, Kaila, Kitching, Kristensen, Lees, Minet, Mitter, Mutanen, Regier, Simonsen, Wahlberg, Yen, Zahiri, Adamski, Baixeras, Bartsch, Bengtsson, Brown, Bucheli, Davis, De Prins, De Prins, Epstein, Gentili-Poole, Gielis, Hättenschwiler, Hausmann, Holloway, Kallies, Karsholt, Kawahara, Koster, Kozlov, Lafontaine, Lamas, Landry, Lee, Nuss, Park, Penz, Rota, Schintlmeister, Schmidt, Sohn, Solis, Tarmann, Warren, Weller, Yakovlev, Zolotuhin, Zwick and Zhang2011). Two recent molecular studies (Regier et al., Reference Regier, Zwick, Cummings, Kawahara, Cho, Weller, Roe, Baixeras, Brown, Parr, Davis, Epstein, Hallwachs, Hausmann, Janzen, Kitching, Solis, Yen, Bazinet and Mitter2009; Mutanen et al., Reference Mutanen, Wahlberg and Kaila2010) strongly supported this grouping, although formerly skippers and hedylids were placed in separate superfamilies and the other five families were grouped into only one superfamily. Skippers are more closely related to hedylids than to the other butterflies (Regier et al., Reference Regier, Zwick, Cummings, Kawahara, Cho, Weller, Roe, Baixeras, Brown, Parr, Davis, Epstein, Hallwachs, Hausmann, Janzen, Kitching, Solis, Yen, Bazinet and Mitter2009; Mutanen et al., Reference Mutanen, Wahlberg and Kaila2010), although hedylids are mainly nocturnal and the available data (Scoble, Reference Scoble1986; Scoble & Aiello, Reference Scoble and Aiello1990) suggest that their reproductive behaviour resembles that of moths. It has been suggested that the reproductive behaviour of skippers and other butterflies (but not hedylids) may have evolved independently as an adaptation to diurnal habits (Sarto i Monteys et al., Reference Sarto i Monteys, Acín, Rosell, Quero, Jiménez and Guerrero2012).

Butterflies had always been thought to be unique in their partner-finding, at first based on visual cues as mentioned above. After the pursuit flight, when the two sexes get together (i.e. in close-range interactions), males release short-range pheromones and there is mounting evidence that females may also do the same (Wiklund, Reference Wiklund, Boggs, Watt and Ehrlich2003). However, females lack conspicuous scent organs, such as the typical sex pheromone glands, which makes the study of their chemical signals for male recognition and mating particularly difficult (for reviews see Boppré (Reference Boppré, Vane-Wright and Ackery1984), Hallberg & Poppy (Reference Hallberg, Poppy and Kristensen2003)).

Male butterflies use basically two mating strategies, namely perching and patrolling (Scott, Reference Scott1974; Wiklund, Reference Wiklund, Boggs, Watt and Ehrlich2003). Perching males (fig. 1) sit and wait for flying females, which actively assume the role of searching for males. Perchers are territorial, typically faithful to their perching sites and readily willing to expel other males from their territories, largely by non-contact aerial interactions. The two ‘fighting’ males circle or hover near each other for a period of time before one of them flies away from the site. In contrast, patrolling males do not sit waiting for females, but actively search for them in places where they can be expected with a certain probability (Davies, Reference Davies1978; Wickman & Wiklund, Reference Wickman and Wiklund1983; Wiklund, Reference Wiklund, Boggs, Watt and Ehrlich2003; Kemp & Wiklund, Reference Kemp and Wiklund2004). Perching and patrolling may not be mutually exclusive and some species can perform both. Thus, in the speckled wood butterfly, Pararge aegeria (Linnaeus), males fight over sunspot territories on the forest ground; winners gain sole residency of a sunspot and behave as perchers, whereas losers patrol the forest in search for females (Bergman et al., Reference Bergman, Gotthard, Berger, Olofsson, Kemp and Wiklund2007). In other cases, a male butterfly which usually patrols might behave as a percher, e.g. on windy or overcast days. After female detection, perchers and patrollers pursue the female at close range, assessing her size, shape and wing pattern to be certain she is suitable for mating (Rutowski, Reference Rutowski, Boggs, Watt and Ehrlich2003; Warrant et al., Reference Warrant, Kelber, Kristensen and Kristensen2003; Wiklund, Reference Wiklund, Boggs, Watt and Ehrlich2003). At this close range male butterflies release pheromones that convey information to the females, inducing them to respond (mate or reject). Such male scents are produced and/or disseminated in special structures, the most common being alar androconia, i.e. specialised male scales located on the forewings, hindwings or both, and ‘hairpencils’, modified scales present on wings or the abdomen.

Fig. 1. Perching specimen of the large skipper butterfly Ochlodes sylvanus (Esper) (Hesperiidae). (Photograph by V. Sarto i Monteys).

Male sex pheromones (MSPs) in butterflies have long-been thought to be vital in courtship, mate-choice or acceptance by females (sexual selection), species isolation and/or recognition (Boppré, Reference Boppré, Vane-Wright and Ackery1984; Costanzo & Monteiro, Reference Costanzo and Monteiro2007). In this respect, it is noteworthy that in the nymphalid butterfly Bicyclus anynana (Butler) the MSP composition changes along the insect lifespan, a signal which may be used by the insect for male identity and male age (females prefer to mate with middle-aged rather than younger males) (Nieberding et al., Reference Nieberding, Fischer, Saastamoinen, Allen, Wallin, Hedenström and Brakefield2012).

Burnets and Forester moths (Family Zygaenidae) and their reproductive behaviour

The zygaenids comprise four subfamilies and about 1000 described species worldwide (Tarmann, Reference Tarmann2004; van Nieukerken et al., Reference van Nieukerken, Kaila, Kitching, Kristensen, Lees, Minet, Mitter, Mutanen, Regier, Simonsen, Wahlberg, Yen, Zahiri, Adamski, Baixeras, Bartsch, Bengtsson, Brown, Bucheli, Davis, De Prins, De Prins, Epstein, Gentili-Poole, Gielis, Hättenschwiler, Hausmann, Holloway, Kallies, Karsholt, Kawahara, Koster, Kozlov, Lafontaine, Lamas, Landry, Lee, Nuss, Park, Penz, Rota, Schintlmeister, Schmidt, Sohn, Solis, Tarmann, Warren, Weller, Yakovlev, Zolotuhin, Zwick and Zhang2011). With few exceptions, e.g. the nocturnal Zygaena nocturna Ebert and some related species, they include typically day-flying moths with a slow, fluttering flight. Their partner-finding strategy corresponds to the typical pattern for moths, with females calling males by releasing long-range sex pheromones (Subchev, Reference Subchev2014). Their sex glands are located at the tip of the abdomen (between segments 8 and 9, as usual in moths) (fig. 2a, b) or on the anterior parts of tergites 3–5 of the abdomen, as found widespread in the subfamily Procridinae (Hallberg & Subchev, Reference Hallberg and Subchev1997).

Fig. 2. Z. escalerai Poujade (Zygaenidae, Zygaeninae): (a) Calling female, (b) Closeup of ovipositor at calling, showing expanded intersegmental membrane between segments 8 and 9. (Photographs by A. Hofmann).

Visual cues are also important in the mating behaviour of zygaenids, although only in the short-range phase of the courtship. Thus, in the six-spot burnet, Zygaena filipendulae (Linnaeus), the long-range attraction of males is mediated by female-released pheromones, but when the flying male is within ca. 50 cm range, then visual cues determine the rest of the courtship (Zagatti & Renou, Reference Zagatti and Renou1984). Also, in the vine bud moth Theresimima ampelophaga (Bayle-Barelle) (Procridinae) males attracted to a synthetic sex pheromone dispenser displayed more copulation attempts when a female model (visual stimulus) was attached to the dispenser (chemical stimulus) (Toshova et al., Reference Toshova, Subchev and Tóth2007). It is uncertain whether optical cues play a significant role in the rare nocturnal zygaenids, such as Z. nocturna, since males were found to reach calling females in the dark, mostly between 21 and 23 h (A. Hofmann, personal communication, 2015).

More surprising is the dual partner-finding strategy shown by the five-spot burnet, Zygaena trifolii (Esper) (Naumann, Reference Naumann1988; Prinz & Naumann, Reference Prinz and Naumann1988). The females have typical sex pheromone glands that release pheromone to attract males in late afternoon. In the morning, however, they rest atop grasses close to where their cocoons were spun, do not release pheromones and can be found by males using optical cues exclusively (female wing pattern, spot colouration and specimen size). In late afternoon, the females move down into the vegetation, where they would not be easily spotted by flying males, and release the pheromone.

The likely evolutionary advantages of the dual partner-finding strategy have been reported (Naumann et al., Reference Naumann, Tarmann and Tremewan1999). Although it is likely that the dual strategy may be present in other species of the subgenus Zygaena, it is not well established how widespread this strategy is among other European Zygaeninae. In this context, Hofmann & Kia-Hofmann (Reference Hofmann and Kia-Hofmann2010) noted that the optical cues used by males of Z. trifolii during the morning and occasionally leading to ‘morning copulae’, cannot be considered as a general strategy and may vary from species to species depending on ecological circumstances (e.g. altitude, semi-desert and woodland). In this respect, behavioural studies carried out on Zygaena niphona Butler (Koshio, Reference Koshio, Efetov, Tremewan and Tarmann2003) and Zygaena fausta (Linnaeus) (Friedrich & Friedrich-Polo, Reference Friedrich and Friedrich-Polo2005) revealed that these species did not show the dual partner-finding strategy but only the widespread combined chemical and optical afternoon strategy, as described above for Z. filipendulae.

Notwithstanding, the discovery of the above-mentioned dual strategy in Z. trifolii is very significant from an evolutionary point of view because it was the first documented case in which a day-flying moth was not using long-range pheromones for partner-finding, at least in the morning.

The castniids or ‘butterfly-moths’ (Family Castniidae) and their reproductive behaviour

The Castniidae are day-flying, brightly coloured and median/large-sized moths, occurring in the Neotropics, SE Asia and Australia, with only about 110 species described (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Gentili, Horak, Kristensen, Nielsen and Kristensen1998). They are currently grouped within the superfamily Cossoidea, with seven families, namely Brachodidae (little bear moths), Cossidae (cossid millers or carpenter millers), Dudgeoneidae, Metarbelidae, Ratardidae (Oriental parnassian moths), Sesiidae (clearwing moths) and Castniidae (van Nieukerken et al., Reference van Nieukerken, Kaila, Kitching, Kristensen, Lees, Minet, Mitter, Mutanen, Regier, Simonsen, Wahlberg, Yen, Zahiri, Adamski, Baixeras, Bartsch, Bengtsson, Brown, Bucheli, Davis, De Prins, De Prins, Epstein, Gentili-Poole, Gielis, Hättenschwiler, Hausmann, Holloway, Kallies, Karsholt, Kawahara, Koster, Kozlov, Lafontaine, Lamas, Landry, Lee, Nuss, Park, Penz, Rota, Schintlmeister, Schmidt, Sohn, Solis, Tarmann, Warren, Weller, Yakovlev, Zolotuhin, Zwick and Zhang2011). Initially, Minet (Reference Minet1991) had placed the Castniidae in the superfamily Sesioidea together with Sesiidae and Brachodidae, but recent molecular studies grouped the Sesioidea with some Cossoidea in a large, near-monophyletic (but internally unresolved) assemblage that included Cossoidea, Sesioidea and Zygaenoidea (Regier et al., Reference Regier, Zwick, Cummings, Kawahara, Cho, Weller, Roe, Baixeras, Brown, Parr, Davis, Epstein, Hallwachs, Hausmann, Janzen, Kitching, Solis, Yen, Bazinet and Mitter2009; Mutanen et al., Reference Mutanen, Wahlberg and Kaila2010). Many species in this heterogeneous group are diurnal.

Castniids are interesting Lepidoptera in the following respects:

-

(1) The Neotropical species of castniids remarkably mimic many butterflies living in the same area in form, colours and habits, and form a truly Batesian mimicry association (Miller, Reference Miller1986). The levels of mimicry between butterflies and castniids, two groups of phylogenetically distant lepidopterans, are unparalleled in the order Lepidoptera and this has granted to castniids the term ‘butterfly-moths’.

-

(2) Castniid males are territorial and display perching behaviour as butterfly males (Sarto i Monteys et al., Reference Sarto i Monteys, Acín, Rosell, Quero, Jiménez and Guerrero2012) and references therein), which is also an unparalleled trait in moths.

-

(3) Most importantly, and in contrast to other known moths including day-flying moths, castniid females appear to have lost their abdominal pheromone glands, so that they do not release long-range pheromones to attract conspecific males. This evolutionary breakthrough was first hypothesised by Sarto i Monteys & Aguilar (Reference Sarto i Monteys and Aguilar2005), based on numerous field observations of the behaviour of P. archon, a large castniid moth (fig. 3) which had been introduced into Europe from Argentina, as cited above, becoming a pest of palm trees (Sarto i Monteys, Reference Sarto i Monteys2002). Experimental evidence brought forward to confirm the hypothesis that P. archon females do not release long-range pheromones to attract conspecific males was provided by Sarto i Monteys et al. (Reference Sarto i Monteys, Acín, Rosell, Quero, Jiménez and Guerrero2012) and Riolo et al. (Reference Riolo, Verdolini, Anfora, Minuz, Ruschioni, Carlin and Isidoro2014), although not without debate (Delle-Vedove et al., Reference Delle-Vedove, Frérot, Hossaert-McKey and Beaudoin-Ollivier2014) (see below). The fact that castniids mostly rely on visual cues for partner-finding, as most butterflies do (see above), was already noticed in the early 1900s by the German naturalist Adalbert Seitz (Seitz & Strand, Reference Seitz, Strand and Seitz1913).

Fig. 3. Perching male of P. archon (Castniidae). (Photograph by V. Sarto i Monteys).

Territoriality and perching/patrolling behaviour in castniids

P. archon males usually perch on palm leaves or cut rachises around the trunk close to the crown (fig. 3) (Sarto i Monteys & Aguilar, Reference Sarto i Monteys and Aguilar2005). When a perching male watches another male approaching his territorial spot, he immediately takes off towards the intruder and a pursuit begins. The pursuit flight is very powerful and rapid, and the flight path is generally straight although right/left shifts may also occur (Sarto i Monteys & Aguilar, Reference Sarto i Monteys and Aguilar2005). If the flying pair cross the territory of another male, this third one would immediately join the pursuit so that the flying group would now be constituted by three individuals and so on. These pursuit flights are not long-lasting and males soon fly back to their perching spots.

Most males behave like perchers, i.e. they are faithful to a territory or spot they ‘defend’. These spots are located within palm-infested plots, where females would be flying around after emergence and detected by perching males. In Catalonia, NE of Spain, the areas of these plots are not large (usually <3000 m2), and it is unclear how the territorial spots are shared by competing males, especially when infestation is high. It is likely that males with no ‘territory’ move away in search of new plots to colonise and females to mate. In this case, they would behave as patrollers, as supported by our occasional observations of lone-flying males. As in other castniids, the territoriality of P. archon is poorly understood, and thus several questions remain unanswered, such as: who wins the territorial spot? How large are the territorial spots? Or what drives the likely migration of males and females to other palm plots? Based in our observations, the mating behaviour of P. archon cannot be properly performed in nature unless large areas are available to the moths, and so studies carried out only in small insectaries or cages are not suitable for fully understanding the behaviour of these insects and may lead to wrong conclusions.

Do female castniids have pheromone glands in their ovipositors?

Several morphological, chemical and ethological facts combined appear to demonstrate that P. archon females have apparently lost their pheromone glands. These facts are the following:

-

(1) The territorial male behaviour described above does not support that female castniids use long-range pheromones for partner-finding, with vision playing a determinant role in this task.

-

(2) Hexane extracts of P. archon female ovipositors and other female body parts have yielded no compounds with putative pheromone activity (Acín, Reference Acín2009; Sarto i Monteys et al., Reference Sarto i Monteys, Acín, Rosell, Quero, Jiménez and Guerrero2012). Also, analysis of ovipositor extracts of 1- and 24-h virgin females of P. archon (N = 10) in hexane resulted in the identification of 24 different compounds but none of them elicited any significant gas chromatography-electroantennographic detector (GC-EAD) responses on male antennae (Riolo et al., Reference Riolo, Verdolini, Anfora, Minuz, Ruschioni, Carlin and Isidoro2014). The GC-EAD system allows determination of the electrophysiological activity of every compound eluting from the capillary column when the outlet of the column is split in a specific ratio (usually 1:1) between the GC detector and the male antenna.

-

(3) In most Lepidoptera, when female moths adopt the ‘calling’ position, the glandular area containing the sex pheromone gland is exposed and the pheromone is released (Percy-Cunningham & MacDonald, Reference Percy-Cunningham, MacDonald, Prestwich and Blomquist1987; Hallberg & Poppy, Reference Hallberg, Poppy and Kristensen2003). A well-defined periodicity for calling is widespread in nocturnal and diurnal moths that use long-range chemical communication (e.g. (Haynes et al., Reference Haynes, Gaston, Mistrot Pope and Baker1983) and references therein). For instance, females of the nocturnal tobacco budworm Heliothis virescens (Fabricius) call during the period 23:30–02:30 h (Sparks et al., Reference Sparks, Raulston, Lingren, Carpenter, Klun and Mullinix1979), whereas those of the artichoke plume moth Platyptilia carduidactyla (Riley) call mainly between 2 and 6.5 h after the onset of the scotophase (Haynes et al., Reference Haynes, Gaston, Mistrot Pope and Baker1983). In the diurnal gypsy moth Lymantria dispar (Linnaeus), females call continuously from 10:00 to 22:00 h but some females may continue calling at night during the scotophase and early photophase (Charlton & Cardé, Reference Charlton and Cardé1982). In diurnal burnet moths of the genus Zygaena, most females may call for 5–10 h per day (A. Hofmann, personal communication, 2015). Therefore, in diurnal moths the periodicity of pheromone release and calling appear to be not as discrete as in the nocturnal moths, but in all cases, females expose their glandular area during several hours to release the pheromone. Nothing similar has been observed in P. archon females. We have frequently noticed that females quickly extrude/retract their ovipositors for some seconds, but never adopt a typical ‘calling’ position that implies keeping ovipositors extruded for a long period of time. Riolo et al. (Reference Riolo, Verdolini, Anfora, Minuz, Ruschioni, Carlin and Isidoro2014) have also reported that females perform the extrude/retract action very often throughout their lives, but it appears not to be related to calling behaviour. These authors concluded that ovipositor extrusion might be involved in the female physiological state (i.e. egg load) or in thermoregulation activity, as observed in the hawk moth Eumorpha achemon (Drury).

-

(4) The antennae of castniids and butterflies are strikingly similar, with no apparent sexual dimorphism. The antennae are the ‘noses’ of moths and butterflies and their morphology and sensilla are suited to their needs (Hansson, Reference Hansson1995; Hallberg & Poppy, Reference Hallberg, Poppy and Kristensen2003). Moth antennae are generally sexually dimorphic, and those of males contain a certain population of sensilla housing olfactory receptor neurons sensitive to the pheromone components. Butterflies, in turn, possess thin and clubbed antennae and display no sexual dimorphism. They use sex pheromones only for close-range communication and therefore lack the highly sensitive detection system found in male moths. In a scanning electron microscopy (SEM) study of male and female antennal sensilla of several day-flying Lepidoptera, namely sesiids, butterflies (pierids and skippers) and castniids (P. archon), Sarto i Monteys et al. (Reference Sarto i Monteys, Acín, Rosell, Quero, Jiménez and Guerrero2012) concluded that P. archon male antennae were unsuited to detect long-range pheromones.

-

(5) The abdominal tip (segments 8 and 9–10) of female Lepidoptera forms a telescope-type oviscapt, commonly called ‘ovipositor’. In most Cossoidea, the intersegmental cuticle connecting segments 8 and 9 is long when the ovipositor is fully extended. Below that cuticle are located the glandular epithelial cells that produce pheromones. In sesiids, which are very closely related to castniids, such cuticle shows many buds, each topped with one thin and curved ‘hair’ (fig. 4) that is supposed to help release the pheromone (Tatjanskaitë, Reference Tatjanskaitë1995). However, SEM studies on P. archon ovipositors showed that the 8–9 intersegmental cuticle was devoid of such structures, and instead multiple longitudinal smooth folds could be seen, simply allowing for ovipositor expansion, as if there were no pheromone glands underneath (figs 5 and 6) (Sarto i Monteys et al., Reference Sarto i Monteys, Acín, Rosell, Quero, Jiménez and Guerrero2012). More recent histological studies confirmed this assumption as there was no evidence of pheromone gland tissues below the intersegmental cuticle of the P. archon ovipositor (Riolo et al., Reference Riolo, Verdolini, Anfora, Minuz, Ruschioni, Carlin and Isidoro2014).

Fig. 4. Clearwing moth Synanthedon sp. ovipositor (Sesiidae): (a) 20 µm cross-section (seen with light microscope) of intersegmental membrane between abdominal segments 8 and 9 of the ovipositor (top is dorsal). In, integument; Pr, proctodeum; Mu, muscles; Ap, posterior apodema or posterior ‘apophysis’; Tr, tracheae. Scale bar: 100 µm. Many cuticular buds cover the whole intersegmental cuticle, each topped with one thin and curved spinelike process, supposed to help release the pheromone. (b) closeup showing the cuticular buds (arrowheads point to some of them) of the integument. Scale bar: 30 µm. (Photographs by M.C. Santa-Cruz).

Fig. 5. P. archon ovipositor. (a) ventral view of partly retracted ovipositor (treated with potassium hydroxide 10%). (b) side view of fully everted ovipositor (segment 9 + 10, intersegment 8–9, segment 8) plus intersegment 7–8 and part of segment 7 (in ethanol 70%). Left side is dorsal; right side is ventral. Black arrows show from top to bottom the 9 (+10), 8 and 7 abdominal segments; blue arrows show the intersegmental membranes between segments 8–9 (top) and 7–8 (bottom). Left posterior and anterior ‘apophysis’ or apodemas are also indicated. Scale bars for a, b are 1 and 2 mm, respectively. (Photographs (a) by M.C. Santa-Cruz; (b) by V. Sarto i Monteys).

Fig. 6. SEM images of P. archon ovipositor. (a) intersegmental membrane between segments 8 and 9 showing a smooth surface (x 35). (b) closeup, 700× showing multiple longitudinal smooth folds, allowing for extra ovipositor expansion. (c) closeup, 5000×. Unlike sesiids, the 8–9 intersegmental membrane of P. archon ovipositor is devoid of any cuticular buds. Scale bars for a, b, c are 500, 25, and 4 µm, respectively. (Photographs by V. Sarto i Monteys).

The latter five facts combined appear to clearly indicate that, as in female butterflies, P. archon females do not possess any abdominal gland to release a volatile pheromone to attract conspecific males, and this may likely be widespread in Castniidae. However, against this assumption, Delle-Vedove et al. (Reference Delle-Vedove, Frérot, Hossaert-McKey and Beaudoin-Ollivier2014) claimed that P. archon females ‘call’ males using a pheromone identified as (E,Z)-2,13-octadecadien-1-yl acetate from ovipositor extracts of sexually mature females but no further details were given. They also concluded that the insect displays a ‘moth-butterfly hybrid’ strategy relying on both chemical and visual clues. The chemical thought to be the female sex pheromone of P. archon had been identified in females of a number of Sesiidae, especially of the genus Synanthedon Hübner, and in females of the leopard moth Zeuzera pyrina (Linnaeus) (Cossidae) (El-Sayed, Reference El-Sayed2014). In this respect, it should be noticed that this pheromone was used in one-day field tests carried out at two sites in Catalonia to check a possible attractant effect on P. archon males. The tests took place in sunny days of mid-July and observations lasted continuously from 12 to 15 h, when P. archon males are particularly active. Three filter papers and three paper dummies depicting an adult of P. archon were impregnated with 1 µg of Z. pyrina pheromone dissolved in hexane. Such gadgets were set spaced 8 m apart on palm trunks (Trachycarpus fortunei (Hook.) H. Wendl. and Chamaerops humilis Linnaeus) within commercial gardens heavily infested by P. archon. At both sites not a single P. archon male approached to either lure suggesting that this pheromone does not attract males of this castniid (Vassiliou & Sarto i Monteys, Reference Vassiliou and Sarto i Monteys2014).

Mating behaviour of P. archon at close range

The courtship behavioural sequence of P. archon was first described in detail by Sarto i Monteys & Aguilar (Reference Sarto i Monteys and Aguilar2005) and Sarto i Monteys et al. (Reference Sarto i Monteys, Acín, Rosell, Quero, Jiménez and Guerrero2012) as the following six consecutive steps: (1) Localisation/pursuit: A territorial perching (or maybe patrolling) male locates a flying female that has entered his territory and pursues her. The pair fly together along the palm rows close to each other (about 10–15 cm) and at heights near the palm crowns. (2) Alighting: Then, the pair alight, led by the female, facing up on upright surfaces (a palm leaf or crown, the sides of a mesh tent, etc.). The female may walk shortly until reaching a spot where she can rest comfortably, folding her wings in the common noctuoid position, and if the male is accepted, she will remain still for the rest of the courtship. (3) Orientation: The male, which alighted a few cm below the female and has been closely following her movements, moves up and approaches to her with his wings folded. There is no male flickering. (4) Thrusting: While approaching the female, the male usually touches the edges of her wings with his head/antennae, sometimes inserting the antennae briefly under her wings. Also, his antennae and/or legs may also make contact with the side of the female. Both sexes keep their wings fully folded. (5) Attempting: The male curls his abdomen and opens up his clasping genital valvae in order to contact and grasp the female copulatory orifice to accomplish the copula. (6) Copulation: While in copula, both sexes stay motionless, facing up side by side, and with the male in a lower position than the female.

Recently, the courtship behaviour of P. archon has received further attention (Delle-Vedove et al., Reference Delle-Vedove, Beaudoin-Ollivier, Hossaert-McKey and Frérot2012, Reference Delle-Vedove, Frérot, Hossaert-McKey and Beaudoin-Ollivier2014; Riolo et al., Reference Riolo, Verdolini, Anfora, Minuz, Ruschioni, Carlin and Isidoro2014) with both research groups providing a deep quantitative analysis of the behaviours involved (up to 14 defined by the former authors and 20 by the latter). Both groups also provided kinetic diagrams of courtship behaviour indicating, for each behavioural step, the frequency of transitions to other courtship steps. They basically confirmed the main six behavioural steps described above, including in the sequence analysis all types of behaviours displayed by both sexes during courtship. One of such behaviours was the ovipositor extrusion. According to Delle-Vedove et al. (Reference Delle-Vedove, Frérot, Hossaert-McKey and Beaudoin-Ollivier2014) the extrusion (1–10 times during periods of 13–48 s each before displaying another behaviour type) was synonymous to ‘calling’, i.e. females emitting a sex pheromone to attract males. In contrast, according to Riolo et al. (Reference Riolo, Verdolini, Anfora, Minuz, Ruschioni, Carlin and Isidoro2014), extrusion of the ovipositor was not related to calling but possibly to the female physiological state or to thermoregulation activity, as cited above.

Other behaviours during P. archon courtship which deserve special mention are antenna cleaning (in both sexes) and male ‘scratching’. Females clean their antennae about three times more often than males, regardless of courtship outcome (Riolo et al., Reference Riolo, Verdolini, Anfora, Minuz, Ruschioni, Carlin and Isidoro2014), and because females have a higher olfactory sensory surface area in their antennae than males (Sarto i Monteys et al., Reference Sarto i Monteys, Acín, Rosell, Quero, Jiménez and Guerrero2012), this suggests that the perception of volatiles is highly important to P. archon females – probably more than it is for males whose antennae are unsuited for detecting long-range pheromones (see above).

Male ‘scratching’ is an interesting behaviour introduced by Frérot et al. (Reference Frérot, Delle-Vedove, Beaudoin-Ollivier, Zagatti, Ducrot, Grison, Hossaert and Petit2013) and Delle-Vedove et al. (Reference Delle-Vedove, Frérot, Hossaert-McKey and Beaudoin-Ollivier2014). When performed, the male walks and scratches/rubs its midlegs rapidly on the substrate, supposedly helping the release of a male pheromone produced and/or held in the midlegs (see below) and inducing the female to take-off and initiate a hovering flight. The authors, however, do not provide any evidence that such ‘scratching’ implies releasing pheromone from the male midlegs nor its unambiguous association to some kind of response by the female.

Castniids androconia and likely role of P. archon male putative pheromones

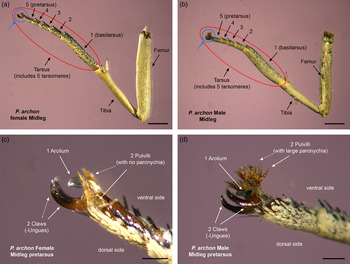

The structures presumed to be involved in the reproductive behaviour of castniid males have been poorly studied, although four types have been so far identified in the Neotropical species of the subfamily Castniinae: (1) a complex and very large abdominal (sternal) androconial organ with a brush in the hindlegs, formed by long, soft, pale scaling on the inner surface of femur, tibia and basitarsus, which supposedly helps distribute the gland secretion over the sternites in the abdomen; (2) large paronychia (i.e. bristle-like structures) on the pulvilli of midlegs pretarsi; (3) notably enlarged midlegs basitarsi, generally (but not exclusively) in combination with large midlegs pretarsal paronychia (see fig. 7a–d); (4) alar androconial organs located either on the underside of the forewings or the upper side of the hindwings (Jordan, Reference Jordan1923; Le Cerf, Reference Le Cerf1936). Whereas structures 3 and 4 seem to be common to most castniids, those individuals bearing structure 1 lack structure 2, and vice versa (Jordan, Reference Jordan1923); P. archon for instance holds structures 2, 3 and 4.

Fig. 7. Midleg of P. archon female (a) and male (b). Side view of full midleg (excluding coxa and trochanter), tibia and tarsus are seen lateroventrally. The 1st tarsomere (basitarsus) is not enlarged and appears smaller than the tibia in females (a), while in males the 1st tarsomere is notably enlarged (b). Closeup side view of pretarsal segment showing the two pulvilli with no paronychia in females (c) and forming large paronychia in males (d). Scale bars for a, b are 2 mm and for c, d 0.4 mm. (Photographs by V. Sarto i Monteys).

Very few reports have been found in the literature about the possible presence of sex pheromones in the Castniidae family and only concern those of females (Rebouças et al., Reference Rebouças, Caraciolo, Sant'Ana, Pickett, Wadhams and Pow1999). It was not until 2012 that three putative male pheromones were reported for the first time from P. archon male wings (Sarto i Monteys et al., Reference Sarto i Monteys, Acín, Rosell, Quero, Jiménez and Guerrero2012). The compounds were identified as (Z,E)-3,7,11-trimethyl-2,6,10-dodecatrienal ((Z,E)-farnesal), the corresponding E,E isomer ((E,E)-farnesal) and (E,Z)-2,13-octadecadienol, which elicited significant GC-EAD responses on female antennae. Farnesals were found in the forewings and hindwings of males only (fig. 8), although the relative amount detected in both types of wings was highly variable. The biological significance of farnesals in the male wings of P. archon is unknown, but it is noteworthy that both isomers of the chemical were identified in male glands located in the forewings of the rice moth C. cephalonica and elicited walking attractancy on females (Zagatti et al., Reference Zagatti, Kunesch, Ramiandrasoa, Malosse, Hall, Lester and Nesbitt1987). We could hypothesise that these chemicals may be used by P. archon females for sexual selection, as occurs in the nymphalid butterfly B. anynana whose females use n-hexadecanal, one specific component of the MSP, for that purpose (Nieberding et al., Reference Nieberding, Fischer, Saastamoinen, Allen, Wallin, Hedenström and Brakefield2012).

Fig. 8. GC–MS analysis (chromatogram a, b) of an extract of forewings (a) and hindwings (b) of P. archon males showing the presence of Z,E-farnesal (retention time 13.95 min) and E,E-farnesal (14.26 min) and the corresponding mass spectra (c and d, respectively). Peak at retention time 12.66 min of the chromatogram corresponds to the internal standard (IS) (Z)-9-tetradecenol.

In female castniids, sexual selection may also be likely influenced by their monandrous condition. Thus, it is known that most P. archon females behave monandrously with only a few of them (6%) mating twice, always before laying their first eggs (Delle-Vedove et al., Reference Delle-Vedove, Beaudoin-Ollivier, Hossaert-McKey and Frérot2012). This is probably due to their low fecundity: P. archon and other castniid females only lay about 110–130 eggs in their lifetime (Sarto i Monteys & Aguilar, Reference Sarto i Monteys and Aguilar2005). Therefore, the monandrous female must choose which type of males can help her reproduce successfully, and she will likely prefer virgin to non-virgin males, since the former are likely to provide bigger spermatophores with higher amounts of sperm, proteins and lipids to be used in egg production (Lauwers & Van Dyck, Reference Lauwers and Van Dyck2006). In the speckled wood butterfly, P. aegeria, also a territorial species, copulations with non-virgin males lasted on average five times longer than with virgin males, resulting in a three times smaller spermatophore (Lauwers & Van Dyck, Reference Lauwers and Van Dyck2006). The number of eggs laid and the female lifespan were not affected by the mating status, but there was a significant effect on the number of living caterpillars as copulations with virgin males resulted in higher larval offspring.

It is known that males from several lepidopteran families, either moths (e.g. Arctiinae-Noctuidae) or butterflies (Danainae and Ithomiinae-Nymphalidae), accumulate substances from the host plant at the larval stage as a defence mechanism against predators (Schulz et al., Reference Schulz, Beccaloni, Brown, Boppré, Freitas, Ockenfels and Trigo2004). Many of these chemicals can be subsequently used as pheromone precursors (Eisner & Meinwald, Reference Eisner, Meinwald, Preswitch and Blomquist1987; Trigo et al., Reference Trigo, Barata and Brown1994). Farnesals are present in plants of the families Araceae, Orchidaceae, Cactaceae, Rubiaceae and others, but have not yet been found as such in palm trees (Arecaceae). The latter, which are the only food plants of P. archon larvae, contain, however, relatively large amounts of (Z) and (E)-β-farnesenes (see f.i. Knudsen, Reference Knudsen2002), and these compounds could be biosynthetic precursors of the farnesals found in P. archon through the corresponding intermediate farnesols.

The presence of (E,Z)-2,13-octadecadienol in P. archon was also noticed by Frérot et al. (Reference Frérot, Delle-Vedove, Beaudoin-Ollivier, Zagatti, Ducrot, Grison, Hossaert and Petit2013) in surprisingly huge amounts (μg) from male midlegs. This compound was identified by its NMR spectrum and GC–MS, and the authors suggested that the midlegs basitarsi were probably the sites of emission. This dienol is a component of the female sex pheromone or attractant of some Lepidoptera, namely some species of the family Tineidae, such as the common clothes moth, Tineola bisselliella (Hummel), some species of Prochoreutis Diakonoff & Heppner (Choreutidae), and several clearwing moths (Sesiidae), this latter family closely related to that of castniids (El-Sayed, Reference El-Sayed2014). The role of the dienol in the chemical communication of P. archon is likely different to that of the farnesals. Because the alcohol triggers significant responses in male and female antennae (Sarto i Monteys et al., Reference Sarto i Monteys, Acín, Rosell, Quero, Jiménez and Guerrero2012), it might act as a ‘territorial’ pheromone, i.e. males could use it to let other males know about its presence, either around where they are perching and/or when they alight close to the female in the close-range phase of the courtship.

Females, in turn, may perceive the dienol on flight during the pursuit phase of the courtship or while approaching a male territory. Since male and female P. archon antennae are not suited to detect long-range pheromones, as cited above, the latter option would apply only at rather short distances.

In summary, we have reviewed the partner-finding strategies of three day-flying lepidopteran groups, namely butterflies (superfamily Papilionoidea) and the moth families Zygaenidae and Castniidae, and compared their mating behaviour with that of other typical diurnal and nocturnal moth families. Day-flying moths have been subject to analogous evolutionary pressures than those of butterflies, and consequently, at least in some of them, females behave as if they had lost their pheromone glands, not releasing long-range pheromones to attract conspecific males. In fact, as in butterflies, female castniids appear to have lost their pheromone glands, an attribute with no parallel in the world of moths, and this certainly represents an evolutionary breakthrough to what has been known about sexual communication in Lepidoptera. However, as pointed out, we are still far from fully understand the chemical communication of day-flyers, particularly of castniids, and more work should be devoted to unveiling the function of the diverse structures allegedly involved in their reproductive behaviour and the specific role of their sex pheromones. Knowledge of the chemical communication of day-flying Lepidoptera is also important in natural resource management, both for control of new invasive species, like P. archon, or to protect specific endangered populations.

Acknowledgements

We thank CSIC for a postdoctoral contract to C.Q. We thank J.-B. Peltier for help with literature and P. archon cocoons, L. Aguilar for providing information on P. archon's infested plots in Catalonia. We also acknowledge A. Hofmann and G. Tarmann for helpful literature and/or comments provided on Zygaenidae reproductive behaviour. This work was partially supported by MINECO (grant no. AGL2012-39869-C02-01) with assistance from the European Regional Development Fund.