1. Against extensionality: A multidisciplinary case for the rationality of (some, but not all) framing effects

Psychologists and behavioral economists have come up with an almost uncountable series of experiments in which people are induced to rate or value the same thing differently depending on how it is framed. You might think: What could be more irrational? And you'd be in good company. Being susceptible to framing effects is a standard example of irrationality in textbooks, and there is a small industry of investment books explaining how framing effects can severely damage your financial health.

But this is a situation where easy cases make bad law. We need fundamentally to rethink the almost unquestioned assumption that frame-based reasoning is irrational. Outside the laboratory (and perhaps sometimes in it) there are many situations where it is perfectly rational to be influenced by how things are framed. And many situations, in fact, where being able to frame something in multiple ways is a powerful tool for understanding and making decisions.

Frames and framing factor into decision-making by making one dimension/attribute/value of a decision problem particularly salient. This can take many forms. In the simplest case, frames prime responses, as in many of the classic framing experiments (e.g., the Asian disease paradigm, where the gain frame primes risk-aversion and the loss frame primes risk-seeking). But in more complicated situations frames can function reflectively, by making salient particular reason-giving aspects of a thing, outcome, or action. For Shakespeare's Macbeth, for example, his feudal commitments are salient in one frame, while in another they are downplayed in favor of his personal ambition.

This target paper explains how the role of frames in reasoning can give rise to rational framing effects, which have the following structure: An agent or decision-makers prefer(s) A to B and B to C, even while knowing full well that A and C are different ways of framing the same action or outcome. Such patterns of quasi-cyclical preferences can be correct and appropriate from the normative perspective of how one ought to reason.

The case for rational framing effects has several strands. After reviewing the state of play in section 2, in section 3 I emphasize the role of emotions in decision-making, as well as how complex decision problems are best understood as defined over framed outcomes (as opposed to the neutral, extensional scenarios envisaged by decision theorists). I offer two dramatic examples of quasi-cyclical preferences – Aeschylus's Agamemnon and Shakespeare's Macbeth.

The second half of the paper explores three ways in which rational framing effects can function in practical decision-making. Section 4 shows how consciously framing and reframing long-term goals and short-term temptations can be important tools for self-control. In section 5 we see how, for the prototypical social interactions modeled by game theory, allowing for rational framing effects solves longstanding problems, such as the equilibrium selection problem and the challenge of explaining the appeal of non-equilibrium solutions (such as Cooperation in the Prisoner's Dilemma). Finally, section 6 shows how processes for resolving interpersonal conflicts and breaking discursive deadlock, because they involve internalizing multiple and incompatible ways of framing actions and outcomes, in effect creates rational framing effects.

2. The extensionality requirement: A cornerstone of rationality?

2.1 The extensionality principle

Decision theorists disagree about a lot of things. Almost everything, in fact. But one basic principle receives almost unanimous acceptance. This is the extensionality principle (a.k.a. the invariance principle), poetically phrased by Shakespeare in Romeo and Juliet: “What's in a name? That which we call a rose/By any other name would smell as sweet.” How we name things should not affect how we value them. More generally, preferences, values, and decisions should be unaffected by how actions and outcomes are framed.

The extensionality principle: Preferences, values, and decisions should be unaffected by how outcomes are framed.

It is an immediate consequence of the extensionality principle that framing effects are always irrational.

2.2 Extensionality and framing effects in psychology and behavioral economics/finance

2.2.1 Psychology

The ever-expanding literature on framing effects in psychology goes back to the groundbreaking studies of Tversky and Kahneman (Reference Tversky and Kahneman1981), which first presented the Asian disease paradigm. The headline finding from this paradigm was that different frames can prime different attitudes to risk. A positive frame (e.g., talking about survival rates) primes risk aversion, while a negative frame (e.g., talking about mortality rates) primes risk-seeking behavior. Subjects prefer a certain outcome to a risky one in the positive/survival frame, but preferences reverse in the negative/mortality frame.Footnote 1

Research on framing effects in psychology has identified a wide range of valence-consistent framing effects, in which risk is not a factor and so the effect is driven purely by valence. These include: the fat content of ground meat (Levin & Gaeth, Reference Levin and Gaeth1988); condom use (Linville, Fischer, & Fischoff, Reference Linville, Fischer, Fischoff, Pryor and Reeder1993); evaluating basketball players (Levin, Schneider, & Gaeth, Reference Levin, Schneider and Gaeth1998); contract negotiation (Neale & Bazerman, Reference Neale and Bazerman1985); and social dilemmas (Brewer & Kramer, Reference Brewer and Kramer1986). In all these cases subjects consistently respond to the same thing differently as a function of how it is framed (preferring meat labeled as 25% fat to meat labeled as 75% lean, and even finding that it tastes better).Footnote 2

2.2.2 Behavioral economics and behavioral finance

Framing effects have been extensively investigated in behavioral finance (for an overview see Bermúdez, Reference Bermúdez2020a, Ch. 3). Multiple studies have confirmed that investors tend to be risk-averse for gains and risk-seeking for losses. A particular focus of research is how this bias, if such it is, plays out across temporally extended investment behavior through varieties of mental accounting, as in Johnson and Thaler's theory of hedonic editing, which explores how people keep track of losses and gains across multiple gambles/investment decisions (Thaler, Reference Thaler1999; Thaler & Johnson, Reference Thaler and Johnson1991).

The disposition effect is the tendency to hold losing investments and sell those doing well (Shefrin & Statman, Reference Shefrin and Statman1985) and implicates multiple types of framing – focusing on losses/gains rather than absolute levels of wealth, for example, and also framing losses narrowly rather than across an entire portfolio (Barberis & Huang, Reference Barberis, Huang and Mehra2006; Barberis & Xiong, Reference Barberis and Xiong2009). The theory of myopic loss aversion that has been proposed to explain the equity risk premium (the fact that equities are priced much higher relative to bonds than would be predicated by plausible measures of risk aversion – Mehra, Reference Mehra2008; Mehra & Prescott, Reference Mehra and Prescott1985) is a framing explanation. Myopic loss aversion is the tendency to evaluate losses and gains in terms of particular (and relatively short) timeframes, for example, 12 months. This is a framing effect, because the same absolute levels might well be a gain rather than a loss relative to a longer timescale.

2.3 The consensus view

Tversky and Kahneman themselves drew a stark conclusion from their experiments on framing effects and breaches of the extensionality principle:

Because framing effects and the associated failures of invariance are ubiquitous, no adequate descriptive theory can ignore these phenomena. On the other hand, because invariance (or extensionality) is normatively indispensable, no adequate prescriptive theory should permit its violation. Consequently, the dream of constructing a theory that is acceptable both descriptively and normatively appears unrealizable (Tversky & Kahneman, Reference Tversky and Kahneman1986, p. S272)

Despite some challenges and objections (see notes 2 and 3), it is fair to say that those words, written in 1986, still represent a consensus among psychologists of reasoning, and in the cognitive sciences more broadly.

In economics and finance, the irrationality of framing effects is rarely questioned. Experimental paradigms typically result in subjects choosing options in which they receive less money (or lose more), and, from the perspective of economics/finance, that is the height of irrationality. Investing effects such as the disposition effect are much discussed precisely because they are frequently charged with destroying wealth. Myopic loss aversion seems, on the face of it, to be irrational. Certainly, the importance of avoiding framing effects is a central theme in popular investing books, such as The Little Book of Behavioral Investing: How Not to Be Your Own Worst Enemy (Montier, Reference Montier2010).

2.4 Beyond the rationality wars: A radical proposal

The framing experiments played a key role in the “rationality wars” – an interdisciplinary debate about whether the extensive literature on cognitive biases and widespread fallacies in reasoning shows that human beings are in some sense intrinsically irrational.Footnote 3 The rationality wars seem to have ended in the manner of the battles reported by Xenophon and Thucydides, with both sides raising victory monuments, despite devastating and roughly equal casualties on both sides.

In one important respect, though, both sides of the rationality wars missed a fundamental point. Even those who contested the claim that human beings are intrinsically irrational, never cast doubt on the intrinsic irrationality of framing effects. This paper shifts the terms of engagement. The focus on the canonical experiments has blinded us to the existence of rational framing effects. These framing effects are fundamentally different kind from those we have been looking at up to now.

In the classic risky choice and valence-consistent framing experiments, subjects typically fail to recognize that the two proffered outcomes are equivalent, and so that they are in the grip of a framing effect. One indication is that subjects typically back-pedal when the framing effect is pointed out to them, and presenting both frames simultaneously works as a debiasing effect, as in Bernstein, Chapman, and Elstein (Reference Bernstein, Chapman and Elstein1999).Footnote 4

The rational framing effects I will be discussing are very different. They all involve subjects knowingly and consciously valuing outcomes or actions differently as a function of how they are framed. This situation might be represented as follows, where “o” represents the outcome: The agent prefers F1(o) to A, for some A, but also prefers A to F2(o), where F1 and F2 are known to be different ways of framing the same outcome.

The next section motivates the general idea that there can be rational preferences with the structure just described – and hence that there can be rational framing effects.

3. Motivating the alternative: Rational framing effects?

3.1 Quasi-cyclicality versus cyclicality

Previous discussions of framing effects have failed to make an important distinction.

There are good reasons to think that it is irrational to have preferences that are cyclical. A decision-maker has cyclical preferences when, for example, she simultaneously prefers A to B, B to C, and C to A. A decision-maker with cyclical preferences will never be able to decide to do what she prefers most (assuming that transitivity holds). For each of A, B, or C, there will always be something she prefers to it.Footnote 5

In contrast, this paper focuses on decision problems where the decision-maker is aware that there is a single outcome framed in different ways and nonetheless insists on evaluating it differently in the two frames. As suggested earlier, this situation might be represented as follows, where “o” represents the outcome: She prefers F1(o) to A, for some A, but also prefers A to F2(o), where F1 and F2 are known to be different ways of framing the same outcome. I term this pattern of preferences quasi-cyclical. Figure 1 illustrates the difference between cyclical and quasi-cyclical preferences.

Figure 1. Diagram on the left shows the structure of cyclical preferences. Assuming the transitivity of preference, it has the counter-intuitive consequence that everything is preferred to itself, and also that everything has something that is preferred to it. On the right is an illustration of quasi-cyclical preferences. Here there is no circle, even though the decision-maker knows that F1(o) and F2(o) are different ways of framing o.

You might object: How can these be different? Surely, quasi-cyclicality just collapses into cyclicality? If I know that F1(o) and F2(o) are different ways of framing the same outcome, then surely that outcome itself is all that matters for my preferences and choice – how it is described or framed should be irrelevant.

Against this I suggest that the objects of preference are framed outcomes. There is no such thing as making choices over a purely extensional opportunity set, independent of any way of describing or framing the things in it. We cannot help but see the objects of choice as framed, or described, or conceptualized in certain ways. As a matter of fact, we often do ignore these framings and in effect choose and reason as if we were choosing and deliberating about a purely extensional opportunity set. But some of the time we do not, and instead allow framings and descriptions to influence our choices. When we do that, we are not choosing between outcomes, viewed completely neutrally, nor between frames or descriptions, viewed as cognitive or linguistic entities. Rather we choose between outcomes framed in a certain way. This is how quasi-cyclical preferences arise. (For more on the objects of preference, in the specific context of how it can be rational to have quasi-cyclical preferences, see sect. 3.4).

Before looking at specific examples of quasi-cyclical preferences in sections 4 through 6, I review general theoretical reasons for my way of thinking about preferences and, by extension, for the idea that there can be rational, quasi-cyclical preferences (and hence, rational framing effects).

3.2 Complexity, emotion, and framing: Three working hypotheses

Classical decision theory explicitly adopts a Humean model of rational decision-making, treating reason as a slave of the passions. In the theory of expected utility, a preference order is taken as given (reconstructible, in the ideal case, from patterns of suitably consistent choices), and the decision-maker's task is to maximize utility relative to that preference order. Decision theory is silent on where those preferences might come from. And a rational decision-maker's preferences are constrained only by considerations of consistency, as given, for example, by axioms such as transitivity and substitution (Bermúdez, Reference Bermúdez2009, Ch. 2; Harsanyi, Reference Harsanyi, Butts and Hintikka1977; Jeffrey, Reference Jeffrey1983).

Emotions and reason cannot be as insulated from each other as this instrumentalist picture suggests, however. Numerous studies have shown, for example, that integral emotions (i.e., those directly relevant to the task at hand) play an important role in modulating decision-making (see Loewenstein & Lerner [Reference Loewenstein, Lerner, Davidson, Goldsmith and Scher2003] for a review, as well as the influential neuropsychological data reported in Damasio [Reference Damasio1994] and Bechara, Damasio, Damasio, & Lee [Reference Bechara, Damasio, Damasio and Lee1999]). There is strong evidence also that incidental emotions influence decision-making (e.g., Keltner & Lerner, Reference Keltner, Lerner, Fiske, Gilbert and Lindzey2010; Lerner & Keltner, Reference Lerner and Keltner2000).

Particularly important for framing and quasi-cyclical preferences is that emotions are multi-dimensional phenomena. Current research on emotions has largely moved away from the traditional idea (e.g., Russell, Reference Russell1980) that emotions influence decision-making and behavior through one or both of arousal and valence. Instead, contemporary theories identify several different dimensions along which emotions vary. According to the Emotion-Imbued Choice model, for example, there are six dimensions: certainty, pleasantness, attentional activity, anticipated effort, individual control, and others' responsibility (Lerner, Li, Valdesolo, & Kassam, Reference Lerner, Li, Valdesolo and Kassam2015). Adolphs and Anderson have a different list, which includes scalability, valence, persistence, generalization, global coordination, automaticity, and social communication (Adolphs & Anderson, Reference Adolphs and Anderson2018). This multi-dimensional perspective opens up the possibility that different framings of a decision problem can elicit different dimensions of emotions, and so engage the motivational system in different ways.

Relatedly, decision theorists and philosophers have proposed thinking about decision-making in multi-dimensional terms. Keeney and Raiffa (Reference Keeney and Raiffa1976) develop the idea that decision-making involves multiple different criteria with inevitable trade-offs between them. The field of multi-attribute utility analysis (or multi-criteria decision-making) proposes tools for solving this type of problem.

A more dramatic development of this basic idea has emerged in moral philosophy, where several authors have argued that many decisions, including those traditionally known as moral dilemmas, involve incommensurable values that cannot be compared on a single scale or ordering. The notion of transformative experiences developed by Paul explores a similar idea, where the incomparability lies between value systems before and after some transformative event (Paul, Reference Paul2014).

These very different but converging ideas suggest a working hypothesis for how frames factor into decision-making.

(H1) Frames and framing factor into decision-making by one dimension/attribute/value of the decision problem highly salient, which influences how the subject engages emotionally and affectively.

H1 in turn suggests two further hypotheses specifically about quasi-cyclical preferences. The first has to do with when they will arise, namely, in situations with multiple dimensions/attributes/values pulling in different directions:

(H2) Quasi-cyclical preferences are likely to be found in decision problems that are sufficiently complex and multi-faceted that they cannot be subsumed under a single dimension/attribute/value. Different frames engage different affective and emotional responses, which the decision-maker cannot resolve either by ignoring all the frames except one or by subsuming them into a larger frame.

If H2 correctly characterizes how quasi-cyclical preferences can arise, then that suggests when it will be rational (i.e., correct and appropriate from a normative perspective) to have such preferences:

(H3) Framing effects and quasi-cyclical preferences can be rational in circumstances where it is rational to have a complex and multi-faceted response to a complex and multi-faceted situation.

The next sub-section brings these three working hypotheses to life with two dramatic literary examples of quasi-cyclical preferences. In section 3.4 I motivate H3 in more detail.

3.3 Quasi-cyclical preferences: Agamemnon and Macbeth

3.3.1 Agamemnon at Aulis

The chorus in Aeschylus's Agamemnon tells the story of Agamemnon's sacrifice of his daughter Iphigenia. Agamemnon is leading the Greek fleet against Troy to avenge the abduction of Helen by Paris. The fleet is becalmed at Aulis when two eagles swoop down to kill and eat a pregnant hare. It is a portent, which the prophet Calchas interprets as reflecting the displeasure of the goddess Artemis at the prospect of innocents being killed at Troy. The lack of wind has the same source. The only solution (although it is not clear why!) is for Agamemnon to sacrifice to the goddess his own daughter Iphigenia.

The chorus recalls Agamemnon's struggle:

And I can still hear the older warlord saying,

“Obey, obey, or a heavy doom will crush me! –

Oh, but doom will crush me

once I rend my child,

the glory of my house –

a father's hands are stained,

blood of a young girl streaks the altar.

Pain both ways and what is worse?

Desert the fleets, fail the alliance?

No, but stop the winds with a virgin's blood,

feed their lust, their fury? – feed their fury! –

Law is law! –

Let all go well.

(Aeschylus, Agamemnon. Translated by Robert Fagles [Fagles, Reference Fagles1977])

Although Aeschylus does not put it quite this way, Agamemnon is grappling with quasi-cyclical preferences. There is a single option, bringing about the death of Iphigenia, that Agamemnon frames in two different ways – as Murdering his Daughter, on the one hand, and as Following Artemis's Will, on the other. His alternative is Failing his Ships and People (by refusing to make the sacrifice). Agamemnon's dilemma is that he evaluates the death of Iphigenia differently, depending on how it is framed. Both of the following are true.

(A) Agamemnon prefers Following Artemis's Will to Failing his Ships and People.

(B) Agamemnon prefers Failing his Ships and People to Murdering his Daughter.

But he knows, of course, that Following Artemis's Will and Murdering his Daughter are the same outcome, differently framed.

3.3.2 Macbeth at inverness

Shakespeare's Macbeth provides another dramatic example of quasi-cyclical preferences.Footnote 6

In Act 1, Macbeth, Thane of Glamis, is told by the witches that he will become both Thane of Cawdor and King of Scotland. When the first part of the prophecy is fulfilled (by King Duncan's executing the current Thane and granting the title to Macbeth), Macbeth begins to think about making the second part of the prophecy come true by killing Duncan. Providentially Duncan arrives under Macbeth's roof, and Lady Macbeth encourages her husband to assassinate the King. But still Macbeth has his doubts. On the one hand, he recognizes that killing Duncan would make him King – and surely that's worth the risk:

If it were done when ’tis done, then ’twere well

It were done quickly. If the assassination

Could trammel up the consequence, and catch

With his surcease success; that but this blow

Might be the be-all and the end-all here,

But here, upon this bank and shoal of time,

We'd jump the life to come.

(Act I, Sc. 7)

But, as he immediately recognizes, he has two different obligations to Duncan. He is both his host and his pledged kinsman. On both counts his duty is to protect Duncan, not murder him.

He's here in double trust:

First, as I am his kinsman and his subject,

Strong both against the deed; then, as his host,

Who should against his murderer shut the door,

Not bear the knife myself.

(Act I, Sc. 7, lines 1–7)

So, with apologies to Shakespeare, the following two propositions both seem to be true.

(C) Macbeth prefers Fulfilling his Double Duty to Duncan to Murdering the King.

(D) Macbeth prefers Bravely Taking the Throne to Backing Away from his Resolution to Make the Prophecy come True.

He knows, of course, that to fulfill his double duty to Duncan is to back away from his resolution to make the prophecy come true – and likewise that bravely taking the throne is murdering the King. So, he has quasi-cyclical preferences.

Someone might object: Agamemnon and Macbeth certainly have quasi-cyclical preferences. They are each knowingly and consciously subject to a framing effect. But why should we think that they are being rational? Surely, Agamemnon and Macbeth are trapped in a cycle of irrationality, from which the only escape is to settle on one framing rather than the other?

The next section replies to this objection.

3.4 The rationality of quasi-cyclical preferences

For classical decision theorists, preferences are rational when, and only when, they are suitably consistent – that is, when, and only when, they are in accordance with the axioms of decision theory, such as transitivity and substitution. This way of thinking about rationality makes most sense if we think of preferences as revealed in choices and as having no content over and above the choices to which they give rise.

Leonard Savage, the founder of modern decision theory, was very clear that such a model of choice and preference is really only applicable to what he called “small worlds” – environments where a decision-maker can be assumed to have exhaustive knowledge of all available actions and outcomes and has preferences completely defined over all those actions and outcomes. Few, if any, real-world decisions fit this model. More typically, decision problems have to be constructed. Decision-makers have to work out for themselves what the available actions are and to what outcomes they might lead.

At the same time, preferences are not basic. They are made for reasons. And the process of constructing a decision problem is simultaneously a process of identifying reason-giving aspects of different possible outcomes and possible actions. Whereas standard decision theory assumes that these processes are either unnecessary, or have somehow been completed, before considerations of rationality come into play, it is plausible that there are normative constraints upon them. In particular, when a decision problem is complex and multi-faceted, a rational decision-maker (someone who is deliberating as they ought to be deliberating) should be sensitive to the full range of potential reasons that there might be for choosing one way rather than another.

This is how frames come into play. Reasons are frame relative. Macbeth is an extreme example. You need to look at the world in a very particular way for regicide to seem a good idea, and it is only when things are framed in that way that Macbeth's ambition can get translated into action. Switch the frame and a different set of reasons come into play. In Macbeth-type decision problems, what counts as a reason from within the perspective of one frame is so recessive as to be almost invisible from the other. But then someone who is trying to do justice to the complexity of the decision situation needs to be sensitive to the possibility of multiple possible framings. With that sensitivity comes the possibility of quasi-cyclical preferences. But those quasi-cyclical preferences have emerged from a decision-maker seeking to satisfy the basic rationality requirement of doing justice to the complexity of the situation. They inherit the rationality of the process that generated them.

The Agamemnon and Macbeth cases bring out in striking relief an abstract structure that reappears in much more everyday situations of direct relevance to cognitive and behavioral scientists. There are plenty of complex and multi-faceted decision problems that do not involve filicide or regicide, but that can be illuminated when understood as involving rational framing effects. The remainder of this paper will discuss three of them.

4. Application 1: Framing and quasi-cyclical preferences in self-control

4.1 Self-control, time-inconsistent preferences, and effortful willpower

Since the influential work of Ainslie, Rachlin, and others, failures of self-control have been conceptualized as preference reversals resulting from a particular way of discounting the future (Ainslie, Reference Ainslie1974, Reference Ainslie1992, Reference Ainslie2001; Rachlin, Reference Rachlin2000, Reference Rachlin and Bermúdez2018).

To discount the future is to assign less utility now to a future good than one expects to derive from it when it is eventually reached. A discounting function describes how the degree to which an agent discounts a future good is related to the delay until the reward is received. There are two broad families of discount function.

Exponential discount functions remain constant over time, with the ratio between how much one discounts a future good at the start and the end of any given temporal interval a function only of interval length. So, the impact of a day's delay will be the same tomorrow as 25 years in the future. For that reason, exponential discounting is described as time consistent.

Hyperbolic discount functions are time-inconsistent, because the ratio of the discount function is not constant. The difference between having $10 today and receiving $11 tomorrow is much greater than the difference between having $10 100 days into the future and having $11 in 101 days.

Hyperbolic discount functions permit preference reversals in which a short-term smaller sooner (SS) reward can, at the moment of temptation and despite the agent's best-laid plans, seem more attractive than the long-term larger later (LL) reward. As the moment of choice approaches, the discount function for SS steepens more rapidly than the discount function for LL (because SS is more imminent than LL), which allows SS's utility to exceed that of LL.

This means that an agent exercising self-control must change the shape of her discount function, which raises two obvious questions:

(Q1) How does this change in the discount function take place?

(Q2) Are there techniques that make it easier for subjects to change the shape of their discount functions (and hence to resist temptation)?

Traditionally, Q1 has been answered through the construct of effortful willpower, as developed within the theory of ego depletion proposed by Baumeister and others (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Muraven, & Tice, Reference Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Muraven and Tice1998). The basic idea is that self-control requires energy, which is a limited resource and can become depleted. However, the theory of ego depletion does not offer clear guidance in response to Q2. It explains how self-control occurs and why it might fail, but not how it might be improved. Moreover, there are problems with replicating the key effects supporting the ego depletion model.Footnote 7

Framing offers a better approach to both Q1 and Q2. The basic idea is that cases of self-control can have the following structure. An agent committed to a long-term goal (LL) is at risk of succumbing to temptation (SS), because at the moment of choice they prefer SS to LL. They prefer the extra drink to the clear head in the morning, or the extra hour in bed to results of the fitness regime. They can resist the temptation, however, by reframing either or both the temptation or the long-term goal.

Framing approaches to self-control are well-supported experimentally (section 4.2) and also offer practical tools for achieving self-control and resisting temptation (section 4.3).

4.2 Self-control and framing: Evidence from psychology and neuroscience

4.2.1 Framing in the delay of gratification paradigm

The delay of gratification paradigm is an influential paradigm for studying self-control (Mischel & Ayduk, Reference Mischel, Ayduk, Baumeister and Vohs2004; Mischel & Moore, Reference Mischel and Moore1973; Mischel, Shoda, & Rodriguez, Reference Mischel, Shoda and Rodriguez1989). It offers a tool for studying how young children are able to delay immediate gratification (SS) in favor of long-term goals (LL). The children are told that the experimenter needs to go away, but when the experimenter returns, they will receive a delayed reward of, say, two cookies or two marshmallows (i.e., the LL). They can wait for LL or, at any time, while the experimenter is away, they can ring a bell to receive an immediate reward of a single cookie or marshmallow (the SS).Footnote 8

Mischel and collaborators suggested that the experimental behavior can be explained through the interaction between “hot” and “cold” cognitive-affective systems – a version of the dual process theory (Evans, Reference Evans2008; Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011). Here is how Mischel and Ayduk state the contrast:

Briefly, the cool system is an emotionally neutral, “know” system: It is cognitive, complex, slow, and contemplative. Attuned to the informational, cognitive, and spatial aspects of stimuli, the cool system consists of a network of informational, cool nodes that are elaborately interconnected to each other, and generate rational, reflective, and strategic behavior…. In contrast, the hot system is a “go” system. It enables quick, emotional processing: simple and fast, and thus useful for survival from an evolutionary perspective by allowing rapid fight or flight reactions, as well as necessary appetitive approach responses. The hot system consists of relatively few representations, hot spots (e.g., unconditioned stimuli), which elicit virtually reflexive avoidance and approach reactions when activated by trigger stimuli. This hot system develops early in life and is the most dominant in the young infant. (Mischel & Ayduk, Reference Mischel, Ayduk, Baumeister and Vohs2004, p. 109)

This dual process theory explains why the two discount curves behave as they do. With SS at a safe (temporal) distance, the cool system dominates and so the utility attached to the two outcomes reflects the agent's considered preference for the added benefit of LL. The closer the agent gets to SS, however, the more the hot system kicks in and so the slope of the valuation function steepens, until the SS discount curve eventually intersects the LL discount curve and paves the way for the weak-willed response. Mischel and Ayduk make this very point, describing some of the early delay of gratification studies:

it became clear that delay of gratification depends not on whether or not attention is focused on the objects of desire, but rather on just how they are mentally represented. A focus on their hot features may momentarily increase motivation, but unless it is rapidly cooled by a focus on their cool informative features (e.g., as reminders of what will be obtained later if the contingency is fulfilled) it is likely to become excessively arousing and trigger the “go” response. (Mischel & Ayduk, Reference Mischel, Ayduk, Baumeister and Vohs2004, p. 114)

Here are some of the studies that they identify as pointing to what I will term the frame-dependence of discount curves.

• Mischel and Moore (Reference Mischel and Moore1973) found that performance on the delay of gratification paradigm varied when children were presented with images of the rewards, as opposed to the rewards themselves. They reasoned that presenting an iconic representation of the reward would present the reward in a “cool” light, highlighting its cognitive and informational features, whereas presenting the reward itself would highlight its motivational features and engage the “hot” system. Children who had the actual reward in front of them performed much worse on the delay of gratification task than children who merely had a picture of the reward in front of them.

• Mischel and Baker (Reference Mischel and Baker1975) divided children undergoing delay of gratification experiments for marshmallows and pretzels into two groups and cued them to think about the rewards differently. One group, the “cold” group, was primed to think about the marshmallows as “white, puffy clouds” and the pretzels as “little, brown logs.” Children in the second, “hot,” group were cued to think about obvious motivational features of the marshmallows and pretzels – as “yummy and chewy” and “salty and crunchy respectively.” As predicted, children in the cold group were significantly better able to withstand temptation than children in the hot group – a mean of 13 minutes before ringing the bell for the SS reward, as opposed to a mean of 5 minutes.

It seems that the way in which the reward is framed directly affects rate of change of the SS discount curve, and so the point at which the SS discount curve crosses the LL discount curve. The language of “framing” is very natural here, because “white puffy clouds” and “yummy and chewy” are clearly different ways of describing the same reward – and likewise “little brown logs” and “salty and crunchy.”

These findings suggest positive strategies for enhancing self-control. Agents can ensure that hot representations of SS are counter-balanced and kept in check by cooler representations that emphasize, for example, the long-term consequences of succumbing to temptation. Likewise, they can represent LL in ways that engage the hot system, thus steepening the LL discount function and preventing the SS discount function from crossing it. (More on this in sect. 4.3.)

4.2.2 Framing in the hidden zeros paradigm

There is evidence that how rewards are valued is modulated by the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, vmPFC, and striatum areas (Hare, Camerer, & Rangel, Reference Hare, Camerer and Rangel2009), while willpower exertion is typically tied to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, dlPFC (Figner et al., Reference Figner, Knoch, Johnson, Krosch, Lisanby, Fehr and Weber2010). These neuroanatomical facts connect up suggestively with the reflections above about conceptualizing self-control as a matter of changing the slopes of the discount curves for SS and LL. To change the slope of the discount curve for a reward is, in essence, to change how that reward is valued. So, if the neural basis for reward valuation is distinct from the neural basis for effortful willpower, then it seems at least in principle possible for self-control to be exercised without engaging willpower. But how?

Magen, Kim, Dweck, Gross, and McClure (Reference Magen, Kim, Dweck, Gross and McClure2014) tested the hypothesis that self-control can be enhanced by changing how the rewards are framed. They recruited an independently documented framing effect – the hidden zero effect. Experiments on discount curves typically present choices such as: “Would you prefer $5 today or $10 in a month's time?.” This is in hidden zero format, because it does not make explicit that if you opt for $5 today, you will receive $0 in a month's time and, correlatively, that if you opt for $10 in a month's time you will receive $0 today. To include the relevant non-rewards in the description of the choice is to frame the choice in an explicit zero format – for example, “Would you prefer $5 today and $0 in a month's time, or $0 today and $10 in a month's time?”

Consistent with earlier results (Magen, Dweck, & Gross, Reference Magen, Dweck and Gross2008), participants discounted the future at lower rates with outcomes presented in the explicit zero format than in the hidden zero format (even though the outcomes in the two formats can immediately be seen to be equivalent).

Moreover, the neural data confirmed the hypothesis that the reframing is effective in enabling self-control without the exercise of effortful willpower, because variation in activity in the reward areas was sufficient to explain different valuations in the two conditions. Moreover, when subjects were presented with explicit choices, there was significantly less activation in the dlPFC (the area correlated with willpower) when LL was selected in the explicit zero format than when it was chosen in the hidden zero format. In other words, less willpower was required when LL was framed in a cool manner.

4.3 Modeling self-control with quasi-cyclical preferences

To see how to model the connection between framing and self-control in the quasi-cyclical preferences framework, consider Figure 2, which represents the situation as a sequential choice problem (McClennen, Reference McClennen1990).

Figure 2. Paradigm case of self-control represented as a sequential choice problem. The moment of planning is at time t 0 with the moment of choice at time t 1, when the agent chooses between the immediate smaller sooner temptation (SS) and the delayed larger later reward (LL).

The moment of temptation is marked as t 1. At that moment, the utility of SS outweighs the utility of LL (because of the preference reversal explained in sect. 4.1). According to the basic maxim of decision theory, therefore, the agent should go down at t 1, rather than hold out for LL – because that is the action that will maximize her expected utility at the moment of choice (t 1).

From the perspective of classical decision theory, therefore, the exercise of self-control is problematic. It seems to be counter-preferential and so counter-rational (Bermúdez, Reference Bermúdez2009, Reference Bermúdez2018, Reference Bermúdez and Mele2020b). For that reason, decision theorists have developed a number of strategies for explaining how it can be rational to hold out for LL. These include theories of sophisticated choice (Strotz, Reference Strotz1956) and resolute choice (Holton, Reference Holton2009; McClennen, Reference McClennen1990). None of these has found universal acceptance. Sophisticated choosers essentially avoid the problem through precommitment strategies (e.g., Odysseus tying himself to the mast, to take a much-discussed example). Resolute choice theories are inconsistent with the basic axioms of decision theory, and also have serious difficulties explaining how the counter-preferential choice can actually be made at time t 1 (Bermúdez, Reference Bermúdez2018).

In contrast, incorporating frames preserves the basic principle of expected utility maximization. Figure 3 shows how quasi-cyclical preferences can come about in self-control cases. The agent frames LL in two different ways. On the one hand, she frames it simply as the long-term reward. Picking up on the Mischel discussion from section 5.2.1, this could be termed the cool framing. But at the same time, she also frames LL as Having Successfully Resisted SS. This is a hot frame, highlighting the struggle over temptation.

Figure 3. Reframing the decision problem in Figure 2.

The agent assigns more utility to SS than to LL. This explains why she is in the grip of temptation – if it were not the case, there would not be a problem of self-control at all. At the same time, though, she assigns more utility to Having Successfully Resisted SS than she does to SS. The value attached to Having Successfully Resisted SS can reflect more than just the LL reward itself. It might, for example, reflect the perceived “virtue” of having overcome temptation. Or it might be taken as a signal of how the agent will react in the future (if I manage to resist temptation here, then I will be more likely to do so in the future).

This explains how she is able to exercise self-control. Moreover, it explains how her self-control is rational, since she is following the option that she most prefers and so is maximizing utility. The preferences are quasi-cyclical because she is perfectly well aware that LL and Having Successfully Resisted SS are different ways of framing the same outcome. So, we have a rational framing effect.

This proposal is consistent with the experimental evidence reviewed in section 4.2 as well as with the general model of time-inconsistent preferences outlined in section 4.1. Discount curves are frame-relative and having multiple frames allows for the possibility that there is a framing of one or both SS and LL on which the two discount curves do not cross. More generally, self-control provides a clear illustration of H1 through H3. Self-control situations are typically complex and multi-faceted (H2), sufficiently so that it is rational to have quasi-cyclical preferences (H3). The different framings operate by making one dimension of the decision problem particularly salient.

5. Application 2: Framing in game theory

Game theory is the mathematical theory of strategic choice. In a strategic decision the outcomes for each agent are a function of both what she herself does and what other agents do. Classical decision theory (expected utility theory) is parametric (Bermúdez, Reference Bermúdez2015a, Reference Bermúdez and Peterson2015b) – that is, the outcomes are fixed by what the agent does and by the state of the world. Expected utility theory cannot work in strategic decision problems because strategic decision problems have two features:

(1) The actions of the different agents are independent of each other – neither agent is constrained by another to act in a certain way.

(2) Different agents' actions are interdependent with respect to rationality – what it is rational for me to do depends upon what I think it would be rational for other agents to do, but what it would be rational for other agents to do depends upon what they think it is rational for me to do.

The basic solution concept in game theory is Nash equilibrium. A Nash equilibrium is a set of strategies such that each player's strategy is a best response to the strategies of the others – that is, none of the players can unilaterally improve their position relative to the strategies of the other agents (Shoham & Leyton-Brown, Reference Shoham and Leyton-Brown2008 provide all the details).

In two well-known respects, game theory is on a much less firm footing than expected utility theory. Looking at two foundational problems will help us see how frames can be important in game theory.

5.1 Foundational problems in game theory

5.1.1 The equilibrium selection problem

Nash's theorem says that every strategic interaction satisfying some basic conditions has at least one equilibrium solution. But many games have multiple equilibrium solutions. There is no generally accepted method within game theory for identifying one solution as more rational than another, even in situations where many people find it obvious that there is a unique rational solution.

Stag Hunt (SH) provides a good example (Skyrms, Reference Skyrms2012). Two players have a choice between hunting hares or hunting a stag. The stag is the better reward, but requires collaboration, while hunting a hare is better if the other player is not doing the same. Here is the payoff table:

Each cell represents the payoff to Row, first, and then to Column. There are two pure Nash equilibria (Stag, Stag) and (Hare, Hare), as well as a probabilistic mixed strategies equilibrium. Game theory provides tools for identifying the equilibria, but not for choosing between them. This is the equilibrium selection problem.

Many criteria have been proposed for equilibrium selection (Harsanyi & Selten, Reference Harsanyi and Selten1988). Two prominent candidates are:

• Pareto superiority (or Payoff dominance): Choose the equilibrium such that no player is worse off and at least one player is better off.

• Risk dominance: Choose the least risky equilibrium.

In Stag Hunt these two criteria pull in different direction. (Stag, Stag) is Pareto superior, but (Hare, Hare) is risk dominant. It is fair to say that neither, nor any other, candidate for equilibrium selection has gained widespread acceptance.

5.1.2 The problem of non-equilibrium solutions

Game theory is a normative theory, and so not straightforwardly opens to empirical counterexample. Nonetheless, it is reasonable to expect normative theories to reflect the realities of practical decision-making, and there is strong experimental and anecdotal evidence that subjects often adopt non-equilibrium solutions in social dilemma games – typically when non-equilibrium solutions reflect considerations of fairness and collaboration to which Nash equilibrium is blind.

The one-shot Prisoner's Dilemma (PD) has been much studied in this context. As is well known, Cooperate is a dominated strategy in PD, where mutual Defection is the only pure-strategies Nash equilibrium. A well-known meta-analysis (Sally, Reference Sally1995) looked at 130 experiments on social dilemmas such as PD and found a mean cooperation rate across the studies of 47.4%. (For similar effects see Heuer & Orland, Reference Heuer and Orland2019; Janssen, Reference Janssen2008; Pothos, Perry, Corr, Matthew, & Busemeyer, Reference Pothos, Perry, Corr, Matthew and Busemeyer2011.)

This generates two significant questions.

The descriptive question:

Can we give a principled account of why subjects systematically diverge from equilibrium solutions?

The normative question:

Can we give a principled account of how it might be rational to diverge from Nash equilibrium?

Framing and quasi-cyclical preferences allow us to answer both questions.

5.2 Framing in games: Bacharach's proposal

Michael Bacharach was a pioneer in this area, focusing primarily on the descriptive question particularly in the posthumously published (Bacharach, Reference Bacharach2006). Unusually in game theory, his ideas are richly informed by work on the psychology of groups and cooperation.

Bacharach's basic idea is that strategic interactions can be framed in different ways. He focuses in particular on two frames, which I will call the “I”-frame and the “we”-frame, although this is not his standard terminology.

“I”-frame

In the “I”-frame, agents look only at their own payoffs, employing the type of best response reasoning that seeks a Nash equilibrium.

“We”-frame

A team reasoner thinks about the payoff table from the perspective, not of an isolated individual, but instead from the perspective of a team member, or group member.

These two frames are extensionally equivalent. Games are defined by their payoff tables, and the payoff table remains constant across the two frames – the rewards to each player in each possible outcome are the same in the “I”-frame and the “we”-frame. The differences lie in which aspects and properties of the payoff table are salient in each frame. “I”-frame reasoners look only at their portion of the joint outcome, ignoring the outcomes for other players. In contrast, “we”-frame reasoners look at the total outcome profile – the payoffs in each outcome, not just for themselves, but also for the other players.

The “we”-frame makes possible what Bacharach terms team reasoning – reasoning based on the total outcome profile, not just the player's individual profile. The simplest form of team reasoning that he considers (mode-P reasoning) ranks available strategy combinations according to Pareto superiority – one strategy combination is Pareto-superior to another just if it makes at least one player better off and does not make any player worse off.Footnote 9 In the SH game from section 5.1.1, (Stag, Stag) is Pareto-superior to (Hare, Hare), and so is the choice of a mode-P reasoner.

Bacharach conjectures that mode-P and other forms of team reasoning are likely to be engaged in interactions with the following characteristics.

Common interests

There are at least two outcomes such that in one the interests of both players are better served than in the other.

Strong interdependence

Each player perceives that they will do well only if the other does something not guaranteed by standard, best-response reasoning (and they perceive that the other player perceives the same thing, etc.).

Typical social dilemmas such as PD, SH, and Chicken have both characteristics, and so prime for the “we”-frame.

Bacharach's account is suggestive. However, Pareto optimality is not the most useful concept in this context. In a zero-sum game (such as the widely studied Ultimatum game where players have to agree on how to divide a good), every strategy-pair is Pareto-optimal. Relatedly, Pareto-optimality is inconsistent with any form of fairness-based redistribution.

Moreover, Bacharach's account only answers the descriptive question and has nothing to say about the normative question of how or why it might be rational to adopt one frame rather than another. Discussions of social dilemmas in game theory often incorporate their own framing effects. Joint action is typically framed as cooperative, collaborative, and desirable. Of course, though, cooperation is not always desirable. The “we”-frame is adopted by genocidal mobs as well as by altruists. Bacharach, however, explicitly steers clear of normative questions.

5.3 Quasi-cyclical preferences in game theory

A more nuanced approach to frames in game theory would open up a space for reasoning across frames. As we will seem, such reasoning can be conceptualized through rational framing effects.

Reasoning across frames might seem impossible, particularly for someone who thinks that the “I”-frame and the “we”-frame are at bottom incommensurable. That belief is promoted by the framing effect just referred to, as reflected by the standard terminology in PD. The outcome of individualistic reasoning labeled as mutual defection and the outcome of team reasoning labeled as mutual cooperation. From an individualistic perspective, the optimal outcome is often described as being a free rider, receiving the benefits without taking the costs. This is all loaded terminology, and it is easy to see why the contrast between the “I”-frame and the “we”-frame might come across as a contrast between selfishness and cooperation.

Against this I suggest that, while frames are symbiotically connected to values, it is possible for different frames to express the same value in a way that provides an anchoring point for instrumental reflection. Here is an illustration from the game known as Chicken, showing how the value of fairness can lead a player to reason her way from the “I”-frame to the “we”-frame.

Like many two-person games, Chicken can be framed in multiple ways. Sometimes it is framed as a Hawk-Dove game, of the type made famous in the film Dr. Strangelove. It can also be framed as what is sometimes called the Snowdrift game. Two people are stranded by a snowdrift in their car. Each can either Stay Inside or leave the warmth of the car and Dig Snow, yielding the following payoff table.

There are two, pure-strategy Nash equilibria (Stay inside, Dig snow) and (Dig snow, Stay inside), as well as a mixed-strategies equilibrium in which each player plays Stay inside with probability 2/3 and Dig snow with probability 1/3.

From the perspective of the “I”-frame, Row ranks the outcomes as follows – in descending order of preference:

(1I) Stay inside, Dig snow

(2I) Dig snow, Dig snow

(3I) Dig snow, Stay inside

(4I) Stay inside, Stay inside

Column's “I”-frame ranking is the same, but with (1) and (3) reversed.

The “we”-frame ranking is the same for both, assuming that both are motivated by considerations of fairness:

(2WE) Dig snow, Dig snow

(1WE) Stay inside, Dig snow

=

(3WE) Dig snow, Stay inside

(4WE) Stay inside, Stay inside

Game theorists typically take preferences as given, but it is reasonable to ask where they come from. Row ranks (2I) over (3I). Why? Presumably partly because (2I) is fairer – both are sharing in the work of digging out the snowdrift. But, as Row reflects on this, he may well see that his preferred outcome (1I) is no less unfair. Then, as considerations of fairness start to take hold, Row has a compelling reason to adopt the “we”-frame and to prefer the fair strategy-pair over all others. This leaves him with the quasi-cyclical preferences (2WE) > (1I) > (2I). These preferences can be perfectly rational, because they are arrived at through a process of instrumental reasoning anchored in a frame-neutral value.

This is highly schematic, of course. But it is certainly consistent with the extensive experimental literature on Ultimatum games (introduced in Güth, Schmittberger, & Schwarze, Reference Güth, Schmittberger and Schwarze1982). In an Ultimatum game one player proposes a division of some good (typically a sum of money), which the second player can either accept or reject (in which case neither player receives anything). On standard models of economic rationality, a rational player should accept any non-zero offer. It is a very robust result, though, that most players make offers in the 40–50% range, which are typically accepted. As the offers diminish the rejection rate increases dramatically (as reviewed in Camerer, Reference Camerer2003, Ch. 2). The standard explanation is that considerations of fairness drive the effect (Kahneman, Knetsch, & Thaler, Reference Kahneman, Knetsch and Thaler1986).

Again, this provides support for H1 through H3. Games are schematic representations of complex and multi-faceted interactions (H2), in which it is rational to have quasi-cyclical preferences (H3). The different framings operate by making one dimension of the decision problem particularly salient (per H1) – the individual payoffs in the “I”-frame and the joint payoffs in the “we”-frame.

6. Application 3: Framing and quasi-cyclical preferences in interpersonal conflicts

The two previous applications have illustrated how reasoning is possible within and across frames. Frames can be tools for rational problem-solving, not just primes or nudges. The final application offers a more overarching perspective and suggests that frame-based reasoning can be deployed to overcome discursive deadlock, both public and private. As we will see, this creates, and indeed requires, rational framing effects.

6.1 Discursive deadlock as a clash of frames

Discursive deadlock, where ordinary techniques for dispute resolution and collective decision-making fail, is a characteristic of contemporary private and public discourse. Political and social commentators often wring their hands about partisan deadlock and polarization on what are euphemistically called “values issues.” These “values issues” are particularly susceptible to framing.

Gun control and gun safety are different ways of framing the same thing (restrictions on gun ownership). The right to life is not just in conflict with the right to choose, but also frames the issue of abortion very differently. Many of those who support taxing inheritances would steer well clear of support for a death tax. That there are many comparable examples, and that every hot-button issue lends itself to multiple framings, is completely unsurprising, in view of H2. These are all complex, multifaceted, and multi-dimensional issues that seem difficult, if not impossible, to subsume under a single attribute/dimension.

In fact, it can be useful to think of discursive deadlock in terms of clashes of frames, rather than clashes of values. This recognizes the possibility that a single value can underlie discursive deadlock. So, for example, some forms of deadlock about taxation can be seen as clashes between two different ways of framing the value of fairness – between fairness as equality and fairness as equity, for example (as distinguished in Deutsch [Reference Deutsch1975] and, at much greater length, in Rawls [Reference Rawls1971, Reference Rawls2001]). Fairness as equality suggests that a fair system of taxation will tax all equally (as in various types of poll tax). Fairness as equity suggests that a fair system of taxation will tax in proportion to income (or wealth more generally). If the conflict is at root a conflict about the nature of fairness, then it would seem in principle more tractable than if it is due to clashes between fundamentally different and opposed values. (Studies show, moreover, that perceptions of the fairness of distributions are themselves subject to experimentally induced framing effects. Gamliel & Peer [Reference Gamliel and Peer2006, Reference Gamliel and Peer2010] found that non-egalitarian distributions are judged fairer in positive frames [see Diederich, Reference Diederich, Traub and Kittel2020 for an overview]. More generally, frames are more susceptible to scrutiny, debate, and modification than values [Lakoff, Reference Lakoff2004]. It seems to be frames all the way down!)

But how might this type of debate and conflict resolution take place? Frame-based reasoning involves a range of skills and techniques that are recognizably similar to skills and techniques that have been studied, generally independently of each other, in different areas of social, clinical, and developmental psychology. What has hitherto been neglected, however, is the role of frames and rational framing effects.

6.2 Frame-based reasoning across discursive deadlock: Basic elements

Imagine that you are locked in a fundamental and seemingly intractable disagreement with someone. At bottom it is a clash of frames. You both agree on the facts but frame them in different and incompatible ways. The facts might concern the biological development of an embryo, the consequences of widespread gun ownership, or the statistics of wealth inequality. The clash of frames might take a familiar form: The right to life versus the denial of the right to choose; gun control versus gun safety; death tax versus inheritance tax.

It is highly unlikely that there will be any general algorithm or set of techniques for resolving this type of dispute in every case. Nonetheless, when there is a resolution, it will involve the participants going through something like the following stages of frame-sensitive reasoning.

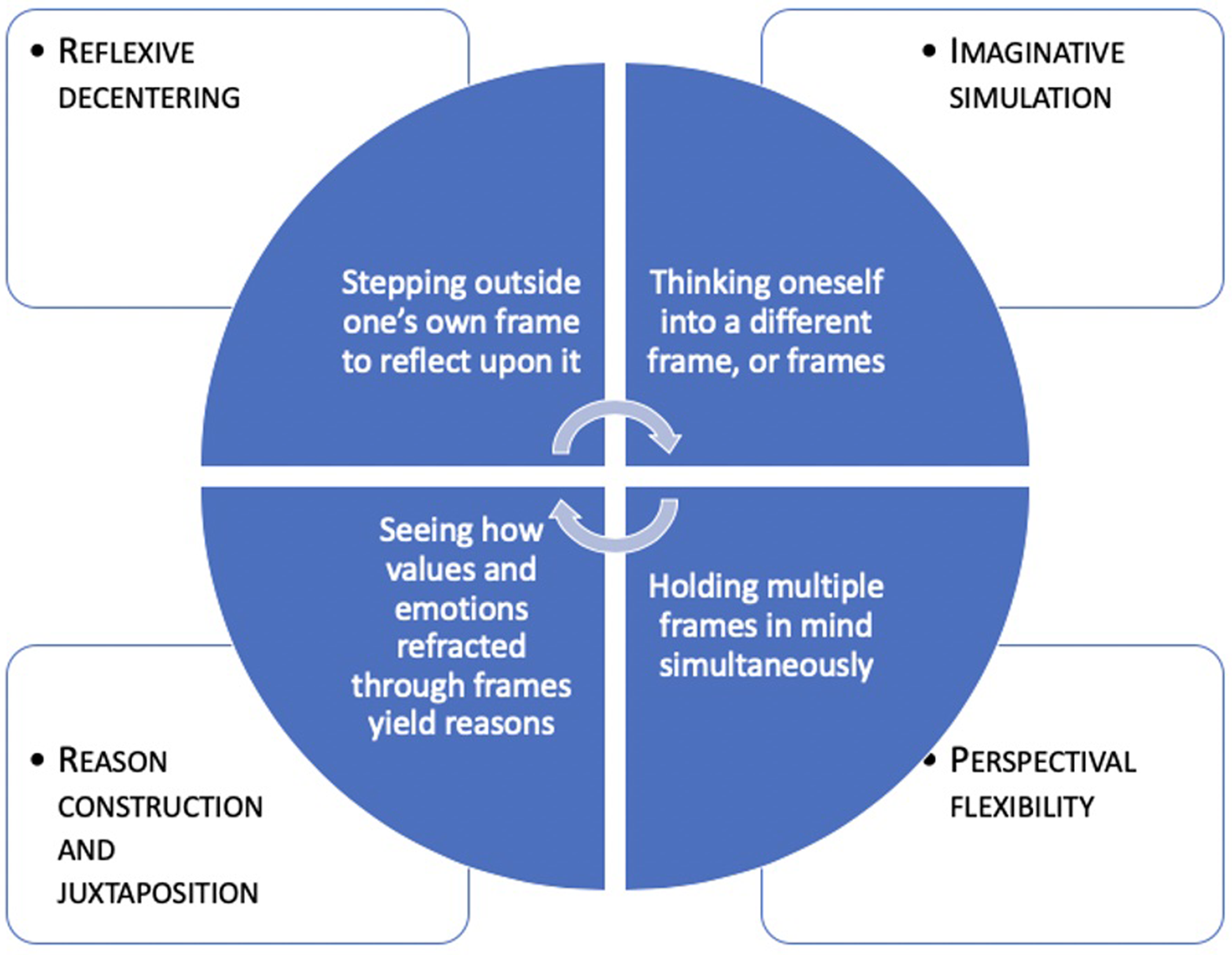

6.2.1 Reflexive decentering

Making any progress in resolving clashes of frames requires appreciating that that is what they are. So, the first step is for the participants to turn their attention from the first-level issue on which they are deadlocked and focus instead on how they are each framing that issue. Each needs to step outside their own framing in order to reflect on the frame itself.

6.2.2 Imaginative simulation

Once model frame-sensitive reasoners have used reflexive decentering to appreciate the frame-relativity of their perspective, a next step is to be open to different ways of framing the issue. This second aspect of frame-sensitive reasoning is in effect an exercise in simulation. Frame-sensitive reasoners need to imagine what it would be like to frame things completely differently, and then to simulate actually being in that frame.

6.2.3 Perspectival flexibility

Frame-sensitive reasoning requires being able to hold multiple frames in mind at once, which is how quasi-cyclical preferences can arise. This is because (as explained in sect. 3.4) a rational preference must be held for a reason and different frames bring different reasons into play. Evaluating those reasons and seeing how they interact requires being able to adopt multiple frames simultaneously.

6.2.4 Reason construction and analysis

Reflection across frames involves a decision-maker appreciating how different frames bring different reasons into play. This can happen in multiple ways, for example,

• By foregrounding one reason-giving feature while downplaying another – as emerged dramatically in the Agamemnon and Macbeth examples.

• By highlighting a reason-giving similarity to some other (appropriately framed) action or outcome. For example, GM foods can be viewed (1) under the husbandry frame, priming the similarity to thousands of years of agricultural selective breeding, or (2) under the monopoly capitalism frame, priming the similarity to various types of predatory behavior by large corporations.

• By expressing a particular value in a particular way. The community charge frame for local authority taxation in Great Britain in the 1980s emphasized fairness as equality (if the tax is a charge on services, then it is fair to charge everyone the same for equal access to services). The alternative framing, as a poll tax, highlighted its inequitable dimension.

As we will see, appreciating the force of these competing, frame-relative reasons can directly lead to quasi-cyclical preferences and rational framing effects.

The general framework is depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Key framing techniques for frame-sensitive reasoning.

6.3 Rational framing effects in frame-based reasoning

While none of the skills, techniques, and abilities in Figure 4 has been directly studied, they are analogs and developments of phenomena that have been well studied in the cognitive and behavioral sciences (Bermúdez, Reference Bermúdez2020a, Ch. 11). Looking at them in more detail brings out how they create and depend upon rational framing effects. One cannot engage in the type of frame-sensitive reasoning that will break discursive deadlock without exposing oneself to rational framing effects.

6.3.1 Reflexive decentering and the clinical psychology of decentering

Within clinical psychology decentering is a shift in one's experiential perspective on the world, away from being immersed in one's experience of other people, oneself, and the world toward being able to reflect upon the experience as if from outside it. A fundamental technique in cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is cognitive distancing, stepping back from one's own thoughts in order to reflect upon them as psychological events (as opposed to direct guides to the nature of the world and the nature of one's self) (Butler, Chapman, Forman, & Beck, Reference Butler, Chapman, Forman and Beck2006; Kazantzis et al., Reference Kazantzis, Luong, Usatoff, Impala, Yew and Hofmann2018). Self-distancing is a related concept (Kross & Ayduk, Reference Kross and Ayduk2011).

Bernstein et al. (Reference Bernstein, Hadash, Lichtash, Tanay, Shepherd and Fresco2015) and Bernstein, Hadash, and Fresco (Reference Bernstein, Hadash and Fresco2019) propose a model on which decentering emerges from three interrelated psychological processes:

Meta-awareness:

To be meta-aware of an episode of thinking is to be aware of the process of thinking itself (as opposed to its content, what it is about).

Disidentification from internal experience:

This is the experience of internal states as separate from oneself, in contrast to the human tendency to identify with subjective experience and to experience internal states such as thoughts, emotions, and sensations as integral parts of the self.

Reduced reactivity to thought content:

Decentering reduces the affective power of one's thoughts – for example, thinking of oneself as fat without feeling guilt, or thinking that one is being insulted without feeling violent rage.

Within frame-based reasoning, reflexive decentering has analogous components. First, frame-sensitive reasoners need to be able to shift perspective from their involved engagement with the world to the frame that is structuring that engagement. Second, just as the patient undergoing CBT learns to shift from internalizing to externalizing their feelings of their own worthlessness (the shift from “I am worthless” to “there is a feeling of worthlessness”), frame-sensitive reasoners need to put distance between themselves and the evaluative dimensions of the frame. With this comes, third, reduced reactivity. Dispassionate disidentification must go hand in hand with emotional and affective distancing.

6.3.2 Imaginative simulation and perspective-taking

Simulation is standardly discussed by developmental psychologists and cognitive scientists in the context of how young children acquire the complex of skills and representational abilities known as theory of mind or mindreading (see Bermúdez [Reference Bermúdez2020a] for an overview with references). According to simulation theories (Carruthers & Smith, Reference Carruthers and Smith1996; Davies & Stone, Reference Davies and Stone1995a, Reference Davies and Stone1995b), we make sense of other people's behavior by simulating them. We run our own decision-making processes off-line, taking as inputs the beliefs and desires that we think another person has. That process tells us what we ourselves would do if we had that person's beliefs and desires. Assuming that they will react similarly gives us a prediction for how they will behave.

Imaginative simulation in the context of frame-based reasoning is somewhat different. The assumption behind simulation theory is that we all have a relatively secure grip on our own psychologies, which we can then use to make sense of other people. This is not helpful for thinking about frame-sensitive reasoning. The whole point of reflexive decentering, as just discussed, is to weaken the grip of one's own framing of the situation in order to make room for alternative framings.

Minimally, a frame-sensitive reasoner must be able to appreciate that a single action or outcome can be apprehended from different perspectival frames. A useful analog from developmental psychology is visual perspective-taking, which has been studied as an aspect of how children develop mindreading skills, and in particular of how they come to understand the differences between how things appear and how they really are (Flavell, Reference Flavell1977; Flavell, Everett, Croft, & Flavell, Reference Flavell, Everett, Croft and Flavell1981). Flavell distinguishes two levels of visual perspective-taking.

• At the first level, young children have a very partial understanding of visual perspective. They understand the idea of a line of sight and of an object's being occluded or not occluded.

• At the second level, in contrast, children can understand that a single object can be seen differently from different perspectives (e.g., that a picture on a table in front of them will look upside-down to an experimenter sitting opposite them) (Masangkay et al., Reference Masangkay, McCluskey, McIntyre, Sims-Knight, Vaughn and Flavell1974; Moll & Meltzoff, Reference Moll and Meltzoff2011).

Frame-based reasoning engages skills analogous to second-level perspective-taking – understanding that things can look different to different people even when they have similar information, because they are operating within different frames. For that reason, the transition from frame-blind reasoning to frame-sensitive reasoning is analogous to the transition between first- and second-level perspective-taking.

6.3.3 Perspectival flexibility and the theory of role-taking

Selman's theory of role-taking is a useful starting-point for thinking about how frame-sensitive reasoners need to work simultaneously across two or more frames. Selman studied how children understand and react to social situations presented in short vignettes. After cross-sectional and longitudinal interviews (Gurucharri & Selman, Reference Gurucharri and Selman1982; Selman & Byrne, Reference Selman and Byrne1974), Selman and collaborators came up with a hierarchy of four levels of role-taking/perspective-taking. So, for example, at the age of 10–12 they suggest that children become capable of mutual role-taking, simultaneously considering their own perspective and that of another, while at the same time understanding that the other person can do the same. The highest level is social role-taking, which incorporates the perspectives of different social groupings.

However, even a normal and socially adept decision-maker capable of all these types of perspective-taking will still fall short of the type of perspective-taking that skilled frame-sensitive reasoning requires. Frame-sensitive reasoners must be able to operate simultaneously in multiple frames, not just be aware that issues and decision problems can be multiply framed.

A Selmanian role-taker can treat people with different perspectives and frames as fixed features of the world with which she has to negotiate and, if necessary, compromise, perhaps using strategies of principled negotiation and non-positional bargaining (e.g., depersonalize the situation; base agreement on objective criteria, etc., as proposed in Fisher & Ury [Reference Fisher and Ury1981]). But things are very different in an example of discursive deadlock like that between, say, pro-choice and pro-life legislators trying to come to terms on regulation for abortion clinics. The decision problem is too closely bound up with participants' deepest values and sense of their own identity for depersonalizing it to be a realistic instruction. And each participant's sense of what are going to count as objective criteria is determined by their frame.

So, to tackle discursive deadlock it is not enough for a frame-sensitive reasoner simply to understand that a particular action or outcome can be framed in multiple ways. She needs to frame it herself in multiple ways simultaneously, and the mechanisms by which this might take place are ripe for further study. Perhaps the process is not strictly speaking simultaneous but better understood as switching very quickly from one frame to another, because of the bandwidth issues discussed in Chater (Reference Chater2018) and revealed by well-known inattentional blindness phenomena (Mack & Rock, Reference Mack and Rock1998).

It is at this point that rational framing effects can enter the picture. Different ways of framing, say, restrictions on gun ownership, are associated with different preferences. For that reason, someone who internalizes the competing frames that give rise to discursive deadlock will often end up with quasi-cyclical preferences. Even if I know that “gun control” and “gun safety” are different ways of framing legal restrictions on gun ownership, properly internalizing those different frames requires me simultaneously to prefer, say, individual freedom from interference to gun control, but gun safety to individual freedom from interference.

6.3.4 Reason construction

A rational choice is a choice based on a rational preference, and a rational preference is grounded in a reason. So, how does a rational frame-sensitive reasoner extract reasons from frames? First by understanding the perspectival nature of individual frames – extracting the values they express, and the emotions that drive them. And then by extracting reasons from the frames and making comparisons within and across frames.

Frames are often embedded in narratives, which are themselves constructed in particular ways (see, e.g., Schiller [Reference Schiller2019] on narratives in economics). Those narratives can be reason-giving. For example, the construction of a pipeline (the Keystone Pipeline, e.g., or the Trans Mountain Pipeline) can be embedded in multiple different narratives. On one narrative the pipeline might be framed as part of a steady evolution toward energy independence and freedom from dependence on Middle Eastern oil. On another, the pipeline is a further step in raising standards of living by creating jobs and lowering fuel prices. A third narrative might see the pipeline as another step in the lengthy process of dispossessing Native American peoples of their land and heritage, while on a fourth narrative the pipeline is a further increase in environmental damage and environmental risk. Each of these narratives brings with it a different set of reasons.

Here, as before, a reasoner who has succeeded in internalizing multiple narratives, and the corresponding reasons, can easily find themselves with quasi-cyclical preferences. So, for example, I might prefer energy-independence to dependence on Middle Eastern oil, while at the same preferring safeguarding the environment to running the risk of environmental catastrophe. I know, of course, that choosing to safeguard the environment is choosing not to reduce dependence on Middle Eastern oil.

7. Conclusion

The orthodox view in the cognitive and behavioral sciences is that all framing effects are irrational. This paper has argued against the orthodox view, proposing to shift the debate away from the experimentally induced framing effects familiar from the “rationality wars” and toward more complicated situations where agents and decision-makers are well aware that they are framing a single action or outcome in different ways. Such situations can give rise to quasi-cyclical preferences (where A is preferred to B under one frame, but B preferred to A when one or both is framed differently). The paper has provided support from across the social, cognitive, and behavioral sciences for three hypotheses:

(H1) Frames and framing factor into decision-making by one dimension/attribute/value of the decision problem highly salient, thereby driving a particular response.

(H2) Framing effects associated with quasi-cyclical preferences are likely to be found in decision problems that are sufficiently complex and multi-faceted that they cannot be subsumed under a single dimension/attribute/value. What happens is that different frames prime different responses. The decision-maker is aware of this without being able to resolve the conflict either by ignoring one frame or by subsuming them both under a higher, overarching frame.

(H3) Framing effects and quasi-cyclical preferences will be rational in circumstances where it is rational to have a complex and multi-faceted response to a complex and multi-faceted situation.

In addition to shedding light on the three focus areas of self-control, game theory, and discursive deadlock, I hope in this paper to have shaken the grip of purely extensional approaches to reasoning and rationality.

Financial support

This work was supported by the American Council for Learned Societies (Fellowship 2018–2019); the National Endowment for the Humanities (Summer Stipend 2018); and the Philosophy and Psychology of Self-Control Project at Florida State University, funded by the Templeton Foundation.

Conflict of interest

None.

Target article

Rational framing effects: A multidisciplinary case

Related commentaries (27)

Ceteris paribus preferences, rational farming effects, and the extensionality principle

A reputational perspective on rational framing effects

Biases and suboptimal choice by animals suggest that framing effects may be ubiquitous

Competing reasons, incomplete preferences, and framing effects

Consistent preferences, conflicting reasons, and rational evaluations

Defining preferences over framed outcomes does not secure agents' rationality

Distinguishing self-involving from self-serving choices in framing effects

Even simple framing effects are rational

Explaining bias with bias

Four frames and a funeral: Commentary on Bermúdez (2022)

Frames, trade-offs, and perspectives

Framing is a motivated process

Framing provides reasons

Framing, equivalence, and rational inference

Incomplete preferences and rational framing effects

Probably, approximately useful frames of mind: A quasi-algorithmic approach

Quasi-cyclical preferences in the ethics of Plato, Aristotle, and Kant

Rational framing effects and morally valid reasons