Does the study of the mind's inner life provide a theoretical foundation for a science of art? Scientists in empirical aesthetics and neuroaesthetics think so. They adhere to what we, along with Pickford (Reference Pickford1972), call the psychological approach to art, which uses methods of psychology and neuroscience to study art and its appreciation. Because of its focus on the mind's processes and the brain's internal structures, psychological research often ignores the historical approach to art, which focuses on the role of historical contexts in the making and appreciation of works of art. The psychological and historical approaches have developed conflicting research programs in the study of art appreciation and of art in general. They offer diverging accounts of the degree to which historical knowledge is involved in art appreciation. After introducing the debate between these two traditions, we propose in sections 2 and 3 a psycho-historical framework that unifies psychological and historical inquiries into art appreciation. We argue that art-historical contexts, which encompass historical events, artists' actions, and mental processes, leave causal information in each work of art. The processing of this information by human appreciators Footnote 1 includes at least three distinct modes of art appreciation: basic exposure of appreciators to the work; causal reasoning resulting from an “artistic design stance”; and artistic understanding of the work based on knowledge of the art-historical context. In section 4, we demonstrate that empirical research within the framework is feasible. Finally, we describe in section 5 how an existing psychological theory, the processing-fluency theory of aesthetic pleasure, can be combined with the psycho-historical framework to examine how appreciation depends on context-specific manipulations of fluency.

1. The controversial quest for a science of art appreciation

The quest for an empirical foundation for the science of art appreciation has raised controversies across the humanities and the cognitive and social sciences. Although the psychological and historical approaches are equally relevant to a science of art, they have developed independently and continue to lack common core principles.

1.1. The psychological approach to art appreciation

The psychological approach to art aims to analyze the mental and neural processes involved in the production and appreciation of artworks. Early work by psychologists focused on how physiology and psychology may contribute to a scientific approach to aesthetic and artistic preferences (Bullough Reference Bullough1957; Fechner Reference Fechner1876; Helmholtz Reference Helmholtz1863; Martin Reference Martin1906; Pratt Reference Pratt1961). The field of empirical aesthetics originates from this tradition (Berlyne Reference Berlyne1971; Martindale Reference Martindale1984; Reference Martindale1990; Pickford Reference Pickford1972; Shimamura & Palmer Reference Shimamura and Palmer2012).

Research in neuroaesthetics is a recent and more radical branch of the psychological approach (Chatterjee Reference Chatterjee2011a; Skov & Vartanian Reference Skov and Vartanian2009). The term neuroaesthetics was coined by Zeki, who viewed it as “a neurology of aesthetics” that provides “an understanding of the biological basis of aesthetic experience” (Zeki 1999, p. 2). With regard to the relation to art history, research in the psychology of art does not essentially differ from neuroaesthetics. Like neuroscientists, psychologists think that the appreciation of art depends on internal mechanisms that reflect the cognitive architecture of the human mind (Kreitler & Kreitler Reference Kreitler and Kreitler1972; Leder et al. Reference Leder, Belke, Oeberst and Augustin2004) or of the mind's components such as vision (Solso Reference Solso1994; Zeki 1999) and auditory processing (Peretz Reference Peretz2006; Peretz & Coltheart Reference Peretz and Coltheart2003). Like neuroscientists, psychologists present artworks as “stimuli” in their experiments (Locher Reference Locher, Shimamura and Palmer2012). Their methodologies usually differ in that neuroscientists measure brain activation, whereas psychologists analyze behavioral responses. Both traditions are, however, dominated by the psychological approach understood as an attempt to analyze the mental and neural processes involved in the appreciation of artworks.

Many contemporary thinkers distinguish art appreciation from aesthetic experience broadly understood (Berlyne Reference Berlyne1971; Danto Reference Danto1974; Reference Danto2003; S. Davies Reference Davies2006a; Goodman Reference Goodman1968; Norman Reference Norman1988; Tooby & Cosmides Reference Tooby and Cosmides2001). In contrast to them, advocates of neuroaesthetics maintain that art “obeys” the aesthetic “laws of the brain” (Zeki 1999; Zeki & Lamb Reference Zeki and Lamb1994). Like evolutionary accounts of art (Dutton Reference Dutton, Gaut and Lopes2005; Reference Dutton2009; Pinker Reference Pinker2002; Tooby & Cosmides Reference Tooby and Cosmides2001), their research is aimed at discovering principles that explain both aesthetic and artistic universals. For example, drawing a comparison with the concept of universal grammar (Chomsky Reference Chomsky1966), Ramachandran (Reference Ramachandran2001, p. 11; Ramachandran & Hirstein 1999) defends the universalistic hypothesis that “deep” neurobiological laws cause aesthetic preferences and the appreciation of a work of art.

The search for laws (Martindale Reference Martindale1990) and universals of art is a chief objective for numerous contributions to the psychological approach (Aiken 1998; Dutton Reference Dutton, Gaut and Lopes2005; Fodor 1993, pp. 51–53; Peretz Reference Peretz2006; Pinker Reference Pinker1997, Ch. 8; 2002, Ch. 20; Zeki 1999). Among them, Dutton (Reference Dutton, Gaut and Lopes2005; Reference Dutton2009) and Pinker (Reference Pinker2002) argue that there are universal signatures of art, such as virtuosity, pleasure, style, creativity, special focus, and imaginative experience. Pinker even defends the ostensibly ahistorical conjecture that “regardless of what lies behind our instincts for art, those instincts bestow it with a transcendence of time, place, and culture” (Pinker Reference Pinker2002, p. 408).

Many advocates of the quest for aesthetic or artistic universals distrust the historical methods employed in the humanities (Martindale Reference Martindale1990; Ramachandran Reference Ramachandran2001). Some, like Martindale (Reference Martindale1990), have claimed that psychological or neuroscientific methods can discover laws of art appreciation without investigating the appreciators' sensitivity Footnote 2 to particular art-historical contexts. In contrast to neuroaesthetics, we will argue that the science of art appreciation needs to investigate art appreciators' historical knowledge and integrate historical inquiry and the psychology of art. Our view is derived from contextualist principles introduced by the historical approach, which we discuss next.

1.2. Contextualism and the historical approach to art appreciation

In contrast to the universalism pervasive in the psychological tradition, many scholars advocate a historical approach to the study of art. We use the term historical approach to refer to accounts that appeal to appreciators' sensitivity to particular historical contexts and the evolution of such contexts in order to explain art appreciation. We include in the historical approach studies that examine art appreciation from the standpoint of the history of art (Gombrich Reference Gombrich1950/1951; Munro Reference Munro1968; Reference Munro1970; Panofsky Reference Panofsky1955; Roskill Reference Roskill1976/1989), the sociology of art-historical contexts (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Emanuel1992/1996; Hauser Reference Hauser1951; Heinich Reference Heinich and Leduc Browne1996b; Tanner Reference Tanner2003), and art criticism specific to historical situations (Danto Reference Danto1998a; Reference Danto2009; Foster Reference Foster2002; Fried Reference Fried1998; Greenberg Reference Greenberg1961). A philosophical tradition representative of the historical approach is aesthetic contextualism (Currie Reference Currie1989; Danto Reference Danto1964; 1981; Dickie Reference Dickie1984/1997; 2000; Dutton Reference Dutton1983; Walton Reference Walton1970). According to aesthetic contextualism, historical and societal contingencies play an essential role in the production of art and in the appreciation of particular artifacts as works of art (Davies Reference Davies2004; Gracyk Reference Gracyk, Davies, Higgins, Hopkins, Stecker and Cooper2009; Levinson Reference Levinson1990; Reference Levinson2007). A work of art is the outcome of the causal intervention of human agents, such as artists and curators, embedded in a historical context made of unique unrepeatable events and irreplaceable objects (Benjamin Reference Benjamin, Jennings, Doherty and Levin1936/2008; Bloom Reference Bloom2010). Contextualists investigate the consequences of this historical embeddedness to account for the identity, appreciation, understanding, and evaluation of works of art. They argue that contextual knowledge of artifacts and their context-specific functions are essential processes in art appreciation.

According to contextualism and the historical approach, the appreciation of an artwork requires that appreciators become sensitive to the art-historical context of this work, including its transmission over time. Because defenders of the psychological approach have usually investigated art appreciation without analyzing the appreciator's sensitivity to art-historical contexts, many contextualists (Currie Reference Currie and Levinson2003; Reference Currie2004; Dickie Reference Dickie and Carroll2000; Gombrich Reference Gombrich2000; Lopes Reference Lopes2002; Munro Reference Munro1951; Reference Munro1970) doubt that current psychological and neuroaesthetic theories succeed in explaining art appreciation. In our interpretation, a decisive contextualist objection can be outlined as follows:

-

1. The appreciator's competence in artistic appreciation of a work of art is an informed response to – or sensitivity to – the art-historical context of this work (see sect. 3).

-

2. Most psychological and neuroaesthetic theories do not explain the appreciator's sensitivity to the art-historical context of the work (see sects. 1 and 4).

-

3. Therefore, most psychological and neuroaesthetic theories do not explain the appreciator's artistic appreciation.

In sum, most psychological and neuroaesthetic theories fail to account for artistic appreciation because they lack a model that accounts for the contextual nature of art and of the appreciators' sensitivity to art-historical contexts. In contrast to such ahistorical theories, we will outline a contextualist model in sections 2 and 3.

The contextualist objection is sound when directed at studies that investigate the neural responses to art without a theory of the neural basis of the sensitivity to art-historical contexts, as in neuroaesthetics. Consider, for example, Andy Warhol's Brillo Soap Pads Boxes (1964, hereafter “Brillo Boxes”; Danto Reference Danto1992). This piece has aesthetic properties that are absent from regular Brillo boxes in a supermarket. Because these objects are visually indistinguishable, they are likely to elicit the same kind of activation in the visual brain areas of appreciators. The reference to neural responses in visual areas may identify necessary conditions for appreciation through basic exposure (sect. 3.1). However, the reference to visual processes does not explain the fact that the appreciators' artistic understanding of the work derives from their sensitivity to its art-historical context (sect 3.3). As contextualists such as Danto (1981; Reference Danto1992; Reference Danto2003) have argued persuasively, a work like Warhol's Brillo Boxes can be appreciated as art only if its audience is sensitive to certain historical facts. Here, facts of relevance are that Warhol adopted the reflective attitude of artists in his artworld, or that he rejected the separation between fine art and mass culture (Crane Reference Crane1989; Danto Reference Danto1992: pp. 154–55; 2003: p. 3; 2009: Ch. 3). Therefore, a neuroaesthetics of the neural responses to Warhol's Brillo Boxes must investigate the neural mechanisms that underlie the appreciators' sensitivity to facts in Warhol's art-historical context (Frigg & Howard Reference Frigg, Howard, Schellekens and Goldie2011). We do not know of any neuroscientific studies that have directly examined this question.

This is but one example of the disagreements between the proponents of the psychological and the historical approaches. Since the early attempts to explain art in scientific terms (Fechner Reference Fechner1876), controversies have been raging about ontological assumptions, methods, and objects of inquiry. As a result of these disagreements, psychologists and neuroscientists often ignore the concepts proposed by historical theories, such as aesthetic contextualism, sometimes simply because they originate from the “non-scientific” humanities (Martindale Reference Martindale1990; see sect. 4). Reciprocally, only a few art historians (Freedberg Reference Freedberg1989; Freedberg & Gallese Reference Freedberg and Gallese2007; Gombrich Reference Gombrich1960; Reference Gombrich1963; Reference Gombrich1979; Stafford Reference Stafford2007; Reference Stafford2011) and philosophers (Currie Reference Currie, Davies and Stone1995; Reference Currie2004; Dutton Reference Dutton2009; Kieran & Lopes Reference Kieran and Lopes2006; Lopes Reference Lopes1996; Reference Lopes2004; Nichols Reference Nichols2006; Robinson Reference Robinson1995; Reference Robinson2004; Reference Robinson2005; Scharfstein Reference Scharfstein2009; Schellekens & Goldie Reference Schellekens and Goldie2011) consider psychological findings when discussing art. The separation between psychological and historical approaches is an illustration of the so-called “two cultures” (Carroll Reference Carroll2004; Leavis Reference Leavis1962; McManus Reference McManus2006; Snow Reference Snow1959), the divide between the sciences and the humanities that our psycho-historical approach seeks to overcome.

2. A psycho-historical framework for the science of art appreciation

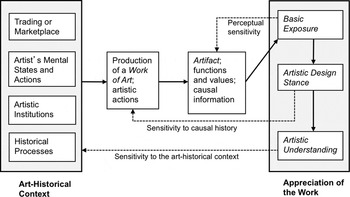

In sections 2 and 3, we introduce a psycho-historical framework for the science of art appreciation (“psycho-historical framework” henceforth). This framework expands Bullot's (2009a) research aimed at combining the psychological and historical approaches to a theory of art. Figure 1 represents the central concepts and relations identified by our framework, namely the concepts of art-historical context (sect. 2.1), the artwork as artifact (sect. 2.2) and as carrier of information (sect. 2.3), and the appreciation of the work through three modes of information processing (sect. 3).

Figure 1. The psycho-historical framework for the science of art appreciation. Solid arrows indicate relations of causal and historical generation. Dashed arrows indicate information-processing and representational states in the appreciator's mind that refer back to earlier historical stages in the production and transmission of a work. Details about the core concepts are provided in the text.

2.1. Art-historical context

As illustrated in Figure 1, art-historical contexts include persons, cultural influences, political events, and marketplaces governing the production, evaluation, trade, and conservation of works of art. Artists, patrons, curators, sellers, politicians, and audiences belong here. Contextualist philosophers (Danto Reference Danto1964; Dickie Reference Dickie1984/1997) investigate the ontological dependence of artworks on art-historical contexts (artworlds). Since at least Vasari (Reference Vasari, Conaway Bondanella and Bondanella1550/1991), art historians have examined art-historical contexts to understand the lives and oeuvres of artists (Guercio Reference Guercio2006). Others use sociological methods to explain trends or mechanisms, in particular art-historical contexts (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Nice1979/1987; Crane Reference Crane1989; Hauser Reference Hauser1951; Heinich Reference Heinich and Leduc Browne1996b).

Here, we do not aim to provide a detailed theory of the art-historical context. The psycho-historical framework only requires that researchers agree on two principles about the nature of the art-historical context: First, a work of art is an artifact that has historical functions (sect. 2.2). Second, it carries causal-historical information (sect. 2.3).

2.2. The work of art as artifact

We use the term artifact in a broad sense to refer to an object or a performance intentionally brought into existence through the causal intervention of human action and intentionality (e.g., Hilpinen Reference Hilpinen2004; Margolis & Laurence Reference Margolis and Laurence2007). This concept deviates from the sense of “artifact” that refers exclusively to manufactured objects. It entails that all artistic performances are artifacts in the sense of being products of human actions.

Artifacts usually have intended functions (Bloom Reference Bloom1996a; Dennett Reference Dennett1987; Reference Dennett1990; Millikan Reference Millikan1984; Munro Reference Munro1970). Arguably, the function of an artifact is initially specified by its inventor or designer. However, many artifacts acquire additional functions or have their main function abandoned over time. Therefore, reference to the intended function and original context is not sufficient to explain the functions of an artifact (Dennett Reference Dennett1990; Parsons & Carlson Reference Parsons and Carlson2008; Preston Reference Preston1998). Preston (Reference Preston1998) and Parsons and Carlson (Reference Parsons and Carlson2008, p. 75) propose a way to analyze the function of an artifact without exclusively relying on the intentions of its maker. In their analysis, artifacts of a particular sort have a proper function if these artifacts currently exist because their ancestors were successful in meeting some need or want in cultural and trade contexts because they performed this function, leading to production and distribution of artifacts of this sort.

Though alternative accounts of the relationships between artifacts and functions have been proposed (Grandy Reference Grandy, Margolis and Laurence2007; Sperber Reference Sperber, Margolis and Laurence2007; Vermaas & Houkes Reference Vermaas and Houkes2003), it is significant that all the proposed accounts need to refer to the historical context of artifacts to explain the way they acquire proper or accidental functions. Reference to particular historical contexts seems indispensable in explaining the functions of artifacts. It is therefore not surprising that cognitive development and adults' understanding of artifact concepts seems guided by a historical understanding of objects (Gutheil et al. Reference Gutheil, Bloom, Valderrama and Freedman2004).

With Parsons and Carlson (Reference Parsons and Carlson2008) and in agreement with empirical research on artifact cognition (e.g., Matan & Carey Reference Matan and Carey2001; see sect. 3.2), we propose to apply this historical approach to artifact functions to works of art (understood in the broad sense that refers to both art objects and performances). Because an artwork is a product of human agency with context-dependent functions, assessing the appreciators' understanding of its context-dependent functions is essential to explaining art appreciation (sect. 3.3). This premise underlies contextualism (sect. 1.2) and a few intentionalist theories of art in art history (Baxandall Reference Baxandall1985), anthropology (Gell Reference Gell1998), philosophy (Levinson Reference Levinson2002; Livingston Reference Livingston and Levinson2003; Rollins Reference Rollins2004; Wollheim Reference Wollheim1980), and psychology (Bloom Reference Bloom2004; Reference Bloom2010).

2.3. The work as carrier of information

In contrast to ahistorical psychologism, contextualism entails that explaining the appreciator's sensitivity to art-historical contexts is crucial to any account of art appreciation. We argue that this antagonism can be overcome if psychological and neuroscientific theories consider whether art appreciation depends on the processing of causal and historical information carried by an artwork, especially information related to its context of production and transmission.

Like Berlyne (Reference Berlyne1974), we adopt an information-theoretic conception of the work of art and its properties; and thus we assume that features of an artwork can be sources of syntactic, cultural, expressive, and semantic information. However, Berlyne's account is misleading because it is ahistorical. It overlooks the facts that the information carried by a work is the end product of a causal history and that appreciators extract information to acquire knowledge about the past of the work. We use the term causal information (Bullot Reference Bullot, Terzis and Arp2011; Dretske Reference Dretske1988; Godfrey-Smith & Sterelny Reference Godfrey-Smith and Sterelny2007; “natural meaning” in Grice Reference Grice1957; Millikan Reference Millikan2004: p. 33) to denote objective and observer-independent causal relations or causal data. A familiar example used to introduce causal information is tree-ring dating. In some tree species, one can draw inferences about age and growth history of a tree specimen from the number and width of its tree rings because ring-related facts carry causal information about growth-related facts (Speer Reference Speer2010). In a similar way, features in artworks are carriers of causal information and therefore allow appreciators to acquire knowledge about facts from the past.

As depicted in Figure 1, any work of art carries causal information. This phenomenon can be illustrated by the slashed paintings made by Lucio Fontana (Freedberg & Gallese Reference Freedberg and Gallese2007; Whitfield Reference Whitfield2000). The fact that there is a cut in the canvas of this painting by Fontana is evidence of the elapsed fact that Fontana is slashing the canvas because the former carries information about the causation of the latter. Knowledge of the causal link between the two facts is essential to authenticate that the work was made by Fontana and is not an act of vandalism or a forgery (sect. 3.3). Similarly, music or dance performances and works of poetry carry causal information. For example, the actions of dancers performing choreographies by Pina Bausch carry information about the decisions made by the choreographer while planning the performance.

It is often possible to retrieve from an artwork its connections to antecedent events because certain causal or lawful processes at the time of its creation or transmission preserve certain properties (e.g., Fontana's slashing the canvas with a knife caused the cut in the canvas, and this cut was preserved over time). A work also carries information about events after its initial production, like the translation of a poem written in Middle English into Modern English, or Mendelssohn's decisions in his performance of Bach's St. Matthew Passion in 1829 (Haskell Reference Haskell1996). Crucially, one can study such causal information in each particular artifact to infer its history, as illustrated above with the example of tree rings.

The historical study of artifacts always requires investigation into causal information to resolve a problem of reverse engineering (Chikofsky & Cross Reference Chikofsky and Cross1990; Rekoff Reference Rekoff1985) in the interpretation of causal information: How can one infer the properties of an object's history or the intentions of the producer from the features one perceives in the object? In the specific case of artworks, we will argue that this problem can only be resolved when one adopts the “artistic design stance” (sect. 3.2).

Although the features of artworks can be the outcome of deliberate actions performed by an intentional agent, such as Fontana or Bausch, much of the causal information carried by a work is the outcome of processes that are not products of intentional actions. For example, Pollock intentionally made his movements in order to cast paint on the canvas of Number 14: Gray in specific patterns. The time and effort he invested in planning and performing his seemingly accidental paintings contributed to the making of his artistic stature (Kruger et al. Reference Kruger, Wirtz, Van Boven and Altermatt2004; Steinberg Reference Steinberg1955). However, the distribution of paint in his painting also carries causal information (causal data) derived from physical or physiological constraints that led to outcomes not intentionally planned by Pollock.

Causal-historical information is fundamental to the unification of the psychological and historical approach because it is the missing link between the history of an artwork and its appreciation (Bullot Reference Bullot2009a). This linkage has been overlooked by most theories in the two traditions.

2.4. The neglect of art-historical contexts by psychology

Some proponents of the psychological approach (Fodor 1993; Ramachandran Reference Ramachandran2001) claim that sensitivity to art-historical contexts is not a requisite of art appreciation and art understanding (see sect. 1.1). Other advocates of the psychological approach do not explicitly deny the historical nature of the artistic context and of artistic actions. However, they usually do not offer proper theoretical and methodological consideration of the role of the appreciator's knowledge of art-historical contexts (sect. 4).Footnote 3

This oversight of the sensitivity to art-historical contexts persists despite research demonstrating the role of causal-historical knowledge and essentialist assumptions in the categorization of artifacts (Bloom Reference Bloom1996a; Reference Bloom2004; Reference Bloom2010; Kelemen & Carey Reference Kelemen, Carey, Margolis and Laurence2007; Newman & Bloom Reference Newman and Bloom2012), and despite the greater importance experts give to historical contexts in art appraisal compared with novices (Csikszentmihalyi & Robinson Reference Csikszentmihalyi and Robinson1990; Parsons Reference Parsons1987). Some of the most radical historicists (Gopnik Reference Gopnik, Shimamura and Palmer2012; Margolis Reference Margolis and Fisher1980; Reference Margolis and Carroll2000) have concluded from this oversight that psychological research is irrelevant in principle to the theory of art appreciation. To rebut these objections, psychological theories must address the contextualist objections and examine the links between art-historical context and appreciation of an artwork.

3. Three modes of art appreciation

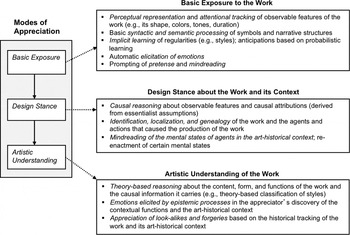

A work of art carries causal information about art-historical contexts. When appreciators perceive a work, they are exposed to such causal-historical information. This exposure may lead appreciators to develop their sensitivity to related art-historical contexts and deepen their understanding of the making, authorship, content, and functions of the work. Appreciators of a work can process the information it carries in at least three distinct ways (see boxes and dashed arrows on the right-hand side of Fig. 1), through three modes of art appreciation (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. The three modes of appreciation of a work of art posited by the psycho-historical framework. Solid arrows depict necessary conditions. Dashed arrows specify typical mental activities elicited by each mode.

First, appreciators can extract information about the work by drawing their attention to its observable features in basic exposure (sect. 3.1). Second, once exposed to an artwork, appreciators may adopt the artistic design stance, which triggers interpretations of the causal information carried by the work (sect. 3.2). Taking the design stance enables appreciators to acquire artistic understanding derived from knowledge of the art-historical context (sect. 3.3). As depicted by the solid arrows in Figure 2, exposure to a work is a necessary condition for adopting the artistic design stance, and taking the design stance is necessary for artistic understanding.

3.1. Basic exposure

An elementary mode of appreciation is basic exposure to the work or one of its reproductions. Basic exposure is the set of mental processes triggered by perceptual exploration of an artwork without knowledge about its causal history and art-historical context. Perceptual exploration employs a variety of processes necessary to appreciation that we will not discuss here (Fig. 2).Footnote 4 Instead, we outline basic principles and focus on three processes that play a key role in our justification of the psycho-historical framework: the implicit learning of regularities, the elicitation of emotions, and pretense. Such processes may elicit cognitive analysis of artwork content and aesthetic pleasures. But they do not provide appreciators with explicit knowledge of the links between the work and its original art-historical context.

3.1.1. Implicit learning of regularities and expectations

Because artworks carry causal-historical information, repeated exposure to a work may nonetheless allow its appreciators to implicitly develop their sensitivity to historical facts or rules, even if such appreciators are deprived of knowledge about the original art-historical context. For example, exposure to musical works leads listeners without formal expertise in music to acquire an ability for perceiving sophisticated properties such as the relationships between a theme and its variations, musical tensions and relaxations, or the emotional content of a piece (Bigand & Poulin-Charronnat Reference Bigand and Poulin-Charronnat2006).

Perceptual exposure to an artwork leads to types of implicit learning that may occur even if the learner does not possess any explicit knowledge about the history of the work. Consider style. Stylistic traits indicative of a particular artist, school, or period are important features of artworks that connect form and function (Carroll Reference Carroll1999, Ch. 3; Goodman Reference Goodman1978, Ch. 2). The classification of artworks according to their style is an important skill in art expertise (Leder et al. Reference Leder, Belke, Oeberst and Augustin2004; Munro Reference Munro1970; Wölfflin Reference Wölfflin and Hottinger1920/1950). Machotka (Reference Machotka1966) and Gardner (Reference Gardner1970) observed that young children classify paintings according to the represented content, whereas older children begin to classify paintings according to style. However, there is reason to doubt that artistic understanding is a requisite of basic stylistic classifications; one study suggested that even pigeons can learn to classify artworks according to stylistic features (Watanabe et al. Reference Watanabe, Sakamoto and Wakita1995), and we do not know of any evidence for artistic understanding in pigeons. This indicates that basic style discrimination stems from probabilistic learning that does not require an understanding of the processes that underlie styles of individual artists (Goodman Reference Goodman1978) or historical schools and periods (Arnheim Reference Arnheim1981; Munro Reference Munro1970; Panofsky Reference Panofsky1995; Wölfflin Reference Wölfflin and Hottinger1920/1950). Such understanding is more likely to derive from inferences based on historical theories rather than on similarity (sect. 3.3).

3.1.2. Automatic elicitation of emotions

The sensory exposure to form and content of a work of art can elicit a variety of automatic emotional responses (Ducasse Reference Ducasse1964; Peretz Reference Peretz2006; Robinson Reference Robinson1995; Reference Robinson2005). These may include the emotions that are sometimes described as basic (Ekman Reference Ekman1992) or primary (Damasio Reference Damasio1994) – such as anger, fear (Ledoux Reference LeDoux1996; Walton Reference Walton1978), disgust, and sadness – and other basic responses such as startle (Robinson Reference Robinson1995), erotic desire (Freedberg Reference Freedberg1989), enjoyment, or feeling of empathetic engagement (Freedberg & Gallese Reference Freedberg and Gallese2007). The historical knowledge that appreciators gain from the elicitation of these basic emotions by means of basic exposure to a work is shallow at best.

3.1.3. Prompting of pretense and mindreading

The appreciator's perception of the work can prompt processes aimed at representing mental states, so-called mindreading (Carruthers Reference Carruthers2009; Nichols & Stich Reference Nichols and Stich2003). Most empirical evidence about mindreading comes from research on child development (Bartsch & Wellman Reference Bartsch and Wellman1995; Wellman Reference Wellman1990) and cognitive evolution (Premack & Woodruff Reference Premack and Woodruff1978; Sterelny Reference Sterelny2003; Whiten & Byrne Reference Whiten and Byrne1997). To our knowledge, mindreading in art appreciation has not been an object of research in empirical aesthetics and neuroaesthetics. In contrast, philosophical arguments by Walton (Reference Walton1990), Currie (Reference Currie1990; Reference Currie, Davies and Stone1995), Schaeffer (Reference Schaeffer1999), Gendler (Reference Gendler2000; Reference Gendler2006), and Nichols (Reference Nichols2006) provide reason to think that mindreading and imagination are essential to art appreciation. For a work of art can prompt free imaginative games and pretense involving the attribution of fictional beliefs or desires to characters. These games often are stunning constructions of imagination (Harris Reference Harris2000; Nichols & Stich Reference Nichols and Stich2003) and need no sensitivity to the causal history of artworks.

When watching fictitious battle scenes in an antiwar movie, viewers ignorant of its intended antiwar function may imagine themselves as military heroes and enact pretend-plays that ascribe pretend military-functions to objects (e.g., pretend that a cane has the function of a gun). These appreciators may experience imaginative contagion, the phenomenon that imagined content may facilitate thoughts and behaviors, here pretend-plays (Gendler Reference Gendler2006). The viewers are exposed to the movie, discriminate between fictional worlds (Skolnick & Bloom Reference Skolnick, Bloom and Nichols2006), ascribe fictional intentions to their enemies, experience fear or “quasi-fear” (Meskin & Weinberg Reference Meskin and Weinberg2003; Walton Reference Walton1978), and do not conflate fiction and reality (Currie & Ravenscroft Reference Currie and Ravenscroft2003; Harris Reference Harris2000; Nichols & Stich Reference Nichols and Stich2003). However, their responses to the work are not sensitive to the original art-historical context because of their ignorance of the antiwar function originally intended. We therefore must distinguish the engagement of mindreading in basic exposure from its engagement in inquiries about art-historical contexts (sect. 3.2).

Basic exposure to artworks is the mode of appreciation most frequently studied by empirical aesthetics and neuroaesthetics. However, the contextualist objection (sect. 1.2) entails that research restricted to basic exposure cannot characterize processes of artistic understanding based on sensitivity to art-historical contexts and functions because a requisite of such an understanding is thinking about causal information carried by the artwork. For example, as explained in section 3.3, a theory of basic exposure cannot resolve the classic conundrum of the appreciation of look-alikes (Danto 1981; Rollins Reference Rollins1993) and forgeries (Bloom Reference Bloom2010; Dutton Reference Dutton1979; Reference Dutton1983). Contextual understanding of the causal history of a work requires adoption of the artistic design stance, which we discuss next.

3.2. The artistic design stance

Once exposed to a work, appreciators may investigate the production and transmission of the work understood as an individual exemplar (Bloom Reference Bloom2010, Ch. 4–5; Bullot Reference Bullot2009b; Rips et al. Reference Rips, Blok and Newman2006). Far from being historically shallow, this mode enables appreciators to become sensitive to the art-historical context of the work. Evidence from research on essentialism and the cognition of artifacts supports this hypothesis.

Research reviewed by Kelemen and Carey (Reference Kelemen, Carey, Margolis and Laurence2007) indicates that the understanding of artifact concepts by humans relies on the adoption of a “design stance” (Kelemen Reference Kelemen1999; Kelemen & Carey Reference Kelemen, Carey, Margolis and Laurence2007). Kelemen and Carey adopt the theory-theory of concepts (Carey Reference Carey1985; Gopnik & Meltzoff Reference Gopnik and Meltzoff1997; Gopnik & Wellman Reference Gopnik, Wellman, Hirschfeld and Gelman1994; Keil Reference Keil1989), which posits that development is best understood as the formulation of a succession of naïve theories. They combine this theory-theory with the hypothesis that humans adopt essentialism (Bloom Reference Bloom2010; Gelman Reference Gelman2003) when reasoning about natural kinds such as tiger, gold, or water (Boyd Reference Boyd1991; Griffiths Reference Griffiths and Wilson1999; Putnam Reference Putnam1975; Quine Reference Quine1969). Psychological essentialism is the view that human adults assume that natural kinds have causally deep, hidden properties that constitute their essence. These properties explain the existence of individual members of the kind, determine their surface or structural properties, and explain the way they behave while exposed to causal interactions with other entities.

Going beyond the use of theory-theory to study concepts of natural kinds (Keil Reference Keil1989; Quine Reference Quine1969), Kelemen and Carey (Reference Kelemen, Carey, Margolis and Laurence2007) argue that it applies to concepts of artifact too. They provide evidence that adults use a causal-explanatory scheme to acquire artifact concepts and to reason about the history of artifacts (e.g., Bloom Reference Bloom1996a; Reference Bloom1998; German & Johnson Reference German and Johnson2002; Matan & Carey Reference Matan and Carey2001). Their evidence suggests that artifact categorization is sensitive to the original function intended by the designer of an artifact. According to this psychological essentialism, the intended function of the artifact is its essence.

Humans adopt the design stance when they reason about artifacts and their functions. Because artworks are artifacts, humans are likely to adopt the design stance when they reason about works of art and understand their functions. Specifically, our proposal is that the artistic design stance involves at least three kinds of activities. First, appreciators begin adopting the design stance when they reason about the causal origins of the information carried by the work. Second, appreciators deploy this design stance if they elaborate hypotheses about the unique causal history or genealogy of the work, its functions, and the agents who produced it. Third, appreciators adopt a properly artistic design stance if they use their mindreading abilities to establish that the work was designed to meet artistic and cultural intentions within an art-historical context.

Although our analysis of the design stance is not expressed in the exact terms proposed by Kelemen and Carey (Reference Kelemen, Carey, Margolis and Laurence2007), we think that it is compatible with the principles of their proposal and the essentialist account of art and artifacts introduced by Bloom (Reference Bloom2004; Reference Bloom2010). We thus propose that, like detectives (Eco & Sebeok Reference Eco and Sebeok1983; Ginzburg Reference Ginzburg1979), appreciators adopt the artistic design stance when they use inferences – such as abductive inferences (Carruthers Reference Carruthers1992; Reference Carruthers2006a; Kelemen & Carey Reference Kelemen, Carey, Margolis and Laurence2007; Lipton Reference Lipton1991/2004; Lopes Reference Lopes2005, p. 136) – to process causal-historical information carried by artworks and discover facts about past art-historical contexts. Through this kind of processing, appreciators combine their autobiographical and contextual knowledge for tracking the history of the artwork or for interpreting the intentions of the artist.

3.2.1. Causal reasoning and causal attribution

Works of art carry diverse sorts of information, for example, about craftsmanship, style, and political allegiance. When an audience begins to infer from observable features of the work the causal history of unobserved actions that have led to these observable features, they begin to engage in the design stance. This claim is supported by the fact that humans spontaneously try to track down the cause of an event, especially if it is surprising or salient, a process that triggers causal reasoning (Gelman Reference Gelman2003, Ch. 5; Heider Reference Heider1958). Once appreciators engage in the design stance, this engagement triggers the search for what caused the features perceived in an artwork. Such a search for causal information in artworks is a requisite for artistic understanding.

3.2.2. Deciphering the causal history of a work

Once appreciators adopt the design stance, they start processing information carried by the artwork as causal and historical information. This stance enables them to address basic questions about the history of the work such as authorship attribution, dating, influence on the design, provenance, state of conservation, or reception. Appreciators need to decipher the causal history of the work, often by means of theory-based reasoning (Murphy & Medin Reference Murphy and Medin1985), to address such questions about unobservable states of affairs. For example, authentication and dating can be guided by the use of theories about the causal history of a work, such as Giovanni Morelli's theory of authentication (Morelli Reference Morelli and Richter1880/1893; Wollheim Reference Wollheim1974, pp. 177–201). Morelli claims that in order to decide authorship of paintings, it is necessary to study apparently insignificant details (e.g., rendering of ears, handwriting) that reveal the author's idiosyncrasies of handling and thus enable appreciators to individuate the unique style of an artist.

3.2.3. Mindreading of agents in the art-historical context

In addition to triggering causal attribution and tracking history, the design stance may also prompt mindreading (Baron-Cohen Reference Baron-Cohen1995; Nichols & Stich Reference Nichols and Stich2003) and an artistic intentional stance (Dennett Reference Dennett1987). In basic exposure, appreciators often use their mindreading abilities to engage in pretense without investigating its art-historical context (sect. 3.1). In contrast, the design stance leads appreciators to inquire into the mental states of important agents in the original art-historical context of the work (e.g., intentions of the artist or patron).

Appreciators may use simulation (Goldman Reference Goldman2006) or reasoning based on relevance and optimality (Dennett Reference Dennett1990; Sperber & Wilson Reference Sperber and Wilson2002) to interpret the intentions of agents in bygone art-historical contexts. For example, an appreciator may interpret an artist's intention as a state aimed at producing a work whose function is to cause a specific emotional or cognitive process in the appreciator's mind. Mindreading driven by the intentional stance can enable audiences to apprehend an artwork from the perspective of the artist (sect. 3.3). The audience may reason about the problem the artist tried to solve. In contrast to basic exposure, an appreciator who takes the design stance can imagine alternative solutions to the artistic problem and hence use counterfactual reasoning (Gendler Reference Gendler2010; Nichols & Stich Reference Nichols and Stich2003; Roese & Olson Reference Roese and Olson1995) for inferring how the artist might have solved it. This kind of mindreading is aimed at refining an appreciator's sensitivity to the causal history of the work and therefore enabling artistic understanding.

3.3. Artistic understanding

If appreciators take the design stance as a means to interpret a work, they will increase their sensitivity to and proficiency with the art-historical context and content of this work. This increase in proficiency enables appreciation of art based on understanding. Appreciators have artistic understanding of a work if art-historical knowledge acquired as an outcome of the design stance provides them with an ability to explain the artistic status or functions of the work. Given the variety of the processes involved in understanding (Keil Reference Keil2006; Keil & Wilson Reference Keil and Wilson2000; Ruben Reference Ruben1990), we need to carefully distinguish the variety of scientific and normative modes of artistic understanding.

The normative mode of artistic understanding aims to identify and evaluate the artistic merits of a work and, more generally, its value (Budd Reference Budd1995; Stecker Reference Stecker and Levinson2003). It is commonly based on contrastive explanations that compare the respective art-historical values of sets of artifacts. These evaluations are often viewed as essential to the practice of art critics (Beardsley Reference Beardsley1958/1981; Budd Reference Budd1995; Foster Reference Foster2002; Greenberg Reference Greenberg1961) and art historians (Gombrich Reference Gombrich1950/1951; Reference Gombrich2002). The scientific mode of artistic understanding aims not to provide normative assessments but to explain art appreciation with the methods and approaches discussed in the present article. In a way that parallels the combination of normative and scientific aspects in folk-psychology (Knobe Reference Knobe2010; Morton Reference Morton2003), the normative and scientific modes of understanding are often intermingled in commonsense thinking about art and scholarly writings about art (Berlyne Reference Berlyne1971, pp. 21–23; Munro Reference Munro1970; Roskill Reference Roskill1976/1989).

The normative mode is a traditional subject matter of philosophy. For example, Malcolm Budd (Reference Budd1995) derived from Hume's analysis of the standard of taste (Reference Hume, Copley and Edgar1757/1993) and Kant's aesthetics (Reference Kant, Guyer and Matthews1793/2000) a novel normative conception of artistic understanding (see also Levinson Reference Levinson1996; Rollins Reference Rollins2004). Budd characterizes artistic understanding as an assessment of the value and the function of a work, a task typically conducted in art criticism (1995, pp. 40–41). On his account, the artistic value of an artwork is determined by the intrinsic value of the experience it offers (1995, pp. 4, 40). By “experience the work offers,” Budd means an experience in which the work is adequately understood and its context-dependent and historical functions (sect. 2.2) and individual merits grasped for what they are. Such artistic understanding requires that appreciators become sensitive to the artistry, creativity, and achievement inherent in a work apprehended in its unique art-historical context of creation (Dutton Reference Dutton1974).

Two premises of the psycho-historical framework seem compatible with Budd's account. First, the appreciator's normative understanding of a work relies on the design stance to track the aspects of art-historical contexts that explain the value of the experience the work offers. Second, because the aesthetic functions, along with the cultural, political, or religious functions of works of art, are determined by historical contexts and lineages (G. Parsons & Carlson Reference Parsons and Carlson2008), sensitivity to art-historical contexts is a necessary condition to Budd's normative artistic understanding. In contrast to the psycho-historical account, however, Budd's analysis includes neither the scientific mode of understanding nor the psychological processes underlying (normative or scientific) understanding. In our framework, examples of psychological processes encompass theory-based reasoning about the functions or values of the work, emotions elicited by the appreciator's understanding of the art-historical context of a work, and differences in appraisal of indistinguishable artworks with distinct histories.

3.3.1. Theory-based reasoning

The appreciator's understanding of a work has to rely on naïve or scientific theories (Gopnik & Meltzoff Reference Gopnik and Meltzoff1997; Kelemen & Carey Reference Kelemen, Carey, Margolis and Laurence2007; Murphy & Medin Reference Murphy and Medin1985) and causal reasoning (Gopnik & Schulz Reference Gopnik and Schulz2007; Shultz Reference Shultz1982). Theories have characteristics such as conceptual coherence, power of generalization, and representations of causal structures (Gopnik & Meltzoff Reference Gopnik and Meltzoff1997). These characteristics enable users of art-related theories to make predictions, produce cognitively “rich” interpretations of an artwork, and generate abductive inferences (or inferences to the best explanation; see Carruthers Reference Carruthers, Carruthers, Stich and Siegal2002; Reference Carruthers2006a; Coltheart et al. Reference Coltheart, Menzies and Sutton2009; Lipton Reference Lipton1991/2004). Theories of the art-historical context are therefore necessary conditions for the appreciators' competence in reliably identifying and explaining key aesthetic properties such as authenticity, style, genre, and context-dependent meanings or functions.

Consider style. Basic exposure may lead appreciators to recognize artistic styles by means of probabilistic learning and similarity-based classification (sect. 3.1). Because such processing is shallow in respect of art history, appreciators can hardly come up with accurate explanations of the identification of styles and the assessment of their similarities. In contrast, appreciators who develop artistic understanding can use historical theories about the relevant art-historical context to identify styles more reliably. Theories are needed in this case because stylistic properties of individuals or schools are difficult to identify and often result in disagreements (Arnheim Reference Arnheim1981; Reference Arnheim1986; Goodman Reference Goodman1978; Lang Reference Lang1987; Walton Reference Walton and Lang1987; Wölfflin Reference Wölfflin and Hottinger1920/1950). Therefore, relevant identification of styles must appeal to theories of art-historical contexts that provide explanations for such classifications.

Theories of aspects of an art-historical context can also inform the appreciators' understanding of the mind of important intentional agents. This can be illustrated by the role of theories to inform simulations aimed at understanding the decisions made by an artist or attempting to reenact the artist's decision or experience (Croce Reference Croce and Ainslie1902/1909; Reference Croce and Ainslie1921).

Taking the design stance opens up the possibility of misunderstandings in art interpretation. Artistic misunderstandings may depend on fallacies or incorrect explanation of the relationships between the work and its art-historical context, and not just on errors in the processing of observable features of the artwork, as in basic exposure. For example, there is evidence that communicators tend to overestimate their effectiveness in conveying a message (Keysar & Barr Reference Keysar, Barr, Gilovich, Griffin and Kahneman2002). Likewise, some artists might overestimate the degree to which an audience is capable of understanding their intention. Similar biases in appreciators (Ross Reference Ross and Berkowitz1977) and cultural differences in causal attribution (Miller Reference Miller1984; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Nisbett, Peng, Sperber, Premack and Premack1995; Nisbett Reference Nisbett2003) may result in causal reasoning on the side of the audience that leads to misunderstandings in art appraisal.

3.3.2. Causal reasoning and emotions

Inferences about the causes of an artwork are epistemic processes, and epistemic processes can trigger emotions (Hookway Reference Hookway, Carruthers, Stich and Siegal2002; Thagard Reference Thagard, Carruthers, Stich and Siegal2002). Though emotions are often elicited by basic exposure to an artwork (sect. 3.1; Carruthers Reference Carruthers and Nichols2006b; Harris Reference Harris2000, Ch. 4; Juslin & Västfjäll Reference Juslin and Västfjäll2008; Silvia Reference Silvia2009), appreciators may experience different types of emotions in the mode of artistic understanding. The quality of the emotions and feelings elicited by an artwork may depend on causal attribution.

A study on helping behavior of bystanders illustrates this point (Piliavin et al. Reference Piliavin, Rodin and Piliavin1969). The authors found that helping depended on the attribution of the cause of an emergency, such as handicap versus drunkenness, and the effect of causal attributions on helping behavior was mediated by emotions, such as anger and pity (Reisenzein Reference Reisenzein1986; Weiner Reference Weiner1980). Transferred to art appreciation, these findings suggest that the same artwork may elicit different emotions, depending on the attributions the audience makes. For example, Manet's paintings that glorified bullfighting (Wilson Bareau Reference Wilson Bareau2001) are certainly seen from a different perspective by most contemporary audiences and elicit emotions far from glorifying bullfighting. However, appreciators may take the perspective of an admirer of bullfighting and appreciate these paintings as intended in their original context.Footnote 5 If findings on causal attributions and emotions in the context of helping behavior could be transferred to art appreciation, it would mean that the design stance, compared with basic exposure, would result in improved artistic understanding because different causal inferences may result in the experience of different emotional qualities.

This analysis can be contrasted with a suggestion made by Fodor (1993). To rebut theories of art appreciation that stress the role of historical expertise like Danto's or Dickie's contextualist theories, Fodor conjectures that appreciators can adequately interpret a work of art without knowing its intentional-causal history, simply by imagining a fictitious causal history (a “virtual etiology”) and fictitious art-historical contexts. In contrast to Fodor's hypothesis, the psycho-historical framework predicts that virtual etiologies based on arbitrary premises would result in deficient artistic understanding because they do not track the actual causal history. Appreciations based on fictitious causal histories are likely to lead to mistakes in artistic understanding, unless the appreciators' use of a fictitious causal history plays the role of a thought experiment (Gendler Reference Gendler2004; Gendler & Hawthorne Reference Gendler and Hawthorne2002) and helps them track real artistic properties and art-historical contexts.

Theories of expression in art (Collingwood Reference Collingwood1938; Reference Collingwood1946; Robinson Reference Robinson2005) tend to agree with these predictions of the psycho-historical framework, because such theories entail that understanding the way a work expresses a particular content cannot be achieved without some understanding of its actual (rather than virtual) history and psychological effects.Footnote 6

In the realm of everyday behavior, Elias (Reference Elias1939/1969) has shown that the triggers of certain emotions can be specific to a particular period of history. The above-mentioned paintings of bullfighting by Manet support this phenomenon for the realm of art. Elias's work and the example from Manet illustrate the point that the cognitive architecture of mental and brain processes underlying the experience of emotions probably remained the same in written history and may be seen as a universal; however, the triggers of emotions may have changed and are therefore an object of historical inquiry. To understand an artwork that was intended to convey an emotion, appreciators have to know what triggered an emotion at the time of the production of a work and may attempt to reproduce the same kind of response.

3.3.3. The appreciation of look-alikes and forgeries

Consider the classic conundrums of artistic appreciation of look-alikes (Danto 1981) or forgeries (Dutton Reference Dutton1979; Stalnaker Reference Stalnaker, Gaut and Lopes2005) and of the attribution of authorship (Ginzburg Reference Ginzburg1979; Morelli Reference Morelli and Richter1880/1893; Vasari Reference Vasari, Conaway Bondanella and Bondanella1550/1991; Wollheim Reference Wollheim1974). If art were appreciated only at the level of basic exposure, and thus without causal understanding, two artworks that look alike – as in Danto's red squares (1981, pp. 1–5) and other indiscernibles (Wollheim Reference Wollheim and Rollins1993) – would elicit equivalent responses in appreciation. Thus, Brillo Boxes made by Warhol (Danto Reference Danto2009) would elicit equivalent appraisal as the stacks of Brillo boxes in supermarkets. However, analysis of the artistic appreciation of look-alikes (Danto 1981) and historical records of responses to the discovery of forgeries (Arnau Reference Arnau1961; Godley Reference Godley1951; Werness Reference Werness and Dutton1983) contradict the prediction of an equivalent appraisal of look-alikes.

Appreciators value look-alikes differently once they understand that the look-alikes have different causal history. First, this view is supported by the well-documented ubiquity of essentialism in human cognition because psychological essentialism leads people to search for hidden causes and therefore go beyond the similar appearances of look-alikes (Bloom Reference Bloom2010, Ch. 4–5). Second, it is supported by conceptual research (Bullot Reference Bullot2009b; Evans Reference Evans1982; Jeshion Reference Jeshion2010) and empirical evidence (Rips et al. Reference Rips, Blok and Newman2006) demonstrating the ubiquity in human adult cognition of the ability to track individuals as unique exemplars. Hood and Bloom (Reference Hood and Bloom2008) provided evidence that the interest in the historical discrimination of look-alikes is present even in children, who preferred an object (a cup or a spoon) that had belonged to Queen Elizabeth II to an exact replica. This preference for originals compared to replica or forgeries is inexplicable by a psychological approach that considers only basic exposure such as Locher's (2012) account.

The discovery that works allegedly painted by Vermeer (Bredius Reference Bredius1937) were in fact fabricated by van Meegeren (Coremans Reference Coremans1949) has led their audience to reassess their artistic value precisely because the causal history of the works and their relations to their maker and art-historical context matter to their artistic value. Van Meegeren's forgeries are profoundly misleading when they are taken to be material evidence of Vermeer's past action and artistry. Our psycho-historical framework suggests that appreciators dislike being misled by artistic forgeries precisely because forgeries undermine their historical understanding of artworks and their grasp of the correct intentional and causal history.Footnote 7

3.4. Recapitulation

The psycho-historical framework posits that there are at least three modes of appreciation and suggests testable empirical hypotheses for each mode. According to the core hypothesis, appreciators' responses to artworks vary as a function of their sensitivity to relevant art-historical contexts. This account contradicts the claim that sensitivity to art-historical contexts is not a requisite of art appreciation and art understanding (sect. 1.1 and 2.4). Our objections to the universalist claims that deny the historical character of art appreciation does not entail a radical form of cultural relativism, which would view scientific research on art appreciation impossible in principle because of its historical variability. In contrast to anti-scientific relativism, research on artifact cognition and essentialism (sect. 3.2) demonstrates that contextual variables moderate the effects of mental processes in ways that can be investigated empirically.

We suggested that basic exposure is a requisite for adopting the design stance, which is in turn a requisite for artistic understanding (Figure 2). Parsons (Reference Parsons1987) provided a framework that lends support for this claim. His account of the development of understanding representational painting – from the stage of novices to expertise – seems to reflect the modes of art appreciation presented here. In the first two stages of this development, viewers do not go beyond the characteristics seen in the picture. The appreciators' interest in the meaning of the artwork and its connection to a culture and art history emerges only in the later stages.

Our claim that artistic understanding depends on adopting the design stance and adopting the design stance on basic exposure does not entail that appreciators' processing follows the three stages in a rigid order. Experts might have an ability to summon historical information very rapidly by means of fast recognition of task-relevant patterns (Chase & Simon Reference Chase and Simon1973; Pylyshyn Reference Pylyshyn1999, pp. 358–59) and attention routines (Ullman Reference Ullman1984) controlled by causal reasoning elicited by the design stance. Although we are lacking direct empirical evidence to adjudicate these hypotheses applied to art appreciation, findings from basic cognitive phenomena like top-down processing in understanding events (Zacks & Tversky Reference Zacks and Tversky2001) and stories (Anderson & Pearson Reference Anderson, Pearson, Barr, Kamil and Mosenthal1984; Kintsch Reference Kintsch1998; Reference Kintsch2005; Schank Reference Schank1990; Reference Schank1999) indirectly suggest that searching for causal information and employing knowledge about art history should influence the interpretation of a painting from the very first moment one is exposed to it.

The main prediction – that responses to artworks vary as a function of appreciators' sensitivity to art-historical contexts – receives preliminary support from the fact that experts often differ from novices in their evaluation of visual (e.g., McWhinnie Reference McWhinnie1968) or musical stimuli (e.g., Smith & Melara Reference Smith and Melara1990). The difference might be explained by the fact that art experts are more likely to adopt the design stance and be proficient in art and its history than novices. However, this explanation awaits further research to corroborate that the effect of expertise on evaluation of artworks is mediated by these two modes of appreciation. To develop such research and address these questions, empirical aesthetics and neuroaesthetics have to conduct their research within the psycho-historical framework.

4. Empirical aesthetics, neuroaesthetics, and the psycho-historical framework

Most research in empirical aesthetics disregards the theoretical consequences of historical and contextualist approaches to art (sect. 1 and 3.4). Researchers in empirical aesthetics rarely discuss what is unique to art appreciation in comparison to the appreciation or use of other kinds of artifacts, often assuming that using works of art as stimuli is sufficient to study art appreciation. We argue that this narrow approach cannot succeed because it is incomplete. The psycho-historical framework suggests two additional requirements for productive experimental research on art appreciation: First, researchers have to consider sensitivity to art-historical contexts when they choose the independent variables in their studies. Second, instead of focusing exclusively on mental processes related to basic exposure, investigators might instead measure dependent variables that track processes specific to other modes of appreciations, such as adoption of the design stance and acquisition of context-sensitive artistic understanding.

4.1. Independent variables and art-historical contexts

Adopting a method introduced by Fechner (Reference Fechner1876; see also Martin Reference Martin1906; Pickford Reference Pickford1972; Ch. 2), some studies in empirical aesthetics use simplified stimuli, such as geometrical patterns, to examine the influence of perceptual variables on aesthetically relevant judgments. Such studies may reveal what Palmer et al. (Reference Palmer, Schloss, Gardner, Shimamura and Palmer2012) term default aesthetic biases (p. 213) in perceptual exposure.

Berlyne (Reference Berlyne1974) used simplified stimuli to show that people preferred medium complexity and therefore medium arousal potential, supporting his seminal psychobiological account of aesthetic preference. Using artworks, however, Martindale et al. (Reference Martindale, Moore and Borkum1990) presented data that contradicted Berlyne's seminal psychobiological account. They showed that preference increased linearly with complexity, presumably because complexity was positively correlated with judged meaningfulness of the paintings. This result suggests that theories derived from studies that do not use artworks as stimuli have limited explanatory value for explaining the complex phenomena of art appreciation. Recently, Silvia (Reference Silvia, Shimamura and Palmer2012) criticized the fluency theory of aesthetic pleasure proposed by Reber et al. (Reference Reber, Schwarz and Winkielman2004a) for exactly that reason.

The psycho-historical framework suggests that studies of art appreciation lack explanatory power if they use simplified stimuli that are disconnected from an art-historical context. Instead of examining the appreciators' sensitivity to art-historical contexts by presenting artworks, experimenters collect data about ambiguous patterns within an experimental situation that result in interpretations (Schwarz Reference Schwarz1994) that are different from appreciation of actual artworks. In contrast, there are two kinds of empirical studies that, in our opinion, come very close to meeting the methodological criteria defining empirical research within the psycho-historical framework. First, some studies manipulate appreciators' art-historical knowledge as an independent variable (Kruger et al. Reference Kruger, Wirtz, Van Boven and Altermatt2004; Silvia Reference Silvia2005c). Second, one laboratory study manipulated the art-historical context experimentally (Takahashi Reference Takahashi1995).

4.1.1. Manipulation of historical knowledge

Kruger et al. (Reference Kruger, Wirtz, Van Boven and Altermatt2004) provided evidence that appreciators use an effort heuristic to rate the quality of artworks. In their study, participants gave higher ratings of quality, value, and liking for a painting or a poem the more time and effort they thought the work took to produce. Although Kruger et al.'s study did not use the concepts of the design stance or functions of artifacts, we conclude from two premises that their effort heuristic is likely to reflect the use of the artistic design stance. First, in this study the concept of effort refers to an essential characteristic of the production of the artwork. Second, veridical attribution of effort in this study cannot be made without an inquiry into the causal history of the artifact. Because the design stance elicits an inquiry into the causal history of the artifact, the effort heuristic is likely to be an indicator of the design stance.

Silvia (Reference Silvia2005c) proposed another type of manipulation of appreciators' knowledge. He predicted that people become interested in a novel artwork if they have the potential to cope with it in such a way that they eventually understand it. In one study, Silvia presented participants with an abstract poem by Scott MacLeod (Reference MacLeod1999). While a control group just read the poem, another group was given the contextual information that the poem was about killer sharks. Provided with this information, this group showed more interest in the poem than the control group. Although Silvia's theory is ahistorical, his experimental design introduced information about an art-historical context that was not available in the poem itself. The communication of the artist's intention to write a poem about killer sharks provided the audience with an opportunity to take the artistic design stance (sect. 3.2).

4.1.2. Experimental manipulation of the art-historical context

Takahashi (Reference Takahashi1995) manipulated artistic intentions and revealed their connection to appreciators' experience. The author examined whether interindividual agreement occurs in the intuitive recognition of expression in abstract drawings. To this end, she first instructed art students to create nonrepresentational drawings that express the meanings of concepts like anger, tranquility, femininity, or illness. At a later stage, students without a background in art had to rate a selection of these drawings in regard to their meanings on a semantic differential scale (Osgood & Suci Reference Osgood and Suci1955). In addition, participants were instructed to complete the same scale for the words used to express these concepts (e.g., “anger,” “tranquility,” etc.). Takahashi (Reference Takahashi1995) found a surprising degree of agreement between the expressive meanings of the drawings and the word meanings. This agreement supports her claim that human appreciators have intuitions about expressive meanings of nonsymbolic attributes in drawings, at least within the same culture.

Takahashi showed how participants who adopt the design stance can infer an artist's intention from exposure to a drawing. From the standpoint of the psycho-historical framework, her study suggests that researchers can study such phenomena with experimental materials generated by a laboratory model of an art-historical context. The artistic design stance is a necessary link between this basic exposure to the drawing and the process of inferring artistic intentions from a work designed to express meaning. However, as participants in Takahashi's study were instructed by the experimenter to assess the drawings along emotional dimensions, it remains unclear whether participants would have adopted this design stance spontaneously.

Because the empirical paradigms used by Kruger et al. (Reference Kruger, Wirtz, Van Boven and Altermatt2004), Silvia (Reference Silvia2005c), and Takahashi (Reference Takahashi1995) meet the methodological requisites of the psycho-historical framework, these studies indicate that experimental research within the framework is feasible. Providing participants with knowledge about intentions guiding the production of a work, as Silvia did, may serve as a shortcut to inducing better knowledge of the art-historical context. Takahashi's study demonstrates that research based on a psycho-historical approach does not have to be limited to guesswork about the artist's intentions or statements by the artists about their art-historical contexts. Such artistic intentions can be instructed and lead to rigorous experimental manipulations within a laboratory model of artistic production and experience.

4.2. Dependent variables that measure appreciators' sensitivity to art-historical contexts

From the standpoint of the psycho-historical framework, dependent measures relevant to the empirical study of art appreciation should inform investigators about participants' sensitivity to art-historical contexts. However, this is often not the case in empirical aesthetics.

Two studies representative of empirical aesthetics illustrate this point. McManus et al. (Reference McManus, Cheema and Stoker1993) and Locher (Reference Locher2003) observed that participants untrained in art detected changes in pictorial composition, at least when the deviations from the original composition were considerable. The dependent variables in these studies were judgments regarding which painting is the original (Locher Reference Locher2003) or the participants' preferred work (McManus et al. Reference McManus, Cheema and Stoker1993). In both experiments, participants chose the original painting that apparently had the more balanced composition. Locher later concluded that “balance is the primary design principle by which the elements of a painting are organized into a cohesive perceptual and narrative whole that creates the essential integrity or meaning of the work” (Locher et al. Reference Locher, Overbeeke and Stappers2005, p. 169). These studies fail to consider the predictions suggested by a contextualist approach to the appreciation of imbalance.

According to a contextualist approach, appreciators' responses to violation of balance in a work should be influenced by context-specific factors such as understanding the function of an imbalanced composition in a particular situation. Investigators in this case need to design experimental paradigms using dependent measures that are sensitive to appreciator's sensitivity to balance in the art-historical context. For example, in the art-historical context of Minimalism, the monumental steel sculptures by Richard Serra (b. 1939) often use imbalance in the composition of their parts for expressive site-specific effects (Crimp Reference Crimp1981; Kwon Reference Kwon2002; Reference Kwon2009). Appreciators of Serra's sculptures must therefore deploy the design stance to understand that imbalance has expressive functions in Serra's sculptures. In a study (Palmer et al. Reference Palmer, Schloss, Gardner, Shimamura and Palmer2012) presenting photographs as stimuli, imbalance was used to convey contextual meaning. In contrast to the studies by Locher and McManus et al., the authors observed that violation of balance can enhance judged preference if imbalance fits the content a photograph is supposed to convey, providing empirical evidence for the context-sensitivity of the preference for pictorial composition and appreciation. We assume that similar effects would be observed with other artistic media.

Neuroaesthetics (Ramachandran & Hirstein 1999; Zeki Reference Zeki1998; 1999) may take art-historical context into account to make sure that the measured brain activation is connected to the artwork and not just an irrelevant epiphenomenon. For example, Ramachandran and Hirstein (1999) propose eight laws of artistic experience. These laws of artistic experience hypothesize that a few basic psychobiological processes – such as learning, grouping, and heightened activity in a single dimension or “peak shift” – are necessary conditions of aesthetic experience. The psycho-historical framework suggests that, to be relevant to art theory, the observed psychobiological process (e.g., grouping, peak shift) needs to be connected to art-historical contexts and explained as an effect of artistic creation in such contexts.

In conclusion, relevant dependent variables in experiments on art appreciation should be measures of responses that probe the appreciators' sensitivity to art-historical contexts. In addition to linking existent dependent variables (e.g., preference; perception of pictorial composition) to sensitivity to art-historical contexts, this framework calls for the use of new dependent measures that reflect the two modes of art appreciation that have been neglected by empirical aesthetics. For example, researchers may assess the amount of causal reasoning depending on different attributes of artworks. In the next section, we argue for a similarly contextualist approach in our analysis of the artistic manipulation of processing fluency.

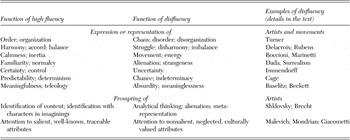

5. Artistic understanding and art-historical manipulations of fluency

The aim of this section is to discuss how an existing psychological theory, the processing fluency theory of aesthetic pleasure (Reber et al. Reference Reber, Schwarz and Winkielman2004a), can be adapted in order to meet the requirements of the psycho-historical framework. This theory focuses on the positivity of fluency and views disfluency as a source of negative affect. As we shall see, however, disfluency can elicit inferences about the artwork and a more analytical style of processing in appreciators who adopt the design stance and acquire art-historical understanding.

The term processing fluency (or fluency) refers to the subjective ease with which a mental operation is performed (Reber et al. Reference Reber, Wurtz and Zimmermann2004b). Kinds of fluency vary as a function of types of mental operations (Alter & Oppenheimer Reference Alter and Oppenheimer2009; Winkielman et al. Reference Winkielman, Schwarz, Fazendeiro, Reber, Musch and Klauer2003), such as perception (perceptual fluency) or operations concerned with conceptual content and semantic knowledge (conceptual fluency).Footnote 8

There are at least three determinants of fluency relevant to studying the basic exposure to artworks. First, fluency is a typical outcome of the perception of visual properties such as symmetry or contrast (Arnheim Reference Arnheim1956/1974; Reber et al. Reference Reber, Schwarz and Winkielman2004a). Second, repeated exposure to artworks increases the ease with which they can be perceived (Cutting Reference Cutting2003). Third, implicit acquisition of prototypes or grammars results in increased fluency (Kinder et al. Reference Kinder, Shanks, Cock and Tunney2003; Winkielman et al. Reference Winkielman, Halberstadt, Fazendeiro and Catty2006) and in affective preference (Gordon & Holyoak Reference Gordon and Holyoak1983; Winkielman et al. Reference Winkielman, Halberstadt, Fazendeiro and Catty2006; Zizak & Reber Reference Zizak and Reber2004). An example from art is style, because artworks have recurring regularities that familiarize the audience with an artist's work through implicit learning (sect. 3.1).