As the title of Bastin et al.’s target article indicates, their integrative memory model is intended to “understand memory deficits.” Memory processing is largely a product of structures of the limbic system, including (among others) the hippocampal formation, the amygdala, the basal forebrain (septal nuclei), thalamic and hypothalamic nuclei (mammillary bodies), and their interconnections (see our Figure 1) (Markowitsch Reference Markowitsch, Wilson and Keil1999). As most structures of the limbic system are engaged in processing emotional stimuli, this implies that especially the most important memory system – namely, episodic-autobiographical memory (our Fig. 2) – is always emotion-based (e.g., Markowitsch & Staniloiu Reference Markowitsch and Staniloiu2011; Stanley et al. Reference Stanley, Parikh, Stewart and De Brigard2017).

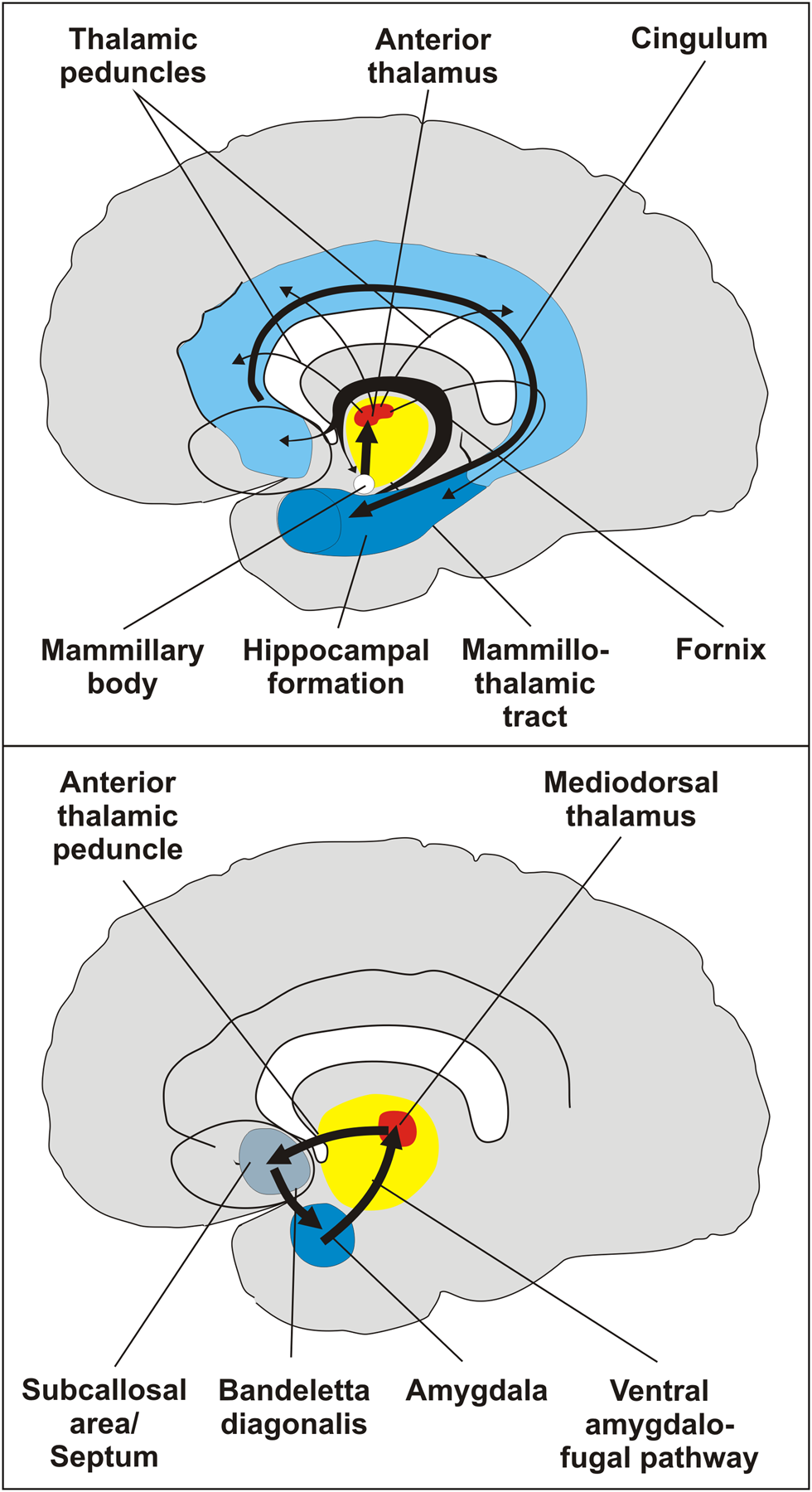

Figure 1: Schematic sagittal sections through the human brain showing the arrangement of the two main circuits implicated in memory binding. (Top) The medial or Papez circuit. (Bottom) The basolateral limbic circuit. The medial circuit is probably associated with cognitive acts of memory processing and the basolateral circuit with the affective evaluation of information. Both circuits interact.

Figure 2: The five long-term memory systems (after Markowitsch & Staniloiu Reference Markowitsch and Staniloiu2012a; Reference Markowitsch, Staniloiu and Yilmazer-Hanke2012b). Procedural memory refers to motor-based routines; priming to a higher likeliness of re-identifying already perceived stimuli. Perceptual memory allows us to distinguish an object based on distinct features. Semantic memory is factual memory (general world knowledge). Episodic-autobiographical memory is context-specific with respect to time and place, and allows mental time traveling; it is associated with an emotional overtone.

Piolino et al. (Reference Piolino, Desgranges and Eustache2009) formulated that:

This becomes most evident in patients with dissociative amnesia (Staniloiu & Markowitsch Reference Staniloiu and Markowitsch2014), who – based on stressful or traumatic events – lose the capacity to recollect episodic-autobiographical memories, while still being (largely) unimpaired in semantic, and therefore mainly unemotional, memory. We (Brand et al. Reference Brand, Eggers, Reinhold, Fujiwara, Kessler, Heiss and Markowitsch2009) found in the brains of patients with dissociative amnesia hypometabolic zones in the right inferolateral prefrontal and anterior temporal regions (including the amygdala), indicating that in these patients the synchronization of “emotional and factual components of the personal past linked to the self” (Brand et al. Reference Brand, Eggers, Reinhold, Fujiwara, Kessler, Heiss and Markowitsch2009, p. 38) is no longer possible. But patients with clear structural damage in the amygdala or in the septal nuclei also demonstrate major deficits in episodic-autobiographical memory (Cramon et al. Reference Cramon, Markowitsch and Schuri1993; Markowitsch & Staniloiu Reference Markowitsch and Staniloiu2011; Reference Markowitsch and Staniloiu2012a; Reference Markowitsch, Staniloiu and Yilmazer-Hanke2012b). This is most evident from the rare patients with symmetrical bilateral amygdalar damage due to Urbach–Wiethe disease (Cahill et al. Reference Cahill, Babinsky, Markowitsch and McGaugh1995; Markowitsch et al. Reference Markowitsch, Calabrese, Würker, Durwen, Kessler, Babinsky, Brechtelsbauer, Heuser and Gehlen1994; Siebert et al. Reference Siebert, Markowitsch and Bartel2003). And in normal individuals, the right amygdala is especially engaged in episodic-autobiographical memory retrieval (compared to fictitious memory retrieval) (Markowitsch et al. Reference Markowitsch, Thiel, Reinkemeier, Kessler, Koyuncu and Heiss2000).

As researchers Bocchio et al. (Reference Bocchio, Nabavi and Capogna2017) write, in the very first sentence of their Abstract: “The neuronal circuits of the basolateral amygdala (BLA) are crucial for acquisition, consolidation, retrieval, and extinction of associative emotional memories.” Canli et al. (Reference Canli, Zhao, Brewer, Gabrieli and Cahill2000) identified a correlation between amygdala activation and episodic memory for highly emotional, but not for neutral stimuli. Similarly, many other researchers have emphasized amygdala activations in relation to memory consolidation (e.g., McGaugh Reference McGaugh2015) and retrieval (e.g., Markowitsch et al. Reference Markowitsch, Vandekerckhove, Lanfermann and Russ2003). And already in the 1980s, in two reviews by Sarter and Markowitsch, it was argued that the human amygdala is responsible for activating or reactivating those mnemonic events which are of an emotional significance for the subjects’ life history, and that this (re-)activation is performed by charging sensory information with appropriate emotional cues (Sarter & Markowitsch Reference Sarter and Markowitsch1985a; Reference Sarter and Markowitsch1985b).

The importance of the amygdala and related structures for episodic-autobiographical memory is therefore undisputed; and it is also stressed in Pessoa's review in which he states that the amygdala is in fact no longer viewed as a simple emotional brain structure, but rather as a hub that plays a critical role in integrating emotive and cognitive processes (Pessoa Reference Pessoa2008). There are strong pathways between amygdala and hippocampus (Wang & Barbas Reference Wang and Barbas2018), as well as between amygdala and prefrontal cortex (Barbas Reference Barbas2000), a cortical region centrally implicated in memory recollection as well (Bahk & Choi Reference Bahk and Choi2018; Eichenbaum Reference Eichenbaum2017b; Lepage et al. Reference Lepage, Ghaffar, Nyberg and Tulving2000).

On the other hand, Bastin et al. mention the amygdala only once and very cursorily by stating that the “extended anterior temporal system … also includes the ventral temporopolar cortex, lateral orbitofrontal cortex, and amygdala” (sect. 2.1.4, para. 1). They fail to include the amygdala (or the septal nuclei) in their integrative memory model. On account of this omission, their integrative memory model lacks essential neuroanatomical components that are necessary for memory recollection – a lack, particularly, when it comes to understanding the brain bases of memory deficits in neurological and psychiatric patients.

As the title of Bastin et al.’s target article indicates, their integrative memory model is intended to “understand memory deficits.” Memory processing is largely a product of structures of the limbic system, including (among others) the hippocampal formation, the amygdala, the basal forebrain (septal nuclei), thalamic and hypothalamic nuclei (mammillary bodies), and their interconnections (see our Figure 1) (Markowitsch Reference Markowitsch, Wilson and Keil1999). As most structures of the limbic system are engaged in processing emotional stimuli, this implies that especially the most important memory system – namely, episodic-autobiographical memory (our Fig. 2) – is always emotion-based (e.g., Markowitsch & Staniloiu Reference Markowitsch and Staniloiu2011; Stanley et al. Reference Stanley, Parikh, Stewart and De Brigard2017).

Figure 1: Schematic sagittal sections through the human brain showing the arrangement of the two main circuits implicated in memory binding. (Top) The medial or Papez circuit. (Bottom) The basolateral limbic circuit. The medial circuit is probably associated with cognitive acts of memory processing and the basolateral circuit with the affective evaluation of information. Both circuits interact.

Figure 2: The five long-term memory systems (after Markowitsch & Staniloiu Reference Markowitsch and Staniloiu2012a; Reference Markowitsch, Staniloiu and Yilmazer-Hanke2012b). Procedural memory refers to motor-based routines; priming to a higher likeliness of re-identifying already perceived stimuli. Perceptual memory allows us to distinguish an object based on distinct features. Semantic memory is factual memory (general world knowledge). Episodic-autobiographical memory is context-specific with respect to time and place, and allows mental time traveling; it is associated with an emotional overtone.

Piolino et al. (Reference Piolino, Desgranges and Eustache2009) formulated that:

visual mental imagery and emotional experience are critical phenomenological characteristics of episodic AM [autobiographical memory] retrieval. Hence, the subjective sense of remembering almost invariably involves some sort of visual (Greenberg & Rubin Reference Greenberg and Rubin2003) and emotional (Rubin & Berntsen Reference Rubin and Berntsen2003) re-experiencing of an event. (Piolino et al. Reference Piolino, Desgranges and Eustache2009, p. 2315).

This becomes most evident in patients with dissociative amnesia (Staniloiu & Markowitsch Reference Staniloiu and Markowitsch2014), who – based on stressful or traumatic events – lose the capacity to recollect episodic-autobiographical memories, while still being (largely) unimpaired in semantic, and therefore mainly unemotional, memory. We (Brand et al. Reference Brand, Eggers, Reinhold, Fujiwara, Kessler, Heiss and Markowitsch2009) found in the brains of patients with dissociative amnesia hypometabolic zones in the right inferolateral prefrontal and anterior temporal regions (including the amygdala), indicating that in these patients the synchronization of “emotional and factual components of the personal past linked to the self” (Brand et al. Reference Brand, Eggers, Reinhold, Fujiwara, Kessler, Heiss and Markowitsch2009, p. 38) is no longer possible. But patients with clear structural damage in the amygdala or in the septal nuclei also demonstrate major deficits in episodic-autobiographical memory (Cramon et al. Reference Cramon, Markowitsch and Schuri1993; Markowitsch & Staniloiu Reference Markowitsch and Staniloiu2011; Reference Markowitsch and Staniloiu2012a; Reference Markowitsch, Staniloiu and Yilmazer-Hanke2012b). This is most evident from the rare patients with symmetrical bilateral amygdalar damage due to Urbach–Wiethe disease (Cahill et al. Reference Cahill, Babinsky, Markowitsch and McGaugh1995; Markowitsch et al. Reference Markowitsch, Calabrese, Würker, Durwen, Kessler, Babinsky, Brechtelsbauer, Heuser and Gehlen1994; Siebert et al. Reference Siebert, Markowitsch and Bartel2003). And in normal individuals, the right amygdala is especially engaged in episodic-autobiographical memory retrieval (compared to fictitious memory retrieval) (Markowitsch et al. Reference Markowitsch, Thiel, Reinkemeier, Kessler, Koyuncu and Heiss2000).

As researchers Bocchio et al. (Reference Bocchio, Nabavi and Capogna2017) write, in the very first sentence of their Abstract: “The neuronal circuits of the basolateral amygdala (BLA) are crucial for acquisition, consolidation, retrieval, and extinction of associative emotional memories.” Canli et al. (Reference Canli, Zhao, Brewer, Gabrieli and Cahill2000) identified a correlation between amygdala activation and episodic memory for highly emotional, but not for neutral stimuli. Similarly, many other researchers have emphasized amygdala activations in relation to memory consolidation (e.g., McGaugh Reference McGaugh2015) and retrieval (e.g., Markowitsch et al. Reference Markowitsch, Vandekerckhove, Lanfermann and Russ2003). And already in the 1980s, in two reviews by Sarter and Markowitsch, it was argued that the human amygdala is responsible for activating or reactivating those mnemonic events which are of an emotional significance for the subjects’ life history, and that this (re-)activation is performed by charging sensory information with appropriate emotional cues (Sarter & Markowitsch Reference Sarter and Markowitsch1985a; Reference Sarter and Markowitsch1985b).

The importance of the amygdala and related structures for episodic-autobiographical memory is therefore undisputed; and it is also stressed in Pessoa's review in which he states that the amygdala is in fact no longer viewed as a simple emotional brain structure, but rather as a hub that plays a critical role in integrating emotive and cognitive processes (Pessoa Reference Pessoa2008). There are strong pathways between amygdala and hippocampus (Wang & Barbas Reference Wang and Barbas2018), as well as between amygdala and prefrontal cortex (Barbas Reference Barbas2000), a cortical region centrally implicated in memory recollection as well (Bahk & Choi Reference Bahk and Choi2018; Eichenbaum Reference Eichenbaum2017b; Lepage et al. Reference Lepage, Ghaffar, Nyberg and Tulving2000).

On the other hand, Bastin et al. mention the amygdala only once and very cursorily by stating that the “extended anterior temporal system … also includes the ventral temporopolar cortex, lateral orbitofrontal cortex, and amygdala” (sect. 2.1.4, para. 1). They fail to include the amygdala (or the septal nuclei) in their integrative memory model. On account of this omission, their integrative memory model lacks essential neuroanatomical components that are necessary for memory recollection – a lack, particularly, when it comes to understanding the brain bases of memory deficits in neurological and psychiatric patients.