1. Introduction

During intercommunal violence in which one community affiliated with a faith or religion is pitted against another community affiliated with a different faith, churches, mosques, synagogues, temples, and other religious buildings of the former or the latter are usually targeted, and either partially or completely destroyed. Muslim religious sites in Hindu-majority IndiaFootnote 1 and Buddhist-majority Myanmar,Footnote 2 and Christian religious sites in Muslim-majority IndonesiaFootnote 3 and Muslim-majority MalaysiaFootnote 4 have been vandalized, destroyed, and burnt by members of majority groups. Several instances in which places of worship or religious sites were attacked did not originate from controversies or conflicts over the existence of such places or sites. More specifically, the legality of those places and sites was not an issue. Rioters often target them because they symbolically and physically represent or belong to the religious communities whom they want to attack or hurt. Usually, the destruction, partial or complete, of religious places and sites usually stems from either one-sided or mutual religious violence between two religious communities sparked by other issues. For example, Muslims attacked churches in Malaysia in January 2010 by hurling bricks and stones, throwing petrol bombs, and spraying paint in the wake of a court decision that allows Christians to use the Arabic term Allah—which Muslims claim sole ownership of—to refer to God in their Malay-language religious publications.Footnote 5 Likewise, mosques were ransacked and torched in Meiktila in Myanmar in March 2013 during anti-Muslim religious violence that originated from an argument at a Muslim-owned gold shop between the shopkeepers and a Buddhist couple.Footnote 6 In September 2012, extremist Muslim mobs in Bangladesh torched and ransacked Buddhist temples, triggered by a Facebook post allegedly defaming the Islamic holy book Qur’an.Footnote 7 More recently, mosques in Sri Lanka were damaged by Buddhist mobs in May 2019 apparently out of revenge for Easter bombings of churches and luxury hotels by extremist Muslims.Footnote 8 Two facts are noteworthy: (1) religious buildings only became indirectly involved or targeted in the later stage(s) of violence; and (2) non-religious houses and shops were also attacked together with religious buildings, showing that the latter were not the only targets.

In comparison, there are instances in which religious buildings have been targeted in the first place by riotous mobs under the pretext of (il)legality. Rioters and mobs, interestingly, give a legal excuse that they have the right to destroy or remove, or at least demand the removal and destruction of, religious buildings that are alleged to have been built illegally, namely without getting proper legal or prior official approval. Often, the (il)legality of sacred spaces is considered not just in terms of contemporary or modern administrative law, but also in terms of historical continuity. For example, the famous case of the demolition of the sixteenth-century medieval Babri Mosque in the city of Ayodhya in Uttar Pradesh, India on 6 December 1992 is based on a Hindu historical and archaeological claim that the mosque was built on the birthplace of Rama.Footnote 9 Likewise, in recent years, several Muslim madrasas and mosques have been burnt, destroyed, or shuttered by force by Buddhist mobs in Myanmar who allege that the Muslim religious buildings in question were built illegally.Footnote 10 Also, extremist Muslims in Indonesia have protested and intimidated “illegal” churches and Ahmadiyah mosques across Indonesia, and often successfully forced authorities to close down those churches and mosques.Footnote 11 Mobs and rioters apparently take the law into their own hands and act as vigilantes. The mobbish use of the language of law or (il)legality in instances of attack upon and destruction of religious sites and buildings thus deserves closer scrutiny by legal scholars, especially those working in the subfields of law and religion, and law and society.

In terms of law enforcement, alleged, controversial, or undecided illegality also seems to have provided national and local authorities with an excuse to accede to mobbish demands that churches and mosques be destroyed or sealed. Because extremists who almost always belong to religious majorities gather and engage in unruly, disorderly, and mobbish behaviour in meting out themselves to or demanding legal action against minorities’ religious buildings, police and local authorities who themselves usually belong to religious majorities expediently use the issue of il(legality) and absolve themselves of their failure to protect religious minorities and their places of worship and religious buildings. They seem to reason that, although mobs must not attack or destroy places of worship and religious buildings, the mobs have a justification, however weak it is, for their wrath upon the places and buildings with questionable legal status.

This article identifies and examines this important reason, or more correctly this excuse, of illegality provided by: (1) religious majoritarian mobs in justifying violence against places of worship and religious buildings of minorities; and (2) police and local authorities in absolving themselves of the failure to uphold public order and the rule of law, protect religious minorities who are citizens, and punish religious minorities. To support this argument, by primarily using Myanmar-language resources, this article discusses and analyzes cases of (1) allegedly illegal mosques; (2) madrasas being used as or reconstructed into mosques; (3) buildings being constructed as mosques; (4) private homes and public spaces being used as mosques; and (5) closed mosques not being allowed to reopen. By discussing those five instances in which illegality is invoked to justify the destruction and closure of religious buildings, this paper argues that what was done to the buildings constitutes legal violence.

The article has five further sections. In Section 2, the author discusses the role of religion in violence and the concept of legal violence. In Section 3, the author discusses religious demography and second-class citizenship of Muslims in Myanmar. In Section 4, the author traces the colonial roots of mosques. In Section 5, the author discusses the occurrence of interreligious violence post 2012 and the consequent emergence of anti-mosque extremism and vigilantism. In Section 6, the author describes and analyzes five illustrative cases of illegal or allegedly illegal mosques, madrasas, etc. Finally, Section 7 offers some conclusions. It should here be clarified that the focus of this article is on anti-mosque and anti-madrasa-cum-mosque narratives and activities in Myanmar from 2012 onwards. To be clear, such narratives and activities are not entirely new, but the focus on post-2012 developments is important because they are unprecedented in terms of scale and longevity.

2. Religion, violence, and legal violence

Negating the grand theory of secularization, religiosity that constitutes existential security has been on the rise in many societies.Footnote 12 Studies of religious or interreligious violence in general highlight the ambivalent role of religionFootnote 13—whose peace-making or mediating role amidst conflict is often taken for granted or overemphasized—that may invoke itself in violence, especially when religion or religious identity is used to mobilize actors and institutions, and legitimize their actions.Footnote 14 Zooming in on the religion–conflict nexus, many studies highlight the role of religion, or, more correctly, religious identity, in creating dichotomous social identities of in-groups and out-groups, thereby making such groups prone to intergroup conflicts and violence.Footnote 15 But other studies have only made modest claims about the role of religion in violence and remind that religion is not the only factor behind violence; religion has a role in causing it in the first place or increasing the tempo of violence along the way if it was the original cause.Footnote 16 Therefore, in short, the religion–conflict or religion–violence nexus is a contested terrain, necessitating nuanced, in-depth, and empirical analysis of actual cases of violence in which religion or religious identity played or has been the cause or one of the causes behind the violence.

To further zoom in on this contested relationship between religion and violence, let us look at what role law plays in violent religious episodes and how. Law and law enforcement, which are supposed to prevent violence in the first place, deal with it along the way, and punish it in the aftermath, can also commit violence, though it may sound paradoxical.Footnote 17 The literature on criminal laws used in immigration control and their impacts on immigrants terms it legal violence and highlights “the complex and often overlooked effects of the law.”Footnote 18 Though the concept of legal violence is predominantly employed in contemporary immigration studies, it has also been invoked in studies of the effect of different bodies of law upon native communities during colonial times,Footnote 19 upon non-immigrant citizens,Footnote 20 upon indigenous peoples,Footnote 21 and upon women.Footnote 22

This paper draws upon that concept of legal violence to shed light on the way in which (il)legality has been invoked and misused, and legal violence committed against Muslim religious places of worship and buildings by state and non-actors in Myanmar, as they deem convenient and expedient.

3. Religious demography and second-class citizenship of Myanmar Muslims

Islam is recognized by name as one of the five religions professed in Myanmar—the others being Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, and Animism—by the Constitution of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, which has been in operation since January 2011.Footnote 23 There is no official state religion, although the Constitution recognizes Buddhism as the majority religion, effectively making the other four minority religions.Footnote 24 In terms of religious demography, Myanmar is home to Buddhists (87.9%), Christians (6.2%), Muslims (4.3%), Hindus (0.5%), and Animists (0.8%).Footnote 25 However, one important fact about this Myanmar Muslim population is that it includes the Rohingya, who were not counted in the most recent 2014 census, but who had an estimated population of 1,090,000 people. If we exclude the Rohingya, the Myanmar Muslim population significantly decreases to only 2.3% of the total.Footnote 26 In other words, about half of the Myanmar Muslim population are the Rohingya, whom successive Myanmar governments have failed to recognize as citizens and provide identity documentation for at least since the early 1990s.Footnote 27

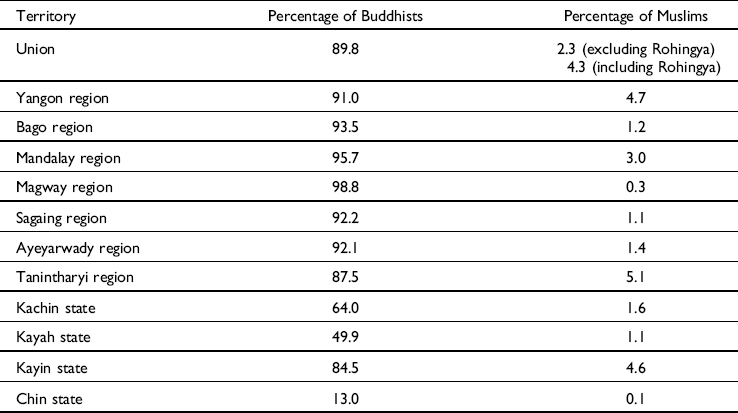

Although Islam is constitutionally enshrined, its adherents in Myanmar suffer from legal disabilities due to their uncertain citizenship status and they are frequently discriminated against. Myanmar officially recognizes 135 ethnic groups or national races as citizens and, among these, only one Muslim or predominantly Muslim group or race called the Kaman is included. The Kaman are a tiny minority numbering not more than 50,000 in total and many, if not most, of them have lived in Rakhine for centuries.Footnote 28 The Kaman form only 4.4% of the total Muslim population (1,147,495 persons)Footnote 29 in Myanmar and only they are considered native under the law. The rest of the Muslim population, namely 95.6%, are instead considered people of South Asian ancestry (Indian, Pakistani, or Bengali) or are of mixed ancestry, and thereby do not have clear citizenship status. In Myanmar, citizens of native ancestry are considered as first-class or gold-class citizens. In contrast, Muslims are legally and socially treated as second-class citizens according to the current Myanmar Citizenship Law (1982).Footnote 30 This double-minority status of most Muslims in terms of both religious affiliation and ancestral origin has made them vulnerable in Myanmar. Table 1 shows the demographic comparison between the majority Buddhists and minority Muslims in Myanmar. Muslims, notably, constitute a smaller minority than Christians do, although the latter have different relations with the Buddhist majority.

Table 1. Demographic statistics of Buddhists and Muslims in Myanmar

Source: Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population (2016), p. 3.

In sheer demographic terms, Buddhists constitute absolute majorities in 13 out of 15 territories—seven states, seven regions, and Nay Pyi Taw.Footnote 31 This demographic breakdown could be significantly manipulated with the inclusion or exclusion of the Rohingya in the Myanmar Muslim population. The Rohingya Muslims form almost half of the population of Muslims in Myanmar. In particular, they are a sizeable group in Rakhine state. If they are included in the demographic statistics, Rakhine Muslims form 35.6% of the state population. Rakhine Buddhists form only a bare majority of 63.3%. However, if Rohingya Muslims are excluded at the Rakhine state level, Rakhine Buddhists become an absolute majority of 96.2%.

The discrimination and persecution of Muslims in Myanmar, especially since the 1990s, have been increasingly discussed in academic and political commentaries. In recent years, there has also been a securitization of the Muslim-minority issue in Myanmar.Footnote 32 The Rohingyas have faced the worst of this wave of discrimination as they “faced a citizenship and identity crisis (2012–), a campaign for their wholesale disenfranchisement (2015), and attacks culminating in a refugee exodus (2017–present).”Footnote 33 Despite ample evidence that the Rohingya have been arbitrarily deprived of citizenship documentation and enfranchisement legally, politically, and ideologically,Footnote 34 the government of Myanmar adamantly claims that the citizenship of the Rohingya is pending, subject to never-ending vigorous scrutiny. Echoing the government perspective, a majority of people in Myanmar, most of whom hold strong anti-Rohingya sentiments, also presume the Rohingya to be “illegal.” This has had the indirect effect of attaching illegality to Muslim religious buildings and sites that the Rohingya have built and used—a case to be discussed in detail later. But why is the mosque, legal or otherwise, a heated issue in Myanmar? A basic but extremely important question is: How many mosques are there in Myanmar? I turn to this below.

4. Colonial roots of mosques in Myanmar

There is currently no official updated list of the number of mosques, letalone madrasas, in Myanmar. However, a confidential Myanmar government report prepared in the year 2000 states that there were 1,716 mosques in Myanmar. Of these, 649, 225, and 164 were in Rakhine state, Mandalay region, and Yangon region, respectively.Footnote 35 This means that more than a third of the total number of mosques in Myanmar, according to this confidential report, were in the Rakhine state. This is not surprising since, as stated above, the Rohingya constitute about half of the total Muslim population in Myanmar.

Notably, several new mosques were built after independence in 1948 during the parliamentary period (1948–62) because the U Nu government was not hostile towards Muslims and Islam, despite the fact that U Nu himself was an extremely pious Buddhist and drew upon Buddhist majoritarian identity in politically salient issues such as the move to declare Buddhism as State Religion in 1961.Footnote 36 However, this seemingly benign attitude towards Muslims drastically changed during subsequent regimes: the military-coup Revolutionary Council regime (1962–74); the socialist, one-party, and military-dominated Burma Socialist Programme Party regime (1974–88); and the military-coup State Law and Order Restoration Council/State Peace and Development Council (SLORC/SPDC) regime (1988–2011).Footnote 37 The construction of new mosques from the 1960s onwards became almost impossible. Even repairing or maintaining existing ones became increasingly difficult.Footnote 38 But, this does not mean that no new mosques were built between 1962 and 2011. In fact, several “small” local mosques were built post 1962. Since 2013, these mosques have been especially vulnerable to contestation over their legality and opposition from anti-mosque vigilante extremists. To be clear, there is no official law or statement explicitly prohibiting the building of mosques. There is also no clarity as to the type of the land grants required to build mosques. However, it is common knowledge that, during the period between 1962 and 2011, building new mosques became impossible.Footnote 39 This is especially problematic as the Muslim community has grown. The number of mosques is unsustainable for housing Muslim prayers, as it has not increased in a way proportional to the growth in the size of the community.

In Yangon, which used to be the capital of Myanmar until it was moved to Nay Pyi Taw in 2005, the shortage of mosques was particularly felt. Most mosques built during the colonial period are concentrated in downtown Yangon, providing space for Muslim communities living in townships such as Kyauktada, Pabedan, and Botataung. However, sizeable Muslim communities are also found in relatively newer suburbs or satellite towns—South Okkalapa, North Okkalapa, and Thaketa, which were built by the Caretaker Government (1958–60) in the late 1950s; and ten satellite towns (Hlaingtharyar, Dagon Myothit (further divided into East Dagon, North Dagon, South Dagon, and Dagon Seikkan townships), and Shwepyithar are the three biggest ones) built by the SLORC/SPDC in the 1990s. As Table 1 shows, eight mosques exist in Thaketa township, which has 24,582 Muslims, whereas three exist in South Okkalapa and North Okkalapa, where a combined population of 9,440 live. But almost no mosques have been allowed to be built in satellite towns built in the 1990s. This reflects the SLORC/SPDC largely “anti-Muslim” attitude in their governance and policy-making.Footnote 40

From Table 2, we can see three patterns. First, the geographical spread of mosques in Yangon region is not proportional to the number of Muslim residents. Second, and more importantly, most of the mosques were built before Myanmar’s independence from the British. Finally and most importantly, the government of Myanmar has decreasingly permitted the construction of new mosques, especially in the 1990s and 2000s. The most glaring case is South Dagon township, which does not have a single mosque or permanent prayer space, even though it has 16,685 Muslim residents. In contrast, the townships of Kyauktada and Botataung have eight and ten mosques for about 6,679 and 5,374 residents, respectively, all of which were built in the colonial period. In May 2019, member of Yangon-region Parliament U Nyi admitted that Buddhist residents had objected continuously to a request by Muslims in South Dagon for a mosque.Footnote 41

Table 2. Numbers of Muslims and mosques in selected townships in Yangon (as of 2017)

a Although many townships including those I mention here were only administratively and geographically structured by name in the 1970s, I categorize them here as pre-independence, i.e. pre-1948, because inhabitation in them began before or during the British colonization and mosques were built in that period.

b The General Administration Department does not explain what a “rural mosque” means; it most probably means that a rural mosque is small and largely unnoticeable.

Source: General Administration Department (2017).

Faced with the shortage or non-existence of mosques in close proximity to their homes, Muslim communities have resorted to two pragmatic ways: (1) using madrasas as temporary prayer halls especially for weekly Friday prayers and yearly Taraweeh prayersFootnote 42; and (2) using their own homes as makeshift communal prayer spaces.Footnote 43 With respect to the madrasas, the government and local Buddhist communities have largely tolerated existing and the few new madrasas because they see them as religious schools for Muslim children. However, although the use of madrasas and private homes as communal prayer spaces used to be accepted or at least tolerated by local authorities in Yangon in the 1990s and 2000s and was an open secret among Muslim and Buddhist residents,Footnote 44 it has become a controversial and securitized issue in recent years. It has also been increasingly viewed as an illegal Muslim practice by the state and Buddhists. The situation deteriorated severely with the rise in anti-Muslim Buddhist nationalism from 2012 onwards that targeted any matter relating to Islam and Muslims in which mosques and madrasa-cum-mosques found themselves embroiled.

Amid the emergence of an extremely popular narrative that Rohingyas, and some non-Rohingyas as well, are undocumented at best and illegal at worst, the implications of this narrative extended to affect mosques, madrasas, and any buildings alleged to be mosques. Many Muslims found not only themselves, but also their communal mosques and madrasas to be tainted with illegality. This targeting of mosques, madrasas, and other places for religious congregation clearly violate Myanmar Muslims’ religious freedom to worship individually and in community. Being places where Muslims regularly gather for offering prayers—whether they are for groups or for individuals; held daily, on Friday, or in Ramadan; for giving or attending sermons, and for other religious activities—mosques symbolically and physically represent or belong to Muslims. Although many Muslims offer individual prayers at mosques, most go there for congregational prayers and sermons. Therefore, mosques may be said to largely represent communal or congregational Islam. They are highly visible as physical infrastructures distinct from majority religious sites and buildings where Islam is a minority religion. Also, because mosques often publicly broadcast adhan (the call to Muslim prayers) over the loudspeaker, they are audibly distinct and noticeable in a Muslim-minority context. Perhaps due to these physical, architectural, visual, and audial distinctions of mosques with deep communal links to Muslims, they are naturally prone to targeting and attack whenever there is interreligious or intercommunal tension or violence. Although they are basically physical structures, mosques usually become embroiled in communal or social conflicts, and they are often desecrated, attacked, stoned, ransacked, burnt, bulldozed, destroyed, and closed. In Buddhist-versus-Muslim or largely anti-Muslim riotous conflicts that happened in colonial Burma and independent Burma/Myanmar,Footnote 45 mosques often, unsurprisingly, bear the brunt. When Buddhists are angry with, for any founded or manufactured reasons, and seek to cause harm to Muslims, mosques and madrasas become victims.

The targeting of madrasas is also due to their symbolism. What is a madrasa? What may or may not be done by a madrasa? Why is praying inside a madrasa deemed undesirable, improper, or illegal? Basically, a madrasa is a place where Muslim children are taught how to recite the Qur’an and pray, and other important practices of Islam. Teaching children how to pray is an important part of madrasa education. However, there are no laws or rules about what a madrasa can or cannot do. Whether children or adults may use madrasas for individual or communal prayers is an important administrative question that has not been satisfactorily answered. Nonetheless, to Buddhist nationalists, the Muslim use of madrasas for individual or communal prayers is suspicious because they supposedly expect that the space is only meant for teaching children about Islam. The regulatory ambivalence of the “legal” uses of madrasas can similarly be seen with regard to the use of private homes for occasional or regular communal prayers. There are no clear laws prohibiting the use of private homes for prayers. Objections to their use for religious gathering are often rooted in anti-Muslim sentiment.

Before discussing instances of the destruction or closing-down of mosques and madrasas, let us first take a look at the emergence of anti-mosque Buddhist vigilantism and extremism in Myanmar as an important intervening variable. This anti-mosque/madrasa-cum-mosque brand of anti-Muslim extremism has provided a scheme of interpretation of Buddhist–Muslim interreligious relations in which the mosque/madrasa-cum-mosque has featured as a site of controversy, illegality, and riotous violence.

5. Interreligious violence, anti-mosque extremism, and legal violence

At the landmark monks’ meeting on 27 June 2013 at which Ma Ba Tha was established, Sitagu Sayadaw Nyanissara—arguably the most prominent senior monk in Myanmar and initially the one who held Ma Ba Tha’s vice-chair position—claimed that the construction of Soorthi Bazaar (now Theingyi Market) in downtown Rangoon (now Yangon) near Sule Pagoda by the British in the nineteenth century resulted in the demolition of a pagoda as big as Sule Pagoda and many important Buddhist buildings. He also claimed that a mosque built nearby soon after the bazaar was built remains until now. He thus openly lamented the displacement of Buddhist buildings by Muslim ones.Footnote 46 His narrative spread like wildfire online and offline, degrading the mosque largely as a colonial structure that displaced native Buddhist sites.

As mentioned earlier, such anti-mosque discourse is not entirely new. In late 1961, monks protested against five new mosques that were being built, with government permission, in the North/South Okkalapa and Thaketa townships established in the outskirts of Yangon in 1959,Footnote 47 and they even occupied a partially completed mosque in North Okkalapa for two weeks after which they demolished it and burnt another mosque.Footnote 48 Existing mosques have also been targeted in riots that happened in various parts of Myanmar in the 1990s and 2000s. These riots were mostly “seemingly” spontaneous and authorities were slow, at best, and, at worst, did not do much to protect Muslim religious buildings during the violence.Footnote 49 Most of these mosques were partially destroyed and many were allowed to reopen after the violence. Some were completely destroyed and remained closed for years after the violence.Footnote 50 It is noteworthy that the narrative of upholding public order and questioning the legality of those mosques (and often madrasas as well) was not, at least explicitly, used by the then military regime SLORC/SPDC. This is presumably because the regime in power was a dictatorship and did not need to justify the way they acted. Typically, what had happened to mosques was forgotten, and the story went on until another riot happened when mosques were again attacked. Many of those attacks did nonetheless receive coverage in annual reports issued by the US Commission on International Religious Freedom.

Significant political and social changes from 2010 onwards opened a new chapter in the way in which the Myanmar government deals or is supposed to deal with the people. Although power remained to be largely under the control of the military that posits itself as a caretaker,Footnote 51 people started enjoying political and civil rights—especially freedoms of association, assembly, protest, and expression—that they did not have in the 1990s and the 2000s. The generals started giving up some of their absolute powers.Footnote 52 After ex-general U Thein Sein—who was prime minister of Myanmar under the previous SLORC/SPDC regime—was sworn in as president in 2011, the new administration apparently felt the need to gain direct popular support. The extreme popularity of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi was formidable and of concern to the regime. She was released from house arrest in November 2010 and became a member of Parliament after winning by-elections in April 2012. The by-elections saw the opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) chaired by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi win 43 out of the 44 seats it contested.Footnote 53

In this context of a fragile, uncertain political transition, Myanmar faced unprecedented intercommunal or interreligious violence in June 2012 in Rakhine state.Footnote 54 The violence spread like wildfire to other parts of Myanmar in 2013 and 2014.Footnote 55 All those seemingly sectarian conflicts were constructed as sparked by Muslim actions—most commonly rape and/or sexual harassment of Buddhist women and alleged blasphemy—and were met with Buddhist fury.Footnote 56 Again, in the eyes of Buddhists, all those conflicts originated in the rape and murder of a Rakhine Buddhist lady by three Muslim men on 28 May 2012 in Rakhine state. Muslims in Rakhine state, with the exception of Kaman Muslims and a few other non-Kaman/non-Rohingya Muslims in cities such as Thandwe, started to be viewed as illegal Bengali migrants, which is the preferred name for the Rohingya, and portrayed as such in the media and public debates on the conflict in Rakhine.Footnote 57 An extreme narrative that accompanied the fierce rejection of the Rohingya as part of the Myanmar citizenry was that Muslims in Myanmar by and large are either, at best, “citizens” to be watched—people whose citizenship must either be under vigorous scrutiny—or, worse, illegal.Footnote 58 The narrative of the illegal status of Myanmar Muslims soon extended to questions about the legality of their religious buildings, namely mosques and madrasas.

Clamouring for the defence of innocent, threatened Buddhism and Buddhists, especially Buddhist women,Footnote 59 under siege by the Muslim male aggressor and for Buddhists’ religious freedom and supremacyFootnote 60 —which resonates with old nationalism of colonial timesFootnote 61 —several national and local Buddhist nationalist networks emerged to claim to be true representatives and defenders of the Buddhist majority.Footnote 62 Two of them that became most prominent were the highly symbolic economic 969 campaign and the extremely legal mobilizational Ma Ba Tha (Organization for the Protection of Race and Religion).Footnote 63 Whereas 969 Footnote 64 was established in October 2012 in the aftermath of the second wave of Rakhine violence, Ma Ba Tha was founded in June 2013 amidst mounting international criticisms against Buddhist animosities towards Muslims and the alleged involvement of monks such as U Wirathu and 969 leaders.Footnote 65

969 was mostly a network-type movement with five monks—of a monastic association based in Mawlamyine in Mon State—touring Myanmar and encouraging Buddhists not to buy from Muslims, but to buy from Buddhists. Individual Buddhists, smaller Buddhist networks, associations, and individual Buddhists supported the use of the 969 emblem at homes, offices, shops, taxis, buses, and the like.Footnote 66 With the establishment of Ma Ba Tha, anti-Muslim Buddhist nationalism that was by then only several months old reached a stage of advanced institutionalization and 969 leaders also sat on the executive committee of Ma Ba Tha, overlapping the two associations/organizations.Footnote 67 Ma Ba Tha relentlessly demanded four race and religion laws from 2013 through 2015—monogamy law, Buddhist women’s special marriage law, religious conversion law, and population-growth-control law—all of which were introduced in legislation by August 2015.Footnote 68

To accomplish their respective projects, 969 and Ma Ba Tha campaigners and their like-minded groups and networks—most prominent among them are the layperson-only Myanmar National Network and the monk-only Patriotic Monks of Myanmar—worked tirelessly from 2012 until June 2019 (the time of writing) by constructing an image of the threat of Islam and Muslims. The Islamophobic master narrative of 969 and Ma Ba Tha has two parts: (1) Muslims make themselves richer by buying from or eating at Muslim-owned shops and restaurants and avoiding Buddhist-owned ones; and (2) polygamous and hyper-fertile Muslim men plot to convert Buddhist women to Islam through interfaith marriage and create bigger families faster compared to monogamous Buddhist men, seeking to overtake Buddhist-population growth. Therefore, Buddhists must stop buying at Muslim shops and the four laws must be enacted as soon as possible.Footnote 69

It is in this master narrative of the Muslim threat that the mosque (and the madrasa as well, to some extent) figures prominently. Mosques are constructed as a threat to Buddhist Myanmar in at least three ways: (1) mosques are secret and opaque; (2) mosques are enemy bases in which an aggressive anti-Buddhist brand of Islam is taught and propagated; and (3) hundreds of mosques have been illegally built. For example, U Wirathu, the internationally known provocative and media-friendly monk affiliated with both 969 and Ma Ba Tha, said in May 2013:

And when they [Muslims] become rich, they build more mosques which, unlike our pagodas and monasteries, are not transparent. They’re like enemy base stations for us. More mosques mean more enemy bases, so that is why we must prevent this.Footnote 70

Most importantly, this anti-mosque narrative of U Wirathu targets all mosques, legal or otherwise. These three accusations form a twisted, manufactured narrative, or what George has called “hate spin.”Footnote 71 While Myanmar is a multi-ethnic, multireligious society, it tends to be a “closed” society. With few exceptions, most non-Muslims have never been to mosques, as they think these are only meant for Muslims. Similarly, Muslims would not usually invite non-Muslims to mosques. Mosques, therefore, become de facto segregated Muslim-only spaces, which are usually closed except at prayer times. Mosques do not explicitly deny non-Muslims entry, although it is intercommunally understood and practised. The same can be generally said of Christian churches and Hindu temples because non-Christians and non-Hindus in Myanmar do not usually visit them, although churches and temples do not disallow it explicitly. Buddhist pagodas and monasteries are the exceptions because they are open to everybody. So, accusations that mosques are opaque or secret seem convincing, at least by 969 and Ma Ba Tha followers.

Accusations of opaqueness and secrecy apparently forced mosques in other parts of Myanmar to open their doors for non-Muslim visitors in the immediate aftermath of riotous violence in non-Rakhine places such as Lashio (in May 2013). For example, amid mounting accusations that mosques have secret underground space for storing arms and planning militancy, the mosque in Bo Aung Kyaw Street (lower block) in downtown Yangon hosted on 16 June 2013 about 100 visitors that included monks and lay Buddhists, with the aim of clearing up anti-mosque accusations.Footnote 72 A mosque in Yangon in Botataung township, known as “59th Street Mosque” since it is in the 59th Street, asked prominent student leaders such as Ko Ko Gyi (a Buddhist)Footnote 73 and Mya Aye (a Muslim himself)Footnote 74 to give talks at the Prophet Day event in October 2013—notably in a few days after the violence in Thandwe in Rakhine state. A few days later, the same mosque invited a Buddhist monk and a Christian pastor to come inside and give interfaith talks.Footnote 75 Special tours to mosques as well as religious buildings of other faiths were arranged in 2014 in the form of interfaith toursFootnote 76 and mosques even offered food and alms to Buddhist monks inside.Footnote 77

Those Muslim-led and often interfaith responses to accusations of opaque mosques, which were repeatedly seen and heard on social media in 2013 and 2014, seemed to have borne fruit by 2015, when such accusations became extremely rare. Ironically, that mosques were made in the first place to open doors to visitors and hold special functions for monks and Buddhist speakers shows the influence of the anti-mosque narrative. More importantly, it also showed that the state, especially its security apparatus, which is supposed to ensure protection to mosques, failed to uphold its duty of law and order. Instead, mosques had to protect themselves by arranging interreligious tours and monastic activities inside that were graciously joined by peaceful Buddhists, monks, or lay Buddhists.

The second accusation that mosques are enemy bases is also backed by its share of truth or reasoning for anti-mosque Buddhist extremists. Some mosques in various places such as ThandweFootnote 78 and MandalayFootnote 79 were found by the police to hoard small weapons such as swords, sticks, and marbles during the riotous years, and this was used as evidence to back up the claim that mosques are enemy bases. In 2012, 2013, and 2014, the general pattern of police reaction to religious violence was slow or ineffective at best, and biased or anti-Muslim at worst. This perception of the lack of the rule of law widely shared by both Muslims and peaceful Buddhists led to two societal pushbacks or urgent measures. One is holding informal interfaith peace and conflict-preventing committees formed by local governmentsFootnote 80 or by people themselves on which Muslims, Buddhists, etc. served in streets, quarters, townships, etc. across the country.Footnote 81 The other is Muslims’ taking the law into their own hands by guarding mosques and homes at night, apparently using weapons such as knives, sticks, slingshots, and stones. Since one of the main targets of rioters was mosques, Muslims who would defend mosques hoarded small weapons within mosque compounds or inside mosques, leading to accusations that mosques are enemy bases and arrests by authorities, as stated above.

Looking at the third accusation that mosques have been illegally built, it remains highly contested until the time of writing, compared to the first two accusations, which are not heard of any more, especially after the NLD came to power and started taking action in 2017 against Ma Ba Tha and, by extension, its extensive networks across the country. Framed in terms of legality or lawfulness, this accusation is particularly interesting for law-and-society researchers because people in Myanmar in transition seemed to have developed a fetish for law, legality, and the rule of law in the country,Footnote 82 which had not had a functioning rule of law for decades.Footnote 83 Importantly, for anti-mosque extremists, the issue of (il)legality is less of an administrative-law matter than it is of a historically contextualized understanding of lawfulness. They argue that many mosques came to acquire legal existence during the British colonization, especially in cities such as Yangon. There are important exceptions such as several tens of mosques in Mandalay built during the time of the last Burmese kings before the colonization. Therefore, the historical lawfulness of Mandalay mosques is not contested as much as that of most other mosques in other cities and towns built during the British colonization.

In the eyes of anti-mosque extremists, most of the mosques that now exist on the soil of Buddhist Myanmar were built in a non-contractual way without the explicit permission of indigenous or native Buddhists. The terms of the narrative are framed on the basis of not only positive law, but also a discourse of ethno-religious rightfulness set in a post-colonial context. For these Buddhists, everyone or every group that existed in pre-colonial Burma is native, indigenous, rightful, legitimate, and lawful, whereas those that came to exist in colonial Burma and independent Burma/Myanmar is foreign, non-native, ungranted, non-legitimate, unlawful, or even illegal. In more nuanced terms, for anti-mosque Buddhist nationalists, mosques built during colonization may be legal because they have legal documents granted by the British colonial government, but these mosques are not legitimate. They are legal in strict literal terms, but they should not have been built in the first place.

In the past seven years, anti-mosque vigilante extremists and activists have actually broadened their net by not only destroying, burning, and closing down illegal mosques, madrasas-cum-mosques, buildings allegedly constructed as mosques, and homes being used as mosques, but also pressuring authorities not to reopen closed mosques. Now, we turn to a selection of such cases from 2012 through to mid-2019. It must be noted that this article does not discuss cases of the destruction and burning-down of existing mosques in riots from 2012 through to 2014, where their legality was not questioned. It is also noteworthy that the complete or partial destruction and closing-down of mosques and alleged mosques have occurred during both administrations in Myanmar in transition—the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) government (2011–16) and the NLD government (2016–).

6. Five illustrative cases

6.1 Cases of illegal mosques

A number of existing mosques, legal or otherwise, became the target of anti-mosque vigilantism. Northern Rakhine state is where most of the Rohingya live—people who are adamantly designated by the Myanmar government as those whose citizenship still needs to undergo scrutiny and recognition at best, or as illegal Bengali migrants who entered Myanmar from neighbouring Bangladesh at worst. The most illustrative and extensive case of illegal mosques is, therefore, found in Rakhine state. Alleging that about 3,326 illegal buildings including 12 mosques and 35 madrasas exist in Maungdaw and Buthidaung where the Rohingya are most concentrated in, Rakhine state-security and border-affairs minister Colonel Htein Lin said in September 2016: “We are working to bring down the mosques and other buildings constructed without permission in accordance with the law.”Footnote 84 But, due to international sensitivities implicated because the Rohingya are involved, the Rakhine state government later said there is no plan yet to actually demolish these buildings, including the mosques and madrasas referred to.Footnote 85 That (il)legality was invoked by Htein Lin showed the extent of the anti-mosque/madrasa narrative couched in law. On 21 November 2016, the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture announced that village officials with the General Administration Department of Shwegyin township in Bago Region orally ordered the closure of three mosques in three villages in the township by stating that the mosques were illegally built without approval.Footnote 86 In both instances in Rakhine state and Bago Region, authorities themselves were anti-mosque agents by alleging that the mosques in question were illegally built and must be demolished or sealed. When authorities are involved, it does not lead to the mobbish demolishing and burning-down of illegal mosques.

In contrast, on 1 July 2016, a Buddhist mob of about 500 people burnt down a mosque or prayer hall in Lone Khin village in Hpakant township in Kachin state, shouting: “Victory! Victory!”Footnote 87 A month later, the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture issued an 11-point statement on 3 August that effectively justified the arson as if it stemmed from the illegality of the mosque that included four buildings.Footnote 88 It stated that the mosque was built in 2014 by Sonny Thein, a Muslim engineer who worked in the project to build Uru Creek Bridge. Local monks and Buddhists complained to authorities after they discovered in March 2016 that Muslims nearby were using it as a prayer space, forcing township authorities to ask mosque trustees on 25 and 28 June to demolish all four buildings. The trustees only agreed to demolish three buildings themselves, saying that, because the prayer hall is a private donation, they could not demolish it, but the state may choose to do so. While it was still under negotiation between the authorities and the trustees, the Buddhist mob burnt all four buildings down.Footnote 89 Although the Ministry said it would punish both the extremists and the Muslims related to the mosque, the issue of illegality obviously came to the fore. Apparently to show itself as a nondiscriminatory state body and to contend that Muslim religious buildings alone were not targeted, the ministry, interestingly, claimed that hundreds of illegal monasteries would also be demolished across Myanmar.Footnote 90

6.2 Cases of madrasas being used as or reconstructed into mosques

On 22 November 2013, about 120 monks protested against the repair work of a madrasa in Thingangyun township in Yangon, which was about 20 years old. The repair work was done with the permission of Yangon City Development Committee, but the monks claimed that the madrasa had significantly grown in size and it had dedicated prayer space. U Pyinnya Zawta, one of the monk protesters, said:

We asked [the authorities] to stop or demolish [the construction] according to rules and regulations. But, they [the authorities] did not do what they should have. If they [the authorities] continue to allow [the reconstruction], we monks will create nationwide protests because the Sangha and the people are not satisfied with many things.Footnote 91

It apparently forced the Yangon-region government to order the madrasa reconstruction to stop. Probably due to the residence of a sizeable Muslim community and the existence of several Buddhist religious networks, Thaketa township in Yangon has been an area of significant anti-Muslim and anti-mosque extremism in recent years. The first anti-madrasa incident in Thaketa happened in April 2013 when extremists protested against the repair and construction work being done to a madrasa and alleged that a mosque was being constructed in its place. After some initial destruction by a mob, authorities sealed the madrasa. Most interestingly, by invoking the law as if the issue was one of law alone, a prominent leader of the 88 Generation (Peace and Open Society), Ko Ko Gyi, who acted as mediator between extremists and Muslims, said: “Now the building [madrasa] has been sealed. Nothing can be done in relation to the building. [People] must follow relevant laws.”Footnote 92

Madrasa education for Myanmar Muslim children is part-time and usually conducted from the late afternoons until the evenings—when two of five daily prayers are offered (Maghrib (sunset prayer) and Isha (evening or night-time prayer))—at mosques, stand-alone madrasas, or madrasas attached to mosques. Although students at mosques and at madrasas attached to mosques learn and offer prayers at the mosques, students at stand-alone madrasas have no other option but to learn how to pray and offer prayers at their own madrasas together with teachers. Also, because Muslims are required to perform ablution before prayers, madrasas have designated a space for ablution. These practices of having an ablution space and children and teachers’ praying at madrasas apparently made anti-mosque extremists suspicious that a madrasa is, in fact, a mosque, whether this suspicion was sincere or not. This accusation became more convincing or forceful because many Muslims in Thaketa township in Yangon use madrasas for communal prayers. For example, upon the forced shuttering of two madrasas in April 2017, a Muslim man said: “It’s our mosque as well as our school.”Footnote 93 There are such eight stand-alone madrasas in Thaketa. Hence, when, in October 2015, extremists complained to local authorities that children were not only learning Islam, but also praying, the authorities banned childrens’, and adults’ by extension, praying at all those madrasas.Footnote 94

However, praying at madrasas did not seem to stop, making “local” Buddhist neighbours notice it. These neighbours might have reported it or at least talked about it among themselves. Although Muslims used to pray at madrasas without controversy before the transition and the post-2012 religious violence, it became highly noticeable and suspicious amid the rise of anti-mosque extremism. Therefore, the most recent madrasa drama ensued two years later. On 28 April 2017, a 100-strong “non-local” Buddhist mob of monks and people came over and pressured the Thaketa township authorities to shutter Madrasa No. 1 and Madrasa No. 9 in the Anawmar 1 quarter again by alleging that prayers are held and offered there. The authorities gave in to the demand of those vigilantes again by locking the two madrasas.Footnote 95 The political timing of this conflict is important because the mob was only created in the afternoon after a court hearing of a case that involved anti-Muslim extremist monks and people such as the chair and secretary of the Patriotic Myanmar Monks Union U Nyarna Dhamma and U Thu Seitta, the head monk of Magway Monastery Sayadaw U Parmaukkha, and nationalist activist Ko Win Ko Ko Latt.Footnote 96 Again, the comment made by a lower-house representative of Thaketa township, Wai Phyo Aung, after inspecting the madrasas, such that he must have seen the ablution space, prayer mats, and so on inside, invokes law and legality: “I think everybody has the rights and freedom to practice their faith. But there need to be steps to ensure that religious buildings are built in accordance with the instructions and procedures of religious law.”Footnote 97

6.3 Cases of buildings allegedly constructed as mosques

The most concrete and illustrative evidence on the extent of anti-mosque extremism in Myanmar in recent years is the demolition by authorities of a two-storey building being constructed by a non-local Buddhist in Kyaukpadaung township in Mandalay region. There is not a single Muslim dweller in Kyaukpadaung, whereas there are 291,540 Buddhists.Footnote 98 Aye Khaing, elected representative of Kyaukpadaung at the Mandalay region Parliament, expressed his disbelief: “I cannot think of how the rumour started in a town that takes pride in the fact that there is no believers of religions [read: Muslims] other than Buddhism.”Footnote 99 Likewise, Zaw Htay, spokesperson of State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s Office, echoed: “Kyaukpadaung is a town without any mosques and mosques are not allowed to be built. The owner of the house is a Buddhist.”Footnote 100 Despite the fact that there is no Muslim dweller and the building in question is Buddhist-owned, the 1,000-strong mob who gathered in front of the building on 27 July 2017 after hearing a rumour that a mosque was being built in the Muslim-free town apparently succeeded in having local authorities demolish it by heavy machinery.Footnote 101

The Buddhist owner was a movie director and later admitted that he had failed to seek official permission for the construction. What is equally as interesting as the authorities’ demolishing of the building as they were told by extremists is the root of the rumour. To cite the owner:

I am building my house as a closed structure because I want to use it as a studio. A hole was dug downstairs to prop up the studio and it was alleged to be an ablution space like those found in mosques.Footnote 102

It shows the lack of political will and action and the weakness of the authorities, at least on the ground, even when the accused is a Buddhist, letalone a Muslim, and a “mosque,” actual or rumoured, is involved.

The second incident, which naturally involved a Muslim, occurred a few months after the NLD government had come to power. The incident occurred in Thuye Thumain village in Waw township in Bago Region.Footnote 103 A Muslim villager by the name of Abdul Rashid was constructing a building as storage for his shop and a school for Muslim children, but his Buddhist neighbours alleged that the construction was a “mosque” and reported it to local authorities a month earlier. But a quarrel between the Muslim and a female Buddhist neighbour on 23 June 2016 eventually led to the destruction of the building in question, an existing mosque in the village, the man’s house, and other Muslim homes by Buddhist vigilantes from neighbouring villages after learning about the quarrel on Facebook, according to Bago Region Chief Minister Win Thein.Footnote 104 Rashid was also stabbed and beaten by the mob.Footnote 105

6.4 Cases of private homes and public space being used as mosques

In Ramadan 2017, which fell from late May until late June, having no mosques nearby apparently made about 4,000 Muslims in Thiri Mingalar quarter in Meiktila choose to pray communally on their own in their quarters from late May 2017 onwards in Ramadan. It seemed to provoke not extremists, but local authorities who ordered Muslims to stop praying communally.Footnote 106 Most importantly, those Muslims prayed without official approval, making them highly susceptible to action against them.

As usual, in Thaketa in Yangon, after two madrasas were shuttered by a Buddhist mob on 28 April 2019,Footnote 107 about 50 Muslims nearby, at least partially in protest, had the courage to offer Ramadan prayers in the street on 31 May. The next day, the Thaketa township administration issued an order that Muslims must not illegally pray in public and provoke public disorder.Footnote 108 On 2 June, the Yangon-region government sued Muslim men who organized the prayer.Footnote 109 It led to the issuance of more orders on 22 and 23 August in townships in Yangon, including Dagon, Hlaing, and Dawbon, against communal Ramadan prayers at places other than mosques.Footnote 110 Notably, in April 2018, namely one year later, seven Muslim men who organized the Thaketa Ramadan street prayer were jailed for three months.Footnote 111 Again, Thaketa Muslims had held prayers without official approval.

In contrast, although the Yangon-region government failed to control anti-mosque vigilantes in 2017, it officially allowed Muslims in South Dagon township to hold communal Ramadan prayers from 6 May until 7 June in 2019 at three Muslim houses in Quarters No. 26, 64, and 106, respectively, in the township.Footnote 112 But having the official permission did not allow Muslims to pray in peace and, on 15 May, a vigilante mob of 150 people roamed around in the township and pressured Muslims to stop praying at the sites and sign an agreement. Mob leader Michael Kyaw Myint clamoured: “This is for our race and religion! We members of the public will tear down the Muslim mosque here in this township.”Footnote 113 He also alleged: “If the government cannot control illegal mosques, we will!”Footnote 114 Authorities did not do anything as usual, but the township administrator sued Michael Kyaw Myint and another man two days later under the Penal Code.Footnote 115 Most notably, on 17 May, the three Ramadan sites were reopened by authorities, in stark contrast to what they did before in Thaketa and elsewhere.Footnote 116 Michael Kyaw Myint and his partner in crime went into hiding but were arrested in June 2019 and the case is pending.Footnote 117

6.5 Cases of closed mosques that were not allowed to reopen

Several mosques, whose number is not publicly known and which were partially destroyed or left untouched during the violence but had to close their doors regardless, have not been allowed yet by authorities to reopen. Facing the most severe interreligious riot outside Rakhine state in recent years, Meiktila remains fragile and rumours about mosques abound. For example, in late April 2016, at the very beginning of the coming-to-power of the NLD government, rumours of Muslims’ protests about closed mosques spread, forcing Muslims and authorities to emphatically deny the rumours.Footnote 118 By June 2018, only five out of 13 closed mosques in Meiktila, whose doors were sealed during the violence in March 2013, had been reopened.Footnote 119 Muslims in rural Meiktila had the courage to re-enter a closed mosque in a Hta Mon Kan village tract, again provoking authorities to close the doors of the mosque in June 2018.Footnote 120 Notably, there were no visible, active movements by vigilantes against mosques. So, whether anti-mosque extremists pressured authorities or played a role behind the scenes is unclear, but it is not wrong to assume that authorities acted against Muslims and mosques with concerns that allowing Muslims to reuse closed mosques might provoke extremists.

But, on several other occasions, vigilante extremists actively campaigned against the reopening of closed mosques or the rebuilding of destroyed mosques. In early November 2018, Buddhist vigilantes in Monyo township in Bago Region, where an anti-Muslim violent episode in March 2013 had destroyed a mosque, launched a signature campaign with the permission of authorities against reports that the government of Myanmar may allow reconstruction of the mosque upon finishing a check.Footnote 121 Hundreds of Buddhist residents signed the campaign, arguing that the mosque might provoke violence.Footnote 122 In addition to questionable plausibility of that popular Buddhist claim, what is more interesting and relevant, from a law-and-society perspective, is that the authorities utterly failed to do anything against such provocative statements that correlated a mosque with violence, even permitting the signature campaign in the first place.

Another case involved two mosques in Chauk township in Magway region, which were burnt but not entirely destroyed during violence in 2006, but have remained closed for about 13 years to date. The case occurred in March 2019, during the time of the NLD administration. Most importantly, they are legal mosques, but their legality has been taken away by extremist pressures, effectively making their legality or lawfulness void. It also shows a new feature of anti-mosque activism in Myanmar that uses the voting power of Buddhist neighbours in rejecting the existence of mosques as in the aforementioned example of the mosque in Monyo township, though it is not officially written into laws, rules, regulations, etc. yet, as it is only in the 2006 joint ministerial decree on procedures to build places of worship in Indonesia.Footnote 123 The way in which the authorities responded this time was even more “innovative” in how they disobeyed the rule of law because they themselves organized two voting sessions in the No. 9 and No. 11 Quarters in Chauk, in which 536 (Buddhist) voters out of more than 700 from the two quarters, unsurprisingly, overwhelmingly voted “No.”Footnote 124 The voting was followed by the spread of fake news on Facebook in June that NLD-appointed Magway region Chief Minister Dr Aung Moe Nyo would allow new mosques and take action against those who objected.Footnote 125

7. Conclusion

This article has shown how anti-mosque vigilante extremists in Myanmar justify attacking, destroying, and burning down or demanding the closure of mosques, madrasas, and Muslim prayer space across the country in the past six years by using a narrative of illegality and how that narrative has been endorsed and acted upon by authorities as well. The narrative of illegality constitutes legal violence, and it underlies the consequent mobbish and official action against targets that vary from illegal mosques to madrasas being used as mosques to closed mosques. The state, as usual, and the Buddhist majority, increasingly so, have dictated what religious practice and worship an individual Muslim or a group of Muslims may perform, where, and when. By invoking illegality, the state stands ready to punish Muslims who dare to disobey the orders of the state while the extremist mob waits to act once Muslims err. In other words, legal violence is committed by both the state and non-state actors acting as if they are upholding the law that arbitrarily and murkily decides or fails to decide whether a Muslim religious building or forms of Muslim group worship in private premises or public space is legal.

Political timing seems to have played a significant role in the emergence of legal violence in Myanmar in the form of anti-mosque/madrasa-cum-mosque narrative and mobbish attacks, as well as in influencing state action because they coincided with a bumpy political transition from military dictatorship to a more democratic form of government. That said, singling out the transition as the cause behind anti-mosque vigilante extremism in Myanmar is not entirely accurate because actors and groups—ranging from authorities, to ideologue monks, and to grassroots vigilantes—are all deeply involved and implicated in instances of attacking and destroying illegal mosques, madrasas being used as or reconstructed into mosques, and buildings being constructed as mosques, each of the aforementioned actors and groups taking punitive measures against Muslims for the use of private homes and public spaces for prayers, and continuously shuttering closed mosques.

The article shows the murky nature of so-called law and legality when a government and a community, both of which belong to a religious majority, find and use loopholes in the law to discriminate and attack a religious minority. What is written in the law, what is omitted (intentionally or not), and what is actually implemented by authorities have apparently created those loopholes in the case of Myanmar Muslims and their religious worship. It also highlights how vigilante activism may be tolerated, if not directly encouraged, by authorities and may lead to the lack of protection of religious minorities by authorities. The targeting of mosques and places of worship clearly violates the religious freedom of Muslims in Myanmar. Places of worship are critical to the freedom to manifest one’s religion and to worship in community. The building of places of worship and the ability to maintain them have been considered crucial to the freedom of religion, which is stated in General Comment No. 22 of Article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Notably, Myanmar plans on signing the covenant in a few years’ time.

Despite the nature of this article as a single-country study, it has broad implications because many religious minorities across the world, such as Christians and Ahmadis in Indonesia, face similar legal restrictions relating to building, maintaining, and using places of worship and vigilante attacks, where the language of (il)legality is apparently invoked. Likewise, the way in which Myanmar authorities have failed Muslims in the country is also strikingly similar to the way in which, for example, Indonesian authorities have dealt with Ahmadis and Christians there.

In particular, by highlighting legally violent ways of restricting and closing down the use of private premises and public space for Muslim religious worship in Myanmar, this paper has added legal violence as a new layer or dimension to the broader literature on religious, religiously motivated, or religiously expressed violence in Myanmar and other places. Thus, the Babri Masjid affair—which recently saw the Supreme Court of India reach a “legal” verdict upon the (il)legality of the Masjid torn down on 6 December 1992 that decided on 9 November 2019Footnote 126 that a Hindu temple could be built in the site—could be seen and theorized as state and non-state legal violence. Likewise, legal violence may be used in studying cases of the forced closure of Christian churches and Ahmadi mosques in Indonesia.

Acknowledgements

The earlier version of the paper was presented at the 14th Asian Law Institute (ASLI) Conference entitled “A Uniting Force? Asian Values and the Law” held in Quezon City, Metro Manila, the Philippines on 18 and 19 May 2017. The author is grateful to the Centre for Asian Legal Studies at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore for funding his attendance at the conference and for the postdoctoral fellowship at the centre where he drafted the paper for the conference and revised the paper for publication. The author is also grateful for Professor Kevin Y. L. Tan of the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore for giving feedback on the draft paper.