Introduction

Archaeological studies have long focused on understanding the dynamics of prehistoric economies, as the production, distribution and consumption of resources are embedded within larger social and political processes. Geochemical analyses of ceramics have been applied widely across the world to understand how these processes affected the earliest ceramic economies. In Mesoamerica, studies have focused on regional patterns of production and exchange of decorated ceramics and their implications for the development of the first complex Mesoamerican societies (e.g. Neff & Glascock Reference Neff and Glascock2002; Blomster et al. Reference Blomster, Neff and Glascock2005; Neff et al. Reference Neff, Blomster, Glascock, Bishop, Blackman, Coe, Cowgill, Diehl, Houston, Joyce, Lipo, Stark and Winter2006; Callaghan et al. Reference Callaghan, Pierce and Gilstrap2018).

Among various analytical approaches, neutron activation analysis (NAA) has become the primary method for sourcing archaeological ceramics because of straightforward sample preparation, high analytical precision and multi-element analytical capacity (Bishop Reference Bishop2014; Minc & Sterba Reference Minc, Sterba and Hunt2016). The results of NAA reflect the elemental composition of ceramic pastes, with distinct groups of ceramics determined by common trace elements (Harbottle Reference Harbottle1976; Bishop & Neff Reference Bishop, Neff and Allen1989; Glascock Reference Glascock and Neff1992; Neff Reference Neff, Cilberto and Spoto2000). The production locale of ceramics (and their pastes) can then often be linked to specific geographic locations based on raw material types and the frequency of ceramic samples within a particular community (i.e. criterion of abundance; Weigand et al. Reference Weigand, Harbottle, Sayre, Earle and Ericson1977; Bishop et al. Reference Bishop, Rands and Holley1982).

Despite the popularity of NAA in Mesoamerican archaeology, compositional studies have largely neglected ceramic production and exchange among the Preclassic lowland Maya (c.1200 BC–AD 300). This critical period of socio-economic transition witnessed the development of sedentary village life, complex economic networks and an increased reliance on maize agriculture, along with the adoption of ceramic technology and the specialised craft required for ceramic production. To examine these changes, Callaghan and colleagues (Reference Callaghan, Pierce, Kovacevich and Glascock2017a & Reference Callaghan, Pierce, Kovacevich and Glascockb, Reference Callaghan, Pierce and Gilstrap2018) have focused on defining the geochemical composition of Middle Preclassic ceramics from Holtun, in the Petén region of north-central Guatemala. Their results identified the local production of utilitarian ceramics, as well as fine-paste Mars Orange serving vessels, which were probably manufactured in and imported from the Belize Valley. At K'axob in northern Belize, Angelini (Reference Angelini1998) also used NAA combined with petrographic analyses to investigate local ceramic production through the late Middle and Late Preclassic periods.

Here, we use ceramic compositional data from the site of Cahal Pech, Belize (Figure 1), to examine the relationship between lowland Maya ceramic economies and increasing social complexity during the Preclassic period (Figure 2). In the largest NAA study of Preclassic Maya ceramics to date, a total of 192 sherds of utilitarian and fine ware vessels were sampled to identify diachronic shifts in ceramic usage. These sherds originated from radiocarbon-dated contexts in the monumental centre and two peripheral residential groups at Cahal Pech. All sherds were identified to type:variety-mode classification according to standard classifications for the Belize Valley (Gifford Reference Gifford1976; Awe Reference Awe1992; Sullivan & Awe Reference Sullivan, Awe and Aimers2013). Statistical analyses of NAA data identified four primary compositional groups corresponding to diachronic changes in production patterns.

Figure 1. Map of Belize Valley showing the location of Cahal Pech and other major Preclassic sites; inset shows Belize Valley within the Maya lowlands (map by C. Ebert).

Figure 2. Cahal Pech chronological periods and associated ceramic complexes (figure by C. Ebert).

The Early Preclassic Cunil ceramic assemblage is compositionally distinct from previously analysed Maya lowland ceramics, suggesting local production and consumption of this pottery type by the earliest occupants of Cahal Pech and perhaps of the broader Belize Valley. By the Middle Preclassic period, ceramics associated with elite monumental architecture are compositionally distinct from those found in peripheral residential settlements—although both were produced locally. Comparisons with contemporaneous assemblages from Petén, Guatemala, also reveal that Mars Orange finewares were produced and exported from the Belize Valley throughout the Maya lowlands. These data indicate that socio-political connectivity facilitated economic interactions between communities, possibly allowing for groups to underwrite status and authority within emergent political economies of the Belize Valley. Similar to ceramic studies conducted elsewhere, including Europe, Asia, the Near East and South America (Blackman et al. Reference Blackman, Stein and Vandiver1993; Hayashida Reference Hayashida1995; Day et al. Reference Day, Kiriatzi, Tsolakidou and Kilikoglou1999; Falabella et al. Reference Falabella, Sanhueza, Correa, Glascock, Ferguson and Fonseca2013; Grave et al. Reference Grave, Stark, Ea, Kealhofer, Han and Tin2015), our results highlight the precision of NAA and its value for the study of the development of ceramic craft production and specialisation within a developing complex society.

Archaeological background

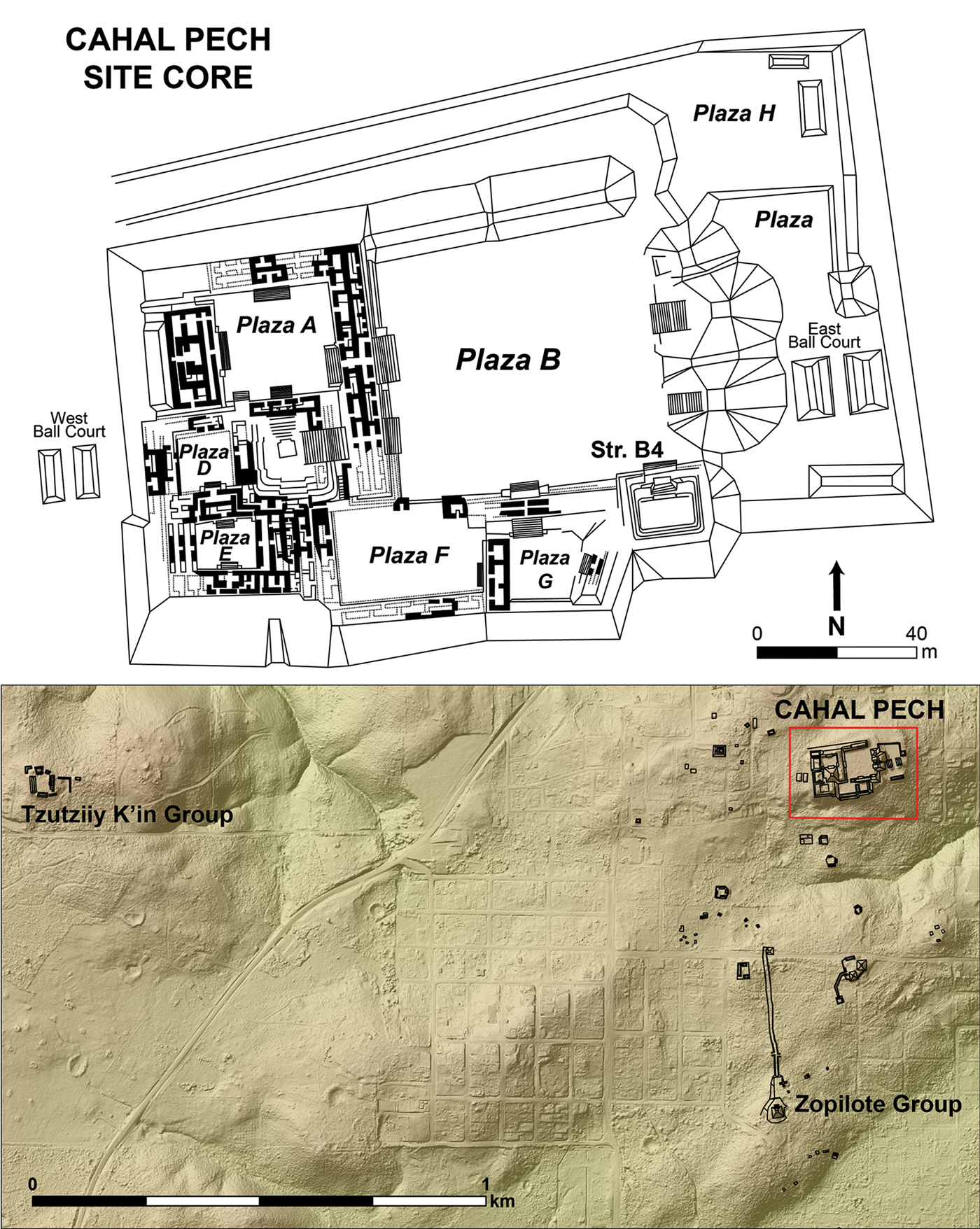

Cahal Pech is a medium-sized Maya centre in the Belize Valley, located approximately 2km south of the confluence of the Macal and Mopan Rivers (Figure 3). Radiocarbon dates from the site's centre indicate initial settlement during the Early Preclassic period, c. 1200 cal BC, in the form of a small farming village of relatively egalitarian and economically autonomous households (Awe Reference Awe1992; Awe & Healy Reference Awe and Healy1994; Ebert et al. Reference Ebert2017; see Table S1 in the online supplementary material (OSM) for radiocarbon dates). Early occupation was associated with Cunil-complex ceramics, which include unslipped utilitarian wares, such as large jars, bowls and gourd-shaped tecomates (Sullivan & Awe Reference Sullivan, Awe and Aimers2013; Sullivan et al. Reference Sullivan, Awe, Brown, Brown, Bey and III2018). The Cunil complex also includes slipped bichrome serving vessels incised with symbols that connect them to widespread Mesoamerican iconography (Figure 4; Garber & Awe Reference Garber and Awe2009). Excavations at peripheral residential settlements and at other Belize Valley sites, such as Xunantunich, Actuncan and Blackman Eddy, provide further evidence for Cunil-phase occupation within small village settlements (Brown Reference Brown2003; Garber et al. Reference Garber, Brown, Awe, Hartman and Garber2004; LeCount et al. Reference Lecount, Mixter, Simova, LeCount and Mixter2017).

Figure 3. Cahal Pech centre (top) and peripheral settlements examined in this study (bottom; maps by C. Ebert).

Figure 4. Incised Cunil-complex ceramics. From left to right: Baki Red Incised with k'an cross, Kitam Incised with flamed eyebrow motif and refit Zotz Zoned Incised vessel (photographs by J. Awe).

Early Middle Preclassic (900–600 cal BC) population expansion and economic growth across the southern lowlands was accompanied by the adoption of more standardised Mamon-tradition ceramics, which are characterised by monochrome, red-slipped pottery (Willey et al. Reference Willey, Bullard, Glass and Gifford1965; Gifford Reference Gifford1976; Rice Reference Rice2015). The contemporaneous Kanluk ceramic complex at Cahal Pech primarily comprises coarse-paste utilitarian ceramics and fine-paste Mars Orange wares, the latter including red-slipped Savana Orange and Reforma Incised types (Figure 5; Gifford Reference Gifford1976; Awe Reference Awe1992). The construction of large ritual architecture and elaborate residences at Cahal Pech first began between 900 and 650 cal BC, suggesting the development of socio-economic differentiation within the community, and the formalisation of religious institutions (Awe Reference Awe1992; Horn Reference Horn2015; Peniche May Reference Peniche May2016; Ebert et al. Reference Ebert, Peniche May, Culleton, Awe and Kennett2017).

Figure 5. Mars Orange serving vessels from Cahal Pech including large dishes and a chocolate pot spout (photographs by J. Awe).

Cahal Pech and other Belize Valley centres experienced settlement growth during the end of the late Middle Preclassic period (600–300 cal BC; Garber et al. Reference Garber, Brown, Awe, Hartman and Garber2004; Brown et al. Reference Brown, McCurdy, Lytle and Chapman2013). This study includes samples from two settlements peripheral to Cahal Pech: the Tzutziiy K'in and Zopilote Groups. Located 1.8km west of Cahal Pech, the Tzutziiy K'in Group was initially settled as a single farming household by c. 300 cal BC. Within this settlement group, evidence for social stratification emerges after 350 cal BC in the form of differential house sizes. This was followed by the construction of multiple masonry platforms in the group's main plaza, which probably functioned as domestic architecture for a higher-status family (Ebert et al. Reference Ebert, Culleton, Awe and Kennett2016). At the Zopilote Group, located approximately 0.75km south of the centre of Cahal Pech, the earliest occupation is associated with materials from the Early Preclassic period (Ebert et al. Reference Ebert, Peniche May, Culleton, Awe and Kennett2017). During the Late Preclassic period, several low masonry platforms were constructed. These were associated with the Xakal ceramic complex (300 cal BC–cal AD 300) and probably served as public temple buildings associated with nearby domestic structures. The contemporaneous construction of large public plazas and monumental temples containing elaborate tombs within Cahal Pech's monumental centre signals the development of a royal lineage (Awe Reference Awe1992; Garber & Awe Reference Garber and Awe2009; Ebert Reference Ebert2017). Diagnostic ceramics and direct dates from burials and several large house groups suggest that this pattern of social, economic and spatial growth occurred throughout the hinterlands of Cahal Pech during the Late Preclassic period (Ebert et al. Reference Ebert, Culleton, Awe and Kennett2016, Reference Ebert, Peniche May, Culleton, Awe and Kennett2017; Awe et al. Reference Awe, Hoggarth, Aimers, Freidel, Chase, Dowd and Murdock2017; Ebert Reference Ebert2017).

Materials and methods

Sample selection

To document diachronic changes in ceramic production and consumption at Preclassic Cahal Pech, we sampled common diagnostic ceramics for NAA. Samples were restricted to radiocarbon-dated contexts to facilitate comparisons. Sherds were first identified by type:variety-mode classification, according to standard classifications for the Belize Valley (Gifford Reference Gifford1976; Awe Reference Awe1992; Sullivan & Awe Reference Sullivan, Awe and Aimers2013). A sample of 192 sherds representing all type:varieties was then chosen, based on preservation and type. When available, multiple specimens from each ceramic type and context were analysed in order to capture assemblage diversity.

A total of 125 ceramics from Structure B4 and Plaza B within Cahal Pech's centre, previously radiocarbon-dated to the Cunil (n = 47) and Kanluk (n = 78) contexts, were included in the sample (see the OSM & Table S2). While the Early Preclassic Cunil contexts suggest the remodelling of a series of superimposed living surfaces supporting wattle-and-daub domestic structures (Awe Reference Awe1992; Peniche May Reference Peniche May2016), Middle Preclassic Kanluk contexts display evidence for the construction of several large masonry platforms that probably functioned as public buildings and high-status residences (Horn Reference Horn2015; Peniche May Reference Peniche May2016). To assess this transition, samples of at least 20 per cent of every ceramic type within each directly dated context were sought.

Samples were also chosen from Middle and Late Preclassic contexts at two peripheral residential groups: the Tzutziiy K'in (n = 40) and Zopilote (n = 27) Groups. Zopilote sherds originated from domestic late facet Kanluk and early/late facet Xakal contexts of Structure 1 (c. 600 cal BC–cal AD 300; Ebert Reference Ebert2017), which were later covered by a series of Late Preclassic temple platforms. Samples from Tzutziiy K'in derive from domestic contexts at Structures 2 and 3, and date to the early/late facets of the Late Preclassic Xakal ceramic complex (300 cal BC–cal AD 300; Ebert Reference Ebert2017). Although Preclassic household contexts often possess few diagnostic ceramics, our samples included all diagnostic sherds from directly dated contexts, comprising both utilitarian (bowls and jars) and non-utilitarian wares that may have functioned as serving vessels.

NAA preparation and data interpretation

All ceramic samples were prepared for NAA using standard procedures at the Archaeometry Laboratory at the University of Missouri Research Reactor (MURR) (Glascock Reference Glascock and Neff1992; Neff Reference Neff, Cilberto and Spoto2000). Multivariate statistical routines, such as cluster analyses, principal component analyses and Mahalanobis distance, were used to identify compositional groups, in coordination with visual inspection of bivariate elemental plots depicting the results of NAA and the calculation of mean, standard deviation and coefficient of variation for each element per group. These methods were combined to identify seven distinct compositional groups in the Cahal Pech ceramic sample (Figure 6). Finally, a canonical discriminant analysis was applied to the identified groups to define the primary dimensions of chemical variation.

Figure 6. R-Q Mode biplot of the sample on principal components 1 and 2.

Twenty-two sherds spread across context locations (elite vs non-elite) were left unassigned to any compositional group. These represent ceramics from unknown source locations, have unique compositions (‘paste recipes’), or are similar to more than one compositional group. The Cahal Pech sample was also compared to archived data from previous NAA analyses conducted by MURR (n>12 000) using multivariate Euclidian distance to identify similarities with other individual specimens and identified geochemical compositional groups in Mesoamerica (MURR Archaeometry Laboratory Database n.d.).

Results

The Cahal Pech ceramics divide into seven geochemical compositional groups (Figure 7). The four largest groups (B, C, D & G) correspond generally with type:variety classifications from different temporal and spatial contexts (Figure 8 & Table 1). Three smaller groups were also identified (A, E & F), although they collectively comprise a minor portion of the total analysed sample (4 per cent).

Figure 7. Bivariate plot of neutron activation analysis samples based on discriminant functions #1 and #2; ellipses represent 90 per cent confidence of group membership (figure by D. Pierce).

Figure 8. Frequency seriation of compositional groups with samples n>3 showing correspondence with type:variety classifications from site-core and settlement contexts (figure by C. Ebert).

Table 1. Distribution of Cahal Pech compositional groups identified by NAA for each chronological period and ceramic complex. Early facet (EF) and late facet (LF) components of ceramic complexes listed when present.

Group A consists of two Cunil-phase sherds of an unspecified type. These ash-tempered sherds share stylistic features with Huetche White ceramics from the Pasión region of western Guatemala, approximately 135km south-west of the Belize Valley (Sabloff Reference Sabloff1975: 53–55). Compositionally, however, they more closely resemble pottery from the Pacific Coast of Mexico and Guatemala. Group B (n = 34) features elevated levels of sodium and potassium, and contains all other ash-tempered sherds included in this study, along with some exhibiting fine-texture calcite pastes. Many of the finer Cunil ceramics in this group, such as the Baki Red Incised, Mo Mottled, and Kitam Incised types, are decorated with dull slips and post-slip incision. Euclidean distance searches indicate that these early Cahal Pech specimens are compositionally unique from all archived Maya region samples in the MURR database.

Groups C and D contain samples attributed most frequently to the late facet Kanluk ceramic complex (750–300 cal BC). Group C (n = 13) possesses the most intra-group chemical variability in our sample, exhibiting higher levels of cobalt and cerium and a greater range of manganese compared to other compositional groups. Group C ceramics are primarily Mars Orange wares (92 per cent Savana Orange and Reforma Incised types, see Gifford Reference Gifford1976: 73–76) and were distributed between late Middle Preclassic Cahal Pech site-core (62 per cent) and settlement contexts at the Tzutziiy K'in and Zopilote Groups (38 per cent).

Group D is the largest compositional group (n = 71) identified at Cahal Pech and is geochemically distinguishable based on elements including calcium and potassium. Most specimens (87 per cent) come from the site core and are attributed to the Cunil and Kanluk complex, while a smaller number of peripheral settlement samples date to the Late Preclassic period. This group is dominated by unslipped coarse utilitarian pottery, such as Sikiya and Jocote types (57 per cent), but also contains high frequencies (37 per cent) of Mars Orange (Savana Orange type) wares. The remaining six per cent of group D includes Ardagh Orange (n = 7), Sierra Red (n = 1) and cream slipped sherds of an unknown type (n = 3). Comparison to the MURR database indicates a compositional similarity to ceramics collected from the Petén Lakes region of Guatemala and Middle Preclassic Mars Orange ceramics from Holtun, Guatemala (see Callaghan et al. Reference Callaghan, Pierce, Kovacevich and Glascock2017a & Reference Callaghan, Pierce, Kovacevich and Glascockb, Reference Callaghan, Pierce and Gilstrap2018).

Groups E (n = 2) and F (n = 3) ceramics comprise only three per cent of the total Cahal Pech sample. While both groups are compositionally distinct, they exhibit high degrees of internal variability, which indicates slightly different paste recipes for each sherd. Groups E and F are found in both site-core and peripheral settlement contexts, and comprise Joventud Red sherds from the Kanluk ceramic complex.

The second largest group in the assemblage, group G (n = 45), is homogeneous and characterised by high levels of calcium and little variation in potassium. Group G comprises approximately two-thirds of the Late Preclassic Xakal-complex (300 cal BC–cal AD 300) sherds, despite only making up 23 per cent of the total Cahal Pech sample. This indicates a preference for this paste recipe within households during later time periods. As securely dated Late Preclassic contexts are lacking in the site core, however, our sampling strategy only focused upon peripheral settlements for this period. It remains unknown how common this recipe is in ceramics from contemporaneous site-core contexts. Nonetheless, even in Middle Preclassic contexts, group G specimens are found almost exclusively at peripheral households. This contrasts with the other compositional groups, which are only rarely found in settlement contexts. Approximately 74 per cent of sherds sampled from the Tzutziiy K'in and around 65 per cent of the sherds sampled from Zopilote were assigned to group G. The most common ceramic types in group G include Joventud Red (late Middle Preclassic) and Sierra Red (Late Preclassic), with small quantities of Jocote Orange-brown and Sayab Daub Striated unslipped utilitarian wares. Finally, group G is most similar compositionally to samples from other regions of the Maya lowlands, including western Belize. Given the criterion of abundance (Bishop et al. Reference Bishop, Rands and Holley1982)—particularly considering later time periods and in household contexts—the compositional similarities between group G and other western Belizean ceramics probably indicates local production.

Discussion

This study uses NAA to explore the development of local ceramic production and the expansion of exchange networks from the Early to Late Preclassic periods at Cahal Pech. The earliest ceramics (Cunil complex) in the Belize Valley appeared within Early Preclassic domestic contexts in Cahal Pech's core (Awe Reference Awe1992; Sullivan & Awe Reference Sullivan, Awe, Brown, Brown, Bey and III2018), including large storage jars and colanders used to make nixtamal (lime-treated maize), signalling an increase in maize agriculture and the first permanent settlement in the Belize Valley (Clark & Cheetham Reference Clark, Cheetham and Parkinson2002; Ebert et al. Reference Ebert, Peniche May, Culleton, Awe and Kennett2017). We identify three compositional groups (A, B & D) containing Cunil ceramics, indicating a preference for these paste recipes during the Early Preclassic period. Group B contains the highest proportions of slipped and grooved-incised vessels, which were only found in the Cahal Pech site core.

Notably, all Cunil ash-tempered specimens in this study were also assigned to group B. Previous, limited petrographic analyses of 13 Cunil ash-tempered sherds (Sunahara Reference Sunahara2003: 123–34; Sunahara pers. comm.) suggest that the volcanic ash petrofabrics that constitute these vessels were non-local to the Belize Valley, and that vessels may have even been imported as finished products. Multivariate geochemical comparisons of the specimens examined in this study, however, indicate that group B ceramics are compositionally unique compared to other ceramics in the MURR database (>15 000 specimens). Based on these comparisons, we suggest that Cunil vessels were probably produced and distributed locally in the Belize Valley—including between Cahal Pech and other neighbouring communities. Furthermore, as the group B vessels possess incised motifs representing significant ideological meaning, they may have been intended for public display in order to communicate socio-economic differences at Early Preclassic Cahal Pech. Although Cunil vessels may have been produced in the Belize Valley using local clay tempered with non-local volcanic ash (Simmons & Brem Reference Simmons and Brem1979), ceramic pastes may alternatively be composed of local clay tempered with a local source of ash that has not yet been located, or that was exhausted in antiquity (Ford & Spera Reference Ford and Spera2007; see also Graham Reference Graham1987: 759). While additional NAA and petrographic analyses are required to test these hypotheses, the current data suggest that the ash-paste tradition for the Early Preclassic and subsequent periods probably originated in western Belize (see also Callaghan et al. Reference Callaghan, Pierce and Gilstrap2018: 824). While group B vessels (ash-tempered) were primarily non-utilitarian decorated types, the Cunil-complex sherds in group D were strictly utilitarian. Differential distribution of Cunil utilitarian and decorated serving wares between compositional groups suggests that specialised household production began during the Early Preclassic period.

During the Middle Preclassic period, population expansion and economic growth across the Belize Valley and the broader Maya lowlands were accompanied by the adoption of a more standardised Mamon ceramic tradition, characterised by monochrome, red-slipped pottery (Willey et al. Reference Willey, Bullard, Glass and Gifford1965; Gifford Reference Gifford1976). At Cahal Pech, the associated Kanluk-complex ceramic assemblage comprised primarily unslipped utilitarian ceramics and fine Mars Orange serving wares, the latter including undecorated and decorated types (Awe Reference Awe1992; Ball & Taschek Reference Ball and Taschek2003). Direct evidence for household production, including the identification of ceramic manufacturing areas or the presence of related tools (e.g. Jordan & Prufer Reference Jordan and Prufer2017) is absent. A compositional correlation between late Middle Preclassic Jocote vessels and earlier Cunil utilitarian wares, however, suggests that both types were produced locally for domestic consumption. Typological studies from elsewhere in the Belize Valley have also documented high frequencies of Mars Orange ceramics (approximately 18–50 per cent) in Middle Preclassic ceramic assemblages, suggesting production within the region (e.g. Gifford Reference Gifford1976: 73–77; Awe Reference Awe1992: 236–40; Ball & Taschek Reference Ball and Taschek2003: 195; Kosakowsky Reference Kosakowsky and Robin2012: 62).

The decreasing frequency in distribution of Mars Orange wares westward into the central Petén region of Guatemala appears to reflect its probable importation from western Belize through down-the-line exchange (Callaghan et al. Reference Callaghan, Pierce, Kovacevich and Glascock2017b, Reference Callaghan, Pierce and Gilstrap2018). Over 77 per cent of the Mars Orange sherds from Cahal Pech are assigned to compositional groups C and D (n = 27 and n = 35, respectively). These sherds derive primarily from site-core contexts associated with high-status residences and public architecture, including a series of specialised circular structures and raised masonry platforms that were probably used for public ceremonies within Plaza B (Awe Reference Awe1992; Peniche May Reference Peniche May2016). These platforms are adjacent to an eastern triadic temple structure (Structure B1), which dates to at least the late Middle Preclassic period. Functioning as a ritual architectural complex, the triadic buildings contain some of the earliest and most elaborate caches and high-status burials at Cahal Pech (Awe et al. Reference Awe, Hoggarth, Aimers, Freidel, Chase, Dowd and Murdock2017).

A comparison of the Cahal Pech Mars Orange ceramics with archived data identifies compositionally similar ceramics collected from Holtun, in the central Petén region (Figure 9). The Holtun sherds form a distinct compositional group (group 1; Callaghan et al. Reference Callaghan, Pierce, Kovacevich and Glascock2017b) and were associated with an ideologically important E-Group architectural complex in the site's civic-ceremonial centre. Although the Holtun and Cahal Pech assemblages exhibit similar paste recipes, higher frequencies of Mars Orange wares in the latter assemblage (77 per cent) vs the former (approximately 11 per cent; Callaghan et al. Reference Callaghan, Pierce and Gilstrap2018) suggest that these vessels originated in the Belize Valley (per the criterion of abundance; Bishop et al. Reference Bishop, Rands and Holley1982). As most of the Mars Orange paste wares from Cahal Pech were recovered from the site core, additional sampling from household contexts is necessary in order to determine whether these ceramic types were produced or consumed primarily by elite individuals, as well as the function of these vessels within specific contexts.

Figure 9. Bivariate plot of compositional groups compared to other Preclassic assemblages. Middle Preclassic group 1 ceramics at Holtun (Guatemala) are plotted in blue, and Late Preclassic group 1 ceramic from K'axob (Belize) are plotted in green. Ellipses represent 90 per cent confidence of group membership (figure by C. Ebert).

The Late Preclassic (early/late facet Xakal ceramic complex) period saw the local development of a distinctive style of Chicanel ceramics—characterised by waxy-finish red and black slips—at Cahal Pech and throughout the Belize Valley (Awe Reference Awe1992; Gifford Reference Gifford1976). The development of this regional style corresponds with the rapid growth of major civic-ceremonial centres and the development of shared monumental architectural traditions across the Belize Valley (Ebert et al. Reference Ebert, Peniche May, Culleton, Awe and Kennett2017). Consequentially, incipient elites could now reinforce their authority by acquiring exotic prestige items, such as non-local variants of Chicanel-style ceramics, through long-distance exchange (Awe & Healy Reference Awe and Healy1994; Peniche May Reference Peniche May2016). At Cahal Pech, a contemporaneous programme of large-scale monumental construction was initiated in the site centre (Plazas A and B), while peripheral households also expanded. Specifically, radiocarbon and architectural data document the construction of larger-scale residential buildings in at least five house groups on Cahal Pech's periphery—including the Tzutziiy K'in and Zopilote Groups—after c. 350 cal BC (Ebert et al. Reference Ebert, Culleton, Awe and Kennett2016, Reference Ebert, Peniche May, Culleton, Awe and Kennett2017).

The Xakal-complex ceramics sampled in this study derive from two of these peripheral settlement groups, Tzutziiy K'in and Zopilote. Approximately 96 per cent of these ceramics are restricted to compositional group G, which is composed primarily of Sierra Red and Sayab Daub-striated Xakal types with both utilitarian (e.g. large jars, spindle whorls) and more specialised forms (e.g. serving dishes, spouted vessels) present. While most of the later samples derive from household contexts instead of contexts associated with the Cahal Pech monumental centre, there may yet remain important implications for understanding diachronic patterns in ceramic production and consumption at Cahal Pech and beyond.

Group G paste types dominate later periods, indicating a shift in the recipe used for production for all functional categories of ceramics. As our Late Preclassic sample, however, derives primarily from peripheral Cahal Pech households, group G ceramics may alternatively represent differential production between the households and site core. The shift in paste recipes at Cahal Pech may also correspond to the adoption of Chicanel-style ceramics following the development of regional interaction networks. Additional comparisons to the MURR database indicate that nearly all of the Cahal Pech group G specimens share some compositional similarity to assemblages from the eastern Maya lowlands. When compared to the Late Preclassic assemblages of similar types (e.g. Sierra Red) produced at the site of K'axob in northern Belize (Angelini Reference Angelini1998), the Cahal Pech group G ceramics overlap significantly (see Figure 9). This may indicate broadly shared ceramic production traditions in the eastern periphery of the Maya lowlands. Additional NAA of Late Preclassic ceramics from the Cahal Pech site core and from other Maya sites could better characterise the production and consumption patterns associated with local tradition and status.

Conclusions

The reconstruction of the economic networks that facilitated the movement of key resources, craft items and shared ideological expressions of wealth within and between communities and regions has long been the focus of intensive geochemical provenance investigations in Mesoamerica and beyond (Bishop Reference Bishop2014). The analyses presented here provide new evidence concerning the structure, function and development of Preclassic-period economic systems at the Cahal Pech in the Belize Valley and provides the largest geochemical dataset of Preclassic lowland Maya ceramics to date. Although previous efforts to understand the nature and timing of Preclassic Maya economic exchange have depended upon relative dating of ceramic typologies, samples from radiocarbon-dated contexts now permit a higher-resolution assessment of diachronic patterns of ceramic production and consumption. These results indicate that local production and consumption of specialised ceramic serving vessels bearing ideologically significant designs first appeared at Cahal Pech as early as 1200 cal BC, during the Cunil phase.

By the late Middle Preclassic period, ceramic economic networks became increasingly complex and interconnected. Our results also provide evidence for the inter-regional exchange of specialised Mars Orange pottery between Belize Valley sites such as Cahal Pech and sites in the central Petén region of Guatemala (see also Callaghan et al. Reference Callaghan, Pierce and Gilstrap2018). Production and distribution of these specialised vessels may have supported networks of high-status individuals within a developing regional economy—although additional research is required to test this hypothesis.

Future research focused on characterising ceramic assemblages from other Preclassic contexts at Cahal Pech, from other Belize Valley sites and throughout the Maya lowlands, will aid in the reconstruction of changing production and exchange systems that were critical to the development of complex societies throughout the Preclassic period. Variation within and between assemblages may reveal the economic strategies that shaped both local and regional economies and contributed to institutionalised socio-economic differentiation.

Acknowledgements

Research at Cahal Pech was conducted through the ‘Belize Valley Archaeological Reconnaissance’ (BVAR) Project, directed by Jaime Awe and Julie Hoggarth. We thank John Morris and the Belize Institute of Archaeology for continued research support at Cahal Pech. The Penn State Welch Dissertation Research Award, a NSF Dissertation Improvement Grant (BCS-1460369) and a MURR Archaeometry Program Grant (BCS-1621158) provided financial support. Additional support for BVAR Project investigations at Cahal Pech were provided by the Tilden Family Foundation and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. We also thank two anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback that improved this paper.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2019.93