INTRODUCTION

Writing to Cardinal Wolsey in 1520 to report a conversation with Gaspard de Coligny, seigneur de Chatillon, about the construction of the tiltyard that would serve the meeting at the Field of Cloth of Gold, Charles, Earl of Worcester, reported saying to Chatillon that, ‘as toueching making of howses in bothe endes of the feld wher the justes and tourneys shalbe he thynketh that yt is not possible suche howses to be made by the day nor to have stuffe to do hyt/and also yt wold sore acombr the feld and that pavillions and tent[es] were most mete and most used for suche maters/then I tould hym that they shuld ^be^ but litell houses as be used for prync[es] campes in tyme of warre made of waynescott’. Chatillon replied, ‘suche houses be good/howbeyt he know not yet that his maist[er] was p[ro]vydid of anysuche houses bot he wold shortly have knowledgh therof and adv[er]tise me of the same’.Footnote 1

The casualness with which Worcester and Chatillon referred to the ‘litell houses as be used for prync[es] campes in tyme of warre made of waynescott’ suggests that such buildings were a feature of the European royal panoply of war that was familiar to both English and French observers alike. However, that Chatillon, a military commander of considerable experience, expressed some uncertainty about whether his master, Francis i, had such wooden buildings at his disposal, might indicate that they were not a regular feature of French military encampments in the early sixteenth century. Worcester, on the other hand, seems to be on firmer ground using the description of ‘litell houses […] of waynescott’ in front of Wolsey, whom Worcester presumably believed would also be well aware of what was meant by this phrase – as, indeed, he might, for the records of the Office of Tents and the surviving descriptive accounts of English military encampments of this period are peppered with references to the king’s timber lodgings. The impression they give is of a type of building that represented an important part of the king’s own accommodation while on military campaign and of an outlet for innovative architectural expression that could be used to deliver powerful messages about the strength, sophistication, and magnificence of Henry viii himself.

Even so, timber lodgings are a class of building that has gone largely unnoticed and unrecognised by historians of early Tudor architecture or of early modern warfare, falling perhaps in the gap between the two. Though both Cruickshank and Potter acknowledge the existence of timber lodgings in their work on the invasions of France in 1513 and 1544, respectively, neither attempted to contextualise them nor to understand more than the basics of their appearance.Footnote 2 There is a consanguinity with other ephemeral buildings constructed by the European courts in the period – temporary banqueting houses, hunting stands, tiltyard architecture, the scenery of the masque and the furnishings of civic festivals or royal entries – but they arguably differ from those structures in being designed to be easily demountable, movable and reusable. Therefore, it is the royal tents with which timber lodgings should be most closely associated, for, although they borrowed elements of their design and construction technologies from the types of buildings listed above, these were structures intended for use in the unique environment of a military campsite, to be erected alongside and interconnected with tents, and, like tents, they were designed to be easily pitched and struck at short notice.

It is in the context of banqueting houses that W R Streitberger considered Henry viii’s timber lodgings in the one article on the subject that has been published to date.Footnote 3 Streitberger outlined some of the evidence for a timber lodging that was built for Henry in 1543 for use the following year in his campaign against France – a building that also forms one of two principal case studies here – and Streitberger discussed it alongside a series of banqueting houses that were built around London and within the grounds of royal palaces in the following decade. These banqueting houses were otherwise unrelated to the king’s timber lodging, however, except that all were built under the supervision and guidance of the Office of Tents, and, given the specific military function associated with the timber lodging, it is slightly misleading to present it in company with buildings designed for a very different function. Furthermore, Streitberger’s description of the timber lodging mistakenly conflates the evidence of several buildings and consequently bears little relation to the reality of the structure under discussion. In fact, the timber lodging that he highlighted was an exceptionally sophisticated, innovative and architecturally significant construction that deserves recognition for its place in the canon of Henry viii’s artistic patronage. The discussion that follows will, therefore, consider it and an earlier timber lodging as representative of a unique class of building and will, for the first time, acknowledge their significance and provide context for their form and function.

THE KING’S CAMP

Henry viii saw himself as a warrior prince in the mould of his father, his illustrious medieval predecessors and his continental rivals. His place, when not showing off his martial prowess on the tiltyard, should be to lead his armies on the battlefield. In reality, Henry himself only went to war twice during his long reign: once in 1513, while still in the flush of youth; and again in 1544, by then ageing, ailing and pursuing a vainglorious attempt to relive the glories of his past. On both occasions he took with him a timber lodging to stand amongst his tents at the focal point of the royal camp.

In one sense Henry was like his father, for both had timber lodgings attached to their tents. As such, his use of these buildings cannot be seen as a new innovation.Footnote 4 Little detail is offered in the best account of Henry vii’s timber lodging, which simply describes it as ‘Houses of tymbre w[ith] the bent[es] laced to the same & cov[ere]d with canvas’ (despite the use of the plural ‘houses’ the account only records one timber lodging).Footnote 5 That it was covered in canvas seemingly aligns it more closely with the more familiar canvas-covered banqueting houses of the sixteenth century, for Henry viii’s timber lodgings, as the Earl of Worcester reported, were typically clad in wainscot.Footnote 6 In this regard, Henry viii may perhaps be considered an innovator.

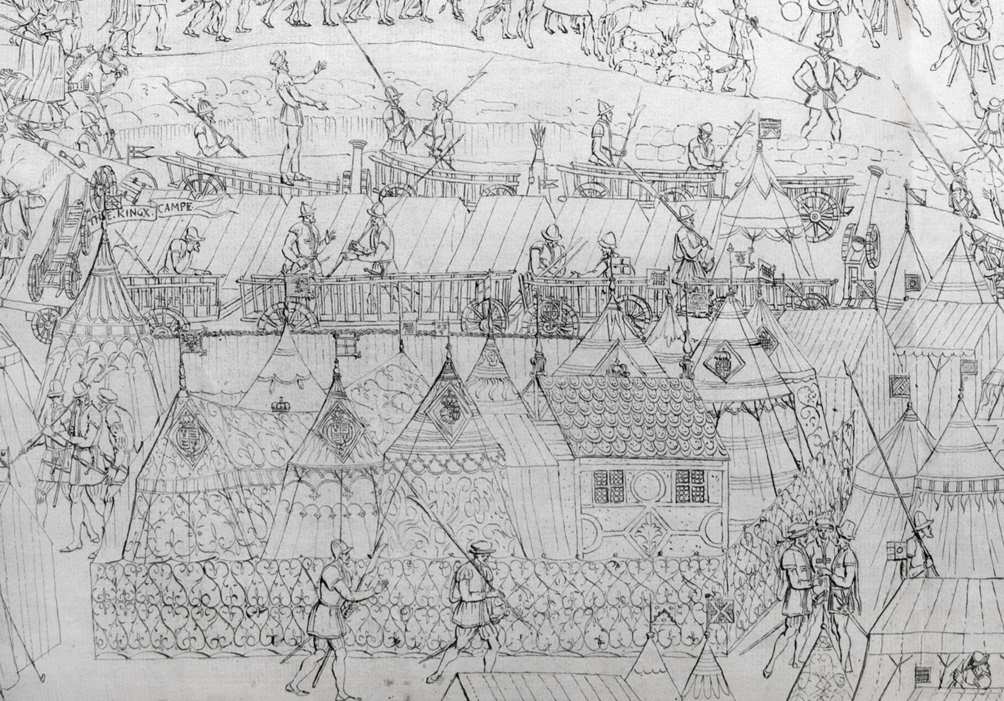

Pictorial representations of battlefield campsites in contemporary paintings and drawings, such as The Battle of the Spurs (fig 1), or the views of the aftermath of the siege of Boulogne in the British Library’s panorama of the devastation (fig 2), tend to present an image of a disordered jumble of tents. At the same time, instructional accounts detailing how military campsites were to be laid out dictate the establishment of well-ordered quadrants arranged around the tents of the king or highest-ranking commander positioned prominently at the centre.Footnote 7 The reality was probably something more in keeping with the view presented in the Cowdray mural’s depictions of the campsites at Marquison and Boulogne in 1544: the tents of the king set in their own enclosure, formed by elaborately patterned fabric screens, surrounded by the smaller and less highly ornamented tents of their higher ranking officers (figs 3 and 4), while the common soldiers made do with simple awnings or scavenged bivouacs known as ‘huts’.Footnote 8 The royal tents were intended to be visible markers of the royal presence in the landscape and could make explicit through their scale and grandeur the power of the monarch. A sense of the scale of the royal tent, and its associated timber lodging, can be gathered from the inventory of the tents used by Henry at Tournai and Thérouanne in 1513. It describes a vast, multi-room complex comprising six large tents or pavilions – the largest a rectangular marquee or ‘hale’ 15ft wide by 50ft long that served as a great chamber – connected by a series of tresances, or corridors, which led through a hierarchical sequence of rooms to the king’s timber lodging.Footnote 9

Fig 1. This imagined view gives a typical artist’s impression of a royal encampment – a jumble of brightly coloured tents with little order. Flemish School, sixteenth century, The Battle of the Spurs, c 1513 (oil on canvas) RCIN 406784. Photograph: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth ii, 2018.

Fig 2. Detail of Aftermath of the Siege of Boulogne, c 1544. Like other contemporary depictions of battlefields, the encampment is imagined as a loose arrangement of tents. Photograph: © British Library Board, Cotton Augustus I.ii 116.

Fig 3. The Siege of Boulogne by King Henry VIII MDXLIV. Drawing after the Cowdray House mural. This image is notable for the reasonably realistic depiction of the encampments, including the ‘King’s Campe’ in the lower left. Photograph: By kind permission of the Society of Antiquaries of London.

Fig 4. Detail showing the ‘King’s Campe’ with (on the right) the king’s timber lodging with its horn windows and tiled roof. From The Siege of Boulogne by King Henry VIII MDXLIV. Drawing after the Cowdray House mural. Photograph: By kind permission of the Society of Antiquaries of London.

A German visitor who visited this otherwise prosaically inventoried tent at Thérouanne with the Emperor Maximilian described entering the enclosure around the king’s tent through a gateway and remarked that ‘the arrangement of the tents looked like a castle or little town’. The same visitor was struck by the amount of cloth of gold, within and without the tent; the gilded sideboards bearing gold and silver plate; the king’s beautifully carved and gilded bed, hung with the finest cloth of gold; and the sculpted golden lion holding the arms of England that crested the ridge of the roof.Footnote 10 Henry, conscious in advance of his arrival at the front that the campaign would provide him with an opportunity to meet the emperor, had clearly dressed his tents to impress.

The excess and splendour of the tents at Thérouanne should not be misconstrued as an isolated attempt to astound a royal rival. Tents, whether on military campaign or on progress, were the perfect vehicles for princely magnificence; one need only to consider the way that extravagant tents were used as diplomatic tools at the Field of Cloth of Gold in 1520, or indeed how the Cowdray House murals (see figs 3 and 4) carefully depict the ‘Kinges Campe’ (as it is labelled in the image) at Boulogne in 1544, as separated from and much more highly ornamented than any of the surrounding tents. The value of royal tents on these occasions, aside from as temporary shelters, was that they fundamentally modified the meaning of the landscape in which they were located, providing a visible image of royal presence and power. By locating the king on the battlefield, they could provide a morale boost or rallying point for the troops – at least in theory – and the spectacle of such excessive consumption was intended to over-awe hostile observers with a sense of the king’s wealth, sophistication and ability to mobilise the necessary manpower. The strong inference was that anyone who could transport their own ‘castle or little town’ to a battlefield should be respected and feared.Footnote 11

The Cowdray image of the encampment at Boulogne is significant for another reason, for it provides the only surviving image of one of Henry’s timber lodgings. It is within the enclosure of the ‘Kinges Campe’ nestled in the lower right-hand corner but somehow more imposing than the neighbouring tents (see fig 4). The artist draws it with windows, a tiled roof and the implied form of a structural timber frame. It is clear from the image that it is different to those structures surrounding it, and is therefore special. In fact, the timber lodging depicted in the image of Boulogne is very well documented, and the description of its appearance provided later in this paper will demonstrate that the artist of the mural drew a pale imitation of what was in reality an extraordinary architectural achievement. Nonetheless, its dominant presence in the image provides a hint that if the logistics of pitching the royal tents seemed impressive to observers, the challenges of moving and erecting a whole wooden building in a theatre of war were undoubtedly even more so.

TOURNAI AND THÉROUANNE, 1513–14: ‘THE KYNG[ES] LODGYNG[ES] MADE OF TYMBRE AND PAYNTED LYCK BRYCKWORK’

Something of the logistical complexity of travelling with a timber lodging can be gathered from the accounts of Henry viii’s first overseas campaign in 1513. The timber lodging that he took with him on that occasion – or the ‘kyng[es] house of tymber’, as it is described in the inventory of 1513 – was smaller and less architecturally pretentious than that used at Boulogne in 1544, but, even so, of the fourteen carts that were needed to move the king’s accommodation to the front, twelve were required for the timber lodging alone.Footnote 12

This same timber lodging survived the ravishes of the battlefield and was transported back to the Office of Tents’ stores in London, where it was recorded in inventories of the king’s tents throughout his reign. Indeed, as late as 1547 it appeared in what seem to be two draft inventories that were drawn up to inform the list of tents included in the better known posthumous inventory of Henry viii’s goods.Footnote 13 In one it is described as ‘an olde Tymber howse coleryd bryke worke w[hi]ch wase at Torneye withe his best[es] vanes and ij greate Chymneys of Iron’, while in the other it is ‘An olde tymb[er] howse ^w[hi]ch was at the siege of to[r]ney^ not s[er]viable payntyd lyck brick w[or]ke w[ith] ^all^ beast[es] crownes crest[es] ij old chimneys of iron’.Footnote 14 So unserviceable was it, that it was not included in the final fair copy of the 1547 inventory.Footnote 15

The descriptions provided in 1547 begin to paint a picture of the timber lodging’s appearance – that of a wooden building, painted on the outside to resemble brickwork, ornamented on the roof with heraldic beasts, crowns, crests and vanes, and warmed within by heaters vented through iron chimneys. However, these descriptions also help to identify the same timber lodging in a much more detailed inventory that was compiled in 1542 and that also survives in two versions.Footnote 16 Here it is called ‘The kyng[es] lodgyng[es] made of tymbre and paynted lyck bryckwork’ and from the list of parts recorded it is possible to see the individual structural members of the building, and therefore to gain an impression of its scale and construction.Footnote 17 The building comprised two apparently interconnecting chambers, the first and larger of which had a footprint of 24ft by 12ft and the second of 16ft by 12ft. The wall posts of both chambers were 7ft 2in tall and they supported a shallow pitched roof formed by a simple king post truss with 8ft long rafters connected by a central ridge piece. The spaces between the upright members, between the rafters, and at the gable ends were all infilled with wooden panels cut to size and shape. The second chamber is recorded as having had a boarded floor. Each chamber had a fireplace described as ‘ij chymneys of irone with one mantell pece of Irone with a flo[wer] deluce lacking platt[es] for the harthes of the seyd chymneys & one of the fote barres and also the vic[es] & jawmes for the mantell of the same chymney’.Footnote 18 Quite what these chimneys looked like is a little unclear from the description, although the use of fleur-de-lis shaped locking plates suggests that they were both ornamental and functional. However, the impression given by the inclusion of mantelpieces seems to be of open fireplaces rather than of stoves. Furthermore, the 1542 inventory also reveals that the lodging was provided with ‘4 benchis with fete of Irone eche of them cont 7 fote long’.Footnote 19 It was, in short, a comfortable and well-appointed space that sheltered the king from some of the worse privations of the battlefield.

A further, more intimate glimpse into the interior of this timber lodging is provided by the German who visited the king’s tent in 1513. His account confirms the impression of comfort and security. Having walked through a series of richly furnished tents, he is taken ‘through a passage, covered within and without with cloth of gold, into a council house which puts together and takes to pieces again. It is painted red outside, and within is hung with golden tapestry. Therein stood the King’s bed, hung round with a curtain of very precious cloth of gold, the gilt woodwork being carved and very well finished’.Footnote 20 The description of this structure as being able to be taken to pieces and of being red on the outside leaves little doubt that the German visitor had entered the timber lodging painted to resemble brickwork and that that timber lodging played an important and prominent role within Henry’s encampment.

BOULOGNE, 1544: ‘THE KYNGES LODGYNG OF TYMBER FOR THE WARRES’

The timber lodging taken to Tournai and Thérouanne in 1513 was, however, rather modest and plain in comparison with the timber lodging commissioned by Henry from the craftsmen of the Office of Tents for his campaign to France in 1544. The timber lodging of 1544 is also much better documented and the picture that can be created of it is of a sophisticated architectural statement. Like the 1513 timber lodging before it, the building survived its military service and was retired to storage in the Office of Tent’s London warehouses. It was there that in 1547 it too was inventoried for the posthumous record of Henry’s belongings and it is from that inventory that the first sense of the physical appearance of the building is afforded:

Itm a Timber house all of Firre painted and gilted with A square Tower at euery ende and corner all couered with white plate scallappe wise and Seled within with paste worke painted the windowes of horne with all beastes Vanes & vices belonging to it.Footnote 21

Thanks to the extensive survival of accounts documenting the preparations for the 1544 campaign amongst the records of the Office of Tents and Revels that survive in the collections of the Surrey History Centre, Woking, and the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington DC, it is now possible to describe in much more detail the construction process and the appearance of this remarkable building.

From their base in the former church and precincts of the Whitefriars to the west of the City of London, the officers of the Tents had begun their preparations for the invasion of France by mid-April 1543, some fourteen months or more before the first English troops entered battle. By this date, the Office of Tents was probably already overseen by Thomas Cawarden (although he was not officially granted the title Master of the Office of Tents and Revels until 5 March 1545).Footnote 22 By the time the tents and timber lodging were delivered to Boulogne, the enterprise had employed hundreds of tailors, carpenters, joiners, painters, cordwainers, metalworkers and other artificers and labourers, making new tents and the king’s timber lodging. The latter was described in the records variously as ‘The kynges lodgyng of Tymber for the warres’, ‘The Kynges newe Tent of Tymbre’, or variations of the two. The earliest surviving accounts, dated 15 April to 22 June 1543, reveal that the design process began by creating two ‘patrones’, or models, of the building. A payment of 34s 9d is recorded to one John Cawton, a turner from Westminster, for ‘xxxvij small pyllors of box for the fryst patrone of hym boght & delivered’ and for ‘a hunderth ix pyllors bygger pyllers [sic] for thother patrone’.Footnote 23 At the same time, the officers of the Tents were rapidly sourcing essential supplies: from Sir Anthony Knyvett, thirty-one masts of spruce and deal (each between 58ft and 60ft long and ranging in circumference from 4½ft to 2ft); six more deal masts of similar dimensions from a Mr Hill; 381 deal boards (ranging in length between 28ft and 18ft, in width 17in to 1ft, and in depth between 1.5in and 1.25in); and from the blacksmiths Peter Rowse and Thomas Black, screws, nuts and bolts, clasps and plates.Footnote 24

Construction of the building cost in excess of £522 2s 5½d and took a full year to complete – an extraordinary investment of time and money that reveals the importance of the building to Henry’s undertaking.Footnote 25 It was not until late June or early July 1544 that the craftsmen working at the Whitefriars were able to hand the building to the company of twenty joiners under their master John Luke, who would accompany it to France. To prepare themselves, they staged a rehearsal at the Charterhouse, where it took them just two days and one night to put the building together.Footnote 26 The relatively short amount of time needed to erect what was a substantial and architecturally complex building was the product of the innovative technologies that it adopted. For a building that was intended to be relocatable, collapsible and reusable, the traditional timber-framing technologies of pegged mortice and tenon joints were inefficient and unreliable. Instead, the king’s timber lodgings used a system of screws, iron plates, and nuts and bolts to fasten the individual timber components into place, as well as hooks and eyes to hang the timber wall panels and architectural features. The list of provisions purchased in April and June 1543 includes payments to the smiths Peter Rowse and Thomas Black for the supply of: twenty-four 11in ‘screws and vices’ for pillars and to join panels; forty-eight pairs of clasp vices for crests; at least 100 more ‘screws and vices’ as well as iron plate clasps and pins for the rafters; and twenty-five iron squares with vices, screws and forelocks (an iron bar with a pin, rather like a linchpin) ‘to joyne groundselles & plates & postes together’.Footnote 27 Elsewhere in the accounts three more smiths are named alongside Rowse and Black but the service or goods they supplied is not itemised, while a London ironmonger named Parker sent nearly four thousand nails of assorted sizes to the Whitefriars workshop.Footnote 28 Nonetheless, it is clear that the ironwork detailed in the accounts for April and June and supplemented by Parker’s parcels of nails was but a small proportion of that required for the complete build. The final estimate for the cost of the building shows that at £102 16s 4d, the ironwork accounted for nearly one-fifth of the total recorded cost of £522 2s 5½d.Footnote 29

What is notable here is the sense of pioneering innovation in this small building. In his book, Building in England Down to 1540, L F Salzman identified the term ‘screw and vice’ as a synonym for nut and bolt, and stated that as a pairing they do not appear in building accounts before 1532 and then not with any regularity until the end of the sixteenth century.Footnote 30 Whether nuts and bolts had also been used to fasten the joints of the 1513 timber lodging is unclear, but even in 1543–4, as early adopters of this new technology for the purposes of creating an easily demountable building, the craftsmen of the Office of Tents were being exceptionally inventive and forward thinking.

The size of the building is difficult to determine with any certainty, for the records that hint at the dimensions of its footprint are confused. One account of its construction refers to 691ft 6in of base and sub-base ‘sett within & without the howse’ and for 602ft of cornice also ‘sett within & without’.Footnote 31 Assuming that the building’s footprint was square, this suggests that each side may have been as long as 75ft (although this does not necessarily account for the square corner towers mentioned by the 1547 inventory).Footnote 32 A more conservative, and possibly more realistic, estimate based on an alternative rough note recording some dimensions, and again making the assumption that the footprint was square, is that each side of the building was between 33ft 4in and 38ft 3in in length and that each of the four corner towers had a footprint between 6ft 6in and 8ft square.Footnote 33 A list of the hangings provided for the interior that is included in the 1547 inventory records a series of textiles measuring, at their largest, 22¼ yards long by 2¼ yards deep (or 66ft 9in by 6ft 9in), indicating that at the very least they were intended to dress a large space.Footnote 34 There is no evidence at all for the height of the building, but none of the accounts mentions steps or stairs so it is reasonable to conclude that it had only one storey.

That it was a substantial structure is made doubly clear by the logistics required to transport it. When the timber lodging returned to London after the fall of Boulogne in October or early November 1544, twenty cartmen made twenty-three separate journeys between the Office of Tents’ stores at the Charterhouse and the Tower wharf where part of the building had been disembarked, while another nine cartmen transported the remaining parts from the crane at the Vintry to the store in nine separate loads. In all, then, it took twenty-nine men thirty-two journeys to move the building from the riverside to the Charterhouse.Footnote 35 This may be compared to the twelve carts needed to move Henry’s earlier timber lodging during the 1513 campaign in France.Footnote 36

With its square towers at each corner, the building must have had the appearance of a small fortress. Its martial air was completed by a wooden battlement that jettied outwards from the parapet of the walls on a concave timber cornice, perhaps in reference to the machicolated parapets of English and European castles.Footnote 37 This was clearly an aesthetic that was appropriate for a military campaign but which also borrowed from the standard language of late medieval Gothic architecture adopted by many of Henry viii’s building projects. It was an architectural language that was continued by a phalanx of seven wooden heraldic beasts that guarded the rooftop, one of which stood in the centre of the roof holding aloft a vane with imperial crown as its pommel.Footnote 38 The seven heraldic beasts stood amongst a veritable forest of at least sixty more iron vanes that were supplied by blacksmith Cornelis Symonson and painted by the Italian serjeant painter Anthony Toto.Footnote 39 In this sense it also shared the language of the timber lodging that had been used at Tournai and Thérouanne in 1513, also described as replete with beasts, vanes and crests, but in most other senses the timber lodging at Boulogne was a much more architecturally sophisticated building.Footnote 40

Behind the parapet the timber lodging’s pitched roof departed from the norms of English architecture and presented a strikingly original feature. The 1547 inventory describes the roof as ‘couered with white plate scallape wise’, while an earlier rough copy of the same inventory substitutes the term ‘skale wyse’.Footnote 41 The white plate – probably sheet tin or steel – had been sourced from suppliers around London. So-called ‘double’ white plate was bought from ironmonger Thomas Dowghton, bottle-maker Thomas Todyr and merchant John Dowghtie to cover the lower edges of the roof panels.Footnote 42 The original design had apparently called for ‘single’ white plate, however, since another supplier – one John Storgeon – reported on 10 August 1543, that single white plate was ‘not to be got in all london I have dobyll whyte plate yt be havlfe as braude more & thyker’.Footnote 43 Perhaps with the march towards an inevitable war, the capital’s supplies of white plate had been stockpiled or diverted to the city’s armourers. Nonetheless, some supplies of single plate must have been found as the final estimate of costs accounts for both single and double at £38 4s 3d.Footnote 44

The raw metal plate was cut into individual round-nosed tiles following a template supplied by blacksmith Cornelis Symonson.Footnote 45 Symonson also supplied hammers and punches for making the nail holes in the plates so that they could be fixed to wooden roof boards.Footnote 46 A little glimpse of the roof is provided by the drawing of the timber lodging in the Cowdray mural, where it is clearly depicted as covered in round-nosed tiles (see figs 3 and 4). The overall impression must have been that the pitches of the roofs were covered in shiny silver scales, like fish skin, and an affinity can be noted with the Goldenes Dachl (built 1498–1500) in Innsbruck, Austria, which is covered in more than 2000 fire-gilded copper tiles (fig 5).Footnote 47 Within the context of English architecture, however, this roof was unique and as it glinted in the sunshine it must have made quite an impression.

Fig 5. The Goldenes Dachl, Innsbruck, 1498–1500. The roof is covered with fire-gilded copper tiles and may be similar in appearance to the covering of ‘white plate scallape wise’ recorded on the timber lodging used at Boulogne in 1544. Photograph: © Laszlo Szirtesi/Getty Images.

Although the plates or tiles were white metal, they were laid on the roof by a team of coppersmiths.Footnote 48 There is little evidence for copper roofs on buildings in London, or indeed in England, much before the eighteenth century, so their involvement in the project may have resulted from their experience of handling, working and soldering sheet metal rather than for any specific architectural expertise. Even so, as well as covering the building’s roofs the same coppersmiths also supplied gutters and downpipes made from sheets of latten (thinly milled brass or a similar yellow metal) shaped into round tubes and semi-circular gullies using a round mandrel also supplied by Cornelis Symonson.Footnote 49 The use of lightweight and durable latten for the rainwater goods highlights the sophisticated material selection that was made by the building’s designers to ensure its portability and performance in the field. Indeed, that performance was tested to its limits by the atrocious weather experienced in northern France in the summer and autumn of 1544.Footnote 50 Any damage inflicted on the king’s timber lodging is not reported, but thanks to its metal-clad roof and its system of gutters and downpipes it probably fared better in the wind and rain than the tents that surrounded it.

Inside, the timber lodging was divided into at least five spaces: a large central room and the four corner towers separated from it behind double doors.Footnote 51 Each of the tower rooms had a further single door to the outside or into adjoining tents.Footnote 52 In the central room the huge weight of the metal-clad roof was supported by a series of wooden pillars carved by joiner Peter Boder with ‘pill[er]s hedd[es]’ or capitals by a carver by the name of Newell [or Neville] Darby.Footnote 53 Hiding the roof trusses from view, and also supported by the columns, may have been the ‘paste worke’ ceiling mentioned in the 1547 inventory description.Footnote 54 The ceiling is slightly problematic since it is the only feature mentioned in the 1547 inventory, for which there is no clear record amongst the supporting building accounts. It is also difficult to positively identify what is meant by paste work. It may have been related to ‘paste board’, a sort of early form of cardboard that was regularly used to make theatrical props for revels and architectural elements for banqueting houses, or to the mouldable ‘paste and cement’ that was also used by theatrical prop makers.Footnote 55 In effect it was probably a form of mâché. In 1527 Giovanni da Maiano, otherwise better known for producing the terracotta roundels at Hampton Court Palace in 1520, oversaw a team of Italian ‘Mowdlers of pap[er]’ making ornaments for a temporary banqueting house at Greenwich in which to entertain a French embassy, while at Hampton Court Palace there are a series of surviving ceilings moulded in so-called ‘leather-mâché’ dating to the 1520s and 1530s.Footnote 56 Perhaps the best clue to its appearance, however, is a reference amongst the account of the painters Nicholas Lizard and Bartolomeo Penni for ‘makyng of mold[es] of the kyng[es] & princ[es] armes & badg[es] w[ith] the beast[es]’ for the timber lodging.Footnote 57 Although not specifically identified as for the ceiling, these moulded arms and badges may be indicative of moulded ceiling roundels like those still to be seen in the Great Watching Chamber at Hampton Court or lozenge shaped panels like those of the so-called Wolsey Closet at the same palace.Footnote 58 Whether papier-, leather- or another form of mâché entirely, the result was a mouldable, lightweight, durable, dismantlable and paintable ceiling and once again demonstrates the clever use of technologies to make the building easily transportable.

Classical columns and a moulded ceiling like those of Hampton Court Palace hint at a stylish, sophisticated and comfortable interior. The bill for the work of painters Nicholas Lizard and Bartolomeo Penni, paid in July 1544, further demonstrates the decorative splendour of the interior.Footnote 59 Their account included panels painted to resemble jasper ‘off sondry coalleurs’ and white marble, and a frieze or border ‘wryten w[ith] l[ett]res off fyne gold’, perhaps spelling out the motto ‘Dieu et Mon Droit’ or similar. They also painted the columns in jasper colours and partly gilded (parcel-gilt) the capitals.Footnote 60 The effect seems reminiscent of the architectural setting depicted in the Royal Collection’s painting of The Family of Henry VIII (fig 6), thought to be almost precisely contemporary with the king’s timber lodging. Though the painting presents an imagined setting, it is believable enough as a royal interior to suggest that the timber lodging responded to then current architectural fashions.

Fig 6. The imagined interior in this portrait of Henry viii and his family bears some resemblance to the interior of the timber lodging he used at Boulogne in 1544. British School, sixteenth century, The Family of Henry VIII, c 1545 (oil on canvas) RCIN 405796. Photograph: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth ii.

The interior of the building was lit by windows, at least four in number but possibly more.Footnote 61 Payments recorded in the account of the painters Lizard and Penni for painting twenty-three ‘small pyllars’ might in turn relate to the ‘lyttle pillers for wyndowes’ that were supplied by the carver Newell Darby in July and August 1543.Footnote 62 These pillars were probably window mullions and, given the use of the word ‘pillar’ to describe them, may have looked like miniature classical columns. Certainly, the window heads that were carved by Darby and Paul Cannewe were described as ‘peces of antique over the wyndows’ which implies a classical or Mannerist aesthetic.Footnote 63

The windows themselves were leaded casements set with quarries of lantern horn.Footnote 64 Again, in the use of horn rather than glass, we see the adoption of materials or technologies that were durable and transportable. However, we also see a rare moment when the technologies, clever though they were, failed. Payments to a painter by the name of Francis Taye record the purchase of lead, solder and horn ‘to be occupied in & abowt[es] the king[es] ma[jesties] tymber howses at the campe before bolloyn’.Footnote 65 These must have been supplies with which to carry out running repairs, and it is interesting to consider that even in the midst of a military campaign there was a regime of maintenance to keep the timber lodging in good order.

At the front and rear of the building were two porches framing the ‘portals’ or entrance doors.Footnote 66 Here again the architecture of the timber lodging shows a classical influence, for the porches were, in effect, small porticoes. Each of the two porches was supported by ‘grete colons’, some of which were made by a turner by the name of Nicholas Lyon.Footnote 67 That the columns were turned and not carved may indicate that they were of the Tuscan order. Supported by the columns, of which there seem to have been two to each porch, was a triangular pediment with three vase-shaped finials (also turned by Lyon and described in the account as ‘grete cuppes’).Footnote 68 Within the pediments of the two porches were displayed the coats-of-arms of both Henry viii and his young son, Prince Edward. Also supplied by the carver Newell Darby, they were described in the accounts as ‘iiijor armes & bages of the kynges & princes graces in walnot tre’.Footnote 69 That there were four arms in total suggests that each porch had a pair of carved arms; one for Henry and one for Edward. The records for carving the arms also reveal an interesting change of mind by the designers of the building, for they seem originally to have been intended for the triangular gable ends of the roof before being relocated to the pediments of the porches.Footnote 70

This, then, was a substantial piece of architecture that was more ambitious and elaborate in its appearance and scale than the smaller, plainer, timber lodging painted like brickwork that had travelled to Thérouanne with the king thirty-one years earlier, and it must have been a remarkable sight in the midst of the bloody siege at Boulogne. These two different buildings, created at either end of Henry’s reign, while otherwise serving the same functions, reflect changes in two of the defining motivations in his life: his personal interest in art and architecture and, closely related, his own interest in self-image-making. While the earlier timber lodging was functional and relatively modest, the timber lodging of 1544 was a riot of detail, a huge kit of parts and a logistical challenge to transport. In one sense this more elaborate architectural expression may simply reflect the king’s changing interest in building that, as Simon Thurley has demonstrated, only really flourished after the demise of Cardinal Wolsey in the late 1520s. In the unique setting of a military campaign it may have had a deeper significance.Footnote 71 Perhaps the king – ageing, ailing and no longer personally or physically able to cut the magnificent warrior figure on the battlefield that he had three decades before – now compensated for his weakness with his timber lodging. Rather than riding into battle with his troops, instead he presented himself to them through the strength and magnificence of his new timber lodging – a very visible and visceral symbol of his royal power.

THE FUNCTIONS OF HENRY VIII’S TIMBER LODGINGS

The scale and sophistication of Henry’s timber lodgings begs an obvious question: what was their function? Why go to the huge expense and logistical effort to build and transport such pretentious pieces of architecture to a battlefield at all rather than relying on tents which are, on the face of it, much more practical shelters?

The simple answer talks about magnificence. These buildings and the extravagant tents that surrounded them spoke of the king’s wealth, status, sophistication and power. They were visible battlefield markers and loci of authority that positioned him in a landscape and, in doing so, altered the meaning of that landscape for those who witnessed it. There was no mistaking the king’s tent replete with costly fabrics, statuary and heraldic devices, and with a prominent timber lodging alongside. The timber lodging, with all the cost and logistical complexity needed to make it and transport it, was very much the preserve of the king – indeed there is no evidence of noblemen having equivalent buildings – and it clearly gave the message that a king with the wealth and power to transport his own town, complete with wooden castle, to a battlefield, was not a king to be trifled with.

It was also masculine architecture that played to Henry’s sense of self-image as a great warrior prince. Timber lodgings were solid, massive and martial and, with their machicolated battlements and faux painted masonry and brickwork, quoted castle architecture and spoke of strength. Indeed, the rather over-the-top expression of masculine self-image and dynastic success presented by the timber lodging at Boulogne, when compared with the slightly more sedate lodging at Tournai and Thérouanne, might be argued to reflect the king’s own failing health by that later date. If he could no longer cut the dashing, athletic, princely figure on the battlefield, he could at least cut it in the campsite. It is perhaps not surprising, therefore, that there is no evidence at all of Queen Mary or Elizabeth having timber lodgings; indeed, nor is there really evidence that they had their own personal royal tents in the way that their father Henry had. The royal tent, as conceived during the sixteenth century, had martial connotations that were of little use to either of the Tudor queens regnant.

However, timber lodgings were functional as well as symbolic buildings. Frustratingly, although otherwise well documented, there is no evidence for how Henry used his timber lodging at Boulogne in 1544. However, the German visitor to the king’s tent at Tournai and Thérouanne in 1513 described the timber lodging there as a ‘council house’ and reported seeing the king’s bed in it.Footnote 72 The locating here of the royal bed is clearly significant, for it allowed the timber lodging to function in both the ways implied by the German: as a council chamber and as a bedchamber. The latter is self-explanatory – the bed was for sleeping in – but the former relies on the symbolism of the royal bed as both representative of the royal body, even in absentia, and as a place of meeting where truths could be spoken honestly and in confidence.Footnote 73 It should not be considered surprising, therefore, for a council chamber to have a royal bed in it. In addition to the bed, the timber lodging’s four 7ft long benches were presumably equally conducive to its role as a council chamber.Footnote 74

Another visitor to Henry’s encampment at Thérouanne, Laurent de Gorrevod, the envoy of Margaret of Savoy, provides a further corroborating insight into the function of the timber lodging by complaining that, having gone to see Henry, he was not in his tent but was still ‘in his wooden house, and was not even ready to hear mass’.Footnote 75 The implication is that the timber lodging was a more private space and, although de Gorrevod does not reveal the time of day, one wonders whether it is suggestive of an early morning visit while the king was still readying himself for the day.

A lack of evidence for the furnishings of the timber lodging at Boulogne in 1544 means that it is impossible to say for certain whether that lodging also served the same function, although it seems highly likely that it did. Certainly, it is clear that Henry took a grand bed with him on that campaign, for it survived and was still on display to visitors at Hampton Court Palace at the turn of the seventeenth century. One visitor described it as ‘of red satin set and embroidered with gold’, and it is tempting to try to imagine this bed in the reasonably sumptuous painted interior of the timber lodging.Footnote 76

Henry’s decision to travel to war with a timber lodging and, as it seems, to use it as a bedchamber and council chamber was perhaps unsurprising. Despite access to any number of great palatial tents, Henry was not normally much of a camper. On the occasions that he travelled – on progress or to great events of state like the Field of Cloth of Gold – he rarely, if ever, stayed in his tents overnight, preferring instead the warmth and security of houses and castles for his bed. The progress to York in 1541, for example, a journey that is especially well documented thanks to the indiscretions of Catherine Howard along its route, saw the royal couple accommodated in houses despite the large number of grand tents that travelled with them, while at the Field of Cloth of Gold in 1520 the king and queen were lodged in Guînes castle.Footnote 77 Wartime presented different challenges, however, and the availability of suitable accommodation close to the battlefield could not be guaranteed. The king was forced to camp, often in an exposed and dangerous location at the mercy of the enemy and the weather. Both could be vicious. In 1544 the encampment at Boulogne was attacked by French forces and even eleven years later, in 1555, the Office of Tents still had ‘three olde tymber howses p[ar]te burned and spoyled at bolyn in the camisado’ in their stores.Footnote 78 The king’s timber lodging with its wainscot-clad walls, sturdy wooden doors and metal roof must have provided some security from small bands of raiders and volleys of small-arms and arrow fire. It was, in effect, a bunker or strong-room right at the heart of the encampment where the king could sleep soundly or retreat in moments of extreme danger.

It also provided much needed protection from the elements. Indeed, the weather during the 1544 campaign was atrocious, for the fall of Boulogne – Henry’s victory – coincided with a sudden change in the weather. The storm that blew in towards the beginning or middle of September was so severe that it damaged some of the tents and pavilions, stores of victuals and the ships lying at anchor in the estuary nearby, forcing those who could to take shelter amongst the ruins of the town.Footnote 79 Whether the king’s timber lodging sustained damage is not recorded, but its solid timber construction and the system of gutters and downpipes must have kept the rain out for longer than the flimsier tents. Although, unlike the timber lodging used in 1513 at Thérouanne, the lodging at Boulogne does not appear to have had fireplaces or stoves to heat it, it was, almost certainly, by nature of its construction a warm, dry and safe refuge from the weather and the storm of war.

CONCLUSIONS

Located right in the midst of the royal tent, the timber lodging protected and sheltered the king, providing him with secure battlefield accommodation when alternative lodgings were unavailable. It was a necessary luxury of monarchy and the sort of structure that only the richest could afford to commission, transport and store. By employing innovative new technologies like nuts and bolts and pushing the boundaries of early modern construction practice to offer relatively practicable solutions to the king’s need to travel, they were reliant on the scale of resource only really available to a monarch. But timber lodgings were more than just shelters – they were a tangible, visceral, representation of the king’s own body. They located him on the battlefield, providing a visible rallying point for troops and a reminder of his presence amongst them, thereby presenting the king as a military commander and leader of men. The wooden walls painted like brick and masonry, and the domineering scale spoke of the strength, solidity and masculinity of the king’s own person, while the riot of architectural details, some heraldic and some polite and refined, spoke of both his legitimacy and lineage and of his sophistication and magnificence. Inside, for those privileged to see it, stood the royal bed, itself highly representative of the king’s body and providing a sort of beating heart within the cavity of the timber lodging.

Herein lies the importance of the king’s timber lodgings that elevates them from fleeting ephemeral structures to powerful expressions of royal architectural patronage. By concurrently representing princely magnificence and providing protection from danger, the timber lodging speaks eloquently of the idea of the king’s two bodies: the power and status of the divine body politic and the weakness and vulnerability of the earthly body natural. There are few other single pieces of royal architecture, perhaps with the exception of royal tomb monuments, that expresses this idea so forcefully and so clearly.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research for this paper was undertaken for Historic Royal Palace’s AHRC-funded project ‘Portable Palaces: Royal Tents and Timber Lodgings, 1509–1603’. The author wishes to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council for its generous support and his current and former colleagues at Historic Royal Palaces, especially Professor Anthony Musson, Annie Heron, Dr Wendy Hitchmough and Dr Edward Legon. Special thanks go to Professor Maurice Howard, who kindly read an early draft of this paper, and to Professors Thomas Betteridge, Maria Hayward and Glenn Richardson, who, along with Professor Howard, have all given their time and expertise to advise the Portable Palaces project. A final thanks goes to Dr Charles Farris with whom the author has worked closely on the Portable Palaces project and whose own research, comments and advice have all been invaluable in completing this paper. Any mistakes are the author’s own.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003581520000050

ABBREVATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abbreviations

- BL

-

British Library, London

- CoA

-

College of Arms, London

- FSL

-

Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington DC

- L&P

-

Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII , HMSO 1862–1932, London

- SHC

-

Surrey History Centre, Woking

- TNA

-

The National Archives, Kew