- Speakers

Kiyotaka Sasaki, Souichirou Kozuka and Takuya Izumi

- Moderators

Felix Steffek and Mihoko Sumida

- Concluding Conversation

Felix Steffek and Mihoko Sumida

- Questions for Further Thought

Felix Steffek

A Financial Crisis Unlike Any Other

Sumida: We are about to begin the fifth conversation of the ‘Legal Innovation’ series. Today’s topic is ‘Corporate Governance in the Age of Artificial Intelligence’ and we have three guests. The first speaker is Professor Kiyotaka Sasaki, Visiting Professor at Hitotsubashi University, Graduate School of Business Administration. He joined the Ministry of Finance and worked abroad for nearly ten years in total, including twice with the OECD at its Paris headquarters and three years at the IMF in Washington, DC. In 2010, he joined the Japanese Financial Services Agency’s Inspection Bureau. He then served as Deputy Director-General of the General Affairs Bureau of the FSA’s Inspection Bureau in 2010, Director-General of the FSA’s Certified Public Accountants Audit and Review Board in 2011, Director-General of the FSA’s Securities and Exchange Surveillance Commission in 2015 and Director-General of the FSA’s General Policy Bureau in 2018.

After retiring in 2019, he has been a Visiting Professor at the University’s Graduate School of Business Administration and head of the Global Financial Regulation Research Forum. He is also involved in educational and research activities in collaboration with the FinTech Research Forum led by Professor Mikiharu Noma, who is also contributing to the Hitotsubashi University–Cambridge University research project on legal systems and artificial intelligence.

Professor Sasaki, we are very much looking forward to hearing your thoughts.

Sasaki: Thank you for your kind introduction. The topic of my talk is ‘Corporate Governance Challenges in the Era of COVID-19’. If you look at this title alone, you may wonder what it has to do with innovation. One of the things that became clear during the COVID-19 pandemic was the acceleration of digitalisation and innovation. So, although I say, ‘in the Era of COVID-19’, there is a deep connection with technology and innovation.

My original background is in finance, particularly in supervision, inspection and regulation as well as in global cooperation in these areas of finance. Today, I would like to talk about the relationship between innovation and corporate governance from the perspective of financial and securities market supervision and audit firm supervision. These are the areas I worked in as a regulator.

I will first briefly speak on the COVID-19 pandemic and the many insights I have gained from it. Second, I will talk about how corporate governance is changing in terms of digital transformation (DX). Third, I will talk about changes in corporate governance from a sustainability perspective.

When I was at the Japanese Financial Services Agency, I faced the global financial crisis triggered by the failure of Lehman Brothers in 2008, the so-called Lehman Shock, and, going further back, the Japanese financial crisis in 1998 when major banks and securities companies failed. Whereas the past two financial crises were caused by financial products, in particular the non-performing loans of Japanese banks and, in the case of the Lehman Shock, by investment banks trading derivatives products, the most recent crisis was caused by COVID-19. Here the risk is directly related to human life and health. To reduce this risk, quarantine and a reduction of human contact have been implemented. Some countries have locked down cities and, in Japan, a state of emergency has been declared.

The measures to reduce the risk to human life and health have resulted in a contraction of the real economy, which has been spilling over into the financial markets. In other words, the COVID-19 pandemic differs from the last two financial crises in both cause and risk-spillover pathways. Since the cause is a virus, the best solution is the development of medicines and vaccines, or a new way of life known as the ‘new normal’.

What Problems Have Emerged as a Result of the COVID-19 Pandemic?

Sasaki: The pandemic has highlighted a number of problems, which can be divided into two main categories. One is the manifestation of existing problems, particularly in the case of Japan, where digitalisation has been lagging behind. The other is new challenges associated with the pandemic, which have made the issue of inequality more apparent. More to the point, I have the acceleration of DX in mind. DX is expected to accelerate in order to cope with the new normal of infection control. I call this COVIDX, which is a combination of COVID and DX.

In terms of disparities, infection and mortality rates vary from country to country, region to region and between age groups. In addition, there are economic disparities where the shrinking real economy has a significant impact on vulnerable groups and small and medium-sized enterprises. In the case of the Lehman Shock, large global companies were particularly affected, whereas in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic rather small and medium-sized companies such as restaurants and hotels were affected. Education is also a big issue as regards inequality. Even prior to the pandemic, there were large disparities in education between schools and regions. Since the pandemic, much teaching moved online and big differences in learning opportunities have been noted depending on the economic and IT situation among families. These are just some examples, but the disparities that have existed in the past have become clearer and wider with the pandemic.

From that point of view, there are two relevant aspects of corporate governance. One is the acceleration of DX, and the other is the impact of environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues, in particular the issue of sustainability.

The Five Ds of Advancing DX

Sasaki: Next, I would like to talk about changes in corporate governance, particularly changes due to the acceleration of DX, or, in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, the acceleration of COVIDX. The need for DX has been much discussed, even before the pandemic. When I was at the FSA, I inspected and supervised virtual currency, i.e. cryptoassets and service providers and was also in charge of various issues associated with the digitalisation of the financial sector. In promoting DX, especially in the field of finance, I would like to discuss the five Ds, representing major aspects of digitalisation.

The first D is ‘Data’. The point of DX is that the data itself will have value. The use of data will become so important that it will determine the future of a company.

The second D is ‘Decentralisation’. As the name suggests, the central bank is the centre of finance, issuing money and controlling monetary policy. In addition, stock exchanges have traditionally been centralised mechanisms. However, virtual currencies such as blockchain are intentionally built on decentralised systems with no central controller in place. They pose challenges to the traditionally centralised mechanisms. Looking at this from the perspective of a traditional central bank, take, for example, the Facebook-led Libra digital currency announced in June 2019, there is strong opposition to financial systems without a central administrator. In any case, the second D reminds us that the movement to ‘decentralise’ traditional centralised mechanisms will accelerate.

The third D, ‘Diversification’, refers to new players in finance. Traditional financial players have been banks and brokerage firms, but the traditional financial players are being challenged by GAFA – the collective name for the four major US IT companies Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple – FinTech and other players.

The fourth D is ‘Democratisation’. Conventionally, the supply side or the providers of financial services have had more power than the customers of the services and consumers. However, with DX, as with the internet, customers, clients and users will have more power than the providers. Customer satisfaction and touch points with customers will be crucial.

The last D is ‘Disruption’. The first four Ds of the DX have disruptive effects on the existing financial players as well as on the authorities that are still mostly stuck within the traditional legal system and supervision.

How Governance Will Change with DX

Sasaki: Along with the DX represented by the five Ds, there will be a change in the concept of the ‘Three Lines of Defence’, particularly in the area of governance. I am not sure how familiar you are with the term ‘three lines of defence’. At least in the world of financial supervision, since the Lehman Brothers collapse in 2008, supervisors around the world have adopted this as a common concept. Financial institutions are thought to need three lines of defence in terms of governance, risk management and internal control. The first line is the frontline sales department, i.e. the traders and dealers who generate revenue. The second line is risk management and compliance. The third line is internal audit. The key point is that the first line of the three lines of defence, in particular traders and dealers generating revenue, also has a defensive role. In any case, it is the board of directors or the governance of the company or financial institution that is responsible for building these three lines of defence. The authorities and regulators review whether the three lines of defence have been built and are functioning effectively. This concept is not only applicable to financial institutions but also to public companies, for example. I believe that this concept of the ‘Three Lines of Defence’ will change as DX progresses. I expect the entire three lines of defence to become digitalised.

If all three lines of defence, including the first line, which is mainly responsible for generating revenue, are digitalised, then the basis of the business will be system-managed. Businesses will no longer function without the system. This will make it impossible to take undesired risks. In other words, if risk controls are embedded in the system, then a trader or dealer in the first line trying to trade illegally or take a risk that is too high will be stopped by the system. This will lead to more sophisticated control and defence capabilities in the first line.

Now let us look at risk management – also referred to as compliance – in the second line. It is also expected to become more sophisticated thanks to digitalisation. Risk management will be carried out based on 100 per cent of the data and 100 per cent of the population of transactions as opposed to a sample basis. This will enable risk management in real time. This is already happening and will accelerate in the future. What used to take a lot of time and effort in the second line will be reduced and may even be done in the first line. If this happens, then the question arises as to what the difference between the first and second lines will be.

Furthermore, if digitalisation progresses, the role of internal audits in the third line may also change. As each of the three lines of defence becomes more sophisticated through digitalisation, it becomes possible for companies to produce perfect financial statements internally. Until now, when a company prepared its financial statements, there was an incredibly labour-intensive, multi-layered checking process. Data was collected from the business units, checked by risk management and compliance, checked by internal audit, checked by the CFO and board of directors and then checked by the external audit. Even then, accounting irregularities occurred and errors were made. If the three lines of defence become digital and the control functions become more sophisticated, there is a possibility that companies will be able to produce error-free financial statements themselves – 100 per cent perfect financial statements.

Changing Processes and Positions

Sasaki: This raises the question of what will happen to the role of accounting audits and external audits. For example, will the financial institutions be able to control 100 per cent of the bad loans that erupted during the Lehman Shock or the Japanese banking crisis without having to be checked by the authorities? This also raises the question of what will happen to the role of inspection and supervision by the authorities.

The concept of the Three Lines of Defence changing in terms of the activities of the first line of business and the second line of risk management is almost the same for financial institutions. If the accuracy is considerably improved, then why not use two lines instead of three lines? It is important for the third line, internal audits, to be independent. So, it is unlikely that the entire third line will disappear. However, when the first and second lines are merged, what will the role of the third line be? What will be the role of the board of directors, and what will be the role of the audit committee, which is mandated by the Companies Act? What will be the role of the external audit? What will be the role of inspection and supervision by the authorities in the case of financial institutions?

I expect that the concept of the three lines of defence and the role of management and supervision, including external audit and regulatory audit by the authorities, will change in the financial industry. If this happens, it may be necessary to review existing governance frameworks, such as the Companies Act, the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act and the Corporate Governance Code in the case of Japan, among many others. Of these, I am particularly concerned about auditing. Traditionally, audits are compliance audits, looking at whether standards have been met or not. I think there is a possibility that these conventional audits could be disrupted by DX.

Will Auditing Survive?

Sasaki: I used to be in charge of reforming financial inspections and supervision when I was at the FSA, and I used to face similar questions. Conventional financial inspections and supervision were basically ex-post checks, with a focus on superficial compliance with laws and regulations. DX will disrupt the traditional inspection and supervision carried out by the authorities.

What is the role of auditing that will not be disrupted by DX? My response to this question is that audits should be forward-looking to prevent misconduct and other risk factors, analyse the root causes in a holistic manner and ultimately add value to the management of the company. Overall, the impact of DX on governance will appear largely in terms of changes in the three lines of defence, particularly with the possibility of consolidating the first and second lines of defence as well as the role of audits.

ESG Priorities Changing as a Result of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Sasaki: Another thing I would like to talk about is the ‘Three Ss of the COVID-19 pandemic’ from a sustainability perspective. The first of the three ‘Ss’ is ‘Social’ or ‘Society’. The second is ‘Sustainability’, as the sustainable development goals (SDGs) have been increasingly discussed and promoted around the world including in Japan. ‘Solidarity’ is the third S, which means unity and cohesion instead of division within societies and between people. In any case, the concept of the three Ss has become more important throughout the pandemic.

As an extension of this, the concept of ESG is attracting attention and making progress internationally, both in the financial sector and in the field of governance. Before the pandemic, governance was the most advanced area of ESG in Japan. Governance was the first to progress, including the development of a corporate governance code, followed by environmental matters, particularly climate change and the growing awareness of greenhouse gas issues.

Compared to these two areas, Japan is lagging behind in the ‘Social’ area. There are various issues in the social area, such as human rights, gender equality and diversity. In Japan, ESG has progressed in the order of governance, environment and social in terms of priorities. However, the pandemic, which posed risks to human life and health, has highlighted the importance of people-oriented thinking. Thus, the area of ‘Social’, which includes health and safety of life, employment, community and education, is now the priority among the ESG issues. Environmental matters have long been actively discussed in Europe, particularly climate change and decarbonisation. The COVID pandemic cannot be considered unrelated to public health and climate change.

Governance is undergoing change as well. Even before the start of the pandemic in 2019, the US Business Roundtable, an organisation similar to Keidanren Japan, emphasised that a broader, multi-stakeholder perspective is important, rather than the traditional shareholder-centred approach. The 2020 World Economic Forum also stressed the importance of governance from a multi-stakeholder perspective.

To sum up, through the pandemic, the importance of ‘Social’ has been significantly raised as well as the increasing importance of environmental issues and change of governance structures with a multi-stakeholder perspective and focus on sustainability.

Steffek: Thank you very much. I tremendously enjoyed this presentation. There was a lot of information in it and you touched many different things. If you allow me to, I would like to raise an idea.

DX Enables Prediction

Steffek: You mentioned the five Ds, namely data, decentralisation, diversification, democratisation and disruption. I wondered whether there could be a sixth D, ‘Design’. I am talking about design since technology supports actors in anticipating consequences rather than being surprised by certain events after they have made their decisions. Technology can be used to predict economic events. It can also be used to design and plan legal and economic relationships. I would be interested in your opinion on whether technology in this area could also lead to people designing, i.e. pre-planning, rather than being surprised afterwards.

Sasaki: Thank you very much for your insights. I think you are right that these five Ds, or DXs, will raise expectations and make it possible and important to be more proactive and involved in planning and design. In my mind, this was included in the fourth D, ‘Democratisation’. I think that would be a relevant part of the supply-side focus. Each and every individual who owns data, each and every data user, should be proactive in protecting and using it.

The traditional governance of financial markets or financial supervision is no longer viable. From my perspective as a former regulator in charge of the rapidly changing securities market sector, I can say that market self-regulation and what is known as soft law are becoming more important than laws and government rules to respond to the changes and innovations in the markets. As DX advances, such self-regulation, self-rulemaking among the market participants and the design of self-regulations and soft law will become even more important. In this respect, I think the points you have just raised are exactly right.

However, I have a tendency to group five Ds, three Ss and so on into odd numbers. I think that odd numbers are a bit cooler than even numbers (laughs). Adding a sixth one is also possible, of course.

Steffek: So, how about considering a seventh one?

Sasaki: That’s fine too, but generally people can’t remember more than three. I think five is the maximum (laughs).

Sumida: Thank you (laughs). Now, let us move on to the next presentation.

Achieving the Same as before with DX?

Sumida: I would like to ask the second speaker, Professor Kozuka from the Faculty of Law of Gakushuin University, to give a presentation. He graduated from the Faculty of Law of the University of Tokyo and has been teaching at the Faculty of Law of Gakushuin University after serving as an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Law and Economics of Chiba University and as a professor at the Sophia University Law School. Many students attending this conversation series said that they became interested in legal innovation after reading his new book, The Age of AI and the Law.

We have asked Professor Kozuka to give a presentation on the ‘Implementation of Artificial Intelligence in Corporate Governance’.

Kozuka: Thank you. When Prof Sumida suggested the subject for my talk today, I thought that I could talk about how to make sure that Japan’s Principles on AI, which Mr Izumi is going to talk about next, are actually being implemented and how to place them within the context of corporate governance. However, while drafting a new paperFootnote 1 on AI during the New Year holidays, I came up with a new topic, which I cannot help but talk about. Therefore, I will talk about the relationship between innovation and technology in business organisations.

As Professor Sasaki mentioned, when technology is developed, the organisation must adapt to it. Regardless of how many Ds there may be in the DX of corporate governance, the organisation of a company must also change. In the field of law, particularly with regard to digital technology, it is claimed that the equivalent function that had been achieved before digitalisation shall now be realised digitally. It means that people can do the same thing digitally that they used to do with papers and physical objects. This is what lawyers often say.

In the international scene, such functional equivalence is often required under international rules on digital commerce by UNCITRAL, the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law. Under such an approach, people do the same thing as before by using digital technology. This makes me doubt that innovative technology contributes to social change. Maybe lawyers tend to stand by the ancien régime.

One of the issues in the context of COVIDX, as Professor Sasaki named it, is the practice of Japanese companies using seals (hanko) too often when signing documents. It was claimed that there were people who could not work remotely and had to come to the office to stamp the seal during the COVID-19 pandemic. I do not know how many such people there actually were. Still, it was decided that this Japanese business practice should move to the digital realm.

Why Digitising Stamps and Seals Is Not Easy

Kozuka: In the digital era, we have the technology of digital signatures. As the Japanese seal is equivalent to a signature in the West, it is no surprise that the idea of replacing the seal with a digital signature comes up. The problem is that the Japanese law on electronic signatures is outdated. For example, the Japanese Electronic Signature Act was enacted in 2001 when there was no cloud technology. Article 3 of the Act provides that electronic signatures are to be made using a code and a device. It is presumed that a smart card is used as the ‘device’. To be specific, a person is identified as ‘Ms A’ by the smart card, and then she produces a digital signature by using the code of Ms A. Arguably, the Act does not allow electronic signatures using the cloud and that is just one reason why the Act needs to be reformed. That being said, there is a risk of destroying a sound established practice if the reform is made without examining why Japanese companies have relied on seals and not electronic signatures, i.e. why they have resisted the move to electronic signatures.

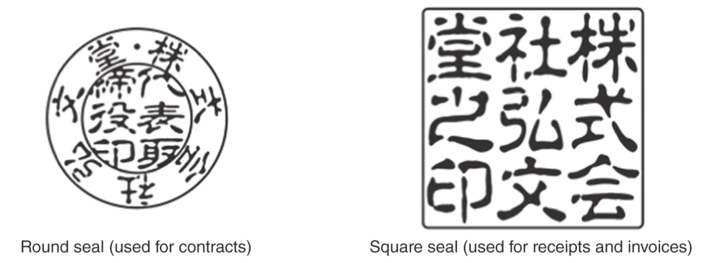

The students in this conversation series will be familiar with a personal seal, but a corporate seal is a little different from a personal seal. To begin with, there are two types of corporate seal. One type is the ‘round seal’ and the other is the ‘square seal’. Both are shown in Figure 5.1. If you look closely at the round seal, there is an inner circle inside the outer circle, with the company name written between the two circles. In the centre, there are six Chinese characters reading ‘CEO’s seal’. This means that this seal is used by the CEO of the company when the company concludes a contract.

Figure 5.1 Two types of corporate seals

Another type of seal, the square seal, is used for receipts and invoices, not contracts. Thus, companies use these two types of stamps depending on the nature of the document to be signed.

Every company has rules on who is allowed to stamp these seals and when they are allowed to do so. These rules prevent the unauthorised use of a seal. The basic rule is that the company’s CEO is required to stamp the seal when entering into a contract. However, the CEO may not have the time to stamp all the contracts. If they really did so, they will have pains in their arm. Therefore, there is often a rule that senior employees other than the CEO may get a seal from the head of the organisation and then seal the contract for their department. After the seal is stamped onto the document, the employee returns the seal to the original place of storage, thus ensuring security.

With electronic signatures by smart cards, the same thing can be done: the smart card can be stored away and only brought out when necessary. An employee can use it to make an electronic signature with the smart card under a regulated procedure. However, such a procedure cannot be replicated when the digital signature is made using the cloud. In that case, there is only a password but no device. Once you know the password to conclude a certain contract, you cannot delete the knowledge from your memory. As a result, control over the power of concluding a contract is looser than before. Against this background, I anticipate that Japanese companies will not be able to move easily to electronic signatures, especially cloud-based electronic signatures, as long as they wish to seek a functional equivalent of the current control over the use of a seal.

However, there is a solution to this: you can give authority to senior employees to conclude certain contracts subject to specific limitations. There is a provision in the Companies Act that can be used for that purpose. It says that an employee such as a division manager or a general manager if given authority over a certain matter, can conclude a contract within the scope of that authority. This can be found in Article 14 of the Companies Act. Unfortunately, there are only a few court decisions on this provision. Those who have studied the Companies Act will be aware of this article, but Japanese companies do not resort to it. The reason why they do not use it is the employment system in Japanese companies. It is known as a ‘membership system’, in which the responsibilities and authority of individual jobs are not clearly defined. As a result, there are no clear authorisations as regards contracting. The assumption underlying the provision in the Companies Act is a ‘job-based’ employment system as seen in Western companies.

The Japanese Employment System and the Use of Seals

Kozuka: The abovementioned provision of the Companies Act was originally transplanted from German law. European companies have an employment system in which the scope of authority of each employee is clearly defined. A rule stating that ‘a contract can be concluded within the scope of the employee’s authority’ raises no problem in Germany. But in Japanese companies, despite the provision in the Companies Act, the actual employment system is membership-based. The employment contract in Japan does not say ‘Ms A’s authority extends to the subjects as described below.’ Therefore, a division manager in Japan typically cannot conclude a contract by using a seal. Instead, with the premise that the person who stamps a seal is usually the CEO, the company keeps the practice of letting a senior employee stamp the seal as a temporary alternative to the CEO, saying, ‘just for today, please stamp the seal instead of her’.

Unless we change the system of employment in Japan itself, we will not be able to move from seals to digital signatures. Furthermore, if Japanese companies start delegating powers to senior employees without changing the membership-based employment system, some employees, whose scope of power is not explicitly determined, may end up exercising more power than they should. Hence, the abuse of power by employees will become an issue. Allowing the company to discipline an employee for exceeding their power, even to dismiss them, requires a reform of labour laws such as the rules on dismissal. Thus, the issue surrounding seals is not simply that of the substitution of a seal with a digital signature. Functional equivalence of a seal and a digital signature is only achieved after adapting corporate governance, labour law and the employment system. When focusing on individual issues, the pursuit of functional equivalence might appear to be a conservative approach. The truth is, however, that we have to place them in the broader context of the evolution of organisations adapting to the development of technology. Otherwise, DX may never take place in the true sense.

Who Is Responsible for Misora Hibari Being Revived by AI?

Kozuka: The next topic I would like to address is the control of AI through the corporate governance of Japanese companies. Here, too, we focus on how organisations change. In Japan, the basic principles are stated in the ‘Social Principles of Human-centric AI’. Under these principles, the AI Research and Development Principles and the AI Utilisation Principles were developed. It is meaningless to produce such principles unless they are actually used. They must serve as the standard reference when a Japanese company develops AI and provides AI-based products or services. The approach is the same in Europe, where the term ‘AI ecosystem’ is often talked about.Footnote 2

To think about this point, let us consider the anecdote of ‘Misora Hibari revived by AI’. In 2019, NHK, Japan’s public broadcasting entity, aired a programme titled ‘Reviving Misora Hibari by AI’. ‘AI Misora Hibari’ also appeared in that year’s Kohaku Uta Gassen, the annual TV music show on New Year’s Eve. Misora Hibari was a pop singer, a great star of the post-war era. Making her debut as a girl prodigy a few years after the devastating defeat of Japan in World War II, she was an extremely popular singer from the 1950s to the 1980s. She passed away in 1989, the same year as the Showa era ended. To mark the 30th anniversary of her death, a project was organised to use AI to create music that Misora Hibari would have sung if she were alive in 2019.

The project itself is remarkably interesting. But when the music was aired on the New Year Eve’s show, a famous artist said, ‘It is blasphemy against Misora Hibari to air something like that. It is just unacceptable.’

While there may be pros and cons, I am interested in how the governance worked that led to ‘Misora Hibari revived by AI’. I am curious about who had the final decision-making power, who was responsible and whether the governance was properly organised at all. The NHK reported that they had consulted various people and made decisions together. It is reported that the members of Misora Hibari’s fan club, who visit her tomb every year, Misora Hibari’s son and Yasushi Akimoto, who wrote lyrics for Misora Hibari and also wrote lyrics for this project were consulted. At several points in the process, they said, ‘This still does not sound like Misora Hibari’ or ‘Now it sounds very close to Misora Hibari.’ It is claimed that each of them listened to the final version of the song produced by AI and gave their consent. I would argue, however, that if everyone decides together, then no one really took responsibility and no proper governance was in place.

Giving the AI Principles Their Appropriate Place

Kozuka: Defective governance such as in ‘Misora Hibari revived by AI’ should not happen. The AI Principles need to be properly placed in the context of corporate governance. The sociologist Albert HirschmanFootnote 3 argued that there are three ways of making decisions in a group: exit, voice and loyalty. Loyalty means following the decision taken elsewhere without complaining, while exit means that those who disagree leave the group. In between, there is voice, under which one expresses one’s opinion, effectively saying ‘no, that’s not right’.

If people conclude that a certain AI product is not appropriate, it will not sell and will eventually disappear from the market. This is the mechanism referred to as ‘exit’. Under the ‘loyalty’ approach, a law is enacted and compliance with a certain set of rules is required. The AI Principles developed for Japan rely on this approach. The AI Principles as a whole, however, are not based on law. The idea is rather to uphold the ideal of human-centred AIFootnote 4 and collaborate with countries that share the same ideal, such as the UK and Germany. In this way, we pursue the ‘human-centred’ ideal in a way that is different from prescribing legal rules. If this is the case, then companies should decide to implement these principles as a matter of corporate governance, and then appeal to consumers to use products that respect the AI Principles – rather than those that do not. This means that companies can claim that their product is based on the idea of a human-centred society in the expectation that customers will buy it even though it is a little more expensive than competing products.Footnote 5

Where shall such AI governance be located in the context of the corporate governance issues discussed by Professor Sasaki? If the rules are determined by law, then the issue is compliance. Currently, we do not know how those parts of the AI Principles that do more than just restate the law are treated in corporate governance. Japanese companies tend to lump together all unfamiliar issues and label them as corporate social responsibility (CSR), meaning that they are socially demanded, but not legally. Every listed company has a CSR page on its website, where many of these unfamiliar issues are addressed. However, as Professor Sasaki mentioned earlier, the term ‘ESG’ has become increasingly important in the last few years.

Simply put, the basis of the ESG argument is that it is not enough to pursue only the interests of shareholders. However, the situation in Japan is a little different from that in other countries. Japanese companies have not always been dominated by shareholder interests. The corporate governance reforms in Japan that began around 2010 were rather the opposite of those in Western countries. The reforms required companies to think about the interests of their shareholders. Since ESG emerged in this context, some corporate managers said that the traditional Japanese way of considering stakeholders’ interests was right and that the primacy of shareholders’ interests was not the way to go.

As argued in the UK and other countries, companies pursue the interests of shareholders. But the shareholders’ interests should be enlightened ones, i.e. interests that the insightful shareholder pursues, not just the greed-driven shareholder interest in making money. In the UK and France, directors have responsibilities to take into account social issues, such as not buying materials from suppliers whose employees are working under conditions equivalent to slavery and to consider the effects of their activities on the environment.

I would argue that the same is true for the principle that AI must be used to create a human-centred society and that an AI’s decision must be based on proper data, with consideration for privacy and security and not be discriminatory. This approach fits neatly with general corporate governance principles.

To What Extent Are Companies Being Held Responsible?

Kozuka: Besides discussing technological innovation in the context of corporate governance, we need to look beyond it. As already discussed, in Europe (and elsewhere) it is not enough to address social problems only in your company. Subcontractors of your company should not be tainted, either. Suppliers in the so-called supply chain, those who provide raw materials and components, must also be examined. As far as AI is concerned, business partners who develop datasets and programmes must also adhere to the AI Principles. Suppose that a large, well-known company intends to create an AI product and contracts with a small AI company to write an algorithm. The former company must stipulate in the contract that the AI Principles must be adhered to. This will probably lead to a significant change in the way contracts are drafted in Japan. The contracts will come to include the rules to make the counterparty adhere to the AI Principles, threatening termination for non-compliance and on-site inspections for supervision. Therefore, the discussions of corporate governance in the age of AI extend to discussions of the governance of contractual relationships, including the supply chain. In fact, there is the idea that the company itself is actually a nexus of contracts. If that is the case, it is no surprise that the governance of contractual relationships can be considered as an extension of corporate governance.

Ultimately, both the issues of seals and digital signatures and of the AI Principles share the same theme: organisations go through transformation when technology develops. For organisations, which includes companies as organisations in a narrow sense and contractual relationships as organisations in a broad sense, issues that fall under the ‘S’ of ESG emerge. It is important to understand the AI Principles as a manifestation of sustainability. Doing so enables us to continue to build and develop the same kind of society we have maintained before the era of AI. I believe this is the ultimate functional equivalence to be pursued in the AI era. Thank you for your attention.

Steffek: Thank you very much. I very much enjoyed this presentation. You raised the very interesting question of functional equivalence. You looked at how technology may be a functional equivalent of the things that we have done before in another way. You talked about e-signatures and seals, but then you moved on to consider how technology may change goods and services. As regards goods and services, it may not be a functional equivalent, but it may be something new that technology brings. Based on your analysis, I wondered whether technology will also change the organisation of firms and companies. Nobel Prize winner Ronald Coase, already many decades ago, taught us that companies are a reaction to transaction costs and the problems that we face in organising businesses by way of contract. So, if technology changes the way we cooperate and provides new ways of cooperation, then I think it could be quite interesting to think about how the original analysis of Ronald Coase in the 1930s will be transformed today. This is related to Professor Sasaki’s idea that there will be more democratisation. Perhaps companies and businesses will become less hierarchical because technology allows more decentralised decision-making processes. Ronald Coase has explained the existence of companies based on the idea that the hierarchical form of organising business is a solution to the transaction costs burdening contracts. So, people, instead of organising their business based on contracts, form companies in order to use hierarchical structures to organise the production of goods and services. But if technology facilitates better cooperation, then maybe these hierarchical structures will not be necessary anymore and decentralised structures may be more efficient. That was just one thought I had, and I would be interested in your opinion.

Just to add a second thought: I very much agree with your emphasis on the human-centricity of AI because it helps us to use AI for the benefit of individuals and ensures that AI does not become more important than humans. Ethical guidelines for the use of AI are often, in practice, implemented by computer experts, programmers and coders. However, these addressees are not used to reading and engaging with such ethical guidelines. It is rather the lawyers who are used to working with such guidelines, while the coders are not. Coding and programming, however, are key for the creation of AI services. Hence, we need to think about the design of ethical guidelines for coders and programmers. They are doing the real work. Thank you very much again for your excellent presentation.

AI Principles in Japan

Sumida: Thank you. Regarding the first point, Professor Steffek has co-convened a conference on ‘The Future of the Firm’. I am wondering if he was inspired by this work to consider the issue of business organisation. As to your second point, I think it was a message of encouragement for Mr Izumi from the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, who will be speaking now. Mr Takuya Izumi, Director for Information Policy Planning, Commerce and Information at the Policy Bureau of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry will give a presentation on ‘The State of AI Governance in Japan’. Thank you very much for your contribution.

Izumi: Thank you for the introduction, Professor Sumida. My name is Takuya Izumi from the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. I would like to invite you to join me today for a short time to consider ‘AI Governance in Japan’. AI governance is an issue for which we are still searching for the right answers, and I hope to think about these answers together with you. The content I am going to talk about has been analysed by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry for a long time. Professor Sumida is also participating as an expert in this area.

The government sets various targets every year. For example, the Integrated Innovation Strategy 2020 and the AI Strategy 2019 Follow-up set the following targets shown in Figure 5.2.

Figure 5.2 Ideal approaches to AI governance

Izumi: Note specifically the overall goal: ‘Towards the implementation of the AI Principles, we will study ideal AI governance in our country, including regulations, standardisation, guidelines and audits, which will contribute to enhancing our country’s industrial competitiveness and social acceptance, while also taking into account domestic and international trends.’

After the sentence of the goal, CSTI, MIC and METI are listed – METI is the abbreviation for Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. This means that METI should work towards the goal. I think that the goal has two key elements: the AI Social Principles, which Professor Kozuka touched on somewhat earlier, and AI governance. I would like to invite you all to think about these two areas together.

Laws Fail to Catch Up with Reality

Izumi: Japan’s AI Social Principles are contained in the document ‘Social Principles of Human-Centric AI’, which was published in March 2019. The document sets out three basic principles and seven social principles. The three basic principles are: (i) a society where human dignity is respected; (ii) a society where people from diverse backgrounds can pursue diverse happiness; and (iii) a sustainable society. The seven social principles are human-centricity; education and literacy; privacy; security; fair competition; fairness, accountability and transparency; and innovation. It is important to put these into practice.

Why is AI governance raised as a separate issue? There are problems that cannot be solved by the AI Social Principles alone. The AI Social Principles were developed because AI, while a very useful technology, can also have a negative impact on society. The goal of the AI Social Principles is to control such negative effects and to use AI beneficially. How to put this into practice is the challenge of AI governance. The METI study group defines ‘AI governance’ as ‘the design and operation of technical, organisational and social systems by stakeholders with the aim of maximising the positive impact of the use of AI while managing risks arising from its use at a level acceptable to stakeholders’. Simply put, the government’s stated goal is to consider the design and operation of such systems in order to put the AI Social Principles into practice.

What is difficult is the design of AI governance itself. The challenge is that the law cannot keep up with the speed of technological development and the complexity of society. The standard of AI technology is evolving day by day. Depending on the design of AI systems, there are many possible applications. Depending on each specific application, the characteristics and magnitude of the risks will vary. How to control and govern all of this is a difficult challenge.

Complexity of AI Bias Issues

Izumi: Let us take the application of AI in the job selection process as an example that you may be familiar with and interested in. Amazon in the United States developed a system that uses machine learning to screen CVs and rank them on a five-point scale. When Amazon tried using it for selection, they discovered that it disadvantaged women for certain jobs. If you have been reading articles on AI governance, you may be familiar with this case study. The news spread quickly and the mistake was widely recognised as a bias issue. Job hunting is an especially important process for young people, so it is absolutely essential to avoid situations where they are disadvantaged by bias.

On the other hand, it has been suggested that the use of AI in the selection process may have eliminated unconscious bias. For example, in the book Freakonomics, which became a topic of conversation about ten years ago, a case study was reported in which the content of a CV was the same, only the name was changed to indicate a white applicant and a black applicant. These CVs were then sent to a number of companies. The case study found that white applicants were more likely to be called for an interview. This suggests that unconscious bias may be present on the human side and that AI could be used in the selection process to eliminate unconscious bias in people.

Just considering the bias issues shows that AI governance is not an easy issue to solve. There are other relevant insights to digest. I found an interesting article in the Harvard Business Review, stating that AI holds the greatest promise for eliminating bias in hiring for two reasons. It can eliminate unconscious human bias, and it can assess the entire pipeline of candidates.Footnote 6 An IEEE paper states that in recent years, computer scientists have constructed fair clustering algorithms to counteract bias. A novel approach described in a paper handles multiple factors simultaneously.Footnote 7 We are required to address the issue of bias. And we believe this is part of the AI governance challenge.

Governance Innovation: From Rule-Based to Goal-Based

Izumi: How, then, should the problem of laws not being able to keep up with the speed of technology and the complexity of social change be solved? A suggestion is made in the METI’s report ‘Government Innovation: Redesigning Law and Architecture for Society 5.0’, which Professor Sasaki referred to earlier.Footnote 8 The report points out that it is preferable for laws and regulations to be goal-based, indicating the values ultimately to be achieved, rather than rule-based, i.e. including detailed behavioural regulations. It also points out that when goal-based regulations are introduced, a gap arises between the regulations and the company’s operations, and therefore it is necessary to develop non-binding guidelines to help the operators achieve the goals. The same problem of a gap between regulation and operations exists in AI governance, so we believe that providing some guidelines may be a solution.

Those attending Professor Sumida’s class may feel that perhaps goal-based regulation sounds similar to the Corporate Governance Code. The goal-based approach is similar to the principle-based approach of corporate governance codes. We believe that AI governance should be well integrated into corporate governance, guided by the implications of governance innovation, as Professor Kozuka mentioned earlier. For example, the reference material for the Corporate Governance Code states that ‘the Code does not adopt a rule-based approach, in which the actions to be taken by companies are specified in detail. Rather, it adopts a principle-based approach so as to achieve effective corporate governance in accordance with each company’s particular situation.’ In his book Preventing Corporate Scandals, Mr Tadashi Kunihiro states that in today’s rapidly changing world, rules cannot keep up with changes in society and that, in short, what stakeholders are looking at is not rule-based, but rather the principle-based question of is this company honest?Footnote 9 The book is not directed at the AI issue, but the analysis that in today’s rapidly changing society, rules cannot keep up with society might have been said with AI in mind.

Learning from the Wisdom of Predecessors

Izumi: This is a little off-topic, but Emeritus Professor Iwao Nakatani of Hitotsubashi University cited a book entitled ‘Physics and Beyond’ written by Werner Heisenberg, the father of quantum mechanics and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics, in a 2001 Nikkei newspaper column entitled ‘The Art of Reading Half a Step Behind’. The relevant part reads:

[O]nly those revolutions in science will prove fruitful and beneficial whose instigators try to change as little as possible and limit themselves to the solution of a particular and clearly defined problem. Any attempt to make a clean sweep of everything or to change things quite arbitrarily leads to utter confusion. In science only a crazed fanatic – for instance, the kind of man who maintains that he can invent a perpetual-motion machine – would try to overthrow everything, and, needless to say, all such attempts are completely useless.Footnote 10

As I have a science background, I like this passage.

When we talk about AI, there is inevitably a special atmosphere and an air of needing to do something new. Just as Heisenberg’s achievements in quantum mechanics rewrote only the physics of the micro-world, but not the Newtonian mechanics of everyday life, it seems to me that the emergence of AI does not negate most of the arguments on governance that have been made, but that we need to make good use of the wisdom of our predecessors, including corporate governance knowledge, to develop AI governance principles. Not only corporate governance but also, for example, privacy issues have been considered previously. I think the right direction is to manage AI to align with such existing knowledge. More to the point, the AI Principles are being shared globally. The elements of the AI Principles, such as fairness, transparency and accountability, are generally shared by all developed countries. Hence, it makes good sense to refer to insights and examples from other countries.

What Is a Fusion Approach that Fits Operational Reality?

Izumi: The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry defines two approaches to AI governance: one is the explanatory approach. The Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI, compiled by European experts, have an accompanying checklist, which provides explanations, for example, on what transparency means and how to meet transparency requirements. However, no integration with corporate governance is considered.

The other approach is referred to as the fusion approach. METI believes that this is preferable. For example, the UK guideline ‘Explaining Decisions Made with AI’ provides guidance on what data protection officers, compliance officers, technology departments, senior management departments, etc. should be doing. This is easier to integrate into corporate governance. Another example is Singapore’s ‘Model AI Governance Framework’. For some reason, this one is better known in Japan. Instead of focusing on explaining the AI Principles, it is presented in such a way that it can be integrated into practice giving practical examples, such as internal governance structures and measures, determining the level of human involvement in AI-augmented decision-making, operations management as well as stakeholder interaction and communication. I believe that this direction is helpful.

Let us return to the government’s objectives, which I mentioned at the beginning. The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry was asked to think about ideal AI governance in our country. We are in the process of putting it together right now, with the help of Professor Sumida and other experts. If you would like to know more, please see the report that will be published in due course. We plan to publish it in English at the same time, so we hope that people from overseas will read it too.Footnote 11

Why We Create a Unique Governance System in Japan

Izumi: To overcome the problem of laws failing to keep up with the speed and complexity of society, we should aim for goal-based AI governance. Fortunately, we already have those goals in the Social Principles of Human-Centric AI. The question then becomes how we can achieve the goal of human-centric AI. This concerns the gap between regulation and operations, which I have mentioned earlier. To solve this problem, we should create non-binding governance guidelines for companies. We should be aware of the interactions with corporate governance and integrate AI guidelines well into corporate practice.

You might think that we should just take examples from the UK or Singapore, but it is not that simple, as each country has its own strengths and weaknesses. For reference, let’s look at the example of Singapore. At the end of Singapore’s Model AI Governance Framework, the names of cooperating companies are listed: Apple, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, IBM, Salesforce, AIG, Mastercard, etc. There are no names of Japanese companies. The names of so-called GAFA tech giants dominate the list, which leads us to speculate that the guidelines may be specific to such businesses and may have been designed to successfully absorb the risks of a particular industry.

It has been pointed out that in Japan, the strength lies in OT, Operational Technology, rather than IT, Information Technology. The areas of application of AI may be different and the risks we face may be different. We hope to support companies by creating governance guidelines that carefully delve into these areas and can be successfully integrated into corporate governance.

After providing governance guidelines, there are still issues to be considered. The guidelines are non-binding, so after the guidelines are created, it is important to encourage companies to use them. Various ideas have been proposed on incentives to encourage use, such as a slight increase in points for complying with these guidelines in government procurement. As Japanese AI technologies and products go out into the world, we would like to continue our discussions so that we can lead the world in a direction that maximises social benefits while minimising risks. We hope that today’s talk has provided you with an opportunity to consider AI governance. Thank you very much.

Sumida: Thank you very much, Mr Izumi, for your invaluable presentation. Let me start with the panellist, Professor Kozuka, who is an expert on the subject matter. Professor Kozuka, would you like to comment?

Kozuka: Many thanks. I would like to connect this with the issues Professor Steffek has raised earlier. Ronald Coase, who Professor Steffek mentioned, was an economist well-known already before World War II. He posed a question about why corporations exist and why they do not procure all products and services on the market through contracts. He suggested that a corporation exists when it is less costly to trade in the form of an organisation rather than trade in the market, a phenomenon which people later called transaction costs. In the 1980s, it was suggested that transaction costs are in fact largely caused by information problems, such as having only insufficient information to make decisions for the transaction or an information gap between the parties. This has been developed in the field of information economics. I think this is very relevant in the age of AI. It is almost impossible for people to get all the information they need, and at some stage, they have to decide what action to take. When making that decision, if AI analyses more data than a person can and shows some suggestions, it may be useful in overcoming the information problem. Conversely, the AI may draw a person into an inappropriate decision and adversely affect human behaviour. In the latter case, how to correct errors so that the benefits of overcoming information problems prevail becomes the issue. This is where the topic of AI governance comes in.

Mr Izumi emphasised ‘goal-based’ policymaking, which is also very suitable for AI. We cannot identify each factor behind a decision, pointing to the data that was determinative in a certain decision, because the process of AI reaching a conclusion is a black box. On the other hand, we cannot accept that data causes discrimination and prejudice as a result of AI decision-making. So, what we need to do is to create a system, the governance structure, which does not allow this to happen. Thus, the whole story is important, from the great economist before the War to the most recent report that will be published tomorrow.

Sumida: Thank you. Professor Sasaki, would you like to comment?

Sasaki: Yes, thank you. Firstly, when talking about governance, my presentation was more about the state of governance in organisations, companies and financial institutions. However, both Mr Izumi and Professor Kozuka talked about the state of rules and norms in the world as a whole, including AI, and what the governance of individual companies, organisations and financial institutions should be. This perspective focuses on the way society as a whole should be governed and the goal-based approach of Society 5.0. Therefore, my first point is that the discussion has gone beyond conventional corporate governance and is now about the governance of society as a whole, not just in Japan but in the world as a whole.

What Will You Do with AI?

Sasaki: My second point is that whether we talk about innovation or DX, they are only the tools or means, and what you ultimately do and realise with them is important. What is the purpose of what we do? AI is ultimately a tool, so the people who use it, how they use it to improve the world and one of the Ss, ‘Social’, are becoming increasingly important.

Law is ultimately a tool, too. As Professor Kozuka said, we must use the law as a tool to change and improve society. People should not be used by the law. People should use the law to make the world a better place. That is the basic premise. For students who, in particular, study law, it is important to be well aware of the technical details, such as what statutory rules say or what the past precedents are, but it is also important to be well aware of the purpose of the law. The discussion today has made this truly clear.

Sumida: Thank you. Are there any students who would like to ask a question?

Student A: I would like to ask Professor Kozuka. This is a bit of a departure from the topic, but I saw in a presentation by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications that you wrote about AI developments that ignore social values, and I would be very interested to know what exactly you mean by that.

Kozuka: For example, if there is a country where there is a severe ethnic conflict, it is conceivable that a facial recognition AI that identifies one of the ethnic groups is used by the dictator who supports the other ethnic group. There is a possibility that some of the managers of the companies who are approached to develop such a recognition system might think that this is an effective way to make money. We have to prevent such decisions.

Another current problem is AI weapons. It is already a reality that drones equipped with AI are used for an attack with the command ‘eliminate this terrorist stronghold’. Still, the weapons currently used are ‘semi-autonomous’, i.e. weapons that are subject to human supervision. Lethal weapons fully operated by AI – so-called lethal autonomous weapon systems (LAWS) – have not yet been developed. It is argued that the development and use of fully autonomous AI weapons should be banned.Footnote 12

At the very least, Japanese companies should not be engaged in the development of AI involving such conflicts. I also believe that we must expand the coalition around the world to prevent such production from happening.

Beating AI by Anticipating Essential Issues

Student B: I have a question for Professor Sasaki. You mentioned that companies will be able to carry out audits on their own, but in that case, what kind of mechanisms can be considered to ensure that the audits are appropriate?

Sasaki: Thank you for your question. This is slightly different from the current discussion on AI. In the first place, there are accounting audits and inspections by the authorities to ensure that a company’s financial statements are correct. At that time, there are standards for determining whether they are correct, which may be laws or auditing standards. The problem is that simply determining whether they are correct in accordance with those standards is no longer sufficient.

As Mr Izumi explained, the rules are not keeping up with the changes in the world. It is no longer possible to audit in the conventional compliance way, where the audit is to check whether the rules and standards are being met.

What are we going to do in the future? One idea is, as I told you today, to think about governance without rules. If we wait for rules, we will not be able to catch up. Of course, it is not right to have no rules, but as Mr Izumi explained earlier, instead of the government regulating in the form of laws, as has been the case in the past, it is better to provide a goal-based, principle-based direction and leave it to proactive initiatives to decide how to put it into practice. However, principles alone will not be enough to determine whether they are being followed or not. How can this be ensured? This is an exceedingly difficult question.

One thing I have in mind is that auditing is a job that requires looking at many different things. I used the term ‘forward-looking’ earlier. We look at many things, not just one company or one department. In this way, we can see issues that are common to many things that cannot be seen by looking at specific things individually. I refer to this as, ‘from micro to macro’. It is possible to abstract from the individual stories and to understand common implications. This kind of capability is a feature that AI cannot have. AI is good at analysing past data and predicting the future. Human judgement in this area is extremely important.

Therefore, in legal education, after memorising past precedents and statutory rules, we need to think about future issues, about the common issues in the legal system that emerge and what issues exist in fields other than law. It is about predicting these issues, abstracting from the micro to the macro and finding common implications, and then connecting that to the next agenda setting. These are the kinds of capabilities that AI cannot replace. Even in an age without rules, this will be something that can assert the raison d’être of auditing. It is a difficult problem to solve.

Sumida: Thank you very much. Finally, Felix, is there anything else?

Steffek: Thank you – very briefly. I agree with what Professor Sasaki, Counsellor Izumi and Professor Kozuka have said. I would like to make an attempt at bringing it together. What is the goal? I would say it all starts with the people and their interests. Technology and law should aim at helping people to fulfil their interests, but also to help people to find solutions where their interests collide. So, that would be my answer. I would like to leave it there, but of course, we could discuss this for a full day. I found your comments and presentations very inspirational. Thank you.

Sumida: We have indeed had a very productive session today. With that, I would like to close today’s fifth session.

Concluding Conversation

Sumida: Professor Kiyotaka Sasaki, Visiting Professor at Hitotsubashi University’s Graduate School of Business Administration, spoke about the nature of corporate governance reform and how it is being transformed through the evolution of technology and the COVID crisis. He based his comments on his experience of leading inspection and supervisory reform at the FSA. Without using the technical terms of the many laws and regulations, he explained what many corporate governance reforms have tried to achieve and what he considers to be the keys to achieving reform in the future. It was as if we had a compass and a chart in our hands. For example, given that the COVID crisis is different from previous financial crises, the vectors of change are also different. Given the severity of the crisis, including the fragmentation of society, he emphasised the importance of ESG in creating corporate value and the need to revise our understanding of ESG.

The discussion went well beyond the topic of technology enabling real-time audits and improving corporate governance. We heard that there is a possibility for the first and second of the Three Lines of Defence to merge. It could even become a service provided by a platform. We also discussed that forward-looking auditing is necessary for the third to keep its relevance. In this context, we have also heard about the significant role of human thinking to be involved. This is a very concrete way of looking at the world. At the same time, this is an argument that has the potential to revolutionise the way we think about compliance, auditing and corporate governance. I was overwhelmed by its persuasiveness.

Steffek: I found Professor Sasaki’s approach very interesting. He distinguished between internal corporate governance and external corporate governance and discussed the impact of technology on both sides. He predicted major changes in both areas and linked them to the ‘Five Ds’: data, decentralisation, diversification, democratisation and disruption. I very much agree that these five aspects will drive innovation in corporate governance. In the discussion, I had raised the question of whether we needed to add another ‘D’ for ‘design’. I had in mind the question of whether corporations and their counterparties will more and more use technology to design their relationships on the basis of live information and predictions based on AI. This would lead to better-informed contracts and to fewer surprises later. In other words, corporate governance would suffer less from informational constraints and would become less conflict-prone.

Sumida: The question from the students at the end of the session sounded like the voice of a person in the field who is confused about how to take charge of governance in the age of AI (laughs). Professor Sasaki talked about forward-looking decisions, a particularly critical issue for legal innovators. He also advised us not to form silos and to zoom out from time to time. We had planned this conversation series so that the students would be encouraged to become legal innovators. I am happy that this has worked out.

Steffek: Then Souichiro Kozuka, professor at Gakushuin University, spoke on the implementation of advanced technology in businesses and the effects on corporate governance. I found his approach especially useful under which he concentrated on ‘functional equivalence’. With functional equivalence, he had in mind whether modern technologies replaced the function of an older approach to doing something. As an example, he mentioned the replacement of physical seals (stamps) by e-signatures, which had been allowed by statute in Japan from about two decades ago. Against this background, he asked what tasks advanced technologies will replace in businesses and what this means for corporate governance.

Sumida: I took Professor Kozuka’s analysis as shedding light from a different angle on the structural problems faced by Japan’s large companies, which Hiroto Koda had clearly and unambiguously highlighted in the first session. However, for me, the reason why Professor Kozuka introduced the concept of ‘functional equivalence’ and summed up his talk with this concept, including his vision for the future, was not quite clear. It seems to me that it is a concept for a rather static comparison. I was wondering if it is a concept that should be used when discussing dynamic processes where creative destruction occurs, which is what Professor Sasaki refers to in the last D, disruption. This is a topic I would love to discuss if I have the chance.

The topic of ‘de-stamping’ was indeed a symbolic topic of digitalisation in our country. Electronic signatures were legislated about twenty years ago, but the practice of physical stamping persisted. During the pandemic, the problem of having to come to work just to stamp a document was exposed and became a social problem. De-stamping society has been an important topic in Japan since the start of the pandemic. This example shows why digitalisation in Japan has been delayed. What was your impression of the differences in stance between the guests on this point?

Steffek: I think both approaches, i.e. an approach where one tries to understand what functions technology has and an approach where one tries to understand the changes and disruption caused by technology, can be useful. The first – functional – approach helps to understand what technology does at a task level. The second – dynamic – approach helps to see changes over time. Against this background, I would like to ask whether technology will only replace existing functions or whether technology will also transform businesses more fundamentally? A further question I would like to raise is what effect the changing environment will have on corporate governance. It is not only businesses themselves that are affected by modern technology. Technology also transforms societies, the ways people live and the ways they do business. Will this also affect corporate governance?

Sumida: We discussed the ‘AI Misora Hibari’ case. Japan is home to some of the world’s leading android researchers and robot theatre directors. They have created androids of famous Japanese writers and actors to perform in robot plays. This has raised provocative questions such as: who has the right to bring great people back to life? Are there any limits to what can be shown in an android theatre? Is there a need for ‘Fundamental Android Principles’.Footnote 13

Data remains beyond life, and rights over data are still an unexplored area for the law. In the discussion, it seemed to me that the only viable option for norms is to be principle-based because reality overtakes the rules.

Steffek: The final speaker of this session was Takuya Izumi, Director of the Information, Policy Planning and Coordination Division at the METI. He presented the White Paper on AI Governance. In the meantime, METI has published the final report on ‘AI Governance in Japan’.Footnote 14 A core principle of the AI governance approach presented by Director Izumi is a human-centric approach. He emphasised that good AI governance contributes to businesses solving people’s problems. I could not agree more. Business models that are based on solving real problems that people have will be sustainable. And vice versa, pushing products and services into the market even though people ultimately do not need them will not be sustainable in the long run. Another perspective on this is to ask what the interests of people are. The interests of people are the flip side of their problems. In this sense, the principle that is at the core of METI’s approach to regulating AI is in good company. The OECD, for example, takes a remarkably similar design approach when recommending, for example, that laws and dispute resolution should follow a people-centric design.

Questions for Further Thought

Will corporate governance become instantaneous in the sense that both internal and external governance can relate to data that is comprehensively up-to-date at the time decisions are taken?

How will external corporate governance institutions, such as financial services authorities, have to change their practices if they can base their interventions on live data as opposed to historical data?

Which role will AI play in corporate governance? Will we see self-driving corporations that are managed by AI only?

How will technology change the internal organisation of businesses? Will they become less hierarchical?

What will the effects of technology be on the size of corporations? Will corporations become bigger because technology enables them to minimise the cost of internal organisation? Or will they become smaller because technology facilitates cooperation with others by way of contract?

How can lawmakers ensure that their regulatory principles are not only followed by the legal profession but also by the computing profession, which might be less used to reading laws and regulations?