Background and Context

“No rights, no REDD+.” This was the key message of the Indigenous Peoples caucus as it walked out of the Poznan climate conference in December 2008 to protest the exclusion of rights language in a draft negotiating text on REDD+.Footnote 1 This was not the first nor the last time that the new and ambitious global mechanism for reducing carbon emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, supporting the conservation and sustainable management of forests, and enhancing forest carbon stocks in developing countries (REDD+) negotiated within the United Nations Framework Conference for Climate ChangeFootnote 2 (UNFCCC) would generate such controversy.

The basic idea behind REDD+ is that channeling climate finance from North to South to avoid deforestation and support carbon sequestration in developing country forests can not only contribute to the world’s global climate mitigation efforts but can also protect forests and their critical ecosystems and help alleviate poverty among forest-dependent and rural communities.Footnote 3 Because it has been seen as a relatively inexpensive, simple, and rapid way of reducing an estimated 17 percent of global carbon emissions worldwide,Footnote 4 the development of REDD+ has moved forward with remarkable vigor within the UNFCCC and beyond.Footnote 5 Governments, international organizations, multilateral development banks, conservation and development NGOs, and corporations have established funding, knowledge-sharing, technical assistance, and certification programs to support the pursuit of REDD+ in developing countries.Footnote 6 Across Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean, over sixty governments have initiated multi-year programs of research, capacity-building, and reform to prepare for the implementation of REDD+ and have begun taking national action to reduce carbon emissions originating in their forests and manage international funds received for this purpose (known as jurisdictional REDD+).Footnote 7 In addition, up to 350 projects have been initiated by governments, international organizations, NGOs, corporations, and communities in an effort to reduce carbon emissions from forest-based sources at the local level in over fifty developing countries (known as project-based REDD+).Footnote 8

Having emerged as a “triple-win” solution for forests, climate change, and development, REDD+ has become increasingly entangled with complex debates over the governance of forests, land, and resources in developing countries.Footnote 9 It has most notably attracted significant attention and scrutiny from activists, scholars, and policy-makers due to its controversial implications for the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communitiesFootnote 10 in developing countries.Footnote 11 On the one hand, REDD+ may provide new funds and momentum for the recognition and protection of the traditional lands of Indigenous Peoples and local communities, as well as opportunities to foster their participation in forest governance and support their sustainable livelihoods.Footnote 12 On the other hand, given their technocratic focus on carbon sequestration and potential to generate unintended incentives for land grabbing, REDD+ activities may marginalize the interests and perspectives of forest-dependent populations and dispossess them of their traditional rights to forests, lands, and resources.Footnote 13 This array of potential synergies and tensions between REDD+ and Indigenous and community rights has led some scholars to speak of REDD+ as a “paradox,” since the very same set of factors that are seen as having the capacity to generate benefits for forest-dependent communities are also seen as posing significant risks to their rights, institutions, and livelihoods.Footnote 14

This book seeks to shed light on the REDD+ paradox by providing an in-depth socio-legal study of the implications of REDD+ for the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in developing countries. Broadly speaking, I adopt a new legal realist perspective that draws on empirical research to uncover the limited, yet no less potent, opportunities offered in and around the law for social change and justice.Footnote 15 In particular, I conceive of the development and implementation of REDD+ activities around the world as amounting to a “transnational legal process,” which I define as the construction and conveyance of legal norms across sites and levels of law that transcend the traditional territorial boundaries of sovereign states.Footnote 16 I grapple with two important questions concerning the intersections between the transnational legal process for REDD+ and the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. First, how have Indigenous and community rights been recognized across a range of international and transnational sites of law for REDD+? Second, whether, how, and to what extent has the pursuit of jurisdictional and project-based REDD+ activities affected the recognition and protection of Indigenous and community rights in developing countries? Through a combination of international legal analysis and in-depth empirical research on the pursuit of REDD+ activities in two case study countries, Indonesia and Tanzania, from 2005 to 2014, this book contributes to our understanding of REDD+, its implications for human rights, and the influence of transnational legal processes. In what remains of this chapter, I review the existing literature on the relationship between REDD+ and rights. I then introduce the analytical framework and research design that underlie this book, discuss the significance and originality of my approach and findings, and outline the contents of the chapters that follow.

Existing Knowledge

The relationship between REDD+ and the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities has given rise to a burgeoning body of research across several disciplines. One stream of scholarship produced by legal scholarsFootnote 17 has argued that the design and management of REDD+ programs, policies, and projects should comply with the participatory rights of individuals and communitiesFootnote 18 enshrined in international human rights lawFootnote 19 and recognized through the principle of public participation in international environmental law.Footnote 20 In doing so, these scholars have emphasized that Indigenous Peoples benefit from an enhanced set of procedural rights by virtue of their recognition as “peoples”Footnote 21 and their right to self-determination under international law.Footnote 22 As is recognized in the UNDRIPFootnote 23, ILO Convention 169Footnote 24 and the decisions of numerous international and regional human rights bodies,Footnote 25 Indigenous Peoples have the right to provide or withhold their free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) to activities and measures that affect their rights, lands, and resources.Footnote 26 For their part, local or forest-dependent communities do not possess a distinct statusFootnote 27 or set of rights under international law, nor do they hold explicit collective rights to their traditional lands and resources or to FPIC under any existing international instrument.Footnote 28 They must instead assert a broad set of claims based on general international human rights law, the rights held by Indigenous Peoples, and the land and tenure rights that they may hold under national legal systems.Footnote 29

Legal scholars have also considered whether and how the implementation of REDD+ policies, programs, and projects may affect a range of substantive human rights protected under international law. On the one hand, avoiding deforestation through REDD+ and equitably sharing the benefits generated by climate finance may serve to protect the traditional rights and territories of Indigenous Peoples and local communities, and contribute to their sustainable livelihoods.Footnote 30 On the other hand, any rules and restrictions imposed through a REDD+ program or project on local access to forests or use of resources may interfere with numerous human rights,Footnote 31 including rights to personal security, freedom of movement, and freedom from racial discrimination,Footnote 32 rights to housing, food, water, health, an adequate standard of living, and culture,Footnote 33 and the sui generis rights to land, resources, and culture held by Indigenous PeoplesFootnote 34 under international law.Footnote 35 In this regard, the potential creation, sale, and trading of property rights over the carbon sequestered in trees (known as “carbon rights”) through project-based REDD+ activities have been identified as especially problematic on the grounds that this process of commodification may be contrary to Indigenous conceptions of property, interfere with the unique relationship that Indigenous Peoples enjoy with nature, and serve to dispossess them of their lands and resources.Footnote 36

Legal scholars have expressed a general lack of confidence in the effectiveness of the social and environmental safeguard initiatives that have emerged across multilateral, bilateral, and nongovernmental initiatives for REDD+ to prevent or mitigate its adverse social implications for local populations.Footnote 37 It is worth remembering that the recognition of the status and rights of Indigenous Peoples under international law remains controversial in many developing countries, especially in Africa and Asia. Indeed, many governments in Africa and Asia have denied that the very concept of Indigenous Peoples apply in their countries, arguing that it is the product of European colonial settlement in the Americas and that its application is restricted to that region.Footnote 38 In the face of these challenges, many legal scholars have called for the development of formally binding mechanisms at the international level to ensure the protection of human rights within the context of REDD+, whether through the UNFCCC or established United Nations human rights bodies.Footnote 39

A second strand of research, anchored in environmental studies, has focused on the extent to which REDD+ may support or detract from the recognition and protection of the collective forest and land tenure rights and institutions of local communities,Footnote 40 particularly in terms of the pursuit and implementation of community forestry.Footnote 41 This literature reveals three broad ways in which REDD+ may support the rights and institutions of local communities. First, REDD+ activities may in and of themselves serve as a vehicle for the pursuit of community forestryFootnote 42 or the recognition and protection of rights to forests and land tenure,Footnote 43 due to their purported benefits for reducing deforestation and enhancing carbon sequestration.Footnote 44 On a broader scale, numerous scholars have argued that the adoption and implementation of laws and schemes to clarify and regularize the forest tenure rights of forest-dependent communities should form a pre-condition or starting point for the jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts pursued by developing countries.Footnote 45 In this regard, early studies demonstrate that REDD+ readiness efforts and projects have indeed made some contribution to forest tenure reformsFootnote 46 while also highlighting the complex challenges that they face in addressing the political conflicts and technical challenges that stand in their way.Footnote 47 Second, the equitable distribution of funds for REDD+ activities among local communities (a practice known as “benefit-sharing”) may support their sustainable livelihoods and provide some of the long-term finance required to sustain the implementation of community forestry arrangements.Footnote 48 Third, Indigenous Peoples and local communities may also benefit from being involved in the monitoring, reporting, and verification of forest carbon stocks in the implementation of REDD+ policies, programs, and projects.Footnote 49

On the other hand, many scholars have expressed concerns that REDD+ activities are likely to have adverse consequences for local communities. Many scholars have warned that the technical complexities and national scale of jurisdictional REDD+ activities have the potential to prompt central authorities to seek to assert greater control over forests and accordingly reduce their willingness to devolve authority over forests to local communities.Footnote 50 Moreover, many authors note that the potential of REDD+ funds to make a significant difference to the lives of forest-dependent communities may be constrained by the low price of carbon on voluntary carbon markets.Footnote 51 Given the limitations and inequities of existing forest governance systems, scholars argue that the introduction of funds through REDD+ projects and schemes may create new opportunities for corruption, graft, and capture by central or local elitesFootnote 52 and thus further induce central forest authorities to maintain or increase their control over forests.Footnote 53

Due to the limitations of the social and environmental safeguards that have been developed by multilateral, bilateral, and nongovernmental actors for REDD+ activities,Footnote 54 a number of authors argue that REDD+ activities are unlikely to yield fair and just outcomes for Indigenous Peoples and forest-dependent communities in the absence of broader reforms aimed at improving governance systems and creating locally accountable institutions in the forestry sector.Footnote 55 Many scholars fear that REDD+ may function as a form of environmental governance that promotes technocratic and market-oriented approaches to forest governanceFootnote 56 and marginalizes traditional and community perspectives.Footnote 57 In light of the entrenched political, economic, and legal asymmetries that characterize forest governance in many developing countries,Footnote 58 Ribot and Larson raise important questions about the likelihood that REDD+ may harm, rather than benefit, local populations:

REDD is entering this slanted world with the primary objective of carbon emissions reduction – not justice or equity. If community rights are already limited (…) will they be limited in the future under REDD in the name of carbon sequestration? Who will control forests? What rules for resource use will be developed to meet carbon targets under REDD, who will create and enforce these rules and how might they limit community access to forests for livelihoods? If communities carry new burdens – such as limitations on activities permitted in forests (‘no’ imposed from above) – will they be fairly compensated? Will the rights to forest benefits – this time to carbon funds – once again be captured by outsiders?Footnote 59

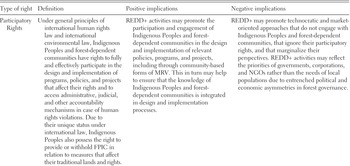

As summarized in Table I.1, the existing literature provides a helpful overview of the range of potential implications of REDD+ activities for the participatory and substantive rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.Footnote 60 Of course, much of this literature was produced in the initial stages of the global operationalization of REDD+, without the benefit of empirical research on its processes and outcomes. Given the advanced stage that REDD+ has reached around the world, the primary purpose of this book lies in subjecting these claims to empirical scrutiny in order to understand whether, how, and to what effect the pursuit of REDD+ has affected the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in developing countries.

Table I.1 Overview of the potential implications of REDD+ for the rights of Indigenous Peoples and forest-dependent communities

Analytical Framework

In order to capture the diverse ways in which REDD+ has affected Indigenous and community rights, I develop and employ an interdisciplinary analytical framework for the study of transnational legal processes. Since Koh first coined this term in the mid-1990s to analyze the multiple pathways through which states internalize rules of international law,Footnote 61 a number of socio-legal scholars, especially Shaffer and Halliday, have expanded the study of these processes by focusing on the broader set of legal norms that may be constructed and conveyed across borders, and the manifold ways in which they may influence economic, social, and political institutions and processes.Footnote 62 This scholarship has dovetailed with work examining the diffusion, transplantation, or translation of legal norms across diverse sites of law.Footnote 63

This rich body of scholarship has five important implications for the study of transnational legal processes. First, it suggests that a heterogeneous array of public and private actors, including international organizations, governments, nongovernmental organizations, corporations, communities, and individuals, are engaged in the construction and conveyance of legal norms across borders.Footnote 64 Second, it posits that a transnational legal process may feature a multiplicity of sites, modes, and forms of ordering that are not subsumed within a state-centric conception of lawFootnote 65 and that encompass and cut across international, transnational, national, and subnational levels of governance.Footnote 66 Third, it conceives of the construction and conveyance of legal norms as multidirectional – taking place horizontally between sites of law located at the same level and vertically from the “top-down” as well as the “bottom-up” across sites of law located at different levels.Footnote 67 Fourth, far from viewing a transnational legal process as entailing the objective creation, interpretation, and application of law, this scholarship recognizes instead that the construction and conveyance of legal norms is contingent on both interest-driven and norm-driven behavior.Footnote 68 Fifth, it stresses the importance of distinguishing between enactment, which consists of the formal acceptance of a legal norm within a site of law, and implementation, which refers to the practical application of a legal norm, as reflected in actual changes in the behavior of public and private actors.Footnote 69 The enactment and implementation of legal norms can have wide-ranging effects within a site of law, by engendering changes in the substance of law and policy, affecting institutions, and shaping the ideas, identities, and behavior of public and private actors.Footnote 70

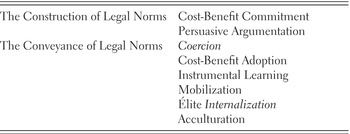

My analytical framework builds on this socio-legal literature by specifying the key causal mechanismsFootnote 71 that drive the construction and conveyance of legal norms in a transnational legal process. Drawing on the findings of political scientists regarding the emergence and effectiveness of international norms,Footnote 72 the domestic influence of international law,Footnote 73 and the nature of transnational processes of policy change,Footnote 74 I identify a range of rationalistFootnote 75 and constructivistFootnote 76 causal mechanisms that underlie the development of legal norms by actors within a site of law (construction) and their transmission in a relatively reified manner from one site of law to another (conveyance).Footnote 77 As such, I assume that both rationalist and constructivist approaches are needed to provide a full account of how law relates to society,Footnote 78 in large part because the relationship between interest-driven behavior and norm-driven behavior often plays a determinative role in the emergence, evolution, and effectiveness of institutions.Footnote 79 That said, I accord little importance to whether a mechanism is best understood as rationalist or constructivist, nor do I aim to prove that one type of mechanism is more causally significant than the other. In presenting these causal mechanisms in the paragraphs that follow, I explain how they operate, specify their scope conditions, and highlight the importance of understanding how they may interact with one another in concurrent or sequential ways. I conclude this presentation of my analytical framework by discussing the relationship between the construction and conveyance of legal norms and delineating how transnational legal processes may result in the transplantation as well as translation of legal norms across sites of law (Table I.2).

Table I.2 The causal mechanisms in transnational legal processes

| The Construction of Legal Norms | Cost-Benefit Commitment |

| Persuasive Argumentation | |

| The Conveyance of Legal Norms | Coercion |

| Cost-Benefit Adoption | |

| Instrumental Learning | |

| Mobilization | |

| Élite Internalization | |

| Acculturation |

This analytical framework is ideally suited for understanding the implications of REDD+ for the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in developing countries. It enables me to trace the causal mechanisms that can explain whether and how legal norms relating to these rights have been constructed and conveyed across multiple forms, sites, and levels of law in the context of REDD+, and to what extent they may meaningfully affect the lives of Indigenous Peoples and local communities on the ground. To be sure, my analytical framework does not do justice to the richness of the many scholarly sources that it draws upon, nor does it dwell on the many important ways in which they may conflict with one another. Rather, its purpose lies in providing the key elements that can be used to analyze and understand a complex transnational legal process like REDD+ that originates in, operates through, and exerts influence upon a diversity of sites of law at the international, transnational, national, and local levels.

The Construction of Legal Norms in a Transnational Legal Process

I understand the construction of legal norms as resulting from the concurrent or sequential operation of two causal mechanisms: cost-benefit commitment and persuasive argumentation. I define cost-benefit commitment as the causal mechanism whereby actors commit to abiding by a certain standard of future behavior in order to maximize utility and achieve cooperative solutions to a collective action problem.Footnote 80 This mechanism posits that self-interested actors develop legal norms based on a rational calculation that the expected benefits of commitment outweigh its costs.Footnote 81 The construction of legal norms through cost-benefit commitment does not take place in a vacuum, however, and builds upon the legal norms and practices present in a site of law in order to craft redesigned solutions to achieve existing objectives or resolve existing problems (what Campbell calls substantive bricolage).Footnote 82 In addition, the development of legal norms through cost-benefit commitment may also take place on the basis of legal norms transmitted from other sites of law. In this context, cost-benefit commitment will involve the rational adjustment or calibration of these legal norms in light of existing legal practices prevailing in a site of law.Footnote 83

I define persuasive argumentationFootnote 84 as the causal mechanism whereby actors construct and internalize a legal norm because they are convinced of its validity and appropriateness as a result of the shared understandings that they have developed with other actors.Footnote 85 Existing research tells us that the construction of legal norms through persuasive argumentation depends upon the purposeful efforts of actors who seek to actively construct persuasive normative framesFootnote 86 on the basis of legal norms prevailing in a site of law or originating from another site of law – a creative process known as framing.Footnote 87 The existing literature also suggests that the effectiveness of persuasive argumentation is facilitated by three important conditions: the existence of a new situation or crisis in which actors are especially open to new normative understandings;Footnote 88 the alignment between emergent or proposed legal norms and the existing legal norms internalized by actors;Footnote 89 and a context in which actors engage in a primarily deliberative or participatory, rather than coercive, form of discourse.Footnote 90

Notwithstanding the very different causal logics that these two mechanisms embody and the different time frames in which they may operate, I view them as complementary explanations for the construction of legal norms within a site of law.Footnote 91 For one, the construction of legal norms can result from the concurrent operation of both the causal mechanism of cost-benefit commitment (in that they embody the legal norms that actors have developed on a cost-benefit basis) and that of persuasive argumentation (in that they reflect the shared understandings that actors have constructed together).Footnote 92 For another, the construction of legal norms can be seen as resulting from a specific temporal sequence in which one causal mechanism may be more important than another at different stages in the construction of legal norms.Footnote 93 For my purposes, it suffices to note that the construction of legal norms within a site of law may be understood as a cycle that may combine or move back and forth between the causal mechanisms of cost-benefit commitment and persuasive argumentation.

The Conveyance of Legal Norms in a Transnational Legal Process

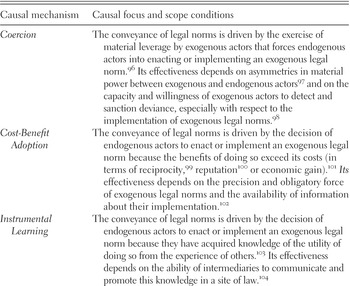

There is rich and extensive literature in lawFootnote 94 and political scienceFootnote 95 on the various causal mechanisms that can explain the transmission or diffusion of laws, norms, policies, and institutions from one context to another. In Table I.3, I draw on this existing scholarship to identify six causal mechanisms that may support the conveyance of legal norms from one site of law to another: coercion, instrumental learning, cost-benefit adoption, mobilization, élite internalization, and acculturation. These causal mechanisms are expressed in generic terms that are sensitive to the pluralism of transnational legal processes, characterized as they may be by public, private, and hybrid forms of law and the multiple directions in which the conveyance of legal norms may operate – horizontally and vertically, from the top-down and the bottom-up, from, and to, multiple sites of law at different levels.Footnote 111 In describing these mechanisms, I accordingly distinguish legal norms and actors based on whether they are “endogenous” (in that they are primarily affiliated with a given site of law) or “exogenous” (in that they originate outside this given site of law).Footnote 112

Table I.3 The causal mechanisms of the conveyance of legal norms in a transnational legal process

| Causal mechanism | Causal focus and scope conditions |

|---|---|

| Coercion | The conveyance of legal norms is driven by the exercise of material leverage by exogenous actors that forces endogenous actors into enacting or implementing an exogenous legal norm.Footnote 96 Its effectiveness depends on asymmetries in material power between exogenous and endogenous actorsFootnote 97 and on the capacity and willingness of exogenous actors to detect and sanction deviance, especially with respect to the implementation of exogenous legal norms.Footnote 98 |

| Cost-Benefit Adoption | The conveyance of legal norms is driven by the decision of endogenous actors to enact or implement an exogenous legal norm because the benefits of doing so exceed its costs (in terms of reciprocity,Footnote 99 reputationFootnote 100 or economic gain).Footnote 101 Its effectiveness depends on the precision and obligatory force of exogenous legal norms and the availability of information about their implementation.Footnote 102 |

| Instrumental Learning | The conveyance of legal norms is driven by the decision of endogenous actors to enact or implement an exogenous legal norm because they have acquired knowledge of the utility of doing so from the experience of others.Footnote 103 Its effectiveness depends on the ability of intermediaries to communicate and promote this knowledge in a site of law.Footnote 104 |

| Mobilization | The conveyance of legal norms is driven by the political or legal pressure exerted upon endogenous actors by other endogenous actors.Footnote 105 Its effectiveness depends on the institutional, ideational, and material conditions that may favor or constrain the emergence and mobilization of endogenous interest groups and coalitions in favor of the conveyance of exogenous legal norms.Footnote 106 |

| Élite Internalization | The conveyance of legal norms is driven by the internalization of exogenous legal norms by endogenous élite as a result of their participation in persuasive argumentation with exogenous actors.Footnote 107 Its effectiveness depends on whether endogenous élites have the authority and capacity to enact and implement legal norms in a site of law.Footnote 108 |

| Acculturation | The conveyance of legal norms is driven by the social and cognitive need for endogenous actors to enact or implement the exogenous legal norms widely accepted within their broader transnational reference group.Footnote 109 Its effectiveness depends on the importance that the endogenous actor accords to their transnational reference group for their identity and the intensity and duration of their exposure to this group.Footnote 110 |

As a result of the plurality of actors that may be involved in a given transnational legal process and the various strategies that they may pursue to support the transmission of legal norms across sites of law, transnational legal processes may feature the concurrent or sequential operation of numerous causal mechanisms of conveyance.Footnote 113 Two factors underlie the importance of distinguishing between different causal mechanisms. First, as argued by Morin and Gold, these causal mechanisms may interact with one another in symbiotic ways to make the conveyance of legal norms more likely in a given case as well as across a population of cases over time.Footnote 114 Second, these causal mechanisms may have differing implications for the enactment and implementation of exogenous legal norms. Many causal mechanisms of conveyance may result in an initial gap between how legal norms are formally enacted in a site of law and how they are implemented through actual changes in the practices of actors.Footnote 115 The study of the transnational conveyance of legal norms thus requires paying attention to how interactions between causal mechanisms may, whether concurrently or sequentially, explain how and to what extent legal norms may be conveyed to, and eventually implemented in, a site of law.Footnote 116

The Causal Pathways of a Transnational Legal Process

As is reflected in the various causal mechanisms discussed above, my analytical framework assumes that legal norms in a transnational legal process can operate both as “works-in-progress” that actors may construct together within sites of law as well as “fixed entities” whose meaning and effects remain relatively stable as they are conveyed from one site of law to another.Footnote 117 Understanding that legal norms can be dynamic as well as static enables me to identify two broad types of causal pathways that a transnational legal process may follow.

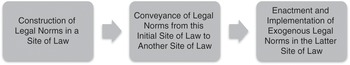

In the first pathway shown in Figure I.1, a transnational legal process begins with the construction of legal norms in an initial site of law. The subsequent conveyance of legal norms from this site of law to another then functions as an “exogenous shock”Footnote 118 that results in the enactment and implementation of exogenous legal norms. This pathway is consistent with accounts of legal transplantation and explains how transnational legal processes may result in the broad diffusion of legal norms and engender the convergence of law across multiple sites.Footnote 119

Figure I.1 The transplantation of legal norms through a transnational legal process

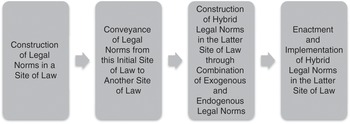

In the second pathway illustrated in Figure I.2, the transnational legal process does not end with the initial conveyance of exogenous legal norms from one site of law to another. Instead, the conveyance of exogenous legal norms triggers the construction of hybrid legal norms,Footnote 120 thereby reflecting the mediating influence of sites of law.Footnote 121 There are several factors that can account for the potential of transnational legal processes to engender hybridity: the natural ambiguity of legal norms,Footnote 122 the differing interests and norms that may shape the engagement of actors in the construction and conveyance of legal norms,Footnote 123 and the political struggles that the conveyance and translation of legal norms may trigger.Footnote 124 This second pathway is antithetical to the notion that legal norms can be easily transplanted in a unidirectional manner from one site of law to another,Footnote 125 without variations in their substance or effectiveness and without generating dynamic feedback effects.Footnote 126 It is instead consistent with scholarship that focuses on the translation of legal normsFootnote 127 and helps explain how the effects of transnational legal processes across sites of law may be heterogeneous.Footnote 128 Given that many scholars view the construction of hybrid legal norms as integral to the durability and effectiveness of exogenous legal norms in a site of law,Footnote 129 this second pathway provides an important way of analyzing the impacts of transnational legal processes on the behavior of actors in the long-term.

Figure I.2 The translation of legal norms through a transnational legal process

The takeaway point here is that the causal mechanisms of the construction and conveyance of legal norms may interact with one another in a dynamic cycle that can yield a variety of different outcomes, at different stages, within a particular site of law. This view makes it possible to account for both the divergent and the convergent outcomes to which a transnational legal process may give rise as well as to develop complex causal pathways that can explain how transnational legal processes may emerge, evolve, and exert influence across one or more sites of law over time.Footnote 130

Research Design

My study of the construction and conveyance of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the domain of REDD+ employs a research method known as “explaining-outcome process-tracing.”Footnote 131 Process-tracing is generally used for making within-case inferences about the role of causal mechanisms in the processes that link causes and outcomes.Footnote 132 Explaining-outcome process-tracing specifically aims to trace the complex combination of systematic and nonsystematic causal mechanisms that produced a particular outcome in a single case.Footnote 133 It tends to be characterized by theoretical eclecticism rather than parsimony.Footnote 134 It “offers complex causal stories that incorporate different types of mechanisms as defined and used in diverse research traditions” as well as “seeks to trace the problem-specific interactions among a wide range of mechanisms operating within or across different domains and levels of social reality.”Footnote 135 Process-tracing is especially appropriate for research that involves a particularly interesting or puzzling outcome that cannot be explained by existing theories.Footnote 136

Rather than focus on the presence of dependent or independent variables, case selection in the context of process-tracing requires selecting cases that make it possible to trace the causal mechanisms that link one or more causes (X) to a particular outcome (Y).Footnote 137 I selected Indonesia and Tanzania as two case studies for this book from among the more than sixty countriesFootnote 138 engaged in the pursuit of REDD+ on the basis of three criteria. First, both Indonesia and Tanzania have made significant progress in their jurisdictional REDD+ readiness activities, have been actively involved in the principal multilateral, bilateral, and nongovernmental initiatives for REDD+, and have hosted multiple REDD+ projects.Footnote 139 Second, Indigenous and community rights were ultimately recognized or protected as part of the jurisdictional REDD+ laws, policies, and programs that these countries have adopted or the project-based REDD+ activities that they have hosted, thus enabling me to study the causal mechanisms linking X and Y. Third, given the historical resistance of the governments of Indonesia and Tanzania to the recognition and protection of these rights in other contexts, these two cases form the sort of “least-likely” case that is often the focus of in-depth qualitative research.Footnote 140

Although I did not select these two countries based on comparative logic, they do differ in a number of ways. Indonesia is a middle-income country where the principal drivers of deforestation are expanding forestry, mining, and agricultural sectors that are integrated into global supply chains. The underlying causes of deforestation in Indonesia include the resource-driven economic policies of national and regional governments, growing international demand for commodities, and the high levels of collusion and corruption that encumber the effectiveness of the country’s institutions and systems of forest governance.Footnote 141 By contrast, Tanzania is a least-developed country in which forests and their resources support the livelihoods of rural communities. The main drivers of deforestation in Tanzania are thus local in nature, and most notably include the conversion and use of forests for subsistence-based agriculture, livestock grazing, firewood and charcoal production, and small-scale logging.Footnote 142 Furthermore, whereas the governance of forests in Indonesia remains highly centralized and gives rise to frequent disputes between governments and local communities over the recognition of local forest tenure, resource rights, and institutions,Footnote 143 Tanzania has developed one of the most favorable policy environments for the pursuit of community forestry in Africa.Footnote 144 As I explain in Chapter 6, these differences are relevant to understanding the scope conditions of the causal mechanisms that explain whether, how, and to what effect actors may construct and convey Indigenous and community rights in the context of REDD+ activities in a developing country.

I employed multiple methods and sources of data collection to operationalize the explaining-outcome process-tracing for this book.Footnote 145 First, I analyzed the ninety-four semi-structured élite interviews that I conducted with individuals affiliated with international organizations, developing and developed country governments, corporations, and NGOs actively working on REDD+ around the world.Footnote 146 Second, I drew on the observations I gathered through my participation as a civil society delegate and legal expert in multiple legal and policy processes relating to REDD+ from 2007 to 2014.Footnote 147 This participation-observation across multiple sites over time enabled me to get a better sense of the evolving views of different actors with respect to REDD+ and its implications for rights.Footnote 148 Third, I analyzed the extensive collection of laws, policies, reports, contracts, and other documentation relevant to REDD+ produced by international organizations, developing and developed country governments, corporations, and NGOs that I gathered during my fieldwork. Fourth, I drew on the emails that I exchanged with several of my interviewees and other sources to obtain documents as well as clarify points of information throughout my fieldwork and the process of drafting my dissertation. Fifth, I relied on the secondary literature that has been produced by scholars on REDD+ and more broadly on the international organizations, developing and developed country governments, corporations, and NGOs that have played a key role in its development and implementation. Sixth and finally, I built an original data set on the implications of 38 REDD+ projects for the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in Indonesia and Tanzania.Footnote 149 By triangulating across these different sources of dataFootnote 150 and carefully assessing their reliability,Footnote 151 I was able to trace the role of different causal mechanisms in the construction and conveyance of Indigenous and community rights in the transnational legal process for REDD+ in my two case study countries.

Originality and Significance

The original analysis and findings in this book make several contributions to the existing literature. First and foremost, this book contributes to literature examining the implications that REDD+ activities may hold for the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in developing countries. Much of the existing scholarship on REDD+ and rights is replete with theoretically plausible, yet no less speculative, claims and arguments about the effects of REDD+ on Indigenous and community rights. The little empirical research that does exist on this topic has focused on the processes and outcomes associated with REDD+ projects implemented at the local level,Footnote 152 leaving the question of how rights have been considered within the context of jurisdictional REDD+ activities at the national level largely unexplored. Given the advanced stage that REDD+ has reached around the world, I have been able to undertake novel empirical research and analysis to understand how and to what effect the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities have been constructed and conveyed at national and local levels.

Many scholars hypothesize that REDD+ outcomes are being driven by entrenched power asymmetries in forest governance that new interventions or instruments like REDD+ are incapable of changing and may, worse still, exacerbate.Footnote 153 With a view to capturing the ways in which law may offer limited, yet no less potent, support for change in transnational contexts,Footnote 154 I have sought to understand the risks as well as the opportunities that REDD+ offers for the recognition and protection of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in developing countries. On the whole, I argue that the pursuit of REDD+ has functioned as something of an exogenous shock disrupting the traditional patterns of the development and implementation of legal norms relating to the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in Indonesia and Tanzania. My findings demonstrate that jurisdictional and project-based REDD+ activities have, through different causal pathways, provided meaningful opportunities for developing and developed country governments, international organizations, Indigenous Peoples, local communities, NGOs, and even private firms to convey, from above and from below, these rights to national and local sites of law. For instance, both the Indonesian and Tanzanian governments have, for the first time, recognized rights such as the right to free, prior, and informed consent in the context of their national REDD+ policy processes. These developments have not taken place in a vacuum and have been facilitated by broader developments relating to the global emergence of Indigenous rights, the growing relevance of human rights to the fields of climate change and forest conservation, and ongoing processes of democratization in Indonesia and Tanzania.

At the same time, my findings do not suggest that REDD+ has functioned as a panacea either. Across Indonesia and Tanzania, the transnational legal process for REDD+ has resulted in the translation of new hybrid legal norms that reflect the resilience and mediating influence of national legal systems and politics. Traditional resistance against the concept of Indigenous Peoples has meant that their rights have either been recognized alongside the rights of forest-dependent communities (as has been the case in Indonesia) or that they have been translated as applying to forest-dependent communities only (as has been the case in Tanzania). Moreover, the recognition and implementation of the participatory rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities (such as rights to full and effective participation or to free, prior, and informed consent) has been relatively more effectual than the recognition and implementation of their substantive rights (such as rights to forests, land tenure, and resources, or livelihoods). These disparities in outcomes give some credence to the expectations of scholars regarding the limitations of REDD+ for the promotion of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

By answering important questions about the construction and conveyance of Indigenous and community rights in the context of REDD+, this book also makes a timely and important contribution to an emerging body of knowledge on the law and governance of REDD+.Footnote 155 Indeed, understanding how the pursuit of REDD+ has been and can be reconciled with important social objectives such as the protection of human rights speaks to larger debates about the objectives, challenges, opportunities, effectiveness, and prospects of REDD+.Footnote 156 Rather than argue that there is an inherent trade-off between the broader effectiveness of REDD+ and the protection of human rights, my research suggests that the underlying ineffectiveness of REDD+ as an instrument has provided unexpected opportunities for the recognition and protection of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in developing countries.

Lastly, as one of the first major empirical studies of a transnational legal process to build on the recent work of Shaffer and Halliday,Footnote 157 this book contributes to the socio-legal study of law in a number of ways. To begin with, my research confirms the methodological importance of adopting a legal pluralist perspective for the study of transnational legal processes. Legal pluralism is critical for uncovering whether and how public and private actors may construct and convey legal norms within a complex transnational legal process like REDD+ that emanates from the intersections of two transnational regime complexes (one for climate change,Footnote 158 the other for forestry)Footnote 159 and features a multiplicity of forms, sites, and levels of normativity. Moreover, this book illustrates the value of understanding a transnational legal process as a cycle that moves back and forth between the construction and conveyance of legal norms, having the potential to yield homogeneous as well as heterogeneous outcomes across sites of law. Whereas there tends to be a bias in favor of finding evidence for the diffusion of norms in much of the political science literature,Footnote 160 my careful study of the interpretation and application of the status and rights of Indigenous Peoples across multiple sites of law reveals that transnational legal processes may, among other outcomes, lead to the translation of legal norms rather than their transplantation or may fail to engender their transmission altogether. Finally, this book illustrates the utility of identifying and studying the various causal mechanisms that drive the construction and conveyance of legal norms to produce a complex and theoretically eclectic account of a transnational legal process. By developing an analytical framework that builds bridges between political science and socio-legal studies and rigorously employing process-tracing to draw causal inferences about the nature and influence of legal norms in a transnational context, it offers a number of important methodological lessons for the study of legal phenomena in a globalizing world.Footnote 161

Overview

The book proceeds as follows. In Chapter 1, I provide an overview of the transnational legal process for REDD+. I begin by presenting the origins and scope of the transnational legal process for REDD+. I then identify the multiplicity of sites of law through which it has evolved at the international, transnational, national, and local levels. I conclude by discussing the increasingly complex character of the transnational legal process for REDD+ and, most notably, by outlining the different pathways that exist for the conveyance of legal norms to developing countries participating in or hosting REDD+ activities.

In Chapter 2, I examine how the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities have been addressed by some of the most influential international and transnational sites of law for REDD+. To begin with, I describe how human rights issues first emerged in the transnational legal process for REDD+. Next, I analyze the recognition of Indigenous and community rights in the context of the UNFCCC; the two leading multilateral programs for REDD+ (the World Bank Forest Climate Partnership Facility and the UN-REDD Programme); a multi-stakeholder safeguards initiative for jurisdictional REDD+ (the REDD+ SES); and a leading nongovernmental certification program for project-based REDD+ (the Climate, Community & Biodiversity Alliance (CCBA)). I conclude by highlighting some of the key differences that have emerged in relation to rights-related issues across these different sites of law.

In Chapters 3 and 4, I trace the conveyance and construction of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities through the implementation of jurisdictional REDD+ activities in Indonesia and Tanzania. I begin by reviewing the broader context in which jurisdictional REDD+ activities have been pursued in these countries, discussing the nature and importance of forests, the principal drivers of deforestation, the role of local communities in forest governance, and the status and rights of Indigenous Peoples. I then describe the history and governance of the jurisdictional REDD+ readiness phase in both countries, outlining the roles played by various domestic and international actors in its design and implementation. Next, I provide an account and explanation of the conveyance and construction of legal norms relating to the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the context of the development of their national strategies and safeguard policies for REDD+. I conclude by reflecting on the outcomes of the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ in Indonesia and Tanzania and their implications for the recognition and protection of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the long-term.

In Chapter 5, I analyze the conveyance and construction of legal norms relating to the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the context of project-based REDD+ activities implemented at the local level. I begin by providing an overview of the nature, scale, and operation of the transnational market for project-based REDD+. I then examine how the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities have been recognized and protected through the pursuit of project-based REDD+ activities in Indonesia and Tanzania. Next, I offer an explanation of the conveyance and construction of these rights within REDD+ projects implemented in both countries. I conclude by reflecting on the broad outcomes of the pursuit of project-based REDD+ activities and their implications for the recognition and protection of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the long-term within the carbon market.

In Chapter 6, I compare the conveyance and construction of rights through REDD+ activities developed and implemented in Indonesia and Tanzania. Although I did not select these two countries on the basis of variations in initial conditions or eventual outcomes relevant to the recognition and protection of rights, a number of lessons can nonetheless be drawn from a comparison of experiences across sites and levels of law in these two countries. I begin by discussing findings that relate to rights in the context of the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ activities at the national level, before turning to the development and implementation of project-based REDD+ activities at the local level. I conclude with a global comparison of the intersections between rights and various REDD+ activities in these two countries, and highlight the mediating influence of national laws and politics in the pursuit of REDD+ at various levels.

In the concluding chapter, I build on my research findings in three ways. I begin by reviewing and discussing the main findings from this book that pertain to the complex relationship between the transnational legal process for REDD+ and the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. Next, I identify the questions and implications that my findings raise for scholarship on REDD+ as well as the nature and influence of transnational legal processes. I conclude by addressing the implications of this book for practitioners and activists working to build synergies between the pursuit of REDD+ and the promotion of human rights.