No Broadway team setting out to write songs and music for a show – not even Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim – can decide to compose an iconic score. Only posterity accords such status, when the music and lyrics remain ubiquitous for later generations. Numerous scores from the 1940s through the 1960s are iconic – Oklahoma! (1943), South Pacific (1949), Guys and Dolls (1950), My Fair Lady (1956), The Sound of Music (1959), and Fiddler on the Roof (1964), to name several – their popularity driven by successful original cast albums, film versions, and songs that have remained well known outside of productions. Certainly, these three conditions exist for West Side Story. The original cast album is still famous, what Nigel Simeone calls ‘ … the most enduring representation of the show in its “original” form … ’1 After the musical played on Broadway for over two years – interrupted by a national tour – it was seen as a memorable, artistic show with ground-breaking use of dance and a score that featured unusually effective musico-dramatic unification. The guarantee of its future came from the first, spectacularly successful film (United Artists, 1961), which won ten Academy Awards and grossed $44,061,777 worldwide.2 Several songs in the score are still popular, especially ‘Maria’, ‘Tonight’, and ‘Somewhere’. These three factors, plus the work’s effective modern retelling of Romeo and Juliet and its striking commentary on racism in the United States, have helped keep the work current. West Side Story artistically shines a bright light on some serious problems in the United States and calls upon its citizens to be better versions of themselves, a challenge that retains as much resonance today as it had in 1957. The property’s appeal has been enhanced by Steven Spielberg’s 2021 film version, which features an intelligent, sensitive rendering of the music.

In this chapter we focus on the score – music and lyrics – that lies at any show’s heart, but in West Side Story the importance of dance raises music to an even more significant position. Unlike the case in most Broadway scores, Bernstein the songwriter wrote the dance music. Bernstein’s hand in West Side Story also included the orchestration, in which he supervised the efforts of Sid Ramin and Irwin Kostal. Then, as if the composer were not already sufficiently encumbered, Bernstein also played a major role in teaching the challenging music to the cast. With Stephen Sondheim, he formed a memorable song-writing team that combined Bernstein’s melodic and rhythmic invention with Sondheim’s mastery of language and rhyme. The lyricist aired his dislike for some of his work for West Side Story, but he did not dampen the world’s enthusiasm for the show’s score.3 This chapter approaches West Side Story’s score from four different angles: its creation, orchestrations, Bernstein’s efforts to unify the work through musical associations, and description of individual numbers. Important sources on the show’s score include books by Nigel Simeone, Elizabeth A. Wells, and chapters in books by Joseph P. Swain, Geoffrey Block, Katherine Baber, Helen Smith, and Paul R. Laird.4

Creation

Seeds for the West Side Story score were sown in Bernstein’s earlier collaborations with Jerome Robbins. In 1943–44, they created the sparkling ballet Fancy Free, a humorous look at three sailors on leave in New York City. Its similarity with West Side Story comes in the use of various social dances in both choreography and music along with jazz and blues references, but Fancy Free includes only swing references while Bernstein accessed later jazz styles in West Side Story.5 The two collaborators joined forces with Betty Comden, Adolph Green, and George Abbott to develop the Broadway musical On the Town, which opened on 28 December 1944 and, like Fancy Free, demonstrated how effectively the artists could reference popular culture in wartime America.6 Robbins and Bernstein collaborated on the ballet Facsimile in 1947, a serious, introspective work that did not land with audiences, who were probably hoping for a repeat of Fancy Free’s high spirits. In subsequent years, Robbins choreographed Bernstein’s Symphony No. 2, The Age of Anxiety (1950), and provided uncredited choreography to his music in Wonderful Town (1953).7 By the time they collaborated on West Side Story, Bernstein understood intuitively what Robbins wanted from music to inspire movements and the choreographer had a deep knowledge of Bernstein’s musical style and affective range.

It is not only the works that Bernstein wrote for choreography by Robbins that foreshadow his music for West Side Story. His ability to compose a melody that would fit into a score for musical theatre dates back to his Symphony No. 1, Jeremiah (1942), heard in the second movement, ‘Profanation’. Beginning seven measures before rehearsal 20, one hears a lyrical, compelling theme in mixed meters. With appropriate text, the melody would fit into a scene featuring Tony and Maria. Bernstein’s Symphony No. 2, The Age of Anxiety (1949), foreshadows West Side Story in the ‘Masque’ with aspects of bop in both solo piano and orchestra, every bit as evocative as the composer’s references to cool jazz and bop in ‘Cool’. The gritty score to West Side Story includes dissonant harmonies, syncopations, and cross-rhythms, such as in the ‘Prologue’ and ‘The Rumble’, similar to what one hears often in Bernstein’s film score to On the Waterfront. This music effectively underscores urban life in the 1950s, an association described in detail by Anthony Bushard.8 The film also includes music for lovers that resembles ‘Tonight’ and ‘Somewhere’. Bernstein’s use of Latin musical tropes in West Side Story also appeared earlier in his output, including the ‘Danzon’ [sic] variation from Fancy Free and Conchtown (1941), a sketch for a ballet that became the song ‘America’.

Robbins conceived the idea of updating Romeo and Juliet in January 1949 and interested Bernstein and playwright Arthur Laurents in the project.9 Laurents sent the composer a draft of four scenes for East Side Story (focusing on Jewish/Catholic tensions) in May, but work stalled and they abandoned the project for six years. In 1955, Laurents and Bernstein pitched another idea to Robbins, but he held out for an adaptation of Romeo and Juliet.10 In August 1955, the two writers realized that the show’s plot could involve youth gangs in New York City, an idea that Robbins liked, and progress resumed. Bernstein planned to write the lyrics, but with simultaneous work on Candide, guest conducting, and his television shows for Omnibus, he needed assistance. Laurents had a young friend, Stephen Sondheim, whom he suggested as a possible lyricist. Bernstein and Sondheim hit it off, sharing their love for difficult word puzzles when they reached a creative impasse. Sondheim wanted to write music, not just lyrics, but his mentor Oscar Hammerstein II and agent Flora Roberts advised him to work with such Broadway successes as Bernstein, Laurents, and Robbins.11 Sondheim and Bernstein began as co-lyricists; the composer later allowed his collaborator full credit. Extensive work began between the four men about November 1955 and lasted until March 1956, when Bernstein concentrated on Candide before it opened in December. Progress ceased on West Side Story for about a year, but most of the Act 1 music had been written.

Candide closed in February 1957, the month that the collaborators resumed work on West Side Story. Some of Bernstein’s music travelled between the two scores; for example, the material that became the songs ‘One Hand, One Heart’ and ‘Gee, Officer Krupke’ started in Candide.12 Work on music for Act 2 continued into the summer. Auditions occurred in the spring and rehearsals lasted from June to August; Simeone shows the score’s state before rehearsals with a list of numbers from perhaps May.13 The score changed considerably during rehearsals, but the music was pretty much set before they opened in Washington, DC on 19 August. Bernstein and Sondheim wrote their last song, ‘Something’s Coming’, in early August, when the collaborators determined that Tony needed a song that would define his character.14

Robbins allowed that the romantic leads might be singers but insisted that the remainder of the cast be dancers first.15 Bernstein did not spare the performers with his score, which was more difficult to sing than the typical Broadway fare of the 1950s. Bernstein (and perhaps Sondheim)16 helped alleviate the challenge by aiding in teaching the cast material like the vocal intricacies of the ‘Tonight’ (Quintet) and ‘A Boy Like That’. Carol Lawrence, who played Maria, reports that Bernstein ‘ … would work with each of us on an individual basis for hours … ’,17 and Chita Rivera, the original Anita, has also recalled working personally with Bernstein on ‘A Boy Like That’: ‘ … he taught me how to hit those notes … ’18 The composer did this while continuing to provide needed revisions and new music, and while working on the show’s orchestrations with Sid Ramin and Irwin Kostal.

Orchestrations

Bernstein asked his friend Sid Ramin to help him with the show’s orchestrations on 20 June 1957.19 Bernstein was five months older; they had met in their Boston neighbourhood at about age 12, bonding over their love for music. In their teens, Ramin for a time studied piano and music theory with Bernstein, and later music theory, especially related to jazz, starting in March 1937 when Bernstein was a student at Harvard.20 Ramin spent World War II in the US Army scoring music for instrumental ensembles and then entered the field after the war, becoming a leading arranger for radio, television, and recordings. He orchestrated occasionally for theatre when called into projects by friends, assisting for example with Bernstein’s score for Wonderful Town (1953), pulled in by Robert ‘Red’ Ginzler, his collaborator in arranging music for Milton Berle’s television show. Ramin was wary of Bernstein’s invitation to work on West Side Story because he doubted that he could adequately cope with Bernstein’s classical influences. Ramin asked Irwin Kostal if he might be interested in joining the team. Kostal was similarly a successful arranger of commercial music, but he had also studied classical scores. Bernstein welcomed Kostal, and the three met for the first time on 26 June. The credit line for the show reads ‘Orchestrations by Leonard Bernstein with Sid Ramin and Irwin Kostal’, a process executed through what Ramin described as ‘pre-orchestration’ and ‘post-orchestration’ meetings. For each number that Bernstein wrote, the three men looked through the piano/vocal score, discussing possibilities and noting places where he provided instrumental suggestions. Ramin has called the scores and instructions that the composer provided them ‘ … the most complete and detailed he ever worked with in the theater’.21 Ramin and Kostal would then prepare an orchestrated draft for Bernstein, who ‘ … literally proofread what we wrote’.22 Bernstein reviewed their work in detail, as may be seen in numerous manuscripts in the Sid Ramin Papers at the Columbia University Archive. All of the scores are written in the hands of Ramin and Kostal and most include Bernstein’s changes in red and green pencil. Two drafts that are especially revelatory are of ‘America’ and ‘The Rumble’, manuscripts that are smaller than most of the scores and appear to be earlier versions with copious marking in the composer’s hand.23 Kostal remembered Bernstein’s great interest in the process: ‘He took keen delight in his own creativity and jumped for joy whenever Sid or I added a little originality of our own. He sometimes would look at one of our scores and say, “Who said orchestration couldn’t be creative?”’24

One of the most important aspects of orchestrating for a show is deciding what instruments to use. Bernstein’s contract for West Side Story stated that there would be twenty-six to thirty musicians; the final number was twenty-eight.25 Extant documentation shows Bernstein trying out various possibilities of twenty-eight instrumentalists; the final configuration included: a wide palette of reed sounds with the unusual provision for bassoon only in the fifth reed book, played by Bernstein’s friend Sanford Sharoff (a friend from their student days at Curtis); seven brass instruments for a score full of jazz references and loud, violent moments in the dances; parts for two percussionists, one handling the trap set and the other playing a plethora of other instruments, including numerous Latin sounds; keyboard; guitarist; and a string section without violas.26

In a musical like West Side Story, where the goal was an organic whole in service of story and characterization, the orchestration must contribute to that process. There are three basic soundscapes: (1) the Jets, based on various types of modern jazz and irregular rhythms and dissonances of twentieth-century concert music, often heard in brass, saxophones, and appropriate percussion; (2) the Sharks with various types of Latin music, dominated by winds and appropriate percussion instruments; and (3) Tony and Maria with rich use of strings, woodwinds for colour, and muted brass. These soundscapes pervade songs and dances associated with these characters, as may be seen in this brief review of the score. The ‘Prologue’ offers the Jets soundscape with prominent use of saxophones, brass, double bass, piano, and sinister sounds from pitched drums. The ‘Jet Song’ features similar accompaniment, but ‘Something’s Coming’ carries a more subtle effect. In this, Tony’s ‘I Want’ song, one hears an approximation of a big band but more use of strings, a combination of the first and third soundscapes. An example of specific word-painting by the orchestra occurs under the text ‘The air is humming … ’ (OCR57, track 2, 1′56″), accompanied by tremolo in the first four violin parts and harmonics in the other three. The ‘Dance at the Gym’ includes a contrast of soundscapes: the first in the opening ‘Blues’ to accompany the Jets dancing, the second dominating the ‘Mambo’ and the gentle ‘Cha-Cha’. The ‘Meeting Scene’, ‘Maria’, and ‘Balcony Scene’ mostly evoke the third soundscape, but perhaps because Tony’s lover is Hispanic, Bernstein also introduced elements of Latin music: for example, the tresillo rhythm in ‘Maria’ played by bassoon, electric guitar, and string bass; and the pulsating eighth notes of a beguine rhythm in strings and woodwinds in ‘Tonight’. ‘America’ offers the Latin soundscape with appropriate percussion. The orchestra reacts to such lines as ‘tropical breezes’ (OCR57, track 6, 0′26″) and ‘tropic diseases’ (0′45″) and provides sarcastic laughter supporting Anita in staccato eighth notes in two flutes, B-flat clarinet, bassoon, all of the brass, trap set, and piano (1′42″). ‘Cool’, marked ‘Solid and boppy’, is in the Jets soundscape with muted brass, restrained use of woodwinds, vibraphone, and trap set when imitating cool jazz and more of a bop big band in the aggressive moments. ‘One Hand, One Heart’ returns to the soundscape intended for the lovers with touching use of the orchestra in the underscoring. Orchestration in the ‘Tonight’ (Quintet) includes material from all three soundscapes describing various characters as they sing. For example, the music for the gangs constitutes a complex march accompanied by brief fanfare interjections in the brass, a bass line in 3/4 in the low strings, and staccato eighth notes in woodwind and upper strings. Just before Anita enters at 1′07″, ascending lip smears in alto and tenor saxophone underscore her anticipation of a romantic rendezvous with Bernardo. When Tony at 1′25″ begins his solo verse of ‘Tonight’, aspects of the accompaniment are reminiscent of what one hears in the earlier ‘Balcony Scene’, but the pulsating rhythm played in several instruments is different, built instead from syncopations and off-beats. ‘The Rumble’, which concludes Act 1, returns to the violence of the gang world with a harshness that is striking in a Broadway musical and pushes the pit orchestra to its limits. Here Bernstein approaches some of the most violent music that he ever wrote, like the ‘Din-Torah’ from Symphony No. 3, Kaddish, and shocking moments from On the Waterfront.

‘I Feel Pretty’ opens Act 2 with striking contrast to ‘The Rumble’. Strings and high woodwinds carry a heavy load here, with trumpets for emphasis and some Iberian/flamenco sounds: Spanish guitar, castanets, tambourine, and onstage clapping. The ‘Ballet Sequence’ includes ‘Somewhere’, in which the accompaniment returns to the third soundscape, but the segment also draws from ‘Maria’, the ‘Cha-Cha’, ‘Prologue’, and ‘The Rumble’, referencing other soundscapes. Bernstein placed ‘Gee, Officer Krupke’ in a unique soundscape for the show, identified by the rubric ‘Fast, vaudeville style’. The song’s accompaniment includes an oom-pah pattern in strings, piano, and percussion with the vocal melody sometimes doubled and harmonized in thirds and punctuated by moments of full orchestra and slapstick effects. The final song is the double number ‘A Boy Like That/I Have a Love’, another collision between soundscapes. Anita has spent the show surrounded with Latin music, but as she tears into Maria the music is reminiscent of ‘The Rumble’ with similar dissonance and rhythmic irregularity. The orchestration offers deep sonorities: three bass clarinets, bassoon, seven muted brass instruments growling low in their ranges, and marcato strings. A distinctive moment occurs in the song’s B section as various instruments double Anita’s vocal line – bassoon, and later flute, violin, and cello – driving her to the climax of her line on the words ‘heart’ and ‘smart’ (OCR57, track 14, 0′40″-0′42″). When Maria interrupts Anita at 1′09”, the soprano is doubled by flute and three violins – not unlike her typical soundscape – but Anita’s accompaniment with lighter scoring continues as they sing in counterpoint. The heavier scoring returns for a moment just before 1′47″ as Maria stops her friend with the words ‘You should know better … ’ The accompaniment of ‘I Have a Love’ is similar to what sounds in Maria’s solo sections of the ‘Balcony Scene’, pulsating with restrained syncopations or long chords in woodwinds and strings or doubling the melody. Instruments state snippets of her melody during long notes at the ends of phrases, like horn 1 at 0′28″ (OCR57, track 15). The orchestra effectively supports the number’s climax and Maria’s final duet with Anita. The ‘Taunting Scene’ resides within Anita’s usual soundscape based on Latin music. The show’s finale is a lightly scored version of the close of the ‘Ballet Sequence’, a restrained close for a show where the orchestra often provides considerable dramatic punch.

Musico-Dramatic Unification in the Score

The notion of a musical idea returning to underline a textual or dramatic association when words have been set by a composer is a venerable practice. It was an important part of Renaissance madrigals and motets and continued throughout the Baroque, assuming a structural significance in nineteenth-century opera in Wagner’s systematic use of leitmotifs, which made the orchestra a powerful force in plot development. Broadway composers occasionally used such unifying devices in their scores in the first half of the twentieth century. Geoffrey Block, for example, has described Jerome Kern’s use of the perfect fourth to describe the Mississippi River and tie together a number of the songs in Show Boat (1927).27 Reprises of songs at dramatically appropriate moments were common, but greater concern for systematic manipulation of musical motives was a rare feature in Broadway musicals before West Side Story, even in the scores by Rodgers and Hammerstein, writers lauded for their level of integration between music and plot. Jim Lovensheimer, for example, has demonstrated musical association between the music for Emile de Becque and Nellie Forbush in South Pacific, but the association forms little more than an interesting sidelight to the score as a whole, certainly not as prominent as some of the repeated motives in West Side Story.28 Kurt Weill, however, coming from a conservatory-trained background, tended to use leitmotifs in his Broadway works, such as Johnny Johnson (1936) and Lady in the Dark (1941).29

Bernstein’s Broadway scores always included efforts at musico-dramatic unification. Jerome Robbins remembers the composer’s disappointment when ‘Gabey’s Coming’ was cut from On the Town because he had made material from that song prominent in the score, as has been demonstrated by Helen Smith.30 She has also shown the prominence of the perfect fifth and fourth in Wonderful Town in the songs ‘A Little Bit in Love’, ‘A Quiet Girl’, ‘Conversation Piece’, ‘Conquering the City’, and ‘What a Waste’.31 The show also features motivic repetitions at dramatically important moments, such as music from ‘Ohio’ in the introduction to ‘What a Waste’ when Baker sings ‘Why did you ever leave Ohio?’ Smith and others have made similar points about Trouble in Tahiti and Candide. Bernstein tended to make comparable efforts in his concert music; indeed, Jack Gottlieb, in the first extended study of Bernstein’s musical style, stated: ‘ … it can be said that he actually composes with intervals as his main source materials’.32 Given these factors, it is strange that Bernstein once stated, concerning his apparently careful efforts to unify the score of West Side Story, ‘I didn’t do all this on purpose.’33

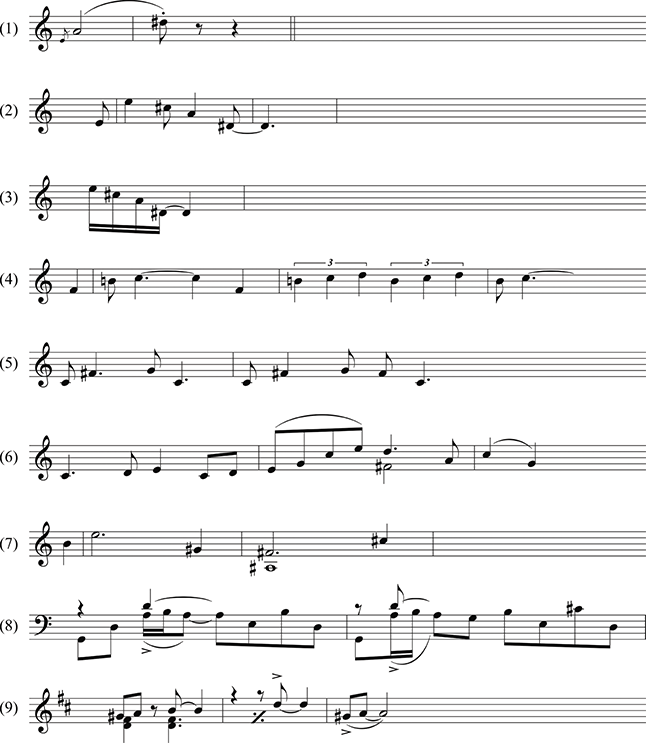

Is this possible? Simeone states: ‘ … this apparent motivic or intervallic consistency [in West Side Story] was never a planned decision on Bernstein’s part and it seems simply to have evolved as one of the work’s defining musical characteristics’.34 The author cites several pieces of evidence: the ‘haphazard way’ that Broadway scores tend to be assembled, a reminiscence from Irwin Kostal about how Bernstein discovered the repeated intervals and motives during a rehearsal break, Ramin’s confirmation of this anecdote, and Stephen Sondheim’s statement that he pointed out to the composer the many tritones he used in the songs.35 These conversations all came after the vast majority of the score had been written. In what Simeone describes as a later document,36 Bernstein jotted down nine leitmotifs from West Side Story (Library of Congress 1079/19; see Example 7.1), perhaps proof for himself of these unifying elements. (Of the nine motives Bernstein provides, some are repeated in the score more than others, as will be shown below.) Simeone might be correct that Bernstein did not plan the recurring motives in the score, but it is tempting to suggest that the composer at some earlier point knew what he was doing. As noted above, this is how the man worked. All of his musicals were written in the same piecemeal way with his collaborators: songs and dances composed, revised, sometimes replaced, and then perhaps re-inserted elsewhere in the score. However, each of the shows demonstrates some sense of musico-dramatic unity. It would not be surprising if Bernstein at some point realized that he was using the tritone prominently in West Side Story, inspiring him to continue. Maybe he was surprised to note the extent of his motivic unification when speaking to Kostal and Ramin at that rehearsal, but would a musician like Bernstein have missed the prominence of the tritone in the openings of both ‘Maria’ and ‘Cool’? Geoffrey Block simply ignores Bernstein’s suggestion that he didn’t intend the score’s sense of unity and notes that the first songs that Bernstein drafted were ‘Maria’ and ‘Somewhere’, both featuring prominent motives in the score.37

Example 7.1 Page of leitmotifs for West Side Story that Bernstein wrote at some point, including: (1) the ‘shofar call’ that sounds often in ‘Prologue’ and ‘The Rumble’ and sometimes opens the show; (2) first melodic motive in the ‘Prologue’, which also appears in B section of the ‘Jet Song’; (3) rhythmic diminution of (2) heard in ‘Prologue’ and ‘The Rumble’; (4) opening of ‘Maria’ with tritone (‘Maria’ motive) as the first interval; (5) opening of ‘Cool’, also with tritone as first interval; (6) opening of verse of ‘Tonight’ from the ‘Balcony Scene’; (7) opening of chorus of ‘Tonight’; (8) bass ostinato from ‘Cha-Cha’; and (9) opening ostinato from ‘Something’s Coming’.

The tritone is ubiquitous, appearing in the opening phrases of ‘Maria’, ‘Blues’, ‘Cha-Cha’, ‘Cool’, ‘Something’s Coming’, and in the motive that Jack Gottlieb compares to a shofar call, the rising perfect fourth followed by the tritone heard often in the ‘Prologue’, ‘The Rumble’, and elsewhere. (This motive at one point carried the text ‘This turf is ours!’) The tritone makes many other appearances, from the clearly significant such as when F♯ sounds against the C major chord at the show’s end, to tiny moments such as when one hears a tritone between the voice and bass line in the vamps that open each verse of ‘Gee, Officer Krupke’. The tritone seems to be related to gang violence and the volcanic love that Tony and Maria share. The perfect fourth, besides opening the ‘shofar call’, also appears prominently in the opening of ‘Something’s Coming’, ‘Tonight’ – both the ‘Balcony Scene’ (see Example 7.2) and ‘Tonight’ (Quintet) – ‘America’, and the ‘Taunting Scene’.38 Another interval that plays a significant role is the evocative minor seventh that opens ‘Somewhere’ (see Example 7.3), which also helps close the ‘Balcony Scene’ (foreshadowing the ‘Ballet Sequence’), and ‘Somewhere’ recurs in the final scene. The ascending minor seventh is also heard in the ‘Cool’ fugue subject and on the words ‘I love him’ in ‘I Have a Love’. Another recurring element is the short–long rhythmic pattern that sets the title word in ‘Somewhere’. Short–long rhythms, with the first note of various lengths, pervade the ‘Ballet Sequence’ (see Example 7.4) and elsewhere, for example often heard on the word ‘pretty’ in ‘I Feel Pretty’. Joseph P. Swain notes that hemiola effects recur in the score, including in the ‘Prologue’, ‘Jet Song’, ‘Something’s Coming’, ‘America’, and the ‘Taunting Music’.39

Melodic and rhythmic motives are not the only elements that help unify Bernstein’s score. As is usually the case in his works, West Side Story is an eclectic mixture of styles, with influences from various types of jazz and Latin music being especially significant, both prominent in American urban life in the late 1950s. Katherine Baber has written persuasively about the sounds of modern jazz in the show, noting that Bernstein’s blend of bop and cool jazz would have been heard as what some called ‘crime jazz’ because of their associations with film noir soundtracks, such as Elmer Bernstein’s score for The Sweet Smell of Success (1957) and Henry Mancini’s A Touch of Evil (1958).40 Jazz helps establish the affect for gang violence and would have sounded strikingly different from typical Broadway fare. One hears influence from bop in the ‘Prologue’, ‘Jet Song’, louder sections of ‘Cool’, and ‘The Rumble’, and much of the remainder of ‘Cool’ is a musical pun on the style. It was in keeping with the tendency of musicians in the United States that Bernstein made few distinctions between various types of ‘Latin music’, applying an Afro-Cuban rumba rhythm in ‘Maria’, a Puerto Rican tempo di seis and an allegedly Mexican huapango in ‘America’, the Cuban mambo and cha-cha in ‘Dance at the Gym’, and what could be described as an Aragonese jota in ‘I Feel Pretty’. Elizabeth A. Wells provides a varied look at Hispanic elements in West Side Story, including the music, in her West Side Story: Cultural Perspectives on an American Musical.41

Individual Numbers

Consideration of individual songs and numbers will include a summary of what preceded that musical placement in the show and an overview of distinctive musical and lyrical qualities. Nigel Simeone in his Leonard Bernstein: West Side Story provides the most coverage in one volume of how the show developed in terms of numbers that were removed and changed.42 Numbers cut from the show, such as ‘Mix!’ and ‘Like Everybody Else’, will not be considered unless they were replaced by other songs. In addition to the musical examples provided in this chapter, the reader will be directed to tracks and time indices on the 1957 and 2009 original cast recordings (OCR57 and OCR09) or Bernstein’s 1984 studio recording (SR).43

‘Prologue’

The opening scene was finalized late in the show’s development. At one point, it was to occur in the Jets’ hideout. The violent songs ‘Mix!’ and ‘This Turf Is Ours!’ were intended for later in the scene.44 The music now heard in the ‘Prologue’ and ‘Jet Song’ appears in other guises in manuscripts.45 There was indecision as to whether or not the show should open with the ‘shofar-call’, as does OCR57 (tr. 1); it does not appear in the published piano/vocal or orchestral scores.46 The motive pervades the ‘Prologue’, such as the strong unison statement at 1′55″. The number’s affect is edgy, building to chaos at 3′27″ when the gangs fight before the police arrive. The ‘Prologue’ includes the following distinctive ideas or moments: a preponderance of major/minor triads; ties between the eighth notes and downbeats in 6/8, disguising the meter (e.g., 0′07″); frequent eighth-note duplets and ties to further disrupt the beat; the iconic finger snaps (0′14″); a wide-ranging theme (see Example 7.5) describing the Jets heard first in the alto saxophone (0′17″) that includes blues thirds (C♯/C-natural) and sets the text ‘You’re never alone … ’ in the ‘Jet Song’; menacing sounds from pitched drums (e.g., 0′47″); a move to 2/4 (2′03″) with numerous ‘shofar calls’ as the gang battle starts; a jazz walking bass line (2′13″) and thickening texture as the violence increases; an exciting, descending motive that ends in a tritone in trumpets and woodwinds (2′36″); wild, imitative material in the brass (2′45″); re-introduction of the walking bass with a triadic motive in the mallet percussion (2′56″); and unpredictable rhythms and staccato notes (3′14″) with thickening texture leading to long, accented notes with flutter-tonguing as Bernardo pierces Arab’s ear (3′25″), preceding a frenzied recapitulation of earlier material as the police enter.

‘Jet Song’

Music for this song existed in earlier versions of the first scene.47 On OCR57, it is a continuation of the ‘Prologue’, with which it shares thematic material, but the song follows dialogue in the show. ‘Jet Song’ is an AA′BA tune, first sung by Riff; the A′ bears considerable variety. The vocal line in the A sections is in 3/4, but Bernstein’s bass line is in 6/8 and the remainder of the accompaniment is syncopated (see Example 7.6). The B melody is the alto saxophone line heard early in the ‘Prologue’ (tr. 1, 0′17″) and in this song’s introduction. Measures 100–116 in the piano/vocal score, where the Jets sing about the dance that night, is not on OCR57 but heard on the SR (1/tr. 2, 1′29″ff). (This section later sounds in the ‘Blues’ from the ‘Dance at the Gym’, as will be stated below.) After Riff leaves, the remainder of the gang sings the song and repeats the final BA, but with a different affect. Sondheim’s lyrics to this point mostly declare how great it is to be a Jet, but here they become more confrontational, and Bernstein’s music follows suit. The final B section (OCR57, tr. 1, 5′27″ff) is in 6/8 with the accompaniment mostly in two, featuring dissonant chords (major/minor triads with added minor and major sixths); the last A section (5′36″ff) changes to 2/4 with the walking bass from the ‘Prologue’ (see Example 7.7) and the vocal rhythms changed from quarter notes to a tresillo (3+3+2).

Example 7.6 ‘Jet Song’, mm. 28–35, with melody in triple meter against syncopations in the right hand and bass line in 6/8

‘Something’s Coming’

This was the last song written for the show, designed to make Tony less of a ‘euphoric dreamer’.48 Sondheim suggested a song in a propulsive 2/4 like ‘The Trolley Song’ from Meet Me in St Louis.49 In a letter to his wife, Bernstein admitted that he had complicated the meter. The song includes other rhythmic intricacies, including a hemiola in the 3/4 ostinato (OCR57, tr. 2, 0′00″) and numerous cross-accents in 2/4 sections (e.g., 0′22″). The opening verse is ABAB and the refrain is CDCDECDE with a coda based on A. Sondheim’s use of short questions, references like ‘cannonballing’ and a baseball metaphor, and poetic evocations provide Tony with a variety of feelings not heard from other Jets. As Simeone notes, Bernstein’s setting includes numerous melodic and harmonic tritones and lowered sevenths in the melody, also heard in the ‘Jet Song’.50 The most fetching lowered seventh in ‘Something’s Coming’ is Tony’s last long C-natural (2′16″), producing a minor seventh over the bass that evokes ‘Somewhere’, and a concluding dominant seventh chord, as though the song fails to end.

‘Dance at the Gym’

An early version of this scene took place in a nightclub called the Crystal Cave,51 but apparently the show’s creators then realized that these young people could not have entered such an establishment. Bernstein wrote dances for the nightclub that he abandoned: ‘First Mambo’, ‘Version B (mambo)’, and ‘Huapango’.52 Among sketches for the scene (Library of Congress, Bernstein Collection, Folder 1077/12), one finds most of the music for the ‘Dance at the Gym’, sometimes under other names. For example, the show’s ‘Mambo’ appears as ‘Fast Mambo (Merengue)’ and an ‘Atom Bomb Mambo’ became part of the dance (OCR09, tr. 4, 2′43″ff). The opening ‘Blues’ in ‘Dance at the Gym’ starts as the bridal shop scene concludes, when Maria starts to whirl to a musical hint from ‘Something’s Coming’, followed by undulating triplets in 12/8 based in chromatically adjacent triads (0′00″). The scene changes and a section marked ‘Rocky’ ensues (0′18″), the 12/8 mimicking a swinging 4/4. Bernstein retains the sliding between adjacent triads and places blues notes over a strong bass line, setting the abovenamed segment from ‘Jet Song’ as the Jets dance with their girlfriends. The Sharks enter and Glad Hand, the emcee, proposes a meeting dance for which Bernstein provided a ‘Promenade’ (SR, 1/5) marked ‘Tempo di Paso Doble’, a cheesy moment with four-square rhythms and tinny orchestration. Everyone quickly grabs their usual partners and launches into the ‘Mambo’ (OCR09, 1′36″), a competitive dance between the gangs based in the soundscape of the Sharks. It opens with an explosion of Latin percussion, followed by frenetic music block-scored for the sound of a Latin big band, but with strings (besides bass) functioning alongside the woodwinds. Bernstein introduces the omnipresent tritone in the brass, first in the trombones (2′06″), complemented by the surrounding chromaticism. There are exciting solos for trombone 1 (3′13″ff, joined by horns at 3′20″) and trumpet in D (3′27″). Block-scoring returns with earlier material and the ‘Mambo’ fades after Tony and Maria see each other (over tritones in the orchestra), introducing the ‘Cha-Cha’ (4′08″). Woodwinds, muted trumpets, and strings playing pizzicato and harmonics offer the melody to ‘Maria’, staccato over a Latin accompaniment; Bernstein layers in additional instruments for the repeat of A (4′34″). The B section is fuller with the violins now arco, leading directly into the ‘Meeting Scene’, where the ‘Maria’ motive dominates in strings, vibraphone, celesta, and high woodwinds in the underscoring (see Example 7.8). The scene ends with a return of the ‘Promenade’, now scored more fully, and a ‘Jump’ (SR, 1/9) scored for a small combo.

‘Maria’

Bernstein wrote a version of this song before Sondheim joined the project. Tony knows only Maria’s name and glories in its sound and his feelings. As Simeone notes, the song’s opening is one of the few recitatives in the score (OCR57, tr. 5, 0′00).53 On OCR57, Larry Kert is joined by off-stage voices, not the case on OCR09, where the song is a solo throughout. Bernstein avoids the tritone in the recitative, so once the lyrical ‘Moderato con anima’ begins (0′34″), one cannot miss the striking interval that punctuates ‘Maria’. We have heard this motive many times in the ‘Dance at the Gym’, statements that help lead to this satisfying moment. Despite the song’s fame, its charm remains with its winning melody, convincing use of speech rhythms, and the tresillo rhythm from the rumba in the bass (see Example 7.9). As Tony keeps repeating her name (1′24″ff), Bernstein wrote a B-flat′ for two measures, with a simplified ossia part that most singers use. José Carreras realized the high note gloriously on the SR, but otherwise on the recording struggles too much with the English text.

‘Balcony Scene’

An update of Romeo and Juliet requires a balcony scene – here on a fire-escape – but what music to use with it was a matter of debate. An early page with Bernstein’s lyrics indicates that ‘Somewhere’ was intended for the scene,54 and Folder 1079/8 in the LC Bernstein Collection includes music from ‘Somewhere’ with ‘Balcony’ crossed out on the cover. ‘One Hand, One Heart’ also at one point was in the scene, as may be seen in Folder 1078/10, where the title ‘Balcony Scene’ also has been deleted. Bernstein and Sondheim derived this version of ‘Tonight’ (Folder 1079/17, dated 4 July 1957) from the ‘Tonight’ (Quintet).55 The scene follows immediately after ‘Maria’, the music of which continues as underscoring. Shortly after Maria starts singing the verse (OCR57, tr. 5, 0′05″), a beguine rhythm starts (see Example 7.2, eighth note pattern in the second line), which becomes the song’s heartbeat. The verse is lyrical, wide in range, with occasional orchestral doubling of the vocal line. The lovers are in a brief, fully fledged duet by the verse’s end, and kiss passionately as the orchestra prepares the refrain (0′47″), a carefully constructed AA′BA with fetching modulations. After the refrain, the orchestra settles downward from B-flat major to A for their duet (1′54″), sung in octaves, still propelled by the beguine rhythms (2′12″). Maria goes into her family’s apartment for a moment and Bernstein descends one more half-step to A-flat major for Tony’s brief solo; the underscoring for their ensuing dialogue is not on OCR57. It does appear on the SR (1/11, 4′58″); Bernstein references the opening motive of ‘Somewhere’ often in the orchestration. On OCR57, their final, brief duet starts at 3′13″, again sung in octaves. ‘Somewhere’ sounds once again in the orchestra as they hold their final note, ending with the ‘Maria’ motive.

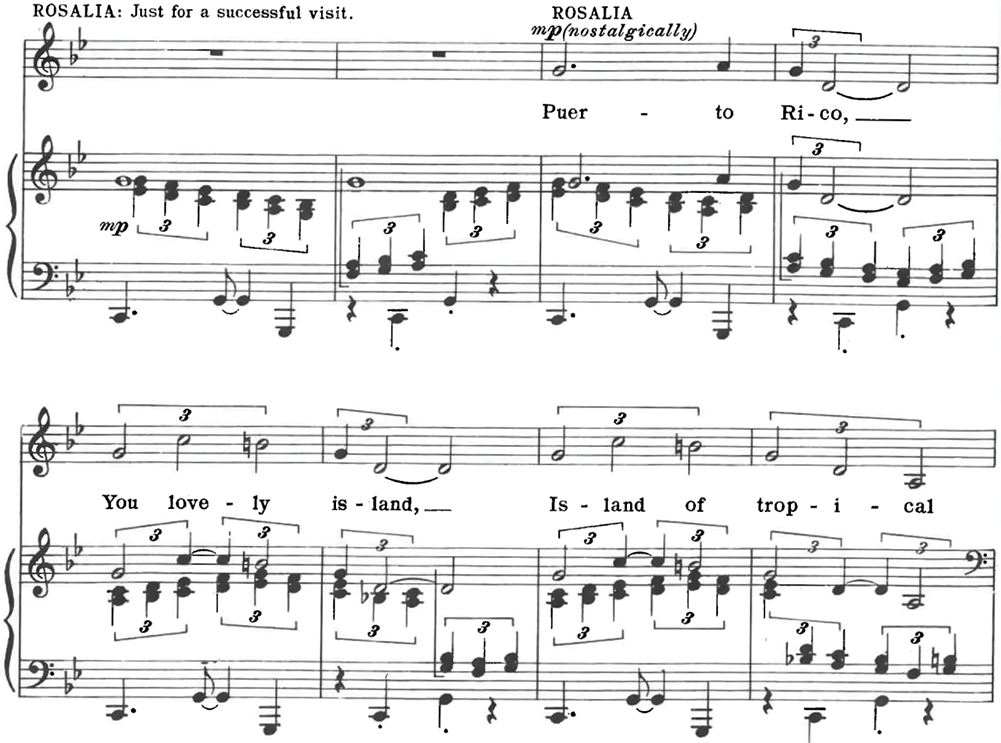

‘America’

Aaron Copland perhaps spurred Bernstein’s interest in Mexican music. The younger musician arranged Copland’s El Salón México in 1941, and the same year wrote his own movement, Conchtown, as a possible ballet; later that music became ‘America’. The opening section, a seis (OCR57, tr. 6, 0′00″), is the score’s only imitation of Puerto Rican music. A seis is an accompanied vocal work with lines of eight syllables (‘America’ here includes some nine-syllable lines),56 but Bernstein omitted the genre’s usual instrumental interludes. The seis leads directly into the huapango (1′14″), a fast, Mexican dance that tends to mix 3/4, 6/8, and 2/4. Bernstein provides a similarly complicated mixture with some alla breve rhythms, quarter-note and half-note triplets, and a tresillo in the song’s opening section (see Example 7.10), as Wells notes, but that is in the seis.57 Rosalia fondly remembers her home’s beauty, but Anita mocks her with images of the island’s sickness, storms, poverty, and violence, references that Puerto Ricans have often criticized. The orchestration cleverly supports points made by both women in the seis. In the huapango, instead of combining meters, Bernstein alternates continuously between 3/4 and 6/8. As Simeone has noted, ‘it is not one of the most musically demanding numbers in the show … ’,58 but ‘America’ is mesmerizing and fluid, the key shifting effortlessly between C major and A-flat major as Anita and her friends mock Rosalia and praise life in the continental United States. Sondheim’s lyrics are witty and effective, if at times difficult to understand with the fast music. The orchestration in this number crackles with excitement with well-placed Latin percussion and other delightful moments.

‘Cool’

‘Cool’ is ready proof of the sophistication of Bernstein’s score when compared to typical Broadway fare in the 1950s. Its affect and orchestration are based upon a musical pun related to cool jazz. In contrast to the aggressive sounds of bop, cool jazz included such instruments as vibraphone, flute, French horn, and subtle use of saxophones and muted trumpets. The Jets are nervous about the rumble that night and Riff wants to focus their energy, a spectacular dance opportunity. The song’s melody (OCR57, tr. 7, 0′10″) opens with a tritone, but not on an accented beat as in ‘Maria’. ‘Cool’ is a 32-bar song, ABAB′, for which Sondheim provided an appropriate text with delightful internal rhymes. What follows is a memorable jazz fugue. As Simeone notes, the first four notes of the subject strongly resemble famous passages of Beethoven’s Grosse Fuge.59 The subject sounds in long notes from muted trumpet (with dotted rhythms from the vibraphone) and surprisingly nearly forms a twelve-tone row. The countersubject enters (1′20″), with more swinging dotted rhythms in the vibraphone while the subject in whole notes passes to the trombone. As the exciting fugue progresses, Robbins’s dance moves present excited youths trying to restrain themselves. Their energy bursts forth at 2′51″, when Bernstein turns his pit orchestra into a bop big band. The Jets sing the final AB′ as the number returns to its cool roots.

‘One Hand, One Heart’

Bernstein originally wrote this melody for Candide. Its first placement in West Side Story, as noted above, was in the balcony scene, where Simeone believes it was to follow ‘Somewhere’.60 During rehearsals, the creators moved the tune to the mock wedding in the bridal shop, prompting a new version dated 4 July 1957 (Folder 1078/9). The melody was in dotted half notes; Sondheim prevailed upon Bernstein to break those values into some shorter notes to accommodate additional words. The folder includes a lead sheet with the new lyrics. Here the ‘Cha-Cha’ underscores Tony and Maria imagining meeting each other’s parents, and music later heard with ‘Somewhere’ underscores their vows. ‘One Hand, One Heart’ is a slow waltz, with an elegant melody that revolves around the third degree of the scale. There are blues intervals of a lowered seventh (‘now we start’) just before the climax (OCR57, tr. 8, 1′01″ff) and a lowered third (‘Even death’, 1′13″) prior to the conclusion. The lovers repeat the song’s second half, singing more counterpoint. Not surprisingly, the ‘Maria’ tritone sounds in the accompaniment, such as at the song’s conclusion. (See Example 7.11 for an example.)

‘Tonight’ (Quintet)

Originally intended to be sung by Riff, Bernardo, Tony, Maria, and Anita, by the time the show premiered in New York the gangs sang with their leaders.61 Although it was no longer a true quintet, Bernstein’s operatic model remained clear with five vocal lines heard individually and combined towards the end. The ‘Tonight’ (Quintet) immediately follows ‘One Hand, One Heart’, perhaps the show’s most jarring musical juxtaposition. The number’s level of dissonance, metric complexity, and cross-accents foreshadow the violent music heard in ‘The Rumble’. As the number opens, Bernstein apposes C and E major and a bass ostinato in a clear triple meter against march rhythms in alternating 4/4 and 2/4 measures (see Example 7.12), later with occasional 3/8 bars. The gangs alternate, singing in a low range, their lines sounding in E minor with many lowered sevenths and frequently dissonant with the accompaniment. The vocal parts shift to a pitch center of A with more lowered sevenths and some C-naturals (OCR57, tr. 9, 0′42″), with the orchestra now projecting A and F major. When Anita makes her entrance (1′07″), Bernstein returns to C and E major and the opening accompaniment, but a sexy saxophone entrance greets her as she anticipates a passionate evening with Bernardo. When Tony enters with ‘Tonight’ as heard earlier (1′25″), the composer recalls the beguine rhythms and uses less dissonance. Tony sings the whole chorus followed by an orchestral statement of the opening march material in A and F major. Riff meets Tony (2′23″) singing the gang melody (now in E-flat and G major/minor), reminding Tony to attend the rumble. When Maria enters (2′40″), Bernstein has formed a trio; quickly all five parts come together, an extraordinary moment in the Broadway repertory. A few more modulations occur to accommodate the melody that Tony and Maria sing together (3′05″), with the other three active parts creating an exhilarating, dense texture. Dissonance continues as the accompaniment sounds both D and E-flat chords against the prevailing C major.

‘The Rumble’

The song ‘Mix!’ got moved here after being deleted from the first scene,62 but the gang fight became a ballet. Bernstein logically returned to material from ‘The Prologue’, but it has been stripped of any of the innocence or youthful enthusiasm heard early in the opening number. Tritones, triads with added tones, and striking orchestration abound in ‘The Rumble’. There are many of the ‘shofar calls’ sounding in a variety of textures, including in the dense, opening 50 seconds (OCR57, tr. 10) and in cat-and-mouse imitative material as Riff and Bernardo jockey for position in their knife fight (0′51″ff), a segment that builds to a shattering climax with the same motive when Bernardo kills Riff (1′24″). The remainder of the segment minutely follows the action on stage, demonstrating Bernstein’s close collaboration with Robbins.

‘I Feel Pretty’

‘The Rumble’ closes Act 1. Following an intermission, the ‘Entr’acte, is ‘I Feel Pretty’, the instrumental selection continuing directly into the song. Laurents did not think that the number belonged in the show and Sondheim has expressed distaste for his own work because he places sophisticated English rhymes in the mouth of a Puerto Rican girl whose first language is Spanish.63 As Simeone states, however, audiences love the song and there is a dramatic reason for its presence in the show.64 The audience saw the rumble and its deadly results; Maria has yet to learn about the fight. A young woman, dizzy with her first love, just might play around with her friends before seeing the man that she loves, and those friends might tease her when they believe that her lover is Chino, a Shark. ‘I Feel Pretty’, therefore, helps fill out Maria’s character and provides some humour, which this show needs. For the music, Bernstein seems to have referenced Iberian models (OCR57, tr. 11). In a fast three, ‘I Feel Pretty’ is a waltz but also resembles an Aragonese jota, an identification buoyed by the use of castanets and ornamentation in Maria’s vocal line redolent of flamenco (e.g., the triplet on ‘tonight’ at 0′16″). When her three friends tease her, they suggest that Maria believes herself to be in Spain. Sondheim was right, of course, that a real Maria probably could not conceive these rhymes, but musical theatre audiences often are willing to make dramatic allowances for enjoyable songs.

‘Ballet Sequence’

Given the significance of dance in West Side Story, one almost expects a dream ballet. Manuscript evidence indicates that finding the scene’s form and content was a difficult task for both Bernstein and Robbins, as Simeone details.65 The scene came together quite late, even after orchestrations were well in hand, because there is material in the orchestral manuscript ‘New Intro to Ballet Sequence’ that failed to remain in the scene.66 The segment’s emotional range is notable, as is the number of other themes from the show that Bernstein works into it. The opening ‘Under Dialogue’ (some of it heard on SR) accompanies Tony’s anguished explanation of the rumble to Maria. Marked ‘Allegro agitato’, it is a development of the ‘Maria’ motive over insistent percussion. An ascending half-step dominates the accompaniment as Tony sings (OCR57, tr. 12, 0′00″) that they will flee, joined by Maria as they hope for a place that offers them freedom. As they run (0′20″ff), there is further development of the ‘Maria’ motive and material from the ‘Cha-Cha’. A strong statement of the ‘Somewhere’ motive (0′35″) opens the ‘Transition to Scherzo’ followed by a succession of short–long rhythms – related to both the ‘Maria’ and ‘Somewhere’ motives – leading into the playful ‘Scherzo’ (1′07″ff), where cast members from both sides dreamily dance together. The music is based on similar material. ‘Somewhere’ follows (2′36″), sung by a member of the ensemble. It is a simple, refined melody built from several ideas, proceeding with compelling inevitability because of its regular phrase structures and various sequences. The contrapuntal accompaniment includes satisfying, rising minor sevenths and imitation. The ‘Procession and Nightmare’ (4′47″ff) opens with the ‘Somewhere’ melody against ‘I Have a Love’, a combination that recurs in the ‘Finale’. This is the first time the audience hears any of Maria’s last song. Orchestral material from the ‘Scherzo’ follows (5′42″ff) but played more urgently. Bernstein further transforms it for the nightmare, briefly reprising music from ‘The Rumble’ (6′18″). Tony and Maria conclude the scene (6′42″) singing material from ‘Somewhere’. The three final measures in the orchestra (7′11″ff) are like those that close the show (see Example 7.13), but the two entrances in the bass on second beats of the first two 2/4 bars in the passage are the root of an F major chord rather than a tritone away, which is how the show ends. For a brief moment, the lovers are safe and fulfilled, ending a ballet, during which they are understood to have consummated their relationship.

‘Gee, Officer Krupke’

As reported above, Bernstein wrote this music for Candide; Burton notes that it was for the scene in Venice.67 Creators of West Side Story added this song for the Jets during rehearsals. Laurents thought the second act needed the relief, but Sondheim suggested that the positions of ‘Cool’ and ‘Krupke’ should be reversed, which is what happened in the 1961 film.68 Bernstein marked the number ‘Fast, vaudeville style’, setting up the song’s mocking tone and slapstick effects in the orchestration. Sondheim’s lyrics provide useful social commentary on how society deals with juvenile delinquents.

‘A Boy Like That/I Have a Love’

The show’s two most operatic numbers are the ‘Tonight’ (Quintet) and this double song, which went through a long process of development, as Simeone describes.69 Anita comes to Maria for comfort and discovers that she has been with Bernardo’s killer. She tears into Maria, singing low in her range for much of a violent song filled with dissonance. As noted above, the orchestral accompaniment is redolent of ‘The Rumble’. The first two measures in the orchestra function as a ritornello that sounds between each of Anita’s phrases in the AABA form, but the instrumental interjection is only one measure before the B section, as if Anita is so enraged that she cannot wait to sing (OCR57, tr. 14, 0′31″). Maria interrupts her (1′01″ff), quickly rising to an A-flat″, but then defending herself, singing Anita’s music in a lower range. As Anita starts to repeat her song in counterpoint (1′20″), Maria moves to the opening motive of ‘I Have a Love’, repeated numerous times as she parries Anita’s thrusts. Maria ends the duet soon after she reaches a B-flat″ (1′48″) and then tells her friend, ‘You should know better!’ ‘I Have a Love’ (OCR57, tr. 15) ensues, opening in an innocent G major and moving quickly from conjunct motion to cover a larger range with skips (see Example 7.14) and effective modulations like those heard in ‘Tonight’. Once Maria holds a G′ on ‘life’ (1′24″), now in E minor, Anita has been won over. Following an orchestral climax, they sing a contrapuntal duet (1′38″ff), signalling Anita’s willingness to try to help Tony and Maria.

‘Taunting Scene’

Anita goes to the drugstore to give Tony a message, but the Jets detain her, taunt her, and have begun to assault her when Doc breaks it up. This recorded music sounds from the jukebox and is based on music from Anita’s soundscape: the ‘Mambo’ and material derived from ‘America’, the latter deconstructed and combined with unfamiliar elements.

‘Finale’

Bernstein wanted music in place of Maria’s final speech when she holds the gun. He stated: ‘I don’t know how many times I tried to musicalize that. It cries out for music.’70 Despite his statement, however, no such sketches survive and the most dramatic moment in the show is spoken without underscoring. Earlier in the scene, Maria sings some of ‘Somewhere’, briefly joined by Tony before he dies. Material from ‘Somewhere’ accompanies Maria bidding farewell to him. She then excoriates the gangs as she threatens everyone with the gun, but finally she collapses. To conclude the scene during the procession as the gangs carry off Tony’s body, Bernstein used music from the end of the ‘Ballet Sequence’, a contrapuntal treatment of ‘I Have a Love’ and material from ‘Somewhere’. As noted above, the show’s last three measures are based on how the ‘Ballet Sequence’ ends, but Bernstein now combines C major (with the rising major second from ‘Somewhere’ resolving from D to E) joined by a jarring F♯ in the bass, stated only the first two times in the original show (see Example 7.15). The final measure includes just the C major triad with the rising major second ending on the third of the chord. Bernstein added the tritone to the chord root C′ with the F♯ in the bass to the last measure in the Symphonic Dances from West Side Story, in his 1984 studio recording, and in the 1994 orchestral score. Most of the written finale appears on the OCR57 (tr. 16) and on the SR.

Conclusion

Created for a show that explored new ground on Broadway, the score for West Side Story was also unusual for its time with its very wide range of influences and the consistently high level of inspiration heard in the music. It includes unforgettable melodies and lyrics that strongly add to the definition of characters and dramatic situations. The dance music, written by Bernstein counter to the usual Broadway practice of hiring a dance arranger, is more original than the arrangements of songs heard in most contemporary shows. Numbers are unified by motives that often recur elsewhere in the score, making the music a major force in West Side Story’s sense of organic wholeness. The orchestrations translate the music into three dominant soundscapes that help tie together different scenes involving similar characters and situations. A fine monument to the music’s effectiveness is the orchestral work Symphonic Dances from West Side Story that Bernstein worked on with Ramin and Kostal in 1961. Numbers do not appear in the suite in show order, allowing one to hear the music without lyrics and out of dramatic context, where the score’s power remains undiminished, a tribute to the striking creativity that Bernstein brought to his most famous work.