If Richard Wagner is one of the most written-about men in history, this is due in no small part to the extraordinary amount of debate and controversy inspired by Der Ring des Nibelungen. Friend and foe agree that the tetralogy occupies a unique position in the development of art and that its influence is (or should be) felt in all areas of society, culture, and politics. It is these claims to the Ring’s wider significance that form the backbone of this chapter. Its scope does not allow for a fully fledged reception study of Wagner criticism, nor will any of the many artistic responses – from Henri Fantin-Latour’s drawings to J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings – be considered. Nor is this a history of Ring research, although some seminal works by professional music critics and musicologists will feature in the second half of this chapter. Rather, it will chart some milestones of the debates surrounding Wagner’s Ring, including well-known contributions by Nietzsche, Shaw, and Adorno but also by less well-known writers, and place them into their wider historical and social context.

A quick glance at the wealth of literature shows that it falls basically into two camps: writings that insert Wagner’s Ring into an ideological system of the author’s choice, and writings that develop an interpretation of the wider world from the Ring outward. The sheer size and heterogeneity of the Ring makes it difficult to integrate it seamlessly into any complex argument; thus its “meaning” frequently was reduced to a manageable selection of intellectual or artistic concepts, or discussions highlighted only those features that went well with the Weltanschauung in question. On the other hand, the Ring was and is a particularly fruitful playing field for debate, with its focus on law and governance, freedom and servitude, loyalty and disobedience, greedy egotism and selfless love. From the start, most commentators were aware that the Ring owed its initial inspiration to the composer’s involvement in the 1848–9 Revolutions. Wagner himself raised the stakes with writings such as Das Kunstwerk der Zukunft (Artwork of the Future, 1849) and Eine Mittheilung an meine Freunde (A Communication to My Friends, 1851), which promised a complete shake-up of all things artistic and political through his latest operatic venture. He could not have foreseen, however, the wide range of interpretations that the completed Ring would inspire.

From the Publication of the Libretto to Bayreuth

Public responses to the Ring started considerably before its first complete performance in Bayreuth in 1876, at a time when only the music of Das Rheingold, Die Walküre, and half of Siegfried had been completed. Heinrich Porges, coeditor of the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (NZfM) and later the chronicler of the 1876 rehearsals in Bayreuth, was among the first to promise a full-scale interpretation of the Ring based on the libretto published in 1863. Although his series of articles did not venture further than Rheingold, it introduced several themes that remained staples of the discourse for decades to come: the claim that the Ring attempted to “recreate the totality of the hustle and bustle of the world in a unified artwork”;Footnote 1 its relevance particularly for the Germans by reviving their “ancient history”; its combination of Greek clarity with Germanic infiniteness;Footnote 2 its perfect embodiment of nature in the figure of Siegfried, the “ur-image of the human being”;Footnote 3 the expressivity and realism of its music and its developmental-symphonic character reminiscent of Beethoven.Footnote 4 Much of Porges’ introduction, however, is a plot summary, and this focus continues in the critical responses to the first cyclic performances in Bayreuth in 1876. Apparently, the mythological storyline, which departed significantly from the well-known Nibelungenlied, needed substantial explanation. By contrast, few writers saw the Ring’s potential significance beyond immediate artistic or musical concerns. The Protestant Church in Germany strongly voiced its discomfort with the all-encompassing pretensions of the artwork of the future, the preachings of the “new musical Messiah” and the Schwärmerei (swooning enthusiasm) among his followers.Footnote 5 A journalist for the Neue Evangelische Kirchenzeitung also rejected the claim that the music dramas or their Bayreuth realization constituted a national treasure, an idea that already had become standard among Wagnerians. However, even those who emphasized Bayreuth’s significance for a new national – German – art usually stopped short of drawing explicit political parallels. One exception is an anonymous article in the Deutsche Presse of Vienna, which traces the inspiration for the festival to the upsurge of national confidence in the wake of the Franco-Prussian War, claiming that the German people themselves had now become the patron of art.Footnote 6 The author’s stance must be seen against his Austrian background: After the hopes for a Greater German Empire had been laid to rest for the present, many Austro-Germans upheld all the more forcefully the inseparable bond of Germany and Austria in the sphere of arts and ideas.

Friedrich Nietzsche likewise saw the Franco-Prussian War as a decisive step towards the realization of the Bayreuth project. He published “Richard Wagner in Bayreuth” as the fourth of his Unzeitgemäße Betrachtungen (Untimely Meditations) in 1876 and sent the essay to Wagner in July 1876 as “a kind of Bayreuth festival sermon.”Footnote 7 In many ways, it serves as an echo chamber of Wagner’s own writings about the destiny of the music drama, namely to bring about profound change in all areas of society. In line with the title of the essay collection, Nietzsche stresses that the Wagner phenomenon is not yet “timely” (zeitgemäß); the realization of the Bayreuth Festival anticipates a future world which truly needs art and derives authentic satisfaction from it.Footnote 8 Among the present generation, Wagner’s works will steel the tragic spirit for future fights against the traditional order of power and law, customs and contracts.Footnote 9 Exasperatedly, he exclaims in the final section, “And now ask yourselves, you generations of human beings living today! Was this written for you? Do you have the courage to point your hand at the stars of this entire firmament of beauty and goodness and say: it is our life that Wagner placed under these stars?”Footnote 10

It is ironic that the writer of the impassioned “festival sermon” had to leave Bayreuth during the rehearsals, as he could not bear the heat or the admiring crowds. Twelve years later, he had shaken himself free from his Wagner infatuation and attacked him in Der Fall Wagner (The Case of Wagner, 1888) and Nietzsche contra Wagner (1889). In his acerbic parody of “redemption,” he declares that the composer – in the guise of the “typical revolutionary” Siegfried – sought his own redemption in the Ring through the destruction of the old gods and the emancipation of woman.Footnote 11 Wagner foundered on the reef of Schopenhauerian philosophy, turning the Ring from a socialist utopia into a dramatization of Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung, and Wagner into the artist of decadence. While “Richard Wagner in Bayreuth” stressed the noncontemporaneity of his works, Der Fall Wagner declared the opposite: Wagner’s oeuvre encapsulates everything that is wrong with modern art and society; it is artificial, brutal, mock-innocent, lying; a pick-me-up for enfeebled youths and a dangerous stimulant for hysterical women.

Degeneration and Regeneration

Nietzsche’s voice was by no means alone in a swelling chorus decrying contemporary culture. “Conservative revolutionaries” like Paul de Lagarde, Julius Langbehn, or Arthur Moeller van den Bruck vociferously attacked liberalism, capitalism, materialism, parliamentarianism, and urban lifestyles and “propounded all manner of reforms, ruthless and idealistic, nationalistic and utopian,”Footnote 12 holding out the promise of a redemption or rebirth in the völkisch spirit. The success of these “politics of cultural despair,” using Fritz Stern’s memorable term, built on a long-standing tradition of German idealistic yearning, an emphasis on culture and the cultivation of Innerlichkeit (inwardness), and a deeply-ingrained habit to regard culture as equal with religion, which brought a prophesying and proselytizing tone into the debate.Footnote 13 The place of art in society was important in these writings, not least because Wagner himself had made far-reaching claims about the redemptive mission of his music dramas and joined the antimodern discourse in his late “regeneration writings.” However, opinions were divided whether he was the illness of or the cure for modern life. While Paul de Lagarde, for example, was courted by Bayreuth after Wagner’s death, the bestselling writer of Deutsche Schriften (German Writings, 1878) was “bored to extinction” by a performance of Siegfried and told Wagnerians so with great relish.Footnote 14 Leo Tolstoy was similarly traumatized by attending the same opera in Moscow. In his essay What Is Art? (1897) he pillories plot and performance in excruciating detail and reiterates, by then, well-worn criticisms of the music. Since his essay deals with the question of art’s role in society, his main concern is the impact of Wagner’s works on an already degenerate urban audience. They will

affect the spectator by hypnotizing him, as a man who listens for several hours to the ravings of a madman uttered with great oratorical skill will also become hypnotized … This can be achieved in a still quicker way by drinking wine or smoking opium … Try sitting in the dark for four days in the company of not quite normal people, subjecting your brain to the strongest influence of sound calculated to excite the brain by strongly affecting the nerves of hearing, and you are certain to arrive at an abnormal state and come to admire the absurdity.Footnote 15

Julius Langbehn, another cultural pessimist, took particular offense at the “erotic madness” in Tristan und Isolde, which he characterized as non-German, and saw a similarly exaggerated “sensual character” in the Nordic mythology, in contrast to the “silent passion” of the ur-German Nibelungenlied.Footnote 16 Even Wagner’s anti-Semitism was no recommendation to Langbehn, one of the figureheads of this movement, since Wagner had applied Meyerbeer’s technique to national stories and thus “out-meyerbeered Meyerbeer.”

The medicalization of Wagner’s operas reached its high point in Max Nordau’s widely read pathology of fin de siècle cultural Entartung (Degeneration, 1892).Footnote 17 Building on the work of Italian psychiatrist Cesare Lombroso, who had linked genius and mental disorder, Nordau offered a complementary study of arts and letters,Footnote 18 encompassing phenomena as diverse as the Pre-Raphaelites, Symbolism, and the “cult of Richard Wagner” under the heading “mysticism.” He sees Wagner as the victim of two pathological urges: an anarchist bitterness, which manifests itself mainly in the writings (not in the Ring), and an exuberant sexual drive: “All his life, Wagner has been an amorist [Erotiker] (in the pathological sense of the word) and his imagination entirely circles on woman.”Footnote 19 The Ring provides a rich hunting ground for corroborating evidence. After citing Hanslick’s verdict of the “animal sensuality” in Rheingold and the repugnant lustful groaning in Siegfried, Nordau offers a close reading of the stage directions in Die Walküre and concludes that Siegfried, Götterdämmerung, and Tristan und Isolde faithfully replay the main content of Die Walküre: “It is the ever same dramatic embodiment of the same obsessive idea, the terror of love.”Footnote 20 At the same time, Wagner’s bodily urges struggle with the self-denying ideals of Schopenhauerian philosophy, necessitating the death of the sinful character. This eroticism was not even original since Nordau brands Wagner “the last fungus on the dung-heap of romanticism.”Footnote 21 He sees Wagner’s intermingling of the arts not as a step towards the future but as an atavistic regression towards an earlier, less developed stage. Nordau’s criticism of the music, however, remains conventional; he rejects the “endless melody” as a string of recitatives, and the use of leitmotifs as a violation of the nonrepresentational nature of music. From these criticisms, Nordau moves back to the intellectual and cultural climate which made degenerate art possible: The eager reception of Wagner’s works can only be explained with the rise of hysteria in Germany since the 1870s. Especially those already affected – notably women – were an easy prey for the voluptuous eroticism, dazzling imagery, and hypnotic quality of the music. Furthermore, Wagner’s success relies on pandering to contemporary obsessions of the Germans, such as anti-Semitism, chauvinism, and vegetarianism. Nordau thus classifies these regeneration movements, which were endorsed by many of the “conservative revolutionaries,” as dangerous aberrations that found their artistic complement in Wagner.

It may seem ironic that Wagner’s attempts to revive folklore and national mythology could be interpreted as a sign of decay and degeneration, for instance in Oswald Spengler’s Der Untergang des Abendlandes (Decline of the West, 1918–22), which outlines a historiographical panorama of rising and falling cultures, with Western civilization the latest to enter a downward trajectory. Spengler draws parallels between Wagner and Baudelaire, who both appeal to the “cosmopolitan man of the brain, not the rural or generally natural man,”Footnote 22 aligns their art with contemporary concepts such as Darwinism and Socialism and declares: “Everything Nietzsche has said about Wagner equally applies to Manet. Seemingly a return to the elemental …, their art in fact yields to the barbarism of the big cities … . An artificial art is unable to develop organically; it marks the end.”Footnote 23 Although Spengler lacks the moral panic that characterizes much of fin de siècle cultural criticism, he clearly sees Wagner’s art as the writing on the wall.

The opposite camp considered Wagner one of its figureheads in the fight for regeneration and national renewal but was likewise steeped in conservative cultural pessimism, possibly with even more pronounced racist and supremacist overtones. The journal Bayreuther Blätter, founded by Wagner’s acolyte Hans von Wolzogen in 1878 to give Wagner’s late writings a forum and to act as the “official” Bayreuth mouthpiece, sought, in particular, to integrate the dramas into a völkisch worldview.Footnote 24 At first the Bayreuther Blätter focused on Parsifal and published only literary-historical explorations of the Ring mythology, with the exception of an early contribution by Nietzsche’s physician Otto Eiser, who suggested that the Nordic-Germanic Ring mythology was injected with a contemporary spirit and thus evolved towards the basic idea of Christianity.Footnote 25 The most comprehensive exegesis of the Ring appeared in several installments between 1907 and 1915: The Austrian independent scholar Felix Gross interpreted the tetralogy as a pagan cosmology in preparation for the Christian world in Parsifal, where gods and humans progress through ever-renewing cycles of innocence, fall-from-grace, curse, and revenge.Footnote 26 Rheingold in particular is seen through the racist lens as a fight between Aryan and non-Aryan races, which the former are doomed to lose precisely because of their exalted ideals. Gross was not the only one to employ the modish term “Aryan,” which so conveniently conflated mythology and up-to-date science. In 1911 the esteemed Viennese Indologist Leopold von Schroeder published a treatise where he explains Wagnerian drama as the final destination of several thousand years of Aryan culture, from Indian cult and Greek theater onwards.Footnote 27 Schroeder reads the Siegfried story as a modern variant of an archaic solar myth, a theory that by 1911 had a venerable ancestry, not least in Wagner’s own treatise Die Wibelungen. In contrast to many others dabbling in Aryan ideas, however, Schroeder had a solid academic background in Indian literature and Baltic folklore, and while the introduction in particular celebrates Wagner’s creation of the German music drama as rebirth of ur-Aryan myths, his arguments steer clear of the derogatory racism so common in the early twentieth century.

Whether these writers saw in the Ring drama the crowning achievement of German – or even human – culture or just the most deplorable aberration of modern civilization, they usually agreed that their praise or criticism was not political but metapolitical. The Ring’s potential for critiquing contemporary political and social conditions was suppressed through a strict separation of the lowly realm of pragmatic, materialistic politics and an idealistic sphere of timeless, transcendent values and artistic endeavor.Footnote 28 Even Wagner’s son-in-law, Houston Stewart Chamberlain, who exerted a decisive influence on twentieth-century politics, kept Wagner out of his ideological texts. The composer is not even mentioned in the seminal Die Grundlagen des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts (Foundations of the Nineteenth Century, 1899), while Das Drama Richard Wagners (1892) proposes a purely interiorized reading of the music dramas including the Ring, which he characterizes as the “tragedy of Wotan.”Footnote 29

This apolitical posturing of intellectual opinion leaders, which dogged German intellectual life well into the twentieth century, found its best-known expression in Thomas Mann’s Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen (Reflections of a Non-Political Man, 1918), where he argues that his rejection of democracy and cosmopolitanism – all alien to the German spirit – does not constitute a political but a metapolitical statement.Footnote 30 His early experiences of Wagner’s music played an important role in the self-fashioning of the German bourgeois thinker par excellence, including a story of how alienated – and German – he felt while listening to an open-air performance of Siegfried’s Funeral March in Rome, surrounded by a crowd of unruly Italians. The lecture “Leiden und Größe Richard Wagners” (Richard Wagner’s Suffering and Greatness), which he gave at an event of the Munich Goethe Society on February 10, 1933, responded to the changed political climate with careful analysis and guarded observations. Mann’s main concerns are Wagner’s character and personality as an artist, and at first he contains Wagner’s political activism within the nineteenth-century bourgeois mindset: “I won’t insist that he was a revolutionary of 1848, a middle-class fighter and thus a political citizen; because he was it in his particular way, as an artist and in the interest of his revolutionary art, for which he expected non-material advantages, improved reception conditions from an overturning of the existing order.”Footnote 31 However, when Mann moves on to nationalism and Wagner’s Germanness, it becomes apparent that his insistence on the unpolitical nature of the composer – whose nationalism was either alien to official state politics in the 1840s, or merely pragmatic in Bismarck’s new Empire – is a warning against the simplistic appropriation of the artist by the National Socialist regime. In Mann’s view, Wagner’s Germanness is “modern, fragmented and deconstructed, decorative, analytic, intellectual,” at the same time offering “the most sensational self-expression and self-criticism of the German character” – in short, cosmopolitan.Footnote 32 The effect of the lecture was immediate: Forty-eight mainly Munich-based artists and intellectuals (most of whom had not heard the lecture or read the article in Die Neue Rundschau) accused Mann in an open letter of character assassination, which the writer took as a signal not to return from a holiday in Switzerland.

While “Leiden und Größe Richard Wagners” has little to say specifically about the Ring, in 1937 Mann returned to the tetralogy in a public lecture delivered on occasion of a performance in Zurich. Here the metapolitical reading of Wagner’s music dramas reasserts itself. In the first half, Mann outlines in some detail Wagner’s revolutionary involvement and even calls him a “Kultur-Bolshevist,” who wrote the Ring “essentially as an attack on the bourgeois civilization and culture that had reigned supreme since the Renaissance – [with] its blend of primitivism and futurity … aimed at a non-existent world of classless populism.”Footnote 33 His initial comparison of the Ring with the second part of Goethe’s Faust, however, signals that Wagner’s work was no mere political parable but true art and therefore “concerned solely with the primeval poetry of the psyche, with the simplest of beginnings, the pre-conventional and the pre-social: and these things alone seem to him to be fit material for art.”Footnote 34 While non-German artists, such as Dickens, Thackeray, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Balzac, or Zola focused their efforts at monumentality on the social novel, “the form that this greatness took in Germany, knows nothing of the social dimension and desires to know nothing of it: for society is not musical, or indeed accessible to art at all.”Footnote 35 Contemporary events notwithstanding, Mann placidly concludes that the “German spirit is essentially uninterested in the social and the political”Footnote 36 and that the Ring’s ending projects “the same message that speaks to us in the words at the end of Germany’s other universal poem of life [i.e. Faust II] … The Eternal-Feminine / Draws us ever on.”Footnote 37 Wagner’s art is divorced from the political realities of the day not because it is “just art” but because it is “true art.”

Political Readings

Due to the dominance of these fin de siècle “idealists,” political readings of the Ring were rare in German-speaking Wagner literature. An interesting exception is Moritz Wirth’s treatise Bismarck, Wagner, Rodbertus, drei deutsche Meister (Three German Masters, 1883). He sets out rather conventionally by celebrating Bismarck and Wagner as the creators of the German Empire and German music drama respectively. However, their legacy is still awaiting completion in the sphere of social reform, as envisaged by the economist Karl Rodbertus. Rodbertus was interested in the welfare of the working classes, and, while stopping short of communist demands like the nationalization of property and capital, he advocated state intervention to guarantee minimum wages and thus a more equal access to property, culture, and education.Footnote 38 The influence of this idea can be seen in Wirth’s appraisal of the Ring, where he asks: “Alberich’s cursed ring, which travels from hand to hand, what should it signify but the reign of capitalism, which is just as detrimental for us inhabitants of the real world, as the ring is for the gods and heroes of the drama?”Footnote 39 In Wirth’s view, Wagner did not follow these ideas to their logical conclusion, as he portrays greed for money and lust for power as individual shortcomings, which can be healed with compassion and self-denial as expounded in Parsifal. Wirth, in contrast, maintains that social and economic ills need a social solution, as outlined in the economic theories of Rodbertus: The improvement of the material conditions would automatically lead to an improvement in morality and common happiness.Footnote 40 Thus the most fitting model for the German people is not a Buddhist outcast along the lines of Die Sieger but a dynamic character such as Wieland the Smith.

The tension between “idealistic,” apolitical readings of Wagner’s music dramas on the one hand and more concrete political applications on the other, is played out in several European countries around the turn of the century. Discussions about Wagner’s relevance for contemporary society were further complicated by the necessity to integrate his German nationalism – and that of his followers – into home-grown narratives of national renewal and regeneration. In the wake of the Franco-Prussian War, “French Wagnerians stayed away from political issues of all kinds, except for some abstract social observations, since any such discussion led them into dangerous territory.”Footnote 41 Symbolist and aestheticizing approaches prevailed among professional writers and artists. Towards the end of the century, however, Wagner and his works were “ideological weapons in the cultural battles between Left and Right that followed the Dreyfus Affair” of 1894, where both factions attempted to redefine French identity from a traditional pro-Republican or a more recent national-conservative vantage point.Footnote 42 Representatives of the latter, for example the composer and music educator Vincent d’Indy, believed that “Wagner’s stress on the nation, on the instincts over reason, and on the power and directive force of myth,” especially in the Ring and Parsifal, complemented the ideals of the Ligue de la Patrie Française which worked towards a conservative regeneration of French culture.Footnote 43 Republican commentators, by contrast, emphasized the egalitarian and universal values in Wagner’s works, but turned away from the Ring, which had been co-opted by the nationalist mysticism of the right-wing leagues, and towards Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg as the perfect expression of “communal solidarity of an artisan culture.”Footnote 44

There were similar trends in Russia and the early Soviet Union. Wagner reception shifted from rejection of his works in the name of artistic realism – as expressed by Vladimir Stasov and Tolstoy – to their passionate embrace by the next generation of symbolist artists who strove for inner regeneration with strongly religious overtones, only to be superseded in turn by a more extrovert and populist approach in the wake of the Revolution of 1905 and again after 1917.Footnote 45 Wagner’s revolutionary credentials and his criticism of bourgeois society and capitalism were duly stressed, and poets such as Alexander Blok and Andrei Bely integrated the apocalyptic imagery of Götterdämmerung into their interpretations of the Russian present and future. Like many contemporary artists, they were attracted by the idea of a “theater-temple,” which would serve as a rallying point for national culture in the same way that Bayreuth – at least when viewed from abroad – had become the cultural center of Germany. In the early years of Soviet rule, the Wagnerian concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk was used to create new types of multimedia, participatory theatrical spectacles, until the onset of Stalinism once more rejected Wagner as politically suspect and morally dangerous.

George Bernard Shaw’s The Perfect Wagnerite (1898) offers the most comprehensive political exegesis of the Ring cycle.Footnote 46 Shaw regards the tetralogy as an “essay in political philosophy,” with Wagner’s “picture of Niblung-home under the reign of Alberic [as] a poetic vision of unregulated industrial capitalism.”Footnote 47 Shaw was neither the first nor the last to highlight the critical potential of the Ring, but, rather than inserting the music dramas into a larger argument, as most other commentators did, he developed his allegorical reading out of a desire to explain the meaning of the artwork to the wider public. He does so by hijacking the format of the plot synopsis, the indispensable companion of the opera-going public, making it attractive through his witty style – a rarity in any writings by or on Wagner – and irreverent observations. Das Rheingold thus becomes a parable for the destructive force of the “Plutonic power” of the gold which subjugates and exploits the dwarves, i.e. the working classes toiling in an underground mine that “might just as well be a match-factory with … a large dividend, and plenty of clergymen shareholders.”Footnote 48 The gold likewise corrupts the gods, the higher beings and lawgivers, who in turn harness the power of the lie (personified in Loge) to deceive the giants, i.e. the manual laborers, who expect them to uphold contracts and social order. Since the gods have failed to “establish a reign of noble thought, of righteousness, order, and justice” and disgraced themselves through their lust for power and gold,Footnote 49 Wotan realizes that they will be superseded by a yet higher form of existence, the hero. This hero appears in the guise of anarchist Siegfried “Bakoonin” (i.e. Bakunin), who disregards the lure of the gold and recklessly sweeps aside the old order. For Shaw, Siegfried was the “type of the healthy man raised to perfect confidence in his own impulses by an intense and joyous vitality which is above fear, sickliness of conscience, malice, and the makeshifts and moral crutches of law and order.”Footnote 50 The goal of the Ring allegory is thus not a benign vision of liberation for the toiling working classes but the advent of the new (super)man (i.e. Nietzsche’s Übermensch). Nevertheless, he had second thoughts about the efficacy of Siegfried-style anarchism.Footnote 51 Only a few pages later, he classifies it as an ineffective panacea, since in modern industrialized society anarchism would “always reduce itself speedily to absurdity.”Footnote 52

Shaw’s uneasiness about Siegfried as the answer to the Ring’s dilemmas are due not only to his misgivings about anarchism but also to his rejection of the concluding part of the tetralogy, translated Night Falls on the Gods. With Siegfried’s awakening of “Brynhild,” the political-philosophical allegory breaks down and disintegrates into conventional opera. If in Die Walküre she was “the truth-divining instinct in religion, cast into an enchanted slumber and surrounded by the fires of hell lest she should overthrow a Church corrupted by its alliance with government,” she has now become a thoroughly theatrical character, “a majestically savage woman, in whom jealousy and revenge are intensified to heroic proportions.”Footnote 53 Siegfried has likewise transformed from natural vitality personified to a “man of the world.”Footnote 54 In this context, Shaw argues, the vestiges of the allegorical plot, such as the Norns’ scene, Waltraute’s narrative, and Alberich’s nocturnal colloquy with Hagen, make no sense anymore. Even the intimate link between music and meaning is severed when Brünnhilde finishes her final monologue with a musical theme that has no discernible narrative significance and “might easily be the pet climax of a popular sentimental ballad.”Footnote 55 Shaw’s disappointment at the operatic betrayal of the political allegory is palpable. While at first he did not investigate it further, he added some thoughts on Wagner’s motives to a 1907 German translation, which subsequently were incorporated into the third English edition. The political developments between 1853 and 1876, Shaw argues, demonstrated that Siegfried had to be a failure, since the Alberichs, Wotans, and Loges were so effortlessly victorious in contemporary society.Footnote 56 Real capitalism just does not work in the way that Wagner’s characters deal with the Rhinegold, and Alberich the successful financier cannot be superseded by an anarchist hero: By the 1870s, even Wagner had given up on him.Footnote 57 Shaw overlooks, however, that Wagner had to have Siegfried die if he did not want to abandon the original saga; nevertheless, he correctly diagnoses the difficulties in interpreting the Ring after Wagner himself had shifted the emphasis from Siegfried to Wotan and from liberation to renunciation. Then as now, this in-built fault line is exasperating for anybody who attempts a unified allegorical, philosophical, or political reading of the Ring, but it is also one of the features that continue to attract divergent and contradictory interpretations.

Form Follows Function: Alfred Lorenz and Theodor W. Adorno

If thus far the music has played a subordinate role, this faithfully mirrors the early stages of the engagement with the Ring. Those commentators who were at all willing to consider the musical language often stopped at the most prominent aspect, the leitmotif, highlighting how it added meaning and articulation to the situations and concepts expressed in the poetry. By the turn of the century, this limited approach became problematic, not least because the emerging academic discipline of Musikwissenschaft increasingly demanded technical tools to describe its subject matter in a “scientific” way. Guido Adler, chair of music at Vienna University, poured scorn on the “exegetes who stopped, in childish contentment, at finding this or that motive in such and such a place, and labelling individual motifs. … What really matters, the relationship of thematic work to poetic content, the orchestral to the vocal parts, to the scenes, sub-scenes and … acts could not be covered by these attempts.”Footnote 58 One of the first coherent, all-encompassing explanations of Wagner’s musical form was written by an accidental musicologist, Alfred Lorenz, who submitted his dissertation on the Ring at Frankfurt University in 1922, having been dismissed as music director at Coburg and Gotha three years earlier.Footnote 59 The study was published in 1924 as Das Geheimnis der Form bei Richard Wagner (Richard Wagner’s Mystery of Form), by which time Lorenz had taken up a lectureship at Munich University. Lorenz rejects the charge of formlessness, the attempts to salvage remnants of traditional “numbers,” and the division of recitatives and arias in the Ring. Instead he proposes that each act is divided into ten to twenty “periods” – a term inspired by Wagner’s own dichterisch-musikalische Periode (poetic-musical periods).Footnote 60 These periods are internally unified through tonality, melodic punctuation (cadences), the use of identical or related motivic-thematic material, and less tangible elements like orchestral timbre or dynamics. The distribution and repetition of the themes determines the overall shape or form of each period; Lorenz suggests nine different types such as simple repetition, strophic form, arch forms, rondo and refrain forms, and bar form.Footnote 61 These orderly periods, Lorenz is at pains to point out, are not simplistic labels or concessions to tradition but subconscious reflections of Wagner’s “dark creative urge, becoming the representation of a distinctive Will that could not be otherwise, the exterior visualisation of unlimited logical thought processes.”Footnote 62 Lorenz’s notion of Wagnerian form is thus grounded in a particular understanding of creativity which also informed his view of music historiography. While organicist theories were by no means unique in the 1920s – Heinrich Schenker’s approach to musical form is based on a similar understanding of artFootnote 63 – Lorenz took them further by putting his ideas to the service of the emerging National Socialist movement. He was the only professor of Munich University who joined the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP) before 1933; he took a leading role in several Nazi organizations, and frequently invoked Wagner as Hitler’s spiritual precursor.Footnote 64 While his cultural conservatism – a movement that gained momentum in the Weimar Republic and for many transformed effortlessly into National Socialism – is beyond doubt, it is, however, perhaps too simplistic to label his analytical method “an embodiment of National Socialist ideology.”Footnote 65

Although Wagner’s life and works were certainly put to use by the Third Reich, it is noteworthy that the Bayreuther Blätter, which had contributed significantly to the formulation and dissemination of Nazi cultural and racial agendas, did not publish any extensive Ring critiques in the 1920s and 1930s, whether musical or ideological. While they rejected any left-wing readings such as Shaw’s, it seems that the Ring had mainly lost its usefulness for scoring points in contemporary debates.Footnote 66 Thus it might have been the general complacency with Wagner’s popularity with the regime, rather than any coherent National Socialist appropriation of the Ring, that spurred Theodor W. Adorno into writing Versuch über Wagner (Essay on Wagner) in 1937–8 (revised and published as a book in 1952). While remaining an inspiring and provocative read, its lasting legacy has been to suggest how Wagner’s anti-Semitism permeates his creative imagination: “The gold-grabbing, invisible, anonymous, exploitative Alberich, the shoulder-shrugging, loquacious Mime, overflowing with self-praise and spite, the impotent intellectual critic Hanslick-Beckmesser – all the rejects of Wagner’s works are caricatures of Jews.”Footnote 67 If this thought was not exactly new – readers of Wagner’s late essay “Erkenne dich selbst” (1881) found the equalization of Alberich and Jewish finance fairly transparentFootnote 68 – it certainly became more prominent in late twentieth-century American scholarship (e.g., Paul Lawrence Rose and Marc Weiner),Footnote 69 who found Wagner’s creative output to be saturated with anti-Semitic coding. Adorno, however, aims at a higher target altogether. Wagner’s personality and his creative persona are intimately intertwined with the crisis of bourgeois society where even a rebellious gesture is – in one of Adorno’s dialectic reversals that oscillate like the magic fire music he so abhors – a sign of acquiescence with the powers of state and capital. Wagner “is an early example of the changing function of the bourgeois category of the individual. In his hopeless struggle with the power of society, the individual seeks to avert his own destruction by identifying with that power and then rationalizing the change of direction as authentic individual fulfilment.”Footnote 70

In contrast to many Wagner critics, Adorno does not stop at a damning dissection of Wagner’s character or his writings. A considerable part of his essay is devoted to a discussion of Wagner’s musical techniques, because he claims – half a century before the New Musicology – that “the key to any artistic content lies in its technique.”Footnote 71 For example, the use of a parlando style in opera buffa has potential for “bourgeois opposition” against the powers of the ancient regime whereas, in Wagner’s later works, recitative “deserts irony for pathos.” In the hands of Wagner the reactionary revolutionary, language is forced to “wrest a new form of magic from the disenchantment: bourgeois language should sound as if Being itself were being made to speak.”Footnote 72 Likewise Wagner’s reluctance – or inability – to create themes rather than motives and his rejection of conventional forms are explained as consequences of his ideological ambiguities. While Adorno draws on examples from the Ring throughout the essay, its final chapters, especially chapter 9 “God and Beggar,” are given over to a dissection of the tetralogy. He focuses on the encounter between Wotan, the representative of the old order, and Siegfried, seemingly the rebel and harbinger of a new time, in act three of Siegfried. However, Adorno subverts the familiar reading by arguing that the victor necessarily succumbs to the power of the Ring, because “betrayal is implicit in the rebellion.”Footnote 73 “The conflict between rebellion and society is decided in advance in favor of society, because the latter recruits the opposition for the bourgeoisie, a process which Wagner then presents as entirely natural or even transcendental in his operas.”Footnote 74

It is hardly surprising, then, that Adorno reads the finale of Götterdämmerung as a cinematic happy ending that thinly disguises its commodity character with the perfect, ultimate phantasmagoria.Footnote 75 At the end of the essay, there is hardly any aspect of Wagner’s artistry left that could – or should – be experienced with anything approaching pleasure. Adorno allows Wagner some self-reflective clear-sightedness that in itself is part of everything that is wrong with late-bourgeois society: “Wagner is not only the willing prophet and diligent lackey of imperialism and late-bourgeois terrorism. He also possesses the neurotic’s ability to contemplate his own decadence and transcend it in an image that can withstand that all-consuming gaze.”Footnote 76 Although Adorno resorts here to a visual metaphor, it is clear that Wagner’s music is the true culprit. There is a vague hope that in some instances, such as the dark passages of the third act of Tristan, music, “the most magical of all the arts, learns how to break the spell it casts over the characters. … It is the rebellion – futile though it may be – of the music against the iron laws that rule it, and only in its total determination by those laws can it regain the power of self-determination.”Footnote 77 Adorno’s dialectic somersault catapults him into the company of desperate Wagnerians who want to salvage at least the beloved music from the rubble of the catastrophe of the twentieth century. But even then, the myth and the music of the Ring seem beyond redemption.Footnote 78

Postwar Professionalization: The Ring in Academia and on the Stage

Since Adorno’s Versuch über Wagner was published in 1952 (the English translation in 1980), its reception precedes the first wave of attempts to reclaim Wagner’s works for the political “left,” notably in the writings of the too-little known Hans Mayer as well as some of Adorno’s later essays.Footnote 79 However, the debate about the meaning and interpretation of the Ring increasingly migrated from the public arena, where writers like Nietzsche and Shaw attracted huge followings, into academic circles. The postwar decades saw several comprehensive Ring interpretations, beginning with Robert Donington’s Wagner’s “Ring” and Its Symbols (1963). His Jungian approach to the Ring develops a wealth of archetypal images which, he argues, are spontaneously understood by the listener, because the myths as retold by Wagner offer “a distillation of human experience.”Footnote 80 If listeners want to unravel these symbols, they need to pay attention to music and poetry, since both “work together in expressing that ‘deep and hidden’ truth of whose underlying presence Wagner was himself aware.”Footnote 81 Donington approaches the music through the leitmotifs since a “musical motive is a symbolic image … combinable into compound images by symphonic development and contrapuntal association.”Footnote 82 In his exploration of Die Walküre act three, for example, “Brynhilde” is explained as Wotan’s “anima,” the “representative of his inner femininity,” as are the somewhat hysterical Valkyries, hinting at schizoid tendencies in Wotan who is – after his quarrel with Fricka and Brynhilde’s disobedience – “estranged from his inner femininity.” Such a “psychotic disposition” can ultimately be traced back to the Ring’s creator, Wagner, who nonetheless brought his “healing instinct” to working out “his deepest problems through his work.”Footnote 83 Whether or not today’s readers find Donington’s Jungian explanations convincing, his book formalizes the indebtedness of modern psychology to Wagner’s mythical cosmos which many fin de siècle artists, not least Thomas Mann in his novels, had instinctively grasped.

Donington’s approach was sharply criticized by the British musicologist Deryck Cooke, who argued that any attempt to discover what Wagner meant by the Ring had to fulfill four conditions: it had to absorb each of Wagner’s own intentions; it had to respect the “overt meaning of each element in the drama”; it had to maintain the “degree of emphasis placed by Wagner on each element”; and it should even leave the work “to speak for itself in the theatre” without putting “ideas into the reader’s head” that do not relate to the theatrical experience.Footnote 84 More than any other writer before him, Cooke places the music at the center of his analysis, since it carries the ultimate meaning.Footnote 85 Based on the optimistic assumption that music functions like a language and that the Ring displays thematic and symphonic unity, his actual musical investigation is a mixture of motivic and harmonic analysis, working in close tandem with a deep reading of the text and its literary sources. Unfortunately, Cooke’s premature death allowed him to complete only the textual reading of Rheingold and Walküre; the volume containing the musical analysis remained unwritten. However, even had he completed the monumental task, it is questionable whether his book would have remained the last word in Ring interpretations. His belief that “the puzzle of the Ring” – i.e. Wagner’s intended meaning – can be solved through “objectivity in interpretation” and “comprehensiveness in musico-dramatic analysis” (thus the headings of the introduction) might have been swept away by the rise of poststructuralism, which seriously undermined the belief in a definitive meaning of artworks that awaits uncovering. Nevertheless, his close readings of the Ring text remain inspiring in their attention to detail and mythological background, balancing psychological insight with commonsense observations.

One – perhaps unintentional – result of Donington’s and Cooke’s studies was to shift the focus of twentieth-century Ring interpretations from the Wotan–Siegfried dualism to Brünnhilde. Cooke astutely observes that Brünnhilde, by defying her father, reveals herself as the free hero Wotan longs for, something that “the ruler of the old European man-dominated civilization” is too blind to see.Footnote 86 The altered emphasis made possible Jean-Jacques Nattiez’s study Wagner Androgyne (1990), where he takes an idea from Wagner’s famous Ring letter to August Röckel to its logical conclusion: “Not even Siegfried alone (man alone) is the complete ‘human being’: he is merely the half, only with Brünnhilde does he become the redeemer … for it is love which is really ‘the eternal feminine’ itself.”Footnote 87 Nattiez then argues that androgyny plays a central role. First, because “the myth around which the Ring revolves may be read as a metaphorical reenactment of Wagner’s conception of the history of music; and second, that throughout his life, Wagner’s theory of the relationship between poetry and music is reflected, in his music dramas, in the relations between man and woman.”Footnote 88 More precisely, it is the relationship between Siegfried and Brünnhilde that springs from the same well as Wagner’s theoretical speculations, laid down in the Zurich writings. Thus, Nattiez achieves a structural equivalence between Wagner’s prose writings and his creative imagination, an idea that was further developed, with greater attention to the actual music, in Thomas S. Grey’s Wagner’s Musical Prose (1995).Footnote 89 Feminist Wagnerians in turn reacted against this positive reading of Wagner’s sexual politics. For example, Eva Rieger stresses that redemption is by no means a defiant, liberating, or empowering act for the female characters but a task that they fulfill as a service to the still-dominant and domineering male heroes – the composer himself not excepted.Footnote 90 Like the majority of current Wagner scholars, Rieger uses the music dramas – and the Ring in particular – to construct a comprehensive panorama of nineteenth-century attitudes and ideas. A further example of this approach is Mark Berry’s Treacherous Bonds and Laughing Fire (2006), which restores the balance between two approaches to the Ring that are traditionally seen as mutually exclusive: the revolutionary, Feuerbachian and the resigned, Schopenhauerian reading.Footnote 91 Berry argues that, in the completed work, there is no simple either-or, although chapters on property, capital, and production, law, and religion show a certain preference for a revolutionary Wagner – a not unwelcome antidote to a century of Schopenhauerian renunciatory pessimism.

Since the 1950s, however, the theatrical stage has become the main arena for philosophical, symbolic, or ideological readings of the Ring. Thus, it is increasingly directors – or stage directors working in tandem with Wagner scholars, such as Wieland Wagner with classicist Wolfgang Schadewaldt – who offer novel interpretations of the Ring. While stage designers Adolphe Appia and Emil Preetorius were the first to abandon conventional, representational stagings, it was Wieland Wagner’s “New Bayreuth” of the 1950s that forcefully demonstrated that stage design, costumes, and Personenregie had an important role to play in highlighting hitherto unsuspected perspectives on the tetralogy.Footnote 92 Wieland’s Hellenistic aesthetics emphasized a metapolitical classicism, so ingrained in the German Bildungsbürgertum, at the expense of contemporary commentary or an accounting with the recent past.Footnote 93 Many Wagner lovers were (and still are) unsettled by the question of whether these new performative approaches uncovered genuine facets of Wagner’s creative vision, or whether directors have been projecting their personal agendas onto the works. There is no doubt that stagings responded to the political climate in the divided Germany. In the early decades of the German Democratic Republic, i.e. East Germany, uneasiness about the perceived bleak nihilism of Götterdämmerung prevented complete stagings of the tetralogy until Joachim Herz’s Leipzig Ring of 1973–6, which was the first to embrace Shaw’s socialist ideas while trying not to be appropriated wholesale by state ideology.Footnote 94 Landmark productions in West Germany, by contrast, confronted the Nazi past, notably in the Brechtian staging by East-German director Ruth Berghaus at Frankfurt in the 1980s.Footnote 95 The 1976 centenary Bayreuth Ring directed by Patrice Chéreau was thus only one of several productions that historicized Wagner’s nineteenth-century worldview, while pointing out the Ring’s relevance for contemporary audiences. More recent productions have, meanwhile, given up on offering unified readings of the Ring, whether of Wagner’s alleged intentions or the director’s worldview. In line with postmodern sensibilities, the mere suggestion of making sense of the Ring has come under scrutiny, and thus it was in a sense an opportunity when director Herbert Wernicke died after premiering his highly self-referential Rheingold and Walküre in Munich in 2002, leaving others to complete the cycle. The Stuttgart State Opera (2002–3) confronted the issue of multiple meanings head-on by inviting several artists – Joachim Schlömer, Christoph Nel, Jossi Wieler and Sergio Morabito, and Peter Konwitschny – to direct one opera each, with widely differing approaches. Whether this strategy is a reflection of a postmodern loss of artistic confidence or a welcome response to the multiple layers of meaning floating always already in and through the Ring depends very much on the predisposition of the individual listener.

All these postwar interpretations, whether written or staged, take Wagner’s works as their starting point, which they then analyze with reference to broader historical or philosophical discourses. The opposite approach – to insert the Ring into a fully developed worldview – has practically come to an end. Philosophers like Alain Badiou or Slavoj Žižek, who repeatedly – and not just in music-related writings – refer to Wagner, have become the exception rather than the norm. Interestingly both were invited by the German weekly Die Zeit to comment, along with singers, directors, and writers, on the Wagner bicentenary in 2013, thus asserting their role as public intellectuals, and both focused their reflections on the Ring. Badiou stresses the tragic dimension and Brechtian alienation at the end of Götterdämmerung in particular, thus defending the tetralogy (which he first encountered in postwar Bayreuth in 1952) against the charge of protofascism.Footnote 96 Žižek hears in the same scene somewhat more conservatively Brünnhilde’s transformation from erotic love to political agape, making her the leader of the new, nonpatriarchal collective.Footnote 97 However, general debates about the (post)modern condition hardly ever use Nibelheim or Valhalla as their vanishing point. John Deathridge’s interpretation of one of Rheingold’s most enigmatic characters is certainly worth considering: “The cold fire of calculating reason represented by Loge has indeed won out in a management-obsessed world demonized by objectification (the obsession with news, for instance) and by what Wagner and his socialist confrères in the 1840s would have almost certainly regarded as the fatal isolation of Internet mania and mobile phone conversations on windy pavements.”Footnote 98 A stage director could certainly show Loge swiping through images on his tablet or conjuring up a Matrix-style 3D-projection of his search for “Weibes Wonne und Wert,” for sure a relevant updating of Wagner’s critique of contemporary values and behaviors. However, it is highly unlikely that advocates or critics of the digital economy would consider the Ring as the obvious starting point for their judgment of the world we live in today, quite in contrast to thinkers like Nietzsche, Shaw, or even Adorno, who keenly felt that the world had to learn from Wagner’s (good or bad) example. While there is certainly still demand for new interpretations of the Ring cosmos, the Wagnerian world-interpretations so much in evidence between 1880 and 1930 definitely seem to have become a thing of the past, a renewed appetite for world-size mythological dramas like Game of Thrones notwithstanding.

Wagner first publicly unveiled the poem for the Ring cycle as a work of literature. “[It] will be … the greatest poem that has ever been written,”Footnote 1 he puffed optimistically to Theodor Uhlig in 1852, before distributing fifty printed copies. Thomas Mann had qualms on reading this sixty years later, observing that even if Wagner’s literary poems had not been written in the language of opera texts, they would still fall short of such a boast, and that such a remark – sidelining the “colossal oeuvre” of Shakespeare, Goethe, Balzac, Homer, Dante, Cervantes, Lesage, and Gogol – “could only have come from an artist whose intellect/character was depressingly incommensurate with his talent.” It is hard not to sympathize with Mann’s position. Talent alone does not make for greatness, he continues. And what is it that Wagner lacks? Literature. “It is the lack on which he prided himself all his life as a virtue, and which the Germans have likewise always regarded as a virtue in him.”Footnote 2 What he meant was that Wagner devalued “literary dramas for silent reading” in favor of “living” drama for enactment (and for this reason privately regretted distributing those printed copies of his Ring poem in 1853).Footnote 3 While the “ancillary-words” and “complicated phrases” of silent literature appealed to the imagination, Wagner argues, drama appealed to the senses. Literature was a natural consequence of “the evolution of understanding out of feeling,” that is, fruit of the very alienating process he sought to undo.Footnote 4 Such an insult might have dissuaded serious writers from engaging with Wagner’s works. It seems faintly ironic, then, that nine years before receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature (1929), Mann confessed privately, “Wagner is still the artist I understand best, and in whose shadow I continue to live.”Footnote 5 This distinction between forms of “literature” bears consideration. What about Wagner’s works and stature cast such a shadow that, despite his hostility, they put Europe’s belletrists in the shade?

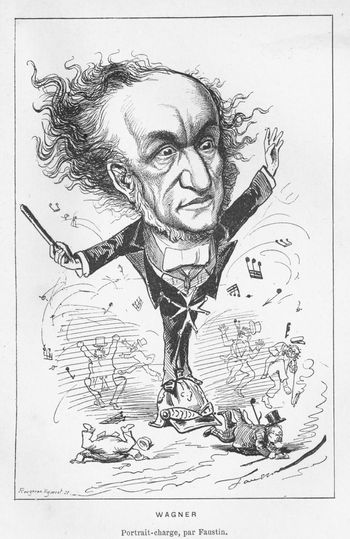

Consider another perspective. The German pedagogue and founder of the London Wagner society, Edward Dannreuther, parroted Wagner’s theoretical writings in 1872 when he declared the composer “a poet first and foremost,” pronouncing him “formidable as a writer” because he was “perfectly conscious of all his mental evolutions” and wrote about them with a cool, Goethean detachment.Footnote 6 Regardless of whether we accept this, Dannreuther gave voice to popular assumption by entitling his second book Wagner and the Reform of Opera (1873). It posited Wagner as an aggrandizing, visionary reformer who secured lasting fame since conceiving Der Ring des Nibelungen as a “stage festival play” unfettered from Franco-Italian convention, a work that eschews “conventional forms, the recitative secco and the aria” as impediments to true expression, forms that “have imposed their fetters upon every composer … [and] hampered every poet.”Footnote 7 Critical opinion was far from marshaled on the matter. But with increased performances of Wagner’s works during the late 1870s and early 80s, the results of such reform – continuing momentarily Dannreuther’s distorting cliché – appeared persuasive to a public nourished on warm critical endorsements. However unwittingly, the famed cottage industry of satirists depicting the “power” of Wagner’s reformed art only served to feed such assumptions, while skewering efforts to take his music too seriously. In the case of Faustin Betbeder’s evocation of the premiere of the Ring cycle in 1876, given in Figure 12.1, an oversized head and baton/wand whips up soundwaves into such a swirling mass that it devastates mere individuals caught in its field: Witness the ridicule of an artistic hurricane, the fruit of Wagner’s disruptive operatic reform.

Figure 12.1 Faustin Betbeder, “Wagner,” Figaro September 26, 1876.

These two strands of Wagner’s early posthumous identity – an immensely talented composer disparaging of silent literature; a reformer of opera – are inextricably entwined. In this chapter, I ask how the one relates to the other for literary writers responding to the Ring cycle. Dannreuther’s fifty-seven-column entry on Wagner for the first edition of Grove’s Dictionary, reiterated his message in primary colors: “Broadly stated, Wagner’s aim is Reform of the Opera from the standpoint of Beethoven’s music,”Footnote 8 and asserted a forcedly a neat link-up between sounds heard and words read, where Ring validated Wagner’s controversial theories of Versmelodie, thematic motifs, and orchestral commentary: “to us who have witnessed the Nibelungen … the entire book [Opera and Drama] is easy reading.”Footnote 9 Such were prominent views reflecting Wagner’s identity around the time of Mann’s birth in 1875. Accordingly, the following reflections divide into two interrelated critiques: Wagner as a reformer of opera; the Ring as a work of literary fascination.

Early Essays

Given Wagner’s legacy as a reformer, we may wonder at its origins. The so-called Young German movement – an opposition group of left-leaning writers critical of autocratic rule and sympathetic to French socialist ideals and the idea of a unified German nation – offers one background for the impulse to enact change. In his sympathies for the movement, Wagner established an early bond with Heinrich Heine, a fellow expatriate in Paris whose name had been on the Bundestag resolution of December 10, 1835 against the group’s writings.Footnote 10 Even before the twenty-one-year-old composer joined Heine in the French capital, admittedly, he writes of the need for opera to exceed its national traditions, rousing readers to “take the era by the ears, and honestly try to cultivate its modern forms; and he will be master, who writes neither Italian, nor French – nor even German.”Footnote 11 Wagner would reflect critically on the nature of an ideal German character for decades, of course. In like spirit, Heine ridiculed the political scene (Neue Gedichte, Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen) but took aim specifically at art music for being blithely disconnected from matters of social concern. While gorging on the “Marseillaise” booming beneath his window, Heine condemns art music as powerless in the face of such rabble-rousing anthems.Footnote 12

That Wagner’s setting of Heine’s “Les deux grenadiers” incorporates the Marseillaise (three months after his arrival in Paris) offers grounds to suspect the composer was both aware of and sympathetic to Heine’s complaint. By 1848, with the authority of public office, his attitude had hardened enough to warrant public criticism; he remodeled Heine’s concern as the subjugation of artists’ creativity in Art and Revolution (1848): “What [has aggrieved] the musician, when he must compose his music for the banquet-table? And what the poet, when he must write romances for the lending library? … That he must squander his creative powers for gain, and make his art a handicraft!”Footnote 13 Other Young Germans were still more assertive in their contempt for the disconnect between instrumental music and bracing social realities. A fuller case is articulated by literary critic Ludolf Wienbarg, for whom the escapism of “refined” art music created a moral solipsism that blots out suffering. Music truly expressive of “silent dissonances within our breast … would drown out the music of the angels and bring forth the shrillest discords from the throne of harmony itself” he explains.Footnote 14 Such sentiments may offer one reason why Wagner remained a self-styled dramatist reluctant to acknowledge his identity as composer, even during the composition of Götterdämmerung.Footnote 15

At the age of twenty-seven, the composer famously reflected on German musical character in a short essay rooted in Ludwig Tieck’s writings. On German Music (1840) placed this character starkly at odds with the spectacle and virtuosity of the Opéra and the cult of celebrity that characterized the principal singers of the Théâtre-Italien. “The German cannot impart his musical transports to the mass, but only to the most familiar circle of his friends,” Wagner tells his French readers. “Music in Germany has spread to the lowest and most unlikely social strata, nay, perhaps here has its root.”Footnote 16 (The attempt to define the terms of the question Was ist Deutsch? runs like a red thread through Wagner’s writings between at least the essays of 1834 and 1878, and both he and Heine would satirize the enterprise by 1840.Footnote 17) Patent exceptions to the low standing of German opera – Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte (1791) and Weber’s Der Freischütz (1821) – merely proved – he felt – that German opera is at home only within the sphere of fairy tale.Footnote 18

Beyond confirming domestic instrumental music as the German vernacular, this 1840 essay laid the ground for an identity problem that would occupy Wagner for decades: “[i]t is not to be denied that the grander genre of dramatic music does not flourish in Germany of itself; and apparently for the same reason that the higher type of German play has never reached its fullest bloom.”Footnote 19 How, a concerned reader might ask, should Germanic theater flourish and be true to itself? In a decade during which Shakespeare was claimed as a native German and Meyerbeer a naturalized Parisian, national identity and affiliation were both flexible and chosen. Whether motivated in the context of aesthetic or nationalist discourses, the German question acknowledges a positional weakness vis-à-vis French and Italian traditions and, guarding against frail teleologies, it is in this context that we may start to investigate Wagner’s identity as a reformer.

Aborted Reforms at Dresden

At the age of thirty-four, Wagner’s impulse to reform German theater first found its public voice. The year was 1847. Twelve months earlier, Wagner had submitted a formal entreaty to reform and reorganize the Dresden Court Theater; he waited over a year for a response. The document, Regarding the Royal Chapel (Die Königliche Kapelle betreffend) sets out a practical case for pensioning off old or inadequate players, appointing new players in key roles, apportioning players between heavier and lighter operas (to avoid fatigue), updating old instruments (timpani, double-pedal harps), redressing discrepancies between the salaries of certain orchestral players, and rearranging the layout of the orchestra the better to enable lines of sight.Footnote 20

During July 1847, August von Lüttichau, Intendant at the Dresden Theater, informed Wagner his proposals had been rejected without further explanation: “I broke definitively with Lüttichau,” Wagner confessed privately.Footnote 21 The moment was pivotal; it was the last time Wagner had the opportunity for advancement within a municipal institution, and, in effect, before embracing the identity of an outsider. After his proposal was dismissed, Wagner went from febrile frustration (in August):

I am so full of utter contempt for everything connected with the theatre as it stands at present that – being unable to do anything about it – I have no more ardent desire than to sever all links with it, and I regard it as a veritable curse that my entire creative urge is directed towards the field of drama, since all I find in the miserable conditions which characterize our theatres today is the most abject scorn for all that I do.Footnote 22

to outright revolt (in November): “There is a dam that must be broken down here, and the means we must use is Revolution … A single sensible decision from the King of Prussia with regard to the opera house, and all would be well again!”Footnote 23

Of course, the fractious character of social reform was long familiar to early nineteenth-century Europeans, and Wagner’s efforts in 1846–7 are far from singular for the period. Wagner came of age during the post-Napoleonic retrenchment of rights, and his radical conclusion – in a string of essays from 1848–9 – linked urges towards artistic reform with those governing the reshaping of social institutions and prevailing middle-class values.

We find this to varying degrees in publications of 1849:

Plan for the Organization of a German National Theater in the Kingdom of Saxony

On Edward Devrient’s History of Acting (not accepted by the AAZ)

The synonymy of political and artistic reforms in Wagner’s mind emerges explicitly in 1849 when he asks his close acquaintance, the Berlin music critic Karl Gaillard, to place “Theater Reform” in a Berlin newspaper, adding: “perhaps [the title] ‘German Reform’ will suffice for present purposes.”Footnote 24 In rhetoric, he effortlessly blended artistic matters with social reformist principles – and their implied violence. The essay Revolution (attributed to Wagner in the Sämtliche Schriften und Dichtungen but published anonymously in the Volkszeitung without surviving holographs, and whose authorship therefore remains unproven) left little doubt as to the radical nature of urges towards artistic reform and their translation into civic engagement: “If we look out across nations and people, we recognize everywhere throughout the whole of Europe the fermenting of a violent movement, whose first vibrations have already seized us, whose full fury already threatens to close in on us.”Footnote 25 The notion that “true Art is revolutionary, because its very existence is opposed to the ruling spirit of the community,” sets Wagner’s brand of mid-century reformism apart from other figures in the history of opera.Footnote 26

Operatic Reform: A Brief History

Histories of opera are of course studded with debate concerning local conventions. And textbooks record several calls – Wagner’s included – to reform the genre by reviving ancient Greek tragedy. Since its inception in the late sixteenth century, the raising of speech-like utterance and dialogue to monody reflects a humanist impulse predicated on the prestige of Greek practice. In 1634, Pietro de’ Bardi (fils) wrote of Vincenzo Galilei “restoring ancient music … to improve modern music,”Footnote 27 while Marco da Gagliano praises Ottavo Rinnucini and Jacopo Corsi for “having repeatedly discoursed on the manner in which the ancients used to represent their tragedies, how they introduced their choruses, whether they employed song, and of what kind, and similar matters.”Footnote 28 For humanists like Galileo, opera itself was less an invention than a revival.

Wagner disagreed. As early as 1851, he complained of “an entirely misconstrued Greek mythology” in which “the whole apparatus of musical drama [aria, dance music, recitative] – unchanged in essence down to our very latest opera – was settled once and for all.”Footnote 29 By 1872, writing with the confidence of Germany’s unification behind him, he reflected on what he saw as the specious reasoning that had concealed a flaw in the genre from the outset:

Italian opera is the singular miscarriage of an academic fad, according to which, if one took a versified dialogue modelled more or less on Seneca, and simply got it psalm-sung as one does with the church-litanies, it was believed one would find oneself on the high road to restoring antique tragedy, provided one also arranged for due interruption by choral chants and ballet-dances.Footnote 30

That Wagner was consistent in this view indicates a hard kernel, a leftover that cannot easily be ascribed to an ideology of 1848–9, neither literary fantasy nor anti-Italian prejudice alone.

To take a second example of operatic reform, in the middle of the eighteenth century attitudes towards antiquity were tempered by appeals to Enlightenment ideals of progress, with Vincenzo Manfredini advocating that “to convince oneself that modern music … is absolutely better than ancient music, it is enough to compare good modern compositions with ancient ones.”Footnote 31 Manfredini’s caution against venerating tradition was aimed at conventions of opera seria. He was writing in the wake of Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice (1762), whose reforms the composer and his librettist – Ranieri de’ Calzabigi – would summarize in the preface to Alceste (1769):

I resolved to divest [Alceste] entirely of all those abuses, introduced to it either by the mistaken vanity of singers or by the too great complaisance of composers, which have so long disfigured Italian opera … I have striven to restrict music to its true office of serving poetry by means of expression and by following the situations of the story, without interrupting the action or stifling it with a useless superfluity of ornaments.Footnote 32

Historically speaking, Wagner’s writings on singers largely amplify rather than add to these principles, though the conventions against which each composer worked were different (and Wagner supplied an entirely new linguistic apparatus). According to Manfredini, Gluck inveighed against such practices as: (i) repeating the words of the first part of an aria four times, and the words of the second only once; (ii) stipulating between two and four cadenzas; (iii) adhering first to formal convention, and only then to dramatic situation; (iv) vocalizing on syllables favorable to the voice before the end of the word in question; (v) making conspicuous display of vocal agility in long drawn-out passages. Wagner, for his part, became irritated by conventions of end-rhyme, iambic meter, melodically unsuitable libretto translations, ad libitum cadenzas, and unmetrical recitative divorced from the natural rhythms of prosody. But such fixations served only to bolster his terminal verdict against the genre of opera, which he felt derived from principles of absolute music (rather than poetry) and hence was “dead at core … no longer an art, but a mere article of fashion.”Footnote 33 Of Gluck’s reforms, he acknowledges only that “the so famous revolution of Gluck, which has come to the ears of many ignoramuses as a complete reversal of the views previously current as to opera’s essence, in truth consisted merely in this: that the musical composer revolted against the willfulness of the singer.”Footnote 34 Despite elevating poetry above music, in other words, Gluck was no dramatist. In a court of law, it would be improper for the prosecution to present the case for the defendant (or vice versa) but, in the absence of standardized narratives for music history, this is effectively what happened during the mid-century. Wagner’s self-serving, potted histories of opera and stage drama – principally parts 1–2 of Opera and Drama – are often dazzling to modern readers in placing him at the apex of historical necessity. No fewer than twenty-seven German-language music periodicals were established between 1848 and 1860, and controversy only increased dissemination as Wagner’s views were widely discussed and propagated – however inaccurately – in the professional press.Footnote 35

However partial Wagner’s summaries may seem to us today, his insistence on the historically unprecedented nature of his music, beginning – he specified – with Tannhäuser (1845), found sympathy among writers of the next generation. Wagner wrote in 1864 to his Swiss confidante, Eliza Wille, of having embarked “upon a course that was as novel as it was fraught with difficulty,” and of how his “unspeakable suffering” from the birth pangs of such artworks bestowed on him “a superior right, an entitlement which … would have raised me far, far above the world and thus … would have made me inwardly a hallowed and blessed human being.”Footnote 36 This kind of attitude repulsed Nietzsche, who deftly inverted it: “one is an actor by virtue of being ahead of the rest of mankind in one insight: what is meant to have the effect of truth must not be true.”Footnote 37 Wagner’s claims for a “human gospel of the art of the future” would be so much self-aggrandizement but for the fact that they entered the water stream of European aesthetics, and – for a time – were readily imbibed. As ever, the discourse is enmeshed within Wagner’s own words and endeavors: the very existence of Bayreuth solidified his aura of uniqueness along with that of the Ring in 1876; it was a singular theater for a singular art – from architecture to atmosphere to acoustics – and hence epitomizes his claims for the historical uniqueness of his “stage festival play.”Footnote 38 Writing with all the wisdom of hindsight, Martin Geck still diagnoses Wagner as the prophet of art sought by his century: “he may not have been uncontroversial, but there is no doubt that he was unrivalled.”Footnote 39 It was a Kantian justification – identifying the natural genius principally by a criterion of originality – but also a powerful historical claim; it made Wagner central and yet radically extraneous to the institution of opera.

In the first part of his poetic obituary, Richard Wagner: Rêvue d’un poëte français (1885), Mallarmé echoes the composer’s sense of his own particularism: “The certainty that neither he himself nor anyone of this time will be involved in any similar enterprise liberates him from any restriction that might be placed on his dream by a sense of incompetence and by the gap between dream and fact.”Footnote 40 Wagner’s peculiarly singular artistic vision shields him from normative judgment, in other words, allowing him at least to lock eyes with the greater heuristic phantasms of art, if not quite slay them. (The Ring, for Mallarmé, remained unresolved and incomplete, its violated law of exchange is unrectified and its incest taboo unrecanted: “Le dieu Richard Wagner”Footnote 41 had scaled but “halfway up the holy mountain” [à mi-côte de la montagne sainte].)Footnote 42

Against such qualified praise, the question arises as to why, historiographically speaking, Wagner’s case, and that of the Ring in particular, has been treated as sui generis, as Wagner asserted it to be. What is it about the Ring – fruit of contested reforms – that led a generation of writers and philosophers to interpret the world through its expressive devices, its symbols, and its narratives? If the practical principles of Wagner’s reforms – from disciplining singers to seeking radically flexible forms and the primacy of drama – largely build on Gluck’s precedent, why did they encounter such a different reception?

The Ring in Literature

There are several routes a response to these questions could take. One would be that Wagner embarked on Der Ring des Nibelungen explicitly as a political revolutionary, that the work resonates long into the night of German modernism because it was conceived from the outset as “an onslaught on the bourgeois-capitalist order,” as John Deathridge put it. George Bernard Shaw had declared the Ring “a first essay in political philosophy” as early as 1901, a view that underscored his allegorical reading of it – in 1898 – as a poetic vision of unregulated industrial capitalism, where the much delayed composition of Götterdämmering almost becomes anachronistic: “an attempt to revive the barricades of Dresden in the Temple of the Grail.”Footnote 43 But there is little reason to attribute Wagner’s literary influence to this political identity, which – for those historical witnesses aware of it – appears incidental to the design of his musico-theatrical program (it goes unmentioned in most literary responses to the Ring: the Wagnerism of Wilde’s Algernon Moncrieff and Huysmans’ Jean des Esseintes has nothing to do with revolutionary politics and everything to do with psychological captivity and sartorial extravagance). Another answer would be that the Ring imputes a certain mythic symbolism to its musical devices, a symbolism that resonated profoundly with turn-of-the-century aesthetics where music is elevated above representational forms of art. Hence, the psychological function of leitmotifs, the musical sound of poetry, and the impulse to draw different artistic media together under the auspices of revivifying Greek theater. Still a third answer might point to Wagner’s reception as a literary persona, whose bold statements, strewn throughout his lengthy published essays, became attractive for a generation of artists regardless of medium. To take one example: “The artist addresses himself to feeling and not to understanding,” Wagner explains near the beginning of A Communication to My Friends (1851) in a statement that would become a mantra. “If he is answered in terms of the understanding, it is as good as saying he has not been understood.”Footnote 44 Walter Pater would influence a generation of writers and painters (“decadents”) by extending much the same argument in 1873, that aesthetic criticism depends on the cultivation of one’s receptivity to beauty as a function of pure sensory pleasure.Footnote 45 “What is important,” he explains, “is not that the critic should possess a correct abstract definition of beauty for the intellect, but a certain kind of temperament, the power of being deeply moved by the presence of beautiful objects.”Footnote 46 Here, it seems, composer and critic interlock cleanly in their aspirations for aesthetic communication.