Introduction

Since the late 2000s, the distinct field of ludomusicology has gained momentum. Reportedly, the neologism ludomusicology was coined by Guillaume Laroche and his fellow student Nicholas Tam, with the prefix ‘ludo’ referring to ludology, the study of games.Footnote 1 In early 2008, Roger Moseley also used this term and introduced an additional dimension to the meaning:

Whereas Laroche’s deployment of the term has reflected a primary interest in music within games, I am more concerned with the extent to which music might be understood as a mode of gameplay. … Bringing music and play into contact in this way offers access to the undocumented means by which composers, designers, programmers, performers, players, and audiences interact with music, games, and one another.Footnote 2

In this chapter, I will outline my approach I have developed at full length in my 2018 book towards a distinct ludomusicological theory that studies both games and music as playful performative practices and is based on that broader understanding. This approach is explicitly rooted both in performance theory and in the musicological discourse of music as performance.Footnote 3 The basic idea is that with the help of a subject-specific performance concept, a framework can be developed which provides a concrete method of analysis. Applying this framework further allows us to study music games as well as music as a design element in games, and performances of game music beyond the games themselves. It is therefore possible to address all three ludomusicological subject areas within the frame of an overarching theory.

Performance – Performanz – Performativity

Performance theory is a complicated matter, due to firstly, the manifold uses of the term ‘performance’ and secondly, the multiple intersections with two other concepts, namely performativity and Performanz (usually translated to ‘performance’ in English, which makes it even more confusing). Due to these issues and a ramified terminological history, the three concepts as used today cannot be unambiguously traced back to one basic definition, but to three basic models as identified by Klaus Hempfer: the theatrical model (performance), the speech act model of linguistic philosophy (performativity) and the model of generative grammatics (Performanz).Footnote 4 Despite offering new and productive views, the evolution of the three concepts and their intersections has led to misreadings and misinterpretations that I have untangled elsewhere.Footnote 5 For the purpose of this chapter, it is sufficient to be only generally aware of this conceptual history, therefore I will confine the discussion to some aspects that are needed for our understanding.

The concept of performativity was originally introduced by linguistic philosopher John L. Austin during a lecture series entitled How to Do Things with Words in 1955.Footnote 6 He suggested a basic differentiation between a constative and a performative utterance: While a constative utterance can only be true or false and is used to state something, performatives are neither true nor false, but can perform an action when being used (for example, ‘I hereby declare you husband and wife’). This idea was taken up, further discussed and reshaped within philosophy of language and linguistics.Footnote 7 Additionally, it was adopted in the cultural and social sciences, where it sparked the ‘performative turn’, and the power of performatives to create social realities was particularly discussed (for example, the couple actually being wedded after an authorized person has uttered the respective phrase in the correct context such as in a church or registry office). On its way through the disciplines, it was mixed or used interchangeably with the other two widely debated concepts of performance (as derived, for example, from cultural anthropology including game and ritual studies as e.g. conducted by Victor Turner) and Performanz (as discussed in generative grammatics e.g. by Noam Chomsky). In performance research as conducted by gender studies, performance studies or theatre studies scholars, the term performativity was not only referred to, but further politicized. A major question was (and still is) the relation between the (non-)autonomous individual and society, between free individual behaviour and the acting out of patterns according to (social) rules. Another major issue is the relationship between live and mediatized performances, as scholars such as Peggy Phelan,Footnote 8 Erika Fischer-LichteFootnote 9 or Phillip Auslander have emphasized.Footnote 10 The evanescence and ephemerality of live performances and the creation of an artistic space that was seen to be potentially free from underlying schemata of behaviour and their related politics (e.g. in art forms such as Happenings as opposed to art forms such as the bourgeois theatre of representation), were set in harsh opposition to recorded performances that were returned into an ‘economy of reproduction’.Footnote 11

When trying to understand games and music as performances, it is therefore necessary to state clearly which concept one is referring to. There are two options: Either one uses an existent concept as introduced by a specific scholar, or one needs to develop a subject-specific approach that is informed by the respective terminological history, and takes the entanglements with the other two concepts into account.

The goal of this chapter is to approach the three subject areas of ludomusicology from the perspective of performance studies using performance theory.Footnote 12

Analysing Games as Performances

The concept of ‘performance’ that we chose as our starting point has two basic dimensions of meaning. To illustrate these, a classic example from the field of music games is helpful: Guitar Hero. In this so-called rhythm-action game, that is played using a guitar-shaped peripheral,Footnote 13 the player is challenged to push coloured buttons and strum a plastic bar in time with the respectively coloured ‘notes’ represented on screen to score points and make the corresponding sound event audible. As Kiri Miller has observed, two basic playing styles have been adopted by regular players: ‘The score-oriented [players] treat these games as well-defined rule-bound systems, in which the main challenge and satisfaction lies in determining how to exploit the scoring mechanism to best advantage’.Footnote 14 On the other hand, she describes

Rock-oriented players [who] recognize that rock authenticity is performative. They generally do value their videogame high scores, but they also believe creative performance is its own reward. As they play these games, they explore the implications of their role as live performers of prerecorded songs.Footnote 15

This second playing style has particularly been highlighted in advertisements, in which we see ‘typical’ rock star behaviours such as making the ‘guitar face’,Footnote 16 or even smashing the guitar, thereby inviting potential players to ‘unleash your inner rock star’. Beyond hitting buttons to score points, these rock-oriented players are demonstrating further competencies: the knowledge of the cultural frame of rock music, and their ability to mimic rock-star-ish behaviours. As Miller highlights, ‘Members of both groups are generally performance-oriented, but they employ different performance-evaluation criteria’.Footnote 17

With the performance concept formulated by theorist Marvin Carlson we can specify what these different evaluation criteria are: ‘If we … ask what makes performing arts performative, I imagine the answer would somehow suggest that these arts require the physical presence of trained or skilled human beings whose demonstration of their skills is the performance.’Footnote 18 Carlson concludes that ‘[w]e have two rather different concepts of performance, one involving the display of skills, the other also involving display, but less of particular skills than of a recognized and culturally coded pattern of behavior’.Footnote 19 This can be applied to the two playing styles Miller has identified, with the former relating to Miller’s score-oriented players, and the latter to the rock-oriented players. Carlson further argues that performance can also be understood as a form of efficiency or competence (Leistung) that is evaluated ‘in light of some standard of achievement that may not itself be precisely articulated’.Footnote 20 It is not important whether there is an external audience present, because ‘all performance involves a consciousness of doubleness, through which the actual execution of an action is placed in mental comparison with a potential, an ideal, or a remembered original model of that action’.Footnote 21 In other words: someone has to make meaning of the performance, but it does not matter whether this someone is another person, or the performer themselves.

In summary, this dimension of performance in the sense of Leistung consists of three elements: firstly, a display of (playing) skills, that secondly happens within the frame and according to the behavioural rule sets of a referent (in our case musical) culture, and that, thirdly, someone has to make meaning out of, be it the performer themselves or an external audience.

Additionally, the term performance addresses the Aufführung, the aesthetic event. This understanding of performance as an evanescent, unique occurrence is a key concept in German Theaterwissenschaft.Footnote 22 At this point it is worthwhile noting that the debate on games and/as performances reveals linguistic tripwires: The English term ‘performance’ can be translated to both Leistung and Aufführung in German, which allows us to clearly separate these two dimensions. But due to the outlined focus of German Theaterwissenschaft, when used in the respective scholarly German-language discourse, the English word ‘performance’ usually refers to this understanding of Aufführung. As Erika Fischer-Lichte has described it:

The performance [in the sense of Aufführung, M. F.] obtains its artistic character – its aesthetics – not because of a work that it would create, but because of the event that takes place. Because in the performance, … there is a unique, unrepeatable, usually only partially influenceable and controllable constellation, during which something happens that can only occur once[.]Footnote 23

While offering a clear-cut definition, the focus on this dimension of performance in the German-language discourse has at the same time led to a tendency to neglect or even antagonize the dimension of Leistung (also because of the aforementioned politicization of the term). This concept of performance that was also championed by Phelan leads to a problem that has been hotly debated: If the Aufführung aspect of performance (as an aesthetic event) is potentially freed from the societal context, external structures and frames of interpretation – how can we make meaning out of it?

Therefore, ‘performance’ in our framework not only describes the moment of the unique event, but argues for a broader understanding that purposely includes both dimensions. The term connects the Aufführung with the dimension of Leistung by including the work and training (competence acquisition) of the individual that is necessary to, firstly, enable a repeatable mastery of one’s own body and all other involved material during the moment of a performance (Aufführung) and, secondly, make the performance meaningful, either in the role of an actor/performer or as a recipient/audience, or as both in one person. The same applies to the recipient, who has to become competent in perceiving, decoding and understanding the perceived performance in terms of the respective cultural contexts. Furthermore, a performance can leave traces by being described or recorded in the form of artefacts or documents, which again can be perceived and interpreted.Footnote 24

But how can we describe these two dimensions of performance (the aesthetic Aufführung and the systematic Leistung), when talking about digital games?

Dimensions of Game Performance: Leistung

In a comprehensive study of games from the perspective of competencies and media education, Christa Gebel, Michael Gurt and Ulrike Wagner distinguish between five competence and skill areas needed to successfully play a game:

2. social competence,

3. personality-related competence,

4. sensorimotor skills,

5. media competence.Footnote 25

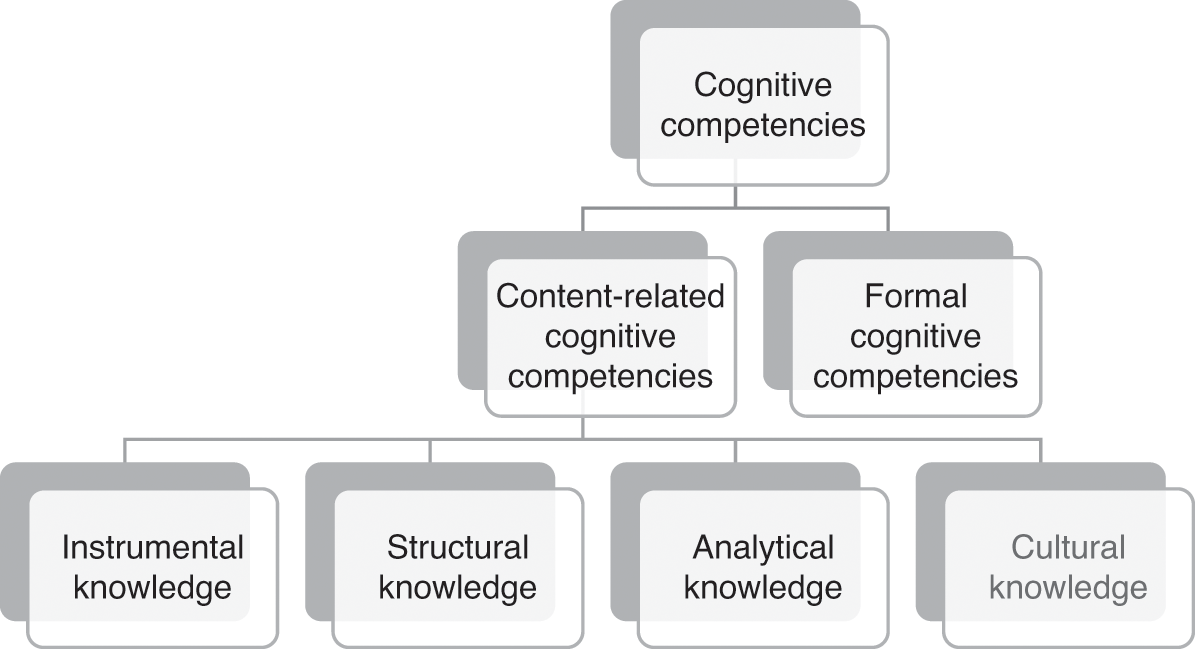

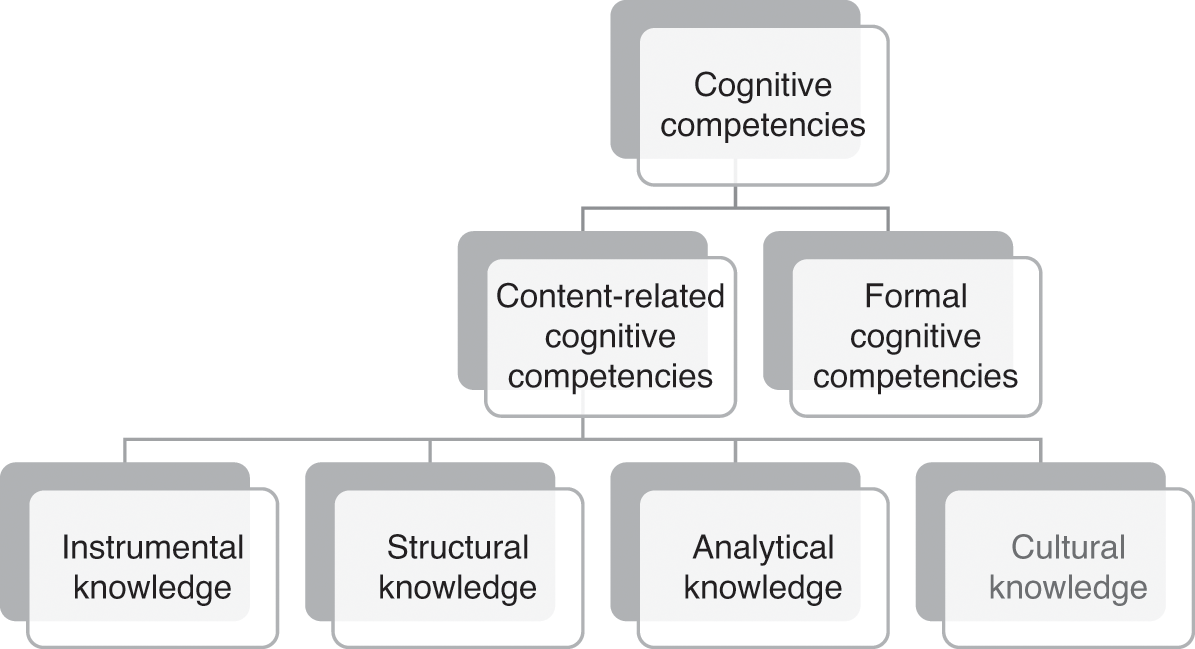

In this system, the area of cognitive competence comprises skills such as abstraction, drawing conclusions, understanding of structure, understanding of meaning, action planning and solving new tasks and problems, all of which can easily be identified in the process of playing Guitar Hero. In an article from 2010, Gebel further divides cognitive competence into formal cognitive and content-related cognitive competencies (Figure 14.1).Footnote 26

Figure 14.1 The area of cognitive competency following Gebel (2010)

Formal cognitive competencies include skills such as attention, concentration or the competence of framing (which in the case of Guitar Hero, for example, means understanding the difference between playing a real guitar and the game).

Content-related cognitive competencies concern using and expanding one’s existing game- and gaming-specific knowledge, and are further subdivided into areas of instrumental, analytical and structural knowledge. Instrumental knowledge includes skills such as learning, recognizing and applying control principles. In short, instrumental knowledge concerns the use of the technical apparatus. For example, that might involve dealing with complex menu structures.

Analytical and structural knowledge means, firstly, that players quickly recognize the specific features and requirements of a game genre and are able to adjust their actions to succeed in the game. For example, experienced music game players will immediately understand what they need to do in a game of this genre for successful play, and how UI (User Interface) and controls will most likely be organized.

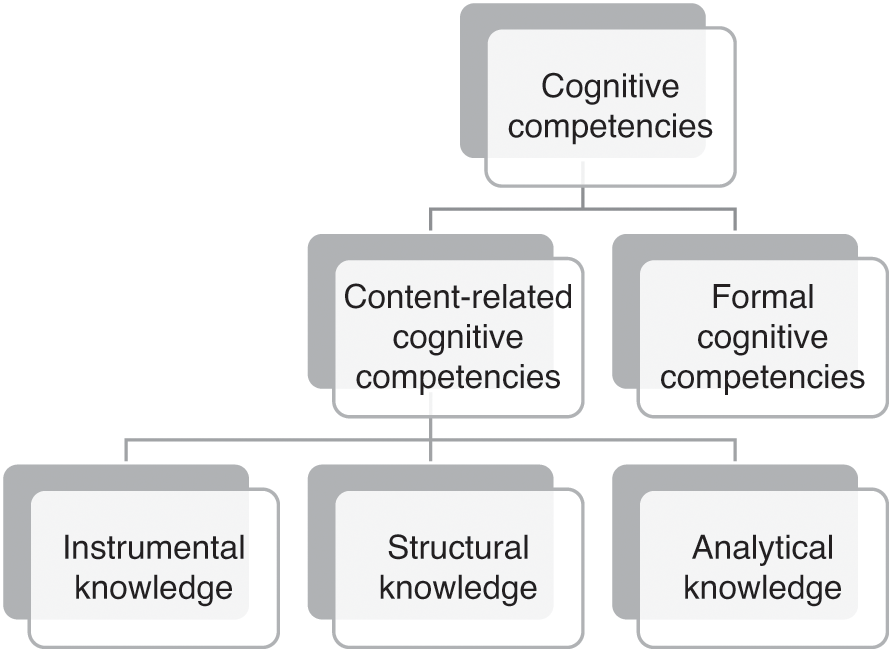

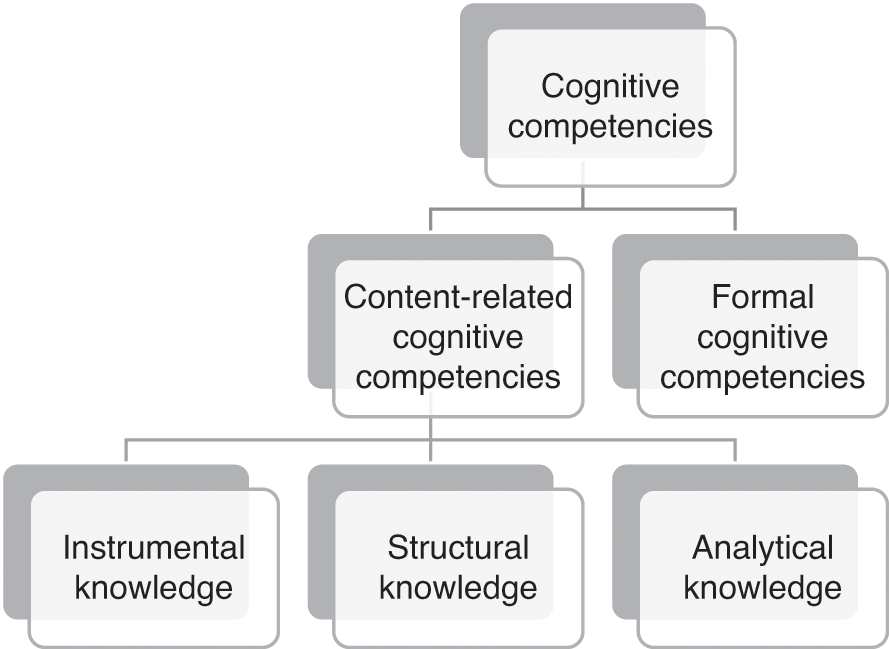

However, as we have seen in the Guitar Hero example, content-related cognitive competency does not only include game- and gaming-specific knowledge, but also knowledge from a wider cultural context (in our case rock music culture). This area of competence, the knowledge of the cultural contexts and practices to which a game refers or uses in any form, is not explicitly addressed in Gebel’s model, but can be vital for understanding a game. Therefore, we need to add such general cultural knowledge to the category of content-related cognitive skills (Figure 14.2).

The area of social competency includes social skills such as empathy, ambiguity tolerance or co-operation skills as well as moral judgement. This area is closely linked to personality-related competence, which includes self-observation, self-criticism/reflection, identity preservation and emotional self-control. Sensorimotor competence contains skills such as reaction speed and hand–eye co-ordination. The fifth area of competence relates to media literacy and explicitly addresses digital games as a digital medium. This comprises the components of media-specific knowledge, autonomous action, active communication and media design.

Regarding this last aspect, considerations from the discourse on game literacy particularly help to understand the different roles players adopt during gameplay.Footnote 27 In this context, we have already stated that players can adopt either the role of an actor/performer or that of a recipient/audience of a game, or even both at the same time (Carlson’s double consciousness). In the case of Guitar Hero, players can watch each other play or do without any external audience at all. When playing alone at home, they can make meaning out of their performances themselves by placing the actual performance in mental comparison with their idea of the ‘guitar hero’ as a model.

But players do not always play given games as intended by the designers.Footnote 28 In fact, oftentimes they either try to find out what is possible in the game, or even look for ways in which to break the rules and do something completely different than the intended manner of playing. In Ultima IX, for example, players found out that the game allowed for building bridges using material such as bread, corpses or brooms. Subsequently, some of them started bridge-building competitions, thereby playfully (mis)using the technology and the given game as the material basis for staging their own gameplay performances by following their own rule set.Footnote 29 Eric Zimmerman addresses such practices when he includes ‘the ability to understand and create specific kinds of meaning’ in his concept of gaming literacy.Footnote 30 From his point of view, players must be literate on three levels: systems, play and design, because ‘play is far more than just play within a structure. Play can play with structures. … [B]eing literate in play means being playful – having a ludic attitude that sees the world’s structures as opportunities for playful engagement’.Footnote 31 He emphasizes that he explicitly names his concept gaming literacy

because of the mischievous double-meaning of “gaming”, which can signify exploiting or taking clever advantage of something. Gaming a system means finding hidden shortcuts and cheats, and bending and modifying rules in order to move through the system more efficiently – perhaps to misbehave, but perhaps to change that system for the better.Footnote 32

Hence, gaming literacy includes the competencies and knowledge to playfully explore and squeeze everything out of a given structure, be it successfully finishing a game by playing it as intended, or by exploiting emergent behaviour such as the creative use of bugs or other types of uncommon play to create one’s own game. It further entails breaking the system, and making creative use of singular components, for example by hacking. That way, players can become designers themselves. But in order to do so, it is necessary to be competent regarding design. In his reasoning, Zimmerman relies on his and Katie Salen’s definition of design as ‘the process by which a designer creates a context to be encountered by a participant, from which meaning emerges’.Footnote 33 A designer might be one single person or a group, such as a professional design team, or in the case of folk or fan cultural gaming practices, ‘culture at large’.Footnote 34 That way, players do not just inhabit the traditional roles of performer and/or audience, but can even themselves become designers of new contexts, ‘from which meaning emerges’ by playing with the given material. But this play does not occur randomly. Instead, the emerging participatory practices happen within the frames of players’ own cultural contexts according to the specific rule systems that are negotiated by the practitioners themselves. Breaking the rules of such a practice could, at worst, lead to dismissal by this expert audience, as I have outlined elsewhere.Footnote 35 For example, when writing a fan song about a game, it is important to have reasonably good musical skills (regarding composing, writing lyrics and performing the song), and technological skills (knowing how to create a decent recording and posting it online), but also to be literate both in the game’s lore and its respective fan culture as well as in gaming culture in general, which can for example be demonstrated by including witty references or puns in the music or the lyrics.Footnote 36 A similarly competent audience on video platforms such as YouTube will most certainly give feedback and evaluate the performance regarding all these skills.

With this framework, the dimension of Leistung can be helpfully broken down into different areas of competence. In particular, the complex area of cognitive competencies and knowledge can be structured for analysis by helping to identify and address specific skill sets.

Dimensions of Game Performance: Aufführung

As game designer Jesse Schell has stated, ‘[t]he game is not the experience. The game enables the experience, but it is not the experience’.Footnote 37 On a phenomenological level, a game (be it digital or otherwise) only manifests itself during the current act of play, the unique event, as a unique ephemeral structure (the Aufführung) that can be perceived and interpreted by a competent recipient. Considering games in play as a gestalt phenomenon against the backdrop of gestalt theory may be helpful.Footnote 38 A useful concept that applies gestalt theory for a subject-specific description of this structure can be found in Craig Lindley’s concept of a gameplay gestalt: ‘[I]t is a particular way of thinking about the game state, together with a pattern of perceptual, cognitive, and motor operations. … [T]he gestalt is more of an interaction pattern involving both the in-game and out-of-game being of the player’.Footnote 39 So, a gameplay gestalt is one founded on a process, centred on

the act of playing a game as performative activity based on the game as an object. On the part of the players, any information given by the game that is relevant for playing on the level of rules as well as on the level of narrative, need interpretation, before carrying out the appropriate bodily (re)action,Footnote 40

thereby bringing the gestalt into existence and enabling the experience. But how can we describe experiences beyond personal impressions?

Regarding the aesthetic dimension of Aufführung, a slightly adjusted version of Steve Swink’s concept of game feel can be made fruitful. He defines game feel as ‘Real-time control of virtual objects in a simulated space, with interactions emphasized by polish’.Footnote 41 He emphasizes that playing a game allows for five different experiences:

The aesthetic sensation of control,

The pleasure of learning, practising and mastering a skill,

Extension of the senses,

Extension of identity,

Interaction with a unique physical reality within the game.Footnote 42

In other words, game feel highlights aspects of embodiment and describes the current bodily and sensual experience of the player as a co-creator of the Aufführung (in the sense of Fischer-Lichte). Therefore, the concept can be used to describe the aesthetic experience of performing (aufführen) during the actual execution (ausführen) offered by the game as a concept of possibilities. Taking up the example of Guitar Hero: Players learn to handle the plastic guitar to expertly score points (the pleasure of learning, practising and mastering a skill), thereby controlling the musical output (the aesthetic sensation of control) and incorporating the guitar-shaped controller into their body scheme (extension of the senses). When playing the game, they do not just press buttons to score points, but also perform the ‘rock star fantasy’, embodying the guitar hero (extension of identity). This works in any case: No matter which playing style players choose regarding the dimension of Leistung, during the performance in the sense of Aufführung both can be matched with the ‘guitar hero’ as a cultural pattern of behaviour – the button-mashing virtuoso or the rocking-out show person. Even the practising mode is tied to the rock star fantasy, when players struggle through the journey from garage band to stadium-filling act by acquiring necessary playing skills (the pleasure of learning, practising and mastering a skill). In other words, during every possible performance of the game (including practising) the emergent music-based gameplay gestaltFootnote 43 is in all cases tied to the promised subjective experience project of ‘unleash[ing] your inner rock star’, and is in this way charged with meaning. Even an ironic, exaggerated approach can work in this case, as this is also an accepted pattern in rock and heavy metal culture as comedy bands such as JBO or Tenacious D demonstrate.

In summary: Regarding digital game playing as performance, the dimension of Aufführung can helpfully be addressed with Swink’s concept of game feel, and broken down for description into his five experiential categories. It further becomes clear that the dimensions of Leistung and Aufführung are interlocked. The respective competencies and skill sets need to be acquired for the competent creation and understanding of an aesthetically pleasing gameplay gestalt.

As it is the goal of this chapter to introduce my basic ludomusicological framework that studies both games and music as playful performative practices, we need to address the two dimensions of performance regarding music in the next step.

Music as Performance: Leistung

As we have seen, for the analysis of a game such as Guitar Hero, a broader understanding of music beyond that of a written textual work is vital. In this context, the theorization about music as performance as conducted by researchers such as Nicholas Cook,Footnote 44 Christopher Small,Footnote 45 Carolyn AbbateFootnote 46 and others comes to mind. In this discourse the idea of music being a performative art form and a social practice is emphasized. But how should this be described in analysis?

In his book Markenmusik, Stefan Strötgen proposes a terminological framework that approaches music as a sounding but also as a socio-cultural phenomenon.Footnote 47 The basis for his argument is a five-tier model by music-semiotician Gino Stefani responding to the question ‘in what ways does our culture produce sense with music?’Footnote 48 Stefani differentiates between the general codes (the psychoacoustic principles of auditory perception), and in a second step, the social practices on which basis ‘musical techniques’ are developed as organizational principles for sounds. Strötgen summarizes that with ‘social practices’ Stefani describes a ‘network of sense’ on which ‘the relationships between music and society or, rather, between the various social practices of a culture’ are built.Footnote 49 He further concretizes Stefani’s model: Different musical styles do not just sound different. Music also becomes meaningful through its use in society by linking it with other content such as pictorial worlds, shared ideas about the philosophy behind it, performer and fan behaviours, body images, or social rule sets regarding who is ‘allowed’ to perform which music in what context and so on, thus becoming part of a social network of meaning. These meanings have to be learned and are not inherent in the music itself as text or aural event. These three factors (general codes, social practices, musical techniques) then provide the basis for the emergence of ‘styles’, and in the end of a concrete-sounding ‘opus’ performed by competent performers and understood by competent recipients.Footnote 50

At this point, one aspect needs to be highlighted that we have addressed regarding performance theory in general and that is also vital for the debate on music as performance: the politics of (musical) play and reception. This aspect is a core facet of Small’s concept of musicking:

A theory of musicking, like the act itself, is not just an affair for intellectuals and ‘cultured’ people but an important component of our understanding of ourselves and of our relationships with other people and the other creatures with which we share our planet. It is a political matter in the widest sense. If everyone is born musical, then everyone’s musical experience is valid.Footnote 51

Musicking, defined as taking part ‘in any capacity, in a musical performance, whether by performing, by listening, by rehearsing or practising, by providing material for performance (what is called composing), or by dancing’Footnote 52 demands a radical de-hierarchization of musical participation not only in terms of performers, but also in terms of recipients and designers. As Abbate and Strötgen also stress, audiences contribute their own meanings and interpretive paths when attending a musical performance. Subsequently, not only is everyone allowed to musick, but everyone is also allowed to talk about it and step into the role of designer by contributing in whatever capacity to the social discourse, for example, around a certain piece and how it has to be performed. Musicking means moving away from the idea of the one correct meaning that a composer has laid down in the musical text, which a passive recipient understands either correctly or not at all. This aspect of musical participation and music as a (recorded) commodity is also discussed by Cook and Abbate. According to Cook, a constant social (and therefore political) renegotiation of what, for example, a string quartet is supposed to be, which instruments are allowed in it, how to talk about it, how a specific one is to be performed and so on is the very core of how music-related social practices are established.Footnote 53 But similar to social practices, when and where we have the right to musick and play games is constantly being renegotiated against the backdrop of the respective cultural discourses.Footnote 54 Regarding music and the right to play it and play with it, we have seen this prominently in the sometimes harsh debates around Guitar Hero, when musicians such as Jack White or Jimmy Page strongly opposed such games and advocated ‘kids’ learning to play a real guitar instead of playing the game. Looking at the social practices of rock and its discourses of authenticity and liveness, it is quite obvious why they rejected the game: They accused game players of finagling an experience (‘Unleash your inner rock star’) they have no right to experience, since they have avoided the years of blood, sweat and tears of learning to play a real guitar.Footnote 55

Music as Performance: Aufführung

Regarding the dimension of Aufführung, the aesthetic dimension, again the game feel concept as explained above comes in handy. In her seminal text Carolyn Abbate makes the case for a ‘drastic musicology’ that also includes personal experiences, as well as bodily and sensual experiences that occur during performances.Footnote 56 In our context, Abbate’s example, in which she describes her experience of playing ‘Non temer, amato bene’ from Mozart’s Idomeneo at the very moment of performance is quite interesting: ‘doing this really fast is fun’ is not just a description of her momentarily playing experience, but also refers to the fact that she has acquired the necessary skills firstly, to play this piece of music at all and secondly, to play it fast.Footnote 57 This points to the fact that both dimensions of performance are not only linked in terms of knowledge but also in terms of embodiment. In other words: In order to play a piece of music or, more generally speaking, create a musical performance, not only the acquisition of the respective knowledge is required, but equally the above-mentioned sensorimotoric and other playing competencies in order to create a satisfying Aufführung in the form of a coherent gestalt, the sounding ‘opus’. Her description of musical movement with ‘here comes a big jump’Footnote 58 also follows this logic: on the one hand, she hereby refers to an option in the written work understood as a concept of possibilities that allows for this moment, which she can anticipate and master (the aesthetic sensation of control) thanks to her already acquired skills and knowledge (the pleasure of learning, practising and mastering a skill). On the other hand, she also describes her playing experience regarding the dimension of aesthetics using a metaphor of embodiment (extension of identity).

Table 14.1 summarizes the terminological framework we have developed so far, both for games and music understood as playful performative practices.

Table 14.1 Overview of the ludomusicological framework

| Competence (Leistung) | Presentation (Aufführung) |

|---|---|

| Slightly modified game-feel-model, after Steve Swinkb |

| = the aesthetic experience of performing (aufführen) during the execution (ausführen) Offered by the game as concept of possibilities; it highlights the aspect of embodiment and describes the current bodily and sensual experience of the player as a co-creator of the performance (in the sense of Aufführung, after Fischer-Lichte)d |

|

|

a Gebel, Gurt and Wagner, Kompetenzförderliche Potenziale populärer Computerspiele.

b Swink, Game Feel.

c Gebel ‘Kompetenz Erspielen – Kompetent Spielen?’

d Fischer-Lichte, Ästhetik des Performativen.

e Zagal, Ludoliteracy and Zimmerman, ‘Gaming Literacy.’

With the Guitar Hero example, we have already seen how this model can be usefully applied when studying music games. But what about the other two areas of ludomusicology, namely music as a design element in games, and game music beyond games?

Music as a Design Element in Games: Super Mario Bros.

Super Mario Bros. (1985) is one of the best-selling games of all time and started a long-running franchise that have been sold and played worldwide. Further, the title has been extensively studied in ludomusicological writing.Footnote 59 The game was designed under the lead of Shigeru Miyamoto and was distributed in a bundle with the Nintendo Entertainment System in North America and Europe, making it one of the first game experiences many players had on this console.

The staging of Super Mario Bros. is not intended to be realistic, neither in terms of its visual design, presenting a colourful comic-styled 8-bit diegetic environment, nor in terms of what the player can do. As I have stated before,

I describe the performative space in which all actions induced by the game take place, including those in front of the screen, as the gameworld. In this gameworld, the game’s narrative, the specific and unique sequence of fictional and non-fictional events happening while playing the game, unfolds. In order to address the world, which can be seen on screen, and set this apart from the gameworld, I will henceforth refer to this as the diegetic environment. I use the term diegesis here in the sense of Genette: ‘diegesis is not the story, but the universe in which it takes place’[.]Footnote 60

Super Mario Bros.’ diegetic environment presents the player with manifold challenges such as abysses, multifarious enemies, moving platforms and other traps and obstacles. In the words of Swink,

In general, the creatures and objects represented have very little grounding in meaning or reality. Their meaning is conveyed by their functionality in the game, which is to present danger and to dominate areas of space. … [W]e’re not grounded in expectations about how these things should behave.Footnote 61

The game does not offer an introduction or a tutorial, but gameplay starts immediately. That way, players have to understand the specific rules of the abstract diegetic environment, and either already possess or acquire all the necessary cognitive competencies and instrumental knowledge required to master all challenges. The avatar Mario also possesses specific features, such as his three states (Mario, Super Mario, Fire Mario) or the ability to execute high and wide jumps, which never change through the entire game. Regarding the dimension of Leistung, in addition to developing sensorimotor skills such as reaction speed and hand–eye co-ordination, learning and applying a whole range of cognitive skills and game-related knowledge is therefore necessary to successfully master the game. Formal cognitive (for example, attention, concentration, memory) and personality-related skills (coping with frustration and emotional self-control) are vital. The experience offered during the Aufführung while manoeuvring Mario through the diegetic environment featuring its own rules (interacting with a unique physical reality within the game) can be understood as the player discovering and mastering challenges by increasing not the avatar’s skill set, but their own playing skills (the pleasure of learning, practising and mastering a skill). This is done through embodiment by getting a feel for Mario (extending the player’s own identity) and the surrounding world (extending their senses). For example, as Steve Swink notes, ‘Super Mario Brothers has something resembling a simulation of physical forces … there are in fact stored values for acceleration, velocity and position. … If Mario’s running forward and suddenly I stop touching the controller, Mario will slide gently to a halt’.Footnote 62 A skilled player who has mastered the controls (experiencing the aesthetic sensation of control) and developed a feel for Mario’s movements (extending the player’s identity), can make use of this, for example by running towards a low-hanging block, ducking and gently sliding under it, thereby getting to places that are normally only accessible with a small Mario.

But how do music and gameplay come together? Composer Koji Kondo created six basic pieces for the game, namely the Overworld, Underworld, Starman and Castle themes, the Underwater Waltz and the ending theme. As detailed musicological analyses and explanations of the technological preconditions and subsequent choices can be found elsewhere, as noted above, I will confine myself here to highlighting how the music and sound effects are perfectly designed to create a coherent gameplay gestalt.

In an interview Kondo explains that, based on the specifications initially communicated to him, the Underwater Waltz was the first melody he wrote for the game, since it was easy for him to imagine how underwater music must sound.Footnote 63 This indicates that for certain representations on the visual level such as water, swimming and weightlessness, cultural ideas exist on how these should be underscored, namely in the form of a waltz. Kondo further states that a first version of the Overworld theme that he had also written on the basis of the specifications did not work (which were formulated: ‘Above ground, Western-sounding, percussion and a sound like a whip’). He describes that he had tried to underscore the visual appearance of the game, namely the light blue skies and the green bushes. But when Kondo played the prototype, the melody did not fit Mario’s jumping and running movements, therefore it felt wrong. As players have only a specific amount of time to succeed in a level, the music as well as the level design encourage them to not play carefully, but rather to adopt a ‘Fortune Favours the Bold’Footnote 64 playing style. Kondo’s second approach, now based on the actual embodied experience of gameplay, reflected this very game feel. As Schartmann puts it:

Instead of using music to incite a particular emotional response (e. g., using faster notes to increase tension), he tried to anticipate the physical experience of the gamer based on the rhythm and movement of gameplay. … In essence, if music does not reflect the rhythm of the game, and, by extension, that of the gamer, it becomes background music.Footnote 65

That way, the distinct laws and rhythms of the diegetic world, and the way in which the player should move Mario through them using their own learned skills and the subsequent ‘extension of the senses’ are both acoustically transported by the music and by the sound effects, also by using techniques such as movement analogy, better known as Mickey-Mousing (the ‘ka-ching’ of the coins, the uprising jumping sound, the booming sound of Bullet Bills etc.). In addition to game-specific competencies, general cultural knowledge from other media types, namely cartoons and movies regarding the logic of how these are underscored, help to develop a quick understanding of the inner workings of the abstract world presented on screen.

Kondo conceptualized the soundtrack in close connection with the game feel evoked by the game performance, understood as the player’s sensual and physical experience as they follow the intended scheme of play that is encouraged by the level design. The game’s music sounds for as long as the player performs the game, which is determined by their skill level (unskilled players may have to restart many times over) and by their actions. The sounding musical performance is therefore directed by their gameplay and their (game-) playing skills. Playing Super Mario Bros. can be understood as a musical performance; firstly, when understood in terms of Leistung, the generation of this performance requires not only knowledge but also the physical skills needed to play the game at all; and secondly, it requires the ability to adopt the intended speed and playing style encouraged by the level design, play time limit and music.Footnote 66 All elements of the staging (gameplay, diegetic world, level design, music, etc.) are from a functionalist point of view designed to support game feel in the sense of an interlocking of both dimensions of performance, so that a coherent gameplay gestalt can be created during the current act of play, which involves the player in the gameworld as defined above. The player constantly shifts between the role of performer and that of recipient and continuously develops their respective skills in the course of the game’s performance.

Music Beyond Games: Chip Music as a ‘Gaming-a-System’ Practice

Since the late 1970s, game sounds and music have found an audience outside the games themselves. They can be heard in TV shows, commercials, films and other musical genres. In Japan the first original soundtrack album of Namco titles was released in 1984, and the first dedicated label for chip music – G.M.O. Records, as an imprint of Alfa Records – was founded in 1986.Footnote 67

As explained in the introduction to Part I of this book, thanks to the coming of affordable home computers and video game systems, a participatory music culture emerged at the same time. Instead of simply playing computer games, groups banded together to remove the copy protection of commercial titles. Successfully ‘cracked’ games were put into circulation within the scene and marked by the respective cracker group with an intro so that everyone knew who had cracked the title first. Due to the playful competition behind this, the intros became more and more complex and the groups invented programming tricks to push the existing hardware beyond its boundaries. As Anders Carlsson describes:

Just as a theatre director can play with the rules of what theatre is supposed to be, the demosceners and chip music composers found ways to work beyond technological boundaries thought to be unbreakable. … These tricks were not rational mathematical programming, but rather trial and error based on in-depth knowledge of the computer used. Demosceners managed to accomplish things not intended by the designers of the computers.Footnote 68

In addition to the idea of competition, an additional goal can be described as an independent accumulation of knowledge and competencies through playful exploration and ‘gaming a system’ in the sense of Zimmerman, but according to a specific rule set as negotiated in the community. The goal of this self-invented meta-game with the personal goal of ‘technology mastery’ (the pleasure of learning and mastering a skill, seamlessly merging in an aesthetic sensation of control) is an optimization of the staging – in the sense of an exhibition – of skills during the actual performance of the songs. These skills include knowing the specific sound characteristics and technological features of the respective sound chip, as well as optimizing and generating sounds that had been thought to be impossible. The finished composition and concrete opus sounds as a musical performance when the practitioner plays their work themselves or when someone else performs their composition based on the staging of the technical apparatus (that is the computer technology). Such a media-mediated music performance can in turn be evaluated accordingly by a competent recipient, savvy in the evaluation rules negotiated in the chip music scene. Aesthetic notions relate not only to the composition and the sounding opus, but also to the elegance or extravagance of the staging, that is, the use of hardware and software. Further, practitioners constantly renegotiate how a well-made artefact is to be created, which affordances it must fulfil, how it should be judged and so on.

Additionally, demosceners and chip musicians do not keep the knowledge they have gained through ‘gaming a system’ to themselves, but share their insights with the community, for example by publishing their programming routines, or self-created accessible software such as Hülsbeck’s Soundmonitor or the Soundtracker 2, a hacked, improved and freely distributed version of Karsten Obarski’s Soundtracker, created by the Dutch hacker Exterminator.Footnote 69 As the songs produced with these trackers were saved in the MOD format, they are effectively open books for competent users, as Anders Carlsson describes:

[I]t was possible to look into the memory to see how the songs worked in terms of the routine that defines how to access the sound chip, and the key was to tweak the chip to its fullest. … [I]t was possible for users to access the player routines, along with instruments, note data, effects and samples. Even though these elements could be hidden with various techniques, there would usually be a way to hack into the code[.] As long as a user has the tracker that was used for making the song, it is possible to load the song into an editor and gain total control of the song.Footnote 70

By creating and openly sharing their tools and knowledge, chip musicians actively practised the democratization of musical participation advocated by Small. The resulting music performances were also shared within the community, were increasingly made available free of charge via the Internet and were made available to others for use or further processing, thereby undermining the idea of music as a commodity to be paid for. ‘Gaming a system’ therefore does not only take place in relation to the hard- and software, but also avoids the usual distribution and performance rules of Western music, thereby creating new genres and giving musicians access to musical production that they would otherwise have been denied, and allowing everyone to musick. As for example Bizzy B., ‘godfather of breakbeat hardcore and drum ‘n’ bass, responsible for overseeing hardcore’s transition into jungle’ (as he is described by the interviewer Mat Ombler) explains in an interview about the role of the Amiga and the tracker OctaMED, written by Teijo Kinnunen:

It allowed me to have a doorway into the music business. … I wouldn’t have been able to afford the money for a recording studio; I wouldn’t have been able to practice music production and take my music to the next level if it wasn’t for the Commodore Amiga.Footnote 71

Since the early days, the community has diversified into what Leonard J. Paul calls the ‘old school’ and the ‘new school’.Footnote 72 Whereas the old school practitioners focus on using the original systems or instruments to create their performances, the new school evolved with the new technological possibilities of 1990s personal computers, as well as the trackers and other tools developed by the scene itself, and is interested in on-stage performances which include the performers themselves being on the stage. They further explore new hybrid forms by combining the chip sound – which does not have to be created with the original systems; instead new synthesizers are used – with other instruments,Footnote 73 thereby gaming a third system by freely combining the systems of different musical genres.

Chip musicians invented their own meta-game with the goal of creating music performances with the given materials. Participation is only restricted in that they must have access to the respective technology and must be literate, firstly in using the technology and secondly in the socially negotiated rules of the meta-game; this demands all five above-mentioned areas of competence outlined by Gebel, Gurt and Wagner,Footnote 74 and the acquisition of these respective skills to create chip music performances. Over time, these rules have changed, and the new school have developed their own social practices and rules for ‘gaming a system’.

Conclusions

Using this terminological framework, we can respectively describe and analyse the design-based use of music as an element of staging, and the resulting relationship between players, music and game, in the context of play on the two dimensions of performance. It further enables a differentiated distinction between the performance dimensions of Leistung and Aufführung, as well as a differentiation between music- and game-specific competencies regarding the Leistung dimension. Understood as forms of performance, both music and games can also be addressed as social acts, and aspects of embodiment can be taken into account thanks to the adapted game feel concept. Used in addition to other approaches introduced in this book, this framework can help to describe specific relationships and highlight aspects of these in order to further our understanding of games and music.