Introduction

Video games have frequently been associated with newness, the present or even the future. Despite this, they have long had a close and creative relationship with history. While many early games dealt with ahistorical topics such as digital versions of already-extant analogue games (billiards, chess, tennis or ping-pong) or futuristic ideas such as Spacewar! (1962), it was not long before games began to deal with history. Hamurabi (1968), for example, was one of the earliest strategy games, in which, through a text-based interface, the player acted as the ancient Babylonian king Hammurabi (c.1810–c.1750 bc) in the management of their kingdom.

Whether set in ‘real’ historical situations or imagined worlds motivated and animated by a shared understanding of history, games have long drawn on the past as a source of inspiration and continue to do so today. This essay is concerned not just with history but with music and history. I therefore mean to touch briefly on various ways in which music history and games interact. Though far from an exhaustive treatment of the topic, these case studies may stand as staging points for further investigations. In the main, they demonstrate the mutual interactions between representations of history in games and other media, showing both intermedial shared aspects, and those seemingly unique to, or at least originating in games.

Intermedial Trends and Game Technology

The use of historical music to underscore historical topics is not a phenomenon particular to games. Long before the advent of video games, it had already found full vent in the world of film from at least as early as Miklós Rósza’s score for Ivanhoe (1952), for which he professed to have ‘gone back to mediaeval music sources’ and his earlier score for Quo Vadis (1951) which drew on the Ancient Greek Epitaph of Seiklos.Footnote 1

The relationship, in historically situated film, of ‘historical music’ to ‘real’ or ‘authentic’ music history (to risk wading into a debate best left to a different essay) is complex.Footnote 2 History is not something discovered, but something made. It is a ‘site from which new narratives spring, conditioned and coloured by the perspectives and technologies of the age’.Footnote 3 What is considered an ‘authentic’ musical expression of a time period changes through time and cultural context, and is impacted upon by technological constraints and opportunities. We must be mindful too of the popular conception of history, which is often coloured by trends in and across genres, rather than necessarily springing from the minds of our best historians and musicologists.

Though this relationship is complex in film it is perhaps further problematized in video games. The capabilities of the technology involved in the latter act as both constraining and motivating forces for the composition of music in a manner which is often considered unique to the medium. This uniqueness is, I would argue, largely illusory however: the very fact of non-diegetic music’s ubiquitous deployment in film is, of course, predicated on an analogous artistic response to the technological constraints of silent-era films.Footnote 4 In both media, we grapple with the aesthetic legacies of earlier technological constraints, even though the constraints themselves no longer apply.

Though the very presence of a film score is clearly predicated on technological development, it is still arguable that changes in technology have had a more obvious impact on video games than film in recent years, through the number and kinds of sounds that have become available to composers. We will return to this point later in the essay. While some compositional trends may have evolved from technological concerns inherent to games, many historical tropes in games come from those already prevalent in film music. Something that is less frequently discussed is the degree to which this influence seems to have been mutual.

Video game music has a complex and multifaceted relationship with the sounds of history, borrowing from and lending to our shared, intermedial popular conceptions of the past built through decades of common gestures, drawing upon historical and musicological research, and filtering all of this through the limitations and opportunities offered by the technology of the time.

Tropes from Film into Game

Perhaps the most obvious broad trope to move from film and other media into game is medievalism. Medievalism is essentially the creative afterlife of the middle ages. It does not therefore mean ‘real’ medieval music, but musics from other historical periods that are understood ‘as medieval’ in popular culture (from baroque, to folk, to heavy metal), and newly composed works that draw on readily understood symbols of the medieval. It is one of the primary animating forces behind fantasy, and has a rich history in its own right.Footnote 5

In film, medievalism plays out as a variety of tropes, both visual and sonic. I wish to focus here particularly on ‘Celtic’ medievalism. In essence, it draws on aspects of Celtic and Northern (i.e. Northern European and especially Scandinavian) culture, which are held as a shorthand for a particular representation of the middle ages. Examples include Robin Hood (2010), which makes use of the Irish song ‘Mná na hÉireann’ (composed by the twentieth-century composer Seán Ó Riada to an eighteenth-century text) to underscore a scene set in medieval Nottingham; or the How to Train Your Dragon series (2010–2019), which displays a mixture of Celtic and Viking imagery, alongside Celtic-style music to represent an imaginary, yet clearly Northern setting.Footnote 6

On screen, a clear Celtic/Northern medievalist aesthetic is often vital to narrative and scene-setting. It often signals a kind of rough-hewn but honest, democratic, community-based society, with elements of nostalgia, as well as a closeness to nature. Writers such as Gael Baudino and Patricia Kennealy-Morrison often draw on pagan Celtic sources as an alternative to what they perceive as the medieval Christian degradation of women,Footnote 7 and this association with relative freedom for women is often borne out in other Celtic medievalist representations.

An example of medievalism in games is The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt (2015), which combines several distinct medievalisms to characterize each of the areas of the gameworld, as I have noted elsewhere.Footnote 8 I will focus on two contrasting examples here. One of the clearest is in the region called Skellige, a Hebridean-type archipelago, which oozes Celtic/Northern medievalism. This is manifest in the presence of Viking longboats, longship burials and widow sacrifice,Footnote 9 as well as of tartans, clans and Irish accents.

Celtic/Northern medievalism is utterly vital to the narrative in Skellige; it helps us immediately to situate ourselves within a believable world, in which we expect and can understand the social interactions we observe. The associations with Celtic medievalism, paganism and freedom for women strongly apply to Skellige too. Unlike the rest of the game world, the dominant religion in the region is headed by the female priestesses of Freya; there are several female warriors in evidence and a woman may become the leader of the region, depending on player choices.

Sound and music are integral to the medievalism. The score borrows heavily from Celtic folk, using bagpipes and flutes and, in a nod to the association of Celtic medivalism with freedom for women, female voice. The cue ‘The Fields of Ard Skellig’, which acts as non-diegetic backing throughout open-world exploration of Skellige, can stand as exemplary. We have a Hardanger fiddle, a Norwegian folk instrument that is a clear sign of Northern medievalism in popular culture.Footnote 10 The Hardanger fiddle is used predominantly to support the vocals, which borrow the text from a Scots-Gaelic poem called ‘Fear a’ Bhàta’. Despite its eighteenth-century origins, it has clear Northern medievalist narrative potential here. Unintelligible or obscure text, be that Latin, faux-Latin, open vowel sounds, minority languages or even invented languages, has a long history in medievalist representation,Footnote 11 and the use of Gaelic in this song exploits this adroitly, while adding to the generally Celtic aesthetic. The vocal delivery is free, expressive and heavily ornamented, and supported by a harmonically static and modal arrangement.

These Celtic/Northern medievalist aspects contrast with the urban areas of the game, Oxenfurt and Novigrad. This contrast is redolent of an animating tension at the heart of many fantasy narratives: modernity vs premodernity, rationalism vs irrationality, pre-industrial vs industrial. Here, it helps differentiate the areas of the game. The cities of Oxenfurt and Novigrad are architecturally Early Modern. The famous university of Oxenfurt, with a coat of arms drawing on that of the University of Cambridge, and a name redolent of Oxford, adds an association with rationality that is often evoked in the dialogue of the non-player characters, or NPCs (who ask ‘what will you do when all the monsters are dead’, for instance). The sound world too plays on this contrast. The music is more frequently diegetic, the result of live performances by in-game Renaissance dance bands, rather than the non-diegetic sound of the environment as heard in Skellige. It is also more metrical, and focuses on hammered and plucked strings, as well as percussion.

Sonic representations of religion in the cities and Skellige are markedly different too. Unlike Skellige, Oxenfurt and Novigrad follow the Church of the Eternal Fire, which has clear parallels with aspects of medieval Christian history (with witch burnings etc.). Musically, its representation follows one of the clearest markers of sacred medievalism in introducing chanting male voices (which are unique at this point of the game) as the player approaches the Great Temple of the Eternal Fire.

In all, while the urban areas of the game still draw on popular medievalism, it is clearly one of a contrasting narrative power, enabling the game regions to feel linked but still distinct. There are a variety of medieval modes in play here, which provide shifting, varied images and all of which draw on associations built up in film and other media.

Technology and Tropes

One of the best examples of technology impacting on historical game music is manifest in the use of baroque counterpoint. As has been discussed elsewhere in this volume, the capabilities of games within the chiptune era created some interesting compositional challenges. Due to limitations in memory and available hardware,Footnote 12 composers devised novel approaches to composing both for a limited number of voices, and for non-equal temperament. As Kenneth B. McAlpine has noted, one approach was to borrow the baroque technique of implied pedal, rapidly alternating semiquavers between a moving note and repeated note. Some games, such as Fahrenheit 3000 (1984), would borrow pre-existent examples of this wholesale – in this case the opening to Bach’s famous Toccata and Fugue in D minor – while others, such as Ben Daglish’s Krakout (1987) composed new works making use of the same techniques to allow implied polyphony on a one-voice beeper.Footnote 13

There are obvious practical and aesthetic advantages to baroque allusion in slightly later games too. As William Gibbons has noted,Footnote 14 a console such as the NES was essentially capable of three voices, two upper parts (the square-wave channel) and one lower part (the triangle-wave channel).Footnote 15 This complicates attempts at explicitly Romantic or jazz harmony, which must be implied contrapuntally, rather than stated in explicit polyphony. It does lend itself to contrapuntal styles such as the baroque trio sonata or simple keyboard works, however. The ‘closed-off harmonic and melodic patterns’ and the ‘repeats inherent in [the] binary structures’ of these works are also very well suited to the demands of loop-based game scores which need to repeat relatively short sections of music several times.Footnote 16 Nonetheless, as Gibbons has shown, what may have once been simple technological expedience instead developed into a trend of dramatic and narrative power.

As Gibbons has noted, medieval castles and labyrinths were common in game design during the 1980s and 1990s, offering both a recognizable location and aesthetic common to many role-playing games of the time, and a logical game mechanic allowing for dungeons and towers to be conquered one at a time. Frequently, the musical backing for castles and labyrinths either exploited pre-existent baroque music or period pastiche. The associations between baroque music and grandeur may have been partly responsible for this choice of music; baroque architecture and baroque music are often linked in scholarship and in the popular imagination. Magnificent castles, such as Tantagel in Dragon Warrior/Dragon Quest (1986) for instance, often struggle to convey a sense of opulence within the limitations of their graphics. This is particularly the case for top-down views, which tend to elide tapestries, paintings, rugs, or furniture. The baroque aesthetic of the music here seeks to fill in the visual lacunae.

The links go deeper, however, drawing on popular medievalism. Gibbons has situated this use of baroque to underscore fantasy as part of a ‘complex intertextual – indeed intermedial – web of associations that connects video games with progressive rock and heavy metal, fantasy literature and films, and table-top role-playing games’;Footnote 17 all of these draw on medievalism. Many early fantasy games began as an attempt to translate the gameplay and aesthetics of Dungeons and Dragons (D&D) into video game form. They also frequently drew on the imagery of 1980s ‘sword-and-sorcery’ fantasy, such as the Conan series – often going so far as to model box art on analogous film imagery – and wove a healthy dose of Tolkien throughout all of this. These disparate strands are tied together through music. A number of progressive rock and heavy metal bands from the 1960s to the 1980s had very similar influences, drawing on Tolkien, D&D and the fantasy imagery of sword-and-sorcery films. They also drew heavily on baroque music alongside these influences, from allusions to Bach’s Air on a G String in Procol Harum’s ‘A Whiter Shade of Pale’ (1967), to following baroque-style ornamentation and harmonic patterns, as Robert Walser has argued.Footnote 18 That all these elements therefore combine in the fantasy medievalism of the NES-era console is unsurprising.

Tropes from Game Back into Film

So far, I have treated video games as a medium which translates influences from other media and filters them through certain technological constraints. But this does disservice to the important influences that the sound of video games seems to have had on other media, and particularly their representations or creative uses of the past. I wish to point to two specific examples. The first of these is an indirect product of the baroque contrapuntal nature of many early fantasy game soundtracks, as discussed above, which I hold at least partly responsible for the tendency, in recent years, to conflate all pre-classical music in popular historical film and television. In effect, baroque music comes to stand for the medieval and Renaissance. Though baroque may have mingled with medievalist fantasy in prog rock and metal, it was generally not something usually seen in filmic depictions of the medieval. More recent examples abound, however: the diegetic use of Zadok the Priest on the march to Rodrigo Borgia’s coronation as Pope Alexander Sextus in 1492 in The Borgias (2011), some 193 years before the birth of its composer,Footnote 19 or the non-diegetic use of Bach’s St Matthew Passion (1727) heard as the ceiling of a twelfth-century cathedral collapses in The Pillars of the Earth (2010), for instance. The advantages of using pre-existent baroque music over pre-existent medieval or Renaissance music is obvious. This music has a greater currency in popular culture; people are more likely to recognize it. This has obvious advantages for the idea of building ‘affiliating’ identifications,Footnote 20 which relies on the listener making intertextual connections. For the example of The Borgias, hearing Zadok the Priest has obvious connotations of a coronation – more chronologically appropriate music almost certainly would not have this same symbolic meaning to the vast majority of listeners. Baroque music is often more familiar than medieval and Renaissance music, which is not tonal, and is played on a variety of unusual instruments. Much very early music is so far outside of most listeners’ experience as to sound simply ‘other’, rather than necessarily early. Baroque music, however, is familiar to many – but still recognizably ‘early’. Nonetheless, despite the clear advantages for directors/producers/designers in using baroque music as part of a medieval or Renaissance sound world, it nonetheless does depend on a popular conception of history that collapses these time periods together, and this seems to be a direct consequence of the tendency for baroque music to be used in medievalist-themed games over the last thirty to forty years.Footnote 21

The second example is seemingly even more unique to a post-video-game world and, while not relating strictly to music, is still very much a part of the overall phenomenon of sonic medievalism. This particular trope is one that has remarkable currency across all visual fantasy media, namely the portrayal of dwarfs as Scottish. I have previously argued that the dialect and accent of voice actors is an extremely important aspect of sonic medievalism,Footnote 22 and that the tendency to represent the medieval period in particular with characteristically ‘Northern’ accents (Scotland, the North of England, Scandinavia) is related to the common trope of Northern medievalism. A great many films, televisions, books and video games draw on associated characteristics of this. Within this complex and shifting semantic area, the Scottishness of dwarfs seems remarkably fixed. Many will point to The Lord of the Rings (2001–2003) film franchise as the moment that the national identity of dwarfs was set in stone, but there is a far earlier game example: Warcraft II: Tides of Darkness (1995). Predating LOTR by six years, Warcraft II is clear that dwarfs are Scottish, and they remain so for subsequent iterations in the same game world. The game series Baldur’s Gate (1998–2016) continues this very same trend and it seems clear that video game dwarfs were recognizably Scottish long before the same trend was concretized in film. Some may argue that the subsequent choice of accent for LOTR is incidental and related to the natural accent of the character Gimli, who most prominently displays the accent at the start of the series. However, John Rhys-Davies, who plays Gimli, is Welsh, and the accent is therefore clearly a choice, supressing both the actor’s natural accent and the Received Pronunciation English accent that he often adopts for his acting work. While it is true that the same aspects of sonic medievalism may have independently influenced both the ludic and filmic approaches to voice acting, it seems more plausible that some influence was taken from game into film.

In all, while we can point to trends moving from historical TV and film into games, filtered through different technological concerns, it seems clear that some aspects have moved the other way too. The association of fantasy dwarfs and the Scottish accent seems good evidence of this, as does the currency of the baroque as a marker of the medieval which seems, in part, to have come about specifically through the technical limitations of certain games.

Representations of ‘Real’ History in Games

So far, I have discussed the creative use of history in fantasy games, but what of the representation of ‘real’ history in video games? To an extent, the distinction is arbitrary. At the start of this chapter, I argued that history is something that is creative, not reproductive, that there is an element of at least fiction, if not fantasy, in every historical work. Nonetheless, for all the somewhat porous boundaries, some games are, to greater or lesser extents, rooted in real history. An excellent example is the Civilization series (1991–present). Rather than presenting an historical story, this series instead allows the player to take control of a nation and to guide its historical development. History is an important part of the game nonetheless, with real historical figures, technological developments and buildings. Real historical music also plays an important role.

Karen Cook has focused attention on the Civilization IV soundtrack.Footnote 23 She notes that music here acts ‘to signify chronological motion and technological progress’ and that, while supporting an underlying American hegemonic ideology, it nonetheless allows the player to interact with this within a postmodern framework. Music forms only part of the soundtrack, and is always non-diegetic, cycling through a number of pre-composed pieces from the Western art music tradition, with the choice of piece depending on the level of advancement that the player has achieved. Before advancement to the Classical era (i.e. the era of Classical civilization, rather than ‘classical music’), there is no music in the soundtrack (though other sound effects are present), seemingly identifying the Classical period as being the first that is ‘technologically capable of, and culturally interested in, music making itself’.Footnote 24 Once the Classical era is entered, the score begins to contain music but, unlike all other eras of the game, it includes no pre-existent music, presumably due to the scarcity of surviving music from the Classical world, and its unfamiliarity to the majority of listeners. Instead, new music is composed which draws from ‘stereotypical sound-images of pan-African, Native America, or Aboriginal music’.Footnote 25 This is a far cry from descriptions of music from antiquity, and from the few surviving notated examples of it, but it draws on a pervasive sense of exoticism whereby music of the distant past is seen to be discernible in music of cultures geographically distant from Western civilization. This reinforces a major criticism of the game series, that Western civilization is seen as the natural culmination of progress.

The next game period – the Middle Ages – is the first to use pre-existent music, though almost none is medieval. The only medieval music is monophonic chant, which remains a part of the modern liturgy in many parts of the world, while the polyphonic music is entirely Renaissance, including works by Ockeghem and Sheppard. None of these Renaissance choices are included in the Renaissance era of the game, which instead uses music by Bach, Beethoven and Mozart. Again, we seem to have a sense of musical chronology collapsing in upon itself. The pre-medieval world is represented purely by newly composed music indebted to an exoticist colonialist historiography, the medieval by the sounds of Renaissance polyphony (presumably since medieval polyphony would have sounded too foreign and exotic) and music from later than this period is represented by a collection of predominantly Classical and Romantic composers, with a bit of baroque in the Renaissance. In all, this game showcases the fascinating degree to which music can historicize in the popular imagination in a manner not always indebted to temporal reality.

‘Real’ History and ‘Real’ Music History

For the remainder of this essay I wish to focus on an extraordinary musical moment that occurs in the Gods and Kings expansion of Civilization V (2012). As the player transitions from the set-up screen to the voice-over and loading screen at the start of the ‘Into the Renaissance’ scenario, the player is treated to a recomposition, by Geoff Knorr, of Guillaume de Machaut’s Messe de Nostre Dame, here titled ‘The medieval world’.

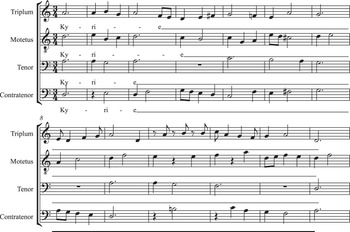

Machaut, a fourteenth-century French composer, is particularly revered for his polyphonic works. These pieces from the late Middle Ages represent important landmarks in European music history. His Messe de Nostre Dame is perhaps his most famous work, written in the early 1360s.Footnote 26

To the best of my knowledge, this is a unique instance of a piece of pre-existent medieval polyphony in a video game. The manner of its presentation is remarkably subtle and effective, altering the original medieval musical text to make it sound more medieval (to a popular audience). Situating this track at the opening of the ‘Into the Renaissance’ scenario is a remarkable nod to certain historiographical narratives: the Mass cycle was seen by Bukofzer as paradigmatic of the Renaissance, the perfect musical expression of its time.Footnote 27 Many see Machaut’s Mass, the very earliest surviving attempt by a composer to organize a full cycle of each movement of the Mass Ordinary, as the first steps on the path to the Renaissance Mass cycle. Situating Machaut’s Mass at the opening of this scenario, as representative of ‘the medieval world’ and its transition ‘into the Renaissance’ is therefore a deeply symbolic gesture.

The recomposition opens not with the start of Machaut’s Mass, but with a new choral opening (see Example 19.1, bb. 1–15). It deploys a male choir, singing Latin text – an important signal of sacred space in medievalist renderings.Footnote 28 This choir begins with an opening rising minor third gesture, but with the countertenor and tenor, and baritone and bass parts respectively paired at the fifth (bb. 1–2). This, combined with the triple metre, the clear Dorian modality and the supporting open-fifth drones, immediately situates us within a medievalist sound world. The paired open-fifth movement continues for much of the opening phrase, mirroring the early descriptions of improvised polyphonic decoration of chant from the Musica enchiriadis, in which parallel doubling of the melody forms the basis of the polyphony. To this is added a sprinkling of 4–3 suspensions (for example in b. 3) which add some harmonic colour, without dispelling the sense of medievalism. Bar 8 reaches a particularly striking moment in which accidentals are introduced for the first time and an extraordinary unprepared fourth leaps out of the texture. As with the opening, the voices are paired, but this time at a perfect fourth. This rejection of common-practice harmony is striking and gives an antiquated feeling to the harmony, even if it is also rather unlike Machaut’s own harmonic practice. The introduction of additional chromaticism is clearly a nod to the musica ficta of the medieval period too.Footnote 29

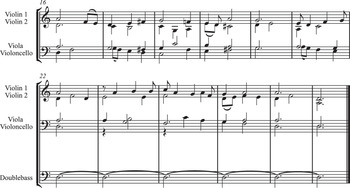

Example 19.1 ‘Into the Renaissance’ (excerpt), Civilization V: Gods and Kings, showing the adaptation of Machaut’s Messe de Nostre Dame

Despite the many changes, this opening is based on that of Machaut’s Mass (Example 19.2), which also opens with paired open-fifth Ds and As (bb. 1–2), though quickly departs from this parallelism. The striking moment at bar 8 of ‘The medieval world’ may be seen as an adaptation of bar 5 of Machaut’s Mass, where the first accidental is used – here too giving an F♯ against a B. In Machaut’s Mass, the contrapuntal context is clear – the B and F♯ are inverted, giving a perfect fifth, and the descending D to C figure in the bass (not found in the recomposition) clearly gives the context of a traditional cadence of this period. Knorr seemingly found this moment of Machaut’s Mass striking and wished to give it even greater prominence in his recomposition. In doing so, he has created something which sounds to most ears more authentically medieval than the medieval original. The final cadence of this section, with its strident G♯ and C♯ (Example 19.1, b. 12), is taken directly from the cadence at the end of the first Kyrie of Machaut’s Mass. It requires no adaptation here, as perhaps the most recognizable moment of the entire piece, which is again an aural marker of absolute alterity from the common-practice period – parallel octaves, fifths and chromaticism, which were all theoretically justifiable in Machaut’s day but sound alien to many modern ears. The opening of this movement therefore is an interesting moment of recomposition. It takes the most medieval-sounding aspects of the piece whole, but reinforces them with many tropes of popular medievalism missing from its original.

Example 19.2 Machaut, Messe de Nostre Dame

After this opening (from b. 15), the orchestration catapults us into the world of the post-Romantic film score, to match the rest of the soundtrack. The strings play an exact transcription of the opening of Machaut’s Mass (compare Example 19.1, bb. 15–27 and Example 19.2), and this is gradually augmented by brass and wind. This moment is, to my mind, unique in game music, in that real medieval polyphony is used – presented as an exact transcription that has merely been re-orchestrated. Ironically, it is perhaps the least medieval-sounding moment in the entire piece. The transcription of the Mass dissolves shortly before the obviously medieval cadence, allowing a contrasting entry to take over which builds in even more contrasting medievalist approaches, derived from quintessential folk-style dance-type pieces. We have percussion added for the first time, most notably including the tambourine, which draws specific connotations with on-screen representations of medieval peasant dancing. Again, for the popular imagination, this rendition is arguably more medieval sounding than the direct transcription of the real medieval music.

Conclusions

Attitudes to music history found in games are part of a mutually supportive nexus of ideas regarding the popular understanding of the sounds of the past shared between a number of different media, and indeed outside of these too. As we have seen, games like The Witcher 3 borrow their medievalism directly from film and television, allowing enormous amounts of complicated exposition to be afforded simply through audiovisual associations to intermedial shorthands. Other forms of musical expression, though connected to associations from outside of the genre, were filtered through the technological constraints of certain game systems leading, for instance, to the ubiquity of real and pastiche baroque music within fantasy games of the 1980s and 1990s. That some of these trends from games, some initially purely practical and some seemingly creative licence, later returned to influence film and television also seems clear. One thing that differentiates historical games from other audiovisual media seems to be the extent to which ‘real’ pre-baroque music is avoided. Knorr’s recomposition of the Messe de Nostre Dame is seemingly an isolated example of pre-baroque polyphony, and even this is recomposed to make it more medievalist.