10 Tonal strategies in the nineteenth-century symphony

Introduction

In addition to its vital importance for the social and aesthetic development of art music after the Enlightenment, the symphony is also pivotal for the evolution of tonality. As the most prestigious instrumental genre of the nineteenth century, it embodies on the largest scale changes in the way tonal relations underpin instrumental forms. To trace the development of symphonism from the late eighteenth century to the fragmentation of common practice at the start of the twentieth century is in a sense to observe in microcosm the history of tonality in its common-practice phases.

Understanding this history requires engagement with a variety of theoretical, technological and historical issues. To the extent that the exploration of chromatic tonal relationships undertaken by composers in the first half of the nineteenth century shadowed an emerging consciousness of tonality as a musical system, it reflects a striking shift of theoretical attitude. Where eighteenth-century theory mingled notions of mode, key and harmonic schema with concepts of topic and melodic rhetoric, nineteenth-century theorists, from Alexandre Choron’s seminal coinage in 1810 onwards, were increasingly concerned with the system of tonality itself.1 In parallel, symphonists also responded to major advances in instrumental technology and temperament, which are intimately related to the expansion of tonal means gathering momentum by the mid-nineteenth century. In particular, the rise to dominance of equal temperament and the dissemination of instrumental modifications accommodating this change underlies the increasing confidence with which composers constructed forms around remote tonal relationships.2

For a complex of reasons, however, the symphony absorbs these changes relatively slowly: chromatic tonal schemes discovered abundantly in sonatas and quartets of the 1820s and 30s are not for the most part reproduced in contemporaneous symphonies. This, in part, is a matter of organology. The gamut of chromatic keys is less easily explored in an orchestral context, thanks in particular to the restricted modulatory capacity of the French horn and the trumpet, which only eased with the widespread adoption of valve mechanisms.3 Generic identity is also a contributory factor. Chamber genres were private, domestic media, and therefore offered a relatively safe environment for tonal experimentation. The symphony was by contrast the public genre par excellence, and as such carried a weight of communicative expectation that perhaps constrained tonal innovation.

Caution also needs to be exercised in explaining developments in symphonic tonal planning within commonly disseminated conceptions of influence for the nineteenth-century symphony. In particular, the expansion of tonal means is not congruent with the influence of an all-encompassing Beethoven paradigm; it is not at all clear that Carl Dahlhaus’s notion of ‘circumpolarity’, which suggests that nineteenth-century symphonists maintained a debt to Beethoven regardless of their chronological distance from him, extends to Beethoven’s use of tonal strategy.4 In truth, examples of unorthodox strategies are relatively rare in Beethoven’s symphonies. Of his nine first movements, for example, only two contain strikingly post-classical expositional tonal schemes: Symphony No. 8/i presents its second theme initially in VI before correcting to V; Symphony No. 9/i contains a second theme in VI. Citation of Schubert as a precedent is even more problematic: by the mid-century, only the ‘Great’ C major Symphony was widely known, having been belatedly performed in 1839; the ‘Unfinished’ remained obscure until 1865, when it received its first performance under Johann Herbeck; and although all written before 1820, the symphonies nos. 1–6 were not published until 1884–5. Rather, approaches to tonal planning have to accommodate a degree of generic fluidity: expansions of the tonal system travel between genres, in a way that expressive, formal or thematic devices do not. And here the tracking of transmission and influence becomes problematic at best.

The question of influence raises broader historical problems. Although the narrative of a progressive absorption of chromaticism into established symphonic forms is appealing, it is misleading not least because it invokes the spectre of Schoenberg’s notion of tonal collapse. Leaving aside heated debates about the necessity of atonality, it is worth noting that the history of symphonic tonality in the nineteenth century is not necessarily the history of the simple replacement of diatonic relationships with chromaticism. Recognisably classical strategies persist even into the early twentieth century, so that it is perhaps more precise to write on the one hand of an expansion of tonal means that substitutes for classical practices, and on the other hand of the maintenance of diatonic relationships, as possibilities within an enlarged gamut of structural options.

The analyst of these phenomena additionally confronts several ongoing theoretical debates. The structural use of chromatic tonal relationships raises the basic question of whether keys lying beyond the diatonic cycle of relations – or even keys within that cycle, which are not tonic-defining in the manner of the dominant or subdominant – can still perform analogous structural functions. Charles Rosen, evaluating Schumann’s use of a tritone key relationship in the Finale of his Piano Sonata Op. 11, emphatically denies such equivalence:

since (at least before Schoenberg) in no sense can tonalities a tritone apart take on the functions of a tonic and dominant even in rudimentary fashion, this tritone relationship can be heard only in . . . short-range modulations. One can hardly speak of the polarization so vital to the eighteenth-century sonata forms.5

In Rosen’s terms, one cannot substitute a more distant relation for V in a sonata form and preserve any kind of productive structural tension: we hear a type of tonal ‘distance’, but not a form-defining relationship. Orthodox Schenkerian approaches tend to amplify this view. The grounding of the Ursatz in the model of the perfect authentic cadence necessarily precludes deep-structural participation of chromatic and diatonic tertiary and other relations as anything more than a means of prolonging I or V. In other words, a closing expositional tonicisation of ♭III in a major-key sonata form does not replace the expected V at the background; it simply functions as a chromatic displacement of that dominant, which now occurs at a later point in the structure. Schenkerians unwilling to admit to the possibility of a non-diatonic deep structure are unlikely to concede that chromatic keys can function as dominant substitutes.6

Other approaches of fundamentally different theoretical persuasion still either directly or obliquely reinforce this distinction. Robert Bailey’s work, designed initially to account for Wagner’s tonal habits, has been taken up by various commentators.7 The idea that nineteenth-century music elaborates a kind of ‘second practice’ is basic to this attitude: Bailey’s concepts of ‘expressive tonality’ (the pairing of keys a semitone apart), ‘directional’ tonality (the practice of beginning in one key and ending in another) and the ‘double-tonic complex’ (continuous motion between two potential tonics) have been brought together under the general observation that nineteenth-century music properly embodies two tonal practices rather than one: a diatonic practice persisting from the eighteenth century, which is monotonal (it is governed by one controlling tonic); and a second practice, which favours the pairing of (sometimes chromatically related) tonalities. In these terms, those aspects of nineteenth-century music retaining classical cadential frameworks comprise its tonal ‘structure’, whilst tertiary and other relations stand outside this as its tonal ‘plot’.8

These issues have more recently been taken up by theorists adopting neo-Riemannian attitudes or the theory of transformational networks.9Richard Cohn, for instance, has insisted on a basic difference between the asymmetrical properties of diatonic and fifth-based relationships and the kinds of symmetrical tertiary triadic cycles that become widespread in nineteenth-century music. Cohn posits a kind of ‘tonal disunity’, arising from the coexistence within a single practice of the triad’s two ‘natures’: its diatonic tonal nature; and a kind of ‘triadic post-tonality’, formed most commonly from successive major- and minor-third cycles.10 By this argument, we have to regard symmetrical key relationships as standing outside a tonal system founded on principles of cadence and prolongation. When Schubert modulates to F-sharp minor en route from B flat to F in the exposition of the first movement of his Piano Sonata D 960 (to pick an example to which Cohn has paid close attention), he exploits the triad’s dual nature, enclosing a post-tonal vocabulary of tertiary relationships (the B flat–F sharp motion) within a diatonic practice founded on fifth relationships (the overall I–V motion).11Cohn invokes Dahlhaus’s notion of a late tonal practice that ‘anticipates’ free atonality in order to contextualise such practices historically.12

Mindful of these considerations, this chapter offers an account of the evolution of symphonic tonal practice from Beethoven to Mahler, focussing on two central features: intra-movement strategies, that is tonal strategies informing individual movements; and inter-movement strategies, that is strategies unfolding across the cycle of movements. My approach reflects the view that nineteenth-century tonality comprises one expanded system, in which symmetrical and asymmetrical, diatonic and chromatic key relationships can be freely combined or substituted. This has two major ramifications. It implies, first of all, that a diatonic cadence is not the only possible guarantor of tonic identity. We have, in other words, the interplay of classical tonality with what David Kopp calls ‘common-tone tonality’; that is, a tonality in which key can be projected through conventional cadential models, or via chromatic relationships in which triads are related by the retention of one or more pivotal pitches, or even (elaborating on Kopp) by parsimonious voice leading towards a tonic.13 Chromatic thirds are the first such relationships to become standardised in nineteenth-century practice; by the later century, a wide range of chromatic relationships is in play.

Second, the interaction of harmony and tonality in such a context needs to be reconsidered. Movements often embellish an unremarkably diatonic key scheme with chromatic foreground digressions; conversely, chromatic key schemes are sometimes elaborated by an entirely conventional diatonic foreground. Such discrepancies impact upon analytical method. A Schenkerian Ursatz remains a workable model for a movement that maintains deep-structural diatonicism, because foreground chromaticism can be understood as prolonging a conventional cadential bass motion. But a movement, the tonal scheme of which comprises successive major-third relationships, turns Schenker’s fundamental structures into regional elaborations, and so undermines their basic premise. In such a context, we can only maintain the diatonic background by insisting that authentic cadences in the tonic take precedence over large spans of music that reinforce chromatic relationships.

In pursuing these practices, I will pay close attention to the interaction of tonal plot, understood as broadly encompassing the distribution of keys within a piece, bass progression, or the motion and character of the plot’s supporting bass, and form. Rethinking of the interaction of these elements constitutes a defining characteristic of nineteenth-century music. It departs most strikingly from classical precedent in situations where tonal plot and bass progression are misaligned: the music may move into the orbit of a given tonality before it is categorically established by bass motion. The relationship between plot, bass and form is throughout represented by bass diagrams, underpinned by Roman-numeral analyses, and overlaid with formal segmentations, which use the following terminology: A is main theme; B is subordinate theme; TR is transition; C is closing theme/section; an integer suffix signifies a new section within a broader function (B1, B2); a superscript integer suffix indicates a reprise or repeat (A, A1). The way in which plot and bass progression interact within the primary thematic material of a movement I will term a form’s tonal premise; the comparable formulation in subordinate material I will term its counter-premise. In a sonata form, the premise is generally synonymous with the first theme, and the counter-premise with the second theme and closing group. In situations where the second theme and closing groups tonicise distinct keys (the so-called ‘three-key exposition’), we have what I will term a double counter-premise. In sectional or recursive forms (particularly ternary forms or rondos), there is normally an association of primary section and premise, and of subsidiary sections with one or more counter-premises. For the present purposes, we can define the relationship of premises as the specific way in which the plot comes to be formulated.

Intra-movement tonal strategies

Tonal plot

In classical symphonies, tonal plots display an overwhelming degree of diatonic consistency. In the major-key symphonies of Haydn and Mozart, the subordinate theme in a sonata-form exposition, or the first episode in a rondo, overwhelmingly favours V, invariably corrected to I in the recapitulation (for sonata forms) or final episode (for rondos). In comparable minor-key movements, III is predominant, with occasional turns to the dominant minor, corrected to the tonic major or minor under recapitulation. The central episode of a rondo will generally tonicise either IV or vi. Slow movements pursuing ternary designs often deploy the parallel mode (minor or major), the dominant, subdominant or relative minor for the contrasting middle; the minuet da capo will normally frame a trio exploiting the same range of keys.

Many of these habits persist into the nineteenth century. To take sonata-form expositional second-theme keys from across the century as exemplary: expositions modulating directly from I to V can be found in the first movements of Mendelssohn’s Symphony No. 4, Dvořák’s No. 2, Balakirev’s No. 1, Mahler’s nos. 1 and 4 and Glazunov’s nos. 1 and 7. They also appear in the slow movements of Brahms’s symphonies nos. 2 and 4, and in the finales of Schubert’s ‘Great’ C major, Mendelssohn’s Symphony No. 5, Schumann’s No. 2, Brahms’s No. 2, Dvořák’s No. 6 and Saint-Saëns’s No. 1. Expositional modulations from i to III occur in the first movements of Mendelssohn’s Symphony No. 1, Schumann’s No. 4, Tchaikovsky’s nos. 2 and 6 and Brahms’s nos. 1 and 4, and in the finales of Mendelssohn’s No. 1 and Dvořák’s No. 9.

The most straightforward way in which nineteenth-century plots innovate beyond such schemes is by simple substitution of a more remote key relationship. Submediant second themes in minor-key sonata expositions have well-known Beethovenian and Schubertian precedents. The first movement of Schubert’s Symphony No. 4 in C minor (1816), for instance, contains an expositional i–VI plot. Schubert’s recapitulatory response is markedly unorthodox. It begins with a dominant reprise of the first theme at bar 177; maintenance of this fifth transposition leads to a return of the second theme in E flat at bar 214. Schubert does not ‘correct’ the non-tonic reprise until the start of the closing section: the latter stages of the second group modulate, and the closing-section material commences in C major at bar 244. He deployed a similar technique, albeit with a less radical recapitulation, in the first movement of the ‘Unfinished’ Symphony (1822). The expositional first theme closes with a perfect cadence in B minor, after which the second theme begins, following a four-bar pivot, in G. In the recapitulation, the first group modulates, cadencing in F-sharp minor. The dominant transposition then persists for the second theme, which enters in D major, and only shifts towards B after a modulating sequence and caesura in bars 273–81. The same expositional strategy is also adopted by Beethoven in the first movement of the Symphony No. 9 (1823), although the recapitulation is more direct, switching from D minor to D major for the second theme in the aftermath of the tumultuous first-theme return, before reverting to D minor in the closing section. Schubert sometimes carried his preference for lowered VI relationships into his slow movements: the ‘Great’ C major’s Andante con moto, for example, pits an A minor refrain against an F major episode that is later reprised in the tonic major.

Lowered VI substitutions remained popular throughout the century in major- and minor-key movements. For Dvořák, this strategy evidently held an association with D minor, perhaps in response to Beethoven’s example: the first-movement expositions of symphonies nos. 4 (1874) and 7 (1885) both contain B-flat second groups. Brahms deployed the same manoeuvre more sparingly. A clear example appears in the third movement of Symphony No. 3, which comprises a ternary design in which a C minor A section and its reprise frames an A-flat B section. The submediant is still commonplace at the turn of the century. Mahler’s Symphony No. 6 (1904) employs it as the second-group key in the first movement’s exposition and the initial key of the first Trio in the Scherzo (both in F major).

By the later century, the full gamut of tertiary relationships was in regular use. A clear example of simple minor-third substitution can be found in the third movement of Brahms’s Symphony No. 1, in which an A-flat major intermezzo frames a B major trio. In the first movement of his Symphony No. 3 of 1883, the exposition essentially unfurls a I–III scheme, but this is complicated by the fact that both tonalities are modally mixed: the F major first theme has strong connotations of F minor; the A major second theme succumbs to A minor in the closing section. Like Schubert in the ‘Unfinished’ Symphony, so Brahms also resolves this modulation back towards the tonic in the recapitulation by inserting an additional fifth relationship: the second theme recurs in D major, before being pulled abruptly towards F in bar 155 via a brief caesura (the location of which is suggestively similar to Schubert’s). Yet F is not sustained, and the recapitulation closes in D minor, so that it is left to the coda to confirm F as tonic.

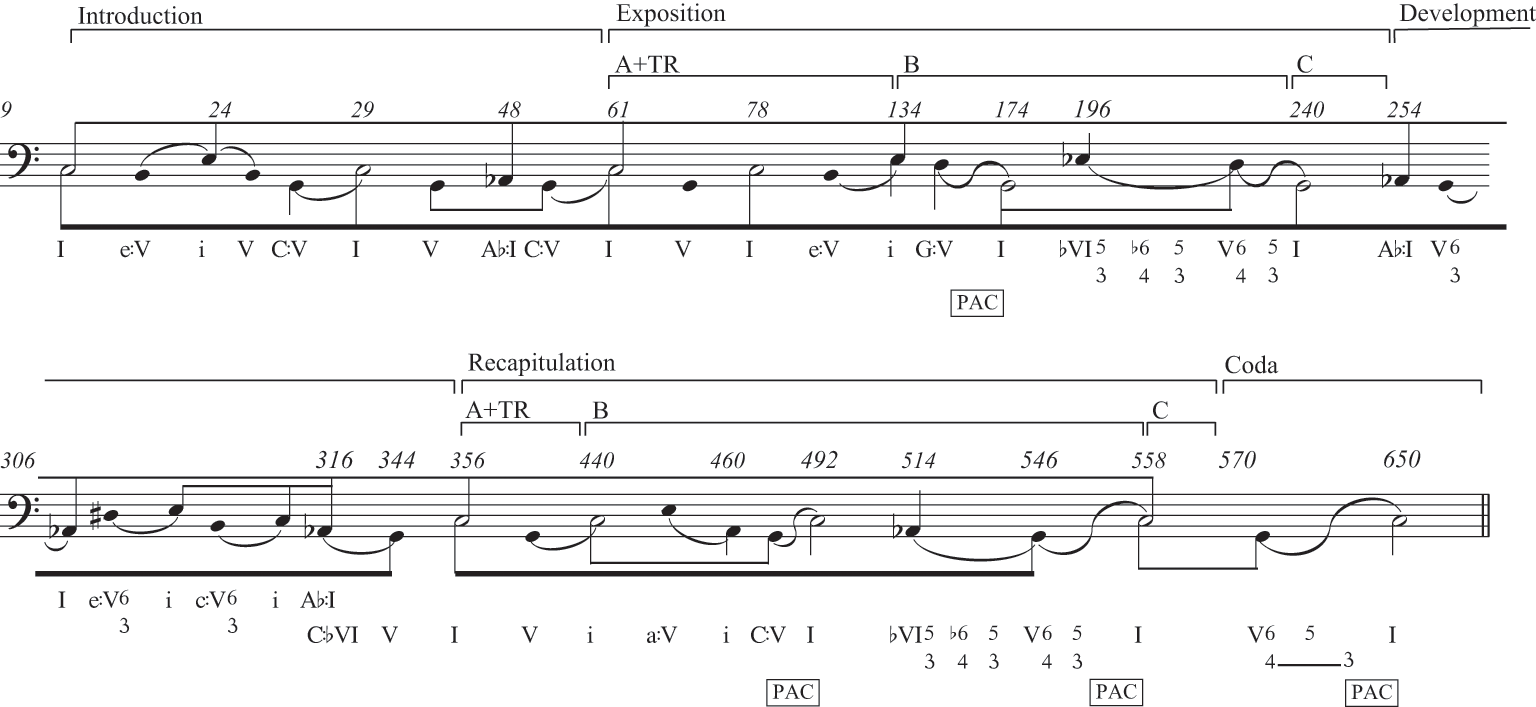

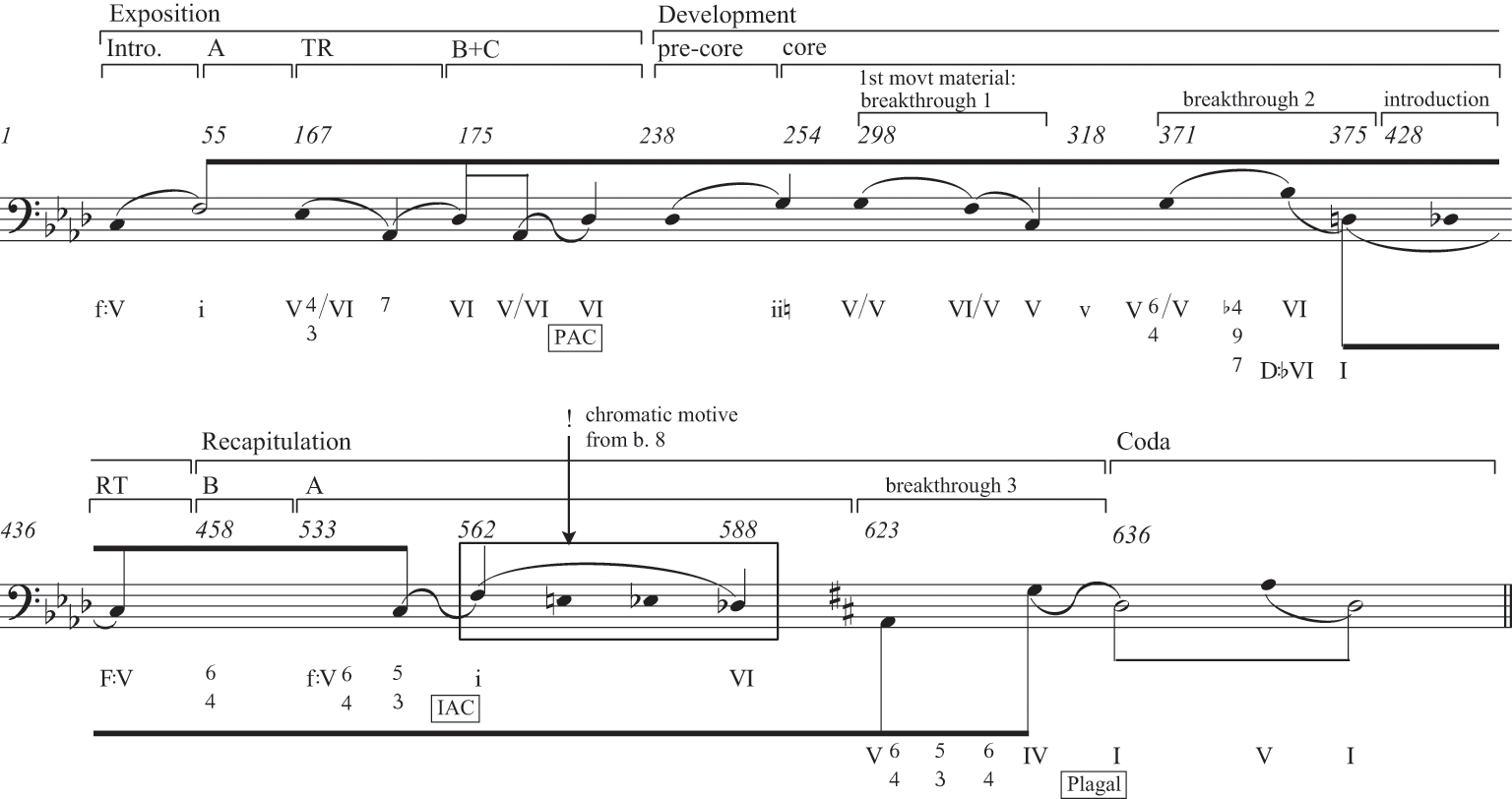

More complex situations arise when different ways of dividing the octave are combined, most commonly in the so-called ‘three-key scheme’ or double counter-premise. In the earlier nineteenth century, such plots often embed tertiary or semitonal relationships within a fifth-based framework. The first movement of Schubert’s ‘Great’ C major Symphony, for instance, contains a three-key exposition, in which a subsidiary theme in E minor is interposed between a C major main theme and an extended G major closing section, creating a tertiary bass arpeggiation outlining the tonic triad, as Example 10.1 explains.

Example 10.1 Schubert, Symphony No. 9, I, bass diagram.

In the recapitulation, E minor is corrected to C minor and then to A minor, after which the expositional second group is transposed so as to produce C major at the closing section. In one sense, the E minor theme acts as a third divider between I and V within the exposition, which is itself resolved by fifth transposition in the recapitulation as the music moves towards I. Schubert complicates this scheme, however, by according at least middleground significance to A flat, which appears as a chromatic digression within the closing section and is strongly asserted as the framing tonality of the development. As a result, E minor also participates in the symmetrical major-third division of the octave around C, as Example 10.1 shows, and so has a kind of structural double identity. Strikingly, the movement’s slow introduction adumbrates the tertiary plan, its two main departures from C major comprising E major and A flat respectively.

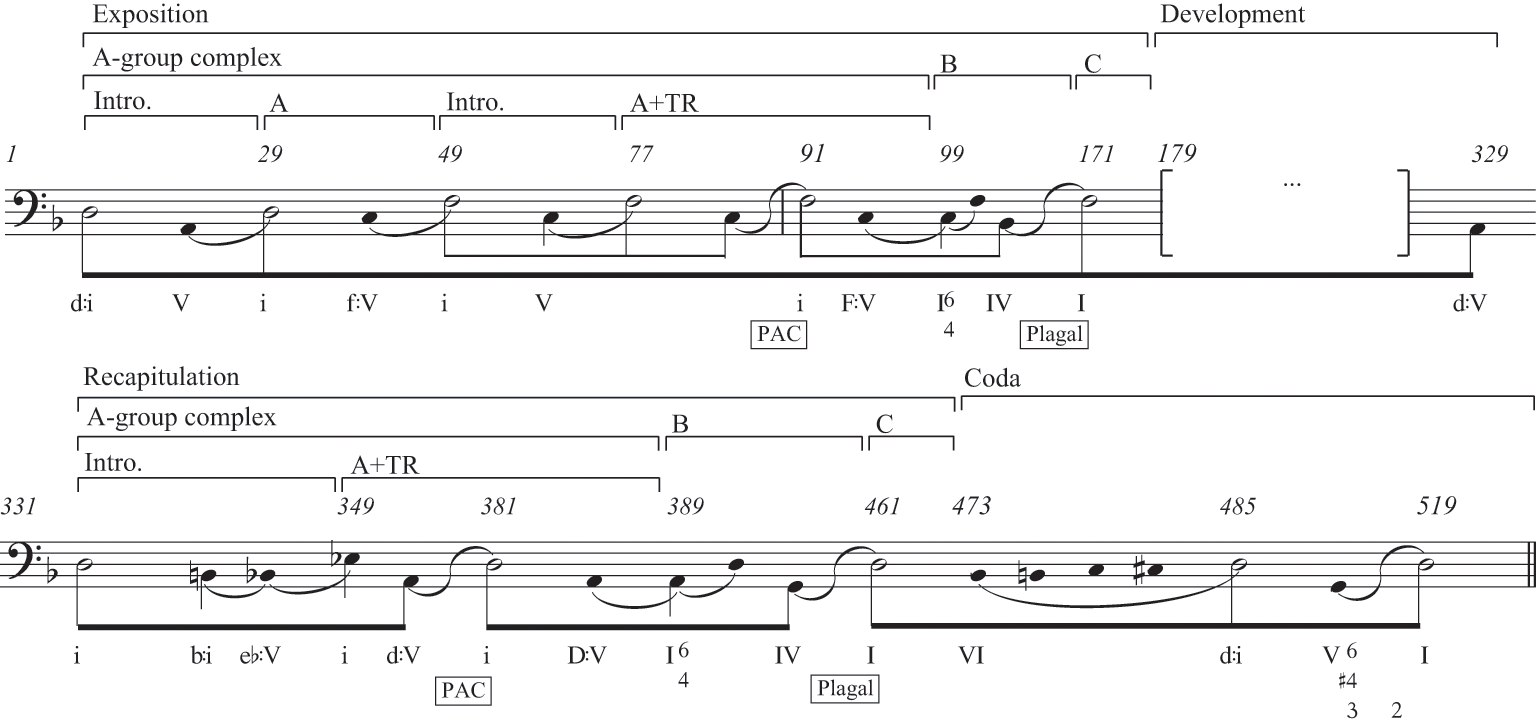

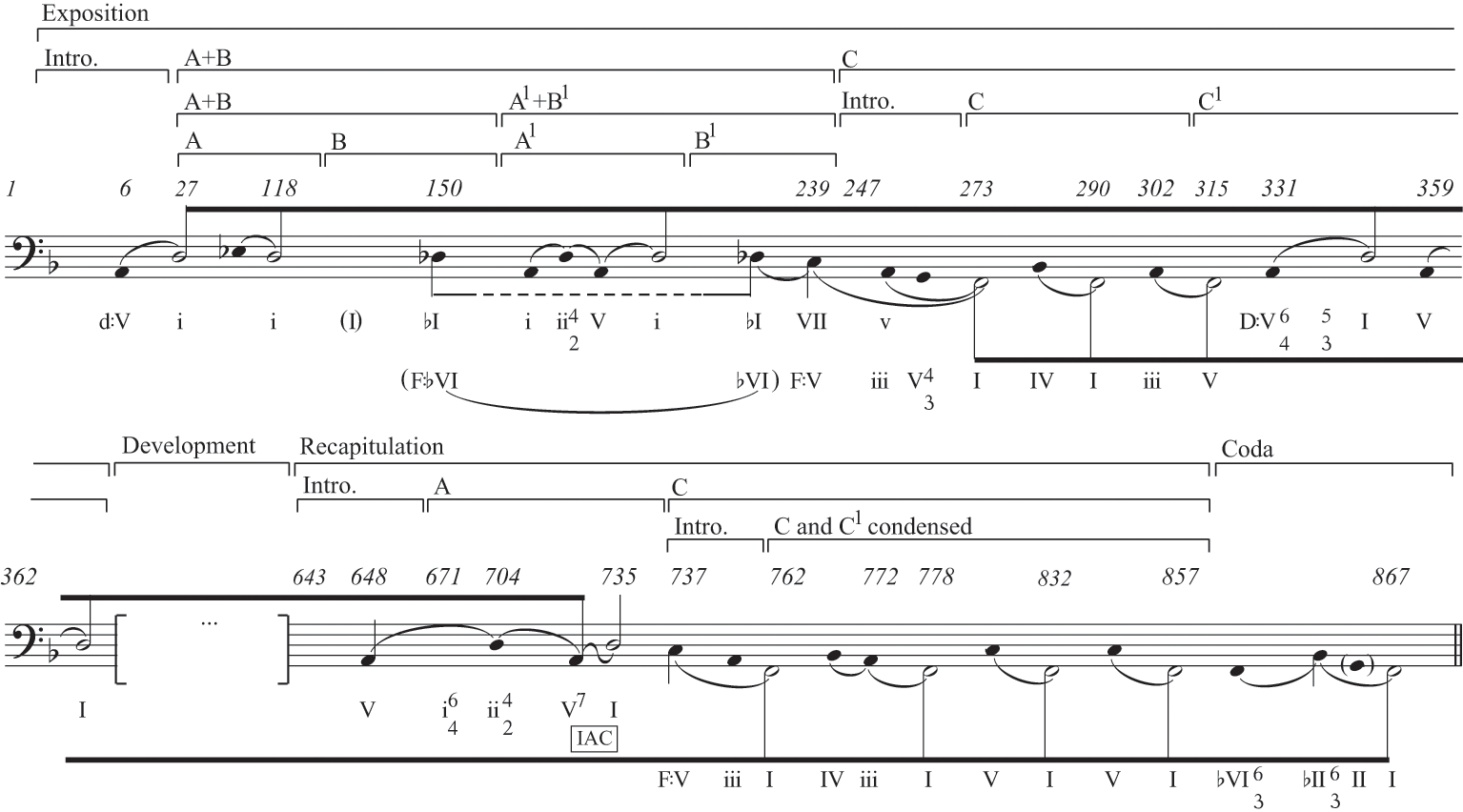

The extent and diversity of such tonal plots in later symphonic forms is attested by comparative analysis of two first movements from near-contemporaneous but geographically disparate works: Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4 of 1877–8 and Franck’s Symphony in D minor of 1886–8. In each case, the i–III trajectory common to classical minor-key forms is taken either as the starting point or framework for the projection of a network of minor-third relationships. The distribution of these relationships within the movements is, however, quite distinct, indicating the sheer flexibility the sonata idea demonstrates in accommodating the later century’s expansion of tonal means.

In both movements, the minor-third cycle is facilitated by modal mixture. As Example 10.2 explains, Tchaikovsky presents his first group as a wide-ranging but ultimately tonally closed unit, linked to the second group by a transition suggesting a modulation to III. This is undercut by modal mixture when the second theme enters at bar 116 (anacrusis bar 115) in A-flat minor. The expected i–III trajectory is then shifted so that it is orientated around A♭: the second group vacillates between A-flat minor and its enharmonic relative B major, which is secured with the triumphant entry of the closing section at bar 161. The exposition is in this way framed by a tritone, achieved by the pivotal switch from major to minor modes over ![]() . The recapitulation begins with a non-tonic reprise of the first theme over a

. The recapitulation begins with a non-tonic reprise of the first theme over a ![]() chord in D minor at bar 284 (anacrusis bar 283), which then persists as the initial key of the second group. The bulk of the exposition’s second group and closing-section complex now returns transposed, which means that it will ultimately lead to the tonic major. In short, the progression, which in the exposition moved from A-flat minor to B major, now facilitates motion towards F. Thus the recapitulation does not secure the tonic by banishing all alternatives, but by positing it as the goal rather than the starting point of a progression. After this, the coda consolidates F minor. Overlaid onto all of this is a more weakly projected major-third cycle stemming from the tonic: A minor is inserted into the first-theme group at bar 70; and D-flat major preoccupies the first part of the coda (from bar 365) as a large-scale neighbour note to V.

chord in D minor at bar 284 (anacrusis bar 283), which then persists as the initial key of the second group. The bulk of the exposition’s second group and closing-section complex now returns transposed, which means that it will ultimately lead to the tonic major. In short, the progression, which in the exposition moved from A-flat minor to B major, now facilitates motion towards F. Thus the recapitulation does not secure the tonic by banishing all alternatives, but by positing it as the goal rather than the starting point of a progression. After this, the coda consolidates F minor. Overlaid onto all of this is a more weakly projected major-third cycle stemming from the tonic: A minor is inserted into the first-theme group at bar 70; and D-flat major preoccupies the first part of the coda (from bar 365) as a large-scale neighbour note to V.

Example 10.2 Tchaikovsky, Symphony No. 4, I, bass diagram.

As Edward Aldwell and Carl Schachter have briefly noted, and as Example 10.2 explains, the result of all of this is the complete arpeggiation of a cycle of minor thirds, the mid-point of which is reached by the end of the exposition.14 By these means, Tchaikovsky in effect balances classical and post-classical tendencies. Primary and secondary themes are exposed in different keys and reprised in the same key, as they would be in a classical sonata form. But because the exposition is underpinned by a cycle rather than an opposition of two keys, Tchaikovsky can bring these themes back in the same non-tonic key (D minor) and still conclude the movement logically in the global tonic (F minor).

Franck, in contrast, employs a standard i–III relationship (D minor–F major) between his expositional first and second groups, but engineers the modulation by repeating his entire slow introduction and first group in F minor, producing a double first-theme premise, the latter part of which tonicises the parallel minor of the second theme’s key (F major). One result of this is that the traditional relationship of first group and transition is undermined: the modulation away from the tonic is secured through non-tonic re-presentation of the first theme, leaving only modal parallelism as the agent of contrast with the second group. The recapitulation enacts a series of counter-measures. First, the fortissimo reprise of the introduction with which it begins at bar 331 moves quickly from D minor to B minor, so that the exposition’s i–iii progression is balanced symmetrically by i–♮vi. More remarkably, a non-tonic reprise of the Allegro first theme ensues from bar 349 in E-flat minor, correcting to D major for the second theme via G minor and a series of sequential extensions of first-group material. This has two consequences: first, the introduction loses its framing function and signals the start of the recapitulation; second, and partly as a result, the subsequent first-group material is significantly less tonally stable than its exposition counterpart, and it is left to the second group and coda to re-establish the tonic (the movement is summarised in Example 10.3).

Example 10.3 Franck, Symphony, I, bass diagram.

The preoccupation with third relationships is extended in the second and third movements. The Allegretto’s famous conflation of slow movement and scherzo (whereby the latter appears as a middle-section variation of the former’s main theme, with which it is then combined at the reprise) is also an exploration of chromatic third relationships, since the scherzo begins in G minor, whereas the movement’s key is B-flat minor. The D major Finale elaborates, in turn, on the first-movement recapitulation’s motion to B minor, initiating its second theme at bar 72 in B major, and following this at bar 125 with a reprise of the slow movement’s main theme in B minor, the result being an idiosyncratic three-theme exposition. The downward motion through the minor-third cycle is continued in the development section, the climax of which (bars 175–202) forcefully establishes A-flat major. The cycle is, however, not completed. F♯ plays no role: the first themes of the Finale and second movement are recapitulated in D major and D minor respectively (bars 268 and 300), and the movement closes, after a retrospective glance towards first-movement material, in the tonic major.

Bass progression and formal function

In classical forms, the tonal plot and the material that articulates it are very often coordinated with cadential bass motion. In nineteenth-century music, bass progression, formal function and plot are by contrast frequently misaligned. An emphatic example can be found in the recapitulation of the first movement of Schumann’s Symphony No. 3 (1850), beginning at bar 411 and reproduced in Example 10.4.

Example 10.4 Schumann, Symphony No. 3, I, bars 409–15.

Schumann’s first theme is reprised over a ![]() chord, resolving the first-inversion German augmented sixth in bars 409–10. This has two immediate consequences. First, the theme’s tonic return is not a point of arrival for the bass, which rather remains active across the formal boundary between development and recapitulation. Second, the stability of the tonic is questioned: the

chord, resolving the first-inversion German augmented sixth in bars 409–10. This has two immediate consequences. First, the theme’s tonic return is not a point of arrival for the bass, which rather remains active across the formal boundary between development and recapitulation. Second, the stability of the tonic is questioned: the ![]() sounds like a suspension over the dominant, which resolves on the first beat of bar 415. In fact, the tonic receives no cadential confirmation in the bass for the entirety of the first-group reprise. V is prolonged until bar 430, where it moves upwards towards vi, initiating a passing modulation to V of that key.

sounds like a suspension over the dominant, which resolves on the first beat of bar 415. In fact, the tonic receives no cadential confirmation in the bass for the entirety of the first-group reprise. V is prolonged until bar 430, where it moves upwards towards vi, initiating a passing modulation to V of that key.

The result is that the often discrete formal functions of development and recapitulation are here elided, because the latter is not distinguished by tonic arrival in the bass progression. Recapitulatory elisions over a ![]() chord are widespread in nineteenth-century symphonies. A beautiful example occurs in the first movement of Mendelssohn’s Symphony No. 4, where a retransitional emphasis on vi is chromatically sidestepped in two bars, and the first theme returns as part of a

chord are widespread in nineteenth-century symphonies. A beautiful example occurs in the first movement of Mendelssohn’s Symphony No. 4, where a retransitional emphasis on vi is chromatically sidestepped in two bars, and the first theme returns as part of a ![]() progression in bars 341–4. In the later century, the sense of the

progression in bars 341–4. In the later century, the sense of the ![]() as an elaboration of V is replaced by the bolder assertion of the tonic in its second inversion. Examples include the first movements of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 1 and Dvořák’s Symphony No. 5, which both approach a tonic

as an elaboration of V is replaced by the bolder assertion of the tonic in its second inversion. Examples include the first movements of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 1 and Dvořák’s Symphony No. 5, which both approach a tonic ![]() from a retransitional augmented sixth, and of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 5, which approaches the tonic

from a retransitional augmented sixth, and of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 5, which approaches the tonic ![]() from a diminished third. More striking still is the first movement of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4, the recapitulation of which as we have seen begins with a forceful statement of the first theme over a sustained

from a diminished third. More striking still is the first movement of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4, the recapitulation of which as we have seen begins with a forceful statement of the first theme over a sustained ![]() in the remote key of D minor.

in the remote key of D minor.

Example 10.5 Mahler, Symphony No. 6, I, bars 291–7.

Example 10.6 Mendelssohn, Symphony No. 2, I, bars 81–106.

More harmonically audacious recapitulatory elisions can be found at the turn of the century. In the first movement of Mahler’s Symphony No. 6, the recapitulation begins at Fig. 28 in the parallel major, reached via a retransitional chromatic ascent (Example 10.5). A major is, however, quickly destabilised by two jarring harmonic devices: the bass turns towards F, which becomes an upper neighbour to the climactic A minor ![]() chord at Fig. 29, which forms the true goal of the progression initiated in the retransition. In a strategy owing something to the example of Schumann’s Symphony No. 3, the bass E then persists for another thirteen bars, finally resolving to A at Fig. 30.

chord at Fig. 29, which forms the true goal of the progression initiated in the retransition. In a strategy owing something to the example of Schumann’s Symphony No. 3, the bass E then persists for another thirteen bars, finally resolving to A at Fig. 30.

The maintenance of an active bass progression across a formal boundary is not restricted to recapitulations; the presentation of a second theme over an unstable chord inversion or oblique progression is also common. Example 10.6 shows a lovely instance of transition/second-theme elision in the exposition of the first movement of Mendelssohn’s Symphony No. 2 (1840). The transition finds its way conventionally to V/V, reinforced by a nine-bar standing on V in bars 78–82. The initial tonal goal of the second theme is, however, ♭VII, confirmed at the end of the theme’s first phrase by an authentic cadence. Instead of resolving the transition’s dominant preparation to its tonic (V), Mendelssohn turns the bass C into the root of an augmented triad neighbouring D♭, which then moves by step through ii![]() /♭VII onto V/♭VII; it is this dominant that is resolved with the cadence in bars 89–90. A flat does not, however, persist as the secondary key; instead, Mendelssohn supplies a cadential extension in bars 90–4, which shifts towards F minor, and the second theme is then restated, via a change of mode, in F major, moving towards an authentic cadence closing in that key in bars 105–6, after which the closing section ensues. Properly speaking, the bass C established in the transition is not resolved until the end of the second theme, remaining active beneath the intervening harmonic digression and retrieved in bar 105.

/♭VII onto V/♭VII; it is this dominant that is resolved with the cadence in bars 89–90. A flat does not, however, persist as the secondary key; instead, Mendelssohn supplies a cadential extension in bars 90–4, which shifts towards F minor, and the second theme is then restated, via a change of mode, in F major, moving towards an authentic cadence closing in that key in bars 105–6, after which the closing section ensues. Properly speaking, the bass C established in the transition is not resolved until the end of the second theme, remaining active beneath the intervening harmonic digression and retrieved in bar 105.

The double-tonic complex

In the later nineteenth century, the presence of an increasingly chromatic harmonic foreground complicates the idea that an initial theme or section will unambiguously prolong one key. As a result, the association of the parts of a form with a single tonal premise is weakened or else breaks down altogether. Rather, it becomes more accurate to write of the presentation of a harmonic field, defined by a progression that alludes, either by cadence or implication, to multiple, often chromatically related tonics within a single theme group or section, without necessarily confirming any of them. This situation is analogous to the ‘double-tonic complex’ theorised by Bailey as the basis of the ‘Einleitung’ of Wagner’s Tristan, in which the music gives up the prolongation of a discrete tonic and shifts continuously between implied third-related keys.15

Example 10.7 Bruckner, Symphony No. 7, IV, bars 1–9.

Many subsequent composers grappled with the problem of how to incorporate the idiom of Tristan – which populated an open, dramatic form – into the closed structures of the symphony. In the Finale of his Symphony No. 7 (1883), Bruckner composed a first theme, which begins unambiguously with an arpeggiation of the tonic E major (a reference to the first theme of the first movement), but then veers by ascending semitonal voice-leading or SLIDE transformation towards an authentic cadence in A-flat major at its conclusion (see Example 10.7). The triadic major-third progression A flat–E minor in bars 9 and 10 leads to a consequent phrase beginning in V of E, which again modulates by chromatic voice leading, this time reaching a cadence in B-flat major. The ensuing transition finds its way to V of F minor by bar 34, but this preparation is not taken up by the second theme, which begins in A-flat major. The first-theme group is essentially classical in its design – a sentential period is succeeded by a sequential transition tending towards motivic fragmentation – but its harmonic structure departs fundamentally from the classical paradigm, both in its detail and in its general distance from the idea that a first theme should articulate a single tonic key. Rather, Bruckner composes a theme that establishes I and V as starting points, but confirms ♭IV and ♭V by cadence. The tonal strategy of the movement as a whole is not so much about making non-tonic material (the expositional second theme) prolong the tonic in the recapitulation, but rather involves seeking a variant of the first theme that cadences as well as starts in E, achieved finally in the augmentation of the theme’s cadence in bars 313–15 leading into the coda, as appraised in Example 10.8.16

Example 10.8 Bruckner, Symphony No. 7, IV, bars 312–15.

In these circumstances, we might write of progression as premise: the theme does not establish a prolonged key, but a progression, in which the eventual tonic is articulated at salient moments.

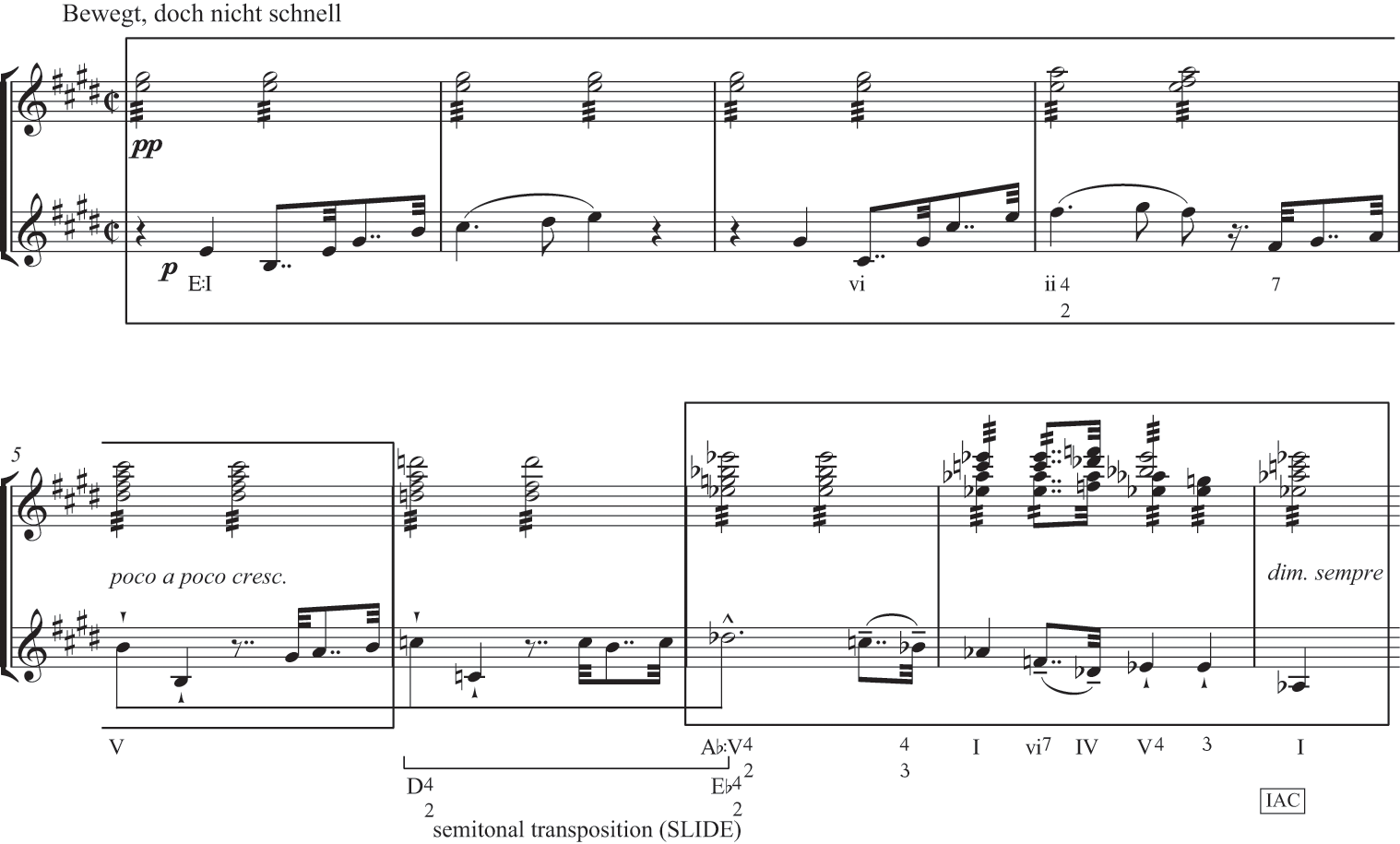

The main theme in the first movement of Elgar’s Symphony No. 1 (1908), reproduced in Example 10.9, is even harder to subsume within a single tonal premise. Arguments about the theme’s tonality – chiefly whether it expresses D minor or A minor – persist. Both readings have merit.17 On the one hand, the principal motive is poised around V of A minor, a region to which the first phrase returns at its end. On the other hand, the key signature implies D minor, and this is reinforced when the first theme is repeated in transposition from performance Fig. 8. The implication of D is undoubtedly of greater significance for the Symphony as a whole, since it constitutes the Adagio’s tonic and referential key for the first theme in the Finale.

Example 10.9 Elgar, Symphony No. 1, I, bars 50–8.

Yet perhaps the assignment of an unequivocal tonic misses the point, which is the theme’s tonal mobility. At the level of tonal plot, its function is not to project a single tonic, but rather to embed the implication of structurally important keys within a chromatic progression, which allocates gestural salience to other harmonic events, including the implication of G flat three bars before Fig. 7. As Example 10.9 displays, the theme’s presentation phrase in bars 51–8 moves between implications of A and D minor that are fulfilled neither by cadence nor prolongation. This instability is connected to the theme’s non-tonic status even within the first movement, which begins with a markedly diatonic introduction in A-flat major, in which key both the first movement and Finale conclude. The uncomfortable harmonic pivot from the introduction’s final bar takes an A-flat tonic bass, temporarily reinterprets it as ![]() of F sharp over an enharmonic bass, and then quickly forces this to function as a neighbouring chord to V/III in A minor at the start of the Allegro. The ambiguity of this sonority is never satisfactorily dispelled. It functions rather as signifier of the tension between the framing stability of A flat and the harmonic turmoil characterising the principal agent of the first movement’s sonata action.

of F sharp over an enharmonic bass, and then quickly forces this to function as a neighbouring chord to V/III in A minor at the start of the Allegro. The ambiguity of this sonority is never satisfactorily dispelled. It functions rather as signifier of the tension between the framing stability of A flat and the harmonic turmoil characterising the principal agent of the first movement’s sonata action.

Progressive tonality

The concept of ‘progressive’ or ‘directional’ tonality generally refers to the habit of beginning a movement or work in one key and ending it in another.18 The critical shift between eighteenth- and nineteenth-century practice in this respect resides in the application of progressive schemes in the context of closed instrumental forms. The idea that an act of an opera or part of an oratorio might begin and end in different keys is a commonplace for baroque and classical composers; but the use of the same strategy in an instrumental cycle is highly unusual.

Again, the symphony lagged behind other instrumental cycles in this respect. Despite their accommodation in chamber genres as early as the Finale of Mendelssohn’s String Quartet Op. 12 (1829), and their much-scrutinised application in Chopin’s single-movement forms of the 1830s and 40s, progressive tonal schemes within a symphonic movement remain relatively rare before 1850.19An early example can be found in the third movement of Louis Spohr’s Symphony No. 4 (1832), which consists of a D major march yielding, in its coda, to a chorale prelude in B flat subtitled ‘Ambrosian Hymn of Praise’. Spohr later employed a descending minor-third plot in the Finale of his Symphony No. 9 in B minor (1849–50), which begins in D major, but shifts to B major at its conclusion. The same scheme is adopted by Liszt in the second movement of his Dante Symphony (1855–6): the entry into purgatory is initiated by a sustained ![]() chord of D major; the Magnificat signifying the entry into paradise is grounded in B major.

chord of D major; the Magnificat signifying the entry into paradise is grounded in B major.

Four notable examples from the later century occur in the finales of Dvořák’s Symphony No. 5 (1875) and (more famously) Mahler’s symphonies nos. 1 and 4, and in the first movement of Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 (1893–6). Dvořák’s Finale traces an overall trajectory from A minor to F, the global key of the Symphony (see Example 10.10: the initial tonality is beamed above the stave, goal tonality below it, a notation also adopted in examples 10.11 and 10.12).

Example 10.10 Dvořák, Symphony No. 5, IV, bass diagram.

F major is not, however, completely evaded in the movement’s initial material; rather, a first-theme group emphasising A minor concludes with a climactic fortissimo passage in F major (bars 55–811), which dies away over an F pedal (bars 81–92). Against this, Dvořák sets a tonally mobile second group, which begins in D-flat major, but settles over a ![]() chord of G by bar 117. In the recapitulation, the first theme maintains its expositional trajectory with some regional deviations, commencing in A minor at bar 219 and modulating to F major by bar 273. Dvořák then simply stays in F for his second-theme reprise, beginning at bar 292, and stabilises this key through the addition of a substantial second-group codetta in bars 322–61, which forms the starting point for the coda.

chord of G by bar 117. In the recapitulation, the first theme maintains its expositional trajectory with some regional deviations, commencing in A minor at bar 219 and modulating to F major by bar 273. Dvořák then simply stays in F for his second-theme reprise, beginning at bar 292, and stabilises this key through the addition of a substantial second-group codetta in bars 322–61, which forms the starting point for the coda.

Example 10.11 Mahler, Symphony No. 1, IV, bass diagram.

Mahler’s examples are more clearly delineated. The Finale of Symphony No. 1 is summarised in Example 10.11. In effect, Mahler here composes a sonata form in F minor, in which a two-key exposition (first theme in F minor; second in D-flat major) is answered by a reversed recapitulation (second theme in F major; first theme in F minor), yielding to a coda that reasserts the first movement’s D major tonic.20 The result is a two-level strategy, as the Example explains: F minor functions as the tonic at the level of the sonata form; D major obtains at the level of the movement cycle. This means that, at least as far as tonality is concerned, the sonata-form body of the Finale itself has two functions – as a single-movement form and as the finale of a cycle – whereas the coda has only one, furnishing the cycle’s tonal close. At the same time, D major is anticipated by the ‘breakthrough’ moment in the development (Fig. 33) addressed in Chapter 9, which starts off in C and then diverts abruptly to D four bars later. The same material forms the substance of the coda, here, however, presented entirely in D. In this way, Mahler plants a disjunctive tonal event inside the sonata form, which recurs, tonally unified, to complete the Symphony.

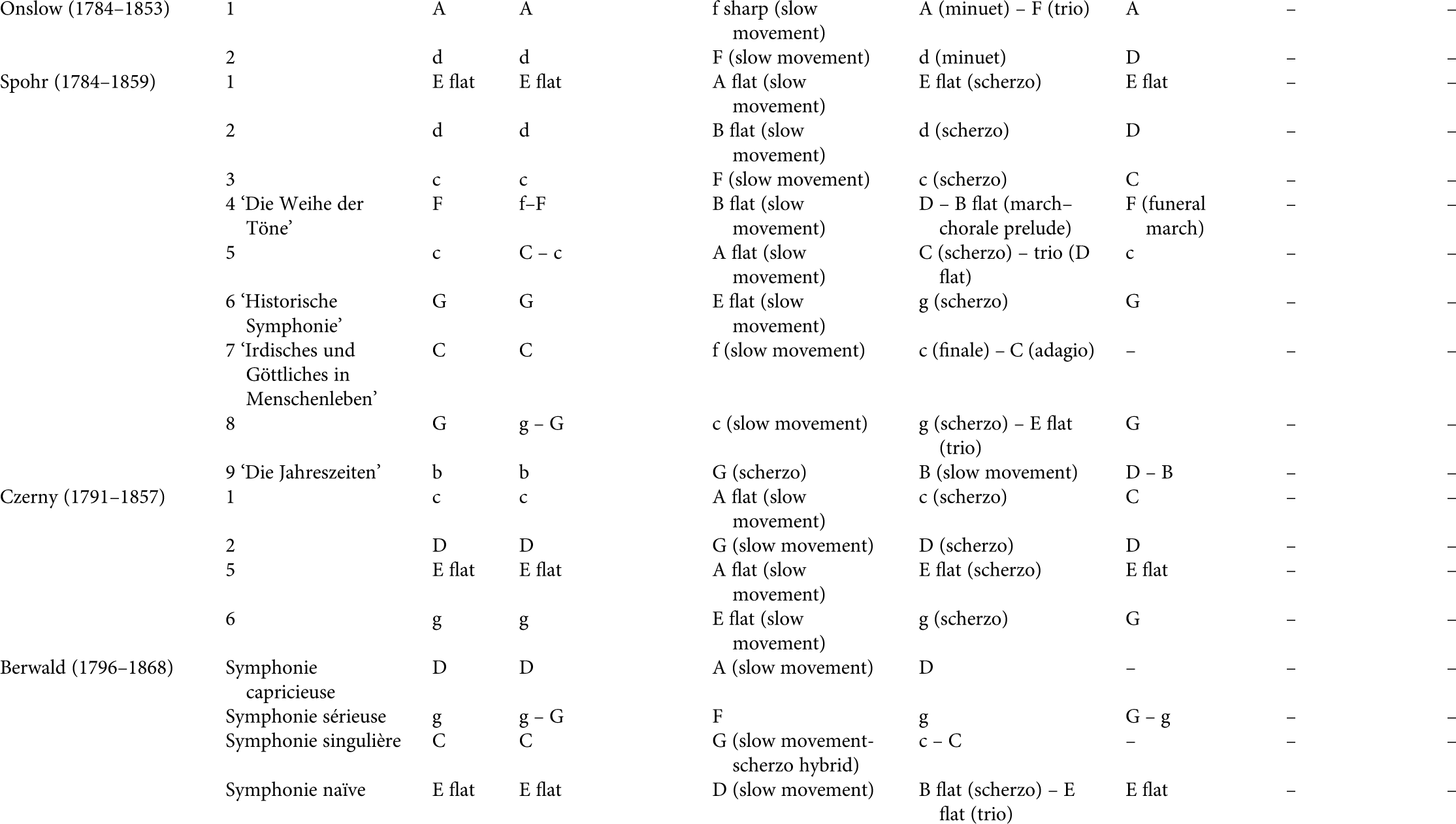

The first movement of Symphony No. 3, summarised in Example 10.12, is altogether more complex, reflecting the vast structural expansion that Mahler undertakes (six movements in total, two vocal movements inserted between the Rondo and concluding Adagio and a first movement lasting nearly half an hour). The exposition comprises what James Hepokoski might call a large ‘double rotation’ of the first and second groups, prefaced by a thematic introduction, and rounded off with a long martial closing group.21 In the initial rotation, the first group is grounded in D minor and the second shifts between B flat and D before finally asserting D flat at bar 150. In the second rotation, the first group is again a closed unit in D minor, and the second begins as it had in the first rotation, but cedes to the closing section, which sets off in C major at bar 247, consolidates F with the return of the introduction material at bar 273, but turns from Fig. 27 towards D major, in which key the exposition concludes at bar 362, before reverting to D minor for the start of the development.

Example 10.12 Mahler, Symphony No. 3, I, bass diagram.

The recapitulation compresses the exposition’s double design into a single span, whilst retaining core features of its tonal scheme. The first theme is again a tonally closed unit in D minor, and the martial closing section returns categorically in F from bar 762; the second group is, however, excised, excepting the incorporation of thematic elements into the march. At base, Mahler replaces the tonal dialectic of the classical sonata with a problem of bifocal orientation. The movement’s sustaining tension is between an exposition that surrounds F with D, and a recapitulation that construes F as the goal tonic.

Inter-movement tonal strategies and the cycle of movements

Key schemes governing whole symphonies generally respond to the same expansion of tonal means conditioning tonal strategies within movements. Three issues are of paramount importance: the choice of keys for inner movements; their relationship to the outer movements; the overall trajectory thus created. Again, the crucial factor here is the encroachment of chromatic key relations. Tonicisations of V, IV or vi give way to more remote relations, very often organised so as to reveal clear large-scale strategies, which sometimes reflect more localised key schemes.

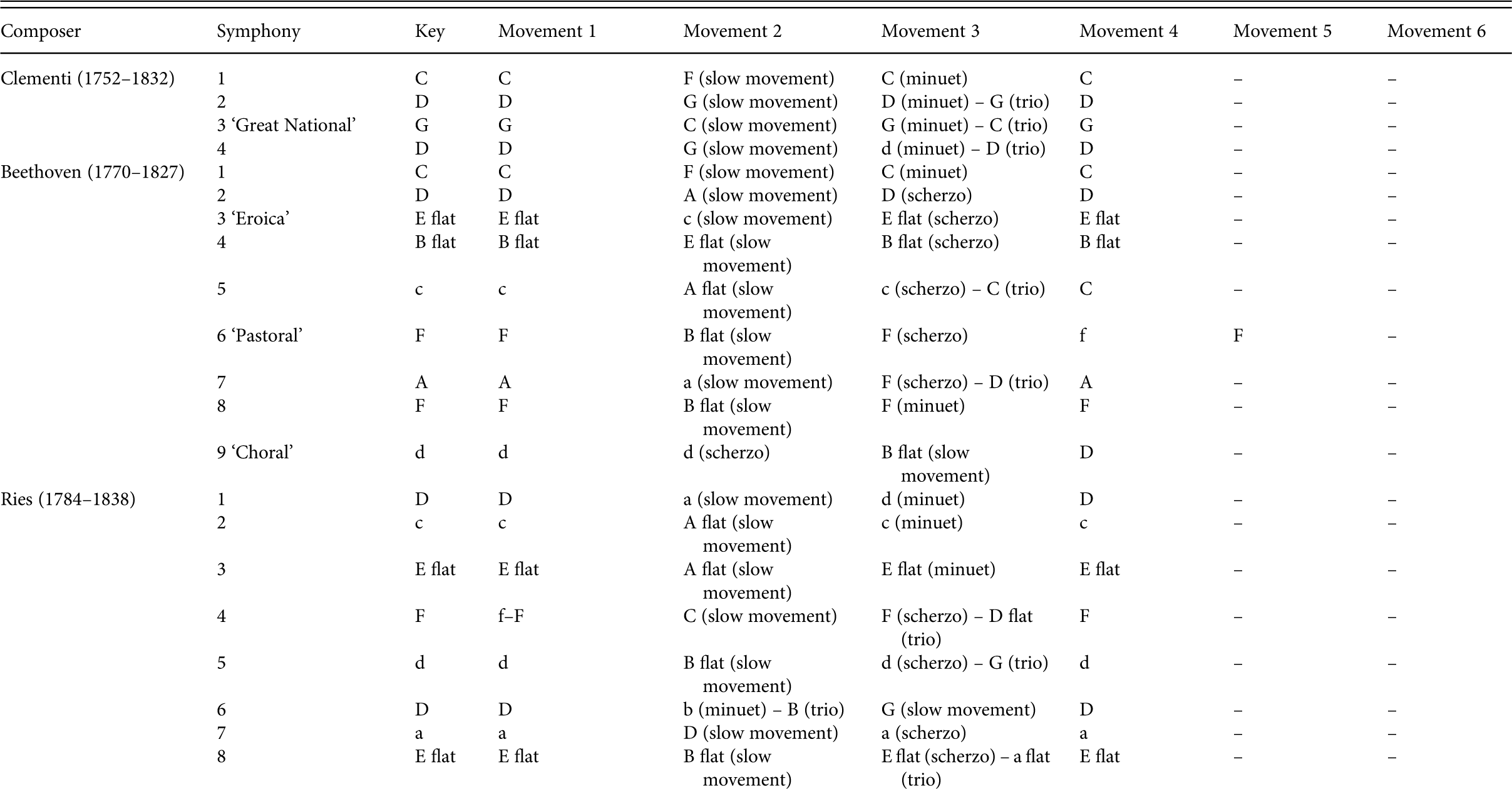

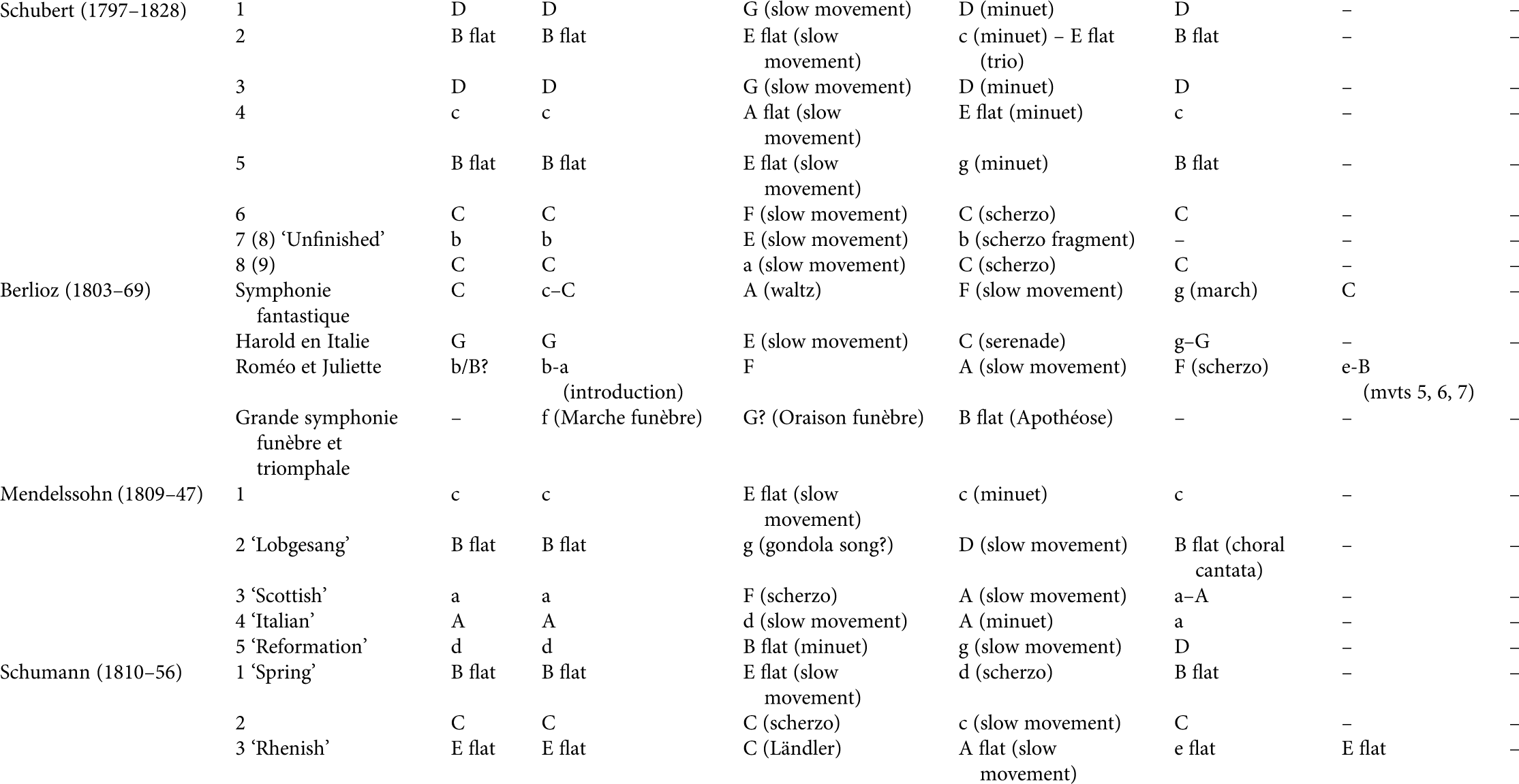

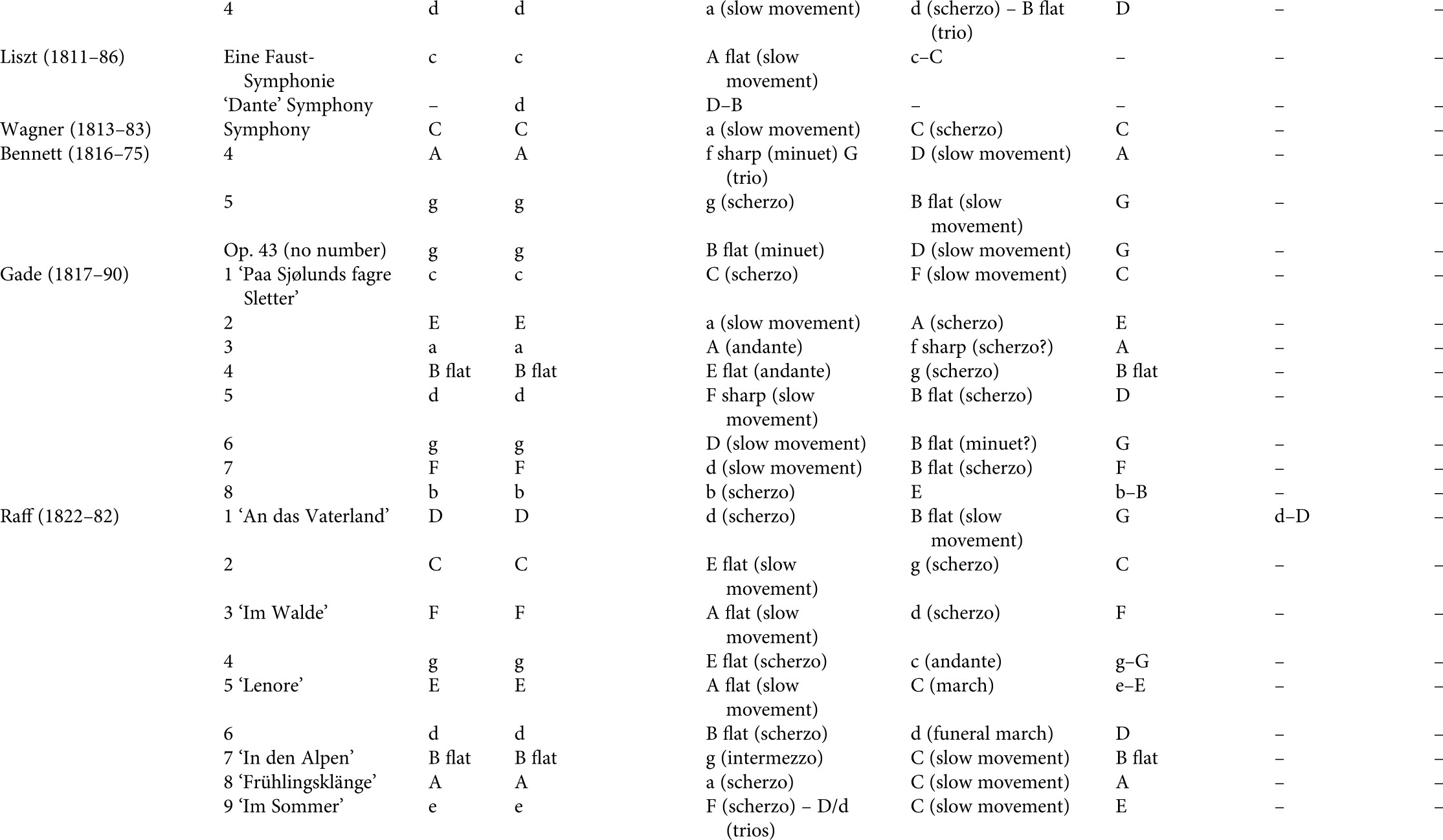

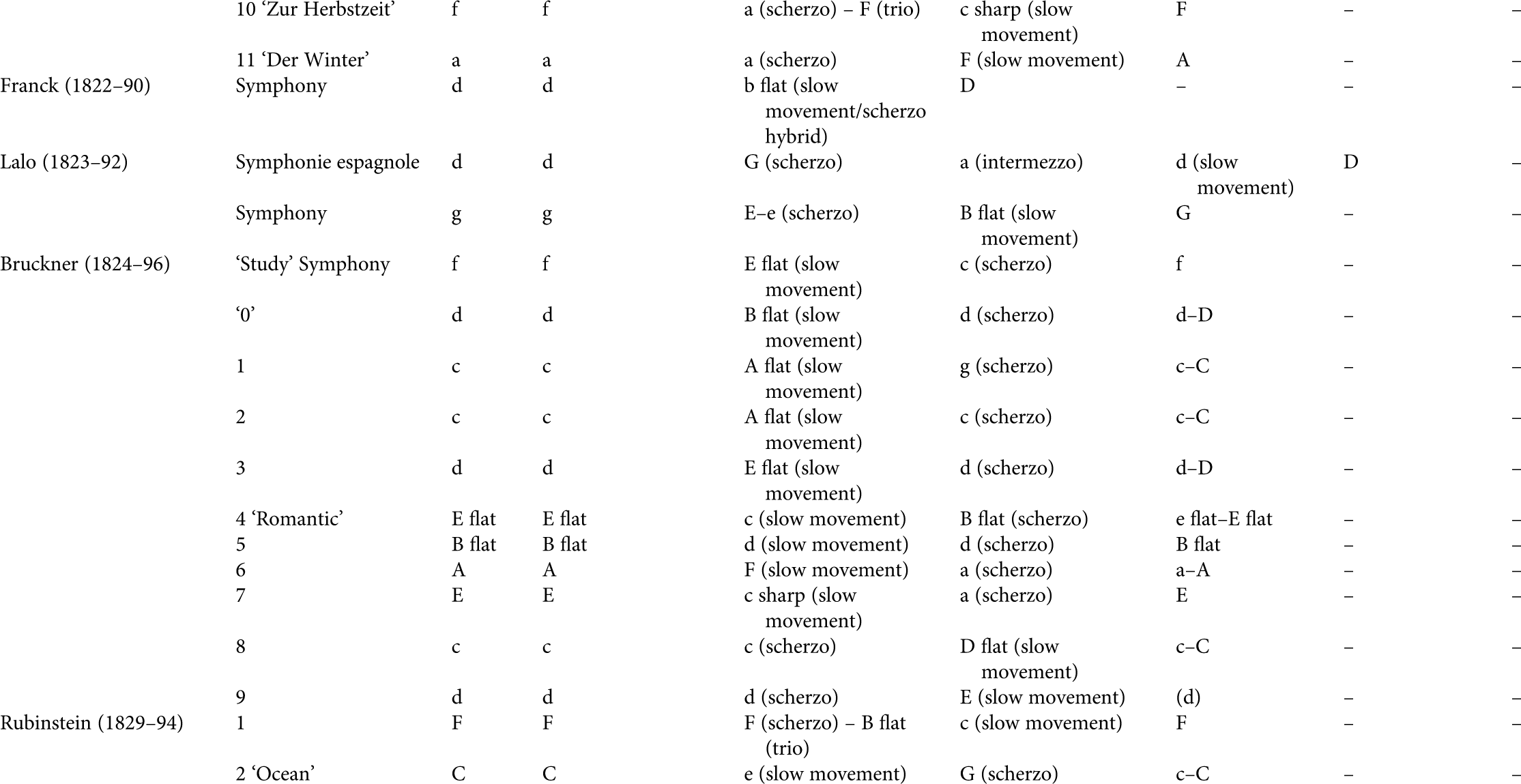

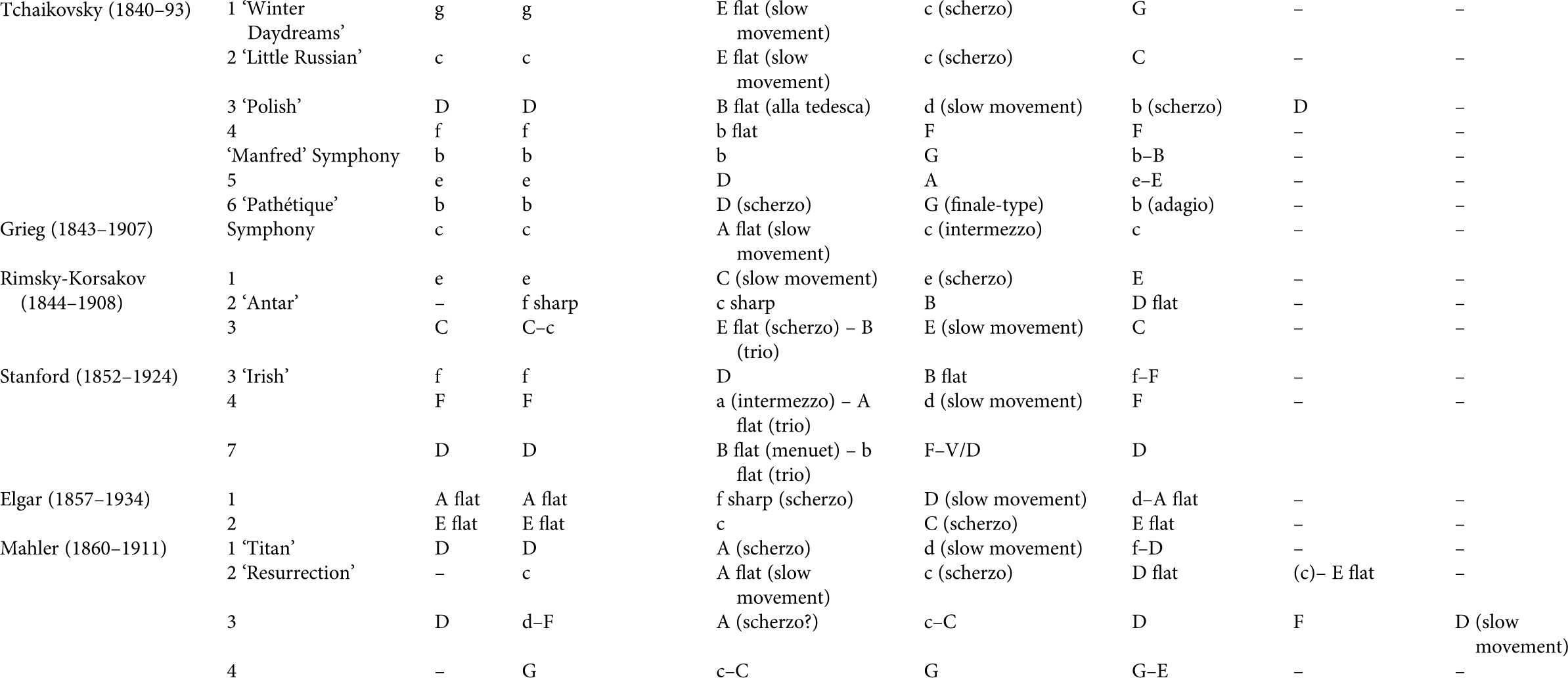

Whereas an exhaustive summary of intra-movement tonal plots is hardly feasible here, an overview of inter-movement schemes is more practical. Table 10.1 therefore appraises the key schemes of 163 symphonies by 34 composers, written between 1800 (Beethoven’s No. 1) and 1911 (Elgar’s No. 2), arranged by chronology of the composer’s birth. The list is designed to be representative rather than comprehensive; symphonies by Lachner, Kalliwoda, Burgmüller, Volkmann and others are omitted for this reason, rather than out of any critical bias. Whether or not a composer is represented by their total symphonic output has varied with availability: Glazunov, for instance, is represented in full; Stanford only by symphonies nos. 3, 4 and 7. (Clementi’s total symphonic oeuvre remains a matter of speculation; the four symphonies currently published with numerical designations are given here.)22 Keys are assigned letter names rather than Roman numerals, to avoid designating an overall tonic in situations where a symphony begins and ends in different keys. Major keys are shown with capital letters; minor keys with lower-case letters. The order of the inner movements (scherzo/minuet and slow movement) is clarified on a case-by-case basis. In situations where the trio of a dance movement comprises a self-contained section expressing a notable modulation, its key is shown.

Table 10.1 Cyclical tonal schemes of 163 symphonies composed between 1800 and 1911

The Table makes clear the extent to which the development of key schemes tracks the chromaticisation of tonality. Beethoven’s key choices remain largely conservative. Symphonies nos. 1, 4 and 8 have subdominant slow movements, while No. 2 favours the dominant, and submediant slow movements are preferred in both minor-key symphonies. Two major-key symphonies have minor-key slow movements: the Eroica shifts to the relative minor; No. 7 moves to the parallel minor. Only one other instance of modal parallelism occurs, namely the ‘Storm’ movement of the ‘Pastoral’ Symphony. Moreover only one Symphony (No. 7) has a non-tonic scherzo, in the relatively remote key of the lowered submediant, although this remoteness is ameliorated by the preceding A minor slow movement and the tonicisation of D major in the Trio.

Despite his more adventurous intra-movement strategies, Schubert’s cyclical key schemes also remain closely within the orbit of the tonic. Symphonies nos. 1–3, 5 and 6 all have subdominant slow movements, and the ‘Unfinished’ responds to its B minor first movement with a subdominant-major slow movement. Symphonies nos. 2 and 5 contain a practice that occurs in none of Beethoven’s symphonies, which is that they both introduce minor-key minuets into major-key symphonies. Schubert, however, remains within the cycle of related keys in both cases: the Minuet of No. 5 tonicises the relative minor and of No. 2 the supertonic.

Contemporaries of Beethoven and Schubert are sometimes more audacious. Clementi’s Symphony No. 4 goes a step beyond Schubert, in that its Minuet is cast in the tonic minor; the same strategy is developed by Ferdinand Ries, for instance in the modal mixture between outer movements (D major) and Minuet (d minor) in his Symphony No. 1 (1809), or the Minuet and Trio of No. 6 (1822), which tonicises the relative minor (B minor) and then shifts to its parallel major for the Trio, creating a chromatic third relationship with the global tonic D. Ries’s precise contemporary Spohr, who composed ten symphonies between 1811 and 1857, nine of which appear in Table 10.1, is more innovative again, experimenting both with progressive schemes within movements (as we have already seen), modal mixture (for instance between tonic and subdominant major and minor in the Symphony No. 8), and chromatic relations (the D-flat major of the Trio in No. 5, which is a semitone above the key of the Scherzo). Franz Berwald’s four contributions, written between 1842 and 1845, are at least in this respect more conservative. His most notable experiment occurs in the Symphonie sérieuse, the slow movement of which tonicises the lowered leading note.

Mendelssohn and Schumann are only marginally more ambitious than Schubert. The A minor–F major relationship between first movement and Scherzo in Mendelssohn’s Symphony No. 3 mimics the same progression in the inner movements of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7, but the submediant Scherzo of No. 5 and the mediant-major slow movement of No. 2 have no Beethovenian or Schubertian precedents. Symphony No. 4 contains possibly Mendelssohn’s most unusual scheme. The minor-key Finale departs from Viennese-classical practice: minor-key classical symphonies frequently shift to the tonic major in their finales, but the opposite trajectory has scant precedent (Haydn’s Symphony No. 70 constitutes one precursor). Mendelssohn paves the way for the tonic-minor Finale through the choice of iv as the key of the slow movement. The result is a dovetailed modal mixture on the largest scale, in which first movement and Minuet sustain I, whilst slow movement and Finale emphasise iv and i. Schumann is generally more cautious. His most striking decisions are the employment of VI as the key of Symphony No. 3’s second movement and the choice of the mediant minor for No. 1’s Scherzo. At the same time, No. 2 is the first symphony in the list to remain entirely in the global tonic, albeit shifting from major to minor in the slow movement.

Berlioz and Liszt are both more consistently experimental. The scheme of the Symphonie fantastique explores VI, IV and v; Harold en Italie similarly tonicises VI in its slow movement; and Roméo et Juliette is framed by B, but the love scene tonicises A and the ‘Queen Mab’ Scherzo F, although the sense of an orthodox symphonic design and global tonic is clouded by dramatic elements. The Grande symphonie funèbre et triomphale (1840) is the first example in the Table of a progressive key scheme across an entire symphony (F–B flat), followed by Liszt’s Dante Symphony (1855–6), in which the ‘Inferno’ movement occupies a modally inflected D minor, which the entry into paradise exchanges for B major. These strategies are obviously mitigated by circumstantial factors in Berlioz’s case (the work’s occasional function) and by Liszt’s programmatic inclination: classical forms are submerged at best, and the movement plans pay only lip service to generic movement types. Liszt’s Eine Faust-Symphonie owes more to the classical model; its key scheme is concomitantly less radical.

Symphonies written between 1850 and 1900 generally evince the burgeoning expansion of tonal means. By the mid-century, a clear preference for third-based schemes was emergent. Gade’s Symphony No. 5 (1852) is organised around the ascending major-third cycle d–F sharp–B flat–D. Joachim Raff’s Symphony No. 5 (1872) adopts a comparable strategy: outer movements in E major and minor frame an A-flat slow movement and a C major march. Raff revisited this idea in his Symphony No. 10, Zur Herbstzeit, the third work in his symphonic tetralogy ‘The Seasons’ (1877–83). Here, the overall trajectory is from F minor to F major, but this is balanced by an A minor Scherzo and a C-sharp minor slow movement. In Symphony No. 8 (Frühlingsklänge) he turned instead to minor-third relations, contrasing the global tonic A with a slow movement in C major. Brahms positioned symmetrical major-third relations either side of the tonic in his Symphony No. 1 (1862–76), and in No. 4 (1885) extended the tendency for minor-key symphonies to tonicise VI in their slow movements to the Scherzo as well, creating a large submediant interior framed by the tonic minor. In Symphony No. 3 (1883), he experimented instead with modal mixture, framing an internal mixture on the dominant (C–c) within an encompassing mixture on the tonic (F–f). Bruckner was at least as ambitious after 1872. The Adagio of Symphony No. 3 (1873, revised 1877 and 1889) tonicises ♭II, the first such relation in Table 10.1 after the Scherzo of Spohr’s Symphony No. 5. Bruckner revived this practice fourteen years later in the Adagio of Symphony No. 8 (1887, revised 1890), a manoeuvre reflecting the harmonic detail of the work’s opening theme. Brahms’s strategy of pairing inner and outer movements in his symphonies nos. 3 and 4 is prefigured in Bruckner’s No. 5, where the tonic outer movements frame interior movements in the mediant minor. Dvořák’s schemes are on the whole less exploratory, with two marked exceptions: Symphony No. 3 (1873) contains a slow movement in ♯vi; No. 9’s slow movement (1893) tonicises ♭VII.

Russian symphonists could be equally adventurous. Borodin, Balakirev and Rimsky-Korsakov all experimented with semitonal pairings: Borodin’s Symphony No. 1 (1867) pits a D major slow movement against an overall E-flat tonality; Balakirev’s Symphony No. 1, begun in 1864 and revised between 1893 and 1897, adopts the same idea in the context of C major; and Rimsky-Korsakov’s Symphony No. 3 (1866–73, revised 1886) pairs a ♭III Scherzo with a slow movement in III. All three composers also employed third relations in interesting configurations. Most remarkable is Balakirev’s Symphony No. 2, completed in 1908, which arranges minor thirds either side of the tonic D minor in the inner movements, such that a tritone obtains between the Scherzo and slow movement (b–F). Balakirev’s strategy is anticipated in part in Borodin’s Symphony No. 2 (1876), which applies the b–F tritone between first movement and Scherzo, although Borodin does not pursue the symmetry of Balakirev’s design, instead supplying a slow movement in D flat. The schemes of Tchaikovsky and Glazunov are, in comparison, relatively tame. Tchaikovsky does not venture beyond the submediant (in the slow movement of No. 1, the ‘Alla tedesca’ of No. 3 and the third movement of No. 6) and the lowered leading note (in the Waltz of No. 5); Glazunov’s most daring scheme appears in his Symphony No. 3 (1890), where an F major Scherzo and C-sharp minor slow movement contrast the prevailing D major tonality.

Balakirev’s use of the tritone signals a point of maximum remove from the fifth-based schemes of the high-classical symphony, which later symphonists also investigated. Prominent in this respect are Mahler’s Symphony No. 6 and Elgar’s No. 1, both of which centre the tritone opposition on the slow movement. Mahler embeds an E-flat major Andante within a global A minor. In the Symphony’s first version, this movement was located third, establishing a direct link between its E-flat ending and the Finale’s opening, which begins in C minor and pivots back to A minor in bar 9. The tritone is more starkly exposed in the final printed edition, which reversed the order of the inner movements, thus isolating E flat between the A major ending of the first movement and the A minor of the Scherzo (the early ordering is given in Table 10.1). In Elgar’s Symphony No. 1, the A♭ tonic of the first movement and Finale is, as we have already seen, contested by an inclination towards D, which is fulfilled by the Adagio’s tonicisation of D major. Elgar’s structure is more complex than Mahler’s: Mahler’s global tonic is grimly maintained in the first movement, Scherzo and Finale; Elgar’s tonic is in question until the very end, and its distance from D major is mediated by the Scherzo, which tonicises F-sharp minor.

At the same time, Mahler also standardises the progressive tonal scheme, a practice that other composers generally restricted to overtly programmatic works (Rimsky-Korsakov’s Antar, for instance, which begins in f sharp and ends in D flat). Five of Mahler’s nine symphonies begin and end in different keys. Symphony No. 2 has the most conservative scheme, exchanging its severe initial C minor for E-flat major at the work’s conclusion. Later on, he favours two strategies. Symphonies nos. 4 and 7 employ third relationships. Symphony No. 4 begins its Finale in the first movement’s tonic of G major, only consolidating the movement’s concluding E major in the final section. Symphony No. 7, in contrast, never returns to the first movement’s E minor, and C major is boisterously asserted from the outset in the Finale, despite foreground interjections from E major. Mahler’s second strategy is the semitonal scheme, which has two contrasting applications: Symphony No. 5 journeys from C-sharp minor to D; No. 9 travels in the opposite direction, depressing the first movement’s D major to D flat in the closing Adagio. As Christopher Lewis noted, these schemes have much in common with the notion of ‘expressive tonality’ that Robert Bailey describes in Wagner’s Ring cycle: the semitonal pairing of keys, where ascent has positive and descent negative connotations.23

It is worth stressing that the two dimensions addressed in this chapter are not always correlated: exploration of chromatic inter-movement schemes in a symphony is not necessarily a reflection of intra-movement chromatic strategies. Thus the minor-third cycle in the first movement of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4 sits within an essentially conventional movement-cycle scheme, which proceeds from i to I via iv. In contrast, the major-third cycle underpinning the movement succession in Brahms’s Symphony No. 1 does not reflect its application within the movements: the exposition in the first movement favours a i–III–iii plot, which remains within the tonic minor or major in the recapitulation; the slow movement contrasts I and vi; as already noted, the third movement contrasts I and ♮II (A flat and B major); and the Finale’s exposition follows the three-key plan I–V–iii, which is modified to I–i in the recapitulation before the coda reasserts the tonic major. On other occasions, a much closer affiliation between intra-movement tonal plot and inter-movement tonal scheme is evident. The B-flat tonality of the Adagio of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 surely reflects the choice of that key for the second group in the first movement’s exposition. Several commentators have noted the influence of the semitonal structures embedded in the opening theme of the first movement of Bruckner’s Symphony No. 8 on the overall scheme, especially the ♭II–i relationship between the Adagio and its surrounding movements (I have addressed this issue briefly in Chapter 1).24 And Mahler’s progressive schemes frequently prefigure their conclusive tonalities in earlier contexts. The serene E major ending of Symphony No. 4 is pre-empted by that key’s startling, unprepared intervention before the coda of the slow movement (Fig. 12), where it interrupts the apparently stable G major tonic. More substantially, the framing D major tonality of Symphony No. 5’s second part (movements 3–5) is presaged in the A minor second movement, where it intervenes as a characteristically Mahlerian ‘breakthrough’ between figs. 27 and 30.

Conclusions

The practices explored here connect with many of the broader formal, historical and aesthetic matters addressed elsewhere in the Companion. The use of chromatic relationships both within and between movements often serves expressive ends, which are bound up with manifold literary, poetic and philosophical aspirations, and closely dependent on the importing of idioms between genres. In the later century especially, symphonists had to negotiate not only Beethoven’s legacy, but also Wagner’s; and this meant acknowledging both Wagner’s cultural-political agendas and his tonal practice, especially as developed in Tristan. This inevitably entailed cross-generic fertilisation: tonal practices evolving in music drama were put to work in the symphony.25

Ambiguity is invariably the critical pivot between tonal means and expressive ends. The displacement of the dominant, competition between non-tonic structural keys, the dislocation of bass progression and formal function, and the elaboration of double-tonic and progressive schemes all generate structural ambiguity of a kind that was alien to the classical symphony. This constituted a central technical means for conveying the narrative and philosophical ideals outlined in Chapter 1: the so-called ‘struggle–victory plot’ embodied in Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 and the utopian aspiration that goes with it is facilitated by the maintenance of structural ambiguity.

Notwithstanding important studies of isolated works or the habits of individual composers, however, research into both nineteenth-century symphonic tonal strategy and its extra-musical connotations remains in many respects in its infancy. In some ways, developments in musical scholarship are propitious for a change in this situation. The ideas propounded by Robert Bailey in the 1970s and 80s have been applied productively in a symphonic context (notably by Christopher Lewis in relation to Mahler); the marriage of this work with the neo-Riemannian and transformational theories evolving since the early 1990s, which have invariably taken nineteenth-century practice as their point of orientation, bodes well for symphonic analysis. Although analyses of whole instrumental movements from this perspective are as yet relatively rare (Cohn’s study of Schubert’s D 960 is an honourable exception), it nevertheless offers the possibility of large-scale assessment of symphonic tonality from a fresh theoretical point of view.26

In other respects, circumstances are not so conducive. The methodological conditions prevailing in the aftermath of the musicological disputes of the 1990s, particularly the critique of ‘formalist’ analysis and concomitant attempts to marry musicology with post-structuralist philosophy and critical theory, have produced a situation that broadly favours the study of texted music and especially opera. As a result, whilst the social and aesthetic contexts of the nineteenth-century symphony have received thorough attention, analytical study has comparably languished. It is hoped that this chapter makes plain the scope of the work that remains to be done in this field, both in terms of the sheer range of the repertoire that awaits investigation and the diversity of practices it exhibits.

Notes

1 Choron uses the term to define the arrangement of dominant and subdominant about the tonic in the practice of his time; see , ‘Sommaire de l’histoire de la musique’, in and , Dictionaire historique des musiciens, artistes et amateurs, morts ou vivants, vol. I (Paris, 1810–11), xxvii–xxix , trans. by as ‘Summary of the History of Music’, in Dictionary of Music from the Earliest Ages to the Present Time (London, 1825). On this subject, see also , ‘Tonality’, in , ed., The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory (Cambridge:, 2002), 726–52 and , ‘Choron, Fétis and the Theory of Tonality’, Journal of Music Theory, 19/1 (1975), 112–38.

2 For a concise summary of the development of instrumental technologies after 1800, see , Instruments in the History of Western Music (London, 1978), 201–73. For a study of nineteenth-century tonality positing a direct link between the adoption of equal temperament and the increased use of chromatic key relationships, see Gregory Proctor, ‘The Technical Basis of Nineteenth-century Chromatic Tonality’ (Ph.D. diss., Princeton University, Reference Proctor1978).

3 Blühmel and Stölzel first patented the valve mechanism for the French horn in 1818; the valve trumpet became common in orchestras from the mid-nineteenth century onwards. See Geiringer, Instruments in the History of Western Music, 241–3 and 251.

4 See , Nineteenth-Century Music, trans. J. (Berkeley:, 1989), 152–60.

5 , Sonata Forms (New York and London, 1980), 309–10.

6 In Der freie Satz, for instance, Schenker explained such chromatic third relations in terms of middleground mixture. See Free Composition, vol. I, trans. (New York, 1979), 40–1.

7 , ‘The Structure of the Ring and Its Evolution’, 19th-Century Music, 1 (1977), 48–61, and ‘An Analytical Study of the Sketches and Drafts’, in , ed., Wagner: Prelude and Transfiguration from Tristan und Isolde (New York, 1985), 113–48, and see also , Tonal Coherence in Mahler’s Ninth Symphony (Ann Arbor, 1984), and , eds., The Second Practice of Nineteenth-Century Tonality (Lincoln, 1996), and more recently , ‘The End of Die Feen and Wagner’s Beginnings: Multiple Approaches to an Early Example of Double-Tonic Complex, Associative Theme and Wagnerian Form’, Music Analysis, 25/3 (2006), 315–40.

8 On the plot/structure distinction, see Lewis, Tonal Coherence in Mahler’s Ninth Symphony, 3.

9 This literature originates with the work of , especially Generalised Musical Intervals and Transformations (repr. New York and Oxford, 2007), and favours broadly algebraic or geometric perspectives, drawing on Hugo Riemann’s concept of the Tonnetz, for example as elaborated in ‘Ideen zu einer “Lehre von den Tonvorstellungen”’, Jahrbuch der Bibliothek Peters (1914–15), 1–26. Important contributions include: , ‘Maximally Smooth Cycles, Hexatonic Systems and the Analysis of Late-Romantic Triadic Progressions’, Music Analysis, 15 (1996), 9–40, ‘Neo-Riemannian Operations, Parsimonious Trichords and Their Tonnetz Representations’, Journal of Music Theory, 42/1 (1997), 1–66, ‘Introduction to Neo-Riemannian Theory: A Survey and a Historical Perspective’, Journal of Music Theory, 42/2 (1998), 167–79, ‘As Wonderful as Star Clusters: Instruments for Gazing at Tonality in Schubert’, 19th-Century Music, 22/3 (1999), 213–32, and Audacious Euphony: Chromaticism and the Triad’s Second Nature (New York and Oxford, 2012); , ‘Re-imag(in)ing Riemann’, Journal of Music Theory, 39 (1995), 101–38; , Chromatic Transformations in Nineteenth-Century Music (Cambridge2002); , Tonality and Transformation (New York and Oxford, 2011); , The Geometry of Music: Harmony and Counterpoint in the Extended Common Practice (New York and Oxford, 2011).

10 See Cohn, ‘Introduction to Neo-Riemannian Theory’, 167–9.

11 Cohn, ‘As Wonderful as Star Clusters’.

12 See Cohn, ‘Maximally Smooth Cycles, Hexatonic Systems and the Analysis of Late-Romantic Triadic Progressions’, 9 and 34. Cohn refers to Dahlhaus, ‘Wagner, Richard’, in , ed., The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, vol. XX (London, 1980), 123.

13 See Kopp, Chromatic Transformations in Nineteenth-Century Music, esp. 1–17.

14 See and , Harmony and Voice Leading (Belmont, 2003), 612.

15 Bailey defines the double-tonic idea as ‘the pairing together of two tonalities . . . in such a way that either triad can serve as the local representative of the tonic complex. Within that complex, however, one of the two elements is at any moment in the primary position while the other remains subordinate to it.’ See ‘An Analytical Study of the Sketches and Drafts’, 121–2.

16 On Bruckner’s harmonic idiom, see for example , ‘Bruckner and Harmony’, in , ed., The Cambridge Companion to Bruckner (Cambridge, 2004), 205–28.

17 For a recent account of this matter, see , ‘A Nice Sub-Acid Feeling: Schenker, Heidegger and Elgar’s First Symphony’, Music Analysis, 24/3 (2005), 349–82.

18 The term ‘progressive tonality’ was first coined in , Bruckner, Mahler, Schoenberg (New York, 1947).

19 On Chopin’s progressive tonality, see , ‘Alternatives to Monotonality in Early 19th-Century Music’, Journal of Music Theory, 25/1 (1981), 1–16 and , ‘Chopin’s Alternatives to Monotonality: A Historical Perspective’, in and , eds., The Second Practice of Nineteenth-century Tonality (Lincoln, 1996), 34–44.

20 For a contrasted reading of this movement, which views the second-theme reprise as a retransition, see , ‘Success and Failure in Mahler’s Sonata Recapitulations’, Music Theory Spectrum, 33/1 (2011), 37–58, esp. 46–8.

21 The concept of rotation is seminally broached in , Sibelius: Symphony No. 5 (Cambridge, 1993), 23–6. It is theorised extensively with respect to the classical sonata in and , Elements of Sonata Form: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York and Oxford, 2006), 611–14, where the following definition is offered: ‘Rotational structures are those that extend through musical space by recycling one or more times . . . a referential thematic pattern established as an ordered succession at the piece’s outset’ (p. 611). For a critique of this idea, see , ‘Beyond “Norms and Deformations”: Towards a Theory of Sonata Form as Reception History’, Music Analysis, 27/1 (2008), 137–77. For a recent analysis of the first movement from the perspective of sonata theory, see , ‘Mahler’s Third Symphony and the Dismantling of Sonata Form’, in , ed., Keys to the Drama: Nine Perspectives on Sonata Form (Aldershot, 2009), 53–72. Again, Monahan reads this movement differently, regarding the D minor march as an introduction and the music from bar 247 as initiating an embedded continuous exposition in F major, which is retrieved with the recapitulation of the march from bar 737. See ‘Success and Failure in Mahler’s Sonata Recapitulations’, 48–50.

22 Clementi’s late symphonies survive only as fragments, which have been reconstructed by Alfredo Casella (nos. 3 and 4) and Pietro Spada (nos. 1 and 2). On this matter, see for instance , ‘Clementi as Symphonist’, Musical Times, 120/1633 (1979), 207 and 209–10.

23 See Bailey, ‘The Structure of the Ring and Its Evolution’, 51 and see also Lewis, Tonal Coherence in Mahler’s Ninth Symphony.

24 On the large-scale implications of the harmonic orientation of the first movement’s main theme in Bruckner’s Symphony No. 8, see William E. Benjamin, ‘Tonal Dualism in Bruckner’s Eighth Symphony’, in Kinderman and Krebs, eds., The Second Practice of Nineteenth-century Tonality, 237–58 and also , Bruckner’s Symphonies: Analysis, Reception and Cultural Politics (Cambridge, 2004), 135–43.

25 The early twentieth-century discourse on Bruckner was particularly heavily invested in this issue, even to the extent of regarding his symphonies as the ultimate synthesis of Bachian counterpoint, Beethovenian form and Wagnerian harmony. See for example , Von zwei Kulturen der Musik (Stuttgart, 1947) and Die Symphonie Anton Bruckners (Munich, 1923), and most famously , Bruckner, 2 vols. (Berlin, 1925).

26 For a substantial engagement with the problems of applying recent harmonic theory to the late nineteenth-century symphonic repertoire, see Miguel J. Ramirez, ‘Analytic Approaches to the Music of Anton Bruckner: Chromatic Third Relations in Selected Late Compositions’ (Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago, Reference Ramirez2009).