12 Symphony/antiphony: formal strategies in the twentieth-century symphony

To a greater extent than almost any other musical genre, symphonies are concerned explicitly with the musical representation of time and space. A simple etymology of the word points towards this preoccupation – the idea of ‘sounding together’ implies both the projection of sounds in/through space and the simultaneity of their presentation. Beyond a work’s linear unfolding through time in performance, it is this sense of bringing things together which helps to shape and colour the symphony’s particular structural and expressive tensions. Yet the single defining feature of the twentieth-century symphony is the extent to which these categories of time and space have become increasingly contested and contingent. This sense of the symphony’s provisional status is partly an issue of ideology – the symphony is anything but a neutral genre, and it carries into the twentieth century perhaps the greatest ideological baggage of any large-scale musical form. Associations of heroic masculine endeavour, musical tautness and abstraction, and the myth of the ‘profound logic’ which Sibelius supposedly promulgated in his apocryphal conversation with Mahler have remained stubbornly pervasive a century later,1 even though such models of symphonic expression and design have been the subject, for many critics and composers, of intense resistance and critique. For some, the twentieth-century symphony has simply run out of time and space – as an outmoded and historically anachronistic art form, the unwanted vestige of a hierarchic and bourgeois concert culture, as an unaffordable luxury in an age of economic hardship, or as a musical institution whose nineteenth-century associations of community, unity and synthesis can seem unrealistically idealistic and unattainable.2 For others, the symphony has served as a means for cultural-political expansion – a powerful history can be traced of the musical geography of the twentieth-century symphony, which locates the genre at the heart of wider debates correlating notions of time and space with freedom of expression and self-determination.3 Simply ‘sounding together’ has not always been an easy or politically straightforward task, and the idea of community that the symphony has often seemed to elevate can swiftly become more exclusive than inclusive. In that sense, as Theodor W. Adorno perceived, the symphony potentially projects forwards its own sense of negative teleology, of a forceful gathering together that is as much concerned with the negation of time and space – and the implied collapse of a liberal enlightenment world view – as with the democratic celebration of diversity and brotherhood.4

But this shifting sense of symphonic time and space also underlines a broader philosophical shift in which music has played a component part. In his rich and provocative history of early twentieth-century modernism, The Culture of Time and Space, 1880–1918, Stephen Kern dwells on the impact that technological innovations in mass media and communication had upon the understanding and perception of passing time and spatial relationships.5 Such essentially scientific projects had enormous implications for the performance and dissemination of music. It would be impossible, for instance, to conceive of a history of the twentieth-century symphony that did not at least acknowledge the fundamental importance of radio, or gramophone recording, for the development of the genre,6 and a significant later strand for the elaboration of symphonic music can be traced through the Hollywood film score. Yet perhaps the true significance of these developments, as Kern notes, lies in the way in which they changed the nature of time and space themselves. After the advent of radio broadcasting, time and space were no longer understood as fixed, discrete entities – as transcendental Kantian categories that lay beyond the boundaries of individual or collective intervention – but rather emerged as more complex, fluid domains. Henri Bergson, for instance, wrote in his seminal text Matter and Memory (1896) about the permeability of memory and perception, and argued that the experience of time was properly a process of active (but unconscious) recollection that collapsed past, present and future into a single, multi-layered flux, an idea that appealed to novelists such as Marcel Proust and James Joyce, whose work abandoned linear narrative structure in favour of a more fractured, fragmentary and self-reflective commentary. The twentieth-century symphony often becomes novelistic – or cinematic – in precisely that sense. The collective utterance whose unity and linear authority is upheld as the apotheosis of the nineteenth-century work is here replaced by a multi-vocality, a large-scale expressive and structural counterpoint of different temporalities and musical spaces, the diversity of which becomes, for Adorno’s Mahler, a mirror of the modern world.

The title of this chapter, borrowed from one of the works discussed below, refers to this modernist twentieth-century symphonic context. ‘Symphony/antiphony’ is a deliberately provocative starting point. It can be read as an antagonistic opposition, as a form of dialogue (question and answer), or as an unstable synergy of multiple voices or musical characters. It supports the idea that the twentieth-century symphony is somehow in terminal decline (a belief that was arguably more prevalent at the start of the century than at its conclusion), and illuminates the way in which, paradoxically, the symphony has continued to regenerate itself through resistance and artistic renewal. But it also provides an insight into the formal strategies that these works adopt, particularly the way in which they negotiate shifting definitions of symphonic space and time. Though the survey is necessarily narrow and omits important streams of symphonic composition purely for reasons of economy, it examines a number of paradigmatic approaches to the problems of rearticulating symphonic time and space. For Sibelius, for example, time and space are emergent properties. His works evoke the feeling of an immeasurably distant past, out of which music seemingly evolves in a constant process of transformation and growth. The primary structural tension in Sibelius’s symphonies is created by the disjunction between this growth and the music’s strongly goal-directed tendency, which often involves the attainment of a definitive moment of harmonic arrival as an end-in-itself or vanishing point. For Stravinsky, in contrast, time and space in the Symphony of Psalms are frozen in a ritualistic theatre that, as Richard Taruskin has noted, points both to Stravinsky’s inherited ‘Russian traditions’ and to the modernist Parisian ideas of objectivity, alienation and distance with which the composer later sought to associate himself.7Luciano Berio’s Sinfonia is similarly ritualistic, but his music arguably comes closest to the Bergsonian model of perception as a complex melding of past, present and future in a single flux or stream of consciousness. It is no coincidence that James Joyce and Samuel Beckett are amongst Berio’s literary points of correspondence. Elliott Carter’s Symphony of Three Orchestras is a powerfully intense evocation of a new musical world – both literally and figuratively, its gestures are motivated by the sense of an American soundscape, one which positively seeks to move away from European legacies and traditions, even while, characteristically, the work reveals its own inner fears and anxieties. The spiralling musical fantasies of Carter’s work inspire thoughts of obliteration as much as liberation or escape. The concluding work, Danish composer Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen’s Symphony, Antiphony, is a forceful deconstruction of the genre, a knowing and allusive game with the shattered fragments and shards of the symphonic tradition refracted through a late twentieth-century critical lens. It offers no summative vision – as the title suggests, the work stubbornly insists that there are two sides to every symphonic story. But, at the very least, Gudmundsen-Holmgreen’s work is a powerful testimony to the continued creative energy of the genre, and a vivid affirmation of the symphony as progressive and cutting-edge.

Sibelius: Symphony No. 4

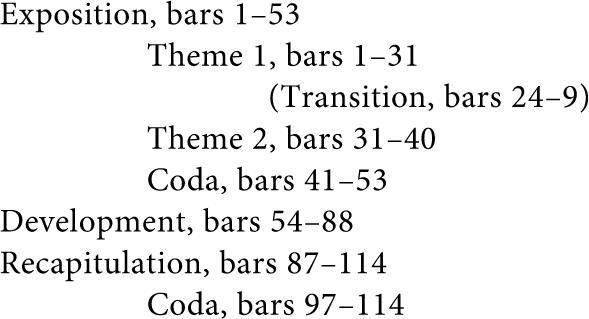

Each of the works considered below challenges the temptation to regard the symphony as a conservative or retrospective form. This is especially true of Sibelius’s Fourth Symphony (1909–11). Commentators widely agree that the work is the most ‘difficult’ and outwardly modernist of Sibelius’s symphonies. The Fourth is traditionally seen as a stylistic turning point, away from the expansive late-Romantic panorama of the first two symphonies and the crisp Junge Klassizität of the Third, towards a more austere, modernist mode of utterance. But the work also readily reveals Sibelius’s concern with fundamental elements of symphonic thought and design: particularly with notions of monumentality (here expressed in remarkably telegrammatic form); development (energetically foregrounded throughout and often privileged over explicit thematic statement or exposition); and the tension between the idea of the symphony as a large-scale public statement and as an inward personal confession. The first movement (Tempo molto moderato, quasi adagio) is exemplary in its concern with the implications of modal mixture for the articulation of large-scale structure. The formal outline of the movement has prompted considerable scholarly debate. Elliott Antokoletz, for example, identifies a ‘Sonata Allegro’ design, aspects of which correspond with the thematic elements of a rounded binary structure (Fig. 12.1).8

Figure 12.1 Sibelius, Symphony No. 4, I, formal reading (after Antokoletz, ‘The Musical Language of the Fourth Symphony’)

As Antolkoletz readily acknowledges, a number of anomalies immediately arise, which challenge this ‘Sonata Allegro’ reading. The proportions of the individual sections in the plan are highly asymmetrical – there is a strong sense of telescoping towards the final paragraph, so that the feeling of balanced symmetry characteristic of normative rounded binary forms is replaced by an urgent sense of goal direction, only to dissipate and atomise in the very final bars. Furthermore, the recapitulation at bar 87 is highly irregular. Even by early twentieth-century standards of formal syntax, the sense of return is extremely attenuated, and the re-entry of previous material is carefully dovetailed so that the precise moment of reprise is almost impossible to determine. Even the identification of first and second subject groups in Antokoletz’s chart becomes problematic – the first part of the exposition, for example, is characterised by a rich tapestry of overlapping motivic fragments, none of which emerge sufficiently prominently to gain the status of a thematic sentence in the Schoenbergian sense. And finally, the tonality remains highly unstable throughout – the only genuine sense of harmonic arrival is achieved in the two coda sections, at bars 41 and 97, which provide the strongest point of formal return in the whole movement. In contrast, the opening of the exposition and development are tonally ambiguous – sustained examples of what Schoenberg termed wandering (or ‘vagrant’) harmony where the music barely suggests any fixed point of tonal orientation. An alternative formal reading of the first movement has therefore been suggested by commentators such as Tim Howell and Veijo Murtomäki,9 which breaks the music down into two parallel strophes: the first in bars 1–53, ending with a large-scale cadence on F♯; and the second in bars 54–114, closing with a cadence on A. This simpler binary model hears both strophes as goal-directed, progressing from a state of harmonic and textural instability towards provisional moments of cadential articulation, which in turn become the primary points of structural focus.

Local details support this interpretation of the movement’s design. The opening gesture is a gloomy textural and harmonic birth. Sibelius’s evocative low scoring (cellos, basses, bassoons) creates a dark sonic foundation, resonant with upper harmonic partials, from which the full orchestral timbre slowly emerges and brightens. The first four bars articulate the movement’s principal motivic idea ((![]() ), (0 2 4 6) or pitch class set [4–21]), a harmonically ambiguous device that suggests both C Lydian (with emphasis on the sharpened fourth degree of the scale, F♯) and the first four notes of the whole-tone scale (collection I) (see Example 12.1).

), (0 2 4 6) or pitch class set [4–21]), a harmonically ambiguous device that suggests both C Lydian (with emphasis on the sharpened fourth degree of the scale, F♯) and the first four notes of the whole-tone scale (collection I) (see Example 12.1).

Example 12.1 Sibelius, Symphony No. 4, I, bars 1–4.

This process of textural and timbral growth is strengthened by the entry of the solo cello (as bardic orator, perhaps?) in bar 6, harmonically suggesting an unstable A melodic minor/dorian collection – the slow, oscillating bass ostinato is now heard as ![]() , effectively underpinning the cello cantilena with a dominant pedal. The gradual entry of the full string group, in a sonorous ‘chorus’ effect, begins to fill out this modal A minor collection, but the viola’s D♭ in bar 17 is a ‘blue’ note, and triggers a local octatonic/E-flat minor inflection that begins to cloud the music’s earlier A orientation. The descending steps in the bass in bars 24–5 finally suggest that the movement is beginning to approach its first point of cadential arrival – on C Lydian, resolving the ambiguity of the opening motto. At the last second, however, the gesture is undermined by the chromatic intrusion of C♯, an enharmonic transformation of the viola’s D♭ from bar 17. This pitch now acts as a decisive harmonic pivot, turning the music’s tonal allegiance away from A (see Example 12.2).

, effectively underpinning the cello cantilena with a dominant pedal. The gradual entry of the full string group, in a sonorous ‘chorus’ effect, begins to fill out this modal A minor collection, but the viola’s D♭ in bar 17 is a ‘blue’ note, and triggers a local octatonic/E-flat minor inflection that begins to cloud the music’s earlier A orientation. The descending steps in the bass in bars 24–5 finally suggest that the movement is beginning to approach its first point of cadential arrival – on C Lydian, resolving the ambiguity of the opening motto. At the last second, however, the gesture is undermined by the chromatic intrusion of C♯, an enharmonic transformation of the viola’s D♭ from bar 17. This pitch now acts as a decisive harmonic pivot, turning the music’s tonal allegiance away from A (see Example 12.2).

Example 12.2 Sibelius, Symphony No. 4, I, bars 7–21.

The entry of the brass chorale in bars 29–39 reinforces this shift of harmonic allegiance with a new timbral colour, dynamic contour and rhythmic profile. The initial (0 2 4 6) motive returns in transposed form: [A-B-D♯-C♯], bars 31–2, and the cadence on F♯, with its strong plagal colouring, is an obvious tonicisation of this pitch from the opening page. The coda, bars 41–53, is an echo or afterglow of this moment of harmonic arrival. Even here, however, the music’s radiant F-sharp major is clouded by the presence of the sharpened fourth degree (B♯), an enharmonic reference to the C♮ pole of the opening bars.

The insistence of this tritone opposition (C♮-F♯) initiates and underpins the development. The passage begins with complete textural and thematic liquidation, music reduced to spare single lines, motivic fragments and harmonic obscurity in an extreme reinterpretation of classical developmental technique. From this sense of a blank musical void, the movement begins to replay the process of growth from the opening paragraph. The return of the solo cello at bar 57 is a pointed reference to its earlier bardic role in bar 6. The tonal organisation of the passage, soon picked up by the upper strings, is a complex mix of octatonic and whole-tone collections: the music becomes increasingly whole-tone as it approaches its registral ceiling around bar 70. Although this whole-tone bias clouds any sense of tonal centricity, it does succeed in recalling the principal motive in its original form – initially as part of the dusky string figuration in bar 72, and then, in augmentation, in the flute and clarinet. The return of the principal motive marks the start of a gradual process of textural accumulation, reinforced by attempts to assert A as a definitive tonal goal (for example, the timpani entry in bar 77). This sense of imminent tonal arrival is motivated primarily by a rising chromatic bass movement – from the F♯ in bar 76 (a reference, of course, to the end of the exposition space), through G♮ in bar 82 and A♭ in bar 85. The final attainment of A♮ in the bass coincides with the restatement (for the first time) of the principal motive at its original pitch level (C-D-F♯-E; see Example 12.3).

Example 12.3 Sibelius, Symphony No. 4, I, bars 95–6.

The key difference from the opening, however, is that on this occasion the motive has been harmonically contextualised so that it now establishes A unequivocally as the movement’s tonal destination. With this task achieved, the return of the brass chorale in bar 96 serves as a solemn benediction, a hymn-like affirmation of A major’s tonic status. But even here, elements of instability remain. As the music fades into silence, the intrusion of C♮s in bar 110 recalls earlier moments of chromatic interruption (ironically, C♮ was precisely the note withheld at a previous point of disjunction in bar 27). The movement briefly unfolds a whole-tone collection once again (bars 110–11; [C♮-D-E-F♯-B♭]), before pointedly resolving the B♭s down to A♮. Yet closure is once again evaded: the following movement begins by reinterpreting the whole-tone set of the preceding bars as a chromatically altered V7/F, and the solo oboe takes up the first movement’s closing a♮2, transforming a closing cadential gesture into the start of a new melodic curve (see Example 12.4).

Example 12.4 Sibelius, Symphony No. 4, II, opening.

The first movement of Sibelius’s Fourth adumbrates a number of formal strategies and concerns that preoccupy much of his later music. The first is the thorough reconfiguring of received Formenlehre categories: though the movement suggests elements of a rounded binary form or two-part structure, it is in no sense a normative ‘sonata allegro’. Second, the Tempo molto moderato exemplifies the characteristically Sibelian process of what James Hepokoski calls the ‘interrelationship and fusion of movements’:10 the elision of the final bars means that the Scherzo becomes a giant pendant to the first movement, amplifying, elaborating and subsequently condensing its tonal drama. Third, the movement’s manipulation of time and space becomes paradigmatic for later symphonic designs. As Edward Laufer has suggested in his Schenkerian reading, the Tempo molto moderato is a symbolic journey, ‘a struggle to victory, from darkness to light, from nothingness to life, or from turmoil to serenity (somehow all the same poetic idea)’;11 yet it is also a mythic transformation, from the ambiguity of the opening page to the crystallisation of the closing bars. The music articulates its own process of coming-into-being, the sounding manifestation of a creative will through a painful process of musical birth that unfolds a bleak new symphonic soundscape.

Stravinsky: Symphony of Psalms

As James Hepokoski has compellingly demonstrated, similar issues of growth, fusion and teleology motivate the formal design of Sibelius’s Fifth Symphony (1914–15; rev. 1916 and 1919). Here, the opening bars of the first movement articulate a ‘misfired’ cadence in E flat, whose chromatic slippage generates the more complex modulatory scheme of the music that follows. Much of the remainder of the Symphony is dedicated to reassembling the intervallic and functional harmonic components of this initial cadential gambit, crystallising, as Hepokoski shows, in the swinging bell-like ‘swan hymn’ in the Finale. The stratified polymetric structure of the swan hymn texture is remarkable: the music unfolds in several different temporal and registral layers through elaboration of the opening gesture’s cadential fourths and fifths (see Example 12.5).

Example 12.5 Sibelius, Symphony No. 5, IV, ‘swan hymn’.

A remarkably similar texture unfolds in the final pages of Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms (1928–30). Stravinsky had already radically recalibrated the idea of symphonic structure (after an early student exercise, the Symphony in E flat), in his Symphonies of Wind Instruments (1918–20). Aspects of the Symphonies of Wind Instruments superficially resemble the musical language of the opening movement of Sibelius’s Fourth: the tendency to break the ensemble down into craggy instrumental groups; a fondness for bell-like attacks in the woodwind and brass; and the block-like design of the work. Yet the two works are strikingly different in more obvious ways. The Symphonies of Wind Instruments resists any sense of organic growth or evolution in favour of what Alexander Rehding has termed its ‘logic of discontinuity’: the abrupt juxtaposition of contrasting statements of musical material that do not appear to evolve or transform, but simply rotate through rhythmic or pitch cycles mechanically even as they converge on C as tonal centre in the final pages.12 The Symphony of Psalms obviously builds on the earlier precedent of the Symphonies of Wind Instruments in its preference for sharp juxtapositions, block form and rapt, ritualistic circularity. In part, these qualities are demanded by the work’s text, taken from Psalms 38 (verses 13 and 14), 39 (verses 2, 3 and 4) and 150 (complete): the Symphony is correspondingly divided into three movements, arranged in an ascending hierarchical order. The first movement is an invocation, a prayer of supplication (‘Exaudi orationem meam, Domine’: ‘Hear my prayer, O Lord’); the second movement is a giant double fugue, an intercession for forgiveness and salvation that results in a ‘new song’ (‘Et immisit in os meum canticum novum’: ‘And he hath put a new song into our mouth’); the third movement is a hymn of praise (‘Laudate Dominum’: ‘Praise the Lord’), whose closing pages intone the ‘new song’ born in the second movement. The Symphony is thus a glowing affirmation of faith, conceived on a monumental, public scale. It embraces aspects of its earlier nineteenth-century inheritance (the symphony as a large-scale vehicle for the celebration of community) and also attempts to ground the genre in an earlier tradition (music as the shared ritualistic expression of public and private religious belief).13

These tensions, between different ideas of symphonic time and space, are reflected in aspects of the music’s formal strategy. Much has been written, notably by Pieter van den Toorn, of the first movement’s interaction between different modal collections: predominantly octatonic, but also diatonic (E♭ and C as a binary ‘tonic pair’), Gregorian (E Phrygian), and chromatic.14 The basic opposition of modal materials is adumbrated in the opening bars. The famous ‘Psalms’ chord, with its characteristic registral scoring (E minor with doubled third (G), and no fifth degree), serves a punctuating role throughout, abruptly closing and initiating phrases as though resetting the clock, yet also prefiguring the movement’s final cadence (on G) and establishing the pattern of third relations which predominates throughout. The first appearance of the chord is followed immediately by two arpeggiated dominant seventh chords (B♭7 and G7) drawn from octatonic collection 1, whose diatonic chords of resolution (E flat and C respectively) anticipate the tonal frames of the second movement and Finale. For Wilfrid Mellers, these two tonal centres are more important for their associative symbolic character than for their structural function: ‘the key of E♭ – whose humanistic associations extend from the compassion of Bach and Mozart to the heroism and power of Beethoven – emerges as Man’s key, while C, the ‘white note’ key in the major and E♭’s relative in the minor, becomes God’s key’; the first movement’s (Phrygian) E minor, in contrast, becomes the ‘key of prayer and intercession’.15 Such readings are of course problematic – not least for the ways they threaten to assimilate Stravinsky within an Austro-German humanist tradition to which he was only tangentially related. Yet it is interesting to speculate on the presence of similar key associations in other twentieth-century symphonies: the C major of Sibelius’s Seventh (1924), for example, is no less concerned with notions of the divine (D major often serves a similar purpose for Vaughan Williams, whereas D major means something very different at the end of Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony). And the appearance of diatonic writing in twentieth-century symphonic music more widely often assumes a similarly symbolic role: keys evoked more for their expressive affect than any attempt to reinvoke anachronistic notions of diatonic functionality.

The opening bars of the first movement of the Symphony of Psalms are also paradigmatic in their rhythmic and metrical organisation. The vertical, punctuating syntactic character of the ‘Psalms’ chord is spliced with the circular additive tendencies of the following bars: the division of the octatonic arpeggiation into sub-blocks of 1+2, 1+1 in bars 2–3. The effect of such cross-cutting is to create a basic tension between different forms of metrical structure: the strong vertical downbeat of the ‘Psalms’ chord; and the assymetrical, non-periodic grouping of the arpeggiations. Rather than being synthesised into an organic unity (the illusion of a single, linear vector), rhythmic time is broken into its basic dimensions. Similar processes of rhythmic organisation operate elsewhere in the movement. For instance, the augmentation at Fig. 4 (semiquavers becoming quavers) is reversed at Fig. 6. But the complex layering of metrical streams at Fig. 5 (3/2 in the chorus and bassoons versus 8+10+12/4 in the upper woodwind) gives way to a more static improvisatory feel at Fig. 6 (groups of 8+12+24 semiquavers in the oboe). The local climax of this sequence is the neo-Handelian passage at Fig. 9, whose Zadok-like combination of ostinato patterns in simultaneous semiquaver and quaver figuration generates a sense of intense surface activity while remaining metrically static and statuesque. The return of this passage at Fig. 12 (at the words ‘Remitte mihi’, ‘Spare me’), presages the movement’s short coda and the collision between octatonic and phrygian collections which results in the music’s diatonic cadential descent towards G.

The Finale relies upon similar tensions and cross-cuttings, though on a larger and more expansive scale. By comparison with the first movement of Sibelius’s Fourth Symphony, the basic formal structure of the Finale is easy to read: a rounded binary main section based on C (labelled simply Tempo minim=80, dominated by its motto-like quaver figure, which Stravinsky associated with the repeated phrase ‘Laudate Dominum’ and later, misleadingly, claimed was one of the earliest ideas for the work),16 followed by an extended postlude (for which Mellers invoked Henry Vaughan’s ‘chime and symphony of nature’)17 in E flat, framed by an introduction and coda that grounds the whole movement in C. The third-based structure of Mellers’s tonal pairing is evident throughout: the introduction, for example, superimposes the two centres (the ‘Alleluia’ before Fig. 1), and dwells on the false-relation E♮/E♭ repeatedly, the choir intoning their quiet hymn of praise in E flat while the orchestra insists on a bell-like ostinato in C (see Example 12.6).

Example 12.6 Stravinsky, Symphony of Psalms, III, introduction. © Copyright 1931 by Hawkes and Son (London) Ltd. Revised version: © Copyright 1948 by Hawkes and Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced by permission of Boosey and Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd.

The effect does not suggest dynamic polarisation so much as the insistent rocking between two complementary halves of the same compound harmonic unit. The closing word, ‘Dominum’, comes to rest on C, but the presence of B♭ in the chord before Fig. 3 acts both to destabilise the sense of closure, pushing the music forwards into the start of the faster main section, and also serves as a chromatic residue of the earlier E flat-C major mix. Significantly, in the final cadence at the end of the movement, this element of harmonic doubt is removed.

In her study of pages from the sketches for the Finale, Gretchen Horlacher has shown how Stravinsky began the fast main section of the movement by drafting the stratified ostinato texture at Fig. 3 in full, and then cutting and pasting its component rhythmic layers to disrupt its continuity and create a distinctive metrical counterpoint – the bass riff in 3/4 against the movement’s prevailing 4/4 (a pattern prepared, in fact, by the orchestral ostinato at Fig. 2). Much of the tonal drama in the main section is generated not only by modal interaction but also by the play of sharp- versus flat-side harmonic tendencies: the bright, diatonic effect of the C-based music at the start intensified by its shift towards E at Fig. 5, and then clouded by the cadence before Fig. 6 (principally octatonic collection II). E flat reasserts itself, both at the beginning of the middle section (Fig. 13) and at Fig. 22, where the closing hymn of praise begins. This is the passage that resembles the Finale of Sibelius’s Fifth Symphony: the swinging fifth steps in the bass and polymetrical layering (the bass riff now in four versus the triple-metre choral parts) create a similar suspension of clock time in favour of an ecstatic sense of stillness and infinitude (see Example 12.7).

Example 12.7 Stravinsky, Symphony of Psalms, hymn of praise, opening. © Copyright 1931 by Hawkes and Son (London) Ltd. Revised version: © Copyright 1948 by Hawkes and Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced by permission of Boosey and Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd.

For Taruskin, such textures exemplify Stravinsky’s tendency towards ‘hypostatization’: the coexistence of independent rhythmic strata in a state of perpetual permutation and recycling.18 The two passages also serve parallel structural functions, as goals of their respective symphonic journeys: they represent the moment at which symphonic time and space seemingly dissolve and collapse inwards, for Stravinsky not so much in synchronicity but rather in a more enigmatic simultaneity.

Berio: Sinfonia

Although they share a similar cyclic view of the Symphony, Sibelius and Stravinsky offer very different metaphors of musical birth, transformation, death and renewal. For Sibelius, the process of musical birth is tense and agonistic – the music seemingly evolves organically but is constantly threatened by its own tendency towards collapse and disintegration; the final bars of both Fourth and Fifth symphonies offer little sustained sense of resolution, only provisional points of rest. The closing bars of Stravinsky’s Symphony are more affirmative, perhaps, though they retain their sense of ritualistic anonymity and disembodiment: in the closing bars of the Symphony of Psalms, the grand nineteenth-century idea of symphonic apotheosis becomes radically hollowed out. The life-cycle of Luciano Berio’s Sinfonia (1967–8) is similarly ambivalent: the work unfolds a gradual growth process that repeatedly ends in death and dissolution. The Sinfonia’s musical and textual material is dominated by recurrent symbolic imagery of water, fire, violence and immersion: the image of a cataclysmic drowning is represented several times throughout the work, both through the process of chromatic saturation that floods the outer movements, and in the explicit reference to the drowning scene from Alban Berg’s Wozzeck that forms the apex of the central movement. Famously a musical deconstruction of the Scherzo from Mahler’s Second Symphony, the third movement casts a critical eye on the idea of resurrection (borrowed from the subtitle of Mahler’s work). ‘Rebirth’ here may refer to the Sinfonia’s rich intertextuality – references abound, not only to Mahler, but also to Berlioz, Richard Strauss, Debussy, Stravinsky, Hindemith, Boulez and Stockhausen, alongside scat singing and jazz. But it might also refer to the Sinfonia’s satisfyingly tight cyclic structure: the fifth (and final) movement replays (or ‘resurrects’) the first movement’s transformation from vertical chordal sonorities to an energetic linear texture, and the closing bars recapture the first movement’s own ending (a gesture that itself looks back to the work’s opening). In that sense, the Sinfonia is explicitly circular: like James Joyce’s high-modernist novel Finnegans Wake, a work which forms one of the Sinfonia’s central literary reference points, the music’s end becomes its beginning. But this also points to one of the structuralist games that Berio plays throughout the piece: the idea that, in spite of the constant reference to music beyond the Sinfonia’s boundaries in the third movement, the work’s own meaning remains continually deferred, collapsing back on itself in an endless cycle of reflexivity. So the idea of resurrection becomes inherently problematic, robbed of its original transcendental connotations. The Sinfonia’s seemingly infinite process of re-creation is intimately allied to its own cycle of self-destruction.

David Osmond-Smith has compellingly analysed the Sinfonia’s structure in detail, drawing attention to the design of the five individual movements, and carefully charting the work’s progress through the intertextual montage of the third movement and beyond.19The first movement, for example, is designed around a simple process of symbolic exchange taken from Claude Lévi-Strauss’s structuralist text, Le cru et le cuit (‘The Raw and the Cooked’). Lévi-Strauss’s text concerns two native South American accounts of the origin of fire and water, and the transformation from eau celeste (rain, precipitation) to eau terrestre (lakes, oceans, rivers). This descent (from sky to earth) is mirrored in the movement’s trajectory, which shifts from the gentle pulsating oscillation of two closely overlapping ‘birth’ chords (an eight-note ‘stack’ intervallically constructed from bass fifth and accumulated thirds, and a more resonant four-note set) towards an explosive linear tapestry of sound, the orgiastic celebration of a ‘musique rituelle’ (from Fig. I). The text itself is fragmented and broken apart – the movement begins with open vowel sounds, suggesting a mythic pre-linguistic ululation, from which key symbolic words gradually emerge (‘feu, eau, sang’: ‘fire, water, blood’) as commentary upon the narration of lines from Lévi-Strauss’s account. The alternation of the two opening chords (see Example 12.8) swiftly tends towards saturation – the complete chromatic set is heard as early as Fig. A, though it emerges more forcefully after Fig. I as the ‘musique rituelle’ gains momentum – the movement’s final word is ‘tué’ (‘killed’), a reference to the violent crime that attends the creation of fire/water in Bororo myth, and a link to the following movement, a memorial to the assassinated Martin Luther King.

Example 12.8 Berio, Sinfonia, I, opening.

The second movement is similarly concerned with a process of growth, this time expanding a single melodic line outwards from a basic set (0 2 4 8) through four principal cycles plus an open, incomplete fifth cycle (starting at Fig. E): as Osmond-Smith notes, the melody rapidly begins to suggest two complementary whole-tone collections that generate a more complex harmonic field.20 The sustaining of selected notes of the melody in the orchestra results in a resonant ‘halo’ of sound, so that the melody seemingly weaves its own polyphonic structure as it proceeds. The text similarly weaves itself together, from a series of the five open vowel sounds, until it reconstructs King’s name: the key moment of coordination is the phrase ‘O King’ at the beginning of the final cycle at Fig. E. In the final bar, King’s name is broken into syllables and distributed between the eight individual singers, dissolved once more so that the movement’s growth cycle can begin again.

There is little comparable sense of growth in the third movement: rather, the music whirls around as though in a centrifuge, drawing in and ultimately consuming a range of references to dance movements from the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century orchestral repertoire. In this way, Berio collapses time and space into a single fluid whole: the ‘Danse de la terre’ from Stravinsky’s Le sacre du printemps seemingly coexists alongside the ‘Scène de bal’ from Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique and Mahler’s Scherzo. As Osmond-Smith observes, the Mahler model is already a synthetic intertextual one, containing references both to the trio from Beethoven’s Violin Sonata Op. 96 and the closing bars of ‘Das ist ein Flöten und Geigen’ from Schumann’s Dichterliebe. But Berio provides an additional layer of analysis and commentary via his literary text, drawn from Samuel Beckett’s The Unnameable. Beckett’s text provides ample opportunity for parody and self-reflection: the opening lines of the play (‘Where now’; ‘keep going’; ‘nothing more restful than chamber music’) at the movement’s outset are swiftly echoed by more mocking phrases (‘You are nothing but an academic exercise’; ‘it seems there are only repeated sounds’; ‘no time for chamber music’) and negation (‘hardly a resurrection’, punning on Mahler’s work). At times, Beckett’s work stimulates new unexpected turns in the movement’s course: the sudden interjection of the passage from the slow movement of Beethoven’s ‘Pastoral’ Symphony at Fig. X (appropriately, given Sinfonia’s preoccupation with water imagery, the ‘Scene by the Brook’) is accompanied by the line ‘It’s late now, he shall never hear again the lowing cattle, the rush of the stream’, a sequence that, in Beckett’s drama, refers to an abattoir and which triggers one of the movement’s most violent moments of submersion at Fig. Z.21 But the Beckett text also provides an insightful commentary on Mahler’s work: the Scherzo’s generic status as a macabre ‘dance of death’ whose uncanny inability seemingly to reinvent and develop itself, as Lóránt Péteri has eloquently argued,22 ultimately ends in nothingness and collapse. Berio’s gloss, in retrospect, offers not simply playful postmodern irony, but a much darker reading of twentieth-century musical history, a nightmarish memory of musical events haunted by the ghosts of past and contemporary violence and conflict.

Carter: Symphony of Three Orchestras

A similarly energetic and apocalyptic vision of the century is offered by Elliott Carter’s Symphony of Three Orchestras, a work composed in 1976 to commission from the New York Philharmonic but which is anything but a straightforward celebration or occasional piece. For both Berio and Carter, the idea of the ‘symphony’ is seemingly more ancient (savage and ritualistic) than its nineteenth-century heritage implies. Yet Carter’s work, like Berio’s, is also challengingly modern. One of the most immediate characteristics of the Symphony of Three Orchestras is its formidable complexity and density of musical detail – in that sense, the work represents one possible end-point of the process of maximalisation (understood here in terms of raw data rather than length or volume alone) identified by Taruskin as one of the defining qualities of the twentieth-century symphony. The work also perpetuates a more chamber-musical idiom: one of the Symphony’s more obviously modernist aspects is the way in which it breaks the ensemble down into smaller, more virtuosic assemblages, so that at times the work displays a markedly concertante character. Carter’s Symphony also plays explicitly with notions of time and space. Unlike Berio’s Sinfonia, Carter’s work is performed without a break – the Symphony can be heard as a single, gradually descending musical arc, although its internal structural organisation is characteristically more complex. But the basic division of three separate orchestras implies a spatial broadening of the symphonic domain, as well as an intensification of its multiple temporal possibilities – the three orchestras rarely, if ever, coincide rhythmically, and Carter’s polymetrical counterpoint ensures that the music constantly offers a shifting array of different temporal and spatial perspectives.

Yet despite this complexity, the Symphony of Three Orchestras is also one of Carter’s most poetic and imaginative large-scale works. The work’s initial impetus is a poem, entitled ‘The Bridge’, by the early twentieth-century American modernist Hart Crane. Opening with an aerial portrait of the New York skyline from Brooklyn Bridge, Crane’s poem is a hymn to the city and the diverse sounds and machine noise of the metropolis – and simultaneously an anxious urban portrait of the new world. David Schiff has christened the work Carter’s ‘Great New York Symphony’.23 Brooklyn Bridge itself offers multiple symbolic images: an architectural landmark, a transport artery, a spatial and temporal span that suggests the journey from one continent to another, a metaphor for the flow of human traffic that drove European emigration in the early twentieth century, a progression from the earthly world towards the divine, and also a nostalgic leave-taking (‘As apparitional as sails that cross / Some page of figures to be filed away; / – Till Elevators drop us from our day’). Crane’s poem suggests a Homeric odyssey, a journey towards an unknown domain or mythic region that is simultaneously an unexpected home-coming, in which the poet appears as both wanderer and vagrant. And, for Carter, this stylised mythic image of the American hobo at the heart of Crane’s work is equally a symbol of the artist as a lone, uncompromising modernist pioneer, whose new musical language (unfolded by the Symphony) can be heard as an imaginative projection of their explorative spirit. The opening bars of the Symphony respond to this imagery in a particularly vivid and direct way: the swooping bird-calls and descending figuration of the introduction (bars 1–10) suggest the soaring bird’s-eye view of the city evoked in Crane’s poem. The gradual textural and harmonic in-filling (beginning with a rare triadic sonority in the upper strings that is swiftly ‘coloured’ by more chromatic elements) suggests the slow emergence of a wide, deep panorama, like a camera panning back in the opening scene of a movie to unveil a broad cinematic landscape.24 The trumpet solo that follows is a musical portrait of the artist as a free, imaginative presence, the work’s most sustained and elaborate melodic statement, expanding outwards intervallically with a liberating sense of rhythmic freedom. The Symphony thus opens with a striking sense of structural and expressive poise – a feeling of balance and apparent weightlessness, similar to the breezy syntax of Crane’s text, which the remainder of the work anxiously begins to destabilise.

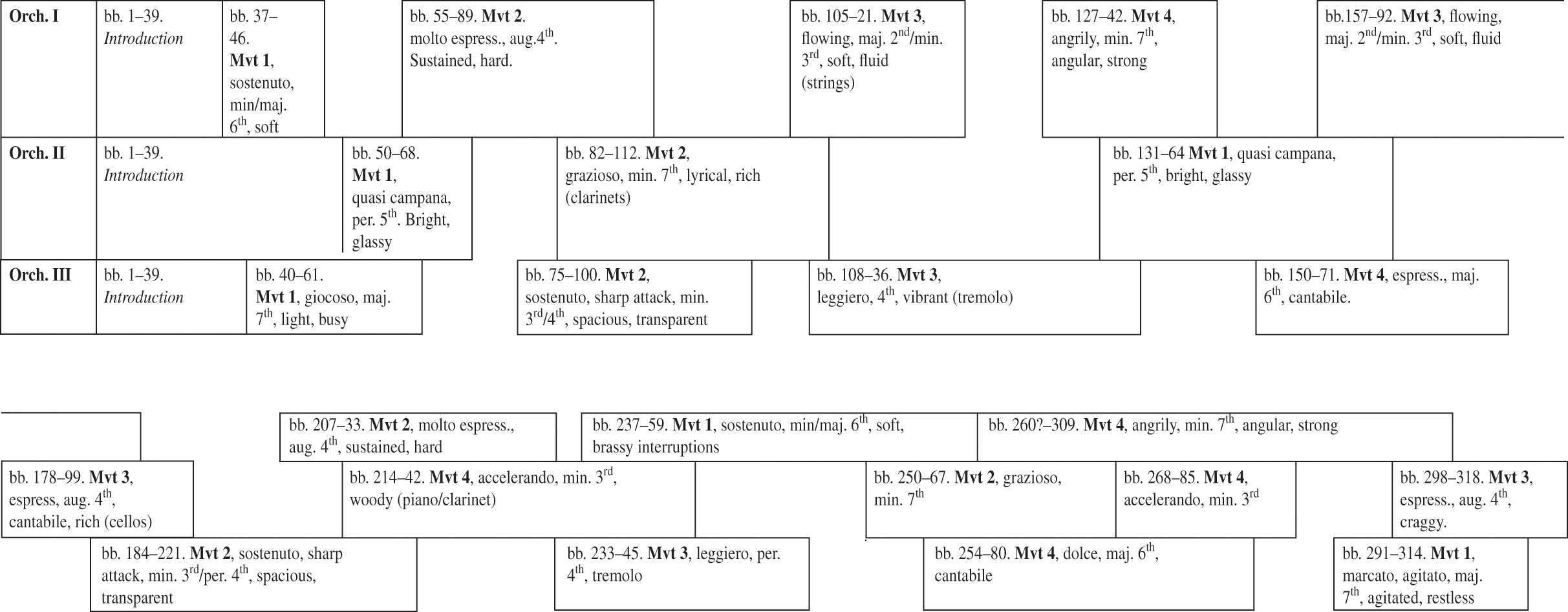

The major part of the Symphony, following the introduction, is defined by the interaction of the three orchestral ensembles suggested by the work’s title. Carter plots the Symphony’s course through two statements of a four-movement cycle, but with different ensembles playing different movements at different times in varying orders (see Fig. 12.2), so that the structure can be understood as a twisting, large-scale structural counterpoint that spirals outwards from the introduction towards the forceful unison chords of the coda (from bar 318).

Figure 12.2 Carter, Symphony of Three Orchestras, form

David Schiff has carefully charted the different characters of the individual movements, listing their contrasting expressive, intervallic and metrical properties and tracing their articulation across the course of the work.25 As is apparent from Figure 12.2, the interlacing of different movements spread across the three orchestras creates a rapidly changing montage of sound. At times, particular ensemble groups may take precedence (Orchestra II in bars 100–5 and 142–50; Orchestra III in bars 121–7 and 199–207), and elements of the opening trumpet motto can be heard echoed in certain passages spread across the main body of the work (for example, in the rhythmic fluidity of Orchestra I’s movement 3, bars 105–21 and 157–92). But Carter maintains, in his notes printed at the head of the study score, that ‘the listener, of course, is not meant, on first hearing, to identify the details of this constantly shifting web of sound any more than he is to identify the modulations in Tristan und Isolde, but rather to hear and grasp the character of this kaleidoscope of musical themes as they are presented in varying contexts’.26 For most listeners, even on subsequent hearings, Carter’s music will hardly seem thematic, at least in a normative sense. Much more compelling, especially from a symphonic perspective, is the interaction and exchange of different timbral and gestural characters. Three basic modes of expression are articulated in the opening round of movements: Orchestra I’s sustained, ‘inviolate’ string chords (bars 37–46), the bright, edgy bell-like timbre of Orchestra II (dominated by perfect fifths, bars 50–68) and the more lively, potentially explosive figuration of Orchestra III’s giocoso music (bars 40–61); similarly contrasting modes of gestural behaviour mark each of the subsequent sections. Initially, at least, the pattern of interchange resembles a conversational dialogue. But, as the Symphony progresses, the texture becomes increasingly tense and agitated. The return of the giocoso music in Orchestra III at bar 291, for example, is now restless and uneasy, and the second statement of Orchestra I’s fourth movement (marked ‘angrily’) has expanded from merely fifteen bars to almost 50. Rather than working towards resolution or consonance, the level of dissonance rises incrementally as the work progresses, so that the strident series of tutti chords that dramatically sunder the work from bar 318 appear as the end-result of a process of intensification and conflict. The coda is dominated by hollow, repetitive mechanistic ostinati – the polar opposite of the free-flowing, seemingly improvisatory spirit of the trumpet solo that opens the work – and a final cadenza for piano, tuba and double bass, which, as Schiff suggests, completes the ‘double dramatic trajectories of the work, from high to low, lyrical to mechanical’.27In the context of Crane’s poem, it is hard not to hear this ending as a bleak renunciation of individual liberty, a nightmarish vision of the modern city as a crushing weight of machine noise and expressive violence. Schiff summarises the work as ‘the most extreme statement of tragic disjunction Carter ever attempted for orchestra’.28 But Carter’s music is characteristically ambiguous, and it is equally possible to enjoy the neat symmetry of the work’s closing gesture, the low sounds and resonant timbre in balance with the ethereal luminous sonorities with which the Symphony opened.29 In that way, Carter achieves a compelling sense of structural and expressive poise, and the work completes a circular journey that seemingly brings the listener back to the brink of the opening bars, even as the music plunges into the abyss.

Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen: Symphony, Antiphony

Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen’s closely contemporary Symphony, Antiphony, composed in 1977, is similarly ambivalent, though it plays with radically different musical materials. Born in 1932, Gudmundsen-Holmgreen is a senior representative in Danish music of a tendency described by Poul Nielsen as ‘new simplicity’ (‘ny enkelhed’). ‘Simplicity’ here refers not to musical meaning or imagination – as is readily apparent, Gudmundsen-Holmgreen’s music is anything but simple in that sense. Rather, it refers to a vivid clarity of expression and design, promoted partly in response to the perceived over-intellectualism of the Darmstadt school (principally Boulez and Stockhausen). Implicit also, perhaps, is a characteristically Nordic preoccupation with structure and objectivity – aspects of which Gudmundsen-Holmgreen also shared with members of the New York group including John Cage and (especially) Morton Feldman, composers who otherwise seem remote from any traditional sense of the symphonic. Other formative influences on Gudmundsen-Holmgreen include Samuel Beckett – like Berio, Gudmundsen-Holmgreen was strongly drawn to Beckett’s antagonistic, deconstructive approach to received convention, and to the idea of a gestural theatre of the absurd, in which language has been reduced to a series of speech acts whose meaning has been continually deferred or withheld. An important early landmark in Gudmundsen-Holmgreen’s work is the Beckett setting Je ne me tirai jamais. Jamais (1966), an anti-song cycle whose alternating violence and playfulness responds forcefully to the inherent ambiguity (or multivocality) of Beckett’s text. Gudmundsen-Holmgreen’s attitude to the symphonic tradition in Symphony, Antiphony, is similarly double-edged and destabilising. As Ursula Andkjær Olsen has suggested, ‘throughout Gudmundsen-Holmgreen’s music speaks a certain productive irony. An irony that has nothing to do with the everyday use of the term, which is closer to sarcasm in its meaning, but an irony that is continually on the move, an instability of meaning, both a yes and a no’.30 For Andkjær Olsen, Gudmundsen-Holmgreen’s music is inhabited by a wild array of speaking voices – not simply individual instruments or instrumental groups, but different kinds of music. The resulting ‘sounding together’ in Symphony, Antiphony is violently unpredictable: a ritualistic theatre that occasionally observes the rules of polite conversational dialogue, but more frequently erupts into ‘a kind of mass hysteria or unrestrained anarchy’.31

Yet, for all its apparent violence and nihilism, Gudmundsen-Holmgreen’s music is richly allusive and tautly designed. The two-part design of Symphony, Antiphony is highly asymmetrical: the first part, ‘Symphony’, which Gudmundsen-Holmgreen maintains can be performed as an independent work, is barely two and a half minutes long, whereas the following ‘Antiphony’ is almost ten times this length: a massive structural imbalance which the work makes little attempt to redress. ‘Symphony’ begins by systematically unfolding one of Gudmundsen-Holmgreen’s basic musical structures: a chromatic pitch field that expands outwards symmetrically from a single focal pitch (D), divided at the tritone (A♭) until it covers ten of the twelve available chromatic pitch classes (the missing notes are the tritone pair F♮ and B♮; see Example 12.9).

Example 12.9 Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen, Symphony, Antiphony, opening.

The music simultaneously begins a process of timbral expansion, from the bell-like vibraphone, piano and marimba at the start, through the addition of woodwind (playing fragments derived in diminution from the opening pitch structure) and strings (largely playing open strings), and eventually with strident brass fanfares. The entry of the unpitched percussion in bar 23, however, critically destabilises this constructivist process of gradual textural and metrical accumulation, and the ‘Symphony’ collapses, revealed as an unsustainable fiction, under the weight of a series of crushing blows on the tam tam. Only dying echoes of the opening pitch (D) remain on the lowest string of the double bass, slowly resonating until they fade, exhausted, into complete silence.

One of Gudmundsen-Holmgreen’s most striking compositional strategies is the ability to render familiar musical materials suddenly strange and disorientating. The opening of ‘Antiphony’ is an excellent example of this process: a solo violin plays with a simple three-note motive (D-E-F♯) in varying melodic formations – an idea whose diatonicism sounds all the more shocking after the brutal ending of ‘Symphony’. As Andkjær Olsen records, the origin of this device may lie in one of the early technical exercises Gudmundsen-Holmgreen undertook with his first composition teacher, Finn Høffding: the task of finding as many ways as possible of ordering three notes into a melodic sequence.32 The gesture thus has the quality of a new start, a conscious back-to-basics attempt to rebuild a musical language from scratch after the implosion at the end of the preceding movement. But it also assumes the status of a ‘found object’ or objet trouvé; a pre-existent musical element discovered seemingly by chance and recontextualised within a new stylistic domain. Much of Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen’s work is characterised by a similar sense of bricolage, whether referring to actual pieces (such as the Larghetto from Mozart’s ‘Coronation’ Concerto, K 537, in Plateaux pour Piano et Orchestra, 2005), or more broadly to musical types, as is the case here. Hence, ‘Antiphony’ can in one sense be heard as a series of six interlinked variations on material shattered and fractured in the opening ‘Symphony’. But in another sense, the ‘Antiphony’ is generated by the juxtaposition of sharply contrasting blocks of different kinds of music: the violin’s innocent diatonic doodling, raucous animal calls in the brass and woodwind, Stravinskian ragtime on the piano, melancholic late-Romantic yearning in the strings and the nostalgic sound of a solo mandolin, playing fragments of what sounds uncannily like the Song of the Volga River Boatmen. Each of the six movements in ‘Antiphony’ highlights one or other of these musical types: in the first, the violin doodles and brass-woodwind animal calls predominate; in the second, the animal calls and mandolin begin to take precedence; the third movement is the shortest, a ragtime cadenza for piano; the fourth is the work’s orgiastic climax, a multilayered collision of Sacre-like fanfares and ostinati dominated by the heavy brass; the fifth is a complete contrast, a solemn hymnic meditation for piano and flageolet strings; the sixth and final movement is an extended postlude, a Mahlerian paraphrase of swooning cadential string lines and tremolo mandolin that passes into an eerie coda. The final sounds are the wooden saltando rattle of open violin strings and the rasping whirr of unpitched percussion: a dusty musical death.

Gudmundsen-Holmgreen’s Symphony, Antiphony underlines the contingency of notions of symphonic tradition and inheritance. It collapses familiar conventions of musical time and space, only to reassemble them in a strange and unfamiliar theatre in which collision, superimposition and simultaneity begin to seem consonant even though they never become fully comprehensible in their entirety. Indeed, the work challenges the very idea of such comprehensibility, emphasising the gestural, performative quality of its musical language over and above the question of musical semantics. As Andkjær Olsen suggests, Gudmundsen-Holmgreen’s music is figurative (or, rather, connotive), even if it remains unclear precisely what it is supposed to represent. Even as it vividly deconstructs the genre, however, Symphony, Antiphony ultimately reinforces the idea of the symphonic as a musical category. It successfully promotes (and problematises) the idea of large-scale musical form, and reaffirms the symphony orchestra as a vehicle for sustained musical communication. In that sense, the work becomes emblematic of a broader trend in twentieth-century symphonic composition. It exemplifies the tendency, demonstrated in different ways by the five works discussed in this chapter, towards fragmentation, alienation and reconstruction: the cyclic process of decay and renewal that becomes a red thread throughout much twentieth-century music, from Sibelius and Stravinsky to Berio and beyond. And, while this process often seems painful, inevitably directed towards its own imminent generic self-destruction, it ensures that the symphony remains an effective mirror of the modern condition. Perhaps, in that way, the twentieth-century symphony remains faithful to its eighteenth-century origins: the subtle merging of public and private space in conversational dialogue, the ritualised ‘sounding together’ of multiple musical languages, dialects and identities. Never has the need for such dialogue seemed more urgent.

Notes

1 , Sibelius, trans. , 3 vols. (London, 1986), vol. II, 76–7 . The English edition does not list the source, which appears only in Tawaststjerna’s Swedish original, rev. Fabian Dahlström and Gitta Henning (Stockholm, 1991), and is from , Jean Sibelius: His Life and Personality, trans. (New York, 1938). As Tomi Mäkelä has recently noted, no documentary evidence for Sibelius’s account of the meeting in fact survives, so the authenticity of the conversation is difficult to verify.

2 The case is made by at the start of his essay, ‘Orchestras, Concert Halls, Repertory, Audiences’, in Orientations, ed. , trans. (London, 1986), 467–70.

3 For some sense of the tensions and contradictions involved, see , The Oxford History of Western Music, vol. IV: The Early Twentieth-Century (New York and Oxford, 2005), esp. chapters 57 (‘The Great American Symphony’, 637–49) and 59 (‘Readings’, on Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony, 791–6).

4 , Introduction to the Sociology of Music, trans. (New York, 1976), 209–10.

5 , The Culture of Time and Space, 1880–1918 (Cambridge Mass., 1983, repr. 2000), 68–70.

6 , Musical Composition in the Twentieth Century (New York and Oxford, 1999), 10.

7 , Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions: A Biography of the Works through Mavra (Berkeley, 1996), 1618.

8 , ‘The Musical Language of the Fourth Symphony’, in and , eds., Sibelius Studies (Cambridge, 1997), 296–321, this reference 299–300.

9 , Jean Sibelius: Progressive Techniques in the Symphonies and Tone Poems (New York, 1998), 132 and , Symphonic Unity: The Development of Formal Thinking in the Symphonies of Sibelius, trans. (Helsinki, 1993), 97.

10 , Sibelius: Symphony No. 5 (Cambridge, 1993), 29–30.

11 , ‘On the First Movement of Sibelius’s Fourth Symphony: A Schenkerian View’, in and , eds., Schenker Studies 2 (Cambridge, 1999), 132–3.

12 The most influential account is , ‘Stravinsky: The Progress of a Method’, Perspectives of New Music, 1/1 (1962), 18–26. For a critical review of Cone’s analysis and other more recent trends in Stravinsky analysis, see , ‘Towards a “Logic of Discontinuity” in Stravinsky’s Symphonies of Wind Instruments: Hasty, Kramer and Straus Reconsidered’, Music Analysis, 17/1 (1998), 39–65.

13 On Stravinsky’s faith and the composition of the Symphony of Psalms, see , Stravinsky: A Creative Spring (New York, 1999), 498–500. See also , Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions, 1618. Taruskin notes that, ‘on 9 April 1926 Stravinsky made confession and took communion for the first time in two decades. From then until the early American years, he would be a devoted son of the Orthodox church.’

14 , The Music of Igor Stravinsky (New Haven, 1983), esp. 344–51. For a critique and response to van den Toorn’s work, which argues against the primacy of the octatonic set in Stravinsky’s music, see , ‘Stravinsky and the Octatonic: A Reconsideration’, Music Theory Spectrum, 24/1 (2002), 68–102.

15 , ‘1930: Symphony of Psalms’, Tempo, New Series, 97 (Stravinsky Memorial Issue, 1971), 19–27, this reference 19.

16 , ‘Running in Place: Sketches and Superimposition in Stravinsky’s Music’, Music Theory Spectrum, 23/2 (2001), 196–216, this reference 200.

17 Mellers, ‘1930: Symphony of Psalms’, 26.

18 Taruskin, Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions, 957–65. The term is also discussed by Horlacher.

19 , Playing on Words: A Guide to Luciano Berio’s Sinfonia (London, 1985).

20 Ibid., 21–6.

21 Ibid., 69–70.

22 , ‘The Scherzo of Mahler’s Second Symphony: A Study of Genre’ (Ph.D. diss., University of Bristol, 2008).

23 , ‘Carter as Symphonist: Redefining Boundaries’, Musical Times139/1865 (1998), 8–13, this reference 10.

24 Ibid.

25 , The Music of Elliott Carter (London, 1983), 295–301.

26 , ‘A Symphony of Three Orchestras (1976)’, reprinted in The Writings of Elliott Carter: An American Composer Looks at Modern Music, ed. and (Bloomington, 1977), 366–7.

27 Schiff, The Music of Elliott Carter, 300.

28 Schiff, ‘Carter as Symphonist’, 11.

29 It is interesting to compare the quality of this ending with the closing bars of a later millennial symphonic work, Per Nørgård’s Sixth Symphony (‘At the End of the Day’, 1999). Nørgård’s work is similarly dark and dominated by extensive use of low registers, but here the music’s timbre assumes a rich, burnished quality that suggests saturation rather than obliteration.

30 ‘Igennem Gudmundsen-Holmgreens musik taler altså en art produktiv ironi. En ironi, der intet har at gøre med den dagligdags brug af ordet, der nærmest sætter dets betydning lige med sarkasme, men en ironi, der hele tiden er på færde, som en betydningsuro, et både ja og nej.’ , ‘Hvert med sit Næb’: Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreens musikalske verden (Copenhagen:, 2004), 12.

31 ‘[E]n art massehysteri, et tøjlesløst anarki’. Ibid., 133.

32 Ibid., 15.