15 The symphony as programme music

On one level, most symphonies are programmatic in some sense, many of these hardly ‘musical’. The forces that bear on composers are many and various. Symphonists, most obviously Shostakovich and other Russians, have been subjected to political programmes, but musical politics may play a more subtle role, as in the not implausible suggestion that Vaughan Williams allowed ideas of English musical revival to colour perceptions of his symphonies in ways that may not have been in his mind when he wrote them.1 That composers have tended to be defensive about associations from outside the sphere of the ‘purely musical’ since the time of Hanslick is another instance of the force that ideas can have in helping to obfuscate the surprising concreteness that composers’ perceptions may sometimes assume. As a result, study of the programme symphony is hardly a matter of establishing tidy categories. The most ‘absolute’ of works remains open to reinterpretation, which may arise from ancillary information in letters and sketches that are not strictly part of the aesthetic experience bequeathed by the composer. Programmes in symphonies have an awkward habit of attaching themselves in spite of the composer’s most studied neutrality in the face of the idea.

Multi-movement symphonies with programmes existed before Liszt wrote his Faust-Symphonie and Symphonie zu Dantes Divina Commedia. It is arguable that neither work made an epoch. Formally, their three- and two-movement structures sparked no host of imitators (already ‘as a rule, narrative or semi-narrative programs like Beethoven’s led his contemporaries much further afield from symphonic forms’).2 There were other models for symphonies with voices in Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Berlioz, the significance of which was more to do with their appearance alongside the first symphonic poems so-called, with which Liszt did make history, producing ‘the only instrumental genre that can be considered as characteristic for the New German School’.3 In time, symphonic poem and symphony developed hybrids that created problems of classification and understanding. This was partly because they shared the three qualities that Carl Dahlhaus defined as essential for the emergence of the symphonic poem: preserving the ‘classical ideal of the symphony without yielding to a derivative dependence on its traditional formal scheme’; the raising of programme music ‘to poetic and philosophical sublimity’; and the union of expression with ‘thematic and motivic manipulation’.4 Nonetheless, the importance of these in altering the nature of the programme symphony should not obscure the fact that other models already existed.

Characteristics and programmes

In the second of her Lettres d’un Voyageur, George Sand noted that:

The first time I heard Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony I was unaware of its true subject-matter and to this enchanting harmony I made up in my head a poem in the manner of Milton. At the very point at which the composer makes the quail and the nightingale sing, I had set the fall of the rebellious angel and his last cry to heaven. When I learnt of my mistake I revised my poem at the second hearing, and it turned out to be in the manner of Gessner, my response being readily attuned to the impression Beethoven had meant to create.5

Since Gessner’s literary and artistic works are not without pretensions to the sublime, Sand’s revised impressions are not entirely purged of Miltonic associations. Nor is it clear that they should be. The history of the programme symphony is only partly about composers’ intentions, or indeed about their response to extra-musical stimuli. The search for programmatic points of reference in ‘abstract’ forms such as the symphony has been a source of entertainment to listeners from the ‘Pastoral’ onwards, certainly, and even before. One result of this has been to obscure what may legitimately be defined as a ‘programme symphony’. The ‘Pastoral’ helps to formulate one of the difficulties. Beethoven’s famous claim that it embodied feeling rather than representation seems to make it a key stage in the evolution of the programme symphony. Yet this has not proved incompatible with viewing it as a ‘characteristic symphony’ in the baroque manner. F. E. Kirby equated the central concept in the history of the programme symphony, the ‘poetic idea’, with a ‘single emotional character or quality throughout’. He defined ‘characteristic’ as ‘an attribute or set of attributes that distinguishes or characterizes something’ and that could involve either uniqueness or typicality, and suggested a repertory based on style and other factors that was the appropriate area for a music of this kind.6

The idea of a characteristic symphony has not been without influence. The increasing attention paid to it has led to some rehabilitation of Arnold Schering’s views of programmatic traces in composers of the classical era, as when James Webster noted that his ‘lack of attention to the distinction between authentic and inauthentic evidence and infelicities in the concrete interpretations’ did not prevent his article being ‘the best single survey of Haydn’s programmatic symphonies we have’.7 Webster cites evidence relating to Haydn’s portrayal of ‘moral characters’ or ‘characteristics’, which seems to go beyond what Kirby had in mind; a later writer on Haydn moves characteristics away from Kirby’s style-based examples to ‘connotations of emotion, unity, and humanity’.8 This seems to rehabilitate the programme in Haydn in a manner more akin to Schering’s ‘poetic idea, programme, or “romanzetto”’; but Webster had already distinguished between ‘programmatic or extramusical associations’ and symphonies that were ruled by ‘“characteristic” topoi . . . to be understood as associational, rather than as representations of tangible objects’, which seems to rework Beethoven’s famous formula.9 And it is clear that Webster views Haydn’s ‘explicitly characteristic symphonies’ as relatively early works devoted to times of the day, weather, the hunt and the sacred.10

The question arises as to whether the programme symphony emerged from the characteristic symphony or whether the latter was merely a subset of the former. Webster introduced the notion of a ‘strong’ programme (as in the case of Il Distratto) that depended on the dissemination of a work in association with a specific idea (which could be expanded to embrace a narrative) and thus stood above mere associations or characteristics.11 That this is a better model for nineteenth-century orchestral music is arguable. But Webster also treats the ‘Farewell’ Symphony as a programmatic work based on an explicit narrative. There is a leap of faith here that is akin to later enterprises that would be labelled hermeneutic. The famous tale of the elaborately staged withdrawal of the musicians in the Finale is extended to the whole work, and its provenance is assumed to be authentic.12That there must inevitably be a doubt about this properly locates the ‘Farewell’ Symphony in the category claimed by Ludwig Finscher for the uncertain area ‘between absolute and programme music’, which is where George Sand should probably be located with her pleasant fantasies about Milton and Gessner.13

It is possible to note that characteristic and programme symphonies are rightly to be distinguished from one another by degrees of authority in the provenance of ideas or narratives, but that there is constant interchanging of elements between the two areas, reinforced by the open invitation to speculate provided by associations that are usually implicitly extramusical. But this does not resolve the questions of terminology on any firm basis. Even the description ‘characteristic symphony’ seems a little imposed on music by the musicologists’ desire to classify. The most exhaustive study of the characteristic in music between 1750 and 1850 has found only four explicit uses of ‘characteristic symphony’, among them the ‘Pastoral’ on the strength of a sketch rather than a title, and Spohr’s Die Weihe der Töne.14 The idea of the characteristic is thus as much a tool for interpretation as an explicit genre. And it also helps to distinguish between the ‘literary’ programme symphony that stems certainly from Liszt and Berlioz, and those works that celebrate nature through the use of topoi; the distinction may be illustrated somewhat later by the contrast between the seasonal symphonies by Raff and his more explicitly literary Lenore.

Finally, it is arguable that the nineteenth-century programme symphony operated at least in part by creating its own characteristic topoi to replace more conventional affects, or alternatively marshalled the characteristic into newer contexts by narrative programmes and associations with literature. In support of this may be cited a recent analysis of Mendelssohn’s ‘Reformation’ Symphony by John Toews. He reads the work as programmatic in a double sense: the ambition ‘to recreate the essence of Bach’s sacred music for a new age’; and ‘the elevation of the individual soul into the divine order’.15 In the first sense, the formal structures are the programmatic content, and the characteristics are the psalm tone, amen and chorale that Mendelssohn cites (quotation is a major theme in studies of programmatic content, as already is evident in Schering’s and Webster’s tracking of liturgical elements in Haydn’s symphonies).16 The ‘Reformation’ is therefore ‘an historical program symphony’ whose generic echoes may be analysed hermeneutically (a more complex version of the explicitly historical symphony that Spohr essayed somewhat later). Bach’s music stands for the Reformation that ensured the triumph of the second element. Quotations and generic references became central to, and substitute for the ‘characteristic’ in the nineteenth-century programme symphony, as ‘an essential means of rendering more precise the spoken character of the music’.17

Nineteenth-century dilemmas

Beethoven supplied the ‘Pastoral’ Symphony with something more than mere movement titles. In this respect, arguably he outstripped Berlioz in one of the key works of the emergence of the programme symphony, Harold en Italie. The status of Berlioz as a composer of programme symphonies is currently rather uncertain, given that only one of his four symphonies, Symphonie fantastique, can be considered programmatic in the strong sense: it was disseminated with a declared extramusical idea elaborated into a narrative. Stephen Rodgers, the latest writer to consider how far Berlioz contributed to the genre, takes a rather broader view of the matter than some of his predecessors.18 Is Roméo et Juliette to be considered dramatic or programmatic, or perhaps a mixture of the two? The question is hardly specific to Berlioz, since there are other works both by contemporaries (for example Mendelssohn’s Lobgesang) and by later composers (Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 and Sibelius’s Kullervo) that tell stories partly by instrumental associative means, partly by direct setting of texts. Here the manner in which Berlioz interpreted Beethoven is of interest, since Rodgers points out that Berlioz interpreted Beethoven’s Sixth and Ninth symphonies in similar ways, treating the programmatic clues of the one in much the same way as the literary text setting in the other.19 Regardless of origin, interpretation yielded a ‘poetic’ narrative. With Berlioz, there is early evidence of Mark Evan Bonds’s notion, broached in Chapter 14, of adapting the Ninth Symphony’s ‘basic strategy to purely instrumental symphonies by imbuing implicitly vocal ideas with a quality of transcendence’.20 But with Berlioz, a real narrative is often created, whereas modern reading of Beethoven’s symphonies tends to concentrate on ‘an implied significance that overflows the musical scenario, lending a sense of extramusical narrative to otherwise untranslatable events’.21 The narrative sense or shape in Beethoven helps to explain why musicologists have manoeuvred ‘between absolute and programme music’.

Some commentators in Germany drew quite explicit parallels between Berlioz’s achievement in his symphonies and the ‘Pastoral’: Peter Cornelius saw Harold en Italie as the successor to the ‘Pastoral’ but without Beethoven’s inwardness (a topos of New-German Berlioz criticism).22But among other commentators on the programme symphony, such as Richard Pohl, who was even more receptive to New-German ideas, it is clear that it was above all the vocal Ninth, not the ‘Pastoral’, which was the foundation of the modern symphony.23 That the modern symphony was programmatic was a given, but ‘in the higher sense’ involving ‘a quite specific ring of ideas with a precisely formulated musical content, to ally poetic intentions with the musical content . . .’24 The specific idea was not necessarily as detailed as a programme book, felt by Pohl to be welcome but not absolutely essential.25 It is in the face of comments such as these that it becomes apparent that ‘programmatic’ has come to mean something rather different from the characteristic or the topos.

As the most persistent advocate of programmatic interpretation of the nineteenth-century symphony, Constantin Floros has isolated as the key idea in Liszt the notion of ‘Erzählung innerer Vorgänge’, elaborated by Liszt as some common factor in nation or epoch whose interest resided more in ‘inner events than in the actions of the external world’.26 The specific turn that the programme symphony took in the nineteenth century was thus in some part an interpretation by writers digesting the lessons of Herder and Hegel; programmes and poetic ideas were reflections of ideals, a notion that jumps out of the pages of Franz Brendel, the chief propagandist of the New German School. When it came to drawing lessons from Berlioz’s programme symphonies, he differed in subtle ways from Franz Liszt. One writer has accurately noted that Brendel’s starting point was idealism, whereas Liszt was more inclined to invoke nature and its imagined laws.27As a result, Brendel gave intellectual credibility to the German tradition that viewed Berlioz as ‘more the representation of outer than inner feelings’ and hence of a failure to build adequately on the inner psychological Tonmalerei represented by Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.28

It almost certainly was not Liszt’s concern to establish such a picture of Berlioz when he produced his celebrated essay on Harold, an essay that is as much about the type of music Liszt wanted to write as the music that Berlioz had written. Thus he compared Berlioz’s first two symphonies as poems to Byron, Senancourt and Jean Paul, and specifically related this to psychological depiction.29 Liszt’s aim was ‘the poetic programme and the characteristic melody’ and something of that was to be found in Berlioz as well as drama; indeed the drama was to be found in symphonic form in Berlioz’s Damnation de Faust as well as in Roméo.30 Programmes, poetic ideas and the symphonic in Liszt’s picture of Berlioz were to some degree independent of genre and also of mere narrative. As Wolfgang Dömling has noted, it was no accident that Liszt chose to write of the symphony by Berlioz that had no direct narrative rather than the Symphonie fantastique.31 Among Liszt’s own works, it has been claimed that there are certain instances where ‘the program is not the crucial form-determining factor it has long been assumed to be’.32 This view is based mainly on pieces with allusive titles that hint at Liszt’s ‘modern’ hero of a ‘philosophical epoch’: Tasso, Prometheus, Orpheus and Faust. This group of works is based on ‘the numerous and prominent correspondences between these pieces and earlier compositional and theoretical models of sonata construction’.33 It also continues to treat symphonic poems alongside programme symphonies under the same aesthetic banner; Liszt’s highly ambivalent legacy to the writing of programmatic orchestral music. If the traditional picture of the programme symphony in the hands of Berlioz and Liszt involved extensive mixing of genres, then the years that followed Liszt’s works produced a plethora of terms and titles that thoroughly confused the concept of how poetic ideas and symphonic music might go together.

Epigoni and hybrids

If we ask what distinguished the programme symphony in the later nineteenth century from the host of other descriptions that owed something to the idea of a symphonic poem, it is possible to answer at the level of generalities:

The difference between symphony and symphonic poem works itself out less in the intellectual than the formal sphere: the symphonic poem departs persistently from the symphonic plan of order in imitation of the textual or visual model, while the symphony, in spite of all thinkable extramusical ‘content’, remains committed to this plan of order in its broad outlines.34

This distinction relegates the extramusical to the level of the secondary. The definition would do to distinguish symphonic poem from programme symphony, abstract symphony and Finscher’s hybrids. But it is at least arguable that it is easier to say what a programme symphony is or might be than to define a symphonic poem. Something of this might be apparent from consideration of that strange area in the composition of symphonic works that stretches from the last symphonic utterances of Liszt and Spohr in the late 1850s to the appearance of Brahms’s First Symphony in 1876, a period marked by the evolution of various ‘nationalist’ symphonists and the earliest works by Bruckner, and by much else that has been described under the term ‘forgotten symphonies’ (this gap is filled in by David Brodbeck in Chapter 4).35

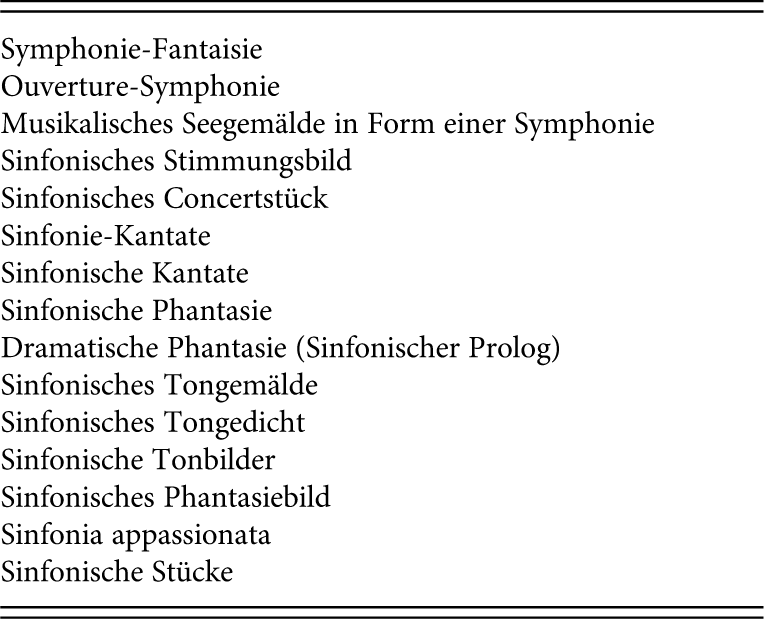

One catalogue of symphonic novelties in the period 1850 to 1875 (Table 15.1) reveals these among numerous other generic titles (some so specific as to be hardly generic).36 The influence of ‘symphonic poetry’ is traceable in quite a few of these (even more when descriptive titles augment the generic description), and yet they outnumber the group of explicitly entitled symphonic poems. Although not so noted by Grotjahn, they also stand up well to the number of symphonies whose titles proclaim them to be in some measure programmatic.37When we consider this neglected area, it is quite thinkable that Finscher’s now celebrated formula be adapted to suggest not merely the lurking presence of quasi-programmatic content in abstract-seeming symphonies, but also programmatic works whose resemblance to ‘absolute music’ is close enough to engender confusion, as well as works between symphony and symphonic poem that flirt with the idea of the programmatic but withhold the substance (as in Brahms’s tantalisingly entitled Tragische Ouvertüre, which has its symphonic counterpart in Draeseke’s Symphonia tragica).

Table 15.1 Rebecca Grotjahn’s catalogue of mid-nineteenth-century generic titles

As an example of the manner in which programmatic elements may infiltrate abstract designs with apparently minimal change to normal working procedures, we can take Friedrich Gernsheim’s Symphony No. 3 in C minor, which, the composer noted, had its ‘point of departure’ in the idea of ‘Miriam’s Song of Victory’ (the composer in his youth had been greatly taken by Handel’s Israel in Egypt).38 Yet he denied that it was programme music (perhaps to be expected in a composer reckoned among the followers of Brahms by contemporaries) and insisted that it was a mood picture, thus begging the questions of how far a mood picture incorporated a ‘poetic idea’, especially since the second movement was acknowledged as a portrait of Miriam herself in distress on a summer night by the banks of the Nile with timbrel. Yet the context of Gernsheim’s programmatic comments indicates that this is essentially a work of struggle and triumph on the model of two other symphonies in C minor, and is not to be regarded as more or less programmatic than Beethoven’s Fifth or Brahms’s First. Nor is it substantially different in style, technique and form from Gernsheim’s other symphonies. As one instance we may take a feature of the first movement: the development and reprise are elided, with no real thematic return to the first subject – the reprise is tonal until the entry of the second subject renders it also thematic. This is only slightly more extreme than Gernsheim’s practices in his other first movements: to alter the return of the first subject by placing it over a dominant pedal, by inverting its position from treble to bass, or by abbreviating it and altering its continuation. His finales exhibit the same range of tricks with more emphasis perhaps on rescoring than rewriting. The Third Symphony essentially preserves the main features of symphonic form that Gernsheim inherited from Mendelssohn, Schumann and Brahms. Only the presence of a harp (a sign of lurking narrative content) betrays an interesting departure from the composer’s normal practice. Of this ‘Miriam’ Symphony, it is possible to echo Michael Kennedy’s summary of Vaughan Williams’s London Symphony: ‘This is a programme symphony, but it is also perfectly acceptable as “absolute” music.’39

By comparison, a composer like Joachim Raff who had belonged (albeit half-heartedly) to the New German School went rather further in adapting symphonic form to programmatic purposes. This was more marked in works with literary or quasi-literary programmes than in those that recall the characteristic symphony. Thus the symphonies (nos. 8–11) based on the four seasons and the Symphony No. 7, ‘In the Alps’, all conform to four-movement form and have titles that adhere to content that was typical of such programmes from the Baroque onwards, or reinterpret them in Romantic spirit: ‘Spring’s Return’, ‘Man’s Hunt’, ‘First Snow’, ‘Harvest Laurel’, ‘By the Hearth’, ‘In the Inn’, ‘By the Lake’; and ‘Walpurgis Night’, ‘Ghost Dance’, ‘The Hunt of the Elves’. The Third Symphony, ‘Im Walde’, imposes a part structure on the movements in anticipation of Mahler’s practice in some symphonies, which reflects a slightly more elaborate programmatic framework, particularly in the Finale, with its evocation of Wotan, Frau Holle and the Wild Hunt. In this it anticipates the much more literary Fifth Symphony, which groups its four movements into three parts: Liebesglück (embracing a sonata Allegro and a slow movement); Trennung (a military march for a departing hero); and Wiedervereinigung im Tode, an Introduction and Ballade based on Gottfried August Bürger’s Lenore.

This programme includes elements of mood painting such as would have seemed acceptable to Gernsheim. In Bürger’s poem, the love idyll is not present; the opening depicts Lenore’s beloved far away at the Battle of Prague with Frederick the Great’s army. The Symphony’s stylised insistence on a happy love affair thus has no direct pictorial stimulus, and results in a sonata structure that is more extensive and tonally more wide-ranging but not substantially different in approach to that of Gernsheim in ‘Miriam’. The Andante quasi allegretto is equally plausible as an abstract symphonic argument; in echo perhaps of Liszt’s Faust Symphony the two movements of Part I privilege E, C and A♭ as tonal centres, but so would Brahms’s First Symphony when it appeared a few years later. C is also the key of the march in Part II, in which there are clear signs of an army vanishing into the distance and despairing lamentation in the trio. In this, characteristics and topoi are dominant. In stressing that the Finale is specifically linked to Bürger, Raff thus distinguishes it from the more stylised opening movements and parts, and it is here that a story is most obviously told. Elements of the march return, recalling the examples of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and Berlioz’s Harold, the horse’s hoof beats sound in percussion, and after some music that can be interpreted loosely as the conversation between Lenore and her ghostly returning soldier, the remainder of the movement is dominated by his horse’s galloping figuration (Berlioz’s ‘Ride to the Abyss’ is an obvious model, more so than Liszt’s Mazeppa), and chorale phrases that reflect both passing funeral cortèges and (after the wild ride has ceased) the dying Lenore’s vision of eternity. The riding figuration is a characteristic certainly, and the chorale is one of the nineteenth-century symphony’s equivalents of a topos that inhabits programmatic and seemingly abstract works on a regular basis.

Programmes and clues to content thus hang on titles that correspond to Liszt’s well-known analogy of the ‘thread of Ariadne’, the clew that guides the listener through the novel events of the works.40 Yet musicology has become fairly sophisticated in ‘bringing music to speech’, and it is arguable that there are plentiful hints in absolute symphonies to suggest a content that is not simply abstract. This remains true of works that followed Weimar or Leipzig. Essentially, music ‘between absolute and programme’ initially depended on quotations and allusions to provide a content. At times such readings tended towards the excessively concrete: Finscher’s attempt to relate Mendelssohn’s ‘Scottish’ Symphony to the European craze for Scott’s novels has not found complete favour with commentators.41 This has not diluted the value of the attempt ‘to interpret from their historical context the content of musical works that traditionally had hitherto tended to be reckoned as either absolute or programmatic, and whose trans-musical dimension seems to have been submerged under arbitrary interpretation or vague general concepts’.42 Initially, such attempts depended on precisely the kind of elements that can be identified in Gernsheim and Raff: chorale, alphorn and quasi-Beethovenian conflict can unlock a content of a kind in Brahms’s First Symphony, to which ‘quotation’ or allusion (the ‘Joy’ theme) can add a dash of verisimilitude or homage depending on context, though whether this adds up to ‘nothing less than the most concrete and most ambitious programme of ideas that was ever to provide the foundation of a symphony between Beethoven and Mahler’ is at the very least debatable.43It is perhaps more appropriately read as the basis for the kind of ‘plot archetypes’ that Anthony Newcomb has seen in Schumann and others; the narrative pattern of Beethoven’s Fifth, ‘suffering leading to healing or redemption’, is readable in Brahms and Gernsheim and also, with suitable modifications, in Bruckner.44 Perhaps this seems meagre as general wisdom outside the context of specific analyses. Nonetheless, Finscher’s approach may be seen as the ancestor of the infinitely more subtle reading of Brahms’s Second Symphony by Reinhold Brinkmann, perhaps the most valuable study of abstraction yielding content in the literature about the nineteenth-century symphony.45

That the generation after Liszt tended to respond in hesitant fashion to programmes in the symphony is also suggested by Tchaikovsky’s Manfred. That the presence of programmatic elements leads to a looser treatment of traditional form is not especially surprising in Tchaikovsky’s case, since his later symphonies, the Fourth and Sixth in particular, tend towards a more episodic separation of subject groups and individual themes that encourages the listener to think programmatically even where precise details are lacking. The resulting weakening of the traditional tensions of sonata form in opening movements proceeds in Manfred to the point where it makes less sense to talk about specific forms. Although the opening movement seems to begin with an introduction, a first subject in B minor and a modulating transition, the arrival of the second subject, possibly associated with Astarte, involves changes of key, tempo and metre. The sonata structure then disappears. When the ‘first subject’ returns, B minor is restored, but not the initial metre or tempo. A Lisztian threnody as combined reprise and coda (as in Hamlet) takes over. There is more than one way in which the movement might be assimilated to traditional formal structures, but the modifications operate under extramusical stimulus, as in Francesca da Rimini.

Continuity and convergence?

In his history of nineteenth-century music, Carl Dahlhaus claimed that: ‘as far as the technical assumptions of the monumental style were concerned, at the stage of compositional evolution around 1900 there was little or no difference between the symphony and the symphonic poem’.46 He is thinking of the symphony and symphonic poem in the hands of Mahler and Strauss. Although this is far from the clearest formulation in Dahlhaus’s book, it is possible to understand his gist from consideration of what he termed Vermittlung (mediation) in Liszt between the sonata tradition and the characteristic: the idea of using changes in tone and characteristics to produce formal coherence ‘sublates the tradition of the character piece into Liszt’s conception of the symphonic’.47 Characteristics create structural and expressive connections through restatements and transformations rather than defining a dominant tone as previously. This, accordingly, is a key to understanding both movements in symphonies (the first movement of Mahler’s Seventh is his illustration of Weltanschauungsmusik that in the absence of a specific programme of ideas can be read as ‘self-sustaining’ and ‘formal-logical’) and symphonic poems such as those by Strauss.48

Here is an acknowledgement that an important reconciliation of ideas was taking place. That Liszt’s transformation of the symphonic by programmatic means was an important factor in the genesis of the ‘monumental’ orchestral style of the early twentieth century recognises on one hand that for all Mahler’s insistence that programmes should perish,49 symphonies might still be ‘read’ as texts if one knew the signs. On the other hand, the role of Liszt in the evolution of the tone poems of Strauss is acknowledged in anticipation of a prominent argument of recent years. The relationship between Liszt and Strauss has been re-examined with a view to establishing to what extent they shared a common view of the status of the poetic idea in the symphonic. Recent writers have tended to consider the link a strong one: in Walter Werbeck’s view, the notion that Liszt wrote poetic music while Strauss wrote witty illustrative programmatic music has ceased to be tenable. The programmes that they chose may have been different in tone and mood, but their approaches were fundamentally similar, albeit with a substantial injection of orchestral polyphony from Wagnerian models in Strauss’s case.50 As chapters 1 and 11 have stressed, it is possible with Strauss to see the convergence between symphony and symphonic poem move to its consummation in single-movement works that now have the dimensions of symphonies, in the Symphonia domestica and the Alpensinfonie, while with Mahler, the Lisztian ‘relativisation’ of formal categories enables symphonic movements to employ characteristics as though they were Lisztian poems.51

In spite of this, however, the programme symphony and the symphonic poem have remained stubbornly apart. It has become clear that the ‘formal-logical’ symphony with the associative title (the Harold tradition) remained alive and well to the point that commentators have regularly supplied associations that may actually diverge from the starting point of the composer’s journey (as the question of the originating idea of Vaughan Williams’s Pastoral Symphony suggests). The idea that the programme symphony might tend towards a single-movement structure, thus eliding the distinction between it and the symphonic poem, can be traced perhaps in early works by Shostakovich and in Nielsen’s Symphony No. 4, but the ‘formal-logical’ symphony has followed the same path, most famously in Sibelius’s Symphony No. 7. His career as a whole followed a curious trajectory leading from a symphony that was at once programmatic, multi-movement and partly choral to a last work that was abstract, single-movement and purely instrumental. As if to indicate that programmatic and absolute still retained certain distinguishing features, the Seventh Symphony was paired at the end of the composer’s career with a symphonic poem, Tapiola. To complete the picture, sketch studies have revealed that hermeneutic clues relating to Sibelius’s sense of nature lurk within his earlier symphonies.52

Coda: quotation and characteristics

The importance of quotation as key to content and ideas has been recognised in more than one study. A typical survey of the nineteenth-century symphonic literature has concentrated largely on composers who have contributed to programmatic symphonies and symphonic poems: Mendelssohn and Spohr, Berlioz and Liszt, Mahler and Strauss, with the addition of Saint-Saëns and the debatably programmatic Bruckner. What constitutes quotation is by no means clear, however, since the techniques involved included ‘changes of parameters’, compositional technique (e.g. fugue to bolster religious sonorities), citation of styles, generic references and thematic combinations.53 At least a few of these encroach once more on the sphere of characteristics (e.g. stile-antico counterpoint in a Haydn symphony). The notion that the symphony could present ideas as in a public oration, as conceived in the eighteenth century, yielded to associations and poetic glimpses afforded by titles, homilies (as Liszt’s programmes often appear), appended poems and analogies; the poetic substance of works of art is treated as transmutable from literature to the visual arts to music. As a result, the relationship of ‘absolute music’ to content became complex. When Gernsheim denied that his associative allusive symphony was programmatic, he anticipated a host of others who rushed on to the bandwagon of absolute music in denial at the evocative power of citation and allusion. But who on hearing the chimes of Big Ben in Vaughan Williams’s London Symphony can believe that it is only a symphony by a Londoner? And who on discovering the echoes of war in his Pastoral Symphony can ever believe in Philip Heseltine’s cow staring over a gate?54The listener’s impressions, like those of George Sand, change under the stimulus of interpretation, authorised and unauthorised, overt in the ‘strong’ sense, or buried among the fantasies and jottings of composers’ private letters and sketches.

Notes

1 , ‘Constructing Englishness in Music: National Character and the Reception of Ralph Vaughan Williams’, in , ed., Vaughan Williams Studies (Cambridge, 1996), 1–22, esp. 14–17.

2 , The Characteristic Symphony in the Age of Haydn and Beethoven (Cambridge, 2002), 171.

3 , ‘Die Neudeutsche Schule und die symphonische Tradition’, in , ed., Liszt und die Neudeutsche Schule (Laaber, 2006), 33–8.

4 , Nineteenth-Century Music, trans. (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989), 238.

5 , Lettres d’un Voyageur, ed. , trans. and (Harmondsworth, 1987), 80.

6 , ‘Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony as a “Sinfonia caracteristica”’, Musical Quarterly, 56 (1970), 608–12.

7 , ‘Bemerkungen zu J. Haydns Programmsinfonien’, Jahrbuch Peters (1939), 9–27; , Haydn’s ‘Farewell’ Symphony and the Idea of Classical Style: Through-Composition and Cyclic Integration in His Instrumental Music (Cambridge, 1991), 226.

8 Webster, Haydn’s ‘Farewell’ Symphony, 234–5; Will, The Characteristic Symphony, 8.

9 Schering, ‘Bemerkungen’, 11; Webster, Haydn’s ‘Farewell’ Symphony, 238.

10 Webster, Haydn’s ‘Farewell’ Symphony, 247.

11 Ibid., 113.

12 Ibid., 114.

13 , ‘“Zwischen absoluter und Programmusik”: Zur Interpretation der deutschen romantischen Symphonie’, in , ed., Über Symphonien: Beiträge zu einer musikalischen Gattung (Festschrift Walter Wiora zum 70. Geburtstag) (Tutzing, 1979), 103–15.

14 , Der Charakterbegriff in der Musik: Studien zur deutschen Ästhetik der Instrumentalmusik 1740–1850 (Stuttgart, 1989), 94.

15 , Becoming Historical: Cultural Reformation and Public Memory in Early Nineteenth-Century Berlin (Cambridge, 2004), 219–25; see also , Mendelssohn: A Life in Music (Oxford, 2003), 225–6.

16 Schering, ‘Bemerkungen’, 24–5; Webster, Haydn’s ‘Farewell’ Symphony, 242–4.

17 , Zitattechniken in der Symphonik des 19. Jahrhunderts (Sinzig, 1998), 193; see esp. 29–41 for the ‘Reformation’ Symphony.

18 , Form, Program, and Metaphor in the Music of Berlioz (Cambridge, 2009), 21.

19 Ibid., 22–3.

20 , After Beethoven: Imperatives of Originality in the Symphony (Cambridge, Mass., 1996), 166.

21 , ‘Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony: A Search for Order’, 19th-Century Music, 10 (1986–7), 3–23, esp. 8.

22 , Gesammelte Aufsätze: Gedanken über Musik und Theater, Poesie und bildende Kunst, ed. and (Mainz, 2004), 243.

23 , Franz Liszt: Studien und Erinnerungen (Leipzig, 1883), 26.

24 Ibid., 230.

25 Ibid., 231.

26 Musik als Botschaft (Wiesbaden, 1989), 110; , Gesammelte Schriften, ed. , 6 vols. (Leipzig, 1880–3), vol. IV, 56.

27 , Begriff und Ästhetik der ‘Neudeutschen Schule’: Ein Beitrag zur Musikgeschichte des 19. Jahrhundert (Baden-Baden, 1989), 91.

28 Ibid., 148–9; , Geschichte der Musik in Italien, Deutschland und Frankreich: Von den ersten christlichen Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart, 3rd edn (Leipzig, 1860), 509 and 513.

29 Franz Liszt, Gesammelte Schriften, vol. IV, 98.

30 Ibid., 69 and 98.

31 , Franz Liszt und seine Zeit (Laaber, 1998), 108.

32 , ‘Sonata Form in the Orchestral Works of Liszt: The Revolutionary Reconsidered’, 19th-Century Music, 8 (1984–5), 152.

33 Ibid.

34 Helmut Rösing, ‘Fast wie ein Unwetter: Zur Rezeption von Pastoral- und Alpensinfonie-Gewitter; über verschiedene Darstellungsebenen der musikalischen Informationsübermittlung’, in Mahling, ed., Über Symphonien, 70.

35 , Vergessene Symphonik? Studien zu Joachim Raff, Carl Reinecke und zum Problem der Epigonalität in der Musik (Sinzig, 1997).

36 , Die Sinfonie im deutschen Kulturgebiet 1850 bis 1875 (Sinzig, 1998), 291–319.

37 Ibid., 321–2.

38 , ‘Preface’, Friedrich Gernsheim, Symphony No. 3 (Munich, 2006), iii–iv.

39 , The Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams (Oxford, 1980), 134.

40 Liszt, Gesammelte Schriften, vol. IV, 26–7.

41 Finscher, ‘“Zwischen absoluter und Programmusik”’, 115; Todd, Mendelssohn, 434.

42 Finscher, ‘“Zwischen absoluter und Programmusik”’, 115.

43 , ‘The Struggle with Tradition: Johannes Brahms’, in , ed., The Symphony (London, 1973), 165–74.

44 , ‘Once More “Between Absolute and Program Music”: Schumann’s Second Symphony’, 19th-Century Music, 7 (1983–4), 237.

45 , Late Idyll: The Second Symphony of Johannes Brahms, trans. (Cambridge, Mass. and London, 1995).

46 Dahlhaus, Nineteenth-Century Music, 364.

47 , Klassische und Romantische Musikästhetik (Laaber, 1988), 398–9.

48 Dahlhaus, Nineteenth-Century Music, 364.

49 , Gustav Mahler: Eine biographisch-kritische Würdigung (Leipzig, 1901), 13; cited and discussed in , Gustav Mahler, vol. I: Die geistige Welt Gustav Mahlers in systematischer Darstellung (Wiesbaden, 1977), 20–2.

50 , ‘Erbe oder Verräter? Richard Strauss und die Symphonische Dichtung von Franz Liszt’, in , ed.,Liszt und die Neudeutsche Schule (Laaber, 2006), 270; a very detailed picture of Strauss’s relationship to Liszt is provided by , ‘Reshaping the Liszt–Wagner legacy: Intertextual Dynamics in Strauss’ Tone Poems’ (Ph.D. diss., University of Cambridge, 2007), chapter 2.

51 For ‘relativization’ in Liszt, see Dahlhaus, Nineteenth-Century Music, 239.

52 , Sibelius: Symphony No. 5 (Cambridge, 1993), 33–41 and ‘Rotations, Sketches, and the Sixth Symphony’, in and , eds., Sibelius Studies (Cambridge, 2001), 332–51, esp. 333–5.

53 Thissen, Zitattechniken, 179–87.

54 Kennedy, Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams, 134 and 155–6.