6 Six great early symphonists

Imagine if a scholar of Renaissance art picked out Leonardo, Raphael and Michelangelo, and ignored Botticelli, Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese, Correggio, Bellini, Giorgione, Mantegna, Donatello, Fra Angelico and countless other Italian masters (not to mention those of France, Germany, Spain, the Low Countries and England). Unthinkable as that would be, it is strange that musical scholars of the classical style are generally comfortable with the notion of a ‘big three’ of mature artists (Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven) crowning a pyramid of Kleinmeister. Yet Jan LaRue’s inventory of the eighteenth-century symphony lists 13,000 works by dozens of fine composers.1 My present purpose is to sketch the evolution of the symphony by focussing on six of these composers, whom, without any apology, I term great: Giovanni Battista Sammartini; Johann Stamitz; Johann Christoph Bach; Carl Philip Emanuel Bach; Joseph Martin Kraus; and Luigi Boccherini. Each had a distinctive artistic personality, invented an aspect of the symphony and left behind a wealth of music which can be enjoyed on its own terms.

The watchword ‘evolution’, on the other hand, would seem to commit us to a story of style culminating in the symphonies of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. Whereas Charles Rosen taught us that ‘the concept of style creates a mode of understanding, allowing us to place an individual work within an interpretive system’,2David Schulenberg is right to aver that ‘the assignment to a style might be an impediment to the understanding of a repertory’.3 Evolutionary stories are both necessary and problematic. Two unavoidable ones for the early symphony are ‘periodicity’ and ‘cyclicity’. The story of periodicity underpins Eugene Wolf’s monograph on the symphonies of Stamitz, arguably the most sophisticated – and unaccountably neglected – study of this repertory.4Chapter 8 (‘Structure at the Phrase Level: An Evolutionary Theory’) presents Wolf’s central hypothesis that ‘the chronological development of Stamitz’s style brought with it an increase in modular breadth, evolving from the small-scale motivic organization characteristic of the Baroque to the broader phrase and period structure of the Classic period’.5 Wolf fleshes out the familiar narrative that the classical style evolved in multiples of two-bar phrases (two, four, eight, sixteen), a periodicity which is then commuted from phrase to structural level to embrace the binary opposition of first and second groups, the symmetry of exact recapitulation and ultimately the four movements of the cycle epitomised by Mozart’s last three symphonies. And yet history did not necessarily march lock-step in Mozart’s direction, as we shall see. There is nothing at all inevitable about the triumph of the symmetrical recapitulation or the four-movement symphony. The same is true of the ‘cyclic’ symphony epitomised by Haydn’s Symphony No. 45 in F-sharp minor, the ‘Farewell’.6 Binding the four (or three) movements of the cycle into a unified expression of a compositional plan is a compelling ideal; Haydn’s achievement resonates with that of Beethoven and many later composers. Yet I will show that in this respect the ‘Farewell’ is really a footnote to a larger story stretching, in the first instance, from Sammartini in the 1730s to Boccherini in the 1780s. Thus it is important not to confuse periodic symmetry and cyclic unity with stylistic coherence per se. Coherence is possible in manifold forms befitting the attributes of different musical materials in successive historical periods. Conversely, the symmetry of late Mozart, like the unity of middle-period Haydn, is just as much an expression of a unique artistic personality as the ostensible ‘irregularity’ of the so-called Kleinmeister.

The symphony originates, like so much European music, in the dialogue across the Italian Alps. Pursuing this dialogue through several stages of the early symphony, I will look at Stamitz’s reception of Sammartini and the stylistic polarity of J. S. Bach’s second-oldest and youngest sons. Of the myriad symphonists who reached their maturity in the 1780s, I have chosen Kraus and Boccherini through reasons of artistic quality and because they exemplify the regional dispersion of the genre, in this case to Sweden and Spain. Paradoxically, it was Viennese symphonists such as Monn, Holzbauer and Wagenseil who were peripheral to the development of the genre, notwithstanding their take-up of the four-movement model after the Austrian partita or parthia.7 Mozart learnt much on his travels.

Early Sammartini, late Stamitz

Sammartini

World-embracing yet formally autonomous, the peculiarly hybrid genre of the symphony was born from a marriage of the Italian operatic overture and the baroque ripieno concerto. But the detail of the marriage contract was complex, as attested by the nineteen early string symphonies Sammartini composed for the Milanese accademie (private concerts sponsored by nobility) in the 1730s and early 1740s. Sammartini’s ‘concert symphonies’ – a genre singled out in Scheibe’s famous report as being more artful and freely imaginative than either ‘dramatic’ or ‘church’ symphonies8 – owe less to the overture than to the concerto and trio sonata. The overture’s influence grew later, with Stamitz at Mannheim. Notwithstanding the conflict of terminology, whereby the rubric ‘symphony’ was used interchangeably with ‘overture’, ‘concertino’ and ‘trio sonata’, it is instructive to consider Sammartini’s overture to his first opera Memet alongside the two symphonies he cannibalised for the introductions to acts II and III, nos. 43 and 76.9All three movements of the Memet overture are substantial, whereas the Sinfonie avvanti l’opera by Vinci, Leo and Pergolesi tended to be dominated by their opening movement. The Memet overture owes its cyclic balance and characteristic rhythmic drive to the concerto. At the same time, this drive is counteracted by the binary sonata form of all three movements – a conflict which animates Sammartini’s later symphonies and drove their stylistic evolution. In these respects, as well as in its three-part texture (independent parts for basso and viola, with violins I and II generally playing in unison), the overture is perfectly in line with symphonies nos. 43 and 76. Haydn notoriously called Sammartini ‘un umbroglione’ (to Carpani) and ‘ein Schmierer’ (to Griesinger),10 yet the cyclicity of his ‘Farewell’ Symphony is implicit within the architecture of these works. In both their first movements, lack of cadential articulation – what Hepokoski and Darcy call a ‘medial caesura’ – means that the music sweeps towards the exposition’s closing theme.11 But this ostensible fault actually serves the interest of the cycle, since Sammartini’s finales are habitually articulated by regular and sharply defined cadences. They thus afford both goal and closure on a global level. And this is why so many of Sammartini’s finales are in a 3/4 or 3/8 dance metre, anticipating the much-misunderstood Tempo di Minuetto finale genre of later symphonies. Historically, cyclic organisation is inherent in the common practice in baroque concertos of ending the first movement on a dominant half-close so as to lead to a transitional slow movement (overture first movements also ended on the dominant). Sammartini consummated this tendency in two cyclic gems of his early period, symphonies nos. 37 and 73.

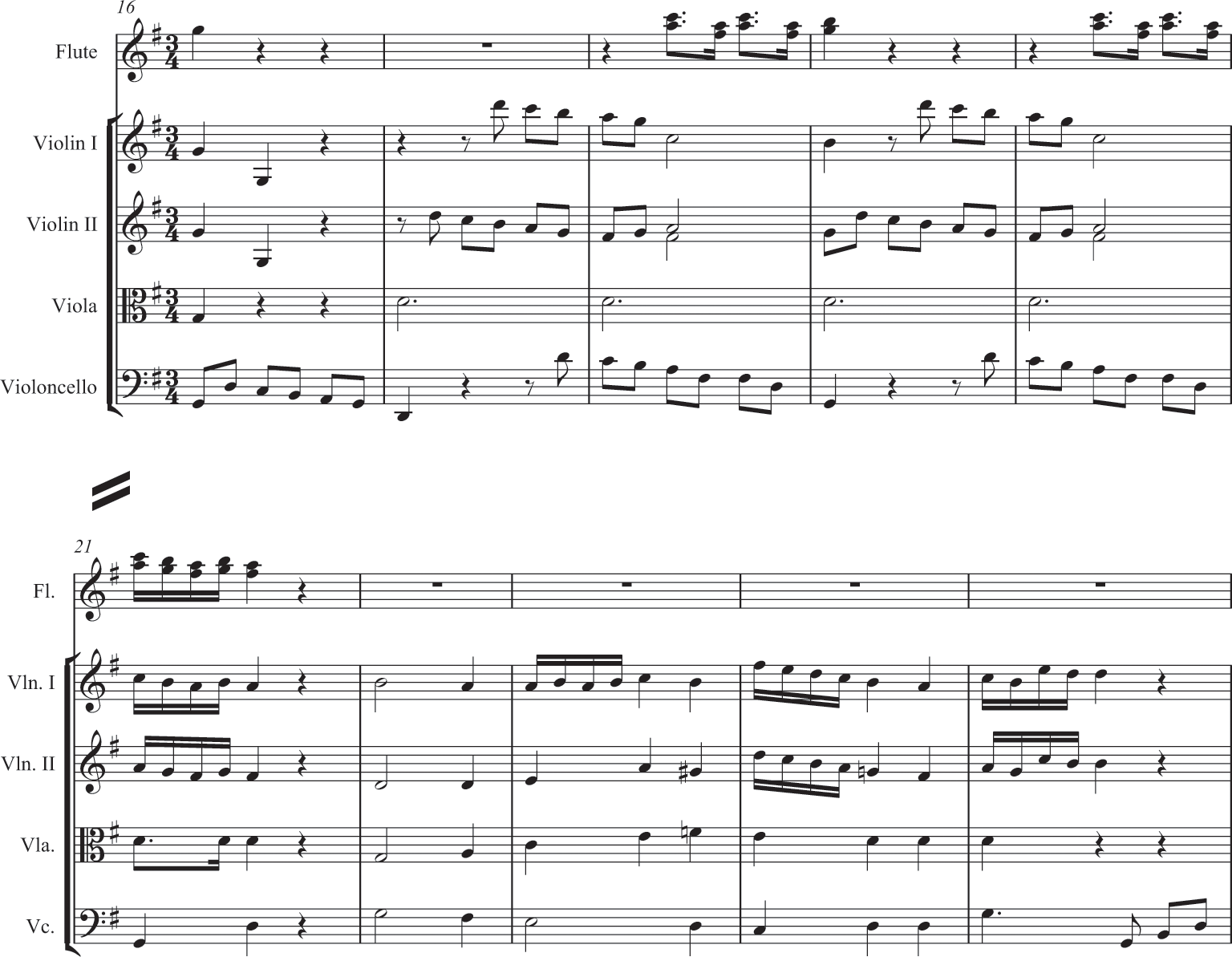

The first movement of No. 37 in F major implies sonata form but shifts all the signposts, resulting in music of extraordinary continuity. An otherwise clear medial caesura on V at bar 19, including a beat’s rest, is followed by a ritornello of the opening theme in G minor. A secondary transition leads to a closing theme in the dominant minor which spills without a break (no double bars or repeat signs) into an eleven-bar development. After a cadence on VI (a feature much-used by Haydn), the recapitulation compresses the exposition’s thirty-seven bars to just twenty-one. A half-close on V then tips the movement into an Andante in the same key. The Minuetto Allegro Finale begins with repeated descents from ![]() , taking up and fulfilling the contour of the first movement’s closing theme and thus affording the work’s first satisfying cadential closure (Examples 6.1a and b). The 3/8 Adagio appendix to the ‘Farewell’’s Finale works in similar fashion to resolve Haydn’s own cycle.12The development of No. 73/i in A major contains a 33-bar tonic-minor parenthesis which is a miniature sonata form in itself (Example 6.2). Set off texturally from the frame like a trio section (the violins subdivide and the bass drops out, as in many of Sammartini’s second groups), the section is a cantabile oasis remarkably like the D major ‘trio’ within the ‘Farewell’’s first-movement development. Sammartini’s trio is integrated thematically into the cycle: its lyrical material anticipates both the A minor Largo and the second part of the Finale, so that it is meaningful to speak of a thematic ‘narrative’ cutting across all three movements.

, taking up and fulfilling the contour of the first movement’s closing theme and thus affording the work’s first satisfying cadential closure (Examples 6.1a and b). The 3/8 Adagio appendix to the ‘Farewell’’s Finale works in similar fashion to resolve Haydn’s own cycle.12The development of No. 73/i in A major contains a 33-bar tonic-minor parenthesis which is a miniature sonata form in itself (Example 6.2). Set off texturally from the frame like a trio section (the violins subdivide and the bass drops out, as in many of Sammartini’s second groups), the section is a cantabile oasis remarkably like the D major ‘trio’ within the ‘Farewell’’s first-movement development. Sammartini’s trio is integrated thematically into the cycle: its lyrical material anticipates both the A minor Largo and the second part of the Finale, so that it is meaningful to speak of a thematic ‘narrative’ cutting across all three movements.

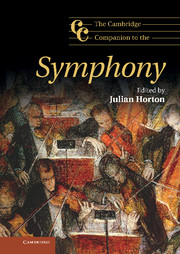

Example 6.1a Sammartini, Symphony No. 37, I, bars 66–9.

Example 6.1b Sammartini, Symphony No. 37, III, bars 1–4.

Example 6.2 Sammartini, Symphony No. 73, I, bars 42–7.

Contrasting a cadentially articulated and periodic finale with a more irregular first movement was Sammartini’s initial mode of unifying his symphonic cycles. Nevertheless, cyclic unity was increasingly traded off against the conventionalisation of sonata form in the first movements. This is the chief reason why such unity is more apparent in Sammartini’s earlier works. As second subjects were rendered more distinct, they also took on many forms: repeated fragmentary ideas (nos. 15, 26, 72, 73, 75), or a melody characterised by a contrast of mood and style and a dynamic shift to piano (nos. 26, 36, 38 and 41). Structurally, the second group may stabilise an irregular first theme through its sequential harmonic rhythm (nos. 43 and 44) or with a pedal point (No. 39). At the same time, cyclic unity is recuperated by making finales more monothematic; in the Allegro assai of No. 44, the first subject returns in the dominant, and thematic contrast happens within groups rather than between them.

As a rule, Sammartini’s recapitulations start with a shortened version of the first group; indeed, the entire recapitulation tends to be abbreviated. Moreover, the material itself is often radically rearranged, a technique Bathia Churgin calls ‘thematic interversion’.13For instance, in the first movement of No. 38 in F major, the positions of the T and S themes are swapped and their actual detail transformed.14 Both versions of S involve harmonic sequences, but the F–B♭–C–F sequence at bars 64–67 is much smoother than the unmediated triadic shifts (D–E–F–G) at bars 28–31 (Examples 6.3a and b).

Example 6.3a Sammartini, Symphony No. 38, I, bars 27–32.

Example 6.3b Sammartini, Symphony No. 38, I, bars 63–7.

Many of Sammartini’s apparent solecisms, pace Rosen’s insensitive critique, are strategic;15 they are deliberate infelicities to be resolved in the recapitulation. This processive attitude to form was taken up by Haydn, whose recapitulations also ‘knead out’ recalcitrant material in his expositions – what Hepokoski terms ‘refractory-material-to-be-worked-with’.16 Was Haydn, then, less than truthful in his comments to Griesinger and Carpani? The question is in any case immaterial, since in the years separating the two composers, Sammartini’s influence would have been transmitted through innumerable, indirect, pathways. So too with Mozart. He met Sammartini during the first two of his four visits to Milan (January–March 1770; October 1770–January 1771), but there is no record of Mozart actually having heard Sammartini’s symphonies. The influence – be it direct or indirect – is attested, rather, by Mozart’s Italianate symphonies themselves, such as K 74, 81, 84 and 95.

Stamitz

Insofar as the symphonies of Johann Stamitz (1717–57) sound more ‘symphonic’ than Sammartini’s, they reveal the capabilities of his virtuoso orchestra at the electoral court of Mannheim.17 They also reflect the increasing impact of the Italian overture; operas by Jommelli and Galuppi were staples at Mannheim, and Stamitz became even more Italianate after his year-long stay in Paris from 1754, where the ‘querelle des bouffons’ was raging. Aspects of this symphonic sound include massive texture, slow harmonic pace married to rhythmic drive, string tremolos and drum basses, dynamic variety and textural and timbral contrast due, in part, to the recruitment of pairs of oboes, flutes and horns both soloistically and within an independent wind section. Also important is the drastic simplification of the harmonic palette to the basic triads, so that root-position tonics and dominants resonate with pristine beauty, and the disposition of this sound-mass in symmetrical blocks of eight- and sixteen-bar phrases. All of this is evident in the opening of Stamitz’s Sinfonia Op. 4, No. 6 in E flat, one of his nine ‘late’, post-Paris, symphonies (Example 6.4).

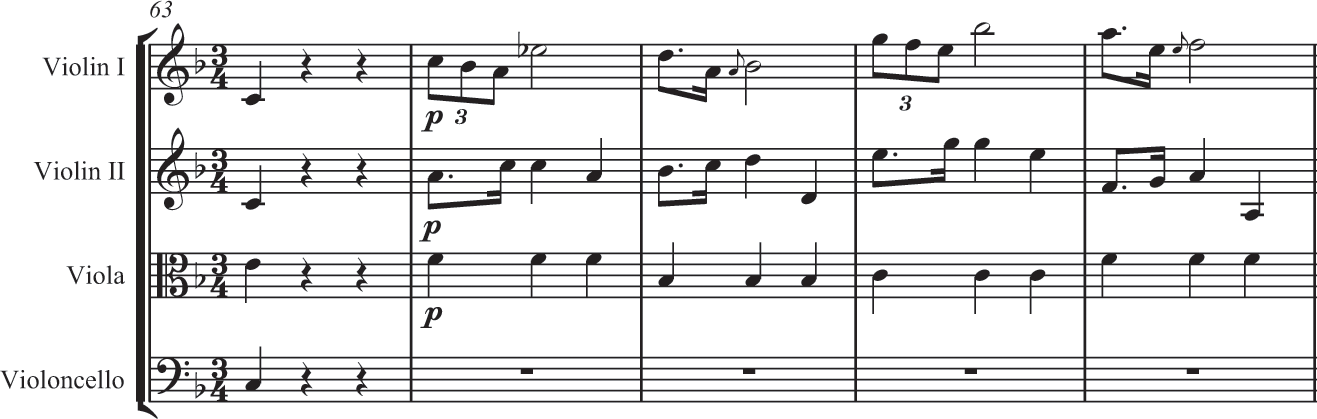

Example 6.4 Stamitz, Sinfonia Op. 4, No. 6, I, bars 1–18.

Stamitz’s most famous Italian borrowing – ironic, because it became the quintessential trade-mark of the Mannheim sound – was the orchestral crescendo, or ‘roller’ (Walzen), exemplified at bar 9 of the tonic group. The ‘roller’ was not just a dynamic swell but a package of features involving a rising melodic line, tremolo, harmonic acceleration and cumulative addition of instruments. Sonically sensational, it was used in opera for programmatic effect; for example, in the aria ‘Veggio il ciel turbato’ from Act I, Scene 13 of Jommelli’s Merope (1741), the crescendo portrays the surging sea. Stamitz rationalised the crescendos’ formal function. Thus the nine late symphonies adopt a ‘three-crescendo model’.18 Stamitz places a crescendo in the second phrase of the primary groups, at the start of the development and at the end of the recapitulation. Strikingly, this scheme can even be independent of the original thematic material, suggesting that it was the orchestral sound itself that was ‘thematic’ for Stamitz and his listeners, assuming the clear organisational role of three sonic pillars. This fact is even more impressive when we consider that accelerating phrase rhythm alone – epitomised by the logic of the Schoenbergian sentence – came to supersede the role of the crescendo. Crescendos are common at the start of Mozart’s early symphonies and are phased out on the path to the ‘Jupiter’’s opening sentence (the sheer absence of a Walzen here is the ‘Jupiter’’s most vivid historical marker). The shift from sound to phrase-rhythm – from Walzen to sentence – is not necessarily a qualitative evolution; in some respects, the former is more authentically ‘orchestral’.

In addition to energising the symphony’s sound-world, the overture also promoted greater formal continuity. As in a typical Jommelli or Galuppi overture, a late Stamitz symphony elides the articulating divide between the exposition and development (his early symphonic first movements are binary, with repeats); in any case, the increased length of the movements obviated the need for repetition. Strikingly, full recapitulations are more common in Stamitz’s early- and middle-period symphonies, whereas late recapitulations jettison the primary group. The extreme freedom of Stamitz’s recapitulations is directly inspired by Sammartini’s ‘interversion’ technique, extended by Stamitz to a kaleidoscopic extreme which anticipates the fluid permutations of Mozart’s piano concertos.19 In Stamitz as in Mozart, the thematic material flows beguilingly in between the bars of the periodic cage, creating a kind of ‘double perspective’. This effect is epitomised by Stamitz’s second groups. From one standpoint, Stamitz’s second groups are consistently more repetitive and periodic than Sammartini’s (from the 1742 Eumene onwards, the second group of every Jommelli overture is organised as 4+4 bars), and they are increasingly differentiated using solo oboe or flute textures. From another standpoint, the caesura between transition and second group (normally so clear in Sammartini) is often abrogated, relegating S to the status of an interruption of T, resumed when T powers on into the development. The eight-bar second subject (carried by oboes I and II) in Op. 4, No. 6 emerges seamlessly out of the transition and quickly sinks back into an orchestral tutti.

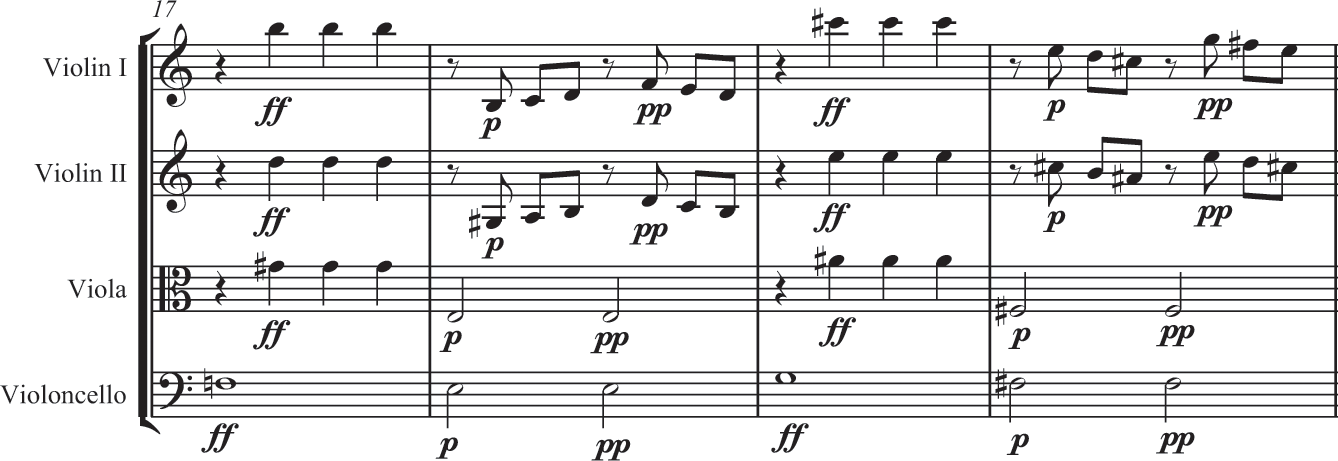

Where Stamitz does depart from the overture is in favouring a four-movement cycle. Of the twenty-nine middle symphonies, eighteen have four movements; all the late works insert a minuet and trio in third position. Hugo Riemann believed that it was Stamitz who put in place the foundations of the great German four-movement symphony.20 One such foundation was the concept of a slow movement as an enclave of subjectivity. The Adagio tempo of Op. 4, No. 6’s second movement is characteristically German, differing from Sammartini’s prototypical Andantes. Whereas Sammartini’s slow movements rarely escape the continuity of baroque Fortspinnung technique, Stamitz’s mosaic idiom proceeds as a chain of short-breathed motivic fragments. Individually, the motives encapsulate deep emotions; as a group, they unfold a terse drama. The operatic drama initiated by the ferocious unison gesture in bars 1–2 (Example 6.5a) leads, at the end of the exposition, to the sort of textural magic recognised by all Mozart lovers: a deceptively simple ostinato exchange of motives between violins I and II, underpinned by a pedal, creating a sublime stand-still. Stamitz invented this effect (Example 6.5b).

Example 6.5a Stamitz, Sinfonia Op. 4, No. 6, II, bars 1–5.

Example 6.5b Stamitz, Sinfonia Op. 4, No. 6, II, bars 21–3.

Stamitz also established the ‘Germanic’ version of the symphonic minuet as a concise internal dance movement with regular four-bar groupings, in contrast to the broader ‘Italian’ minuet (or Tempo di Minuetto) finale.21 Also typical in Op. 4, No. 6 is the Prestissimo Finale in duple meter. Its peculiar blend of ritornello and ‘reverse recapitulation’ technique keeps the pace moving: P returns initially in B flat (bar 79), followed by a tonic reprise of S (bar 106) and only at the end of the movement by a recapitulation of P in E flat. The Finale is a show-piece of orchestral virtuosity. Pace Riemann, second-generation Mannheim symphonists such as Cannabich reverted to the three-movement overture model. Which model affords a more unified cycle, three movements or four? The debate would continue into the 1780s.

The two streams (Bäche)

Johann Christian Bach

After making his reputation as a composer of Italian opera in Milan as a colleague of Sammartini during 1754–62, Johann Christian Bach (1735–82) settled in London in 1762, visiting Mannheim in 1772. A plausible, if counter-intuitive, argument has been made that the Austro-German classical style was the product of the British Enlightenment.22 Assimilating London’s cosmopolitan classicism, Bach invented many of the symphonic lineaments to which Mozart would cleave, following the eight-year-old composer’s visit to the city in April 1764 and his exposure to the six symphonies Op. 3 (published 1765). What Mozart’s Symphony in D, K 19, emulates from Bach’s Op. 3, No. 1 in the same key is a precisely calibrated procession of structural functions attuned to the rhetorical ‘beginning–middle–end’ model.23 Bach’s and Mozart’s first movements both open with Mannheim-like triadic flourishes designed to summon attention and circumscribe tonal space. Sequential transitions lead to lyrical second subjects for reduced forces and dynamics on a dominant pedal (Mozart’s theme is an exact parody of Bach’s). The second groups of both movements are completed by a succession of four discrete themes expressing varying degrees of closure, the series unfolding a dramatic arc learned from opera seria. Both expositions then proceed directly into a development with no double bars. Each development begins with an ostensibly new idea which subtly pulls together previous threads (a technique perfected by Sammartini), before slipping into the circle of fifths. Both recapitulations elide the first subject, like late Stamitz. Yet Bach’s form is poised and harmonious whereas Mozart’s bursts with jarring contrasts (such as the horrible forte A♯ which ignites the development at bar 46). Bach is the ‘classical’ artist; growth would confirm Mozart as the ‘sentimental’ one, according to Schiller’s dichotomy. The distinction needs to be stressed, given the propensity to think of Mozart as ‘filling’ Bach’s perfect if ‘empty’ vessels with ‘spirit’.

Bach’s second set of symphonies, the Op. 6 of 1770, develop in polarised directions. On the one hand, the perfection is rendered more concise: opening gambits are encapsulated; the plurality of second groups is extended to similarly heterogeneous first groups; and the long sequential transitions are abbreviated into brutally efficient modulatory gestures. On the other hand, Bach’s poise toys with stasis, compounded as much by the blossoming of his lyrical gift as by an over-articulation of formal junctures. Epitomising the latter is a tendency to cadence at the end of the retransition – a cardinal sin singled out by Rosen for special reproof, since it cuts the development off from the reprise.24 Thus the development of No. 3 in E flat settles gently to a repeated cadence in B flat at bars 72–6, and the recapitulation enters like a da capo or ritornello. But Rosen is quite wrong: what this example demonstrates is the persisting vitality of Sammartini’s tri-ritornello model, indebted to the concerto (Ritornello 1: I–V; Ritornello 2: V–vi or iii; Ritornello 3: I–I), which separates out the three sections of Bach’s sonata form into graceful Doric columns.

Concision and lyricism culminate in the summa of Bach’s art, the three of the six Op. 18 ‘Grand Overtures’ written for double orchestras (1774–7). Bach used the term ‘overture’ interchangeably with ‘sinfonia’; indeed, some of the Op. 18 set were originally operatic overtures, showing that the two three-movement genres had now converged. Bach’s double orchestra, supplying his music with extra resources of sonic richness and concertante dialogue, also allows him to draw in the third genre of concerto. The synergy between tutti and soli in Op. 18 is much suppler than in Haydn’s own experiments with concertante symphonies.25 No. 3 in D major – the finest of the set – was originally the overture to Endimione, and it demonstrates the overpowering sensuality of Bach’s textures. Concision is epitomised in the gravity-defying brevity of the Allegro’s seventeen–bar first group, which supports an expansive exposition of 66 bars. The exposition’s ‘transition space’ has been filled up with stable periodic melodies; the first one (bars 18–25) is remarkable because it sits on the new tonic pedal (A), rather than the more conventionally unstable V of V (E). (The ‘real’ second subject, at bar 51, is quite different.) The premature A major theme works perfectly well in Bach’s sui-generis structure, although it can’t fully be accounted for by modern sonata-form theories.

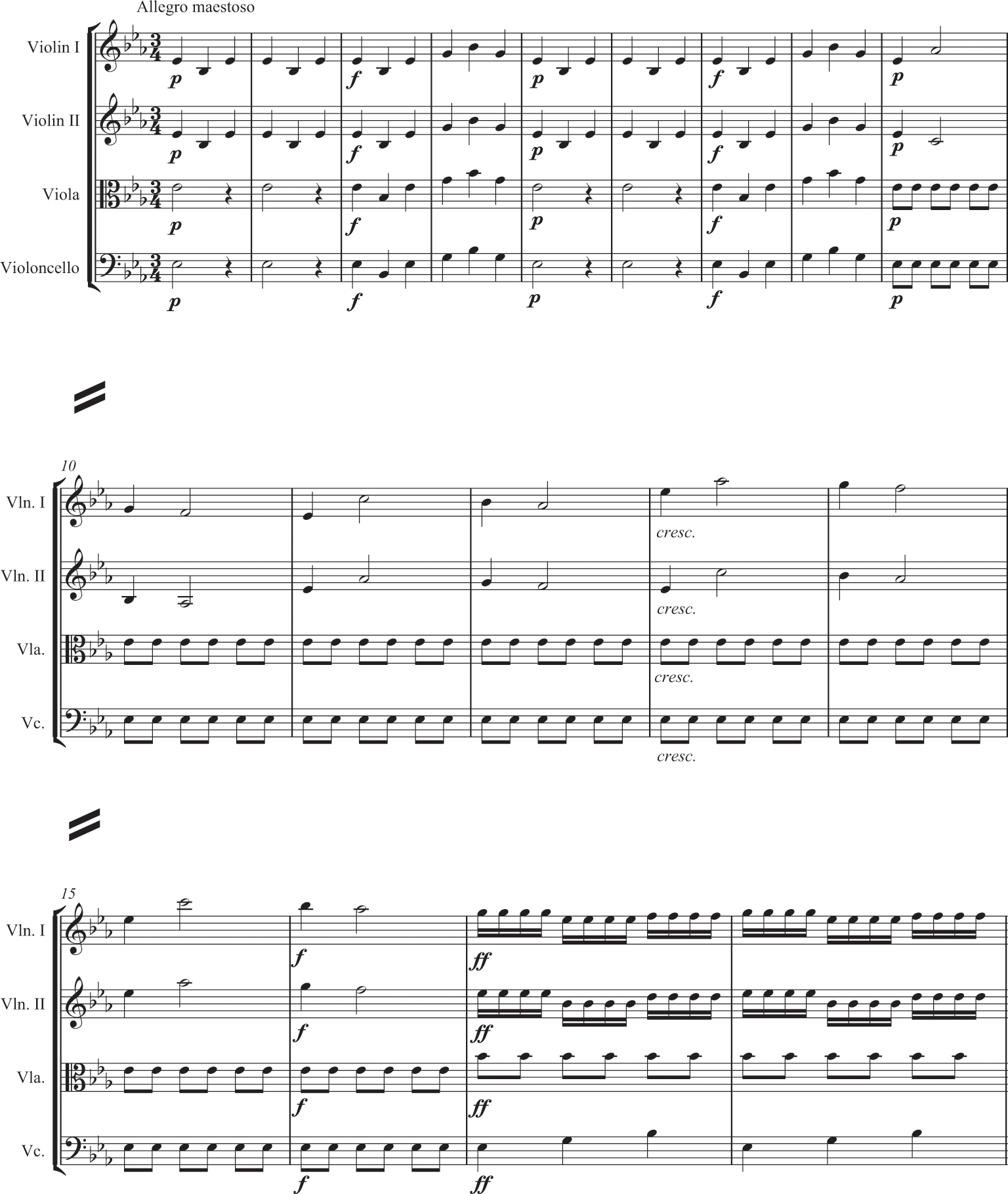

The melodic genius of the central Andante, in ABA song form, equals Mozart’s, complete with surprising chromatic colourings. Both thematic groups in section A sit in the tonic G major, and Bach keeps things moving with a sure-footed harmonic acceleration from a leisurely opening melody (Example 6.6a) to the much faster contrasting idea at bar 22 (Example 6.6b). The artistry lies in the exquisite care by which this new melody both arrests and follows through the deceptively static flurry of quavers at bars 16–21 (canonically exchanged scales), a passage which works equally well above its alternate tonic and dominant pedals. Only Mozart could emulate this paradoxical blend of motion and standstill.

Example 6.6a J. C. Bach, Symphony Op. 18, No. 3, II, bars 1–4.

Example 6.6b J. C. Bach, Symphony Op. 18, No. 3, II, bars 16–25.

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach

What Johann Christian learnt from his older brother during his apprenticeship in Berlin in 1750 resurfaces most openly in the dark rhetoric of slow movements such as the Andante of Op. 6, No. 6 in G minor.26 This is a metaphor for the subterranean quality of Emanuel Bach’s own symphonies, whose essentially private, chamber-music-like character was buried by the dominant public style celebrated even by north Germans such as J. A. P. Schulz. Schulz’s 1774 article on the symphony in Sulzer’s Allgemeine Theorie der Schönen Künste reports that the genre ‘is excellently suited for the expression of the grand, the festive, and the noble . . .; to summon up all the splendour of instrumental music’.27 This public style is evinced by Johann Gottlieb Graun’s (1702–71) one hundred concert symphonies, which established the genre in Berlin. But on the other hand, some of Schulz’s prescriptions fit Bach’s mannerism like a glove: ‘great and bold ideas, free handling of composition, seeming disorder in the melody and harmony, strongly marked rhythms of different kinds . . .; sudden transitions and digressions from one key to another, which are all the more startling the weaker the connection’. The question, then, is whether a symphony is still a symphony when ‘seeming disorder’ is not played out against a framework of public communication – ‘the grand, the festive, and the noble’.

The question devolves to the idiosyncratic way Emanuel Bach’s eighteen symphonies (eight for Berlin in 1741 and 1755–62; ten for Hamburg after 1767) treat classical form, particularly the ‘beginning–middle–end’ rhetorical model perfected by Johann Christian. Sonata form is present in the first movement of Bach’s Symphony in C major, W 182/3, the third of a set of six four-part string symphonies composed in Hamburg in 1773. Yet it is masked by a quasi-postmodern cross-current of baroque and proto-Romantic styles. The surface form is modelled on Tartini’s concerto-grosso practice: a tutti ritornello recurs in the dominant at the end of the second group, and in the tonic at the close of the movement, but conspicuously not at the structural return of the tonic. The refrains, plus the intervening soloistic passage work, completely detract from the sonata infrastructure. Conversely, the surface is pitted with rhetorical expressive effects associated with the fantasy genre, as in the dramatic A flat interruption at bar 6 of the first movement (Example 6.7a). Fantasy also inspires Bach’s cyclic ambitions: he unites all three movements as sub-sections of a single process. It is at this level that something very sophisticated happens. The run-on slow movement – typically a bridge in a Tartini concerto – is prompted by the interrupted cadence at the sixth bar of the ritornello, the chromatic shock now raised from an A♭ to a B♭ so as to bring back the B–A–C–H motive (Example 6.7b).

Example 6.7a C. P. E. Bach, Symphony in C, W 182 No. 3, I, bars 1–6.

Example 6.7b C. P. E. Bach, Symphony in C, W 182 No. 3, I, bars 124–8; II, bar 1.

Bach confirms the potential for a slow movement to become a prolongation of a cadenza; the Adagio is also a forensic through-composed excursus on ideas from the first movement – a kind of global development section. The chief idea is nothing less than the B–A–C–H (B♭–A–C–B♮) motive – an inconsequential bass pattern in the Allegro’s transition (bars 16–19) now promoted to head position in the Adagio.28 The Adagio builds up to a dramatic face-off between the motive, fortissimo, in the bass, and empfindsam violin appoggiaturas, piano (Example 6.8a), discharging into an Allegretto rounded binary dance Finale, which transmutes the B–A–C–H motive into a charming galant melody (Example 6.8b).

Example 6.8a C. P. E. Bach, Symphony in C, W 182 No. 3, II, bars 17–20.

Example 6.8b C. P. E. Bach, Symphony in C, W 182 No. 3, III, bars 1–3.

In one sense a literal exorcism of Emanuel Bach’s father, the effect also points to his true successor. For as a cyclic ‘story’ of an abstract interval pattern, the symphony is a model for Beethoven’s Grosse Fuge: note the eventual domestication of Beethoven’s subject into a dance tune in the fugue’s Allegro molto Finale. This abstraction – appealing much later to a Beethoven, if not to Bach’s immediate contemporaries – is epitomised by the Finale’s formal concentration, whose density is out of kilter with the galant materials. This is music for Kenner rather than Liebhaber, demanding a sharpness of attention suited to the intimate performance spaces of chamber music rather than to ‘symphonies’ proper. The most exquisite detail comes at bar 47 (Example 6.9). ‘False reprise’ would be a misnomer for the tonic recapitulation which interrupts an E minor cadence at bar 47 (and corrected by the ‘true’ reprise of bar 61): Bach intends an effect not of plausibility but of shock. The frailty and insularity of this two-bar reprise, hedged on either side by darkness, is broadly suggestive of how Bach’s symphonic oeuvre as a whole is overwhelmed by an enormous subjectivity.

Example 6.9 C. P. E. Bach, Symphony in C, W 182 No. 3, III, bars 47–51.

The Swedish Mozart and Haydn’s wife

Joseph Martin Kraus

What a loss is this man’s death! I own a symphony by him, which I keep in memory of one of the greatest geniuses I have ever known . . . Too bad about that man, just like Mozart! They both were so young [when they died]. Joseph Haydn.29

The culture industry and the cult of genius have conspired to keep many first-rate classical composers in obscurity. Listeners who are lucky enough to come across the music of Joseph Martin Kraus (1756–92), perhaps courtesy of Naxos’s pioneering series of The 18th-Century Symphony, may be shocked by just how good he is. Born in Miltenberg-am-Main, and educated at Mannheim, Kraus published a treatise Etwas von und über Musik as a contribution to a Sturm-und-Drang literary circle called the Göttinger Hainbund, joined the court of Gustavus III of Sweden in 1778, eventually becoming Kapellmästare, interrupted his service with a Grand Tour of the European musical capitals (1782–7), during which he met Gluck, Haydn and Mozart, died of tuberculosis in 1792, and left us with twelve surviving symphonies. The symphony singled out by Haydn is the C minor (1783), VB 142, the greatest in that key before Beethoven’s, and deserving of Haydn’s praise. Yet the epitaph ‘the Swedish Mozart’ which clung to Kraus, due to the two composers’ nearly exact contemporaneity, is inaccurate. More akin to an ‘anti-Mozart’, Kraus extrapolated different symphonic tendencies compounded variously from Haydn’s Sturm-und-Drang works of the 1770s, C. P. E. Bach’s fantastical idiom, Stamitz’s formal models and most of all Gluck’s rhetorical directness, whose rawness Kraus disciplined in ways which evoke the sound-world of Beethoven’s heroic style.30

The Symphony in C minor is doubly interesting because it reworks in Vienna elements of the Symphony in C-sharp minor VB 140, written in Sweden a year earlier in 1782, so allowing us to encapsulate matters of ‘stylistic maturity and regional influence’.31The slow introduction to VB 140 develops out of the opening phrase of Gluck’s Iphigénie en Aulide; VB 142 spins Gluck’s material far further (Example 6.10a) and conceives dark orchestral sonorities which would never have been heard before (Example 6.10b). VB 142 loses the earlier symphony’s minuet (following other late-Mannheim composers such as Cannabich) and entirely recomposes the outer movements in a deeply satisfying cyclic design. The essence of Kraus’s design is that, in the tradition of Sammartini, Stamitz and Emanuel Bach, the form of the finale functions as a cyclic resolution.

Example 6.10a Kraus, Symphony in C minor, VB 142, I, bars 1–4.

Example 6.10b Kraus, Symphony in C minor, VB 142, I, bars 24–8.

Like early Stamitz, the first movement of the C-sharp minor Symphony is bipartite with repeats, the recapitulation of P being delayed until the end. VB 142, conversely, follows late Stamitz in abrogating the articulation between exposition and development and restoring a tonic recapitulation. Another late Stamitz procedure much in evidence in Kraus even before 1782 is to eclipse S with the transition. In the Symphony in C major VB 138 (1781), a strategically trite secondary theme is thrown aside when a fragment of T (bars 33–4) returns and explodes (bars 63–73). This ‘outbreak’ principle – suggesting a composer bursting through received forms – is taken to another level in VB 142. The most substantial passage in the exposition is the sixty-two-bar-long transition (bars 56–117), book-ended by theatrically emphatic caesuras. Whereas the fifty-five-bar-long primary group is equally weighted, the second group in E flat occupies a mere twenty-nine bars (bars 118–45): as in Stamitz, it is an ‘oasis’ between T and the development.32 The recapitulation recasts the form radically, eliminating T entirely, thereby cutting the exposition’s material from 145 bars to 57. The form is not just foreshortened but rationalised: in terms of modern sonata theory, a ‘tri-modular block’ (an exposition with two structural caesuras) is normalised – the elision of T notwithstanding – into a recapitulation with a single caesura between P and S.33 This ‘normalisation’ is echoed at a global level by the traditional and concise sonata form of the Finale, including its double bars and repeats. The foreshortening gesture is recursive at three levels – exposition; first movement; cycle – projecting the Sturm-und-Drang telos in a uniquely intricate structure.

Tri-modular blocks were common in other Viennese symphonies by Wagenseil and Dittersdorf,34but were taken up in orchestral music by Haydn and Mozart much later than by Kraus, who learnt the device ‘at source’ from Mannheim.35The C minor Symphony’s extraordinarily expansive transition is reminiscent of that in the first movement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto in C minor, K 491 (1786), which we know, through studies of the autograph, was interpolated into the exposition at a later stage. Perhaps after hearing VB 142? Did the anti-Mozart influence Wolfgang Amadeus?

Luigi Boccherini

Renewed interest in the chamber music of Boccherini (1743–1805) should lead to his re-evaluation as a symphonist of equal stature to middle-period Haydn (1775–92; between the Sturm und Drang and ‘London’ symphonies).36 Despite artistic isolation at Arenas and Madrid, Boccherini corresponded with the Esterhaz-bound Haydn, and the two composers were coupled to the former’s detriment; the nineteenth-century violinist Giuseppe Puppo christened him ‘Haydn’s wife’, due to the perceived effeminacy of his charming style. Yet their affinity was reciprocal in a deeper way. A born architect and musical logician, Haydn only learned to compose melodies in the ‘operatic’ symphonies of the late 1770s;37 a melodic genius from the outset, Boccherini sorted out his formal problems with the Op. 21 symphonies of 1775. The masterworks from the 1780s – particularly the symphonies opp. 35 and 37 – give the lie to the standard epithet, gleaned from the chamber music, that Boccherini was a master of rococo and static ‘detail’ rather than ‘broad effect’.38 It is the broadness of their style, in fact, which suggests comparison with later symphonic masters of repetition and block contrast, such as Schubert and Bruckner, together with a captivating sensuousness and almost luminescent colour. It is extraordinary, then, that this progressive aspect is extrapolated from Sammartini – whom Boccherini met in Milan in 1765.39 It brings this ‘evolutionary’ story full circle.

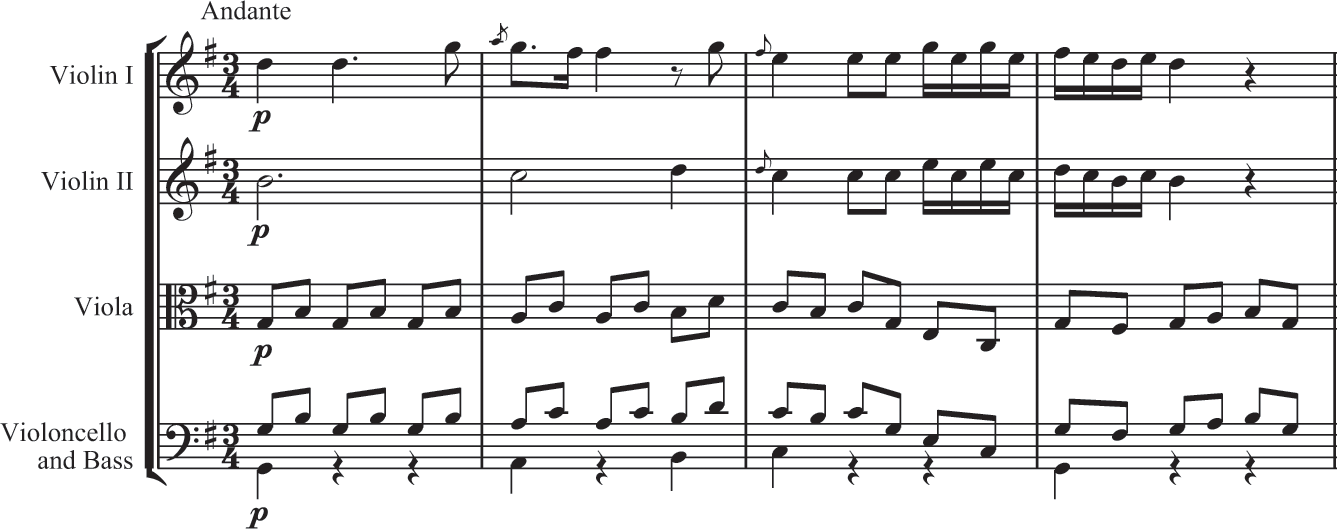

Boccherini and Sammartini share many characteristics: a sensit-ivity for orchestral string textures, often focussing on first and second violins either in octaves or in double counterpoint; a fidelity to the concerto strand of the symphonic fabric, evinced in Boccherini by an effortless accommodation of concertante dialogue; broad major/minor contrasts (see Sammartini’s symphonies nos. 7, 14 and 65); and perhaps most of all, a liking for cyclic unity. Of all galant or classical symphonists, Boccherini is by far the most preoccupied with patent thematic relationships between movements. A theme or even an entire section or movement may recur (e.g. the opening slow introduction returns before the Finale in Op. 12, No. 4). A particularly sophisticated case is the Andante of Op. 35, No. 2 in E flat, where a new theme, which usurps the expected reprise of the opening C minor first subject (Example 6.11a), returns a few bars later (Example 6.11b) as the first subject of the Finale (many of Beethoven’s finales would also be intimated in the middle movements).

Example 6.11a Boccherini, Symphony in E flat, Op. 35, No. 2, II, bars 39–44.

Example 6.11b Boccherini, Symphony in E flat, Op. 35, No. 2, III, bars 1–5.

Cyclic recurrences throughout Symphony No. 23 in D minor, Op. 37, No. 3 (1787) are particularly extensive and audible, because they correlate with the D minor/major alternation across the work: elements of the four-bar introduction return in the minore sections of the Minuetto, Andante amoroso and Finale.

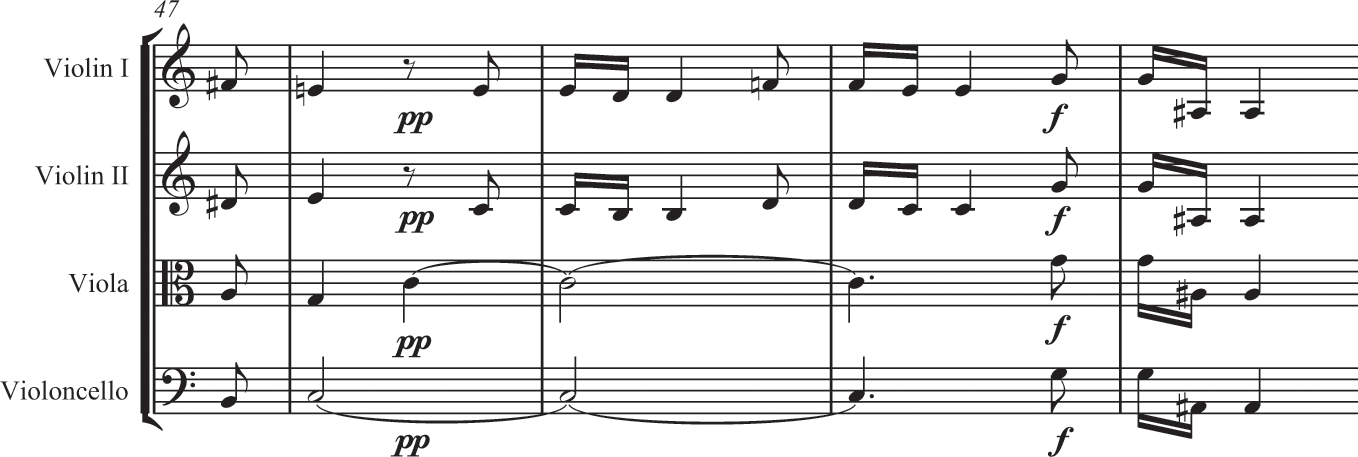

Op. 37, No. 3, one of the high-points of Boccherini’s maturity, co-opts major/minor opposition in a patchwork of contrasts, encapsulated in the four-bar phrasing for which he is often denigrated. Yet it is precisely the Symphony’s periodicity which makes the non-mediated juxtaposition of textural and tonal blocks so effective, and the overall form so compellingly efficient. The pianissimo four-bar D minor introduction (Example 6.12a) is succeeded with a fortissimo outburst of D major figuration (Example 6.12b). Four bars later, the D minor material returns, succeeded after four more bars by an equally unmediated block of F major. Although the Symphony is topped, tailed and punctuated by episodes in D minor, it is not really ‘in’ D minor; rather, the quality of the mode is rendered thematic in itself. Equally thematic is the delicious textural effect at bar 5 (the violin octaves, which Boccherini made his own, actually originate in mid-century orchestral Viennese idiom).40 Paradoxically, this outburst captures our attention while never returning again in the movement (like so many opening gambits by Stamitz and Domenico Scarlatti); the recapitulation pivots on the return not of the D major theme but of the F major block from bar 13, ingeniously reinterpreting the harmonic non sequitur within the primary group (the shift from the chord of A to F) as a Sammartini retransition (Example 6.13). That is, Sammartini’s convention of ending his developments on V of VI is utterly transmuted here, allowing Boccherini to get away with a breathtaking reprise in F, the mediant key. The orchestra is used to project keys as fields of colour; the technique points to the nineteenth century, but its roots are in the Italian galant. Without succumbing to Emanuel Bach’s hermetic intellectualism, Boccherini applies formal experiments more associated with chamber music to the popular symphonic style – something even the Haydn of the Op. 76 string quartets never managed to achieve.

Example 6.12a Boccherini, Symphony in D minor, Op. 37, No. 3, I, bars 1–4.

Example 6.12b Boccherini, Symphony in D minor, Op. 37, No. 3, I, bars 5–6.

Example 6.13 Boccherini, Symphony in D minor, Op. 37, No. 3, I, bars 63–4.

Boccherini’s Op. 7 in C (1769) is a Symphonie concertante spotlighting two violins and a cello as soloists. Op. 10, No. 4 (1771) is essentially a guitar concerto, and the Op. 12 symphonies of 1771 were termed Concerti a grande orchestra. Even a late symphony such as Op. 37, No. 4 in A is designated Sinfonia a più istromenti on the autograph. Where a concerto rubric is not indicated, as in Op. 37, No. 3, concertante obbligato writing is flexibly incorporated within episodes such as the second subject group (as in the two solo violas and solo bassoon of bars 26–31).

In the right hands, a concertante symphony was as viable as a ‘regular’ symphony. Nothing about the evolution of the early symphony was inevitable. Written from the standpoint of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, the story of the symphony suggests that the concerto was entirely digested. The view from Madrid, Stockholm, Hamburg, London, Mannheim and Milan is quite different, however, indicating that this evolutionary story could have moved – and indeed did move – in a number of alternative directions.

Notes

1 , A Catalogue of 18th-Century Symphonies, vol. I: Thematic Identifier (Bloomington, 1988).

2 , The Classical Style (London, 1972), 19.

3 , The Instrumental Music of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (Ann Arbor, 1984), 2.

4 , The Symphonies of Johann Stamitz: A Study in the Formation of the Classic Style (The Hague:, 1981).

5 Ibid., 110.

6 , Haydn’s ‘Farewell’ Symphony and the Idea of Classical Style: Through-Composition and Cyclic Integration in His Instrumental Music (Cambridge, 1991).

7 For an opposing view, see , ‘Zur Vorgeschichte der Symphonik der Wiener Klassic’, Studien zur Musikwissenschaft, 43 (1994), 64–143.

8 , Critischer Musikus (Hamburg, 1737–40): ‘Sie mit einer grössern Freyheit, was so wohl die Erfindung, als die Schreibart, betrifft, ausgearbeitet werden können’ (15 December 1739), 622.

9 All these works are included in , ed., The Symphonies of G. B. Sammartini, vol. I: The Early Symphonies (Cambridge, Mass., 1968).

10 Cited in Bathia Churgin, ‘The Symphonies of G. B. Sammartini’, 2 vols., (Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, Reference Churgin1963), 10. The following discussion is indebted to Churgin’s pioneering study.

11 and , Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York and Oxford:, 2006). Sammartini and Stamitz show that the authors’ cast-iron law that ‘if there is no medial caesura, there is no secondary theme’ (p. 52) is quite simply wrong on historical grounds.

12 See Webster, Haydn’s ‘Farewell’ Symphony and the Idea of Classical Style, 104–10.

13 Churgin, ‘The Symphonies of G. B. Sammartini’, 220.

14 Henceforth: P = primary theme; S = secondary theme; T = transition.

15 See , Sonata Forms (New York, 1988), 140–3. The brusque voice-leading in Symphony No. 6, bars 6–9, which Rosen finds ‘unbelievably ugly’ (p. 141), nevertheless comports with the unusual brevity (10 bars) of the first group.

16 , ‘Beyond the Sonata Principle’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, 55 (2002), 91–154, this quotation 128.

17 Other members of the Stamitz School include F. X. Richter (1709–89), Anton Fils (1733–60), Christian Cannabich (1731–91), Carl Joseph Toeschi (1731–88), Franz Beck (1734–1809), as well as Stamitz’s two sons, Carl (1745–1801) and Anton (1750–1809).

18 See Wolf, The Symphonies of Johann Stamitz, 299.

19 Ibid., 106.

20 , Denkmäler der Tonkunst in Bayern, vol. VII/2 (1906), ‘Einleitung’, i.

21 See , Die Theorie der Sinfonie und die Beurteilung einzelner Sinfoniekomponisten bei den Musikschriftstellen des 18. Jahrhunderts (Leipzig, 1925), 36–7.

22 See , London und der Klassizismus in der Musik: De Idee der ‘absoluten Musik’ und Muzio Clementis Klavierwerke (Stuttgart, 2002).

23 See , Playing with Signs: A Semiotic Interpretation of Classic Music (Princeton, 1991), 52.

24 According to Rosen, ‘One could compile a large anthology from 1770 on of ways to avoid a cadence [on vi] at the end of the development’ (Sonata Forms, 270). But in J. C. Bach’s hands, that wasn’t the point.

25 See for instance Haydn’s Sinfonia concertante in B flat, Op. 84, Hob. I/105.

26 Reflecting the popularity of minor-mode symphonies in the 1770s (by Vanhal, Ordonez, as well as Mozart’s first G minor symphony, K 183 [1773]), Op. 6, No. 6 is also a salutary reminder that the so-called ‘Sturm-und-Drang’ manner was as much a continuation of Sammartini’s style (e.g. his Symphony No. 9 in C minor) as the invention of north-German intellectuals.

27 , ‘The Symphony as Described by J. A. P. Schulz (1774): A Commentary and Translation’, Current Musicology, 29 (1980), 7–16, this quotation 11.

28 Bach uses the motive throughout his career, as in the Piano Trio in A minor, W 90/1, bars 63–6, and the Flute Concerto in D minor, H 426, bars 75–8. See Schulenberg, The Instrumental Music of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, 41–2.

29 Cited in , ‘Stylistic Maturity and Regional Influence: Joseph Martin Kraus’ Symphonies in C-sharp minor (Stockholm, 1782) and C minor (Vienna, 1783)’, in and , eds., Studies in Musical Sources and Style: Essays in Honor of Jan LaRue (Madison, 1990), 381–418.

30 The exception – Kraus’s paraphrase of a march from Idomeneo as part of his Riksdagsmusik (VB 154) – is revealing, since the opera is Mozart’s most Gluckian work. See , Dramatic Cohesion in the Music of Joseph Martin Kraus (Lewiston, 1989), 329.

31 See A. Peter Brown ‘Stylistic Maturity’.

32 Brown’s analysis in ‘Stylistic Maturity’ is misconceived; without reason, he calculates S as sixty-four bars rather than twenty-nine (p. 393).

33 For ‘tri-modular blocks’, see Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 170–7.

34 Ibid., 171.

35 Wolf, The Symphonies of Johann Stamitz, 151, 199 and 272.

36 For a study of the chamber music, see , Boccherini’s Body: An Essay in Carnal Musicology (Berkeley, 2006).

37 , ‘When Did Haydn Begin to Write Beautiful Melodies?’, in , and , eds., Haydn Studies (New York, 1981), 358.

38 Christian Speck and Stanley Sadie, ‘Boccherini’, in , ed., The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd edn (London, 2001), 749–64.

39 See , ‘Sammartini and Boccherini: Continuity and Change in the Italian Instrumental Tradition of the Classic Period’, Chigiana, 43 (1993), 171–91.

40 , Music in European Capitals: The Galant Style, 1720–1780 (New York, 2003), 981–2.