3 Other classical repertories

It is symptomatic of our perception of the eighteenth-century symphony that this part of the volume has been divided into ‘The Viennese Symphony 1750 to 1827’ and ‘Other Classical Repertories’, a division that reflects our preoccupation with the path the eighteenth-century symphony took en route to Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. Although no one will quarrel with the Viennese trinity’s pre-eminence as symphony composers, the focus on their roots and influences has done scant justice to the symphonic cornucopia that the century produced.1Estimates of the number of symphonies composed during the century range up to 20,000, and even a brief sampling reveals an almost bewildering variety of formats (from one up to seven or more movements), textures (ranging from fugal to completely homophonic), orchestration (from three-part strings on up) and formal procedures. Moreover, we have mostly paid attention to the ‘concert symphony’, a designation not used until the late eighteenth century, and have tended to define the ‘real’ or ‘mature’ symphony as a serious, four-movement work for an orchestra of strings and winds, a definition that excludes or marginalises much of the repertoire. This repertoire reflects the eighteenth century’s conception of the symphony as an instrumental work that could be used in the theatre (to precede an opera), in church (as Gradual music in the Catholic mass, for example), or in the chamber, where it generally served to open a concert. Although certain characteristics were typically associated with particular functions (i.e. forte, tutti openings for opera sinfonie), the fact remains that opera sinfonie frequently appeared in concerts, and ‘chamber’ symphonies (or movements of them) often served as Gradual music. For the eighteenth century, a sinfonia was a sinfonia, so if we wish to explore the genre fully, we would do well to consider all of its manifestations.2

What follows might be described as a ‘socialist’ history of the symphony. It identifies no ‘major figures’; it does not trace influence or connections; it does not chronicle innovations or attempt to identify who did what first. Instead, it views symphonic composition as a collective enterprise in which thousands of composers participated; by taking this approach, I hope to expand the slender standard narrative thread into a complex tapestry of colours and patterns. Because of space limitations I have narrowed my focus and have concentrated on form, structure and expression, and the ways they interact with texture and orchestration.3 I do not claim that my narrative is better than the standard one; merely that it shows us different things and perhaps makes us ask different questions.

Regions of composition

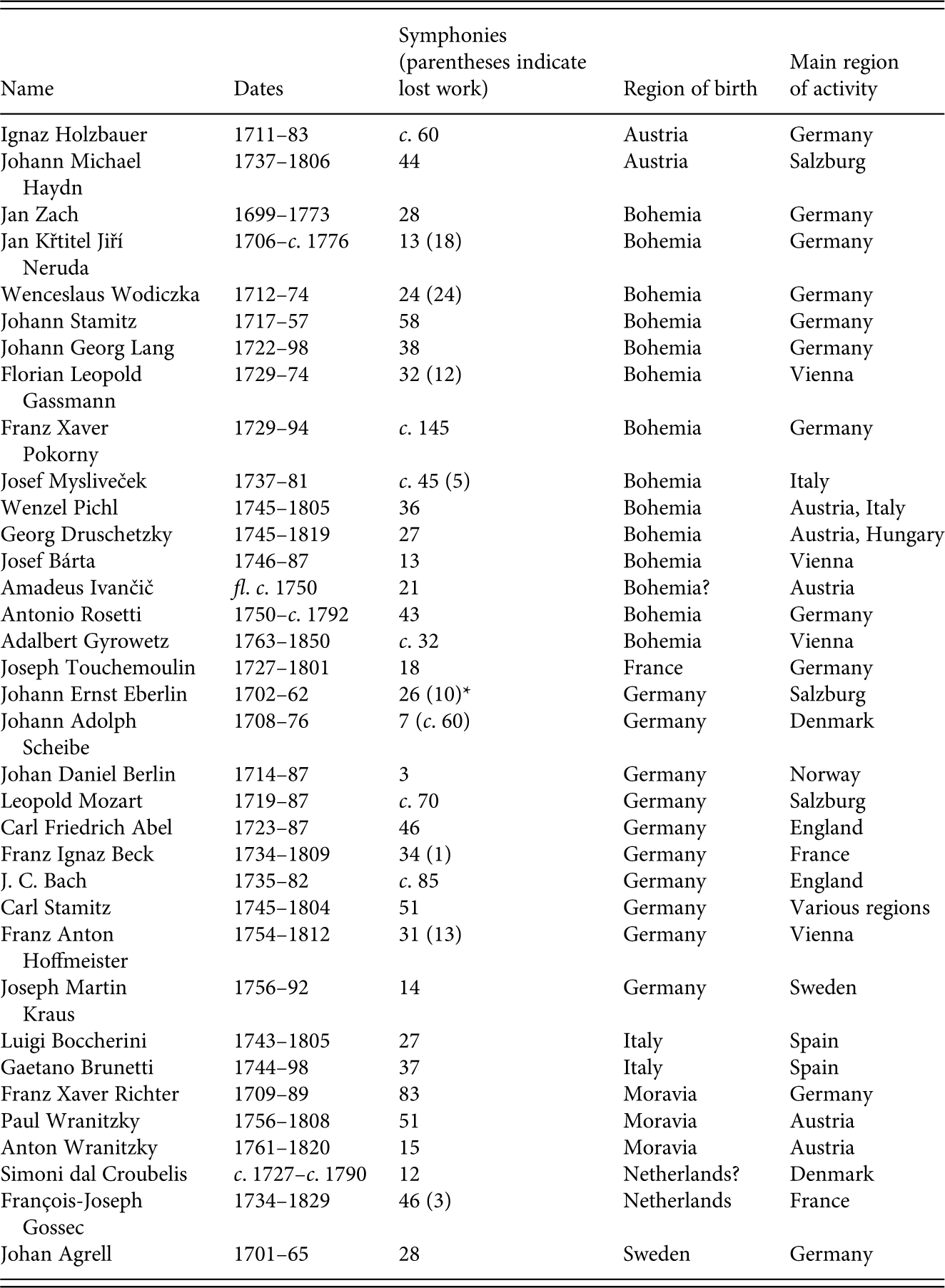

The symphony was found all over Europe as well as in lands where European culture was imported, and the composers themselves were a peripatetic lot. Italians and Bohemians, and to a lesser extent musicians from the German states, could be found everywhere (see Table 3.1). Luigi Boccherini (1742–1805) and Gaetano Brunetti (1744–98) both abandoned their native Italy for service in Spain; the Bohemian Josef Mysliveček (1737–81) spent much of his career in Italy; and his compatriot Johann Stamitz (1717–57) established his reputation in the palatinate of Mannheim, in southern Germany. The Mannheim-born Franz Beck (1734–1809) was active in France; the Swedish-born Johan Agrell (1701–65) in Kassel and Nuremberg; and the Scotsman Alexander Reinagle (1756–1809), of Austrian descent, immigrated to Philadelphia, in the newly formed United States. Such travels make a narrowly focussed study of ethnic or regional characteristics in symphonic composition tricky and perhaps of questionable value, although some differences in regional preferences and patterns of cultivation can be identified.

It is useful to distinguish between the composition and the cultivation of the symphony. For most of the century, composition was done by resident composers at courts or aristocratic households and thus occurred in relatively few places. These composers wrote for a specific orchestra and often for a specific occasion, even though their symphonies might later travel to other places in manuscript copies or in prints (often pirated). Cultivation was done by the thousands of institutions (including courts with resident composers) who purchased or otherwise acquired symphonies for performance at their concerts or celebrations or theatres or church services. These places created the demand that sparked the century’s symphonic fecundity. In the early part of the century, most symphonies were distributed in manuscript parts, often acquired during the course of travel. After the middle of the century, distribution channels increasingly ran through music publishers and music sellers, most of whom offered both manuscript and printed parts and were eager to sell works that would have a wide market, a point to which I shall return later.

Table 3.1 Selected immigrant composers of symphonies

In Italy, the opera sinfonia – generally in three movements until the one-movement form emerged in the late 1770s – remained a major outlet for Italian symphonic creativity for most of the century. Opera sinfonie by composers like Niccolò Jommelli (1714–74) can be found in eighteenth-century symphony collections throughout the continent. The three-movement form, well established by the 1730s, favoured first movements with a noisy primary theme using tutti strings and winds leading to transitions with tremolos and crescendos, quieter contrasting second themes and bustling closing sections. The melody-based slow movements, often in the parallel minor, gave way to quick and lively finales, frequently in triple meter. The ceremonial function of the opera sinfonia meant that it was not – and indeed should not – be tied to the operatic subject (something never understood or acknowledged by eighteenth-century German writers), an approach that meant it could easily be transferred to the chamber, or even to the church. Early Italian sinfonie originally intended for chamber or church settings tended to call for three- or four-part strings and boasted a more flexible texture and structure than the opera sinfonia. During the 1740s and 1750s, wind parts became more common in chamber symphonies: nearly one third of Giovanni Battista Sammartini’s (1700/01–75) sixty-eight symphonies, many from before 1760, add two horns or trumpets to the string choir.4 Although Italian composers wrote for larger ensembles as the century progressed, wind instruments do not appear to have played as significant a role in Italy as they did in Northern Europe, perhaps because the instruments themselves were harder to find.5The imaginative use of the winds by the Italian emigrants Gaetano Brunetti and Luigi Boccherini clearly demonstrates that with the proper resources, Italians could easily hold their own in the area of orchestration.

The impact of Italian symphonies was widely felt, particularly in the first half of the century. In the lands of the Hapsburg monarchy, the impact was both direct – with the presence in Vienna of figures like Bartolomeo Conti (1682–1732), Antonio Caldara (c. 1670–1736) and later Antonio Salieri (1750–1825) – and indirect (with the importation of Sammartini’s symphonies by the Count Harrach and the acquisition of Italian symphonies by the Esterházy family, documented in the Esterházy catalogues from 1740 and 1759–62).6Outside of Vienna, the symphony was composed and cultivated not only in cities like Pressburg and Prague, but also on the private estates of the nobility and in the numerous monasteries and convents. During the first half of the century, a strong fugal tradition threaded through Austrian symphonic composition and the liking for counterpoint never completely died out, although increasingly it was incorporated into a more homophonic style. As early as the 1760s, Austrian composers chose three- and four-movement formats with about the same frequency, but later turned to the four-movement F–S–M/T–F format with a sustained intensity not found in other regions of Europe. Perhaps because of the strong Bohemian wind tradition, works for strings alone were in the minority – even in the early part of the century – and disappeared almost entirely from the 1760s.

Much of the symphonic composition in southern Germany stemmed from its courts – the efforts of Johan Agrell in the free city of Nuremberg notwithstanding – particularly those in Mannheim, Wallerstein, Munich, Mainz, Trier and Cologne. Their musical establishments not only employed local composers, but also absorbed a whole flotilla of Bohemians, including Johann Stamitz (1717–57) and Antonio Rosetti (c. 1750–92), both known for their imaginative and varied use of the wind instruments. Stamitz and his colleagues in Mannheim made effective use of Italian techniques – including string tremolos and crescendos – using winds both for sonic and harmonic reinforcement and for melody. Rosetti had a particular knack for orchestration, often enriching the string texture by dividing the violas and using the winds with delicacy and finesse. Both composers had access to excellent orchestras (at the courts in Mannheim and Wallerstein, respectively), a fact that no doubt helped to stimulate their orchestral imaginations. (As Niccolò Jommelli observed, if you have a good orchestra, you must keep them busy or they will start to give you trouble.) The later Mannheim composers, for example Christian Cannabich (1731–98), Carl Joseph Toeschi (1731–88) and Franz Fränzl (1736–1811), have sometimes been accused of merely dabbling in colourful orchestral effects, but such comments belie the importance of such effects. In fact, particularly with composers like Rosetti, the skilful use of the orchestra to delineate structural function and create tension often goes hand in hand with the simple delight in the play of sonorities.

In northern Germany, the courts and aristocratic patrons sponsored most symphonic composition, although free cities like Hamburg and Leipzig certainly contributed to publication and performance. The Italian opera sinfonia had its effect here as well, but the north-German repertoire, particularly in the first two thirds of the century, showed great diversity in terms of movement structure. In the 1730s and 1740s Johann Gottlob Harrer (1703–55) composed a number of three-movement quasi-programmatic symphonies (some with large wind sections) intended for specific occasions, weaving hunting calls and well-known dance tunes into a mostly homophonic compositional fabric. At the court of Hessen-Darmstadt, Johann Christoph Graupner (1683–1760) and Johann Samuel Endler (1694–1762) showed a preference for symphonies with four or more movements (such large-scale works make up nearly half of Graupner’s 113 symphonies), often with very large ensembles sometimes requiring three trumpets.7 Much of the symphonic activity here appears to have taken place in the first part of the century, with the rate of production dropping sharply after around 1770.

France and Britain had more in common with each other than with the rest of Europe in terms of the cultivation of the symphony. For both, the centre of symphony composition, performance and publication was in their capital cities, though their smaller cities could also boast of musical societies that required symphonies for concerts. In the first two thirds of the century, the sheer number of music publishers in Paris and London completely dwarfed that of all competing cities except, perhaps, for Amsterdam. Paris and London also had a flourishing concert life – both public and private – and eagerly welcomed musical immigrants into their midst. Native composers like Simon Le Duc (1742–77) and the French-speaking immigrant from the Netherlands François-Joseph Gossec (1734–1829) grafted the metric patterns of the French language onto the Italian opera sinfonia style to create symphonic ‘Frenchness’. In the later part of the century, French composers showed a definite preference for the grand and brilliant, particularly with regard to orchestration.8 British taste favoured tuneful, diatonic melodies with lively dance-like rhythms,9 but audiences were also not unmindful of the charms of well-placed counterpoint, preferences that help to explain the popularity of the immigrant J. C. Bach (1735–82) and the adulation that greeted the symphonies of Joseph Haydn.

Areas on the geographical periphery of Europe and those on other continents participated in both the composition and the cultivation of symphonies, though the latter was more frequent than the former. Even if immigrant composers dominated the compositional scene (as did Luigi Boccherini and Gaetano Brunetti in Spain), native-born talents also participated (as with the group of Catelonian composers active around Barcelona after about 1770).10 Lands with music-loving monarchs and established musical institutions, such as Sweden, produced their own local symphony composers even early in the century – for example Johan Helmich Roman (1694–1758) and Johan Agrell – but other places, particularly in the colonial world, did so only towards the century’s close. Immigrant composers completely dominated the musical world of the North-American colonies and the young United States; in South America, the only known symphony by a native-born Brazilian, for example, was written by José Maurício Nunes Garcia (1767–1830) in 1790.11

Symphonic style and form

Any attempt to describe general (as opposed to composer-specific) patterns and trends in eighteenth-century symphonic composition is in some ways a foolhardy undertaking, given the number of works involved and the fact that so many of them have never been studied. What follows can thus not be considered definitive, but is offered as a possible narrative framework for understanding and interpreting the symphonic data that we do have. Briefly stated, the first half of the century witnessed a variety of approaches – on every level of composition – to works labelled ‘symphony’. Although a few patterns can be identified, particularly locally, the differences in everything from number of movements to texture to formal procedures were considerable. By the end of the 1750s, recognisable patterns and conventions common across all the regions of composition had begun to coalesce, giving the genre a more definite shape. These conventions proved advantageous both to composers and listeners; the best composers were those who could exploit them by playing on the expectations they created. Whereas we have tended to view conventional patterns as straight-jackets for the imagination (a sign of our continuing attachment to nineteenth-century aesthetic values), for eighteenth-century composers they appear to have functioned as a stimulus, providing a basic framework upon which they could construct endless delightful and subtle variations.

Early eighteenth-century approaches

From the beginning, most composers chose the three-movement, F–S–F format commonly found in the Italian opera sinfonia for the overwhelming majority of their works, although one- and two-movement works remained a strong second choice. (It should be noted that many of the latter had two-tempo movements, so that they could also be heard as having three or four connected movements.) Four-movement symphonies were less common before the 1750s and can be found in a variety of patterns (not just F–S–M/T–F), as seen in the sampling given in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2 Examples of four-movement plans before 1760

North-German composers, as indicated above, had a particular fondness for works in four or more movements, sometimes with programmatic titles. Graupner’s Symphony in E flat (Nagel 64 from c. 1747–50) features five quick movements: Vivace, Poco Allegro, Allegro, Poco Allegro, Tempo di Gavotte. Endler’s Symphony in E flat (E♭4 from 1757) has both dance and programmatic components: Allegro molto; Menuet I and II, Marche, Contentement, Bourrée I and II, Le bon vivant I and II. For interior slow movements, composers seem to have preferred the tonic or relative minor – a choice that maintained tonal unity and was potentially less jarring to the sensibilities when the movements were very brief – but occasionally chose the subdominant or dominant.

During this period, strings in an a 3 (two violins and basso) or a 4 (two violins, viola and basso) configuration formed the core of performance forces, although a 3 works became rarer by the 1740s. When available, wind instruments (most commonly horns, oboes or trumpets) could join this core string group, particularly in Italian opera sinfonie and for ceremonial occasions at court or in church. For example, the Symphony in C by Georg Reutter the Younger (1708–72) calls for a 4 strings, organ and two brass choirs, each with two clarini, two trombe and timpani.12 Endler’s Symphony in D (D4), written for a New Year’s Day celebration in 1750, requires a 3 strings, oboe, two horns, three clarini and timpani. The use of winds in more ordinary circumstances increased gradually throughout the period, although instrumentation often remained flexible: the title page of Jean-Férry Rebel’s 1737 Symphony, Les eléments, announces that ‘This symphony is engraved in such a way that it can be played in concert by two violins, two flutes, and one bass’, adding that a harpsichord could also play it alone. Moreover, the score itself indicates a number of places where other instruments – specifically two violas, basso continuo, piccolos (petites flutes), oboes, horns and bassoons – could be added.13 Although Rebel’s work is unusual in the extent of its suggested alternatives, flexibility with regard to wind parts was widespread. Published works often had ad libitum wind parts to make them more marketable and – conversely – trumpet or horn parts could be added to make a work more festive or to cater for a patron’s wishes.14

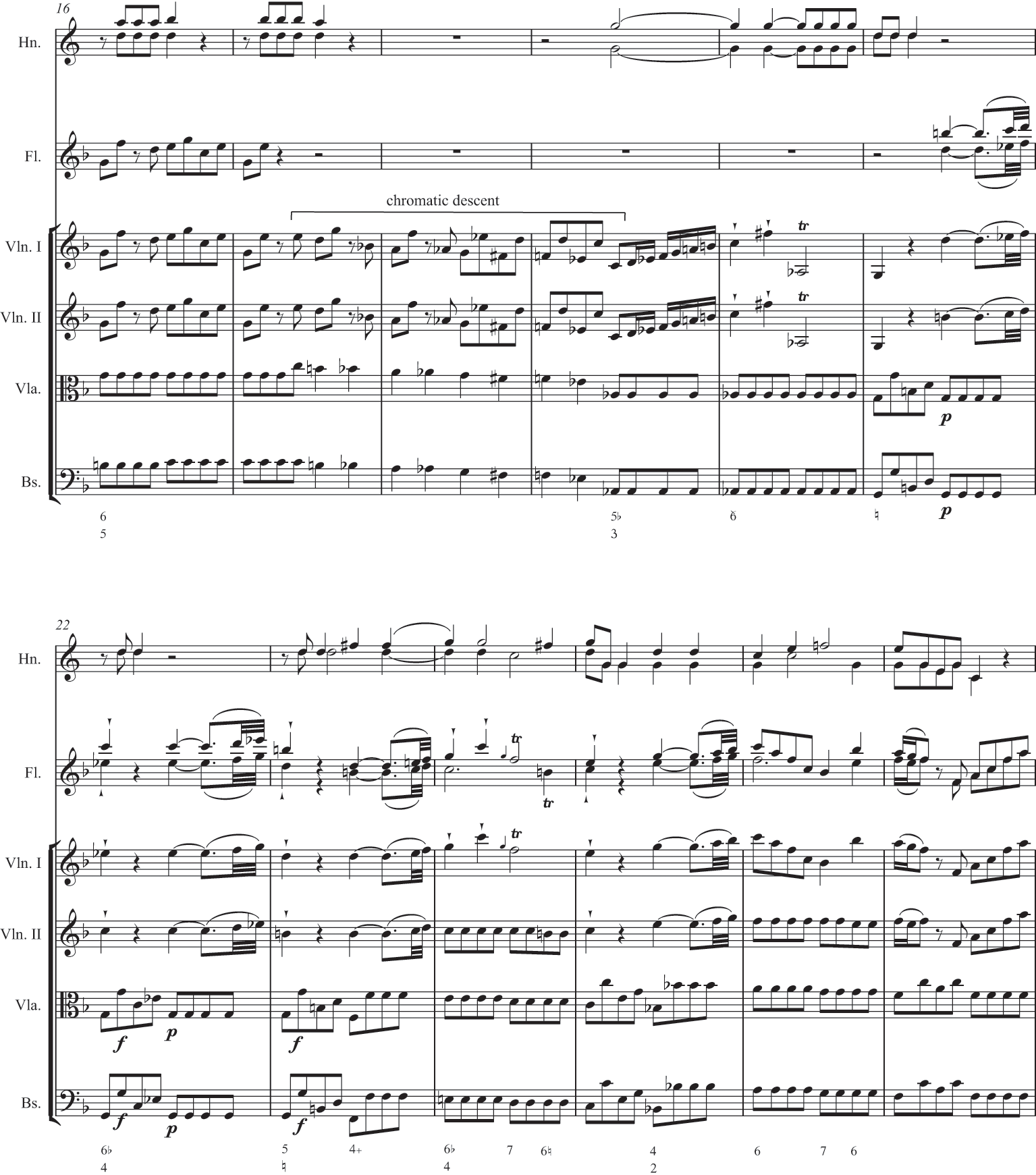

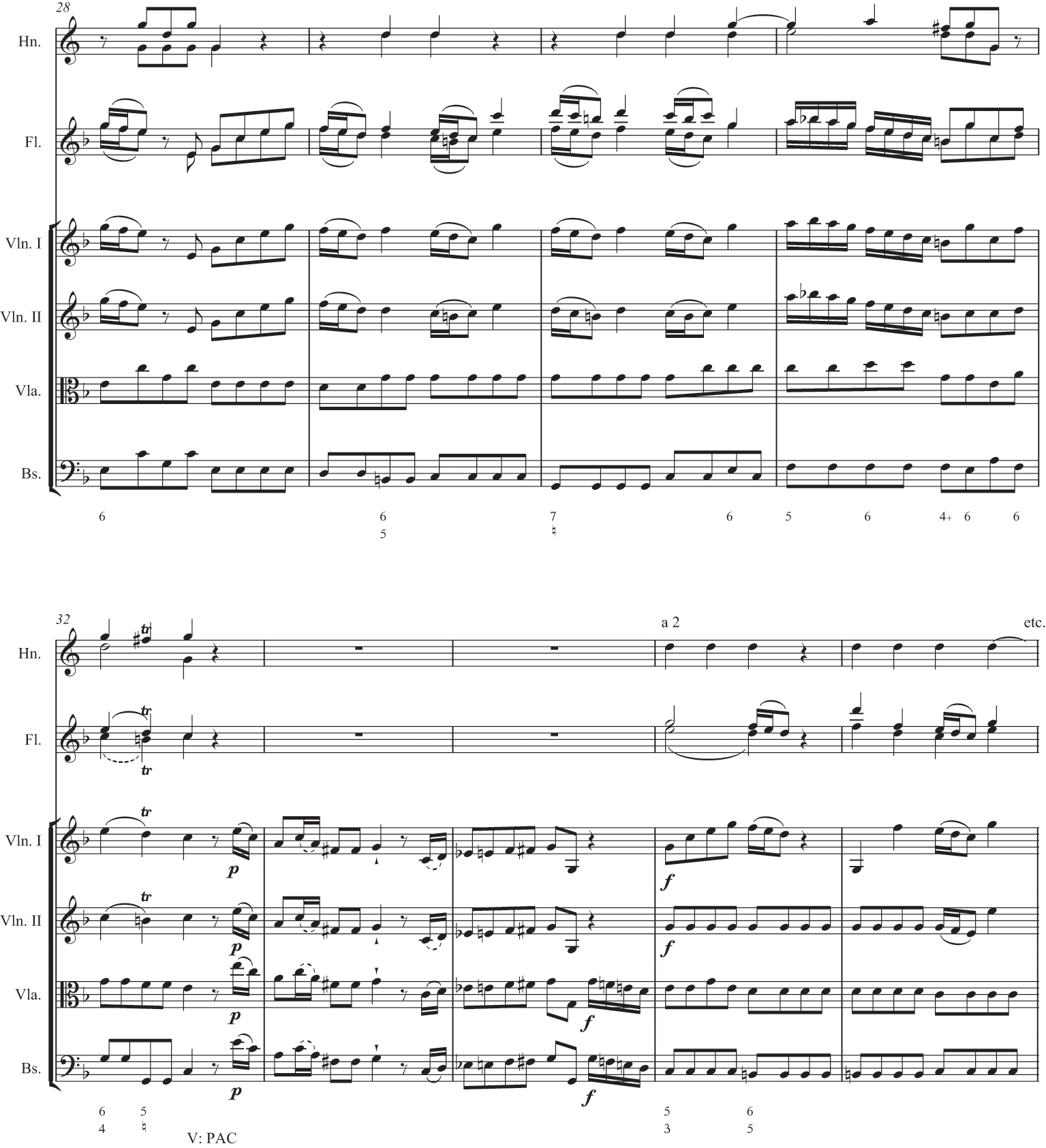

Although wind instruments in this repertoire tend to play either colla parte with the strings or to reinforce the harmony, we should not discount the effect that they had on the listener’s sonic experience. Moreover, composers often highlighted the wind instruments or used them in a more subtle interplay. In Johann David Heinichen’s (1683–1729) Symphony in D (written after 1717), pairs of flutes and oboes play colla parte with the strings, but the two horns have occasional solos. Agrell’s woodwinds usually play colla parte with the strings, but in his Symphony in C major (from the early 1740s), he makes sophisticated use of their penetrating sonority, with the oboes reinforcing the syncopated harmonic shifts made by the strings and the horns entering in alternation with punctuation that drives to the downbeat (Example 3.1). Rightly known for his imaginative orchestral effects, Johann Stamitz frequently used winds as solo instruments in secondary themes, temporarily relegating the normally dominant strings to an accompaniment role. During this period, wind instruments often dropped out for middle slow movements, thus creating a sonic contrast with the surrounding tutti fast ones, although sometimes, as in Giovanni Battista Lampugnani’s (c. 1708–c. 1788) Symphony in D (D6, c. 1750) and some of Graupner’s early works, the horns continue the harmonic supporting role evident in the outer movements.

Example 3.1 Johan Agrell, Symphony in C major, I, bars 15–23.

Early symphonies exploited a wide variety of textures, from strictly fugal to essentially contrapuntal to purely homophonic. The preference for fugues in instrumental composition has been associated with Vienna; however the technique can be found across the continent. The Swedish composer Ferdinand Zellbell, Jr (1719–80) opened his D minor Symphony with a first movement slow introduction leading to a fugue followed by a sarabande and gigue, and several composers in England – Francesco Barsanti (1690–1772), Thomas Arne (1710–88), Maurice Green (1696–1755) – incorporated fugal movements in their symphonies from the 1740s and 1750s. (Interestingly, Padre Giovanni Battista Martini (1706–84), famous all over Europe for his counterpoint treatise, did not include any fugal movements in his twenty-four symphonies.) Although arrangements like Zellbell’s follow the pattern of the French overture and suite, with slow dotted openings leading to fugues followed by dance movements, not all fugal movements fall into that category: Wenzel Birck’s (1718–63) Sinfonia No. 9 has a 107-bar Presto before its fugue,15and most of Franz Xaver Richter’s (1709–89) symphonic fugues appear in finales.16 Even in the early part of the century, fugues and fugal textures appear in only a tiny fraction of all symphony movements; I have considered them at some length here because their persistent presence in the repertoire helps to explain the continuing importance of counterpoint in later eighteenth-century works.

The predominant symphonic texture was of course homophony, both in the unison/massed sound and the melody-with-accompaniment varieties. Throughout the first half of the century, however, composers consistently mixed a soupçon of counterpoint into their symphonies, often to articulate structural functions. Antonio Brioschi (fl. c. 1725–c. 1750) commonly turned contrapuntal in his development sections, while Sammartini often used contrapuntal transitions that contrast with the unison or homophonic primary and closing sections. By way of contrast, Agrell often distinguished his secondary themes by introducing counterpoint, along with reduced orchestration and dynamics. These examples show that fugal and contrapuntal techniques were quickly absorbed into the newer formal procedures that began to dot the symphonic landscape.

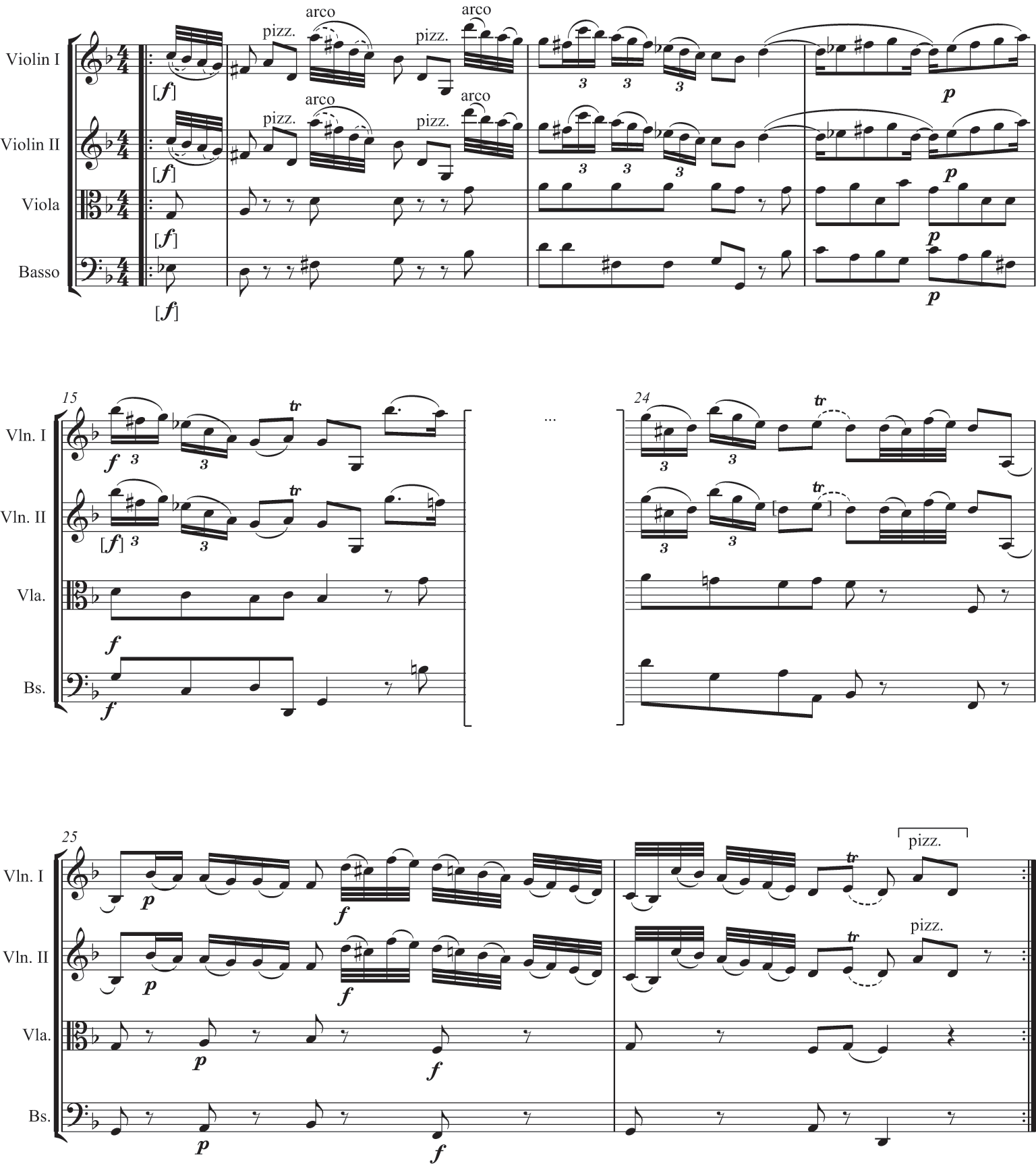

In terms of formal structure, most early first movements fell somewhere along the continuum of binary to sonata forms (mostly the latter), but some are ritornello-based and others blend aspects of ritornello and sonata construction. Slow movements and other fast movements rarely made use of ritornello techniques and mostly fall towards the binary end of the continuum. Conventions for delineating the sections of sonata movements were just beginning to emerge, but the first three basic sonata types described by James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy for the later eighteenth century can easily be identified in this repertoire as well.17 In general, composers of this period were establishing the rules of the game (à la Leonard Meyer) with great vitality and spirit, exploring possibilities for generating tension and excitement (tremolos, crescendos, rising lines, etc.) and for expressivity.18 Often, the expressive centre of the work was in the (frequently) minor-mode slow movement, which habitually featured nuanced dynamic contrast, sighing appoggiaturas and cantabile melodies. Georg Benda (1722–95) makes the most of the sonic possibilities of the strings in the slow movement his Sinfonia I in F major by juxtaposing pizzicato and arco motives, ending with a delightfully quizzical pizzicato weak-beat afterthought (Example 3.2).19

Example 3.2 Georg Benda, Sinfonia No. 1 in F major, I, bars 12–15; 24–6.

Expressive choices, however, were not limited to the slow movement. Opening major-mode movements often featured diversions to the minor dominant in S (the subordinate theme), a tactic particularly popular in Italian opera sinfonie of the 1730s as seen in Leonardo Leo’s Amor vuol sofferenza from 1736 (Example 3.3a and b). Similar techniques are employed by such diverse composers as Agrell, Harrer, Leopold Mozart (1719–87) and Georg Wagenseil (1715–77). The long primary section of Sammartini’s Symphony No. 10 in F major even encompasses a plaintive contrasting section in the tonic minor. Development sections frequently traverse minor-mode areas, often with a strong cadence to the relative minor just before the recapitulation. In many cases, this expressivity relies on local-level contrast, nowhere more strongly than in the symphonies of C. P. E. Bach (1714–88). In his Symphony in F of 1755 (Wq 175) rests, chromatic excursions and dynamic contrasts enhanced by changes of orchestration all combine to create local-level drama and structural-level tension. The piano trills in bar 7 give way in the next measure to a minor-mode variant of bar 6, which is followed by a forte outburst on V7/V to begin the transition. Its path to V, however, is continually derailed by further chromatic diversions and piano interpolations, delaying the cadence in the dominant until bar 32 (Example 3.4).

Example 3.3a Leonardo Leo, Overture to Amor vuol sofferenza, I, bars 1–5.

Example 3.3b Leonardo Leo, Overture to Amor vuol sofferenza, I, bars 12–17.

Example 3.4 C. P. E. Bach, Symphony in F major, Wq 175, I, bars 1–36.

Bach’s symphonies, like many others from the first part of the century, derive their energy from such local-level contrasts, together with lively and engaging motives, a consistent quaver pulse and a forward trajectory that minimises sectional and functional delineation. Such techniques, particularly when used skilfully, work very well in shorter movements; for more extended compositions, other organisational strategies needed to be devised. Many of the formal conventions we associate with sonata form emerged as composers began to incorporate these local contrasts into a larger compositional trajectory in which the various sections of the movement assumed particular functional responsibilities. The trajectory was created in large part by the creation of expectations, which could then be fulfilled, deflected, or even subverted. This approach became the defining feature of late eighteenth-century symphonic style.

Late eighteenth-century conventions

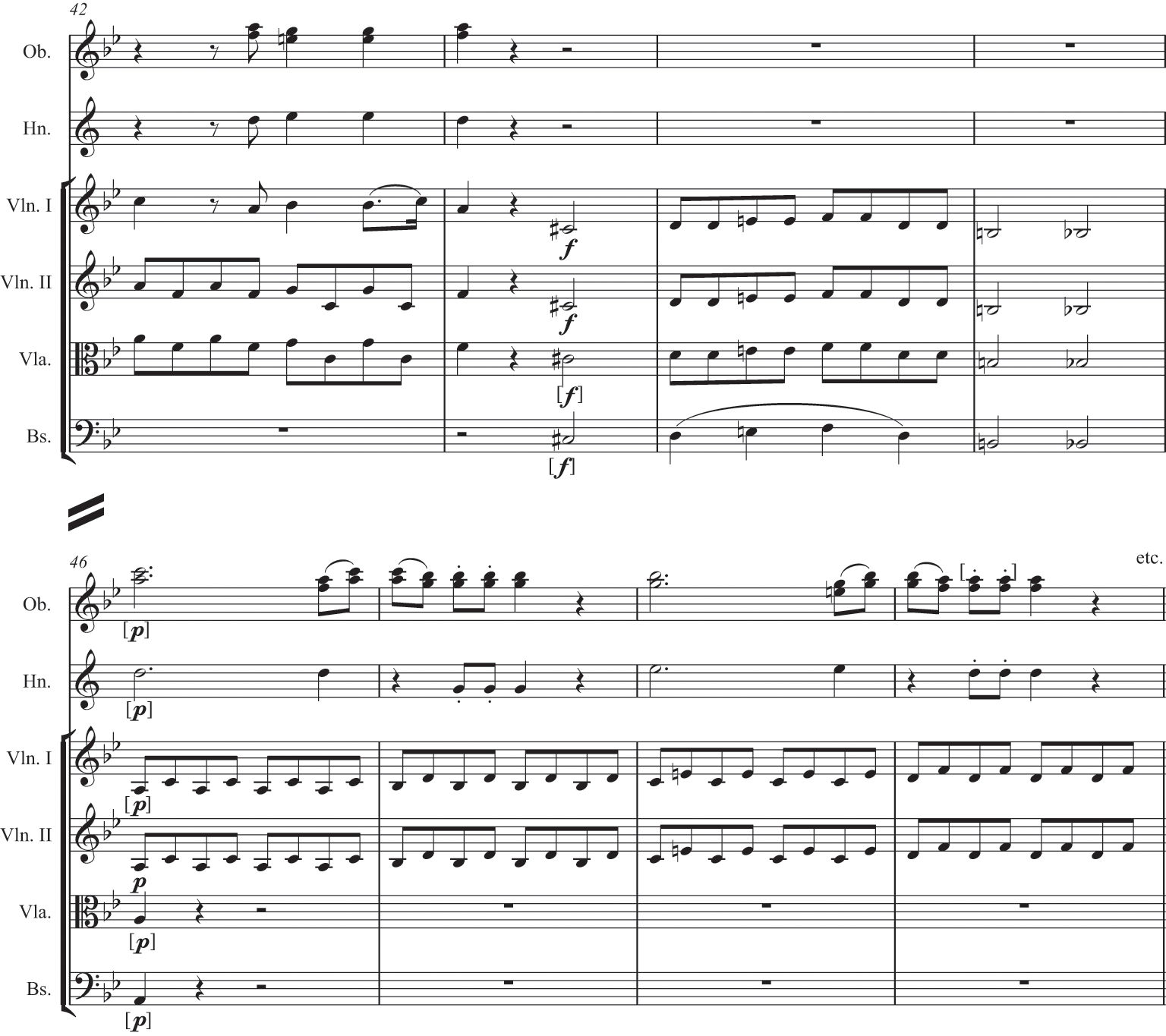

By the 1760s, conventional practices in all elements of symphonic composition had coalesced into patterns discernible throughout the European continent. The three-movement F–S–F pattern continued as the most common movement format, with the four-movement scheme (mostly, though not always, F–S–M/T–F) the strong second choice. Only at the very end of the century did the F–S–M/T–F format start to dominate, and even then some composers who had flirted with the four-movement pattern early in their careers chose the three-movement variety in their later works, among them Cannabich, Toeschi and Ignaz Pleyel (1757–1831). Rather than seeing their choice as a ‘reversion’ to an outdated practice (as has generally been the case), we might more profitably ask what advantages or disadvantages the two options might have had. Composers like Joseph Haydn took advantage of the minuet’s compact and absolutely predictable form to stretch and play with musical parameters like rhythm and texture. For others, the inclusion of the minuet might simply have expanded the symphony beyond a usable length, especially given the increasing length and complexity of the other movements (something that probably explains the nearly complete disappearance of symphonies in more than four movements). One- and two-movement symphonies still maintained a presence in the repertoire in France, the Austrian lands and especially in Italy, where they continued to be of importance in church settings. For example, twenty-four of the Franciscan priest Stanislao Mattei’s (1750–1825) twenty-seven symphonies are single-movement works intended for church performances in Bologna.20

In the area of orchestration, the a 8 configuration (a 4 strings plus two oboes and two horns) emerged as the overwhelming favourite. This particular convention may well have been driven by market forces: music publishers and dealers clearly preferred symphonies with instrumental requirements that most ensembles could cover. Although strings-only symphonies continued to appear well into the second half of the century, by the 1790s the theorist Heinrich Christoph Koch could state that audiences generally expected to hear winds in symphonies.21 Works requiring large wind ensembles still tended to come from courts with substantial orchestras (e.g. Mannheim and Wallerstein), and some evidence suggests that such large-scale pieces were much less likely to see publication. The Cannabich symphonies published by Götz in the 1770s call for the standard a 8 orchestra, but those written just for the Mannheim court often add two clarinets, and the unpublished No. 44 is for a double orchestra.22 Nonetheless, a number of Cannabich’s unpublished symphonies require only the a 8 ensemble, perhaps because of its practicality or because it was the most effective choice for relatively small spaces. Separate parts for flutes, bassoons and cellos became increasingly common (clarinet parts remained rare), and trumpets and timpani still seem to have been reserved for works intended to convey ceremony and splendour. In fact, although instrumental requirements grew steadily, a ‘full’ wind complement of pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns and trumpets did not become a standard choice until the early nineteenth century.

The variety of formal approaches found in the early part of the century had by now coalesced into the sonata types described by Hepokoski and Darcy, particularly for opening fast movements. Sonata forms also predominate in slow movements and finales, though rondos or other part forms, and occasionally simple binaries, can be found as well. Although the Type 3 sonata (having a recapitulation beginning with P in the tonic) seems to have been increasingly preferred, the Type 2 (in which the return to the tonic coincides with post-P materials) was also very common. It would be anachronistic to assume (as has often been done) that the Type 2 was ‘more primitive’ than the ‘full’ Type 3, since a single symphony could easily have both, and neither individually nor collectively did composers ‘progress’ from Type 2s to Type 3s. One suspects, in fact, that the choice of a Type 2 might have been practical as well as aesthetic, keeping the performance time manageable as movement length increased.

Sonata form proved to be the ideal solution to the organisational challenge of longer movements, providing both the framework and flexibility for creating works that were both immediately understandable as types yet distinctly different as pieces. In the exposition, for example, the two main patterns (two-part and continuous) described by Hepokoski and Darcy are ubiquitous. Many composers, like J. C. Bach, preferred the two-part approach with its clearly delineated secondary theme articulated by a strong medial caesura, dynamic and textural changes (often to piano and reduced orchestra) and sometimes contrasting material. This pattern (which incorporated the local contrasts described above into a larger structure) provided aural guidance to listeners but nonetheless allowed for the small yet piquant variations so essential to the style. The C minor slow movement of Bach’s Op. 6, No. 5 reaches a v:HC medial caesura in bar 14, but instead of a second theme in v, we hear one in III.23 The frequency with which transition material led to a medial caesura made it possible for composers (particularly Joseph Haydn) to subvert this expected pattern with a continuous exposition that avoided a secondary theme entirely. These continuous expositions typically have a very different sound and trajectory from the continuity described above in the C. P. E. Bach symphony because their transitions, which continue past the temporal point where a secondary theme would normally have appeared, have a relentlessness that creates an ever greater need for the tonal closure the exposition requires. Here too, the techniques for creating this tension (crescendos, addition of instruments, motivic shortening, sequences, deceptive cadences, etc.) could be combined in an infinite variety of ways, so that each work could provide a new listening experience. All parts of the sonata structure could be manipulated in this fashion: ‘development’ sections could present new material; ‘recapitulations’ could undertake further development. Procedures found in Gossec’s recapitulations, for example, range from more-or-less exact repetitions to those that reorder the exposition themes, or incorporate new material that had been introduced in the development, or involve considerable recomposition.24 In creating these variations on the sonata theme, individual composers differed widely both in degree and techniques, but all except the worst usually managed to devise an unexpected twist or an artfully different sound to delight both the ear and the mind.

Orchestration often played a significant role in this manipulation of conventions and in the overall success of the work. Many first-movement primary themes are noisy, exciting, triadic affairs played by the full ensemble, but the first movement of Cannabich’s Symphony No. 57 in E flat opens with violins and clarinets sustaining an E♭ over the moving bass line; by bar 7, the clarinet has taken over the melody, while the violins and basso line punctuate with turn figures. At any point in the movement, this configuration would be arresting, but it is particularly so for an opening. Like Cannabich, Rosetti had a knack for configuring the orchestra in unexpected ways and using the winds at exactly the right moment. His D major Symphony from c. 1788 opens with a single noise-killing chord before the violas, cellos, basses and bassoons enter with the theme, punctuated by the violins and upper winds. The third movements of Brunetti’s four-movement symphonies – all dances but not all minuets – use a wind quintet for the A section and strings for the second, an inversion of the often-used procedure of featuring winds in the B section (or trio) of the minuet. In the Symphony No. 9 in D, the Allegro Minuetto first section, scored for two oboes, two horns and bassoon, leads to a B section for strings and timpani.

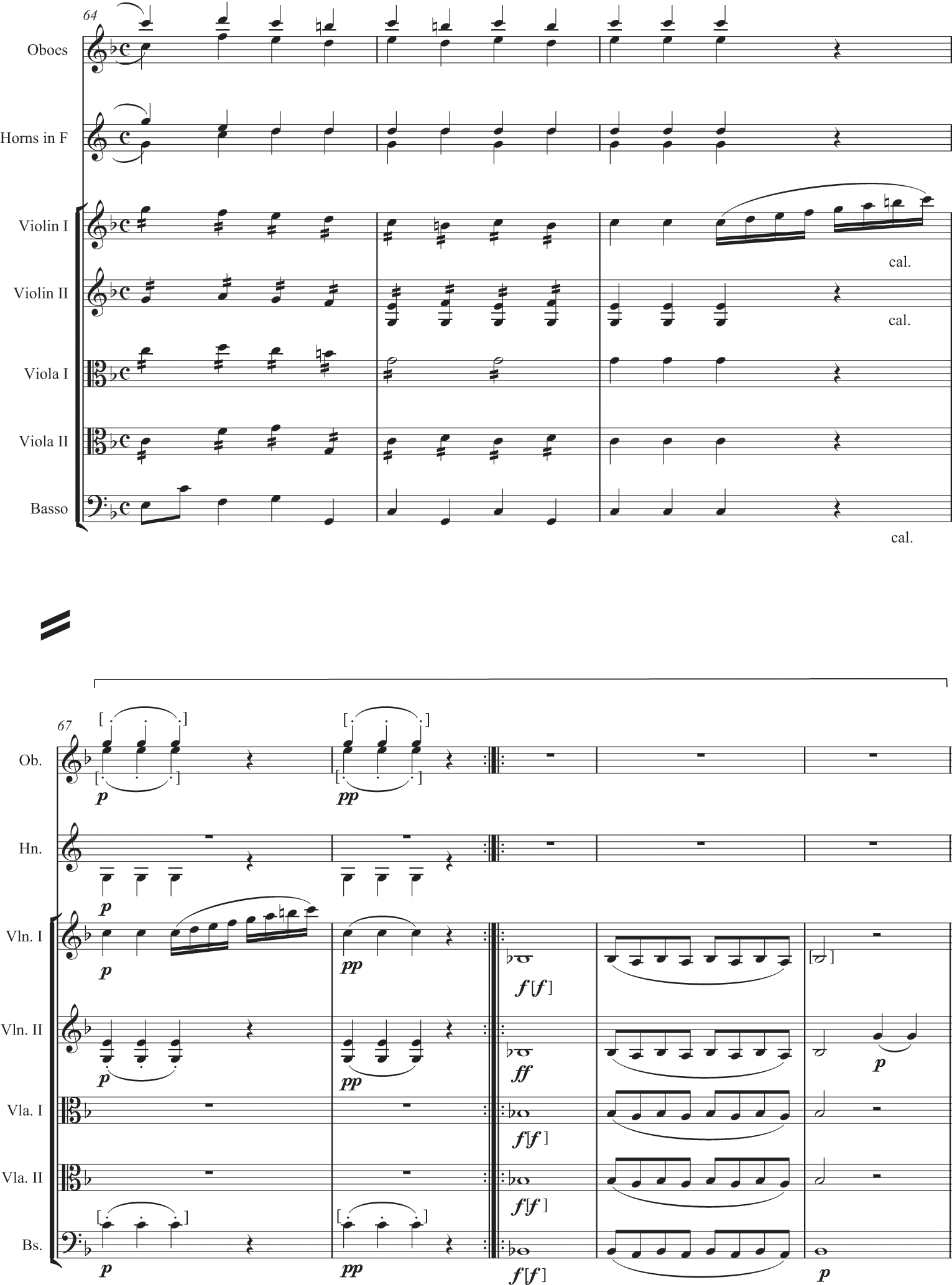

In the late eighteenth century, texture was closely related to orchestration and wind usage, because subtle use of instrumentation could create variety in an essentially homophonic texture. Purely fugal movements are relatively rare and tend to call attention to themselves. Luigi Borghi’s rondo Finale to his Op. 6, No. 6, published in 1787, dissolves into a fugue, as if to defy conventional expectations.25Joseph Martin Kraus’s 1789 one-movement Sinfonia per la chiesa, written for the blessing of the parliament in Sweden, opens with a slow introduction followed by a fugue, albeit one in two sections (the first repeated!), ending with a substantial section presenting the fugue theme homophonically. More commonly, composers wove counterpoint and a variety of textures into the fabric of formal procedures, using the differences and shadings to delineate formal areas (just as earlier composers had done), but also to complicate them. In the first movement of his F major Symphony (Mennicke 97 from before 1762), Johann Gottlieb Graun (1702/3–71) introduces a brief contrapuntal interchange just at the point when a secondary theme seems to be emerging (bar 30) to convert from a two-part to a continuous exposition (Example 3.5). The transition in the first movement of Cannabich’s Symphony No. 73 in C moves noisily and homophonically towards V as expected, but at the moment when V/V arrives and S should appear, he switches to the minor mode and reduces the texture to piano contrapuntal lines, in effect derailing the transitional train and stretching the tension over another 20 bars (Example 3.6). The contrapuntal minuets that turn up in the symphonies of Joseph Haydn, W. A. Mozart, Wenzel Pichl (1741–1805), Gossec and Brunetti count as sly tweaks to convention in their conflation of the most learned of musical styles with the most courtly and galant of dances.

Example 3.5 Johann Gottlieb Graun, Symphony in F major (Mennicke 97), I, bars 24–42.

Example 3.6 Christian Cannabich, Symphony No. 73 in C major, I, bars 31–66.

The increasing length of individual movements and the variety of textures and styles they incorporated meant that composers needed to develop new strategies for creating unity even beyond the trajectory provided by sonata form. Perhaps the most common technique was the derivation of transition and closing materials from the opening primary material, a practice so ubiquitous it is found even in melody-rich compositions like those of W. A. Mozart. Composers as disparate as Karl d’Ordonez (1734–86) and Gossec were fond of constructing intricate motivic connections among seemingly contrasting themes. Although Pichl’s slow introduction to the first movement of his Op. 1, No. 5 has no motivic connection to the material that begins in bar 67, the slow, regular quaver motion, the restricted range, the legato markings and piano dynamic level call up the aural memory from earlier in an even more compelling way than a motivic recurrence could have done (Example 3.7a and b). Sometimes such techniques connected movements as well. Nearly all of Michael Haydn’s (1737–1806) late symphonies share motives among all the movements, a procedure also found in the works of Pichl and Adalbert Gyrowetz (1763–1850) among others. Although sometimes the shared motives can seem too generic to be convincing as cyclic links, when used in combination with parallels of texture and articulation, they signal a clear connective intention on the part of the composer.26Beginning as early as 1771, Boccherini explored even more extreme manifestations of unity, sometimes reprising large sections of earlier movements in the later ones. The Finale of his Symphony No. 21 (G. 496) comprises a complete repetition of the first movement’s recapitulation.27These instances should put the often cited cyclic aspects of some of Haydn’s and Beethoven’s symphonies in perspective. Such techniques were part of a new set of symphonic conventions just beginning to emerge at the end of the century.

Example 3.7a Wenzel Pichl, Symphony in F major, Op. 1/5, I, bars 1–8.

Example 3.7b Wenzel Pichl, Symphony in F major, Op. 1/5, I, bars 67–79.

Expressive choices during the later part of the century also broadened and deepened the paths laid out by earlier composers. In addition to the minor mode, composers increasingly made use of distantly related tonalities, particularly third-related or Neapolitan keys, both for brief chromatic digressions and for longer excursions away from the tonic. For example, the C major Symphony (from the 1770s or 1780s) of the Norwegian composer Johan Heinrich Berlin (1741–1807) reaches B major as the point of furthest remove in the development section of the first movement. Often these keys were introduced as a way of subverting convention, an act which itself became an expressive choice. If you expect the development section to begin with some form of P in V, then it will come as quite a shock when a three-bar unison fortissimo string semibreve on ♭VII/V follows directly on the close of the exposition. This technique can be found in the first movement of one of Rosetti’s most popular works, the Symphony in F major (F1), from c. 1776 (Example 3.8).28Of course, Rosetti had a fondness for this type of disruption (it is also found in the first movement of his B♭1), and once the listener begins to expect disruption, then its expressive value can begin to fade. But for eighteenth-century symphony composers, the trick to continuing effectiveness, whether in the use or the disruption of convention, was not in that you did it but in how. For example, Pasquale Anfossi’s (1727–97) Sinfonia in B flat (B♭5) from 1776 has an ingenious disruption of expectations in the middle of the first movement’s secondary theme. S begins quite properly in V (F major) in bar 25 with a two-bar motive repeated exactly to create a four-bar phrase ending with a V:IAC. After a crotchet rest, however, comes a jarring unison forte C♯ and a two-bar diversion to D minor that loses its punch and returns to a relentlessly regular eight-bar consequent in F major (Example 3.9).

Example 3.8 Antonio Rosetti, Symphony in F major (F1), I, bars 64–71.

Example 3.9 Pasquale Anfossi, Sinfonia in B flat (B♭5), I, bars 25–49.

The piquancy of the brief moment, however, disappears when the whole section is repeated exactly, thus regularising the disruption and robbing it of its power. On the other hand, in the first movement of J. C. Bach’s Symphony in E flat, Op. 6, No. 5, the sudden appearance of D♭ unison fortissimo tremolos at the beginning of the development after the conclusion of the exposition in B-flat major gains in effectiveness because the movement is a non-repeating sonata form. Thus, although the subsequent music absorbs it into a relatively normal progression, its initially shocking quality remains, undiminished by repetition.

Conclusion

In 1713, Johann Mattheson defined a symphony as an instrumental piece without restrictions, and though he went on to describe a typical Italian opera sinfonia as having a brilliant opening movement and a dance-like finale, he made it clear that composers were entirely free to follow their own inspiration as long as the music did not thereby become chaotic.29 As indicated above, composers did just that in the early decades of the century; for them the possibilities were – if not limitless – then excitingly vast, even if tidy modern historians might see the situation as chaotic. The extensive circulation of manuscript parts throughout Europe, however, meant that most composers were not working in isolation; as a result, by the middle of the century the symphony had begun to coalesce into a recognisable genre, with conventions governing everything from the number of movements to orchestration to formal procedures. Yet even if later eighteenth-century composers perhaps had less freedom to do what they wanted in a symphony, they gained the power that such conventions provide: a basic structure that did not have to be invented anew with each composition. With this structure ensuring intelligibility, composers could then concentrate on subtlety and nuance, delighting their listeners with small changes and surprises in each new piece. For it should be emphasised that the symphony in the eighteenth century was meant to be comprehended on the very first listening.30 That was its true function, whether in the church, theatre or chamber, and that was what made it so successful. It requires a certain retraining of our post-Mahlerian ears to appreciate fully the artistry and feel the excitement that so enchanted eighteenth-century audiences, but once you’ve managed that, you may find yourself thinking, as I have over the past few years: ‘so many symphonies, so little time’.

Notes

1 A sampling can be found in and , eds., The Symphony, 1720–1840: A Comprehensive Collection of Scores in Sixty Volumes, 60 vols. (New York, 1979–86). This collection, which is organised by geographical region, includes full scores of previously unpublished symphonies, as well as brief biographical and analytical essays on the composers included.

2 During the second half of the century, particularly in the English-speaking world, the terms ‘overture’ and ‘symphony’ were virtually interchangeable. In continental usage, the word overture tended to be reserved for works that follow the movement pattern we associate with the French overture, but it was not used in the modern sense to refer to the instrumental work preceding an opera.

3 I have also, for the moment, sidestepped the issue of redefining what constitutes historical significance, which until now has mostly been determined by a composer’s ‘innovations’ (e.g. the first four-movement symphony) or his relationship to Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. I address this question in the final chapter of Mary Sue Morrow and Bathia Churgin, eds., The Symphonic Repertoire, vol. I: The Eighteenth-Century Symphony, currently in preparation, to be published by Indiana University Press.

4 See and , Thematic Catalogue of the Works of Giovanni Battista Sammartini (Cambridge, Mass., 1976).

5 Although Italy had a long tradition of brass and violin manufacturing, it lagged far behind Northern Europe in the production of other wind instruments. See and , The Birth of the Orchestra: History of an Institution, 1650–1815 (New York and Oxford, 2004), 172–3.

6 Bathia Churgin, ‘Giovanni Battista Sammartini’, in New Grove Online, available at www.oxfordmusiconline.com, accessed 20 November 2008; , Studien zur Esterházyschen Hofmusik von etwa 1620 bis 1790 (Regensburg, 1981), 67. In his biography of Haydn, Giuseppi Carpani asserts that Nicholas Esterházy had a standing order for new music by Sammartini. See The Lives of Haydn and Mozart, trans. , 2nd edn (London, 1818), 107–8.

7 These have sometimes been designated as ‘suite symphonies’. The Italian composer Fortunato Chelleri wrote three of these, but they do not appear to have been common in Italy. See Bathia Churgin, ‘Fortunato Chelleri’, in Brook and Heyman, eds., The Symphony, 1720–1840, vol. A3, xxvii.

8 See Robert Gjerdingen, ‘The Symphony in France’, in Morrow and Churgin, eds., The Eighteenth-Century Symphony, 551–70.

9 See Simon McVeigh, ‘The Symphony in Britain’, in Morrow and Churgin, eds., The Eighteenth-Century Symphony, 629–61.

10 , ‘The Symphony in Catalonia, c. 1760–1808’, in and , eds., Music in Spain during the Eighteenth Century (Cambridge, 1998), 157–71 .

11 Bertil van Boer, ‘The Symphony on the Periphery’, in Morrow and Churgin, eds., The Eighteenth-Century Symphony, 726, citing Cleofe Person de Mattos’s introductory essay for , Aberturas (Rio de Janeiro, 1982), 9–12. The work is a one-movement Sinfonia funebre in E-flat major.

12 Judging from the performance parts preserved in the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, the strong brass presence was supported by a relatively large string ensemble with as many as twelve violins. This symphony can be found under the call number GDMF XIII 8577 and has performance dates in the 1740s and early 1750s.

13 The Symphony, 1720–1840, vol. D1, 1.

14 Either Johann Christoph Graupner or Johann Samuel Endler appears to have added brass parts to the strings-only symphonies of Joseph Camerloher for performance at the court in Darmstadt. See Suzanne Forsberg, ‘Joseph and Placidus von Camerloher’, in Morrow and Churgin, eds., The Eighteenth-Century Symphony, 341.

15 Sinfonia // a 4tro // Violino Primo // Violino Secondo // viola, e Basso // Del Sig. Wenceslao Reimondo Birck, ÖNB MS 3610.

16 Richter has seven fugal finales (three dating from c. 1760 to 1765, the others earlier), one fugue in an opening movement and one in a second, as well as a one-movement adagio-fuga ‘Sinfonia da chiesa’. See Bertil van Boer, ‘Franz Xaver Richter’, in Brook and Heyman, eds., The Symphony, 1729–1840, vol. C14, xxvii–xxxviii. Although an unusually high number for the middle of the century, it is not an overwhelming one considering that he wrote eighty-three symphonies.

17 and , Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata (New York and Oxford:, 2006). Though the various default levels they identify do not – as should be expected – always hold for works before the middle of the century, their system can be adapted to this repertoire quite profitably.

18 See , Style and Music: Theory, History, and Ideology (Chicago, 1989), and ‘Innovation, Choice, and the History of Music’, Critical Inquiry, 3 (1983), 517–44.

19 This symphony, composed between 1750 and 1765, is for a 4 strings and two horns, with the horns tacet in this movement (a typical procedure for the mid century).

20 Rey M. Longyear, ‘Stanislao Mattei’, in Brook and Heyman, eds., The Symphony, 1720–1840, vol. A8, x. Mattei lived from 1750 to 1825, but all his symphonies were written before 1804.

21 , Musikalisches Lexikon (Frankfurt, 1802, repr. Hildesheim, 1964), 1385–8.

22 J. C. Bach and Stanislao Mattei also wrote works for double orchestra.

23 Adena Portowitz, ‘J. C. Bach’, in Morrow and Churgin, eds., The Eighteenth-Century Symphony, 662–83.

24 Judith K. Schwartz, ‘François-Joseph Gossec’, in Morrow and Churgin, eds., The Eighteenth-Century Symphony, 585–626.

25 Simon McVeigh, ‘The Symphony in Britain’, in The Eighteenth-Century Symphony, 432.

26 Richard Agee notes the striking similarity of the second theme groups in Pichl’s Il marte. See his ‘Wenzel Pichl’, in Brook and Heyman, eds., The Symphony, 1720–1840, vol. B7, liii.

28 Sterling Murray, ‘Antonio Rosetti’, in Brook and Heyman, eds., The Symphony, 1720–1840, vol. C6, xxxv. Boyer in Paris published the Symphony in 1779.

29 , Das neu-eröffnete Orchestre (Hamburg, 1713; repr. Laaber, 2004), 171–2.

30 makes this point in his Wordless Rhetoric: Musical Form and the Metaphor of the Oration (Cambridge, Mass., 1991).