7 Harmonies and effects: Haydn and Mozart in parallel

‘Haydn is called by the courtesy of historians, the father of the symphony’, remarked English critic Edward Holmes in 1837, but Mozart is ‘the first inventor of the modern grand symphony’.1 Whether Holmes knew it or not, Haydn’s and Mozart’s symphonies had already been compared for at least fifty years, in spite of fundamental differences in the two composers’ symphonic careers (for instance in the numbers of works, circumstances of composition and venues for premieres). Inevitably, comparisons evolved over time, Mozart initially tending not to fare too well. ‘If we pause only to consider [Mozart’s] symphonies’, wrote the Teutschlands Annalen des Jahres 1794, ‘for all their fire, for all their pomp and brilliance they yet lack that sense of unity, that clarity and directness of presentation, which we rightly admire in Jos. Haydn’s symphonies.’2 More pointedly, in the London-based Morning Chronicle (1789): ‘The Overture [that is, symphony] by Mozart, owed its success rather to the excellence of the band, than the merit of the composition. Sterne was an original writer; – Haydn is an original musician. It may be said of the imitators of the latter, as of the former, they catch a few oddities, as dashes – sudden pauses – and occasional prolixity, but scarcely a particle of feeling or sentiment.’3Later, with the Haydn–Mozart–Beethoven triumvirate established in critical discourse, Haydn the symphonist began to suffer slightly, perceived as a kind of warm-up act – albeit an extremely good one – for his successors. Foreshadowing a hierarchy to which Holmes evidently subscribed, the Quarterly Musical Magazine and Review (1826) explained that Haydn gave the symphony ‘form and substance, and ordained the laws by which it should move, adorning it at the same by fine taste, perspicuity of design, and beautiful melody’, but that Mozart ‘added to the fine creations by richness, warmth and variety’ and Beethoven ‘endowed it with sublimity of description and power’.4 Irrespective of orientation, comparisons exemplify our need – apparently infusing musicological DNA – to bring Haydn and Mozart under the same critical lens.

Eagerness to generate links between Haydn and Mozart in order to validate the superiority of their music over that of their contemporaries and immediate predecessors was already apparent at the turn of the nineteenth century. Friedrich Rochlitz, in factually tainted anecdotes about Mozart published in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung (1798–1801), embroidered stories about Haydn defending Don Giovanni against detractors and about Mozart passionately advocating Haydn’s symphonies, explaining that ‘great men [have] always given great men their due’; Johann Karl Friedrich Triest, in the same journal (1801), set up Haydn as the greatest instrumental composer and Mozart as the greatest musical dramatist in the ‘third period’ of the eighteenth century, a period he even subtitled ‘from J. Haydn and W. A. Mozart to the End of the Last Century’; Thomas Holcroft reported, as routine, debates about the relative statuses of these ‘men of uncommon genius’ (1798); and Franz Xaver Niemetschek, one of Mozart’s earliest biographers (1798), showcased Haydn’s and Mozart’s mutual admiration, dedicating his volume on ‘immortal Mozart’ ‘with deepest homage to Joseph Haydn . . . father of the noble art of music and favourite of the Muses’.5But one of the earliest – perhaps the very earliest – protracted comparisons of Haydn’s and Mozart’s music, Ignaz Arnold’s ‘Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart und Joseph Haydn. Nachträge zu ihren Biographien und ästhetischer Darstellung ihrer Werke. Versuch einer Parallele [Postscript to their Biographies and Aesthetic Description of their Works. Attempts at a Parallel]’ published in 1810 in the wake of Haydn’s death, provides the most promising stimulus for a reconsideration of the relationship between their works.6 Arnold, already the author of a landmark volume in early Mozart reception, Mozarts Geist: Seine kurze Biographie und äesthetische Darstellung seiner Werke (Erfurt, 1803), initially appears to nail his colours to the mast, stating that ‘Mozart is indisputably the greatest musical genius of his and all eras’ and – in line with the prevailing view – that ‘Haydn paved the way that Mozart travelled to immortality.’7 After a lengthy biographical excursion on Haydn (taken from Georg August Griesinger’s account), though, he provides a much more nuanced assessment of the relationship, one in which Haydn and Mozart emerge as equals – two sides of the same coin, a ‘holy unity in the most individual diversity’. Both were original geniuses, having positive effects on their surroundings, synthesising stylistic qualities from various quarters and striving successfully to achieve aesthetic beauty; both were ‘equally great, strong and forceful’ in harmonic terms, Mozart looking ‘to clothe his melodies with the force of the harmonies’ and Haydn to conceal ‘his profound harmonies in the roses and mirthful thread of his melodies’.8 While ‘Haydn’s genius looked for breadth’, Mozart’s sought ‘height and depth’.9 Arnold then considered balanced overall qualities: ‘Haydn leads us out of ourselves. Mozart lowers us deeper into ourselves and lifts us above ourselves. That is why Haydn always paints more objective views, and Mozart subjective feelings’ (as examples, Arnold cites The Creation and The Seasons for Haydn and The Magic Flute, La clemenza di Titoand the Requiem for Mozart).10E. T. A. Hoffmann distinguished in likeminded fashion between Haydn and Mozart in his famous review of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony (1810), albeit in more openly poetic terms: while Haydn’s works ‘are dominated by a feeling of childlike optimism’, his symphonies leading us ‘through endless, green forest-glades, through a motley throng of happy people’, Mozart’s take us ‘deep into the realm of spirits . . . We hear the gentle voices of love and melancholy, the nocturnal spirit-world dissolves into a purple shimmer, and with inexpressible yearning we follow the flying figures kindly beckoning us from the clouds to join their eternal dance of the spheres’ (Hoffmann cites Symphony No. 39 in E flat, K 543, as an example).11 All told for Arnold, ‘both geniuses stand there equally forceful, equally charming’.12

Arnold identified two totemic figures achieving sometimes similar, sometimes different goals, always attentive to force and beauty in their music and ever successful at communicating with their respective audiences. In attempting to re-evaluate the relationship between Haydn’s and Mozart’s symphonies, we are best served by revisiting writings from the last decades of the eighteenth century and the first decade of the nineteenth, alongside Arnold’s account. This period includes not only the greatest works by the two composers, but also Mozart’s meteoric posthumous rise in popularity in the 1790s and 1800s and Haydn’s equally dramatic establishment as Europe’s most famous living musician, a status attributable in no small part to his international symphonic successes in Paris and London. In the spirit of Arnold, I shall look first at Haydn’s and Mozart’s ‘Paris’ symphonies, reversing his assessment of the two composers’ impact on their musical environments by considering how the environments may have had an impact on them, especially their orchestration. I shall then turn to Mozart’s Viennese symphonies from the 1780s and Haydn’s ‘London’ symphonies from the 1790s in an attempt to determine how the most powerful and poignant harmonic effects are achieved.

Mozart’s ‘Paris’ Symphony, K 297 and Haydn’s ‘Paris’ Symphonies, nos. 82–7

The locations for which Haydn and Mozart wrote symphonies were quite different – Haydn’s predominantly for Esterházy and only later for Paris and London, and Mozart’s for Salzburg, Vienna and other cities to which he travelled around Europe.13 The Paris symphonies thus offer an ideal viewpoint from which to survey the effect that a particular musical city at a particular time had on symphonies composed by the two men. To be sure, Mozart’s and Haydn’s circumstances were dissimilar when they wrote their symphonies – Mozart, not particularly well known in Paris in 1778 (at least for his adult musical activities), composed his single work for the Concert spirituel while resident in the city, whereas Haydn, already established as a leading figure on the Parisian scene by the mid 1780s, wrote six works for the Concert de la Loge Olympique (1785–6) while still based at home.14 But both composers, faced with a Parisian audience with whom they were fundamentally unfamiliar, would have had to pay especially close attention to the stylistic and aesthetic resonances of their works in an attempt to guarantee success.

Mozart’s letters to his father about his new symphony describe several ways in which he accommodated the Parisian musical public’s taste for orchestral effects. He claimed to have been ‘careful not to neglect le premier coup d’archet – and that is quite sufficient for the “asses” in the audience’; he repeated towards the end of the first movement a passage from the middle that he ‘felt sure’ would please, hearing it greeted with a ‘tremendous burst of applause’ on the first occasion and with ‘shouts of “Da capo”’ on the second; and he played with audience expectations at the beginning of the Finale by moving from piano to forte eight bars later rather than commencing immediately with the anticipated tutti, such that the audience ‘as I expected, said “hush” at the soft beginning, and when they heard the forte, began at once to clap their hands’.15Effects aimed at the musical masses, however, represent only half of the equation; for Mozart was apparently just as concerned with the kind of refined orchestral effects that surfaced in Parisian aesthetic discourse in the third quarter of the eighteenth century.16The diversity of wind effects recommended in treatises – from simple sustained notes and texturally prized combinations of clarinets, bassoons and horns, to carefully placed, not overused thematic-obbligato writing – is reflected in the first movement in particular; each pair of wind instruments (flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns and trumpets) is used independently from and combined with other pairs, reaching a high point in the recapitulation’s secondary theme section (see bars 206–27). Here, all six play sustained notes independent of string lines, featuring a different distribution of instruments each time, in addition to the clarinets–bassoons then horns–oboes offering obbligato two-bar extensions to the theme in thirds. Thus, Mozart immerses himself in French orchestration culture, reflecting and feeding into both the fascination for wind timbre among aestheticians and the desire for immediate sonic gratification among the musical public at large. And, judging by his report of the concert at which the work was premiered, he scored a direct hit.17

Haydn’s ‘Paris’ Symphonies, nos. 82–7, were praised in the Mercure de France (1788) for being ‘always sure in their effect’; unlike other composers, Haydn did not ‘mechanically pile up effect on effect, without connection and without taste’.18 Similar to Mozart’s K 297 in relation to his earlier works in the genre, Haydn’s ‘Paris’ Symphonies were the grandest he had conceived thus far. As for Mozart, the large orchestral forces at Haydn’s disposal allowed not only for big tutti effects on a scale not yet witnessed in his symphonies, but also for a greater degree of textural intimacy on account of the variety of instrumental combinations that could be exploited.

Haydn’s extraordinary success in Paris – his symphonies comprised 85 per cent of those performed at the Concert spirituel between 1788 and 179019 – can be attributed to a number of musical characteristics in nos. 82–7, including simple and beautiful melodies, humour and general splendour;20 his attitude to orchestration contributed to the happy state of affairs too. For Haydn, like Mozart, accommodates the general listener – replicating Mozart’s piano (light scoring) to forte (tutti) effect from the Finale of K 297 in the Finale of his own D major Symphony, No. 86, for example – as well as the connoisseur of sophisticated aesthetic taste. He covers the gamut of effects for winds in their capacity as agents texturally independent of string parts, from ornate obbligato writing (the slow movements of nos. 83, 85 and 87 and trios of nos. 82, 85 and 87) to colour-orientated sustained notes; his first movements also exploit wind sonorities in as meticulous and measured a fashion as Mozart’s corresponding movement of K 297. In No. 85 in B flat, La Reine, Haydn intensifies his employment of independent wind instruments as the movement progresses. Sustained notes in the slow introduction lead to brief oboe–horn echoes in the first theme and a solo oboe presentation of the secondary theme (which is a repeat of the first theme in line with Haydn’s monothematic practice); in the development section, Haydn ups the ante with eighteen bars of sustained winds (flute, oboes, bassoons) that accompany the strings’ near-quotation of the ‘Farewell’ Symphony, with an eight-bar dialogue between oboes and violins, and with emphatic tutti-wind crotchets towards the end; in the recapitulation, as if responding to wind prominence in the development, Haydn introduces the wind right at the start of the first theme in both long-note (horn) and echo (oboe) capacities, the moment of formal arrival thus coinciding with the coming together of the winds’ two principal roles as independent agents in this movement (held notes and thematic presentation).21 No. 86 in D charts a similar course, providing more independent wind writing in the development section (oboe and flute thematic fragments at the beginning; tutti wind in the last sixteen bars) than in the exposition, and new independent roles for the bassoon and oboe and the bassoon and flute in the recapitulation’s primary and secondary themes respectively. Like Mozart in K 297, so Haydn in the secondary themes of his first movements (except No. 87) also makes a point of promoting independent wind participation, even if only in modest fashion. Overall, then, sounds and sonorities constitute important points of communication between Haydn and his audience, just as they feature significantly in French aesthetic discourse. As Ernst Ludwig Gerber remarked about Haydn’s symphonies in 1790, before the ‘London’ symphonies had been written: ‘Everything speaks when he sets his orchestra in motion. Every subsidiary part, an insignificant accompaniment in the works of other composers, often with him becomes a crucial principal part.’22

Mozart’s and Haydn’s attention to the kind of orchestral effects discussed by French aestheticians demonstrates the synergy of compositional environment and compositional style that is so central to understanding not just their symphonies but all other late eighteenth-century symphonic repertories as well. Mozart’s symphonies may have had only equivocal success at the Concert spirituel between 1777 and 1790,23 but Haydn’s utter domination of the orchestral scene in the same period shows how receptivity to listener expectation and subsequent shaping of listener expectation – the positive impact on surroundings mentioned by Arnold – went hand in hand. And the grandeur and intimacy of the ‘Paris’ symphonies ensured that they became pivotal works in the musical careers of both men, helping to shape ensuing stylistic practices and expectations in Haydn’s ‘London’ symphonies, where listener intelligibility was paramount, and in Mozart’s Viennese piano concertos and symphonies, where the sonorous use of orchestral wind instruments in solo and accompanimental roles reached its peak in his instrumental repertory.24

Mozart’s Viennese symphonies and Haydn’s ‘London’ symphonies

Arnold was only one of numerous late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century writers to draw attention to Mozart’s and Haydn’s harmonic and tonal powers. Critical assessments, including those of the London symphonies, were entirely positive where Haydn was concerned. He was praised for his ‘exquisitly [sic] modulated’ Symphony No. 94 (‘Surprise’), for being ‘wholy unrivaled [sic]’ in harmony and modulation in a review of his Symphony No. 102, for ‘continual strokes of genius, both in air and harmony’ in the Symphony No. 103 (‘Drum Roll’) and, more generally, for handling flexibly even old-fashioned harmonic devices, for introducing ‘new modulations, and new harmonies, without crudity or affectation’ and (alongside Mozart) for introducing new practices, such as pedal points in upper registers for the purposes of intense expression.25 Indeed, the skilled cultivation of novelty and unexpectedness – in harmony and other areas – was central to delineating creative genius according to late eighteenth-century German reviewers of instrumental music, and to Haydn’s status as creative genius par excellence.26 In contrast, the early reception of Mozart’s harmonic and tonal procedures was mixed. He received high praise for ‘bold’ harmonies and ‘overwhelming . . . enchanting harmonies’ in Le nozze di Figaro (1789, 1790), for well-judged modulations inter alia that ‘touch our hearts and our sentiments’ (1789), for ‘heavenly harmonies [that] so often moved and filled our hearts with tender feelings’ (1791) and for ‘very excellent beauties’ in modulation (1792).27 But he also elicited criticism for the ‘Haydn’ quartets that are ‘too highly seasoned’ (1787), for such profound, intimate knowledge of harmony that his works in general become difficult for the ‘unpractised ear’ (ungeübten Ohre) (1790) and for ‘frequent modulations . . . [and] many enharmonic progressions . . . [that] have no effect in the orchestra’ in Die Entführung aus dem Serail ‘partly because the intonation is never pure enough either on the singers’ or the players’ part . . . and partly because the resolutions alternate too quickly with the discords, so that only a practised ear can follow the course of the harmony’ (1788).28 Complex harmonic and tonal procedures are not the only features of Mozart’s music that sometimes rendered it problematic for contemporaries, but are self-evidently contributing factors.

Underscoring differences in Haydn and Mozart reception is the impression that effects – including harmonic effects – are a fundamental locus for listener orientation in Haydn’s music, but on occasion a locus for listener disorientation in Mozart’s music. The effect-laden Allegretto of Haydn’s Symphony No. 100 (‘Military’), for example, provides a firm hermeneutic anchor for the Morning Chronicle (1794):

It is the advancing to battle; and the march of men, the sounding of the charge, the thundering of the onset, the clash of arms, the groans of the wounded, and what may well be called the hellish roar of war increase to a climax of horrid sublimity! which, if others can conceive, he alone can execute; at least he alone hitherto has effected these wonders.29

Indeed, the locus classicus of sublimity in Haydn’s music, the arrival of light (‘Und es ward Licht’) in ‘Chaos’ from The Creation, is as forceful a moment of orientation and stabilisation as imaginable, not only resolving the nebulous C minor to C major – ‘from paradoxical disorder to triumphant order’ – but also reverberating well beyond its immediate confines into the rest of Part I.30 In Mozart’s Entführung, in contrast, minor-key arias ‘because of their numerous chromatic passages, are difficult to perform for the singer, difficult to grasp for the hearer, and are altogether somewhat disquieting. Such strange harmonies betray the great master, but . . . are not suitable for the theatre’ (1788).31 Similarly, the perceived lack of coherence that results from Mozart ‘[forgetting] the flow of passion in laboriously hunting after new thoughts’ (1798) and from his ‘explosions of a strong violence’ (1800) also implies disorientation.32

It is likely that the ever self-aware Mozart suspected that audacious harmonic and tonal twists in his late symphonies would challenge some of his listeners; since he never aspired (understandably) to a lack of popularity and repudiated ‘violent’ modulations that ‘drag you . . . by the scruff of the neck’ as well as ‘passion, whether violent or not . . . expressed to the point of disgust’,33 we might surmise that any perceived disorientation (whether positively or negatively parsed) represents disorientation intentionally conveyed. At any rate, the potentially disorientating quality of distant-key modulations was recognised as early as 1782 by Johann Samuel Petri: ‘abrupt transitions’ could be carried out in such a way ‘that the listener himself does not know how he happened to be brought so very quickly into a totally foreign key’.34

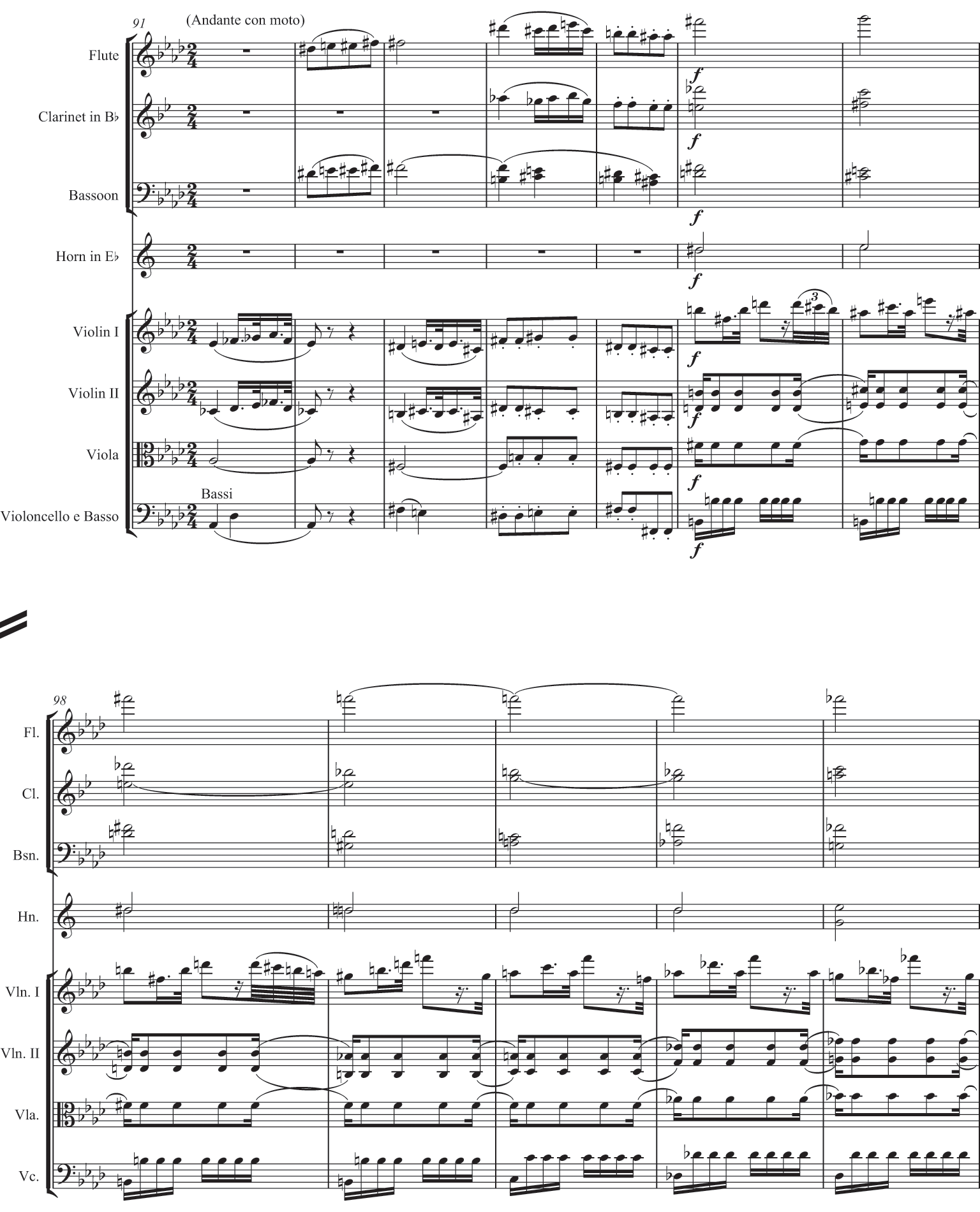

One of Mozart’s most celebrated passages of harmonic daring is the secondary development of the second movement of the Symphony No. 39 in E flat, K 543 (bars 91–108: see Example 7.1). It begins in the distant key of B minor, which, although achieved through the enharmonic interpretation of the C♭ accompanying the shift to A-flat minor (i), is nonetheless startling, perhaps because it occurs a tritone away from the more ‘civilised’ key of F minor that initiates the corresponding section in the exposition, perhaps because it intensifies certain features of the earlier passage (wind minims from the first not second bar of the passage; registral highpoint of the movement in the flute; double-stopped second violins), or perhaps because it comes across as an abrasive realisation of the intimation of the minor mode a few bars earlier.35 But this is only the beginning. In bars 100 and 101 the ![]() and D♭ harmonies (the former a tritone away again from the starting point of B minor) feel completely out of place, but as VI and IV of the tonic A♭ are in the ‘right’ harmonic orbit for this juncture of the movement. If these chords feel strange, and the B minor starting point does too, is it any wonder that we experience disorientation? Surely we are meant to feel this way. Hearing a myriad of harmonic associations and references – B minor as an exploitation of the C♭ contained in the preceding A flat minor;

and D♭ harmonies (the former a tritone away again from the starting point of B minor) feel completely out of place, but as VI and IV of the tonic A♭ are in the ‘right’ harmonic orbit for this juncture of the movement. If these chords feel strange, and the B minor starting point does too, is it any wonder that we experience disorientation? Surely we are meant to feel this way. Hearing a myriad of harmonic associations and references – B minor as an exploitation of the C♭ contained in the preceding A flat minor; ![]() as a reminder of the F minor from the original transition – and hearing the entire passage as a dramatic realisation of the full expressive potential of the original transition material, only tells part of the story. For the passage ultimately inhabits a different expressive world from the rest of the movement – its harmonic disorientation is experienced nowhere else – and thus exists in a kind of self-contained expressive bubble.36 In interpreting it simultaneously as intimately connected to the discourse of the movement and detached from it too, we begin to see how Arnold’s interpretation of the effect of Mozart’s music on the listener (‘[he] lowers us deeper into ourselves and lifts us above ourselves’) might also apply to effects associated with Mozart’s manipulation of harmonic materials in a specific movement.

as a reminder of the F minor from the original transition – and hearing the entire passage as a dramatic realisation of the full expressive potential of the original transition material, only tells part of the story. For the passage ultimately inhabits a different expressive world from the rest of the movement – its harmonic disorientation is experienced nowhere else – and thus exists in a kind of self-contained expressive bubble.36 In interpreting it simultaneously as intimately connected to the discourse of the movement and detached from it too, we begin to see how Arnold’s interpretation of the effect of Mozart’s music on the listener (‘[he] lowers us deeper into ourselves and lifts us above ourselves’) might also apply to effects associated with Mozart’s manipulation of harmonic materials in a specific movement.

Example 7.1 Mozart, Symphony No. 39, II, bars 91–108.

The majority of the development section from the Andante of Mozart’s Symphony No. 41 in C (‘Jupiter’), K 551, occupies a similar position to the secondary development of K 543/ii in relation to its movement as a whole (see bars 47–55: Example 7.2). Mozart expands the material from the transition, prefacing and following the passage with the same harmony, V/d, and setting the passage off from surrounding material with four texturally sparse bars beforehand (two at the end of the exposition and two at the start of the development) and two bars of harmonic water-treading afterwards (V/d, bars 56–7). The entire harmonic ‘business’ of the development (V/d–F) is then carried out in just two bars, leading directly into the recapitulation (bars 58–60). Bars 47–55 fulfil an expressive rather than a functional harmonic purpose: whether or not we agree that ‘with each fresh ascent the suspensions seem more sharply pointed, creating ever greater yearning’,37 we hear impassioned intensity first and foremost. The passage stands inside the movement – building on the harmonic purple patch from the exposition – but outside it too, neatly delineated and expressively transcendent.

Example 7.2 Mozart, Symphony No. 41, II, bars 45–56.

The famous openings to the development sections of K 543/iv and K 550/iv, though briefer than the passages discussed in K 543/ii and K 551/ii, again inhabit expressive territory that thrives as much on incongruity as congruity in relation to surrounding material. To be sure, the G7 statement of the head motive in K 543/iv points ahead to a harmonically daring development (A-flat major and E major/minor follow straight away), but it stands apart too, wrenching us from the comfort of the dominant, B♭, and fulfilling no clear-cut harmonic function in appearing immediately before a statement in A flat. And the opening of the even more tonally audacious development section in K 550/iv is a bolt from the blue, implied diminished harmonies and uncertain harmonic direction conspiring to confuse. (Even late twentieth-century writers express shock, H. C. Robbins Landon citing it as an example of ‘the desperate near-lunacy with which Mozart’s music sometimes grimly flirts’ and Peter Gülke labelling it ‘nearly atonal’ [‘fast atonal’].)38 Such moments draw attention to themselves, as much (probably more) for how they differ from surrounding material than for how they contribute to harmonic strategies over protracted periods.39

Turning to Haydn’s most powerful and poignant harmonic effects in the ‘London’ symphonies, we can begin to appreciate how the two composers sometimes achieve different effects. In the A1 reprise section of the Andante from No. 104 in D (‘London’), Haydn interpolates a colourful passage (bars 105–17); reinterpreting the D♯ from the A section (bars 23–4) enharmonically as E♭, Haydn continues chromatically to F (the third in D-flat harmony), retaining D-flat major harmony for five bars culminating in a pause (bars 109–13: see Example 7.3). He lands gently on this harmony – approaching it from the orbit of the tonic, G, namely iv (105–6) and ♭II6 (107–8) – just as he lands gently on C major for the pause in bar 25 in the A section. If we are disorientated at D-flat major harmony representing our temporary point of arrival, we are disorientated only gradually. The next four bars (114–17), while highlighting the point of furthest tonal remove from the tonic G (C-sharp minor), also orientate the listener: the preceding chromatic bass ascent (B♮–D♭, bars 103–13) reverses as a chromatic descent (C♯–A♯, bars 114–17), signalling the start of a return to the tonic at the precise moment we are furthest from it; and slow tempo and gesture (più largo and pauses) as well as harmonies (C sharp and F sharp) forge connections respectively with the slow introduction and development sections of the first movement.40 Thus Haydn, eschewing Mozart’s abrupt, attention-grabbing harmonic shifts, encourages his listener to experience connections and congruity, rather than a potentially disorientating mix of incongruity and congruity, even at a moment of genuine harmonic audacity.

Example 7.3 Haydn, Symphony No. 104, II, bars 103–19.

Elsewhere in the ‘London’ symphonies, too, Haydn pursues the kind of ‘breadth’ – interpreted here as a forceful harmonic process stretched out over a protracted period and orientating the listening experience – that for Arnold distinguishes his music from Mozart’s. The two most ostensibly surprising and dramatic moments in the first movement of Haydn’s Symphony No. 100 in G (‘Military’) are harmonic effects – the onset of the development section in B flat, after a two-bar general pause, and the forte/fortissimo tutti shunt to ♭VI in the recapitulation. Both moments are integral components of the movement’s narrative, Haydn continually playing with hiatuses and pauses, and exploiting ♭VI harmonies. The portentous end of the slow introduction preceding the main theme (repeated fortissimo quavers in the full orchestra, followed by a tutti fortissimo semibreve pause) leads to written-out hiatuses before two further thematic presentations in the exposition – tutti crotchets and tied flute semibreves in advance of the main theme in the dominant (see bars 72–4); and two bars of accompanimental figuration by itself before the secondary theme (see bars 93–4) – as well as the clearest hiatus of all at the opening of the development. And ♭VI, which first surfaces as augmented-sixth harmony towards the end of the slow introduction (bar 18), appears at the start of the development (B flat, as ♭VI/D) and in augmented-sixth form at climactic, forte/fortissimo junctures later in the section (bars 139, 152 and 162–4). The compressed recapitulation, eradicating the hiatuses of the exposition among other things, explodes in ♭VI, E flat (bar 239), fully exploiting the power that the harmony has accrued during the movement. Neither is its power confined to the first movement: the full orchestra bursts out, fortissimo, in A flat (♭VI) towards the end of the second movement (bar 161), and then again, forte, in the closing stages of the Finale (bars 245ff.).41

Haydn’s moments of harmonic disorientation and destabilisation inevitably function as important catalysts for coherent harmonic discourse; rather than inviting us to focus on disorientation itself as Mozart sometimes does, Haydn encourages us to understand it first and foremost as part of an on-going process.42His ostentatious slow introduction to No. 99 in E flat is derailed by a C-flat pause (bar 10), and further destabilised by solid preparation for a key (C) that will not materialise; indeed, the V/E flat, final-bar appendage to the introduction in preparation for the tonic at the opening of the exposition feels incongruous and out of place, at least in relation to the music that precedes it. Both unruly elements fuel further discourse: recalcitrant C♭s appear in the exposition’s transition (bar 35, marked sf), shortly before B♮s inflect the music to C minor en route to the dominant; C major initiates the development section, after a stop–start opening in which pauses and harmonic orbit (C) invoke the uncertainties of the slow introduction, but is now part of a smooth, rather than an abrupt and disquieting, modulatory process; and C♭s feature in imitative figures at the end of the development that help re-establish V/E flat, in Neapolitan-sixth harmony (bar 165) that reconfirms the tonic E flat at the end of the secondary theme in the recapitulation, and then as unobtrusive contributors to diminished harmony (bars 174–5), thus illustrating C flat’s assimilation as a harmonically congruous and cooperative element of the discourse.43 In the slow introduction of No. 102 in B flat, too, a harmonically disorientating gesture – an exact repeat of bar 1’s unison B♭ five bars later in bar 6, where it disturbs forward momentum, in effect beginning the Symphony again with a second tonality-defining call-to-attention – resurfaces on various occasions in the first and third movements, the incongruous ‘pillars’ being eventually assimilated as congruous elements of the discourse.44

Of course, Mozart’s and Haydn’s most powerful harmonic utterances in the Viennese and ‘London’ symphonies sometimes convey similar effects. In the recapitulation of the Finale of Mozart’s Symphony No. 38 in D, K 504 (‘Prague’), for example, we are likely to admire the force with which the big tutti chords from the development reappear (as iv6, ♮III7, ♭VI; bars 228–32, 236–40, 244–5), orientating us to the tonic, rather than marvel at how the climactic chords themselves may temporarily disorientate. But differences in Mozart’s and Haydn’s harmonic effects remain tangible on many occasions, and are testimony to the incisively individualistic modus operandi of each composer. In spite of the seriousness with which Mozart essays his harmonic course in his most audacious passages, the self-conscious dimension to his daring manipulations – he intends us surely to reflect upon the ease with which he can disrupt a particular movement only to bring it effortlessly back into line – may strike a chord not only with Haydn’s highly cultivated harmonic disorientations and reorientations but also with Haydn’s self-conscious attention to the compositional mechanisms of his own creation, as exhibited in his much-touted wit and humour.45 If in fact a parallel can be drawn here too, the pervasive image of Mozart and Haydn as two sides of the same coin again comes to mind. In our musical and historical imaginations the symphonic achievements of the two men are – and are likely to remain – inextricably intertwined.

Notes

1 The Atlas, 591 (10 September 1837), 586.

2 As given in , Mozart: A Documentary Biography, trans. , and (3rd edn, London, 1990), 472–3.

3 Quoted in , Concert Life in London from Mozart to Haydn (Cambridge, 1993), 128.

4 The Quarterly Musical Magazine and Review, 8 (1826), 234. The same magazine three years earlier had offered a different take on the relationship among the three composers, but one that still downplayed ’s significance: ‘The symphonies of Haydn may perhaps be occasionally more distinguished by his felicitous use of particular instruments, for his simplicity and playfulness, and Beethoven’s as more powerful, more romantic and original, but considering all the attributes that are required to form the beau ideal or an actual model of composition in this species, those of Mozart approach the nearest to perfection’, The Quarterly Musical Magazine and Review, 5 (1823), 233–6; review of Mozart’s Six Grand Symphonies, arranged for the Piano Forte, with Accompaniments.

5 See , ‘The Rochlitz Anecdotes: Issues of Authenticity in Early Mozart Biography’, in , ed., Mozart Studies (Oxford, 1991), 1–59, esp. 14–16 (anecdotes dating from 1798); , ‘Remarks on the Development of the Art of Music in Germany in the Eighteenth Century’, trans. , in , ed., Haydn and His World (Princeton, 1997), 321–94, esp. 357–74; , Haydn: Chronicle and Works. Haydn in England, 1791–1795 (London, 1976), 273; , Lebensbeschreibung des k. k. Kapellmeisters Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Prague, 1798), trans. as Life of Mozart (London, 1956), 10, 30–1, 33–4, 59–61 and 68–9. For a discussion of Niemetschek’s subtle adjustments to the second edition of his biography – eliminating the dedication to Haydn among other changes – as redolent of the superiority of Mozart over all who had come before (Haydn included), see , ‘Across the Divide: Currents of Musical Thought in Europe, c. 1790–1810’, in , ed., The Cambridge History of Eighteenth-Century Music (Cambridge, 2009), 663–87, at 668–9.

6 In , Gallerie der berühmtesten Tonkünstler des achtzehnten und neunzehnten Jahrhunderts. Ihre kurzen Biografieen, karakterisirende Anekdoten und ästhetische Darstellung ihrer Werke, vol. I (Erfurt, 1810), 1–118. For brief comparisons from three years earlier in the context of a study of German music in general, see , ‘Charakteristik der deutschen Musik’, Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, 9 (1806–7), cols. 699–700.

7 Arnold, Gallerie, 3 and 79: ‘Mozart ist unstreitig das größte musikalische Genie seines und aller Zeitalter’; ‘Er [Haydn] bahnte den Weg, auf dem Mozart zur Unsterblichkeit einging’.

8 Ibid., 13 (‘eine heilige Einheit in der individuellsten Mannigfaltigkeit’), 114–15 and 116 (‘beide [sind] in der Harmonie gleich groß, gleich stark und kräftig’, and ‘Mozart sucht seine Melodien mit der Kraft der Harmonien zu bekleiden. Haydn versteckt seine tiefen Harmonien unter Rosen und Mirthengewinde seiner Melodien.’).

9 Ibid., 117: ‘Haydns Genius sucht die Breite, Mozarts Höhe und Tiefe.’

10 Ibid.: ‘Haydn führt uns aus uns heraus. Mozart versenkt uns tiefer in uns selbst und hebt uns über uns. Daher malt Haydn auch immer mehr objektive Anschauungen, und Mozart die subjektiven Gefühle.’

11 Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, 12 (1809–10), col. 632; as given in , ed., E. T. A. Hoffmann’s Musical Writings: ‘Kreisleriana’, ‘The Poet and the Composer’, Music Criticism, trans. (Cambridge, 1989), 237–8.

12 Arnold, Gallerie, 117 (‘beide Genien stehen gleich kraftvoll, gleich anmuthig da’).

13 No single Haydn symphony is known to have been composed for Vienna exclusively; see , The Symphonic Repertoire, vol. II: The First Golden Age of the Symphony: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert (Bloomington, 2002), 2. Mozart might have written his final three symphonies with a potential trip to London in mind, although other possibilities include planned subscription concerts in Vienna and the composer’s desire to sell or publish an ‘opus’ of three symphonies; see , Mozart’s Symphonies: Context, Performance Practice, Reception (Oxford, 1989), 421–2.

14 Haydn’s symphonies nos 90–2 (1788–89) were also commissioned for the Concert de la Loge Olympique in Paris.

15 See , ed. and trans., The Letters of Mozart and His Family, 3rd rev. edn, ed. and (New York, 1985), 553 (12 June 1778) and 558 (3 July 1778). Mozart also wrote a second middle movement for the work to accommodate the wishes of Joseph Le Gros, director of the Concert spirituel, while acknowledging that the original movement was ‘a great favourite with me and all connoisseurs’. Anderson, Letters, 565 (9 July 1778).

16 See , ‘The Aesthetics of Wind Writing in Mozart’s “Paris” Symphony, K 297’, Mozart-Jahrbuch2006, 329–44. The remainder of the paragraph is drawn from the findings of this article.

17 Anderson, Letters, 557–8 (3 July 1778).

18 Given in , Haydn: The ‘Paris’ Symphonies (Cambridge, 1998), 22.

19 Ibid., 21.

20 See Harrison’s musical discussion in ibid., 45–99.

21 The oboe’s presentations of the secondary theme begin with two-bar sustained notes, thus also integrating the two roles.

22 , Historisch-biographisches Lexicon der Tonkünstler2 vols.(Leipzig, 1790, 1792), vol. I, col. 610: ‘Alles spricht, wenn er sein Orchester in Bewegung setzt. Jede, sonst blos unbedeutende Füllstimme in den Werken anderer Komponisten, wird oft bei ihm zur entscheidenden Hauptparthie.’

23 See Keefe, ‘Aesthetics of Wind Writing’, 342.

24 On listener intelligibility in Haydn’s Paris and London symphonies, see , Haydn and the Enlightenment: The Late Symphonies and Their Audience (Oxford, 1990), 75–198; and, in condensed form, , ‘Orchestral Music: Symphonies and Concertos’, in , ed., The Cambridge Companion to Haydn (Cambridge, 2007), 95–111, at 107–111. On wind roles in Mozart’s piano concertos and inter alia Mozart’s Viennese symphonies, see , Mozart’s Piano Concertos: Dramatic Dialogue in the Age of Enlightenment (Woodbridge and Rochester, NY, 2001); , Mozart’s Viennese Instrumental Music: A Study of Stylistic Re-Invention (Woodbridge and Rochester, 2007), 43–62 and 137–64; and , ‘“Greatest Effects with the Least Effort”: Strategies of Wind Writing in Mozart’s Viennese Piano Concertos’, in , ed., Mozart Studies (Cambridge, 2007), 25–42.

25 See Landon, Haydn in England, 49, 287 and 295; Gerber, Historisch-biographisches Lexikon der Tonkünstler, vol. I, col. 610; , in Chambers’s Cyclopaedia, as given in Zaslaw, Mozart’s Symphonies, 511; Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, 1 (1798–9), col. 153.

26 , German Music Criticism in the Late Eighteenth Century: Aesthetic Issues in Instrumental Music (Cambridge, 1997), 99–133, esp. 123.

27 Deutsch, Documentary Biography, 345, 372 and 355; , New Mozart Documents: A Supplement to O. E. Deutsch’s Documentary Biography (London, 1991), 123 and 124.

28 Deutsch, Documentary Biography, 290; Gerber, Historisch-biographisches Lexikon der Tonkünstler, vol. I, col. 979; Deutsch, Documentary Biography, 328.

29 Given in Landon, Haydn in England, 247.

30 See James Webster, ‘The Sublime and the Pastoral in The Creation and The Seasons’, in Clark, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Haydn, 154–5.

31 Deutsch, Documentary Biography, 328.

32 Thomas Holcroft quoted by Landon in Haydn in England, 273; Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung (November 1800), given in , Haydn: Chronicle and Works. Haydn: the Late Years, 1801–1809 (London, 1977), 408.

33 Anderson, Letters, 378 (20 November 1777) and 769 (26 September 1781).

34 , Anleitung zur praktischen Musik, rev. edn (Leipzig, 1782), 281; as given in , The Free Fantasia and the Musical Picturesque (Cambridge, 2002), 41.

35 For an extended analysis of this movement see , ‘A Tritone Key Relationship in the Bridge Sections of the Slow Movement of Mozart’s 39th Symphony’, Music Analysis, 5/1 (1986), 59–84.

36 Leo Treitler, in his narrative reading of K 543/ii, calls the passage an ‘emotional roller coaster’, and the music from bar 90 onwards ‘unpredictable and psychologically complex . . . very operatic’. See ‘Mozart and the Idea of Absolute Music’, in Music and the Historical Imagination (Cambridge, Mass., 1989), 176–215, at 211.

37 , Mozart: The ‘Jupiter’ Symphony (Cambridge, 1993), 58.

38 , Haydn: Chronicle and Works. Haydn at Eszterháza, 1766–1790 (London, 1978), 609; , ‘Triumph der neuen Tonkunst’: Mozarts späte Sinfonien und ihr Umfeld (Kassel and Stuttgart, 1998), 251.

39 On parallels between the K 550/iv passage and a passage from the corresponding juncture of the first movement of Mozart’s final piano concerto, K 595 in B flat, see Keefe, Mozart’s Viennese Instrumental Music, 77–8. Strong contrasts – including harmonic contrasts – become an increasingly common characteristic of Mozart’s late chamber and orchestral works, featuring in his processes of stylistic reinvention; see Keefe, Mozart’s Viennese Instrumental Music, 105–33 and 167–200.

40 The slow introduction to No. 104 is marked Adagio and delineated by two pauses at the beginning and one at the end; the development section moves through C-sharp minor and F-sharp minor (bars 145–54) en route to E minor (bar 155).

41 The Finale of No. 100, like the first movement, also incorporates written-out musical hiatuses, with harmonic ramifications. For example, the final eight bars of the main theme are preceded by a woodwind pattern that ends with a hiatus one beat earlier than we expect (lacking the final crotchet in bar 40 that appears in the corresponding segment in the violins in bar 38); pause bars and harmonic stasis delay the arrival of the secondary theme (see bars 77–85); and the development section begins in stop–start fashion (bars 117–28), replete with ostentatious timpani solo and reaffirmation of the dominant. On issues of through-composition and cyclic integration in general in Haydn’s symphonies, see , Haydn’s ‘Farewell’ Symphony and the Idea of Classical Style: Through-Composition and Cyclic Integration in His Instrumental Music (Cambridge, 1991).

42 For a lengthy discussion of Haydn’s destabilisation effects – harmonic and otherwise – see Webster, ‘Farewell’ Symphony, 127–55.

43 Webster provides an extended analysis of the first movement of No. 99, explaining how it ‘employs remote keys and sonorities so pervasively that they become the primary source of cyclic integration’ in ibid., 320–9 (quotation from 320).

44 This process in No. 102 is documented in , ‘Dialogue and Drama: Haydn’s Symphony No. 102’, Music Research Forum, 11/1 (1996), 1–21.

45 See, in particular, , Haydn’s Ingenious Jesting with Art: Contexts of Musical Wit and Humor (New York, 1992); , ‘Haydn, Laurence Sterne and the Origins of Musical Irony’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, 44 (1991), 57–91. Such a parallel does not mean to imply that the kind of effects discussed above in Haydn’s London symphonies are necessarily devoid of humour. Indeed, manifestations of ‘obsessive repetition’ in the first movement of No. 100, akin to the aforementioned written-out hiatus effects, have a humorous dimension; see Wheelock, Haydn’s Ingenious Jesting with Art, 178–82.