9 Cyclical thematic processes in the nineteenth-century symphony

Introduction

Several authors in this volume cite the famous (if uncorroborated) conversation between Sibelius and Mahler, in which Sibelius valued the symphony for ‘the profound logic that created an inner connection’ between its component ideas, and Mahler responded that ‘a symphony must be like the world. It must embrace everything’.1 Appealing as these comments are as indicators of the two composers’ aesthetics, they also have value because they apostrophise neatly the twin aspirations of thematic rigour and monumentality that constituted dominant nineteenth-century symphonic imperatives. Although it would be quite wrong to construe this as a simple dichotomy – even the most expansive symphonies aspire to thematic coherence, and modest works are no more likely to emphasise overarching motivic processes – the challenge of expressing both high communal ideals and comprehensible thematicism, which gained currency as a central inheritance of the Beethovenian symphonic achievement, has at the very least to be regarded as a productive tension.

As the century progressed, the thematic element of this equation came increasingly to be construed cyclically, as a technique that had to encompass the cycle of movements as well as a work’s component forms. In thematic terms, the Beethovenian imperative of originality necessitated a search for ways to imbue whole works with a higher-level material integrity, which depended on strategies ranging from isolated but marked quotations to extensive cross-movement processes of variation and derivation and the wholesale revisiting of passages.2 Such processes are also often the lynchpin of a symphony’s extra-musical meaning. The technical features of ‘absolute’ music – those aspects that seem autonomous of meaning and function – are simultaneously the basis of its programmatic aspirations, reflecting the characteristically Romantic conviction that music’s claim to aesthetic superiority lay in its ability to capture essential meanings in the play of tones itself, apart from any dependence on text.3

Widespread though the association of Beethoven with cyclical technique is, however, his status as its progenitor is far from self-evident. In the first place, various commentators have noted integrative techniques in earlier music: James Webster’s extensive study of cyclic integration in Haydn’s ‘Farewell’ Symphony is a substantial case in point, and Mary Sue Morrow and Michael Spitzer note similar eighteenth-century strategies in chapters 3 and 6 above.4 Moreover, overt thematic relationships extending across, as well as within, movements are comparatively rare in Beethoven’s symphonies (subcutaneous relationships are of course manifold). The two most well-known examples – the Fifth and Ninth symphonies – hardly match the adventurous cyclical techniques employed by Mendelssohn and Schumann, or even the referential use of the idée fixe in Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique. And the Eroica, as the third claimant in this respect, is even more tenuous: such overt cyclicity as can be detected in the work turns on the plausibility of allowing the famous dissonant C♯ in the first movement’s main theme to act as a ‘pitch-class motive’ resurfacing at later points in the Symphony, for example in the Scherzo’s coda (this and other structural principles in Beethoven’s symphonies are considered by Mark Anson-Cartwright in Chapter 8).

The thematic links commonly detected in the Fifth Symphony are, furthermore, far from unequivocal. Leaving aside the reprise of Scherzo material preceding the Finale’s recapitulation, which functions more as a wholesale sectional transplantation than as an integrated transformation of a thematic idea, claims of thematic ‘unity’ depend above all upon the provenance of the rhythmic cell, which comprises the first movement’s famous ‘fate’ motive, and is understood to recur in the main themes of the Scherzo and Finale. These are hardly definitive connections: the rhythmic shift from upbeat to downbeat between first-movement and Scherzo forms of the motive is especially problematic for any claim of unambiguous derivation. At best (and accepting the indisputable connection between third and fourth movements), the inter-movement links have to be regarded as implications available to the receptive ear, rather than as analytically unassailable facts.

Cross-referencing in the Ninth Symphony is, in contrast, unmistakable, because inter-movement recall is a matter of near-literal quotation: the main themes of the first three movements pass by parenthetically in the Finale’s introduction, intercut with the recitative-like material of the celli and basses, which anticipates the baritone’s entry with the words ‘O Freunde, nicht diese Töne!’. Quotation is, however, no guarantee of large-scale coherence. On the contrary, the piecemeal quality of the references here secures the recall of prior movements at the expense of large-scale integration: the quotations are disconnected fragments, which are forced apart by the vocal aspirations of the lower strings. And when the baritone later pointedly rebuffs the return of the Schrekensfanfare in preparation for the vocal version of the ‘Ode to Joy’ theme, the fragmentary character of Beethoven’s prior-movement synopsis gains fresh significance. The Finale’s ambition, it turns out, is not to synthesise the material of the whole work in a summative instrumental conclusion, but to reject that idea in favour of a design that subsumes the instrumental symphony as a whole into a final realisation of the music’s emergent vocality (chapters 2, 8 and 14 all broach this matter).5 The point of Beethoven’s cross-referencing is, in other words, fragmentation, not synthesis.

It is in this light that another plausible inter-movement relationship might be understood: the adumbration of the ‘Ode’ theme in the first movement’s second subject, explained in Example 9.1. As commentators have observed, this anticipation has tonal as well as thematic significance, because the secondary key it establishes (B-flat major) prefigures that of the slow movement, and of the Turkish march setting the words ‘Froh, wie seine Sonnen fliegen durch des Himmels prächt’gen Plan’ in the Finale.6 Viewed from the position of the Finale’s first vocal stanza, however, this connection looks less like an instance of integration, and more like a prophecy of the instrumental movements’ provisionality. In the first movement’s lyrical second theme is contained the seeds of the purely instrumental Finale’s demise.

Example 9.1 Beethoven, Symphony No. 9, I, subordinate theme and IV, ‘Freude’ theme.

This chapter explores the post-Beethovenian legacy of cyclical thinking, focussing on its treatment by six composers: Berlioz, Schumann, Liszt, Tchaikovsky, Bruckner and Mahler. I restrict consideration to overt thematic recurrence and transformation; whilst not denying the presence of concealed thematic, harmonic or tonal features reinforcing cyclical coherence, my aim is to scrutinise only unequivocal surface relationships, as the most analytically and historically tractable evidence of the technique. And since purely musical elements in all of these works support programmatic or narrative ambitions, I also pay attention to their extra-musical connotations, which range from the transparently intentional (Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique) to the strongly implied (Bruckner’s Fifth Symphony).

The ‘Romantic generation’: Berlioz, Schumann and Liszt

The techniques of thematic integration exhibited in the first generation of post-Beethovenian symphonies can be understood not as responses to an incipient property of Beethoven’s symphonies themselves, but as realisations of a dual ideal of musical autonomy and metaphysical significance, which sought evidential verification in Beethoven’s examples. The symphonies of Berlioz, Schumann and Liszt are exemplary: all three composers overlaid their movement cycles with overt and variously developmental thematic processes, supporting more-or-less explicit programmatic agendas, to an extent far exceeding anything that Beethoven attempted in the symphonic domain.7

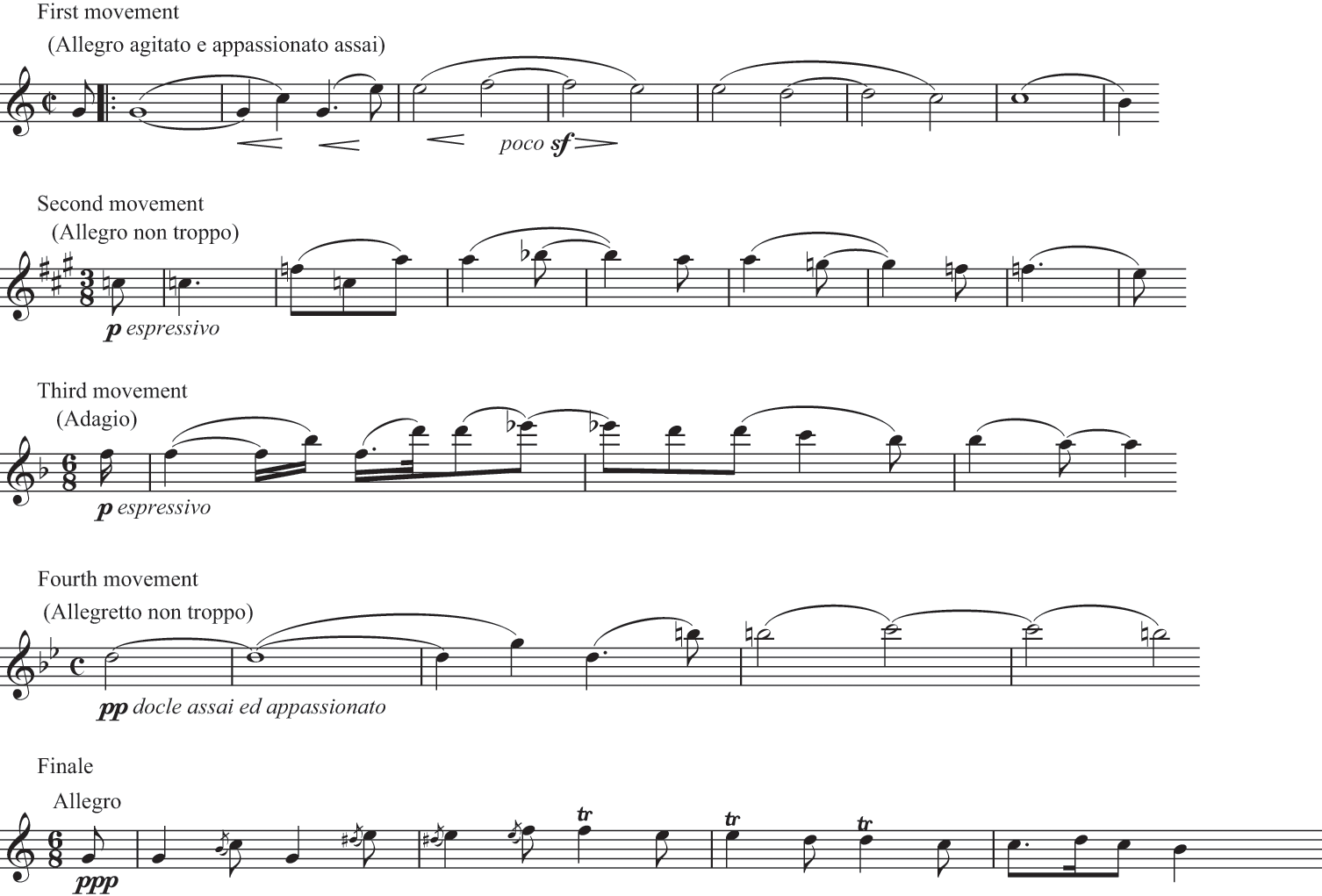

The notion of programmatic cyclicity is most blatant in Berlioz’s usage. The Symphonie fantastique instantiates the notion of the idée fixe, which, as Berlioz’s first programme for the work identified, functions as ‘a musical thought, whose character . . . [the artist] finds similar to the one he attributes to his beloved’.8 This acts as a kind of narrative anchor, which orientates the movement-by-movement scene changes in relation to the protagonist’s mental projection of the beloved.9Example 9.2 compares the variants of the idée fixe as they occur in the five movements.

Example 9.2 Berlioz, Symphonie fantastique, variants of the idée fixe.

Berlioz here marries cyclical and extra-musical elements in a way that has long-lasting influence. Most importantly, the prime form of the idée fixe is also the first theme of the first movement’s sonata form. The heroic subjectivity that is often imputed to Beethoven’s main themes is thereby made explicit, because the theme’s human agency is nominated in the programme. And because the idée fixe does not represent simply the artist himself, but rather the idealised object of his affections, Berlioz pulls off the trick of embodying in a single idea both the artist as narrative protagonist and also a relationship between characters (artist and beloved), which allows him to foster the illusion of an unfolding plot.

As this notion develops across the piece, it exemplifies with exceptional clarity the Romantic perception that it is precisely instrumental music’s autonomy that allows it to capture essential meanings without direct textual assistance. Thus the inter-movement changes of topic that compel variation of the idée fixe (waltz, pastoral, march, gigue) at once facilitate the progression of symphonic movement types (two dances frame an adagio and precede a rondo finale), whilst also providing the circumstances for the changes of scene and character that convey the extra-musical narrative. The difference between the central character and the beloved as an object of perception is underscored from the second movement onwards, because from this point Berlioz detaches the idée fixe from main-theme functionality: in the second movement and Adagio, it appears in the contrasting middle section; in the March as a fleeting expansion of the final structural cadence; and in the Finale as an episode in the multi-part introduction. Altogether, although the treatment of the idée fixe is neither as transformationally extensive as Liszt’s practice, nor as developmentally exhaustive as the cyclical techniques of many later-century practitioners, its capacity to sustain topical variety furnishes a strikingly clear model for the integration of cyclical and programmatic agendas.

In Harold en Italie, Berlioz takes the notion of the symphonic subject as narrative protagonist a stage further, by embodying him in a concertante instrument (the solo viola): as a result, the protagonist is not only a theme, but also a soloist who has physical presence. The critical inter-movement thematic links are appraised in Example 9.3. The first clear cross-reference is the recurrence of the introduction’s ‘Harold’ theme as the soloist’s response to the pilgrims’ ‘canto’ in the slow movement (beginning Fig. 23). Berlioz uses the same device in the Serenade, folding the viola’s ‘Harold’ theme into the movement’s central Allegretto. Both movements exploit a comparable effect: as Berlioz himself put it, the theme is ‘superimposed onto the other orchestral voices . . . without interrupting their development’, reflecting Harold’s character as a ‘melancholy dreamer’ who is ‘present during the action but does not participate in it’.10In this respect, the ‘Harold’ theme is the direct antithesis of the Symphonie fantastique’s idée fixe: as the protagonist’s projection of the beloved, the latter is changed by its topical and expressive circumstances; the former, however, is the protagonist himself, and (at least before the Finale) remains largely invariant in the midst of topical change.

Example 9.3 Berlioz, Harold en Italie, variants of the ‘Harold’ theme.

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of Harold en Italie is the direct invocation of Beethoven’s Ninth in the succession of prior-movement quotations beginning the Finale, the ‘Orgy of the Brigands’. Like Beethoven, Berlioz begins his Finale with an intercutting between new and old material: the introduction, first-movement main theme, Pilgrims’ March and Serenade are all rejected in turn; finally, the ‘Harold’ theme appears, now as a genuine variant rather than a straight quotation. This is, however, quickly dissolved through a kind of textural liquidation, and the brigands’ music asserts itself definitively as the start of the sonata action six bars after Fig. 40. The movement yields one final cross-reference: ten bars after Fig. 55, the pilgrims’ canto reappears played by an off-stage string trio, which the soloist turns into a quartet by entering eleven bars later. This material again dissipates, and the brigands assert themselves for the rest of the Symphony.

As Mark Evan Bonds has explained, the effect here is diametrically opposed to that achieved by Beethoven. There is no narrative of transcendence; instead, both Harold himself, and the solo instrument that represents him, disappear.11 At the end, Harold is affiliated with the pilgrims, and so with something approximating the work’s moral compass; but this identification counts for nothing, and the last word is given to the surrounding bacchanale. In a sense, Harold en Italie and the Symphonie fantastique converge in their use of cyclical techniques to invert rather than confirm the Beethovenian struggle–victory symphonic argument. Different though the technique is in each case, their common ground is a shared concept of the narrative goal as a negation of ‘utopian semiosis’, to use Michael Spitzer’s apt term, either in the diabolical afterlife of the ‘Witches’ Sabbath’ or the moral vacuum of the ‘Brigands’ Orgy’.12

Schumann’s debt to Berlioz is not only musically implicit, but also textually explicit, because, as David Brodbeck has addressed in Chapter 4, Schumann famously reviewed the Symphonie fantastique in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik.13 In many ways, Schumann’s symphonic project can be understood as an attempt to synthesise three lines of symphonic influence: Beethoven’s goal-orientated dynamic; Berlioz’s conjunction of thematic process and programmatic (literary) narrative; and (as Brodbeck stresses) a lyric monumentality taken from Schubert’s ‘Great’ C major Symphony, the first performance of which Schumann was in part responsible for in 1839.14

All of Schumann’s four symphonies and the Overture, Scherzo and Finale (in many respects a symphony manqué) exhibit inter-movement thematic relationships. The technique is most weakly represented in the Symphony No. 1, in which Schumann is primarily concerned to supply conjunctive links between adjacent movements rather than overarching thematic processes. The motto theme with which the first movement’s introduction begins – which, as John Daverio explains, was originally conceived as a setting of the final lines of a poem by Adolph Böttger (‘O wende, wende deinen Lauf / Im Tale blüt der Frühling auf’: ‘Oh desist, desist from your present course / Spring blossoms in the valley’) – adumbrates the first themes of both the first and second movements, as Example 9.4 reveals.15 The reappearance of the motto’s contour in the slow movement’s theme, however, acts more as a memorial trace than a stage in a cyclical process. Conversely, the prefiguring of the Scherzo’s theme at the end of the Larghetto, which as Example 9.5 shows is at once the slow movement’s coda and the transition into the third movement, functions as an adumbration analogous to the relationship between the first movement’s introduction and its exposition. Schumann’s ruse here is to reconceive this device as an inter-movement rather than intra-movement strategy.

Example 9.4 Schumann, Symphony No. 1, I and II, motto theme.

Example 9.5 Schumann, Symphony No. 1, II, bars 112–17 and III, bars 1–5.

Anticipations of the Scherzo are worked into the slow movement at other points. Example 9.6 for instance reveals that, whereas the end of the Larghetto adumbrates the Scherzo’s head motive, the slow movement’s first episode (beginning bar 25) presages its continuation, thereby giving the impression that the Scherzo pieces together material that the slow movement presents disparately.

Example 9.6 Schumann, Symphony No. 1, II, bars 25–6 and III, bars 5–8.

Such connections, however, dissipate in advance of the Finale, which is thematically self-contained. The highly provisional ending of the Scherzo, which comprises a syncopated, fragmentary liquidation of the material of Trio 1, consequently serves to underscore the dissipation of the tentative cyclical attitude with which the first three movements are associated.

The technique of supplying a motto theme in the first movement’s introduction, which subsequently generates a web of relationships, is taken up and greatly expanded in the Symphony No. 2. The introduction begins with a composite of two significant ideas, identified in Example 9.7: the motto carried by the brass, labelled ‘a’; and the chromatic string counterpoint, labelled ‘b’.16 These two motives relate to the first movement’s sonata form in different ways. The motto does not generate the first theme, but rather recurs summatively in the coda (bars 339–46); and motive ‘b’ reappears, in inversion, as part of the second-theme group (from bar 276). In other respects, Schumann greatly expands the adumbrative model developed in the Symphony No. 1. The motivic fragments presented in bars 25–33, which cede to the motto in bars 34–6, supply the basis of the first theme and the transition in the exposition. The relationship between motto and first-movement sonata is as a result more complex than the straightforward adumbrative process evident in the Symphony No. 1. In effect, the motto is detached from the sonata action, serving as a structural marker, but the adumbrative function of the introduction is preserved through the inclusion of significant additional material.

Example 9.7 Schumann, Symphony No. 2, I, bars 1–4.

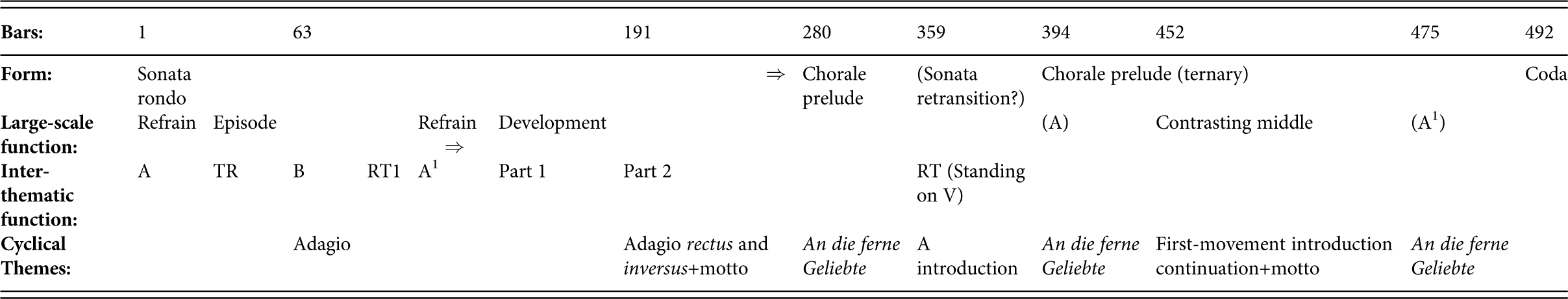

The Scherzo yields two motivic traces of the first movement. Its main subject is a variant of the figure introduced at bar 341 in the first movement’s coda; and the motto theme recurs in the Scherzo’s climactic final cadence, bars 384–90. The Adagio, in contrast, anticipates the Finale, which constitutes the Symphony’s cyclical centre of gravity. The Finale’s form is famously problematic. Table 9.1 attempts clarification, and additionally explains the formal positioning of material from earlier in the Symphony. The first intimation of cyclical thinking emerges with the second theme (bar 63), which comprises a major-key variant of the Adagio’s main theme. This material is revisited in inversion in the central episode of the development (bar 191), joined by its prime form in imitation in the cellos and basses from bar 213, an event marked by the entry of the first movement’s motto over a punctuating authentic cadence (bars 207–10). The subsequent dissolution of this material leads at bar 280 to the movement’s most problematic event: Schumann introduces a new chorale theme, quoting Beethoven’s An die ferne Geliebte, which thereafter engulfs the sense, thus far attained, that the Finale is a sonata rondo. In effect, the rondo design is liquidated by bar 279, and replaced with an expanded chorale prelude.17

Table 9.1 Schumann, Symphony No. 2, IV, form and distribution of themes

Yet although this seems to open up a rift in the design, the topical shift that accompanies it has the long-range effect of enabling the Symphony’s most spectacular cyclical coup. Following the impressive 35-bar standing on V in bars 359–93, the chorale stabilises in the tonic major from bar 394, initiating a tonally closed presentation phrase sealed by a perfect cadence in bars 445–51. Schumann then grafts the chorale-like material of the first movement’s introduction (beginning bar 15) on as a continuation phrase, shifting to a 3/2 metre in l’istesso tempo to accommodate its distinct metrical character. At bar 475, we see that this is the contrasting middle of a ternary form: An die ferne Geliebte reappears as an A reprise, punctuated throughout with assertions of the motto theme, leading to a decisive perfect cadence in bars 488–92, after which the coda begins. By rejecting the rondo form and replacing it with a chorale prelude, Schumann establishes a topical environment that is conducive to the wholesale restoration of first-movement material, framed as a closed form which, because it draws on a Beethovenian lied, houses a ‘humanised’ (or perhaps secularised) sacred topic.

Superficially, the Symphony No. 3 seems less densely constructed than No. 2. Schumann’s strategy here is to divide the cyclical thematic action into two threads, which unite at the Symphony’s close. The first concerns the harmonic properties of the first movement’s main theme, rather than its developmental potential. As Example 9.8a reveals, in its exposition form, the theme displays a tendency to pull towards the dominant, which the rest of the first-theme group does not satisfactorily redress.

Example 9.8a Schumann, Symphony No. 3, I, bars 1–5.

The critical agent of this attraction is the theme’s ![]() figure, which associates with a motion onto

figure, which associates with a motion onto ![]() that is never properly counteracted. The recapitulation, quoted in Example 9.8b, exacerbates this, because it begins over a rhetorically marked

that is never properly counteracted. The recapitulation, quoted in Example 9.8b, exacerbates this, because it begins over a rhetorically marked ![]() chord (this strategy is taken up again in Chapter 10). Thereafter, the underlying V finds no resolution within the first-theme group, a characteristic that shifts the recapitulation’s harmonic centre of gravity towards the second group’s closing perfect cadence (bars 515–27). In an extraordinary stroke of large-scale planning, Schumann effectively suspends this issue until the progression preparing the Finale’s coda (bars 394–8), where, as Example 9.8c shows, the first-movement main theme is recalled triumphantly and made to function as the elaborative material of the Symphony’s culminating tonic cadence. Again, the

chord (this strategy is taken up again in Chapter 10). Thereafter, the underlying V finds no resolution within the first-theme group, a characteristic that shifts the recapitulation’s harmonic centre of gravity towards the second group’s closing perfect cadence (bars 515–27). In an extraordinary stroke of large-scale planning, Schumann effectively suspends this issue until the progression preparing the Finale’s coda (bars 394–8), where, as Example 9.8c shows, the first-movement main theme is recalled triumphantly and made to function as the elaborative material of the Symphony’s culminating tonic cadence. Again, the ![]() figure is crucial here; whereas in the first movement it acts as a destabilising feature, here it collaborates with the cadential voice leading, as part of the decisive

figure is crucial here; whereas in the first movement it acts as a destabilising feature, here it collaborates with the cadential voice leading, as part of the decisive ![]() soprano line. In this way, a cyclical thread left hanging by the first movement is picked up as a decisive, framing structural event.

soprano line. In this way, a cyclical thread left hanging by the first movement is picked up as a decisive, framing structural event.

Example 9.8b Schumann, Symphony No. 3, I, bars 411–16.

Example 9.8c Schumann, Symphony No. 3, V, bars 394–9.

This gesture is additionally important because it forms the terminus of the work’s second thematic thread, which centres on the principal subject of the fourth movement, itself a quotation of the E-flat Prelude from Book I of Bach’s Well-tempered Clavier, marked ‘x’ in Example 9.9a. Examples 9.9a–c show that this theme is adumbrated in the second movement as a first-theme continuation (beginning bar 17), finds two variants in the fourth movement (prime form and diminution) and resurfaces in the Finale as the substance of its transitions and development, subsequently combined with the movement’s first theme, in diminution, in the development. This line of thematic action culminates in the standing on V that supplies the transition to the coda in bars 271–398 (Example 9.9d), above which Schumann stacks up ‘x’ in stretto in bars 271–9. The motive’s final appearance coincides with the pre-dominant approach to the crucial cadence in bars 394–8, and comprises two augmented versions of its central segment, as Example 9.9d explains. After this, ‘x’ is superseded seamlessly by the first-movement main-theme variant; the exhaustion of a thematic process spanning three movements clears the ground for the return and resolution of the first movement’s problematic main subject.18

Example 9.9a Schumann, Symphony No. 3, II, bars 16–18.

Example 9.9b Schumann, Symphony No. 3, IV, bars 1–8.

Example 9.9c Schumann, Symphony No. 3, V, bars 97–9.

Example 9.9d Schumann, Symphony No. 3, V, bars 271–9.

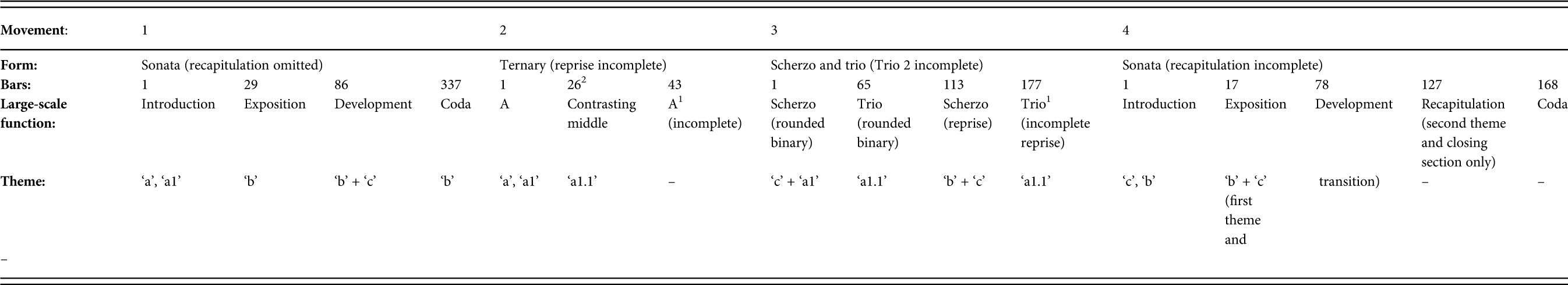

Schumann’s most extensive experiment with cyclic integration appears in the Symphony No. 4 (his second by order of genesis, but last in order of publication, having been revised in 1851). The recurrence and variation of themes between movements in this work is linked to a radical formal strategy, through which movements are made continuous by elision and co-dependent by formal truncation. Thus each movement references a common fund of ideas, which expands across the work. Simultaneously, the four movements are all in some respect formally incomplete: the first movement comprises a compact sonata form with slow introduction, in which the end of the development bypasses the recapitulation and proceeds directly to the coda; the ternary slow movement abbreviates its A1 section; the Scherzo sets up the expectation of an A–B–A1–B1–A2 design, which is discontinued towards the end of B1; and the Finale is conjoined with the Scherzo by means of a slow transition, and then truncated through the omission of the first-theme reprise.

The reduction of each movement’s formal independence is compensated by a network of thematic transformations, which supplies the impression that formal threads left incomplete within movements are fulfilled between them. The important material is summarised in Example 9.10; its disposition across the work is appraised in Table 9.2. The progress of the material is as follows: the principal idea of the slow introduction, marked ‘a’, recurs as a subsidiary idea in the A section of the slow movement. The first movement’s main theme (‘b’), which is also its subordinate theme, forms a counterpoint to the main theme of the Finale. The Finale’s first theme is, moreover, a variant of the new ‘breakthrough’ idea introduced from bar 121 of the first movement (‘c’). This theme also forms the basis of the Scherzo’s principal subject, presented in combination with motive ‘a’ from the introduction, which is inverted and played imitatively between the violins and lower strings. And the Trio is a wholesale recomposition of the slow movement’s B section, itself a variant of ‘a’.

Example 9.10 Schumann, Symphony No. 4, cyclical relationships.

Table 9.2 Schumann, Symphony No. 4, movement scheme, forms and thematic relationships

The density of cross-referencing in Symphony No. 4, coupled with its high degree of strategic formal loosening, reflects a notion of symphonism that is quite different from that embodied in the First, Second and Third symphonies, a distinctiveness underscored by Schumann’s original intention to call the work a symphonic fantasy.19 Whereas in the other symphonies cyclical methods tighten the multi-movement design, in the Fourth Symphony they compensate for its collapse, a technique that brings Schumann to the edge of ‘two-dimensional form’, the merging of form and cycle that Steven Vande Moortele explores in Chapter 11.

Whether we accept Dahlhaus’s association of Liszt with the so-called mid-century ‘dead time’ of the symphony or not (and David Brodbeck’s chapter in this volume gives us good grounds for being suspicious of Dahlhaus’s model), the modernism of Liszt’s contribution to the field is hard to contest. This is founded on two technical innovations: ‘two-dimensional’ form; and cyclical transformation. These two strategies are intimately related: the coherence of Liszt’s forms in his symphonic poems is secured by the method of integrating the diverse characters of the implicit movement types as transformations of a small repertoire of themes.

The relationship between form and cyclical transformation, however, has to be rethought when we turn to Liszt’s multi-movement works retaining the designation ‘symphony’, not least because they have distinct generic ancestry: the symphonic poems draw on the early-century tradition of the concert overture, notably as practised by Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Schumann; Eine Faust-Symphonie and the Dante Symphony are characteristic symphonies in the line of Beethoven’s Pastoral and numerous mid-century examples by Spohr, Raff, Rubinstein, Gade and others. The technique has the same extra-musical function in both cases (a poetic or literary idea is served by a theme’s potential for taking on different identities) but antithetical structural functions (in the symphonic poems, thematic transformation supports the impression of multiple movements in a single-movement form; in Eine Faust-Symphonie, transformation supports the impression of a single overarching design in a multi-movement scheme).

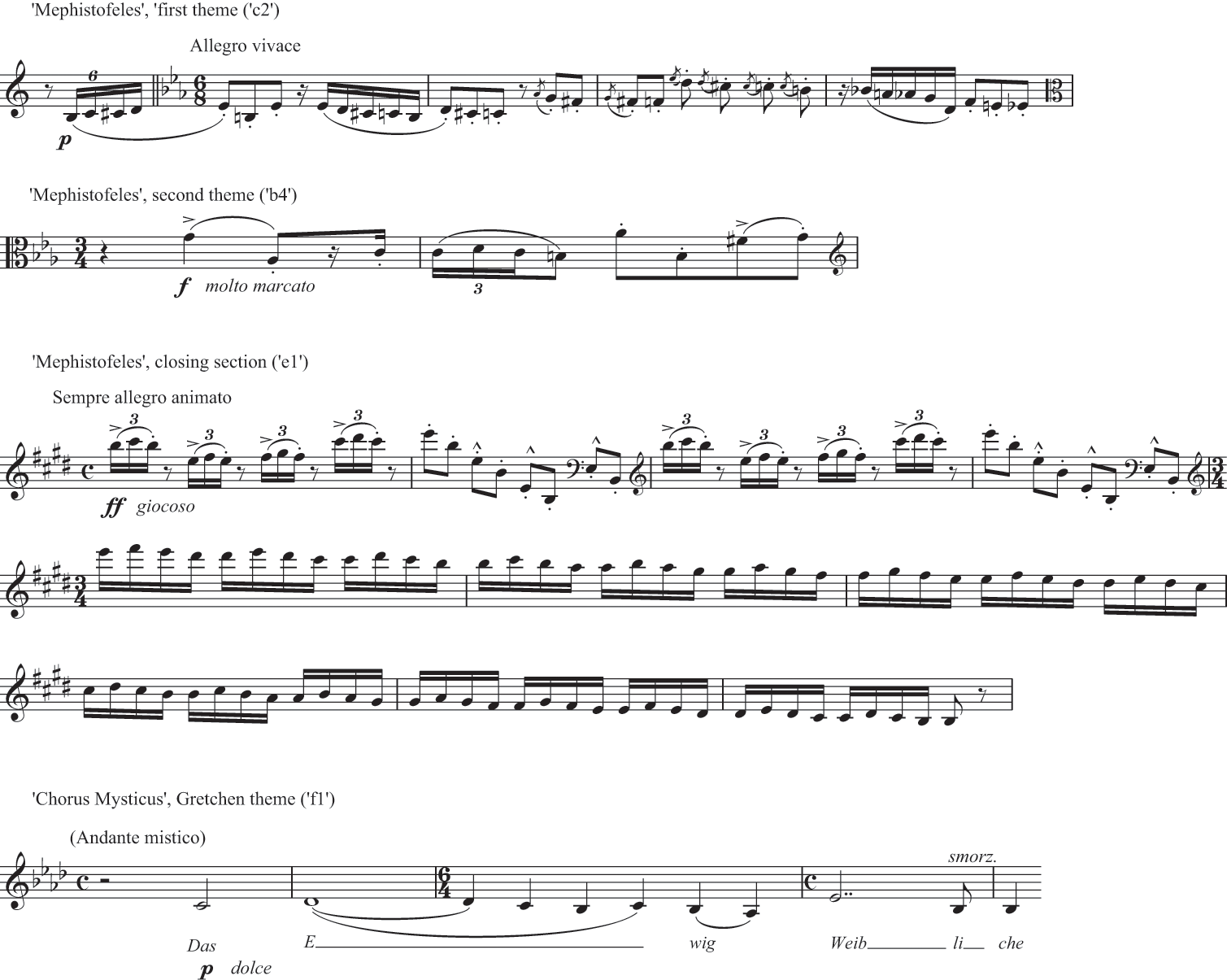

Eine Faust-Symphonie is by far Liszt’s most substantial essay in this technique. As numerous commentators have observed, its various cyclical relationships dramatise four basic extra-musical elements: the personality of Faust himself (in the first movement); Mephistopheles as a ‘negative’ image of this personality (in the Finale); Faust’s relationship with Gretchen (in the slow movement); and Faust’s love for Gretchen as the means of his redemption (in the Finale’s vocal coda, the famous Chorus mysticus).20 The disposition of themes, a conspectus of which is offered in Example 9.11, reflects this. The three main subjects of the first movement’s exposition embody three personality facets – tragic, amorous and heroic – which are viciously parodied in the Finale at analogous formal locations. Around this scheme, Liszt also works the ‘alchemical’ theme with which the Symphony begins, the whole-tone and hexatonic ambiguities of which invoke Faust’s scientific ambitions. This is also given a sardonic twist in the Finale’s introduction: the quest for knowledge is mocked as hubristic and egomaniacal.

Example 9.11 Liszt, Eine Faust-Symphonie, cyclical relationships.

Faust’s dialogue with Gretchen centres on the slow movement’s contrasting middle section, which from four bars after Letter J develops an urgent, recitative-like variant of the first movement’s second theme. This cements the dual perspective engendered in the relationship between first and second movements: Gretchen is viewed from Faust’s perspective; and Faust from Gretchen’s perspective. In the Finale, Liszt finds his crucial arbiter of resolution in an inversion of the idea guiding the Finale of Schumann’s Symphony No. 2. Whereas Schumann fulfils his work’s dramatic aspirations through the transformation of an instrumental image of the ‘distant beloved’ into a kind of wordless secular chorale, Liszt reveals the drama’s redemptive message at the end by setting the crucial words ‘das ewig Weibliche zieht uns hinan’ (‘the eternal feminine leads us beyond’) to Gretchen’s main theme (at Letter B). Both finales instantiate the problem of following Beethoven’s Ninth, but offer opposed solutions: Schumann summons Beethoven directly (An die ferne Geliebte), but sublimates the overt vocality of the Ninth’s Finale into an instrumental finale that can do comparable extra-musical work in a wordless context; Liszt brings two Beethovenian precedents – the ‘Pastoral’ and the Ninth – into direct contact, by writing a characteristic symphony, which concludes with a redemptive vocal apotheosis.

Austria and Russia: Bruckner and Tchaikovsky

The ideological battles fought over the symphony in the wake of the Lisztian symphonic poem and Wagnerian music drama are keenly reflected in debates about thematic technique. Wagner’s critique of Brahms’s symphonies pivoted on their thematic aspects: when Wagner likened their material to particles of ‘chopped straw’, which had been removed from their proper chamber-musical home and given inappropriate symphonic housing, he reinforced critically the conviction that symphonism reliant on Beethovenian thematicism was moribund.21 At the same time, Brahmsian partisans elevated precisely these properties as vital guarantors of coherence. Max Kalbeck’s complaint that Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7, a work that became something of a cause célèbre of post-Wagnerian symphonism, evinced the composer’s ‘absolute inability . . . to think and act according to the laws of musical logic’ invoked a benchmark of thematicism, in relation to which Bruckner was perceived to fall some way short.22The dispute between the ‘Kuchkists’ and the conservatoire-based ‘Germanic’ conservatives in Russia mobilised similar tensions.23 The ‘Mighty Handful’ marshalled concepts of national authenticity as justification for breaking with teutonic norms, whilst at the same time relying on those norms as inescapable markers of generic identity. In the territory of the symphony, these controversies fostered works by Balakirev and Borodin on the one hand, and by Anton Rubinstein and Tchaikovsky on the other, all of which wrestle with the problem of how to maintain large-scale symphonic integrity whilst finding a constructive alternative to the Brahmsian method of cellular development.24

The symphonies of Bruckner and Tchaikovsky offer an instructive pairing in this regard, not only because they seem, at face value, to exemplify thematic strategies on the ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ of the Austro-German tradition, but also because both have, in their own ways, found themselves on the wrong side of attempts to establish what is normative for post-Beethovenian symphonism. As a result, whilst Tchaikovsky could be construed as a symphonist on the margins of a tradition centred on Austria and Germany, Bruckner has been regarded as an outsider in his own cultural context, an Austrian symphonist who shuns Austro-German classic–romantic orthodoxy.

These perceptions are concisely enunciated in Carl Dahlhaus’s commentary on the two composers, which deploys the comparison as a point of entry into the issues surrounding the ‘second age’ of the symphony:

The difficulties that beset large-scale instrumental music under the premises of ‘late romanticism’ are to be discovered not so much in Bruckner, who seems to have been born to monumentality and then transplanted into the alien and unsympathetic world of the nineteenth century, as in Tchaikovsky, whose irresistable rise as a symphonist should not obscure the fact that he was primarily a composer of operas and ballets.25

For Dahlhaus, Tchaikovsky’s theatrical proclivities constrained his symphonic ambitions. In the Symphony No. 4, this is manifest in the relationship between the first movement’s main theme and the ‘fate’ motto with which the introduction begins. Singling out the latter’s appearance at the development’s climax, Dahlhaus argues that the movement is flawed because both motto and main subject are incompatible with their formal roles: the motto is ‘not amenable to development’, but is nevertheless made to serve that function; and the first subject’s lyric character renders it ‘hardly suitable . . . for establishing a symphonic movement spanning hundreds of measures’. In sum, ‘the grand style fundamental to the genre has been split into a monumentality that remains a decorative façade unsupported by the internal form of the movement, and an internal form that is lyrical in character and can be dramatized only by applying a thick layer of pathos’.26 The root of the problem is the mistaken belief that a lyrical melody can underpin a monumental symphonism that is Beethovenian in aspiration.27

Bruckner’s otherness resides not in the vocality of his style, but in the relationship between pitch and rhythm as motivic parameters. As Dahlhaus explains:

Musical logic, the ‘developing variation’ of musical ideas . . . rested on a premise considered so self-evident as to be beneath mention: that the central parameter of art music is its ‘diastematic’, or pitch, structure . . . Bruckner’s symphonic style, however . . . is primarily rhythmic rather than diastematic, and thus seems to stand the usual hierarchy of tonal properties on its head.28

In the Sixth Symphony, Dahlhaus locates the foundations of the first movement’s themes in their rhythmic character; the diversity of thematic variants arises not from a systematic manipulation of interval content, but from the free alteration of pitch and interval around an invariant rhythmic pattern. In contrast to the apparent superficiality of Tchaikovsky’s monumental idiom, Bruckner’s technique rested for Dahlhaus on the integration of a ‘block’ formal architecture through ‘a system of approximate correspondences’, which ‘enables monumentality to appear as grand style’.29

Both these readings can be challenged. Leaving aside the covert prejudice which caused Dahlhaus to withold credibility from almost every non-German symphony he investigated (Franck’s Symphony in D minor and Saint-Saëns’s ‘Organ’ Symphony are also deemed to ‘fail’, in the latter case for reasons that are strikingly similar to those discovered in Tchaikovsky), Dahlhaus is remiss in considering the precedents for Tchaikovsky’s style and the details of both composers’ thematic strategies. Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4 exhibits manifold debts to earlier works in the Austro-German lineage, especially Schumann’s symphonies (and ultimately Schubert, as Chapter 4 identifies): the first movement of the Symphony No. 4 in particular gives the impression of a wholesale misreading of the first movement of Schumann’s Symphony No. 2. And Bruckner’s focus on rhythm as a binding agent in the Symphony No. 6 has plentiful antecedents in the Beethovenian mainstream: in the first movement of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, for example, the foundations of motivic coherence are as much rhythmic as they are intervallic, as any attempt to analyse the first theme and transition will quickly establish, and as Mark Anson-Cartwright has clarified above.

In general, Tchaikovsky’s Fourth and Fifth symphonies can be grouped together not on chronological grounds (they are separated by some ten years), but because they share a preoccupation with cyclical thematicism, which is more developed than any connections that might be unearthed in symphonies nos. 1–3 or 6. Symphony No. 5 is the more ambitious of the two, pursuing the implications of the first movement’s introductory material across its four movements. Symphony No. 4 applies the same idea in a more restricted sense, working the introductory motto into the fabric of the first movement’s sonata form and reprising it climactically in the Finale. Both symphonies, moreover, make their cyclical materials do similar programmatic work, since in both cases Tchaikovsky associated his introductory motto with the agency of fate.30

Symphony No. 4’s design is indebted to Schumann’s first two symphonies in two key respects. In the first place, Tchaikovsky honours both of these precedents in presenting significant material (the ‘fate’ motive ‘x’ shown in Example 9.12) in advance of the main body of the first movement’s sonata design, which is then extensively worked into it, thanks to the motive’s interjections at the end of the exposition and recapitulation (bars 193 and 355 respectively), its substantial presence in the development and reliance on its second half as the basis of the coda (beginning in augmentation at bar 366).

Example 9.12 Tchaikovsky, Symphony No. 4, I, bars 1–6.

Moreover, like Schumann’s Symphony No. 2, Tchaikovsky’s No. 4 explores the idea that a thread of developmental activity from the first movement should meld, in its Finale, with one initiated in the inner movements, although the process is rather more involved in Schumann’s case. Specifically, Tchaikovsky’s second, third and fourth movements are related by virtue of a common thematic incipit, which as Example 9.13 makes clear is in all cases a descending tetrachord, marked ‘y’.

Example 9.13 Tchaikovsky, Symphony No. 4, II, III and IV, thematic connections.

The relationship between ‘x’ and ‘y’ is, however, successive rather than integrative: if ‘y’ links movements as a common Hauptmotiv, then ‘x’ recurs as a ‘breakthrough’ event at bar 199 of the Finale, which impedes progress towards the coda through wholesale recall of the first movement’s introduction. No attempt is made to synthesise these threads: instead, the first-movement reprise functions as a moment of retrospection – a memory of fate’s negative associations – which drains away in advance of the Symphony’s festive conclusion.

In the Symphony No. 5, the authority of the motto theme (labelled ‘x’ in Example 9.14) seems, initially, to be more restricted, since after the slow introduction, its influence is suspended for the entirety of the first movement. Thereafter, however, its incursions are regular, and its involvement in the Finale especially is more substantial and more synthetically minded than in the Symphony No. 4. In the slow movement, ‘x’’s function is disruptive, derailing the progress of the music’s ternary form at two junctures, quoted in Example 9.14: first, in bars 99–107, where it frustrates any smooth retransition to the A1 section, placing that burden on the pre-thematic material of the reprise (bars 108–110); second, in bars 158–69, where it intervenes between the movement’s final structural dominant and the coda, which sits entirely above a tonic pedal.

Example 9.14a–e Tchaikovsky, Symphony No. 5, cyclical use of motto theme.

The second intervention is more assertively dissonant than the first: bar 99 brushes aside a four-bar standing on V of C-sharp minor with a diminished third chord, which is then reinterpreted as ![]() in the movement’s tonic (D major); bar 158 disturbs A1’s final perfect cadence with ♯viidim.7/V, from which progression to I is salvaged by the assertion of iv6 in bar 164.

in the movement’s tonic (D major); bar 158 disturbs A1’s final perfect cadence with ♯viidim.7/V, from which progression to I is salvaged by the assertion of iv6 in bar 164.

The slow movement’s success in holding back the influence of the ‘fate’ motto yields expressive dividends thereafter. In the third movement, ‘x’ makes only one appearance, in the coda, where it emerges in a quiet, post-cadential waltz variant (beginning bar 241; see Example 9.14d). And by the time of the Finale, the motto’s function has effectively been reversed: rather than disturbing the form’s progress, it offers a major-mode, introductory antidote to the tempestuous main theme (Example 9.14e quotes its introduction form). As well as supplying the substance of the introduction and the triumphant (but by some accounts shallow) martial coda, ‘x’ makes two critical and formally analogous appearances in the movement’s interior.31 In the exposition’s closing section, it is instrumental in the (ultimately problematic) attempt to secure C major as the closing key (bars 172–201). In the recapitulation, this event is offset by an arduous liquidation of ‘x’ over V of E minor beginning at bar 426, which eventually emerges onto the half close prefacing the coda.

For Tchaikovsky, cyclical relationships have fairly specific extra-musical connotations, which are held in common between the two works in which he applies them most extensively; indeed, the use of such devices in these symphonies suggests a close affiliation in Tchaikovsky’s mind between cyclical thematicism and symphonic engagement with the struggle between fate and the heroic subject. For Bruckner, cyclical technique is somewhat more expressively variegated. It is a persisting, but by no means progressively evolving, strategy from the Symphony No. 2 (1872, revised 1877) onwards, being prominent in the Third, Fourth and Seventh symphonies, and most substantially represented in the Fifth and Eighth symphonies (the Ninth, being unfinished at the time of the composer’s death, remains to an extent a moot point in this regard, given that the Finale’s ultimate design remains a matter of speculation).32

Bruckner’s most comprehensive cyclical exercise is undoubtedly the Symphony No. 5. On the largest scale, Bruckner conceives a symmetrical movement scheme, underscored by tonality, outlined in Figure 9.1.

Figure 9.1 Bruckner, Symphony No. 5, pairing of inner and outer movements by theme and key

In addition to their shared tonality, the outer movements are related by three means. The most explicit devices are the literal recall of the first movement’s introduction as the introduction to the Finale, which generates the impression that both movements proceed as contrasted responses to the same starting point, and the brief, parenthetical allusion to the first movement’s main theme in bars 13–22 , which is part of a chain of prior-movement quotations directly referencing the Finale of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. In addition, the Finale’s principal subject shares harmonic properties with that of the first movement; specifically, its ♭II inflection mirrors the ♭VI tendency of the first-movement theme (see Example 9.15). Lastly, the first movement’s main theme is reprised in the recapitulation’s expanded third-theme group, initially at bar 462; indeed, this part of the form is enlarged specifically to accommodate further developmental activity centred on the theme’s recovery.

Example 9.15 Bruckner, Symphony No. 5, mvts I and IV, first themes.

The harmonic similarity of the outer-movement main themes underpins a more direct connection, which cements their relationship: in bars 522–5, the two themes are combined, prefigured by the combination of their head motives from bar 518, shown in Example 9.16. This event draws the themes into an overarching harmonic process, since their chromatic inflections have a critical impact on both movements’ tonal schemes. It also provides a cyclical rationale for the Finale’s form, which is a complex mixture of sonata and double fugue. The first-theme group is a martial fugue; the development comprises two fugues, the first on the important chorale theme introduced at the end of the exposition (bar 175, fugue commencing bar 223), the second combining this theme with the first subject (from bar 270). Although the chorale is never directly combined with the first movement’s main theme, the fact that the chorale combines with the Finale main theme sets up a threefold thematic relationship that binds the outer movements, through the sharing of harmonic properties.33

Example 9.16 Bruckner, Symphony No. 5, IV, bars 522–5.

Bruckner’s long-range strategies here address a broader metaphysical agenda than Tchaikovsky’s confrontation between fate and human agency. In the Symphony No. 5 more directly than in any other of his symphonies, Bruckner dramatises the struggle between the secular and the sacred, embodied in a system of topical contrasts, which are indivisible from the work’s thematic action. As their martial themes convey, the protagonist of the outer movements is a heroic, secular individual in the Beethovenian sense, a shared agency that the Finale reinforces by contrapuntal combination. The Finale’s double fugue seeks reconciliation of this subject with a sacred topic, embodied in the chorale theme; the exhaustive working out of the contrapuntal possibilities of these two themes in the development signifies an effort to reconcile their opposed topics. The chorale’s magisterial entry as the climax of the coda in bar 583 performs two key functions in this respect. As a generic device, it turns the coda into a chorale prelude, thereby subsuming prior thematic–topical conflicts into a form that gives the sacred material centre stage. As a tonal event, it initiates a final composing out of the chromatic inflections that characterise first- and last-movement main themes: both first and second strains begin on flat-side chromatic regions (C flat and G flat) and work their way towards the tonic and its close relations, eventually emerging into the decisive tonic perfect cadence in bars 610–14. The residues of the first-movement theme persisting in the aftermath of this event and forming the substance of the Symphony’s final gesture are notably diatonic, as if the reconciliation of the work’s thematic, topical and tonal conflicts in its culminating assertion of faith has at last purged the material of its secular uncertainties.

While the outer movements play out their monumental thematic, contrapuntal and tonal drama in the tonic, the Adagio and Scherzo unfold internal relationships grounded in D minor, which interrupt the process that surrounds them. Examples 9.17a and b clarify the relationship.

Example 9.17a Bruckner, Symphony No. 5, II, bars 5–8.

The string accompaniment with which the Adagio begins, marked ‘a’, forms a near-ubiquitous feature of the Scherzo. Example 9.17b shows one of its many subtle uses: the Ländler comprising the subordinate theme, beginning at bar 23, is built on a decelerated variant of ‘a’ transferred into the bass, which persists for the entirety of this material’s presentation. And as Example 9.17a shows, the Scherzo’s main theme, which is counterpointed against ‘a’, is a variant of the oboe theme with which the Adagio begins. The heroic cyclical drama played out by the outer movements is thereby offset by an interior drama grounded in an attempt to transform the Adagio’s mournful processional into a more dynamic alternation of dance styles.

Example 9.17b Bruckner, Symphony No. 5, III, bars 1–8 and 23–30.

Fin-de-siècle: Mahler

In all the works considered thus far, cyclical devices act in the interests of large-scale coherence: that is, they respond to the problem of how to apply thematic techniques as a means of binding disparate movements, whilst invariably conveying an extra-musical message. Yet although Mahler absorbed these precedents thoroughly, he also applied them in ways that sometimes seem to critique the ideal of integration they serve. Whilst all of his nine completed symphonies operate some kind of inter-movement thematicism, it frequently contributes to a kind of collage effect, which questions the notion of inter-movement unification even as it references its guiding method.

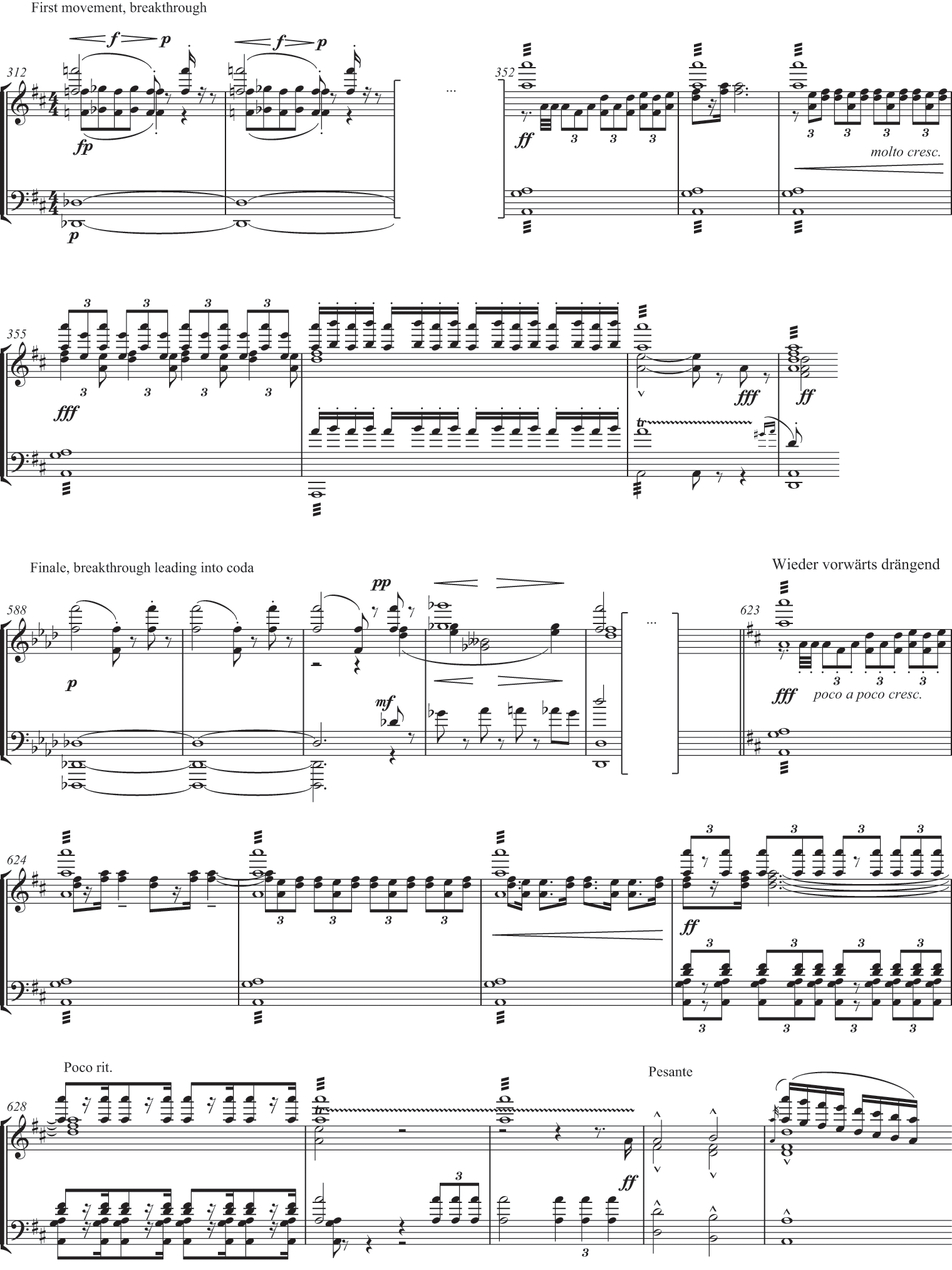

Brief comparison of the First and Second symphonies, and a postscript on the Symphony No. 9, serve to introduce Mahler’s complex, eliptical approach to cyclical technique. As is well known, the First and Second symphonies form a pair, insomuch as Mahler imagined the latter as narrating the death and resurrection of the heroic subject embodied in the former.34 The ideal of transcendent integration is most closely emulated in the Symphony No. 1, in which Mahler exploits three crucial inter-movement connections: the primordial music of the Symphony’s introduction (Example 9.18a) is transformed as the work’s triumphant goal; the main theme of the Finale is a wholesale minor-mode recomposition of the first movement’s development material (Example 9.18b); and the ‘breakthrough’ music of the first movement’s climax returns in the Finale, initially in the development and conclusively in the coda (Example 9.18c shows the breakthrough and its return before the Finale’s coda).35

Example 9.18a Mahler, Symphony No. 1, I, bars 7–9 and IV, bars 652–6.

Example 9.18b Mahler, Symphony No. 1, I and IV, thematic relationships.

Example 9.18c Mahler, Symphony No. 1, I, bars 312–58 and IV, bars 588–632.

These three devices are closely related: the second and third are in effect enabling precursors of the first. The introduction’s primal descending-fourth motive recurs in the Finale as a triumphant continuation of the reprised ‘breakthrough’ event, which is additionally changed through the inclusion of a major version of the Finale’s main theme at the breakthrough’s apex. As a result, two ideas, which are separate in the first movement (the introduction theme and the breakthrough) are knitted together. The prematurity of the first version of this event, in the Finale’s development (from bar 370), is signalled by means of an abrupt harmonic shift from C to D, which sunders the breakthrough from its continuation; in the coda (from bar 631), by contrast, all of the material is grounded in the global tonic D major. The transformation of the first movement’s nature music and its conjunction with the Finale’s theme is rich in extra-musical significance. The conversion of an idea initially associated with a nature that is anterior to the first movement’s thematic subject into one that ensues from a major-key variant of the Finale’s pathetic main theme installs nature as the redeeming agent of the Symphony’s heroic subject.

Mahler also employs the wholesale reprise of passages in the Symphony No. 2, but their function here is more elusive. There are two clear instances. The Scherzo’s climactic event (bars 465–81) is retrieved as the opening gesture of the Finale, thereby parenthesising the vocal fourth movement; and aspects of this music also recur in the climax preceding the Finale’s depiction of the last trumpet (bars 402–17). Dovetailed with this is a larger retrieval: the tumultuous martial music leading into the first movement’s retransition gradually emerges out of the Finale’s central episode (first movement, bars 282–94; Finale, bars 301–23). Such recurrences mark their formal locations as dramatically disruptive and therefore expressively significant; but they do not project thematic continuities of the sort explored by Schumann and Bruckner.

Otherwise, thematic connections between the outer movements rely principally on a shared preoccupation with chant-like music, and especially with variants of the Dies irae, which first surfaces in the first movement’s development section at bar 270 (a selection of relationships is given in examples 9.19a, b and c).

Example 9.19a Mahler, Symphony No. 2, I, bars 270–7.

Example 9.19b Mahler, Symphony No. 2, V, bars 62–73.

Example 9.19c Mahler, Symphony No. 2, V, bars 210–11, 216–17, 220–1, 230–3 and 472–4.

The Dies irae is significant, because in the Finale it makes a critical transition from an idea that is incidental to the structural discourse to one that is formally central. The form of the Finale evades simple description. It is probably best regarded as sui generis, comprising four large parts (bars 1–42, 43–193, 194–471 and 472–764), the first constituting the introduction, the last the multi-part Schlußchor. Parts one, two and four also have a sectional, tableaux-like design; part three initially resembles a sonata form, but this impression disintegrates as the music proceeds. From bar 62, Mahler engineers a thematic conjunction that has central programmatic significance. The Dies irae initiates a phrase, which a minor-key adumbration of the Schlußchor’s ‘Aufersteh’n’ theme concludes (from bar 70). In the Schlußchor, the latter takes centre stage, whilst the former is jettisoned. The hermeneutic implication is clear: the progress of the material embodies the Symphony’s expressive trajectory, from death and judgement to resurrection.

Even more hermeneutically suggestive are the relationships between the Finale and the fourth movement, a setting of ‘Urlicht’ (‘Primal Light’) from Des Knaben Wunderhorn. The crucial material here is the music first introduced to set the words ‘Je lieber möcht’ ich im Himmel sein’ (‘I would rather be in heaven’) in bars 22–30, which supplies the last vocal phrase in the movement’s A section (Example 9.20). Critically, Mahler illustrates that this is an as yet unfulfilled aspiration by leaving the singer’s phrase cadentially unresolved over IV9–8, it being left to the the oboist to supply perfect-cadential closure. The same material serves simultaneously as the climax of the middle section and as an elided, truncated reprise from bar 58, now given added expressive weight through the addition of a pungent ♭VI chord in bar 60. Here, moreover, Mahler allows the vocalist to carry the phrase through to its cadential conclusion, thus underlining the fact that the material now sets the more assured lines ‘Der liebe Gott wird mir ein Lichtchen geben / Wird leuchten mir bis das ewig, selig Leben’ (‘Dear God will give me a little light / Will light my way to eternal, blessed life’).36

Example 9.20 Mahler, Symphony No. 2, IV, bars 22–30.

Mahler retrieves this music at an important juncture (bars 655–72) in the Finale’s Schlußchor on the text of Klopstock’s Auferstehung, to which Mahler added his own additional stanzas. Here, he sets his own words ‘Mit Flügeln die ich mir errugen / In heißem Liebestreben / Werd’ ich entschweben zum Licht / Zu dein kein Aug’ gedrungen’ (‘With wings I have acquired / Shall I soar / In love’s ardent striving / To the light to which no eye has penetrated’),37 in so doing revealing a key strategic motivation behind the extension of Klopstock’s poem. In ‘Urlicht’, both instances of this music set aspirations towards resurrection in eternity, the second more certain in its conviction than the first. In extending Klopstock’s text, Mahler in effect uses it as a platform for recovering and fulfilling ‘Urlicht’’s metaphysical ambition: Klopstock’s assertion that ‘you will rise again’ (‘Aufersteh’n, ja aufersteh’n wirst du’) is related by Mahler’s text to ‘Urlicht’’s light that will lead ‘to eternal, blessed life’.

Although strategically related, these three cyclical threads are not integrated. The first is a quasi-cinematic gesture embodying the rhetoric of crisis, which jolts the music out of its local continuity at strategic formal locations. The second has tangible programmatic significance: a chant signifying the day of judgement is conjoined with a theme connoting resurrection. And the third conveys the agency of that resurrection (the light that leads to eternity). There is, however, no grand synthesis in the manner of Bruckner’s Fifth Symphony. Rather, Mahler embeds strands of cyclical discourse within a symphonic context that values expressive fecundity as much as rigorous thematicism. Mahler’s symphonic ‘world’ is a master-genre that can absorb diverse generic and expressive sources (in this case symphony, lied and cantata), in which context thematic cross-referencing principally guarantees narrative orientation rather than any sense of overarching unity.

In the Symphony No. 9, the Scherzo, Rondo burlesque and Adagio are related by two principal means: first, by variation of the descending melodic line and harmonic progression which appears initially in the Scherzo’s first waltz episode (bar 90, with the characteristic motion towards ♮VI from bar 96), reprised as a complete hexatonic progression from bar 261, and which references Beethoven’s Lebewohl Sonata, Op. 81a (Example 9.21, marked ‘a’);38 and second, through retention in the Adagio of the turn motive first introduced in bar 320 of the Rondo burlesque (Example 9.21, marked ‘b’).

Example 9.21 Mahler, Symphony No. 9, thematic relationships between mvts II, III and IV.

There are several ways of understanding these connections. One solution is to regard the Adagio’s refrain as uniting previously disparate material. By this reading, the movement begins with a synthetic event: the Lebewohl motive, labelled ‘a’, constitutes its head motive; the turn, labelled ‘b’, is a subsidiary idea, which consistently saturates the texture in both prime form and augmentation. This interpretation is reinforced by topical considerations. Motive ‘a’ supports a topical trajectory, in which material portrayed as a waltz in the Scherzo becomes a polka in the Burlesque (second theme, bar 266) and finally a hymn in the Adagio: an idea given a secular identity earlier in the work thereby reveals its spiritual core in the last movement. An alternative reading would see the Adagio’s refrain not as a thematic prime form, towards which the earlier cyclical threads have been working, but rather as a final presentation of ideas that will gradually lose their syntactic cohesion as the movement progresses. In these terms, the two material threads are continuities, initiated earlier in the Symphony, which run through the Adagio’s theme and on to its final bars.

The subsequent processes acting on this music have to be contextualised within the Adagio’s design, which can be construed as a loose five-part rondo with coda, in which the refrain becomes successively more elaborate, and as a result more texturally and harmonically diffuse. Mahler exploits the rondo form not as a means of grounding the main theme through recursion, but as a vehicle for the successive questioning of its structural integrity. In A1 (beginning bar 49), the refrain is elaborated with increasingly dense chromatic counterpoint which threatens to obscure its syntactic outline, yielding from bar 73 to a cadential phrase and codetta, which draws out the act of local closure to a point of virtual stasis. A2, located as the Adagio’s major climax (bar 127), begins with even more densely worked textural elaboration in which the turn figure is counterpointed in diminished form against ‘a’, but this successively thins out as the coda approaches. And the coda itself dwells on ‘b’, elements of the movement’s incipit, and the refrain’s continuation material presented for the first time from bar 13, simultaneously fragmenting and decelerating until, by the end, only the turn remains.

Narratives of farewell are pervasive in the discourse on this music, as on the work as a whole.39As Vera Micznik has shown, such readings are not unproblematic, especially if they are read as autobiographical.40 Yet it is hard to ignore the cultural baggage attending this Symphony, and its expressive implications for the material process with which the work concludes. The gradual disappearing from view that Mahler engineers has a fourfold implication. In the context of the Adagio, it supplies a protracted, attenuated liquidation of the movement’s primary material. In the context of the Symphony, this is also a dissolution of the cyclical impulse, because the endlessly drawn-out thematic fragmentation invokes a material thread tracking back to the Scherzo. As Mahler’s last completed symphony, this dissolution also signifies the exhaustion of the impulse motivating his entire symphonic project (although the extensive materials for Symphony No. 10 complicate this perception). And on the largest scale, it constitutes nothing less than an aural symbol of a symphonic tradition, and the idealism it embodied, fading into history: the ardent utopianism of the Beethovenian symphony, galvanised by the realisation that autonomous musical relationships can convey poetic, literary or metaphysical aspirations, finds its point of ultimate repose. The cultural ‘slipping away’ (‘das Gleitende’) that Hugo von Hoffmansthal diagnosed in the years preceding the First World War is nowhere more poignantly expressed.41

Notes

1 This conversation has been reported numerous times. For an early example, see , Jean Sibelius: His Life and Personality, trans. (New York, 1938), 191; for recent commentary, see , The Oxford History of Western Music, vol. III: Music in the Nineteenth Century (New York and Oxford, 2005), 822.

2 On this matter, see for instance , After Beethoven: Imperatives of Originality in the Symphony (Cambridge, Mass., 1996), esp. 21.

3 For a cogent appraisal of the dialectical relationship between the absolute and the programmatic, see , Programming the Absolute: Nineteenth-Century German Music and the Hermeneutics of the Moment (Princeton, 2002), 1–4.

4 See , Haydn’s ‘Farewell’ Symphony and the Idea of Classical Style: Through-Composition and Cyclic Integration in His Instrumental Music (Cambridge, 1991), esp. chapter 6.

5 The literature on what this means is of course substantial. For recent commentary on this passage and its reception, see for instance , Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 (Cambridge, 1993), 86–90, , Beethoven: The Ninth Symphony (New Haven, 2003), 103, and , ‘Not “Which” Tones? The Crux of Beethoven’s Ninth’, 19th-Century Music, 22/1 (1998), 61–77. The idea that the baritone’s words reject the notion of an instrumental finale is expressed succinctly by Lewis Lockwood: ‘The baritone, as if stepping outside the picture frame, in effect addresses the other singers, soloist and chorus, and beckons them to join in what now must be not just a symphonic finale but a specifically vocal celebration of joy and brotherhood. He rejects . . . the whole idea of the orchestral exposition of the main theme.’ See Beethoven: The Music and the Life (New York, 2003), 434–5. Levy, by contrast, insists that the baritone rejects only the returning Schreckensfanfare drawn from the Finale’s opening.

6 On the tonal relationship between the first movement’s subordinate theme and the Adagio, see for example Lockwood, Beethoven: The Music and the Life, 431.

7 Cyclical devices are more strongly employed by Beethoven in other genres. The late ‘Galitzin’ Quartets are a good example, on which subject see , The ‘Galitzin’ Quartets of Beethoven (Princeton, 1995).

8 Berlioz’s two programmes are reproduced in , ed., Berlioz: Fantastic Symphony (New York and London, 1971), 22–5 and 30–5. The idea that the music’s formal scheme should embody metaphorically the ‘mental processes of the symphony’s beleaguered protagonist’ is taken up by Stephen Rodgers; see Form, Program, and Metaphor in the Music of Berlioz (Cambridge, 2009), 85–106, this quotation 90.

9 The material integrity of the Symphonie has been addressed seminally and in some detail by Edward T. Cone; see ‘Schumann Amplified: An Analysis’, in Cone, ed., Berlioz: Fantastic Symphony, 249–79. More recent analyses include , The Music of Berlioz (New York and Oxford, 2001), 251–66 and Rodgers, Form, Program, and Metaphor in the Music of Berlioz.

10 See The Memoirs of Hector Berlioz, trans. and ed. (New York, 1975), 224–5,, Correspondence générale, ed. (Paris, 1983), 184; and also , ‘Sinfonia Anti-Eroica: Berlioz’s Harold en Italie and the Anxiety of Beethoven’s Influence’, Journal of Musicology, 10/4 (1992), 417–63, at 421. This essay formed the basis for Bonds, After Beethoven, chapter 2.

11 See Bonds, ‘Sinfonia Anti-Eroica’, 440–3 and 448–9. Bonds later on invokes Harold Bloom’s concept of misreading in this respect, viewing Harold as a ‘tessera’ or ‘antithetical completion’ of Beethoven’s Ninth. See ibid., 454.

12 See Music as Philosophy: Adorno and Beethoven’s Late Style (Bloomington, 2006), 209.

13 See Robert Schumann, ‘A Symphony by Berlioz’, Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (3 and 31 July, 4, 7, 11 and 14 August Reference Schumann and Bent1835), trans. Edward T. Cone in Berlioz: Fantastic Symphony, 220–48.

14 On Schumann’s discovery of the ‘Great’ C major Symphony in the possession of Schubert’s brother Ferdinand and its subsequent performance at the Leipzig Gewandhaus under Mendelssohn, see , Robert Schumann: Herald of a ‘New Poetic Age’ (Princeton, 1997), 173–4.

15 On this matter, see Daverio, Robert Schumann, 231–2.

16 The Symphony No. 2 is of course also rich in allusion and quotation. As various commentators have pointed out, the motto theme quotes Haydn’s ‘London’ Symphony, No. 104, and there are allusions to Beethoven and Schubert (the ‘Great’ C major Symphony) throughout. Schumann’s reference to the sixth song of Beethoven’s An die ferne Geliebte in the Finale, which he quotes in numerous other works (most famously the Fantasie Op. 17), will be dealt with below. On these matters, see for example , ‘Once More between Absolute and Program Music: Schumann’s Second Symphony’, 19th-Century Music, 7/3 (1984), 233–50; Daverio, Robert Schumann, 317–22.

17 Newcomb sees the movement as a rondo lieto fine, which transforms into a sonata form through the agency of the development. See ‘Once More between Absolute and Program Music’, 245–6.

18 For a consideration of motivic coherence in this coda, see Linda Correll Roesner, ‘Schumann’, in , ed., The Nineteenth-Century Symphony (New York, 1997), 43–77.

19 On the first version of the Symphony No. 4, see Daverio, Robert Schumann, 237–41.

20 For an influential view of the form of the first movement and its thematic content, see , ‘Sonata Form in the Orchestral Works of Liszt: The Revolutionary Reconsidered’, 19th-Century Music, 8/2 (1984), 142–52, and esp. 146–9.

21 Wagner expressed trenchant views on contemporary symphonism, and implicitly that of Brahms; for this quotation, see ‘Über die Anwendung der Musik auf das Drama [1879]’, in Gesammelte Schriften und Dichtungen, 3rd edn (Leipzig, 1887), 183 and also Chapter 4 of the present volume. On Wagner’s concept of the symphonic, see , Wagner Beyond Good and Evil (Berkeley, 2008), chapter 15.

22 See , review of Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7, Die Presse (3 April 1886), trans. in , Anton Bruckner: A Documentary Biography, vol. II: Trial, Tribulation and Triumph in Vienna (Lampeter, 2002), 510.

23 On this dispute, see , Defining Russia Musically (Princeton, 1997), chapter 8, esp. 123–44.

24 On this issue, see Richard Taruskin, The Oxford History of Western Music, vol. III: Music in the Nineteenth Century, 786–801.

25 See , Die Musik des 19. Jahrhunderts (Laaber, 1980), trans. as Nineteenth-Century Music (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989), 266.

26 Ibid.

27 It should, however, be noted that Dahlhaus writes approvingly of a similar division of labour in Schubert’s ‘Unfinished’ Symphony; see Nineteenth-Century Music, 153–4.

28 Ibid., 272.

29 Ibid.

30 On the programmes of the two symphonies, see , Tchaikovsky: The Crisis Years 1874–1878 (London, 1982), 163–7 and Tchaikovsky: The Final Years 1885–1893 (London, 1991), 148–9.

31 Brown, for instance, comments that ‘whereas the Second Symphony’s finale had succeeded splendidly, this one ends in failure, for the pompous parading of the Fate materials requires modest musical ideas to strain after an expressive significance beyond their strength’. See Tchaikovsky: The Final Years 1885–1893, 155.

32 The extant materials for the Finale of the Ninth are extensive, comprising over 200 folios ranging from advanced orchestral drafts to fragmentary sketches. See Anton Bruckner. IX. Symphonie D-moll. Finale. Faksimile-Ausgabe, ed. (Vienna, 1996) . For an overview of the issues surrounding the sources for the Finale of the Ninth, see and , ‘Einführung in die erhaltenen Quellen zum Finale’, in and , eds., Musik-Konzepte 120–2: Bruckners Neunte im Fegerfeuer der Rezeption (Munich, 2003), 11–49.

33 On counterpoint in the Finale of the Symphony No. 5, see, ‘The Symphonic Fugal Finale from Mozart to Bruckner’, Dutch Journal of Music Theory, 11/3 (2006), 230–48 and ‘Counterpoint and Form in the Finale of Bruckner’s Fifth Symphony’, The Bruckner Journal, 15/2 (2011), 19–28. On the tonal implications of the material, see , Bruckner’s Symphonies: Analysis, Reception and Cultural Politics (Cambridge, 2004), 130–5.

34 The programmatic connection between the First and Second symphonies is explained by Mahler in a letter to Max Marschalk, dated 26 March 1896: ‘I called the first movement “Todtenfeier”. It may interest you to know that it is the hero of my D major Symphony who is being borne to his grave, and whose life I reflect, from a higher vantage point, in a clear mirror.’ Mahler concludes: ‘What it comes to, then, is that my Second Symphony grows directly out of the First.’ See Selected Letters of Gustav Mahler, ed. , trans. , and (London, 1979), 180, translation modified. See also , ‘Todtenfeier and the Second Symphony’, in and , eds., The Mahler Companion (New York and Oxford, 1999), 84–125, esp. 123–4, and , ‘Mahler’s “Todtenfeier” and the Problem of Program Music’, 19th-Century Music, 12 (1988), 27–53. Mahler’s programme for the Symphony No. 1 is reproduced in , The Life of Mahler (Cambridge, 1997), 89–90; its formal narrative has been related to that of Jean Paul’s novel Titan in , ‘Narrative Form and Mahler’s Musical Thinking’, Nineteenth-Century Music Review, 8 (2011), 237–54, at 239–46.

35 On the ‘breakthrough’ idea see , Sibelius: Symphony No. 5 (Cambridge, 1993), 6. Hepokoski adopts the term from , Mahler: A Musical Physiognomy, trans. (Chicago, 1992), 41, where Adorno advances it as one of three ‘essential genres in [Mahler’s] idea of form . . . breakthrough (Durchbruch), suspension (Suspension), and fulfilment (Erfüllung)’. Adorno associates breakthrough specifically with the First and Fifth symphonies.

36 For a commentary on the meaning of ‘Urlicht’, see for example Peter Revers, ‘Song and Song-Symphony (I). Des Knaben Wunderhorn and the Second, Third and Fourth Symphonies: Music of Heaven and Earth’, in , ed., The Cambridge Companion to Mahler (Cambridge, 2007), 89–107 and esp. 90–2, and Morten Solvik, ‘The Literary and Philosophical Worlds of Gustav Mahler’, in ibid., 21–34, esp. 31.

37 Klopstock’s poem furnishes only the first two stanzas of the text; Mahler’s text takes over with the line ‘O glaube, mein Herz, o glaube’, corresponding to bar 560 of the Finale.

38 The inter-movement uses of the harmonic progression underpinning this are addressed in , Tonal Coherence in Mahler’s Ninth Symphony (Ann Arbor, 1984), 103–5. Vera Micznik has characterised the first appearance of the progression in the waltz episode of the Scherzo as a distorted variant of a baroque ostinato bass; see ‘Mahler and the “Power of Genre”’, Journal of Musicology, 12/2 (1994), 117–51, esp. 134–5.

39 Early commentators explaining the Symphony No. 9 as Mahler’s ‘farewell to life’ include Richard Specht, Paul Stefan, Alban Berg and Paul Bekker. See , Gustav Mahler (Berlin, 1913), 355–69, , Gustav Mahler: A Study of His Personality and Work, trans. (New York, 1913), for example 142–3, , Briefe an seine Frau (Munich, 1965), 238, and , Gustav Mahlers Symphonien (Tutzing, 1969), 339–40. For a recent example, see Jörg Rothkamm, trans. Jeremy Barham, ‘The Last Works’, in The Cambridge Companion to Mahler, 143–61, esp. 145–6.

40 See , ‘The Farewell Story of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony’, 19th-Century Music, 20/2 (1996), 144–66.

41 ‘[Das] Wesen unserer Epoch ist Vieldeutigkeit und Unbestimmtheit. Sie kann nur auf Gleitendem ausruhen und ist sich bewußt, das es Gleitendes ist, wo andere Generationen an das Feste glaubten’; see ‘Der Dichter und diese Zeit’, in , Gesamelte Werke in zehn Einzelbänden. Reden und Aufsätze, vol. I (Frankfurt am Main, 1979), 54.