These were the lyrics of the refrain that closed Welcome to Dreamland – a Perspectives show at the Carnegie Hall, New York, in February 2007, curated by David Byrne. The aim of the evening was to showcase the best of the world’s ‘new folk’ movement. As a performer that night, I sang those words alongside Devendra Banhart, Vashti Bunyan, Adem, Coco Rosie, Vetiver, and David Byrne himself,2 and together we closed the show climactically by entreating the thousands in the audience to ‘be’ something that they were not (Ben Ratliff of the New York Times described the audience that night as, ‘models and rock stars and people with money’).3 Since then, I have often wondered: what was the meaning of that request? Can models and rock stars become hobos? What would it look like for a person to ‘become’ something other? What is this ‘becoming’ that the new folk movement recommends to us?

I hope to demonstrate that this notion of ‘becoming’ is especially relevant to critical questions surrounding the new folk movement. I will suggest that Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of ‘becoming-other’4 might help us explore such questions regarding the nature of ‘becoming’ as stated above, and can be used as a particularly effective model through which we can try and understand the complex associations of authenticity related to this genre and its musical output. More specifically, I am going to examine the use of the genre term ‘New Weird America’ (which was a prevalent early description of new folk music) and focus on the work of one artist in particular – Joanna Newsom – who is the most widely known singer-songwriter of the genre.

‘New’ and ‘Old Weird America’

The first significant use of the term ‘New Weird America’ (hereafter NWA) to describe a musical genre, was by David Keenan in his cover article for Wire magazine titled, ‘The Fire Down Below: Welcome to the New Weird America’.5 In this article, Keenan described a, ‘groundswell musical movement’, based in improvisation, and ‘mangling’ a variety of American genres of different ages, including mountain music, country blues, hip- hop, psychedelia, free jazz, and archival blues. Keenan’s construction of the description ‘NWA’ was an explicit reference to Greil Marcus’ term, ‘Old Weird America’ (hereafter OWA). This was used prominently by Marcus in reference to Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music: an album which Keenan says documents the specific, ‘recurrent archetypal forms’, that are being ‘mustered’ by musicians at the start of the NWA movement.6

Smith’s Anthology was a collection of commercial recordings of American folk that were initially released in the 1920s and 30s, some of which were relatively successful. The Anthology itself was released in 1952, after which it is understood to have become the most important recorded source of inspiration for the urban folk revival from which the commercial singer-songwriter genre was born.7 The Anthology was then re-released again in 1997, and went on to influence modern singer-songwriters within the new folk movement. Smith’s compilation now has the status of a double, even triple canonisation: as a re-release of a compilation of re-releases; as a revival of the touchstone of the folk revival; and as a kind of short-circuiting of the historical lineage of the American singer-songwriter movement. There is therefore what Deleuze and Guattari might call an ‘assemblage’ of time that occurs with relation to the music of NWA, and it is this ‘assemblage’ and the understandings of the nature of the work of artists who traverse it that is the focus of the rest of this chapter.

Joanna Newsom is one of the most well-known and critically addressed singer-songwriters of the NWA genre and as such, her work is received as related both to OWA and to key figures of the modern singer-songwriter genre who arose out of the urban folk revival of the 60s and 70s (each with their own musical relationship to OWA). Newsom’s initial reception as part of the NWA genre categorisation meant that her work would constantly be compared and associated with folk recordings of an earlier era. This served to focus critical reception of her work around two key themes, both related to authenticity: firstly, the charge that her work (along with other new folk artists) is based on shallow appropriations of cultural traditions and artefacts from the past, and secondly, that the nature of her vocal performance is imitative and affected. Let us take each of these critical assertions in turn.

A number of strong critics of new folk posit that the relationship between Newsom’s early work and OWA is one of shallow imitation, where Newsom appropriates sounds of American traditional musics of the past purely in order to make her own sound more interesting. One of the most strident criticisms of the work of Joanna Newsom (and other new folk artists) along these lines has come from Simon Reynolds in his book Retromania.8 Here Reynolds characterises Newsom’s work as purely ‘retro’, thus translating her relationship with OWA into a charge of ‘exoticism’.9 Reynolds sees ‘freak folk’ as pure surface – the use of materials of the past simply for the extraction and assumption of an air of difference and ‘hipness’.10 He also places what he describes as ‘freak folk’11 in contrast to the work of more traditionalist British folk musicians.

Putting aside broader problems with Reynolds’ project as a whole (including his self-confessed clear bias towards specifically modernist notions of linear progress),12 with these descriptions he resurrects notions of folk authenticity based on ‘primality’.13 Indeed, the simple dichotomy that Reynolds builds between new folk and ‘authentic folk’ ignores strong critiques of such a narrative from those such as Mark Willhardt.14 These critiques point out the questionable nature of the assumption that there is anything approaching a ‘pure’ folk music to be able to contrast with a more hybrid form particularly in an age of recording.

Newsom doesn’t recognise the description of a gap between herself and the folk performers of a bygone era followed by a sudden desire on her part to listen to folk in order to glean something new from it. What she does recognise is merely a resurgence in interest in this kind of music, which chooses to focus on her:

There is as much of a connection between my music and some of the people I’m being grouped with as there is between it and music that has been made for the last 30 years. I just think it’s awkward. There isn’t a new folk, there’s just a new resurgence of media interest in a kind of music that has been this way for 30 years or more.15

Reynolds’ notion of a clear linear narrative structure to time with artists reaching back or pointing forward along a line does not relate to Newsom’s understanding of a more interconnected pattern of influence. This seems more clearly related to Deleuze and Guattari’s descriptions in A Thousand Plateaus of music being the product of multiple rhizomatic connections across superimposed strata. Here they describe time not as ‘chronos’ – a great plot in sequence, something that divides up into epochs – but as ‘the time of aion’, where many layers are juxtaposed or superimposed.16 Their notion of music as a product of ‘becoming’ means that the artist makes connections between or across these superimposed strata creating, ‘a sort of diagonal between the harmonic vertical and the melodic horizon’.17

The distinction between a mere form of imitation reaching back across a linear sense of time, and a more complex ‘becoming’ is one that is very important in this discussion. Deleuze and Guattari describe the nature of the artist as a ‘becomer’: someone who somehow passes between territories across an assemblage to become a hybrid that is able to articulate a new kind of refrain (an original music). They describe ‘becoming’ in this sense as: ‘Neither an imitation nor an experienced sympathy, nor even an imaginary identification. It is not resemblance … [It is] not the transformation of one into the other … but something passing from one to the other.’18 This important distinction draws near to discussions continuing in the field of ‘world music’ focused on the politics of cultural borrowing– for example exchanges relating to ‘hybridity’ between George Lipsitz, Georgina Born and David Hesmondhalgh, and Timothy Taylor.19

In this context, Born and Hesmondhalgh have called for a more complex, problematised, or multiplied notion of identities involved in cultural musical exchanges (such as between NWA and OWA). Although criticised by Born and Hesmondhalgh for his suggestion of the possibility of a ‘strategic anti-essentialism’ at play in such work, George Lipsitz describes a potential process by which musicians can create ‘immanent critique’ of systems within commercial culture. This acts to ‘defamiliarise’ their own culture and then ‘refamiliarise’ it via new critical perspectives.20 I suggest that the model of ‘becoming-other’ (indicated by Lipsitz’s use the of Deleuzian language of ‘deterritorialization’ and ‘reterritorialization’) can open up the possibility of there being a form of ‘strategic anti-essentialism’ that retains the kind of crucial complexity that Born and Hesmondhalgh describe.21 ‘Becoming’ cuts across the question of intention and appropriation, casting ideas of hybridity and cultural identification in a different, much more complex light. It is also peculiarly appropriate to Joanna Newsom’s work, situated as it is, between notions of personal identity and layers of complex cultural borrowings from past and present ‘others’.

To return now to the second key critique of Newsom’s work – that the nature of her vocal performance style is an affectation – this criticism can also be shown to be related directly to a type of ‘becoming’. Newsom’s voice is frequently referred to in the critical literature in terms related to children (‘childish’), or a sinister form of femininity (‘witch-like’). It is important to note in this context that the specific form of ‘becoming’ that Deleuze and Guattari lay out in A Thousand Plateaus as associated with radical artistry is a becoming-woman, -child, or -animal.22 Ronald Bogue explains why Deleuze chooses women, children and animals in particular:

Social coding operates by way of asymmetrical binary oppositions in Western societies through an implicit privileging of male over female, adult over child, rational over animal, white over coloured etc. A becoming deterritorialises such codes and in its operations necessarily engages the underprivileged term in each of these binary oppositions … A becoming-woman, becoming-child or a becoming-animal however, does not involve the imitation of women, children or animals – an action that would merely reinforce social codes – but an unspecifiable, unpredictable disruption of codes that takes place alongside women, children, and animals, in a metamorphic zone between fixed identities.23

The remainder of this chapter will be dedicated to exploring how reception of Newsom’s early work presented in her 2006 album Ys and, in particular, aspects of the track ‘Only Skin’, can be understood in the context of her work as a form of ‘becoming-child’ and ‘becoming-woman’.24

‘Becoming-child’

Newsom’s voice is frequently described in the press as ‘childlike’. Take for example this review from the Independent in 2004: ‘Newsom sings like a four-year-old witch. With her scratchy squawk, not unlike the noise a cat makes when there are fireworks outside, delivering words that sound as though they were chosen for their cuteness from some old-fashioned rhyming dictionary, she risks appearing irredeemably pretentious.’25 Newsom herself rails against this repeated description, but only insofar as it minimises the seriousness of what she is trying to achieve. In 2006 she countered the charge in a press interview: ‘[T]he songs are really dark. Not just dark, they’re adult. They’re actual heavy shit.’26

Contrast this with the themes of childhood scattered throughout Ys (as with all of her records) that attest to Newsom’s preoccupation with childishness. Often, Newsom quotes nursery rhymes, children’s tales, childhood memories (such as climbing a tree house, tramping through the poison oak, having pockets full of candy), and creates childish neologisms and characters such as, ‘Sibyl sea-cow all done up in a bow’. In the closing section of ‘Only Skin’– the duet with Bill Callahan – Newsom echoes the form, the rhythm and some of the sentiment of the children’s song ‘There’s a Hole In my Bucket’, with falsetto female voices answering the male questioning. During this section she also makes lyrical reference to ‘Rock-A-Bye-Baby’ and even hints at the nursery rhyme ‘Old Mother Hubbard’.

Besides these references, we also have repeated statements and metaphorical suggestions of a deep desire to be taken back into the womb. In ‘Emily’ (another song from Ys) the narrator describes herself, ‘In search of a midwife who can help me, who can help me, help me find my way back in’. This is reflected too in the most pervasive theme in the whole album: the multiple and repeated references to being submerged in water. The album is named after the myth of Ys – a city submerged in the ocean – and in this context submersion is typically representative of a womb-like state where the foetus floats suspended in amniotic water.

Despite the superficial impression of these simple lyrical references to childhood, it is clear that the child-theme in Newsom’s work is not related to a romantic, pastoral idea of a past innocence. On the contrary – it can be seen as a subversive act of becoming, as Deleuze and Guattari would describe it. This becomes particularly clear with relation to Newsom’s use of what is portrayed as ‘childish’ vocal tone/gesture and received accordingly as ‘affectation’. As the following quote from Newsom suggests, her vocals are not an imitation of a child, but the political act of someone questioning the affectation of the institution of singing itself: ‘I was like: I’m going to sing my heart out, as crazy as it sounds, and I’m not going to care because there’s no hope of sounding anything like what people consider beautiful. I sure as hell wasn’t affecting anything. I mean, the institution of singing is inherently an affectation.’27 The assumption implicit in criticisms of the inauthenticity of Newsom’s voice is the equation of ‘natural’ with a particular style of singing (controlled, smooth, non-nasal, ‘in-tune’, utilising vibrato), and ‘affected’ with anything else. But Newsom’s argument here is that it is the trained Western singing voice in fact that is the construction. Her efforts therefore are not to imitate a childish or OWA Appalachian voice, but to reject the inauthentic constructions of the trained Western voice.

John Alberti’s description of the work of the ‘faux naif’ is enlightening here. He explores the work of Jonathan Richman – an artist extremely influential in the punk movement – as a ‘strategic invocation of childhood’ that ‘can be read as a gesture towards the concept of pre-ideological space as a point of radical disruption of the mainstream consumption of rock music’.28 There is a strong and enduring political subversiveness to Richman’s invocation of childishness, which Alberti maintains is a strategic action.29 The same is patently the case in Newsom’s work, where she consistently ‘becomes-child’, and sings with a voice that questions and radically disrupts territorial notions of identity and cultural institutions (for example, the constructedness of the institution of the trained singing voice).

This action also disrupts notions of the singer-songwriter’s voice as the site of communication of personal confessional meaning. There is widespread understanding of the singer-songwriter as a performer of ‘self’ i.e. presenting inherently confessional work that represents the personal identity of the singer. In this context, the voice, as a site of personal identity, becomes a site of contention where that voice is conceived to be, ‘not the singer’s own’.30 I would like to suggest then that Newsom’s vocal sound is the product not of an intentional and therefore inauthentic act of imitation, but a becoming that occurs via the composer’s affinity with practices of ‘others’ that reflect a different (subversive) perspective on aspects of her own practice.

‘Becoming-woman’

Where Newsom’s identity-obfuscating vocal strategies work against notions of the singer-songwriter as having an emotive confessional identity, her recordings also serve to work against damagingly stereotypical understandings of the ‘femaleness’ of the singer-songwriter genre. Such stereotypes are exemplified by the following quote from Ronald Lankford, describing the history of the female singer-songwriter as one of apolitical, emotional self-exploration:

Because the singer-songwriter style was ultimately harmless regarding its social impact it also provided a safe and acceptable place for women who wished to enter the music business. A woman who expressed her personal feelings about love and life while accompanying herself on piano or acoustic guitar had little room to flaunt her sexuality or protest an unequal gender system.31

Newsom’s work in ‘becoming-woman’ in her recording of ‘Only Skin’ is contextualised via numerous clear lyrical references to femaleness. Twice we hear direct repeated exhortations to ‘be a woman’, echoed in its repetition by a warning of the perils of ‘being a woman’ (‘knowing how the common folk condemn what it is I do to keep you warm, being a woman, being a woman’). The narrator also speaks of being the ‘happiest woman among all women’ i.e. the epitome of a woman.

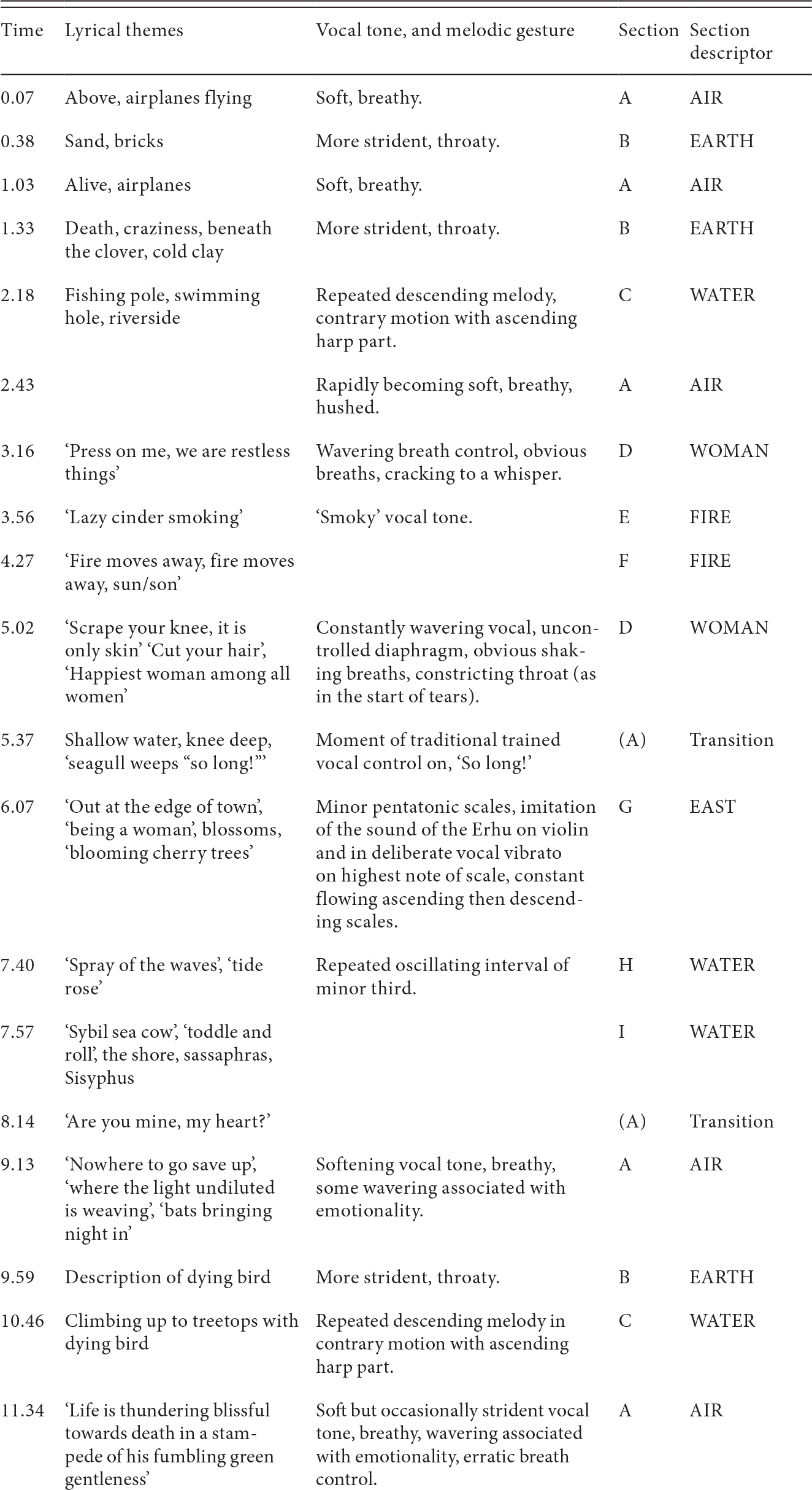

In this context, i.e. the lyrically stated context of a becoming-woman, I am going to propose that ‘Only Skin’ is indicative of what Deleuze and Guattari would describe as ‘transverse becomings’, which are a flux between and across non-fixed identities. The structure of ‘Only Skin’ is such that we constantly flux back and forth between the binary oppositions Air/Earth, Water/Fire, East/West, and, less conspicuously, Woman/Man, Adult/Child. Table 17.1 displays these relations with regard to the structure of the song. I have described each section as: Air / Earth / Water / Fire / East / Woman / Child, and I have apportioned these sections largely with relation to melodic and rhythmic content, but also with regard to lyrical themes and vocal gesture.

Table 17.1 Joanna Newsom's ‘Only Skin’

| Time | Lyrical themes | Vocal tone, and melodic gesture | Section | Section descriptor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.07 | Above, airplanes flying | Soft, breathy. | A | AIR |

| 0.38 | Sand, bricks | More strident, throaty. | B | EARTH |

| 1.03 | Alive, airplanes | Soft, breathy. | A | AIR |

| 1.33 | Death, craziness, beneath the clover, cold clay | More strident, throaty. | B | EARTH |

| 2.18 | Fishing pole, swimming hole, riverside | Repeated descending melody, contrary motion with ascending harp part. | C | WATER |

| 2.43 | Rapidly becoming soft, breathy, hushed. | A | AIR | |

| 3.16 | ‘Press on me, we are restless things’ | Wavering breath control, obvious breaths, cracking to a whisper. | D | WOMAN |

| 3.56 | ‘Lazy cinder smoking’ | ‘Smoky’ vocal tone. | E | FIRE |

| 4.27 | ‘Fire moves away, fire moves away, sun/son’ | F | FIRE | |

| 5.02 | ‘Scrape your knee, it is only skin’ ‘Cut your hair’, ‘Happiest woman among all women’ | Constantly wavering vocal, uncontrolled diaphragm, obvious shaking breaths, constricting throat (as in the start of tears). | D | WOMAN |

| 5.37 | Shallow water, knee deep, ‘seagull weeps “so long!”’ | Moment of traditional trained vocal control on, ‘So long!’ | (A) | Transition |

| 6.07 | ‘Out at the edge of town’, ‘being a woman’, blossoms, ‘blooming cherry trees’ | Minor pentatonic scales, imitation of the sound of the Erhu on violin and in deliberate vocal vibrato on highest note of scale, constant flowing ascending then descending scales. | G | EAST |

| 7.40 | ‘Spray of the waves’, ‘tide rose’ | Repeated oscillating interval of minor third. | H | WATER |

| 7.57 | ‘Sybil sea cow’, ‘toddle and roll’, the shore, sassaphras, Sisyphus | I | WATER | |

| 8.14 | ‘Are you mine, my heart?’ | (A) | Transition | |

| 9.13 | ‘Nowhere to go save up’, ‘where the light undiluted is weaving’, ‘bats bringing night in’ | Softening vocal tone, breathy, some wavering associated with emotionality. | A | AIR |

| 9.59 | Description of dying bird | More strident, throaty. | B | EARTH |

| 10.46 | Climbing up to treetops with dying bird | Repeated descending melody in contrary motion with ascending harp part. | C | WATER |

| 11.34 | ‘Life is thundering blissful towards death in a stampede of his fumbling green gentleness’ | Soft but occasionally strident vocal tone, breathy, wavering associated with emotionality, erratic breath control. | A | AIR |

| 12.07 | ‘I was all alive’ | Increasingly wavering and bodily vocal, obvious breaths, uncontrolled vibrato. | D | WOMAN |

| 12.44 | Stoke, flames, ‘fire below, fire above and fire within’ | Breathy, smoky main vocal with piercing throaty harmony vocal. | E | FIRE |

| 13.14 | ‘Fire moves away, fire moves away sun/son/some’ | Softer tone, with soft, higher harmony on ‘why would you say’. | F | FIRE |

| 13.48 | Woman: cherry stone, cherry pit, cherry tree, ‘think of your woman who's gone to the West’ Child: ‘cold cold cupboard’, ‘when the bough breaks’, ‘a little willow cabin to rest on your knee’ | Childlike call and response, harsh ‘witchy’ childish vocal tone most prominent in the ‘response’ harmonies (in contrast to deep smooth male vocal), prominent accelerando (associated with performance of strophic children's songs). | D | WOMAN / CHILD |

| 15.38 | ‘Fire moves away, fire moves away sun/son’ | Soft, breathy, smoky vocal tone. | F | FIRE |

| 16.15 | Fire, fire, fire, woman, heights | A | AIR / FIRE / WOMAN |

This table differs somewhat from the mapping of the form of ‘Only Skin’ given by John Encarnacao.32 As he suggests himself, his structural breakdown refers only to melodic/harmonic content and therefore misses some of the nuances of arrangement etc., to which the breakdown in Table 17.1 pays attention. The summary represented here is based on a consideration of structure that takes into account a range of structuring features (i.e. not only melodic and harmonic repetitions, but lyrical themes and vocal gesture), and therefore, as is the case with any analysis of artistic content, the distinctions are not always clear-cut and there is some overlap between sections. One example of the kinds of distinctions being considered along with the melodic and harmonic content is vocal gesture. So where the lyrical imagery predominantly or prominently relates to flight, air, looking up, sky, climbing, height (i.e. mountaintops), or life, and where the vocal tone becomes largely breathy and mellow in combination with particular melodic and harmonic themes, the section is labelled as ‘Air’. Such a relationship can be heard, for example, in the recording at 1.07, where Newsom sings, ‘took to mean something run, sing; for alive you shall ever more be’. Compare this to the harsh, nasal, Appalachian vocal tone present at 14.36 when Newsom sings, ‘when the bough breaks what will you make for me, a little willow cabin to rest on your knee’ (contrasted markedly to the smooth, deep, controlled vocal tone of Bill Callahan) which I have characterised as ‘Child’. This comes in the context of the call and response mimicking of the childhood song, ‘There’s a Hole in my Bucket’ and with lyrics echoing other nursery rhymes such as ‘Rock-a-Bye Baby’.

The section marked ‘Woman’ relates more to the vocal gesture than the lyrical content, and here we hear the vocal tone as markedly swayed by excitement or sadness via shallow, erratic breath control and wavering tone. This gives the vocal performance an impulsive and moving quality, where breathing is obvious and there is the wavering and constricting of voice that is associated with the beginning or end of tears. This eruption of the bodily in the voice would be associated with the feminine by theorists such as Julia Kristeva, who characterises the ‘semiotic’ in opposition to the ‘symbolic’. The semiotic (suppressed by the symbolic) resurfaces in language as rhythms, pulses, intonation, the bodily qualities of the voice, the bodily qualities of the word, silences, disruptions, gestures, contradictions, and absences. In becoming-female then, one might expect that an artist would allow a focus on these aspects of language that have been repressed by the symbolic.33

Looking at the overall structure of the song as mapped out in the table, we can see the constant fluctuation between sections – particularly between air and earth. This motion or waving between oppositions, represents what Deleuze and Guattari equate with ‘becoming-woman’ – ‘the molecular’: a flux between non-fixed identities.

Within the sections labelled ‘Water’ the melodic structure also illustrates a constant waving motion with insistently ascending and descending passages, sometimes in long sweeping repeatedly descending vocal melodies which are placed in contrary motion to ascending scalar harp accompaniment (for example at 10.45 where Newsom sings, ‘then in my hot hand she slumped her sick weight’), and sometimes in repeated single intervals (for example the oscillating movement across a minor third at 7.38 as Newsom sings, ‘we felt the spray of the waves we decided to stay ‘til the tide rose too far’). The frequent word-use relating to directionality that is persistent throughout the track merely serves to emphasise this sense of perpetual motion.

It is this flux – in the form of what we might call meta-sound-waves – that creates the music of ‘becoming-woman’. The complex structure of the song, which constantly waves between identity-based themes, is complemented by Newsom’s use of vocal tone and gesture, which flows from timbre to timbre in association with the type of transverse movement she is implying at any point. This constant rise-and-fall, back-and-forth movement between identities is complemented by the wave-like theme of water running throughout Ys (which I referred to earlier with relation to becoming-child) and is exemplified in the lyrical image of Sisyphus (who constantly rises and falls).

It is always a form of wave that creates music, and as such, Deleuze and Guattari maintain that music is the product of a flux of transverse ‘becomings’ across time and identities. In this way I have shown how Newsom’s music can be perceived to be created out of this form of flux, and thus demonstrates a ‘becoming’. The persistent waving back and forth between images of masculine and feminine identities in ‘Only Skin’ I would argue, is therefore central to the effect of the song as a whole. I have attempted to show how this is effected via vocal gesture, melodic and harmonic thematic structuring, specific melodic shaping, and in relation to explicit lyrical themes.

To answer the question that opened this chapter, it is clear from this analysis that the ‘becoming’ that NWA might recommend to us is not always a case of imitating other- or past- cultures (i.e. OWA), but can be a more complex process of traverse and flux between multiple identities. Newsom’s work does not succumb to Reynolds’ critique of shallow borrowing from the past, but rather it displays a complex form of strategic anti-essentialism that involves the crossing between numerous multiple identities. This process can cross stable political boundaries and linear conceptions of both time and identity in a way that, far from reinforcing cultural hegemonies, serves to destabilise them. Negative critical reception of this work that casts it as purely ‘retro’ or ‘inauthentic’ can thus indicate (and also mask) more complex actions at work within the music and between the music and the modern listener.