I have wandered through almost every region to which this tongue of ours extends, a stranger, almost a beggar …

The lyrics range from scriptural verses about Lucifer and the Prodigal Son to stories of beggars, sinners, prowlers, addicts, transients, outcasts, Black militants, groupies, and road-weary troubadours; the web of musical influences is spun with multi-colored threads of urban and rural blues, country, calypso, R&B, rock and roll, folk, gospel, and even the English choral tradition. The four albums released by the Rolling Stones between 1968 and 1972 – Beggars Banquet, Let It Bleed, Sticky Fingers, and Exile on Main Street – constitute for critics, fans, and historians the core identity of the group and the lasting, canonical repertory that has defined the Stones’ musical, historical, and cultural legacy.1 As Jack Hamilton has written in a recent study of the group, the band’s years from 1968 to Exile amount to “one of the great sustained creative peaks in all of popular music.”2 An insider’s perspective on the moment when the Rolling Stones were guaranteed a place of distinction in the history of music is offered by Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner. As the group finally extricated itself from the management of Allen Klein and ABKCO in 1970, Wenner implored Mo Ostin of Warner Bros to sign the group without delay:

Dear Mo, The Rolling Stones contract with London/Decca is now up, or shortly about to be. They are not renewing. They are looking for a new label and company in the USA, but not their own label. They have two LP’s now in the can almost ready for release: Live in the USA [Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!], and the one they are [finishing] or have finished from Muscle Shoals [Sticky Fingers].

Mick Jagger is the one who will make the decision on who is their new label. It’s worth everything you’ve got to get this contract, even to lose money on it. The label that gets the Stones will be one of the winners in the 70’s.

Contact Mick directly in London at MAY 5856, 46A Maddox Street, W1. [followed by in red pen] NOW.3

The critical reception of these albums, documented extensively in both published and video accounts since their release half a century ago, has only affirmed their historical relevance within the political and generational tensions of the late 1960s and early 1970s.4 Let It Bleed – “Gimme Shelter” in particular (both the song and the film) – has been immortalized as a live broadcast of the abrupt shift from utopian Woodstock ideals of July, 1969 to the crushing dystopian reality – the “Pearl Harbor to the Woodstock Nation”5 – of the Altamont tragedy only five months later. Sticky Fingers is seen as a poetic but dark chronicle of addiction, obsession, dependency, and refuge; and “Sympathy for the Devil,” from Beggars Banquet, is the ubiquitous point of reference for any discussion of the volatile activism, assassinations, and racial tensions in 1968 America, a country inextricably mired in the Vietnam War and its related protests. Godard’s 1968 observational film One Plus One [Sympathy for the Devil] was remarkably prescient through its resolute focus on the slow evolution of “Sympathy for the Devil” as a metaphor for Marxist anarchy brewing in the streets, a premonition shared even by Jagger: “There’s no doubt there’s a cyclic change,” he says in a May, 1968 interview during the anti-Vietnam protests in Grosvenor Square in London, just prior to the student riots in Paris; “a VAST cyclic change on top of a lot of smaller ones. I can imagine America becoming just ablaze, just being ruined …”6 Finally, Exile on Main Street, while breaking no new ground stylistically, frames for posterity the permanent identity of the Stones through the album’s themes of both poetic and living geographical exile. It is a summation of the musical diversity introduced by the previous albums in which the deep roots of their style are laid bare in the present: There is no old and there is no new in the musical vocabulary of Exile. As Janovitz writes in his study of the album, “[Exile] seems to revel in self-imposed limitations. In fact, it sometimes sounds ancient. Other times it sounds completely current and modern. It sounds, at various points, underground and a little experimental, and at others, classic and even nostalgic.”7

These four releases are not the most popular-selling albums by the Stones, nor do the 57 songs they contain – out of an entire catalog of around 400 – amount to an unusually large concentration of material within any five-year period of their recording history; there is far more music recorded before 1968 and after 1972.8 But beginning with Beggars Banquet of 1968 we see a profound deepening of the vernacular dialects of rock and roll as the group traveled from metropole concerns of urban blues, Mod London, and the middle-class audiences of the Ed Sullivan show on to a new landscape of a vast America and its “distant” traditions of Delta Blues, rural country, and older texts. They infused these genres and their lyrical themes with the raw exilic qualities of distance and authenticity as metaphors for a contemporary culture they saw as revolutionary, disruptive, and teeming with racial and generational strife. Like exiles before them, they were stuck at the crossroads of participation and reflection. While the group recognized deep societal violence and struggle, it remained disengaged from the action at a critical, poetic distance, offering commentary, not combat. As Jon Landau wrote in Rolling Stone,

the most startling songs on the album are the ones that deal with the Stones’ environment: “Salt of the Earth,” “Street Fighting Man,” and “Sympathy for the Devil.” Each is characterized lyrically by a schizoid ambiguity. The Stones are cognizant of the explosions of youthful energy that are going on all around them. They recognize the violence inherent in these struggles. They see them as movements for fundamental change and are deeply sympathetic. Yet they are too cynical to really go along themselves.9

Symbols of moral and political upheaval abound in the lyrics: a “man of wealth and taste,” Lucifer in “Sympathy for the Devil” cavorts among guests at a dinner party but kills both Kennedys; in “Stray Cat Blues” an underage daughter runs away and is raped, but the justification is that it’s “no capital crime”; there are marches in the streets; sinners are saints, cops are criminals. At the same time, the Stones’ voices are somewhere else: The lyrical and musical Impressionism of “No Expectations” and pentatonic Orientalism of “Moonlight Mile” are reflections, memories, and dreams, not actions; the “Street Fighting Man” is actually uncommitted to the struggle, and the Prodigal Son can’t make it on his own, even with his inheritance. So much talk, so little action. In many ways, the only songs offering unequivocal, unambiguous themes are the proletarian tributes “Factory Girl” and “Salt of the Earth.” In short, the albums beginning with Beggars and ending with Exile painted the authentic musical portrait of the Stones that established their most recognizable and durable image, even if it is often contradictory. For fans, every phase of the band since then is a variation on this basic master narrative.

What is this narrative? It might be defined as follows: an exilic and itinerant sense of being – one largely shaped by Keith Richards – derived from the migratory aspects of the blues, and a fearless, ever-deepening search for musical roots of all kinds; a tough, unyielding attitude – again, Richards – that was revolutionary but devoid of overt politics or constituency; a sharp intuition – shaped here mainly by Mick Jagger – about the largely uncharted and fluid sexual and gender boundaries of the day that played out metaphorically and physically in song lyrics, performance, and wardrobe;10 a deep-seated subversion powered by their reverential identification with African-American and rural idioms; and, importantly, an obsession with the exiled, with Blackness, and culture at the margins, exposing “fantasies of low life and life below the stairs.”11 By the time of Exile on Main Street, the Stones, all but Bill Wyman not yet thirty years of age, themselves became the road-tested bluesmen whose deep oral and recorded repertories narrating travel, loss, hopes, lust, and judgement comprised the rich vocabulary of their period in exile.

The period from Beggars through Exile further coincides with important developments with the band that, in turn, initiated several future directions. 1969 witnessed the first major personnel change as a result of Brian Jones’ death in 1968 and the subsequent joining of Mick Taylor, ushering in a period when, musically, the group has never been stronger. Taylor, a young, skilled guitarist whose musical education was formed in the long blues corridors of the John Mayall Band, was a virtuoso bottleneck player, and provided the Stones with their first true “lead” guitarist, resulting in an expansion of their song forms, particularly in live performance, through sections of brilliant solos, distinct tone, and improvisation. 1969 also marks their critical return to touring, following a hiatus from the road of almost two and a half years that was dominated by fighting various drug busts – mainly the well-documented “Redlands Scandal” – and increasing financial distress.12 The aggregate problems of economic and legal persecution ultimately led to their move in 1971 to the South of France as vrai tax exiles. But these years also reveal a new songwriting process in which the system of recording songs for imminent album release is abandoned in favor of longer gestation periods and revision. Much of the material on the Beggars through Exile albums was, in fact, conceived simultaneously, the composition of many songs begun years before their eventual release – a chronology that is not present prior to Beggars. The earliest takes of “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” and “Sister Morphine,” released in 1969 and 1971, respectively, can already be found in May and November, 1968. Many songs that would appear on Sticky Fingers (1971) and Exile on Main Street (1972) have their origins already in 1969, including “Brown Sugar,” “You Gotta Move,” “Wild Horses,” “Dead Flowers,” “Loving Cup,” and “All Down the Line.” Similarly, the origins of “Stop Breaking Down,” “Sweet Virginia,” and “Hip Shake” are found in 1970, prior to the band’s move to France and two years before release. This chronology testifies to the musical affinities and common sessions between the four albums that form a distinctive and cohesive creative phase in the history of the Rolling Stones.

Figure 4.1 Poster for the 1972 “Exile on Main St” American tour.

Exiles and the Tent Show Queen

The subversive language of “Casino Boogie” is syntactically exclusive to the Stones, and serves to identify and ally the outsider, who is the exile, peering in, and his encounter with others along his journey. Here, it is the characteristic voice of the exile firing cryptic assaults on establishment, convention, and hippie idealism by using the decoys of rich, American gamblers squandering millions in the luxury slum of Monte Carlo’s casinos. Indeed, according to Janovitz, the song’s lyrics depict “casual disdain for authority, drug-bust martyrdom, and the band’s pressure to ‘exile’ themselves,” with the last two lines “captu[ring] the essence of Exile on Main St: surreal rock & roll, jet-set sexuality, decadence, and boredom with the tired themes of the 1960s.”13 As a punitive means, exile was imposed on those who could do the most harm, and it recognizes high standing. But exile is also self-imposed, for it is within the “sanctuary” of exile that writers find a powerful voice that is the product of roaming and resistance. It is at once the voice of banishment, homelessness, and encounter with a new world. Linguistically it draws on forms, accents, and syntax that bridge high and low, and finds power and inspiration in dialect and popular forms.

In 1971 the Stones, debt-ridden, literally went into self-exile in the south of France, due to the high taxation laws in the UK that left the group unable to meet their income tax responsibilities. Their exile was also the conclusion to years of systematic arrests by the police on often-fabricated drug and indecency charges that are widely believed to have been part of a particular vendetta against the group. The qualities of exile described above appear throughout Sticky Fingers, in which the poetic squalor of practically all of the songs suggests distance and travel. Musically, they call out from elsewhere through an intentional stylistic apartness: the orientalism of “Moonlight Mile”; the long instrumental jam, unique in the Stones’ output, at the end of “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking”; the Stax-influenced “I’ve Got the Blues”; and, as noted earlier, the solitary withdrawal of the victim in “Sister Morphine.” With Exile on Main Street, conceived amidst the rich opulence of the French Riviera, the group moves on to employ a variety of musical styles that take the form of “dialects” that are effectively used to speak in code while simultaneously asserting the Stones’ personalities as Others and transients. Within this multi-vocal setting, the Stones employ gospel as a way to mask sex songs (“Let It Loose,” “Loving Cup”), country influences to tap into the deep American roots songbook that became more authentic – in tone and technique – through the influence of Gram Parsons, Calypso for a protest song about Black militant Angela Davis (“Sweet Black Angel,”, sung in “Caribbean” dialect), and blues for traditional attacks on high-class pastimes.

Exiles and the Circus

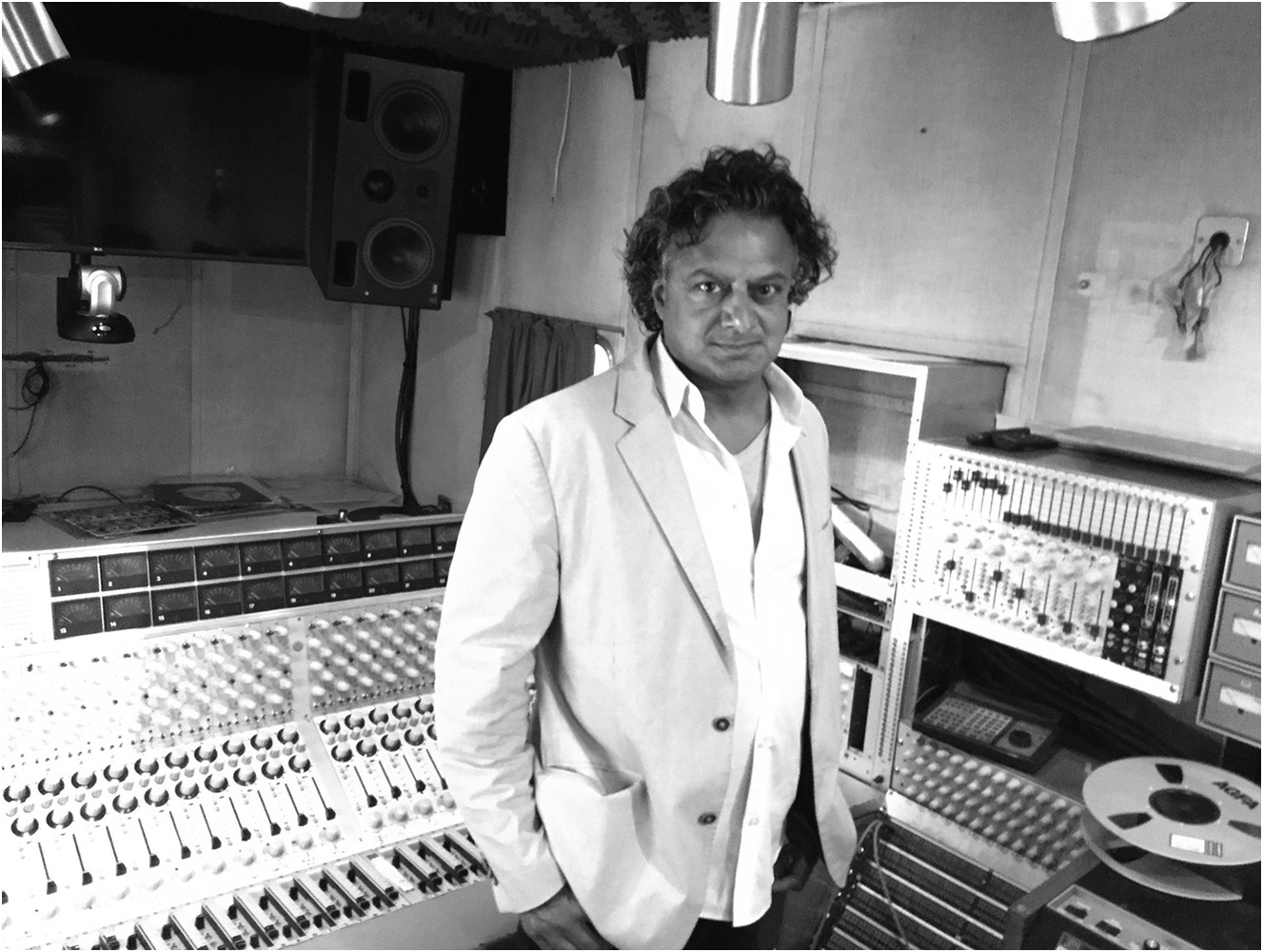

Satan was the first exile (Revelation 12.7), followed across the ages by Odysseus, the Holy Family, Dante, Solzhenitsyn, the Dalai Lama, Marvin Gaye, and … the Rolling Stones. Historically, the condition of exile is associated with banishment – both real and imagined – the exiler becoming a verbal target for reprisal, cryptic assault, and condemnation by the exiled. Whether the result of intense political opposition (Dante) or tax evasion (Gaye, the Stones), the sentence of exile amplifies displacement and protest through the use of vernacular dialects, subversive themes, and ancient texts. Nostalgia, mobility, alienation, linguistic variation, encounters with Others, religious themes, and recourse to Scripture are recurring exilic themes. With the Stones, references to the outsider, the use of different voices, vocal delivery, genre, choice of lyrics, stylistic diversity, and sound contribute to this autobiographical notion of exile. Even their recording conditions, in the form of a mobile studio (see Figure 4.2) beginning with the Exile sessions, are critical to the decentralized, “exilic” sound and songwriting strategies of the Stones during this period, as they create their own rural musical space in the image of the legendary studios of the American south like Muscle Shoals and Stax.

Figure 4.2 Author in front of the 24-track Helios console inside the Rolling Stones Mobile studio, 2016.

Reflecting on the end of the group’s first American tour in 1964, Keith Richards wrote that he thought the group had “blown it”: “We’d been consigned to the status of medicine shows and circus freaks with long hair.”14 Ironically, the image of the circus act is a recurring image in the group’s music and overall self-perception between 1968 and 1972. Although the Stones’ period of exile is a physical reality in 1971 with their move from England to France, the roots of their displacement can be found at the beginning of this period of creativity, most visibly in the Rock and Roll Circus of 1968, a fully realized project intended as a BBC television special that was eventually shelved until its official release on videocassette in 1996.15 Using the backdrop of a “big top” circus tent (with Mod accents, to be sure), the project features performances by many of the most popular and emerging British rock and pop acts of the day – the Who, Jethro Tull, the “Dirty Mac” supergroup with John Lennon, Eric Clapton, Keith Richards, and Mitch Mitchell, along with appearances by Marianne Faithfull and Yoko Ono – interspersed with conventional acrobatic routines by authentic circus acts (funambulists, fire breathers, lion tamers, etc.). Intentionally or not, the Stones project here the idea of the rock concert as a circus, its performers likened to trained acts to play before audiences seeking their own vicarious thrills, living perilously on the edge of success and failure, and marginalized – as Richards recounts from the 1964 tour – as a circus act.

Indeed, the circus performer is a classic “exile,” especially if in the sideshow. Classified as “misfits,” humans with physical deformities, unusual physical abilities, biological difference, and birth defects were leveraged as circus acts alongside other sideshow performers of specious authenticity. The connection between these circus performers and the Stones comes full circle with Robert Frank’s cover for the Exile on Main Street album, which, taken from photographs he had shot for his legendary book The Americans, and in close collaboration with Jagger about the design, featured black and white photos of various circus performers exhibiting their unusual abilities, with some images used individually to promote the 1972 tour (see Figure 4.1).16 As Richards remembers, “Exile was a double album. And because it’s a double album you’re going to be hitting different areas, including D for Down, and the Stones really felt like exiles.”17

Sacred Exiles

Sacred references are frequent in the Stones’ music from these years, as they are in Delta blues, not only through allusion or quotes from Scripture, but in the use of sacred sound and style. In the song “Far Away Eyes” from Some Girls of 1978, the media-driven tele-evangelical movement in America is cleverly (and acutely) parodied through Jagger’s drawl, the mimicry of the radio preacher seeking $10 tithes, and the signature pedal steel parts played by Ronnie Wood, but there is nothing really sacred about the song.18 Earlier, however, the allusions were more sober, probing, and authentic. The Stones incorporate sacred idioms from sources as diverse as the English choral tradition, American gospel, and the small-town Salvation Army funeral procession, that, drawing on the emotional arc of the gospel service, provide climactic and conclusive moments within the songs.

“Prodigal Son” (text drawn from Luke 15:11–32), on Beggars Banquet, is a moralizing story, a version – calling it a “cover” does not do the song justice – of Rev. Robert Tim Wilkins’ “That’s No Way to Get Along” that he originally recorded in Memphis in 1929 but later (and after having renounced the life of a bluesman and joined the church) rerecorded as “The Prodigal Son” in 1964.19 It is this latter version that draws specifically on the story given in Luke and is the immediate influence, both in the guitar work and the lyrics, for the version by the Stones. Appearing on an album whose opening track recounts the destructive history of Satan (“Sympathy for the Devil” [BB]) and his contemporaneous killing of the Kennedys, “Prodigal Son” reaches back to the rural style of its author, Jagger mimicking the old bluesman’s voice and Richards patterning his strumming in E-tuning after Wilkins, against a duo of harmonicas and a clutter of makeshift-sounding percussion. The effect is that of a street-corner performance somewhere in the Delta for a retelling of the best known of Jesus’ three parables, this one foregrounding the themes of greed, reconciliation, family, and ultimately forgiveness. In the end, the song is unlike any other original blues arranged anew by the Stones due to its raw, rural sound, as if one were suddenly listening to one of Alan Lomax’s important field recordings of southern Blues.

It is the American gospel tradition, though, that is the most pervasive influence on the Stones in this period. Gospel techniques create call-and-response textures (heard, for example, on “Tumbling Dice” [EMS]), they reference gospel’s musical progeny, R&B, and they further create climactic moments that recall the rapturous conclusion of gospel church services, heard at the ends of “Salt of the Earth” (BB), “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” (LB), and “Shine a Light” (EMS). But the exhilarating crescendos of heavenly gospel textures are also used to celebrate sex (“Loving Cup” [EMS]) and, more darkly, sexual surrender (“Let It Loose” [EMS]). At a formal level, the fact that “Salt of the Earth” and “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” – the final songs of Beggars Banquet and Let It Bleed, respectively – both conclude with high-energy gospel choruses, suggests that the organization of the albums themselves draws on the plan and rhythm of the gospel service in which confession and community are ultimate themes. Thematically, both albums begin by a stark acknowledgment of evil and tragedy, but they eventually conclude with the same choral exhilaration that accompanies the arrival in the gospel church of the Holy Ghost. In “Sympathy for the Devil” (BB) Satan introduces himself by immediately speaking over the macabre, samba-like rhythm of a Totentanz, while in “Gimme Shelter” (LB) the distant howling (vocalized by Merry Clayton) in the foreboding introduction and relentless three-chord descending progression underlie the premonition of storms, rape, and murder. Halfway through Beggars we hear a “sermon” about the Prodigal Son and the lesson of forgiveness; in the case of the much darker Let It Bleed, it is rather the grisly fulfillment of the foretold rape and murder by the appearance, halfway through the album, of the Midnight Rambler. In the end, however, both albums banish their evils musically and textually by uplifting gospel choruses.

“Salt of the Earth” (BB) – a song that was powerfully revived by Jagger and Richards at the Concert for New York City following the 9/11 attack – begins, as its title suggests, like a boozy, closing-time song in a worker’s pub, in which everyone, arms around each other, eventually joins in. It continues the proletarian theme, already introduced by “Factory Girl,” to raise a glass to the working class and “lowly of birth” – socialist folk sentiments persuasive enough for Joan Baez to decide to record her own version of this song a few years later. It is often said that those looking for actionable messages in Beggars Banquet will not find them. “Street Fighting Man,” which would seem to be the most incendiary of the songs on this album, with its megaphone, front-of-the-pack vocal charge, and the driving march of the IV–I chords, recedes into apathy: “But what can a poor boy do/but sing in a rock and roll band?” “Salt of the Earth,” too, seems to give a pass to those watching on the sideline: “Spare a thought for the stay-at-home voter/His empty eyes gaze at strange beauty shows/And a parade of gray suited grafters/A choice of cancer or polio.” After verses sung individually and together by Jagger and Richards, the song builds to a climax through short, pungent bursts of slide guitar (similar to what takes place in “Jigsaw Puzzle” [BB]), until the Watts Street Gospel Choir of Los Angeles enters at the end of the second refrain. Taking over the chorus sung by Jagger and Richards, the choir suddenly (and characteristically gospel) kicks the tempo into double time for a foot-stomping, sway-in-the-aisle conclusion. “Salt of the Earth” is an exile commentary about honoring “workers” over the owners, and it could just as easily be a rant against the record industry, the “workers” being the artists under contract.

The Theater of Exile

Richards has cleverly described the song “Midnight Rambler” (LB) as an unintentional “blues opera,” with its Boston Strangler libretto – many lyrics were taken literally from the confession of the actual Boston Strangler, Albert DeSalvo20 – and the horrifying, still, recitative section in the middle of the song where the killer, in a whisper punctuated by thrusts of the knife, torments his victim. This kind of dramatic presentation pervades other pieces of the period, as the Stones become more adept at “staging” their songs almost as small one-acts. In “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” (LB), they employ gospel and sacred sound to force multiple contrasts: the present against the past, England vs. America, black vs. white rhythm, and the black vs. the white church, all theatrically mounted on a sonic “stage” for this seven-minute-plus finale to Let It Bleed. The nostalgic opening of the song is one of the most beautifully written moments the Stones ever produced. The curtain is raised with an Anglican-style “hymn” sung by the London Bach Choir, that, despite some rather awkward text setting (the two-note descending figures given to the one-syllable words “hand” and “man,” for example), opens up a spacious and sonorous dimension of time, distance, and memory. As sung by the choir, the scored hymn section provides the day’s lesson in an authoritative, didactic fashion. Emerging out of the final note of this first choral refrain is the I–IV strummed riff of Richards’ E-tuned capo’d acoustic that appears from yet another seemingly distant part of the space, coupled with Al Kooper’s French horn solo sounding, too, as if from the distance, like the off-stage horns we hear in Mahler. Thomas Peattie has written about “distant sound” in Mahler’s works as being part of a theatrical moment in which instrumental music becomes linked with opera.21 When the conclusive words (“You get what you need!”) of the refrain return after Jagger’s first verse (2:01), the transformation is complete: The Anglican choir now gives way to the gospel singers for a joyous community celebration. The refrain, first sung ex cathedra, is now familiarized stylistically for the vox populi. But, more importantly, it signifies a deepening, a celebration, even the primacy of African-American idioms in the Stones’ music – an influence that was present at the beginning (the name of the band, of course, comes from the title of a Muddy Waters song), but is now dramatized with a narrative that invites commentary about the Stones and race. Returning to the song, for the next two verses the Bach Choir is silent, but following the bridge section (4:17) the exciting coda unites both the Bach and gospel choirs in an ecstatic gospel ending that is propelled – as we heard in “Salt of the Earth” – into the fadeout by shifting into a quick two-beat double-time rhythm.

The spiritual “You Gotta Move” (SF), a group arrangement of bluesman Mississippi Fred McDowell’s song of the same name (an earlier version he may have known is the Original Blind Boys of Alabama’s recording of 1953), is another excellent example of the theatrical imagination of the Stones and how they brilliantly conceive a dramatic and historical narrative out of an acoustic blues. McDowell’s riveting performance, recorded in 1965 at the end of the folk/blues revival, features him doubling his vocal line on slide guitar and adding instrumental breaks between the vocal verses, suggesting many adaptable options for the Stones, now with Mick Taylor comfortably integrated into the group. The exilic, dialect vernacular of spirituals is made for the Stones. Spirituals contain irresistible hooks, and many popular R&B songs like Sam Cooke’s “A Change is Gonna Come” and Curtis Mayfield’s “People Get Ready” were written in the mold of spirituals and freedom songs, as was much of the work of Aretha Franklin and others. That this music became the soundtrack of the civil rights movement was understood by the Stones well before 1971, and other selections on Sticky Fingers, like the Otis Redding-inspired “I’ve Got the Blues,” with its signature Stax 6/8 meter, crisp rhythmic shots, “sad” doppler-effect horns, shift to the minor subdominant key for Billy Preston’s organ solo, and “pleading” outro, are homages to the classic R&B tradition.22 Jagger is no Otis Redding, to be sure. But this is no longer a mere cover, as on the early Stones albums, but a new song executed with the authenticity, techniques, and above all performance of the classic R&B tradition.

Equally attractive to the Stones in “You Gotta Move” is the Lord’s egalitarian judgement: “You may be high/You may be low/You may be rich, child/You may be poor/But when the Lord gets ready/You gotta move.” It is God who decides when your time is up, and you can’t pay for your seat in heaven as did the corrupt “kings and queens” during the Great Schism who “fought for decades/for the Gods they made” referenced in “Sympathy for the Devil.” But the most interesting part of the song is the theatrical setting they construct for it. Where McDowell’s version is rendered in the venerable Delta manner of a solo guitarist singing the blues, the Stones make the song into a Salvation Army funeral procession marching down Main Street of Small Town, USA. With McDowell’s original riffs in tow, played here on a twelve-string, improvised harmonies are added on the spot, as are other, spontaneous vocalizations. As the song – and the procession – progresses, more and more instruments are added: A bass drum and clapped hi-hat provide the slow beat of the funeral march as it makes its way, along with the wail of Mick Taylor’s electric slide parts (on a vintage 1954 Telecaster, no less) that bring to mind the lacrimose emotions of witnesses to the funeral.

Another excellent example of a staged song drawing on historical references is “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” (SF), a loud retelling of the troubadour alba in which the exiled poet arrives at the foot of the castle tower for his rendezvous at dawn with his lover. Here, however, he is outside the house trying to smash his way in, weaponized by one of the highest-caliber riffs in Richards’ arsenal coupled with Jagger’s six-beat window- and door-pounding refrain: “Can’t you hear me KNOCK-ing?” With the song’s long, suggestive instrumental coda of solos by Mick Taylor and saxophonist Bobby Keys – at times rhythmic and funky, elsewhere bluesy and dreamy – it becomes clear that our troubadour succeeded in entering through the window … and stayed awhile.

The final, and most creative example of the dramatic, historical settings the Stones can mount of a Delta acoustic blues is with their staging of Robert Johnson’s “Love in Vain Blues,” a song recorded twice by Johnson in his only recording session in 1937. Johnson’s original, like all of his surviving recorded works, features only him singing and playing. After a short introduction and characteristic chromatic turnaround, Johnson sings three verses without an instrumental break (which he rarely takes on these recordings anyway), followed by a final verse that is vocalized. His guitar accompaniment draws heavily from country blues traditions, with the chord shapes and fingerpicking style, as well as the accented “walking” tempo, emphasizing a light shuffle beat along with a percussive accompaniment achieved through his right-hand strumming and muting technique. The harmonies do not stray from a conventional I–IV–I–V blues scheme, and overall it is one of the most restrained songs, technically and vocally, of Johnson’s recorded output. His vocal delivery, perhaps because of the sorrow implicit in the lyrics, is not, like many of his other works, prone to extremes of pitch, shouting, or the use of different “voices.” In all, it is a beautiful though sedate song by Johnson, showing off his more lyrical rather than demonic side.

The Rolling Stones make the song into something much different, enhancing it dramatically on many levels. While retaining essential features of Johnson’s original, they incorporate country, R&B, and even classical influences, creating a small staged piece of musical theater to evoke the images of travel, loss, and sorrow embedded in the lyrics. Johnson’s words are some of the most beautiful in his output, and there is reason to believe that they are autobiographical. In John Hammond Jr.’s 1991 documentary The Search for Robert Johnson (UK, Iambic Productions), among several informants who had been in supposed contact with Robert Johnson, Hammond interviews an elderly woman named Willie Mae Powell, who stated that she was Johnson’s girlfriend in the 1930s. She must be the “Willie Mae” whose name one can hear Johnson sing off-mic in the final vocalization verse of the recording.

The song opens in the first person with Johnson, carrying a suitcase, following his girlfriend to the train station. Is it her bag that she will take with her when she boards the train, or is it his suitcase because he intends to follow her? We don’t know. The second verse opens with the train arriving into the station, and Johnson, sensing that this may be his last chance to patch things up, “looks her [straight] in the eye.” Concluding the verse with this line, but offering no resolution, Johnson brings us to the emotional climax of the song within an imagined clamor of steel and brakes as the train stops. In the final texted verse, it is Johnson who stands alone on the platform watching the train depart from the station, taking account of the two lights of the caboose, one blue, the other red, fading into the distance. The verse ends with Johnson musing that the blue light was “my blues” but the “red light was my mind.” The final, untexted, verse featuring Johnson vocalizing (and moaning the name “Willie Mae”) thus achieves significance as the narrator weeping, shouting, or otherwise emotionally distraught and unable to speak. The whole story, all told in only six individual lines, exemplifies the power of the blues lyric and its well-known themes of travel and loss.

For the Stones, the sentimentality of the verse, its ambiguity, and the rural imagery all inspired a country approach to the piece. Like Johnson, they begin with an introduction on guitar, but instead of the 2/4 shuffle rhythm of Johnson’s original, Richards shifts the tempo to a 6/8 rhythm, like a classic R&B ballad, though in this case tilting more towards country music. In addition, his introduction moves beyond the three chords of Johnson’s conventional twelve-bar blues setting by adding a minor vi chord before the turnaround (the Stones’ version is up a minor third). The addition of the vi chord is a stroke of genius (the progression actually relates to a standard country two-beat scheme of I–vi–IV–V–I), that opens a window “outside” the standard twelve-bar I–IV–V–I progression, similar to the way “Wild Horses” (SF) begins on an “unexpected” B-minor chord in the key of G. As verse one begins, using just guitars and voice, we begin to hear the distant train whistles as played on a slide guitar by Keith Richards. The train’s arrival into the station in verse two is captured musically by the entrance of the rhythm section, while the train whistles (slide guitar) get louder and more frequent. The Stones’ penchant for theatricality is no more apparent than in what happens next: Interrupting the second and third verses, they add an instrumental verse featuring a mandolin solo, played by Ry Cooder, with Jagger singing verse snippets in the background. Although this section is basically instrumental, it provides a crucial explanation to the story. The mandolin is traditionally related to serenades and balcony scenes in Italian opera and usually played by the male lover or seducer: In the seduction aria, “Deh vieni alla finestra” in Mozart’s Don Giovanni, for example, the Don accompanies himself on mandolin (though modern productions usually have someone in the orchestra to play it). Its use here, in the train station, at the point where Johnson’s lover is about to board the train, is a clever adoption of an historical tradition, and it further carves out dramatic action in the absence of words. In the third verse, the full band, including mandolin, accompanies Jagger, who alters a few words (“blues” to “baby”), and the final vocalized verse concludes with a departing train whistle in the distance.

***

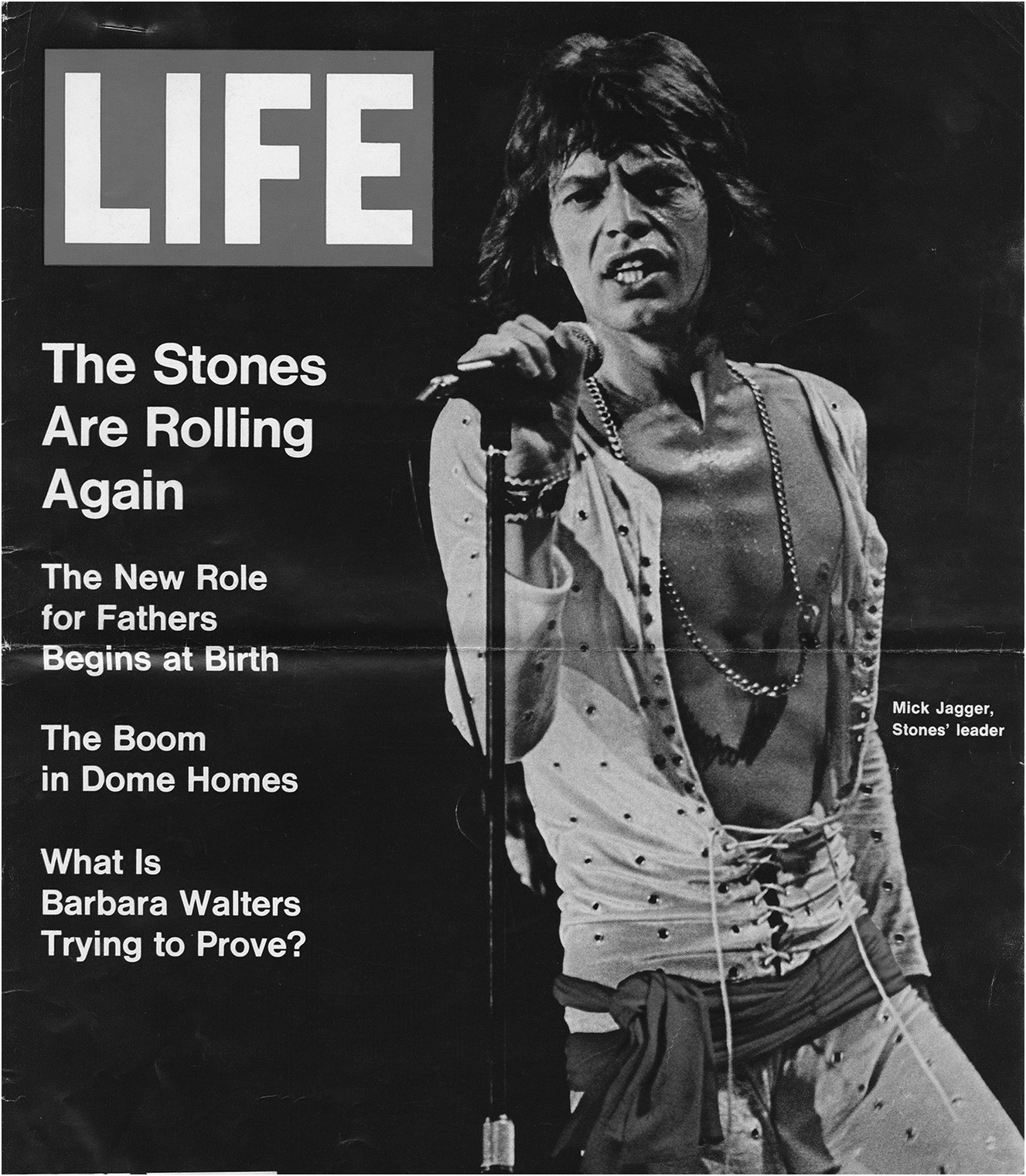

By 1973 the group had reached the end of their exile, their narrative of travel, distance, and plurality of voices singularized into language of the city. Their next album, Goats Head Soup, recorded back at Olympic Studios in London, revealed fissures that became increasingly visible over the next decade. “There was just this feeling through Goats Head Soup that the whole thing was falling to pieces,” recounted producer and drummer Jimmy Miller; “It was no longer Mick and Keith’s song – it was Mick’s song or Keith’s song.”23 The 1972 tour barreled across America – Jagger in a jumpsuit and on the cover of Life (see Figure 4.3), doing anything and having everything – the basement sessions and their exilic voices that were made far away in Nellcôte now being sung to thousands of fans. The tour exhausted the conceptual period of exile for the Stones; the coarseness around the edges of the tour, as documented in Cocksucker Blues, now giving a preview of the group’s next phase, in which the landscape of New York City emerges in both theme and sound. The new album initiated a distinct urban period, as the Stones moved from the stories of exile and the redemption of gospel to an often vulgar and more immediate commentary of urban America and its decadence. Wah-wah pedals, increased guitar distortion, the sounds of Leslies, phase shifters, electric clavinet, and blasphemous takes on the innocence of ’50s rock (“Star Star”) are the new sonic expressions for songs about street shootings, overdoses, and groupies “givin’ head to Steve McQueen.”24 The New York of Some Girls was coming into focus, while the memories of California – the metaphor for paradise in Mick Taylor’s elegiac song, “Winter,” that closes Goats Head Soup – receded into the distance.

Figure 4.3 Cover of Life magazine (July 14, 1972) published during the 1972 tour.