Fashioning identity has always been at the heart of the Rolling Stones’ music and mystique. From their origins as white English teenagers delving as deeply into black American rhythm and blues as any band in Britain (or the States, for that matter) at the time, to their post-sixties forays into glam rock, reggae, disco, and other diversions, they rode into the twenty-first century as a self-defining “classic,” parlaying their status as one of the most accomplished and longest-lasting bands of the rock era into a self-sustaining mega act. Through it all, the initial connection to the blues remains the stylistic marker to which they are most often associated, an influence that has come full circle with their recent Grammy Award-winning album of blues covers, Blue and Lonesome of 2016. As they came to public attention, the overtly African-American implications of the blues provided the Stones with an edgy cultural distinction. To be sure, other British invaders built their sound on a foundation of blues artists from the 1930s through the early 1960s, but as the Stones rose to prominence among such acts, they were drawn into a binary relationship with the Beatles, whose style was more obviously eclectic and whose identity was driven by the commercial agenda of their manager Brian Epstein. This proved especially true in the States when each group arrived for tours in 1964. It is no surprise, for example, that when the Beatles had a few days off on their initial visit to the USA in February, 1964, they remained in Miami (where they made their second appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show) to take in nightclub acts at the Deauville Hotel or fishing and riding speed boats around Miami harbor, whereas the Stones took advantage of a five-day gap in their eight-city, cross-country tour to fly to Chicago to record new songs at Chess Studios – to them, a virtual R&B Valhalla. And while they jammed there with heroes like Muddy Waters, Chuck Berry, and Ray Charles, the Beatles’ only close contact with a black cultural figure came in a light-hearted photo-op with Muhammad Ali (then Cassius Clay), who was in Miami training for a title fight.

Painting the Stones “black” and the Beatles “not black” is, of course, overly simplistic to the point of being misleading. The Beatles incorporated plenty of R&B (and more still, Tamla Motown) influences into their version of the “Merseybeat” sound. But like many other influences, it is a skillful amalgamation with a wide variety of musical styles, from pre-war Music Hall tunefulness and Sun Records rockabilly, to the Bakersfield twang of Buck Owens. The Bakersfield-influenced “I Don’t Want to Spoil the Party,” recorded and released in September of 1964, predates their overt nod to Owens with the cover of “Act Naturally” in 1965. By the same token, the Stones’ cultivation of the black roots styles dug up a host of musical idioms that are tangled up in the blues. Once one travels back beyond the post-war style shifts occasioned by the introduction of the electric guitar, it becomes harder to draw distinct lines between the rural blues and white folk styles. That admixture did not surface much in the Stones’ early albums, but Beggars Banquet in 1968 saw a turn towards acoustic instruments, in the aftermath of ever trippier tracks during the preceding year. Keith Richards remarked:

There was a lot of country and blues on Beggars Banquet: “No Expectations,” “Dear Doctor,” even “Jigsaw Puzzle.” “Parachute Woman,” “Prodigal Son,” “Stray Cat Blues,” “Factory Girl,” they’re all either blues or folk music … We had barely explored the stuff where we’d come from or that had turned us on. The “Dear Doctor”s and “Country Honk”s and “Love in Vain” were, in a way catch-up, things we had to do. The mixture of black and white American music had plenty of space to be explored.1

The blues half of this equation was quickly recognized as a reboot for the group, returning to their “roots.” But the same impulse also spawned a number of country tracks across Beggars Banquet and the succeeding albums through the 1970s, a group of songs that form a distinct subset in the Stones’ songbook.

The group’s early blues covers and originals grew consistently from the electrified R&B of the 1950s. But when the Stones turned to country, they presented a far more variegated picture of an American style that (rightly or wrongly) can be seen as separate from the black musical influence that was so bound up with their own musical identity up to this point. A number of factors led to the heterogeneity of the Stones’ country songs; but, more so than the relatively specific locales – Chicago, the Delta, Texas – that the blues represented to them, the diversity in their country output allows these songs to plot a road map representing the geographic sweep of America that the label “country music” covers. Moreover, while the return to the blues in 1968–72 was marked most strongly by the push back beyond the fifties R&B that had been the Stones’ earlier inspiration (covers of Muddy Waters, Jimmy Reed, Chuck Berry, Howlin’ Wolf, and others on earlier LPs were replaced by ones of Robert Johnson, Fred McDowell, and Robert Wilkins), their foray into country embraced similarly retro styles but also up-to-date country-rock syntheses, reflecting the wide range of the Stones’ country influences.

Country Learnin’

Preceding any outside influences, members of the band each brought their own familiarity with country music to the table. Jagger claimed that he and Keith Richards had listened to, written, and recorded country music long before Beggars Banquet:

As far as country music was concerned, we used to play country songs, but we’d never record them – or we recorded them but never released them. Keith and I had been playing Johnny Cash records and listening to the Everly Brothers – who were so country – since we were kids. I used to love country music even before I met Keith. I loved George Jones and really fast, shit-kicking country music, though I didn’t really like the maudlin songs too much.2

A penchant for country music would not make Jagger or Richards unique among sixties British rockers (the Beatles had been penning Bakersfield-influenced songs since 1964: “I’m a Loser,” “I Don’t Want to Spoil the Party”), but they had displayed only a little interest before Beggars Banquet. At least, not on any released material. On a trio of demo recordings from the summer of 1964, Stones manager Andrew Oldham enlisted a number of outside players (members of the “Oldham Orchestra”), including several guitarists who were already highly respected (Big Jim Sullivan) or destined to become major figures (Jimmy Page and John McLaughlin). Someone among them played pedal steel guitar to lend a country tinge to the songs.3 These tracks only surfaced a decade later on the UK LP Metamorphosis (only “Heart of Stone” appeared on the US release of the LP), but demonstrate an early curiosity about country sounds, at least on the part of Oldham: Mick Jagger may have been the only member of the band participating in one or more of these recordings. Of the songs in question (all Jaggers/Richards compositions), “Some Things Just Stick in Your Mind,” “We’re Wasting Time,” and “Heart of Stone,” only the latter was rerecorded and released a few months later as a single in the USA, with the pedal steel replaced by Keith Richards’ baritone guitar.

It would take a while for the group to air their country interests. A live cover of Hank Snow’s “Movin’ On” from late 1965 owes more to Ray Charles’ 1959 cover than to the original. Months later, on Aftermath, the Jagger/Richards song “High and Dry” does more to validate Jagger’s claims. As a country song it is a hodgepodge: Richards’ overdubbed acoustic guitars are as much a bow to folk music as country, while the relatively loose ensemble conjures an earlier era in country recordings. As in the more frequently referenced country songs in the Stones’ output (discussed below), neither Bill Wyman nor Charlie Watts display much affinity for country rhythms. The latter’s ringing hi-hat serves to avoid a rock back-beat, but fails to capture the terse simplicity of 1960s country drumming. “I love Hank Williams and Bob Dylan’s Nashville Skyline, but the whole Nashville thing I’m not that enamoured of,” Watts commented years later. “I can enjoy Buck Owens and Bob Wills’s swing band and George Jones, but it’s not something I’m particularly good at.”4 At the same time, Wyman’s repeated notes in “High and Dry” oversimplify the root-fifth alternation of a typical country bassline. Both members would grow and adapt in the country songs of the coming years, but the rhythm section helped to mark these numbers as Rolling Stones tunes, no matter how deeply Richards delved into the world of “Three Chords and Truth” (a phrase widely attributed to legendary Nashville songwriter Harlan Howard) or how often Jagger affected a Southern drawl.

On Aftermath, “High and Dry” is one of several forays into new styles for the group, including the quasi-Elizabethan “Lady Jane,” the artsy “I Am Waiting,” and a smattering across the album of a variety of instruments from outside the rock band line-up.5 It shows less an interest in exploring country music than in exploring various styles beyond the band’s core blues sound. That impulse to widen their stylistic horizons led to the nearly obligatory diversion into the Summer of Love, culminating in the least Stones-like Rolling Stones album of the decade, Their Satanic Majesties Request. Though some elements of psychedelia lingered beyond Majesties, 1968 marked the band’s decisive turn, as noted above, back to the blues on Beggars Banquet. By the time the album was released at the end of that year, two critical outside influences had redirected the Stones’ stance toward country music: Gram Parsons and Ry Cooder. Their impact on and interaction with the group could hardly be more different. In May, the group encountered Parsons while he was on tour in the UK during his brief stint with the Byrds (indeed, his initial conversations with Jagger and Richards about the band’s upcoming tour of Apartheid South Africa convinced Parsons to drop out of the Byrds).

Although Parsons’ influence was more personal and more widely acknowledged, Cooder’s contribution must be considered for an understanding of what “country” meant to the Stones in the 1970s. Cooder was brought over from the USA by Jack Nitzsche in June of 1968 to jam with the Stones, in order to percolate ideas for a film project (The Performers) back in Los Angeles, for which Cooder was to write the soundtrack. While his most notable impact on the group was turning Richards onto the five-string open-G tuning (with which Richards claims he was already experimenting), Cooder also deserves credit for helping to steer the band towards pre-Chicago blues, an era when white and black “country” music were often indistinguishable, when Lesley Riddle could collaborate with the Carter family and Woody Guthrie could sing alongside Lead Belly.6 A number of the Stones’ songs, from Beggars Banquet onward, tap this earthier, organic vein of country music: “Sweet Virginia” from Exile on Main Street, and “No Expectations” from Beggars Banquet, for example. Nowadays, we might not think to label those songs country, but the concept of “country rock” was broad enough at the end of the sixties to encompass the loose Americana aura of The Band (touted on the cover of Time Magazine as “The New Sound of Country Rock”), the straight-ahead honky-tonk of the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo, and the tight-harmony and steel guitar-laden styles coming out of southern California from Poco, The New Riders of the Purple Sage, and others. By contrast, Cooder was himself a product of the late-sixties LA music culture, and his own albums around this time illustrate his interest in everything that scene had to offer, not just the emerging sound of hippie-twang. Through Nitzsche, a record company insider with his own eclectic tastes, Cooder was in contact with other roots-seekers in LA: Randy Newman, Leon Russell (who had already played on many recordings there as a member of the studio band, the Wrecking Crew), and Lowell George, to name a few.7 Some of that mix probably was conveyed to the Stones in London. Although they had little (documented) contact with those artists, echoes of all the aforementioned can be heard throughout their string of albums from 1968–72, and Russell actually first recorded the Stones’ gospel-influenced song “Shine a Light” a few years before it appeared on Exile, for his eponymous album of 1970.

Just how much of those influences were directly communicated through Cooder and how much was a matter of a shared musical language is hard to gauge. The relationship between him and the band soured a year later when he was once again brought in by Nitzsche, at the planning stages for the 1969 album Let It Bleed. Although he is credited on “Love in Vain” (mandolin) here, and later on “Sister Morphine” (slide guitar) from Sticky Fingers (1971), Cooder vented in a 1970 Rolling Stone interview about his presence during the Let It Bleed sessions, claiming that his riffs were copied by Richards and formed the core sound of the album:

The Rolling Stones brought me to England under false pretenses. They weren’t playing well and were just messing around the studio … When there’d be a lull in the so-called rehearsals, I’d start to play my guitar. Keith Richards would leave the room immediately and never return. I thought he didn’t like me! But, as I found out later, the tapes would keep rolling …

In the four or five weeks I was there, I must have played everything I know. They got it all down on these tapes. Everything.8

For their part, the Rolling Stones have downplayed Cooder’s influence, allowing only as how he showed Richards many ways to utilize the open G-tuning that became a hallmark of Richards’ playing from that point on.

By contrast, Gram Parsons is often assumed to have given the Stones as much material as Ry Cooder complained that they took from him. Yet unlike Cooder, Parsons never claimed any credit or begrudged the band any bits and pieces they might have borrowed. In part, this speaks to the deep personal connection he felt to the band, and to Richards in particular, who spoke of Parsons as a “long-lost brother.”9 On three stints – the first at Richards’ Redlands estate in the summer of 1968 following Parsons’ decision to abandon the Byrds in July; the second in the fall of 1969 when the Stones took up residence in southern California to complete Let It Bleed and prepare for a US Tour; and the third in the summer of 1971 at Richards’ Villa Nellcôte in the south of France, where the Stones were recording what would become Exile – Parsons and Richards bonded in lengthy explorations of the country canon, with Parsons bringing Richards’ youthful familiarity with honky-tonk up to date. His Southern bona fides notwithstanding, Parsons himself had only warmed to country music when he arrived in Cambridge, Massachusetts to attend Harvard in the fall of 1965. During his single (mostly truant) semester there, he fell in with a band that would move to the Bronx within a year and become the International Submarine Band. ISB guitarist John Nuese takes credit for immersing Parsons, along with the rest of the band, in the Bakersfield sounds of Merle Haggard and Buck Owens: “Gram knew nothing about what was going on with country music in the sixties and he quickly became an avid fan … He took on that music and made it his own.”10 Neuse recounts long nights singing through material that jibe with Parsons’ later marathon singing sessions with Richards as the latter recalls them:11

[W]e played music without stopping. Sat around the piano or with guitars and went through the country songbook. Plus some blues and a few ideas on top. Gram taught me country music – how it worked, the difference between the Bakersfield style and the Nashville style. He played it all on piano – Merle Haggard, “Sing Me Back Home,” George Jones, Hank Williams … Some of the seeds he planted in the country music area are still with me, which is why I can record a duet with George Jones with no compunction at all.12

By the time Parsons met Richards, he had cajoled the International Submarine Band into moving to Los Angeles, where they disbanded in 1968, shortly before Parsons and Neuse scored a record deal with Lee Hazelwood and produced one album (Safe at Home) with a hastily assembled new line-up. Over the next five years of his short life (he died of a drug overdose in 1973 at the age of twenty-six), Parsons established a pattern of gathering other musicians around him, only to lose interest, focus, or both, or to try the patience of his collaborators through his unreliability, which was largely fueled by his substance abuse. His fame and influence (almost entirely posthumous) are wildly disproportionate to the amount of music he wrote and recorded, and speak more to his vision of “Cosmic American Music,” in which the various strands of late 1960s popular music – country, R&B, and rock – could be harmoniously blended. Parsons recognized this quality in the Stones as he encountered them in 1968. Prompted by an interviewer’s leading comment (“‘Wild Horses’ is very unlike most of their writing”), Parsons calls the song “a logical combination between our music and their music.” As Parsons tried to explain in his ensuing remarks, the Stones had sent the original masters to Parsons’ band, the Flying Burrito Brothers, who actually released the first version of the song.13 This remark touches on a subtle but critical facet of his relationship with the Rolling Stones and on the very nature of the Stones’ country songs. For all the hours Parsons and Richards spent drilling down into the country songbook, from Hank Williams to Merle Haggard, the idea of replicating the style of those songs and the sound of those recordings was not Parsons’ agenda during the years he was close to the Stones. Rather, he was after a synthesis of various strands of American music, and it is that vision that ultimately influenced Richards and his bandmates. That, however, leaves a more nebulous mark, which makes it hard to pin down Parsons’ impact, on the one hand, and easy to imagine it everywhere, on the other. Richards says as much: “That country influence came through in the Stones. You can hear it in ‘Dead Flowers,’ ‘Torn and Frayed,’ ‘Sweet Virginia,’ and ‘Wild Horses,’ which we gave to Gram to put on the Flying Burrito Brothers record Burrito Deluxe before we put it out ourselves.”14

The fact that those four songs come across as quite different from one another stylistically speaks volumes about the Stones’ approach to country stylings in their own music. Whereas their early focus on rock and roll and R&B provided some unity to their sound through 1966, the diversity of their country-influenced numbers reflects the wide range of their country inspirations and the relative novelty of the genre for the group. Moreover, since the country influence of Ry Cooder leaned more towards what we would nowadays label “roots” music, a mix of vernacular styles from which both country and the blues would emerge, and because Gram Parsons – for all of the Nashville and Bakersfield tutorials he shared with Richards – interacted with the group while pursuing his own path of blending country, blues, and rock under the banner of Cosmic American Music, it is not surprising that Stones Country is an itinerary of disparate places that don’t connect along one road; there is no country route to replace the Highway 61 of the Stones’ blues background.

What follows, then, is a tour of an imaginary musical landscape. Each of the songs discussed below has to be taken on its own merits, considered for its unique representation of country within the Rolling Stones’ core style. To help navigate them, however, I have grouped some songs together, leading from those older primordial mixtures of country and blues (The Old Country), through numbers that wear country on their sleeve – maybe a little too overtly (Deep Country), to songs that incorporate country elements in a decidedly modern manner to produce something entirely at home at the turn of the decade (Stones Country). This list hardly exhausts the songs that display country influence – much less the influence of Parsons and Cooder – but represents rather a survey of significant landmarks. Well-known examples (“Wild Horses,” “Country Honk,” “Torn and Frayed”) will be bypassed in order to focus on a handful of songs that raise particular issues of the Rolling Stones’ engagement with country music styles.

The Old Country: “No Expectations” and “Sweet Virginia”

One of the obstacles to defining Stones Country is the inherent blending of country and blues once one looks back beyond the honky-tonk era of Hank Williams and Ernest Tubb. Country music was only defined as a type in the wake of the “Big Bang” at Bristol in 1927, when Ralph Peer recorded Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family (along with numerous other aspiring regional acts) for the Victor Talking Machine Company in the first week of August. Although many white Appalachian string bands were recorded in the 1920s and early 1930s, their repertoire and playing styles often overlapped considerably with African-American blues artists (their counterparts in the “race” catalogues of Victor and other early recording companies). No one better illustrates the cross-fertilization between hillbilly music and the blues (and Tin Pan Alley, for that matter) than Rodgers himself, whose “Blue Yodel” series of songs all follow the twelve-bar blues form while borrowing vocal inflections and lyrical clichés from the black side of the “race records” divide.

At least two Stones songs from the cluster of albums between 1968 and 1972 dwell in that interstice. “No Expectations” from Beggars Banquet (1968) would seem to derive from straight blues material. Commentators frequently point to Reverend Gary Davis’ “Meet Me at the Station,” and Robert Johnson’s “Love in Vain” – which Richards claims the band had only discovered in 1967. “No Expectations” has the distinction of being the last recording to include Brian Jones, whose Hawaiian-style acoustic slide guitar quickly conjures the country blues of the 1930s. But if the lyrics vaguely tap various stock lines from early rural blues recordings (for example, “I followed her to the station,” from Johnson’s “Love in Vain,” becomes “Take me to the station” in the Stones’ hands), details in the musical setting decenter the song’s blues identity. Most notably, the verses alternate three times between a pair of chords (A major and E major), launching each iteration with a softly altered version of A major as Keith Richards lets a note from the other chord in the pair ring through in his part. Pre-war guitarists certainly may have added notes to these chords, but they would be flatted and would have added a bite, not the melancholy tone struck here. Jones’ limpid slide guitar lines do little to sharpen the effect. The result is neither blues, nor the rootsy early country of Jimmie Rodgers, Charlie Poole, and the like, but rather a comfortable blending of the two that pays homage to their interconnectedness, while injecting just enough poetry (“Our love was like the water/That splashes on a stone/Our love is like our music/It’s here, and then it’s gone”) to render the song modern. Like some other songs in Stones Country, the country element in “No Expectations” is mostly latent, as evidenced by the stronger presence of country idioms in covers that range from bluegrass renditions by John Hartford and Bill Keith, to outlaw statements from Johnny Cash and Waylon Jennings, and a retro-roots version by Nancy Griffith and Son Volt.

“Sweet Virginia” (Exile on Main Street, 1972) similarly carries more country potential than it realizes (although in this case there is no bank of country covers to plead its case). The opening of the song seems as generically “country”-sounding as a song could get in 1972. Richards’ unadorned, jingle-jangle guitar could derive from any era in country music up to that time. But – as a country song – the track quickly loses its moorings. Although we could still hear “Sweet Virginia” as traditional country of one sort or another when Mick Jagger’s harmonica enters five bars in, followed in short order by Mick Taylor’s lead acoustic guitar, things start to take a right-angle turn when the drums and bass enter (0:47). A country vibe is maintained through the first verse but dissipates as the piano (Ian Stewart) and saxophone (Bobby Keys) enter with the chorus, and the entire ensemble morphs into something more like a Bayou blues jam than an Appalachian string band. In other words, “Sweet Virginia” crosses the same blurry boundary from country to blues that “No Expectations” had traversed, only here it occurs sequentially rather than simultaneously. Lost in the raucous romp into which the song extends from its mid-point on is a perfectly plausible modern country, 2/4 beat. To be sure, Charlie Watts’ snare shots are raspier and looser than one would expect from the average Nashville or Bakersfield drummer of the day (compare, for example, the drumming on Merle Haggard’s nearly contemporaneous [1971] cover of Roger Miller’s “Train of Life”); they might sound more at home in Memphis or New Orleans. Nevertheless, the underlying rhythm to Watts’ pattern can be traced back to any number of early country songs – again, Jimmie Rodgers provides a ready example in “Waiting for a Train,” in which the boom-chick of Watts’ pattern is ably represented by Rodgers’ guitar. If the drumming on “Sweet Virginia” leans towards blues or something more soulful than we tend to associate with country, it is merely a reminder of how interconnected country’s origins are with other “roots” genres.

Acknowledging the crossover from an ostensibly country opening into something “other” also helps explain the frequent suggestions (beginning with the members of the Rolling Stones themselves) that “Sweet Virginia” reflects the influence of Gram Parsons.15 On the surface this is a curious claim, as there are no Parsons songs that come close to sounding like this. Only “Do You Know How it Feels,” included on both the International Submarine Band’s Safe at Home and Burrito’s Gilded Palace of Sin, has any resemblance, sharing the underlying drum pattern (though much closer to Jimmie Rodgers than Charlie Watts). But that lack of a specific match serves as a reminder that Parsons’ influence was as much a concept as a sound. In this case, the blending of country and soul leads backwards more than forwards, and thus Parsons’ Cosmic American Music is not the best label for what the Stones achieve in “Sweet Virginia”: we are still in the Old Country. As much as Parsons’ idea was predicated on the common roots from which country, R&B, and rock and roll had sprung, he was aiming towards a newer synthesis. Stones tunes making up a second group from the period in question fall short of that ideal by seizing solely on the country explorations that Parsons and Richards undertook at Redlands and Nellcôte. Perhaps it is no surprise that these songs feel less like Rolling Stones songs, and more like role-playing or parody.

Deep Country: “Dear Doctor” and “Far Away Eyes”

For all of Keith Richards’ and Mick Jagger’s legitimate interest in and knowledge of country before encountering Ry Cooder and Gram Parsons, they defined themselves first as Rolling Stones – as asserted at the beginning of the chapter – through the passion for R&B and blues that they shared with Brian Jones. With a nod to the Animals, the Stones were the “blackest” of the British Invasion bands. Reflecting on blackness as an attitude and ominous demeanor (rather than race) after Altamont, Robert Christgau posited that whereas the Stones and the Beatles shared an appreciation for the “tough, joyous physicality of their Afro-American music,” the Stones “came from a darker angrier place.” But Christgau takes issue with the idea that Jagger was trying to be black:

Early analyses of their music veered between two poles – Jagger was either a great blues singer or a soulless thief – and both were wrong. Like so many extraordinary voices, Jagger’s defied description by contradicting itself. It was liquescent and nasal, full-throated and whiny. But it was not what Tom Wolfe once called it, “the voice of a bull Negro,” nor did it aspire to be. It was simply the voice of a white boy who loved the way black men sang – Jagger used to name Wilson Pickett as his favorite vocalist – but who had come to terms with not being black himself … His style was an audacious revelation. It was not weaker than black singing, just different, and the difference always involved directness of feeling.16

Christgau is speaking specifically of Jagger’s voice. While the adoption of black musical style might have harnessed the frustration of British youth in the post-war era, Jagger did not need to adopt black vocal mannerisms to get the point across. His verbal articulation may have been just as muddy as that of the Chicago bluesmen he studied as a teenager (Jagger claimed he would put his ear directly up to his record player’s speaker in order to decipher the lyrics of his favorite songs), but as Christgau avers, his was a different voice whose blurred diction was founded on “directness of feeling,” not verbal blackface.17 One glaring exception to this rule is Jagger’s rendition of Robert Wilkins’ “Prodigal Son” (a song that draws its refrain from Wilkins’ “That’s No Way to Get Along”) on Beggars Banquet. As the only song on that LP not penned by Jagger and Richards, Jagger could be heard to pay homage to Wilkins through his affected delivery.

Jagger’s vocal style in the Rolling Stones’ most overtly country songs is starkly different. In contrast with the avoidance of a black voice in the Stones’ generic rock style and blues numbers, Jagger falls into a mannered drawl in the two songs I have grouped under Deep Country. In both cases, his voice is only the most overt projection of the Stones’ parody of a specific country song type. Rather than absorbing country as a new facet of their identity, as one could argue they had in “Sweet Virginia,” these songs find the band holding country at arm’s length, something not only beyond their identity, but far enough removed from it to be an object of ridicule. In Jagger’s words: “The country songs, like ‘Factory Girl’ or ‘Dear Doctor’ on Beggars Banquet were really pastiche. There’s a sense of humor in country music, anyway, a way of looking at life in a humorous kind of way – and I think we were just acknowledging that element of the music.”18 “Dear Doctor” is nothing if not comedic. However, the humor lies not in the nature of the country music it parodies (per Jagger’s assertion), but rather in the exaggerated manner in which the Stones play up the stereotypes and clichés of the genre. At its core, “Dear Doctor” is a country waltz – a type with a rich tradition going back at least to the Carter Family. More often than not, country waltzes are wistful, either retelling a sad tale or recalling a tender moment. This offers a perfect context for the singer’s tale of woe, driven to drink “like a sponge” as he is pushed by his mother to marry a “bow-legged sow” – a far cry from the lost loves of Pee Wee King’s “Tennessee Waltz,” Bill Monroe’s “Kentucky Waltz,” Webb Pierce’s “The Last Waltz,” and from a few years later (1974), “As Soon As I Hang Up the Phone,” by Loretta Lynn and Conway Twitty. Jagger makes sure to let the listener know they are intentionally missing the emotional mark of their models by tagging the rhyming words “jar,” “sour,” and “hour” (a little less so on “heart”). Richards’ harmony vocal doubles down on the spoof at those moments, slightly overshooting his note every time. The farcical falsetto with which Jagger delivers the lines in the missing bride’s letter to her jilted fiancé in the last verse ensures that no one will miss the send-up. At best, the Stones are providing some relief on an otherwise heavy album. More likely though, they are displaying their own discomfort: with the maudlin nature of those legitimate country waltzes, the oh-so-white character of the straight country-waltz beat, and the idea of representing straight country music in one of their own songs. The song was recorded in May of 1968, before Richards embarked on the first of his extended country music deep dives with Parsons, so the aura that country would soon take on for Richards and the group had not yet materialized.

That said, Jagger and Richards knew how a country song works, and they dialed up several stereotypical features of the genre in “Dear Doctor.” For example, the reiterative melodic beginning of the chorus (“Oh help me”/“Dear doctor”/“I’m damaged”) mimics a similar melodic profile in such country waltzes as Hank Williams’ “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” and “Tennessee Waltz” (where the pattern breaks with the third iteration, moving the repeated phrase [“I was dancing”/“with my darling”] up an octave [“to the Tennessee Waltz”]). Harmonically, the Stones seize on a tendency for country waltzes to move directly from their opening I chord to firmly establish a higher one on IV (in the case of “Dear Doctor,” the move is from the tonic D major harmony to a G major harmony). That is hardly an unusual move, but it is ubiquitous in well-known country waltzes (“Tennessee Waltz,” “Alabama Waltz,” “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” “Blue Moon of Kentucky,” “Waltz of the Angels”). Finally, the climbing dissonant harmonies that land in a higher range (from 1:32–1:39) tap a category of country songs that shift key for a portion of the song, following the same interval of a fourth, now at the level of key (not simply harmony). Unlike their genuine models (Willie Nelson’s “Family Bible,” Buck Owens’ “Sweet Rosie Jones,” Merle Haggard’s “House of Memories,” Conway Twitty’s “Next in Line”), in which the shift occurs briefly within the verse of the song or as a bridge, “Dear Doctor” never comes back down to its original key, and ends with the chromatic, dissonant climb: another comical gesture, perhaps.

Humor at the expense of country stylings in “Dear Doctor” is not subtle, but neither is it over the top. Partly that is because the basic make-up of the band is present. Bill Wyman strips down his bass line as one would expect of a country player, but he approaches the chord roots at the downbeat of each measure from a minor third above or a second below – sticking to rock conventions and belying any Nashville or Bakersfield authenticity. Accordingly, Richards’ acoustic guitar parts are still bluesy enough to remind us that this is not a country band, and Jagger delivers the lyrics with an unaffected British accent for enough of the song (when he isn’t exaggerating his “R”s) that we have no trouble making sense of it as part of Beggars Banquet.

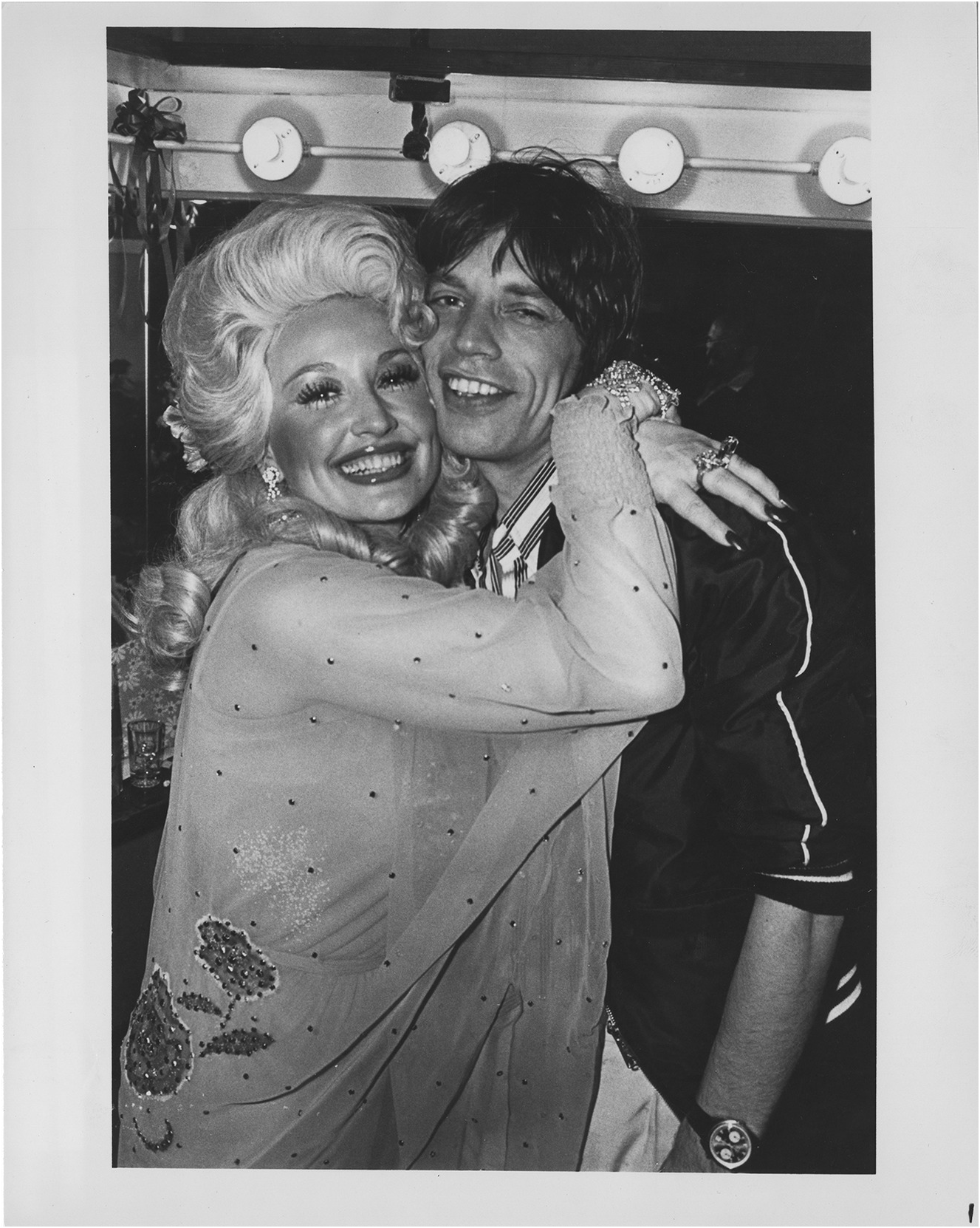

Through the run of albums from Beggars Banquet to Exile on Main Street, any further forays into country would be delivered more deftly (and we will consider some of those cuts below). But the country parody returned with a bang on Some Girls in 1978. After a few LPs following Exile that garnered mixed reviews for their musical content as well as for the Stones’ apparent lack of direction, Some Girls was generally received as a return to form and, more importantly, relevance.19 The album proved that the group could still provoke a response, from its cover featuring the band members in drag (replacing the real faces of some celebrities who insisted their faces be removed), to the gendered and racial offenses of the title track.20 At the same time, Some Girls also demonstrated that the Stones could adjust to current pop music trends: disco with “Miss You”; new wave with “Shattered”; and punk with “Lies.” The other clear “style” piece on the LP is “Far Away Eyes,” which goes far beyond “Dear Doctor” in evoking the sound and flavor of country music. Of course, a lot had changed in country music and with the Rolling Stones during the intervening decade (see Figure 7.1). In 1977, the top of the country charts was in mid stream, represented on the one hand by the classic styles of Conway Twitty, Loretta Lynn, Waylon Jennings, and Charley Pride, and on the other by the forerunners of the soon-to-crest Urban Cowboy movement: a revamped Dolly Parton, Ronnie Millsap, Glen Campbell, and Crystal Gale. (Ironically, much of the changing sound of country music by the late 1970s was a reaction to the blending of country and rock that Gram Parsons had helped initiate in the late 1960s.)

Figure 7.1 Mick Jagger and Dolly Parton following her performance at the Bottom Line, New York, May 14, 1977.

For their part, the Stones had moved on from founding member Brian Jones, through Mick Taylor, to Ron Wood, their new guitarist. On “Far Away Eyes” and at least three other tracks that were recorded for the LP (two only emerging decades later on rereleases of Some Girls) Wood plays pedal steel guitar, the quickest way to mark a track as “country.” Although Wood never developed stellar technique on pedal steel (he added steel tracks to several later songs as well), the playing here is decidedly more in tune and passable than on the 1964 demos mentioned earlier. The bright sound of the steel guitar’s whine is matched by Richards’ brittle Fender Telecaster, a combination that supplied the core of the Bakersfield sound a decade earlier. And unlike the country-influenced tracks at the turn of the 1970s, “Far Away Eyes” features a very passable execution of a laconic country rhythm track from Watts and Wyman. The comparison with the earlier songs from Stones Country is driven home by the strong similarity in musical content and structure with “Sweet Virginia.” Where the earlier track ran amok, spiraling into a swampy blues number, this one maintains the initial country flavor throughout, despite the nearly identical harmonic structure (the chord progression is extremely similar, save for the second chord in each song’s pattern) and formal similarities.

But the straight country delivery in “Far Away Eyes” is overshadowed by the very specific subcategory to which the lyrics assign the song: the country talking-blues. Examples dot the history of country music, from Hank Williams’ preaching songs under the name Luke the Drifter, to numerous examples by Johnny Cash, to the narration songs of Red Sovine, most memorably the ghost-trucker song, “Phantom 309.” The most recent hit in the style also had been a trucking song, C. W. McCall’s 1975 “Convoy.” Jagger uses the built-in hokum of the genre as a license to expand the parody element he had explored in “Dear Doctor.” In place of the hillbilly saga there, Jagger invokes Bakersfield and radio preachers to drench “Far Away Eyes” in country bona fides. And whereas the earlier Stones country songs let an occasional drawn-out “R” punctuate a line, Jagger laces this track with an exaggerated drawl throughout, where rolled “R”s are no longer necessary to put the effect across. The straight country playing behind the vocal allows the joke to stay front and center throughout, as the protagonist recounts running ten straight red lights with God’s blessing (“Thank you Jesus; thank you Lord!”), and the preacher’s exhortation to send ten dollars “to the church of the Sacred Bleeding Heart of Jesus located somewhere in Los Angeles [pronounced Ange-leez], California.”

In a Rolling Stone interview several months after the song was released, Jagger cites the origins of “Far Away Eyes” in the real experience of driving through Bakersfield on a Sunday morning, specifying: “all the country-music radio stations start broadcasting live from L.A. black gospel services.” When prompted by the interviewer (Jonathan Cott), Jagger initially denies the influence of Gram Parsons, but then immediately circles back to him:

JC: I sense a bit of a Gram Parsons feeling on “Faraway Eyes” – country music as transformed through his style, via Buck Owens.

MJ: I knew Gram quite well, and he was one of the few people who really helped me to sing country music – before that, Keith and I used to just copy it off records. I used to play piano with Gram, and on “Faraway Eyes” I’m playing piano, though Keith is actually playing the top part – we added it on after. But I wouldn’t say this song was influenced specifically by Gram. That idea of country music played slightly tongue in cheek – Gram had that in “Drugstore Truck Drivin’ Man,” and we have that sardonic quality, too.21

Since Jagger raises the tongue-in-cheek element, it is hard not to also hear an echo of the last song on the Flying Burrito Brothers’ Gilded Palace of Sin, the Parsons and Chris Hillman original “Hippie Boy,” and from there to trace “Far Away Eyes” back further and more specifically within its genre. In “Hippie Boy,” Parsons’ churchy organ chords and wild piano runs accompany Hillman’s spoken tale (partly based on real events) of intrigue and deception, leading to the death of an innocent hippie at the calamitous 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, ending with a screeching choral allusion to “Peace in the Valley.”22 For Parsons and Hillman, one need look no further than their beloved Louvin Brothers for a precedent. “Satan is Real” (1959) supplies sonic elements (the church organ) to the Burritos’ song while presaging the religious trappings (a preacher’s reply to the call to warn the congregation about the realities of Satan) in the Stones’ later parody. For the Stones, all of this is fodder for a send-up of country music and one of its core values, evangelical religion.

Stones Country: “Dead Flowers”

Ironically, in “Far Away Eyes,” the Rolling Stones sound the most convincingly country when they are distancing themselves from it most strongly. Jagger and Richards back up their various claims of having known and appreciated country music before Cooder and Parsons arrived on the scene, but they don’t want to be tied directly to it. Despite the cachet of numerous country-rockers, “outlaws” (Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, etc.), and progressive singer-songwriters by 1978, the Stones did not feel they could treat country music as simply as the newer styles represented on Some Girls. But they could have. A 2011 CD reissue included eleven previously unreleased tracks, mostly from the original recording sessions for the album from October 1977 through March 1978. Among those (and two from slightly later sessions) are two country covers that might have situated the Stones very differently in relation to country. Their recording of Hank Williams’ classic “You Win Again” uses much the same line-up and basic core sound (with a touch of slap-back echo added) as “Far Away Eyes,” but there is no trace of parody or distance; it is as sympathetic a reading as they gave any of the R&B songs they had ever covered. Jagger injects a heavy dose of blues inflection to the vocals, befitting a serious Rolling Stones track. Most surprising is how deftly Wood handles the pedal steel guitar. Whereas his licks on “Far Away Eyes” were limited (the sort of pedal mashing any guitarist might engage in when dabbling), he strings phrases together on this track passably and he shows more feeling for the idiomatic use of the instrument. Wood also deserves kudos for his pedal steel playing on “Shattered,” which required more imagination since there is nothing remotely country about the song, and thus no models to fall back on. (Nevertheless, he is probably not the first to use pedal steel on a New Wave or punk track; that distinction likely goes to Walt Andrews of Root Boy Slim and the Sex Change Band, whose eponymous LP débuted in June, 1978, but who had been performing in the Washington, D.C. area for a few years before that.) Another cover, “We Had It All,” was captured in the wash of material the Stones recorded in 1978, but included the same line-up heard on Some Girls. Written by established country songwriters Troy Seals and Donnie Fritts, the song had been previously recorded by Waylon Jennings and Dobie Gray (among others); Richards – who, according to Jagger, heard it off the Jennings album Honky Tonk Heroes23 – gives a haunting version singing and accompanying himself on piano. By now, Watts and Wyman have assimilated country rhythm playing and can apply it without the audible eye roll (confirmed by the official music video) that seeps through on “Far Away Eyes.” Whereas the latter could have been taken as an affront by a generation of alt-country artists who would emerge a decade later, Richards’ gripping rendition of “We Had It All,” along with the band’s gritty but subdued instrumental tracks, could have been held up as a road map for later pioneers like Jay Farrar and Ryan Adams. Reversing roles from earlier country-influenced tracks, Watts and Wyman lay down a country beat, and Richards and Wood move beyond that into a place that is neither country, rock, nor blues.

“Dear Doctor” and “Far Away Eyes” demonstrated that the Rolling Stones could never feel at home in Deep Country. They had to maintain their distance by playing the fool; the Stones’ parody of country idioms clearly pegs them as outsiders. However, this is not to say that they couldn’t incorporate country music into their sound, which is why “You Win Again” and “We Had It All” are so important for demonstrating that, by 1978, the Stones had figured out what they could do with country music. Several songs from the core LPs from 1968–72 chronicle their gradual assimilation of country. The high-water mark among these is “Dead Flowers,” recorded in 1969–70 and released in 1971 on Sticky Fingers. Perhaps more than any other track discussed here, “Dead Flowers” is widely recognized as the Stones’ most direct country song, even though it falls short on many country style points. All of the exaggerations of the earlier “Dear Doctor” are toned down and delivered with more finesse, starting with the lyrics. What had been a redneck romance is replaced by an uptown/downtown relationship gone wrong. And whereas the substance of choice in the earlier song was corn whiskey (“She plied me with bourbon so sour”), “Dead Flowers” makes a veiled (albeit thinly) reference to heroin use in the second verse: “I’ll be in my basement room with a needle and a spoon/And another girl to take my pain away.” Indeed, the title of the song itself and its addressee, “Little Susie,” may even allude to heroin. These codenames may be more urban legend than reality: they are mostly discussed in internet chat rooms rather than in any authoritative sources.24 Given the group’s well-publicized troubles with heroin and any number of other controlled substances by this time, “Dead Flowers” brings the story closer to home. It is not autobiographical, however; Jagger and Richards’ lyric locates the protagonists in the South with a reference to “Kentucky Derby Day.”

Just as tellingly, they also tie the song to some heavy Southern class symbolism: the pink Cadillac. As an icon, the pink Cadillac goes back to Elvis Presley. In his 1955 recording of Arthur Gunter’s “Baby, Let’s Play House,” Presley alters Gunter’s first verse:

Elvis changes the opening of the second line to “You may drive a pink Cadillac.” Shortly after recording the song for Sun Records, Presley bought himself a custom pink 1954 Cadillac sedan – the first of several pink cars he would own. Greil Marcus recognizes the pink Cadillac as central to Elvis’ rags-and-resentment-to-riches story, even tying it to some of Jagger’s earlier songs:

The Pink Cadillac was at the heart of the contradiction that powered Elvis’s early music … When he faced his girl in “Baby, Let’s Play House” (like Dylan railing at the heroine of “Like a Rolling Stone,” or Jagger surveying the upper-class women who star in “19th Nervous Breakdown,” “Play with Fire,” and “You Can’t Always Get What You Want”), Elvis sang with contempt for a world that had always excluded him.25

Jagger’s protagonist has contempt less for the social class that separates him from his ex than for her hypocrisy: holding forth with her rich friends while supplying his heroin (she is, after all, the “queen of the underground”). Situating her in her pink Cadillac, in contrast to his heroin-tainted basement room, marks her as a social climber – someone who, like the singer, does not belong with her rich friends. Some, all, or none of this may derive from actual relationships the Stones found themselves in through their rise to stardom in the preceding decade, but all of the dynamics at play (drugs, class conflict, bitter break-ups) are plausible and relatable aspects of the band members’ lives. Right off the bat, then, before even turning one’s attention to the music to which the lyric is set, this is a more legitimate country song than anything the Stones had done before, since it relates a “real” story.

As with the lyrics, the excesses of “Dear Doctor” are tamed in the musical setting of “Dead Flowers.” Richards’ sprawling acoustic guitar parts are replaced by a more organized trio of Jagger on acoustic and Richards and Taylor with terse, intertwined electric riffs. Charlie Watts’ drumming, barely present on “Dear Doctor,” now supplies a tight, steady pulse through the verses, and Wyman reins in his bass line to include primarily rhythmic repeated-note interjections. But the song’s country flavor derives from a host of details, not its basic instrumental features. Among those details are things that are not there. For one, nearly all blue notes and seventh chords have been eliminated from the standard Rolling Stones musical language. Likewise, the chord patterns, while not necessarily “country” harmonic progressions per se, are dominated by root position major chords, which are the stuff of standard country music. In fact, only the “Three Chords and Truth” trio of harmonies are employed here: I, IV, and V (or D, G, and A). Significantly, the tell-tale VII chord is completely absent, stripping the harmony of a standard blues and rock marker. (The VII chord is ubiquitous in the Stones’ music. Some notable appearances in songs discussed so far include: “High and Dry” [“High and dry, well I’m up here with no warning”]; “No Expectations” [“I’ve got no expectations to pass through here again”]; and “Dear Doctor” [“It’s sleeping, it’s beating, can’t you please tear it out”]). Finally, the overdriven sound of the electric guitar is missing as well, as both Taylor and Richards maintain a clean signal in their respective channels. While not de rigueur for a rock guitar sound, overdrive and distortion were a base-line sound of rock by 1971. Their absence makes it that much easier to assign “Dead Flowers” to another style.

Perhaps the clean guitar sounds only point specifically to country due to Taylor’s many pedal-steel-like string bends, one of two country details that were added to the mix. More significant is Jagger’s vocal delivery. By now it may seem redundant to raise the issue of an affected Southern accent, after the observation of hard “R”s and other drawled words in “Dear Doctor” and “Far Away Eyes.” However, Jagger’s Southern persona in “Dead Flowers” is entirely different. Just as the drug-riddled back story accords with the Stones’ reality at that time, Jagger pulls punches in the delivery here to remove the comic edge that pervaded the songs of Deep Country. To be sure, final “R”s are hit hard, and some “L”s are drawn out (“You know I could never be a-Lone”; “Rose pink cadi-LL-ac”) so as to highlight the drawl of the ensuing vowel. Yet at no point does the song sound like a parody. In some ways it foreshadows Jagger’s much later solo recording, “Evening Gown” (1993), with its even more subtle hint of a Southern accent to fit the song’s country styling. In some ways, the more sincere he makes his Southern accent, the more unambiguously Jagger can turn a Rolling Stones song into a “country” song. Perhaps this is why songs like “Torn and Frayed” from Exile on Main Street (despite its use of pedal steel guitar) and Let It Bleed’s “Country Honk,” with its aggressive fiddle, make less of a claim. As anyone who has witnessed the rise of Bro country can attest, sometimes all that connects a song to a country claim is the singer’s Southern accent. We might not notice when the singer identifies as an American Southerner and dons a cowboy hat or boots, or a plaid flannel shirt, but it is to some degree the very essence of country. When the scarf-adorned poster boy for British rock puts on the accent, however, we are forced to take notice and contemplate the country identity of his song. Our attention is drawn even more compellingly when that singer and his band are so strongly identified with decidedly African-American musical styles, and, most critically, when that core association is achieved without an overreliance on a parallel affectation of black vocal idioms. The Southern accent is the strongest relic of the Old Country and Deep Country that imprints its sound on Stones Country, precisely because it reminds us how these songs draw a distinction from the Rolling Stones’ core sound and identity.