Compared to Mozart’s three Da Ponte operas and to the coronation opera with which it is exactly contemporaneous (La clemenza di Tito), The Magic Flute stands out for its eclectic blend of musical styles. Composed for the Theater auf der Wieden, The Magic Flute reflects the popular orientation of this suburban Viennese theater, incorporating musical characteristics from such diverse genres as magic opera, fairy-tale opera, Singspiel, and low comedy (especially the Hanswurst tradition), alongside stylistic elements from opera buffa and opera seria. While the work’s referential character results in part from Mozart’s kaleidoscopic use of musical topics (“styles or genres taken out of their proper context and used in another one,” according to Danuta Mirka1), many individual moments seem to draw their inspiration from earlier works. At least one scene – the duet of the Armored Men in Act 2 – includes a musical quotation that has been the subject of much speculation and debate, but this quotation seems to be the exception rather than the rule. Some scholars, however, have posited that the opera contains a vast network of musical borrowings and allusions. This chapter explores these claims in the broader context of The Magic Flute’s extraordinary array of musical styles and genres and offers a detailed critical examination of its possible references to specific works.

Topics

Any consideration of musical references in The Magic Flute should begin by addressing topics (topoi). In the eighteenth century, topics were a lingua franca through which recognizable situations and emotions could be wordlessly communicated without relying on a listener’s familiarity with specific compositions. In The Magic Flute, topics work in tandem with key associations and orchestration to perform a variety of functions: (1) to orient the listener, (2) to aid in characterization, and (3) to connect individual moments with the opera’s larger themes.

The opening scene, Tamino’s encounter with the serpent and rescue by the Three Ladies, illustrates how Mozart deploys topics to orient and engage the listener. Following the overture, the opera begins in medias res. String tremolos, rapid arpeggios, scalar descents, and the key of C minor – all hallmarks of the tempesta or Sturm und Drang style – conjure a “stormy” atmosphere that eighteenth-century audiences would have instantly recognized.2 Without yet knowing who Tamino is or why he is being pursued, the listener knows that he is in danger, well before he cries for help in measure 18. When the Three Ladies arrive to vanquish the serpent, there is an accompanying change of topic: wind-band orchestration and dotted rhythms indicate a march. This new topic, which precedes the Three Ladies’ cries of “Triumph!” is reinforced by the modulation to E-flat major, a key that was associated with the classically heroic ideal of Tugend (virtue) in many theatrical works.3 This association is made explicit in Mozart’s Act 1 finale, in which Tamino sings – in E-flat major – that he has come to the temple to seek “that which belongs to love and virtue” (“Der Lieb’ und Tugend Eigentum”). Mozart hence uses topics – together with keys and scoring – to ground the listener’s experience of the scene, while also forecasting tonalities that will gain significance as the opera unfolds.

Mozart also uses topics to introduce and animate his characters. The folk-like style of Papageno’s strophic “Vogelfänger” aria, for instance, marks him as an everyman, in contrast to Tamino, whose noble upbringing and loftier purpose are reflected in the more elevated style of his through-composed “portrait” aria. The Queen of the Night’s recitative and aria in Act 1, meanwhile, are conspicuously grandiose, recalling opera seria. A full-scale orchestral introduction marks her spectacular entrance; accompanied recitative allows the Queen to introduce herself; and an impressive two-tempo aria displays her emotional range, moving from a sentimental G minor (as she laments the loss of her daughter) to a coloratura-laden B-flat major (as she entrusts Tamino with Pamina’s rescue). In “Der Hölle Rache,” Mozart combines the “rage” aria type with the strict contrapuntal style, infusing the Queen’s ire with a particular sense of authority.4 Sarastro’s music, by contrast, tends toward the feierlich (a solemn, hymn-like style) and is suggestive of Masonic ritual, while the music of his servant Monostatos invokes the popular alla Turca style through its circular melodic figures, limited harmonic vocabulary, and repetitive phrases. Rooted in exoticizing Western European depictions of Turks and Turkishness, this style could also signify cultural and racial Otherness more generally.5 Pamina’s G-minor aria “Ach ich fühl’s,” meanwhile, exemplifies an aria type associated with sentimental heroines in distress; however, she also shares a folk-like duet with Papageno, imbuing her character with a greater emotional breadth than that of her counterpart, Tamino.

Two topics, the “strict” style (variously called the strenge, gebundene, or fugenartige Schreibart by the music theorist Heinrich Christoph Koch) and the feierlich, relate individual moments to the opera’s overarching themes. Standing in stark contrast to the galant idiom that more typically characterizes Mozart’s writing, these two styles help to depict the opera’s elements of ritual and mysticism. On the one hand, they create distinctive musical atmospheres that help dramatize the libretto’s fantastical invocation of distant or mysterious cultures (ancient Egypt, Freemasonry). On the other hand, they recall contemporary sacred genres, reinforcing the religious tone of the temple scenes. In the case of the strict style, which appears most prominently in the overture and the duet of the Armored Men (on which more later), the “law” of counterpoint analogizes the “law” of the temple: by alluding to the strict style, Mozart musically illustrates the notion that Tamino must follow the law in order to reach Enlightenment. However, as Keith Chapin has noted, “the rules of the Temple are malleable”: Tamino, despite being a prince, is allowed to become an initiate (Act 2, scene 1); similarly, as Pamina proves her worth, the interdiction on the initiation of women is rescinded (Act 2, scene 28). Chapin views the strict style as a more flexible signifier, arguing that it stands for the progressive rationalism of the Enlightenment era. The blending of galant themes with contrapuntal procedures in the overture, he argues, “symbolizes the process of modernization that the subsequent action represents.”6

Musical Sources and Affinities

Another category of musical references involves allusions to specific works, whether by Mozart or by other composers. Writing in 1913, Théodore de Wyzewa suggested that “the score of Die Zauberflöte practically presents us with a ‘pot-pourri,’” calling for scholars to assemble “an inventory of those ‘sources’ from which [Mozart] drew the varied materials for his last opera.”7 Although Wyzewa himself never attempted such an inventory, A. Hyatt King took up the call in a 1950 article, republished in 1955 as part of his book Mozart in Retrospect: Studies in Criticism and Bibliography. Uncovering the “sources” for The Magic Flute has remained an area of interest into the twenty-first century.8

King’s study is a tour de force, offering approximately one hundred precursors for the opera’s themes (see Table 8.1). Many of these derive from Otto Jahn’s Mozart biography (as well as its revisions by Hermann Abert and Hermann Deiters); others stem from the work of Wyzewa and Georges de Saint-Foix; still others from Jean Chantavoine’s Mozart dans Mozart, King’s own observations, and a handful of other sources. A few cases, such as the claim that the overture’s fugal subject is based on the opening theme of Clementi’s Sonata in B-flat, Op. 24, No. 2, date back to the early nineteenth century. According to his pupil Ludwig Berger, Clementi played this sonata during his piano duel with Mozart in the presence of the emperor in December 1781.9

Table 8.1 Melodic sources and affinities of The Magic Flute, according to A. Hyatt King (1955)

| Idea in The Magic Flute | Melodic source/affinity | Previous mentions noted by King |

|---|---|---|

| Overture | ||

| Threefold chord | Mozart, König Thamos, no. 2, opening | |

| Holzbauer, Günther von Schwarzburg, opening | ||

| Fugal subject | Clementi, Sonata in B-flat Major, Op. 24, no. 2, opening | Caecilia 1829 |

| Piccini, Il Barone di Torreforte, Act I, scene 3, quartet | Della Corte | |

| Mozart, Idomeneo, no. 5, violin part | ||

| Mozart, Symphony No. 38 (“Prague”), K. 504, I: 37−42 et passim | ||

| Mozart, Sonata in B-flat Major, K. 498a, I: 81 | ||

| Mozart, Sonata in B-flat Major, K. 570, I: 45, 46 | ||

| Rolle, Lazarus oder die Feyer der Auferstehung, overture | Caecilia 1843 | |

| Haydn, Il mondo della luna, Act I finale | ||

| Cimarosa, Il matrimonio segreto (1792), Act I, “Io ti lascio” | ||

| No. 1 | ||

| Last part of trio | Mozart, Le nozze di Figaro, no. 13 | |

| No. 3 | ||

| “Dies Bildnis” | Mozart, Violin Sonata in F Major, K. 377, I, opening | |

| Mozart, String Quintet in G Minor, K. 516, III: 18−21 | ||

| Mozart, Sonata in C Major, K. 279, I: 22 | ||

| Gluck, “Die frühen Gräber” | Einstein | |

| Haydn, Sonata in B-flat Major, Hob. XVI:41, I, opening | ||

| “Ich fühl’ es” | Mozart, Idomeneo, no. 11 | |

| Mozart, String Quartet in E-flat Major, K. 171, I: 1, 2 | ||

| Mozart, Symphony No. 40 in G Minor, K. 550, II: 77−79 | ||

| Gassmann, I Viaggiatori ridicoli | Haas | |

| works by C. P. E. Bach, Grétry, Paisiello | Abert | |

| Haydn, Sonata in G Major, Hob. XVI:27, II: 18−20 | ||

| Postlude | Mozart, Zaide, no. 4, ending | |

| Mozart, String Quartet in B-flat Major (“Hunt”), K. 458, III, ending | ||

| No. 4 | ||

| Introduction | G. Benda, Ariadne | Caecilia 1843 |

| “Ihr ängstliches Beben” | Mozart, Idomeneo, no. 11, “L’angoscie, gl’affanni …” | |

| “Auf ewig dein” | Mozart, Die Entführung aus dem Serail, no. 6, ending | |

| Coloratura section | P. Wranitzky, Oberon, no. 6 (“Dies ist des edlen Huons Sprache”) | “a common-place of Mozart criticism” |

(cont. A)

| Idea in The Magic Flute | Melodic source/affinity | Previous mentions noted by King |

|---|---|---|

| No. 5 | ||

| Orchestral motive | Mozart, Idomeneo, no. 23 | |

| Mozart, Flute Concerto in D Major, K. 314, I | ||

| Mozart, La clemenza di Tito, no. 22 | ||

| Gluck, Alceste, Act 1, no. 4 | ||

| “Hm! Hm! Hm!” | Philidor, Bucheron, septet | |

| No. 6 | ||

| “Du feines Täubchen” |

| |

| No. 7 | ||

| Duet | Mozart, Symphony No. 36 in C Major (“Linz”), K. 425, III, opening | |

| No. 8 | ||

| “Zum Ziele führt dich diese Bahn” | “Die Katze lässt das Mausen nicht” (folksong found in Augsburger Tafelkonfekt 1737; Bach, “Coffee Cantata,” final chorus; Mozart, Divertimento in E-flat Major, K. 252, IV, main theme; Mozart, Concerto for Two Keyboards, K. 365, III, main theme: passim; Beethoven, Piano Concerto No. 1 [1795], III) | Wyzewa |

| Tamino’s recitative | Gluck, Iphigénie en Aulide, Agamemmnon’s soliloquy | |

| “Sobald dich führt der Freundschaft Hand” | Mozart, Sonata in A Minor, K. 310, I: 129−32 | |

| Tamino’s flute solo and “Wie stark ist nicht dein Zauberton” | Mozart, Andante for Flute and Orchestra in C Major, K. 315, flute entry | |

| “Schnelle Füße, rascher Mut” | Mozart, La finta semplice, no. 17 | |

| “He, ihr Sklaven, kommt herbei!” | Mozart, Die Entführung, no. 7, “Marsch fort, fort, fort …” | |

| Mozart, Don Giovanni, no. 1, “Notte e giorno faticar … ” | ||

| “Es lebe Sarastro, Sarastro lebe!” | Mozart, König Thamos, no. 1, “Erhöre die Wünsche … ” | |

| Mozart, Sonata for Two Keyboards in F Major, K. 497, I: 125 | ||

| “O wär’ ich eine Maus” (Papageno) | Mozart, Concerto for Two Keyboards in E-flat Major, K. 365, I: 269, 270 | |

| “Mir klingt der Muttername süße” | Mozart, Serenade for Wind Octet in E-flat Major, K. 375, III: 26−32 | |

| Mozart, “Als Luise,” K. 520 | ||

| Mozart, Violin Sonata in E-flat Major, K. 481, II: 19−21 | ||

| Mozart, Idomeneo, no. 21, “M’avrai compagna al duolo” |

(cont. B)

| Idea in The Magic Flute | Melodic source/affinity | Previous mentions noted by King |

|---|---|---|

| No. 9 | ||

| March of the Priests | Gluck, Iphigénie en Tauride, marches | |

| Wranitzky, Oberon, march | ||

| Mozart, Così fan tutte, no. 29, “pietoso il ciglio” | ||

| Mozart, Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat Major, K. 297b, III | ||

| Mozart, Idomeneo, no. 25 | ||

| Mozart, sketch from 1784 | ||

| Mozart, Divertimenti in F Major, K. 247, IV and K. 253, I | ||

| Corelli, Op. 5, no. 6, opening | “surely … musical coincidence” | |

| No. 10 | ||

| “Stärkt mit Geduld sie in Gefahr” | Haydn, Symphony No. 85 in B-flat Major (“La Reine”), I: 93−95 | |

| No. 12 | ||

| “Wie? Wie? Wie?” | Mozart, String Quartet in G Major, K. 387, IV: 108−10 | |

| No. 13 | ||

| Opening | Mozart, Keyboard Concerto in E-flat Major, K. 271, III: 35−39 | |

| Mysliveček, Overture to Demofoonte, opening | Quoted in letter to Mozart from his father | |

| “Alles fühlt” | Grétry, Amitié à l’épreuve, “Grande, grande réjouissance” | Abert |

| No. 15 | ||

| Opening | Mozart, Idomeneo, no. 31 | |

| No. 16 | ||

| Violin figure | Mozart, Violin Concerto in A Major, K. 219, III, ending | |

| Mozart, String Trio in E-flat Major, K. 563, II, ending | ||

| Mozart, Sonata in E-flat Major, K. 281, III: 18−21 | ||

| No. 17 | ||

| “Nimmer kommt ihr, Wonnestunden” | Mozart, Le nozze di Figaro, no. 28, “finché non splende … ” | |

| “Meinem Herzen mehr züruck” repetition | Gluck, Orfeo, Orpheus’s first aria, ending | |

| No. 19 | ||

| “Der Götter Wille mag geschehen” | Mozart, Clarinet Quintet in A Major, K. 581, I: 42−44 | |

| Mozart, Concerto for Three Keyboards in F Major, K. 242, I: 74, 75 | ||

| Mozart, Keyboard Concerto in B-flat Major, K. 450, I: 33−35 | ||

| Mozart, Keyboard Concerto in F Major, K. 459, III: 151−3 | ||

| Mozart, Sonata in G Major, K. 283, II: 10 |

(cont. C)

| Idea in The Magic Flute | Melodic source/affinity | Previous mentions noted by King |

|---|---|---|

| Mozart, Sonata in C Major, K. 309, II: 67, 68 | ||

| Mozart, Keyboard Rondo in F Major, K. 494: 70, 71 | ||

| Mozart, Serenade in D Major (“Haffner”), K. 250, VIII: 1, 2 | ||

| “Ach, gold’ne Ruhe” | Mozart, Idomeneo, no. 21, “Peggio è di morte” | István Barna |

| No. 20 | ||

| Melody | Scandello, chorale “Nun lob mein Seel den Herrn” (lines 7 and 8) | C. F. Becker, Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 1839; Jahn |

| Haydn, Il mondo della luna, “Wollt’ die Dreistigkeit entschulden” | Chantavoine | |

| No. 21 | ||

| “Führt mich hin, ich möcht’ ihn seh’n” | Mozart, Le nozze di Figaro, no. 29, “Che smania, che furor” | Chantavoine |

| Mozart, Die Maurerfreude, “wie dem Starren Forscherauge” | Chantavoine | |

| Fugal subject (duet of the Armored Men) | H. Biber, Mass of 1701, Kyrie | Abert |

| Chorale melody | Luther, “Ach Gott, von Himmel sieh’ darein” | “generally recognized” |

| Kirnberger, setting of “Es wollt uns Gott gnädig sein” | ||

| Tamino’s flute-playing; chords on trumpets and drums | Mozart, Divertimento in C Major, K. 188 | |

| Mozart, Les petits riens, no. 3 | ||

| Flute music | Mozart, Così fan tutte (“nearly a dozen appearances”) | |

| Mozart, String Trio in E-flat Major, K. 563, II: 54 | ||

| Mozart, String Quartet in B-flat Major, K. 589, III: 7, 36, &c. | ||

| Mozart, String Quartet in A Major, K. 464, I: 234 | ||

| Mozart, Minuets, K. 585, no. 5, trio | ||

| Mozart, Armonica Quintet in C Minor, K. 617, rondo: 16, &c. | ||

| Papageno and Papagena’s duet | Mozart, Keyboard Concerto in F Major, K. 459, finale | |

| Mozart, Keyboard Concerto in G Major, K. 453, finale | ||

| “Heil sie euch Geweihten” | Mozart, König Thamos, no. 7, “Höchste Gottheit” | |

| Mozart, Le nozze di Figaro, no. 29, “Contessa, perdono” | ||

| Mozart, Idomeneo, no. 31, “Scenda Imeneo” | ||

| “die Schönheit und Weisheit” | Mozart, Divertimento in F Major, K. 253, I: variation 3 | |

| Mozart, Idomeneo, no. 16, “Del ciel la clemenza” |

King credits the pastiche-like quality of The Magic Flute in part to Mozart’s incredible memory and in part to the haste and difficult conditions in which he composed the opera. He concludes that “Die Zauberflöte presents a paradox virtually without parallel in music history – an opera universally admitted to be a work of genius, and seemingly one of striking originality, which is in part a synthesis of material drawn from a variety of sources.”10 However, the emergence of a work of “striking originality” from a “synthesis of material” would not have been thought paradoxical in the eighteenth century, nor was it without parallel (one thinks of the “recycling” practices of Handel and Bach). Moreover, many of the melodies that King proposes seem to be related to The Magic Flute by virtue of what Jan LaRue has termed “family resemblance” rather than actual reminiscence.11 Despite its inclusion of many intriguing and plausible connections, King’s inventory of sources raises perhaps more questions than it answers.

Ironically, King did not locate any sources for The Magic Flute in the handful of works that most closely resemble it: the fairy-tale Singspiele produced by Schikaneder at the Theater auf der Wieden. These works – Oberon, König der Elfen (November 7, 1789), Die schöne Isländerin, oder Der Muffti von Samarkanda (April 22, 1790), Der Stein der Weisen, oder Die Zauberinsel (September 9, 1790), and Der wohltätige Derwisch, oder Die Schellenkappe (early 1791) – contain many parallels with The Magic Flute.12 Perhaps the most significant of these are found in Der Stein der Weisen (The Philosopher’s Stone), a collaborative opera to which Mozart contributed music. As David J. Buch has observed, in addition to offering a “romantic mixture of solemn, comic, magic, and love scenes,” both works feature “a similar two-act structure with an introduzione, large-scale episodic finales, and similar arias and ensembles,” “musical segments for the working of the mechanical stage and for magic episodes,” and “traditional supernatural devices” such as “enchanted march music, magical wind ensembles, and the use of descending octave leaps for magic invocations.”13 Astromonte’s entrance music, attributed to Johann Baptist Henneberg, may have provided a model for the Queen of the Night’s: in both cases, a syncopated prelude designed to accompany stage machinery gives way to an accompanied recitative and two-part aria ending with a coloratura section in B-flat major.14 Astromonte’s proclamation “Zittert nicht” (Tremble not) even anticipates the Queen’s opening line, “O zittre nicht.” Of course, there are also important differences between these two numbers: while the Queen’s aria is in a closed bipartite form, for instance, Astromonte’s initiates a through-composed complex involving the chorus; the Queen’s aria also includes a poignant slow section in the minor mode that is unlike anything sung by Astromonte. Thus, if Mozart modeled the Queen of the Night’s entrance on Astromonte’s, he felt free to adapt Henneberg’s concept to suit his dramatic needs.

Henneberg may also have inspired another musical idea in The Magic Flute. As Alan Tyson noted, his children’s song “Das Veilchen und der Dornstrauch” (The Violet and the Thornbush), published in a collection to which Mozart also contributed three numbers (Liedersammlung für Kinder und Kinderfreunde; Vienna, 1791), contains a brief passage reminiscent of the closing idea in the first quintet for the Three Ladies, Tamino, and Papageno (No. 5, mm. 230–33 or 234–37).15 Henneberg was the Kapellmeister at the Theater auf der Wieden and participated in the earliest rehearsals and performances of The Magic Flute. Hence, it is plausible, as Tyson suggests, that Mozart referenced the song as a tip of the hat to his younger colleague. That said, the passage in question is so short (and, arguably, musically commonplace) that a definitive conclusion is difficult to reach.

Papageno’s “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen” and the Duet of the Armored Men

Of course, in situations involving music by other composers, Mozart’s documented knowledge of the work in question may enhance the plausibility of the musical relationship. Here, the complex case of Papageno’s aria “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen” comes to the fore. In a note published in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik in 1840, Carl Ferdinand Becker drew attention to the melodic similarity between the opening of Papageno’s aria and the seventh and eighth lines of the popular Lutheran chorale “Nun lob, mein Seel, den Herren” (see Examples 8.1a and 8.1b). Noting that Mozart quotes a different Lutheran chorale in the duet of the Armored Men, Becker found it unsurprising that “Nun lob” should appear in The Magic Flute, even if the reference was an “innocent and, for the composer himself, unconscious mystification.”16 Becker never attempted to answer the question of how precisely Mozart knew the chorale, nor did his suggestion of an “unconscious” reminiscence require him to demonstrate that the reference was of any particular significance.

Example 8.1 Some melodic antecedents of Papageno’s aria “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen” (No. 20).

There, the matter seemingly rested until Max Friedländer’s 1902 study Das deutsche Lied im 18. Jahrhundert, in which he derived the tune of Papageno’s aria from an altogether different source, the folksong “Es war ein wilder Wassermann” (see Example 8.1c). Friedländer mentioned the folksong as a source for Friederich Kunzen’s 1786 lied “Au bord d’une fontaine” (see Example 8.1d), noting that Mozart too used the melody for Papageno’s aria. However, he provided no evidence that Mozart (or Kunzen) knew it. Nevertheless, Hermann Abert (1919–21) reiterated and amplified Friedländer’s notion, mentioning operatic melodies by Galuppi (1771), Grétry (1778), and Paisiello (1784) that have a similar design and folklike character (and that Mozart was perhaps more likely to have known). Chantavoine (1948) suggested yet another piece with a related melody, Bonafede’s Act 1 aria from Haydn’s Il mondo della luna (1777). But in a 1963 article, Frederick W. Sternfeld, without explicitly rejecting Friedländer’s claim, reopened the possibility that Mozart based Papageno’s aria not on the folksong but on “Nun lob,” providing ample evidence that Mozart encountered this chorale in the 1780s through settings by J. S. Bach.17

In terms of melodic provenance, Sternfeld’s case is the stronger of the two. But which is the more plausible model? On the one hand, Mozart certainly knew “Nun lob,” but from a generic, stylistic, and textual point of view, the chorale has little to do with the drama at hand. Furthermore, although the melodic resemblance is striking, the tune in question comes rather incongruously from the seventh and eighth phrases of the chorale (themselves appearing, with antiphonal passages interspersed, in the middle section of Bach’s motet Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied, BWV225 – a work Mozart both heard and studied in 1789). On the other hand, while we cannot be certain that Mozart ever encountered the folksong suggested by Friedländer, here the genre, tone, and text resonate with Papageno’s character. In addition, the first two measures of the folksong align neatly with the beginning of Papageno’s melody (although the next two measures are less closely related to it than the eighth phrase of “Nun lob”). Which domains should one privilege in asserting a musical borrowing?

In the operatic context, one might pose another question: Assuming Mozart was aware of what he was doing, what dramatic purpose does the musical borrowing serve? A subtle allusion to a Lutheran chorale seems to be above Papageno’s pay grade. Indeed, it seems more likely that Papageno’s aria was designed to bring out the artless naiveté – “der schein der Bekannt” – that J. A. P. Schulz and his circle (including Kunzen) sought in composing lieder in a folklike style.18 Songs like Kunzen’s “Au bord d’une fontaine” and “Der Landmann” (Example 8.1e) – both related to “Es war ein wilder Wassermann,” but published in Mozart’s day – in this respect represent a contemporary “type” of which Papageno’s aria is an example. Though it is impossible to prove or disprove Mozart’s indebtedness to “Nun lob,” I would argue that his engagement with contemporary folksongs – and their artful adaptations on the operatic stage – is ultimately of greater significance for understanding “Ein Mädchen.”

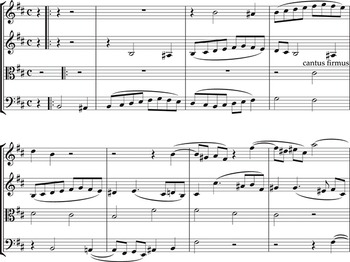

The strong desire among scholars to link Mozart and J. S. Bach has also led to curious conclusions regarding the provenance of the chorale in the duet of the Armored Men, the only indisputable musical quotation in the opera. The source, Martin Luther’s “Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein” (1524) was identified as early as 1798 by Friedrich Rochlitz.19 (Mozart slightly alters Luther’s melody, omitting the repetition of the Aufgesang and adding a newly composed final phrase to the Abgesang to allow for a tonic cadence.) Abert maintained that Mozart discovered this melody in the first volume of Johann Philipp Kirnberger’s treatise Die Kunst des reinen Satzes in der Musik (1771–79), where it is used as a cantus firmus in no fewer than twelve separate examples.20 One of these, a trio in B minor, not only relates to the duet of the Armored Men, but also closely resembles Mozart’s cantus firmus sketch of 1782 based on the same chorale melody and written in the same key of B minor (see Example 8.2).21

Example 8.2a Kirnberger, trio on “Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein,” mm. 1–9, Die Kunst des reinen Satzes in der Musik (Berlin and Königsberg: G. J. Decker and G. L. Hartung, 1774; first published 1771), vol. 1, 238–39 (clefs modernized for ease of comparison).

Example 8.2b Mozart, cantus firmus sketch on “Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein,” mm. 1–8, KV Anh. 78/K. 620b (1782), Neue Mozart Ausgabe II/5/19 (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1970; digital version, Internationale Stiftung Mozarteum, 2006), 377.

Example 8.2 Precursors of the duet of the two Armored Men by Kirnberger (1771) and Mozart (1782).

In a 1956 article, however, Reinhold Hammerstein argued that Mozart was unlikely to have found the melody in Kirnberger’s book. His reasoning hinged on two claims: first, Mozart does not appear to have known the treatise (nor was it in his Nachlass), and second, Kirnberger reproduced the chorale without its text, an element that for Hammerstein was a crucial impetus for the musical quotation.22 Hammerstein instead suggested that Mozart may have either found the chorale in a Protestant hymnbook or heard it in the Masonic lodges, arguing that its treatment in the duet of the Armored Men owed more to Bach’s motet Jesu, meine Freude, BWV227. To be sure, Mozart’s encounter with Bach’s music was transformative and may well have influenced his approach in this scene; however, the scene’s relationship with Kirnberger’s examples – especially in light of Mozart’s sketches – is too strong to ignore. Recently, Markus Rathey has provided compelling evidence that Mozart knew and engaged with Kirnberger’s treatise, detailing the musical similarities among Kirnberger’s examples, the sketches, and the scene.23

Whether or not Luther’s text, a paraphrase of Psalm 12, motivated Mozart to select “Ach Gott” for the duet of the Armored Men remains a matter for speculation. As Hammerstein and others have noted, Luther’s fifth stanza – with its images of fire, trial, and purification – relates strongly to Schikaneder’s text for the scene.24 Of course, Mozart may well have come into contact with the chorale in multiple forms; one need not dismiss the significance of the chorale text simply because Kirnberger did not include it in his examples. Ultimately, however, the intertextual reference to Psalm 12 is less significant than the presence and setting of the tune itself. By alluding to the baroque genre of the chorale prelude in a Singspiel, Mozart blends the sacred and the secular, the “ancient” and the “modern,” as well as the unfamiliar and the familiar. In so doing, he lends an oracle-like authority to the proclamation read by the two Armored Men, impressing upon both Tamino and the listener that the path to Enlightenment will be full of great hardships (“voll Beschwerden”) and still greater mysteries.

A Musical Panorama

Beethoven is said to have admired The Magic Flute because it employs “almost every genre, from the lied to the chorale and the fugue,” and because of the way Mozart used different keys “according to their specific psychical qualities.”25 As in the case of tonalities with their characteristic – if not always agreed-upon – emotional associations, the opera’s musical references add psychological depth to its characters and situations while illuminating the libretto’s most important themes. No theatergoer, then or now, could claim to have a comprehensive picture of these references. Indeed, some of the melodic borrowings that modern scholars have heard in The Magic Flute would probably have surprised Mozart, who was, after all, using a common vocabulary and engaging intuitively, as well as intentionally, with his musical environment. Nonetheless, The Magic Flute presents a musical panorama unlike that of perhaps any other contemporary opera. Much more than the result of a patchwork approach to composition, the work’s stylistic allusions and juxtapositions are an essential element of its dramatic conception. Mozart’s wide-ranging referentiality both elaborates and elevates Schikaneder’s libretto, bringing its singular combination of comedic, heroic, magical, romantic, allegorical, and fairy-tale elements to life.