Vienna, October 1 (from private letters):

Yesterday a Singspiel, Die egyptischen Geheimniße, for which Hr. Mozart composed the music and himself directed the orchestra, was performed in the Wiednertheater to unanimous acclaim. Hr. Schikaneder went all out to present this opera in accurate costume, with appropriate splendor in dress and scenery. On the same evening in the Leopoldstadt a new play was given, Die Indianer. An orangutan that appeared in the piece received the greatest applause.1

Thus reported the Münchner Zeitung on October 7, 1791. This excerpt – placing the success of Mozart’s Singspiel alongside that of a spoken play featuring an orangutan – is the earliest known account following the premiere of The Magic Flute. To be sure, the opera, which is referred to by the alternative title Die egyptischen Geheimniße (The Egyptian Mysteries), was first given on September 30, 1791, in a performance that was well received according to this correspondent.2

Yet, despite the “unanimous acclaim” – not to mention the popularity and canonic status that The Magic Flute would achieve in the decades that followed – little can be said with certainty about its first performance. Not much is known about the opera’s commission, preparation, and production as the correspondent of the Münchner Zeitung would have experienced it. Although the sources available simply do not provide a full picture of the premiere, this chapter draws on existing documentary evidence to consider how audiences may have experienced The Magic Flute in 1791. More than that, however, this chapter attempts to contextualize the conception and earliest performance(s) by approaching the work not as Mozart’s final opera informed by over two hundred years of reception history, but rather as the product of a specific historical moment.

Toward the German Theater: Mozart in 1791

Understanding Mozart’s circumstances in the period leading up to the premiere of The Magic Flute is key to understanding the work itself. To be sure, the Mozart of 1791 was not the Mozart listeners know today. K. M. Knittel’s distinction between Beethoven and “Beethoven’’ is equally applicable here: Mozart was not yet “Mozart” when The Magic Flute first appeared, meaning that his romantic hagiography only emerged posthumously.3 Understanding his circumstances in the years before the premiere helps explain why Mozart might have taken on the project – one quite unlike any other he had previously undertaken – in the first place.

In the decade between his relocation to Vienna in 1781 and the appearance of The Magic Flute, Mozart had composed four operas specifically for the city’s theatergoers: Die Entführung aus dem Serail (1782), Der Schauspieldirektor and Le nozze di Figaro (1786), and Così fan tutte (1790).4 Granted, Don Giovanni also appeared on the Viennese stage (1788), but Mozart had composed this opera for audiences in Prague (1787). Despite what the disproportionate attention on Mozart in secondary literature might suggest, data from Vienna indicates that he was less successful than some of his contemporaries, when measured by the number of performances his operas received.5 If it is true that “the more popular an opera was, the more it was repeated,” then Mozart’s works were not as well received as those of his peers, at least by the standards of the theatergoers for whom they were intended.6 For example, Die Entführung, Mozart’s most successful work for the German stage prior to The Magic Flute, was given twelve times in the Kärntnertortheater and Burgtheater (the Viennese court theaters) the year it was premiered, whereas another popular contemporary German opera, Der Apotheker und der Doktor (1786) by Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf (1739–99), was given twenty times in these theaters in the year of its premiere. In total, during Mozart’s lifetime Die Entführung would go on to be staged in the court theaters on only about ten more occasions than Der Apotheker, despite having had a four-year head start.7 So far as Italian operas for the Viennese court theaters are concerned, between the premiere of Figaro in 1786 and Mozart’s death in 1791, works by Vicente Martín y Soler (1754–1806), Antonio Salieri (1750–1825), and others were performed significantly more often than Mozart’s “Da Ponte” operas.8 Performance data from this period are clear on this point and provide an important sense of the operatic world in the years before The Magic Flute.

These figures are supported by contemporary opinion. When Johann Pezzl (1756–1823) listed Vienna’s most beloved operas in 1787, he named works by Dittersdorf, Martín, Paisiello, Salieri, and Giuseppe Sarti.9 Mozart and his music are conspicuously absent. What is more, Mozart was the second choice of composer for Così and La clemenza di Tito (1791), both having been offered first to Salieri.10 In short, Mozart’s contemporary status and fortunes as a composer were anything but certain in 1791.

The period immediately prior to The Magic Flute’s premiere had been particularly difficult for the composer for other reasons as well. From 1788 until at least mid-1791, Mozart had borrowed significant sums of money from friends to pay pressing debts and make ends meet.11 Hoping to turn around his precarious fortunes, he invested significant amounts in two performance tours: one to Dresden, Leipzig, and Berlin between April and June 1789 and another to Frankfurt am Main, Mainz, and Mannheim from September to October 1790.12 His financial situation was no secret. In a letter dated April 7, 1791, the Mannheim actor Heinrich Beck (1760–1803) – whose wife Josepha Beck (unknown–1827) played the role of the Countess in a performance of Die Hochzeit des Figaro during Mozart’s 1790 visit – wrote to the dramatist Friedrich Wilhelm Gotter (1746–97) in Gotha.13 Even though Beck was well aware that “Mozart … is in very limited circumstances,” he recommended Dittersdorf – known for his works for the German stage – as a potential composer for Gotter’s latest text.14

Uncertain professional success, financial instability, and missed opportunities may have led Mozart to begin exploring the possibilities that the German theater had to offer. After all, the vast majority of audiences throughout the Holy Roman Empire and wider Kulturkreis encountered operas set in Italian as German-language adaptations for their local stages. As was the case in Mannheim, far more Central European theatergoers experienced Le nozze di Figaro in German adaptation as Die Hochzeit des Figaro and Don Giovanni as Don Juan, for instance. And, specifically in Vienna, the court theater was not attracting theatergoers as it once had.15 It is little surprise, then, that Schikaneder and Mozart began to collaborate professionally in 1790 and 1791. When Mozart agreed to compose The Magic Flute, he acknowledged the German stage as a source of both potential recognition and income and decided to try his luck there.

Toward The Magic Flute: The Schikaneder Company and Viennese Theater in the Reign of Leopold II

Of the hundreds of German-language theater companies active in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, Schikaneder’s was one of a few that operated continuously throughout the period. The troupe was experienced, for it had visited roughly ten cities and towns within the southern half of the empire by the time it reached Vienna.16 Like many other companies, Schikaneder’s actors staged both spoken and musical theater. Among the troupe’s musico-theatric repertoire in this period were such works as Dittersdorf’s Der Apotheker und der Doktor, Salieri’s Die Höhle des Trofonius (La grotta di Trofonio, 1785), Martín’s Lilla (Una cosa rara, 1786), and Johann Ernst Hartmann’s Balders Tod (1788), to name but a few.17

Schikaneder and Mozart had first met when his company visited Salzburg in 1780, and within a year of his troupe’s relocation to Vienna, in 1789, they were working together. The first evidence of collaboration was Der Stein der Weisen (1790). This Singspiel was written by Schikaneder and set to music by the Wiednertheater Kapellmeister Johann Baptist Henneberg (1768–1822), company actor-singers Franz Xaver Gerl (1764–1827) and Benedikt Schack (1758–1826), Schikaneder, and Mozart, who probably set the duet “Nun liebes Weibchen” (K625) and assisted with the second-act finale.18 Building on the success of earlier works, including Oberon, König der Elfen (1789) by Paul Wranitzky (1756–1808), Der Stein der Weisen was the latest of Schikaneder’s so-called magic operas (Zauberopern) and machine comedies – terms used to denote pieces that drew heavily on stage machinery and effects to enhance the spectacle. The vogue for such Zauberopern resulted in steady competition between the Wiednertheater and the nearby Theater in der Leopoldstadt. When the latter theater premiered the incredibly successful Kaspar der Fagottist by Joachim Perinet (1763–1816) and Wenzel Müller (1767–1835) in June 1791, Schikaneder’s Wiednertheater was already preparing its response: The Magic Flute.19

One of the reasons very few documents survive concerning the commission and early composition of The Magic Flute is almost certainly because Mozart and his collaborators were together in Vienna, so they had no need to correspond. Writing in the early 1990s, Peter Branscombe suggested that “it is unlikely that the details of Mozart’s contract with Schikaneder (if there was one) will ever be known, or when he began to write the score.”20 His prediction remains true thus far. The earliest known reference to The Magic Flute is found in one of Mozart’s letters to Constanze (1762–1842), his wife, thought to have been written on June 11, 1791. Mozart expresses here his anxiety about finances and mentions having “composed an aria from the opera.”21 Given what is known about Mozart’s compositional practices, he was most likely hard at work on The Magic Flute by this point, as he typically set ensembles first and composed arias only later.22 Subsequent references to the Singspiel appear in the postscript of a letter written sometime around late June or early July and in yet another dated July 2. These missives confirm that Mozart’s work on the opera was advanced, as he asked Constanze to ensure that Franz Xaver Süßmayr (1766–1803) was making progress with the short score, so that he could begin orchestrating numbers from the first act.23 Meanwhile, evidence found in correspondence dated between July 3 and 12 indicates that Mozart was also well into the second act by this point.24 All but a few numbers of The Magic Flute were complete when Mozart departed for Prague, at which time he shifted most of his attention to La clemenza di Tito, an opera designed to celebrate the coronation of Emperor Leopold II as king of Bohemia.

While Mozart was in Prague, it is assumed that Henneberg took over rehearsals for The Magic Flute.25 Exactly how Henneberg and the troupe’s other actor-musicians – Gerl, Schack, and Schikaneder – may have shaped its music remains uncertain. But given that Mozart had collaborated with them before, set three of The Magic Flute’s leading roles for them, and was later feverishly occupied with Tito, it is possible that they made contributions that shaped the work throughout its creation. To be sure, collaboration may help to explain the fact that Henneberg’s song “Das Veilchen und der Dornstrauch,” printed in the Liedersammlung für Kinder und Kinderfreunde am Clavier (1791), included music that would later appear in the final section of the Act 1 quintet “Hm! Hm! Hm!”26

In mid-September, Mozart departed from Prague and returned to Vienna, where he resumed work on the The Magic Flute, just in time for the premiere. He entered the March of the Priests (Act 2, scene 1, no. 9) and the overture in his thematic catalogue on September 28. Such late additions – his last documentable work on the opera – were common for the period. As Mozart’s frenzied labor composing The Magic Flute and La clemenza di Tito in the summer and autumn of 1791 suggests, composers often continued working on pieces right up to the opening night.

The Premiere of The Magic Flute

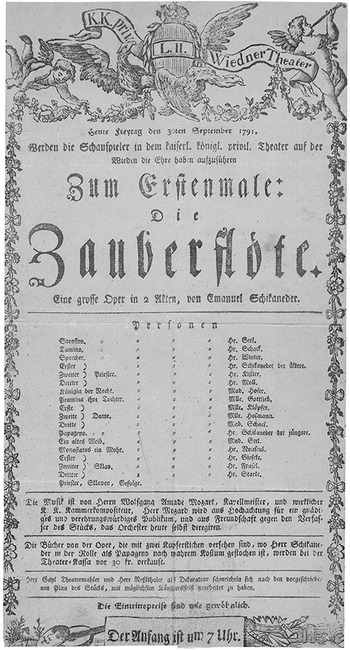

The Magic Flute was first brought to the stage in the Theater auf der Wieden at 7:00 p.m. on Friday, September 30, 1791. The principal roles were created for and by veteran actors of Schikaneder’s company. Many of these singers had been active on other German-language stages across Central Europe before joining the troupe and each filled one of the era’s stock character types. As was standard for the period, the playbill advertising this performance lists the cast on the opening night (see Figure 4.1). Heading the bill was Franz Xaver Gerl, the first Sarastro, particularly known for comic roles and a former student of Leopold Mozart (1719–87) in Salzburg before joining the companies of Ludwig Schmidt (unknown–1799) in Franconia and Gustav Friedrich Wilhelm Großmann (1746–96) in the Rhineland. A former Kapellmeister to the prince of Schönaich-Carolath, Benedikt Schack became a member of Schikaneder’s troupe in 1786. Schack was the leading tenor by the time Schikaneder took over the Theater auf der Wieden, and it was for him that Schikaneder and Mozart created the part of Tamino. Josepha Hofer (1758–1819), Mozart’s sister-in-law and first Queen of the Night, performed in Graz before joining the troupe at the Theater auf der Wieden in 1789, for which she sang many leading parts, including Titania in Wranitzky’s Oberon, König der Elfen. The first Pamina, Anna Gottlieb (1774–1856), was a native of Vienna, where she grew up in a family of actors. Gottlieb was young, but experienced. Active on the stage from the age of five, she had also created the role of Barbarina in Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro when she was only twelve years old. Schikaneder, in writing the text, created the part of Papageno for himself. Barbara Gerl (1770–1806) specialized in leading female parts and created the role of Papagena. These actor-singers were supported by other actors as well as the company’s orchestra, comprising about thirty-five musicians.

Figure 4.1 Playbill for the premiere of The Magic Flute.

It is clear that the opera featured novel costumes and sets. This was a common practice employed by theater companies to draw audiences: investing in bespoke decorations and clothing to supplement more common and universal sets – like gardens, palaces, chambers, and temples – that could be reused from earlier productions.27 Sources differ on exactly how much these items cost, though it is clear that Schikaneder’s company spent a significant amount on The Magic Flute. In early October, a Hamburg newspaper printed a report from Vienna written a week before the premiere claiming the costumes and scenery cost 5,000 florins.28 An account in the Münchner Zeitung reported an even higher estimate on October 8:

For the past few days at the Wiednertheater, a new machine comedy called Die Zauberflöte has been performed, for which the scenery cost 7,000 florins and for which our famous Kapellmeister Mozart produced the music. On account of the latter two circumstances, the piece is also receiving universal acclaim.29

It is significant that this correspondent attributes the opera’s “universal acclaim” equally to its scenery and its music. Production value, including costumes, scenery, and spectacle, were apparently vital to its success.

The original libretto, which was available for purchase, provides important descriptions about how characters in the first performances may have appeared. Tamino sported “splendid Japanese hunting clothes,” for example, while the Three Ladies were veiled and carried spears.30 Papagena was “dressed exactly as Papageno” when she removed her disguise at the conclusion of Act 2, scene 23; the two men who lead Tamino to his trials appeared in black armor with fire blazing from their helmets; and Tamino and Pamina were dressed in priestly clothes at the conclusion of the second act.31 The libretto also included two engravings, one of which depicted a costume as it allegedly appeared in the premiere. Specifically mentioned in the playbill, it shows “Schikaneder in the role of Papageno according to [his] true costume,” covered in feathers and with a birdcage on his back (see Figure 4.2).32 This image of Papageno and another included in the Allgemeines europäisches Journal in 1794 (based on the costume that appeared in “Mannheim and on other large, nonlocal stages”) are nearly identical: both are covered in feathers, with a feather headdress, panpipes, and birdcage.33 Both costumes also include a feather tail, which, according to a description in the journal, could be made to swing by pulling on a string.34 The same journal included only one other engraving of a single character’s costume from the Singspiel. It shows the Queen of the Night during her famous Act 2 aria, dagger in hand and arm raised in vengeful anger, wearing a dress bedecked with stars and an elaborate star-covered veil.35

Figure 4.2 Emanuel Schikaneder as Papageno in an engraving by Ignaz Alberti, opposite page 4 of the original libretto as printed by Alberti (Vienna, 1791).

Descriptions of the scenery included in the original libretto are more detailed and more prevalent than those of the costumes, providing valuable clues regarding what audiences may have seen in 1791. Many examples come to mind: mountains that separate to reveal the starry throne room of the Queen of the Night (Act 1, scene 6); the later change of scene to a grove revealing the Temples of Wisdom, Reason, and Nature (Act 1, scene 15); Sarastro’s entrance in a chariot drawn by six lions (Act 1, scene 18); and the palm grove, where silvery trees are covered with golden leaves and seats await eighteen priests, that opens the second act. Indeed, as was often the case with Zauberopern, The Magic Flute’s action included many expensive scene changes and was accompanied by stage effects to heighten the spectacle. Some involved stage machinery, such as lifts and cloud carts for seemingly magical appearances and exits (e.g., Act 2, scene 16). Other scenes sought to intensify the dramatic effect by replicating tumultuous weather, such as that caused by a combination of wind, thunder, and lightning (e.g., Act 2, scene 5). Others still included spewing fire, as did the trials by fire and water in Act 2, scene 28.

In some cases, contemporary iconography confirms exactly the descriptions in the text. The backdrop for Papageno’s entrance (Act 1, scene 2), for instance, is described as “a rocky area, here and there overgrown with trees, on both sides are accessible hills; there is also a round temple.” This idealized scenery appears in the engraving of Schikaneder in his Papageno costume found in the libretto (Figure 4.2). The rocks, trees, and a round temple are present, but represented more closely, as they might have appeared on stage in another engraving from the early 1790s. This image (Figure 4.3) captures the moment when the Three Ladies return to punish Papageno for claiming that he saved Tamino from the serpent (Act 1, scene 3). It thus provides an idea of how Tamino’s hunting attire and the costumes of the veiled Three Ladies (albeit without their spears) might have appeared on stage.

Figure 4.3 Act 1, scene 3. Papageno: “Here, my beauties, here are my birds.” Engraving by Joseph Schaffer, ca. 1794.

This image and others created sometime around 1794 deserve special consideration as the most detailed early depictions of scenes from the opera yet known. At least six engravings – three scenes from each act – were created by Joseph Schaffer, and some scholars believe they may preserve some details of the original production – an oft-repeated assertion that is made without much discussion.36 The reasoning behind this, and even the date of their creation, are unclear. What is certain is that they were later revised slightly and included in the Brno monthly Allgemeines eurpäisches Journal as hand-colored foldouts between the months of January and July 1795. Given the similarities of costumes in Vienna, Mannheim, and elsewhere discussed above, as well as descriptions of the sets found on playbills advertising the Augsburg and Innsbruck premieres (1793) that are remarkably similar to those in Schikaneder’s text, it seems that early stagings resembled one another closely. Even though it cannot be determined to what degree these images reflect scenes from the opera as it may have appeared on any particular stage on any particular night, their value as contemporaneous iconographic evidence is beyond doubt. For this reason, all six scenes are included in this chapter (Figures 4.3, 4.4, 4.5, 4.6, 4.7, and 4.8); and they are available in full color in the Resources Tab for this volume.37

Figure 4.4 Act 1, scene 15. Tamino: “Dear flute, through your playing even wild animals [wilde Thiere] feel joy.” Engraving by Joseph Schaffer, ca. 1794.

Figure 4.5 Act 1, scene 18. [Chorus:] “Long live Sarastro!” Engraving by Joseph Schaffer, ca. 1794.

Figure 4.6 Act 2, scene 18. Pamina: “You here! – Benevolent Gods.” Engraving by Joseph Schaffer, ca. 1794.

Figure 4.7 Act 2, scene 25. Speaker: “Away with you, young woman, he is not yet worthy of you.” Engraving by Joseph Schaffer, ca. 1794.

Figure 4.8 Act 2, scene 28. Tamino: “Here are the terrifying gates.” Engraving by Joseph Schaffer, ca. 1794.

It is worth comparing the frontispiece in the original libretto to a related scene depicted in one of the Schaffer engravings. Ignaz Alberti’s engraving reveals a large vaulted hall in the background; in the foreground sits an obelisk with pseudo-hieroglyphics across from a large urn (Figure 4.9).38 A shovel and pick are propped up in the bottom right, as if they had just been abandoned after being used to uncover this long-forgotten location. Not serving any obvious function in the opera, these tools may have been added by the artist as a means of inviting the audience into this distant realm, for the engraving appears just before the title page (Alberti was also the printer and a Mason). Schaffer’s depiction of Act 2, scene 25, which shows the Speaker leading Papagena away from the not yet worthy Papageno, reproduced a more stage-friendly version of this scene (compare Figures 4.7 and 4.9). Many of the features included in the text’s engraving are also visible here: a marked obelisk on the left, a large urn surrounded by ruins or rocks, and a star dangling from the two central arches.

Figure 4.9 Engraving by Ignaz Alberti showing hieroglyphics, ruined columns, and the “vault of pyramids” associated with scenery in Act 2, frontispiece of the original libretto as printed by Alberti (Vienna, 1791).

Sources related to early performances indicate that individuals closest to the original production made alterations very early on. A copy of the printed libretto annotated by Karl Ludwig Giesecke (1761–1833), stage manager and actor in this run, still provides fresh insight into stage directions, lighting, scenery, and props.39 It reveals, for instance, that the second act duet “Bewahret euch vor Weibertücken” may have been replaced by other music or omitted altogether.40 Performance parts from the archive of the Theater auf der Wieden presumed to have been based on the theater’s copy of Mozart’s autograph support this possibility. Most of these early instrumental parts indicate that the duet was indeed omitted.41 They also include music not present in the autograph. Such is the case in the opening bars of the duet “Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen.”42 The parts also reveal that the wind chords immediately preceding Pamina’s entrance were in most cases four eighth notes rather than the dotted rhythm most commonly heard today and notated in the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe.43 Considering that Mozart left this music blank in the autograph, these parts may reveal an alteration that he or a collaborator made during rehearsals or very early in its run.44

Schaffer’s depiction of Act 2, scene 18 (Figure 4.6) may also shed new light on early performances. In the original libretto, this scene, where Pamina discovers Tamino and Papageno during the trial of silence, takes place in “a hall in which the Boys’ flying machine can operate.” Just why this engraving appears to depict a moonlit garden as opposed to the hall as described in the libretto – at the beginning of scene 13 – is uncertain. It could be a simple mistake on the part of the engraver, but this seems unlikely given that other details in the image are accurate and that all of the other engravings in this series are remarkably faithful to the depictions in Schikaneder’s text. It is possible that early performances of this scene did indeed take place in a moonlit garden, a possibility that Giesecke’s annotations may support.45 As Branscombe notes, Giesecke includes the heading “Mondtheater” (moon theater) at this point in his copy of the libretto. Parts of Schikaneder’s original stage direction are then crossed out, though it is uncertain whether Giesecke made the deletion or what exactly it meant.46 The details of Branscombe’s speculation aside, discrepancies such as these are significant, because they indicate that alterations were made during some of the earliest performances of The Magic Flute.

Even though there are some contemporary sources concerning the composition and first performances of The Magic Flute, they are not enough to reconstruct the opera as audiences might have experienced it in 1791. In any event, the nature of eighteenth-century opera renders such an effort moot. The concept of an “ideal” opera – that is, one that represents definitively a creator’s intentions – was foreign to the eighteenth century. This was not only because such works were collaborative, but also because almost all pieces were at some point altered to suit local circumstances.47 Then, as now, musicians and dramatists often emended works in response to the first few performances and for subsequent productions with different casts. The Magic Flute was no different. Sources closest to the original production indicate variety in early performances, including possible changes that involved the composer, performers, and theater management. It is the contemporary moment – that is, the context, not so much the opera itself – that helps to make sense of how music for the stage was performed and received in its moment.

Initial Reception

Early reactions to The Magic Flute provide some clues about its initial reception. In a letter to Constanze dated October 7, for example, Mozart reports:

It was just as full as always. – the Duetto Mann und Weib etc.: and the Glöckchen Spiel in the first Act was as usual encored – also in the 2nd Act the Boys’ Terzett – but what pleases me most, is, the Silent approval! – one can see well how much, and increasingly so, this opera is gaining esteem.48

In a letter dated October 8 and 9, Mozart once again speaks of the work’s enthusiastic reception, as well as of his disappointment with an acquaintance who “laughed at everything.”49 In his last surviving letter, he told Constanze how Salieri and the soprano Caterina Cavalieri (1755–1801) showered his opera with praise after seeing it together on the evening of October 13.50

Mozart might have claimed audiences praised the music, but contemporary reception was not entirely favorable. On November 6, 1791, the avid music enthusiast and diarist Count Karl von Zinzendorf (1739–1813) claimed that “the music and the sets are pretty, the rest an incredible farce. An immense audience.”51 Another early report published in the Berlin-based Musikalisches Wochenblatt that December, but dated October 9, is more critical:

The new comedy with machines, Die Zauberflöte, with music by our Kapellmeister Mozard [sic], which is given at great cost and with much magnificence in the scenery, fails to find the hoped-for success, because the contents and the language of the piece are altogether too wretched.52

Three newspaper reports published outside of Vienna and recently uncovered by Dexter Edge offer valuable information about the early reception. The first is that which opens this chapter. Published in the Münchner Zeitung and dated October 1, this earliest known report following the premiere referred to The Magic Flute by the alternative title “Die egyptischen Geheimniße” and stated that it earned unanimous acclaim and that Schikaneder spared no expense on the costumes and scenery.53 The second of these new sources, found in the Bayreuther Zeitung, transmits the words of a Viennese correspondent dated October 5. Its anonymous author states that the weather had turned unexpectedly cold, causing more people to attend the suburban theaters than either the court theaters or outdoor entertainments such as those hosted in the Prater.54 Referring to the work by the more familiar title Die Zauberflöte, this source further noted that the opera depicted an ancient initiation as depicted in Sethos (1731) by Jean Terrasson (1670–1750) and that it had been given three times to full houses. The report also states that Mozart “directed it himself, for which he was granted the third [night’s] receipts by Herr Schikaneder.”55 This is currently the only evidence of Mozart’s compensation for his work on the Singspiel. Edge has calculated that this sum may have been around 400 florins, a not insignificant amount, which may have been on top of a flat fee Mozart received from Schikaneder.56 The final, recently uncovered, newspaper source – mentioned earlier but worth repeating here – is the claim found in the Münchner Zeitung dated October 8 that the opera’s scenery cost 7,000 florins. This correspondent confirms once again that The Magic Flute was a hit with Viennese audiences, specifically attributing its success to Mozart’s music as well as the scenery: “On account of the latter two circumstances,” the correspondent writes, “the piece is also receiving universal acclaim.” Schikaneder’s decision to invest a significant sum in new sets paid off in the end, as they helped to attract theatergoers to his machine comedy.

Within weeks of the premiere, audiences could also encounter The Magic Flute outside of the theater. Arrangements of operas for smaller performing forces provide an invaluable source of gauging contemporary reception. Musicians hurried to adapt the most popular works for the lucrative market of domestic and public music-making. As early as November 1791, arrangements of unidentified numbers from the Singspiel for keyboard and voice were advertised in the Wiener Zeitung within a collection that also included arias from Wenzel Müller’s Kaspar der Fagottist.57 The printing house Artaria advertised Papageno and Pamina’s “Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen” and Sarastro’s “In diesen heil’gen Hallen” – alongside “12 new variations on the duet: Bei Männern welche Liebe fühlen from the new opera Die Zauberflöte” by Anton Eberl (1765–1807) – in keyboard arrangements on November 23.58 Versions of the trio “Seid uns zum zweitenmal willkommen” were listed on December 3.59 That these works were so quickly made available suggests that they were among the opera’s earliest hits. To be sure, “Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen” and “Seid uns zum zweitenmal willkommen” were among the numbers that Mozart claimed were usually encored in his letter of October 7. By early December, Artaria had twelve numbers from the opera on offer.60

Arrangements for larger ensembles soon followed. Roughly a month after announcing that Kaspar was available in arrangement for wind ensemble (Harmonie), the Wiener Zeitung likewise advertised Die Zauberflöte for eight- or six-part Harmonie.61 Although transcriptions for piano were important in propagating the opera’s music during the critical weeks following its first appearance, the nature of the instrument confined these arrangements to the homes of those wealthy enough to own one. Even though the creation of Harmonie transcriptions was more time-consuming and expensive than those for keyboard, these ensembles held a special place in the musical life of the late eighteenth century: Harmonien performed in every space that audiences could expect to encounter music, including the church, court, home, inn, theater, and pleasure garden, among others. Through such versatile and mobile ensembles, The Magic Flute was able to escape the boundaries of the theater, allowing its music to be heard by all strata of society across the city and eventually beyond.62

The popular success of The Magic Flute was due to many factors, including such arrangements. When the Singspiel first appeared on the Viennese stage in the autumn of 1791, no one could have foreseen just how enduring a work it would become. Alongside performances of its music in private homes and pleasure gardens, it was produced on German-language stages across Central Europe countless times within the next decade. Sequels soon followed, though none came close to replicating the success of the original.63 Few contemporaries could have predicted how the appearance of this work at a critical juncture in music history contributed to its subsequent triumph: the ca. 1800 moment marks the rise of the public as a musical force, the emergence of the Romantic image of the composer, and the nascent foundations of a musical canon. All of these factors helped to ensure performances of The Magic Flute beyond 1791 and well into the future.