German Opera in Courtly and Urban Theaters in Vienna: From the National Singspiel (1778) to Die Zauberflöte (1791)

“Vienna has its share of all the genres: French comedy, Italian comedy, Italian opera, the grand Noverre ballets, German opera, and the like,” writes Johann Pezzl in the first volume of his famous Skizze von Wien (1786).1 German opera in Mozart’s Vienna interacted with many other theatrical genres in what was widely celebrated as a rich cosmopolitan European center.2 This is not to say that the genre did not have its own distinctive musico-dramatic features and theatrical history. Vienna boasts a rich and varied German-language theatrical tradition dating back at least to the late seventeenth century, including Jesuit drama, improvised comedy in folk theaters, often interspersed with song, and musical theater performed by traveling troupes. One of the formative moments for eighteenth-century German opera was Joseph II’s 1776 announcement of the opening of the German National Theater, a spoken theatrical enterprise, which performed in one of the two court theaters, the Burgtheater, renamed the Nationaltheater. Two years later, its operatic counterpart, the German National Singspiel, was inaugurated in the same space with a new work, Die Bergknappen (The Miners), composed by the company’s first music director, Ignaz Umlauf. Featuring accomplished singers such as Caterina Cavalieri (who would later create the role of Konstanze in Mozart’s 1782 opera Die Entführung aus dem Serail [The Abduction from the Seraglio]), this court-operated company produced a number of successful works. Prominent examples include Umlauf’s Die Apotheke (The Apothecary, 1778), Die schöne Schüsterin (The Beautiful Cobbler, 1779), and Das Irrlicht (The Will-o’-the-Wisp, 1782); Franz Aspelmayr’s Die Kinder der Natur (The Children of Nature, 1778); and Salieri’s Der Rauchfangkehrer (The Chimney Sweep, 1781).

Home of the National Singspiel company, the Burgtheater was regarded as one of the finest theatrical spaces in Europe. Contemporary book and art collector Georg Friedrich Brandes, in a description from 1786, distinguishes it from Parisian theaters by its size and lighting:

It does not have a beautiful form, but it is fine, decorated in white with gold, and the fourth balcony undoubtedly much larger than those [theaters] in Paris. The lighting is also superior here. In Parisian theaters a crown hangs, which nearly fully blinds the audience members in the balconies. In Vienna two lights are installed for two balconies, through which the unpleasantness is much more dispersed, and the amphitheater is better illuminated.3

Lighting was costly and the Burgtheater’s luxury is revealed through its illumination, where candlelight glistened against the gold and white interior. Brandes emphasizes the opulence of the Viennese court, explaining that “the court here pays for everything, and has the income to do so.”4 During this initial period of the German National Singspiel, the genre was well supported and composers were provided with sufficient resources to create a distinctive German-language operatic repertory. Crucially, Joseph II was not interested in establishing a Singspiel troupe in the manner of earlier North German traditions – most notably that of Johann Adam Hiller – in which the performers were actors first, singers second. While a simple folk-like style certainly appears in late eighteenth-century Viennese Singspiel, efforts were made to recruit top singers for the National Singspiel enterprise, and a fine orchestra of at least thirty-five players was established, including strings, flutes, oboes, bassoons, horns, and, by 1782, trumpets and a kettledrum player.5 As a result, the musical writing for Viennese Singspiel from 1778 onwards does not shy away from featuring virtuosic singing and lavish orchestral timbres to paint particular scenes or situations.

Though initially successful, the German troupe at the Burgtheater proved difficult to sustain. It was disbanded in 1783 and replaced by a company that produced Italian opera buffa, one of the more popular and financially sustainable repertories. When a German company was reinstated in 1785, Emperor Joseph II issued a decree that withdrew performing privileges for all other troupes at the second royal theater, the Kärntnertortheater,6 making it the new home for the German company, a practice which lasted until 1788. In 1787 Pezzl offered the following explanation for the reinstatement of the German company: “Since a large part of the public does not understand Italian, and one wishes to also entertain them with Singspiele, a German opera is established at the same time, which performs primarily at the Kärntnertortheater.”7 The new troupe included singers such as Caterina Cavalieri and Aloysia Lange, and this period witnessed the production of Singspiele such as Franz Teyber’s Die Dorfdeputierten (1785), Mozart’s Der Schauspieldirektor (1786), Umlauf’s Die glücklichen Jäger (1786), and Dittersdorf’s Doktor und Apotheker (1786), among other works.

German opera in late eighteenth-century Vienna was not limited to the two royal theaters. Alongside the opening of the German National Theater in 1776, Joseph II also declared Spektakelfreiheit, literally meaning “freedom of spectacle,” which allowed new permanent private theaters to operate commercially. Three suburban theaters opened within a decade: the Theater in der Leopoldstadt, which was established in 1781 by Karl Marinelli; the Theater auf der Wieden, which opened in 1787 and was under the direction of Emanuel Schikaneder by 1788; and the Theater in der Josephstadt, which opened in 1788 and was run by Karl Mayer. Even with this Spektakelfreiheit, theater in Vienna was heavily censored at both the court and suburban theaters.8 Each suburban theater specialized with respect to repertory. Marinelli’s Theater in der Leopoldstadt was best known for its popular comedy in the Hanswurst tradition – popular entertainment, often improvised comedy, featuring the comic figure of “Hans Sausage.” Though of older origins, this type of entertainment had distinctly Viennese roots, which could be traced back to Hanswurst roles created by Josef Anton Stranitzky earlier in the century.9 Undoubtedly the most famous theatrical fixture of this type in Mozart’s day was the comic character Kaspar, who is described here by a contemporary:

But who, then, is Kaspar? He is the comedian at Marinelli’s theater in Leopoldstadt. I might almost say [he is] an original genius, the only one of his kind. He knows the public’s taste; with his gestures, face-pulling, and his off-the-cuff jokes he so electrifies the hands of the high nobility in the boxes, the civil servants and citizens on the second balcony, and the masses crammed together on the third floor that there is no end to the clapping.10

The actor playing Kaspar was Johann La Roche, and he appeared in many spoken plays and German operas, perhaps most famously as Pizichi in Wenzel Müller’s Kaspar der Fagottist (1791). Like Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte, this Singspiel finds its roots in August Jacob Liebeskind’s fairytale “Lulu, oder Die Zauberflöte” (1789). Emanuel Schikaneder’s Theater auf der Wieden (renamed the Theater an der Wien after a renovation in 1801) specialized in magic opera (Zauberoper) and machine theater (Maschinentheater). The space was outfitted with state-of-the-art technology and might well have been the only theater that could have accommodated The Magic Flute’s elaborate stage transformations.11 Finally, the Theater in der Josephstadt was perhaps less important for German opera at the time of Mozart but gained importance in the nineteenth century. German opera in Mozart’s Vienna thus traversed various theatrical venues, where it interacted with a wide range of theatrical genres, including French and Italian opera performed in translation, spoken theater, ballet, machine theater, and melodrama. This chapter offers an overview of German opera in Mozart’s Vienna by considering moments in three seminal works: Ignaz Umlauf’s Die Bergknappen (1778), which opened Joseph II’s National Theater; Wranitzky’s Oberon, a magic opera performed at the Theater auf der Wieden in 1789; and, finally, Wenzel Müller’s Kaspar der Fagottist, performed at the Theater in der Leopoldstadt in 1791.

Joseph II’s Sonic Jewel at the Nationaltheater: Ignaz Umlauf’s Die Bergknappen (1778)

Mining featured prominently in Enlightenment scientific, cultural, and political ideals. It served, as Jakob Vogel illustrates, to showcase the economic development of individual states and territories, embodied in “patriotic visions” of mineral collections open to the public.12 It is no surprise, then, that the Singspiel Paul Weidmann and Ignaz Umlauf created to inaugurate Joseph II’s German National Singspiel was Die Bergknappen (The Miners). Mining was not merely a regional enterprise that would add local color to an operatic work but a matter of patriotic pride. The Hapsburg Empire competed with other European states to expand its royal mineralogical collections and knowledge, and riches particular to geographic regions were fervently excavated and displayed. The premiere of Die Bergknappen on February 17, 1778, put Viennese Singspiel, like its prized geological stones, on the map of cultural activities in Europe. Musically diverging from previous German Singspiele sung by actors in traveling troupes, the royal company invested in star singers and secured a top-quality orchestra to ensure the venture’s success. The libretto lists the four soloists alongside their dramatic roles: Walcher, a mining officer, played by Hr. Fux; Sophie (his ward), played by Mlle Caterina Cavalieri; Fritz, a young miner, played by Hr. Ruprecht; and Zelda, a gypsy, played by Madam Stierle.13 The main plot concerns the young lovers, Sophie and Fritz, whose union is initially prevented by the older Walcher, who intends to marry Sophie himself. After the lovers thwart Walcher’s rendezvous with Sophie, he ties her to a tree, where the gypsy Zelda takes her place at night. Walcher is terrified at what he believes is an evil transformation, and Zelda reveals to Walcher that Sophie is his daughter. When the miners return to work the following morning, singing about retrieving gold for the state, Fritz warns Walcher of a dream in which the mineshaft collapses, but is ignored. The earth trembles, and Fritz’s vision comes true. He bravely enters the mineshaft to save Walcher, who is trapped below, and following a safe return, Walcher blesses Fritz and Sophie’s union.

One of the most striking musical forms in Viennese Singspiel is a highly virtuosic coloratura aria sung by the lead female character. In the first years of the National Singspiel, these roles were sung by Caterina Cavalieri and included Sophie in Die Bergknappen, Nannette in Die Apotheke, and, perhaps most famously, Konstanze in Die Entführung aus dem Serail. This aria represents a significant departure from earlier Singspiele, in which virtuous female characters sang simple folk-like tunes to reveal their purity; such arias distinguished these heroines from noble characters singing in a virtuosic style that exemplified the artificiality and excessive luxury of court life. Typically set in a natural realm and often compared to birdsong, this coloratura aria type employs one or two obbligato instruments with which the voice interacts, resembling an instrumental concerto.14 In a previous scene, Walcher has punished young Sophie by tying her to a tree for the night. An engraving of the scene shows Walcher shining a light on Sophie from a second-story window, enhancing the picturesque effect of the dark scene (Figure 1.1). Sophie’s isolation in the garden at night, captured in the image, contributes to the sheer theatrical effect of two arias sung in the garden. The second of these is the coloratura aria “Wenn mir den Himmel.” It features a lengthy orchestral introduction with oboe solo, effectively halting the plot and drawing all attention to Cavalieri’s agile voice. The oboe opens with what seems at first to be a simple melodic phrase in C major. Yet when the opening figure is repeated, it is transformed into a virtuosic scalar passage, displaying the technical prowess of the performer. Sophie enters with the same melody and her coloratura passages are immediately echoed by the obbligato oboe, fusing into a double display of sonic artistry (Example 1.1a).15 This bravura passagework draws to a close in the orchestra in the manner of an instrumental concerto, though the aria is not over. The audience is treated to another virtuosic display of dexterity as the second section commences with a repeat of the opening theme. The second installment is even more spectacular than the first, as the voice and oboe intermingle, sometimes passing scalar passages back and forth, and sometimes executing sixteenth-note passages a third apart (Example 1.1b). Sophie sings of the heavens granting her new life, and, in the manner of an instrumental concerto, this second section is brought to a close by a fermata on the dominant, indicating free vocal embellishment, followed by closing material in the tonic by the entire orchestra. Her heartfelt plea seems to have been heard – she is set free and Zelda takes her place tied up against the tree.

Figure 1.1 Scene from Die Bergknappen showing Caterina Cavalieri as Sophie. Ink drawing by Carl Schütz, 1778.

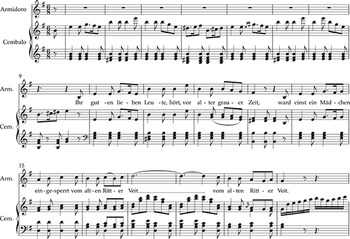

Example 1.1a Umlauf, Die Bergknappen, Sophie’s aria “Wenn mir den Himmel,” mm. 29–46.

Example 1.1b Umlauf, Die Bergknappen, Sophie’s aria “Wenn mir den Himmel,” mm. 64–78.

Whereas an aria such as Sophie’s emphasizes the importance of star singers in Viennese Singspiel, the scene in which the mine shaft collapses underscores the role of the orchestra. At first glance, one might surmise that Umlauf employs various instruments to paint natural phenomena, thereby creating a sonic play-by-play of the event. Yet a closer examination, coupled with aesthetic documents on musical painting, reveals an alternate approach. Orchestral timbre is used in conjunction with descriptions by Fritz and members of the chorus of miners. This enables the audience to experience the disaster from various human perspectives. In other words, the orchestra does not merely paint nature, it paints how humans experience natural phenomena. This aesthetic is in keeping with contemporary writings such as Johann Jakob Engel’s “On Painting in Music” (1780).16 The opening of the accompanied recitative “Die Erde bebt” (The earth shakes) features fast repeated notes on the strings, which paint the shaking ground (Example 1.2).

Example 1.2 Umlauf, Die Bergknappen, Fritz and the miners’ recitative “Die Erde bebt,” mm. 6–17.

Once the chorus of miners alerts Fritz (and the audience) that Walcher is trapped, the texture shifts to slower unison writing; Fritz comments on his decision to risk his life to save his rival. As he descends, the orchestral writing features rapid scalar passages culminating in a tremolando effect; here, two chorus members sing, “Consider the danger, how we trembled.” In other words, the audience is being asked to put themselves in the miners’ shoes, and Umlauf’s orchestral writing assists with this process of identification. It is no coincidence that we also hear from Sophie in an accompanied recitative, “Ein klägliches Geschrei klingt in mein Ohr” (Example 1.3). The oboe solo paints her anxiety as she awaits the outcome of her lover’s brave rescue mission. The orchestral writing changes to rapidly repeated thirty-second notes as she describes her shaking limbs. Here, as in the earlier scene with the miners, we are privy to Sophie’s physiological responses, which are painted by the orchestra; there is little sonic rendition of the natural disaster.

Example 1.3 Umlauf, Die Bergknappen, Sophie’s recitative “Ein klägliches Geschrei klingt in mein Ohr,” mm. 1–15.

Joseph II’s decision to secure both highly trained singers and orchestral players for the National Singspiel enabled composers such as Umlauf to produce first-rate operatic works in the German language. While many authors have emphasized the Singspiel’s apparent reliance on genres such as French opéra comique and Italian opera buffa, a closer examination of this little-known German repertory suggests a more complex situation. Viennese Singspiel engaged with other genres while at the same time rapidly striving to forge its own distinct musico-dramatic forms and conventions. The establishment of this institution served an important purpose: it made the production of German opera a matter of national urgency. The ability to hire star singers such as Caterina Cavalieri allowed for the creation of highly virtuosic concerto-like arias, which featured prominently in Viennese Singspiel for several decades. Joseph II’s National Singspiel project may not have lasted very long, but it created an impetus for, and influenced, a German operatic repertory that would flourish in urban theaters across Vienna.

Magic Opera at the Theater auf der Wieden: Wranitzky’s Oberon (1789)

Of the three main suburban commercial theaters in Mozart’s Vienna, Schikaneder’s Theater auf der Wieden exhibited the strongest predilection for theatrical works that incorporated magical themes, often featuring elaborate stage machines.17 One of the most popular fairytale Singspiele prior to Die Zauberflöte was written by composer Paul Wranitzky and librettist Karl Ludwig Giesecke. Oberon, König der Elfen premiered on November 7, 1789, and the work was quickly disseminated across the German-speaking realm, with performances in Frankfurt am Main in 1790, Mainz in 1791, Berlin and Augsburg in 1792, and Lemberg, Buda, and Pest in 1794; it spread to Linz, Krakow, Prague, Bratislava, Warsaw, and Hamburg during the mid-1790s.18 Its popular appeal can be attributed not only to its spectacular visual effects but also to various musico-dramatic features, which may be familiar to admirers of Mozart’s last opera.

Hüon, a German knight, is sent by King Charlemagne to rescue the Sultan of Bagdad’s daughter, Amande. Because the reunion of the fairy king and queen depends on the fidelity of Hüon and Amande, Oberon and Titania are keen to assist in the mission. Together with his father’s squire, Scherasmin, Hüon successfully navigates a forest and is guided by Oberon’s two genies in his search for Amande. The lovers escape Bagdad on a ship, but a strong storm renders them unexpectedly shipwrecked in Tunisia, where they become captives of Sultan Alamansor and his wife Alamansaris. Despite attempts by the Tunisian rulers to seduce Hüon and Amande, the two remain faithful even in the face of death. Oberon arrives just in time to save the pair, who have withstood all their trails, and Hüon and Amande are freed.

While it is tempting to focus exclusively on musical forms and devices, it is worth keeping in mind that Singspiel is an operatic genre that intersperses extended spoken dialogue with song. The dialogue between characters is therefore an essential component of generic analysis. And, as we shall see, theories of comedy in German opera are distinct from its Italian and French counterparts, and these differences often come to the foreground when the spoken dialogue is considered. The opening scene features the serendipitous encounter between Hüon and the comic character Scherasmin: the German knight finds himself lost in a forest, while the local has gathered a bundle of wood and is wearing “wild attire.”

(While Scherasmin wants to leave, Hüon holds him back from behind.)

Hüon Stop!

Scherasmin (falls to the ground) Oh, oh! Wrathful Mr. Death! I called you only because my bundle of wood became too heavy, so that you can help me carry it.

Hüon Simple-minded person!

Scherasmin Pardon me for my naïveté. Let me regale on roots and herbs for another five years, maybe I’ll improve by then.

Hüon Stupid, who wants to harm you! Just look at me, I am a human being, like you.

Scherasmin (remaining turned away from him) Someone else might believe you. I know very well that you disguise yourself every day with a different garment from your wardrobe.

Hüon Not true. I am an unfortunate one who has got lost here. Show me the way out of this forest and I will show you my gratitude.

Scherasmin (straightens up) Well, I will take a risk on your gratitude. But if you take me, poor devil, for a ride, then I’ll cry out and woe to you.19

This comic encounter between the young knight and the Rousseauian natural man, soon to become his companion on a mission, is designed to amplify the differences in cultivation, social class, and kinds of knowledge. Scherasmin, for instance, has gained sufficient natural knowledge to survive in this hostile environment, whereas Hüon is very much in need of assistance. The two men also recognize their common humanity, and, implicitly, the scene drives home Enlightenment ideals of human equality and freedom. As the conversation unfolds, Scherasmin (and the audience) learns that Hüon is of noble descent and that he is on an impossible mission to travel to Bagdad, where he is to collect a handful of hair from the Sultan’s beard, retrieve four of his back teeth, and take his daughter as a bride. Hüon discovers that Scherasmin used to serve his (now deceased) father and has been living in a cave in the forest for some fifteen years. Upon learning of the brave knight’s mission, Scherasmin vows to serve him. This outcome alone is a paradigmatic example of typical interactions between working and noble classes in German opera.

Whereas Italian opera buffa revels in servants “uncrowning the King,”20 often through feats of deceit, comedy in late eighteenth-century Singspiel is often generated by bringing together the most unexpected characters from vastly different social classes and backgrounds. These “unexpected encounters,” such as the one between Hüon and Scherasmin (as well as Tamino and Papageno), showcase both noble and lower-class everyday life experiences and perspectives. More often than not, they feature productive collaboration between social classes. Put another way, comic lower-class characters in Singspiel often assist, rather than derail, noble characters in achieving their missions. It is well worth noting that Singspiel performers such as Emanuel Schikaneder were superb actors, whose comic gestures especially for characters such as Scherasmin and Papageno kept audiences returning to theaters.21 In effect, the performative and comic dimensions of Singspiel came alive in the spoken dialogue, and they were reinforced by gesture, perhaps signaling the genre’s debt to the heritage of the Hanswurst.

Comic Antics and Folklike Music: Kaspar der Fagottist (1791) at the Theater in der Leopoldstadt

“One is now hungry for spectacular pieces [Specktakelstücken] … and, as such, this Magic Zither was taken up in Vienna and Prague, and was performed numerous times,” an anonymous editor writes in the 1794 preface to librettist Joachim Perinet and composer Wenzel Müller’s Kaspar der Fagottist, oder Die Zauberzither (1791).22 Marinelli’s aforementioned Kaspar figure appears as a comic sidekick named Kaspar Bita, accompanying Prince Armidoro on a mission to rescue Princess Sidi. Daughter of the radiant star-queen Perifirime, the beautiful Sidi is held captive by an evil sorcerer, Bosphoro. Following their initial encounter in an enchanted forest, Perifirime endows Prince Armidoro with a magic ring and zither, and Bita with an enchanted bassoon, to ensure the success of their mission. While the opera certainly features magical sounds and visual spectacle, including a balloon ride toward the end of the opera, the comic character Bita is undoubtedly one of its main attractions. From his comic encounters with Perifirime – when, for example, he asks if he may drown in her wine cellar if he must die – to lighthearted songs celebrating women and wine, Bita’s comic episodes are accentuated by the sound of a bassoon. Like Papageno in The Magic Flute, he needs nothing more than bread, wine, and a woman to love, and is easily scared by the sudden, spectacular transformations prevalent in magic operas. For instance, on one occasion, as he and Prince Armidoro approach Bosphoro’s castle high on a cliff, the prince turns a magic ring, thunder and lightning ensue, and the prince disappears. Terrified, Bita runs for cover, turns motionless, and then runs to the back of the stage, only to dash back out as flames emerge from the earth. As it happens, the prince has transformed himself into a little old grey man, and Bita recognizes him only by his voice.

Once the pair meet Bosphoro, Armidoro demonstrates his musical talents with the magic zither and, eventually, sings “Es hielt in seinem Felsennest,” a Romanze (a well-known song type in German opera), in the presence of Princess Sidi. This strophic song form sums up the moral of the story. While it is self-reflexive – it presents the crux of the tale at hand – it is performed within the diegesis of the opera as though it had nothing to do with the plot and is typically set in the distant past. In this instance, Armidoro sings the ancient tale of a young girl held captive in a castle tower high on a rocky cliff. A young knight passes by, hears her screaming, and promises to return at midnight to free her. That night at twelve o’clock the knight returns, throws up a rope for the girl to descend, and the story ends with a romantic kiss. Musically, the Romanze features a lilting melody in 6/8, typically beginning in the minor mode, with a turn to the major for the middle portion of the song (Example 1.4 shows the opening of the aria in a contemporary vocal score with an altered verse of unknown origin).23 First appearing in mid-eighteenth-century French comic opera, the Romanze frequently appears in North- and South-German Singspiel, often telling the tale of a young woman being rescued from captivity. The simple, repeatable, songlike quality of this form fueled its popularity, and these tunes were disseminated well beyond theaters as folksongs and circulated in popular piano-vocal scores.24 Armidoro’s performance is followed by Bita teaching Princess Sidi to dance, and naturally in Vienna she would be taught a waltz. Self-reflexive commentary ensues as Bita sings that “a waltz is in keeping with German ways” (“ein Waltz ist so nach deutscher Art”) in his Act 2 song “Ein Walzer erhitzet den Kopf und das Blut,” thereby celebrating German musical and cultural identity.

Example 1.4 Müller, Kaspar der Fagottist, Armidoro’s Romanze “Es hielt in seinem Felsennest,” mm. 1–20 (from a contemporary vocal score with altered text).

The popular folklike quality of Viennese Singspiel was not limited to solo numbers. Choruses, especially men’s choruses, feature prominently in the genre and are often sung by groups of individuals easily recognizable in society. Whereas Umlauf’s Die Bergknappen features a chorus of miners, Die Zauberzither showcases a group of hunters at the opening of the opera. Their presence is announced with hunting horns – a sound typically limited to the nobility in Italian opera – now appropriated by the bourgeoisie to showcase everyday German life. The opening chorus “Hau hau hau, auf Jäger seyd wach,” featuring the echoing sound of working men singing in the forest, presents an idealized image of working-class German citizens contributing to society through manual labor, including mining, forestry, and hunting. Initially populating eighteenth-century Singspiel, these character groups would continue to appear in operas such as Carl Maria von Weber’s Der Freischütz and in nineteenth-century German lieder.

Conclusion

Joseph II’s inauguration of the National Singspiel in 1778 provided an impetus for the production of high-quality German-language opera that would rival its French and Italian counterparts. German opera in the decade leading up to The Magic Flute (1791) was forged in a transnational context and featured a rich array of musico-dramatic forms that we encounter in Mozart’s last opera. Lavish orchestral writing, especially for scenes of heightened emotion, and concert-like virtuosic arias for the female heroine in Umlauf’s Die Bergknappen, set the stage for Mozart’s deployment of the orchestra and the Queen of the Night’s arias. Spoken dialogue inspired by German comedic practices featuring encounters between lower-class comic characters and princes enrich our understanding of Papageno and Tamino’s first exchange. The comic features of Kaspar, along with the memorable, folklike singing style, made Papageno a familiar and beloved figure. These musico-dramatic forms and features, well established in the decade leading up to The Magic Flute, clearly resonated with the public. They likely also contributed to the opera’s enduring success and can bring new insights for our enjoyment of Mozart’s last opera even today.