Was ist Aufklärung? What is Enlightenment? This seemingly innocuous question, tucked away in a footnote to an essay by an obscure theologian, Johann Friedrich Zöllner, writing in the Berlinische Monatsschrift for December 1783, managed to stimulate the interest of such luminaries as Moses Mendelssohn, Johann Georg Hamann, Christoph Martin Wieland, and Immanuel Kant. It was Kant’s “An Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment?” that remains the most widely known and vigorously debated response to Zöllner’s question. Kant initiates the discussion with this bold challenge: “Sapere aude! [dare to know] Have the courage to use your own understanding!” This, he adds, “is thus the motto of enlightenment.”1

What Is Enlightenment?

In a certain sense, The Magic Flute may be understood as a playing-out of Kant’s motto, a challenge that is at the core of Tamino’s perilous journey. But the idea of Enlightenment and the complexity of original thought encompassed under its banner demands of us that we examine the deeper questions that it asks: What view of Enlightenment is conveyed in Mozart’s music and Schikaneder’s libretto, and how does this view accord with those strains of thought and expression, of wit and sensibility, that we take to constitute the defining aura of the Enlightenment?

That Zöllner even deemed his innocent question worthy of public debate is in itself instructive, suggesting that an answer was no more evident to its contemporaries than, say, an answer to the question “What is post-modern?” might be to a generation closer in time to our own. Enlightenment: the term itself has, over time, inspired a formidable list of commentary and critique.2 There is in the first instance a distinction to be made between the condition of thought that goes by that name and, with the definite article in front of it (The Enlightenment), the historical period that it encompasses. When does it begin, this historical period? When does it end? Isaiah Berlin, with broad brush, writes of the “noble, optimistic, rational doctrine and ideal of the great tradition of the Enlightenment from the Renaissance until the French Revolution, and indeed beyond it, until our own day.” With enviable clarity, Berlin argues for the commonly held notion of the Enlightenment as a new age governed by rational thought, defined as “a logically connected structure of laws and generalizations susceptible of demonstration or verification.”3

And yet, in the midst of the German Enlightenment in the 1770s and 1780s there is manifest, notably in literature and the arts, a grain of thought and expression, of feeling – of sensibility – touching a core of human behavior, that could not be explained in purely rational terms. For Berlin, the authors whose works express and indeed ennoble this aspect of human behavior – such major figures as Herder, Lessing, J. G. Hamann, Goethe – are even perceived as figures of an “anti-Enlightenment,” their formidable contributions to the history of ideas yet recognized without the slightest demur.

To take this narrow view of the Enlightenment as exclusively the domain of reason and scientific enterprise is to misread the vibrancy of a creative imagination, in its spontaneity and wit, born in tension with the alleged certainties of rational thought. To think of the Enlightenment in purely aesthetic terms is to conjure in the mind such iconic literary works as Diderot’s Rameau’s Nephew, Laurence Sterne’s Sentimental Journey through France and Italy, Rousseau’s Confessions and Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, or the three Da Ponte librettos set by Mozart, to cite only the most widely known, in which the rigors of convention and the rule of reason are challenged in the disposition to know the world as felt experience. In all these works, the irreconcilable conflict between a rational world and the inscrutable fantasy of human creativity is understood as a function of the human condition. It is precisely this ironic view of the world that the historian Hayden White identifies in the writings of Kant, who “apprehended the historical process less as a development from one stage to another in the life of humanity than as merely a conflict, an unresolvable conflict, between eternally opposed principles of human nature: rational on the one hand, irrational on the other.”4

Irony, if not in the high-minded sense that White attributes to Kant’s view of the world, is a trope that infiltrates a reading of The Magic Flute in diverse modes. The events, the dramatic unfoldings, the apparent contradictions of its plot are well known, and so too are the seemingly endless interpretations of the symbols, real and imagined, that embellish the opera.5 The essence of Enlightenment, however, is to be sought and found less in the staging of those rituals and ceremonies that inspire so much of the music in the opera than in the play of its all-too-human personae – Pamina and Tamino, chiefly – over against these inert, monolithic structures in which they dwell.

A striking instance of this play comes early in the finale to Act 2. The theater is transformed, displaying two massive mountains, a waterfall seen or heard in the one, volcanic flame spewing from the other, an augury of the trials of fire and water about to be undertaken. An iron door is closed at either wing of the stage. Tamino, barefoot, is led onto the stage by two men in black armor. Antiphonal music, strings and trombones answered by the winds, announces their arrival, in C minor. The strings now take up a fugato in a stile antico associated with Bach, against which the Men in Armor intone, cantus-like in octaves (and doubled in the winds and the three trombones), the inscription engraved on the pyramid located above them at center stage. Their tune is a parody of the Lutheran hymn “Ach Gott von Himmel sieh darein.” Significantly, Mozart composes a final phrase that brings tonal closure, even introducing a Neapolitan sixth with its obligatory D-flat into a “phrygian” tune that to eighteenth-century ears would otherwise have seemed to end on the dominant. The chorale tune, it turns out, is one that Mozart encountered as early as 1782, for he employed it as a cantus firmus in an exercise in B minor for string quartet, very likely inspired by its extensive treatment, also in B minor, in Kirnberger’s magisterial theoretical treatise Die Kunst des reinen Satzes in der Musik.6

More than one critic has been led to wonder why Mozart, composing for an audience of Viennese Catholics, chose to appropriate a Lutheran chorale, and indeed one whose text, pleading God’s pity for wretched humanity, would only contradict the enlightened Masonic themes of the opera – though it is doubtful that Mozart, having come upon the tune among the textless examples in Kirnberger, would have had Luther’s verses in mind.7 Perhaps it was an aura that Mozart was after: an ethos, a distance of time and place that this austere music would have invoked.

“Mich schreckt kein Tod” (Death does not frighten me), Tamino bursts out, finding a D-flat, now a dissonant ninth above a dominant, that dismisses the severe tone of the chorale. And it finds Pamina’s ear, offstage. A few bars of music, three simple phrases in the upper strings that modulate to the dominant of F major, choreograph the opening of the massive door that separates them and the silent moment in which Pamina and Tamino finally embrace. A fermata prolongs the moment. Measured time resumes in a less anxious Andante. The two now sing to one another, exchanging a deeply affecting expression of love, their music redolent of another touching moment of reconciliation, the Count’s “Contessa, perdono” in the fourth act finale of Figaro; here, too, its Andante following from a fermata silent with anticipation. In both scenes, the moment is savored, joined in Figaro by all nine characters, in Flute by the two Men in Armor, who sing in a rich quartet with the lovers to “des Tones Macht” (the power of tone).

What follows is indeed a crux of the opera, in more than one sense: a final rite of initiation in the trials by fire and water that will lead Tamino and Pamina to their purification. In the run-up to the moment, Pamina urges Tamino to put in play the magic flute, crafted by her father at a witching hour “from the deepest roots of a thousand-year oak” (anticipating Sieglinde’s narrative in Act 1 of Wagner’s Die Walküre). Tellingly, it is the instrument itself, rich with symbolic and mystical allure, that is given pride of place at this critical juncture, its occult powers attending our protagonists through their trials. Yet, if this ordeal were to have any real meaning as a test of character, as evidence of a maturation of thought, if the true experience of Aufklärung is in the recognition of a process of mind no longer dependent upon mythic superstition, upon unquestioned authority, then it would appear that, at this decisive moment in the opera, an opportunity to embody the genuine experience of a truly enlightened coming of age has been sacrificed in favor of theatrical display. The moment is further tinged with irony, for this instrument, a gift from the Queen of the Night, will now serve to ensure entry into Sarastro’s realm. Here again, the opera traffics in the devices of ritual and ceremony, its principal players manipulated more as puppets than as independent, thinking beings.

What is this music that the flute plays? Whose music? Are we meant to hear in it an improvisation signifying the spontaneity of original thought, of Tamino’s mind in action, or rather a set piece programmed through some coded device penetrating player and instrument? The latter, I should think, to judge from the stiff formality of the thing and its literal repetition during the second trial. It is a drab piece, and yet it is hard to imagine how the circumstance of its performance might have led Mozart to some bolder solution – though perhaps that was precisely his intent: to display the aridity of a music deprived of true imagination. For Edward Dent, the music “has something of the solemnity of the Dead March in [Handel’s] Saul,” an observation that only underscores the dour effect.8 The libretto actually calls for an accompaniment of “gedämpfte Pauken” (muffled timpani) and Mozart has the timpanist play only in the silences between the flute’s phrases. No less telling is the accompaniment on the beats: three trombones, two horns, and two clarini. “Otherworldly” is the word that comes to mind, the trombone choir taking its customary role as the voice of the supernatural.

As the initiates emerge, the warmth of the strings embraces them, setting in bold relief that glimpse of the stark, inhospitable world that they, with their flute, have endured. “Ihr Götter, welch ein Augenblick!” (You gods, what a moment!), they calmly sing, more out of relief than in ecstasy. They have, by these lights, achieved Enlightenment.

Monostatos and Blackness

But Enlightenment, in its more human dimension, inhabits the psyches of even the lesser figures of the opera. One character easily misunderstood is the much-maligned Monostatos. Hermann Abert sees through the misunderstanding to a more complex hearing of the aria “Alles fühlt der Liebe Freuden”: “one of [Mozart’s] most original dramatic character pieces,” writes Abert, in which Monostatos “elevates himself to a character of the first order,” a man, it would follow, whom we must now take seriously. “The aria,” writes Abert, “unfolds with a sensual flickering and tingling that causes the listener’s blood to race through his veins and makes his nerves tingle.” Indeed! But then Abert must evidently convince himself that the lowly Moor is incapable of such eloquence. The opening dotted quarter-note is “brutally ejaculated,” and “the whole shaping of the melody has something disorderly, even chaotic about it. It writhes around the note c′ with dogged savagery, touching on the other degrees of the scale in a fairly primitive order.”9 To the contrary: our blood races, our nerves tingle precisely because the edginess of the music captures the anxious thrill at the brink of this moment of forbidden desire. No savagery here, no disorderly chaos.

Before the aria, Monostatos is overcome by the sight of Pamina asleep. “Und welcher Mensch … würde bey so einem Anblick kalt und unempfindlich bleiben? Das Feuer, das in mir glimmt, wird mich noch verzehren.” (What man would remain cold and unfeeling at such a vision? The fire that smolders within me will yet consume me.) His words convey a feeling no less genuine than those expressed in Tamino’s Bildnis aria in Act 1: “dies Etwas kann ich zwar nicht nennen, doch fühl ich’s hier wie Feuer brennen; soll die Empfindung Liebe sein?” (This something I can’t quite name, but I feel it here like fire burning. Could this feeling be love?) But, of course, circumstances do not allow us to equate the two. Monostatos, as he himself is all too aware, is black and on that ground alone is disqualified in this society from a relationship with Pamina. “Ist mir denn kein Herz gegeben,” he sings; “bin ich nicht von Fleisch und Blut?” (Was I not given a heart? Am I not of flesh and blood?). We are put in mind of Shylock, and perhaps the allusion is not coincidental.10 To suggest that Schikaneder and Mozart intended to hint at deeper issues of racial inequity would be to speculate beyond the limits of the evidence. This, too, is an Enlightenment moment, full of contradiction: the genuine human impulse up against the grain of conventional morality. His aria is “to be played and sung as softly as if the music were a great way off,” the libretto instructs, so as not to disturb the slumbering Pamina, even while his cunning music hints at a clandestine intent. In the end, the Queen of the Night rudely interrupts this little fantasy, and we are left only with the memory of a fleeting moment that touches something in us – not unlike Barbarina’s affecting search for that lost pin (Figaro, Act 4, scene 1) and any of those other lesser figures who come to life in Mozart’s music.

The Languages of Enlightenment

Enlightenment: Aufklärung. While the equivalence of the two terms as designators of a generalized concept is beyond dispute, it is yet worth contemplating whether the two words signify cultural domains that are not perfectly synonymous. This is more than a splitting of linguistic hairs. “Language,” as Berlin paraphrases J. G. Hamann’s notion, “is what we think with, not translate into.”11 When Mozart composes with his native German in mind, the music will convey not merely the syntax and prosody of the language but the memes deep-wired in native language and culture.

A telling display of this phenomenon comes in Tamino’s great Bildnis aria. Purged of the conventional trappings of aria – the grand ritornello, the formal repetitions, the virtuosic exploitation of voice and singer all forfeited for an immediacy of expression – the music plays more for the intimacies of cavatina. Setting aside the implausibility of his having, in a matter of moments, fallen madly in love with this miniature portrait of a woman whom he has never seen, the naïvety of Tamino’s response is trumped by a music that fires an unknown yearning, mapping his gradual recognition of a feeling – an Empfindung – that can only be love. But then comes the most remarkable passage. The music, having settled in the key of the dominant, now initiates its return toward the tonic. A pedal tone on the dominant extends for ten bars before resolution, and it is during these ten bars (mm. 34–43) that Tamino probes what are perhaps his first libidinal urges. Schikaneder’s text is worth reading as it is given in the original libretto, here showing the concluding sestet of a poem modeled on the Petrarchan sonnet (though in iambic tetrameter):

| O wenn ich sie nur finden könnte! | Oh, if only I could find her! |

| O wenn sie doch schon vor mir stünde! | If only she now stood before me! |

| Ich würde – würde – warm und rein – | I would – would – warm and pure – |

| Was würde ich! – Sie voll Entzücken | What would I? Enraptured I’d |

| An diesen heißen Busen drücken | Press her to this fervid breast, |

| Und ewig wäre sie dann mein.12 | And she’d be mine forever. |

That second couplet captures the moment: Tamino wondering what he would do, what he should be expected to do, were she to materialize before him. “Warm and pure”: the fantasy of the erotic touch comes to him in mid-sentence, an intrusion that breaks the syntax as it interrupts the effort to finish the thought. “What would I do,” he can only ask himself. The fit of Mozart’s music, the diction of these stammered thoughts, is so natural that one is tempted to imagine poet and composer working through the prosody together. But it is Mozart’s exquisite translation of Schikaneder’s paratactic construction, and especially at measures 38–44, that deserves close scrutiny:13 the heart-stopping harmonic rhythm over the pedal tone at “ich würde – würde,” the poignant D-flat appoggiatura in the first violins at the downbeat of measure 40, and C-flat at measure 41; the eros of the phrase at “warm und rein,” the G-flat giving the voice its warmth; the uptick in harmonic rhythm in the following bar, the bass moving finally from its pedal tone, capturing the climactic outburst at “was würde ich!”

The details of voicing in the orchestra are subtle and complex – and the autograph score displays not a single blemish nor evidence of a second thought. Two moments in particular capture a sense of Mozart’s keen ear for the telling signs of the inner drama. At measure 40 the horns are given a bar of silence, interrupting their offbeat pedal tones. A glance at the autograph score will confirm that this is no oversight.14 Perhaps Mozart wants Tamino’s heart to miss a beat: he has begun to formulate an answer to this vision of Pamina. And then, when the question is finally asked, there is a full measure (44) of silence. Here again, Mozart is imagining Tamino onstage, not quite ready to answer his own question. He needs a moment – and so do we. The timing is perfect. In what follows Mozart takes a necessary liberty with Schikaneder’s poem, in which “sie voll Entzücken” actually completes the broken sentence, as though it read: “Ich würde [– warm und rein – was würde ich?] sie voll Entzücken an diesen heißen Busen drücken … .” Mozart, however, must make a fresh beginning after the cadential pause at “Was würde ich?” and so the new musical paragraph begins “Ich würde sie voll Entzücken.” The convoluted construction of the poem is altered by Mozart in deference to a stage business that wants a coherent sense of formal closure: Tamino, finally bringing to mind what it would mean to press Pamina to his overheated breast.

Returning to Hamann’s notion of language as the “organ of thought” – “Not only is the entire faculty of thought founded on language … but language is also the center of reason’s misunderstanding with itself”15 – and recalling Herder’s foundational Essay on the Origin of Language – “Man, placed in the state of reflection which is peculiar to him, with this reflection for the first time given full freedom of action, did invent language”16 – as defining statements of an Enlightenment ethos, it seems all the more apposite to recognize in Tamino’s Bildnis aria its moving and subtle play with the syntactical nuances of language, poem and music locked in linguistic embrace.

The point is driven home to me by Joseph Kerman’s essay “Translating The Magic Flute,” a donnish critique of a well-known translation of the opera by W. H. Auden and Chester Kallman. In the Addendum to the essay, the task of putting Tamino’s aria into English is explored. “Mozart’s poem is wretched (in case you hadn’t known),” Kerman avers. “As poetry Auden’s is immensely better.”17 Here is Auden’s translation of these lines that we’ve been studying:

| Ich würde – würde – warm und rein – | O tell me, image, grant a sign – |

| Was würde ich? | Am I her choice? |

For Kerman, Auden’s poem fails to meet the declamatory implications of the music. He offers an alternative:

| Ich würde – würde – warm und rein – | I’ll seek her, seek her, far and near – |

| Was würde ich? | But how, indeed? |

Putting aside the central thesis of Kerman’s essay (written in the 1950s at a time when the translating of opera was a topic of heated debate), it is difficult today to read these translations without feeling that Mozart’s music, as a rehearing of Schikaneder’s language, has been traduced. And we might begin with Kerman’s notion of the “wretchedness” of the poem. Schikaneder’s poem is, pointedly, not a stand-alone sonnet and cannot be judged as though it were. Rather, Schikaneder has in view a dramatic situation: a love-struck Tamino, driven to stammered phrases at the first sight of an image of Pamina. His poem must serve to heighten the moment and afford Mozart the words that will inspire Tamino to sing. The music that he does inspire makes sense only as an expression of these words, in this language. It is the inflection of “würde” in the conditional mood, and the sonorous depth of the word as it is sung, that cannot be translated. In the service of a more elegant poetry, these reformulations by Auden and Kerman lose the isolation of “warm und rein” as a touching disturbance of thought and syntax and only point up the perfect fit of Mozart’s music to Schikaneder’s language.18

It is precisely this fluent play with syntax that, to my mind, is at the core of Enlightenment thought. There is reason behind it, of course, but language and music give the impression of spontaneous wit, of a mind in motion.

When, in the forlorn sigh at the opening of her aria late in Act 2, Pamina sings “Ach ich fühl’s,” it is as though she were echoing Tamino’s “Ich fühl es, wie dies Götterbild mein Herz mit neuer Regung füllt.” What they are feeling is another matter: for Tamino, rapture in the first stirrings of something he will come to recognize as love; for Pamina, uncomprehending despair that her feelings for him seem to be unrequited.19 To hear the two as though singing to one another across the contrivances of plot in the opera is to apprehend their music as an expression of something greater. When Pamina sings “Sieh Tamino! diese Tränen [fließen Trauter dir allein],” she actually appropriates the intervallic contour and very nearly the pitches of Tamino’s “Ich fühl es.” And there is the quality of the music to contend with. No other music in the opera touches us in quite the same way. And yet the two arias are very different. I am reminded here of the remarkable coupling in the String Quintet in G minor, K. 516, where the profound Adagio ma non troppo in E-flat (played con sordino) – what Abert aptly calls “one of Mozart’s most profoundly heartfelt [innerlichsten] pieces” – is followed directly by another Adagio, now in the key of G minor, its pulsating inner parts and pizzicato bass suggesting an arioso for solo violin, saturated in the gestures of pathos (a foil, as it turns out, for a spirited lieto fine in G major).20

If her aria suggests a similar play with the conventions of pathos, Pamina forces them to extreme ends in the final couplet: “Fühlst du nicht der Liebe Sehnen, so wird Ruh’ im Tode sein!” (If you don’t feel the yearning of love, there will be peace in death!) The chromaticism is intense, the intervallic leaps extreme. But perhaps most striking of all is an epilogue in the orchestra that seems to issue from the troubled mind of the disconsolate Pamina. The incessantly throbbing 6/8 accompaniment is abandoned, and the first violins take up a chromatic variant of the “Sieh Tamino” motive, now driven in a descent across two octaves in a complex run of hemiolas against the meter. The texture is further complicated by the staggered entry of the flute and then the bassoon, both doubling the first violins, joined finally by a new counterpoint in the oboe and second violins. This is not the usual patterning of Mozartean orchestration. The effect is dizzying. What we learn from her final phrases is that Pamina is sufficiently distraught to consider suicide. The increasing complexity of music in the epilogue, its distortion of rhythm, its bending of the Tamino motive, and the gradual amplification of texture all suggest an almost neurotic focus on a Tamino whose silence will drive her to madness.21 Indeed, when she appears to the Three Boys at the beginning of the finale, Pamina carries the dagger that she intends to employ in her own death: “halb wahnwitzig” (half mad), she is described in the libretto.

The trials that Pamina must endure, in an ignorance imposed by a powerful and misogynistic social order, arouse our sympathy precisely because they emanate from a well of human feeling. The trials by fire and water, for all the pompous ceremony that frames them, enact a ritual of Enlightenment. Pamina’s ordeal, her decision to use the dagger not in the service of her mother’s command to murder Sarastro but in her own death as an extreme act of despair at what she believes to be the loss of Tamino, is about something else.

The Two Plots

To accept the contradictions, the apparitions, the occult, and Schikaneder’s fabulous mise en scène as the apparatus of fairy-tale – following the lead of others who have written about the opera22 – is to free ourselves of the burden of having to justify the drama as a display of Enlightenment theory, strictly defined. And this allows us to come to terms with those moments in Mozart’s music where the esprit of Enlightenment can be felt: where the music touches a human (and humane) chord in its principal players, as though to contravene the immutable structure of ritual authority and mythic morality.

Indeed, it makes a certain sense to speak of two Enlightenment plots in The Magic Flute. The master plot is the familiar one, a superstructure of hierarchies, of empires pitched in darkness and light, evoking evil and good, a mapping of the journey from the one to the other as a moral and ethical coming of age, an entering into the temple of wisdom. It espouses a program for the achieving of Enlightenment and describes a world governed by its ideas. The other plot, resistant to reductive archetypes, engages the expression of inner feeling, of Empfindung. Here, dramatic action is driven not by an a priori application of extrinsic ideas but by the interplay of human beings in all their imperfections, their misprisions on display, in counterpoint against the grain of the master plot.

Was ist Auflärung? Herr Zöllner’s not-so-innocent question remains. If The Magic Flute, in its master plot, may appear to provide an answer, the wonder of Mozart’s music, its way of getting into the psyche of its singers, throws the question back at us. If there is some merit in apprehending the opera as a playing out of two plots, then perhaps one fragment of the idea of Enlightenment is to be located in a paradoxical reciprocity of the two. Returning finally to Hayden White’s formulation of Kant’s view of an Enlightenment world apprehended as “a conflict, an unresolvable conflict, between eternally opposed principles of human nature,” it is tempting to hear in The Magic Flute a similar opposition of principles. If, in its conclusion, the opera must appear to resolve its conflicts, it is into the deeper currents that underlie those conflicts that Mozart’s seductive music draws us. It is here, in these deeper currents, that a theater for the Enlightenment makes itself felt.

When it comes to exoticism – “the evocation of a place, people or social milieu that is (or is perceived or imagined to be) profoundly different from accepted local norms in its attitudes, customs and morals” – The Magic Flute is possibly the most baffling of all repertory operas.1 How to make sense of the outlandish coexistence of a Japanese hunting costume (Act 1, scene 1), a Turkish table, gondola, palm forest, and canal (Act 1, scene 9, dialogue), the vaults of a pyramid (Act 2, scene 20), six lions, three probably white male slaves, a man named after a Persian prophet (Sarastro/Zoroaster), another (in feathers) whose name sounds like “parrot” (Papageno), and a villainous black-faced Moor?2 Intensifying this mélange, the opera elides exoticism and magic – something far from inevitable in eighteenth-century opera – and it unfolds in a place of the imagination resisting the worldly concreteness of geography and historical time. In an older literature, the eclectic exoticism of the opera was tidied away through a selective emphasis upon Egyptian-Masonic allegory (on which more below). The situation is now quite different thanks to the research of David J. Buch, which reinstates the genre of “fairy-tale” opera as a historical category.3 This does much to anchor the opera in its own time and place. However, there is still foundational work to be done. Buch’s subject was the supernatural, not exoticism; understandably, then, he groups together European fairy tales and those of Middle Eastern origin. The latter shape The Magic Flute in specific ways that can be usefully teased out.

In trying to make sense of this opera, we might turn to Ralph Locke’s handsome two-volume survey of exoticism.4 This landmark study offers not only historical perspective but a framework for appraising how music contributes to the characterization “of a remote or alien milieu” – whether or not the music is exoticized.5 However, Locke only touches on The Magic Flute. This may be because it speaks less clearly to issues of cross-cultural representation than Mozart’s The Abduction from the Seraglio (K. 384; 1782), which he explores in detail. Indeed, The Magic Flute is a problem case if exoticism is taken to involve the representation of actual places, remote in place or time. Arguably, the opera unfolds in a place of the imagination, though one not without some specific historical and cultural points of reference. If it can be located at all, it might be thought of as a picturesque parkland – these were fashionable at the time and often adorned with the rocks, temples, grottos, and even pyramids that appear in the opera – or the make-believe, exotic landscape of an oriental fairy tale. Like those spaces, it is constituted by existing fictions and fantasies, its intertextual web encompassing an ever-expanding range of allusion and debt. (There is always another source for the libretto of The Magic Flute.) For these reasons, the worldly reality of the characters is attenuated. Powerfully archetypical, but not realistic in novelistic terms, they exist primarily as figures of the theater and of theatrical performance. Identification with them is of course possible, and degrees of alterity harden in the course of the story, but the fairy-tale world of the opera, eliding magic and the exotic, differs from the culturally specific setting of Mozart’s earlier “Seraglio” operas – The Abduction and Zaide (K. 344; 1780) – and from the Da Ponte operas, in which critics often celebrate realism and psychological depth.

The sense of free-floating location is enhanced by our never knowing where the characters are from. Tamino, a traveler, first appears in a “Japanese hunting costume.”6 No clear model for this garment has been identified. Possibly, Schikaneder was alluding to a seventeenth-century Dutch men’s fashion, inspired by the kimono.7 Even if this were true, however, it would not tell us where Tamino himself was from. As for Papageno, he is unable to name the region in which he lives even when asked point-blank by Tamino.

Indeed, Tamino’s urbane questioning initially baffles Papageno. In the first spoken dialogue of the opera, he comes across as an unworldly indigene, unaware of rank, of other lands, and of the strange practice of giving places a name:

Tamino (taking Papageno’s hand) Hi there!

Papageno Huh?

Tamino Tell me, merry friend, who are you?

Papageno Who am I? (to himself) Stupid question! (aloud) A man, like you. And if I ask you, who you are?

Tamino I’d answer that I am of noble birth.

Papageno That’s over my head. You’ll have to put it more simply, if I’m going to understand you!

Tamino My father is a Lord, who rules over many lands and peoples; so I’m called a Prince.

Papageno Lands? Peoples? Prince?

Tamino That’s why I ask you –

Papageno Slow down! Let me ask [the questions]! Are you telling me there are other lands and peoples beyond these mountains?

Papageno also claims to know nothing of his family and ancestry, a hint that his origins are not entirely human, but also playing into his construction as existing in a state before or outside of civilization:

Tamino Tell me, then, what region are we in?

Papageno In what region? (looks around) Between valleys and mountains.

Tamino True enough! But what is this region called? Who rules over it?

Papageno I can answer that about as well as I can tell you how I came into the world.

Tamino (laughs) What? You don’t know where you were born, or who your parents were?

Papageno Nothing! I know no more nor less than I was raised and fed by an old but very jolly man.

In this dialogue, Papageno borders on a “noble savage” – a figure of the European imagination long employed to relativize, and to critique, European social norms – here, concerning rank and territorial ownership. As Dorinda Outram observes, the exotic in the eighteenth century could even be home, viewed through the eyes of a foreign visitor.9

Locating Exoticism in The Magic Flute

At least three major literary-theatrical traditions of exoticism feed into the libretto of The Magic Flute. Any one of them might have served as the basis of an opera. Taken together, they help create a sense of narrative abundance. The first is “abduction” or “seraglio” opera that shapes Act 1, in which Tamino sets off to rescue Pamina from captivity. The second, which until recently received the lion’s share of scholarly attention, is the initiation of a prince (here, Tamino) into the secret wisdom of Isis and Osiris, a scenario involving ancient Egyptian motifs. The third centers on the magical-exotic adventures of a stock comic character, involving magic wishes and Genii (the Three Boys) – this is Papageno’s adventure, taking place largely in Act 2.

The ingenious combination of these traditions helps account for the twists and turns of the story, the relative independence of its subplots, as well as inconsistencies about the time and place of the fictional world. I begin by tugging at these three strands. In doing so, I highlight the subtle, pervasive influence of The Tales of One Thousand and One Nights (also known as The Arabian Nights) on the opera, a collection of Middle Eastern stories that became wildly popular in Europe after their translation into French by Antoine Galland between 1704 and 1712.10 In a final section, I explore what might connect the opera’s dual concerns with the religion of ancient Egypt and with nature, the realms of Sarastro and Papageno, or, to write things small, with hieroglyphs and birdsong. I suggest these dual realms offer the audience a potentially transformative encounter with the archaic, the “original,” and the divinely revealed. Adapting a rubric from Srinivas Aravamudan, I call this type of encounter “enlightened Orientalism,” a utopian mode linking the moral ideals of the late eighteenth century to an exemplary, imaginary “Orient.”11

Abduction Opera

The first act of The Magic Flute is shaped by the “abduction” plot. This had developed in the court theater of the Ancien Régime, in part because France then enjoyed close diplomatic ties with the Islamic Ottoman Empire.12 It appeared fully formed as early as Rameau’s entrée “The Generous Turk” in the Parisian opera ballet Les Indes galantes of 1735.13 Abduction opera was particularly favored, from the middle of the century, in the predominantly Catholic Habsburg Empire, where it spoke to a history of territorial and religious conflict – but also diplomacy and trade – with the Ottoman Empire. Typically, the plot involved a Christian woman held captive in a sultan’s polyamorous harem.14 In an act of gallant heroism, her European sweetheart comes to rescue her, but their escape is foiled. Facing death, they take leave of each other, only to receive unexpected pardon and freedom from the wise and beneficent sultan.

Undoubtedly, the image of the Turk occasioned anxious fantasies of political despotism, sexual excess, and violence, at one level offering an antithesis to the rhetorical ideals of the European Enlightenment. These thrillingly transgressive associations form a background of expectation for abduction operas. They also attach to Ottoman characters of low social status – such as Mozart’s most enduring pantomime villain Osmin in The Abduction. In the (un)expected denouement, however, these negative associations are banished by the sultan’s largesse, which provides a morally didactic coup de théâtre. The sense of looking beyond cultural and religious differences to discover a transcendent or universal morality is part of the enlightened orientalism of such works (and was epitomized by Voltaire’s Treatise on Tolerance [1763] and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s five-act drama Nathan the Wise [1779]). In the arts, at least, displays of religious hatred were out of fashion. There were other expedients, too. It was not wise, in court-sponsored opera, to present unflattering images of rulers, whatever their background.

The conventions of abduction opera are summoned, but also transformed, near the beginning of Act 1 of The Magic Flute as Tamino sets off heroically to rescue Pamina from her captivity at the hands of an Eastern-sounding patriarch and presumed villain, Sarastro. The Queen of the Night sets him on this mistaken course when – in one of many acts of nested storytelling in the opera – she relays through the Three Ladies the tale of Pamina’s “abduction by a powerful, evil demon”:

First Lady She sat all alone on a lovely May morning in a refreshing cypress grove, always her favorite place to visit. The villain crept in unobserved.

Second Lady She heard, and –

Third Lady Besides his evil heart, he can metamorphose into every imaginable form; in this way, he got Pamina too.

First Lady This is the name of the royal daughter, so you may worship [her].

In this scene, both the technique of telling a story within the story and the reference to an “evil demon” show the influence of the Thousand and One Nights (henceforth Nights), a “household title” of the eighteenth century, whose influence on German-language theater is only now coming to light.15 Locke, emphasizing its importance as a repository of motifs, notes the prominence of “sultans, harems, harem guards, slaves from sub-Saharan Africa, [and] summary executions.”16 Pushing Locke’s observation a bit further, the Nights brokered the enduring marriage of the supernatural and the exotic.

Tamino, who seems already to know about operatic abduction plots, falls instantly in love. He indulges in an ardent aria of erotic sensibility (Act 1, scene 4, “Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön”), in which – recalling Belmonte’s parallel aria (“O wie ängstlich”) in The Abduction (Act 1, scene 5) – he reports forensically on the sensations of love and imagines an ecstatic union with his beloved. He sets off to rescue Pamina, arriving like a valiant knight at the boundary of Sarastro’s realm. There, he is rebuffed by the voice of a guard (Act 1, scene 15), just as Belmonte was barred entry to Pasha Selim’s estate by Osmin (The Abduction, Act 1, scene 2).

It turns out that an escape attempt is already in progress – Papageno has beaten him to it. As Papageno and Pamina take flight, Sarastro arrives to the sound of a triumphal chorus with trumpets and drums (Act 1, scene 18) – “Long live Sarastro!” This follows abduction conventions – Pasha Selim is also celebrated as a ruler by a stage chorus at a parallel moment of The Abduction (Act 1, scene 6). From this point, principal motifs of abduction opera are much compressed, but faithfully reproduced. Pamina and Tamino are brought before Sarastro; Monostatos gleefully anticipates his reward and their punishment (cf. The Abduction, Act 3, scene 5), but instead he is reprimanded for his viciousness (cf. The Abduction, Act 3, scene 6). Sarastro hints that he had hoped to receive Pamina’s love, but grants her freedom to love Tamino (cf. The Abduction, Act 3, scene 9).

While abduction operas typically conclude at this point, The Magic Flute uses Sarastro’s beneficence as a starting point for the rest of the drama, acting as a doorway into his Egyptian realm of sacred wisdom. At this point, Sarastro sheds his association with the Ottoman sultan of abduction opera. The implied confrontation of Christianity and Islam gives way to the discovery of a more ancient, spiritual system hidden behind the curtain of Act 2. A stage direction evokes the startling change of scenery as the curtain rises:

The theater is a palm forest, all the trees are silvery, the leaves are gold. [There are] 18 seats of [woven palm] leaves, on each seat is a pyramid and a big black horn set with gold. In the middle is the largest pyramid, and the largest trees. Sarastro along with other Priests come in solemn steps, each holding a branch of palm. The procession is accompanied by a march played by wind and brass instruments.

Abduction motifs do not completely disappear in Act 2, however. Instead, they are displaced onto Monostatos, through whom they are also given considerable complexity. The fact that Sarastro keeps slaves and uses Monostatos – a Mohr – to oversee them (and to keep tabs on the captured Pamina) is consistent with the harem fictions of the Nights, though admittedly not with Mozart’s The Abduction. Correspondingly, and perhaps in the absence of any established musical codes for characters of specifically African identity, Mozart employed a subtle version of his alla turca style for Monostatos’s notorious aria “Alles fühlt der Liebe Freuden.” He does not employ Janissary percussion (the bass drum, triangle, and cymbals used in The Abduction), but retains the piccolo – also used in The Abduction for “Turkish music” – and melodic fingerprints, including the arabesques that turn in semiquavers around the tonic and dominant pitches.

However, Schikaneder complicated Monostatos’s characterization with some antiracist, and even antislavery, motifs. Already, back in Act 1, scene 12, a relativistic perspective is introduced. When Papageno and Monostatos first catch sight of each other’s strange appearance they simultaneously beg for mercy, in a stuttering duet, each believing the other to be the devil incarnate. In the following dialogue, however, Papageno begins to reflect: “Aren’t I foolish, to get so frightened? There are black birds in the world, so why not black people.” In the first strophe of his aria “Alles fühlt der Liebe Freuden” (Act 2, scene 7), Monostatos takes this further, questioning prejudice against his complexion, asserting the universality of his desire for love, and – implicitly – milking the audience for sympathy:

Everyone feels the joy of love, / bills and coos, fusses, hugs and kisses, / but I must go without love / because a black man is ugly! / Is there no sweetheart for me?

This sentiment, if not the actual words, recalls the then famous slogan of the British and American campaigns for the abolition of slavery – “Am I not a man and a brother” – an epithet that Josiah Wedgewood incorporated in his antislavery medallion of 1787. Mozart’s choice of a neutral, C major march rhythm in this aria avoids lending Monostatos the radical alterity that the dramatic situation imparts to him as Pamina’s potential rapist. He is kept safely at a distance by pianissimo and lontano performance directions. Messages about Monostatos are thus extremely mixed.

Racism and misogyny collide. Immediately before this aria, Monostatos’s rues that, as a black man, he is not allowed to love a white woman. However, this moment of enlightened critical reflection (it sounds like a soundbite from Voltaire or Lessing) is undercut by the fact that Pamina detests his unsolicited attentions and that Monostatos is justifying a crime he has not yet successfully committed. In a nocturnal garden, signifying folly and desire, he spies on Pamina, who sleeps in a bower of flowers:

Ah, so there’s the elusive beauty! And so they wanted to beat the soles of my feet just on account of this precious plant? So, I’m to thank my lucky stars that I’m still here with my skin intact. Hm! What was my crime exactly? That I was infatuated with a flower that grew on foreign soil? And what man, even if he hailed from a gentler clime, would remain cold and unmoved by such a sight. By heavens! The girl will rob me of my reason yet. The fire that glows within me will yet consume me.

Monostatos’s reference to a “fire” within him parallels Tamino’s love-struck reaction to Pamina’s portrait (Act 1, scene 4). Both men experience “fire” as they gaze at Pamina, who is rendered passive by portraiture and by sleep. Adding further complexity, this type of romantic desire overtakes both men involuntarily. In binding them to Pamina, it resembles the bonds of servitude, on the one hand, and Papageno’s magic music, on the other – this, too, acts invisibly and at a distance. In these ways, slavery is elaborated metaphorically, becoming part of the poetics of the opera, rather than a subject of critique.

The Mysteries of Isis and Osiris

A second major strand of exoticism involves Prince Tamino’s journey of spiritual development, culminating in his initiation into the Mysteries of Isis and Osiris within an ancient Egyptian pyramid. This venerable literary topos preceded the rise in the nineteenth century of an archaeological, forensically documentary Egyptology. That mode was spurred by the Napoleonic invasion of Egypt and Syria (1798–1801), the rediscovery of the Rosetta stone in 1799, and deciphering of hieroglyphs in 1822, and involved the accumulation of positivistic knowledge – facts – but also an increasing sense of alienation. Paradoxically, ancient Egypt became more “remote and alien” as more was discovered about it. Edward Said detected this imperialist objectification in the stage sets of Verdi’s Aida, but saw in Mozart’s The Magic Flute an earlier, enlightened mode of sympathetic and cosmopolitan identification.17 Only a detailed history of staging and iconography could speak to the influence of the pharaonic turn on later stagings of Mozart’s opera, but Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s designs from 1815, drawing on the Description of Egypt (1809–21) produced by Napoleon’s large contingent of scholars, are generally regarded as landmarks in this process.18

In Vienna in 1791, ideas about, feelings for, and uses of ancient Egypt were based on Classical sources, Biblical narratives, and literary fiction. References to Egyptian wise men and magicians in the Old Testament (e.g., Exodus 7:11) suggested that the Egyptians received divine wisdom through direct revelation. According to Acts 7:22, this knowledge was transmitted to the Israelites: “Moses was learned in all the wisdom of the Egyptians and was mighty in words and in deeds.” This wisdom was bound up with the practice of magic (in a way that now seems counterintuitive). When pharaonic priests test Moses and Aaron, they transform Egyptian staffs into snakes (Exodus 5:7) – an ambivalent image that resonates with the opening of The Magic Flute.

There were several major Classical sources for the Mysteries of Isis available to an educated elite in Vienna in 1791. Audiences did not need to read the classics, however, to get the gist because these canonical sources were widely diffused through historical writing, fiction, and household encyclopedias. In the genealogy of The Magic Flute, the most important of these was book 11 of Apuleius’s Metamorphoses, written in Latin in the second century AD, also known, in English, as The Golden Ass. It was a landmark because it was the first novel to fictionalize initiation into the Mysteries of Isis as part of a hero’s story of adventure and development. Lucius has dabbled with magic and inadvertently turned himself into an ass. He is eventually released from that humbling state when Isis appears to him in a dream, declaring:

I am the progenitor of nature, mistress of all elements, first-born of generations … the peoples on whom the rising sun shines its rays, both Aethiopians and the Aegyptians, who gain strength by ancient doctrine, worship me with the appropriate ceremonies, [and] call me by my right name, Queen Isis.19

As in The Magic Flute, the actual wisdom of Isis is never disclosed, emphasis falling instead upon an initiatory ritual (in Lucius’s words) “performed as a rite of voluntary death and salvation attained by prayer” – a direct corollary of Tamino and Pamina’s trial in Act 2, scene 28, in which courage, love, and music substitute for prayer.20 Like Tamino, Lucius does not eat or drink during his initiation (a motif of self-abnegation comically ignored by Papageno). Students of The Magic Flute will notice Apuleius’s reference to a palm tree with golden leaves and to a procession in which the initiated carry insignia (cf. the stage direction at the beginning of Act 2). Also bearing directly on the opera are Isis’s references (in the quotation from Apuleius above) to ceremony, ancient doctrine, the sun, and the elements. The fact that Isis appears to Lucius in a dream is evocative of the second act of the opera, which is unveiled like an alternative reality and involves an almost hypnogogic slowing of time during the Procession of the Priests and Sarastro’s aria “O Isis und Osiris.”

Apuleius’s Metamorphoses shaped two texts often mentioned as sources for The Magic Flute: Jean Terrasson’s novel Sethos, published in French in 1731 – ostensibly as the translation of an ancient Greek manuscript – and Ignaz von Born’s essay “Über die Mysterien der Ägypter” (On the Mysteries of the Ancient Egyptians), published in Vienna in the Freemasons’ periodical Journal für Freymaurer in 1784. Peter Branscombe highlights “numerous similarities” between Sethos and Schikaneder’s libretto, via the German translation of the novel by Matthiaus Claudius (1777–78). Among them are the words of the two men in black armor in Act 2, scene 28, which are drawn directly from Sethos, and the Priests’ singing of hymns to Isis and Osiris. He also shows that in describing Tamino’s trials, Schikaneder probably drew vocabulary directly from Born’s essay: “‘Verschwiegenheit’ (‘discretion’), the phrase ‘rein und lauter’ (‘clean and pure’) … and ‘Heiligthum’ (‘sanctuary’) and ‘Fremdling’ (‘stranger’).”21

In publishing his essay, Born employed a sleight of hand. By the middle of the eighteenth century, a branch of German-speaking Masonry had taken Sethos to heart as an authentic representation of the Egyptian cult of Isis and used it as a template to develop its own rituals of initiation.22 Perhaps these Masons even half-believed Terrasson’s claim to be translating an ancient manuscript. In an act of faux naïveté, Born used Sethos and Classical sources – including Apuleius – to suggest a continuous tradition between the ancient Egyptian mysteries and Freemasonry. This was entirely circular logic in the service of the prestige and imaginary lineage of a beleaguered, secret fraternity.

Born’s argument subsequently fostered a reading of The Magic Flute as a secret handshake. This involved a fine leap of logic: if Schikaneder could be shown to have drawn on Born’s essay, then the opera could be shown to be both “about” Freemasonry and a celebration of it. An alternative, more cautious perspective is that the self-mythologizing and theatrical rituals recently developed in Viennese Freemasonry helped give Schikaneder the idea for some scenes in Act 2 – without those scenes necessarily being “about” Freemasonry. That is, Freemasonry offered source materials, inspiration, even a mediating step for Schikaneder’s staging of initiation into the Wisdom of Isis, but it did not “own” that subject. To read the entire opera as Masonic allegory involves tidying away many inconvenient questions: Are the opera’s high-moral ideals not eighteenth-century commonplaces (“Wisdom,” “Nature,” and “Reason”)? Why does Sarastro keep slaves? Why does a hereditary prince end up on top? Why write Pamina into the story?

The sound-world Mozart created for Sarastro’s realm also frustrates the essentialism of Masonic readings. Sarastro’s aria (No. 10) is a prayer offered to Isis and Osiris for the protection of Pamina and Tamino. As an adagio bass aria with chorus, it is an extremely unusual type of piece. This alone is sufficient to impute a sense of difference to the music, without the need for any quasi-ethnomusicological evocation of ancient Egyptian (or Masonic) music specifically. The inclusion of three trombones – instruments strongly associated with the operatic underworld and the voices of spirits – situates Sarastro’s voice between the human and divine, life and death. The low vocal register, the omission of violins, flutes, and oboes, the quiet dynamic, and the richness of divided legato violas convey subterranean sensations. When the all-male choir enters in measure 25, the melody finds itself in the higher of the two bass parts (bass 2), covered by repeated notes in the two tenor parts above – an eerie, sepulchral effect. The character is mysterious, hovering between light and dark. Sarastro’s initially poised, diatonic melody is disturbed by a chromatic turn as he refers to “danger” (mm. 21–22), even though at this point the music is modulating, optimistically, to the dominant. Then the tone darkens with modulations to minor keys – including a pictorial plunge in unisons to the tonic minor for a reference to the “grave” (m. 35). In these ways, Mozart conveys the danger of Tamino’s impending trial (described below).

Papageno’s Wishes

A third theatrical tradition of exoticism that shaped The Magic Flute concerns Papageno. It involved the exotic-magical adventures of a stock comic character, loveably idiotic and sometimes mischievous. Buch’s survey of operatic supernaturalism suggests this scenario developed early in the eighteenth century, in improvised Italian comedy, the commedia dell’arte, and from there entered French comic opera (opéra comique). The trigger, again, was Galland’s French edition of the Nights.23 Though the chronology and transmission are not entirely clear – much comic theater was semi-improvised, by traveling troupes, and the music rarely survives – this tradition was apparently adapted in Vienna, under the headings of Zauberkomödie, Zauberlustspiel, and Mährchen. This is the repertoire that incurred Leopold Mozart’s disapproval during the family’s sojourn in Vienna in 1767–68 as (implicitly) unenlightened, fostering superstition, and failing to instruct: “the Viennese, generally speaking, do not care to see serious and sensible performances, have little or no idea of them, and only want to see foolish stuff, dances, devils, ghosts, magic, clowns … witches and apparitions.”24

Papageno’s adventure takes a specific form, however, one not observed to date and drawn from the Nights: it unfolds as a series of wishes granted by Genii (here “the Three Boys,” who, though named as such within the libretto, are listed as “drei Genien” in the dramatis personae). A well-known example of this type of adventure is “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp.” Aladdin’s wishes are for safety and freedom (he finds himself imprisoned underground by a sorcerer), for food (he and his mother are poor and hungry), and for a bride (specifically the sultan’s daughter). He gains these through magic objects (a ring and a lamp) that contain genii, released when the object is rubbed. They present themselves to Aladdin as “slaves” and exist only to do his bidding. He is not particularly deserving of his good fortune – destiny thrusts it upon him.

Without suggesting dependence on this story specifically, it is notable that Papageno is also a somewhat unlikely recipient of good fortune, magically arranged. When we first meet him, he sings of his happiness, but reveals his desire for a wife. He is given a box of magic bells by the Three Ladies – supernatural beings – which he uses to make this wish and others come true. During his attempt to escape with Pamina from Sarastro’s palace (Act 1, scene 17), he uses the bells to make venomous Monostatos dance offstage – in this way (like Aladdin) he ensures his safety. Later, in Act 2, scene 16, when he and Tamino find themselves alone in Sarastro’s palace, the Three Genii bring Papageno not only his bells but a table laid with food and drink (“ein schöner gedeckter Tisch”). Rather unheroically, he tucks in, praising the cook and the wine cellar. In Act 2, scene 22, he finds himself frightened and alone, when a voice (“the Speaker”) informs him that he has failed the trial – but that he can grant him a wish:

Speaker [You failed the trials.] Therefore, you will never feel the heavenly joy of the initiate.

Papageno Not to worry, there are many people like me. A good glass of wine would be my biggest pleasure right now.

Speaker Do you not have anything else you wish for?

Papageno Not so far.

Speaker Your wish is my command! – (He leaves.) – (A large cup, filled with red wine, appears out of the ground.)

Papageno Hurray! That’s great! – (drinks) Wonderful! – Heavenly! – Divine! – Ha! I’m so happy that, if I had wings, I’d fly to the sun. – Ha! – This does my heart good! – I’d like – I wish – yes, what then [do I wish]?

This dialogue leads directly into Papageno’s aria “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen” (Act 2, scene 22), which, in context, conveys his wish for a sweetheart or wife. (Clearly, it took a glass of wine for this wish to come out.) In this aria he plays his magic bells with increasing virtuosity on each strophic repetition. That form, involving three stanzas, is apt to convey the classic threefold repetition of wishes in fairy tales. Meanwhile, the two-tempo structure – which sees Papageno lurch repeatedly from a relatively sedate Andante in 2/4 meter into an Allegro in 6/8 – suggests his mounting, if intoxicated, desire. As soon as the song is over, his sweetheart appears as if by magic, albeit in disguise as an amorous aged woman. Less than enthusiastic, he promises to be faithful – at least (he whispers) until someone prettier comes along.

His trials are not yet over. In adapting the formula of the wish from the Nights, Schikaneder introduced an enlightened element of moral development – Papageno must prove himself worthy of his wishes coming true, or at least pay for his weaknesses. When we next meet up with him, he is suicidal (Act 2, scene 29). His potential bride was whisked away by the forces of magic because his promise to her was not truly meant. Theatrically, he threatens to hang himself – by now perhaps anticipating the Genii will come to his aid. Just in time, they do, reminding him to use his magic bells. He does, uttering a wish between virtuosic bursts on his glockenspiel:

Ring, little bells, ring! / Bring my sweetheart here! / Ring, little bells, ring! / Bring my little wife here!

With the literalness that characterizes the magic wish of the Nights, the Three Boys bring Papagena from the sky. Implicitly, Papageno has learned his lesson.

Birdsong and Hieroglyphs

From this outline of three main strands of exoticism in The Magic Flute, it is evident that the opera, like the Nights, contains many stories.25 There are more that might be drawn out. Sometimes they are miniatures, told in the strophic lyrics of arias – as when Papageno fantasizes about catching young women in cages and trading them for sugar; sometimes they are fleeting moments of narrative, as when Pamina discloses that her father carved the flute in a “magic hour” from a thousand-year oak, or when Monostatos secures from the Queen of the Night a promise that Pamina will be his when they bring down the realm of Sarastro. Sometimes (again, as in the Nights) they are abandoned mid-course, like Tamino’s plan to rescue Pamina from Sarastro and return her to the Queen of the Night. Amid this exuberance, or narrative excess, two realms stand in perplexing disconnect: the spiritual wisdom of ancient Egyptian mysteries and Papageno’s habitus – the realm of nature. However, they are united, conceptually, as archaic, ancestral places – realms of hieroglyphs and birdsong.

Hieroglyphs appeared in the frontispiece to the published libretto of the opera and are strongly implied in its description of Tamino’s purifying trial (Act 2, scene 28). (See Figure 4.9 earlier in this volume.) This trial is undertaken as a condition of his initiation but also, in another sense, as part of it. The libretto describes a rocky landscape with two mountains, stage left and right. One, shrouded in dark mist, contains a noisy waterfall; the other, back-lit with hell-red fire, houses spitting flames. Sombre, archaic music is heard, evoking an atmosphere of labyrinthine grief. Two men in black suits of armor – I imagine them like medieval knights in princely coats of arms – lead Tamino to a towering pyramid center stage. It is inscribed with an illuminated script which is “read” aloud to Tamino by the Armored Men but is surely what they sing: “Whoever wanders this path of woes, is purified by fire, water, air, and earth.”26 Their melody, a Lutheran chorale tune, is from another time and place – an exotic relic that Mozart dug out from a treatise on counterpoint published twenty years before by the Bach student Johann Kirnberger. The script on the pyramid is presumably in hieroglyphs. A German inscription on the pyramid would be rather incongruous, and Prince Tamino would hardly need that to be read aloud by knights from a bygone age.

Declaring that this vale of tears holds no fear for him, Tamino is rewarded by reunion with Pamina. They will wander the dark path together. (The libretto is of little help here, and with the original costumes and sets lost, we have to imagine how this would have been staged.) The royal couple are shored up by their virtuous love and by Tamino’s piping of his magic flute, carved (Pamina discloses) from “a thousand-year oak.” For this oldfangled instrument, worthy of Methuselah, Mozart provided a generic march tune: a venerable type of piece that Johann Friedrich Sulzer (writing in the early 1770s) related back to the earliest uses of “measured tones … to support the body’s strength in physical ordeals.”27 As they emerge from darkness into blinding light, Tamino and Pamina exclaim, “You Gods, what a moment! We are granted the happiness of Isis.” This sublime moment of illumination suggests the revelation of transcendental spiritual knowledge, the cult of Isis and Osiris melding with the biblical narrative of creation in one of the Enlightenment’s favorite motifs: fiat lux (“Let there be light!”).

This mind’s-eye reconstruction suggests that ancient Egypt in The Magic Flute is not (only) a place marked by alterity but (also) belongs to a fantasy of origins, continuity, and rebirth. Initiated into an archaic – but ongoing – legacy, Tamino is spiritually reborn. His future path, and the social order he will rule over, are transformed by the experience of this remote time and place. Within the fictional world at least, this exotic locale has a transfiguring effect, catalyzing historical progress and social transformation.

This encounter writes into the opera, or inscribes, a theory of art that possessed broad period currency. As David Wellbery puts it brilliantly, if elliptically, in a study of Lessing’s Laocoon (1767), “the Enlightenment attributes to art the capacity to renew the life of culture by reactivating its most archaic mechanisms.”28 While Lessing’s archaic was Greek antiquity, The Magic Flute displaces classicism with fantasies of ancient Egypt and (semiwild) nature. These are twinned, and subtly but differently exoticized, within the fiction. They are captured in my title’s allusion to birdsong and hieroglyphs, which are styled, within the opera, as divine, original, and possessing (re)generative power.

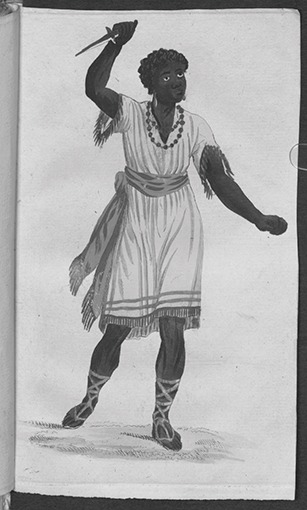

Though excluded from the Mysteries of Isis, Papageno is also a figure about origins – especially musical ones.29 He both is and is not exotic. We know what he looked like, because Schikaneder included a picture of himself playing the part in the libretto sold at the earliest performances in the Theater auf der Wieden (Figure 4.2 earlier in this volume). And quite a look it is! With a headdress of feathers and a bird whistle that looks like a panpipe, he has a remote resemblance to older iconography of North American first peoples. In another early illustration he is shown playing a hammered dulcimer slung from his neck in the manner of a “Hungarian-Gypsy” (Romany) musician.30 However, living alone on the edge of a forest – in a straw hut, he tells the inquisitive Tamino – he belongs more to a type of hypothetical savage imagined by Enlightenment theorists in their library-bound explorations of mankind in the state of nature. Such a figure existed at the vanishing point of the rustic, the exotic, and the antique, providing a way of imagining human nature before it was shaped by diverse local customs and manners. As Dorinda Outram notes, for most of the eighteenth century, the opposite of culture was not another culture but nature.31

It is in this context that we can hear his bird whistle and his own chirpy singing as allusions to the origins of music. Just as hieroglyphs were often regarded as “holy writing,” even as a divine gift containing original spiritual wisdom, so divinely created birdsong had long been cited as the origin of music – not least by the same Jesuit priest, Anthansius Kircher, who wrote prolifically (if erroneously) about ancient Egypt.

There were newer theories, too, but the idea that mankind learned music from the birds was just too alluring to put aside entirely. Papageno, himself named after and resembling a tropical bird, reactivates or alludes to this theory. He is clearly the opera’s natural musician. The libretto and music occasionally suggest he is not only a bird-catcher but a birdman. When Tamino first encounters Papageno, he doubts he is fully human:

Papageno Why are you looking at me so suspiciously and mischievously?

Tamino Because – because I have my doubts if you are human.

Papageno Why’s that?

Tamino Judging by your feathers, which cover you, I think you’re – (goes towards him)

Papageno [Surely] not a bird? Stay back, I say …

Much later, in his love duet with Papagena (Act 2, scene 29, finale, “Pa-Pa-Pa”), Papageno regresses from words to a single syllable, and from melody to beating, repeated notes. His melody comes to resemble that of a bird breaking into song. Comically mimetic, and probably accompanied by a feathery mating dance, this extraordinary number, coming close to the end of the opera, intensifies covertly avian features of Papageno’s earlier music (magical and otherwise). Rhythmically mechanical, involving melodic gestures of outrageous simplicity, intensely repetitive – and yet utterly magical – the parrots’ duet unlocks a theory of musical origins that spills out from this number into the opera as a whole. Arguably, even the Queen of the Night is touched by this stylized birdsong in the repeated notes and arpeggios of her coloratura in “Der Hölle Rache.”32

In his two solo arias (“Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja” and “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen”) Papageno’s idiom is an ingenious, Mozartian fantasy of aboriginal music. Both numbers are strophic lieder, an aria type that was common for socially lowly characters in comic opera, and which (like that Lutheran chorale melody in Tamino’s trial) was said to suit the musically untutored. Both of Papageno’s arias belong to established types of lied – the first is a working song (which tells us his occupation and is sung as he goes about it); the second is a drinking song (which he sings with a large cup of wine in his hand, and it keeps spilling over from an Andante in duple meter to a rushing – specifically hunting – 6/8).33 Both lieder are based on the rhythmic and melodic profile of the contredanse – a rustic, stamping, line dance – employ pastoral keys (G major and F major, respectively), and employ prominent open, perfect fifths between bass and melody. In “Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja” these extend into another pastoral fingerprint, the horn-fifth figure (m. 4), highlighted by a pair of orchestral horns. Extremely catchy and distinctive, these songs also possess that “impression of the familiar” that the composer-critic Schulz, inspired by Herder’s celebration of old vernacular poetry, equated with the German Volkslied (literally, people’s song).34 Both of Papageno’s lieder can be heard as stage songs – as if he were singing them to himself – even though the libretto does not make this completely explicit. Heard in this way, they tap into a period idealization of orality, which came to the fore in Herder’s preface to his Volkslieder of 1779. The fact that Papageno’s magic music appears improvised – in “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen” each strophic repetition occasions ever more fantastical variations of the same material – also ties in with the aesthetic premium placed upon natural spontaneity.

As an art of strophic repetition, and variation, Papageno’s magic music reaches back to birdsong. Activating or, more cautiously, alluding to “archaic” beliefs about music and natural magic (music’s power to influence people and things), this stage music offers a (fictional) glimpse of the art before its scientific and aesthetic rationalization. The “renewal” (in Wellbery’s sense) this offers is the re-enchantment of music – an art that had officially shed much of its metaphysical and magical power in the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in the intellectual contexts of scientific rationalism and the aesthetic doctrine of mimesis (according to which music could imitate or represent the magical but not be it). Similarities between the magic music of the opera and the rest of the score – highlighted by Buch in an incisive analysis – can be explained in many ways, but potentially they re-enchant the music of the opera as a whole. The timing, in 1791, is tantalizing, as music was soon to be returned to metaphysics (a sort of philosophical supernatural) by German romantic aesthetics. Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder’s landmark Outpourings of an Art-Loving Friar was published only six years later.

Conclusion

Why The Magic Flute drew upon, but also overthrew, the abduction plot is intriguing, but unknowable. In terms of dramatic effect, it adds surprise and wonder to the encounter with ancient Egyptian motifs in Act 2. Those motifs, far from serving the putatively liberal philosophy of Freemasonry, end up reaffirming the rights of a hereditary prince to a position of leadership – implicitly to the sovereignty for which he was destined by birth. While it is too easy to draw direct links between operatic plots and political contexts, it is difficult not to recognize a counterrevolutionary element in the Egyptian turn of The Magic Flute. In 1791, Austria was winding up to war against the forces of an expansionist French Republic in defense of the Ancien Régime. Though Austria did not officially declare war on the French Republic until 1792, it had already acted militarily in January 1791 to reinstate the rule of the hereditary bishops of Liege, ousted by the Revolution of 1789. Then, in July of 1791, Austria committed to join Prussia in defending the monarchic government of Louis XVI in the so-called Declaration of Pillnitz. By September 30, 1791, when the opera premiered, Louis XVI and his family, foiled in their attempted flight, were under arrest and France had a new Republican constitution. As an argument in favor of enlightened but absolute monarchy, as a celebration of sovereignty, The Magic Flute was of this moment.

The abandonment of the abduction plot, at least in Tamino’s story, may also reflect the opera’s political-military context. The image of a beneficent sultan was probably untimely in 1791 when Austria was once more at war with the Ottoman Empire (the Austro-Turkish war ran from 1788 to 1791). Mozart, who from the end of 1787 was employed as royal chamber composer, supplied a bellicose and patriotic song, the “Lied beim Auszug in das Feld” (K. 552; August 11, 1788), intending to whip up support for this unpopular conflict.35 In this context, perhaps, the opera was dragged by the seat of its Turkish trousers into another, less politically sensitive, pre-Islamic realm. These observations about the opera’s military contexts are not central to this chapter, but they are important to understanding the immediate context in which it was conceived, performed, and understood.

To conclude, in this chapter I have offered an archaeology of the opera’s diverse exoticism in a study of its poetics, not its politics. In doing so, I have come to realize that the exoticism of The Magic Flute – which, by standard definition, constructs an “alien” world, “remote” in time, place, and cultural norms from Vienna in 1791 – is itself rendered all the more exotic by the passage of time. The Magic Flute constructs the remote and alien in ways that are remote from (admittedly unstable) twenty-first-century cultural norms. For this reason, exoticism is not contained within the opera’s fictional world, but informs all encounters with The Magic Flute today. The canonization of this opera, its status as a monument and masterwork, fosters the falsely proprietorial sensation that it belongs to us and is about us.

In its original form, however, it is lost to us. We must bring it forth through research, acts of the imagination, and – possibly revisionist – performance. Not only are the original sets and costumes lost; it was produced for a stage quite unlike that of modern opera houses. Narrow and deep, the stage was capable of near instantaneous transformations of scene via a rope-and-pulley technology that sent backdrops scuttling back and forth. One scene, with all its furniture, could be prepared behind another, and then revealed, in seconds. The effect was integral to the opera’s fairy-tale and exotic character. With trap doors and aerial machinery, characters could appear and vanish, as if by magic. On modern stages, these sensational effects are impossible, creating a mismatch between the theatrical fiction and its mode of representation. Anglophone and other non-German-speaking students of the opera face additional losses. The German dialogue, which reveals so much about the characters’ identities, is often abbreviated in performance; nor is it readily available, in full, in translation. Engaging historically with The Magic Flute involves a conjuring act or, to use an orientalist metaphor, a magic lamp through which the opera is constituted, in the mind’s eye and ear, as at once familiar and strange, an exotic experience of something that is not simply there.

Fans of detective stories will remember that in both Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express and A. Conan Doyle’s “The Five Orange Pips” the difficulty confronting Poirot and Holmes is not one of too few suspects or too few clues, but too many. The Magic Flute has for much of its history posed a similar problem to those who have investigated the possible sources of its plot, characters, and meaning.

Several contributing factors spring immediately to mind. Information about the origins and gestation of the project remains unusually murky. Further, unlike the court-sanctioned operas that preceded it in Mozart’s career, The Magic Flute made its initial home in a theatrical environment to which historians of opera have devoted relatively little attention. The collaboration with Schikaneder was also an unusual one for Mozart in that he was working with not just a librettist but also the commissioner of the work, the director of the theater where it was to be performed, and a principal in its first cast. But most of all, the text that Mozart’s music brought to life grew out of no single, identifiable source.

Although our training has historically equipped musicologists to deal with musical sources rather than literary texts and their sources, we of course know that operas begin not as musical scores but as literary narratives, and that where those narratives come from and how they are shaped and reshaped for the musical stage is as much a part of an opera’s pedigree as its musical genesis. This should be especially apparent for a work like The Magic Flute, destined as it was for a particular kind of musical stage, one on which words are not poesia fatta per musica but a combination of the spoken and sung delivered by actor-singers trained and practiced in, theatrically speaking, a bilingual tradition.

From the very beginning, efforts to identify the sources of The Magic Flute found themselves entangled in problems of interpretation, more often than not instigated by the well-nigh irresistible urge to uncover some hidden meaning beneath its motley, child-friendly surface. Ideally, historians of any art form should try to distinguish work-to-interpretation issues from source-to-work problems. In reality, however, they are always intermingling. For Mozart’s earlier operas (Così fan tutte appears to be a notable exception) the presence of a single, clearly identifiable model helps regulate inquiry into both how a work came to be and what it has come to mean. The absence of a single-source model for The Magic Flute, however, opened to a tribe of hunter-gatherers a potentially limitless store of possible antecedents. Interest at first centered on fairy tales and other magic operas, but later, as the opera grew in stature, the stockpile expanded to include plays by Shakespeare and Calderón, the Bildungsroman, and legends from Classical antiquity.