Guitars Are Made for Men’s Bodies—Not This One: Designing the Glitterbomb for Female and Small-Frame Players

Demasculinizing an iconic Western symbol of masculinity is not an easy task. Perhaps it is an impossible one. Historically, electric guitar luthiers, “innovators and company executives were men,”1 and as such, guitars have always been designed by men, for men. As a female player, over the years, this presented numerous cultural and social problems—and technical ones, too.

Guitars—all guitars—felt awkward, ill-fitting, and painful to play. From a six-year-old struggling to reach the strings as my arm dug into the upper body side ribs of my dad’s Fender dreadnought, to the grazes on my left shoulder after hours of school cover band practice with a weighty Gibson Les Paul, the guitar strap cutting in deeper, scraping and chafing away with every struck chord. Eventually, at twenty years old, I settled on a humble Fender Bullet bought for £90 in Cash Converters on Kilburn High Road, London. As one of the smallest, lightest, cheapest, and most structurally basic guitars Fender ever made, its narrow neck and streamlined body made for more comfortable playing than anything else I’d encountered.2

Fast forward to 2016. My band, Glitoris, is signed to an independent label, and I am writing, recording, and touring nationally. The trusty Fender Bullet is getting a decent workout and holding up to the task, until one show in Naarm, when its bridge3 was damaged. After returning to Ngambri and calling around for a guitar tech, I found Rusty Vance, a well-known guitar luthier in the area. A conversation ensued, and after watching us play at the ANU [Australian National University] Bar that December, he offered to make me a custom guitar. Rusty was passionate about guitar design and, having constructed all kinds of electric guitars, from Gretch-like hollow bodies with f-shape cutaways, to much heavier, SG-style editions, Rusty was keen to address the absence of high-quality electric guitars for female, non-binary, and small-frame players.4

We set to work on what became the Glitterbomb.5 Much of the initial design was based on the dimensions of the Fender Bullet. The neck was the most important feature, and we settled on a light Queensland maple, reinforced with carbon fiber, and an African ebony fretboard, both of which are lightweight. The frets are narrow in spacing, and the action sits low with a graph tech nut cut for 52/10-gauge strings. The main body is a lightweight mahogany, and its pinched-in waist sits at 19 centimeters—the perfect dimension between my thigh and ribs for comfortable play when seated.

Wide necks, broad side body ribs, and overall weight are all technical barriers to women and small-frame players. However, the typical structure of the main electric guitar body itself and the way it digs into our breasts is perhaps the biggest—and most painful—impediment to playing. Many women guitarists have complained about this. As far back as 1997, Mavis Bayton6 included the testimonies of Frances Sokolov,7 Kate and Juliet from Oxford band Twist, and Anna from Sub Rosa, each of whom attested to the discomfort associated with large-bodied electric guitars digging in while playing. The Glitterbomb was designed specifically to address this major and prohibitive issue. The narrow waist combined with a large, scooped-out cutaway on the back of the upper body not only keeps the guitar well away from chest height, but also means its lower body “rolls” on—and around—the hip. Pelvic and rib bruises no more. Since owning this guitar, my playing has improved beyond recognition, simply because I am playing a comfortable guitar.

For me, playing the electric guitar is a creative necessity, as well as an act of reclamation. When I perform, the guitar is simultaneously a weapon and a shield; I am physically strengthened, empowered, and protected by it. The technical demasculinizing of the electric guitar is one means of dismantling “the patriarchal power structure” that dominates the electric guitar industry.8 Another means of undermining its masculinity is diverting from the homogenous, classic car-like ivories, reds, and sunburst color schemes by spraying the finished entity in bright green glitter. The guitar did, however, need a final hallmark, so we marked the fifth fret with a Glitoris signature in fluorescent, glow-in-the-dark Luminlay: \*/

Introduction

In The Segovia Technique,1 Vladimir Bobri describes what the guitarist’s gesture should be in order to reach virtuosity. This search for perfection in the “classical” gesture was, however, questioned by another type of virtuosity: that of rock music. “The success and continuation of the electric guitar come from the innovative musical language it birthed,” André Duchossoir underlines while specifying that an electric guitar “is not just an amplified acoustic guitar with the help of electricity. Its specific characteristics in the fields of sonority, power, and sustain or even left-hand and right-hand play make it an instrument of its own kind.”2 We can then better understand that a classical guitarist such as Andrés Segovia, who could be considered a traditionalist, has castigated this new instrument, dubbing it “an abomination, underlining, in a contemptible manner, the great difference existing between the various types of six-string ‘boxes.’”3 The feeling, expressed by Segovia as quoted by Duchossoir, is in line with that of Bobri, who sees in the classical guitar a “handmade thing of beauty” versus “the morass of folksy twanging, sentimental balladeering, and brutality of the electrified horned monsters.”4

It is a fact: through its specific properties, the electric guitar has afforded new technical gestures and new ways of playing. Robert Springer reiterates:

The evolution of rural blues and city blues toward a true urban form happened under the effect of the electrification of the main instruments, especially the guitar, which radically changed the way of playing and the musical thought. At the end of the 1930s, certain jazz and blues guitarists such as Charlie Christian and T-Bone Walker had begun the transition … the repercussions were significant. The piano, then, had to confine itself to a background role calling upon its percussive possibilities rather than its melodic possibilities.5

Mainstream or scholarly, the twentieth century had a great number of guitar “genres” rub shoulders with one another:

A vast range of styles and techniques make up guitar music. These include the … blues, rock and avant-garde virtuosity of Jimi Hendrix, the heavy metal playing of Eddie Van Halen, the anti-virtuosity of “indie-guitar” and punk, the classically oriented music of John Williams and Julian Bream, the flamenco-based improvisations of Paco de Lucia, the jazz, jazz-rock and Indian music explorations of John McLaughlin, “world music” productions by Ry Cooder, Ali Farka Toure, and Pat Metheny, and performances by Vishwa Mohan Bhatt and Debashish Bhattacharya in the field of Indian classical music.6

The “classical” gesture does not, however, completely vanish from the rock scene. Not to fall into the cliché of categorizing genres, it might be in 1970s prog rock that “classical standards”—both in virtuosity and in the actual gesture—are more obviously observed. Either in Genesis (with Steve Hackett) or in Yes (with Steve Howe), we encounter some of the most compelling examples of classical writing in rock albums. Two tracks, in particular, seem to represent this movement: “Mood For A Day” (Yes, 1971) and “Blood On The Rooftops” (Genesis, 1976).7 Howe and Hackett use nylon strings on these tracks instead of an electric guitar or a steel-string acoustic guitar, reminding us even more of the “classical” sound and gesture.

Even if certain rock musicians adopted a “classical” gesture with a “rock” sound, others continued to break the rules of this idealized gesture. This transformation can also be explained by the technical innovations that came alongside the electric guitar’s evolution: the use of distortion, feedback, and various effects allowed the electric guitar to produce new sounds.

In return, contemporary music captured the rock “gesture” and these new sounds. In this regard, the examples of Vampyr! by Tristan Murail (1984), La Cité des Saules by Hugues Dufourt (1997), Zap’Init by Claude Ledoux (2008), and, in some way—because responding to other questions—Gonin’s A Floyd Chamber Concerto (2014) are good examples. My experience of arranging and conducting a version of In C by Terry Riley (Dijon, Atheneum (2004) and Paris, Philharmonie (2016)) played entirely on the electric guitar, an interpretation centered around tone—what tone to choose and how to combine tones to give the piece a nonuniform dimension? What effects to put into place?—shows that the porosity of popular and art music genres today, and the interaction of the “gestures” associated with them, has become an established phenomenon.

The ambition of this chapter is to synthesize a reflection aimed at putting the instrumental gesture at the center of musical creation. It does not deny or hide all it owes to the works of Steve Waksman8 or Robert Walser,9 or the works accomplished during the international conference Quand la guitare [s’]électrise held at the Philharmonie de Paris in 2016, whose proceedings can now be accessed.10 In the first part of the chapter, this study briefly covers the electrification of the guitar and its consequences for guitar manufacturing and development of the effects dedicated to guitar playing. I will then focus on the possible range of crossbreeding the classically inspired instrumental gesture before addressing Eddie Van Halen’s contribution. Finally, I will consider the influence that the rock virtuosos’ legacies, from Jimi Hendrix to Van Halen, brought to the instrumental gesture and the tones used by composers of contemporary repertoire, whose knowing use of technique has furthered the hybridization of genres.

A New Gesture to Serve a New Virtuosity, and the Influence of Lutherie

In The Art and Times of the Guitar, Frederic Grunfeld states that before Hendrix, Charlie Christian had already profoundly changed the status of the electric guitar. “There is the guitar before Christian and the guitar after Christian,” Grunfeld writes.11 Waksman adds: “The electric guitar was a different instrument, offering sonic possibilities that allowed the guitar to break away from its standard role in the jazz rhythm section … Christian’s achievement lay in tapping into the electric guitar’s potential, not simply to make his playing more audible, but to expand the instrument’s vocabulary.”12

But electricity is not the only reason that led to a change in the instrumental gesture. The actual changes in guitar manufacturing are significant factors. The disappearance of the sound box led to the creation of the solid-body guitar (Gibson Les Paul, Fender Telecaster, or Stratocaster, to name only the most iconic ones) and modifications to the body itself, with simple or double cutaways that allowed the player to reach the frets closest to the base of the neck on electric models, a feature later incorporated on certain acoustic models. The whammy bar was also added on some electric models, such as the Bigsby or Floyd Rose models, whose influence on technical gestures and virtuosity is fundamental. “Electric guitarists have been notable for the attention they have devoted to the quality and the character of the sounds they produce, and for the creative use of electric technologies in the making of popular music,” writes Waksman.13 Within the evolution of a gesture linked both to evolution in technique and guitar manufacturing, Jimi Hendrix undoubtedly played a major role. Kevin Dawe and Andy Bennett note: “In 1966, African-American guitarist Jimi Hendrix arrived in Britain and took electric blues playing to an altogether different level, single-handedly pioneering a new style. Superlative manual dexterity was combined with a skillful manipulation of volume and electronic effects units such as the wah-wah pedal, the fuzz tone, and the univibe.”14

The video of Hendrix playing the Troggs’ “Wild Thing” at Monterey Pop Festival in 196715 is significant here. Hendrix utilizes his guitar as a sound generator: using the distortion and feedback in these few introductory minutes, he only plays with volume and the whammy bar.

“Classical” perfection requires an elaborated technical gesture that must meet certain requirements and postures, aiming at making the gesture efficient. The ideal position of the body is thus presented; Bobri underlines with details: “The instrument is supported at four points: the right thigh, the left thigh, the underside of the right arm, and the chest. The incurved bout of the guitar rests on the left thigh. The right upper arm rests on the broadest part of the guitar body, leaving the forearm hanging completely free.”16 This ideal position changes with the so-called folk guitar. Its larger sound box requires rebalancing the gesture (in the sitting position). However, Bobri presents the “bad habits to be avoided”17 with drawings that show cross-legged guitarists resting their guitar on their right leg (and not on the left). These drawings remind us of one of the only pictures we have of Robert Johnson, sitting in a suit and wearing a hat, his right leg holding his guitar over his left leg (Figure 8.1).

Figure 8.1 Robert Johnson

Another noteworthy example is the position that the thumb is supposed to hold on the neck. When Bobri, while translating the thinking of Segovia, writes, “one will never acquire a good technique by squeezing the neck between the thumb and the index finger [; this gesture] immediately shows a mediocre guitarist,”18 I cannot help but think about the “mediocrity” of a guitarist such as Jimi Hendrix who notably barred the neck with the help of his thumb. This gesture allowed him to create bass lines with his thumb and give his other fingers greater freedom of movement (Figure 8.2), as demonstrated in Hendrix’s “Purple Haze” (1967), “The Wind Cries Mary” (1967), or “Little Wing” (1967).19

Figure 8.2 Jimi Hendrix’s right hand

We could also mention Robert Smith’s habit when he reaches the highest notes on his guitar, contradicting once again the “purity” of the technical gesture advocated by Segovia. In this position, reaching close to the body of the guitar, we observe that when Segovia reaches for the 12th to 19th frets “without contortions,” he leaves his thumb on “the edge of the neck.”20 On the contrary, Smith, especially when he plays on his Fender Bass VI, moves his thumb under the neck; it is then not held by the pinch created by the thumb and other fingers; it simply rests on the base of the thumb itself (Figures 8.3 and 8.4) (see, for example, the live performances of “Picture of You”).21

Not to be forgotten, the right hand also led to questioning the ideal posture: the use of the pick, of course, but also, and most importantly, the presence of the whammy bar and the possibility of reaching volume and tone knobs. Jimi Hendrix is significant here once again, but one of the most striking cases is Jeff Beck.22 His gesture is reminiscent of “classical” fingerpicking, and the presence of the whammy bar and volume knobs induces a slight modification of this position. Let me illustrate: the thumb, index finger, and middle finger are used to pinch strings, and the ring finger (and sometimes the middle finger) handle the whammy bar, while the pinkie handles the volume knobs and tone.23

Guitarists adjusted their hand position not only due to a lack of proper training but out of the pursuit of distinctive and desirable tones. The effort to obtain a pure sound was the goal of one of the most famous inventors in the history of the electric guitar: Les Paul. Steve Waksman writes:

The solid-body electric, as conceived by Les Paul, was intended primarily as a means of regulating the musical production of noise and ensuring that melodic or tonal purity would not be overtaken by perceived sonic disorder. Through Paul’s efforts and influence, the electric guitar achieved new levels of standardization and uniformity of performance, and the clean, sustaining tone produced by his innovation would become a key component of the “new sound” he created with his wife and performing partner, singer Mary Ford.24

However, the use of distortion and its integration into rock music is one of the biggest sonic paradoxes to have existed since the invention of recording, as Greg Milner notes:

At the exact moment that high fidelity was ramping up, a new music was developing around an aesthetic that valued low fidelity. While the world was thrilling to the possibility of a recording that was so “correct” it was indistinguishable from that which it recorded, a new generation, out of either choice of necessity – and usually both – was learning how to record things “wrong.”25

To put it in other words, instead of trying to obtain the purest sound possible, the idea was rather to “soil” the electric guitar tone, to make it harsher, more bitter, less smooth, and to play with it to create, beyond new sounds, new technical gestures.

Virtuosity, Bach, and Heavy Metal – or the Electric Technique to Serve a Classical-Writing-Inspired Music

What impact do these distinctive gestures and guitar manufacturing techniques have on the virtuosity of the instrument’s players?26 They can be measured in different ways. They sometimes have no actual impact on the virtuosity, so to speak (as exemplified by Robert Smith), but the inherent specificities of the electric guitar (lutherie, emission of sound through amplification) will induce new gestures that might, in turn, have an impact through a subtle back and forth influence on the instrumental gesture, integrated by contemporary composers.

The most obvious example might be tapping—mostly two-handed tapping—a groundbreaking technique, albeit not entirely new. Eddie Van Halen developed and popularized this playing mode with “Eruption” (1978), although its roots are relatively old. Prior to Van Halen, one can find this technique used by other rock guitarists, although less systematically, such as: Randy Resnick in the late 1960s; Kiss’s Ace Frehley, notably at the end of his solo for the song “Shock Me” on their 1977 tour;27 and Steve Hackett, who used it sporadically in “The Musical Box” (Genesis, 1971) and “Dancing with the Moonlit Knight”28 (Genesis, 1973). One cannot ignore the close links this playing has with classical composition. Eddie Van Halen, Joe Satriani, Steve Vai, or Yngwie Malmsteen—to cite only these four virtuosos (all being heavy metal guitarists)—all have classical influences in their playing. Robert Walser reminds us: “From the very beginnings of heavy metal in the late 1960s, guitar players had experimented with the musical materials of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European composers.”29 Mentioning the renowned virtuoso Yngwie Malmsteen, Walser even underlines: “In the liner notes for his 1988 album Odyssey, heavy metal guitarist Yngwie J. Malmsteen claimed a musical genealogy that confounds the stability of conventional categorizations of music into classical and popular spheres.”30

In these liner notes, Malmsteen acknowledges he owes a debt to J.S. Bach, Nicolo Paganini, Antonio Vivaldi, and Ludwig Van Beethoven, admitting that he soaks in their influence, inspires himself with their compositions, and “tries to reproduce their melodic essence,” but that he “never learned any of their compositions by heart.”31 It is impossible for Malmsteen to play Paganini’s 24 Caprices for violin on a guitar because he says, “you can reach a phenomenal velocity with a bow, far beyond anything you can achieve with a guitar.”32

Let us remember that this musician—just like Clapton, Gilmour, Andy Summers, and Mark Knopfler, among others—was honored with his own Stratocaster signature model by Fender. Among other technicalities, this model has a conchoidal touch, a curved neck close to that of the Indian sitar. “With a curved touch … the contact with the strings is far better, the sound richer and the possible velocity, much faster.”33 Malmsteen does not, however, use this guitar’s specificity to change his way of executing bendings by pressing on the string, for instance, rather than pushing it upwards or pulling it downwards, explaining: “I always pull my strings the Clapton way! When I do, that is … [s]ince it is a technique I use rather rarely.”34

Van Halen’s “Eruption” and the Creation of an Archetype

“Where would we be as guitarists if Eddie Van Halen had not existed?” asks Matt Blackett in the Guitar Player special tribute issue following Van Halen’s passing.35 If one can say there is a way to conceive electric guitar playing before and after Jimi Hendrix,36 one cannot deny the crucial importance of another musician: Eddie Van Halen. There is, undeniably, in the world of rock music in general and in that of heavy metal in particular, a time before and after Van Halen. “Eruption,” the second track on their self-titled debut album (Van Halen, 1978), held people’s attention to the point that it became almost a paragon, the reference for heavy metal solos. The track almost did not make it on the album, according to Eddie Van Halen himself: “Eruption wasn’t really planned to be on the record … I was warming up, you know, practicing my solo and Ted [Templeman, the album’s producer] walks in. He goes, ‘Hey, what’s that?’ I go, ‘That’s a little solo thing I do live.’ He goes, ‘Hey, it’s great. Put it on the record.’”37 Elected Best New Talent by the readership of Guitar Player in a 1978 poll, Van Halen (who won Best Rock Guitarist for five straight years between 1979 to 1983) had an enormous impact on rock guitar playing.38 He further developed the two-handed tapping technique, a technique he did not create but brought to an unprecedented level of sophistication.

If lutherie is paramount in this evolution, let us not forget about electronics, especially in the crafting of pickups. Guitar journalist Matt Blackett underlines once more: “Ask yourself this: What if Eddie Van Halen hadn’t been around to put a PAF in the bridge position of his Strat?”39 Blackett refers to the pickup type called “humbucker,” placed by Gibson on their guitars in the late 1950s, and whose acronym is PAF (Patent Applied For), as the label under these pickups stated. The PAF model has since become a myth relying on those first models, pending industrial certification. In number 66 of Guitare et Claviers, Eddie Van Halen explains how he loved the sound of a Gibson Les Paul but that its shape did not fit his body and style of playing. This is why he mounted a PAF pickup on a 1961 Stratocaster, in order to obtain “a sound that has nothing to do with a Fender.”40 Van Halen then used a Stratocaster replication by Charvel on which he mounted “an old Gibson PAF that was recoiled [his] own way and placed very, very close to the bridge to get a high-pitched sound.”41 He had also changed the frets to have large Gibson ones.

Regarding guitar manufacturing, one of the main differences between electric and acoustic guitar is the integration of a whammy bar (vibrato) on certain electric guitar models. The first tremolo bars date back to the 1930s. Their use became a crucial element in some guitarists’ playing: Jeff Beck, Jimi Hendrix, David Gilmour—what would a David Gilmour solo be without double bends and the use of vibrato?—and Eddie Van Halen. There are several models of whammy bars: the Bigsby or the one found on the Stratocaster (the renowned “synchronized tremolo”) or Jazzmaster (the “floating tremolo”). As a reminder, here is a short definition of a tremolo: a “tremolo system” refers to all components of the tremolo unit, which can include the tailpiece, the bridge, the nut, and the tremolo bar. And it helps to know that the terms “tremolo bar,” “vibrato bar,” and “whammy bar” are all used interchangeably, as are the terms “bar” and “arm.”42

Eddie Van Halen was one of the first guitarists to try out a model of a tremolo system which was destined to have great success with guitar players, especially in heavy metal: the Floyd Rose model. Invented by Floyd Rose in 1977 from Fender’s “synchronized tremolo,” the Floyd Rose Locking Tremolo, simply known nowadays as the Floyd Rose, is another type of “synchronized unit.”

Van Halen recalls: “[Floyd Rose] would arrange to come meet and show [me] a thing that seemed as secret as a new atomic weapon … He told me it was a vibrato locking system.”43 The problem with this new system was that the guitar would go out of tune too often. Eddie Van Halen recommended to Rose that he adapt his invention to a system already existing on violins (which Van Halen played as a child), an instrument that could be tuned “with a finger while still playing [thanks to fine tuners placed behind the bridge, see Figure 8.5] … Once he understood what I needed, he patented it and I never saw him again.”44

Figure 8.5 Fine-tuning system on the tailpiece of a violin.

Moreover, and here’s an important point: Van Halen not only advanced virtuoso techniques but also innovated sonically by integrating effects, especially at the beginning of his career with MXR pedals, experimenting particularly with phaser and flanger effects:

I use two Echoplex. I use a flanger, just for little subtle touches … And I use a phase shifter, a Phase 90 – MXR, I think. It doesn’t really phase; it just kind of gives you treble boost, which I like … I use a Univox echo box, and I had a different motor put in it so it will go real low and delay much slower.45

Van Halen goes on about the end of “Eruption”: “All that noise? That’s a Univox echo box, which I put in the bomb. Did you see that thing?”46

Guitar manufacturing, electronics, and effects all have a considerable impact on the way guitar players “create” their own sounds and their own gestures. These gestures and this new virtuosity then (sometimes) become models for others to follow. Van Halen’s influence, through his gesture and his sound, on guitarists such as Steve Vai, Paul Gilbert, or Nuno Bettencourt and, more widely, on the whole generation of “shredders” who appeared in the 1990s, is indisputable.47

Contemporary Music and the Electric Guitar: A Shift Toward Hybridization?

The use of the electric guitar in contemporary (art) music has been common for some time. Pierre-Albert Castanet48 notices it in works as diverse as Francis Miroglio’s Tremplins (1968), Hugues Dufourt’s Saturne (1968–1969), and Philippe Manoury’s opera 60ème Parallèle (1997). “These composers let Jimi Hendrix’s instrument ring and resonate with the most striking effects,”49 overusing feedback (Ledoux, Murail, for example) as a gesture that is now an integral part of the instrument’s technical vocabulary. We can add to this list La Cité des Saules, pour guitare électrique et transformation du son by Hugues Dufourt (1997), or, of course, Vampyr! by Tristan Murail (1984).

This last piece could undoubtedly be considered one of the founders of a hybridization between contemporary writing and instrumental “gestures” originating from rock music, particularly metal. We are, in fact, witnessing a sort of pendular swinging that, from metal guitarists’ classical inspiration—but not necessarily guitaristic—shifts back into the world of art music by integrating new stylistic elements crafted into a rock-writing searching for new tones, gestures, and textures.

In this way, the interpretation by Flavio Virzi of Murail’s Vampyr! is visually unsettling. Albeit equipped with a pedal board (BOSS GT-10) and an electric guitar with a vibrato (in this case, an Ibanez, a brand often played by “shredders”) playing a constantly distorted sound with a pick, Virzi chooses a body position that is usually seen with classical guitarists (the guitar is resting on the left leg, same neck inclination, etc.).50

Another example is Claude Ledoux’s 2008 Zap’s Init. One can clearly see in the YouTube video51 of the interpretation of the piece by Hughes Kolp (to whom it is dedicated) that the musician’s gesture is directly inspired by rock music and very far removed from the “classical” archetypes—most notably the position of the thumb but also the right hand. From a technical point of view, the website of the publishers of the score clearly specifies which types of instruments and effects are necessary to interpret this piece of work, as stated below:

A “rock” type electric guitar, equipped with a vibrato bar, potentially with a sustain effect. Use a guitar pick (certain passages can, others must be played without a pick)

An octaviation pedal (octivator to be programmed to add the inferior octave)

A Dunlop-Crybaby type pedal (or similar pedal)

A WR3-Guyaton type pedal (or Boss autofilter, or similar pedal)

An expression pedal plugged into distortion (or possibility to adjust the distortion via the volume button of the guitar)

BASE SOUND:

Sound with distortion + compressor + light delay or reverb.

SPATIALIZATION:

Stereophonic diffusion preferred. A mono sound can be used with a flanger stereo for a light dephasing effect for the spatialization.52

If Zap’s Init can still be considered a guitar piece in the pure sense of the word, such is not the case with La Cité des Saules by Hugues Dufourt (1997). In order to interpret this piece,53 Yaron Deutsch uses a Roland FC 300 MIDI controller plugged into an ADA MIDI Tube Guitar pre-amplifier, a TC Electronic multi-effects device, and two Marshall amplifiers (stereo output). The words “Dufourt la cité des saules” can be seen on the TC Electronic multieffects unit, confirming that the guitarist preprogrammed effects loops before recording the interpretation. Ultimately, the guitar is just an excuse, a sonic source meant to be transformed to the point that the instrument itself is barely noticeable. These two brief examples show two types of virtuosity: one (Dufourt) is essentially connected to the sound (let us remember that Hugues Dufourt belongs to the spectral movement), and the other (Ledoux) is linked more to the “virtuoso” gesture in a common sense of the word: speed of execution, complex technical gesture, but also sound transformation.

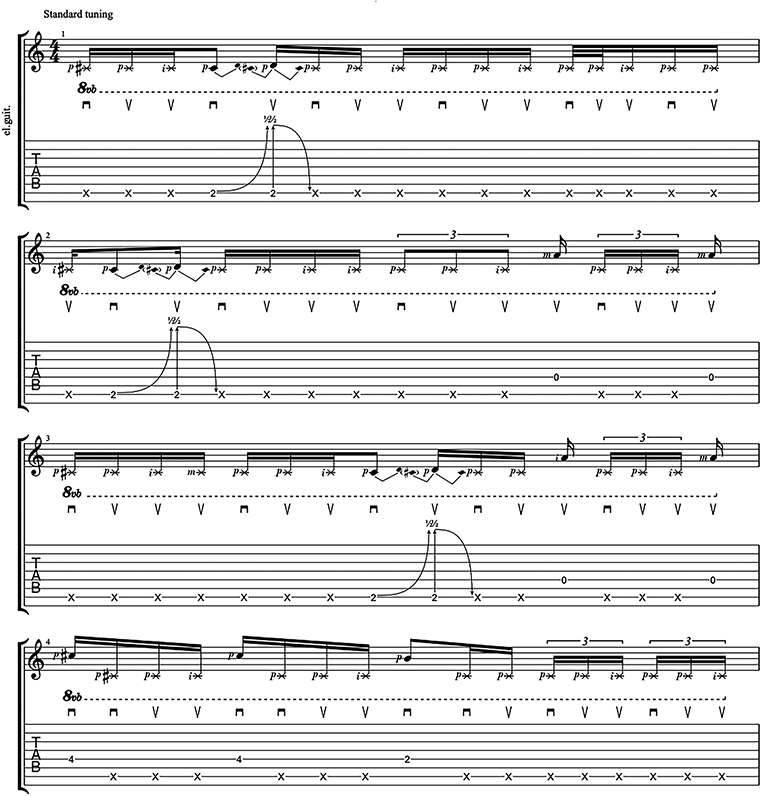

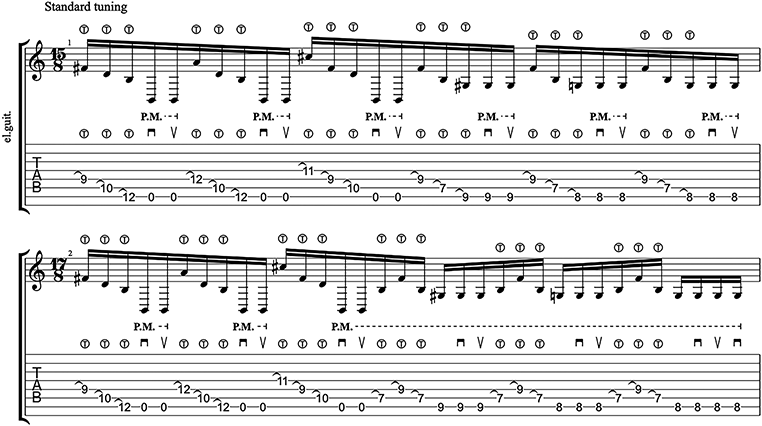

My own musical composition, A Floyd Chamber Concerto,54 commissioned by the Orchestre Régional de Normandie (France) and written in 2014, is a typical case of hybridization. The goal of this piece was to attempt to explain some of the big themes of the second half of the twentieth century, which are addressed in Pink Floyd’s songs. The work is thus presented as a succession of four movements referencing Pink Floyd’s music but played by a relatively reduced classical ensemble: one flute, one oboe, one clarinet, one bassoon, one French horn, three violins I, three violins II, two violas, two cellos, one double bass, and an electric guitar. The idea was to make this ensemble “sound” like a rock band and to rediscover, through the musical gesture, the energy of rock music: in other words, “soil” the sound, as I asked the string section to do for the beginning of the fourth movement. As the whole creative process was analyzed and presented at the IRCAM conference in January 2019,55 I will not go any further here. But let us take a moment to look at the guitar writing, which aims to “rediscover” certain characteristic features of the Gilmourian gesture, all the while keeping (at least, I hope) its own identity. The writing evokes Gilmour through the use of bends, paying more attention to sound rather than pure virtuosity, and a moderate use of distortion in a number of sequences. Even if the third movement owes more to Rick Wright (Sysyphus, 1969) than to Gilmour, the Floyd Chamber Concerto presents itself as an “intertextual” piece of work whose influences go beyond Floyd’s music alone: there are also traces of Maurice Ravel (beginning of the first movement), Philip Glass (at the end of the fourth movement), Stravinsky (at the beginning of the fourth and also in the second movement), etc. This intertextuality is, however, more linked to the sound (to the sonic texture, to the tone) than to the actual instrumental “technique.”

Conclusion

I am aware that this overview, focusing only on a few examples, deserves to be developed further. I have, for example, chosen to put aside the question of the legacy of the flamenco guitar in pop music, an aesthetic that dominates such obvious tracks as “Spanish Caravan” (The Doors, 1968), “A Spanish Piece” (Pink Floyd, 1969), “Spanish Fly” (Van Halen, 1979), and “Innuendo” (Queen, 1991), the “classical” and flamenco gestures sometimes intertwining.56 I have also left out the question of virtuosity with its classical links to jazz. My contribution shows that the twentieth century, while giving rise to the newly manufactured electric guitar and new popular genres of rock and its sub-categories (psychedelic, prog, metal, etc.), witnessed the integration of new sounds—the use of effects aiming to transform the tone of the instrument—to create a specific language and an instrumental gesture that freed itself from classical constraints, all the while paying homage to its musical ancestors. Conversely, the world of the “classical” guitar, despite some old school musicians’ hesitation (led by Segovia and Bobri), managed to integrate the technical progress born in the rock world and maybe even renew its own language and writing gestures through the use of its own equipment—the electric guitar.

If I cannot deny that a correct gesture is a prerequisite to any virtuosity (whatever its complexity), this contribution suggests that Segovia and Bobri are on the wrong track. By remaining stuck on techniques that concern only one type of repertoire, rejecting with force any progress linked to technology, they ignore a whole repertoire, including that intended for the “classical” guitar.

I have shown that the “classical” gesture is not the only way to achieve virtuosity. Rock musicians demonstrated that new gestures could be created and developed, helped by the possibilities offered by the guitar’s electrification, and that a new “technical” gesture can renew well-trodden forms of virtuosity.

Introduction

All modern bass guitars (also known as electric basses) can be traced back to the Fender Precision Bass.1 Released in 1951, the Precision Bass was intended to replace the acoustic upright basses that were then common in popular music. The instrument had been adapted from the design of the company’s Broadcaster electric guitar (soon to be renamed the Telecaster) and featured a large solid body, a long, fretted neck, and four thick strings. Most importantly, it utilized a pickup, which allowed the instrument to be electrically amplified. At the time of its release, this bass guitar hybrid was considered so strange and unconventional that, according to one salesman, retailers “who were not sure if Leo [Fender] was crazy when he brought out the solid-body guitar were darn sure he was crazy now … They were convinced that a person would have to be out of their mind to play that thing.”2 In the end, the Precision Bass overcame its reputation as a novelty instrument thanks to its many practical advantages: it was easier to transport, easier to play, and, through its amplification, it was far easier to hear in an ensemble context than a traditional upright. The bass guitar’s popularity subsequently spread across popular music as more and more musicians discovered these advantages. So great was its impact that, by the mid 1960s, not only did every major guitar manufacturer have their own version of a bass guitar but the instrument had also become a standard component of nearly every genre of Western popular music. In the decades since, the bass guitar has endured as popular music’s favorite low-end instrument.

The bass guitar’s history is inseparable from the history of the solid-body electric guitar. Both were often designed and built by the same instrument makers, produced at the same manufacturing facilities, and based around similar technological innovations, most notably amplification. For the electric guitar and bass guitar, the significant increase in volume that amplification provided made it possible for both to replace their acoustic predecessors. Despite their connections, however, each instrument ultimately came to serve distinct musical functions, with lead electric guitarists becoming featured soloists and bass guitarists relegated to background accompaniment.3 Most writers have not equally valued these two functions. The abiding trope of the “guitar god,” along with the overemphasis on rock styles in most early critical and scholarly analyses of popular music, has led to a robust literature on the electric guitar (to which this present volume also contributes). By contrast, the repetitive nature of most bass lines, their relative simplicity, and, most importantly, their supportive function in the music have all led critics, journalists, and academics to see the bass as less worthy of serious inquiry. Bassists’ musical contributions, therefore, have been regularly overlooked and underestimated, which, in turn, has meant that the bass’s role is far less commonly understood by average listeners.

This chapter and its accompanying playlist provide an overview of the ways that the bass guitar is most often used in popular music.4 Rather than discuss the instrument in terms of genre, I focus instead on its wider musical functions. As I argue, bass lines can largely be categorized by five common performative strategies: basic accompaniments, rhythmic- and groove-oriented approaches, melodic-oriented approaches, slap and pop styles, and the use of alternative instruments and techniques. While these strategies frequently overlap, this simplified taxonomy is intended to help listeners better appreciate how the bass shapes the overall sound and feel of a recording. By using a diverse cross-section of examples drawn from classic rock, metal, pop, R&B, soul, funk, reggae, disco, jazz, hip hop, and more, this chapter also highlights bass guitarists’ profound, wide-ranging impact on music history.

Bass-ic Accompaniments

The bass guitar is best thought of as a supporting instrument. Traditionally, bassists operate as part of the rhythm section, working in conjunction with drummers to construct the music’s rhythmic feel. Contrary to a drum kit, however, the bass guitar is also a pitched instrument. Tuned a full octave lower than a standard electric guitar, the bass occupies the “low end” of the frequency spectrum, and bassists therefore supply foundational low notes that establish or reinforce a song’s harmony, most often by playing the root notes of each chord.5 Furthermore, when an amplified bass guitar is played loudly in a live setting or reproduced via a decent speaker setup, the sound that it produces is felt within the body as much as it is heard by the ear. This is why the bass is usually a central component of dance musics: studies show that the tactile sensations produced by bass frequencies actively stimulate bodily movement.6 Taken together, these functions have made the bass indispensable for most popular styles. To better understand the bass’s importance, this section details some of the basic yet meaningful ways that the bass guitar is often used in popular music.

One approach that electric bassists frequently take is simply to “double” what the other musicians are playing, especially the electric guitarist. Most commonly, this takes the form of a “unison riff,” in which the bassist and guitarist play the same short, repeating musical phrase (although typically in different registers). For example, the intros to Black Sabbath’s “Paranoid” (1970) and Living Colour’s “Cult of Personality” (1988) each begin with the guitarist introducing a short, distorted riff, followed by the bassist joining in and duplicating the riff an octave lower. When the bass enters, those riffs are transformed into something dramatic and powerful, as when combined, the two instruments now more fully occupy the recording’s sonic space. This situation plays out in reverse in The Allman Brothers Band’s “Whipping Post” (1969), with the bass establishing the main riff first, followed by the guitarist joining in. In practice, unison riffs usually convey a sense of power, with the bass’s prominent low end adding to the “heaviness” that is valued in hard rock, punk, and metal.7

Because the bass plays a significant role in determining a song’s underlying rhythmic and harmonic structure, bass lines provide a supportive framework through which the other musical elements are understood. Take, for instance, Van Halen’s cover of The Kinks’ “You Really Got Me” (1978). The song is largely centered on an embellished unison riff played by bassist Michael Anthony and guitarist Eddie Van Halen. After the second chorus, Van Halen breaks away to play a highly technical solo that features rapid-fire passages, extended bends, “offbeat” phrasing, and his signature tapping, all while Anthony continues to play the riff underneath. Anthony’s role here is essential, as his steady rhythm and implied harmonic progression act as the foundation on top of which Van Halen builds his solo. In turn, the bass also becomes the lens through which we as listeners comprehend the solo’s expressivity, as Van Halen’s complex phrasing and note choices only make sense when heard against the stability of Anthony’s repeating bass line. In more extreme examples, the bass guitar is the only element that prevents a song from devolving into complete incoherence. Such is the case on Radiohead’s “The National Anthem” (2000), which is structured around a two-bar bass line, played by Thom Yorke, that continuously repeats while the rest of the music alternates between harsh dissonance and moments of relative calm. Beginning at approximately 2.50 minutes into the recording, the dissonance builds to a fever pitch with an extended free-jazz-inspired brass band section, which recedes temporarily before returning to ratchet up the tension yet again. Without the musical frame provided by Yorke’s bass line, the song would sound far more jumbled and chaotic.

None of the examples described thus far are particularly challenging to play. This demonstrates an important axiom about bass playing, which is that bass lines do not need to be complicated to be effective. Adele’s “Rolling in the Deep” (2010) is a case in point. The bass guitar enters at the pre-chorus, with producer Paul Epworth playing eighth notes on the roots of each chord. This is a simple, straightforward bass line, but one that simultaneously performs four key functions: it fills out the low end, it reinforces the harmonic progression, it emphasizes the insistent rhythmic feel, and most importantly, it contributes to the song’s building intensity. When the chorus finally hits, the bass complements Adele’s vocals as she soars into her higher register and then descends. In both sections, the bass adds energy to the song, which dissipates as soon as the bass drops out at the beginning of the subsequent verses. Simple bass lines can also serve as an anchor that unites a song’s otherwise disparate musical elements.8 For example, on the Pixies’ “Where is My Mind?” (1988), Kim Deal plays a basic, four-bar root-note bass line; slow, steady, and consistent, her bass provides a valuable sense of stability across the song’s exaggerated shifts in dynamics. As she explained to Bass Player magazine in 2004, “The bass in the Pixies is just glue; that’s all it is. It’s not supposed to be something else.”9

Bassists’ contributions may often be subtle, but they are nonetheless consequential. From filling out a recording’s sonic space to creating a framework for the musicians and listeners, or simply by anchoring the rest of the band, even the humblest bass lines can have a significant effect on how we hear and make sense of the music. As I detail in the rest of this chapter, these effects are further magnified when bassists go beyond the basics.

Rhythmic- and Groove-Oriented Approaches

One way that bass guitarists can take on a more prominent position in the music is by leaning into specific aspects of the bass’s established functions. By far the most common strategy is to expand the bass’s rhythmic role. Although the implementation of this strategy can vary widely depending on style and genre, its function is to take a more active part in shaping the overall feel of the music. In hard rock, metal, and punk, for instance, the bass is regularly used to provide a sense of forward motion. On Suzi Quatro’s “Can the Can” (1973), Quatro’s galloping bass line gives the song a rhythmic punch that pushes the song forward. As she explained to an interviewer in 2019, “The bass and drums are the engine that drives the song; nothing is more important.”10 Doubling down on this approach, Lemmy Kilmister adds a similar drive to Motörhead’s “Ace of Spades” (1980), conveying a sense of power and momentum through his incredibly fast rhythmic playing and his distorted bass timbre.11

While some bass guitarists use their instruments to rhythmically propel the music, others choose instead to emphasize cyclic grooves. These sorts of groove-oriented bass lines are especially common in dance musics, which often derive pleasure from the layering of repetitive, interlocking rhythms. Take Michael Jackson’s “Billie Jean” (1982), which begins with a drum pattern that establishes the song’s steady pulse, followed by bassist Louis Johnson adding the song’s repetitive, hypnotic bass line. Together, these two elements create a fluid, rhythmic feel, with Johnson’s cyclic bass line weaving around the drum’s kick-snare pattern. At various points in the recording, synths, Jackson’s vocals, and electric guitars are all layered into the mix, but the overall arrangement is sparse, and the bass is the only element that consistently supplies the groove.

Many groove-oriented bass lines are thus constructed around riffs, with the bassist playing a short musical phrase that they repeat (or loosely vary) throughout a song. Unlike the unison riffs described in the previous section, groove-oriented bass guitar riffs are usually played solely by the bassist and tend to operate in the background of the music. Their purpose is to accentuate the rhythm by working with and against the other musical elements. This approach was first popularized by bass guitarists operating in 1960s African American styles, such as R&B and soul. A classic example is Wilson Pickett’s “In the Midnight Hour” (1965), featuring Donald “Duck” Dunn on bass guitar. For most of the song, Dunn plays an ascending bass riff that he repeats over and over again, creating a distinctive push-and-pull groove by locking in with the drummer’s snare hits on the second and fourth beats of each bar. As in the Michael Jackson example, the bass riff works both as a standalone layer in the music and as part of an interlocking rhythm section.

Likewise, although the feel of the music is quite different, reggae musicians often employ a similar formula, combining a bass riff with a simple drumbeat (collectively known, following Jamaican Patois, as the “riddim”) to create a foundation for the rest of the music. This structure can be heard on Sound Dimension’s “Full Up” (1968), which features a classic riddim bass line played by bass guitarist Leroy Sibbles. Although Sibbles’ bass is a bit buried in the overall mix, it still contributes to the song’s laid-back feel. However, since riddim lines are regularly repurposed and reused, Sibbles’ original bass line has lived on in later adaptations, including Musical Youth’s “Pass the Dutchie” (1982).

Some bass guitar riffs, in fact, are so memorable that they become the defining feature of a song. Among the many examples that fall within this category are Roger Waters’ bass line to Pink Floyd’s “Money” (1973), Tina Weymouth’s bass line to Talking Heads’ “Psycho Killer” (1977), Rick James’ bass line to “Super Freak” (1981), John Deacon’s bass line to Queen and David Bowie’s “Under Pressure” (1981), Kathy Valentine’s bass line to The Go-Go’s’ “We Got the Beat” (1982), Mike Dirnt’s bass line to Green Day’s “Longview” (1994), and Chris Wolstenholme’s bass line to Muse’s “Hysteria” (2003).

In addition to using repetitive riffs, bass guitarists also often use syncopation to emphasize their rhythmic role. Rather than only stressing the music’s regular, strong beats, syncopated bass lines accent weak beats (or offbeats). In so doing, they create small-scale rhythmic tensions that can add a distinctive feel to the music. Perhaps the clearest illustration of this technique comes from the verses of King Floyd’s “Groove Me” (1970), on which bassist Vernie Robbins plays a slow, repeating two-bar riff. From a pitch perspective, this bass line is fairly uninteresting, as Robbins simply performs an ascending major pentatonic scale. What makes it stand out, however, is its syncopation: after emphasizing the first strong beat (the “downbeat”) of the phrase, every one of his subsequent accents falls on offbeats. When heard against the backdrop of the steady, regularly accented drum pattern, Robbins’ alternation between rhythmic stability and instability creates the song’s titular groove. This approach is characteristic of funk music, especially as developed by James Brown in the mid 1960s and early 1970s. On Brown’s “Super Bad” (1970), for example, bassist Bootsy Collins follows that same formula—shaping the groove by playing two-bar, push-and-pull bass lines that emphasize the downbeat of the first bar followed by offbeat accents that add rhythmic tension. Drawing inspiration from early funk, disco bassists extended this approach, which was further accentuated by their increased prominence in the overall mix. This style is best represented by Bernard Edwards’ catchy riff on Chic’s “Good Times” (1979), which uses a syncopated, push-and-pull effect to give the song its signature danceability.

More recently, neo-soul bassists such as Meshell Ndegeocello have developed more restrained groove-oriented styles based around meticulous conceptions of space and syncopation. As she explained to musicologist Tammy L. Kernodle:

My thing is I feel time … I want to be able to put any note where I hear it in that time configuration. And that’s usually how I think of bass lines. I can play them right on the chord, right where it goes. But, there’s incremental beats in between those that I have a natural attraction to. So I try and find those as well.12

One of the best examples of Ndegeocello’s bass style is her “Make Me Wanna Holler” (1996), which features a slow, hypnotic groove, precise timing, a clear emphasis on empty space, and intermittent improvised fills.

Some bass guitarists use their speed, technical facility, and internalized sense of rhythm to construct even more complex grooves. One example is session musician Chuck Rainey, who was known for his sophisticated approach to rhythm. When given complete freedom to improvise on a session, Rainey would often craft intricately subdivided bass lines. On Aretha Franklin’s “Every Natural Thing” (1974), for instance, he begins with a propulsive, syncopated bass riff that he varies constantly; at the chorus, he explodes, building the song’s rhythmic energy through a blistering flurry of syncopated sixteenth notes. By contrast, on Steely Dan’s “Kid Charlemagne” (1976), Rainey plays an intricate bass line that is also constructed around syncopated sixteenth notes; here, however, his approach differs as his free-flowing playing anchors the song and gives it a consistent sense of groove despite its challenging arrangement. Succinctly summarizing his style, Rainey explained to me that: “A lot of people think that I play a lot of notes, but I don’t. I play a lot of rhythm on the few notes I do play.”13 For styles of rock that value complexity and virtuosity—most notably progressive rock and some forms of metal—bass guitarists frequently use complex grooves to demonstrate their technical mastery. Geddy Lee’s bass playing on Rush’s “YYZ” (1981), for example, alternates between intricate unison riffs and elaborate solo passages, showcasing both his and the entire band’s virtuosity. Modern jazz musicians have similarly been drawn to complex grooves, both for their added challenge and for the creative possibilities they offer. For example, on bassist Esperanza Spalding’s “I Know You Know” (2008), she spends the first minute and a half deliberately not accenting the downbeat, crafting a complex, stop-start syncopated bass groove that complements her vocals; for the bridge and solo sections, she introduces accented downbeats that radically change the feel of the groove, before ultimately returning to her original approach. Taken as a whole, Spalding’s bass playing demonstrates her immense skill and serves as a vehicle for her personal expression.

Melodic-Oriented Approaches

Another way that bassists have expanded their role is to play melodically. In this style, which emphasizes the bass’s function as a pitched instrument, bassists draw on a wider palette of potential note choices to deliberately craft extended, connected musical phrases. By transforming the bass into a featured melodic layer in the music, this approach breaks with traditional conceptions of the bass as merely a background or supportive instrument. It is therefore far less common than rhythmic- or groove-oriented approaches (which remain the norm) but is understandably prized by bassists that wish to take on a more prominent musical role.

While there are multiple styles of melodic bass playing, key characteristics unite the approach. For instance, bassists who adopt a melodic approach often eschew the bass’s usual timekeeping function (i.e. reinforcing the pulse of the music) and hence are free to leave more space in their playing and/or vary their rhythmic activity to serve their musical phrase. Similarly, melodic players often emphasize the bass’s middle and higher registers, an approach that is facilitated by the instrument’s frets, which allow the musician to find notes quickly and accurately at any position on the neck. They also commonly employ various types of articulations—slides, hammer-ons and pull-offs, leaps, etc.—that mimic the inflections of the human voice.14 Most melodic bass lines thus have a distinctive, singable quality that draws the listener’s attention. Session bassist Carol Kaye’s performance on Barbra Streisand’s 1973 ballad “The Way We Were” serves as a good example. Kaye builds her melodic bass line slowly over the course of the song, complementing Streisand’s dramatic vocal performance. Moving up and down the neck, Kaye constructs a free-flowing line that incorporates slides, rhythmic variation, leaps, and more—all of which serve to heighten the song’s sense of wistful melancholy.

Melodic bass lines are most often introduced at the beginning of a song, acting as an opening hook that stands apart from the rhythm section. The bassist then usually maintains a foregrounded role throughout the rest of the song. For example, Led Zeppelin’s “Ramble On” (1969) starts softly with muted drumming and a strummed chordal lick on acoustic guitar; but ten seconds in, bassist John Paul Jones enters with a four-bar melodic bass line that is prominently situated in the mix. Operating in the bass’s higher register, Jones uses leaps, slides, and smooth phrasing as he weaves around the drums and guitar. As Jones repeats his melody, the vocals enter, but the bass does not recede into the background. Instead, it maintains its featured position, even as Jones switches to a more insistent, rhythmic style in the choruses.15 An even more conspicuous melodic approach can be heard in Prince’s “Diamonds and Pearls” (1991), which opens with Sonny T. playing a four-bar melodic bass line that moves sinuously between the bass’s higher, middle, and lower registers. As is ultimately revealed, this bass melody is also the main vocal melody of the verse, which Prince sings in a higher octave. This bass-voice relationship continues into the choruses, with Sonny T. and Prince doubling the chorus melody as well.

Another common approach is to use the bass to supply a countermelody that is meant to be understood through its interaction with a song’s other melodic elements. On the Beatles’ “Something” (1969), for instance, Paul McCartney plays in the bass’s middle and higher register, incorporating slides, leaps, hammer-ons, contrasting fast and slow passages, grace notes, and more. His melodic bass playing functions as a counterpoint to George Harrison’s voice, working in a style of call-and-response that fills out the space of the otherwise slow, understated recording. One of the clearest examples of this countermelodic approach comes from the opening of Guns N’ Roses’ “Sweet Child O’ Mine” (1987), in which bassist Duff McKagan adds a distinctive, singable bass line underneath Slash’s famous, string-skipping opening electric guitar riff. Notably, both McKagan and Slash are placed at a relatively equal volume in the mix, and the listener is invited to concentrate on either part individually, or to experience them as an intertwined whole.

As is probably clear from the descriptions thus far, melodic-oriented and rhythmic-oriented approaches are not mutually exclusive. Many melodic bassists will switch to a more rhythmic-oriented approach at key moments in a song (such as the chorus) to add a sense of energy or stability. Furthermore, bass riffs are, in some ways, inherently melodic, even if their predominant function is to emphasize the rhythm or groove. Other bassists straddle the line between the two by adding some melodic flourishes to cyclic bass lines, creating what I call “melodic bass grooves.” As with much groove playing, in popular music, melodic bass grooves are primarily associated with African American dance music traditions. Perhaps the most famous melodic bass groove comes from The Jackson 5’s “I Want You Back” (1969), featuring bassist Wilton Felder. In the intro and verses, Felder plays a bass hook that fluidly navigates the chord progression; in the choruses, he plays a contrasting bass line, adding in more rhythmic variety and embellishments. Both are foregrounded in the mix, acting as melodic layers in the music while also contributing to its overall groove.16 Jimmie Williams’ bass line to McFadden and Whitehead’s “Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us Now” (1979) has a comparable function. Starting at approximately 17 seconds into the recording, Williams introduces the distinctive two-bar bass riff that he will play throughout nearly the entire song. Yet, in contrast to some of the riffs discussed previously, Williams incorporates melodic phrasing—leaps, ghost notes, and slides—that give the line a singable quality; at the same time, its steady pulse, syncopated rhythms, and constant repetition emphasize the song’s disco groove.

Some bassists have cultivated even more complex melodic styles by adopting a more soloistic approach. This approach was first popularized by session bassist James Jamerson, who played on hundreds of Motown hits in the 1960s and early 1970s, including music by Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, The Temptations, The Supremes, The Four Tops, Martha and the Vandellas, and many more. Drawing on his background as a jazz musician, Jamerson developed an adventurous, highly influential style of pop bass playing. Here is how he described a typical session:

When they gave me that chord sheet, I’d look at it, but then start doing what I felt and what I thought would fit … I’d hear the melody line from the lyrics and I’d build the bass line around that. I always tried to support the melody. I had to. I’d make it repetitious, but also add things to it … It was repetitious but had to be funky and have emotion.17

Jamerson’s style is on full display on Stevie Wonder’s “For Once in My Life” (1968) and Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” (1971), as he improvises nuanced, constantly varying melodic bass lines that intricately weave around each singer’s voice. A more recent version of this approach can be heard on TLC’s “Waterfalls” (1995), which features a similarly intricate melodic bass line improvised by LaMarquis “ReMarqable” Jefferson. In rock contexts, bassists that adopt elaborate melodic approaches often simply take over the role conventionally reserved for the electric guitar. On The Who’s “The Real Me” (1973), for example, bassist John Entwistle plays an extended, improvised solo throughout the entire song. Likewise, through her work with Jeff Beck and others, bassist Tal Wilkenfeld has become known for her nuanced, melodic soloing.

Slap and Pop Styles

Thus far, I have described broad conceptual categories centered on the bass’s musical function. However, it is also worth briefly discussing the ways that bassists physically play their instruments, as that too has a significant impact on their sound.18 Broadly speaking, bass guitarists either play with their index and middle fingers, with their thumbs, or with a pick.19 Many will even switch between these techniques, selecting the one most appropriate for a given song. But, of all the different ways of playing the bass, one is so distinctive and identifiable that it warrants a special explanation: slap and pop. The style is named for the way that bassists strike the strings, usually by hitting the lower strings with the side of their thumb (“slapping”) and then using their other fingers to pluck the higher strings away from the instrument (“popping”). This technique gives the bass a percussive thump that makes it stand out in the music, and though there are different approaches to slap bass, they all center around this basic effect. For example, on Ida Nielsen’s “Throwback” (2016), Nielsen plays in a typical slap and pop bass style, using her thumb to play the funky, sliding bass riff and her other fingers to provide additional accents. As with most slap bass lines, Nielsen’s functions as a melodic bass groove, strongly emphasizing the rhythm while also serving as a standalone melodic layer in the music.

For bass guitarists, the slap and pop style was first popularized in the late 1960s by Larry Graham of Sly and the Family Stone, who employed it, most famously, on their 1969 hit “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin).” Expanding on Graham’s model, funk bassists made slap bass a regular feature of later African American musical styles, as exemplified by the bass lines to Cheryl Lynn’s “Got to Be Real” (1978) and Patrice Rushen’s “Forget Me Nots” (1982). By the 1980s, the style had also been adopted by rock bassists operating in both new wave and funk metal styles, such as Mark King from Level 42 and Flea from the Red Hot Chili Peppers. In the 1990s and 2000s, slap and pop bass lines were also incorporated into some styles of hip hop, either through sampling—such as the Notorious B.I.G.’s “Hypnotize” (1997), which samples Abe Laboriel’s slap playing on Herb Alpert’s “Rise” (1979)—or through newly recorded performances—such as Aaron Mills’ slap line on Outkast’s “Ms. Jackson” (2000).

Notably, jazz fusion bassists continue to adopt and expand the slap bass style. One of the first was bassist Stanley Clarke, who used it, for example, on the intro to “Lopsy Lu” (1974). Marcus Miller subsequently built on this approach, drawing on slap and pop techniques to construct complex bass lines that combine melodic grooves, fast rhythmic passages, singable melodies, and extended soloing (all of which can be heard on the track “Power” from his 2001 album M2). Furthermore, bassists such as Victor Wooten have used slap techniques to develop intricate “one-man band” performance styles, playing multiple interlocking parts on a single bass guitar (see “U Can’t Hold No Groove” from his 1996 album A Show of Hands).

Alternative Instruments and Techniques

As we have seen, many bass guitarists have sought to expand their instrument’s basic role in popular music. In addition to the bassists previously discussed in this chapter, a select few have moved beyond the bass’s traditional confines by embracing new technologies and performance practices. In so doing, these musicians have developed notable, albeit atypical, approaches to bass playing.

One significant innovation was the development of the fretless bass guitar. Like their upright bass counterparts, fretless basses enable smooth slide playing, which musicians often use to give their bass lines an added expressivity. The first notable fretless bass player was Bill Wyman of The Rolling Stones, who played the instrument on many of the band’s hits up through 1975. In the mid 1970s, the fretless became associated with jazz fusion bassist Jaco Pastorius. Thanks to his recorded and live performances with Weather Report, his first solo album, and his collaborations with Joni Mitchell, Pastorius continues to be regarded as one of the best bass guitarists of all time—a designation that stems both from his astounding technical abilities and the unique timbre he elicited from his fretless bass (both of which can be heard on his 1976 rendition of “Donna Lee”). Beginning in the early 1980s, session bassist Pino Palladino further introduced mainstream pop audiences to the sound of the fretless bass through recordings such as Paul Young’s version of “Wherever I Lay My Hat (That’s My Home)” (1983). Other notable fretless bassists include Japan’s Mick Karn, Bakithi Kumalo, who played on Paul Simon’s Graceland (1986), and Pearl Jam’s Jeff Ament, who played a fretless on most tracks from his band’s debut album, Ten (1991).

Other alternative bass techniques evolved directly out of prior innovations in electric guitar performance. The most famous of these is the use of two-handed tapping. Rather than following the traditional method of using one hand to fret a note and the other to strike the string, in two-handed tapping, the musician utilizes both hands on the fretboard, using hammer-ons and pull-offs to play rapid, expansive passages. Popularized by Van Halen in the late 1970s, this technique eventually became widespread among heavy metal guitarists, after which it was also adopted by some bassists. One of the first bass guitarists to explore the expressive possibilities of two-handed tapping was Stuart Hamm. Through his work with guitarists Steve Vai and Joe Satriani, as well as his solo material, Hamm developed a complex style that employed tapping as a compositional device, using it to craft intricate, interlocking musical phrases (see, for example, his entirely tapped bass line on “Terminal Beach,” from his 1989 album Kings of Sleep). Other bassists that regularly incorporate two-handed bass tapping include Billy Sheehan of Talas and Mr. Big, and Les Claypool of Primus.

Several musicians have also adopted instruments that extend beyond the traditional bass guitar’s limited range. Five-string basses, which add an additional lower string to the instrument, are the most commonly used extended-range bass guitars today. By most accounts, the first bass to feature a lower-fifth-string design was an Alembic custom built for jazz bassist Jimmy Johnson in the mid 1970s. This design became more widely available in 1984 with the commercial release of the Yamaha BB5000. Session bassist Nathan East was an early adopter of the BB5000 and used it to great effect while working with Al Jarreau and Philip Bailey, among many others. Five-string basses are especially prevalent in contemporary styles of heavy metal, which (in conjunction with electric guitarists’ own use of detuned or extended-range instruments) tend to emphasize the lower frequency spectrum. A handful of bassists have also come to specialize in playing six-string basses, which have both an additional lower and higher string.20 Pioneered in the 1980s by R&B/jazz session bassist Anthony Jackson, the six-string style allows the musician to explore a much wider selection of note choices, playing registers, and phrasing options (Jackson’s virtuosic six-string style is best captured on his multiple recorded collaborations with pianist Michel Camilo, such as 1994’s “Not Yet”). Although the six-string bass remains a niche instrument, it continues to be used by bassists across musical genres, including John Myung of the progressive metal band Dream Theater, ambient/improvisational bassist Steve Lawson, and funk/fusion/contemporary R&B/hip hop bassist Thundercat.21

Conclusion: The Bass Guitar Today

The bass guitar is still commonly used within many types of modern popular music, especially those descended from twentieth-century styles—such as rock, punk, metal, funk, R&B, and jazz fusion. In addition to those already mentioned, other notable contemporary bass guitarists include Este Haim of Haim, Justin Chancellor of Tool, MonoNeon, Joe Dart of Vulfpeck, Jamareo Artis of Bruno Mars’ Hooligans, Michael League of Snarky Puppy, Derrick Hodge, and Mohini Dey. However, like the electric guitar, the bass guitar’s overall popularity has waned somewhat over the last twenty years. Thanks to the widespread availability of computer-based music recording software and the influence of electronic dance music production practices, many pop bass lines are now created digitally instead of using a musician-bass guitar-amplifier setup. For many contemporary artists, songwriters, and producers, this process is simply easier and more cost-efficient. This technology is also so advanced that it can convincingly reproduce the sound of a bass guitar. For example, although Dua Lipa’s “Don’t Start Now” (2020) distinctly references 1970s disco, its bass line was programmed digitally. Yet rather than demonstrating the bass guitar’s obsolescence or irrelevance, in many ways, these efforts actually reveal how ingrained the instrument’s associated sounds and functions are within popular music: they remain indispensable, even when the instrument itself is no longer present.22

Bass guitarists, using the various performative strategies described in this chapter, have profoundly shaped popular music for more than sixty years, and it is important that we take their contributions seriously. Such recognition simply requires that scholars, critics, and fans more equitably value popular music’s supportive and soloistic elements—a reappraisal that seems long overdue.

Introduction

The virtuosic electric guitar movement is a topic most associated with prominent players of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, such as Jimi Hendrix, Jeff Beck, Eddie Van Halen, Yngwie Malmsteen, and Tony MacAlpine.1 Throughout their careers, these players pushed the technical and creative boundaries of the instrument, placing them at the center of the guitar studies literature that highlights their originality and influential legacy in electric guitar technique, equipment, and culture.2 In comparison, the contemporary movement—defined in this chapter as a network of artists conversing primarily online on Instagram and YouTube—has received far less scholarly attention despite continuing to push boundaries and explore new approaches to the instrument, its sound, and how and where guitar culture takes place. Guitarists such as Tosin Abasi of progressive metal band Animals as Leaders, Tim Henson of Polyphia, and Yvette Young of Covet are pioneers in the contemporary guitar movement with innovative techniques and approaches to the instrument. Just like their influential virtuosic predecessors, these newer-generation guitarists primarily make instrumental music, using their technical abilities equally harmonically, rhythmically, and melodically for the benefit of musical composition and displaying their virtuosity.

The main space where contemporary electric guitarists “meet” is Instagram and, by extension, YouTube (see also Daniel Lee’s Chapter 15 on online guitar communities). On these platforms, guitarists post videos of themselves playing short snippets of work-in-progress material to receive feedback, update their followers, or merely create content. Popular videos showcase juxtaposed techniques such as tapping, thumping, and natural harmonics in close succession and with challenging combinations, as seen in videos by Ichika Nito,3 one of the guitarists with the largest following on Instagram (750,000 followers) and YouTube (2.2 million followers)—considerably outnumbering established virtuosos such as Steve Vai, Joe Satriani, or John Petrucci. Short educational videos on technique and music theory are also popular. Instagram is a place where guitarists also network and initiate collaborations such as joint albums, tours, or cover versions.

The clips receiving the most attention have high-quality video and audio recordings, usually edited, mixed, and mastered by the performer. Next to the high-quality videos, the playing must, in most cases, display a certain degree of virtuosity to attract attention. Importantly, though, the fans consider artists popular in the scene to be not only virtuosic but also accomplished composers and producers.4 This more balanced relationship between technical and musical skills makes perhaps the difference to some earlier virtuosic movements in electric guitar history. Arguably, the Shrapnel “shred guitar” era in the 1980s (e.g. Yngwie Malmsteen, Paul Gilbert, Vinnie Moore, Tony MacAlpine, Jason Becker, Greg Howe, Richie Kotzen) focused more on the display of technical prowess than on the quality of musical compositions—in contrast to the first generation of rock guitar virtuosos in the 1960s and 1970s (including Jimi Hendrix, Jeff Beck, Ritchie Blackmore, Uli Jon Roth, Randy Rhoads, Eddie Van Halen, Frank Zappa), who were valued as much for their songwriting as for their technical capabilities. We argue that while contemporary players certainly flaunt their virtuoso skills, just as previous generations of virtuosos did, their technique tends to be employed to benefit the quality of the songs (some of which do not contain traditional solos), whereas the songs of the earlier “shred” era were sometimes mere placeholders for technically demanding solos in which there was a stark contrast between highly advanced soloing and comparatively simple rhythm playing.5

Lively exchange on social media afforded by the internet has generally become a trend in popular music.6 Instagram provides contemporary guitarists with an essential marketing tool, which most of them use to personalize their social platform for their fans by posting pictures of their partners and holidays. The platform creates seemingly personal relationships, as followers can ask questions about Instagram stories. By engaging with their fans, leading to imaginative bonding facilitated by social media, these musicians are breaking away from the aloof rock guitar hero of the past.7 Most followers are musicians themselves, in particular, guitarists. They fulfill a crucial role in the economic viability and success of artists they respect, who earn most of their professional income from streaming royalties and the sale of educational products or online lessons rather than traditional revenue streams such as concerts, merchandise, and record sales.8 Many of the figurehead guitarists on Instagram, such as Jack Gardiner and Matteo Mancuso, post videos of themselves playing their own music and improvisations to promote their educational products, such as downloadable video lessons and masterclasses, on services like Jam Track Central.

This chapter outlines advances in guitar playing techniques commonly practiced in the contemporary scene defined above. Some of the techniques presented have been developed specifically for the guitar or were adopted from other instruments such as the violin, piano, bass, and drums to facilitate compositional ideas. Less attention is given in this chapter to the gear used by contemporary players and how their choice of equipment helps them achieve novelty in electric guitar-centered music. By discussing several playing techniques, this chapter provides an overview of techniques rather than an in-depth analysis of a specific technique.

There are numerous artists worthy of discussion, but this chapter concentrates primarily on guitarists in the progressive rock and metal genres, as these are the dominant styles in the contemporary guitar scenes analyzed,9 and they are also genres in which virtuosic technique has historically been foregrounded. A peculiarity to be mentioned is that many guitarists and their work explored have prominent influences and compositional styles beyond rock music. The blending of genres is commonplace and may itself be understood as a mark of virtuosity that is perhaps less technical in nature but reflects the musicians’ intention to explore expressively and artistically in the spirit of progressive (rock) music. Some influential musicians such as Tosin Abasi refer to themselves only as “progressive,” arguing that the terms prog rock and metal fail to capture the genre-bending nature of the current scene, the inclusion of electronic sounds, and the aesthetics of computer-produced music.10 For Abasi, progressive is a “fundamental approach” that does not have to adhere to the conventions of established genres with specific traditions like prog rock. Other examples of progressive artists include Polyphia, one of the main artists discussed below, who use structural and production influences from Kanye West to Taylor Swift throughout their album New Levels New Devils (2018), evident in tracks such as “O.D.” (2018). Manuel Gardner-Fernandes of Unprocessed creates pop-oriented music with skillful guitar playing and vocals with catchy hooks, as heard in their track “Deadrose” (2020). Intervals draw particular stylistic inspiration from pop-punk influences that run throughout their discography from the album The Shape of Colour (2015) onward.

Sweep Picking

Sweep picking (also known as “sweeping”) is a technique that has been used throughout the history of the electric guitar, particularly since the 1970s. As a technique of performing notes on successive strings with a single downward or upward motion, sweeping has undergone various changes regarding mechanical approaches and compositional purposes. Notable guitarists such as Jason Becker, Tony MacAlpine, and Rusty Cooley have employed sweep picking extensively throughout their careers, mainly as a display of virtuosity.11 Nowadays, sweep picking has lost much of its impressive impact, as it has become a standard technique learned by most ambitious rock and metal electric guitarists within their first few years as players.