Introduction

In a fiery 1956 sermon captured on grainy, black-and-white film, Reverend Jimmie Snow explains to his Nashville congregation why he preaches against rock and roll. ‘I know how it feels’, he intones, ‘I know the evil feeling that you feel when you sing it. I know the lost position that you get into in the beat. Well, if you talk to the average teenager of today and you ask them what it is about rock-and-roll music that they like, the first thing they’ll say is the beat, the beat, the beat!’1 Like many social leaders who condemned rock and roll, Snow located the allure and impact of this music, commonly called ‘beat music’ or simply the ‘big beat’, in its powerful percussive accompaniment. The central and most distinctive feature of the rock-and-roll beat was its emphatic, relentless snare drum accents on ‘two and four’, the conventionally ‘weak’ beats of the measure – the so-called backbeat. Shocking though it was to many in the 1950s, the backbeat soon became and remains one of the single most prevalent features of Western popular music. This chapter explores the origins of the backbeat, charts its early history on record from the 1920s to the 1950s, and considers how it has functioned as a meaningful musical signifier and cultural agent.

For the purposes of this chapter I limit my discussion to backbeats that are exclusively rhythmic in nature, serving no harmonic or other musical function. Thus, neither the weak-beat piano, banjo, or guitar chords common in nineteenth-century songs and dance music, ragtime, early jazz, country, and blues, nor the slap-back bass in swing, Western swing, and rockabilly will be considered. Rather, I focus on the emergence of the backbeat as a convention in drum kit performance practice, typically played on the snare drum. The distinctive, piercing ‘crack’ (or ‘whack’, ‘slap’, ‘spank’, etc.) of the snare drum and its potential for extreme volumes make the drum kit backbeat different in kind from the off-beat piano, banjo, guitar, or bass rhythms cited above.

Backbeating As Signifyin(g) Practice

Reverend Snow was among many who linked the rock-and-roll backbeat to juvenile delinquency and violence. Justifying the ban on rock-and-roll shows in Jersey City in 1956, Mayor B. J. Berry asserted ‘this rock-and-roll rhythm is filled with dynamite, and we don’t want the dynamite to go off in Roosevelt Stadium’.2 Critics also blamed rock and roll for promoting lascivious dancing and sexual promiscuity, claiming that its beat replicated the rhythms of sex. Condemnations of beat music commonly resorted to racist language associating the ‘primitive’ rock-and-roll beat with the ‘savage’ instincts of ‘inferior’ races. Few were more forthright than Asa Carter of the White Citizens Council of Alabama, who asserted ‘rock-and-roll music is the basic, heavy-beat music of the Negroes. It appeals to the base in man, brings out animalism and vulgarity’.3 As Steven F. Lawson summarizes, ‘the language used to link rock with the behaviour of antisocial youths was couched in … racial stereotypes. Music Journal asserted that the “jungle rhythms” of rock incited juvenile offenders into “orgies of sex and violence” … The New York Daily News derided the obscene lyrics set to “primitive jungle-beat rhythms”’.4 As late as 1987, conservative critics could assert that rock’s ‘notorious’, ‘evil’ backbeat ‘is very dangerous since it owes its beginnings to African demon worship’.5

Kofi Agawu has deconstructed the myth of ‘African rhythm’ – the notion that ‘blacks … exhibit an essential irreducible rhythmic disposition’ – exposing it as a white invention often deployed in the justification of racial hierarchy.6 As Ronald Radano notes, ‘the primitivist orthodoxy of “natural rhythm”’ can also serve as ‘a means of affirming positive identities in an egregiously racist, nationalist environment’.7 For instance, as Isaac Hayes recalled, ‘it was the standard joke with blacks, that whites could not, cannot clap on a backbeat. You know—ain’t got the rhythm’.8 Similarly, blues musician Taj Mahal interrupted a 1993 performance to chide his German audience for clapping on the downbeat. ‘Wait, wait, wait … This is schwarze [black] musick’, he instructs the crowd. ‘Zwie, vier! One, TWO, three, FOUR!’9

The affirmative potential of such strategic essentialism notwithstanding, reducing the backbeat to an inbred racial trait is profoundly limiting and, like all essentialisms, has dangerous ramifications. This is borne out by the fierce backlash against rock and roll, ‘the heavy-beat music of the Negroes’, part of a larger racist backlash in the age of Brown vs. the Board of Education, the Little Rock Nine, and Emmett Till. Far from being an inbred musical predisposition of black people, the backbeat emerged as a strategic cultural response to specific social, historical, and musical conditions. Understanding this history requires that we consider the practice of backbeating before the development of the drum kit during the first decades of the twentieth century. Indeed, as all drummers know, one does not need a drum kit to perform the multi-limb rhythmic beating that is the essence of drum kit performance practice.

Samuel Floyd has traced various elements common in African-American music – including call-and-response patterns, pitch-bending, and unflagging off-beat rhythms – to the ring shout, a ritual adapted from West African sacred traditions.10 Participants sing and chant over the rhythms of their shuffling feet, hand claps, and other body percussion. As Floyd explains, the ring shout also exemplifies the practice of ‘signifyin(g)’ central to West African and African-American expressive culture, as participants extemporaneously expand on traditional texts with additional verses, embellishments, commentary, and so forth. Theorized by Henry Louis Gates, Jr, signifyin(g) involves the interpretive elaboration on received ideas, narratives, texts, etc., often as a means of resisting or inverting dominant ideologies and power relationships, and it underlies much African-American vernacular culture, from ragging tunes to rap battles.11 As a signifyin(g) practice, backbeating is a means of responding to and reinterpreting the conventional ‘strong’ downbeat of Western music – of simultaneously acknowledging and resisting it, of playing with and working against it, of inverting it, enhancing it, and making it groove.

Incarceration, Hard Labour, and the Backbeat

In ways both metaphorical and real, backbeating has functioned as a meaningful response by African Americans to the brutal oppression of slavery and the long, violent aftermath of the Civil War. For many black southerners, conditions scarcely changed after abolition. Laws targeting black people fed a network of prisons that effectively replicated the conditions of slavery. Trivial offences or bogus charges could land black citizens in labour camps such as the notorious Angola State Penitentiary in Louisiana, Parchman Farm in Mississippi, or the Darrington State Prison Farm in Texas. Each are known for their brutal conditions, but also for field recordings conducted by John and Alan Lomax beginning in 1933.

These recordings establish African-American prison songs as one of earliest repertories on record that commonly features emphatic backbeat accompaniments. For example, ‘Long John’ (1933), sung by a group of prisoners led by ‘Lightning’ Washington, is based on a story from antebellum black folklore. Representative of the trickster hero central to many signifyin(g) texts, Long John is a fugitive slave who leads a nationwide chase, outwitting his would-be captors at every turn. Washington lines out the tale, lacing it with Biblical references, and the group repeats each line to the accompaniment of axes striking on the backbeat.12 As is common in trickster tales, Long John uses cunning and wit to subvert established power structures, just as the backbeat subverts conventional notions concerning ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ beats.

In their percussive accompaniments, these prisoners transform the tools of their oppression into musical instruments, making them potential tools of liberation. By signifyin(g) on the downbeat, the prisoners transform the rhythms of forced labour into compelling grooves, creating the possibility of experiencing the body, not only as a site of violent oppression, but also as a potential site of creativity and pleasure. Here backbeating constitutes a strategy for survival and resistance, providing historical precedent for John Mowitt’s assertion that the rock-and-roll backbeat ‘define[d] the substance of a modest, but tenacious pedagogy of the oppressed … a practical wisdom about how to “strike back” and “make do” under conditions of adversity and cynical humiliation’.13

The Lomaxes also recorded songs performed during the inmates’ few leisure hours, such as ‘That’s All Right, Honey’ (1933) by Mose ‘Clear Rock’ Platt. Platt boasted to Lomax of his various jailbreaks and his powers of evasion. In an audacious display of storytelling (and signifyin[g]), he explains that he ran so fast that the ‘splat-splattin’’ of his feet was mistaken for the sound of motorcycle engine, and that his shirttail had caught fire, which was mistaken for a taillight. ‘Dey calls me “Swif-foot Rock” ‘cause de way I kin run’, he explains, adding ‘white man say he thought I mus’ have philosophies in my feet’.14 Platt’s philosophical feet can be heard, faintly tapping downbeats during his singing of ‘That’s All Right, Honey’, each foot-tap answered by a much louder clapped backbeat. Platt sings line after line of affirmative lyrics over the up-tempo ‘stomp-CLAP’ groove, celebrating freedoms that, ‘sho ‘nuff’, will be his. Platt’s exuberant performance testifies to the uplifting power of backbeating; such a spirited performance within the confines of a system designed to break the spirit constitutes a powerful act of resistance, of beating back.

Backbeating in Pentecostal Worship

Body percussion had long been practiced in Western Africa, described by European explorers as early as 1621.15 It took on greater significance in the United States, where drumming among slaves was feared and outlawed in many places. While slave holders could ban drums, they could not ban the bodies that sustained their economy, and accompaniments to sacred song and dance moved from drums to African-American bodies. As Jon Michael Spencer explains, ‘To the African the drum was a sacred instrument possessing supernatural power that enabled it to summon the gods into communion with the people … [and] percussiveness produced the power that helped move Africans to dance and into trance possession … With the drum banned, rhythm … became the essential African remnant of black religion in North America … It empowered those who possessed it to endure slavery by temporarily elevating them … to a spiritual summit’.16

Among Christian denominations, African-American Pentecostal and Holiness (also called Sanctified) churches took up body percussion most fervently. Pentecostalism emphasizes spirit possession, achieved through rhythmic song and dance, and dozens of recordings from the 1920s demonstrate the centrality of backbeating to Pentecostal worship. In Memphis alone, Bessie Johnson and Her Memphis Sanctified Singers, Elder Lonnie McIntorsh, and the Holy Ghost Sanctified Singers made recordings with consistent handclapped backbeats that fuel impassioned vocal performances as in, for example, Johnson’s ‘Keys to the Kingdom’ (1929). Another remarkable example, ‘Memphis Flu’ (1930) by Elder Curry and His Congregation, is a proto-rock-and-roll song, replete with Little Richard-style eighth notes hammered out on the piano’s high, percussive register to solid, communal backbeating. Such congregational backbeating is the audible presence of community; all participants contribute to a unifying, thoroughly embodied groove, which constitutes the primary vehicle for spiritual communion. No wonder Pentecostal preachers like Reverend D. C. Rice would defend percussive worship music, insisting that ‘people need to feel the rhythm of God’.17

Pentecostal music was not only a form of praise, but often a means of protest, with statements of resistance embedded in religious contexts. Most explicit are the various ‘Egypt’ songs, wherein the deliverance of Israelites from Egyptian captivity is understood to prophesy the deliverance of black people from racist oppression in the United States. The earliest vocal recording I have found with consistent backbeating throughout (excepting the introduction) is ‘Way Down in Egypt Land’ (1926) by the Biddleville Quintette. The song confronts the darkest depths of slavery, ‘waaaaaay down in Egypt land’, but the exuberant, rhythmically charged performance, driven by handclapped backbeating, makes clear that this is a celebration of deliverance. Perhaps the earliest drummed backbeating on a vocal record occurs on Elder J. E. Burch’s stirring ‘Love Is My Wonderful Song’ (1927), fuelled by emphatic snare backbeat accents over driving bass drum quarter notes.

A fairly direct line connects Pentecostal backbeating to 1940s rhythm and blues. Prolific gospel recording artist Sister Rosetta Tharpe collaborated with the equally prolific Lucky Millinder on several recordings. Millinder had been leading bands on record since 1933, when he took over the Blue Mills Rhythm Band, but none of his recordings feature prominent backbeats until his work with Tharpe.18 Their 1941 collaboration, ‘Shout Sister, Shout’, features Pentecostal-style congregational backbeating placed at the forefront of the mix during choruses. Millinder would again foreground clapped backbeats on ‘Who Threw the Whiskey in the Well’, a gospel parody describing a worship service that evolves into a spirited, boozy bash. Recorded in 1944 with vocalist Wynonie Harris, the record was a massive hit, spending eight weeks atop the ‘race’ chart in 1945 and crossing over to #7 on the pop chart. Handclapped gospel backbeats propelled Harris’s next hit, ‘Good Rockin’ Tonight’ (1948), a cover of Roy Brown’s ‘Galveston Whorehouse Jingle’.19 Whereas backbeats accompany only the choruses of ‘Shout Sister, Shout’ and ‘Who Threw the Whiskey in the Well’, handclapped backbeating accompanies the entirety of ‘Good Rockin’ Tonight’, excepting the introduction, where drummer Bobby Donaldson plays emphatic snare backbeats thickened by loose, ‘dirty’ hi-hats, which, along with wah-inflected trumpet growls and insinuating saxophone squeals, set a steamy scene for the entry of gospel clapping. Here the sacred and the secular, the spiritual and sexual meet on two and four.

Sex and the Backbeat

Euphemistic references to sex such as ‘rocking’ were commonplace well before the rise of rhythm and blues, especially in a strain of the blues, sometimes called ‘hokum’ blues, built around clever double entendres and thinly veiled references to sex. Hokum blues songs often address the world of prostitution, and many were performed in brothels and bawdy dance halls, where musicians entertained and played music for dancing, particularly the kind of dancing that might encourage subsequent assignations.20 No other strain of the blues from the 1920s and 1930s features as flagrant backbeating as the hokum blues, where the ‘rocking’ celebrated in the lyrics finds a parallel in the back-and-forth motion between bottom-heavy downbeats and penetrating backbeats.

For instance, Margaret Webster’s ‘I’ve Got What it Takes’, recorded in 1929 with Clarence Williams’s Washboard Band, features salacious lyrics set over an infectious, backbeat-based shuffle groove played on the washboard by drummer Floyd Casey. Among the most prolific recording artists of the 1920s and 1930s, Williams recorded with Bessie Smith, Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller, among others, in addition to numerous recordings under his own name. I credit some of his success to the compelling percussive accompaniments provided by Casey. As these records demonstrate, the washboard was well suited to the recording technology of the day, offering a variety of percussive timbres, from the deep ‘thump’ of the wooden frame to the piercing, metallic scrape in the high register. Here the washboard constitutes a kind of miniature drum kit that produced better results in the studio than could be achieved easily with drums. Like the axes and other tools that accompanied prison songs, the washboard represents an instrument of labour that was radically repurposed and deployed in the celebration of freedoms.

Allusions to prostitution are common in the songs of Memphis Minnie, the influential blues singer, songwriter, and guitarist, who, like many musicians of her era, played at brothels and often ‘entertained’ in more ways than one.21 At a remarkable 1936 session, Minnie recorded seven sides, each featuring an unidentified percussionist playing stark, consistent backbeats on either a washboard or woodblock. Most of these songs address sexual politics, some making direct references to prostitution, such as ‘Black Cat Blues’ with the refrain ‘everyone wants to buy my kitty’, Minnie’s saucy swagger punctuated by pulsating backbeats. These are perhaps the earliest recordings to feature backbeating in the context of guitar-based blues, establishing Memphis Minnie as a rhythm-and-blues pioneer.

As Hazel Carby, Shayna Lee, and others have shown, in such songs women performers reclaimed female sexuality from the objectifying male gaze and projected empowering representations of female agency and desire.22 In this context, the backbeat is an apt metaphor for sex, rollicking between steady downbeats and penetrating backbeat accents, imparting an embodied experience that renders these assertions and celebrations of sexuality all the more compelling. Not surprisingly, some of the most influential drummers in the development of rock and roll, including prolific session drummers Earl Palmer and Hal Blaine, and Elvis Presley’s drummer D. J. Fontana – all early masters of the backbeat – started out playing in strip clubs providing rhythmic accompaniments to steamy floor shows.

Shout Choruses, Afterbeats, and the Kansas City School

Earl Palmer has often been noted for his role in standardizing the rock-and-roll beat. He played drum kit on Fats Domino’s ‘The Fat Man’ (1949), an early hit that features consistent backbeats, and his recordings with Little Richard were among the earliest to feature the backbeat in conjunction with straight eighth-note hi-hat or ride cymbal patterns (as opposed to the swung or shuffled accompaniments typical of rhythm and blues and early rock and roll). Palmer identified the Dixieland ‘shout chorus’ as the inspiration for his earliest use of a consistent backbeat.23 In the shout chorus, the ensemble takes up boisterous figures while the rhythm section plays heavy ‘weak’ beat accents. For instance, drummer Andrew Hilaire plays emphatic snare backbeats during the last chorus of ‘Black Bottom Stomp’, recorded in 1926 with Jelly Roll Morton’s Red Hot Peppers. As an isolated, deliberately ‘unruly’ section, the shout chorus stands out as exceptional, as a moment of abandon during which the normal rules do not apply, or rather, in carnivalesque fashion, are inverted.

As early as the 1920s, then, drum-kit backbeating was associated with the kinds of excess and disorder critics would impute to the rock-and-roll beat decades later. The term ‘shout’ chorus alludes to the kind of spirited performances associated with black sacred music, but I have come to think of such choruses in instrumental jazz and later rhythm and blues as ‘cut-loose’ choruses, a metaphor with particular resonance for black people contending with the legacy of bondage. Typically, these backbeat-driven choruses support and impel particularly intense solos that transgress the dynamic, scalar, and timbral restraints in place during ‘regular’ choruses.

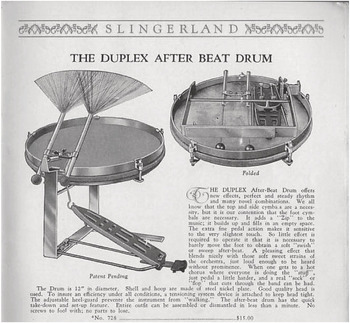

Emphatic backbeats would remain exceptional in jazz drumming, reserved for occasional, particularly boisterous choruses. By the early 1930s, the conventional swing pattern (‘ding ding-da ding ding-da’) had established itself as the central component of jazz drumming. A secondary convention, the ‘afterbeat’, was standardized during the 1930s and emerged in conjunction with a major technological innovation, foot-operated cymbals. Designs from the early 1920s, including the ‘low boy’ (also known as ‘sock cymbals’) and the ‘snow shoe’, led to the hi-hat, which drummers began incorporating into their kits in the late 1920s.24 Bringing two cymbals together via the foot pedal could create a variety of sounds, the most serviceable proving to be the light ‘chick’ produced when the cymbals are brought together and held closed to prevent reverberation. Drummers typically placed the ‘chick’ on the weak beats, either in alternation with bass drum half notes (‘boom-chick-boom-chick’) or over bass-drum quarter notes. The convention of playing left-foot afterbeats was well enough established by 1928 that Slingerland would introduce the ‘Duplex After Beat Drum’ to meet drummers’ evolving needs (Figure 3.1). The advertisement suggests that the ideal afterbeat is ‘just loud enough to be heard without prominence’. As Duke Ellington often explained, the jazz afterbeat was part of a ‘cool’ sensibility that eschewed aggression and provocation in favour of stylized restraint, inciting nothing more than head tilts and finger snaps. ‘Of course, one never snaps one’s fingers on the beat’, he states, ‘it’s considered aggressive. You don’t push it. You just let fall. If you’d like to be conservatively hip, … tilt your left earlobe on the beat and snap the fingers on the afterbeat’.25 Though clearly related, the unobtrusive ‘conservatively hip’ jazz afterbeat was a far cry from the explosive big beat that inspired such fear and fury in the mid-1950s.

The backbeat was central to one exceptional school of jazz drumming. Famed for extended jam sessions, Kansas City jazz musicians of the 1920s and 1930s, cultivated a groove-based aesthetic that distinguished it from the arrangement-based styles preeminent elsewhere. As Ross Russell recounts:

Kansas City had a reputation for the longest jam sessions in jazz history. [Pianist] Sam Price … recalls dropping in at the Sunset Club one evening around 10:00 P.M. A jam session was in full swing.

After a drink, Prince went home to rest, bathe, and change clothing.

He returned to the club around one … and the musicians were playing the same tune. They had been playing it uninterrupted for three hours.26

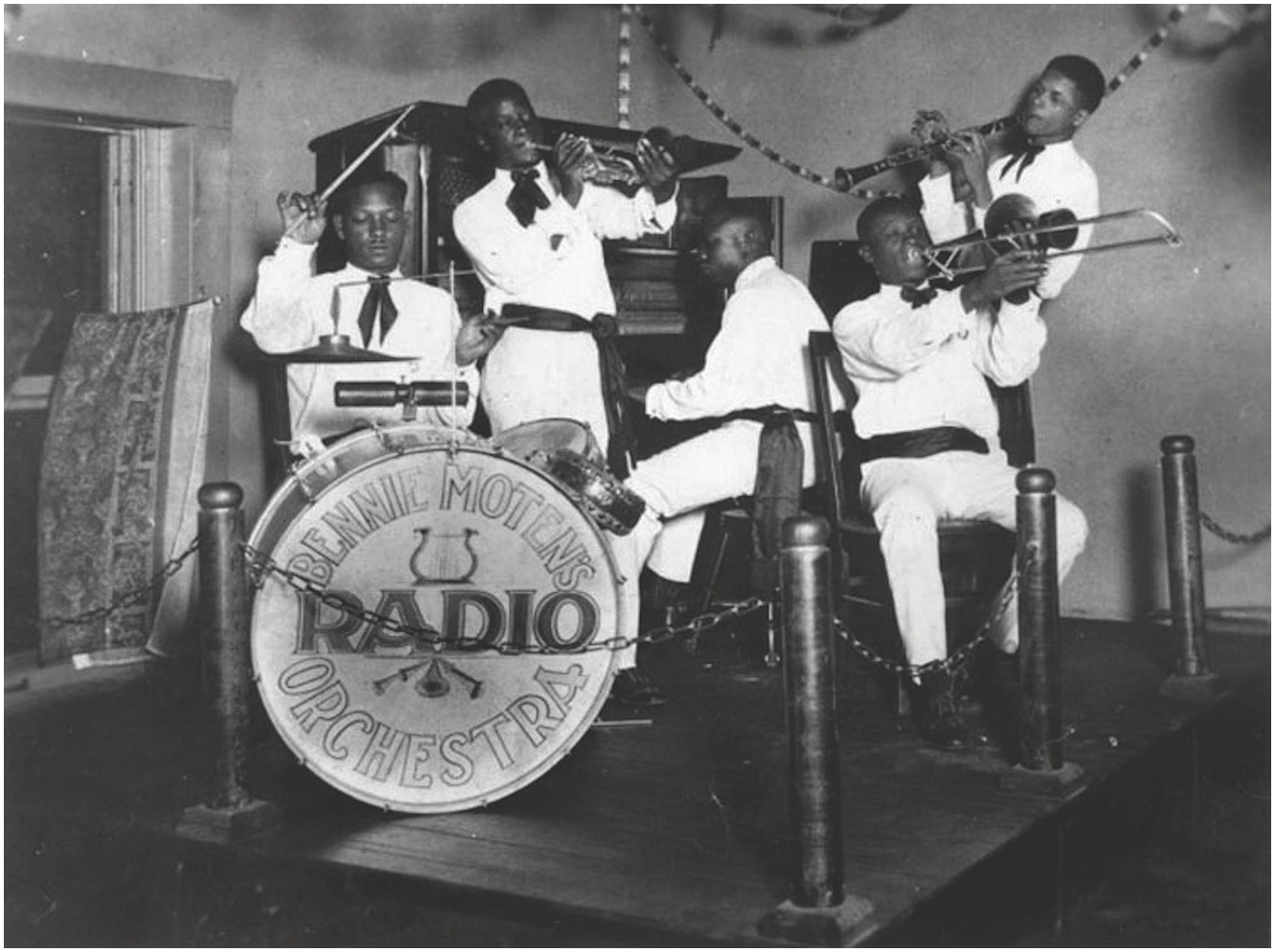

Period recordings suggest that backbeat-based drumming sustained these legendary all-night jams. ‘South’, recorded by Bennie Moten’s Kansas City Orchestra in 1924, is the earliest recording I have yet found featuring strong, consistent backbeats as the primary percussive accompaniment for the entirety of the recording. Willie Hall, like most drummers in the age of acoustic recording, was denied his drum kit in the studio, opting instead for a woodblock, a standard component of the early drum kit and the most common replacement for the snare drum in the studio. Hall lays down consistent woodblock backbeats on all twelve recordings he made with Moten in 1924 and 1925 (Figure 3.2).

Hall left Moten’s band after the 1925 sessions, but the backbeat remained a distinguishing feature of the ensemble. Their 1926 recording of ‘Thick Lip Stomp’ is a clinic in backbeating. Drummer Willie McWashington plays stark backbeats through the first six choruses but varies the treatment throughout, moving from choked cymbal crashes, to the woodblock, and then to the snare. He starts each of the next four choruses with tasteful four-measure solos, setting up dramatic stop-time ensemble backbeating. The whole band rests on the downbeats and plays emphatic percussive accents on beats two and four (excepting the soloist, of course, and occasionally Moten’s piano) in the style of a Dixieland shout chorus, but for four full choruses.

McWashington placed backbeating at the center of his rhythmic accompaniments on nearly all fifteen recordings he made with Moten in 1926 and 1927, before gradually moving towards hi-hat and ride-cymbal-based swing accompaniments on subsequent records. ‘New Tulsa Blues’ (1927) is among several remarkable recordings that feature robust backbeats over well-recorded bass drum downbeats. During the introduction, McWashington plays a shuffle groove that rollicks between heavy bass drum downbeats and shuffled tom-tom eighth notes on two and four:

||: Boom BAA-da Boom BAA-da :||

McWashington maintains propulsive bass-drum downbeats throughout the recording, each kick answered by a forceful ‘whack’, played variously on a snare drum, tom-tom, choked crash cymbal, or woodblock, often in combination. The relentless rocking between heavy downbeats and piercing backbeats, sometimes with subtle, syncopated embellishments, is entrancing, and helps explain why Kansas City musicians were inspired to extend jams to such unprecedented lengths.

The Backbeat in 1940s Rhythm and Blues

The Kansas City school notwithstanding, heavy, consistent backbeats remained rare in jazz through the swing era. With the rise of bebop in the 1940s, jazz drummers further undermined any sense of a regular backbeat, peppering the conventional swing ride pattern with unpredictable snare ornaments and accents and dropping bass drum ‘bombs’ with designed irregularity. A more commercially oriented offshoot of swing that also emerged in the 1940s, jump blues, has often been considered a ‘missing link’ between swing and rock and roll. Longtime Rolling Stone contributor, J. D. Considine, credits 1940s jump blues artists such as Louis Jordan with popularizing the backbeat, introducing the crucial element that would define rock and roll.27 Similarly, legendary composer, producer, and executive Quincy Jones claimed that ‘Lionel Hampton and Louis Jordan were probably the first rock-and-roll bands that were really conscious of what we call the big beat … [Jordan] did shuffle boogie with backbeats and everything else that were all the elements of rock and roll’.28 But the backbeat does not figure prominently on any of Jordan’s recordings until 1949, by which time other artists had been making records with far more emphatic backbeats.

Most of Jordan’s 1940s hits feature an even four-beat boogie-woogie groove alongside a walking quarter-note bass line. The drum kit accompaniments (usually played by Joe ‘Chris Colombo’ Morris or Shadow Wilson) are consistently light and typically feature a snare drum played with brushes, comping a groove based on quarter-note and shuffle patterns over faint four-on-the-floor bass-drum quarter notes, often with light hi-hat afterbeats (as on ‘Caldonia’, ‘Choo Choo Ch’Boogie’, ‘Ain’t Nobody Here But Us Chickens’, and others). Jordan’s drummers sometimes play swing hi-hat accompaniments, with downbeat accents on open hi-hats (‘SHEE Chick-cha SHEE Chick-cha SHEE’) obliterating any sense of a backbeat (as on ‘Saturday Night Fish Fry’ and ‘Is You Is Or Is You Ain’t’). While hi-hat and brushed snare afterbeats are common on Jordan’s recordings from the 1940s, they project a sense of cool restraint similar to the ‘conservatively hip’ afterbeating Ellington endorsed, rather than the aggressive, unrestrained big beat.

The Jordan recording from the 1940s that comes closest to the rock-and-roll backbeat is ‘Beans and Cornbread’ (1949), wherein Jordan invokes the sermonic tone of gospel music. Columbo uses drumsticks rather than the lighter brushes used on most Jordan records, playing a swing ride-cymbal pattern with light snare backbeats, scarcely audible over the hi-hat afterbeats. By contrast, Joe Morris’s version of the song recorded a month later features emphatic backbeats throughout (excepting stop-time sections) as drummer ‘Philly’ Joe Jones doubles loud snare backbeats with explosive cymbal crashes. Ensemble handclaps amplify the boisterous backbeating on Morris’s version of ‘Beans and Cornbread’ and reinforce the gospel allusion. The raucous backbeating imbues the brawl described in the lyrics with far greater turbulence than Jordan’s more humorous version. As such a comparison shows, the backbeating on Jordan’s records through the 1940s more closely resembles the swing afterbeat than the rock-and-roll backbeat.

Jones is on firmer ground with Lionel Hampton, who does foreground backbeats on several 1940s recordings. On ‘Central Avenue Breakdown’ (1941), a heavy boogie-woogie romp fuelled by a dual-piano attack, drummer Al Spieldock drives the groove with emphatic snare backbeats. ‘Hamp’s Boogie Woogie’ (1944) and ‘Hey-Ba-Ba-Re-Bop’ (1946) feature backbeats during extended instrumental sections. On both, drummer Fred Radcliffe supports the soloists (and vocalist on the latter) with light, even, four-beat shuffle grooves for most of the song but kicks the band into a different gear with forceful backbeating during boisterous, cut-loose choruses.

While recordings from the 1940s tend to reserve consistent backbeat accents for exclusively instrumental recordings or instrumental sections of vocal numbers, there are exceptional cases of drummers accompanying entire vocal recordings with emphatic backbeats, the most remarkable being those on Buddy Johnson’s ‘Walk ‘Em’ (1945), played by Teddy Stewart, and Rabon Tarrant’s brushed, but penetrating, backbeat swats on ‘Ooh Mop’ (1945) by Jack McVea’s All Stars. These exceptions notwithstanding, the vast majority of recordings made during the 1940s by jump blues artists, including Amos Milburn, Roy Brown, Joe Liggins, Ivory Joe Hunter, and Roy Milton featured light afterbeat drum kit accompaniments, occasionally with loud backbeats during isolated instrumental choruses. This started to change around 1949, after which most of the artists just named began to incorporate consistent backbeat accompaniments.

This is true as well for other strains of 1940s rhythm and blues. Records by leading blues shouters such as Big Joe Turner, Jimmy Rushing, Jimmy Witherspoon, Wynonie Harris, and Tiny Bradshaw eschew consistent backbeats until after 1949. For instance, Big Joe Turner released dozens of recordings during the 1940s, but his earliest record with consistent backbeats is 1950’s ‘Jumpin’ at the Jubilee’, and even so, the strong handclapped gospel backbeats overpower the unknown drummer’s snare drum. By 1953, however, Turner’s records commonly featured heavy snare backbeats, which are particularly emphatic and up front of the mix on his biggest hits, ‘Honey Hush’ (1953, Alonzo Stewart, drums), ‘Shake, Rattle, Roll’ (1954, Connie Kay, drums), and ‘Flip, Flop, Fly’ (1955, Connie Kay, drums).

We have already encountered the hand-clapped gospel backbeats on Wynonie Harris’s ‘Who Threw the Whiskey in the Well’ and ‘Good Rockin’ Tonight’; however, neither feature drum-kit backbeats for the entirety of the song, nor do any pre-1949 recordings by Harris, which typically feature even four-beat shuffle grooves similar to those on Jordan’s recordings. Starting with ‘All She Wants to Do Is Rock’, a paean to a sexually voracious girlfriend recorded with Joe Morris’s band (Kelly Martin, drums) in 1949, strong backbeats figure prominently on many of his records. For instance, ‘Lovin’ Machine’ (1951) features drummer William Benjamin playing heavy backbeats accompanied by a swing pattern played on slightly opened hi-hats. As in the introduction to ‘Good Rockin’ Tonight’, reverberating, loose hi-hats produce a noisy, ‘dirty’ tone (as opposed to the crisp, ‘clean’ tone of tightly closed hi-hats) that – along with the emphatic backbeats, growling horns, and honking saxes – provide a raunchy backdrop to Harris’s sexually charged lyrics.

Garry Tamlyn traces a similar trajectory with blues instrumentalist-singers of the 1940s. Backbeats are rarely featured for an entire track on recordings by artists such as Muddy Waters, Eddie Boyd, ‘Big’ Bill Broonzy, Floyd Dixon, and others throughout most of the 1940s, but become increasingly common from roughly 1949 onwards.29 Notable exceptions include Jazz Gillum’s ‘Roll Dem Bones’ (1946) and Muddy Waters’s ‘Hard Day Blues’ (1946), both featuring drummer Lawrence ‘Judge’ Riley, a fixture of the Chicago blues scene. On the former, Riley accompanies the entire tune, excepting stop-time sections, with some of the heaviest, most consistent backbeats recorded during the 1940s. The latter features solid, if relatively subdued, backbeats throughout, but, following several verses decrying a life of frustration, Riley explodes with emphatic backbeats that erupt from beneath the musical surface, blowing the lid off of the recording’s dynamic restraints and impelling a fiery James Clark piano solo.

The Big Beat Takes Over

Pioneer that Riley was with his heavy, albeit often sporadic, backbeats on recordings by Arthur Crudup, ‘Big’ Bill Broonzy, Muddy Waters, and others, it is not likely he had a profound impact beyond the Chicago blues scene before 1950. None of his backbeat-based recordings cracked the charts, nor was there a proliferation of backbeats on record after he started employing them in 1946. But there would be after 1949, most likely due to the cumulative impact of several enormously successful, backbeat-based recordings from that year (in addition to ‘The Fat Man’, mentioned above, and ‘Good Rockin’ Tonight’ from the previous year).

Wynonie Harris points to one of them in ‘All She Wants to Do Is Rock’, when he boastfully proclaims:

My baby don’t go for fancy clothes, high class dinner, and picture shows,

All she wants to do is stay at home and hucklebuck with daddy all night long.

Harris’s use of the term ‘hucklebuck’ as a euphemism for sex is a reference to the biggest rhythm-and-blues hit of 1949, ‘The Huckle-Buck’ by Paul Williams and His Hucklebuckers, an instrumental track based on Charlie Parker’s ‘Now’s the Time’ (1945), now outfitted with a backbeat-based groove anchored by Reetham Mallett. During statements of the main theme (starting at :35 and 1:54), Mallett swats the backbeat more forcefully and drops heavy bass drum bombs that anticipate selected downbeats, boosting the allure of Parker’s slinky melody with insinuating low-end bumps, an early instance on record of the backbeat played in conjunction with a prominent, syncopated bass drum part. The effect proved irresistible, and ‘The Huckle-Buck’ spent a record-breaking fourteen weeks atop the R&B chart.30

The same day Williams’s band recorded ‘The Huckle-Buck’ (15 December 1948) in New York City, Big Jay McNeely’s All Stars recorded ‘Deacon’s Hop’ in Los Angeles, which also topped the R&B chart in 1949, fuelled by a heavily percussive, backbeat-based accompaniment. The recording opens with McNeely soloing to the accompaniment of nothing but loud swing hi-hats and handclaps that double the swing rhythm with accents on two and four. The stark saxophone-percussion texture alternates with full band sections, during which drummer William Streetser lays down heavy backbeats, fattened by loud, loose hi-hat hits. The title ‘Deacon’s Hop’ implies the same comingling of the sacred and secular we encountered with Harris’s ‘Good Rocking Tonight.’ Sonically, the handclaps evoke the world of worship, while the emphatic backbeats and ‘dirty’ reverberating hi-hats match McNeely’s bawdy honking, moaning saxophone. Documenting a McNeely performance, photographer Bob Willoughby apparently snapped one of his shots precisely on the backbeat as audience members pound the stage and snap their fingers in unison (Figure 3.3). The image captures the power of communal backbeating and illuminates why it was so threatening to conservative leaders in the 1950s; enraptured male fans beat the stage violently with clenched fists while a white female fan snaps her fingers, just visible between McNeely’s legs as he writhes suggestively and wails on the saxophone to the intense delight of the crowd.

One of the most impactful backbeats of the early 1950s appears on ‘Sixty-Minute Man’, the Dominoes’ massive 1951 hit. Like other early backbeat-driven hits, ‘Sixty Minute Man’ fuses the sacred with the sexual, as a vocal harmony group of the gospel tradition offers a graphic celebration of swaggering male sexuality. The backbeat, played by a drummer whose name went unrecorded, is bolstered by gospel handclaps, both placed high in the mix of a sparse arrangement. The ‘in-your-face’ backbeat at the song’s moderate tempo projects the erotic rocking that Allan Bloom would decry as ‘the beat of sexual intercourse’.31 It helped drive ‘Sixty-Minute Man’ to the top of the R&B chart, where it stayed for fourteen weeks (matching the record set by ‘The Huckle-Buck’), crossing over to #17 on the pop chart, astounding for a song with such graphic lyrics. By 1952, the backbeat was a well-established convention common in all strains of rhythm and blues. It would require a white performer to bring the backbeat into the living rooms of white, middle-class Americans nationwide.

On 5 June 1956, Elvis Presley caused a sensation with his controversial hip-shaking performance of ‘Hound Dog’ on the Milton Berle Show. Towards the end of the performance, Presley dramatically cues his unsuspecting bandmates to stop, before leading them in a slow, grinding reprise of the tune, conducted largely by Presley’s thrusting pelvis. As drummer D. J. Fontana remembers:

All of a sudden, he decides he’s going to go into this blues thing. That was the first time he had done it anywhere, and we all looked at each other, ‘What do we do now?’ … I went back into my roots playing strip music actually … and I just figured well I better catch his blues licks and his legs and arms and do everything I can.32

Fontana’s roots in ‘strip music’ apparently involved hard, spanking backbeats, which he ably deploys at Presley’s slowed down tempo, impelling the singer’s pelvic gyrations. As Matt Brennan explains, it was Fontana who introduced Presley to the backbeat and inspired his famous stage moves.33 Fontana’s backbeat and Presley’s pelvis caused an uproar, exhilarating and outraging viewers in equal measure, and inspiring the kinds of condemnations of beat music I cited at the beginning of this chapter.

Conclusions

Of course, there was far more at stake than the prudish sensibilities of the white middle class in 1950s America. The ‘vulgar’ performance of Presley and his band reinforced the notion that rock and roll was primarily about ‘disorder, aggression, and sex: a fantasy of human nature, running wild to a savage beat’.34 Most alarmingly, Presley’s performance – profoundly and unashamedly influenced by African-American music and dance – represented a shocking case of cultural desegregation and an imminent threat to a white supremacist ideology entrenched since the nation’s founding. And it did so backed by the interpellating force of the backbeat, a musical idiom deeply rooted in African-American signifyin(g) practices and strategies of resistance. By the end of the 1950s the backbeat had become firmly established as a primary convention, not only of rock and roll, but of popular music more broadly, and has since become so ubiquitous that its early history has been obscured.

I believe this history helps explain why the backbeat has proven to be so compelling and why it posed such a threat in the mid-1950s. Now a central convention of most popular music genres, drummers, engineers, and producers have dedicated enormous effort to crafting effective treatments of the backbeat, from the conga doubling that gives ‘Let’s Stay Together’ and other Al Green hits their distinctively deep, warm backbeat to the tambourines, tire chains, and wall scrapes used to enhance the backbeats behind the Motown sound, from the celebrated ‘delayed’ backbeat cultivated at Stax Records to the massive, electronically contrived backbeats in some strains of popular music since the 1980s. Reverend Snow was right to consider the backbeat a powerful cultural force, and we are only beginning to recognize its profound impact on American cultural history.